Monthly Archives: February 2012

Cozying Up to a New Acquisition – Susan McCord Triple Irish Chain Quilt, circa 1900

People often send us letters offering items for our collection. Recently, I received a letter in the mail that surprised and absolutely delighted me.

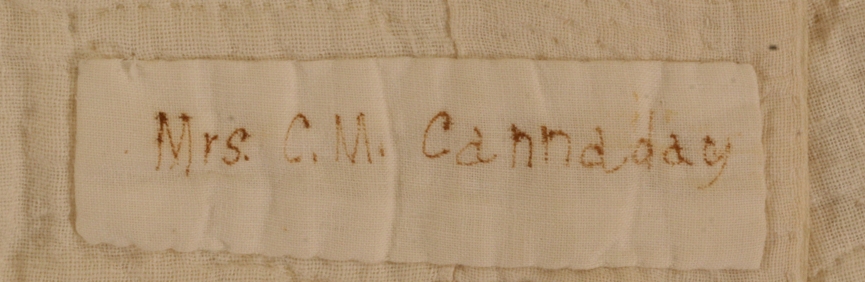

Among the notable collections of The Henry Ford are 12 quilts made by an exceptionally talented, unassuming Indiana farm wife named Susan McCord (1829-1909). I opened the letter to find that the family of McCord’s great-grandson was offering us the opportunity to acquire one more: a Triple Irish Chain quilt made for her daughter, Millie McCord Canaday, about 1900.

It was the last remaining quilt known to have been made by Susan McCord. Soon after, this beauty was on its way to Dearborn to join the other 12 McCord quilts in The Henry Ford’s collection.

The Triple Irish Chain is a traditional quilt pattern — but in Susan McCord’s hands, this design became much more. Like all of her quilts, the Triple Irish Chain demonstrates McCord's considerable skill at manipulating fabric, color and design to turn a traditional quilt pattern into something extraordinary.

I could easily imagine Susan McCord carefully choosing fabric from her bag of scraps, cutting it into thousands of fabric squares, carefully determining their placement within the overall design and sewing the squares together. I could picture McCord then topping off this creation with her utterly unique, “signature” design — a stunning vine border, the leaves expertly pieced from tiny scraps of fabric. And it certainly wasn’t hard to imagine Millie McCord’s delight when she received this lovely gift!

To all who see Susan McCord’s quilts - whether experts or casual observers - the remarkable beauty and craftsmanship is evident. Now beautifully photographed, the story of this quilt can be readily accessed through our online collections – so that anyone, near or far, can enjoy McCord's quilt at the click of a mouse.

Do you have any special family quilts or other handmade heirlooms? Share your story in the comments below or on our Facebook page.

Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford, is an unabashed Susan McCord “groupie.”

Indiana, women's history, quilts, making, design, by Jeanine Head Miller

Winter in Greenfield Village: Hanging Hams, Bacon and Fatback at Firestone Farm

Every winter, Firestone farmers work hard preserving meats from our December butchering. Hams, bacon and fatback are all cured using a process that would have been very familiar to the Firestones in 1885.

Every day, Firestone farmers rub these cuts of meat with a mixture of salt, sugar and various spices. The salt dehydrates the meat, while sugar prevents it from getting too tough and the spices help to give the meat a nice flavor. It takes several weeks for larger cuts of meat like hams to finish curing. Once a week, old cure is removed from the meat and it is replaced with fresh cure.

Once the meat is cured, it is wrapped in cheesecloth sacks and hung in the cold room located in Firestone Farm’s cellar.

Near the meat are several other foods that were preserved last year, including dried chili peppers, pickles and crocks of sauerkraut as well as jars of tomatoes, pickled green beans, applesauce and more.

When you visit from April through November, make sure to check out the Firestone home's cellar and cold room - you'll be sure to notice our cured meat hanging from the ceiling in our cold room...and as the year progresses and the time for butchering once again approaches, there will be very little cured meat left hanging in cheesecloth.

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, home life, food, farms and farming, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, winter

“George Washington Slept Here” --No, Really!

Dotting the landscape of places like Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York are numerous Colonial-era homes and taverns where George Washington is said to have spent the night. Some of these claims are true; some are likely only wishful thinking. But the desire to claim a tangible connection to our Revolutionary War hero and first president runs strong.

As commander of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, General George Washington usually did sleep and eat in the nearby homes of well-to-do people during the eight years he led the American military campaign. But among George Washington’s camp equipage were tents, this folding bed, cooking and eating utensils, and other equipment that he used when encamped on the field with his troops.

Yet the George Washington camp bed in The Henry Ford’s collections is more than just a humble cot, used when no better option was available. This object symbolizes George Washington as a leader who cared more about his men and the cause of democracy than he did for himself.

In Henry Ford Museum’s With Liberty and Justice for All exhibit, visitors stand in quiet contemplation before the Washington camp bed on display, gazing at a humble cot where the great general took some weary rest during the struggle for American independence.

A great many stories of American ingenuity and innovation abound in Henry Ford Museum. But these stories generally do not involve military history. Why, then, display a bed associated with war?

With Liberty and Justice for All explores the proud and painful evolution of American freedom, from the Revolutionary War through the struggle for civil rights. This exhibit, then, is about social innovation: new ideas that render old ways obsolete and radically alter how people think about themselves, their interactions with others, and the larger world.

The Revolutionary War became about more than just American independence from Britain. It evolved into a new way of thinking: that it was possible for a people to govern themselves through a democratic system of elected representatives. The Revolutionary War also launched Americans on the road toward a newfound sense of national identity as Americans, rather than British subjects, New Englanders or Virginians. And George Washington was at the center of that new way of thinking.

Continue Reading18th century, presidents, Henry Ford Museum, by Jeanine Head Miller

First Known Portrait of Thomas Alva Edison, circa 1851

Since Thomas Edison’s birthday happened to be this past Saturday (February 11), it made me think of this first known portrait of him.

Even after 35 years of working with the museum’s photograph collections, this 3 x 2-3/4 inch daguerreotype still gives me goose bumps when I look at it. Made at the dawn of photographic technology, it serves as a powerful reminder of the unique connection between Henry Ford and Thomas Edison.

Because of Henry Ford's friendship with Edison, many objects, photographs and manuscripts became part of the museum's collections, including Edison's Menlo Park Laboratory.

This daguerreotype was a gift to us from Edison’s widow, Mina, probably in the 1930s. The depth of Henry Ford’s admiration for Thomas Edison was so great that he named his museum and village "Edison Institute" in honor of the inventor. The dedication ceremony occurred on October 21, 1929, to coincide with Light's Golden Jubilee, the 50th anniversary of Edison's invention of the electric incandescent light bulb.

I find it fascinating to view this photographic image of the famous inventor when he was just a child. Daguerreotypes, invented in 1839, became very popular in the United States from the 1840s through the mid 1850s. The process took about 20 seconds, and Edison, shown at age 4, had to sit completely still! His seriousness and look of concentration go beyond the need for stillness. It seems to me that he is thinking about how and why the camera is working as much as obeying the adult admonition not to move.

Cynthia Read Miller, former Curator of Photographs and Prints at The Henry Ford, is continually fascinated with the museum’s over one million historical graphics.

Additional Readings:

- Edison at Work

- Edison's Light Fantastic

- Light’s Golden Jubilee Honors Thomas Edison and Dedicates a Museum

- Thomas Edison Photographs

archives, photographs, inventors, Thomas Edison, childhood, by Cynthia Read Miller

“Tuning” the Dymaxion House

“You must be this small to enter.” How many times do you hear that in the workplace?

This week, our historic operating machinery specialist, Tim Brewer, and I have been squeezing between tie-down cables and sliding around underneath R. Buckminster Fuller's "house of the future," the Dymaxion House. We were part of the original team that restored this unique prototype and built it inside Henry Ford Museum.

Now, for the first time since it opened in October 2001, we have closed the house to the public; this shutdown will be for as brief a time as possible - we promise! - but it is essential to ensure the long-term preservation of the structure. (In the meantime, you can still view the exhibit and the exterior of the house from the platform.)

So what exactly is happening to the Dymaxion House during this time?

This extraordinary structure really does hang from the mast, with a cabled hoop (“cage”) system that the exterior wall “skin” floats on. We are using laser-levels to assess the relative movement of components in the cage system.

In addition, the flooring system (or deck) is made of hollow aluminum “beams,” with plywood attached with clip strips of bent aluminum. Right now we are determining the extent of wear on the deck after 10 years of relatively trouble-free service.

As expected, we are finding more deterioration in the flooring path where visitors walk through the artifact, and we’ll be working hard over the next little while to repair any damages so our favorite house can delight the public for years to come. More details to come in a future post!

Senior Conservator Clara Deck has been a conservator at The Henry Ford for 20 years. Preserving the material integrity of the objects is her job - but making them look great is icing on the cake.Additional Readings:

- Dymaxion House

- Gauging the Condition of the Dymaxion House

- Dymaxion House

- Drawing, "The Dymaxion House at Henry Ford Museum," 2002

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum, conservation, collections care, by Clara Deck, Dymaxion House, Buckminster Fuller

Sending out an SOS

On August 11, 1909, as his ship struggled off Cape Hatteras, telegraph operator Theodore Haubner had an urgent choice to make: How should he call for help?

Haubner worked the key on the commercial steamship S.S. Arapahoe. His ship had just broken her propeller shaft and was drifting off the North Carolina coast.

For years, ships in trouble had used the telegraph code “CQD,” which means “calling all stations—distress.” But a new code for distress had recently been agreed upon: “SOS.” Would anyone recognize it?

Deciding to split the difference, Haubner signaled SOS as well as CQD—and his ship was picked up just twelve hours later.

Haubner had sent the world’s first SOS signal. He later donated his headphones and telegraph key to The Henry Ford, where they are now on exhibit in our Driving America exhibit.

Wireless telegraphy, perfected only a decade earlier by inventor and entrepreneur Guglielmo Marconi, used radio waves to connect ships with one another as well as with stations on land. In 1904, CQD was adopted by Marconi Company wireless telegraph operators as their emergency signal.

But an international industry would need an internationally standardized emergency signal. At the second International Radiotelegraphic Convention in Berlin, in 1906, participants agreed on SOS as the international distress signal. They chose SOS not because it was an abbreviation for any particular distress call (it does not stand for “save our ship,” as many have thought), but because it was easy to send and receive - three dots, three dashes, three dots. When the Arapahoe was drifting, the signal was just coming into use.

So why are these telegraph artifacts in an exhibit on cars?

When Haubner sent that first SOS in 1909, American culture was adjusting to a feeling of new, wider horizons. Wireless telegraphy was one of many technological marvels making their way into culture and, more slowly, into everyday life. Another of those marvels was the automobile.

Driving America puts cars into the context of these new visions of the future - this optimism that new technology, standardized across the world, could do anything.

Saving a ship was only the beginning.

Suzanne Fischer is the Associate Curator of Technology at The Henry Ford. She typed this post on an 1880s index typewriter and sent it to the blog editor via telex.

North Carolina, telegraphy, technology, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, communication, by Suzanne Fischer, 20th century, 1900s