Monthly Archives: March 2018

Mrs. Potts, Inventor

Mrs. Potts type flatiron made by A. C. Williams Company of Ravenna, Ohio, 1893-1910. THF171197

A "Cool Hand" Who Always Came to the "Point"

In the early 1870s, a young wife and mother had a better idea for making the arduous task of ironing easier. Her name was Mrs. Potts.

At this time, people smoothed the wrinkles from their clothing with flatirons made of cast iron. These irons were heavy. And needed to be heated on a wood stove before they could be used—then put back to be reheated once again when they began to cool. (Automatic temperature control was not to be had.)

Mary Florence Potts was a 19-year-old Ottumwa, Iowa, wife and mother of a toddler son when she applied for her first patent in October 1870, one reissued with additions in 1872. Mrs. Potts’ improved iron had a detachable wooden handle that stayed cool to the touch. (Conventional irons had cast iron handles that also got hot as the iron was heated on the stove— housewives had to use a thick cloth to avoid burning their hands.) Mrs. Potts’ detachable wooden handle could be easily moved from iron to iron, from one that had cooled down during use to one heated and ready on the stove. This curved wooden handle was not only cool, but also more comfortable—alleviating strain on the wrist.

Mrs. Potts’ iron was lighter. Rather than being made of solid cast iron, Mrs. Potts came up with idea of filling an inside cavity of the iron with a non-conducting material like plaster of Paris or cement to make it lighter, and less tiring, to use. (Florence Potts’ father was a mason and a plasterer, perhaps an inspiration for this idea.)

Previous iron design had a point only on one end. Mrs. Potts’ design included a point on each end, to allow the user to use it in either direction.

Mrs. Potts appeared on trade cards advertising her irons. This one dates from about 1883. THF214641

Mrs. Potts appeared on trade cards advertising her irons. This one dates from about 1883. THF214641

Mrs. Potts’ innovations produced one of the most popular and widely used flatirons of the late 19th century. It was widely manufactured and licensed in the United States and Europe with advertising featuring her image. Mrs. Potts’ iron was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Millions of visitors attended the exhibition.

The Potts iron became so popular that by 1891, special machines were invented that could produce several thousand semicircular wood handles in a single day, rather than the few hundred handles produced daily with earlier technology. Mrs. Potts' type irons continued to be manufactured throughout the world well into the twentieth century.

Though Mrs. Potts proved her inventive mettle with her innovative flatiron design, it appears that she did not reap spectacular financial rewards—at least by what can be discerned from census records and city directories. By 1873, the Potts family had moved from Iowa to Philadelphia, where her daughter Leona was born. They were still living there in 1880, when the census mentions no occupation given for any family member. Perhaps, if Mrs. Potts and her family became people of leisure, it was only for a time. Whether through need or desire, the Potts family had moved to Camden, New Jersey by the 1890s, where Joseph Potts and son Oscero worked as chemists. Joseph Potts died in 1901. By 1910, Florence and Oscero were mentioned as owners of Potts Manufacturing Company, makers of optical goods.

Mrs. Potts’ creativity made the tough task of ironing less onerous for millions of women in the late 19th century. And—though most are unaware—the story of the inventive Mary Florence Potts lives on in the many thousands of irons still found in places like antique shops and eBay.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

New Jersey, Pennsylvania, 19th century, 1870s, women's history, home life, by Jeanine Head Miller

Your Home Away from Home

By the 1930s, many motorists had grown weary of camping out. Turned out it wasn’t much fun cooking meals, sleeping in crude tents, and roughing it with primitive equipment and few amenities. Homey little cabins like this one, which were increasing in number at the time, seemed much more appealing. Often home-built by the property owners with a little elbow grease and a can-do attitude, these offered privacy, a modicum of comfort, and a needed respite on the journey from home to one’s final destination.

This tourist cabin, now in the “Driving America” exhibition in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, was once part of a group of cabins clustered together along U.S. Route 12 in Michigan’s picturesque Irish Hills region. Originally called the Lore Mac Cabins, this modest cabin complex was built between 1935 and 1938. Today this cabin looks much as it did back then, with many of its original fixtures and furnishings.

Come now on a tour of the Lore Mac Cabins, as a series of snapshots and personal reminiscences give us a glimpse of what the place was like back in the 1940s.

The cabins were arranged in a semi-circle along a dirt road. Common bathroom facilities were located behind the main office and the owner’s residence (visible in the foreground of this snapshot). Men’s and women’s shower facilities were located here as well.

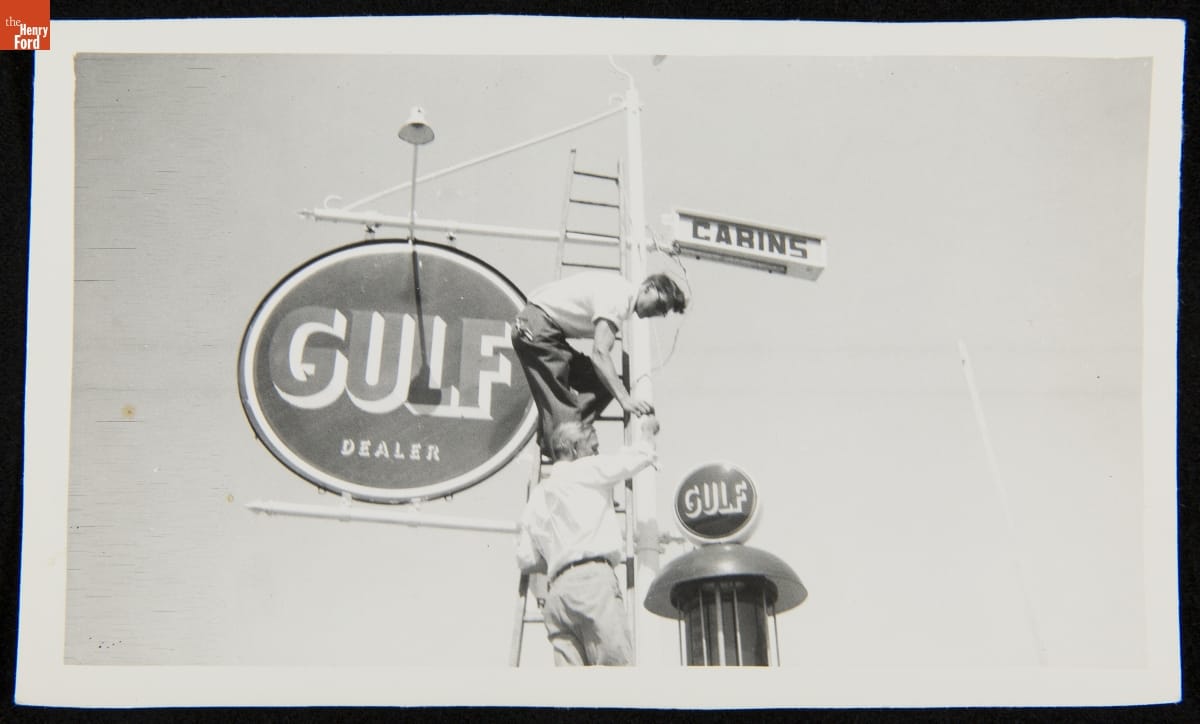

The owner of the Lore Mac Cabins was also an approved Gulf gasoline dealer. Two gasoline pumps out in front beckoned both overnight guests and other motorists needing to fill up while driving along busy Route 12 between Detroit and Chicago.

The cabin proprietors lived behind the office in which lodgers registered for their nightly stay. Here the daughter of the owner (and donor of the snapshot) poses self-consciously on the back porch of their residence.

The heat for the “heated cabins”--as advertised in large letters emblazoned across the main building--was provided by small, pot-bellied stoves in each cabin, fueled with wood or coal. The Gulf gasoline sign is visible out front.

In the early 1940s, the owner charged around $2.50 for a single cabin and four to five dollars for a double cabin. The interior walls of the cabins were lined with an inexpensive beaver board material while linoleum covered the floor. Throw rugs alongside the metal-frame beds added a touch of hominess. Guests not wanting to trek all the way to the central sanitation facility could use a white enamelware commode discreetly placed under the bed.

The chairs scattered about the property became a perfect place to pose for snapshots. Taking pictures provided a concrete reminder of a trip and might serve as free advertising for the proprietor when guests shared their adventures with family and friends back home.

Alas, competition eventually made it impossible for small Mom-and-Pop operations like the Lore Mac Cabins to survive. Travelers began to bypass tourist cabins like these for the improved amenities of motels, motor inns and, by the 1950s, standardized chains like Holiday Inn.

Cabins like those at the Lore Mac were certainly preferable to camping. But, despite the attempts by tourist cabin proprietors to offer “homes away from home” at a modest price and in an informal atmosphere, the days of these early bare-bones roadside lodgings were numbered.

Donna R. Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

travel, Driving America, Henry Ford Museum, Michigan, roads and road trips, by Donna R. Braden, hotels

Detroit Autorama 2018

Dodge Demon 1.0: “Insidious,” one of 800 hot rods and custom cars on view at the 2018 Detroit Autorama.

Dodge Demon 1.0: “Insidious,” one of 800 hot rods and custom cars on view at the 2018 Detroit Autorama.There’s still snow on the ground in the Motor City, but car show season is officially underway after the 66th annual Detroit Autorama, held March 2-4. Some of the wildest, weirdest and/or most beautiful customs and hot rods filled Cobo Center in a celebration of chrome and creativity. For those who’ve never been, Autorama is a feast for the eyes (and, at closing time when many of the entrants drive off under their own power, the ears). Some 800 cars, built by the most talented rodders and customizers in the country, are brought together under a single roof to be admired, coveted and judged. Wit is as much a part of the customizer’s toolbox as wrenches and rachets. Check out this 1955 Chevy “Bad Humor” ice cream truck, surrounded by used popsicle sticks.

Wit is as much a part of the customizer’s toolbox as wrenches and rachets. Check out this 1955 Chevy “Bad Humor” ice cream truck, surrounded by used popsicle sticks.

The most prestigious prize at Autorama is the Ridler Award, named in honor of show promoter Don Ridler. Only cars that have never been shown before are eligible. On Autorama’s opening day, the judges select their “Great 8” – the finalists for the Ridler. Anticipation builds throughout the weekend until the winner is announced at the end of the Sunday afternoon awards presentation. In addition to considerable bragging rights, the Ridler Award winner receives $10,000 and enshrinement in the online Winner Archive. This year’s Ridler went to “Imagine,” a silver 1957 Chevrolet 150 owned by Greg and Judy Hrehovcsik and Johnny Martin of Alamosa, Colorado. Our 2018 Past Forward winner, a 1956 Continental Mark II with a fifth-generation Chevy Camaro powertrain under the body.

Our 2018 Past Forward winner, a 1956 Continental Mark II with a fifth-generation Chevy Camaro powertrain under the body.

Each year The Henry Ford gives out its own prize to a deserving Autorama participant. Our Past Forward award recognizes a car that 1.) Blends custom and hot rod traditions with modern innovation, 2.) Exhibits a high level of craftsmanship, 3.) Captures the “anything goes” spirit of the hobby, and 4.) Is just plain fun. Our 2018 winner, a 1956 Continental Mark II owned by Doug Knorr of Traverse City, Michigan, and built by Classic Car Garage of Greenville, Michigan, had all these qualities in the right combination. Everything about the car said “Continental,” only more so – from the oversized turbine wheels to the elegant Continental star on the valve covers. And if the 400-horsepower LS3 Camaro V-8 under the hood doesn’t say “anything goes,” then I don’t know what does. The 1976 Dodge Monaco – notably a model made after catalytic converters, so it won’t run good on regular gas.

The 1976 Dodge Monaco – notably a model made after catalytic converters, so it won’t run good on regular gas.

If chrome-plated undercarriages aren’t your thing, then Autorama Extreme was there for you again this year on Cobo’s lower level. Shammy cloths and car polish are decidedly out of place among the Rat Rods down below. In addition to show cars, vendors and the ever-popular Gene Winfield pop-up chop shop, Autorama Extreme features a concert stage with ongoing musical entertainment. There’s always a healthy dose of 1950s rockabilly on the schedule, but this year’s lineup also included a Blues Brothers tribute act – complete with a 1976 Dodge Monaco gussied up (or down, I suppose) into a fairly convincing copy of the Bluesmobile. Unpolished and proud of it. A 1930 Ford Model A with the Rat Rods in Autorama Extreme.

Unpolished and proud of it. A 1930 Ford Model A with the Rat Rods in Autorama Extreme. Not everything at Autorama is textbook classic. Here’s a 1980 AMC Spirit patriotically living up to its name with lots of red, white and blue.

Not everything at Autorama is textbook classic. Here’s a 1980 AMC Spirit patriotically living up to its name with lots of red, white and blue.

“Lethal T,” for those who’ve always dreamed of putting a 427 Cammer in a Model T.

“Lethal T,” for those who’ve always dreamed of putting a 427 Cammer in a Model T.

If you haven’t been to Detroit Autorama, then make a point of being there in 2019. You won’t find anything quite like it anywhere else in the world.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, Michigan, Detroit, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson, Autorama

Celebrating Women at Atari

The familiar silver packaging for the “Black Vader” Atari 2600 was created by Evelyn Seto, who led the Atari design team with John Hayashi. THF160364

Cardboard boxes printed in bold colors: shimmering silver, blazing orange, primary blue, circus purple—hot pink. Overlaid with white and yellow Bauhaus typography announcing the contents: Centipede, Breakout, Space Invaders. Inside the box, a black plastic cartridge that holds the promise of video game entertainment, all from the comfort of home. Games played while sitting cross-legged on the floor. Later, aching hands from hours of play on a square, non-ergonomic, one-button joystick. No quarters necessary. By the fall of 1977, there was no denying the fact that the arcade was successfully finding its way into the living room.

The Atari Video Computer System (later sold as the Atari 2600) changed the gaming industry. Earlier systems like the Magnavox Odyssey, Home PONG, and the Fairchild System F were available in the early 1970s, but the remarkable success of the Atari 2600 defined a “second generation” of home consoles, selling over 30 million units between 1977 and 1992.

The number of games available for the 2600—taking into account Atari and Sears releases as well as those by third-parties like Activision and Imagic—finds us looking at approximately 550 unique titles. Several games within this vast library include important contributions made by women.

Female employees were not uncommon at the company. Carol Kantor became the first market researcher at a video game company, ever. Wanda Hill drew the circuit diagrams for Asteroids. Judy Richter worked as a packaging designer and production manager for a decade, through multiple leadership transitions. The people working on the assembly lines populating the circuit boards for arcade games were almost all women. Evelyn Seto supervised the design team, inking the original three-pronged “Mt. Fuji” logo and creating the shelf-appealing silver packaging for the Atari 2600. Dona Bailey and Ed Logg’s 1980 arcade version of Centipede was translated as a “port” for the Atari 2600 in 1982. In 2013, this cartridge was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” located in an Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill. THF159973

Dona Bailey and Ed Logg’s 1980 arcade version of Centipede was translated as a “port” for the Atari 2600 in 1982. In 2013, this cartridge was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” located in an Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill. THF159973

The scales were not exactly balanced in terms of gender equality within Atari’s engineering staff, but take for instance the work of Dona Bailey, programmer of the arcade version of Centipede (1980). Not only was she the first female programmer to design an arcade game, but her collaboration with Ed Logg led to the creation of one of the most iconic video games of all time.

When Carol Shaw created 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, she became the first professional female video game developer. THF171081

Carol Shaw & Susan Jaekel

Dona Bailey’s time in the “coin-op” division at Atari overlapped with Carol Shaw’s work for the “cart” division. In 1977, Shaw graduated from the University of California, Berkeley’s Computer Science program, and was hired as the first female programmer at Atari in August 1978. When she completed her first cartridge game that year—3D Tic-Tac-Toe—she effectively became one of the women to work in the professional video game industry. 3D Tic-Tac-Toe is an abstract strategy video game based on a game called Qubic, which was originally played on room-sized computers in the mid-1950s.

In the 1970s and 80s, the exterior graphics of a coin-op console or the illustration on a game’s cardboard box were often a player’s first exposure to a game. Typically, the vibrant and dynamic graphics promoting a game were light years beyond the pixelated game that showed up on the screen. Nonetheless, Evelyn Seto from Atari’s graphics team once said: “The romance of the game was told in the box artwork.”

And what could be more intriguing than a woman in space with her spacesuit-clad dog competing against a robot with laser-powers? The illustrations on 3D Tic-Tac-Toe’s box were painted by Susan Jaekel, who became known for her illustrated textbooks and cookbooks, as well as the packaging for Atari’s Adventure, Circus, Basic Math, and others. On 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, Jaekel collaborated with Rick Guidice to create the four grids in the design; Guidice is well-known for his 1970s illustrations of space colonies for NASA’s Ames Research Center.

In 1978, Shaw also programmed Video Checkers and Super Breakout (with Nick Turner). In 1982, Shaw left Atari to work for Activision, where she created her most celebrated game: River Raid. River Raid by Carol Shaw. Activision was the first third-party video game developer, making compatible cartridges for the Atari 2600. THF171080

River Raid by Carol Shaw. Activision was the first third-party video game developer, making compatible cartridges for the Atari 2600. THF171080

River Raid is a top-down-view scrolling shooter video game. Players move a fighter jet left to right to avoid other vehicles, shoot military vehicles, and must refuel their plane to avoid crashing. The game was pioneering for its variation in background landscape. Whereas most games repeated the same background, Shaw found a way to create a self-generating algorithm to randomize the scenery.

In an interview, Carol Shaw spoke of how “Ray Kassar, President of Atari, was touring the labs and he said, ‘Oh, at last! We have a female game designer. She can do cosmetics color matching and interior decorating cartridges!’ Which are two subjects I had absolutely no interest in…” Detail of River Raid instruction manual, introduced by Carol Shaw.

Detail of River Raid instruction manual, introduced by Carol Shaw.

Carla Meninsky

In Atari’s early years, Carla Meninsky was one of only two female employees in Atari’s cartridge design division, along with Carol Shaw. When Meninsky was a teenager, her programmer mother taught her the basics of Fortran. Carla’s academic studies at Stanford began in the mathematics department, but she switched to a major in psychology with a focus in neuroscience. In school, she became interested in building an AI-powered computer animation system and spent her free time playing the text-based Adventure game. Soon after graduation, she pitched her computerized animation idea to Atari, and was hired. Almost immediately, she found herself shuttled into the unintended role of game programmer, working through a list of proposed titles with no actual description.  Carla Meninsky and Ed Riddle’s Indy 500 was one of the first of nine titles released with the Atari 2600 launch. THF171078

Carla Meninsky and Ed Riddle’s Indy 500 was one of the first of nine titles released with the Atari 2600 launch. THF171078

Meninsky co-designed Indy 500 with Ed Riddle. When the Atari 2600 launched, this was one of the first nine titles advertised. The game was a bird’s eye view racing game that was a “port” made in the spirit of full-size coin-op arcade games like Indy 800, Grand Trak 10, and Sprint 4. This game could be used with the standard controller, or a special driving controller with a rotating dial that allowed players to have greater control over their vehicles.  Dodge ‘Em is another driving maze game designed by Carla Meninsky, and was one of the first games she created for Atari. THF171079

Dodge ‘Em is another driving maze game designed by Carla Meninsky, and was one of the first games she created for Atari. THF171079 Carla Meninsky’s Star Raiders, 1982. THF171076

Carla Meninsky’s Star Raiders, 1982. THF171076

Star Raiders, also by Meninsky, is a first-person shooter game with a space combat theme. The game was groundbreaking for its advanced gameplay and quality graphics that simulated a three-dimensional field of play. The original version of the game was written by Doug Neubauer for the Atari 8-bit home computer and was inspired by his love for Star Trek. This “port” to the home console market for the Atari 2600 was programmed by Carla Meninsky.

Star Raiders came with a special Video Touch Pad controller. The Henry Ford’s collections house the version sold with the 1982 game, as well as a crushed and dirtied version that was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” in 2013. THF171077 and THF159969

Star Raiders came with a special Video Touch Pad controller. The Henry Ford’s collections house the version sold with the 1982 game, as well as a crushed and dirtied version that was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” in 2013. THF171077 and THF159969

The 2600 version of the game could be used with a regular joystick, or a deluxe version was sold with a special Video Touch Pad controller. This twelve-button touchpad was designed to be overlaid with interchangeable graphic cards, printed with commands for different Atari games. Star Raiders was the only game to make use of this controller—perhaps if it weren’t for the looming “Video Game Crash” of 1983, other developers would have made use of this controller.

Atari was one of the first companies with the types of workplace perks that are now ubiquitous at Silicon Valley companies today. It had a reputation for attracting the young, the rebellious, and the singularly talented. While certain aspects of Atari’s workplace culture might raise eyebrows today (and rightly so), it also doesn’t take much digging to find stories of women who were empowered to make vital contributions to the company. These recent artifact acquisitions—games designed and programmed by female gaming pioneers working at Atari—embody an ambition to represent and celebrate diverse cultures through our technological collections.

Kristen Gallerneaux is the Curator of Communications and Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

toys and games, California, 20th century, 1980s, 1970s, women's history, video games, technology, home life, design, by Kristen Gallerneaux