Posts Tagged roads and road trips

The Romance of Covered Bridges

Lloyd Van Meter photographing Nancy Lawrence near Ackley Covered Bridge in Greenfield Village, June 1958. / THF625878

What comes to mind when you picture a covered bridge? Many people imagine an idyllic scene, perhaps based on a favorite artist’s depiction or reference from literature or film. Few have difficulty visualizing a “classic” covered bridge. These structures have an appeal that has outlasted their utility, though common understanding of them is often misinformed.

Covered bridges were built across the United States throughout the 19th and into the early 20th centuries for the sole purpose of protecting the structure within. Building a bridge was a major undertaking that required careful planning and a substantial community investment of time, labor, and materials. In the days before weatherproofed lumber, walls and a roof could extend a valuable bridge’s lifespan by shielding the truss system and keeping structural timbers dry.

In spite of their pure functionality, people came up with their own interpretations for covered bridges. Common beliefs emerged that a roof strengthened a bridge or protected the floor planks from rain and snow. Many came to think that covered bridges were built to shelter the people and animals traversing them, and some claimed the barn-like appearance calmed uneasy animals crossing over rushing water. Storytellers showcased covered bridges in tales ranging from the romantic to the mythical. These misunderstandings and cultural references encouraged the association of covered bridges with a “simpler time.”

Thanks to their age, perceived rarity, and admittedly often picturesque settings, covered bridges have increasingly attracted Americans’ attention. In 2005, the Federal Highway Administration reported there were fewer than 900 covered bridges remaining in the United States. (The estimated peak was about 14,000; you can view the full report here.) Many of these were, and are, well-loved and well-protected, with historic preservation groups and covered bridge societies dedicated to their upkeep. America’s surviving covered bridges have become regional treasures and tourist destinations. State and local organizations have featured them in marketing campaigns, erected signage, and developed tours to facilitate sightseeing.

Some states created special maps for covered bridge tourists. Above, “Covered Bridges in Maine,” 1956, and “Covered Bridges in New Hampshire,” 1969. / THF628822, THF628825

Postcards helped people share or remember covered bridges, whether close to home or part of a special trip. These examples depict covered bridges in Maryland, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Pennsylvania. / THF625864, THF625866, THF625870, and THF625868

Nostalgic imagery of both real and imagined covered bridges continues to adorn everything from souvenirs to home décor. These examples from the collections of The Henry Ford help illustrate the enduring romance of covered bridges. You can browse more and see photographs documenting Greenfield Village’s Ackley Covered Bridge here.

Christmas card, 1949; "Vermont" snow globe, 1960-1975; and Hallmark "Grandparents" Christmas ornament, 1982. / THF628816, THF189039, and THF179213

Explore a similar fascination with practical structures—those that generate water power—through this expert set.

Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Ackley Covered Bridge in Greenfield Village. / THF1914

Guests visiting Greenfield Village in the spring of 2001 encountered a newly transformed Ackley Covered Bridge. The landmark structure—one of the most recognizable, most photographed sites on the grounds—had been completely repaired and restored. While the bridge’s resurrection may have seemed to have happened miraculously, it was—as with all our restoration efforts—the result of meticulous planning and careful completion of a well-defined project.

Originally constructed in 1832 in southwestern Pennsylvania, the single-span, 80-foot bridge’s design dates back to 16th-century Italy and was adapted in a uniquely American way in the early 1800s. It is referred to as a multiple kingpost truss: a series of upright wooden posts, with all braces inclined from the abutments and leaning towards the center of the “kingpost.”

Ackley Covered Bridge was originally a community project, built by more than 100 men on land owned and with materials donated by brothers Daniel and Joshua Ackley. By the mid-1930s, it had fallen into serious disrepair, and when a modern bridge was constructed to replace it, the granddaughter of one of the builders purchased the hundred-year-old Ackley structure for about $25 and donated it to Henry Ford.

Views of Ackley Covered Bride on Wheeling Creek near West Finley, Pennsylvania, 1937. Browse more photos of the bridge on its original site in our Digital Collections. / THF235241, THF132888, THF235221

Simple and classic in its construction, the bridge was dismantled at its original location in late 1937 and shipped by rail to Dearborn. Modifications were made to ensure its longevity, and a number of basic preservation chores were undertaken in the six months between its arrival and the completion of reconstruction in July 1938. (You can view photos of the bridge’s reconstruction and dedication in our Digital Collections.)

Ackley Covered Bridge after reconstruction in Greenfield Village, June 30, 1938. / THF625902

“Even in the 1930s, the Ackley Covered Bridge was clearly an architectural treasure, and Ford and his designers knew its importance and placed it at the heart of the Village,” said Lauren B. Sickels-Taves, architectural consultant for the restoration project. The bridge was back in its prime, spanning a pond designed specifically for it.

Taking photographs near Ackley Covered Bridge in Greenfield Village, 1958. / THF625878

“Unfortunately, the pond was standing rather than flowing water, and the water level had the ability to rise and fall,” she said. “The chords and four end trusses of the bridge (basically, its feet) were exposed to extreme wet/dry cycles, and rot was imminent. By 1974 the bridge was structurally unsound, and dangerous.”

While repairs were undertaken then, nothing was done to regulate the level of the pond, and by the spring of 1999, one truss end was found to be rotting. Closer examination revealed that the bridge was once again structurally unsafe.

Alec Jerome, then part of the facilities management team he now leads at The Henry Ford, was designated as project leader to bring Ackley Covered Bridge back to stability. David Fischetti, a historical structural engineer from North Carolina with a background in covered bridges, was brought in to develop a plan to properly restore the bridge, and Arnold Graton of New Hampshire, one of the country’s leading covered bridge timberwrights, was selected to lead the stabilization and restoration work.

“First,” said Jerome, “the pond had to be drained to expose areas that needed repair. The conditions that we discovered led to some serious revisions in our original project plan—every beam touching the ground was rotting and needed to be replaced.”

Views showing restoration of Ackley Covered Bridge in Greenfield Village, September and October 2000. / THF628587, THF628611, THF628525

The dry rot portion of the original trusses was removed and new support beams were spliced on. The refurbished trusses were then seated on stainless steel plates to prevent moisture from wicking up into the wood. Also, a turnbuckle system was implemented in the upper beams of the bridge, which had become separated over time, to ensure stability. Many of the connectors holding the bridge beams together were replaced, and ultimately a bolster was laid to eliminate any conditions that would promote rot in the floor beams and allow that devastating wet/dry cycle of rot to begin again.

“Our main concerns were the extensive amount of rot over and above the original expectations, the short time period between Village programs in which we had to complete the work, and weather conditions getting in our way,” Jerome said. Work began the day after Old Car Festival in September, and lasted through the day before the start of the evening program, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, the second week of October. “The project could not have been completed without the assistance of the Museum’s carpentry department and our welder,” Jerome said. “These people assisted with every facet of this restoration.” See more photographs from the restoration project in our Digital Collections.

According to conservator Sickels-Taves, research determined that Ackley Covered Bridge was the oldest multiple kingpost truss bridge and the sixth-oldest covered bridge in the nation. While the cost of its restoration after a century and a half of decline was substantial, its preservation for the future was priceless—without such key commitments of resources, important structures like Ackley Covered Bridge would be lost forever. “The bridge is unquestionably important,” Sickels-Taves said. “We should be proud, and not hesitate to brag that we are the steward of one of the earliest forms of original American architecture.”

A version of this post originally ran in the Spring/Summer 2001 issue of The Henry Ford’s former publication, Living History. It was edited for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

roads and road trips, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, collections care, by Saige Jedele, Ackley Covered Bridge, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Ackley Covered Bridge in Pennsylvania

Few visitors to Greenfield Village cross Ackley Covered Bridge realizing the significance of the structure surrounding them. It is one of the oldest surviving covered bridges in the country, and considerable thought went into its overall design. Covered bridges have long been stereotyped as quaint, but the reason behind their construction was never charm or shelter for travelers. The sole function of the “cover” was to protect the bridge’s truss system by keeping its structural timbers dry.

Built in 1832, Ackley Covered Bridge represents an early form of American vernacular architecture and is the oldest “multiple kingpost” truss bridge in the country. This structural design consists of a series of upright wooden posts with braces inclined from the abutments at either end of the bridge and leaning towards the center post, or “kingpost.” It is also a prime example of period workmanship and bridge construction undertaken with pride as a community enterprise.

This map of Washington County, Pennsylvania, shows the original site of Ackley Covered Bridge (bottom left). / THF625813

Ackley Covered Bridge was constructed across Wheeling Creek on the Greene-Washington County line near West Finley, Pennsylvania. The single-span, 80-foot structure was built to accommodate traffic caused by an influx of settlers. Daniel and Joshua Ackley, who had moved with their mother to Greene County in 1814, donated the land on which the bridge was originally constructed, as well as the building materials. More than 100 men from the local community, including contractor Daniel Clouse, were involved in the bridge’s construction. Like most early bridge builders in America, they were little known outside their community. But their techniques were sound, and their work stood the test of time.

Initial community discussions about the bridge included a proposal to use hickory trees, which were abundant in the region, in honor of President Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson. Instead, they settled on white oak, which was more durable and less likely to warp. The timber came from Ackley property a half mile south of the building site. It was cut at a local sawmill located a mile south of the bridge. Hewing to the shapes and size desired was done by hand on site. Stone for the abutments was secured from a quarry close by.

Ackley Covered Bridge replaced an earlier swinging grapevine bridge, and it may soon have been replaced itself if settlement and construction in the region had continued. Instead, the area remained largely undeveloped for several decades. This, along with three roof replacements (in 1860, 1890, and 1920), helped ensure the bridge’s survival.

Ackley Covered Bridge at its original site before relocation to Greenfield Village, 1937. / THF235241

Plans to replace the more than 100-year-old structure with a new concrete bridge in 1937 spurred appeals from the local community to Henry Ford, asking him to relocate Ackley Covered Bridge to Greenfield Village. Ford sent representatives to inspect, measure, and photograph the bridge before accepting it as a donation from Joshua Ackley’s granddaughter, Elizabeth Evans. She had purchased the well-worn structure from the state of Pennsylvania for $25, a figure based on the value of its timber. Evans had a family connection to one of Ford’s heroes, William Holmes McGuffey. McGuffey’s birthplace, already in Greenfield Village, had stood a mere seven miles from the original site of Ackley Covered Bridge—an association that likely factored in Ford’s decision to rescue the structure.

Dismantling of Ackley Covered Bridge began in December 1937. Its timbers were shipped by rail to Dearborn, Michigan, and the bridge was constructed over a specially designed pond in Greenfield Village just in time for its formal dedication in July 1938.

Ackley Covered Bridge after construction in Greenfield Village, 1938. / THF625902

This post was adapted by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford, from a historic structure report written in July 1999 by architectural consultant Lauren B. Sickels-Taves, Ph.D.

Michigan, Dearborn, Pennsylvania, 1830s, 19th century, travel, roads and road trips, making, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Saige Jedele, by Lauren B. Sickels-Taves, Ackley Covered Bridge

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956

"The Road Ahead, the Exciting Story of the Nation's 50 Billion Dollar Road Program," 1956 / THF103981

"The Road Ahead, the Exciting Story of the Nation's 50 Billion Dollar Road Program," 1956 / THF103981

Last June marked the 65th anniversary of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which initiated a program to plan and fund an interstate system. In recognition of this milestone, Reference Archivist Lauren Brady selected some items from our collections that show how the highway system changed the American way of life. She shared these artifacts as part of our monthly History Outside the Box series on Instagram, which showcases items from our archives.

If you missed her presentation or would like to see it again, you can check it out below.

Continue Reading

20th century, 1950s, roads and road trips, History Outside the Box, by Lauren Brady, by Ellice Engdahl, archives

Collecting Mobility: Insights from Michigan Department of Transportation

Our new limited-engagement exhibit, Collecting Mobility: New Objects, New Stories, opening to the public October 23, 2021, takes you behind the scenes at The Henry Ford to show you how we continue to grow our vast collection of more than 26 million artifacts. One key question the exhibit asks is why we collect the items we collect. To get more insight on the artifacts on exhibit and future trends that may impact our collecting, we reached out to several of our partners. In this post from that series, our friends at the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) and the Michigan Economic Development Corporation (MEDC) tackle questions about the infrastructure of mobility.

Our cars are increasingly "connected," whether for navigation, communication, or entertainment. What challenges does this pose for our current infrastructure, and what improvements are most urgently needed to keep pace with technology?

MDOT:

First, the balance between data-sharing and privacy. The Michigan Department of Transportation leads all our efforts with safety first. Our agency looks to find opportunities to solve modern traffic challenges as cars become increasingly connected with technology that meets the need for navigation, communication, and/or entertainment.

Due to today’s connectivity, MDOT has the means to share data and asset information relevant to roadway users—for example, wrong-way driving alerts and information directly connected to infrastructure, vehicles, and other devices. But as more consumers purchase connected vehicles, there are increased opportunities for exploitation by hackers using cellular networks and/or wi-fi. Therefore, software vulnerabilities, privacy, and other cybersecurity concerns must be addressed as quickly as the technology progresses.

Early standalone consumer GPS units, like this 1998 Garmin “Personal Navigator” system, had limited or no integration with the rest of a car. As vehicles become increasingly connected, potential safety and security concerns increase too. / THF150113

Second, leaving room for solutions, opportunities, and collaboration. It is imperative to remain technology-agnostic and interoperability is critical. Today’s vehicles meet many needs and should be able to work with many devices and operating systems.

A recent decision by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to reallocate a portion of the radio spectrum from public safety to commercial use has been the most significant impact to date. This introduces the potential of not having enough spectrum to operate the technology to improve safety and mobility. Continued collaboration with other governmental agencies, private companies, and academia leads to a safer, better user experience for motorists.

Challenges in allocating limited radio spectrum frequencies aren’t new. In 1977, at the height of the CB radio craze, the FCC yielded to popular demand by expanding the number of citizens band channels from 23 to 40. / THF106547

MEDC:

The increase in connectivity between vehicles challenges our current infrastructure because infrastructure upgrades are not able to happen as quickly as the vehicle technology is advancing. First, we need to make sure our current infrastructure is maintained and suitable for the vehicles we do have on the roads. The next improvements would be continuing to implement vehicle-to-everything (V2X) technology on our roadways, and to explore connected infrastructure projects, such as a public-private partnership to establish and manage a connected roadway corridor.

Navigation apps like Waze leverage user data and intelligent transportation systems (ITS) to provide real-time updates, helping drivers avoid construction and other traffic congestion. Does MDOT have its own advanced technologies and services to enhance these platforms and keep Michigan drivers safe and on the move?

MDOT:

MDOT utilizes a variety of methods to reach out to our citizens to provide traveler information. Drivers can access our Mi-Drive link for detailed information regarding construction projects, etc. Our traffic operations centers post information for incidents and rerouting on our dynamic message signs located on our freeway system.

This 2018 Waze beacon, on display in Collecting Mobility through January 22, 2022, eliminated dead spots in GPS navigation by placing battery-powered beacons in tunnels where GPS satellite signals couldn't reach. / THF188371

As vehicles and roadways transition to the future state of connectivity, there will continue to be many vehicles on the road that are not equipped with these technologies. How will the new systems accommodate older or non-connected vehicles?

MDOT:

MDOT works with industry partners on that transition, and as new technologies are implemented, we are always considering the users and amount of saturation for vehicles to take advantage of them. For example, MDOT provides information on our dynamic message boards, and we can also provide that information into connected vehicles. It would be difficult to remove those dynamic message signs currently, as the number of connected vehicles on the road today is not high enough. The technologies will become more prevalent as drivers get new vehicles and aftermarket technologies are implemented on older vehicles. Systems already exist on vehicles coming off the assembly line that are improving safety, such as blind spot and forward collision warnings, and adaptive cruise control.

The coming transitional period, in which connected cars share roads with non-connected vehicles, will mirror the mobility transition of the early 20th century, when horse-drawn vehicles coexisted with automobiles. / THF200129

MEDC:

It’s important to note that connected roadways will not cancel out the use of non-connected vehicles—there will be a transitional period where a lot of non-connected vehicles will use aftermarket Internet of Things (IoT) solutions that allow them to take advantage of the connected roadways. The non-connected vehicles may not be able to take advantage of all the benefits of the connected roadways, like communication and navigation, but there will be solutions to upgrade their vehicles to accommodate them.

We've long depended on gasoline taxes to finance road construction and maintenance. But as the percentage of electric vehicles (EVs) grows, gas tax revenues decrease. Should we be looking at new funding methods? What alternatives should we consider?

MDOT:

This will be an important public policy discussion going forward. In Michigan, road funding legislation signed by then-Governor Rick Snyder in 2015 included increased registration fees for EVs. Roads in Michigan are primarily funded through registration fees and fuel taxes. More creative mechanisms will be necessary to continue to maintain our roads and bridges. Legislation in Michigan tasked MDOT with conducting a statewide tolling study, which is ongoing. New public-private partnerships will be vital to creating and maintaining charging infrastructure.

Gas taxes won’t pay for roads in an electric-vehicle world. This modern problem could be solved in part with an ancient solution: toll roads. Learn more about highway funding challenges in our “Funding the Interstate Highway System” expert set. / THF2033

States could look to local governments and other state agencies to encourage charging infrastructure inclusion in building codes and utility company build-out plans. There is also uncertainty at the moment around what federal programs might be created as a result of the draft infrastructure plan being debated by Congress.

MEDC:

Yes, absolutely. With more electric vehicles coming to market, there is an opportunity for more creative ways to finance roads while ensuring no more of a burden on electric vehicle drivers than on gasoline vehicle drivers. Some alternatives include a VMT (vehicle miles traveled)–based fee that electric vehicle owners could opt into. The fee would be based on a combination of the vehicle’s metrics and miles driven, to accurately reflect road usage and the gas taxes that gasoline vehicle owners pay. This is also a policy recommendation in the Michigan Council on Future Mobility and Electrification’s annual report, which will be published in October 2021.

In the 1950s, there were experiments with guidewire technology that enabled a car to steer itself by following a wire embedded in the pavement. Today we're experimenting with roads that can charge electric vehicles as they travel. Is it time to rethink the road itself—to connect it directly with our cars?

MDOT:

Thankfully, infrastructure continues to become “smarter” due to intelligent transportation systems, smart signals, and more—for example, the simplification of the driving environment for connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs). In 2020, MDOT established a policy to increase the width of lane lines on freeways from four to six inches to support increasing use of lane departure warning and lane keeping technologies.

Our roadways evolve with our technologies. This 1956 brochure promotes the proposed Interstate Highway System—which was then a brand-new idea, not yet implemented. / THF103981

Similarly, the roadway can be evolved to optimize travel in EVs. The development of a wireless dynamic charging roadway in Michigan is a step forward in addressing range anxiety and will accelerate better understanding of infrastructure needs moving forward. This inductive vehicle charging pilot will deploy an electrified roadway system that allows electric buses, shuttles, and vehicles to charge while driving. The pilot will help to accelerate the deployment of electric vehicle infrastructure in Michigan and will create new opportunities for businesses and high-tech jobs.

Some of Michigan’s “smart infrastructure.” / Infographic courtesy MDOT

MEDC:

It is time to rethink the road itself—as new advancements in mobility and electrification roll out for vehicles, it’s only natural to rethink the infrastructure these vehicles operate on. As computers got smaller and more compact over time, so did their chargers. It’s a similar thing with vehicles and their infrastructure. As vehicles get smarter and more connected, the infrastructure will have to follow suit.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford, Michele Mueller is Sr. Project Manager - Connected and Automated Vehicles at Michigan Department of Transportation, and Kate Partington is Program Specialist - Office of Future Mobility and Electrification at Michigan Economic Development Corporation (MEDC). The Michigan Department of Transportation is responsible for Michigan's 9,669-mile state highway system, and also administers other state and federal transportation programs for aviation, intercity passenger services, rail freight, local public transit services, the Transportation Economic Development Fund, and others. The Michigan Office of Future Mobility and Electrification within the MEDC was created in February 2020 to bring focus and unity in purpose to state government’s efforts to foster electrification, with a vision to create a stronger state economy through safer, more equitable, and environmentally conscious transportation for all Michigan residents. See Collecting Mobility for yourself in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation from October 23, 2021, through January 2, 2022.

autonomous technology, alternative fuel vehicles, Michigan, technology, roads and road trips, cars, by Kate Partington, by Michele Mueller, by Matt Anderson

The Henry Ford has two tollbooths—both from New England, but from different eras and circumstances. The Rocks Village toll house was built in the early 19th century, when horse-drawn carriages and wagons filled America’s roads. The Merritt Parkway tollbooth dates from the mid-20th century, when Americans traveled these roads in automobile, often for recreation.

Why are these buildings, both made to collect a toll for the use of a road or bridge, so completely different in their appearance and history? Their stories tell us much about our changing attitudes toward roads and road construction, and of our expanding expectations of governmental responsibility for transportation networks.

Rocks Village Toll House, 1828, near the Ackley Covered Bridge in Greenfield Village. / THF2033

The Rocks Village Toll House

Today, the Rocks Village toll house sits adjacent to the Ackley Covered Bridge in Greenfield Village. The simple, functional building formerly served a much larger covered bridge and drawbridge that spanned the Merrimack River, connecting the towns of Haverhill and West Newbury, Massachusetts. The bridge and toll house were built in 1828 to replace an earlier bridge that had been destroyed by a flood. Their construction was not the responsibility of the towns where they were located, nor the state or federal government, but of the Proprietors of the Merrimack Bridge, a group of Haverhill and West Newbury investors who had built the first Merrimack Bridge in 1795. The building housed a toll keeper, who was responsible for collecting the tolls and for opening the drawbridge when necessary. In his considerable spare time, the toll keeper also worked as a cobbler, making shoes. Tolls were collected until 1868, and the toll house remained in use for the drawbridge until 1912.

This worn image of the Merrimack Bridge from about 1910 shows the Rocks Village toll house (marked #2) along the approach to the right of the covered bridge. / THF125139

When the first Merrimack Bridge was built at Rocks Village in 1795, there was a need for good routes from the farmlands of northern Massachusetts and New Hampshire to the growing urban markets of Boston. Neither the new federal or state governments had the resources to build and maintain many roads. As a result, privately-owned turnpike and bridge companies, like the Proprietors of the Merrimack Bridge, were encouraged to fill that need with toll roads and bridges, which proliferated around the new nation.

The era of turnpikes and toll bridges was beginning to draw to a close when the second Merrimack Bridge was built in 1828. By mid-century, canals and then railroads had replaced roads as the primary means of traveling across distances, so roads and bridges were generally used more for local travel. This change can be seen in the decline in weekly receipts at the Rocks Village toll house, from a high of $58.00 in 1857, to $29.00 in 1868, when the Merrimack Bridge became a free bridge. At that time, Essex County assumed authority over the bridge, and the towns it served—Haverhill, West Newbury, and Amesbury—shared the costs of its upkeep. With only local support, upkeep was sporadic at best, and by 1912, most of the bridge had to be replaced.

The Rocks Village toll house had witnessed the decline of the American road during the mid-19th century. It would not be until the advent of the bicycle in the late 19th century, followed by the automobile in the early 20th century, that this decline would be reversed.

The Merritt Parkway Tollbooth

Merritt Parkway Tollbooth, circa 1950, in the Driving America exhibition in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF79064

The rustic design of the Merritt Parkway tollbooth celebrated the pleasures of driving to experience the outdoors, part of a larger effort to promote tourism in Connecticut. It was built in Greenwich around 1950 as an expansion to the existing toll plaza. The Merritt Parkway runs 37 ½ miles from the New York state line at Greenwich to Milford, Connecticut. It was built in 1938 by the State of Connecticut to relieve the congestion on US 1 (the Boston Post Road), the main route from New York to Boston. Tolls were collected on the Merritt Parkway until 1988.

The Henry Ford’s Merritt Parkway tollbooth is one of the two at the outer edges of the original rustic toll plaza, built in 1940. / THF126470

The Merritt Parkway is, in many ways, a celebration of the revival of the American road. And, as a state response to local problems, it reflects the change in the responsibility for roads from the local to the regional and state levels. Heavy New York-to-Boston through-traffic, in addition to commuter traffic in and out of New York City, had turned US 1 into a permanent traffic jam. This created tremendous problems for the local communities along that route. However, the citizens of those communities were not inclined to bear the financial burden of road improvement, especially since would mostly serve people from out-of-state. The debate about how to solve this problem lasted from the early 1920s into the 1930s.

The eventual solution, the Merritt Parkway, contained the main elements of the modern highway. First, it bypassed population centers, pulling traffic away from busy downtown areas. Second, since it passed through the rapidly gentrifying farm- and woodlands of southwest Connecticut, the design of the parkway—the graceful layout of the road itself through rolling hills, as well as the bridges, service buildings, and tollbooths—emphasized the rustic beauty of the region. The beautiful design helped to promote Connecticut as a tourist destination for out-of-state visitors. Third, it was built during the economic depression of the 1930s, so its construction was touted as a job-creating project. Finally, its construction and maintenance were funded by the state and paid for out of the general treasury. Added after a couple of years, the tollbooths raised money for an extension of the highway to Hartford, Connecticut—the Wilbur Cross Parkway.

With the Merritt Parkway and similar roads, good public roads had returned and—for better or worse—had come to be viewed as an entitlement, subsidized through the public treasury rather than private investment.

Jim McCabe is former curator and collections manager at The Henry Ford. This article was adapted by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, from the July 2007 entry in our previous “Pic of the Month” online series.

Additional Readings:

- Driving America

- Noyes Piano Box Buggy, about 1910: A Ride of Your Own

- 1908 Stevens-Duryea Model U Limousine: What Should a Car Look Like?

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

roads and road trips, cars, by Jim McCabe, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Driving America, Henry Ford Museum

Passengers rush to board the Overland Limited, which ran between Los Angeles and Chicago over the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railway, ca. 1905. / THF207763

Between 1865 and 1920, America’s railroad network increased sevenfold, from 35,085 miles to an all-time high of 254,037 miles in 1916. The rapid expansion of the national rail network corresponded with major technological improvements—including double tracking, improved roadbeds, heavier and faster locomotives, and the elimination of sharp curves—which allowed trains to operate at higher speeds. Travel times were steadily cut year by year. To emphasize time savings, railroad companies began to give their faster lines special names like “flyer,” “express,” and “limited.”

This 1913 timetable for the St. Louis-Colorado Limited line of the Wabash-Union Pacific Railroad boasted that it was the shortest line with the fastest time between destinations. / THF291441

However, increased speed came with disadvantages. High speeds resulted in an increasing number of gruesome railroad accidents caused by both discrepancies in local times and mix-ups between different railroad companies’ timetables.

A catastrophic collision occurred between two passenger trains on the Providence & Worcester Railroad when they failed to meet at a passing siding as scheduled, 1853. / THF622050

Facing governmental intervention to address the problem, the railroads took it upon themselves to enact a single standardized time across the country by dividing the nation into five roughly even time zones. Some people at first rebelled against this arbitrary imposition, especially when the newly drawn time zone designations did not align with local practices. But most people found it increasingly convenient to set their clocks by this new “standard time.”

Residents of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, would have synchronized the time on their personal clocks and watches to the railroad depot clock seen in this ca. 1916 postcard. / THF124830

Another disadvantage, some people complained, was that the increasing speed of railroad travel was unhealthy. Many believed that the rapid pace of life contributed to new forms of stress and anxiety and that the railroad was a key cause of these problems.

Railroad passengers ascending the staircase after arriving in Chicago, via the Illinois Central Railroad, ca. 1907 / THF105820

By 1920, railroad passenger travel was at the highest level it would ever attain. But, with the exception of the unique conditions during World War II, the railroad would never again be the dominant form of personal transportation in America. Within a few decades, the American public would embrace automobiles with the passion they had once given over to the railroads. How did this transfer of allegiance from railroad to automobile occur so effortlessly and completely during the early 20th century, and how does it relate to Americans’ changing concepts of time?

A group of motorists travelling from Davenport, Iowa, to New York, ca. 1905 / THF104740

At first, many railroad managers did not take automobiles seriously—and for good reason. When they were first introduced in the 1890s, automobiles had no practical purpose. They were considered amusing and entertaining playthings for wealthy hobbyists and adventurers.

1909 advertisement for the Pierce-Arrow Motor Car, an automobile geared to wealthy motorists who could afford to have a chauffeur handle the driving for them. / THF88377

Most railroad managers were complacent, agreeing with one claim that “the fad of automobile riding will gradually wear off and the time will soon be here when a very large part of the people will cease to think of automobile rides.” But, as it turned out, the public passion for automobile riding did not wear off. Increasingly, Americans from all walks of life embraced automobiles and their advantages over railroads. By 1910, more than 468,000 motor vehicles had been registered in the United States.

Automobiles would have not achieved the level of popularity that they did without major advancements in the roads on which they traveled. As far back as the 1890s, bicyclists and early motorists had tried to alert the public to, and lobby the government for, better roads—roads that the railroads had ironically either replaced or rendered unnecessary.

The Bulletin and Good Road, the official organ of the League of American Wheelmen, kept bicyclists up to date on advancements relating to the “Good Roads” movement. / THF207011

One reason that people embraced automobiles was because they revived the promise of individual freedom. Compared with railroad travel, motorists were unhampered, free to follow their own path. Elon Jessup, author of several motor camping books, wrote, “Time and space are at your beck and call, your freedom is complete.”

Motorists enjoying life on the road in the Missouri Ozarks, 1923. / THF105550

According to a 1910 American Motorist article, no longer were people tied to intercity train schedules, “rushed meals,” and “rude awakenings.” The motorist was “his own station master, engineer, and porter.” Riding in his own “highway Pullman,” he had “no one’s time to make except his own.” Automobile advocate Henry B. Joy wrote in a 1917 Outlook article that motoring promised “freedom from the shackles of the railway timetable.” Automobiles were also considered a particular advantage for women, who were increasingly venturing out into public spaces to shop, work, socialize, and take pleasure trips.

Four women in a Haynes automobile, travelling from Chicago to New York, ca. 1905. / THF107595

In addition to restoring people’s personal control over their own time, automobiles succeeded in slowing down the fast pace of modern life. Early automobile advocates claimed that railroads were simply too fast. Elon Jessup, in his 1921 book, The Motor Camping Book, described the view from the train as “a blur.” In his 1928 book, Better Country, nature writer Dallas Lore Sharp remarked that railroads rushed “blindly along iron rails” in their “mad dash across the night,” offering passengers only “fleeting impressions.” Automobiles, on the other hand, promised a nostalgic return to a slower time. Harkening back to the “simpler” days of stagecoach and carriage travel, automobiles were “refreshingly regressive.” Instead of being rushed along by “printed schedules and clock-toting conductors,” motorists could stop and start whenever they wanted, or when natural obstacles intervened. A car trip was leisurely, allowing heightened attention to regional variation and uniqueness.

Motorists take a leisurely drive through the countryside on the cover of this September 1924 American Motorist magazine. / THF202475

All told, the automobile liberated the individual who “hated alarm clocks” and “the faces of the conductor who twice daily punched his ticket on the suburban train.” In his 1928 book, Dallas Sharp even claimed that motoring was, in fact, more patriotic than railroad travel because it encouraged people to enjoy the country “quietly” and “sanely.” As a result, the slower tempo of automobile travel was thought to be restorative to frayed nerves brought on by the increasingly hectic pace of life in an urban, industrial society.

No automobile had more impact on the American public than the Model T, introduced in 1908. Envisioned by Henry Ford as a car for “the great multitude,” the Model T was indeed “everyman’s car”—sturdy, versatile, thrifty, and powerful. While Model Ts sold well from the beginning, the low price, extensive dealer network, and easy availability of replacement parts led to a leap in Model T sales after World War I.

Brochure for the 1924 Ford Model T, promoting its use as a vehicle for family pleasure trips. / THF107809

The need and demand for better roads corresponded with the unprecedented rise in Model T sales. The first and most widely publicized of the new, independently funded cross-country highways was the Lincoln Highway (1912), which ran (at least on paper) between New York City and San Francisco, California. In 1916—ironically, the same year that national railroad mileage reached a peak—the U.S. government passed the Federal Aid Road Act, providing grants-in-aid to several states to fund road improvement. The railroad companies watched helplessly as the government subsidized improved roads that extended to villages and hamlets the railroads could never hope to reach.

Effie Price Gladding recounts her cross-country trip on the Lincoln Highway in this 1915 book. The cover points out the states she passed through along the route of this highway. / THF204498

By the end of the 1920s, due in large part to the unprecedented popularity of the Model T, automobiles had gained a “vice-like grip on the American psyche.” Total car sales had leaped from 3.3 million in 1916 to 23 million by the late 1920s. Motorists were not only opting to take cars rather than trains for their regular travel routines, but they were also beginning to take longer-distance trips than they had ever attempted before. As the 1920s closed, Americans were traveling five times farther in cars than in trains. Enthusiasm for the automobile remained high throughout the Great Depression of the 1930s, when massive new road and highway construction projects were initiated to stimulate employment.

Black Americans embraced automobiles to avoid discrimination and humiliation on public transportation—at least until they had to stop to eat, sleep, and fill up with gas. Beginning in 1936, the Negro Motorist Green Book listed “safe places” for Black motorists to stop in towns and cities across the country. / THF99195

Conversely, the Depression was devastating for the railroad companies, who abandoned a record number of miles of existing track during this decade. By the late 1930s, railroad companies were optimistically attempting to revive business by embracing modern new streamlined designs, which claimed to reflect aerodynamic principles and promised a smooth ride incorporating the latest standards of comfort and convenience. A new emphasis on speed led to numerous record-breaking runs.

For its speed, as well as its beauty, comfort, and convenience, the Wabash Railroad’s “Blue Bird Streamliner” of 1950 was touted as “The Most Modern Train in America.” / THF99239

After World War II, the lifting of wartime rationing, the inclusion of two-week paid vacations in most labor union contracts, pent-up demand for consumer goods, and general postwar affluence ensured the automobile industry “banner sales,” which lasted into the 1950s.

Travel brochures like this one abounded after World War II, appealing to family vacationers. / THF202155

State-endorsed toll roads met the immediate postwar demand for motorists’ “right to speedy and accident-free travel over long distance.”

The Pennsylvania Turnpike, the first state-endorsed toll road, officially entered service on October 1, 1940. It currently stretches three times its original length. / THF202550

But the U.S. government’s long-time obsession with highway improvement truly reached a “dizzying crescendo” in 1956, with the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act. This Act called for 46,000 miles of state-of-the-art, limited-access superhighways, to be funded by public taxes on fuel, tires, trucks, buses, and trailers. Although justified for military and national defense purposes, the interstate highway system made it possible for average citizens to reach their destinations faster in their cars than by taking trains.

Although the new urban expressways were promoted as modern advantages, as seen in this 1955 “Auto-Owners Expressway Map” for the Detroit area, in fact, these same expressways cut through and often devastated poor and historically marginalized communities. / THF205968

Ironically, as automobiles became the standard vehicle for long-distance transportation, and highways beckoned motorists with higher speed limits and improved surfaces, the slow, leisurely pace of motoring—so lauded 50 years earlier—had transformed into an outpacing of even the “blurring” speed of railroads.

The wonder of the fast and efficient new expressways is evident in the child’s expression in this 1959 promotional photograph, as he views a futuristic model highway envisioned by researchers at General Motors. / THF200901

For the most part, travelers rejoiced as four-lane divided highways replaced the older two-lane highways. With the new speed and comfort features of cars and improved highways, the impulse toward getting somewhere as rapidly and efficiently as possible, along the straightest path, became the new end goal.

Sources consulted include:

- Belasco, Warren James. Americans on the Road: From Autocamp to Motel, 1910-1945. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1979.

- Douglas, George H. All Aboard: The Railroad in American Life. New York: Paragon House, 1992.

- Gordon, Sarah H. Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This blog post is adapted from her M.A. Thesis, “American Dreams and Railroad Schemes: Cultural Values and Early-Twentieth-Century Promotional Strategies of the Wabash Railroad Company” (University of Michigan-Dearborn, 2013).

Additional Readings:

- Steam Locomotive "Sam Hill," 1858

- Canadian Pacific Snowplow, 1923

- Model Train Layout: Demonstration

- Fair Lane: The Fords’ Private Railroad Car

20th century, 19th century, travel, trains, roads and road trips, railroads, Model Ts, cars, by Donna R. Braden

Kemmons Wilson’s Holiday Inns

Detail, THF104041

At a time when Americans are traveling less and the lodging industry is making big changes, let’s take a look back at the story of Kemmons Wilson, whose Holiday Inns revolutionized roadside lodging in the mid-20th century.

In the early days of automobile travel, motorists had few lodging options. Some stayed in city hotels; others camped in cars or pitched tents. Before long, entrepreneurs began to offer tents or cabins for the night.

Auto Campers with Ford Model T Touring Car and Tent, circa 1919 THF105459

More from The Henry Ford: Here’s a look inside a 1930s tourist cabin. Originally from the Irish Hills area of Michigan, the cabin is now on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. For motorists weary of camping out, these affordable “homes away from home” offered a warmer, more comfortable night’s sleep than a tent. You can read more about tourist cabins and see photos of this one on its original site in this blog post.

THF52819

Soon, “motels” -- shortened from “motor hotels” -- evolved to meet travelers’ needs. Compared to other lodging options, these mostly mom-and-pop operations were comfortable and convenient. They were also affordable. This expert set showcases the wide variety of motels that dotted the American landscape in the mid-20th century.

Crouse's Motor Court, a motel in Fort Dodge, Iowa THF210276

More from The Henry Ford: Photographer John Margolies documented the wild advertising some roadside motels employed to tempt passing motorists (check out some of his shots in our digital collections), and our curator of public life, Donna Braden, chatted with MoRocca about motorists’ early lodging options on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation (you can watch here).

After World War II, more Americans than ever before hit the open road for business and leisure travel. Associations like Best Western helped travelers find reliable facilities, but motel standards were inconsistent, and there was no guarantee that rooms would meet even limited expectations. When a building developer named Kemmons Wilson took a family road trip in 1951, he got fed up with motel rooms that he found to be uncomfortable and overpriced (he especially disliked being charged extra for his children to stay). Back home in Memphis, Tennessee, he decided to build his own group of motels.

As a young man, Wilson (born in 1913) displayed an entrepreneurial streak. To help support his widowed mother, Wilson earned money in many ways, including selling popcorn at a movie theater, leasing pinball machines, and working as a jukebox distributor. By the early 1950s, Wilson had made a name for himself in real estate, homebuilding, and the movie theater business.

Later in life, Kemmons Wilson tracked down his first popcorn machine and kept it in his office as a reminder of his early entrepreneurial pursuits. Detail, THF212457

Kemmons Wilson trusted his hunch that other travelers had the same demands as his own family -- quality lodging at fair prices. He opened his first group of motels, called “Holiday Inns,” in Memphis starting in 1952. Wilson’s gamble paid off -- within a few years, Holiday Inns had revolutionized industry standards and become the nation’s largest lodging chain.

An early Holiday Inn “Court” in Memphis, 1958 THF120734

What set Holiday Inns apart? Consistent, quality service and amenities Guests could expect free parking, air conditioning, in-room telephones and TVs, free ice, and a pool and restaurant at each location. And -- Kemmons Wilson determined -- no extra charge for children!

Swimming Pool at Holiday Inn of Daytona Beach, Florida, 1961 THF104037

Thanks to the chain’s reliable offerings (including complimentary toiletries!), many guests chose a Holiday Inn for every trip.

Holiday Inn Bar Soap, 1960-1970 THF150050

Holiday Inn Sewing Kit, circa 1968 THF150119

Inspired by Holiday Inns’ success, competitors began offering many of the same services and amenities. Kemmons Wilson had set a new standard -- multistory motels with carpeted, air conditioned rooms became the norm.

"Sol-Mar Motel," an example of a Holiday Inn-style motel in Jacksonville Beach, Florida THF210272

Kemmons Wilson knew location was key. He chose sites on the right-hand side of major roadways (to make stopping convenient for travelers) and took risks, buying property based on plans for the new Interstate Highway System.

Holiday Inn adjacent to highways in Paducah, Kentucky, 1966 THF287335

Holiday Inns’ iconic “Great Signs” beckoned travelers along roadways across the country from the 1950s into the 1980s. Kemmons Wilson’s mother, Ruby “Doll” Wilson, selected the sign’s green and yellow color scheme. She also designed the décor of the original Holiday Inn guestrooms!

Holiday Inn "Great" Sign, circa 1960 THF101941

Holiday Inns unveiled a new "roadside" design in the late 1950s: two buildings -- one for guestrooms and one for the lobby, restaurant, and meeting spaces -- surrounding a recreational courtyard. These roadside Holiday Inns featured large glass walls. The inexpensive material lowered construction costs while creating a modern look and brightening guestrooms. The recreated Holiday Inn room in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation demonstrates the “glass wall” design. Take a virtual visit here.

Holiday Inn Courtyard, Lebanon, Tennessee, circa 1962 THF204446

After becoming a public company in 1957, Holiday Inns developed a network of manufacturers and suppliers to meet its growing operational needs. To help regulate and maintain standards, property managers (called “Innkeepers”) ordered nearly everything -- from linens and cleaning supplies to processed foods and promotional materials -- from a Holiday Inns subsidiary. This menu, printed by Holiday Inns’ own “Holiday Press,” shows how nearly every detail of a guest’s stay -- even meals -- met corporate specifications.

Holiday Inn Dinner Menu, February 15, 1964 THF287323

By the 1970s, with more than 1,400 locations worldwide, Holiday Inns had become a fixture of the global and cultural landscape. Founder Kemmons Wilson even made the cover of Time magazine.

Time Magazine for June 12, 1972 THF104041

We hope his story inspires you to make your own mark on the American landscape -- or at least take a fresh look at the roadside the next time you’re out for a drive, whether down the street or across the country!

Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content at The Henry Ford, has happy poolside memories from a childhood stay at one of Holiday Inns’ family-friendly “Holidome” concepts. For more on the Holiday Inn story, check out chapter 9 of "The Motel in America," by John Jakle, Keith Sculle, and Jefferson Rogers.

20th century, travel, roads and road trips, hotels, entrepreneurship, by Saige Jedele, #THFCuratorChat

Be Empathetic like AAA

THF171209 / Automobile Club of Michigan Sign

It was my privilege to take over The Henry Ford’s Twitter feed for a while on the morning of May 14. Our theme for the day was "Be Empathetic." To me that means "be helpful and supportive," and those attributes remind me of early auto organizations like the Automobile Club of Michigan, founded in 1916. The Automobile Club of Michigan is one of several regional organizations that joined the American Automobile Association. Over the years, AAA’s work has included advocating for better roads, providing roadside assistance to stranded motorists, encouraging traffic safety generally – particularly near schools, and promoting tourism and travel by car throughout the United States. During my Twitter session, I shared several AAA items in the collections of The Henry Ford.

To the Rescue on the Road

THF103500 / Pamphlet from AAA of Michigan, "Emergency Road Service Guide," June 1951 / front

AAA began offering emergency roadside service in 1915. This 1951 pamphlet lists affiliated service garages throughout Michigan.

THF333431 / 1947 Ford Repair Truck at the Ralph Ellsworth Dealership, Garden City, Michigan, October 1946

This photo shows one of the AAA-affiliated wreckers that might've come to your aid in the late 1940s or early 1950s. In this case, it's a 1947 Ford.

THF304296 / Toy Truck, Used by James Greenhoe, 1937-1946

Children could play their own "roadside assistance" games with a toy truck like this one, made circa 1940.

Keeping Children Safe

THF153486 / Automobile Club of Michigan Safety Patrol Armband, 1950-1960

Speaking of children, one of AAA's most important initiatives is its School Safety Patrol program, established in 1920.

THF208042 / Music Sheet, "The Official Song of the Safety Patrol," 1937

Safety patrollers help adults in protecting students at crosswalks, and in bus and car drop-off and pick-up zones. Their dedicated efforts were celebrated in "Song of the Safety Patrol" from 1937.

THF289667 / Detroit Police Officer Anthony Hosang Talks with Safety Patrol Students on a Tour of the Ford Rouge Plant, May 10, 1950

Here's a group of Detroit safety patrol members in 1950. They're listening to police officer Anthony Hosang as a part of a tour through Ford's Rouge Plant – a reward for a job well done.

Reaching Your Destination

THF104025 / "Official Highway Map of Michigan," Automobile Club of Michigan, 1934

AAA also helps drivers find their way by publishing road maps. Here's one showing the Detroit metro area in 1934. Many of the highway numbers are familiar, but their routes have changed.

THF136038 / Log and Map of Automobile Routes between Detroit-Gary and Chicago, 1942

Here's a map of routes between Detroit and Gary-Chicago in 1942. The northern-most route (then U.S. 12) parallels modern I-94.

THF151706 / Automobile Club of Michigan, "Know Michigan Better, Stay Longer," Sign, 1950-1960

AAA also promotes tourism, encouraging drivers to explore America – and their own states. Residents can "know Michigan better," and visitors can "stay longer."

THF14793 / Travel Brochure for Holland Michigan, circa 1940

Springtime brings tulips, and what better place to enjoy them then Holland? (Holland, Michigan, that is.)

THF14744 / Souvenir Book, "Northern Michigan, Lower Peninsula," 1940

Here's a AAA guidebook promoting travel to Michigan's northern Lower Peninsula.

THF9103 / Host Mark Magazine, "Greenfield Village & Henry Ford Musem, A Bicentennial Site," 1976

And here's a familiar sight on the cover of AAA's Host Mark magazine. It's Greenfield Village, where bicentennial celebrations were underway throughout 1976.

It was great fun sharing these pieces with our Twitter followers. I also enjoyed answering some questions about our wider transportation holdings along the way. “Be Empathetic” – it’s an important lesson anytime, but especially right now.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

roads and road trips, travel, cars, by Matt Anderson, AAA, #THFCuratorChat

Family Fun in the Family Car

A happy family on a road trip inside their 1958 Edsel Bermuda Station Wagon. THF124600

Nothing epitomizes the 20th-century American family vacation more than the station wagon. After World War II, as family vacationers flooded the highways out to enjoy all that America had to offer, the station wagon became the quintessential family car. Although they had been around for a few decades, station wagons by this time had become roomier, more comfortable, and more within the reach of family budgets.

As shown in this circa 1953 Coleman brochure, station wagons proved the perfect vehicle for families who needed to haul lots of gear for their “back to nature” camping vacations. THF275653

When limited-access turnpikes and interstate freeways expanded across the country during the 1950s and 1960s, sales of station wagons exploded. From three percent of all cars sold in 1950, sales of these cars mushroomed to 10 times that in 1955. By the end of the decade, some one in every five cars sold was a station wagon.

As family vacation trips lengthened, so did the time family members spent on the road together in the car. However, even though the ads claimed that vacations taken in a roomy, comfortable station wagon could improve family relations, this wasn’t always the case. Younger family members, in particular, inevitably got cranky and bored--threatening any attempt at family togetherness and fun. Enter a host of family car games and activities.

Mom and the kids read together in the back seat of the family car, with apparent disregard for “buckling up” for safety. THF275640

During the 1950s and 1960s, inventive game manufacturers, creative writers, and ingenious publishers devised all manner of family games and activities. These were intended to keep family members occupied, reinforce family togetherness, and increase the fun of traveling together.

Book of Ford Travel Games, free dealer giveaway, 1954. THF206270

During the post-World War II era, many of the car games and activities with which we are still familiar today were published and disseminated. This 1954 Ford dealer giveaway book was dedicated to the author’s four teenagers, “whose restlessness during childhood days first made these games necessary.” Most games in it, intended to be played by young and old, were the “scavenger” type, that would “help much to pass the time in an enjoyable manner” while “affording an opportunity for all members of the family to enjoy doing things together during the long hours on a motor trip.” The object of these scavenger-type games was to see who was the first one to find the items on the list, including car license plates, animals, sounds, and songs. Other games and contests included the classic I Spy game, a memory game called My Grandfather’s Trunk, and identifying shapes by looking at cloud formations.

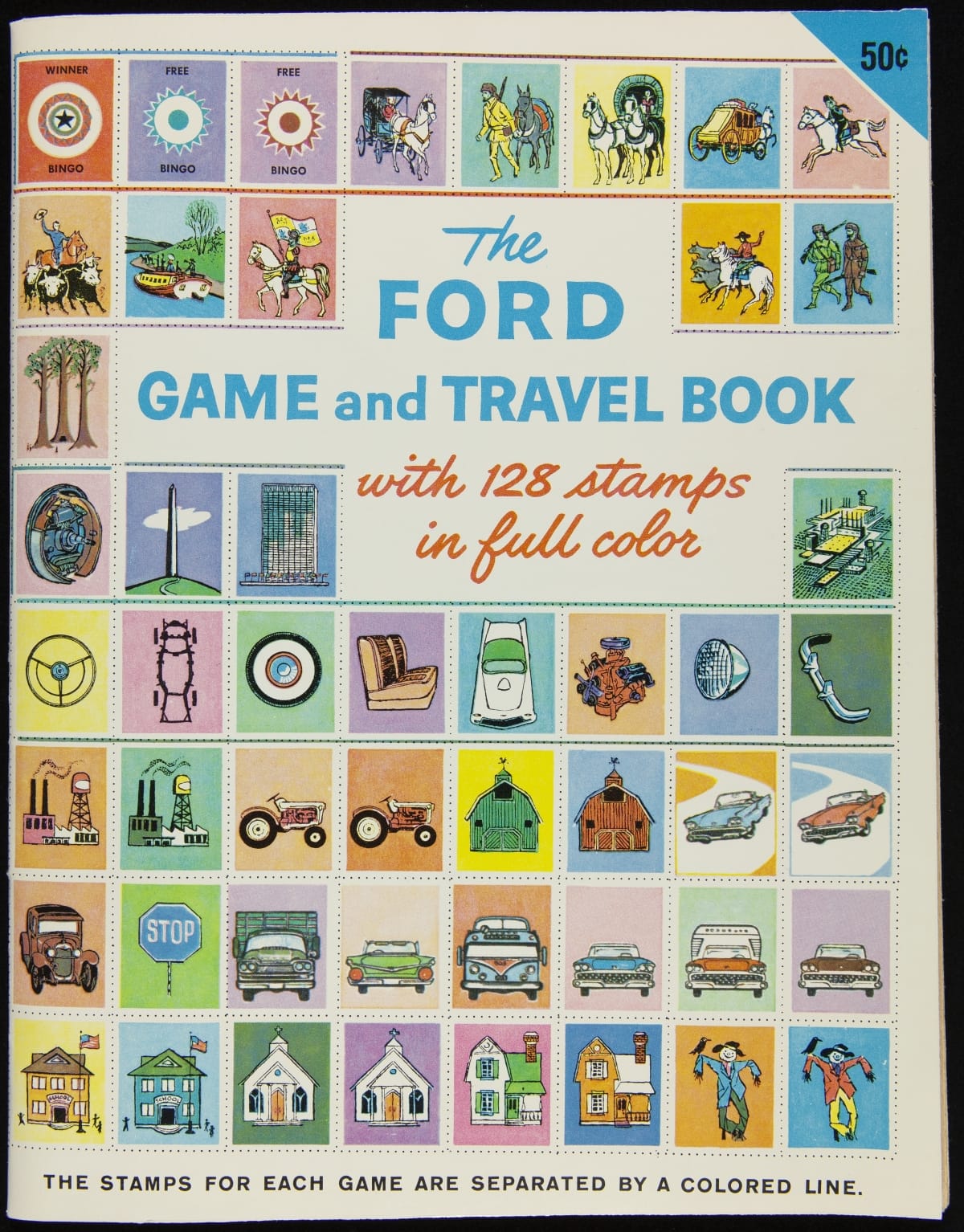

Ford Game and Travel Book with stamps, 1959. THF275639

The 1959 Ford Game and Travel Book included games, songs, stories, riddles, and information enough to “provide hours and hours of pleasure for the whole family during the trip.” It included 128 full-color stamps to affix to various pages. The games and activities were much the same as those in the 1954 Travel Games book.

Fun on Wheels book for AAA, by Dave Garroway, 1960. THF275643

Dave Garroway, the founding host and anchor of NBC’s Today TV show from 1952 to 1961, was known for his easy and relaxing style. By the time this book was published in 1960 for members of the American Automobile Association, Garroway would have been a familiar name in most households. This book of “sit-able” games, quizzes, riddles, contests, puzzles, songs, and coin tricks “guaranteed miles of motoring pleasure” and was intended to “make any trip easier, safer, and more agreeable for parents and youngsters alike.”

Auto Bingo game, 1960s. THF140655

Auto Bingo, a product of the Regal Games Manufacturing Company from Chicago, Illinois, was introduced in the 1950s and proved incredibly popular during succeeding decades. The classic game, shown here, is still produced today.

Traffic Sign Bingo, 1960s. THF140659

The popularity of the classic Auto Bingo game spawned many variations, like this Traffic Sign Bingo, with magnetic game pieces.

Ad for 1984 Chevrolet Celebrity Estate station wagon. THF275646

Although the OPEC oil crisis and tougher emission standards dealt a blow to the station wagon market in the 1970s, station wagons were still considered the family vacation vehicle of choice. By the early 1980s, these vehicles had greatly expanded in size and comfort over their 1950s counterparts. Manufacturers promoted their spaciousness, like this ad that likened the 1984 Chevrolet Celebrity Estate wagon to a family room! This is, in fact, the very type of vehicle that was satirized in the 1983 film National Lampoon’s Vacation--although the Griswold family’s clunky green Family Truckster was actually a modified 1979 Ford LTD Country Squire.

Fisher-Price mini-van toy, a repackaged version of the company’s earlier mini-school bus, 1986-90. THF150890

While we may have chuckled at the Griswolds’ Family Truckster in 1983, the future of the station wagon as a family vacation vehicle was, in fact, no laughing matter. Families would soon prefer roomy minivans, introduced in 1984, and fully-featured SUV’s in the 1990s, to haul kids and luggage on long-distance trips.

The family vehicle pictured on the cover of this 1985 travel game and activity book is more akin to a minivan than a station wagon. THF275648

As family road trips continued in subsequent decades, such innovations as portable music and gaming devices and in-car DVD players came to occupy and entertain family members during long trips.

A 1982 redesign of the original Sony Walkman, the first portable audio cassette player introduced in 1979. THF153124

But classic family games and activities persisted, in both traditional and newer versions.

This set contained 10 games (including Solitaire, Checkers, and Mini-Chutes and Ladders). Its interchangeable game board contained holes to hold peg-like game pieces in place. THF140658

Scrabble isn’t the best idea for a travel game, as letters are small and can easily get lost. Later versions of this game came with magnetic letters. THF106452

Today, we have a plethora of personal and mobile technologies to keep individuals occupied in the car on long-distance vacations (if they don’t opt for much speedier air travel). But these devices also separate and isolate members of the family. It’s nice to know that, if you want, you can still find classic family car games and activities online or available as digital downloads. And, of course, there’s still the old way of learning the classic games--passed down from parent to child.

Anyone for a rousing game of I Spy?

Donna R. Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life, grew up in a large family and took many family vacations with her parents and four brothers in their Country Squire station wagon.

childhood, by Donna R. Braden, toys and games, cars, travel, roads and road trips