In late 2015 The Henry Ford received a significant donation of studio glass from Bruce and Ann Bachmann of Chicago, Illinois. Already home to a strong historic glass collection — representing glassmaking in America from the colonial period to the mid-20th century — this new acquisition added over 300 works of glass art dating from the late 1950s to the early 2010s.

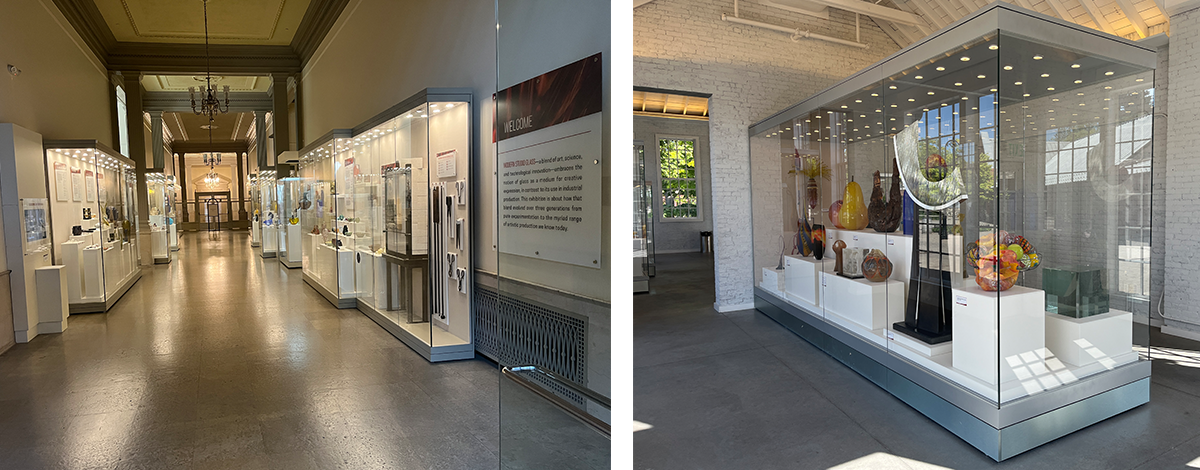

In October 2016 The Henry Ford opened the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, highlighting the story of Studio Glass movement from its beginnings through to its diffusion into contemporary society. The following summer, the Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass opened in Greenfield Village, showcasing the history of American glass from the 17th century to the present.

Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation (left), and large case of studio glass in the Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass in Greenfield Village (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

With glass in the spotlight, The Henry Ford was looking for ways to maintain the momentum. In 2017 staff from across departments developed the idea of an artist-in-residence program, bringing studio glass artists to work on-site in the Greenfield Village Glass Shop. Over the course of five days, visiting artists would collaborate with The Henry Ford's glassblowers, sharing techniques and styles while creating new, original works.

This was not exactly without precedence. Studio glass pioneer Dominick Labino worked informally in the glass shop in the 1970s, experimenting and practicing after hours. And although current staff members spends much of their time producing items for sale on-site and online, they are also artists eager to create and collaborate.

Visiting The Henry Ford during a glass event, studio glass artists and friends Laura Donefer and Leah Wingfield posed in front of their artwork on display in the museum gallery (left). Laura Donefer works with The Henry Ford’s Josh Wojick in the glass shop (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

The program has proved beneficial, both to the visiting artists and The Henry Ford. Glass shop staff and Greenfield Village visitors have been able to observe the styles and techniques of artists from all over the world. Visiting artists have had access to view the collections for inspiration, and produce multiple works during their residencies, selecting one piece to add to The Henry Ford’s collection.

The first artist-in-residence in summer 2017 was Hiroshi Yamano, a leading figure in Japanese studio glass. He is known for his innovative surface decorations and nature-inspired themes. In a memorable twist, Yamano even completed some of his signature decorative work in his hotel room to bring back to the shop to apply to the glass!

Another highlight that summer was Herb Babcock, professor emeritus in the glass program at Detroit’s Center for Creative Studies. Many glassblowers who have worked at Greenfield Village through the years were former students of Babcock.

Note the elements from nature – fish and flower – along with the applied surface decoration in this piece created by Hiroshi Yamano (left). Herb Babcock played with colors to create this vase (right). / THF180564 (left), THF180561 (right)

In 2018 four artists participated in residencies — Giles Bettison, Laura Donefer, Davide Salvadore, and David Walters, followed by three — Dean Allison, Robin Cass, and Shelley Muzylowski Allen — in 2019.

Shelly Muzylowski Allen’s “Chalcedony Bear” is a swirl of colors imitating quartz (left), and Robin Cass's “Aureate Scarlet Tenax” evokes botanical or biological specimens (right). / THF177784 (left), THF177787 (right)

In 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic forced suspension of the program for two summers.

The program resumed in 2022, but on a smaller scale, with only two residencies. That year, Ben Cobb and the husband-and-wife team Michael Schunke and Josie Gluck brought their talents to the glass shop. Jen Elek and Kelly O’Dell followed in 2023. In the summer of 2024 James Mongrain created a Venetian-inspired vessel topped with a seahorse, and Jack Gramann used the human portrait as a motif in his work.

“65 Million Years” by Kelly O’Dell, 2023 (left), Ben Cobb’s “Maple Spinner” from 2022 (center), and Jack Gramann’s “Human Face” from 2024 (right). / THF370839 (left), THF370282 (center), THF802223 (right)

In May 2025 The Henry Ford finally welcomed Nick Mount, a veteran glass artist from Adelaide, Australia. Originally scheduled for 2020, his residency was delayed due to the pandemic. A leader in Australia’s Studio Glass movement since the 1970s, Mount was first inspired by American artist Richard Marquis, who introduced Venetian glass techniques at art schools in Australia. Inspired to pursue glass, Mount toured Australia with Marquis, demonstrating blown glass. With funding from the Crafts Board of the Australia Council, he was able to study glass in the United States and Europe.

In 2022 a case was added to the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery to display a selection of artist-in-residence pieces, along with an interactive video to “meet the artists” (left), while in 2024 additional artist-in-residence pieces were selected to be displayed in the wall case in the Greenfield Village glass shop (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

After returning to Australia, Mount has balanced creating functional glass objects for retail with creative artworks that have found their way into private collections and museums around the world. For over 50 years Mount has made significant contributions to the art form through both his work and teaching.

Images of Nick Mount working in the Greenfield Village Glass Shop in May 2025. / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

As part of the artist-in-residence program, The Henry Ford’s Media Relations and Studio Productions team film the artists at work and conduct one-on-one interviews to preserve their stories and work and document their thoughts on artistic practice.

Within the Bachmann donation there was already one piece made by Nick Mount in The Henry Ford’s collection, Scent Bottle #101200, made in 2000 (left). Nick Mount’s in-process artwork for THF’s collection (right). / THF803684 (left), photo by Staff of The Henry Ford (right)

Boyd Sugiki (left) and Lisa Zerkowitz (right). / Image courtesy of Two Tone Studios

In July 2025, the owners of Two Tone Studios in Seattle, Washington — Boyd Sugiki and Liza Zerkowitz were in residence July 28~August 1, 2025. Raised in Hawaii, Boyd Sugiki earned his BFA in glass at the California College of Arts and Crafts. Lisa Zerkowitz, a California native, received her BA in Studio Art from the University of California at Santa Barbara. In 1995 while pursuing MFAs at the Rhode Island School of Design, the two began blowing glass together. They founded Two Tone Studios in 2007 and have taught at universities across the U.S. and internationally. Like Nick Mount, their original residency was postponed from 2020.

The artist-in-residence program strongly aligns with The Henry Ford’s mission to provide “unique educational experiences based on authentic objects, stories, and lives from America's traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation.” There are even thoughts about expanding the program to other areas of Liberty Craftworks — weaving, pottery, and printmaking. Stay tuned!

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The Early History of Hip-Hop in Three Flyers

New York City was experiencing a time of turmoil from the late 1960s through the 1970s. The city, especially in the outer boroughs, was in depth of recession; urban renewal policies had harmed predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Youth gangs took to the street as the result of a lack of community resources, jobs, or third spaces for leisure. Out of this chaos, hip-hop rose from the Bronx. Young people created this culture at block parties, parks, and clubs. These gatherings were usually advertised with homemade street art-inspired flyers like the ones recently acquired by The Henry Ford. They offer a glimpse into the history of not just a musical genre but a movement.

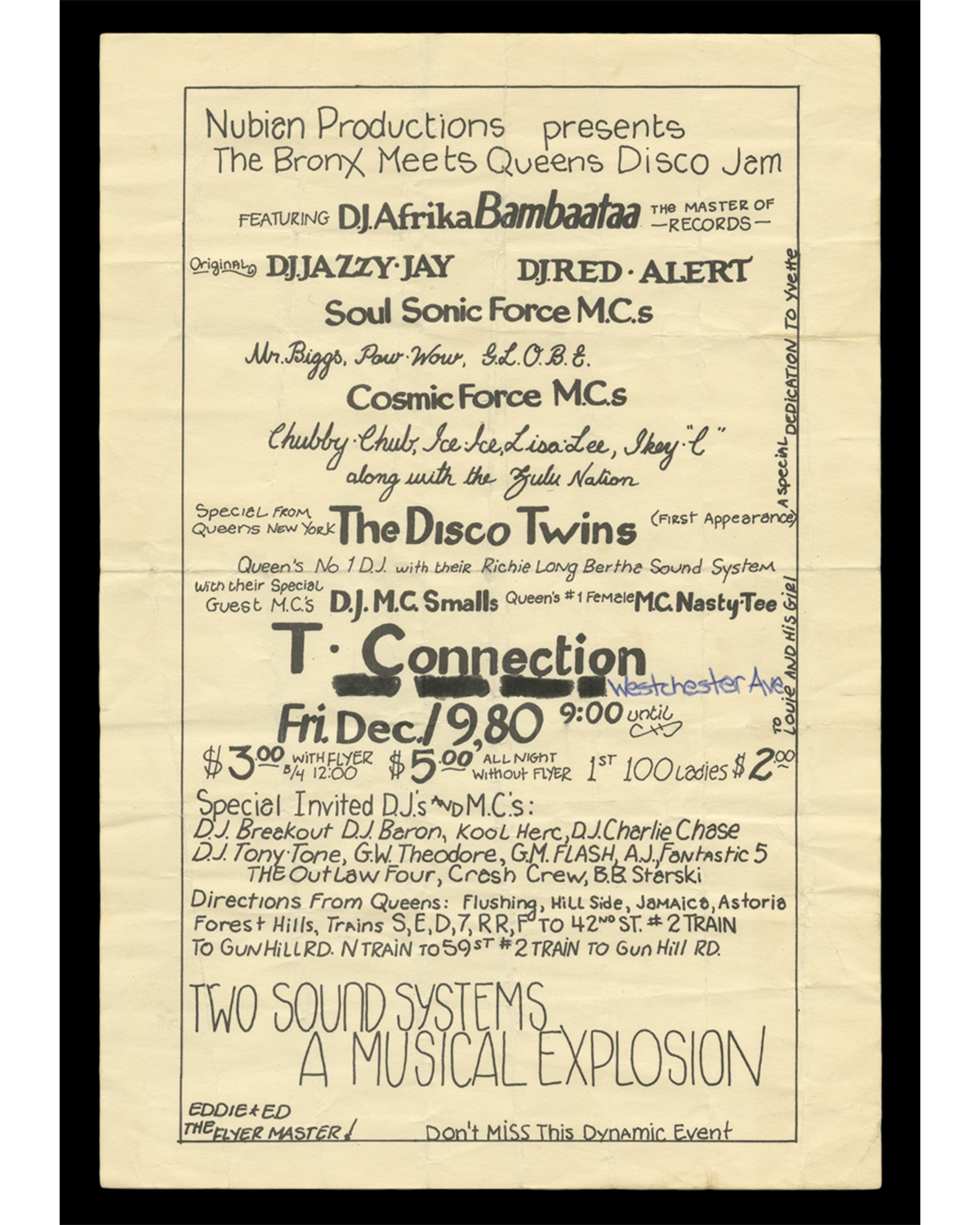

"The Bronx Meets Queens Disco Jam Featuring DJ Afrika Bambaataa," 1980. / THF721980

"The Bronx Meets Queens Disco Jam Featuring DJ Afrika Bambaataa," 1980. / THF721980

In the early days of hip-hop, the disk jockey, or DJ, was the star of the show; their ability to create the atmosphere for a party is what made them, and hip-hop itself, unique. As hip-hop grew in popularity, DJs who were fixtures at neighborhood gatherings were invited to play in clubs for special nights. Among the most prominent of these clubs was a discotheque in the Williamsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx called T-Connection. DJ Flame, who performed as DJ La Spank in the 1980s, called the T-Connection the Apollo Theater of hip-hop in a 2023 interview. To her, T-Connection was a training ground for young DJs to hone their craft in front of audiences who expected greatness. T-Connection also featured hip-hop luminaries. DJ Kool Herc, who is considered one of the founders of hip-hop, often played there with his emcees, the Herculoids. DJ Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation were considered the unofficial in-house crew of T-Connection due to their frequent performances.

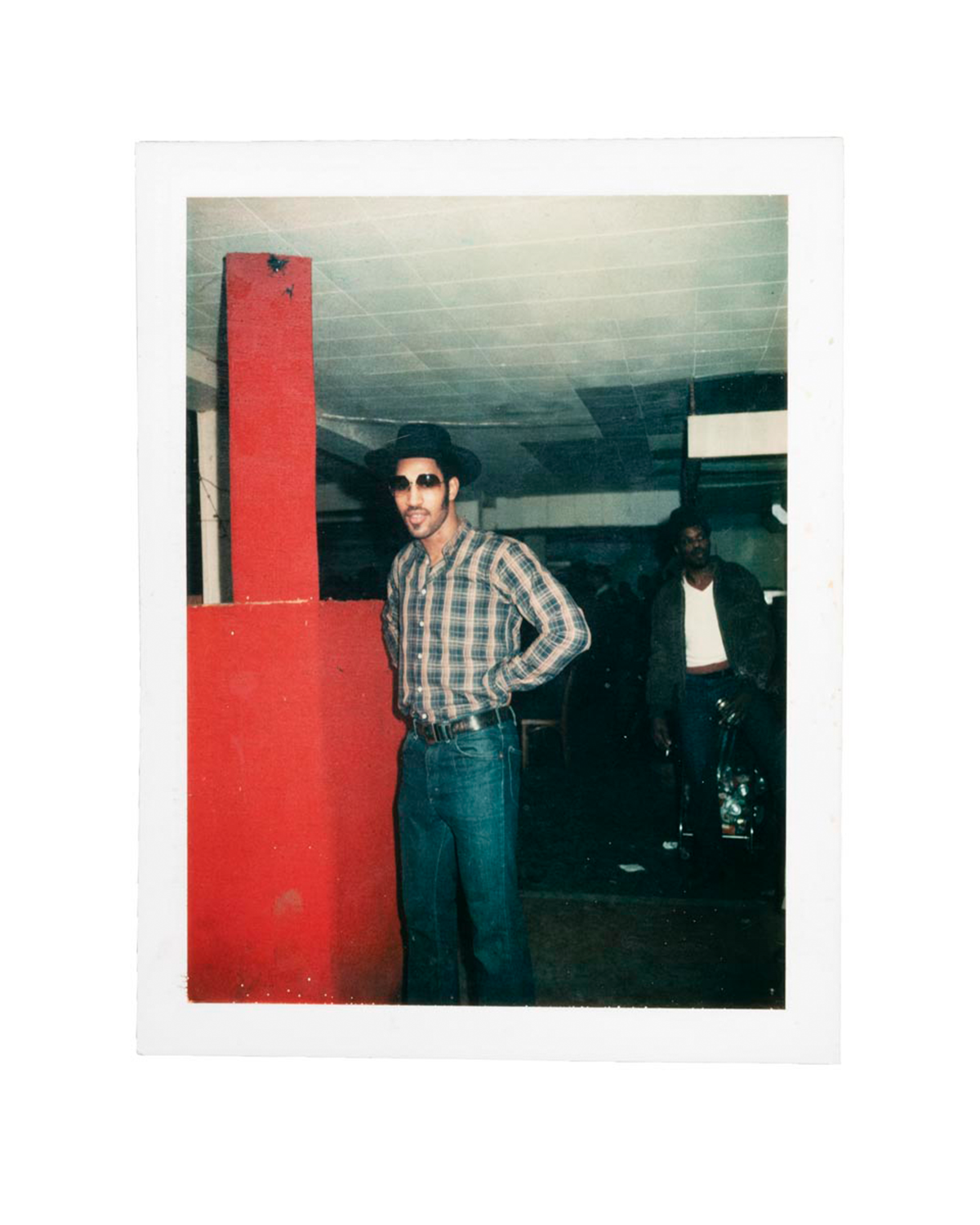

DJ Kool Herc at a nightclub, Bronx, New York, circa 1981. He is pictured in a nightclub, possibly T-Connection. / THF191960

DJ Kool Herc at a nightclub, Bronx, New York, circa 1981. He is pictured in a nightclub, possibly T-Connection. / THF191960

To be the center of a party, DJs cultivated large and mostly secretive libraries of vinyl records spanning soul, funk, disco, electronic, and rock music genres. Early hip-hop DJs focused on the breakdown or "breaks," the portions of a song where the percussion or rhythm sections of a band would do a solo. This was considered by many to be the most danceable part of a song. Some DJs, like Kool Herc or Grandmaster Flash, would extend the "breaks" in songs using two copies of the same records and playing them in succession, sometimes called the "merry-go-round" technique. You can hear the T-Connection audience’s response to DJs' hard work in surviving bootleg recordings of performances. At clubs like T-Connection, DJs demonstrated their prowess on the turntables and spread hip-hop across New York City and the world.

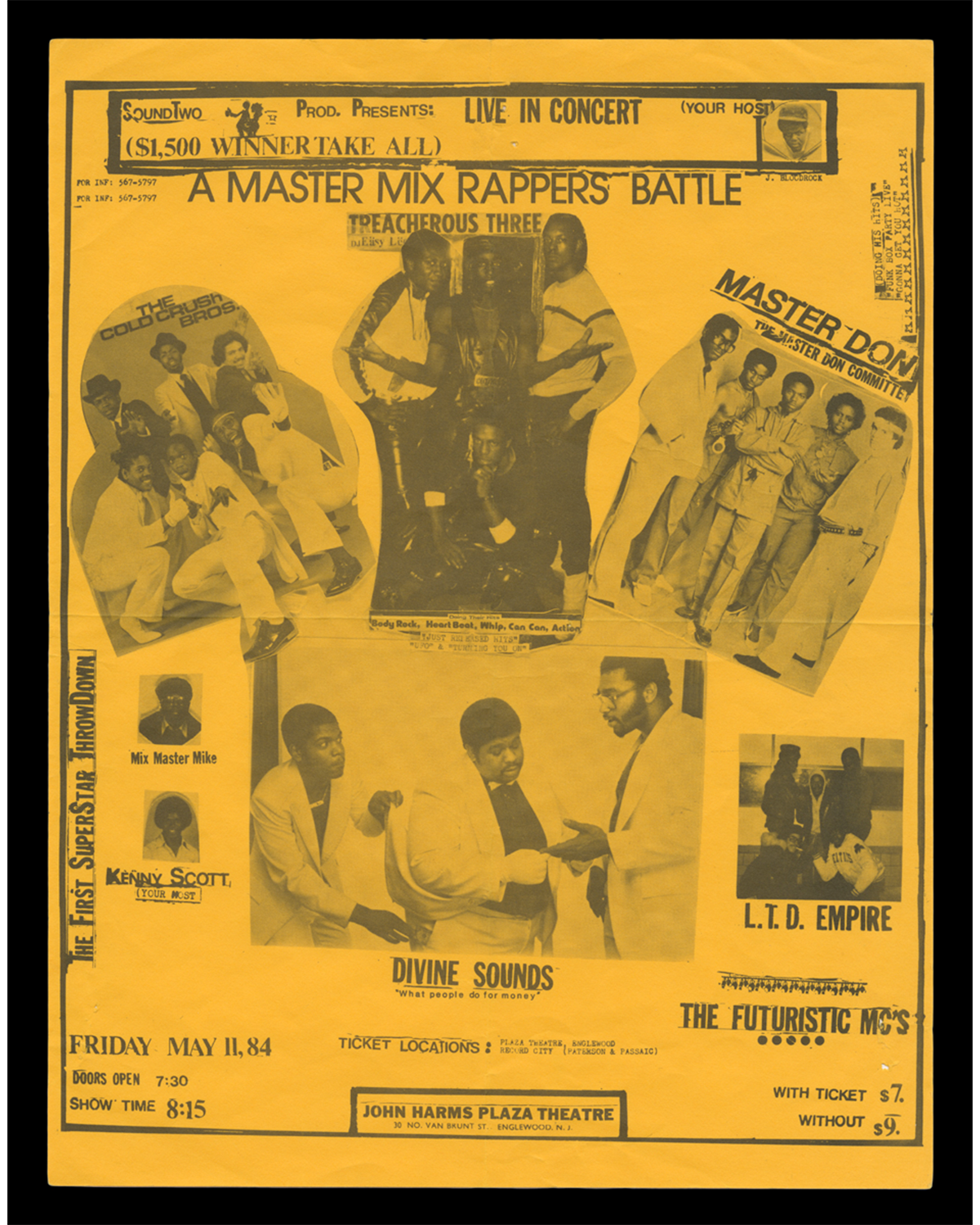

"A Master Mix Rappers Battle," 1984. / THF721983

"A Master Mix Rappers Battle," 1984. / THF721983

These early emcees were masters of ceremony at parties; they would rhyme over a few bars of music to hype up a crowd or tell someone that their car was double parked. This is why many early rappers included the moniker "MC" in their names. From this came a culture of braggadocious and sometimes insulting raps pointed at rival emcees who played at the same events or venues: battle rapping. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, rap battles, like "Master Mix Rappers Battle," were promoted to draw crowds to clubs. The crowds' response — applause, cheers, jeers, and boos — determined the winners of these battles. Some of the top-billed emcees who participated in the "Master Mix Rappers Battle" were or would soon become famous. The Cold Crush Brothers were already legendary by 1984. The crew battled the Grand Wizzard Theodore and the Fantastic Five at Harlem World in 1981. This performance is considered one of the first important rap battles in hip-hop history. Bootleg recordings of the battle were distributed among young hip-hop enthusiasts and inspired aspiring emcees such as Darryl McDaniels, DMC of Run DMC. In 1982, the Cold Crush Brothers re-created the Harlem World battle for the big screen in a film called Wild Style.

What is now called rapping has deep roots in Black American culture and in other parts of the African diaspora. Everyone from jazz band leader Cab Calloway to the poetry collective The Last Poets spoke rhythmically over music in styles similar to hip-hop emcees. Caribbean "toasting" songs were also foundational to rapping; in "toasting," Jamaican DJs spoke in a sing-song tone over the records that they played at parties or on the radio. Traditions like these influenced DJs, including Kool Herc, to bring their friends, e.g. Coke la Rock and Clark Kent, to join them and rap while the DJ played music.

Members of the Treacherous Three influenced the changing sound of hip-hop over the next decade. Emcees Kool Moe Dee and Spoonie Gee were forefathers of the subgenres New Jack Swing and Gangsta Rap, which both grew in popularity during the late 1980s and early 1990s.Master Don and the Committee — sometimes billed as Masterdon Committee or Death Committee — did not achieve the same level of fame as their competitors. After scoring a New York City radio hit with their song "Funkbox Party" in 1983, their success remained mostly localized. However, they were innovators as one of the first mixed-gender rap crews with the inclusion of DJ Master Don's sister, Pebblee Poo.

"A Birthday Party for the Lovin' Trouble," 1983. / THF721984

"A Birthday Party for the Lovin' Trouble," 1983. / THF721984

Hip-hop is not just a music genre; fashion has been baked into the culture since the beginning. There are many examples of the symbiotic relationship between hip-hop and style. Artists have started fashion labels like Roc-a-Wear, and emcees often call out their favorite brands in their lyrics like in "My Adidas" by Run DMC.

Early in hip-hop's development, there seemed to be a divide in the culture about how to dress. On the one hand, the young working-class Black and Puerto Rican audience would wear street styles from brands that they had already in their closet, like Kangol or PRO-Keds. They might add personalized touches to their outfits such as permanently creasing their jeans. If they were a dancing b-boy or b-girl, they might rep their dance crew by wearing uniform clothes.

PRO-Ked "69ers" Shoes, Worn by DJ Kool Herc, circa 1980. In hip-hop's early days, PRO-Ked basketball shoes were the sneakers of choice for DJs, emcees, and audiences alike. PRO-Ked shoes were so common among Black and Hispanic youths in the Bronx that the shoes were nicknamed “Uptowners,” referring to the borough’s location./ THF191954

PRO-Ked "69ers" Shoes, Worn by DJ Kool Herc, circa 1980. In hip-hop's early days, PRO-Ked basketball shoes were the sneakers of choice for DJs, emcees, and audiences alike. PRO-Ked shoes were so common among Black and Hispanic youths in the Bronx that the shoes were nicknamed “Uptowners,” referring to the borough’s location./ THF191954

On the other hand, there was the influence of discotheque culture. In the disco clubs, it was common for people to dress in their finest and most eye-catching apparel. For those who bridged the disco and hip-hop worlds, the glamorous get-ups were more appealing. DJ Hollywood — one of the first people to rap rhythmically over music and influence early emcees — enforced a strict dress code wherever he performed. At a DJ Hollywood party, streetwear and sneakers were strictly prohibited.

Women's "Lombada Hi Bright" Pumps, 1980-1990. Low-heeled shoes like these were popular from the 1970s until the 1990s as nightclub culture developed. The lower center of gravity made the shoes easier to dance in. They exemplify what a fashionable partygoer might wear. / THF65284

Women's "Lombada Hi Bright" Pumps, 1980-1990. Low-heeled shoes like these were popular from the 1970s until the 1990s as nightclub culture developed. The lower center of gravity made the shoes easier to dance in. They exemplify what a fashionable partygoer might wear. / THF65284

During the 1980s, many emcees and DJs embraced luxury fashion as they gained fame. For example, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five performed in elaborate leather outfits, purported to cost over $1,000 each. One fashion pioneer, Harlem-based Daniel "Dapper Dan" Day, noticed this trend and opened his boutique Dapper Dan of Harlem in 1982. He designed custom clothes made of leftover materials from haute couture brands like Louis Vuitton. Dapper Dan blended street fashion and high fashion; he prominently displayed brand name logos on his clothing and innovated the concept of "logomania" in fashion.

These three flyers represent just some of the many stories that transformed hip-hop into the cultural phenomenon it is today. If you are interested in seeing more party and event flyers from this era of hip-hop, check out Cornell University Library's hip-hop collection.

Kayla Chenault is the Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Enriching Our World

The Henry Ford is more than just a tourist attraction, more than just an institution, and more than just a summer stroll. Rather, it is a reflection — a curtain, even — for the horizons of a greener future that are closer at hand than many realize. It may feel a bit tawdry to some to personalize the planet, but it is an indisputable fact that the Earth does a lot for us that we do not recognize often enough. And just as a body must be well kept or a machine well maintained, so too should we endeavor to do our part in rejuvenating the groundsand gardens of The Henry Ford that have so delighted guests and employees.

To fuel this effort, in 2024 The Henry Ford made one of its biggest leaps forward into the frontier of sustainability with a new addition to help the management of Stand 44’s restaurant waste. The CX5 Harp Renewables Bio-Digester is a specialized piece of equipment that creates and manages a meticulously designed internal environment, aimed to yield the most efficient breakdown of food waste and biodegradable material into a soil supplement rich in essential plant nutrients. While it sounds interesting enough on its own, the logistical details are equally compelling, and the journey for a handful of food waste from when it’s disposed of to its reintroduction to the soil takes time and teamwork. It passes through many processes before it ends up in a regenerative garden, including:

Phase 1 – Collection

Waste that is disposed of by staff and guests is collected and then sorted by hand to prevent contamination. This is where guests and staff make the biggest impact to ensure the efficient and sustainable operation of the biodigester. Meanwhile the food service team continues to phase out single-use plastics in favor of biodegradable packaging. Conscientiously disposing of personal waste contributes more than many may realize.

Stand 44’s waste composting method, which makes use of an industrial biodigester, was a key element of the venue's 4-star GRA certification. / Image by The Henry Ford

Phase 2 – Feed the Machine

Believe it or not, the biodigester is a picky eater. It prefers a healthy mix of waste: dry (biodegradable utensils, plates, bones, breads etc.) and wet (vegetables, fruits, dairy products, grounds, plant scraps, etc.). A carefully considered recipe is constantly being improved upon by food service operation to ensure the most effective operation and high-quality output possible. With the careful manipulation of moisture, heat, and bacteria, this chemistry trifecta of natural digestion taken to its technical limit can break organic waste down into an odorless pathogen-free and high-nutrient soil amendment in as little as 24 hours.

Stand 44's Bio Digester during installation. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Stand 44’s Biodigester Interior. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Phase 3 – Addition

As an extra layer of complexity and to seize an even grander opportunity for sustainability, The Henry Ford is committed to treating the end product digestate from the biodigester as just one of the key ingredients in a much larger upcoming campus-wide hot composting initiative that endeavors to turn all of The Henry Ford’s yard and animal waste into fertilizer on-site.

Digestate Aggregate Pile. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Phase 4 – Return

The resulting material after the completion of the compost cycle is regularly tested to maintain state and federal safety standards. After which comes redistribution to various gardens and fields, where it can be mixed and tilled as needed for the future. Ideally, if all goes well, this compost can help in the on-site production of fruits and vegetables to be used by food services.

Experimental compost pile. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

It takes many hands not only to complete this upcycling circle, but also to support The Henry Ford’s mission to promote a more sustainable approach to its commitment to providing unique educational experiences so that we may have a better future.

Successful Compost Testing on Trailing Pink Coleus. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Aias Danier is Assistant Construction Manager at The Henry Ford. Alec Jerome is Director of Facilities Management.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation that forever changed the lives of many people of color in the United States and set the course for other groups to pursue their full rights as citizens. Yet, despite the successful legislation, many Black people and other people of color across the United States, particularly in the South, continued to be denied the right to vote.

“Do All Americans Have the Right to Vote?” An address by Barry Bingham, April 9, 1939. / THF289023

Do all Americans have the right to vote?

This question has been a concern for decades, particularly before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The 15th Amendment prohibits voting discrimination based on race, yet barriers still existed at that time that limit access to voting. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses made it all but impossible for many groups of people to exercise the rights granted to them in the 15th Amendment — rights that were repeatedly violated.

Grassroots organizing had begun in many areas in the South, and Selma, Alabama, became the center of the movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) worked to register people to vote there for months in 1965. Their work did not go unnoticed. Soon, major players in the movement, such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, were making their way to Selma. The fight for voting rights eventually led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Local groups in the Selma area were also doing the hard work. Members of the Dallas County Voters League, known as the Courageous Eight, worked to register people to vote in Dallas County, Alabama. Though they were told multiple times to cease their activities, they did not. These community leaders were committed to securing the vote for themselves and their community.

The figures of the voting rights movement go beyond the names you may already know. Nationally recognizable figures depended on local activists—everyday people who put their lives and livelihoods on the line. One such family, the Jacksons of Selma, rose to the occasion by opening their home to provide shelter, nourishment, and peace, all while putting their personal safety at risk. Their sacrifice helped to create a safe space for the movement’s leaders to strategize and rest.

Pajamas worn by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. while at the Jackson’s Home. / THF802666

Mrs. Richie Sherrod Jean Jackson took pride in ensuring that her guests felt comfortable and welcomed. Dr. Jackson provided Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with pajamas, and Mrs. Jackson fueled the movement with nourishment. The Jackson’s young daughter, Jawana, would listen to the stories her Uncle Martin would tell. But the family did more than provide a haven. They became involved civically as well.

In November 1958, Dr. Sullivan Jackson testified before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Established as part of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the commission investigated voter discrimination. The hearings were held over a period of two months, between 1958 and 1959. The Commission had several people testify, including Dr. Jackson, who spent hours preparing for his testimony. The Commission assumed the responsibility of voter registration, with a focus on Alabama. Speaking out had its own set of hardships. The Jacksons and others who testified often faced economic repercussions.

“Life” Magazine, March 19, 1965. / THF715919

Voting is a fundamental right. In the United States, this concept has been ignored more than once. The denial of voting rights to people of color across the country came into sharp focus in March of 1965 in Selma, Alabama. After March 7, 1965—known as Bloody Sunday—Dr. King called for clergy members to go to Selma. Clergy, including Rabbi Abraham Heschel and Rev. James Reeb, among many others, answered the call. On March 15, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed the nation and instructed Congress to introduce and pass a Voting Rights Act.

Two days after President Johnson gave his “American Promise” speech, on March 17, 1965, the Voting Rights Act was introduced into Congress. The Senate began its debate on the bill on April 22. Eventually, the Voting Rights Act was passed after much debate, and President Johnson signed it on August 6, 1965. Thus, it enshrined the enforcement of the 15th Amendment and ensured that no one was denied the right to vote.

Letter from Rev. Ralph Abernathy thanking her for opening her home to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. / THF721760

While the Jackson House remained a family home at its core, it also offered refuge and peace during a time of great turmoil. While in Selma, Dr. King stayed with the Jacksons. Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a member of the leadership team for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, sent Mrs. Jackson reimbursement and letters of gratitude. The Jacksons provided crucial hospitality and support, even if it meant putting their own lives at risk.

As we celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, it is essential to remember all those who were involved in the process.

Are you registered to vote? To find out if you are registered or to register, please visit the following websites:

Michigan Residents

To Check Your State

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford.

Thunderbird Soars at Motor Muster

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Once again Father’s Day weekend brought a favorite event to Greenfield Village. Our 2025 Motor Muster, held June 14-15 and celebrating car culture from 1933 to 1978, featured more than 650 automobiles, trucks, motorcycles, military vehicles, and bicycles. Each Motor Muster features a special theme, and this time our spotlight fell on the Ford Thunderbird, seventy years after the sporty personal car was introduced for the 1955 model year. Thunderbird was a hit over eleven different styling generations through 2005, taking only a brief pause in production from 1998 to 2001.

Detroit Central Market housed Thunderbirds from seven of the car’s eleven styling generations, including a couple of post-1978 examples. / Image by Matt Anderson

We wanted to showcase Thunderbird properly, so our friends at the Water Wonderland Thunderbird Club and the Vintage Thunderbird Club International helped us pull together a selection of some of the best T-Birds pull together a display in Detroit Central Market featuring some of the best T-Birds ever built Detroit Central Market. We had cars from seven of Thunderbird’s eleven generations. Together, they represented the original two-seat “Little Birds” of the mid-1950s, the four-seat “Square Birds” of the late 1950s, the angular “Bullet Birds” of the early 1960s, and the larger luxury-focused Thunderbirds of the early 1970s. From The Henry Ford’s own collection, we included our 2002 Ford Thunderbird, serial number one from the final generation, and our 1962 Budd XT-Bird, which Budd pitched to Ford in hopes of reviving the partnership that had Budd building body components for two-seat T-Birds several years earlier. Our 2002 model wasn’t the only post-1978 T-Bird in the show. We also included a 1994 Thunderbird representing the model’s tenth generation.

Thunderbird Jr. kiddie cars were built in cooperation with Ford from 1955 to 1967. / Image by Matt Anderson

There was another big—make that small— feature in Detroit Central Market. Fourteen Thunderbird Jr. cars added to the fun. Built in Mystic, Connecticut, with the blessing of Ford Motor Company, the Thunderbird Jr. was a scaled-down version of the real thing powered either by an electric motor or a single-cylinder gasoline engine. The junior cars were updated each year to match the look of the real T-Bird, and paint colors were all factory-correct. Smaller Thunderbird Jr. cars, roughly one-quarter size, were intended for children and either given away by Ford dealers or sold by high-end retailers like FAO Schwarz. Larger versions, about one-third size, were used at carnivals and amusement parks. About 5,000 Thunderbird Jr. cars were produced from 1955 to 1967. The fourteen examples at Motor Muster may have been the largest gathering of these little cars since the factory closed nearly sixty years ago.

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

From the Armington & Sims Machine Shop to the Daggett Farmhouse, Greenfield Village was packed with historic vehicles. A visitor might easily spend all day walking around to see everything. But for those who preferred to let the show come to them, we offered pass-in-review programs throughout the weekend. As spectators relaxed on shaded bleachers, expert narrators offered insights and expertise on participating vehicles that rolled through in a steady chronological parade. While most of these presentations were organized by decade, we had special sessions devoted to commercial vehicles, race cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and —of course— Thunderbirds.

The cars were complemented by a variety of musical performances and historical vignettes. At Town Hall in the heart of the village, the Village Cruisers offered a selection of 1950s vocal pop perfect for the chrome-and-tailfins era. At the same location, Larry Callahan and the Selected of God Quartet sang stirring freedom songs from the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Their performance offered a wonderful preview of programming to come with the opening of the Jackson Home next year. The 1970s came alive through the Mach I band as they played classic rock hits both at the gazebo near Ackley Covered Bridge and in a larger Saturday evening concert on Main Street.

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pedal-powered transportation is in vogue at The Henry Ford thanks to Bicycles: Powering Possibilities, a temporary exhibit now on view in the Collections Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. There were many bikes to enjoy at Motor Muster, from an eccentric-hub Ingo-Bike like this one in the museum’s collection, to an early 1970s Schwinn Twinn tandem that allowed two cyclists to ride together. And just as Motor Muster vehicles need not be motorized, they don't have to travel on land either. We celebrated outboard boating’s golden age on the shores of Suwanee Lagoon. The fascinating display of boats and engines was titled “Tailfins and Two-Tones,” reflecting a couple of 1950s design fads that were found on land and sea alike.

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

As is tradition, Motor Muster ended on Sunday with our awards ceremony. We presented trophies to vehicles from each decade based on popular-choice ballots submitted by show participants and visitors. We also gave Curator’s Choice prizes to a pair of unrestored vehicles. This year’s unrestored winners included, fittingly, a 1966 Ford Thunderbird and a 1974 Ford Gran Torino. The full list of 2025 Motor Muster winners is available here. The ceremony put a perfect cap on another wonderful weekend.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

On November 8, 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered electromagnetic radiation, or invisible light, which he dubbed x-rays; immediately they became a huge fad, used for everything from photographic filters to miracle cures for a variety of ailments. X-rays bridged the gap between the public's interest in scientific advancement and commerce. One fascinating artifact in The Henry Ford's collection demonstrates the X-ray craze well: a shoe-fitting fluoroscope.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. X-Ray Shoe Fitters, Inc., a subsidiary of the Adrian Company of Madison, Wisconsin, was one of largest manufacturers of shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and made this X-ray. / THF803832

Fluoroscopes are real-time, continuously moving X-ray images — like an X-ray movie. Thomas Edison created the first commercially available fluoroscope in 1896 by adapting the basic principle of static X-rays.

Illustration from Scientific American announcing Edison's fluoroscope in April 1896. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

X-rays are beams of invisible light moving in short wavelengths, which pass through objects and create negative images of them on a fluorescent screen. What you see in the negative image depends on how much radiation an object can absorb. More dense objects like bones absorb more radiation, so they show up as white on an X-ray picture; less dense objects like muscle tissue absorb less radiation, so they show up as dark on an X-ray picture. Edison's fluoroscope allowed people to look at their bones in real-time when they placed their bodies between a cathode tube that made X-rays and a fluorescent screen that displayed the images created.

Box of fluoroscope Slides, 1895-1905. / THF157985

In the early days of fluoroscopy, they were primarily used in hospitals or as novelties. In 1919, Jacob Lowe, owner of a Boston-based X-ray laboratory, filed a patent for the first fluoroscope explicitly for fitting shoes. Lowe saw the problem of ill-fitted shoes causing discomfort in the short term and foot deformities in the long term; his machine would allow the customers to see their feet inside of their shoes and would presumably prevent future issues.

Shoe-fitting fluoroscope, circa 1936. To use a shoe-fitting fluoroscope, customers would stand on this side of the X-ray and put their feet in the chamber at the bottom. / THF803822

To use Lowe's fluoroscope, customers placed their feet on the enclosed platform where the X-ray tube was and looked through one of the fluoroscope's viewfinders to check their feet on the fluorescent screen. The three viewfinders also allowed simultaneous observation: for example, a salesperson, a child trying on shoes, and the child's parent.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. A customer could see a fluoroscope of their feet from the viewing chamber above. / THF803831

The patent was granted in 1927, and Lowe assigned the patent to the Adrian Company in Madison, Wisconsin, which began manufacturing shoe-fitting fluoroscopes in 1922. For the next thirty years, shoe-fitting X-rays became ubiquitous in shoe stores across the world.

Did X-raying feet actually help customers and store employees fit shoes? In the 1990s, a former shoe shop clerk was interviewed about shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and revealed that the machines did not help him properly size customers. Additionally, he did not know any salespeople who felt the machine truly helped them. Shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were essentially a marketing gimmick that incentivized customers to buy shoes.

During the 1920s, businesses began to focus on ways to drive consumer habits through driving demand. For example, Charles Kettering of General Motors championed the idea of selling "newness" to customers in his 1929 essay "Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied": "If everyone were satisfied, no one would buy the new thing because no one would want it […] You must accept this reasonable dissatisfaction with what you have and buy the new thing, or accept hard times." Kettering's philosophy was pivotal to understanding why fluoroscopes were popular among shoe sellers. Even the Adrian Company's shoe fitting X-ray manual touted the unverified statistic that 75% of people wore shoes too small for them and therefore needed new shoes. That statistic could be repeated to customers to bolster dissatisfaction and drive sales. Additionally, there was a perception that using fluoroscopes was a necessary form of consumer safety. The "see for yourself" nature of the fluoroscope created the illusion of an "objective" way for salespeople to determine if new shoes were necessary.

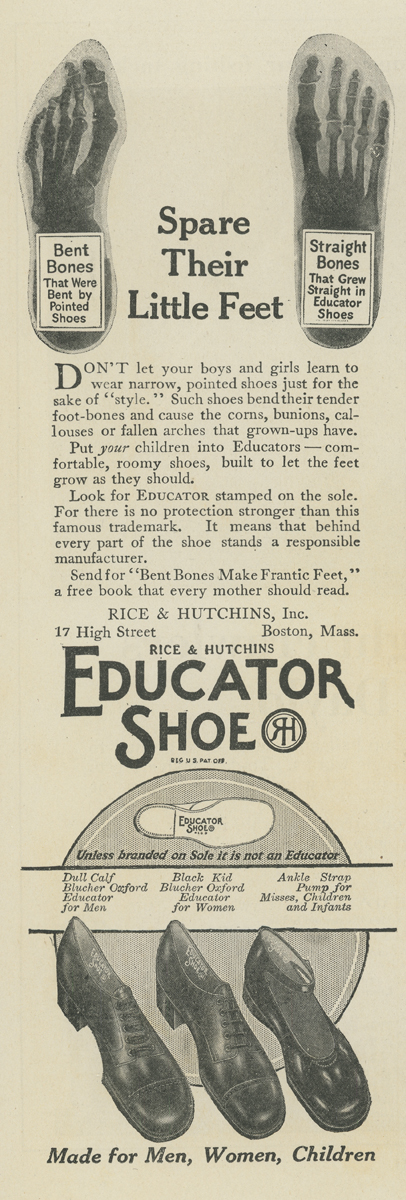

"Spare Their Little Feet," 1917-1921. / THF723224

The fluoroscopic sales tactic was used on women especially by playing into the idea of "scientific motherhood." At the beginning of the 20th century, there was an increasing expectation that women needed the latest technological advancements and advice to raise their families correctly. The concept of "scientific motherhood" was utilized to great effect in advertising, where companies marketed their products with sometimes-dubious claims of "expert approval" or "rigorous scientific testing."

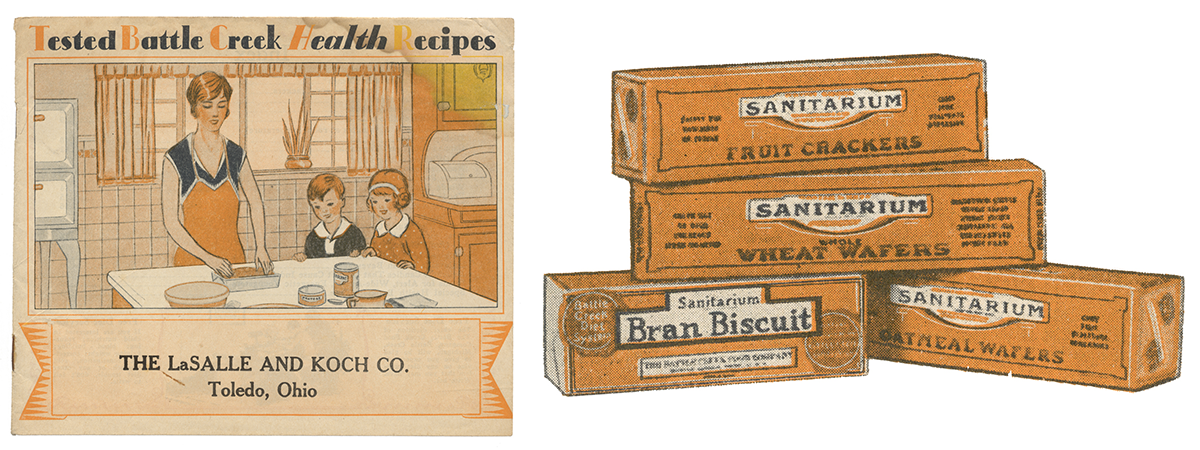

Tested Battle Creek Health Recipes, 1928. This recipe booklet is a great example of scientific motherhood in advertising. The booklet was sold along with crackers and cookies but used words like "health," "sanitarium," and "tested" to imply that the food was healthy for families like the one shown on the cover. / THF17004 and THF17005

With the fluoroscope, shoe store owners played into the medicalization of mothering. Salespeople often recommended annual or even quarterly foot X-rays for children in the way doctors might recommend yearly physicals. Repeat X-rays created repeat customers.

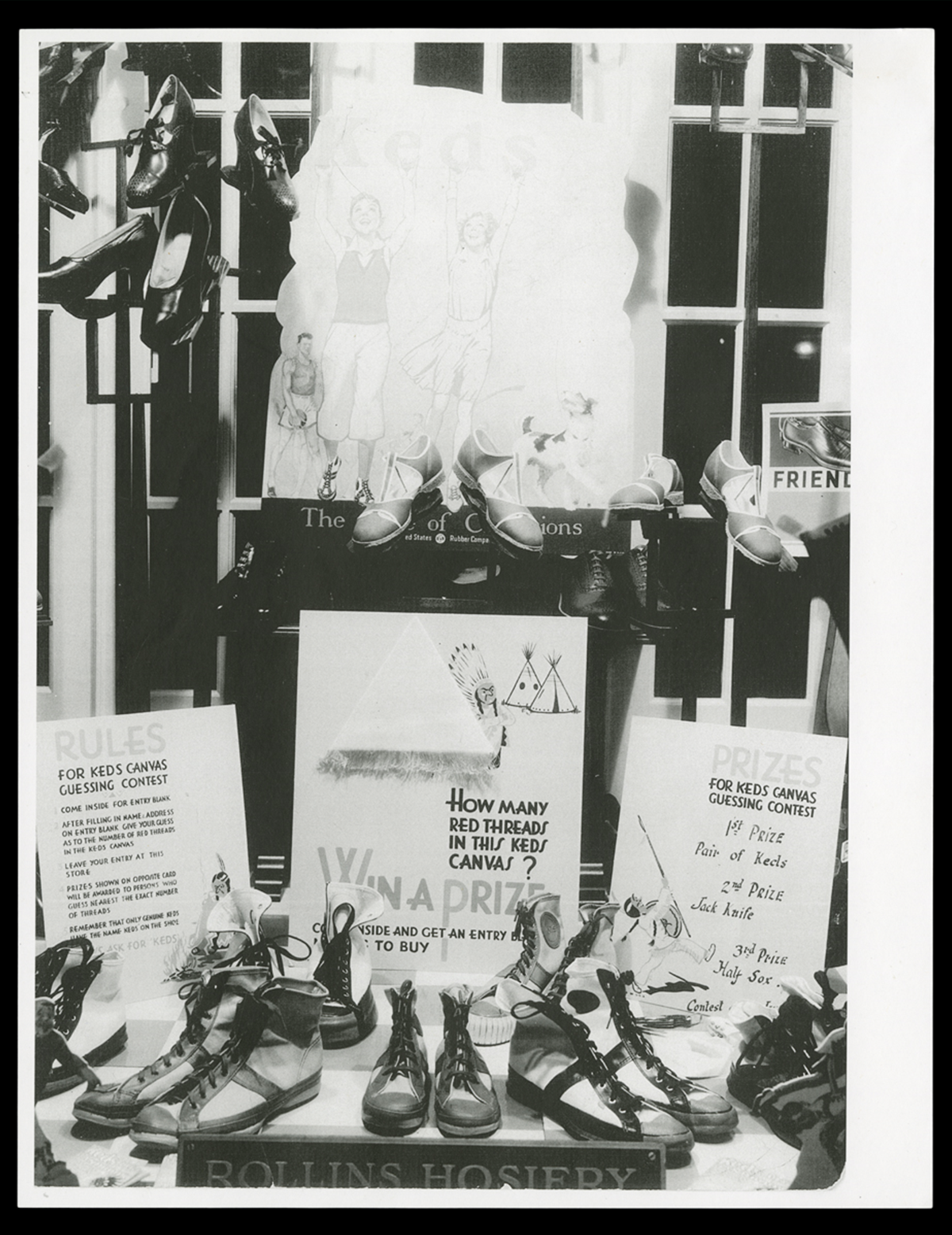

Additionally, kids loved fluoroscopes! Stores would advertise their shoe-fitting fluoroscopes alongside other child-friendly customer perks like balloons, contests, and candy.

Keds window display at the Campbell Boot Shop, Charlevoix, Michigan, circa 1930. This shoe store used window display contests to attract young customers with the possibility of brand new shoes. / THF723228

Until the late 1940s, fluoroscopes were used everywhere from first aid stations on job sites to quality control inspections on orange tree farms. However, the lack of regulation for radioactive machines endangered people. Several high-profile incidents eroded the public's trust in fluoroscopy. For example, between 1941 and 1943, 57 California Shipbuilding Corp. workers received mutilating radiation injuries after using the company's first aid fluoroscope. This lack of regulation also affected shoe fitting X-rays. A 1948 study of Detroit-area shoe stores showed that over 20% of stores' fluoroscopes produced 16 to 75 röntgens — the measure of radioactive discharge — per minute. At the time the maximum radiation exposure recommendation was .3 röntgen per week.

X-ray tube, circa 1915. Vacuum tubes like this are used to produce X-rays in fluoroscopes and other forms of radiography. / THF174376

In 1950, Carl Braestrup, senior physicist for New York City hospitals, was one of the first health officials to warn the public that shoe-fitting fluoroscopes could cause radiation burns and leukemia, especially in children. That same year, city health officers in Los Angeles reported that shoe-fitting fluoroscopy caused abnormal bone growth in children. But shoe stores were initially reluctant to get rid of their machines; Los Angeles shoe store owners claimed that parents' demand for X-rays drove them to keep them. It took until 1957 for Pennsylvania to become the first state to ban shoe-fitting fluoroscopes.

In many ways, the shoe X-ray represents a time when science and commerce seemed to go hand-in-hand but went toe-to-toe instead. Innovations, like the X-ray, were used to turn profits but also harmed the public.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope being photographed for digitization. / Photo by Staff of the Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The WASP: “An Airplane Knows No Sex”

During World War II, a groundbreaking group of American women defied expectations and gender bias to apply their skill in the air, flying over 60 million miles and 12,650 ferrying missions for their country during the war. Nearly 1,100 women volunteered as pilots with the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). As WASP Bernice “Bee” Haydu said in a 2013 oral history interview for The National WWII Museum, “We showed the world that an airplane knows no sex.” Yet while they flew military aircraft for military purposes and risked their lives in doing so, they remained classified as civilian aviators and as such they received no military status, benefits, or recognition until decades later.

Even prior to the United States' entry into war, two pioneering pilots Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love were pushing for opportunities for American women in military aviation. They lobbied for inclusion and were bolstered by successful efforts abroad, where women were flying in support of the European Allies. Cochran and Love submitted independent proposals to the Army Air Forces for the noncombat employment of women. As a result, the two women were granted leadership of two programs — the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron led by Love and the Women’s Flying Training Detachment directed by Cochran. The momentum to use women pilots had some powerful advocates. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about the subject in her September 1, 1942, "My Day" column: “We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.” In August 1943, a year after the inception of the two, they were merged into the Women Airforce Service Pilots under Cochran with Love in an executive role.

The WASP program took off. Trainees were based at Avenger Field near the small town of Sweetwater, Texas. A love of flying drew fierce competition for limited spots. Training on military aircraft was rigorous and difficult even for the experienced pilots accepted into the program. Unlike male fliers, who learned to fly as part of their training, the WASP trainees entered their program knowing how to fly. They were required to have completed 200 to 500 flight hours before being admitted to the program. Still, the washout rate hovered at just under 50 percent. Out of 25,000 applications received, 1,830 women were accepted and of those 1,074 completed their training.

Ruth Westheimer (2nd from left) and fellow trainees at Avenger Field. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.155

The 30-week training program at Sweetwater included 210 hours of flying time on a wide variety of military aircraft. The training culminated in a graduation where the pilots received their wings, often pinned on by Cochran herself. Whether the civilian graduates would receive wings like their military pilot counterparts was initially questioned by some. And Cochran personally funded the purchase of the insignia for the first seven graduating classes (43-1 through 43-7).

The WASP went on to their assignments, ferrying planes from factories to airbases, “test-hopping” planes that other pilots had flagged as unreliable, and even towing targets used to train anti-aircraft gunners.

Class 43-6 included 22-year-old Ruth Westheimer. Raised by German Jewish immigrant parents in Jackson, Michigan, Westheimer was fascinated by flying from a young age, watching planes at the airstrip near her home. After graduating from Jackson High School in 1939, she plotted her path to the skies and attended the Civilian Pilot Training Program while studying at Jackson Junior College. She took a job as a secretary at Montgomery Ward & Co. in Chicago until she jumped at the opportunity to fly. Accepted for WASP training in April 1943, Westheimer initially failed the required day-long physical exam due to insufficient lung capacity. Determined to fly, she recognized what was holding her back and brazenly demanded to be tested again after removing her brassiere. She passed and became part of Class 43-6. In Sweetwater, Westheimer flew a variety of planes, but her favorite was the AT-6 “Texan” training aircraft. Westheimer loved ferrying duty.

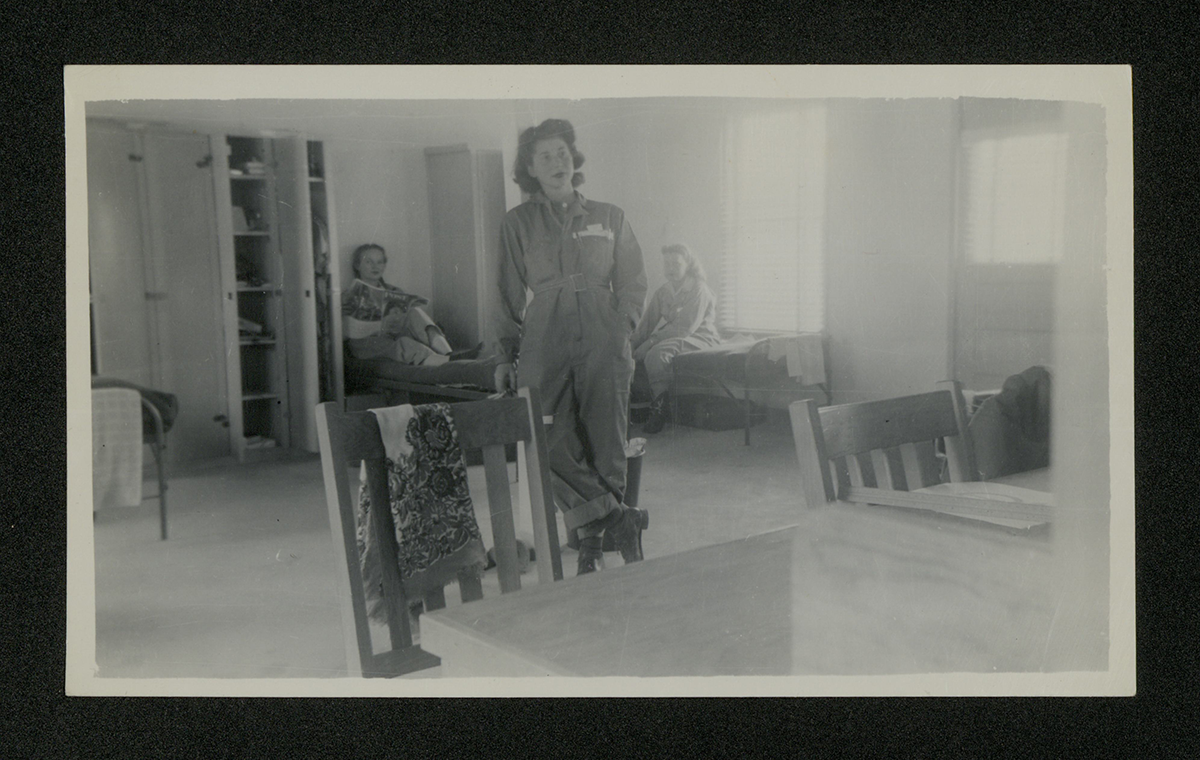

Ruth stands in the foreground with her trainee roommates at Avenger Field. Ruth’s caption reads, “This is half of our bay. The gal with the magazine and pigtails is Mac. Bernie is the other one. Both are kids.” / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.073

For a time, Westheimer was based not far from home, with the 3rd Ferrying Group at Romulus Army Air Field in Michigan. At the same time, Chinese American Hazel Ying Lee was also flying out of Romulus. Lee is a tragic example of the extreme risks inherent in the WASP’s work. Lee was later transferred to Texas for Pursuit School training. She died on November 25, 1944, two days after a collision while transporting a P-63 Kingcobra fighter aircraft. She was the last of 38 WASP who died in service.

Clipping from Ruth’s scrapbook showing Hazel Lee and her husband. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.237

February 1944 travel orders for Westheimer and Hazel Lee from Romulus to Montreal. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.244

During one of Westheimer's assignments, flying with a group from Montreal to New Jersey, the WASP ran into weather trouble. Navigating visually, she eventually found an airfield and was assisted in landing by military personnel. Westheimer later said, “You should’ve seen the surprise on their faces when they saw a 120-lb girl in uniform climb out of the cockpit of that large military plane.”

Ruth Westheimer steps out of a Fairchild PT-19A primary trainer aircraft at Avenger Field on May 6, 1943. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.017

WASP often carried out their missions in a hostile atmosphere. Despite the shared purpose of American victory, not everyone wanted the women to succeed. There was even some resentment from male pilots who wanted the women’s stateside jobs rather than overseas combat duty.

In March 1944, Cochran and Army Air Forces Commander General “Hap” Arnold presented a strong case for militarization of the WASP before Congress, but the push was unsuccessful. With the war in Europe won and the war in the Pacific winding down, the WASP militarization bill was defeated in the House of Representatives on June 21, 1944. With no active path to service, the WASP were dismissed and their program disbanded, finalized on December 20, 1944. The devastated women even had to pay for their own fares home. Some were able to get contract work with Air Transport Command or flying in other capacities, but many returned to prewar occupations or began new lives.

Ruth’s graduation announcement from Class 43-W-6. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.207

Ruth Westheimer moved to Boyne City, Michigan, with her husband, 10th Mountain Division Army veteran Marshall Neymark. They raised four children, and she worked at city hall as treasurer. Later in life, Ruth made her way back to flying. Her second marriage to Boyne city manager and pilot Forbes Tompkins returned her to the cockpit. She renewed her pilot's license and began to fly again in their Cessna. After Forbes retired, Ruth stepped into the position of city manager, the first time the position was ever held by a woman.

The WASP were finally recognized for their service in 1977, when they were retroactively granted veteran status. In 2009, a bill passed to award the Congressional Gold Medal to the WASP. At the U.S. Capitol ceremony in March 2010, Ruth was one of the 200 (out of 300 surviving) WASP present to receive her award. She considered herself a “Lucky Lady,” in the right place at the right time. Ruth passed away in 2016 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery — a right that would not have been afforded during the war.

This guest blog was written by Kimberly Guise, Senior Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs at The National WWII Museum, and Curator of Our War Too: Women in Service, currently on display at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation now through September 7.

The roof of The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation covers nearly 12 acres. A one-inch rainfall results in almost 326,000 gallons of water landing on that expansive roof.

Where does the runoff go?

The architect, Robert O. Derrick, and landscape designer, Jens Jensen, who planned the building and grounds, cloaked the infrastructure that managed that runoff deftly. The following article walks you through the route that the water takes as downspouts and pipes move it from the museum roof to a 2.5-acre pond behind the museum and on to the nearby River Rouge. Today the pond, out of sight to the public, plays a vital role in reducing the risk of flooding and silt buildup in the nearby River Rouge, and it enables the reuse of runoff to irrigate the grounds.

Pond located north of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and southeast of the Dearborn Transit Center (upper right). / Drone photograph courtesy of Bart Fraley.

The pond predated the 1929 founding of The Edison Institute.. It and another set of ponds to the west resulted from clay extraction by a local brickyard. The Ford Motor Company built a powerhouse next to the eastern most pond at the Ford Engineering Laboratory. This pond became the holding tank for runoff from the museum roof.

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

Postcard, Engineering Laboratory and Airport, Ford Motor Company, 1925 / THF727149

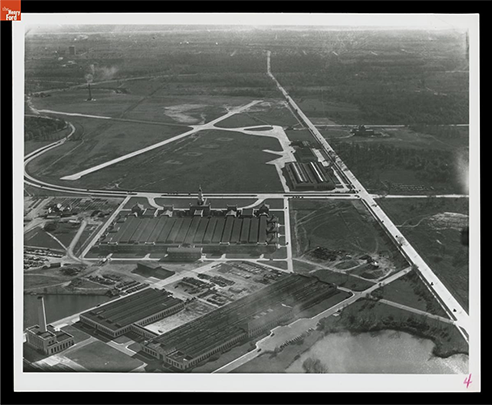

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Aerial view showing the museum with its 12-acre roof, November 1931 / THF700318

Landscape architect Jens Jensen mapped “the pond” behind “the museum building” in December 1931. Moving water from the roof to the pond begins with downspouts embedded into museum walls and structural columns throughout the Great Hall. Because this flow enters the system above ground, gravity moves it into the drainage infrastructure under the museum.

Rainwater also flows into yard drains around the museum. Since the yard drains are below grade, the system needed pumping stations to collect and pump water vertically to send water up and into the roof-water collection system closer to ground level. Architect Robert O. Derrick incorporated two pumphouses into his museum plans in 1928 to house these pumping stations.

Derrick, noted for his Colonial-revival designs, disguised the pumping stations in reproductions of other structures popular during the Colonial-revival era. The inspiration included a garden feature from Mount Vernon, home of George and Martha Washington, and the observatory that astronomer David Rittenhouse built in Philadelphia after he moved there in 1770. Rittenhouse gained international attention in 1769 because of his observation of the transit of Venus. His relocation to Philadelphia in 1770, the largest city in the Colonies at the time, facilitated his engagement with the vibrant scientific community there. Contemporaries described his Philadelphia observatory as “a small but pretty convenient octagonal building, of brick” [William Barton, Memoirs of the Life of David Rittenhouse (1813), note 111].

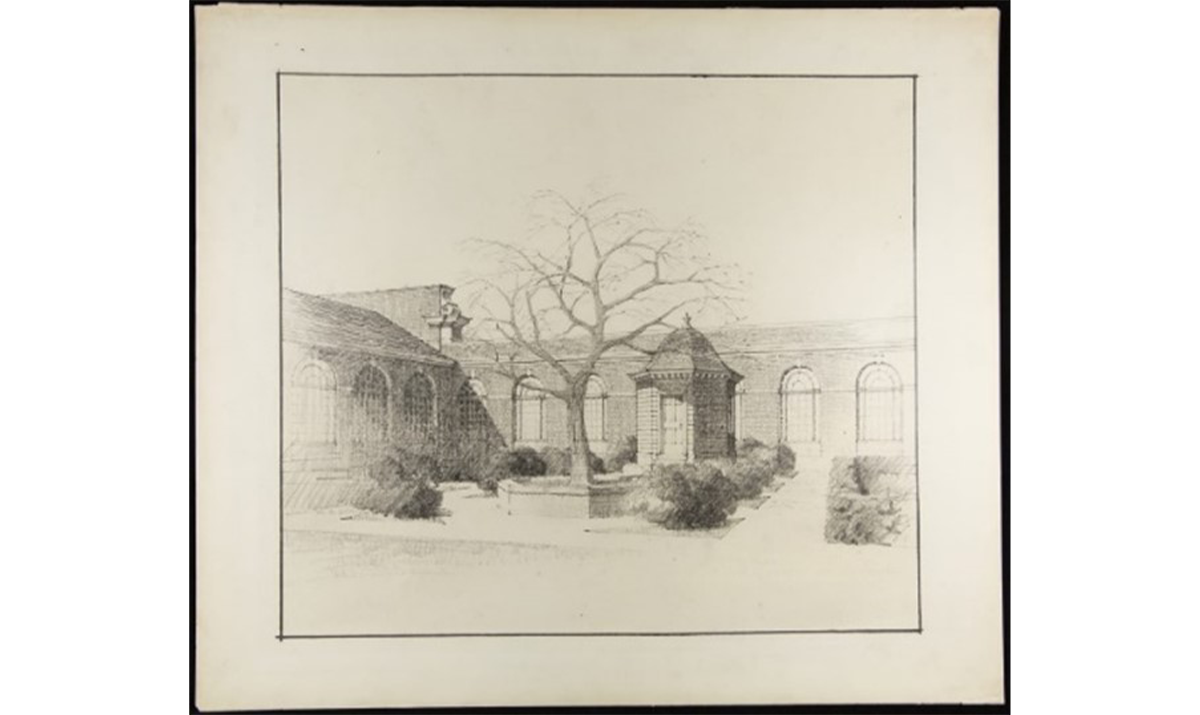

Virginia Court pumphouse based on a garden feature from Mount Vernon, 1928 / THF294374

Pennsylvania Court pumphouse based on Rittenhouse’s observatory, 1928 / THF294392

The stations, located in each of the two large courtyards on each side of the main entrance to the museum, hold water and pump it into the stormwater infrastructure as needed.

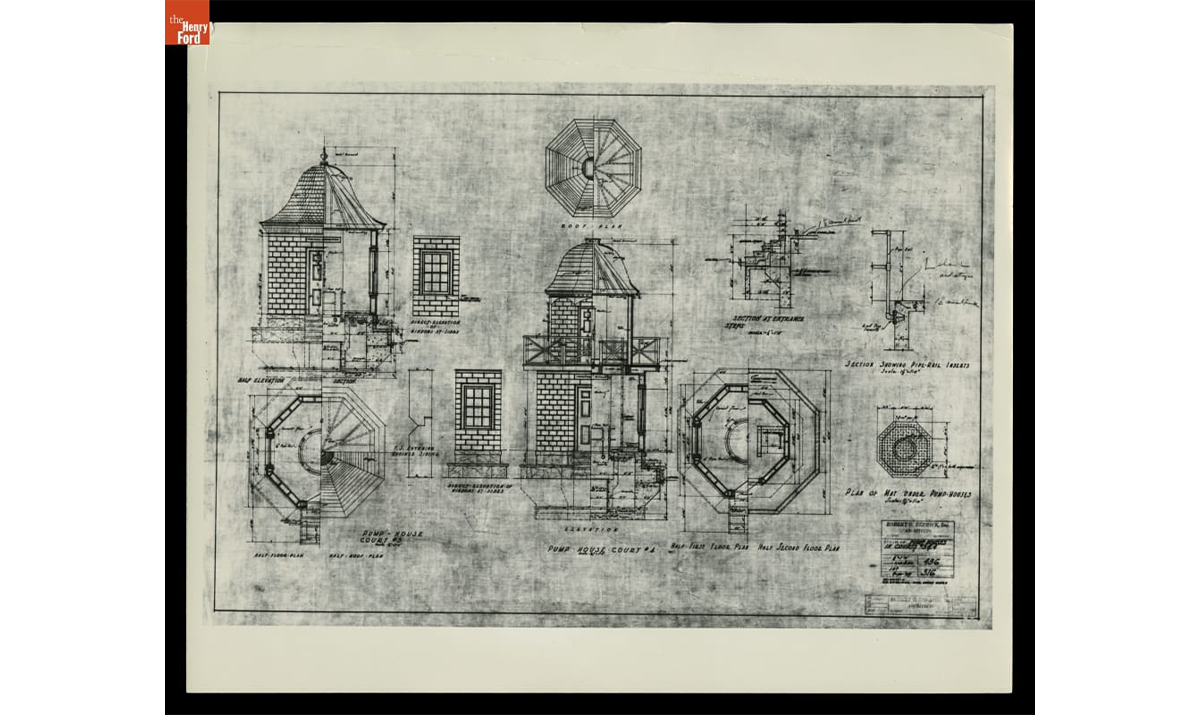

Details of pumphouses in museum courtyards, drawn by Robert O. Derrick, Inc., Architects, 1929 / THF98551

Gravity facilitates rainwater flow to a 24-inch main line under the museum, which channels runoff to the basement of the powerhouse in the back of the museum. Facilities staff replaced the entire ductile iron system in the powerhouse basement during 2025 with stainless steel. This was the first replacement since the entire system was built in 1929.

Storm-pump system in the powerhouse basement. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

Two 75-horsepower motors, located in the basement of the power house, handle large storms. / Photograph courtesy of Jon Bennett.

In what's designed as a "wet" system, water always fills the lower portion of the infrastructure. As rainwater drainage increases the pressure in the system, it pushes water out of the museum and into the retention pond.

What happens after rainwater runoff enters the pond?

The retention pond allows sediment to settle out of the water within the pond rather than in the River Rouge. It also accumulates for later use to water the grounds around the museum, Lovett Hall, and the Josephine Ford Plaza. A large irrigation pump draws water from the pond to the irrigation piping.

The stormwater management system within Greenfield Village converges near the Suwanee dock and flows into the Suwanee Lagoon. The water in the lagoon is regulated by a drain that flows into the Oxbow which connects to the River Rouge. Facilities staff can use a pumping station at the Oxbow to increase the rate of pumping into the River Rouge in case of excessive rainfall. That pumping station also works as a protection. If the River Rouge is too high, a valve can be exercised to prevent backward flow into The Henry Ford's stormwater management system.

Each pond in the Village serves as a large holding tank with an inlet on one side and outlet on the other, depending on which direction the water needs to flow to reach the Suwanee.

Mill pond construction in the Greenfield Village craft area, March 2003 / THF10348

Mill pond in Greenfield Village’s craft area. / Photograph courtesy of Lee Cagle, May 2018.

Water within the system irrigates lawns and gardens within the Village. A large irrigation pump near Henry Ford Academy draws water from the Suwanee Lagoon for this purpose.

Overall, the water management system has been integral to The Henry Ford’s efforts to reduce waste and reuse runoff. An overview of five years of Green Museum Work undertaken from 2019 through 2024 acknowledges this system as one of the historic precedents and an inspiration for current efforts. It takes staff expertise, financial commitment, and regular maintenance to continue such efforts, but the investment pays off in reduced water bills and healthier riverine ecosystems. Updates to the system during 2025 should prepare it for the next 100 years.

Jon Bennett is Assistant Construction Manager and Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. The title of this blog was inspired by Al Green’s and Mabon “Teenie” Hodges 1974 song by the same title.

From Frames to Film at Ford Motor Company

Did you know that the Ford Motor Company was not only a pioneer in the automotive industry but also involved in the world of filmmaking? .

In the early years of the Ford Motor Company, various photographers and firms were hired to capture images, leading to the creation of the Ford Motor Company's Photographic Department. Their initial purpose was to document production methods, provide illustrations for publications, and promote Henry Ford and his company. This was the backbone that sparked another of Henry Ford's interests: filmmaking.

Henry Ford developed an interest in filmmaking in 1913 after he saw a film made by an external company about the Highland Park automobile factory. By April 1914, he instructed Ambrose B. Jewett from Ford’s Advertising Department to procure a camera and an operator. Within months, the company became established for their use of film in advertising, as documentation, and as a way to share industrial processes with the general public.

Ambrose B. Jewett of Ford Advertising Department is visible at center, with painter Irving Bacon (left) and Henry Ford (right), 1919. / THF95164

Henry Ford was fascinated by the potential of motion picture film to train workers and communicate daily news to the public, including scenes from their lives and the wonders of manufacturing at the Ford Motor Company. Starting with a modest two-man team in 1914, the Motion Picture Department expanded to 24 members, acquiring advanced 35mm cameras and establishing a film processing operation at the Highland Park Plant, comparable to Hollywood studios. By 1915, they began releasing news reels as “The Ford Animated Weekly.” Each episode covered a variety of current news events, such as the launch of the U.S.S. Arizona and the Liberty Bell on tour for the Panama-Pacific Exposition, in addition to animated segments.

The company's inaugural film, "How Henry Ford Makes One Thousand Cars a Day," naturally centered on its own processes. Initially, the department concentrated on current events and educational content; by the 1920s, it had shifted towards promoting popular themes like road quality, safety, and advanced farming techniques. As early as 1917, they recognized that film could assist in educating factory workers in their repair work by slowing down footage of fast-moving machines--a notion highlighted in an article from “The Ford Man” published on September 20, 1917.

Article from "The Ford Man" periodical, September 20, 1917 / Image by staff of The Henry Ford

The Ford Motor Company Photographic Department was responsible for both motion pictures and still photography, remaining the only department of its kind until 1918. It was initially housed in the administration building at the Highland Park Plant, moving to the administration building at the Rouge Plant in Dearborn, Michigan, in the mid-1920s. In 1956, it relocated again, this time to the World Headquarters on Michigan Avenue in Dearborn.

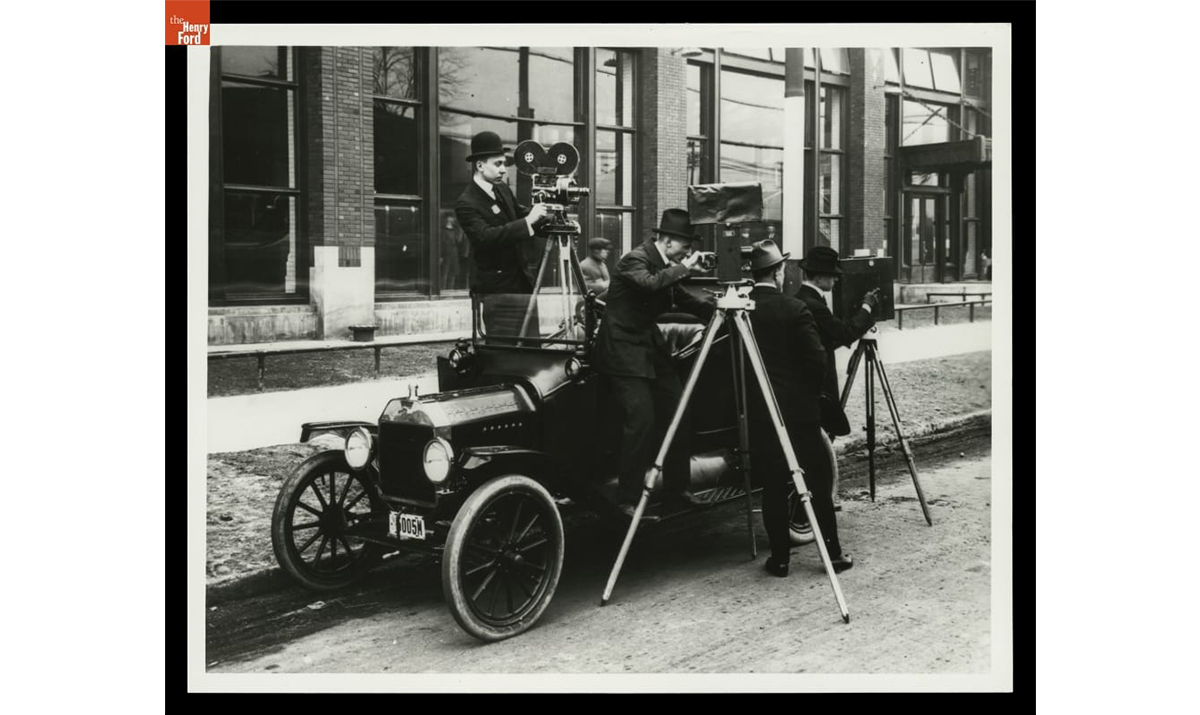

Workers at Cutting Tables and Copy Camera, Ford Photographic Department, Highland Park Plant, 1914. / THF124964

Initially, the department's photographers focused on documenting the company's products, facilities, and workforce. However, following the move to the Rouge Plant, the focus gradually shifted toward public relations and promotional activities. While few internal documents regarding the department's organization and management have survived, the negatives and photos preserved in the company's archives from the 1950s were ultimately donated to The Henry Ford in 1964. Notable photographers who worked for Ford Motor Company include George Ebling, Joseph Farkas, Michael Malley, E.S. Purrington, William Stettler, and C.E. Wagner.

Ford Motor Company Photographers with Ford Model T Touring Car outside the Highland Park Plant. / THF119387

For years, the Ford Motor Company was one of the world's major film producers, with its films reaching audiences both nationally and internationally. These films were distributed through Ford branches to Ford agents, who then screened them in theaters within their respective territories.

In 1956, Ford Public Relations films achieved a record audience of over 24 million viewers worldwide. The total audience for the year, excluding television, reached 24,267,455, reflecting significant growth in both domestic and international viewership. Throughout the 1950s, the types of films produced included categories like the Automobile Industry, Americans at Home, Vacation Films, Educational Subjects, and Driver Education Films.

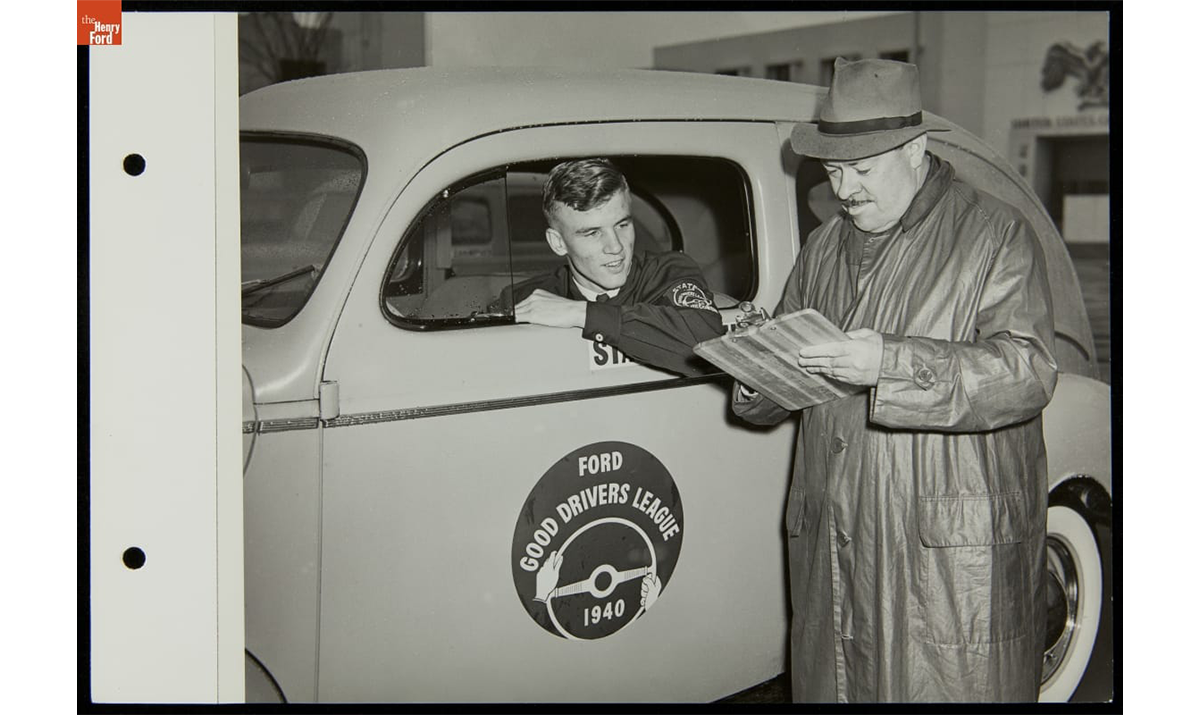

Young Man Taking Driver's Test, Ford Good Drivers League, Ford Exposition, New York World's Fair, 1940. / THF216125

In 1963, Ford Motor Company gifted over 1.5 million feet of motion picture film, created between 1914 and the early 1940s by its Motion Picture Department, to the United States National Archives. The Ford Film Collection provides comprehensive coverage of the era's current events, educational topics, and special interests. The Henry Ford's Benson Ford Research Center secured permission on December 15, 1994, to reproduce and distribute high-resolution copies from the National Archives of those collections relevant to the early days of the Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford's personal endeavors, and subjects associated with The Henry Ford. The versions available in our online catalog and on YouTube are low-resolution samples with time codes, such as "Ford and the Century of Progress, Part 2."

The Ford Motor Company's journey from still photography to motion pictures is a testament to its innovative spirit and commitment to communication and education. By embracing filmmaking, Henry Ford not only documented the company's achievements but also shared the wonders of manufacturing and modern life with the world. Thankfully, Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company had such a passion and dedication to keep this work flowing, and it is now available for research. If you’d like to learn more about this collection or others, please email us at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Stephanie Lucas is a Research Specialist at The Henry Ford.

If you asked someone to picture a library, most would think of their local public library that presents the most recent, riveting, and relevant titles on their shelves. What they might not picture is the library here at The Henry Ford. Located in the Benson Ford Research Center — which you might have seen if you ever visited the Reading Room or parked across the street while in the back of the museum — is the Archives and Library collection at THF. The Henry Ford’s library is a little bit different from a public library because our team adds books to the collection based on their fit with THF’s mission and vision of American innovation!

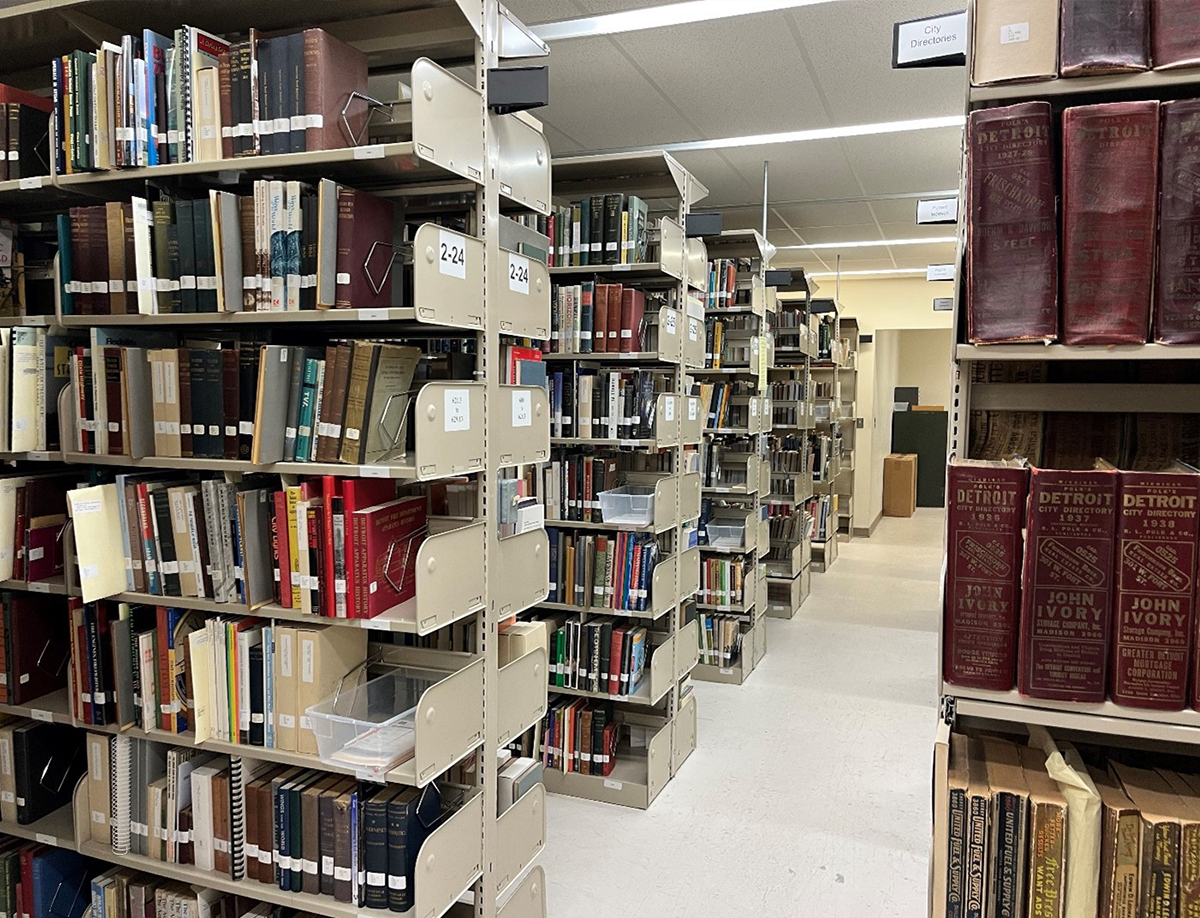

The library stacks in the Benson Ford Research Center. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

One thing that the library collection at THF does have in common with a public library is that our staff are passionate about stewarding these collections for current and future learners. When it became clear that open shelving space for new books was decreasing, the library team decided they needed to act quickly. To begin addressing these space limitations, I joined the Archives and Library team as an intern to conduct a capacity study of the library collection’s storage.

During my internship, I calculated the total amount of space being taken up and the total amount of storage space available, and compared these numbers. Without a standardized system for measuring library storage or for assessing capacity I ran into some difficulties trying to get an accurate view of how full each shelf was. After some trial and error, I eventually adopted a system used by the Archives and Library staff to assess the capacity of the library storage along a scale of 0%, 25%, 50%, 75% to finally, 100%. These somewhat broad values allowed me to assess how full the shelves were, taking specific book storage best practices into account while measuring. As I embarked on this project, I found there were many unlabeled shelves and incomplete floor plans, which complicated how I collected data. After many weeks of measuring the total space available and assessing the capacity of each shelf, I found that the three floors of library storage are just over 70% full!

The archives in Benson Ford Research Center. / Photo by staff of The Henry Ford

Once I determined how much space was being taken up, I then needed to find the best solutions for addressing these all-too-common space constraints. After some research, I found that there were five potential solutions, each with its own level of applicability for the library collection. These solutions included:

- Shifting

- Deaccessioning

- Digitizing

- Installing compact shelving

- Renting off-site storage

Most of these options, despite being a good fit for libraries across the country, were not ideal for us at The Henry Ford. After assessing each solution in a rubric with categories, including collaboration, cost, efficacy, and time, I found that shifting and installing compact shelving were two of the best solutions. While neither of these are an immediate fix, they each provide opportunities to help our Archives and Libraries staff to steward the growing collection for generations of scholars to come!

Julia Noriega was a Ford Foundation Diversity and Inclusion Intern for Archives and Libraries at The Henry Ford