Posts Tagged video games

New Racing Acquisitions at The Henry Ford

Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors.

The Henry Ford’s newest exhibition, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, opened to the public on March 27. It’s been a thrill to see visitors experiencing and enjoying the show after so many years of planning.

Along with all of that planning, we did some serious collecting as well. Visitors to Driven to Win will see more than 250 artifacts from all eras of American racing. Several of those pieces are newly acquired, specifically for the show.

Shoes worn by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five. Block co-founded DC Shoes in 1994. / THF179739

The most obvious new addition is the 2012 Ford Fiesta driven by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five: Ultimate Urban Playground; San Francisco. The car checked some important boxes for us. It represented one of America’s hottest current motorsport stars, of course, but it also gave us our first rally car. The Fiesta wasn’t just for show—Block drove it in multiple competitions, including the 2012 X Games in Los Angeles, where he took second place (one of five podium finishes Block took in the X Games series). At the same time, we collected several accessories worn by Block, including a helmet, a racing suit, gloves, sunglasses, and a pair of shoes. The footwear is by DC Shoes, the apparel company that Block co-founded with Damon Way in 1994.

Racing toys and games are prominently represented in Driven to Win. We have several vintage slot cars and die cast models, but I was excited to add a 1:64 scale model of Brittany Force’s 2019 Top Fuel car. Force is one of NHRA’s biggest current stars, and an inspiration to a new generation of fans.

Charmingly dated today, Pole Position’s graphics and gameplay were strikingly realistic in 1983. / THF176903

Many of those newer fans have lived their racing dreams through video games. We had a copy of Atari’s pioneering Indy 500 cartridge already, but I was determined to add newer, more influential titles to our holdings. While Indy 500 didn’t share much with its namesake race apart from the general premise of cars competing on an oval track, Atari’s Pole Position brought a new degree of realism to racing video games. Pole Position was a top arcade hit in 1982, and the home version, released the following year, retained the full-color landscapes that made the game so lifelike at the time. I was excited to acquire a copy that not only included the original box, but also a hype sticker reading “Arcade Hit of the Year!”

Another game that made the jump from arcade to living room was Daytona USA, released in 1995 for the short-lived Sega Saturn. Rather than open-wheel racing, Daytona USA based its gameplay on stock car competition. The arcade version was notable for permitting up to eight machines to be linked together, allowing multiple players to compete with one another.

More recently, the Forza series set a new standard for racing video games. The initial title, Forza Motorsport, featured more than 200 cars and encouraged people to customize their vehicles to improve performance or appearance. Online connectivity allowed Forza Motorsport players to compete with others not just in the same room, but around the world.

One of my favorite new acquisitions is a photograph showing a young racer, Basil “Jug” Menard, posing with his race car. There’s something charming in the way young Menard poses with his Ford, a big smile on his face and hands at his hips like a superhero. His car looks worse for the wear, with plenty of dents and an “85” rather hastily stenciled on the door, but this young driver is clearly proud of it. Menard represents the “weekend warrior” who works a regular job during the week, but takes on the world at the local dirt track each weekend.

When we talk about a racer’s tools, we don’t just mean cars and helmets. / THF167207

Drivers may get most of the glory, but they’re only the most visible part of the large team behind any race car. There are folks working for each win everywhere from pit lane to the business office. Engineers are a crucial part of that group, whether they work for the racing team itself, the car manufacturer, or a supplier. In the early 20th century, Leo Goossen was among the most successful racing engineers in the United States. Alongside designer Harry Miller, Goossen developed cars and engines that won the Indianapolis 500 a total of 14 times from 1922 to 1938. We had the great fortune to acquire a set of drafting tools used by Goossen in his work. The donor of those tools grew up with Goossen as his neighbor. As a boy, the donor often talked about cars and racing with Goossen. The engineer passed the tools on to the boy as a gift.

We could not mount a serious exhibit on motorsport without talking about safety. Into the 1970s, auto racing was a frightfully dangerous enterprise. Legendary driver Mario Andretti commented on the risk in the early years of his career during our 2017 interview with him. Andretti recalled that during the drivers’ meeting at the beginning of each season, he’d look around the room and wonder who wouldn’t survive to the end of the year.

Improved helmets went a long way in reducing deaths and injuries. Open-face, hard-shell helmets were common on race tracks by the late 1950s, but it wasn’t until 1968 that driver Dan Gurney introduced the motocross-style full-face helmet to auto racing. Some drivers initially chided Gurney for being overly cautious—but they soon came to appreciate the protection from flying debris. Mr. Gurney kindly donated to us one of the full-face helmets he used in occasional races after his formal retirement from competitive driving in 1970.

And speaking of Dan Gurney, he famously co-drove the Ford Mark IV to victory with A.J. Foyt at Le Mans in 1967. We have a treasure trove of photographs from that race, and of course we have the Mark IV itself, but we recently added something particularly special: the trophy Ford Motor Company received for the victory. To our knowledge, Driven to Win marks the first time this trophy has been on public view in decades. Personally, I think the prize’s long absence is a key part of the story. Ford went to Le Mans to beat Ferrari. After doing so for a second time in 1967, Ford shut down its Le Mans program, having met its goal and made its point. All the racing world had marveled at those back-to-back wins—Ford didn’t need to show off a trophy to prove what it had done!

Janet Guthrie wore this glove at the 1977 Indy 500—when she became the first woman to compete in the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. / THF166385

For most of its history, professional auto racing has been dominated by white men. Women and people of color have fought discrimination and intimidation in the sport for decades. It is important to include those stories in Driven to Win—and in The Henry Ford’s collections. We documented Janet Guthrie’s groundbreaking run at the 1977 Indianapolis 500, when she became the first woman to compete in America’s most celebrated race, with a glove she wore during the event. I quite like the fact that the glove had been framed with a plaque, a gesture that underlined the significance of Guthrie’s achievement. We’ve displayed the glove in the exhibit still inside that frame. More recently, Danica Patrick followed Guthrie’s footsteps at Indy. Patrick also competed for several years in NASCAR, and in 2013 she became the first woman to earn the pole position at the Daytona 500. She kindly donated a pair of gloves that she wore in 2012, her inaugural Cup Series season.

Wendell Scott, the first Black driver to compete full-time in NASCAR’s Cup Series, as photographed at Charlotte Motor Speedway in 1974. / THF147632

Wendell Scott broke NASCAR’s color barrier when he battled discrimination from officials and fans to become the first Black driver to win a Cup Series race. Scott earned the victory at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida, in December 1963. We acquired a photo of Scott taken later in his career, at the 1972 World 600. Scott retired in 1973 after sustaining serious injuries in a crash at Talladega Superspeedway. In addition to acquiring the photo, we were fortunate to be able to borrow a 1966 Ford Galaxie driven by Scott during the 1967 and 1968 NASCAR seasons.

Wendell Scott’s impact on the sport is still felt. Current star Darrell “Bubba” Wallace is the first Black driver since Scott to race in the Cup Series full-time. Following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, Wallace joined other athletes from all sports in supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. He and his teammates at Richard Petty Motorsports created a special Black Lives Matter paint scheme for Wallace’s #43 Chevrolet Camaro, driven at Virginia’s Martinsville Speedway on June 10, 2020. We acquired a model of that car for the exhibit. The interlocked Black and white hands on the hood are a hopeful symbol at a difficult time.

Our collecting efforts did not end when Driven to Win opened. We continue to add important pieces to our holdings—most recently, items used by rising star Armani Williams in his stock car racing career. There will be more to come: more artifacts to collect, more stories to share, and more insights on the people and places that make American racing special.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 20th century, women's history, video games, toys and games, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, engineering, Driven to Win, by Matt Anderson, African American history, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

The “F” Stands for “Fun”: Jerry Lawson & the Fairchild Channel F Video Entertainment System

Jerry Lawson, circa 1980. Image from Black Enterprise magazine, December 1982 issue, provided courtesy The Strong National Museum of Play.

In 1975, two Alpex Computer Corporation employees named Wallace Kirschner and Lawrence Haskel approached Fairchild Semiconductor to sell an idea—a prototype for a video game console code-named Project “RAVEN.” Fairchild saw promise in RAVEN’s groundbreaking concept for interchangeable software, but the system was too delicate for everyday consumers.

Jerry Lawson, head of engineering and hardware at Fairchild, was assigned to bring the system up to market standards. Just one year prior, Lawson had irked Fairchild after learning that he had built a coin-op arcade version of the Demolition Derby game in his garage. His managers worried about conflict of interest and potential competition. Rather than reprimand him, they asked Lawson to research applying Fairchild technology to the budding home video game market. The timing of Kirschner and Haskel’s arrival couldn’t have been more fortuitous.

A portrait of George Washington Carver in the Greenfield Village Soybean Laboratory. Carver’s inquisitiveness and scientific interests served as childhood inspiration for Lawson. / THF214109

Jerry Lawson was born in 1940 and grew up in a Queens, New York, federal housing project. In an interview with Vintage Computing magazine, he described how his first-grade teacher put a photo of George Washington Carver next to his desk, telling Lawson “This could be you!” He was interested in electronics from a young age, earning his ham radio operator’s license, repairing neighborhood televisions, and building walkie talkies to sell.

When Lawson took classes at Queens and City College in New York, it became apparent that his self-taught knowledge was much more advanced than what he was being taught. He entered the field without completing a degree, working for several electronics companies before moving to Fairchild in 1970. In the mid-1970s, Lawson joined the Homebrew Computer Club, which allowed him to establish important Silicon Valley contacts. He was the only Black man present at those meetings and was one of the first Black engineers to work in Silicon Valley and in the video game industry.

Refining an Idea

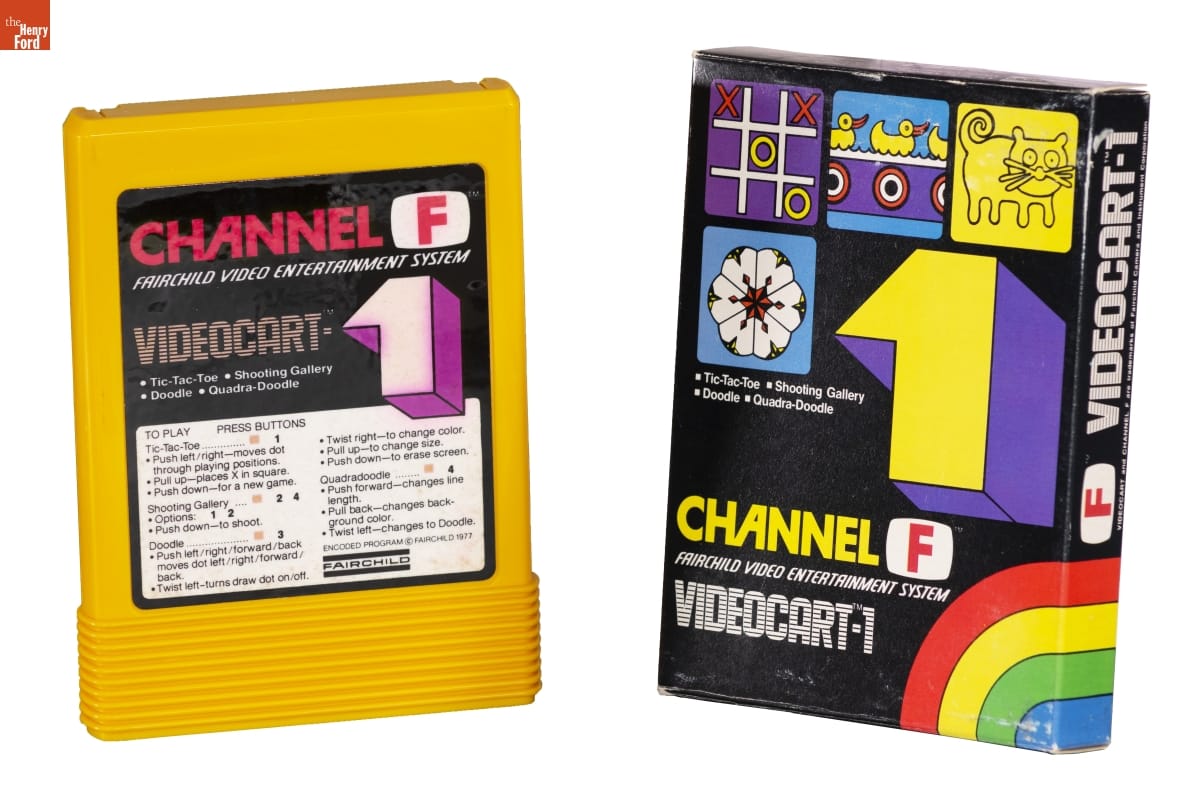

Packaging for the Fairchild Channel F Video Entertainment System. / THF185320

With Kirschner and Haskel’s input, the team at Fairchild—which grew to include Lawson, Ron Smith, and Nick Talesfore—transformed RAVEN’s basic premise into what was eventually released as the Fairchild “Channel F” Video Entertainment System. For his contributions, Lawson has earned credit for the co-invention of the programmable and interchangeable video game cartridge, which continues to be adapted into modern gaming systems. Industrial designer Nick Talesfore designed the look of cartridges, taking inspiration from 8-track tapes. A spring-loaded door kept the software safe.

A Fairchild “Video-Cart” compared to a typical 8-track tape. / THF185336 & THF323548

A Fairchild “Video-Cart” compared to a typical 8-track tape. / THF185336 & THF323548

Until the invention of the video game cartridge, home video games were built directly onto the ROM storage and soldered permanently onto the main circuit board. This meant, for example, if you purchased one of the first versions of Pong for the home, Pong was the only game playable on that system. In 1974, the Magnavox Odyssey used jumper cards that rewired the machine’s function and asked players to tape acetate overlays onto their television screen to change the game field. These were creative workarounds, but they weren’t as user-friendly as the Channel F’s “switchable software” cart system.

THF151659

Jerry Lawson also sketched the unique stick controller, which was then rendered for production by Talesfore, along with the main console, which was inspired by faux woodgrain alarm clocks. The bold graphics on the labels and boxes were illustrated by Tom Kamifuji, who created rainbow-infused graphics for a 7Up campaign in the early 1970s. Kamifuji’s graphic design, interestingly, is also credited with inspiring the rainbow version of the Apple Computers logo.

The Fairchild Video Entertainment System with unique stick controllers designed by Lawson. / THF185322

The Video Game Industry vs. Itself

The Channel F was released in 1976, but one short year later, it was in an unfortunate position. The home video game market was becoming saturated, and Fairchild found itself in competition with one of the most successful video game systems of all time—the Atari 2600. Compared to the types of action-packed games that might be found in a coin-operated arcade or the Atari 2600, many found the Channel F’s gaming content to be tame, with titles like Math Quiz and Magic Numbers. To be fair, the Channel F also included Space War, Torpedo Alley, and Drag Race, but Atari’s graphics quality outpaced Fairchild’s. Approximately 300,000 units of Channel Fun were sold by 1977, compared to several million units of the Atari 2600.

Channel F Games (see them all in our Digital Collections)

Around 1980, Lawson left Fairchild to form Videosoft (ironically, a company dedicated to producing games and software for Atari) but only one cartridge found official release: a technical tool for television repair called “Color Bar Generator.” Realizing they would never be able to compete with Atari, Fairchild stopped producing the Channel F in 1983, just in time for the “Great Video Game Crash.” While the Channel F may not be as well-known as many other gaming systems of the 1970s and 80s, what is undeniable is that Fairchild was at the forefront of a new technology—and that Jerry Lawson’s contributions are still with us today.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

1980s, 1970s, 20th century, New York, video games, toys and games, technology, making, home life, engineering, design, by Kristen Gallerneaux, African American history

Home Entertainment

Portrait of Young Girl with Hoop and Stick, 1868-1870. THF226622

The challenges posed by COVID-19 have inspired us to figure out new ways of working — and also of playing. Our entertainment is now focused on what can be enjoyed in and around our homes.

The past century saw an explosion of entertainment choices to enjoy in our leisure time, and plenty of these remain accessible to help lift spirits and put smiles on our faces. Favorite music, movies and television shows are at our fingertips. Video and board games can be enjoyed. Craft projects await. Reading material surrounds us —found online, downloaded on tablets or discovered on our own bookshelves. Weather permitting, outdoor activities like walking, riding a bicycle or even barbecuing remain accessible — all while maintaining social distancing, of course!

Right now, for many, there is little physical or mental separation between work and leisure. Taking time to savor leisure activities while remaining at home helps renew energy and focus. There are so many ways to stay engaged. Enjoy!

Perhaps the close quarters many of us are currently experiencing may even inspire more face-to-face communication, creativity — and play.

Home Media Entertainment

Sesame Street 50th Anniversary

The Real Toys of Toy Story

Is That from Star Trek?

Star Wars: A Force to Be Reckoned With

Immersit Game Movement (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Travel Television with Samantha Brown's Passport to Great Weekends"

A TV Tour of the White House" with Jacqueline Kennedy

Edison Kinetoscope with Kinetophone

Allan McGrew and Family Reading and Listening to Radio

Staying Busy with Games

Games and Puzzles

Board Games

McLoughlin Brothers: Color Printing Pioneers

Playing Cards

Girl with Hoop and Stick

Alphabet Blocks and Spelling Toys

CBS Sunday Morning with Mo Rocca: Piecing together the history of jigsaw puzzles

Crafting at Home

Leatherworking Kit

Paragon Needlecraft American Glory Quilt Kit

Carte de Visite of Woman Knitting

Video Games

History of Video Games (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Player Up: Video Game History

Unearthing the Atari Tomb: How E.T. Found a Home at The Henry Ford

Reading for Pleasure

Comic Books Under Attack

Commercializing the Comics: The Contributions of Richard Outcault

The "Peanuts" Gang: From Comic Strip to Popular Culture

It All Started with a Book: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Woman Reading a Book

John Burroughs in His Study

Staying Engaged & Family Activities

Partio Cart Used by Dwight Eisenhower

Connect 3: Guided Creativity

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Did you find this content of value? Consider making a gift to The Henry Ford.

by Jeanine Head Miller, books, video games, radio, TV, movies, making, toys and games, COVID 19 impact

Celebrating Women at Atari

The familiar silver packaging for the “Black Vader” Atari 2600 was created by Evelyn Seto, who led the Atari design team with John Hayashi. THF160364

Cardboard boxes printed in bold colors: shimmering silver, blazing orange, primary blue, circus purple—hot pink. Overlaid with white and yellow Bauhaus typography announcing the contents: Centipede, Breakout, Space Invaders. Inside the box, a black plastic cartridge that holds the promise of video game entertainment, all from the comfort of home. Games played while sitting cross-legged on the floor. Later, aching hands from hours of play on a square, non-ergonomic, one-button joystick. No quarters necessary. By the fall of 1977, there was no denying the fact that the arcade was successfully finding its way into the living room.

The Atari Video Computer System (later sold as the Atari 2600) changed the gaming industry. Earlier systems like the Magnavox Odyssey, Home PONG, and the Fairchild System F were available in the early 1970s, but the remarkable success of the Atari 2600 defined a “second generation” of home consoles, selling over 30 million units between 1977 and 1992.

The number of games available for the 2600—taking into account Atari and Sears releases as well as those by third-parties like Activision and Imagic—finds us looking at approximately 550 unique titles. Several games within this vast library include important contributions made by women.

Female employees were not uncommon at the company. Carol Kantor became the first market researcher at a video game company, ever. Wanda Hill drew the circuit diagrams for Asteroids. Judy Richter worked as a packaging designer and production manager for a decade, through multiple leadership transitions. The people working on the assembly lines populating the circuit boards for arcade games were almost all women. Evelyn Seto supervised the design team, inking the original three-pronged “Mt. Fuji” logo and creating the shelf-appealing silver packaging for the Atari 2600. Dona Bailey and Ed Logg’s 1980 arcade version of Centipede was translated as a “port” for the Atari 2600 in 1982. In 2013, this cartridge was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” located in an Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill. THF159973

Dona Bailey and Ed Logg’s 1980 arcade version of Centipede was translated as a “port” for the Atari 2600 in 1982. In 2013, this cartridge was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” located in an Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill. THF159973

The scales were not exactly balanced in terms of gender equality within Atari’s engineering staff, but take for instance the work of Dona Bailey, programmer of the arcade version of Centipede (1980). Not only was she the first female programmer to design an arcade game, but her collaboration with Ed Logg led to the creation of one of the most iconic video games of all time.

When Carol Shaw created 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, she became the first professional female video game developer. THF171081

Carol Shaw & Susan Jaekel

Dona Bailey’s time in the “coin-op” division at Atari overlapped with Carol Shaw’s work for the “cart” division. In 1977, Shaw graduated from the University of California, Berkeley’s Computer Science program, and was hired as the first female programmer at Atari in August 1978. When she completed her first cartridge game that year—3D Tic-Tac-Toe—she effectively became one of the women to work in the professional video game industry. 3D Tic-Tac-Toe is an abstract strategy video game based on a game called Qubic, which was originally played on room-sized computers in the mid-1950s.

In the 1970s and 80s, the exterior graphics of a coin-op console or the illustration on a game’s cardboard box were often a player’s first exposure to a game. Typically, the vibrant and dynamic graphics promoting a game were light years beyond the pixelated game that showed up on the screen. Nonetheless, Evelyn Seto from Atari’s graphics team once said: “The romance of the game was told in the box artwork.”

And what could be more intriguing than a woman in space with her spacesuit-clad dog competing against a robot with laser-powers? The illustrations on 3D Tic-Tac-Toe’s box were painted by Susan Jaekel, who became known for her illustrated textbooks and cookbooks, as well as the packaging for Atari’s Adventure, Circus, Basic Math, and others. On 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, Jaekel collaborated with Rick Guidice to create the four grids in the design; Guidice is well-known for his 1970s illustrations of space colonies for NASA’s Ames Research Center.

In 1978, Shaw also programmed Video Checkers and Super Breakout (with Nick Turner). In 1982, Shaw left Atari to work for Activision, where she created her most celebrated game: River Raid. River Raid by Carol Shaw. Activision was the first third-party video game developer, making compatible cartridges for the Atari 2600. THF171080

River Raid by Carol Shaw. Activision was the first third-party video game developer, making compatible cartridges for the Atari 2600. THF171080

River Raid is a top-down-view scrolling shooter video game. Players move a fighter jet left to right to avoid other vehicles, shoot military vehicles, and must refuel their plane to avoid crashing. The game was pioneering for its variation in background landscape. Whereas most games repeated the same background, Shaw found a way to create a self-generating algorithm to randomize the scenery.

In an interview, Carol Shaw spoke of how “Ray Kassar, President of Atari, was touring the labs and he said, ‘Oh, at last! We have a female game designer. She can do cosmetics color matching and interior decorating cartridges!’ Which are two subjects I had absolutely no interest in…” Detail of River Raid instruction manual, introduced by Carol Shaw.

Detail of River Raid instruction manual, introduced by Carol Shaw.

Carla Meninsky

In Atari’s early years, Carla Meninsky was one of only two female employees in Atari’s cartridge design division, along with Carol Shaw. When Meninsky was a teenager, her programmer mother taught her the basics of Fortran. Carla’s academic studies at Stanford began in the mathematics department, but she switched to a major in psychology with a focus in neuroscience. In school, she became interested in building an AI-powered computer animation system and spent her free time playing the text-based Adventure game. Soon after graduation, she pitched her computerized animation idea to Atari, and was hired. Almost immediately, she found herself shuttled into the unintended role of game programmer, working through a list of proposed titles with no actual description.  Carla Meninsky and Ed Riddle’s Indy 500 was one of the first of nine titles released with the Atari 2600 launch. THF171078

Carla Meninsky and Ed Riddle’s Indy 500 was one of the first of nine titles released with the Atari 2600 launch. THF171078

Meninsky co-designed Indy 500 with Ed Riddle. When the Atari 2600 launched, this was one of the first nine titles advertised. The game was a bird’s eye view racing game that was a “port” made in the spirit of full-size coin-op arcade games like Indy 800, Grand Trak 10, and Sprint 4. This game could be used with the standard controller, or a special driving controller with a rotating dial that allowed players to have greater control over their vehicles.  Dodge ‘Em is another driving maze game designed by Carla Meninsky, and was one of the first games she created for Atari. THF171079

Dodge ‘Em is another driving maze game designed by Carla Meninsky, and was one of the first games she created for Atari. THF171079 Carla Meninsky’s Star Raiders, 1982. THF171076

Carla Meninsky’s Star Raiders, 1982. THF171076

Star Raiders, also by Meninsky, is a first-person shooter game with a space combat theme. The game was groundbreaking for its advanced gameplay and quality graphics that simulated a three-dimensional field of play. The original version of the game was written by Doug Neubauer for the Atari 8-bit home computer and was inspired by his love for Star Trek. This “port” to the home console market for the Atari 2600 was programmed by Carla Meninsky.

Star Raiders came with a special Video Touch Pad controller. The Henry Ford’s collections house the version sold with the 1982 game, as well as a crushed and dirtied version that was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” in 2013. THF171077 and THF159969

Star Raiders came with a special Video Touch Pad controller. The Henry Ford’s collections house the version sold with the 1982 game, as well as a crushed and dirtied version that was excavated from the “Atari Tomb” in 2013. THF171077 and THF159969

The 2600 version of the game could be used with a regular joystick, or a deluxe version was sold with a special Video Touch Pad controller. This twelve-button touchpad was designed to be overlaid with interchangeable graphic cards, printed with commands for different Atari games. Star Raiders was the only game to make use of this controller—perhaps if it weren’t for the looming “Video Game Crash” of 1983, other developers would have made use of this controller.

Atari was one of the first companies with the types of workplace perks that are now ubiquitous at Silicon Valley companies today. It had a reputation for attracting the young, the rebellious, and the singularly talented. While certain aspects of Atari’s workplace culture might raise eyebrows today (and rightly so), it also doesn’t take much digging to find stories of women who were empowered to make vital contributions to the company. These recent artifact acquisitions—games designed and programmed by female gaming pioneers working at Atari—embody an ambition to represent and celebrate diverse cultures through our technological collections.

Kristen Gallerneaux is the Curator of Communications and Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

toys and games, California, 20th century, 1980s, 1970s, women's history, video games, technology, home life, design, by Kristen Gallerneaux

Archaeology's Underground

Artifacts Recovered from an Alamogordo, New Mexico Landfill, April 2014, Site of the 1983 Atari Video Game Burial - THF122265

The Strongest Sandstorm of the Year

A 30-foot-deep pit in constant danger of collapsing in on itself. Mercury-laced pig remains. Unexploded World War II ordnance. Poisonous gas. Two years ago, the threats were real in the desert landscape of Alamogordo, New Mexico, as archaeologists prepared to commence an important historical dig.

For video games. In a landfill.

In April 2014, the Atari burial ground of urban legend was excavated and artifacts exhumed to worldwide media acclaim. More important, a global conversation about what archaeology is or should be began. And a new strand of the scientific study of human history, culture and its preservation that had been somewhat underground was given newfound legitimacy.

Excavation Crew in April 2014 at the Alamogordo, New Mexico Landfill, Site of the 1983 Atari Video Game Burial - THF122241

Punk Archaeology

Known as “archaeology of the recent past,” punk archaeology is archaeology at the margins, focusing on documenting and preserving histories and cultures thought of by others as either too strange or obscure for serious study. Thriving on a DIY work ethic, volunteerism and community outreach, it bridges the gap between science and instant communication with a curious public.

This movement began in 2008 when two professors of archaeology, Bill Caraher and Kostis Kourelis, started casual conversations about how quite a few Mediterranean archaeologists they knew of also had punk rock associations or predilections. Those chats jump-started a blog, where the two started bantering online about themes shared between punk rock and their own archaeological methods. How punk rock and archaeology share an irreverence of tradition, an interest in abandoned spaces and see value in objects discarded. How they both embrace destruction as part of the creative process. How punk music has archaeological underpinnings in its songs — not in their reproduction of the past necessarily, but in their preservation of the past through brazen critique.

The blog ultimately led to the publication of the book Punk Archaeology, a manifesto of sorts about how we can use punk music as a tool to think about archaeology in different, more playful ways. But like punk, the play is serious and has, at its core, a social conscience.

As a collective study, punk archaeology realizes that as the speed of consumerism and technology continue to increase at such a rapid rate, it threatens to leave no real archaeological record. That by recording the recent past and the artifacts left behind almost as it happens, punk archaeologists can retain information for future use by scholars of culture, technology and even trash. Punk archaeology strives to give a voice to history that can be too easily ignored or forgotten by the mainstream.

The now-infamous Atari excavation marked the first official punk archaeology gig using real archaeological methods for digging, documenting and preserving artifacts less than 50 years old. I was lucky enough to lead the team on the dig, which included Caraher, Richard Rothaus (fearless field director), Raiford Guins (video game historian) and Bret Weber (sociologist).

All of us have one foot in punk history and the other foot in either classical antiquity or the American West. We were willing volunteers, happy to participate in a project that would be a first-of-its-kind technology excavation. All captivated by the weirdness surrounding the story behind it and mindful of how punk embraces the weird and does so on a shoestring.

A Tale of Trash

Urban legend had it that in 1983 video game giant Atari buried millions of copies of its notorious flop, E.T. — The Extra-Terrestrial, in a landfill in the New Mexico desert. Trucked over from Atari’s warehouse in El Paso, Texas, and dumped, the games sat among heaps of trash, subject to nightly thefts by adventurous kids who would sneak in and grab from the pile, until everything was finally driven over with heavy machinery and covered with a slurry of concrete and alternating layers of sand and garbage.

The facts and fiction of the tale had long been debated in certain circles. Some rumors claimed that Atari buried the goods to rid itself of the game thought to have singlehandedly caused the video game crash of the mid-1980s. Others said that the dump never happened. No way could a company as huge as Atari do such a thing.

Years later, online chat rooms still continued to buzz, speculating about the truth of the legendary disposal and cover-up, with some Internet conspiracy theorists claiming that perhaps as many as 5 million games had been buried, still entombed beneath a solid concrete slab.

Finally, 30 years after the supposed event, a film production company secured the rights from the city of Alamogordo to excavate the old landfill as part of the documentary Atari: Game Over on the video game crash. When I learned of this agreement, I wrote to Fuel Entertainment to see how they planned to manage the “archaeology” of the excavation. A few months later, our team was invited to participate.

We reached the Atari level 30 feet underground on April 26, 2014, to the cheers of hundreds of Alamogordo residents, gamers, pop-culture mavens, news media and even the creator of the E.T. video game, Howard Scott Warshaw. Copies of more than 40 Atari games, plus Atari 2600 consoles and controllers, were excavated, some still boxed, in shrink wrap or with price tags from Target and Wal-Mart on them.

So a legend was proven true. But what about the archaeology? And what should be done with the artifacts recovered and the stories they held?

As we examined the recovered games, we spoke to the crowd and to the media. Traditional archaeological digs and excavations rarely have public onlookers, but we welcomed the audience, sharing what we found. Punk archaeology is public archaeology. And while the Internet usually takes a passing interest in archaeological projects, typically leaving any news of discoveries to professional journals and books, this was different. The excavation of the Atari burial ground trended globally on Twitter and Facebook, prompting a public debate as to what archaeology is.

For all of us on-site in New Mexico, the excavation yielded artifacts from our recent past that had been discarded as trash — considered artifacts now because they represent a culture, a heritage for people of a certain age. They are a statement to the corporate culture and mindset of a time.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial," Recovered from Landfill, Alamogordo, New Mexico, April 26, 2014, Site of the Atari Video Game Burial of 1983- THF159970

And now, they are recognized for their significance by the likes of institutions such as The Henry Ford, the Smithsonian Institution, the Strong Museum of Play and the Vigamus video game museum, all of which accepted items recovered from the Atari burial ground as part of their collections — once again giving further legitimacy to the legend, the dig and the recovered items as important artifacts in the study of 1980s pop culture and human history.

Continue Reading

technology, toys and games, video games, The Henry Ford Magazine, by Andrew Reinhard

Report from the Field: World Maker Faire 2015

Over the weekend of September 26-27, 2015, the 6th annual World Maker Faire was hosted at the New York Hall of Science. Much like Maker Faire Detroit at The Henry Ford, New York’s Faire benefited from an added sense of shared history that comes from producing such an event on the grounds of a museum. Maker demonstrations, workshops, and displays were set up outdoors, on the former grounds of the 1964 World’s Fair—an event that was full of technological spectacle. And inside the Hall of Science, modern-day Makers found communal space alongside the museum’s interactive demonstrations about space exploration, biology, mathematics, and much more. The continuum of the importance of the technology of the past—in tandem with the anticipative futures of the Maker Movement—was substantial and exciting to witness. Continue Reading

music, technology, computers, radio, video games, events, by Kristen Gallerneaux, making

Unearthing the Atari Tomb: How E.T. Found a Home at The Henry Ford

Every year, as we plan for Maker Faire Detroit behind the scenes, The Henry Ford’s curators think about what items from their collections might be brought out for special display during the event. At this year’s Faire, a new acquisition will make its public debut—items retrieved from the infamous “Atari Tomb of 1983” in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

As any good folklorist will tell you, urban legends usually prove to be fabrications of truth that have gone awry and gained their own momentum, spread by word of mouth and media publicity. But sometimes—urban legends turn out to be true. In April 2014, excavations at the Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill unearthed every video game fan’s dream: physical evidence that the legend of the “Atari Video Game Burial” of 1983 was indeed a very real event. Continue Reading

New Mexico, video games, technology, Maker Faire Detroit, events, by Kristen Gallerneaux, 21st century, 20th century, 2010s, 1980s

As we gradually work our way through digitizing the vast collections of The Henry Ford, we tackle many projects our staff enjoy: evening gowns, mourning jewelry, and Dave Friedman auto racing photographs, for example, all pose logistical challenges, but we generally look forward to the undertaking. The less glamorous side of digitization, though, is working with objects that are potentially hazardous or unpleasant to handle, like the metal corrosion found on many of the objects we’re remediating as part of our IMLS grant, or a collection of food packaging that had to be emptied and cleaned of decades-old contents. One such project we’ve just completed is material related to the Atari Video Game Burial, in which a struggling Atari, Inc. buried hundreds of thousands of video game cartridges and gaming equipment in a New Mexico landfill in 1983. The Henry Ford’s collection contains photos and other material documenting the excavation of the landfill in 2014, as well as recovered cartridges (like E.T., shown here) and equipment—and even some of the dirt from the landfill. We can now vouch that material recovered from a landfill continues to smell like a landfill for quite some time. View our digitized Atari Burial collection (sans the unpleasant odor) on our collections website now, and watch for an upcoming blog post by Curator of Communication & Information Technology Kristen Gallerneaux to learn more about this material.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

New Mexico, video games, technology, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, 21st century, 20th century, 2010s, 1980s