Posts Tagged nature

Edsel Ford and the National Park Service: Part 2

Part 2: Mount Desert Island, Maine

Located off the coast of Maine, Mount Desert Island is one of the largest islands in the United States and home to Acadia National Park. Long known for its rocky coast, mountainous terrain, and dense wilderness, Mount Desert Island was popularized in the mid-19th century by the Hudson River School. The painters from this art movement focused on scenic landscape paintings, creating works of art that inspired many prominent citizens from the East Coast to build their summer homes on the island. By the late 19th century a resort tradition that became locally known as "rusticating" had taken root on Mount Desert. Wealthy East Coast families known as "rusticators" would spend their summers relaxing in their island mansions, taking in the scenery, and socializing with other prosperous families doing the same. In the early 20th century, the "rusticators" on Mount Desert Island also began to include affluent Detroit families as well.

Eleanor Lowthian Clay, Edsel Ford's future wife, was accustomed to affluence and spent her summers vacationing on Mount Desert Island as a child. Eleanor's wealthy uncle, Joseph Lowthian Hudson, was successful in the Detroit department store scene. As patriarch of the family, the childless J.L. Hudson cared for his other family members and allowed Eleanor's family, as well as some of his other nieces and nephews, to live with him. Hudson employed most of them in his business and groomed his four Webber nephews, Eleanor's cousins, to take over the family trade. Their sister, Louise Webber, married Roscoe B. Jackson, a business partner of J.L. Hudson. In 1909, Jackson helped formed the Hudson Motor Car Company with backing from Hudson. Jackson had found early success with the Hudson Motor Car Company and after inheriting the department store company, the Webber brothers were able to continue its success as well. The wealth and status that these families enjoyed allowed them to later choose Mount Desert Island as the location for their summer retreats and influenced Edsel to do the same.

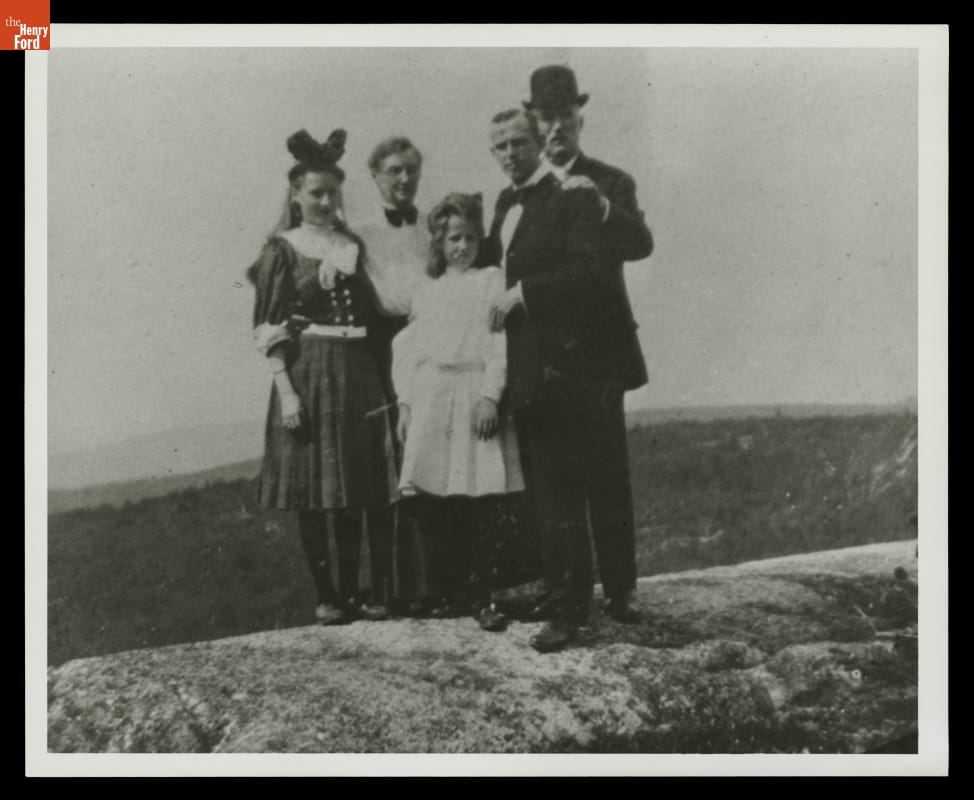

Eleanor, right, and her sister Josephine, left, vacationing in Maine with their family. THF130536

The wealth of J.L. Hudson had helped establish Eleanor's cousins and acquaint Eleanor with the son of another wealthy Detroiter in Edsel Ford. While Edsel courted Eleanor, her sister Josephine was simultaneously being courted by up-and-coming lawyer Ernest Kanzler. Edsel became close friends with Kanzler, his future brother-in-law, who eventually was hired by Henry Ford to help manage the Fordson tractor company. By the early 1920's, Edsel and Eleanor along with the Kanzlers, Webbers and Jacksons were all vacationing on Mount Desert Island. Edsel began his Mount Desert residency by renting summer homes there, occasionally inviting his parents to vacation with him. During the late summer or early fall of 1922, Edsel purchased property in the area known as Seal Harbor. Sitting 350 feet above sea level on what is known as Ox Hill, Edsel's property had a panoramic view of the surrounding sea and sky. Also within walking distance of Acadia, then Lafayette National Park, Edsel soon found that his property adjoined the property of the neighborhood national park's biggest benefactor, John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Edsel with his sons Henry II and Benson spending time at the beach in Seal Harbor. THF95355

Rockefeller Jr. first visited Mount Desert Island in 1908 and immediately became enamored with the area. He built a large estate in Seal Harbor and by the time he became neighbors with Edsel in 1922, Rockefeller Jr. had already used his wealth to donate large tracts of land to his local national park. During this time he was also in the process of building a network of carriage roads that allowed the beautiful vistas of Acadia to be accessed by the public. Preferring the quiet serenity of horse-drawn carriages over the noisy automobiles, Rockefeller Jr. worked personally with the engineers to ensure that the carriage roads captured the tranquil scenery the park had to offer. The beautiful landscapes of the area would become the topic that Rockefeller Jr. used to initiate his friendship with Edsel Ford.

Panoramic view of Seal Harbor located on Mount Desert Island, Maine. THF255236

Initially writing in December of 1922, Rockefeller Jr. didn't hide his feelings when congratulating Edsel on the purchase of his Seal Harbor property. He had visited Edsel's property at the top of Ox Hill during sunset one night and stated in his letter, "I do not know when I have seen a more magnificent and stunning view than that which met my eye on every side. You have certainly made no mistake in selecting a site for your home.” He concluded the letter by expressing how happy he and his family were at the thought of having Edsel as a permanent summer neighbor. In Edsel's gracious response to Rockefeller Jr., he mentioned that he would be using architect Duncan Candler to design his Seal Harbor home. Candler had previously designed the neighboring Rockefeller home, as well as other note-worthy properties on the island.

John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s initial letter to Edsel congratulating him on the purchase of Edsel's Seal Harbor property. This letter lead to a life-long friendship that would be fueled by the spirit of philanthropy. THF255332

Christened with the name "Skylands" due to the unbroken views of the Maine horizon line that the property provided, Edsel's summer retreat was built between 1923 and 1925. In 1924, familiar with his new summer neighbor's philanthropic efforts and swayed by his past experiences, Edsel began donating yearly to the National Parks Association, known today as the National Parks Conservation Association. Created by industrialist Stephen Mather in 1919, the organization's mission was to protect the fledgling National Park Service, of which Mather was the director. For eight years Edsel would donate $500 annually to the National Parks Association, until the Depression years of 1932 and 1933 when other business and philanthropic demands restrained his monetary donations.

By the time Edsel's summer home was done in 1925, he and Rockefeller Jr. had become good friends and philanthropic partners. They shared a love for the arts, beautiful scenery, social justice, and civic responsibility. Although twenty years his senior, Rockefeller Jr. found Edsel's situation relatable. Both men were the only sons of immensely wealthy industrialist fathers and both had inherited the responsibility of their massive family fortunes. Each looked to use those fortunes to serve humanity and steer society towards a positive future. Rockefeller Jr. cherished the trait of modesty, a trait that he saw Edsel strongly demonstrate throughout his life. For that reason, Rockefeller Jr. held Edsel, "in the highest regard and esteem," describing him as, "so modest and so simple in his own living and in his association with his fellow men." Their summers spent together at Seal Harbor would undoubtedly include conversations about where they could best direct their philanthropic efforts.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1920s, 20th century, philanthropy, nature, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Ryan Jelso

Edsel Ford and the National Park Service

On August 25, 2016, the National Park Service celebrated its 100th birthday, a celebration that encouraged us to seek connections within our collections. This blog post is the first part of four that will trace Edsel Ford’s relationship to the national parks.

The landscapes preserved by the national parks are a source of inspiration. Not only do they document the natural history of America, but they are also integral in telling the story of humanity on the continent. They remain powerful educational tools, allowing citizens to reflect on their collective history and where they want society to go in the future. Responsible for protecting these historical, cultural, and scenic landscapes, the National Park Service owes much of its existence to the forward-thinking industrialists who supported the early environmental movements in America.

The National Park Service's birth can largely be attributed to the efforts of millionaire industrialist Stephen Mather. Using his wealth and political connections, Mather secured the job of Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior and went to Washington. Once there, he worked to lobby, fundraise, and promote an agency that could manage America's national parks and monuments. Finding success, Mather became the first director of the newly-formed National Park Service in 1916. At times, he even funded the agency's administration and bought land out of his own pocket. Mather was not the only affluent American to donate his time and wealth to the National Park Service.

The Rockefellers and Mellons, two of America's wealthiest families in the early 20th century, also became champions of the national parks. Specifically during this time period, the biggest player in national park philanthropic efforts was John D. Rockefeller Jr., the only son of oil magnate John D. Rockefeller. Among his many other National Park Service donations, Rockefeller Jr. was noteworthy for purchasing the land or donating the money that helped create the national parks of Acadia, Great Smoky Mountains, and Shenandoah, including the expansion of Grand Teton and Yosemite National Parks. Rockefeller dominated this philanthropic scene and ultimately influenced the only son of another wealthy industrialist to join him in his cause.

Edsel Ford, born to Henry and Clara Ford in 1893, was not born into wealth, but the success of Ford Motor Company in the early years of the 20th century led his father to become one of the richest men in America. This set Edsel down a path to inherit the responsibility of that wealth, a position in which he would thrive. Remarking that wealth "must be put to work helping people to help themselves," Edsel understood the elite position he was in and acted with grace throughout his life. Often described as altruistic, sensible, reserved and most importantly modest, Edsel would go on to channel his family's money into countless philanthropies including medical research, scientific exploration, the creative arts and America's national parks.

While this photograph was taken during the Fords' 1909 trip to Niagara Falls, they posed for the shot in a studio and were later edited into a photo of the falls. THF98007

At a young age, Edsel experienced some of the monuments and landscapes that make up our current national park system, creating memories that surely influenced him later in life. Family trips in 1907 and 1909 took Edsel to Niagara Falls, today a National Heritage Area in the park system. For the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909, Edsel accompanied his father by train to Denver and from there they took a scenic drive to Seattle where the exposition was being held. In 1914, he joined Thomas Edison, John Burroughs and his family as they spent time camping in the Florida Everglades. He also had the opportunity to visit the Grand Canyon at least four times in his life, with his first glimpse of the gorge occurring during a family trip to Southern California in 1906.

Visiting the Grand Canyon in 1906, Edsel sits here with his mother, Clara Ford, and Clara's mother, Martha Bryant. The canyon can be faintly seen in the background. THF255176

Edsel recorded a subsequent trip to the canyon in his diary during January of 1911. He wrote that he spent time hiking, visiting the Hopi House to watch Native American dances, and photographing the canyon. Photography would become one of many artistic hobbies Edsel pursued over the course of his life. Undoubtedly the beautiful vistas of the Grand Canyon provided a spark of creativity for the burgeoning young artist. The national parks and monuments had inspired creative sparks previously, allowing Edsel to illustrate this picture of the Washington Monument in 1909. These forays into the arts helped Edsel later become the creative force that took Ford Motor Company beyond the Model T and successfully into the industry of automobile design.

Edsel recorded his second Grand Canyon trip in his diary. Interestingly, Edsel also mentions he has heard of the deaths of Arch Hoxsey and John B. Moisant, two record-breaking pilots who died while performing separate air stunts on New Year's Eve of 1910. THF255172

Before Edsel made his dreams of car design a reality, Ford Motor Company had played a role in helping to improve accessibility to the landscapes of the national parks by making the automobile, specifically the Model T, affordable to the masses. In 1915, at age 21, Edsel took off in a Model T on a cross-country road trip with six of his friends. Departing from Detroit and heading to San Francisco, the trip allowed Edsel to again witness the scenic changes in the countryside as he traveled across the continent, something he had experienced on numerous family trips before. This time though, he was in charge of the places he explored. Making various stops during his expedition, Edsel visited the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, the desert of New Mexico and the Grand Canyon for a third time.

Edsel Ford and friends hike down Bright Angel Trail while visiting the Grand Canyon during their 1915 cross-country road trip. THF243915

The Grand Canyon must have left quite the impression on Edsel because, in November of 1916, he brought his new wife Eleanor Clay there on the way to their honeymoon in Hawaii. He wrote his parents from the El Tovar Hotel saying "We are surely having a great time. Walking and breathing this great air." They had spent the previous day visiting Grandview Point, a spot that continues to provide park goers with breathtaking views of the canyon. Edsel's new wife Eleanor would play an important role in his future national park endeavors. She exposed him to the rugged shores and natural beauty of the Maine coast -- a place where Edsel would cross paths with John D. Rockefeller Jr., establishing a friendship that would last a lifetime.

Operated by the Fred Harvey Company, which owned a chain of railroad restaurants and hotels, El Tovar Hotel was opened in 1905 through a partnership with the Santa Fe Railway. THF255180

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1910s, 1900s, 20th century, travel, philanthropy, nature, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Ryan Jelso

Automobiles Enter the National Parks

The Wawona Tunnel Tree was a popular early tourist attraction at Yosemite National Park. THF130220

At the dawn of the 20th century, horseless carriages were still untested novelties. They were prone to mechanical breakdowns over long distances and likely to get mired in the muck of bad or non-existent roads. Yet, despite these challenges, the lure of taking them out to view the scenic wonders of America’s national parks was irresistible.

The first adventurous motorists showed up at Yosemite National Park in 1900 and at Yellowstone two years later. They shocked everyone and were promptly ordered to leave. For more than a decade afterward, automobiles were banned from the parks. After all, these newfangled contraptions endangered park visitors, spooked the horses who regularly pulled tourist carriages and wagons, and seemed out of keeping with the quiet solitude of the parks. It would take the creation of the National Park Service in 1916 and the vision of its first director, Stephen Mather, to wholeheartedly embrace automobiles as an asset to the parks. And perhaps no other single decision would have more impact on both the parks themselves and on Americans’ attitudes toward them.

Stagecoach loading well-to-do tourists in front of Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel at Yellowstone National Park, part of a package tour offered by the Northern Pacific Railroad. THF120284

Slowing down acceptance of automobiles in the parks was the control of the railroads, who early on realized the profits that could be made by providing exclusive access to the parks. Railroad companies not only brought tourists from distant cities and towns but also financed many of the early park hotels and operated the horse-drawn carriage tours inside the parks. The long railroad journey, hotel stays, and park tours were all geared toward wealthy tourists who could afford such extended and expensive pleasure trips.

Despite the railroad companies’ lobbying efforts and park managers’ arguments that they spoiled the experience of being in nature, automobiles entered the parks in increasing numbers. Mount Rainier National Park was the first to officially allow them in 1907. Glacier allowed automobiles in 1912, followed by Yosemite and Sequoia in 1913. Motorists to the parks still faced long lists of regulations: written authorization to enter, time restrictions on the use of their vehicles, strict attention to speed limits, and rules about pulling over for oncoming horses and honking at sharp turns.

Advertising poster promoting Metz “22” automobiles, winner of the American Automobile Association-sponsored Glidden Tour of 1913—a 1,300-mile endurance race from Minneapolis to Glacier National Park. THF111540

As automobile clubs exerted increasing pressure on local and state governments, Congress slowly began taking steps to improve park roads to make them safer for motorists. The advent of World War I—sharply curtailing travel to Europe—coupled with an aggressive “See America First” campaign by highway associations like the Lincoln Highway Association encouraged more Americans than ever to take to the open road. By 1915, so many motorists stopped at Yellowstone National Park on their way to the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco that in August of that year, automobiles were finally officially allowed entrance to that park.

The scenic Cody Road to Yellowstone National Park, which opened in 1916, offered eastern motorists a more direct route into the park than the original north entrance used by tourists arriving by the Northern Pacific Railroad and the west entrance used by those taking the Union Pacific Railroad. THF103662

In just 15 years, automobiles in the national parks had grown from a trickle to a steady stream. But the real turning point came with the creation of the National Park Service on August 25, 1916, and the vision of its first director, Stephen Mather. Mather wanted all Americans to experience the kind of healing power he himself had found in the national parks. So he aligned himself with the machine that was dramatically transforming people’s lives across the country—the automobile. Mather knew how to appeal to motorists, promising them “a warm welcome, good roads, good hotels, and public camps.” Furthermore, he innately understood that the point-to-point travel of horse-drawn carriage tours would not work for motorists, who wanted to travel on their own schedule and stop where they wanted. Scenic highways with turnouts, lookouts, and trailheads would be oriented to the understanding that, as Mather’s assistant Horace Albright maintained, “American tourist travel is of a swift tempo. People want to keep moving [and] are satisfied with brief stops here and there.”

So many early motorists arrived at the parks prepared to camp that public campgrounds were soon created to ensure safety, order, and control. THF128250

Mather’s ceaseless promotion worked. In 1918, the number of tourists coming to Yosemite by automobile outnumbered those arriving by train by a ratio of seven to one. In 1920, for the first time, the number of people visiting the national parks exceeded one million during a single year. Mather could happily declare that the American people “have turned to the national parks for health, happiness, and a saner view of life.” And the automobile, he concluded, “has been the open sesame.”

As the parks officially opened to automobiles, motorized touring cars rapidly replaced horse-drawn vehicles—in 1917 for both Yellowstone and Yosemite and in 1919 for Rocky Mountain National Park. THF209509

Numbers rose dramatically from that time on. In 1925, yearly visitation to the parks exceeded two million and in 1928, three million. With increased visitation came more willingness by Congress to support the parks. Annual appropriations went toward improvements geared to motorists, including campgrounds, picnic areas, parking lots, supply stations, and restrooms. Newly paved roads were designed to harmonize with the landscape and offered plenty of scenic turnouts and vistas. At the same time, the majority of land would remain wilderness for backcountry hikers and campers.

Roads for motorists were designed to heighten the experience of the parks’ scenic wonders, as shown by this view next to the Three Sisters Trees in Sequoia National Park. THF118881

When automobiles entered the national parks, the foundation was laid for the ways in which we experience them today. Mather believed that there was no better way to develop “a love and pride in our own country and a realization of what a wonderful place it is” than by viewing the parks from inside an automobile. Everyone did not agree, of course. Some argued that cars were a menace, a nuisance, an intrusion. Either way, the automobile was destined to become the “great democratizer” of our national parks.

This 1929 guidebook offered automobile tours not only along the rim of the Grand Canyon but also to the outlying, lesser-known Navajo and Hopi reservations. THF209662

For more on automobiles in the national parks, check out:

- “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea,” Episode Four: 1920-1933

- “National Park Service: Historic Roads in the National Park System”

Donna R. Braden is the Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. She’s looking forward to visiting two more national parks on her bucket list soon—Mount Rainier and Olympic.

cars, nature, roads and road trips, by Donna R. Braden, national parks, camping

Thomas Edison, Innovator and Beachcomber

The first object was added to the collections of The Henry Ford over a century ago, years before our official dedication. Artifacts sometimes get overlooked in this large and long-standing collection for periods of time, particularly if they are in storage and have no or minimal digital record of their existence (a problem that digitization of the collection is chipping away at). We were recently combing through our collections database for artifacts related to natural history for an upcoming project, and happened across several items described as “specimen boxes.” A little more investigation revealed they are shadowboxes containing seashells collected by Thomas Edison in Fort Myers, Florida, home to his Ft. Myers Laboratory. We’ve just digitized these shadowboxes, including this star-chambered one—see all three by visiting our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Menlo Park Glass House

- Edison at Work

- First Known Portrait of Thomas Alva Edison, circa 1851

- Edison Talking Dolls

inventors, nature, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, Thomas Edison

Yellowstone, America’s First National Park

Postcard, Old Faithful Geyser, 1934

Yellowstone National Park, the first national park established in 1872, was a uniquely American innovation. Like the Declaration of Independence, it embodied America’s democratic ideals—in this case, the groundbreaking idea that our magnificent natural wonders should be enjoyed not by a privileged few but by everyone. The inscription over Roosevelt Arch at the north entrance to the park, "For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People," symbolizes the ideals that established Yellowstone and defined the vision for all national parks to come.

Come now on a virtual tour through The Henry Ford’s collection to view the wonders of Yellowstone National Park.

Postcard, Entrance Gateway, 1903-4

Imagine it is the early 1900s, and you’ve chosen to take the four-day guided tour through the park by horse-drawn carriage. From the north entrance, you travel through towering canyons to your first stop, Mammoth Hot Springs.

Postcard, Mammoth Hot Springs Terraces, 1935

The hot springs there, heavily charged with lime, have built up tier upon tier of remarkable terraces. The springs are constantly changing, presenting what one guidebook calls “an astonishing spectacle of indescribable beauty.” After viewing the hot springs and walking among its many terraces, you spend your first night at the humble but serviceable Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel.

Postcard, Park Stage at Mammoth Hot Springs, 1904-5

The next day, anticipation builds as you head south into the area with all the geyser activity. You pass Roaring Mountain, so named for the sound of steam fumaroles that became very active and noisy there in 1902.

Postcard, The Constant and the Black Growler, Norris Geyser Basin, 1908-9

Before long, you reach the first great geyser basin: Norris Geyser Basin. At the intersection of three major earthquake fault zones, Norris is the hottest, most active geyser basin in the park. Underground water temperatures of 706 degrees Fahrenheit have been measured. Norris has it all: hot springs, geysers, fumaroles, and bubbling mud pots.

Postcard, Geysers in Eruption, Upper Geyser Basin, 1908-9

From Norris, you proceed to Lower and Middle Geyser Basins until you finally reach Upper Geyser Basin—the place you’ve heard so much about. Approximately two square miles in area, Upper Geyser Basin contains the largest concentration of geysers in the park—in fact, nearly one-quarter of all of the geysers in the world! A variety of other thermal features also exist here, including colorful hot springs and steaming fumaroles.

Postcard, Old Faithful Inn and Geyser, 1935

Upper Geyser Basin is home to Old Faithful, the most famous and celebrated geyser in the world. The 1870 Washburn Expedition camped near this geyser. They were the ones who named it Old Faithful, because they discovered it had frequent and regular eruptions. It can last from 2-5 minutes, reach a height of 90 to 184 feet, and emit 10,000 to 12,000 gallons of water at a time.

The Lobby, Old Faithful Inn, 1904-5

You stop for the night here at Old Faithful Inn, a grand hotel built in 1903. Most resort hotels at the time were intended to serve as civilized oases from the wilderness. However, Old Faithful Inn, the first true rustic-style resort, was designed by young, self-taught architect Robert Reamer to fit in with nature rather than to escape from it. The inside of the hotel continues the rustic look, with a spectacular seven-story log-framed lobby containing a massive stone fireplace.

Postcard, Paint Pots, Yellowstone Lake, 1905-6

Heading down the road, West Thumb Geyser Basin is one of the smaller geyser basins in Yellowstone. Located along the edge of Yellowstone Lake, it consists of a stone mantle riddled with hot springs. These resemble vast boiling pots of paint with a continuous bubbling-up of mud.

Postcard, Fish Pot Hot Spring, 1901

About 30 miles from Upper Geyser Basin is Yellowstone Lake—one of the coldest, largest, and highest lakes in North America. The lake includes 110 miles of shoreline and reaches depths of up to 390 feet. The bottom of the lake remains a constant 42 degrees Fahrenheit year-round.

Postcard, Lake Hotel, 1904-5

Here you rest for the night at the charming Yellowstone Lake Hotel, the oldest surviving hotel in the park, built in 1891. Robert Reamer added the colonial-style columns to this quintessential Eastern-styled hotel in 1903.

Heading back north along the park’s Grand Loop Road, Hayden Valley is filled with large, open meadows on either side of the Yellowstone River—the remains of an ancient lakebed. The valley is the year-round home to bison, elk, and grizzly bear.

Postcard in souvenir viewbook, Great Falls, 1934

As the Yellowstone River flows north from Yellowstone Lake, it leaves the Hayden Valley and takes two great plunges: first over the Upper Falls and then, a quarter mile downstream, over the Lower Falls—at which point it enters the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. In places, the canyon walls drop some 1,000 feet to the river below. You spend the night at the last of the four great Yellowstone resorts, Grand Canyon Hotel, before returning to Mammoth Hot Springs and the end of your tour.

Postcard, A Wylie Single Tent Interior, about 1910

Those who can’t afford the type of tour you’ve just taken can choose the less expensive “Wylie Way,” which involves seeing the sites from a Wylie stagecoach and lodging in a canvas tent overnight.

Postcard, Public Automobile Camp in Yellowstone Park, about 1920

It is inevitable, of course, that more and more motorists are arriving at Yellowstone every day. The use of automobiles in the park are bringing paved roads, parking areas, service stations, and improved public campgrounds. Most early motorists are used to roughing it and come prepared to camp.

Photo, Tourist with bear, about 1917

Yellowstone will set the tone for all the other national parks to come. When the National Park Service is formally established in 1916, it incorporates many of the management principles that the U.S. Army brought to Yellowstone when its soldiers first arrived to establish order there back in 1886. Old Faithful Inn will help define the style of Western resorts and park architecture for the next several decades. Finally, as some early tourist behaviors—like feeding bears, peering into geysers, and fishing in hot springs (as shown in the postcard of Fish Pot Hot Springs)—are found to be harmful to Yellowstone’s fragile ecosystems, the park will become a testing ground for exploring and defining what it means to be a national park—serving the dual mission of preserving natural wonders while, at the same time, letting the public enjoy them.

Donna R. Braden is the Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Wyoming, Yellowstone National Park, travel, roads and road trips, postcards, nature, national parks, camping, by Donna R. Braden, 20th century, 1900s

Just Added to Our Digital Collections: Plant Samples

One popular line of inquiry received by the Benson Ford Research Center involves Henry Ford’s interest in ensuring a constant and affordable supply of rubber for Ford Motor Company by establishing rubber plantations in Brazil, first at Fordlandia, and then at Belterra. Not surprisingly, our collections hold quite a bit of related material. W.L. Reeves Blakeley led the expedition to find the site that would later become Fordlandia, and, after Ford purchased the tract of 2.5 million acres, supervised the team that did the initial clearing. The W.L. Reeves Blakeley collection at The Henry Ford contains documentation of experiments, test papers, printed material, a few tools, and plant samples—the latter of which we’ve just digitized, including this sample of “maleo caetano” collected in 1931. Visit our digital collections to see all 15 plant samples, along with additional photos of Fordlandia and Belterra.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

South America, nature, Henry Ford, Fordlandia and Belterra, Ford Motor Company, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, agriculture, 20th century, 1930s, 1920s

A little over a year ago, The Henry Ford embarked on a project to digitize material related to John Burroughs (1837–1921), an American naturalist who was good friends with Henry Ford and a member of the Vagabonds (along with Henry, Thomas Edison, and Harvey Firestone). As often happens with our collections, we found more material than we were expecting. Last summer, we reported on the 250 or so items we had digitized at that point; we’re now happy to share that we’ve just wrapped up the project, with nearly 400 total items from our collections digitized. One of the last additions was this photograph of the statue of Burroughs that was installed at Henry Ford’s estate Fair Lane—a sure sign of the esteem in which the naturalist was held by the auto magnate. Browse all of these items—mainly photographs and letters, but also essays, poetry, scrapbooks, periodicals, notebooks, and postcards—in our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

nature, John Burroughs, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl

John Burroughs' Album

Artifact: John Burroughs' Album of Pressed Wildflowers, gathered during the Harriman Alaska Expedition, 1899

To tell the story of this artifact, we have to take a journey. A journey back in time and then a journey into nature. We have to visit a time in U.S. history when western land expansion had reached its near completion and U.S. citizens had only just begun to realize the natural wonders that these lands encompassed. To begin this journey, let’s explore what it means to innovate with a question:

When you think of historical innovators, who do you think of?

Henry Ford? Thomas Edison? These two historical titans of industry shaped the 20th century with technology that they endlessly, feverishly, worked on to improve. How about John Burroughs? Continue Reading

1890s, 19th century, travel, nature, John Burroughs, by Ryan Jelso

Just Added to Our Digital Collections: John Burroughs

John Burroughs (1837–1921) was an American naturalist who wrote frequently and with a literary sensibility on nature and the environment. He joined the Vagabonds, and as a result took a number of camping trips with Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and Harvey Firestone. Henry Ford also provided his friend Burroughs with multiple Ford vehicles, including a Model T touring car, to assist him in his nature studies. We’re currently digitizing selections from our collections related to Burroughs, such as this photograph of a sculpture of Burroughs created by C.S. Pietro. You can see Pietro working on what appears to be the same sculpture in another photograph. Thus far, we’ve digitized over 250 photographs, letters, writings, and postcards documenting Burroughs’ life, including his travels, famous friends, and retreats—browse them all on our collections website.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections and Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

digital collections, nature, John Burroughs, by Ellice Engdahl

Was Jack London a “Nature Faker”?

As part of The Big Read Dearborn’s focus on The Call of the Wild, I was recently asked to speak on Jack London and the Nature Faker controversy. During the first decade of the 20th century, this widely publicized literary debate shone a spotlight on the differences between science and sentiment in popular nature-writing. Although the actual controversy is long past, the issues at its root are still relevant today.

Proponents of the scientific approach to nature-writing accused the sentimentalists of creating stories that overly humanized animals, misleading readers by taking the animals’ point of view, and often concluding their stories with far-fetched happy endings. The worst offenders—the so-called “nature fakers”—went so far as to claim that their often fictional accounts were completely true-to-life.

The Nature Faker controversy had its roots in Americans’ growing appreciation for nature during the late 19th century. Natural areas suddenly seemed to offer a rejuvenating respite from the chaos, crowds, and machine-age clatter of urban life. This led to the creation of America’s national parks (Yellowstone being the first in 1872) as well as public parks and nature preserves closer to home.

During the heyday of this “cult of nature,” nature writing became immensely popular. One particular genre that emerged was the so-called “realistic” wild animal story. For the first time in popular literature, wild animals were depicted in a positive light—as compassionate creatures with which readers could sympathize.

Jack London was one of many authors at this time who wrote in this genre. In his book The Call of the Wild (1903), London revealed the thoughts and emotions of his dog-hero, Buck, with such sophistication and literary skill that it was easy for readers to become convinced that London was truly revealing Buck’s innermost self.

Enter naturalist John Burroughs—in his 60’s by this time—who was known far and wide for his many essays. These received praise in both literary and scientific circles, as Burroughs believed in both reporting the objective facts of nature and describing one’s subjective feelings. But he was adamant that these should remain clear and separate.

Burroughs was incensed by the glowing reviews of the new wild animal stories. He felt that some them blurred the line between fact and fiction. Furthermore, he believed that the authors of these stories were deliberately misleading the public for their own financial gain.

In 1903, he submitted a scathing essay to Atlantic Monthly, entitled “Real and Sham Natural History.” In this essay, Burroughs denounced the perception that many of these stories were true. He claimed that the “sham nature writers” deliberately attempted to “induce the reader to cross into the land of make believe.”

After Burroughs’ essay appeared, incendiary responses both supporting and attacking the “sham nature-writers” frequently appeared in the press. This went on for a good four years—until President Theodore Roosevelt publicly joined the debate.

Roosevelt had long been a nature-enthusiast known for his grand hunting expeditions. In fact, the Teddy Bear, introduced in 1903, originated from stories about his reputation as a hunter.

After years of corresponding with John Burroughs, he went public with an interview that appeared in Everybody’s Magazine, entitled “Roosevelt and the Nature Fakirs.” In this article, he noted many of the same issues that Burroughs had raised, then singled out several authors by name—including, for the first time, Jack London. This also marked the first time that the term “nature fakir” (soon to be changed to “nature faker”) was used.

London was justifiably hurt by President Roosevelt’s accusations and tried to defend himself in an essay published in Collier’s Weekly:

I have been guilty of writing two books about dogs. The writing of these two stories, on my part, was in truth a protest against the “humanizing” of animals, of which it seemed to me several “animal writers” had been profoundly guilty….

I endeavored to make my stories in line with the facts of evolution; I hewed them to the mark set by scientific research and awoke, one day, to find myself bundled neck and crop into the camp of the nature-fakers.

In the end, however, how could anyone truly argue with the President of the United States? The Nature Faker controversy soon died down. After that, authors and publishers were more likely to check their facts while the public became more skeptical of what they were reading. But few of the people involved in the actual controversy changed their views.

While Jack London unfortunately died at the young age of 40, John Burroughs lived a long productive life into his 80’s. As his legendary status increased, he often entertained luminaries at his home in the Catskills. Among these luminaries was Henry Ford, who admired his writings and invited him to join his group of Vagabonds (consisting of himself, Thomas Edison, and Harvey Firestone) for several lavish camping trips.

What do you think? Were John Burroughs and President Roosevelt onto something? Was Jack London really a “nature faker”? Or was he just a good storyteller?

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

presidents, John Burroughs, by Donna R. Braden, nature, books