Posts Tagged by aimee burpee

*Batteries and Fuel Not Included: The Hop Rod, the World’s First “Powerized” Pogo Stick

Over the years many fun-but dangerous-toys have been marketed to children, only to be discontinued or banned. Remember chemistry sets with toxic materials? Or lawn darts capable of serious injury? Then there was the Hop Rod-a pogo stick powered by a combustion engine. Exploring the history of pogo sticks can help us understand the brief, explosive rise (and fall) of the Hop Rod in the early 1970s.

Early Hopping

Stilts were popular in 19th-century America for entertainment and recreation, and useful as tools for agricultural tasks. Among their early innovators was George H. Herrington, a bookstore owner from Wichita, Kansas, who held at least seven U.S. patents, including for a phonograph, fire escape, and typewriting machine. In February 1881 Herrington received a U.S.patent for his “spring-stilt” - a pair of wooden stilts with compression springs under each foot, intended to help users leap “great distances and heights.”

Illustration from U.S. Patent 238,042, issued to George H. Herrington of Wichita, Kansas, on February 22, 1881 / United States Patent and Trademark Office

Illustration from U.S. Patent 238,042, issued to George H. Herrington of Wichita, Kansas, on February 22, 1881 / United States Patent and Trademark Office

The Hopping '20s

Fast forward to Europe. Germans Ernst Gottschall and Max Pohlig received a patent in 1920 for a "springy-looking hopping stuff." Unlike Herrington’s, it was just one stilt, with a spring mounted between the pole and base and a double footrest. The name “pogo” is believed to be derived from the first two letters of their last names—a common naming practice in Germany at the time. Around the same period, British inventor Walter Lines patented a similar vertical single-handled “hopping-pole."

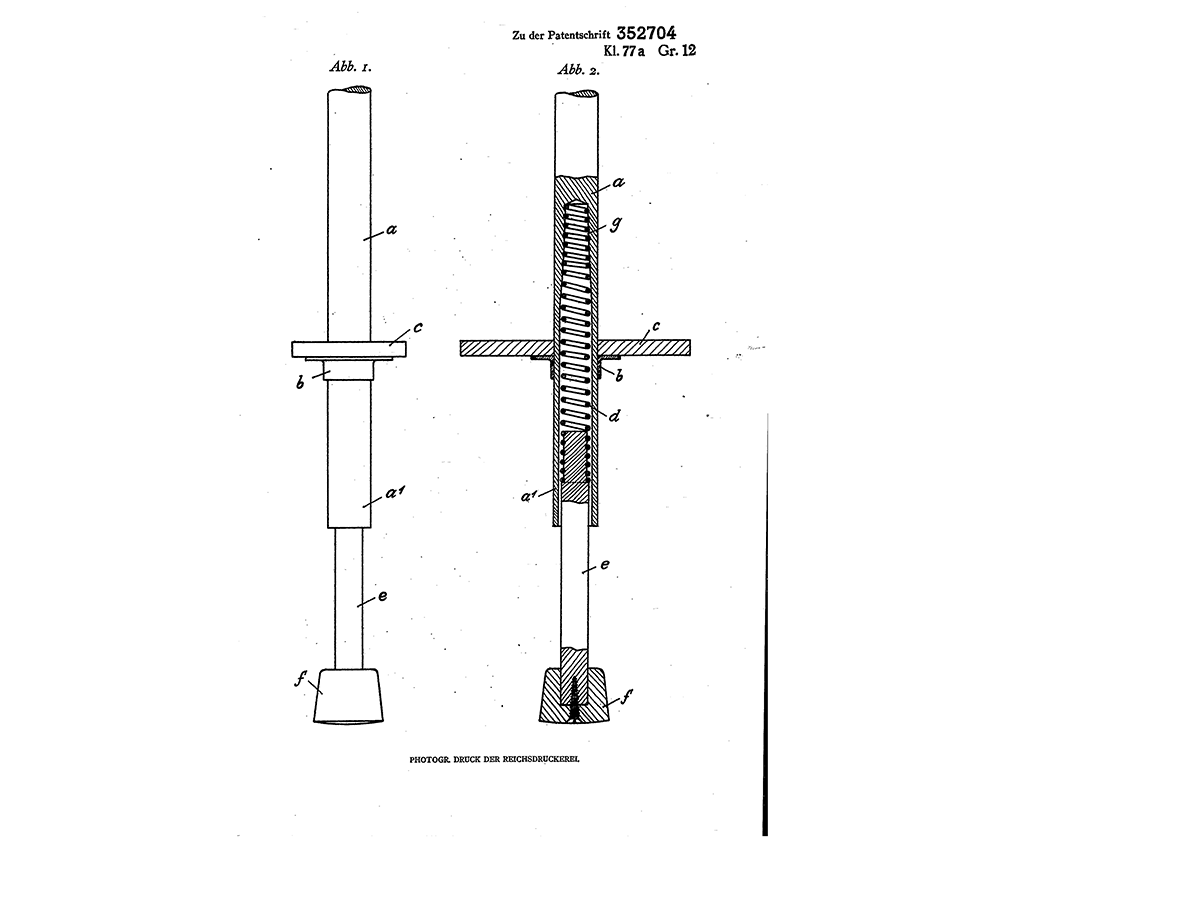

An illustration from Gottschalk and Pohlig’s patent for the “Federnd wirkende Hupfstelze” (“springy-looking hopping stilt”), issued in Hanover, Germany, March 9, 1920 / German Patent and Trade Mark Office.

An illustration from Gottschalk and Pohlig’s patent for the “Federnd wirkende Hupfstelze” (“springy-looking hopping stilt”), issued in Hanover, Germany, March 9, 1920 / German Patent and Trade Mark Office.

As pogo sticks gained popularity in Europe, American sporting goods and department stores placed orders with overseas manufacturers. One New York City department store, however, received an order of pogo sticks that had mildewed and decomposed due to the damp conditions on the ship. Stores began looking for U.S manufacturers. George Hansburg’s SBI Enterprises in Ellenville, New York, started manufacturing pogo sticks. By June 1922, the word “pogo” was trademarked in the United States to refer to a jumping stick.

A 1920s pogo stick with a single vertical post, which could cause injuries to the rider’s chin. / THF805470 (left), THF805474 (right)

A 1920s pogo stick with a single vertical post, which could cause injuries to the rider’s chin. / THF805470 (left), THF805474 (right)

Though often credited as the pogo stick’s inventor, George Hansburg did not patent anything resembling a pogo stick in the 1920s. However, the United States experienced its first pogo stick boom in the 1920s due to the increased domestic production. Contests, races, and other pogo stunts popped up across the country. The Ziegfeld Follies even developed a stage show that featured performers on pogo sticks. Hansburg eventually redesigned the pogo stick – with double horizontal handles to reduce the risk of chin injuries from the vertical pole and received a U.S. patent for this improved design in 1957.

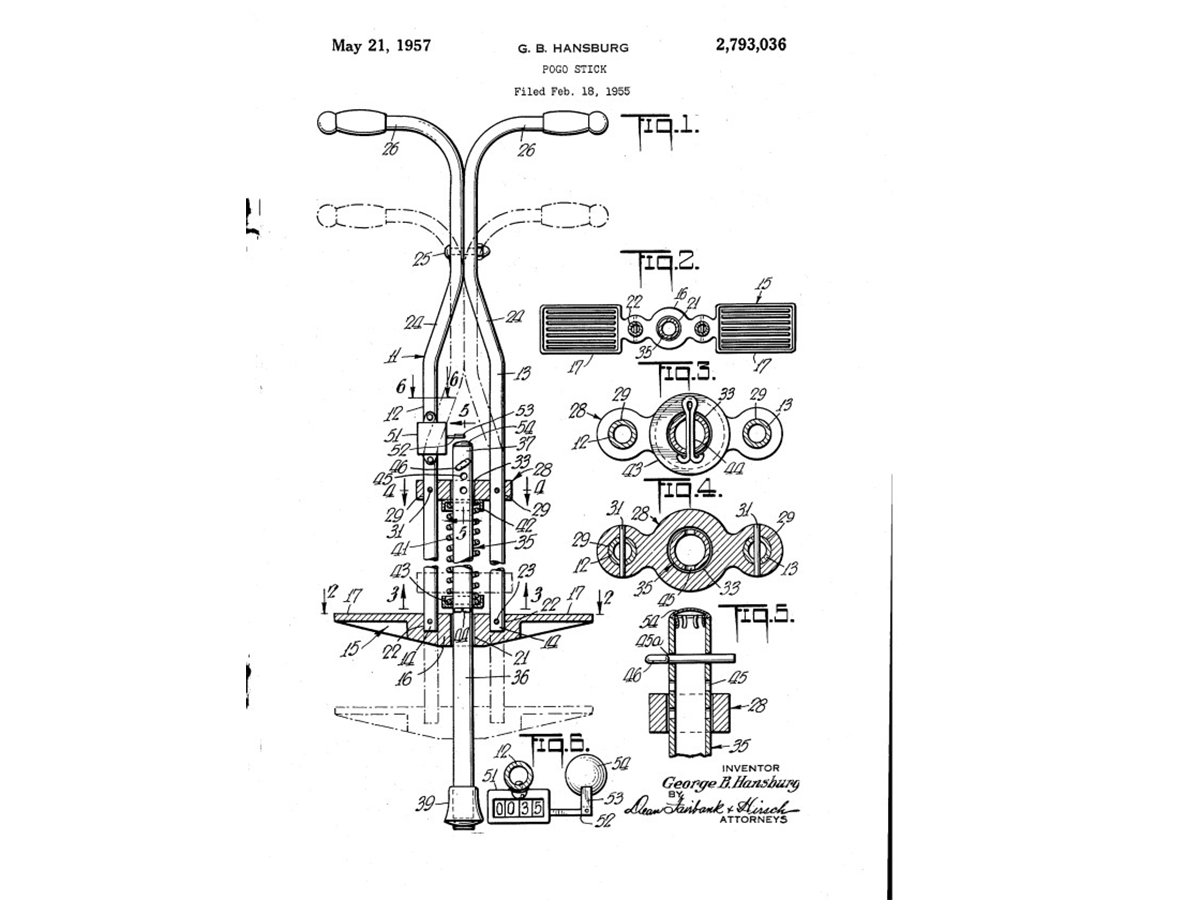

George Hansburg did not invent the pogo stick, but he helped improve it. This illustration of his patent from 1957 shows the horizontal handles that decreased incidences of facial injuries. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

George Hansburg did not invent the pogo stick, but he helped improve it. This illustration of his patent from 1957 shows the horizontal handles that decreased incidences of facial injuries. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

Adding Fuel to the Hopping Craze

The pogo sticks experienced a resurgence in the 1950s, becoming a favorite of the baby boom-era children hopping around suburban neighborhoods. It was during this time that Elwood, Indiana, farmer Gordon Spitzmesser had an idea: what if you added an engine?

Spitzmesser experimented with various designs, including combining the barrel of a grease gun with a piston from an old lawnmower and a Ford Model A spark coil. His son Edwin was his test jumper, trying out various fuel mixtures. Oxygen and acetylene resulted in intense jumps, but in the end, Spitzmesser settled on butane as the safest. In March 1960 Spitzmesser received a patent for a “Combustible Gas Powered Pogo Stick” which he called the “Pop Along.”

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / United States Patent and Trademark Office

In 1961 Spitzmesser and his son appeared on national television. Edwin hopped around while his father explained the mechanics behind his invention. Although Spitzmesser never pursued mass production of his “Pop Along,” his patent was eventually acquired by Chance Manufacturing Co. of Wichita, Kansas.

The Hop Rod Takes Off

By 1971, Chance Manufacturing - best known for amusement park rides - began developing their own version of Spitzmesser’s design. After a year of testing, they released the Hop Rod, a pogo stick with a one-cylinder, two-cycle engine. It could run for up to 30 minutes - or approximately 600 hops - on four ounces of gas, preferably their proprietary blend called "Pogo-Go,"and eight C batteries. The Hop Rod activated when the rider's weight compressed the piston into the cylinder and activated the spark plug that fired the engine, launching the rider into the air.

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803604

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803604

Priced at around $70, the Hop Rod was marketed to parents and children, featured in commercials and local newspaper ads. Retailers across the country stocked the Hop Rod, including Young Diversified Industries in New Jersey and Midtown Cycles in Florida. Moto Pogo, Inc. in Vermont even offered a free electric popcorn maker (“Butterpopper”) with purchase in April 1973. The Hop Rod appeared at automobile shows, including the 17th Annual New York Automobile Show in New York City in April 1973. Newspaper articles of the time touted brisk sales, highlighting the Hop Rod as the hot Christmas gift in both 1972 and 1973.

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803610 (left),THF803607 (center), THF803611 (right)

Gordon Spitzmesser's 1960 patent that eventually became the basis for the Hop Rod. / THF803610 (left),THF803607 (center), THF803611 (right)

But the Hop Rod was a shooting star - fast and flashy but too dangerous. Each engine “pop” produced increasingly higher jumps, sometimes beyond what the rider could control. The engine engaged upon impact with the ground - regardless of whether the rider landed vertically or at an angle - making it easy to be flung sideways into trees or other obstacles. Injuries followed, and the new gadget shine quickly wore off. By 1975, sales slumped, and Chance Manufacturing discontinued the Hop Rod.

Modern-Day Hopping

Although fuel-powered pogo sticks have vanished, pogo technology continues to evolve. Today's models use compressed air or solid rubber tube technology to absorb and release energy, enabling higher jumps and extreme tricks. Whether low-tech or high-powered, the pogo stick keeps on hopping into the 21st century.

The Henry Ford’s Hop Rod was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

Aimee Burpee is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Women in Service: From the Civil War to WWII

Throughout history, women have served their country during war and in peacetime, on the home front and at the front lines. Since the founding of this country, both military and civilian women contributed to their nation’s cause—whether through active service, or by using their talents and time to support our fighting forces from afar—in ways that were and are often overlooked. Through these objects from the collections of The Henry Ford, we can explore some of these important stories, shedding light on women and their service.

Frances Clayton

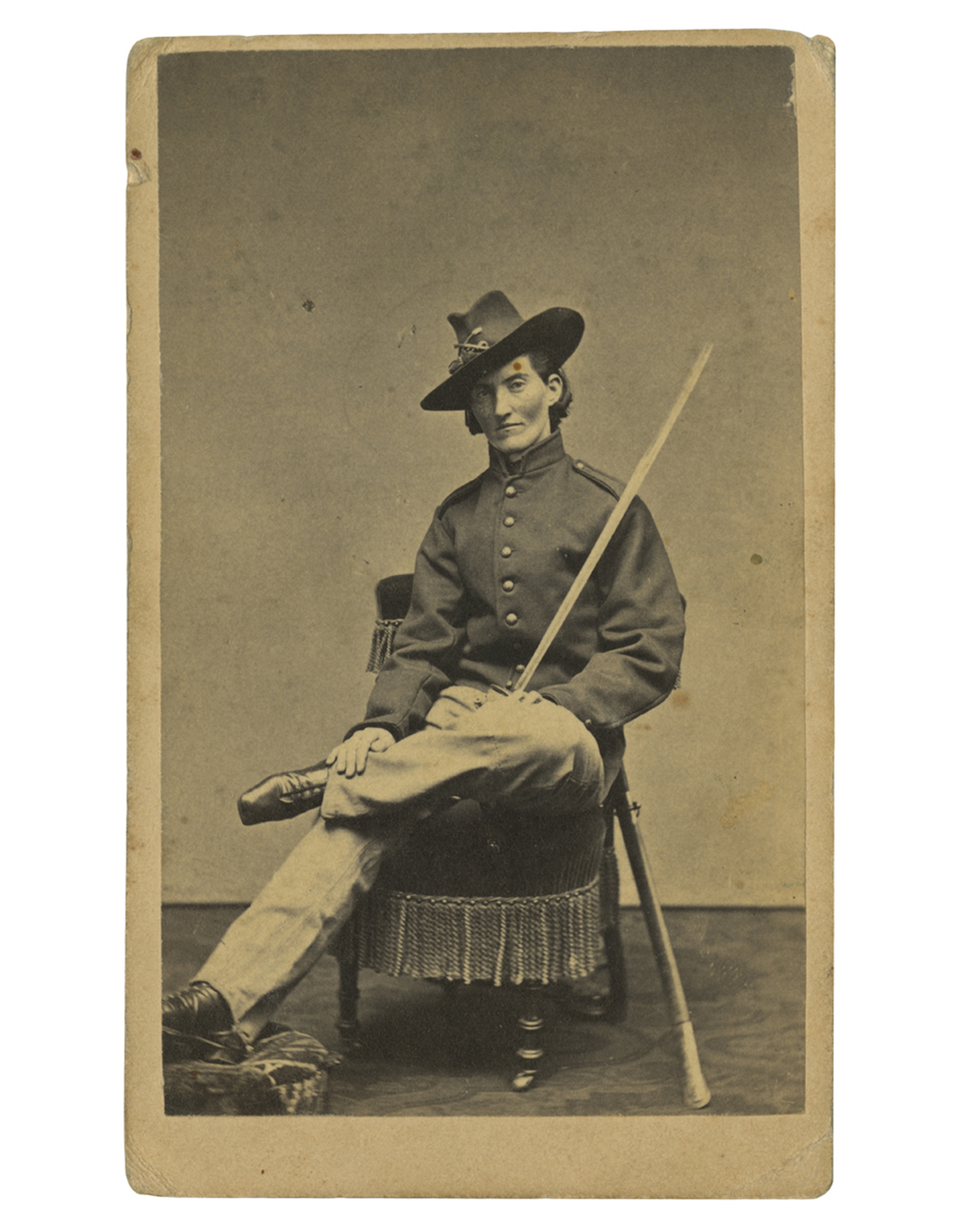

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

While women could not officially serve in combat roles in the United States until 2016, women participated in combat as early as the American Revolution—dressed as men.

During the Civil War, hundreds of women concealed their identities to enlist and fight in battles across the country. Their motivations varied: some wanted to stay close to husbands, brothers, or other loved ones, while others sought to defy societal norms, pursue adventure, or earn a soldier’s pay and enlistment bounty. Patriotism was another driving force—with northern women supporting the Union or abolitionist causes, and southern women joining to support the Confederacy.

At the time, joining the military was easier. With an urgent need for soldiers, physical exams were brief, and no identification was required. A woman could cut her hair, wear men’s baggy clothing, and adopt a male alias. Some were eventually discovered and sent home, others were wounded or killed during service, and others returned home, mustering out at the end of their service.

—Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator

WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps

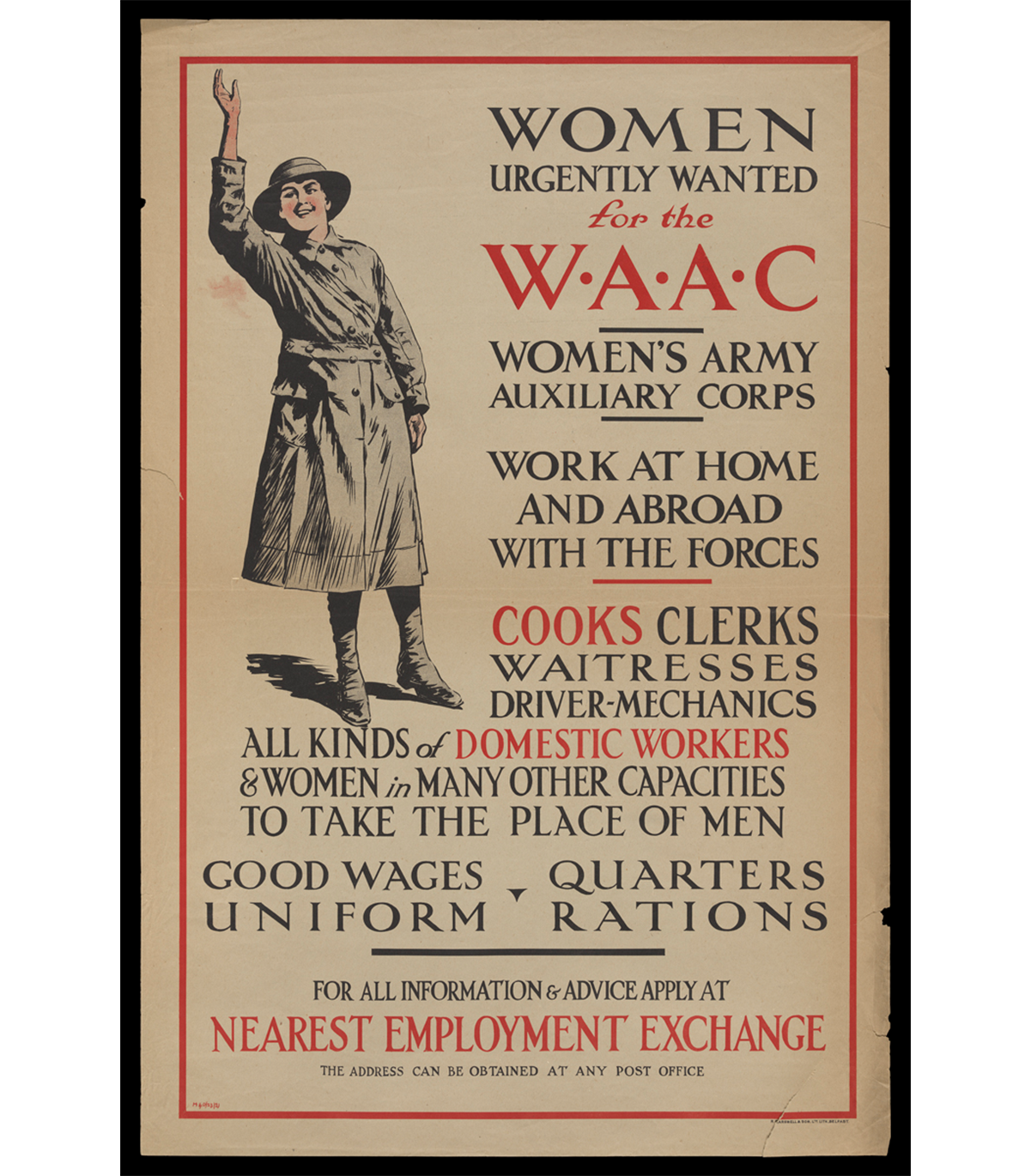

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

Over 50,000 British women volunteered with the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1917 and 1918, the final two years of the First World War. WAAC volunteers took on support roles such as administrative work, catering, or vehicle maintenance at home in the United Kingdom and on the front in France and Belgium. In doing so, WAAC freed up British men on the front from non-combative tasks so the military could focus on the battlefield. This was the first time that women were allowed in the British armed forces in an official capacity outside of nursing.

The corps was renamed Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1918 after Mary of Teck, the queen consort of King George V, became the corps patron. The original WAAC/QMAAC disbanded in 1921, but it inspired women's auxiliary military corps in Great Britain and the Commonwealth and in the United States during the Second World War.

—Kayla Chenault, Associate Curator

“Molly Pitchers”

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

"Molly Pitcher" was the symbolic name given to several historic women who served during the Revolutionary War. These women, usually a soldiers' wife, were noted for carrying water and other provisions to frontline troops. But they became more famous for fighting alongside other soldiers after their husbands or loved ones had fallen in battle.

During the Second World War, August 4, 1943, was designated Molly Pitcher Tag Day. On that day, thousands of women throughout the United States dressed in early American or patriotic costumes and became contemporary "Molly Pitcher" heroines by selling war stamps and bonds. At Greenfield Village, Women's Army Corps recruiters from Detroit, Michigan, and four "Molly Pitchers" came together to raise money for the bond drive, shining a light on women's contributions—whether on the home front or in military service—to America's war efforts since our country's founding.

—Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator

Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

Husband-and-wife designers Charles and Ray Eames spent the early years of their partnership experimenting with molding plywood for use in furniture and sculptural objects. In the early 1940s, they used the spare bedroom in their Los Angeles, California, apartment to develop a machine to mold plywood using pressure. A friend, Dr. Wendell Scott of the Army Medical Corps, visited the Eames’ home and saw the potential of molded plywood for the war effort. America’s entry into World War II had created material shortages, including metal. Despite the shortage, metal splints were being used for broken limbs on the battlefield even though they were inflexible and heavy, and worsened wounds in transport.

Upon hearing this, the Eames designed a flexible, lightweight and durable leg splint using the same molded plywood technology they were developing for plywood furniture. They presented their prototype splint to the U.S. Navy and worked with them to further modify and perfect the product. By 1942, the Navy had placed an order for 5,000 splints. The Eames Leg Splint became a successful medical innovation and a design artifact, as well as a critical step in the Eames understanding of molded plywood.

—Adapted from What if Collaboration is Design? Katherine White, Curator of Design

Lillian Schwartz, Nurse Cadet

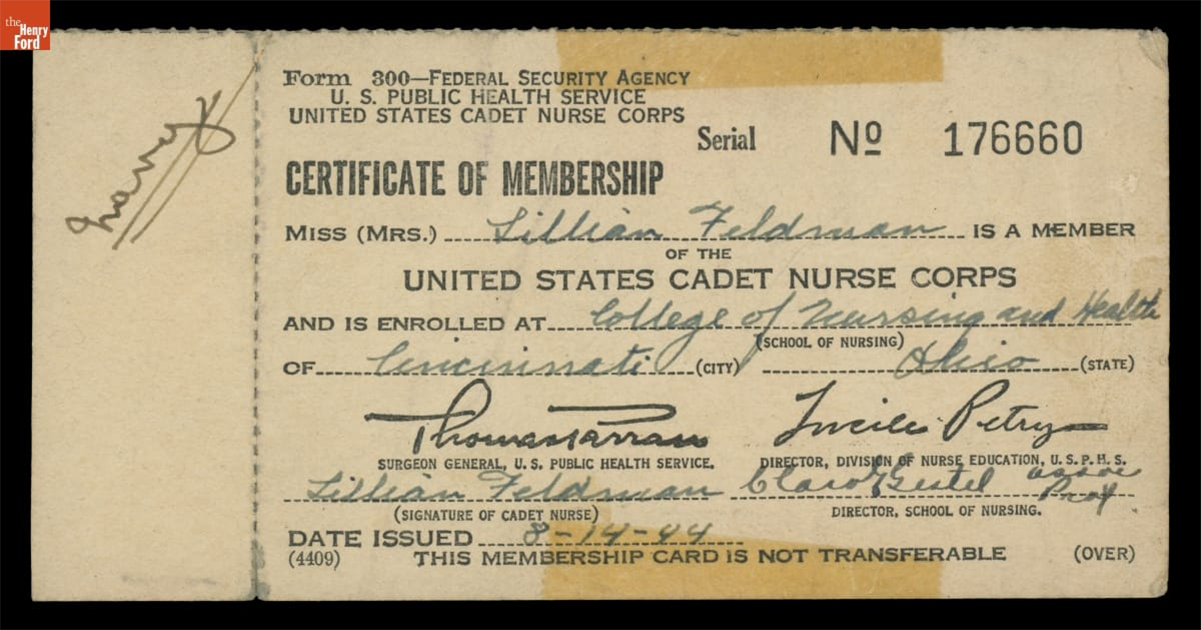

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Feldman Schwartz (1927-2024) was an American artist who began working at the forefront of computer art and experimental film in the late 1960s at Bell Laboratories. Before her art career was established, however, her life was entwined and impacted by service in the medical field during the last years of WWII, and in its immediate aftermath.

In 1944, when Lillian was 17, she applied to the United States Cadet Nurse Corps—a tuition-free program designed to address the WWII nursing shortage. Lillian did well in her coursework, but she quickly realized that she struggled with nursing people. Despite this, she found ways to bring joy into the Cincinnati hospital where she worked by painting murals in the children’s ward and making plaster sculptures in the cast room. Lillian quickly realized that she was an artist, not a nurse. While working in the hospital pharmacy, she met an intern named Jack Schwartz, whom she would marry in 1946. In 1948, Jack was stationed in Fukuoka, Japan, and Lillian traveled to join him after the birth of her first son. Unfortunately, she developed polio symptoms several weeks after her arrival, and in the post-war aftermath, she was also exposed to the lingering effects of radiation from the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These experiences led to serious health issues throughout her life and were often referenced in her art projects and writing.

—Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

This collaborative blog was written by the staff of The Henry Ford

by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Aimee Burpee, by Rachel Yerke-Osgood, by Andy Stupperich, By Kayla Chenault, by Katherine White

In late 2015 The Henry Ford received a significant donation of studio glass from Bruce and Ann Bachmann of Chicago, Illinois. Already home to a strong historic glass collection — representing glassmaking in America from the colonial period to the mid-20th century — this new acquisition added over 300 works of glass art dating from the late 1950s to the early 2010s.

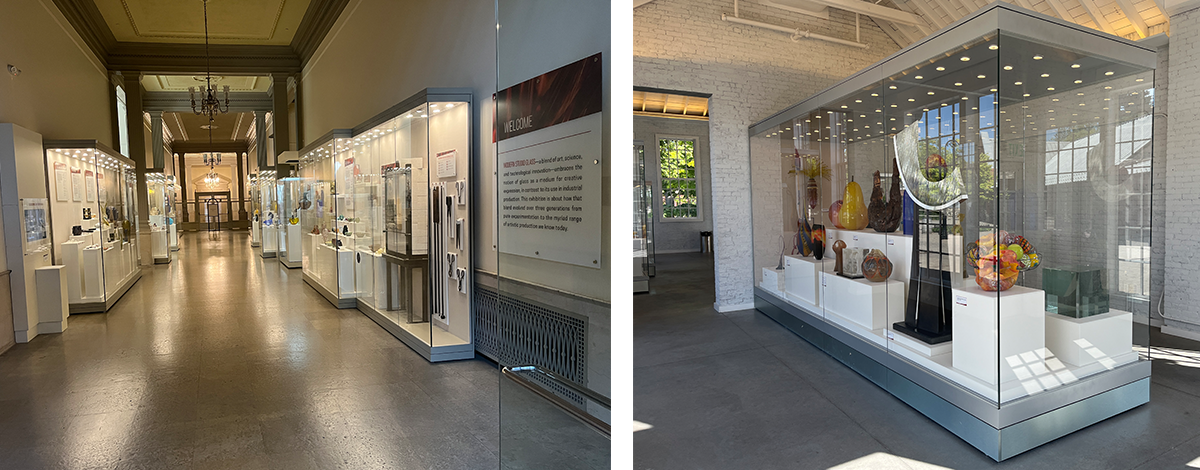

In October 2016 The Henry Ford opened the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, highlighting the story of Studio Glass movement from its beginnings through to its diffusion into contemporary society. The following summer, the Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass opened in Greenfield Village, showcasing the history of American glass from the 17th century to the present.

Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation (left), and large case of studio glass in the Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass in Greenfield Village (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

With glass in the spotlight, The Henry Ford was looking for ways to maintain the momentum. In 2017 staff from across departments developed the idea of an artist-in-residence program, bringing studio glass artists to work on-site in the Greenfield Village Glass Shop. Over the course of five days, visiting artists would collaborate with The Henry Ford's glassblowers, sharing techniques and styles while creating new, original works.

This was not exactly without precedence. Studio glass pioneer Dominick Labino worked informally in the glass shop in the 1970s, experimenting and practicing after hours. And although current staff members spends much of their time producing items for sale on-site and online, they are also artists eager to create and collaborate.

Visiting The Henry Ford during a glass event, studio glass artists and friends Laura Donefer and Leah Wingfield posed in front of their artwork on display in the museum gallery (left). Laura Donefer works with The Henry Ford’s Josh Wojick in the glass shop (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

The program has proved beneficial, both to the visiting artists and The Henry Ford. Glass shop staff and Greenfield Village visitors have been able to observe the styles and techniques of artists from all over the world. Visiting artists have had access to view the collections for inspiration, and produce multiple works during their residencies, selecting one piece to add to The Henry Ford’s collection.

The first artist-in-residence in summer 2017 was Hiroshi Yamano, a leading figure in Japanese studio glass. He is known for his innovative surface decorations and nature-inspired themes. In a memorable twist, Yamano even completed some of his signature decorative work in his hotel room to bring back to the shop to apply to the glass!

Another highlight that summer was Herb Babcock, professor emeritus in the glass program at Detroit’s Center for Creative Studies. Many glassblowers who have worked at Greenfield Village through the years were former students of Babcock.

Note the elements from nature – fish and flower – along with the applied surface decoration in this piece created by Hiroshi Yamano (left). Herb Babcock played with colors to create this vase (right). / THF180564 (left), THF180561 (right)

In 2018 four artists participated in residencies — Giles Bettison, Laura Donefer, Davide Salvadore, and David Walters, followed by three — Dean Allison, Robin Cass, and Shelley Muzylowski Allen — in 2019.

Shelly Muzylowski Allen’s “Chalcedony Bear” is a swirl of colors imitating quartz (left), and Robin Cass's “Aureate Scarlet Tenax” evokes botanical or biological specimens (right). / THF177784 (left), THF177787 (right)

In 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic forced suspension of the program for two summers.

The program resumed in 2022, but on a smaller scale, with only two residencies. That year, Ben Cobb and the husband-and-wife team Michael Schunke and Josie Gluck brought their talents to the glass shop. Jen Elek and Kelly O’Dell followed in 2023. In the summer of 2024 James Mongrain created a Venetian-inspired vessel topped with a seahorse, and Jack Gramann used the human portrait as a motif in his work.

“65 Million Years” by Kelly O’Dell, 2023 (left), Ben Cobb’s “Maple Spinner” from 2022 (center), and Jack Gramann’s “Human Face” from 2024 (right). / THF370839 (left), THF370282 (center), THF802223 (right)

In May 2025 The Henry Ford finally welcomed Nick Mount, a veteran glass artist from Adelaide, Australia. Originally scheduled for 2020, his residency was delayed due to the pandemic. A leader in Australia’s Studio Glass movement since the 1970s, Mount was first inspired by American artist Richard Marquis, who introduced Venetian glass techniques at art schools in Australia. Inspired to pursue glass, Mount toured Australia with Marquis, demonstrating blown glass. With funding from the Crafts Board of the Australia Council, he was able to study glass in the United States and Europe.

In 2022 a case was added to the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery to display a selection of artist-in-residence pieces, along with an interactive video to “meet the artists” (left), while in 2024 additional artist-in-residence pieces were selected to be displayed in the wall case in the Greenfield Village glass shop (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

After returning to Australia, Mount has balanced creating functional glass objects for retail with creative artworks that have found their way into private collections and museums around the world. For over 50 years Mount has made significant contributions to the art form through both his work and teaching.

Images of Nick Mount working in the Greenfield Village Glass Shop in May 2025. / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

As part of the artist-in-residence program, The Henry Ford’s Media Relations and Studio Productions team film the artists at work and conduct one-on-one interviews to preserve their stories and work and document their thoughts on artistic practice.

Within the Bachmann donation there was already one piece made by Nick Mount in The Henry Ford’s collection, Scent Bottle #101200, made in 2000 (left). Nick Mount’s in-process artwork for THF’s collection (right). / THF803684 (left), photo by Staff of The Henry Ford (right)

Boyd Sugiki (left) and Lisa Zerkowitz (right). / Image courtesy of Two Tone Studios

In July 2025, the owners of Two Tone Studios in Seattle, Washington, Boyd Sugiki and Lisa Zerkowitz, were in residence. Raised in Hawaii, Boyd Sugiki earned his BFA in glass at the California College of Arts and Crafts. Lisa Zerkowitz, a California native, received her BA in Studio Art from the University of California at Santa Barbara. In 1995 while pursuing MFAs at the Rhode Island School of Design, the two began blowing glass together. They founded Two Tone Studios in 2007 and have taught at universities across the U.S. and internationally. Like Nick Mount, their original residency was postponed from 2020.

The artist-in-residence program strongly aligns with The Henry Ford’s mission to provide “unique educational experiences based on authentic objects, stories, and lives from America's traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation.” There are even thoughts about expanding the program to other areas of Liberty Craftworks — weaving, pottery, and printmaking. Stay tuned!

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Exploring the Depths of Our Collections

Preserving the past is resource-intensive, and The Henry Ford actively seeks grant funding to support its mission "to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic objects, stories, and lives from America's traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation." Some of these grants focus on enhancing collections storage, stewardship, and accessibility — both physical and virtual. In late summer 2024, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) awarded The Henry Ford a two-year grant to clean, rehouse, and create digital records for artifacts related to power and energy, mobility and transportation, and communications and information technology.

Building on the progress made by previous grants, this project will focus on approximately 325 artifacts housed in The Henry Ford's Central Storage Building that require attention in these key areas. The Henry Ford is currently investing in upgrades to the HVAC system in the building, which will improve the ability to regulate the storage environment. In conjunction with those improvements, the grant work will address overcrowding and previous environmental issues, which in some cases have led to dirt, mold, and other forms of artifact deterioration. Each artifact will be moved, cleaned, and assessed for conservation needs. Registrar staff will update or create catalog records, working closely with curatorial staff to research additional context.

IMLS grant team members meet to discuss work progress. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

Of the 325 artifacts, about 100 priority artifacts identified by the curators will undergo conservation treatment to digitization standards, will be photographed at high resolution and made available online through The Henry Ford's Digital Collections. Curators and associate curators will create digital content, such as blog posts, to highlight these artifacts. Additionally, curatorial staff will write descriptive narratives for the website, providing essential historical context for public audiences.

The IMLS Collections Specialist takes a reference image of each artifact for the catalog record, such as this 1915 Gentry and Lewis V-8 Automobile Engine for the Model T (left), then, after conservation intervention, Photography Studio staff photographs this priority artifact for publication on digital collections. / Photo by Colleen Sikorski (left), THF802658 (right)

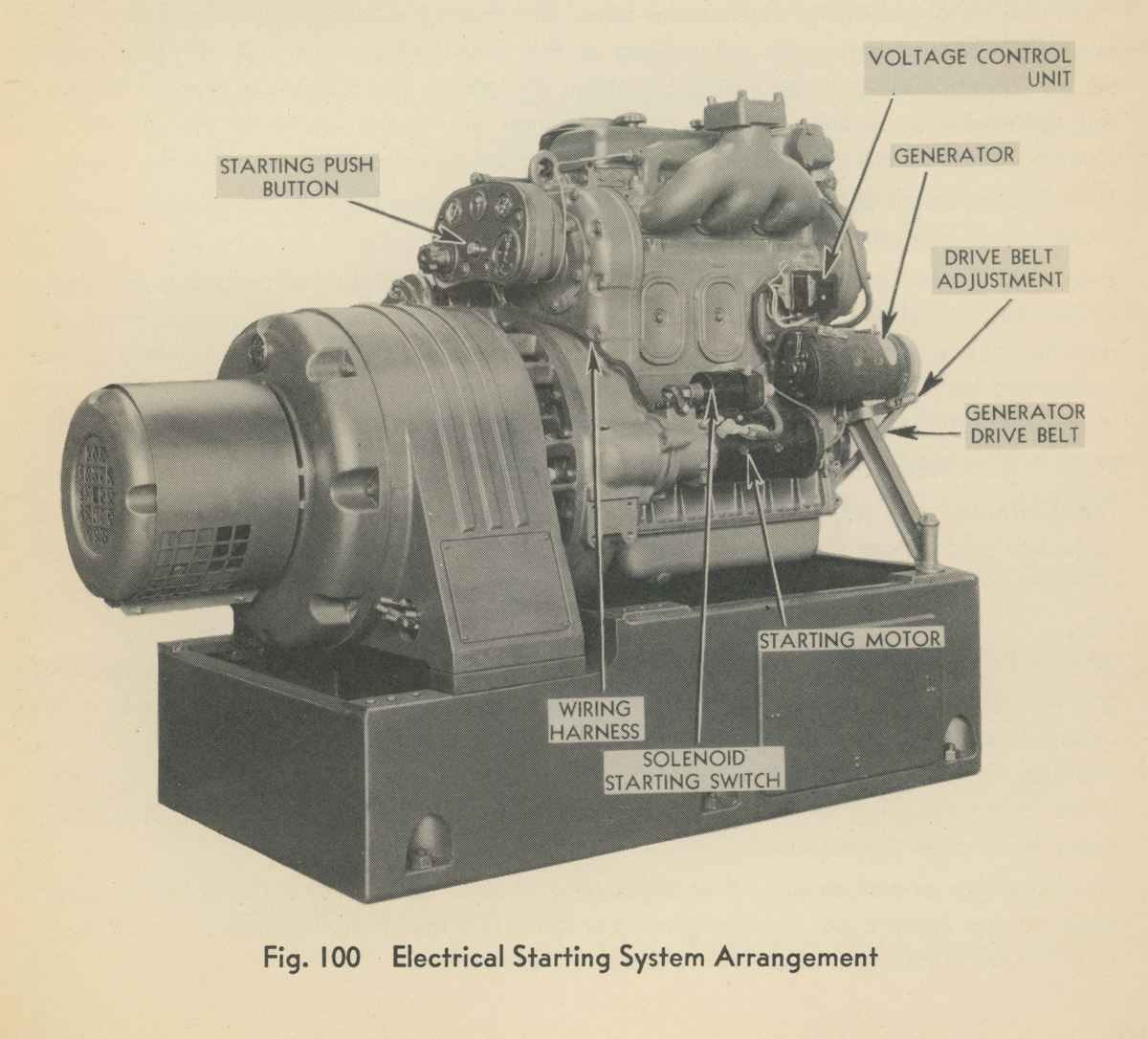

Work on the grant began in the fall of 2024, and the first priority artifact to be conserved is a six-cylinder General Motors 6-71 diesel engine — a legend in its own right. Introduced by General Motors' diesel engine division in 1938, the two-stroke unit powered everything from farm tractors and stationary generators to trucks and buses (including the 1948 GM bus on which Rosa Parks made her historic stand). GM produced variants with two, three, four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen, and twenty-four cylinders, practically guaranteeing there was a Detroit Diesel in whatever size and with whatever horsepower a customer required.

For 40 years, this GM 6-71 engine provided faithful service aboard Jacques Cousteau's ship Calypso / THF802646

The Henry Ford's Detroit Diesel just so happened to be used on one of the most celebrated scientific vessels of the 20th century: Calypso, the former World War II minesweeper converted into a floating laboratory by French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau. From 1950 through 1997, Calypso traveled the world's oceans for Cousteau's research, and for shooting many of his documentary television series and films. Calypso even visited the Great Lakes in 1980, when it traveled from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to Duluth, Minnesota, some 2,300 miles away.

It's important to note that The Henry Ford's engine was not Calypso's source of propulsion. The ship's propellers were driven by two eight-cylinder General Motors diesel engines. Our six-cylinder engine was one of two units that ran the generators that produced electricity. Our engine didn't make the boat go, but it kept the lights on — arguably just as important a task. Of course, it wasn't just lights. Calypso's electric generators powered pumps, hydraulic systems, steering mechanisms, radar and navigation devices, and video equipment, among other necessities.

By the time our engine was decommissioned in 1981, it had been used on Calypso for 40 years, with an estimated 100,000 service hours under its belt. Calypso received two brand-new Detroit Diesel engines as part of a wider refurbishment in anticipation of a voyage to the Amazon River. General Motors gifted the decommissioned engine to The Henry Ford in 1986.

Vintage illustrations, like this one from a 1939 GM manual, guided efforts to conserve the Calypso engine. / THF721888

Through the IMLS grant project, conservators were able to clean the engine of accumulated dirt and dust, treat worn paint, and stabilize damaged gauges and controls. We were also able to replace a long-missing panel surrounding the starter button. Using period General Motors catalogs and manuals in the Benson Ford Research Center, we were able to design and 3D-print a new surround. Once the panel was painted to match, it became visually indistinguishable from the engine's original metal components. (Conservator notes, and inscriptions on the pieces themselves, identify replacement parts so as not to cause confusion in the future.) With that work done, the engine was photographed and given a new and much improved set of digital images on the website.

The Calypso Detroit Diesel is only the first of many important artifacts that will benefit from the IMLS grant and our ongoing work in the Central Storage Building. Stay tuned for future stories. It's a project that promises to be its own voyage of discovery.

This blog was produced by Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, and Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Think about the dishes, bowls, and mugs you often see in diners and restaurants. What are they like? And why are they designed that way? Diner or restaurant ware is typically made from porcelain or stoneware that has been “vitrified,” turning the material into a glass-like substance via high heat and fusion alongside the glaze.

Restaurant ware is designed for practicality. It is thick and sturdy with smooth and rounded contours, which offers a range of benefits. Restaurant ware is durable, less prone to breaking and chipping, and better at retaining heat to keep food warm. It also can handle extreme temperature changes. The vitrification process minimizes silverware marks on the surfaces, keeps harmful chemicals from leaching into food through food-safe glazes, and resists staining and odors. Plus, the glazes are easy to clean, commercial dishwasher safe, and maintain their glossy finish after many washes.

Stacks of plates, saucers, and bowls at the ready for guests at Lamy’s Diner in Henry Ford Museum. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

History of Restaurant Ware

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, people dining outside the home became more common. Early restaurants and diners served meals on fragile porcelain, porous earthenware, or glass not designed to handle the wear and tear of heavy daily use. As a result, pottery companies began experimenting with stoneware, first creating “semi-vitreous” pieces before moving to fully “vitreous” (or glass-like) ceramics.

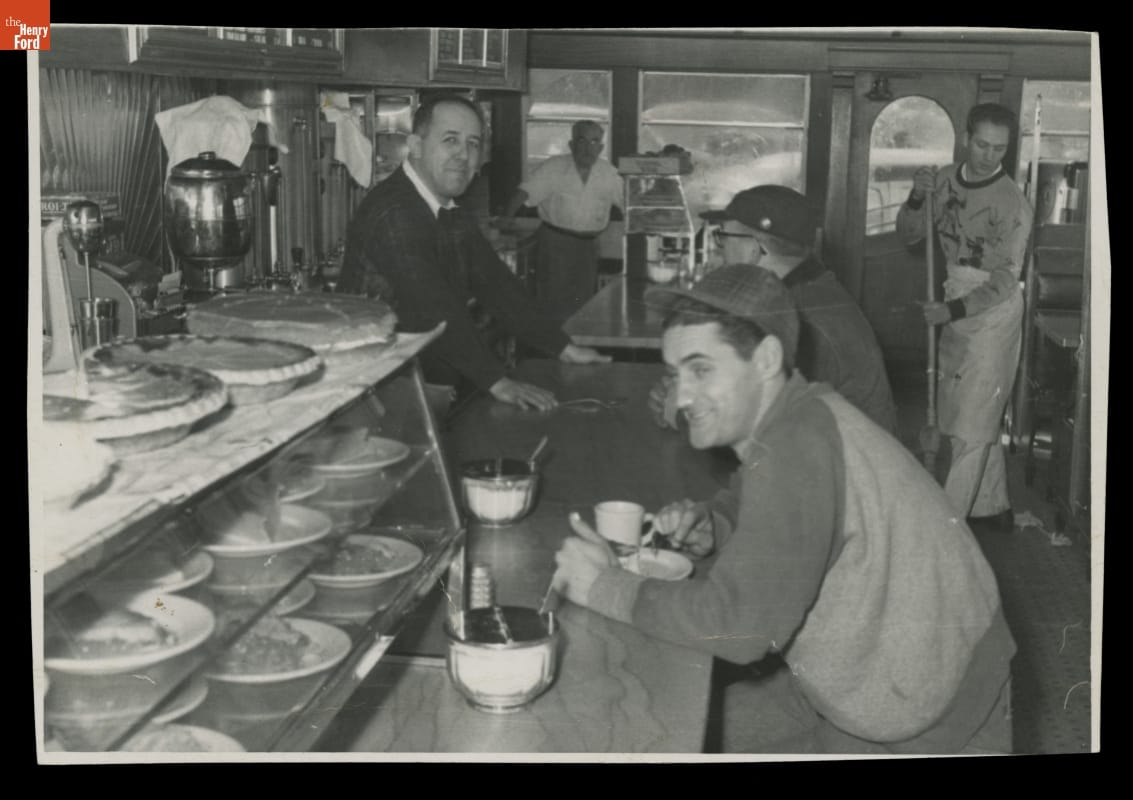

Customers eating and drinking using commercial restaurant ware at the counter inside Lamy’s Diner at its original location in Marlborough, Massachusetts. / THF114397

Buffalo Pottery

One of the first and most notable companies to pursue this industry was Buffalo Pottery, based in Buffalo, New York. Founded in 1901 by soap manufacturer John Larkin, the company initially aimed to produce wares that could be given away as premiums for purchasers of his soap products. Buffalo Pottery produced its first restaurant ware pieces in 1903.

The blue-plate special – a discount-price meal that changed daily – seems to have been named after the plate that it could be served on. This plate with divided sections was made by Buffalo China circa 1930. / THF370830

Incorporated in 1940, Buffalo Pottery changed its name to Buffalo China Inc. in 1956. In 1983, It became a subsidiary of American tableware company Oneida, Ltd. After more than a century of manufacturing, the Buffalo factory was sold in 2004, marking the end of its production.

Buffalo Pottery was also known for its art pottery, decorated by artists and craftspeople to showcase artistic aspirations on utilitarian pieces like this candlestick decorated by Mabel Gerhardt in 1911. / THF176916

Syracuse China Company

Another significant manufacturer in restaurant ware production was Syracuse China Company, which originated as the Onondaga Pottery Company in 1871 in Syracuse, New York. The company initially made non-vitrified dinnerware, used both in homes and in restaurants. In 1896 they introduced vitrified stoneware with a rolled edge. By 1924 Syracuse China built a factory dedicated to manufacturing only commercial ware

After World War II, many US corporations, like General Motors, built engineering and manufacturing campuses that included employee cafeterias. Companies such as Syracuse China made dishes, bowls, and mugs or cups with companies’ logos for use in these cafeterias. / THF194982

Syracuse China made dishes for Sears Coffee Houses, small diner-style eateries inside Sears department stores. / THF195542

In 1966 Onondaga Pottery Company officially changed its name to Syracuse China Corporation. In 1993 it became Syracuse China Company, before being acquired in 1995 by Libbey, Inc. a U.S.-based glass manufacturer. By 2009 all production was moved out of North America, bringing an end to 138 years of production in Syracuse.

Restaurant Ware Patterns

Restaurant ware was typically plain or minimally decorated with color and simple patterns. Many companies produced similar designs, allowing diners and restaurants to easily buy replacements or additional pieces from a variety of manufacturers. One popular design was a white background with one to three green stripes.

The white with green stripes pattern on a bowl by Homer Laughlin China Company, 1966 (left) and on a divided plate by Buffalo China Company, 1952 (right). / THF197347 (left), THF197410 (right)

A variation on the green-and-white theme was a design of wave-like or scallops along the rims of bowls, plates, or mugs. Shenango China, America’s second-largest manufacturer of food service wares, called their pattern Everglade. Buffalo China offered a version called Crest Green, while Mayer China referred to theirs as Juniper, and Syracuse China called it Wintergreen.

Shenango China Co.’s Everglade pattern on a cup and saucer, 1961 / THF102560

Another distinctive pattern called “Pendleton” featured a deep ivory or tan base with three stripes: red, yellow, and green. This design was likely inspired by blankets manufactured by Pendleton Woolen Mills since the early 1900s. The Glacier National Park blanket’s colors and markings are reminiscent of those distributed at frontier trading posts in exchange for furs.

Pendleton-pattern ware on display in Henry Ford Museum (left), and a Buffalo China Company cup. / Photo by Aimee Burpee (left), THF197343 (right)

Victor Mugs

Picture a mug of coffee at your local diner. Is it a mug that looks like this?

Victor Insulator mug from the Rosebud Diner in Somerville, Massachusetts. / THF197331

In the late 19th century, Fred M. Locke started Locke Insulator Company (later Victor Insulators) in Victor, New York, to manufacture glass and ceramic insulators for electrical and telegraph wires. By the mid-1930s, the plant in Victor had been retooled with four new kilns when the company was considering expanding into heavy-duty, high-quality dinnerware.

Ceramic and glass insulator made by Locke’s company in Victor, New York, circa 1898, and used on early transmission lines in the San Joaquin Valley, California. / THF175272

When WWII broke out, the U.S. government put out a call for durable dinnerware for use aboard naval ships. The Navy needed coffee mugs that were less likely to slide off surfaces, but if they did, could withstand the fall. Victor Insulators won the contract and began producing thick-walled, straight-sided handleless mugs, each with a rough ring on the bottom. Drawing the company's expertise in insulator technology, these mugs were crafted from high-quality clays fired at 2,250°F. The mugs proved so successful with the Navy that Victor quickly began making mugs with handles for the war effort. The handles were attached by one of three women employed at the factory for that specific task. The mug’s design also evolved, with the introduction of curved sides that made it easier to grip. After the war, these durable mugs were in high demand for diners and restaurants across the United States.

For several decades, Victor mugs were a staple of American dining. But by the 1980s, cheap knockoffs flooded the market, and Victor Insulators found it difficult to compete. By 1990 the company phased out the mugs, although they continue to produce ceramic insulators to this day.

Hot coffee and slice of cherry pie served at Lamy’s Diner on Homer Laughlin China Company mug and plate. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford

Americans on Ice: Skating and Skate Technology in the United States

Archeological evidence suggests that ice skating began as early as 4,000 years ago in northern Europe. Travelling on foot in winter across snowy, icy landscapes for trade, hunting, and community gatherings was slow and exhausting. People first used sharpened animal bones attached to footwear by leather strips, along with poles, to propel themselves across frozen rivers, ponds, and lakes – faster and less taxing during harsh winter months.

Currier & Ives published this lithograph in 1868 of skaters on a frozen lake or pond at night, skating by moonlight. / THF118602

As a pastime, ice skating became popular in the United States in the mid-19th century. Initially, people skated on frozen local rivers and ponds, but as artificial ice-making improved, skating moved indoors to purpose-built rinks. Temperature-controlled buildings and artificial ice technology made it possible for ice skating to spread south and west from New England and the Upper Midwest. Skating clubs started forming across the country as early as 1849, and these clubs hosted evening skating events with live musical accompaniment .

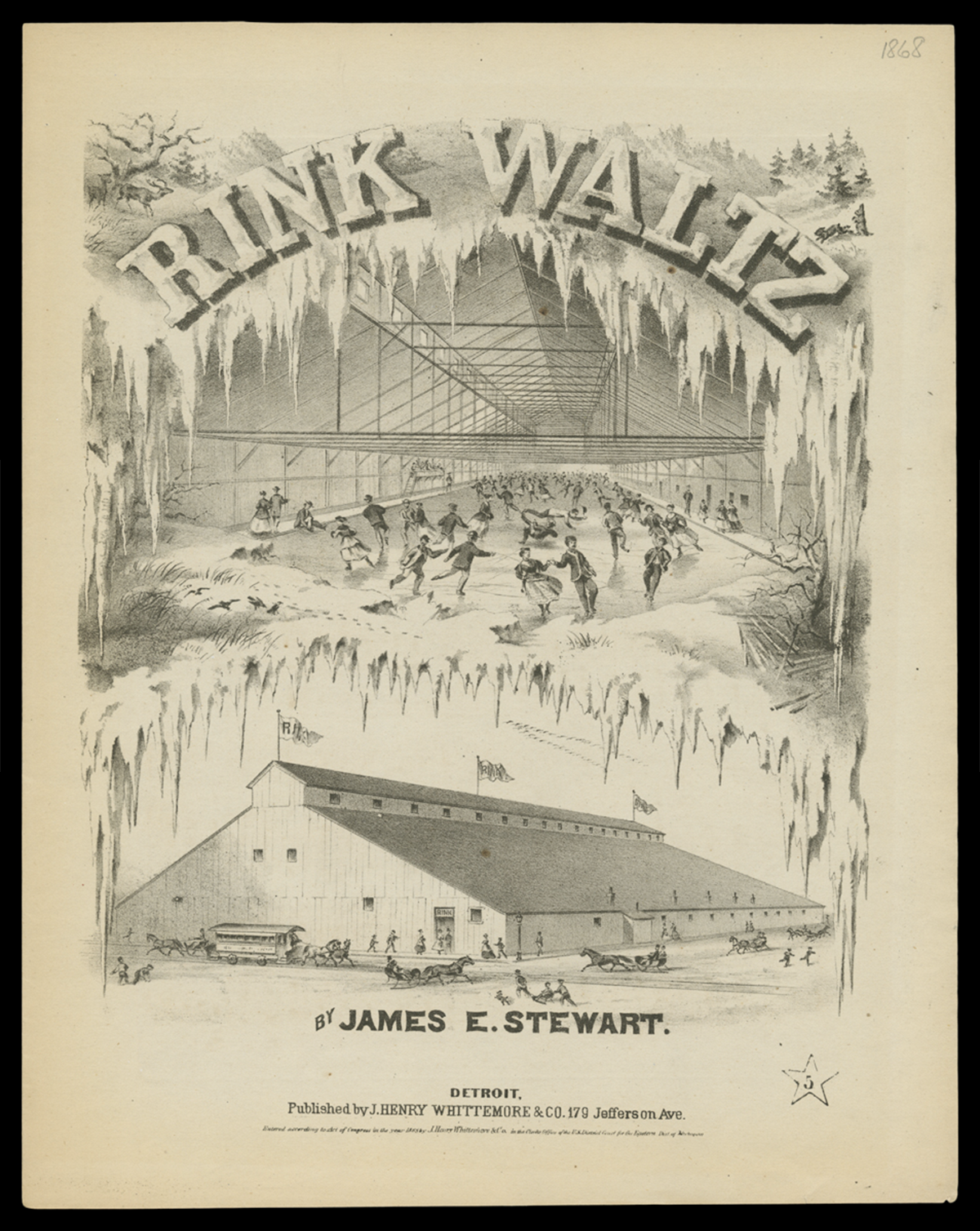

The song Rink Waltz was written and published in Detroit in 1868. Its cover has interior and exterior renderings of the Detroit Skating Rink, which opened in 1866. / THF720452

Ice skating’s popularity peaked in the 1860s and 1870s. During this time, many patents for skates were issued to ice skate manufacturers. Publications on skating skills and safety, along with songs about skating, became widespread. Other products, such as handheld kerosene lanterns to illuminate outdoor skating at night, also show how ingrained skating had become in American culture. Women in particular embraced ice skating, which was promoted as healthy exercise and one of the few athletic activities socially acceptable for women at that time.

Lighting companies such as R.E. Dietz patented small kerosene lanterns for nighttime skaters, particularly women. / THF802186 (left), THF802187 (right, crop)

Improving Skate Technology

Early skates were made using animal bones. In the 13th and 14th centuries, craftspeople started to fabricate metal blades, which were inserted into wooden platforms. Straps, ropes, or ties secured the platform to skaters’ everyday footwear. These early blades were long and curled up in front of the toes, helping the skater navigate uneven and rough ice on frozen waterways. This type of skate was likely the kind first imported into the United States from Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Blacksmiths and carpenters in northern American towns and cities also produced skates, and some skaters even made their own.

Ice skates with crude wood platforms, curled metal blades, and leather straps. / 29.1871.2, From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Photo by Aimee Burpee.

Unfortunately, ties or straps were often unreliable. They did not secure the foot and shoes firmly in the skates, as the foot could slide side to side or even slip off the platform. To improve the attachment, manufacturers and craftspeople added a metal spike on the top of each wooden platform, which went into the heel of the shoe, and occasionally small spikes in the forefoot for additional attachment.

These Douglas, Rogers & Co. skates with 1863 patent date have a spike in the heel to attach the shoe to the platform, and tempered metal blades. Straps went through the holes in the sides of the platforms / THF802180

Eventually metal platforms replaced wooden ones, which cracked or splintered and required frequent repairs. The earliest metal platform skates still used ties and straps, but eventually switched to keys and clamps that more securely attached and tightened the skates to the wearer's shoes. By the 1890s, fully metal skates allowed people to simply “step into” the skate, with automatic clamps securing the skate around the shoes. These metal skates were stronger and more dependable, making them especially appealing to the rapidly growing market of hockey players and early figure skaters.

Barney & Berry patented these skates 1896, with clamps that hooked around the shoe when you stepped into them, no fiddling with straps or tightening with a skate key was necessary. / THF802173

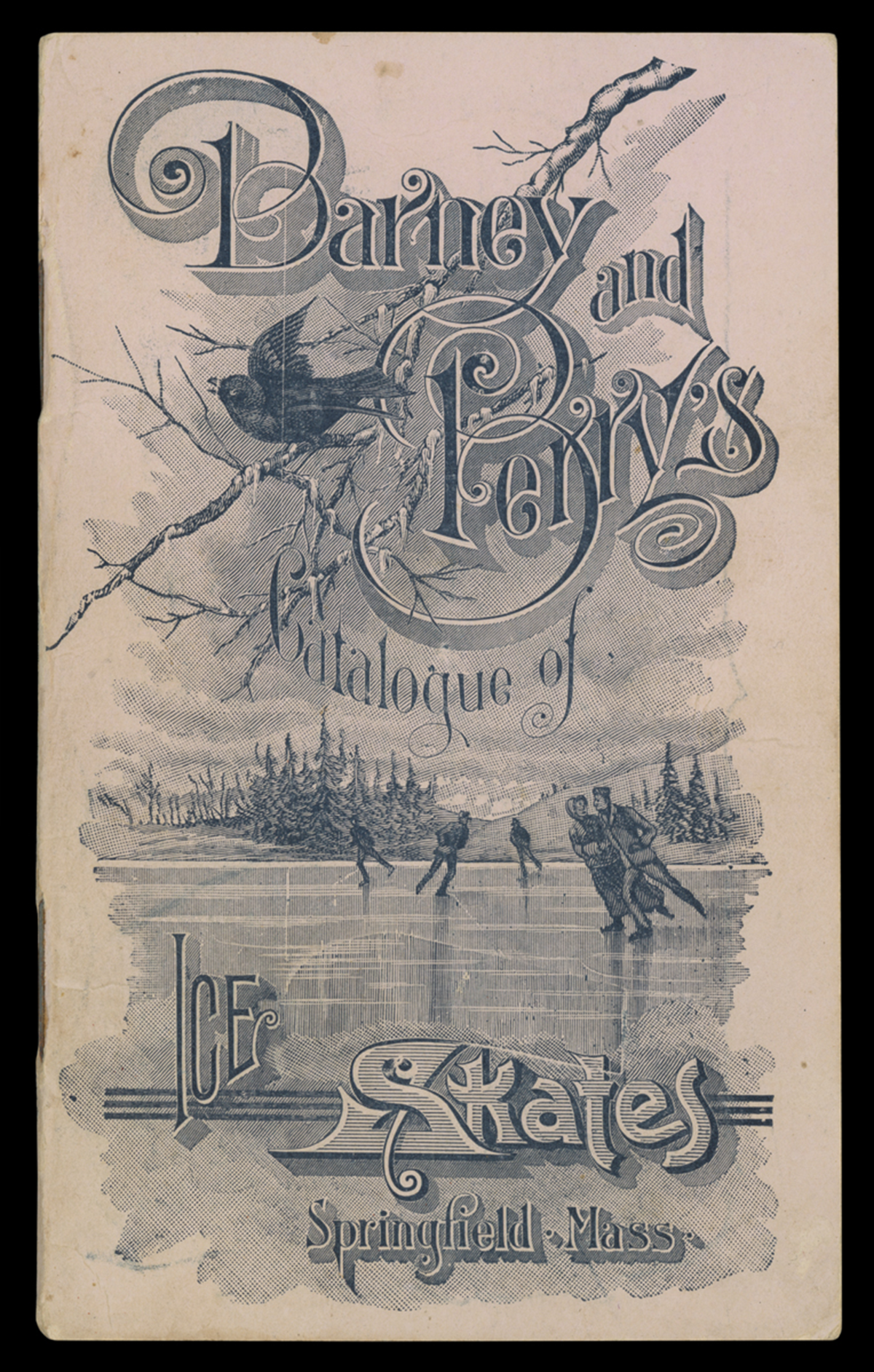

Barney & Berry was one of the top innovators and manufacturers of ice skates. Hardware, sporting goods, and toy stores could choose models and styles from this 1894-1895 wholesale catalog to sell to customers. / THF720461

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ice skates became one-piece boots, resembling the skates we use today. These skates provided greater support and stability, with the blade attached to a steel sole and integrated into a boot. While earlier skates started the development of specialized skates for figure skating, hockey, and speed skating, the one-piece boot skate further refined these specializations.

Children and adults could rent skates from the Belle Isle Pavilion and skate on adjacent Lake Takoma on Belle Isle in Detroit, Michigan, around 1900. / THF119081

These all-in-one boot skates belonged to Henry Ford. He enjoyed skating on a frozen pond on his Fair Lane property in Dearborn, Michigan / THF166350

Today, figure skates combine slim leather boots with toe picks for spins and jumps. Hockey skates have shorter blades for quick maneuvering, with padded foot and ankle protection. Speed skates feature longer blades and a more streamlined boot profile to decrease wind resistance.

The skates of the past led to the skates of today. And the skates of the future will continue to evolve as innovative technologies, designs, and materials are developed and implemented.

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford

The Art of Provenance Research: Playing Detective in Our Collections

Thomas Edison Punching the Time Clock at His West Orange, New Jersey Laboratory, August 27, 1912. Read on for more on this provenance research story! / THF108339

As my colleague Laura Lipp discusses in her blog post on cataloging, The Henry Ford’s registrar’s office sometimes “plays detective” by engaging in provenance research to determine the history of the ownership of an artifact – and to deepen our knowledge of the stories behind our artifacts.

First, a little background on our early collecting.

In the 1920s and 1930s, The Henry Ford received thousands upon thousands of artifacts from sources all over the country. Staff at that time attached paper and metal tags to the artifacts, writing their source information (either the donor or the point of purchase) on the tags. They also typically included the geographic location of the source and a date. In the 1950s, staff began to catalog the collection, assigning object identification numbers (“object IDs”) and creating files that held any documentation or correspondence about the artifacts. The object ID is the unique number assigned to an artifact that indicates what year the artifact came in, and links it to its “provenance”—the source it came from and any associated stories.

On occasion over the years, staff encounter artifacts that have lost their tags, or the tags have crumbled or become illegible, so the artifacts have been disassociated with their histories. At this point, the detective work begins, to figure out the artifact’s provenance. We have many internal resources at hand to perform provenance research – our catalog database, our files and correspondence, photographs of artifacts, inventories, original cataloging cards, and more. We also use the Internet, oftentimes turning to online genealogical databases of census and demographic records.

An example of disassociated artifacts came up one day when someone wanted to know what artifacts we had related to Alexander Hamilton (can’t imagine why). Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable and I started looking into it. Upon searching our database, we discovered that we had received some silver that descended in the Hamilton family to Alexander and Eliza’s great-great granddaughter, Mary Schuyler Hamilton: a “sugar bowl” and candlesticks. Unfortunately, the lost tags meant we had to work through all our silver records to see what might match.

We looped in Image Services Specialist Jim Orr and he found a photo of these silver artifacts taken around the time they arrived at our museum. Now we at least knew what they looked like! The sugar bowl was not a sugar bowl – with its pierced sides, the sugar would have leaked out. We expanded our search to other silver bowls and dishes, and the curator and I came across a record for a “sweetmeat” dish that sounded promising. The record had a silver project inventory number and a location. After a quick trip to one of our storage rooms, lo and behold, the “sweetmeat dish,” a bit tarnished, matched the artifact in the image! One down, candlesticks to go.

Sweetmeat Dish, Used by Alexander Hamilton, 1780-1800 / THF169541

After an unsuccessful stop in a storage area where there are many candlesticks, I returned to my desk and started going through all our silver candlestick records. Just as I was getting ready to call it a day, I reached a record, took a double-take, and called the curator over from his office to look at it. “OH MY …!” was the exclamation all my co-workers heard, “YOU FOUND THEM!” We reunited the candlesticks with the sweetmeat dish, had them photographed, and they are now viewable online. I can easily state that was one of my proudest days.

Candlesticks, Used by Alexander Hamilton, 1780-1800 / THF169539

Most of the time, we know who donated artifacts, and where the donors lived. When looking to further document these artifacts in our collection, we do research into the donors to fill in information that wasn’t originally captured. While working on a project related to agricultural equipment, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment Debra Reid and I were interested in learning more about some artifacts that were donated by Iva and Ruby Fuerst, such as this potato digger and this hand dibble.

Potato Digger Donated to The Henry Ford by Iva and Ruby Fuerst / THF97302

Digging into the Internet and genealogical records, I was able to reconstruct a small family tree. Ruby and Iva’s grandparents, Lorenzo and Barbara Fuerst, immigrated from Germany and were farmers in Greenfield Township (now Detroit) starting in the late 1850s. After the passing of Barbara in 1905, Iva and Ruby’s father Jacob, who had an adjacent farm, continued farming in that area until he sold it in 1918 and bought a farm in Novi Township. We now know that some of the equipment was likely used first on the farms in Detroit and later in Novi. Ruby and Iva, with no heirs to pass the land to, sold most of the Novi farm to the city around 1970. It is now known as Fuerst Park, and you can find a photo of young Ruby and Iva in this brochure.

Hand Dibble Donated to The Henry Ford by Iva and Ruby Fuerst / THF171836

It's not just 3D artifacts that need provenance research, but also some of our archival holdings. One day, staff encountered some timecards in the archives that appeared to have been used by Thomas Edison. Curious to know more and hopeful to verify that exciting association, Registrar Lisa Korzetz investigated the matter and was able to find correspondence with the donor, Miller Reese Hutchinson, chief engineer at Edison’s West Orange Laboratory. Hutchinson details in his letter that the four timecards he was donating were the first four cards used by Edison in 1912 after Hutchinson had installed a new time clock at the laboratory. He also donated a photograph of Edison using the timecards at the time clock. Hutchinson was determined for a week to try to capture Edison using the timecards and clock, and finally succeeded on the last day of the week!

Time Card Punched by Thomas Edison at His West Orange Laboratory, for the Week Ending August 27, 1912 / THF108331

Today, when cataloging new artifacts for the collection, we document the provenance via the background information that the curator gleans from the donor or point of purchase. We do additional research to verify and fill in any historical background. We apply the object ID directly to the artifact in a manner approved by Conservation – different methods on different materials. We also make sure the number is discreet and easily reversible – meaning it can be removed without any adverse effects to the artifact. By using these standard museum practices to document and identify artifacts, we assist our curatorial colleagues in their pursuit to interpret and exhibit our collections to the public.

Continue Reading

digitization, collections care, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, #digitization100K, research, by Aimee Burpee