Posts Tagged by peter kalinski

Barney Oldfield: America’s Racer

"You know me, Barney Oldfield" was the classic catchphrase of one of America's earliest celebrity sports figures. Indeed, during the nascent period of the automobile, most every American knew Berna “Bernie” Eli Oldfield (1878–1946). He became the best-known race car driver at a time when the motor buggy was catching the imagination and passion of a rapidly changing society. Oldfield cut a populist swath across turn-of-the century American society and, in the process, helped define an emerging cult of celebrity.

Bicycle Beginnings

Barney Oldfield Riding the "Blue Streak" Bicycle on the Salt Palace Board Track, Salt Lake City, Utah, circa 1900 / THF111772

One of the consistent themes of Oldfield's early years was a restlessness and desire for bigger, brighter, and better things in life. As a teenager, Oldfield worked odd jobs in Toledo, Ohio, earning money to buy his own bicycle to ride in local and regional road and endurance races. An attempt at professional boxing ended after Oldfield contracted typhoid fever. He returned to racing bicycles for company-sponsored teams and sold parts in the off-season. Throughout the 1890s, Oldfield was part of a team of riders that barnstormed across the Midwest, racing in the new "wood bowl" tracks that were sprouting up across the region. Oldfield quickly realized the need to appeal to audiences beyond the track. He branded himself the "Bicycle Racing Champion of Ohio" and promoted a "keen formula for winning," wearing a bottle of bourbon around his neck during races but telling reporters the liquid inside was vinegar.

Shift to Auto Racing

Tom Cooper and Barney Oldfield Seated in Race Cars, circa 1902 / THF207346

Americans were fascinated with quirky and expensive motor buggies. These boxy, carriage-like vehicles appealed to Americans’ desire for new, loud, audacious, and fast entertainment. During the winter of 1899, Oldfield reconnected with an old bicycle racing companion, Tom Cooper, who had just returned from England with a motorized two-wheeler (an early motorcycle). Cooper was going to demonstrate the vehicle at a race in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, near Detroit, in October 1901. He asked Oldfield, who began riding motorcycles himself around this time, to come along. Cooper and Oldfield were a preliminary exhibition before the main event: a race between local "chauffeur" Henry Ford and the most well-known and successful automobile manufacturer of the day, Alexander Winton.

After the Grosse Pointe event, Oldfield and Cooper pursued gold mining in Colorado. When that ended in failure, Cooper headed to Detroit to focus on automobiles. Oldfield took the motorized cycle on a circuit of Western bicycle tracks, setting records along the way before returning to Detroit in the fall of 1902 at Cooper’s request. Cooper had purchased Henry Ford’s “999” race car and wanted Oldfield to drive it. "The Race" between the “999” and Alexander Winton's "Bullet" captured the imaginations of not only Detroit's automotive elite, but the general population as well. When Oldfield piloted the “999” to victory over Winton's sputtering “Bullet,” the news spread like wildfire across Detroit, the Midwest, and eventually the nation.

Beyond the immediate thrill of the race itself, Barney Oldfield, the "everyman" bicycle racer from the heartland, appealed to a wide segment of American society rushing to embrace the motor car. As the Detroit News-Tribune reported after the race, "The auto replaced the horse on the track and in the carriage shed. Society sanctioned yesterday's races. And not only society, but the general public, turned out until more than five thousand persons had passed the gatekeepers.” Barney Oldfield became the face of racing for the "general public" and helped to democratize not only racing entertainment, but also automobiles in general, as vehicles moved out of the carriage house and into backyard sheds.

Barney Oldfield Driving the Ford "999" Race Car, circa 1903 / THF140144

Celebrity Status

Over the next 15 years, Barney Oldfield established multiple world speed records and gained notoriety wherever he went. He added an iconic unlit cigar to his racing persona and perfected the roguish image of a daredevil everyman. After a brief stint driving for Winton, Oldfield took the wheel of a Peerless racer, the "Green Dragon," and established himself as America's premier driver.

Barney Oldfield Behind the Wheel of the Peerless "Green Dragon" Racecar, circa 1905 / THF228859

By 1904, Oldfield held world records in the 1-, 9-, 10-, 25-, and 50-mile speed categories. In 1907, Oldfield tried his hand at stage acting when he signed on to appear in a new musical, The Vanderbilt Cup. Over a 10-week run and a brief road tour, Oldfield “raced” his old friend Tom Cooper in stationary cars as backdrops whirled behind them and stagehands blew dirt into the front rows of the theater. The following year, Oldfield entered the open road race circuit and quickly added to his legend by sparking a feud with one of the emerging stars of the day, Ralph De Palma. In March 1910, Oldfield added the title "Speed King of the World" to his resume, driving the "Blitzen Benz" to an astonishing 131.7 miles per hour on Daytona Beach in Florida.

Barney Oldfield Driving the "Blitzen Benz" Car on a Racetrack, 1910 / THF228871

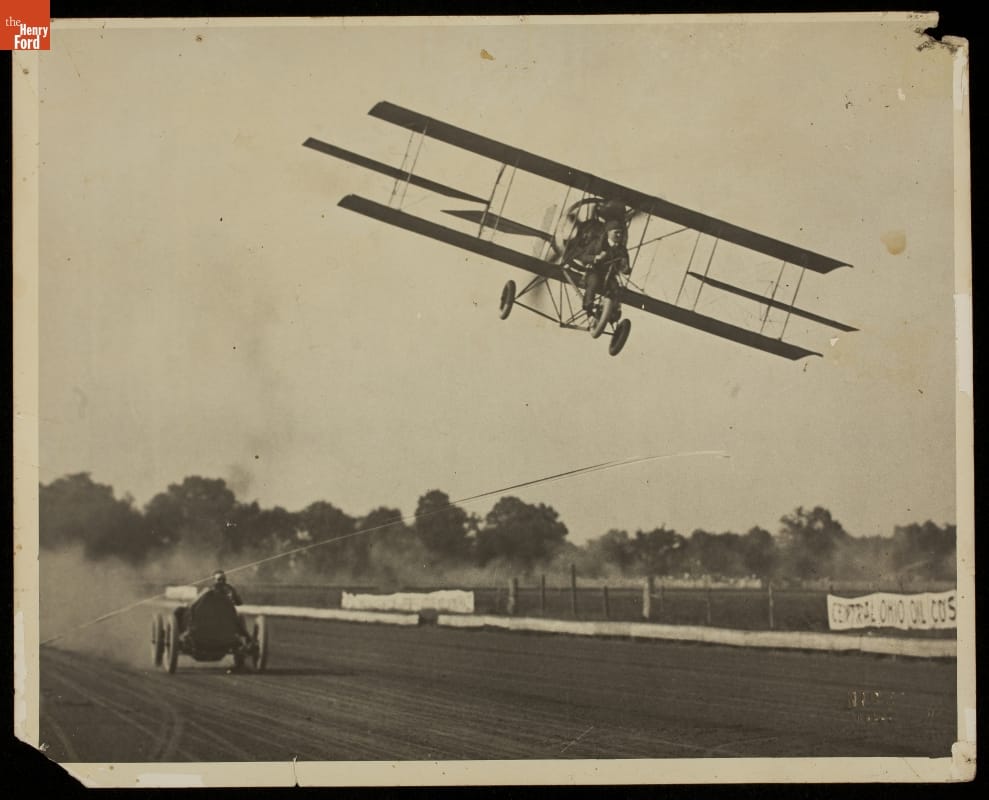

Oldfield flouted the conventions of his time, both on and off the track. He was notorious for his post-race celebrations, womanizing, and bar fights. Oldfield’s rebellious streak kept him under the scrutiny of the American Automobile Association (AAA) and, in 1910, he became the first true "outlaw" driver when he was suspended for an unsanctioned spectacle race against the heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson. Undaunted, Oldfield and his manager set up dates at county and state fairs across the country, holding three-heat matches against a traveling stable of paid drivers. Oldfield padded his reputation by adding an element of drama to these events—he would lose the first match, barely win the second, and, after theatrically tweaking and cajoling his engine, win the third match. During this time, Oldfield also became a product spokesman (perhaps most notably for Firestone tires) and began racing a fellow showman, aerial barnstormer Lincoln Beachey, in matches pitting “the Dare Devil of the Earth vs. the Demon of the Skies for the Championship of the Universe!”

Barney Oldfield and Lincoln Beachey Racing, Columbus, Ohio, 1914 / THF228829

Towards the end of his driving career, Oldfield made a final splash in the racing world with the Harry Miller-built "Golden Submarine," establishing dirt-track records from one to one hundred miles. Throughout the 1917 season, Oldfield drove the Golden Sub in a series of matches on dirt and wood tracks against his old rival Ralph De Palma, eventually winning four out of the seven races. Oldfield retired from competition racing in 1918 after winning two matches in Independence, Missouri. In typical Oldfield fashion, he ran the last race under AAA suspension for participating in an earlier unsanctioned event.

Barney Oldfield Driving "Golden Submarine" Race Car at Sheepshead Bay Board Track, Brooklyn, New York, 1917 / THF141856

Oldfield continued to keep himself at the fore of America's sports entertainment culture. In addition to ceremonial "referee" jobs at various races, he rubbed elbows with American movie, stage, and music stars and continued his rambunctious lifestyle. Between 1913 and 1945, Oldfield appeared in six movies (usually as himself) and also tried his hand as a road tester for Hudson Motor Company, salesman, bartender, club owner, and spokesman. Finally, in an attempt to raise funds to build another land-speed racer with Harry Miller, Oldfield staged a unique publicity and fundraising event. In 1933, outside Dallas, Texas, he drove an Allis-Chalmers farm tractor to a record 64.1 miles per hour.

Barney Oldfield Advertising Postcard for Plymouth Automobiles, circa 1935 / THF228879

Fittingly, Barney Oldfield's last public appearance was at the May 1946 Golden Jubilee of the Automobile Industry held in Detroit. Oldfield was fêted for his foundational role in what had become one of the largest industries in the nation. He shared the main speaker's table with automotive icons including Henry Ford, Ransom Olds, and Frank Duryea, and he accepted a “trophy of progress” for his role in automotive history. Barney Oldfield passed away in October 1946, having lived—in the words of one passionate fan—“such a life as men should know.”

For more, check out our archival collection on Barney Oldfield, browse artifacts related to him in our Digital Collections, or visit the “Showmanship” zone of the Driven to Win: Racing in America exhibition in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

This post by Peter Kalinski, former Archivist at The Henry Ford, originally ran in 2014. It has been updated by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Driven to Win: Racing in America

- Henry Ford's “Sweepstakes” Celebrates its 120th Anniversary

- 1956 Chrysler 300-B Stock Car

- 1965 Goldenrod Land Speed Race Car

Ohio, 20th century, 19th century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Michigan, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, Detroit, cars, by Saige Jedele, by Peter Kalinski, bicycles, archives

African American Workers at Ford Motor Company

No single reason can sufficiently explain why in a brief period between 1910 and 1920, nearly half a million Southern Blacks moved from farms, villages, towns and cities to the North, starting what would ultimately be a 50-year migration of millions. What would be known as the Great Migration was the result of a combination of fundamental social, political and economic structural problems in the South and an exploding Northern economy. Southern Blacks streamed in the thousands and hundreds of thousands throughout the industrial cities of the North to fill the work rolls of factories desperate for cheap labor. Better wages, however, were not the only pull that lured migrants north. Crushing social and political oppression and economic peonage in the South provided major impetus to Blacks throughout the South seeking a better life. Detroit, with its automotive and war industries, was one of the main destinations for thousands of Southern Black migrants.

In 1910 Detroit’s population was 465,766, with a small but steadily growing Black population of 5,741. By 1920 post-war economic growth and a large migration of Southerners to the industrialized North more than doubled the city’s population to 993,678, an overall increase of 113 percent from 1910. Most startling, at least for white Detroiters, was the growth of the city’s Black population to 40,838, with most of that growth occurring between 1915 and 1920.

Photo: P.833.34535 Fordson Tractor Assembly Line at the Ford Rouge Plant, 1923

Before the war, Detroit’s small Black community was barely represented in the city’s industrial workforce. World War I production created the demand for larger numbers of workers and served as an entry point for Black workers into the industrial economy. Growing numbers of Southern migrants made their way to Detroit and specifically to Ford Motor Company to meet increased production for military and consumer demands.

By the end of World War I over 8,000 black workers were employed in the city’s auto industry, with 1,675 working at Ford. Many of Ford’s Black employees worked as janitors and cleaners or in the dirty and dangerous blast furnaces and foundries at the growing River Rouge Plant’s massive blast furnaces and foundries. But some were employed as skilled machinists or factory foremen, or in white-collar positions. Ford paid equal wages for equal work, with Blacks and whites earning the same pay in the same posts. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Ford Motor Company was the largest employer of Black workers in the city, due in part to Henry Ford’s personal relationships with leading Black ministers. Church leaders in the Black community helped secure employment for hundreds and possibly thousands, but more importantly, they also helped to mediate conflicts between white and Black workers.

Photo: P.833.55880 African American workers at Ford Motor Company’s Rouge River Plant Cyanide Foundry, 1931

Photo: P.833.57788 Foundry Workers at Ford Rouge Plant, 1933

Photo: P.833.59567 Pouring Hot Metal into Molds at Ford Rouge Plant Foundry, Dearborn, Michigan, 1934

In addition to jobs, Ford Motor Company provided social welfare services to predominantly Black suburban communities in Inkster and Garden City during the depths of the Great Depression. Ford provided housing and fuel allowances as well as low-interest, short-term loans to its employees living in those communities. Additionally, Ford built community centers, refurbished several schools and ran company commissaries that provided inexpensive retail goods and groceries. (You can learn more about the complicated history of Ford and Inkster in The Search for Home.)

You can learn more by visiting the Benson Ford Research Center and our online catalog.

Peter Kalinski is Racing Collections Archivist at The Henry Ford. This post was last updated in 2020 with additional text by Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson.

20th century, Michigan, labor relations, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, by Peter Kalinski, African American history

Pomona, Riverside, Santa Barbara, Laguna Seca, Sebring, Le Mans, Indianapolis…race fans know that these are the tracks where legends were made.

Gurney, Shelby , Foyt, Hall, Clark…driving legends who defined modern automobile racing. If it had an engine and rolled, they raced it.

Cobra, Lotus, Lola, Porsche, Corvette, Ferrari…cars that defied the laws of physics and the test of time.

Between 1960 and 1990, tracks, drivers and cars combined to create a memorable era in automobile racing, and one of the best-known photograph collections documenting this era is now accessible. Selected images from the Dave Friedman collection are now available for viewing at The Henry Ford’s Flickr page. More than 10,000 images have been uploaded since the beginning of 2012, with many more to come!

During the 1950s and 1960s, American auto racing underwent a radical transformation, evolving from a sport of weekend racers in their home-built hot rods and dragsters to professional teams driving powerful race cars in competitions all over the world. Photographer Dave Friedman had a front row seat for the action during this important transition, capturing the excitement, the grit and the glamour - and creating some of the most iconic images of American motor sports of that era.

In 1962 Friedman was hired as staff photographer for Shelby-American Inc., the racing design and construction shop owned by a former driver, the late Carroll Shelby. While with Shelby-American Inc., Friedman had the unique opportunity to document the development of one of racing’s iconic stable of cars, the Shelby Cobras. In 1965, Friedman continued to capture the dynamic innovations of Shelby and Ford Motor Company as he documented the development of the record-setting Ford Mark IV race car that was the first American-designed and built car to win the grueling 24 Hours of Le Mans race in 1967 . Friedman continued to pursue his passion for motor sports into the 1990s, when he refocused his lens on a new art form – classical ballet.

In 2009, The Henry Ford acquired the unique collection of this internationally renowned photographer, author and motion picture still photographer. The Dave Friedman collection consists of over 200,000 unique images, including photographs, negatives, color slides and transparencies. The collection also includes programs, race results and notes from across the United States and around the world. Dating between 1949 and 2003, the images and programs illustrate the transition of auto racing from dirt tracks and abandoned airfields to super speedways.

The Dave Friedman collection is a unique resource that documents in subtle shades the art, power and passion of automobile racing in the second half of the 20th century.

What's your favorite moment in automotive racing history? Tell us in the comments below, or check out Racing In America for more details on these iconic races and more.

Peter Kalinski is an archivist at the Benson Ford Research Center, part of The Henry Ford.

20th century, archives, race cars, race car drivers, racing, photography, photographs, cars, by Peter Kalinski