Posts Tagged bicycles

Barney Oldfield: America’s Racer

"You know me, Barney Oldfield" was the classic catchphrase of one of America's earliest celebrity sports figures. Indeed, during the nascent period of the automobile, most every American knew Berna “Bernie” Eli Oldfield (1878–1946). He became the best-known race car driver at a time when the motor buggy was catching the imagination and passion of a rapidly changing society. Oldfield cut a populist swath across turn-of-the century American society and, in the process, helped define an emerging cult of celebrity.

Bicycle Beginnings

Barney Oldfield Riding the "Blue Streak" Bicycle on the Salt Palace Board Track, Salt Lake City, Utah, circa 1900 / THF111772

One of the consistent themes of Oldfield's early years was a restlessness and desire for bigger, brighter, and better things in life. As a teenager, Oldfield worked odd jobs in Toledo, Ohio, earning money to buy his own bicycle to ride in local and regional road and endurance races. An attempt at professional boxing ended after Oldfield contracted typhoid fever. He returned to racing bicycles for company-sponsored teams and sold parts in the off-season. Throughout the 1890s, Oldfield was part of a team of riders that barnstormed across the Midwest, racing in the new "wood bowl" tracks that were sprouting up across the region. Oldfield quickly realized the need to appeal to audiences beyond the track. He branded himself the "Bicycle Racing Champion of Ohio" and promoted a "keen formula for winning," wearing a bottle of bourbon around his neck during races but telling reporters the liquid inside was vinegar.

Shift to Auto Racing

Tom Cooper and Barney Oldfield Seated in Race Cars, circa 1902 / THF207346

Americans were fascinated with quirky and expensive motor buggies. These boxy, carriage-like vehicles appealed to Americans’ desire for new, loud, audacious, and fast entertainment. During the winter of 1899, Oldfield reconnected with an old bicycle racing companion, Tom Cooper, who had just returned from England with a motorized two-wheeler (an early motorcycle). Cooper was going to demonstrate the vehicle at a race in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, near Detroit, in October 1901. He asked Oldfield, who began riding motorcycles himself around this time, to come along. Cooper and Oldfield were a preliminary exhibition before the main event: a race between local "chauffeur" Henry Ford and the most well-known and successful automobile manufacturer of the day, Alexander Winton.

After the Grosse Pointe event, Oldfield and Cooper pursued gold mining in Colorado. When that ended in failure, Cooper headed to Detroit to focus on automobiles. Oldfield took the motorized cycle on a circuit of Western bicycle tracks, setting records along the way before returning to Detroit in the fall of 1902 at Cooper’s request. Cooper had purchased Henry Ford’s “999” race car and wanted Oldfield to drive it. "The Race" between the “999” and Alexander Winton's "Bullet" captured the imaginations of not only Detroit's automotive elite, but the general population as well. When Oldfield piloted the “999” to victory over Winton's sputtering “Bullet,” the news spread like wildfire across Detroit, the Midwest, and eventually the nation.

Beyond the immediate thrill of the race itself, Barney Oldfield, the "everyman" bicycle racer from the heartland, appealed to a wide segment of American society rushing to embrace the motor car. As the Detroit News-Tribune reported after the race, "The auto replaced the horse on the track and in the carriage shed. Society sanctioned yesterday's races. And not only society, but the general public, turned out until more than five thousand persons had passed the gatekeepers.” Barney Oldfield became the face of racing for the "general public" and helped to democratize not only racing entertainment, but also automobiles in general, as vehicles moved out of the carriage house and into backyard sheds.

Barney Oldfield Driving the Ford "999" Race Car, circa 1903 / THF140144

Celebrity Status

Over the next 15 years, Barney Oldfield established multiple world speed records and gained notoriety wherever he went. He added an iconic unlit cigar to his racing persona and perfected the roguish image of a daredevil everyman. After a brief stint driving for Winton, Oldfield took the wheel of a Peerless racer, the "Green Dragon," and established himself as America's premier driver.

Barney Oldfield Behind the Wheel of the Peerless "Green Dragon" Racecar, circa 1905 / THF228859

By 1904, Oldfield held world records in the 1-, 9-, 10-, 25-, and 50-mile speed categories. In 1907, Oldfield tried his hand at stage acting when he signed on to appear in a new musical, The Vanderbilt Cup. Over a 10-week run and a brief road tour, Oldfield “raced” his old friend Tom Cooper in stationary cars as backdrops whirled behind them and stagehands blew dirt into the front rows of the theater. The following year, Oldfield entered the open road race circuit and quickly added to his legend by sparking a feud with one of the emerging stars of the day, Ralph De Palma. In March 1910, Oldfield added the title "Speed King of the World" to his resume, driving the "Blitzen Benz" to an astonishing 131.7 miles per hour on Daytona Beach in Florida.

Barney Oldfield Driving the "Blitzen Benz" Car on a Racetrack, 1910 / THF228871

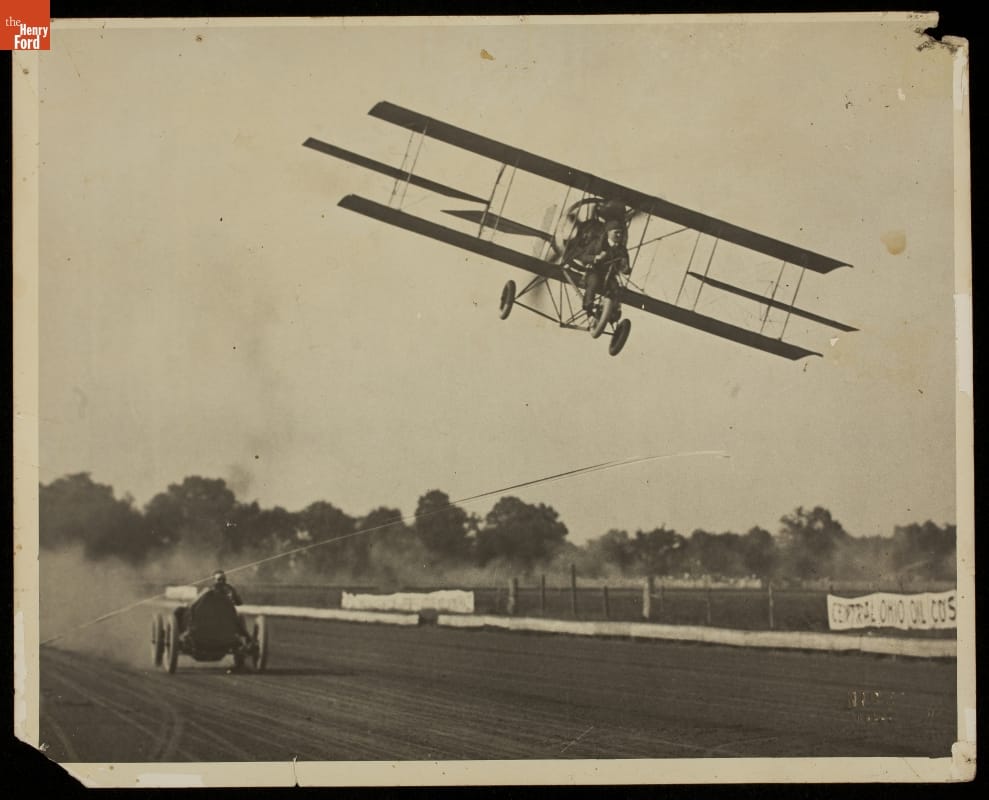

Oldfield flouted the conventions of his time, both on and off the track. He was notorious for his post-race celebrations, womanizing, and bar fights. Oldfield’s rebellious streak kept him under the scrutiny of the American Automobile Association (AAA) and, in 1910, he became the first true "outlaw" driver when he was suspended for an unsanctioned spectacle race against the heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson. Undaunted, Oldfield and his manager set up dates at county and state fairs across the country, holding three-heat matches against a traveling stable of paid drivers. Oldfield padded his reputation by adding an element of drama to these events—he would lose the first match, barely win the second, and, after theatrically tweaking and cajoling his engine, win the third match. During this time, Oldfield also became a product spokesman (perhaps most notably for Firestone tires) and began racing a fellow showman, aerial barnstormer Lincoln Beachey, in matches pitting “the Dare Devil of the Earth vs. the Demon of the Skies for the Championship of the Universe!”

Barney Oldfield and Lincoln Beachey Racing, Columbus, Ohio, 1914 / THF228829

Towards the end of his driving career, Oldfield made a final splash in the racing world with the Harry Miller-built "Golden Submarine," establishing dirt-track records from one to one hundred miles. Throughout the 1917 season, Oldfield drove the Golden Sub in a series of matches on dirt and wood tracks against his old rival Ralph De Palma, eventually winning four out of the seven races. Oldfield retired from competition racing in 1918 after winning two matches in Independence, Missouri. In typical Oldfield fashion, he ran the last race under AAA suspension for participating in an earlier unsanctioned event.

Barney Oldfield Driving "Golden Submarine" Race Car at Sheepshead Bay Board Track, Brooklyn, New York, 1917 / THF141856

Oldfield continued to keep himself at the fore of America's sports entertainment culture. In addition to ceremonial "referee" jobs at various races, he rubbed elbows with American movie, stage, and music stars and continued his rambunctious lifestyle. Between 1913 and 1945, Oldfield appeared in six movies (usually as himself) and also tried his hand as a road tester for Hudson Motor Company, salesman, bartender, club owner, and spokesman. Finally, in an attempt to raise funds to build another land-speed racer with Harry Miller, Oldfield staged a unique publicity and fundraising event. In 1933, outside Dallas, Texas, he drove an Allis-Chalmers farm tractor to a record 64.1 miles per hour.

Barney Oldfield Advertising Postcard for Plymouth Automobiles, circa 1935 / THF228879

Fittingly, Barney Oldfield's last public appearance was at the May 1946 Golden Jubilee of the Automobile Industry held in Detroit. Oldfield was fêted for his foundational role in what had become one of the largest industries in the nation. He shared the main speaker's table with automotive icons including Henry Ford, Ransom Olds, and Frank Duryea, and he accepted a “trophy of progress” for his role in automotive history. Barney Oldfield passed away in October 1946, having lived—in the words of one passionate fan—“such a life as men should know.”

For more, check out our archival collection on Barney Oldfield, browse artifacts related to him in our Digital Collections, or visit the “Showmanship” zone of the Driven to Win: Racing in America exhibition in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

This post by Peter Kalinski, former Archivist at The Henry Ford, originally ran in 2014. It has been updated by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Driven to Win: Racing in America

- Henry Ford's “Sweepstakes” Celebrates its 120th Anniversary

- 1956 Chrysler 300-B Stock Car

- 1965 Goldenrod Land Speed Race Car

Ohio, 20th century, 19th century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Michigan, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, Detroit, cars, by Saige Jedele, by Peter Kalinski, bicycles, archives

What We Wore: Sports

A new group of garments from The Henry Ford’s rich collection of clothing and accessories has made its debut in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in our What We Wore exhibit. With spring here and summer on the horizon, this time it’s a look at garments Americans wore as they delighted in the “sporting life” in their leisure time.

By the 20th century, recreational sports were an increasingly popular way to get exercise while having fun. Most Americans lived in cities rather than on farms—and lifestyles had become less physically active. Many people viewed sports as a necessity—an outlet from the pressures of modern life in an urban society.

Bicycling

The easy-to-ride safety bicycle turned cycling into a national obsession in the 1890s. At the peak in 1896, four million people cycled for exercise and pleasure. Most importantly, a bicycle meant the freedom to go where you pleased—around town or in the countryside.

Women found bicycling especially liberating—it offered far greater independence than they had previously experienced. Clothing for women became less restrictive while still offering modesty. Cycling apparel might include a tailored jacket, very wide trousers gathered above the ankles, stockings, and boots. Specially designed cycling suits with divided skirts also became popular.

Women's cycling suit, 1895-1900 / THF133355

Columbia Model 60 Women's Safety Bicycle, 1898. Gift of Mr. & Mrs. H. Benjamin Robison. / THF108117

This 1895 poster for bicycle road maps offered a pleasant route for cyclists north of New York City. / THF207603

Young men and women enjoy cycling and socializing in Waterville, Ohio about 1895. Gift of Thomas Russell. / THF201329

Baseball

Baseball has long been a popular pastime—countless teams sprang up in communities all over America after the Civil War. During the early 20th century, as cities expanded, workplace teams also increased in popularity. Companies sponsored these teams to promote fitness and encourage “team spirit” among their employees. Company teams were also good “advertising.”

Harry B. Mosley of Detroit wore this uniform when he played for a team sponsored by the Lincoln Motor Company about 1920. Of course, uniforms weren’t essential—many players enjoyed the sport while dressed in their everyday clothing.

Baseball uniform (shirt, pants, stockings, cleats, and cap), about 1920, worn by Harry B. Mosley of Detroit, Michigan. / THF186743

Baseball glove and bat, about 1920, used by Harry B. Mosley of Detroit, Michigan. / THF121995 and THF131216

The H.J. Heinz Company baseball team about 1907. Gift of H.J. Heinz Company. / THF292401

Residents of Inkster, Michigan, enjoy a game of baseball at a July 4th community celebration in 1940. Gift of Ford Motor Company. / THF147620

Golf

The game of golf boomed in the United States during the 1920s, flourishing on the outskirts of towns at hundreds of country clubs and public golf courses. By 1939, an estimated 8 million people—mostly the wealthy—played golf. It provided exercise—and for some, an opportunity to build professional or business networks.

When women golfed during the 1940s, they did not wear a specific kind of outfit. Often, women golfers would wear a skirt designed for active endeavors, paired with a blouse and pullover sweater. Catherine Roddis of Marshfield, Wisconsin, likely wore this sporty dress for golf, along with the stylish cape, donned once she had finished her game.

Dress and cape, 1940–1945, worn by Catherine Prindle Roddis, Marshfield, Wisconsin. Gift in Memory of Augusta Denton Roddis. / THF162615

Golf Clubs, about 1955. Gift of David & Barbara Shafer. / THF186328

Woman putts on a golf course near San Antonio, Texas, 1947. / THF621989

Clubhouse at the public Waukesha Golf Club on Moor Bath Links, Waukesha, Wisconsin, 1948–1956. Gift of Charles H. Brown and Patrick Pehoski. / THF622612

Swimming

Swimming had become a popular sport by the 1920s—swimmers could be found at public beaches, public swimming pools, and resorts. In the 1950s, postwar economic prosperity brought even more opportunities for swimming. Americans could enjoy a dip in the growing number of pools found at public parks, motels, and in suburban backyards. Pool parties were popular—casual entertaining was in.

For men, cabana sets with matching swim trunks and sports shirts—for “pool, patio, or beach”—were stylish. The 1950s were a conservative era. The cover-up shirt maintained a modest appearance—while bright colors and patterns let men express their individuality.

Cabana set with short-sleeved shirt and swim trunks, 1955. Gift of American Textile History Museum. / THF186127

Advertisement for Catalina’s swimsuits—including cabana sets for men, 1955. / THF623631

In the years following World War II, the number of public and private swimming pools increased dramatically. Shown here in this June 1946 Life magazine advertisement, pool parties were popular. / THF622575

Swimming pool at Holiday Inn of Daytona Beach, Florida, 1961. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Moores. / THF104037

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

home life, by Jeanine Head Miller, popular culture, bicycles, baseball, What We Wore, sports, Henry Ford Museum, fashion

Ford’s Mode:Flex Bicycle: Automakers Go Multimodal

While the concept of the e-bike has been around since the 1890s, it was not until the 1990s that battery, motor, and materials technology had advanced to the point where motorized bicycles became practical. While fully motor-driven units do exist, most e-bikes are of the “assist” variety. The rechargeable battery-powered motors on these bikes aren’t intended to replace muscle. Rather, they deliver a boost on steep hills or provide a few moments’ rest for a fatigued pedaler. The motors supplement rather than supplant human effort.

The Henry Ford acquired its first examples of electric-assist bicycle technology in 2017, with two prototype bicycles from Ford Motor Company’s Mode:Flex project. This 2015 initiative came out of the company’s efforts to position itself as a “mobility provider” for a post-car future. With the millennial generation returning to cities and, to some extent, turning away from automobiles in favor of public transit and other alternative forms of transportation, Ford charged teams of designers and engineers to create prototype bicycles specifically tailored for its automobile customers.

One of two Mode:Flex units acquired by The Henry Ford in 2017, this prototype bicycle is fully functional and capable of carrying a rider. Made of mostly steel, it weighs around 80 pounds – considerably heavier than a typical road bike’s 20-30 pounds. Bruce Williams, who led the Mode:Flex project, contended that the weight could be halved by using different materials if the bicycle ever went into production. THF172635

The Mode:Flex team – led by Bruce Williams, a Senior Creative Designer who had previously worked on the redesign of Ford’s F-150 pickup – developed a concept for a jack-of-all-trades bicycle that is easily disassembled for compact storage in any Ford vehicle. The front and rear ends are interchangeable between city, road and mountain bike configurations. (The bike’s seat post, which houses its 200-watt electric motor and rechargeable battery, remains the same in any configuration.)

The Mode:Flex connects to an app that controls the electric-assist motor; operates the LED headlight, taillight and turn signal (inspired directly by the units on the Ford F-150); and provides speedometer and trip odometer functions, navigation assistance, and real-time traffic updates. Running in “No Sweat” mode, the app monitors a user’s heart rate. When the heart rate climbs, the bicycle’s electric motor kicks in with a corresponding level of assistance, allowing novice bikers to ride to work in standard office attire (rather than Lycra or Spandex).

This non-functional mock-up of the Mode:Flex bicycle was largely created from thermoplastic materials rendered on a 3D printer. Built for promotional display purposes only, it lacks a working motor and is unable to support the weight of a rider, but it clearly illustrates the Mode:Flex bike’s foldability. THF172637

While the Mode:Flex could be used as a commuter’s sole mode of transportation, it is particularly geared toward those making multi-modal commutes. Someone might drive in from a distant suburb, park in a satellite lot outside the urban core, and then bike the “last mile” to work, shopping or entertainment. The bicycle’s app is designed to work seamlessly with an owner’s car as well. It can lock and unlock doors, monitor gas mileage or electric vehicle charging, track parking locations and perform other similar functions. The bicycle’s battery can be pulled out for remote charging or connected directly to a Ford vehicle’s electrical outlet.

The Mode:Flex bikes in The Henry Ford’s collection are concept prototypes, and Ford has no immediate plans to put them into production. Nevertheless, they represent concrete efforts by automakers to broaden their product lines and customer bases in response to evolving trends in personal transportation.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

design, 21st century, 2010s, Ford workers, technology, Ford Motor Company, by Matt Anderson, bicycles

Dressing for Bicycling Success

Women's Cycling Suit, 1890-1900. THF 13335

When a woman today prepares to go for a spin on a bicycle on a beautiful day, she might pull on jeans, shorts or even cycling shorts and a t-shirt. Women cyclists don’t think twice about this casual clothing combination—it’s comfortable and practical. Never mind that the outfit appears very much like a man’s, and that’s just fine.

Ferris “Good Sense” corset advertisement, Ladies Home Journal, June 1897. THF 133356

However, this was hardly true a century ago, when cycling became widely popular in America. While both men and women enjoyed the sport, women found it particularly liberating (no chaperone was required) and invigorating (exercise and the looser corsets worn for cycling allowed their lungs to expand). Yet female bicyclists had a real dilemma. What in the world should they wear on the “silent steed?”

This young woman shows off her bicycle and bloomer outfit in this photograph taken in Brooklyn, New York about 1895. THF 203404

In this photograph taken about 1890, Cyclist Margaret Kirkwood wears a more modest bicycling outfit. Long skirts like these rather easily became entangled in the bicycle chain. THF 203414

This fashionable and expensive linen skirt, dating from the late 1890s, is divided into two wide leg sections. THF 29559

When the bicycling craze first began about 1890, most American women preferred long skirts. After all, real ladies—modest and upstanding—wore long skirts. However, these cyclists soon found that such long skirts got tangled in chains and sent their wearers hurtling to the ground. Those who thumbed their nose at conventional dress donned divided skirts or, even more extreme, short bloomers that cinched below the knee. While such an outfit seems quite modest today, over 100 years ago most Americans believed that if a woman dressed like a man and wore such masculine “trousers,” she risked becoming man-like and unfeminine. Bystanders might jeer at female cyclists dressed in bloomers. Fathers, brothers or beaux could not fathom that the women they loved would be so daring.

Brave female cyclists ignored the criticism and insisted on wearing these bloomers and divided skirts for safety and comfort. As more and more women found the outfit to be safe as well as rather attractive, the fashion began to catch on.

By the early 1900s, American men realized that women who wore such sporty, “masculine” outfits really were just the same old gals they had known all along. In fact, bloomers became rather popular for all sorts of sports, from canoeing to gymnastics to croquet. The "New American Girl" of the early 20th century actually became associated with sporty clothing—she was beautiful, fit due to exercise, and had some university schooling. But it had taken some perseverance to push through the prejudices about appropriate clothing for the new, more active American woman.

The move toward more rational clothing, designed to be appropriate to an activity, was part of the vast change in opportunities for women during this time.

As Demorest’s Monthly Magazine had proclaimed back in October 1882, “…there is a vast amount of real work for every woman to attend to, and her dress must have some reference to it.”

This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series and was authored by Former Curator Nancy E.V. Bryk.

fashion, by Nancy E.V. Bryk, sports, bicycles, women's history

Celebrating All Things Bicycle

In 1902, the U. S. adopted Rural Free Delivery. Americans in the countryside would no longer need to go to town to get their mail -- the mail would be brought to them. Rural letter carrier, Orville J. Murphy, pictured here circa 1905, used a bike to deliver mail to outlying households around New London, Iowa. THF 201311

Since 1956, May has held the honor of being designated as National Bike Month. The holiday celebrates cyclists of all kinds across the United States and encourages everyone to get outside and hit the road on two wheels. Within the month of May one week is all about biking to work. This year National Bike to Work Week is May 16-20 and today, May 20, is Bike to Work Day.

Here at The Henry Ford, bicycles are a big part of our staff members' work day, from our employees arriving by bike to our campus in the morning to using antique bikes to travel around Greenfield Village during the day as part of their daily routines. Online, our digital collections offer hundreds of artifacts all related to bicycles, from photos of bicycle races to a shot of Walt Disney trying out a high-wheel safety bicycle inside Henry Ford Museum in the 1940s, shown above, to this 1869 miniature bicycle used by Tom Thumb.

Continue Reading

Museum Icons: Wright Cycle Shop

By the end of the 19th century technological miracles were commonplace. Railroad trains routinely traveled a-mile-a-minute. Electric lights could turn night into day. Voices traveled over wires. Pictures could be set into motion. Lighter-than-air balloons and dirigibles even offered access to the sky. But the age-old dream of flying with wings like birds still seemed like a fantasy. In a simple bicycle shop now located in Greenfield Village, two brothers from Dayton, Ohio, turned the fantasy of heavier-than-air flight into reality. Continue Reading

Ohio, 20th century, Wright Brothers, inventors, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, flying, by Bob Casey, bicycles, aviators, airplanes