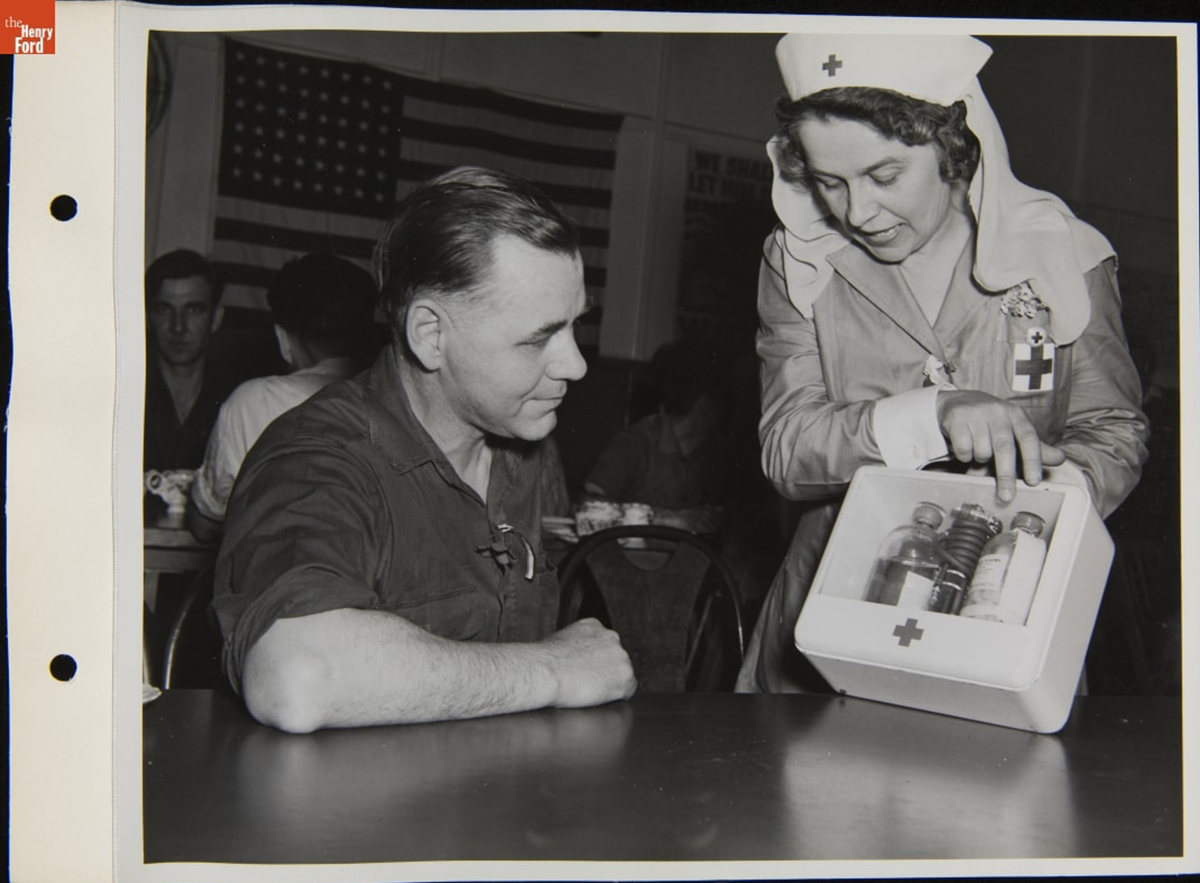

The following article shares highlights from the collections of The Henry Ford to illustrate work undertaken by female Red Cross volunteers during World War II. More than three million women repaired and drove vehicles as part of the motor corps, cared for wounded service members in military hospitals, operated blood banks or operated canteens overseas, among numerous other tasks. The collections included here can help us to understand the role of women in the American Red Cross during wartime.

Join American Red Cross poster, 1942. / THF289755

The poster above conveys the centrality of women to the U.S. military response during World War II. The Red Cross, a non-governmental organization, “always stands by as friend to the service man” (Redlands [California] Daily Facts, 12 November 1941). The illustrator, Robert C. Kauffmann, emphasized the Red Cross nurse in other colorful posters during this time—aimed at recruiting nurses, field directors and hospital recreation workers. Sometimes he contextualized the nurses’ work in domestic flood relief, sometimes in war relief, but always with the message to “join.”

Women’s Motor Corps

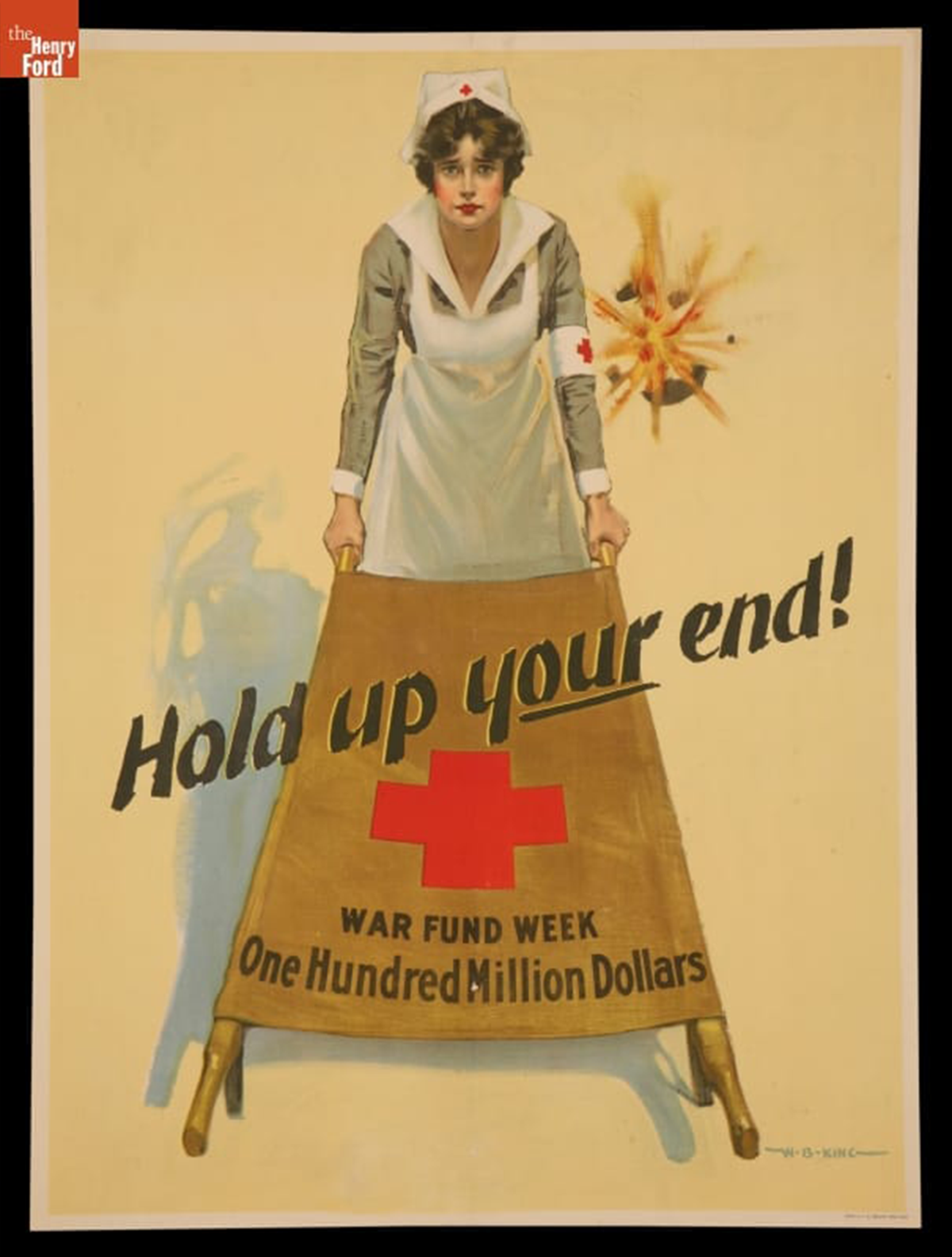

Comparable service during World War I set a precedent. The American Red Cross Women’s Motor Corps began in 1917 and included women volunteers who transported the sick and wounded in ambulances.

Red Cross training using Ford Model T ambulances at the Highland Park Plant, July 1918. / THF130013

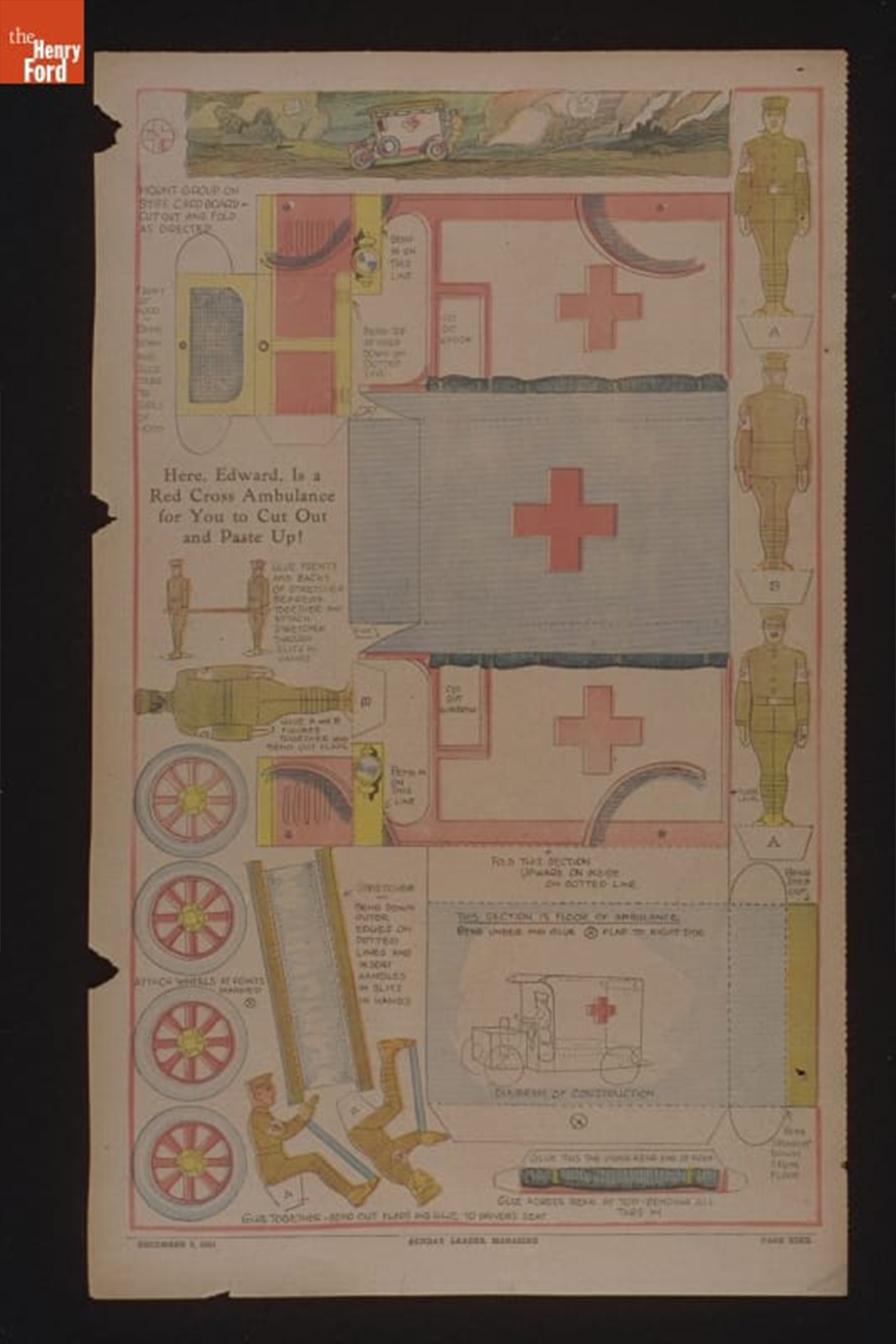

The American Red Cross, as a non-profit organization, depended on volunteers and charitable donations to meet need. During World War I, membership increased from 17,000 to over 30 million adults and older children. Contributions amounted to over $400 million in money and supplies. Ford Motor Company contributed $500,000 during the early years of World War I. The Red Cross turned around and used those funds to purchase Ford vehicles, nearly 1,000 of them, including 107 ambulances, for wartime use through the Motor Corps. Newspapers helped promote this work especially to young readers, as the following colorful cutout of a Ford ambulance represents.

World War I Red Cross Ambulance Cut-Out Paper Toy, December 9, 1917. / THF342142

Soon after war erupted in Europe in August 1939, urgent requests from the Red Cross began to reach wealthy Americans. Edsel Ford indicated his intention in May 1940 to support the fund drive required to meet the unprecedented need for assistance in war-torn Europe. He sent a postal telegram to W. J. Scripps of WWJ radio explaining that “Detroit’s share of the proposed relief fund can be raised only by the generous cooperation and support of everyone.”

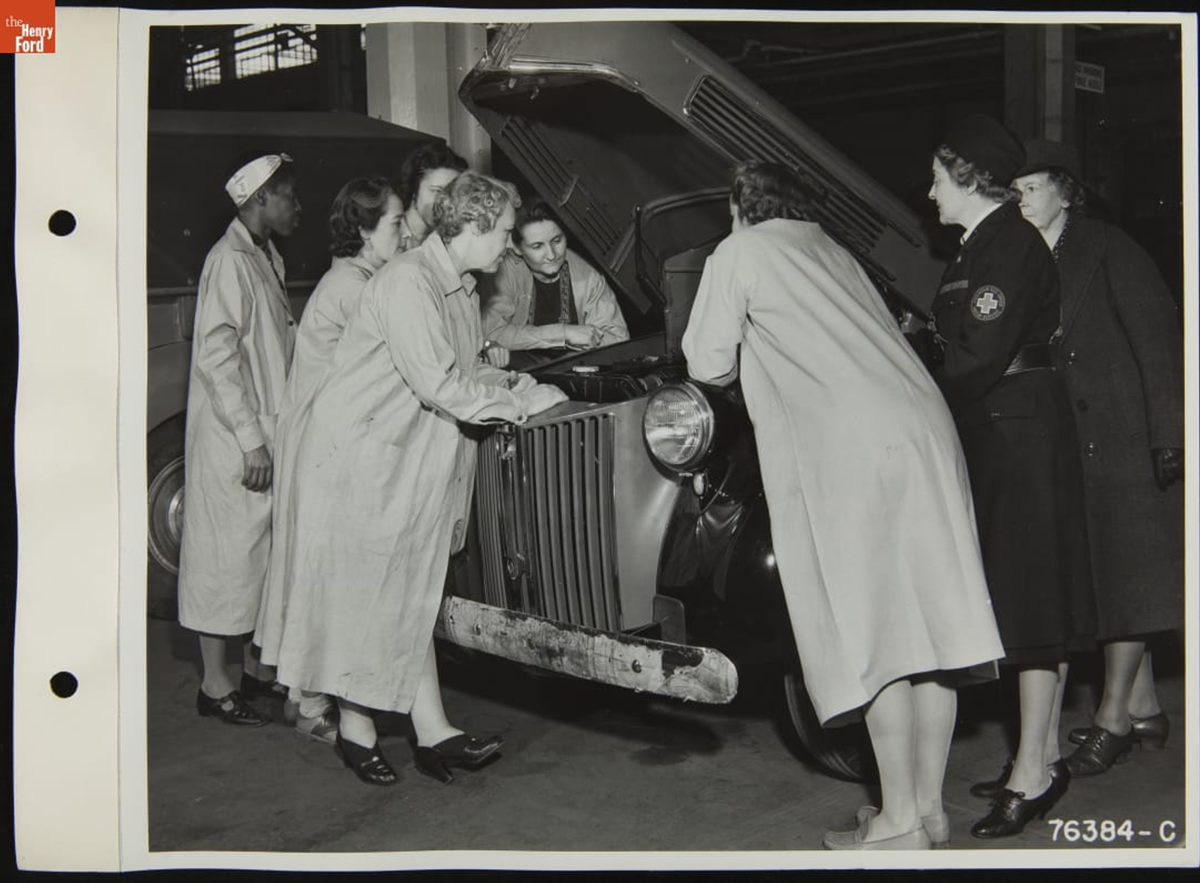

Ford Motor Company maintained its support of the Women's Motor Corps during World War II as 45,000 drivers filled the Corps' ranks. This included African American chapters in some cities. The volunteers logged over 61 million miles ferrying Red Cross staff and supplies, couriering packages and messages, and occasionally assisting with Army and Navy transportation needs.

American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps members becoming familiar with engines during an auto maintenance class, Ford Motor Company, November 1941. / THF270093

Keeping the vehicles on the road required expertise. In 1941, Ford Motor Company began to provide automobile maintenance classes for the local Women’s Motor Corps at its Highland Park facilities. Instructors trained the volunteers in the mechanical skills they needed to keep their vehicles moving in times of emergency.

American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps members looking under the hood of a Ford ambulance, June 1942. / THF265816

Ford Motor Company donated its 29 millionth Ford automobile to the cause. The Super DeLuxe station wagon rolled off the Rouge Plant assembly line in April 1941. Edsel Ford presented this vehicle to the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross for use by the volunteers of the Women’s Motor Corps.

The 29 Millionth Ford and a driver from the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross Women's Motor Corps, April 29, 1941. / THF270147

Workwear for Health Care

The American Red Cross hired trained nurses to assist doctors treating service men. Gray ladies nurse's aides provided an additional layer of volunteer support in military hospitals and boosted the morale of patients. They all wore the distinctive red cross emblem on their uniforms, adopted at the 1864 Geneva Convention to designate medical personnel during wartime. Active-duty Red Cross nurses wore plain white uniforms with bishop collars and caps and a dark blue cape lined in red during wartime, which was standard issue throughout World War II. As of December 24, 1915, active-duty nurses stationed abroad wore gray cotton crepe dresses with a white pique collar and cuffs, cap, and brassard. Public health nurses wore gray chambray. Uniform regulations decreed that the red cross appear prominently on the front of the cap, brassard, and nurse’s cape.

World War I era poster depicting the uniform of a Red Cross public health nurse, 1917. / THF112608

The Gray Lady Service also tended to soldiers in non-medical capacities during and between wars. They wrote letters, delivered bandages, or served snacks to men who needed physical and emotional comfort.

Gray Lady Service uniform, 1940-1945 (left). / THF173341; Gray Lady Service uniform, 1955 (right). / THF94383

The indoor uniform of the Gray Lady Service consisted of a gray cotton dress with detachable white collar and cuffs, a two-inch woven red cross on the upper pocket, and white epaulets worn on each shoulder. The red bars and chevrons worn on the sleeves conveyed length of service (Shirley Powers, “A Guide to American Red Cross Uniforms,” 2nd ed., 2006).

American Red Cross Volunteer Nurse's Aides, Peoria, Illinois, May 20, 1942. / THF289753

The American Red Cross and the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense specified details of the volunteer nurse’s aide uniform in November 1942. It consisted of a blue jumper-apron worn over a regulation white poplin blouse. Nurse’s aides donned the uniform after the first 34 hours of training, and the cap after completion of the 80-hour course. The full uniform included a three-inch joint Red Cross and Office of Civilian Defense nurse’s aide emblem, sewn on the upper left sleeve of the blouse, two inches below the shoulder seam. Chapters could recognize hours of service by awarding white stripes but only for those volunteering in hospital wards, in clinics, and in health agencies qualified for these.

National Blood Donor Service

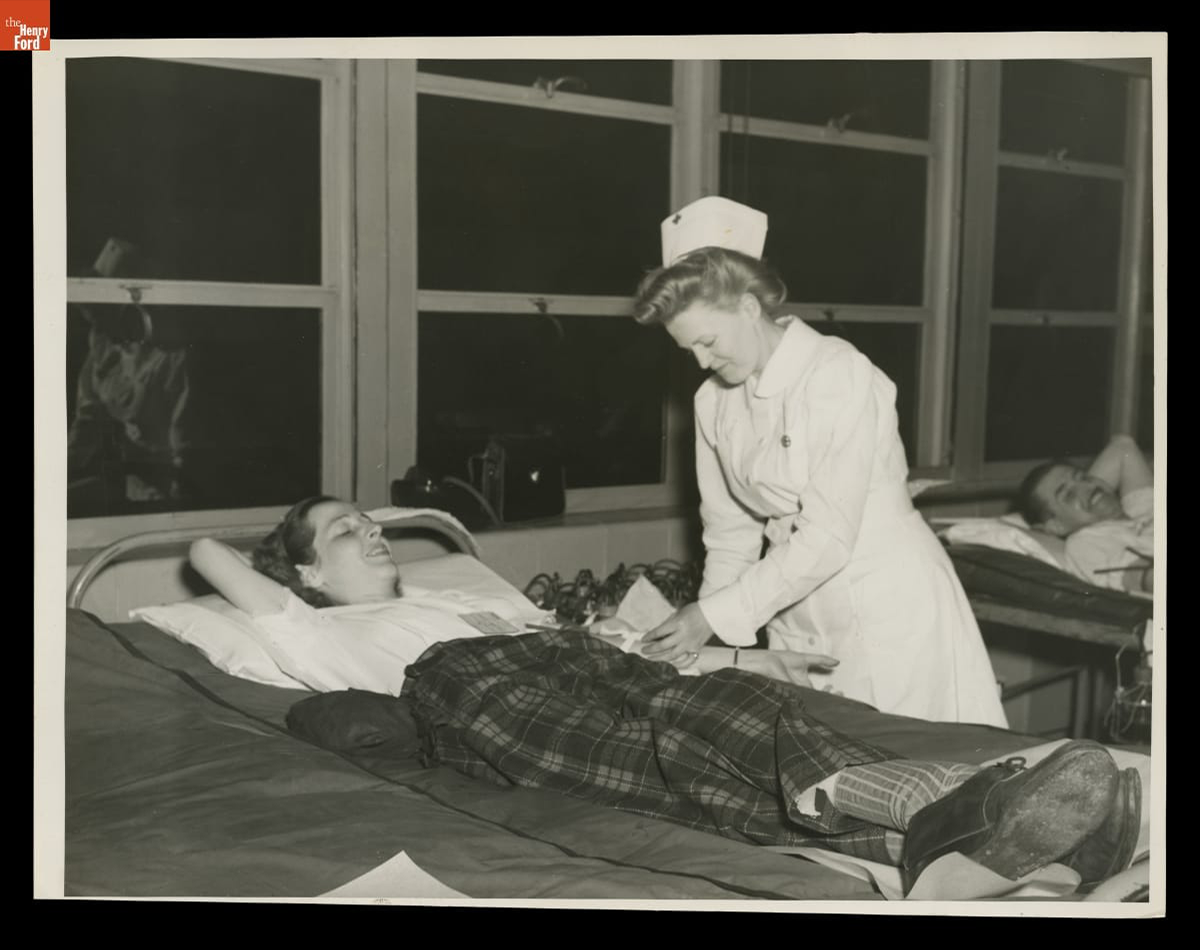

The American Red Cross began its National Blood Donor Service for the U.S. military in February 1941. Volunteers worked in the new blood banks, collecting blood and plasma donations and shipping them to hospitals caring for soldiers wounded in battle.

25,000th Blood Donor at the Ford Rouge Plant Pressed Steel Building, May 1943. / THF290075

Women working at Willow Run had their first chance to donate blood to the National Blood Donor Service in November 1944. The Ford Motor Company built its Willow Run Bomber Plant in 1941. Approximately one-third of the labor force were women. They performed office work but also drafted designs and worked on the assembly line, riveting and welding B-24 bomber components. At the plant's peak in 1944, Willow Run crews produced an average of one bomber every 63 minutes.

A Red Cross nurse draws blood from a female Ford Motor Company employee at Willow Run Bomber Plant, November 27, 1944. / THF728198

Canteen Girls and Donut Dollies

The female Red Cross volunteers who faced some of the most dangerous situations during World War II included those who served overseas as Canteen Girls or Donut Dollies. This work began during World War I in service to soldiers on the move, as a 1918 photograph of an African American woman in Detroit, handing bananas to soldiers indicates. During World War II, women traveled in mobile club wagons that often operated close to intense fighting. Critics claimed that the young women, all college educated and carefully selected, assumed significant personal risk. Julia Ramsey, author of “’Girls’ in Name Only” (Auburn University, 2011), claims that these women had access to battle and combat that no civilian women had previously. Paige Gulley, author of “After All, who takes care of the Red Cross’s morale?” (Chapman University, 2021), analyzed primary source created by the volunteers themselves to explain how women relied on each other to manage stress and meet expectations.

These examples represent the breadth of service and due diligence that female volunteers provided to the American Red Cross. The organization was not perfect and need often exceeded the capacity of staff and volunteers to meet it. The opportunity to work for humanitarian causes drew women who wanted to do something to support the U.S. cause during World War II. In addition to the options described above, women pursued other outlets through the Red Cross that relieved stress for individuals and families in crisis.

Debra A. Reid, Curator, Agriculture and the Environment, with Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, and Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life, The Henry Ford

Draft by Draft: The Making of The House by the Side of the Road

Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson at desk. / Photo feature in Black Belt Living, April 2012

Before starting my role as the Processing Archivist for the Jackson Home in 2024 — which would soon find me processing the papers, photographs, and other 2D materials of the Jackson family — I sought out an accessible entry point to serve as my introduction. In the weeks before my start date, I turned to Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson’s memoir, The House by the Side of the Road: The Selma Civil Rights Movement. A swift, engaging read, the book is approachable and informative, detailing Richie Jean's diverse experiences of her upbringing in both the South and the nation’s capital before settling back in Selma, Alabama, and raising a family. Interwoven with her and her family’s personal narratives are stories of the national figures we know and recognize, portraying their individual personalities as well as highlighting the critical roles they played in the Movement as the events of 1965 unfolded in Alabama and across the country.

After reading such an intimate, impactful account, it should not have come as a surprise to me when I began parsing through her papers that Richie Jean had saved so many of her previous drafts. Across some 30 documents, Richie Jean preserved not only the Jacksons’ experience of the events leading up to the 1965 Voting Rights Act, but much of the materials showcasing her writing process as well. As I pored over the collection, I was struck by the ease with which her handwritten notes and outlines flowed into typed drafts with edits in a familiar red pen – a hallmark of many a teacher not to be missed by this lifelong educator.

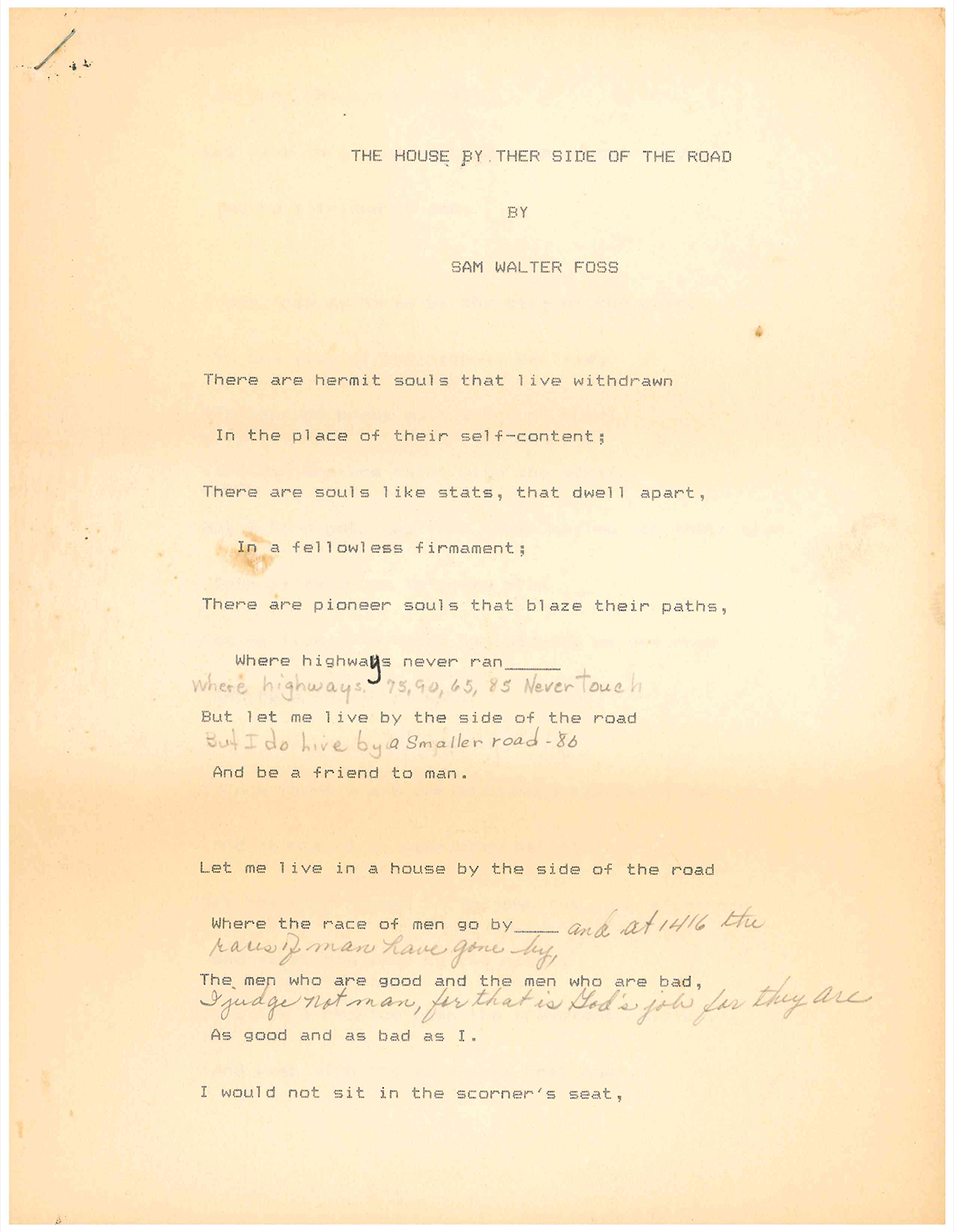

A section of Richie Jean’s favorite poem, Sam Walter Foss’s “The House by the Side of the Road,” intercut with her own verses. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

In dating these documents, we can see that decades passed before the Jacksons began to consider how they would tell their story. One of their earliest creative explorations centers on the 1897 poem for which the book was eventually named: “The House by the Side of the Road” by American poet and librarian, Sam Walter Foss. Here, Richie Jean penned new lines, providing geographic specificity to replace the piece's vaguer verses — lines that better represent her home and the hospitality she provided.

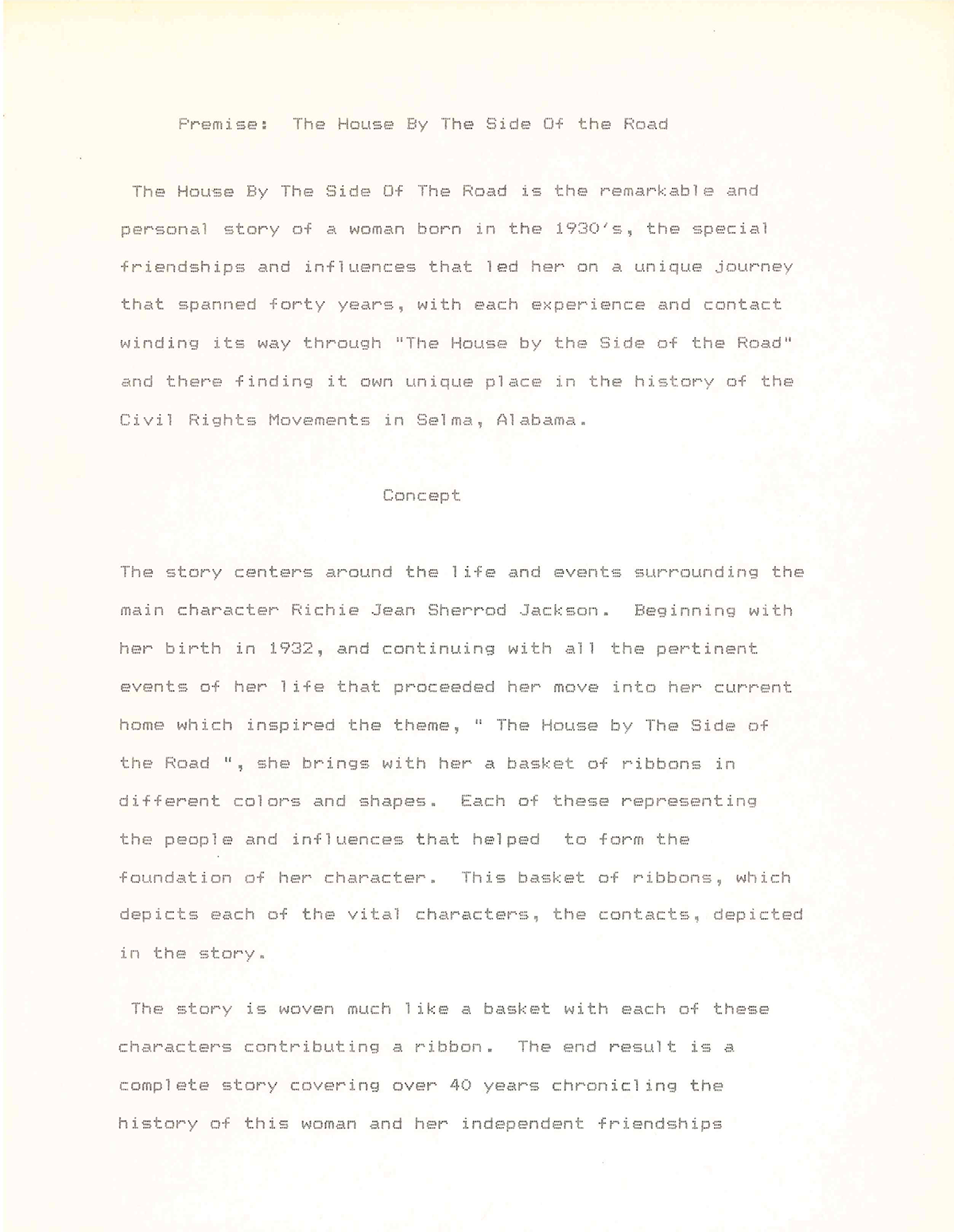

Richie Jean’s draft for a movie or television program based on her life story, 1997. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford

Another instance included a premise, structure, and storyline on Richie Jean’s life were it to be adapted for a TV program or movie, featuring a motif of an empty basket slowly filled with ribbons — collecting a ribbon for each influential figure in her life.

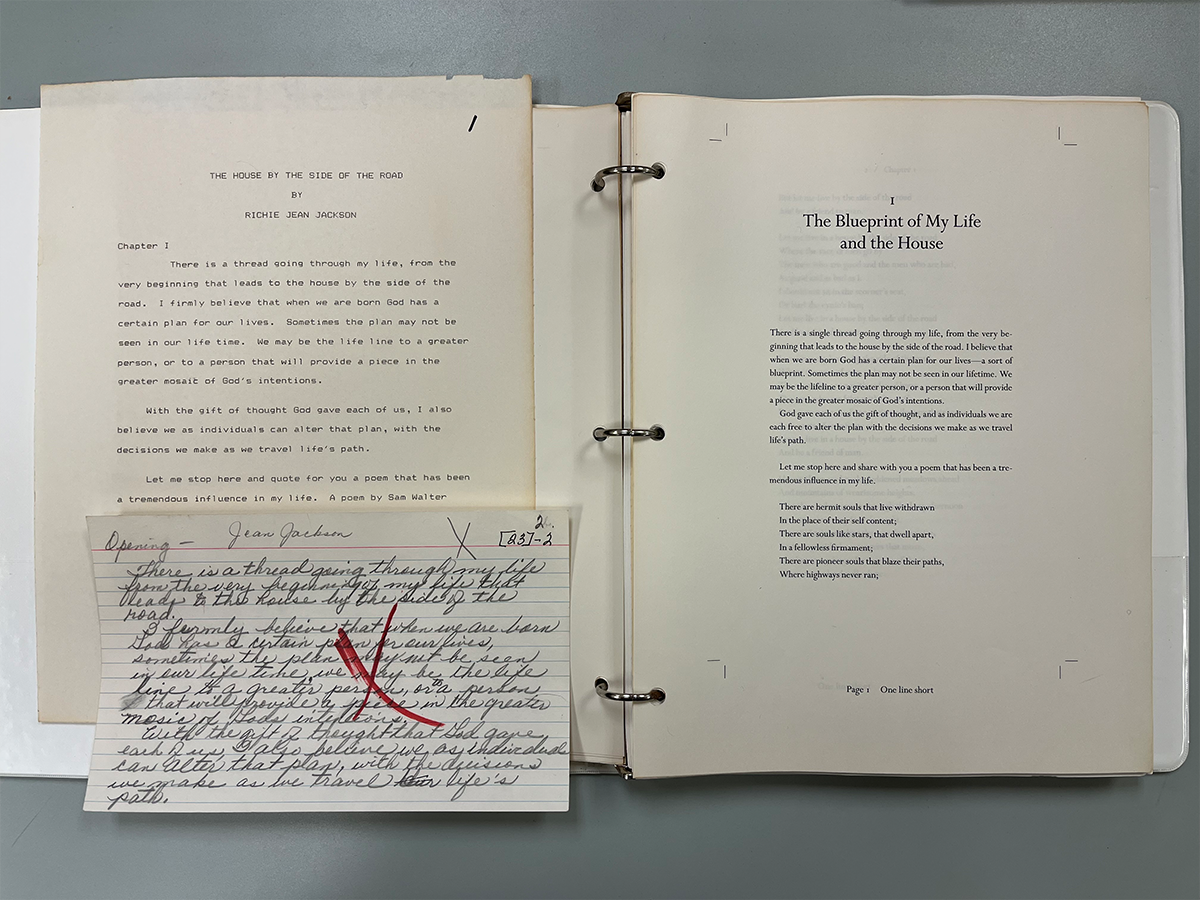

But by 1997, we find the project would take its final form as a book, capturing the history of what went on in their home. Richie Jean wrote out details for events and key figures on dozens of subject notecards as the memories of that time came back to her. Text from these notecards often made its way verbatim into early drafts, as she organized her thoughts into one cohesive narrative. It’s from this point that we see the largest leap in time between materials — the manuscripts jump ahead by a decade from 1999 to 2009 before a date is noted again on a draft.

Richie Jean kept copies of all print and email correspondence with her publisher, the University of Alabama Press, beginning in 2007, when she shared her latest manuscript for their consideration. In 2008, the editing process began in earnest, and drafts were tweaked and trimmed as additional perspectives weighed in. Most of the manuscripts in the collection are from this period — roughly 2008 to 2010—as edited drafts were shipped back and forth between their offices in Tuscaloosa and the Jackson home in Selma. Drafts would implement styling changes for consistency, swap one turn of phrase for another, and eventually plug in the final pieces of front matter: title page, table of contents, dedication, acknowledgements, and copyright.

The opening chapter of The House by the Side of the Road, with text remaining consistent from its original handwritten notecard, to an early typed manuscript page, and the final manuscript. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

The publication of The House by the Side of the Road in 2011 was the culmination of years of effort. So what drove Richie Jean to write it?

The Jacksons had been interviewed many times over the years on their role hosting leaders of the Movement in Selma, but they never sought to leverage those relationships into positioning themselves as leaders and activists. It was only as they saw more and more inconsistencies across other retellings of the history they lived that they were prompted to share their own firsthand account. The cover of The House by the Side of the Road, featuring a photo of daughter Jawana Jackson sitting on the lap of Martin Luther King Jr., made their perspective on the matter abundantly clear — to them, “Uncle Martin” was a friend of the family first, and a national figure second.

The 2015 paperback edition of The House by the Side of the Road alongside the 1965 image featured on its cover of Jawana Jackson and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

The Jackson family’s story shines a spotlight on ordinary people playing a small role in extraordinary moments in history and reminds us of the impact we all can have as well. As Richie Jean writes, “We cannot all be a Martin Luther King Jr., but each and every one of us can make a positive difference in the lives of our families and the people we meet each day. For you see the dream is still alive.”

Jack Schmitt is a Processing Archivist at The Henry Ford.

Women in Service: From the Civil War to WWII

Throughout history, women have served their country during war and in peacetime, on the home front and at the front lines. Since the founding of this country, both military and civilian women contributed to their nation’s cause—whether through active service, or by using their talents and time to support our fighting forces from afar—in ways that were and are often overlooked. Through these objects from the collections of The Henry Ford, we can explore some of these important stories, shedding light on women and their service.

Frances Clayton

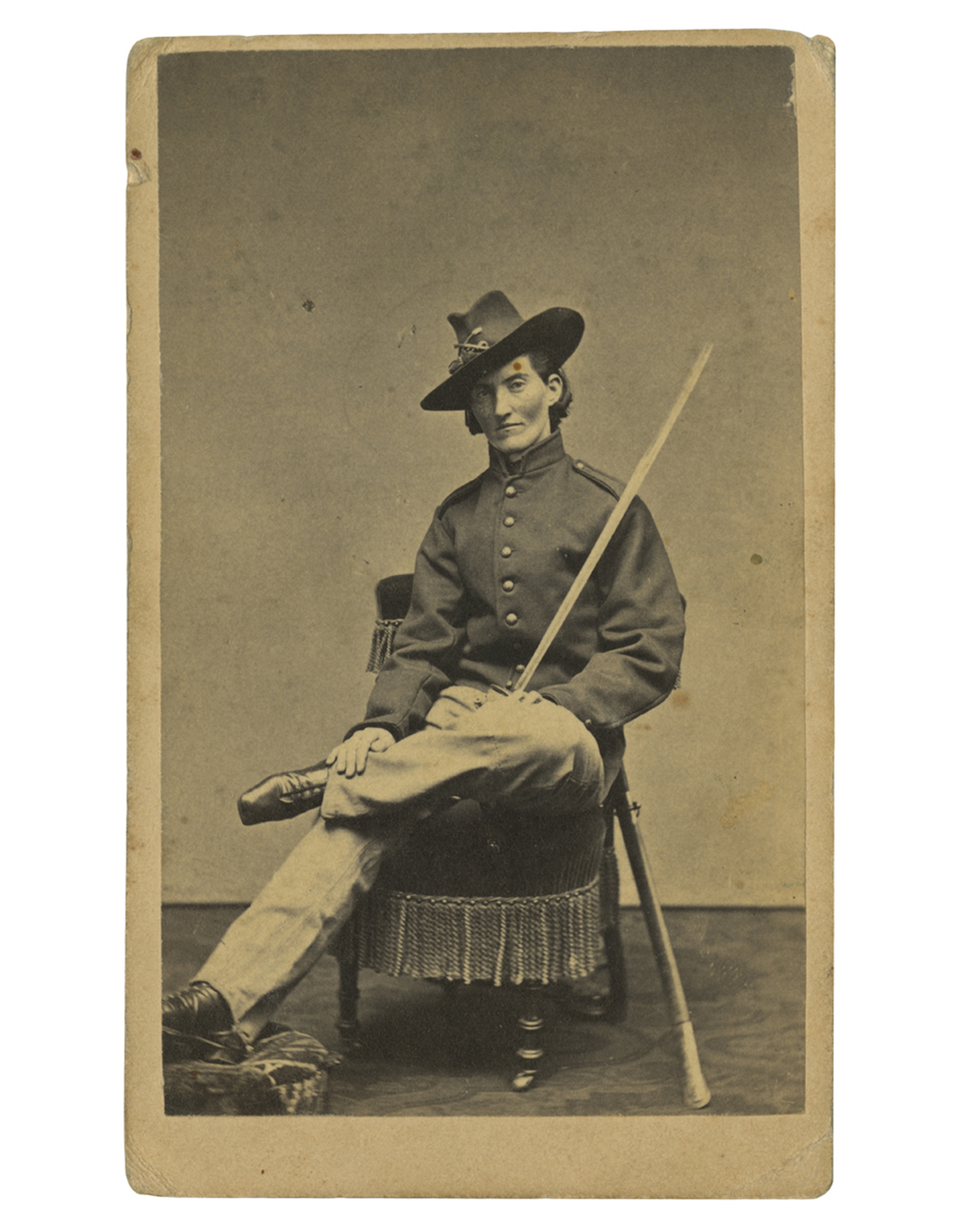

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

Frances Clayton (c.1830-after 1865), who disguised herself as “Jack Williams” to join her husband in the war, posed for this carte-de-visite at Samuel Masury’s studio in Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1865. While some have questioned Clayton’s exact involvement in the war, her images in uniform are probably the most recognized. / THF71763

While women could not officially serve in combat roles in the United States until 2016, women participated in combat as early as the American Revolution—dressed as men.

During the Civil War, hundreds of women concealed their identities to enlist and fight in battles across the country. Their motivations varied: Some wanted to stay close to husbands, brothers, or other loved ones, while others sought to defy societal norms, pursue adventure, or earn a soldier’s pay and enlistment bounty. Patriotism was another driving force—with northern women supporting the Union or abolitionist causes, and southern women joining to support the Confederacy.

At the time, joining the military was easier. With an urgent need for soldiers, physical exams were brief, and no identification was required. A woman could cut her hair, wear men’s baggy clothing, and adopt a male alias. Some were eventually discovered and sent home, others were wounded or killed during service, and others returned home, mustering out at the end of their service.

—Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator

WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps

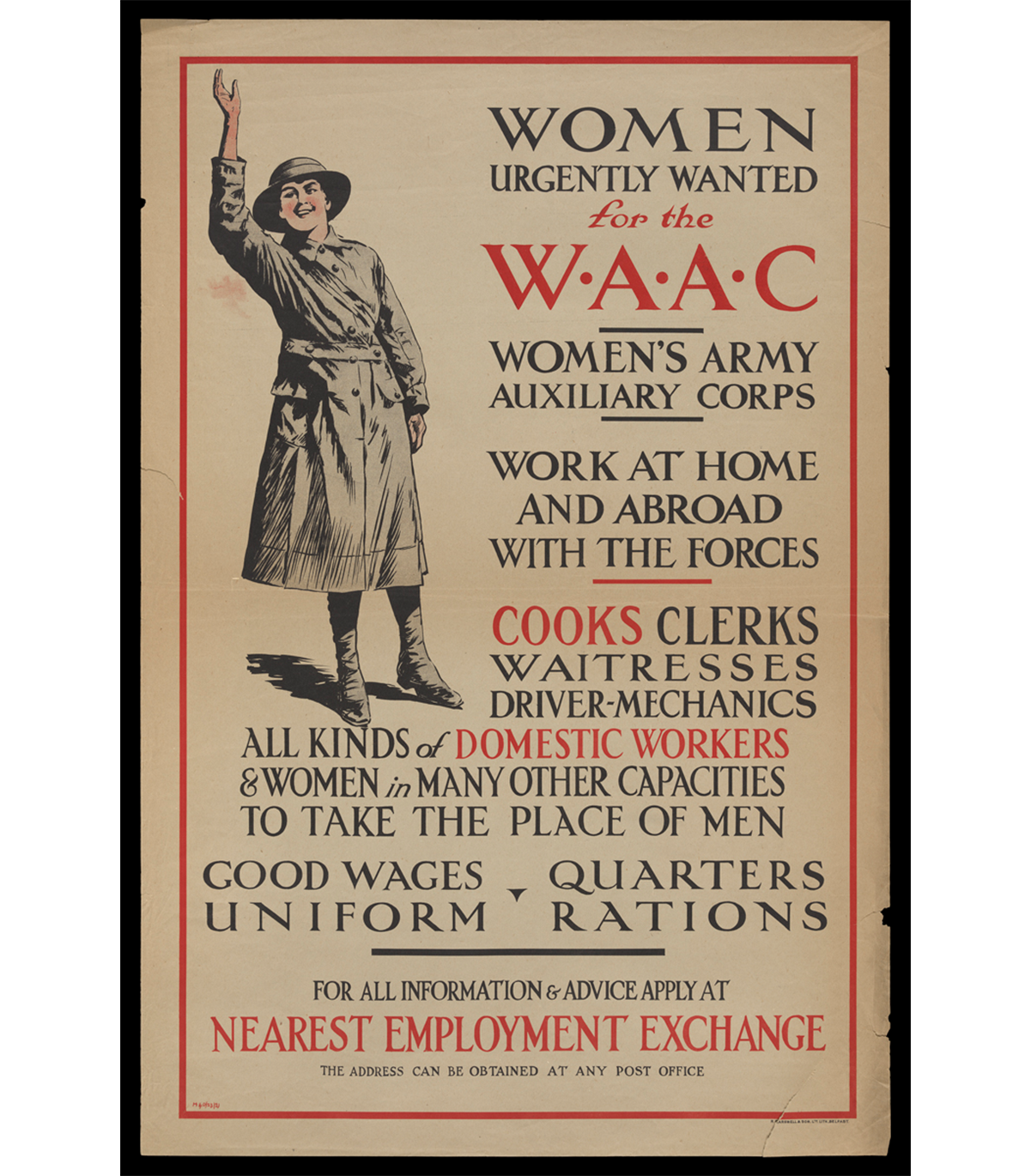

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

“Women Urgently Wanted for the WAAC Women's Army Auxiliary Corps,” circa 1917 / THF726518

Over 50,000 British women volunteered with the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1917 and 1918, the final two years of the First World War. WAAC volunteers took on support roles such as administrative work, catering, or vehicle maintenance at home in the United Kingdom and on the front in France and Belgium. In doing so, WAAC freed up British men on the front from non-combative tasks so the military could focus on the battlefield. This was the first time that women were allowed in the British armed forces in an official capacity outside of nursing.

The corps was renamed Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps in 1918 after Mary of Teck, the queen consort of King George V, became the corps patron. The original WAAC/QMAAC disbanded in 1921, but it inspired women's auxiliary military corps in Great Britain and the Commonwealth and in the United States during the Second World War.

—Kayla Chenault, Associate Curator

“Molly Pitchers”

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

“Molly Pitchers” and Women’s Army Corps recruiter, August 4, 1943. / THF272635

"Molly Pitcher" was the symbolic name given to several historic women who served during the Revolutionary War. These women, usually a soldiers' wife, were noted for carrying water and other provisions to frontline troops. But they became more famous for fighting alongside other soldiers after their husbands or loved ones had fallen in battle.

During the Second World War, August 4, 1943, was designated Molly Pitcher Tag Day. On that day, thousands of women throughout the United States dressed in early American or patriotic costumes and became contemporary "Molly Pitcher" heroines by selling war stamps and bonds. At Greenfield Village, Women's Army Corps recruiters from Detroit, Michigan, and four "Molly Pitchers" came together to raise money for the bond drive, shining a light on women's contributions—whether on the home front or in military service—to America's war efforts since our country's founding.

—Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator

Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

"Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943. / THF65726

Husband-and-wife designers Charles and Ray Eames spent the early years of their partnership experimenting with molding plywood for use in furniture and sculptural objects. In the early 1940s, they used the spare bedroom in their Los Angeles, California, apartment to develop a machine to mold plywood using pressure. A friend, Dr. Wendell Scott of the Army Medical Corps, visited the Eames’ home and saw the potential of molded plywood for the war effort. America’s entry into World War II had created material shortages, including metal. Despite the shortage, metal splints were being used for broken limbs on the battlefield even though they were inflexible and heavy, and worsened wounds in transport.

Upon hearing this, the Eames designed a flexible, lightweight and durable leg splint using the same molded plywood technology they were developing for plywood furniture. They presented their prototype splint to the U.S. Navy and worked with them to further modify and perfect the product. By 1942, the Navy had placed an order for 5,000 splints. The Eames Leg Splint became a successful medical innovation and a design artifact, as well as a critical step in the Eames understanding of molded plywood.

—Adapted from What if Collaboration is Design? Katherine White, Curator of Design

Lillian Schwartz, Nurse Cadet

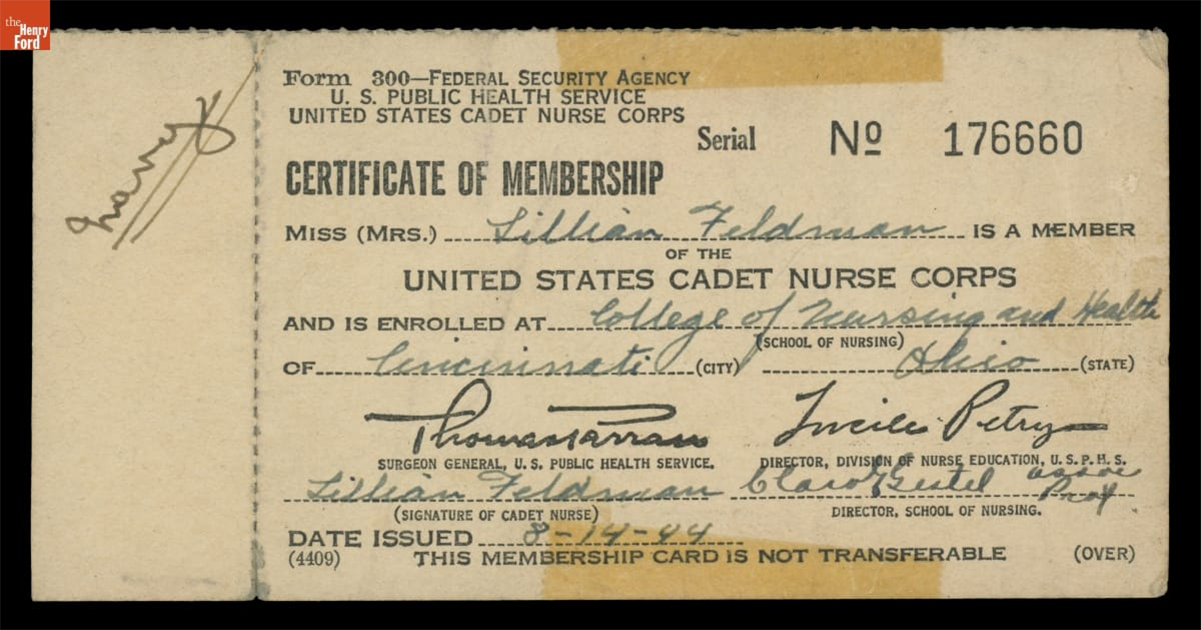

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Certificate of Membership in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps for Lillian Feldman (Schwartz), August 14, 1944 / THF705895

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Schwartz and Jack Schwartz, circa 1946. / THF704693

Lillian Feldman Schwartz (1927-2024) was an American artist who began working at the forefront of computer art and experimental film in the late 1960s at Bell Laboratories. Before her art career was established, however, her life was entwined and impacted by service in the medical field during the last years of WWII, and in its immediate aftermath.

In 1944, when Lillian was 17, she applied to the United States Cadet Nurse Corps—a tuition-free program designed to address the WWII nursing shortage. Lillian did well in her coursework, but she quickly realized that she struggled with nursing people. Despite this, she found ways to bring joy into the Cincinnati hospital where she worked by painting murals in the children’s ward and making plaster sculptures in the cast room. Lillian quickly realized that she was an artist, not a nurse. While working in the hospital pharmacy, she met an intern named Jack Schwartz, whom she would marry in 1946. In 1948, Jack was stationed in Fukuoka, Japan, and Lillian traveled to join him after the birth of her first son. Unfortunately, she developed polio symptoms several weeks after her arrival, and in the post-war aftermath, she was also exposed to the lingering effects of radiation from the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These experiences led to serious health issues throughout her life and were often referenced in her art projects and writing.

—Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

This collaborative blog was written by the staff of The Henry Ford

by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Aimee Burpee, by Rachel Yerke-Osgood, by Andy Stupperich, By Kayla Chenault, by Katherine White

In late 2015 The Henry Ford received a significant donation of studio glass from Bruce and Ann Bachmann of Chicago, Illinois. Already home to a strong historic glass collection — representing glassmaking in America from the colonial period to the mid-20th century — this new acquisition added over 300 works of glass art dating from the late 1950s to the early 2010s.

In October 2016 The Henry Ford opened the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, highlighting the story of Studio Glass movement from its beginnings through to its diffusion into contemporary society. The following summer, the Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass opened in Greenfield Village, showcasing the history of American glass from the 17th century to the present.

Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation (left), and large case of studio glass in the Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass in Greenfield Village (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

With glass in the spotlight, The Henry Ford was looking for ways to maintain the momentum. In 2017 staff from across departments developed the idea of an artist-in-residence program, bringing studio glass artists to work on-site in the Greenfield Village Glass Shop. Over the course of five days, visiting artists would collaborate with The Henry Ford's glassblowers, sharing techniques and styles while creating new, original works.

This was not exactly without precedence. Studio glass pioneer Dominick Labino worked informally in the glass shop in the 1970s, experimenting and practicing after hours. And although current staff members spends much of their time producing items for sale on-site and online, they are also artists eager to create and collaborate.

Visiting The Henry Ford during a glass event, studio glass artists and friends Laura Donefer and Leah Wingfield posed in front of their artwork on display in the museum gallery (left). Laura Donefer works with The Henry Ford’s Josh Wojick in the glass shop (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

The program has proved beneficial, both to the visiting artists and The Henry Ford. Glass shop staff and Greenfield Village visitors have been able to observe the styles and techniques of artists from all over the world. Visiting artists have had access to view the collections for inspiration, and produce multiple works during their residencies, selecting one piece to add to The Henry Ford’s collection.

The first artist-in-residence in summer 2017 was Hiroshi Yamano, a leading figure in Japanese studio glass. He is known for his innovative surface decorations and nature-inspired themes. In a memorable twist, Yamano even completed some of his signature decorative work in his hotel room to bring back to the shop to apply to the glass!

Another highlight that summer was Herb Babcock, professor emeritus in the glass program at Detroit’s Center for Creative Studies. Many glassblowers who have worked at Greenfield Village through the years were former students of Babcock.

Note the elements from nature – fish and flower – along with the applied surface decoration in this piece created by Hiroshi Yamano (left). Herb Babcock played with colors to create this vase (right). / THF180564 (left), THF180561 (right)

In 2018 four artists participated in residencies — Giles Bettison, Laura Donefer, Davide Salvadore, and David Walters, followed by three — Dean Allison, Robin Cass, and Shelley Muzylowski Allen — in 2019.

Shelly Muzylowski Allen’s “Chalcedony Bear” is a swirl of colors imitating quartz (left), and Robin Cass's “Aureate Scarlet Tenax” evokes botanical or biological specimens (right). / THF177784 (left), THF177787 (right)

In 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic forced suspension of the program for two summers.

The program resumed in 2022, but on a smaller scale, with only two residencies. That year, Ben Cobb and the husband-and-wife team Michael Schunke and Josie Gluck brought their talents to the glass shop. Jen Elek and Kelly O’Dell followed in 2023. In the summer of 2024 James Mongrain created a Venetian-inspired vessel topped with a seahorse, and Jack Gramann used the human portrait as a motif in his work.

“65 Million Years” by Kelly O’Dell, 2023 (left), Ben Cobb’s “Maple Spinner” from 2022 (center), and Jack Gramann’s “Human Face” from 2024 (right). / THF370839 (left), THF370282 (center), THF802223 (right)

In May 2025 The Henry Ford finally welcomed Nick Mount, a veteran glass artist from Adelaide, Australia. Originally scheduled for 2020, his residency was delayed due to the pandemic. A leader in Australia’s Studio Glass movement since the 1970s, Mount was first inspired by American artist Richard Marquis, who introduced Venetian glass techniques at art schools in Australia. Inspired to pursue glass, Mount toured Australia with Marquis, demonstrating blown glass. With funding from the Crafts Board of the Australia Council, he was able to study glass in the United States and Europe.

In 2022 a case was added to the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery to display a selection of artist-in-residence pieces, along with an interactive video to “meet the artists” (left), while in 2024 additional artist-in-residence pieces were selected to be displayed in the wall case in the Greenfield Village glass shop (right). / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

After returning to Australia, Mount has balanced creating functional glass objects for retail with creative artworks that have found their way into private collections and museums around the world. For over 50 years Mount has made significant contributions to the art form through both his work and teaching.

Images of Nick Mount working in the Greenfield Village Glass Shop in May 2025. / Photos by Staff of The Henry Ford

As part of the artist-in-residence program, The Henry Ford’s Media Relations and Studio Productions team film the artists at work and conduct one-on-one interviews to preserve their stories and work and document their thoughts on artistic practice.

Within the Bachmann donation there was already one piece made by Nick Mount in The Henry Ford’s collection, Scent Bottle #101200, made in 2000 (left). Nick Mount’s in-process artwork for THF’s collection (right). / THF803684 (left), photo by Staff of The Henry Ford (right)

Boyd Sugiki (left) and Lisa Zerkowitz (right). / Image courtesy of Two Tone Studios

In July 2025, the owners of Two Tone Studios in Seattle, Washington — Boyd Sugiki and Liza Zerkowitz were in residence July 28~August 1, 2025. Raised in Hawaii, Boyd Sugiki earned his BFA in glass at the California College of Arts and Crafts. Lisa Zerkowitz, a California native, received her BA in Studio Art from the University of California at Santa Barbara. In 1995 while pursuing MFAs at the Rhode Island School of Design, the two began blowing glass together. They founded Two Tone Studios in 2007 and have taught at universities across the U.S. and internationally. Like Nick Mount, their original residency was postponed from 2020.

The artist-in-residence program strongly aligns with The Henry Ford’s mission to provide “unique educational experiences based on authentic objects, stories, and lives from America's traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation.” There are even thoughts about expanding the program to other areas of Liberty Craftworks — weaving, pottery, and printmaking. Stay tuned!

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The Early History of Hip-Hop in Three Flyers

New York City was experiencing a time of turmoil from the late 1960s through the 1970s. The city, especially in the outer boroughs, was in depth of recession; urban renewal policies had harmed predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Youth gangs took to the street as the result of a lack of community resources, jobs, or third spaces for leisure. Out of this chaos, hip-hop rose from the Bronx. Young people created this culture at block parties, parks, and clubs. These gatherings were usually advertised with homemade street art-inspired flyers like the ones recently acquired by The Henry Ford. They offer a glimpse into the history of not just a musical genre but a movement.

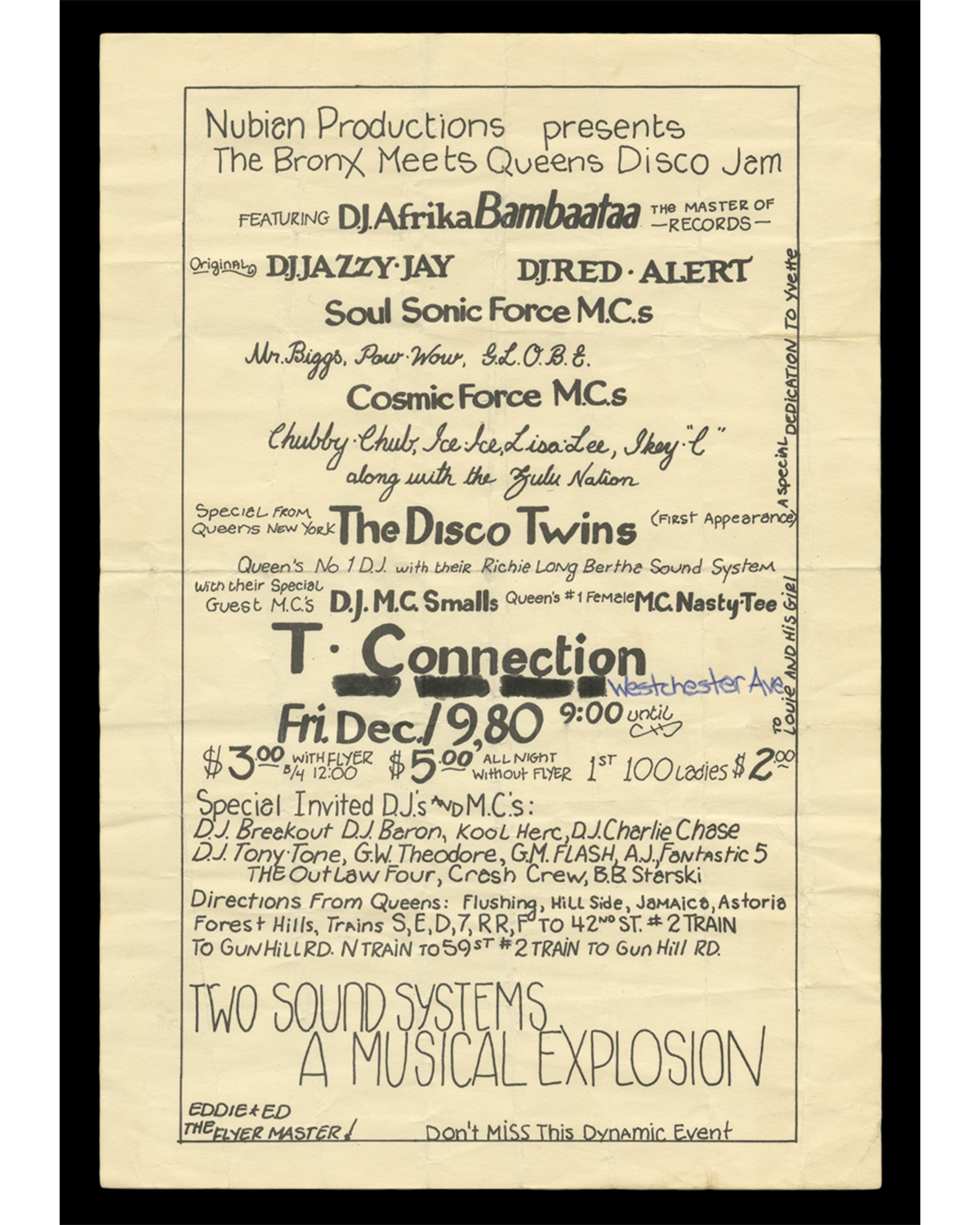

"The Bronx Meets Queens Disco Jam Featuring DJ Afrika Bambaataa," 1980. / THF721980

"The Bronx Meets Queens Disco Jam Featuring DJ Afrika Bambaataa," 1980. / THF721980

In the early days of hip-hop, the disk jockey, or DJ, was the star of the show; their ability to create the atmosphere for a party is what made them, and hip-hop itself, unique. As hip-hop grew in popularity, DJs who were fixtures at neighborhood gatherings were invited to play in clubs for special nights. Among the most prominent of these clubs was a discotheque in the Williamsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx called T-Connection. DJ Flame, who performed as DJ La Spank in the 1980s, called the T-Connection the Apollo Theater of hip-hop in a 2023 interview. To her, T-Connection was a training ground for young DJs to hone their craft in front of audiences who expected greatness. T-Connection also featured hip-hop luminaries. DJ Kool Herc, who is considered one of the founders of hip-hop, often played there with his emcees, the Herculoids. DJ Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation were considered the unofficial in-house crew of T-Connection due to their frequent performances.

DJ Kool Herc at a nightclub, Bronx, New York, circa 1981. He is pictured in a nightclub, possibly T-Connection. / THF191960

DJ Kool Herc at a nightclub, Bronx, New York, circa 1981. He is pictured in a nightclub, possibly T-Connection. / THF191960

To be the center of a party, DJs cultivated large and mostly secretive libraries of vinyl records spanning soul, funk, disco, electronic, and rock music genres. Early hip-hop DJs focused on the breakdown or "breaks," the portions of a song where the percussion or rhythm sections of a band would do a solo. This was considered by many to be the most danceable part of a song. Some DJs, like Kool Herc or Grandmaster Flash, would extend the "breaks" in songs using two copies of the same records and playing them in succession, sometimes called the "merry-go-round" technique. You can hear the T-Connection audience’s response to DJs' hard work in surviving bootleg recordings of performances. At clubs like T-Connection, DJs demonstrated their prowess on the turntables and spread hip-hop across New York City and the world.

"A Master Mix Rappers Battle," 1984. / THF721983

"A Master Mix Rappers Battle," 1984. / THF721983

What is now called rapping has deep roots in Black American culture and in other parts of the African diaspora. Everyone from jazz band leader Cab Calloway to the poetry collective The Last Poets spoke rhythmically over music in styles similar to hip-hop emcees. Caribbean "toasting" songs were also foundational to rapping; in "toasting," Jamaican DJs spoke in a sing-song tone over the records that they played at parties or on the radio. Traditions like these influenced DJs, including Kool Herc, to bring their friends, e.g. Coke la Rock and Clark Kent, to join them and rap while the DJ played music.

These early emcees were masters of ceremony at parties; they would rhyme over a few bars of music to hype up a crowd or tell someone that their car was double parked. This is why many early rappers included the moniker "MC" in their names. From this came a culture of braggadocious and sometimes insulting raps pointed at rival emcees who played at the same events or venues: battle rapping. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, rap battles, like "Master Mix Rappers Battle," were promoted to draw crowds to clubs. The crowds' response — applause, cheers, jeers, and boos — determined the winners of these battles. Some of the top-billed emcees who participated in the "Master Mix Rappers Battle" were or would soon become famous. The Cold Crush Brothers were already legendary by 1984. The crew battled the Grand Wizzard Theodore and the Fantastic Five at Harlem World in 1981. This performance is considered one of the first important rap battles in hip-hop history. Bootleg recordings of the battle were distributed among young hip-hop enthusiasts and inspired aspiring emcees such as Darryl McDaniels, DMC of Run DMC. In 1982, the Cold Crush Brothers re-created the Harlem World battle for the big screen in a film called Wild Style.

Members of the Treacherous Three influenced the changing sound of hip-hop over the next decade. Emcees Kool Moe Dee and Spoonie Gee were forefathers of the subgenres New Jack Swing and Gangsta Rap, which both grew in popularity during the late 1980s and early 1990s.Master Don and the Committee — sometimes billed as Masterdon Committee or Death Committee — did not achieve the same level of fame as their competitors. After scoring a New York City radio hit with their song "Funkbox Party" in 1983, their success remained mostly localized. However, they were innovators as one of the first mixed-gender rap crews with the inclusion of DJ Master Don's sister, Pebblee Poo.

"A Birthday Party for the Lovin' Trouble," 1983. / THF721984

"A Birthday Party for the Lovin' Trouble," 1983. / THF721984

Hip-hop is not just a music genre; fashion has been baked into the culture since the beginning. There are many examples of the symbiotic relationship between hip-hop and style. Artists have started fashion labels like Roc-a-Wear, and emcees often call out their favorite brands in their lyrics like in "My Adidas" by Run DMC.

Early in hip-hop's development, there seemed to be a divide in the culture about how to dress. On the one hand, the young working-class Black and Puerto Rican audience would wear street styles from brands that they had already in their closet, like Kangol or PRO-Keds. They might add personalized touches to their outfits such as permanently creasing their jeans. If they were a dancing b-boy or b-girl, they might rep their dance crew by wearing uniform clothes.

PRO-Ked "69ers" Shoes, Worn by DJ Kool Herc, circa 1980. In hip-hop's early days, PRO-Ked basketball shoes were the sneakers of choice for DJs, emcees, and audiences alike. PRO-Ked shoes were so common among Black and Hispanic youths in the Bronx that the shoes were nicknamed “Uptowners,” referring to the borough’s location./ THF191954

PRO-Ked "69ers" Shoes, Worn by DJ Kool Herc, circa 1980. In hip-hop's early days, PRO-Ked basketball shoes were the sneakers of choice for DJs, emcees, and audiences alike. PRO-Ked shoes were so common among Black and Hispanic youths in the Bronx that the shoes were nicknamed “Uptowners,” referring to the borough’s location./ THF191954

On the other hand, there was the influence of discotheque culture. In the disco clubs, it was common for people to dress in their finest and most eye-catching apparel. For those who bridged the disco and hip-hop worlds, the glamorous get-ups were more appealing. DJ Hollywood — one of the first people to rap rhythmically over music and influence early emcees — enforced a strict dress code wherever he performed. At a DJ Hollywood party, streetwear and sneakers were strictly prohibited.

Women's "Lombada Hi Bright" Pumps, 1980-1990. Low-heeled shoes like these were popular from the 1970s until the 1990s as nightclub culture developed. The lower center of gravity made the shoes easier to dance in. They exemplify what a fashionable partygoer might wear. / THF65284

Women's "Lombada Hi Bright" Pumps, 1980-1990. Low-heeled shoes like these were popular from the 1970s until the 1990s as nightclub culture developed. The lower center of gravity made the shoes easier to dance in. They exemplify what a fashionable partygoer might wear. / THF65284

During the 1980s, many emcees and DJs embraced luxury fashion as they gained fame. For example, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five performed in elaborate leather outfits, purported to cost over $1,000 each. One fashion pioneer, Harlem-based Daniel "Dapper Dan" Day, noticed this trend and opened his boutique Dapper Dan of Harlem in 1982. He designed custom clothes made of leftover materials from haute couture brands like Louis Vuitton. Dapper Dan blended street fashion and high fashion; he prominently displayed brand name logos on his clothing and innovated the concept of "logomania" in fashion.

These three flyers represent just some of the many stories that transformed hip-hop into the cultural phenomenon it is today. If you are interested in seeing more party and event flyers from this era of hip-hop, check out Cornell University Library's hip-hop collection.

Kayla Chenault is the Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Enriching Our World

The Henry Ford is more than just a tourist attraction, more than just an institution, and more than just a summer stroll. Rather, it is a reflection — a curtain, even — for the horizons of a greener future that are closer at hand than many realize. It may feel a bit tawdry to some to personalize the planet, but it is an indisputable fact that the Earth does a lot for us that we do not recognize often enough. And just as a body must be well kept or a machine well maintained, so too should we endeavor to do our part in rejuvenating the groundsand gardens of The Henry Ford that have so delighted guests and employees.

To fuel this effort, in 2024 The Henry Ford made one of its biggest leaps forward into the frontier of sustainability with a new addition to help the management of Stand 44’s restaurant waste. The CX5 Harp Renewables Bio-Digester is a specialized piece of equipment that creates and manages a meticulously designed internal environment, aimed to yield the most efficient breakdown of food waste and biodegradable material into a soil supplement rich in essential plant nutrients. While it sounds interesting enough on its own, the logistical details are equally compelling, and the journey for a handful of food waste from when it’s disposed of to its reintroduction to the soil takes time and teamwork. It passes through many processes before it ends up in a regenerative garden, including:

Phase 1 – Collection

Waste that is disposed of by staff and guests is collected and then sorted by hand to prevent contamination. This is where guests and staff make the biggest impact to ensure the efficient and sustainable operation of the biodigester. Meanwhile the food service team continues to phase out single-use plastics in favor of biodegradable packaging. Conscientiously disposing of personal waste contributes more than many may realize.

Stand 44’s waste composting method, which makes use of an industrial biodigester, was a key element of the venue's 4-star GRA certification. / Image by The Henry Ford

Phase 2 – Feed the Machine

Believe it or not, the biodigester is a picky eater. It prefers a healthy mix of waste: dry (biodegradable utensils, plates, bones, breads etc.) and wet (vegetables, fruits, dairy products, grounds, plant scraps, etc.). A carefully considered recipe is constantly being improved upon by food service operation to ensure the most effective operation and high-quality output possible. With the careful manipulation of moisture, heat, and bacteria, this chemistry trifecta of natural digestion taken to its technical limit can break organic waste down into an odorless pathogen-free and high-nutrient soil amendment in as little as 24 hours.

Stand 44's Bio Digester during installation. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Stand 44’s Biodigester Interior. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Phase 3 – Addition

As an extra layer of complexity and to seize an even grander opportunity for sustainability, The Henry Ford is committed to treating the end product digestate from the biodigester as just one of the key ingredients in a much larger upcoming campus-wide hot composting initiative that endeavors to turn all of The Henry Ford’s yard and animal waste into fertilizer on-site.

Digestate Aggregate Pile. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Phase 4 – Return

The resulting material after the completion of the compost cycle is regularly tested to maintain state and federal safety standards. After which comes redistribution to various gardens and fields, where it can be mixed and tilled as needed for the future. Ideally, if all goes well, this compost can help in the on-site production of fruits and vegetables to be used by food services.

Experimental compost pile. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

It takes many hands not only to complete this upcycling circle, but also to support The Henry Ford’s mission to promote a more sustainable approach to its commitment to providing unique educational experiences so that we may have a better future.

Successful Compost Testing on Trailing Pink Coleus. / Image courtesy of Aias Danier, Construction Management Sustainability

Aias Danier is Assistant Construction Manager at The Henry Ford. Alec Jerome is Director of Facilities Management.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation that forever changed the lives of many people of color in the United States and set the course for other groups to pursue their full rights as citizens. Yet, despite the successful legislation, many Black people and other people of color across the United States, particularly in the South, continued to be denied the right to vote.

“Do All Americans Have the Right to Vote?” An address by Barry Bingham, April 9, 1939. / THF289023

Do all Americans have the right to vote?

This question has been a concern for decades, particularly before the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The 15th Amendment prohibits voting discrimination based on race, yet barriers still existed at that time that limit access to voting. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses made it all but impossible for many groups of people to exercise the rights granted to them in the 15th Amendment — rights that were repeatedly violated.

Grassroots organizing had begun in many areas in the South, and Selma, Alabama, became the center of the movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) worked to register people to vote there for months in 1965. Their work did not go unnoticed. Soon, major players in the movement, such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, were making their way to Selma. The fight for voting rights eventually led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Local groups in the Selma area were also doing the hard work. Members of the Dallas County Voters League, known as the Courageous Eight, worked to register people to vote in Dallas County, Alabama. Though they were told multiple times to cease their activities, they did not. These community leaders were committed to securing the vote for themselves and their community.

The figures of the voting rights movement go beyond the names you may already know. Nationally recognizable figures depended on local activists—everyday people who put their lives and livelihoods on the line. One such family, the Jacksons of Selma, rose to the occasion by opening their home to provide shelter, nourishment, and peace, all while putting their personal safety at risk. Their sacrifice helped to create a safe space for the movement’s leaders to strategize and rest.

Pajamas worn by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. while at the Jackson’s Home. / THF802666

Mrs. Richie Sherrod Jean Jackson took pride in ensuring that her guests felt comfortable and welcomed. Dr. Jackson provided Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with pajamas, and Mrs. Jackson fueled the movement with nourishment. The Jackson’s young daughter, Jawana, would listen to the stories her Uncle Martin would tell. But the family did more than provide a haven. They became involved civically as well.

In November 1958, Dr. Sullivan Jackson testified before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Established as part of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the commission investigated voter discrimination. The hearings were held over a period of two months, between 1958 and 1959. The Commission had several people testify, including Dr. Jackson, who spent hours preparing for his testimony. The Commission assumed the responsibility of voter registration, with a focus on Alabama. Speaking out had its own set of hardships. The Jacksons and others who testified often faced economic repercussions.

“Life” Magazine, March 19, 1965. / THF715919

Voting is a fundamental right. In the United States, this concept has been ignored more than once. The denial of voting rights to people of color across the country came into sharp focus in March of 1965 in Selma, Alabama. After March 7, 1965—known as Bloody Sunday—Dr. King called for clergy members to go to Selma. Clergy, including Rabbi Abraham Heschel and Rev. James Reeb, among many others, answered the call. On March 15, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed the nation and instructed Congress to introduce and pass a Voting Rights Act.

Two days after President Johnson gave his “American Promise” speech, on March 17, 1965, the Voting Rights Act was introduced into Congress. The Senate began its debate on the bill on April 22. Eventually, the Voting Rights Act was passed after much debate, and President Johnson signed it on August 6, 1965. Thus, it enshrined the enforcement of the 15th Amendment and ensured that no one was denied the right to vote.

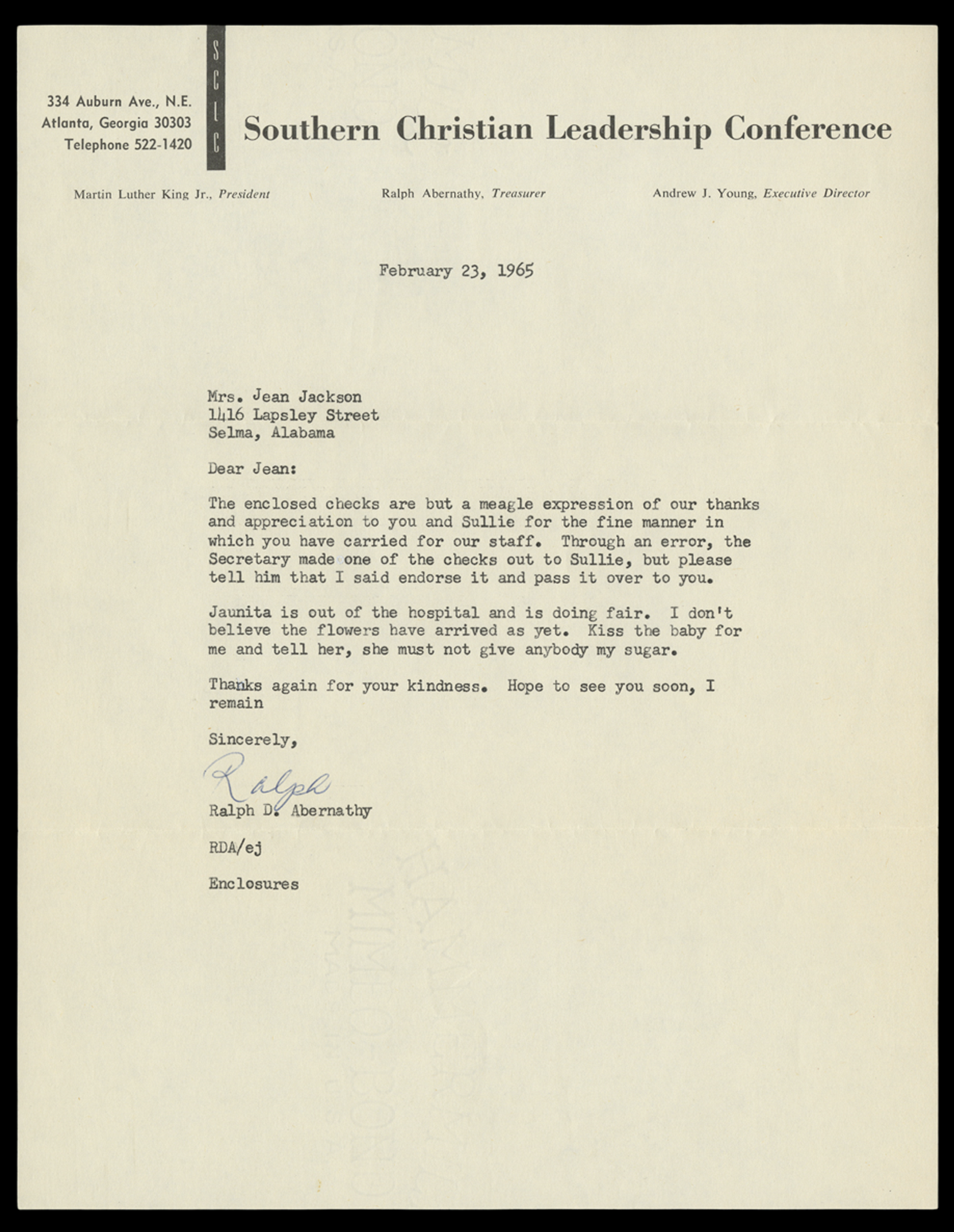

Letter from Rev. Ralph Abernathy thanking her for opening her home to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. / THF721760

While the Jackson House remained a family home at its core, it also offered refuge and peace during a time of great turmoil. While in Selma, Dr. King stayed with the Jacksons. Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a member of the leadership team for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, sent Mrs. Jackson reimbursement and letters of gratitude. The Jacksons provided crucial hospitality and support, even if it meant putting their own lives at risk.

As we celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, it is essential to remember all those who were involved in the process.

Are you registered to vote? To find out if you are registered or to register, please visit the following websites:

Michigan Residents

To Check Your State

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford.

Thunderbird Soars at Motor Muster

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Once again Father’s Day weekend brought a favorite event to Greenfield Village. Our 2025 Motor Muster, held June 14-15 and celebrating car culture from 1933 to 1978, featured more than 650 automobiles, trucks, motorcycles, military vehicles, and bicycles. Each Motor Muster features a special theme, and this time our spotlight fell on the Ford Thunderbird, seventy years after the sporty personal car was introduced for the 1955 model year. Thunderbird was a hit over eleven different styling generations through 2005, taking only a brief pause in production from 1998 to 2001.

Detroit Central Market housed Thunderbirds from seven of the car’s eleven styling generations, including a couple of post-1978 examples. / Image by Matt Anderson

We wanted to showcase Thunderbird properly, so our friends at the Water Wonderland Thunderbird Club and the Vintage Thunderbird Club International helped us pull together a selection of some of the best T-Birds pull together a display in Detroit Central Market featuring some of the best T-Birds ever built Detroit Central Market. We had cars from seven of Thunderbird’s eleven generations. Together, they represented the original two-seat “Little Birds” of the mid-1950s, the four-seat “Square Birds” of the late 1950s, the angular “Bullet Birds” of the early 1960s, and the larger luxury-focused Thunderbirds of the early 1970s. From The Henry Ford’s own collection, we included our 2002 Ford Thunderbird, serial number one from the final generation, and our 1962 Budd XT-Bird, which Budd pitched to Ford in hopes of reviving the partnership that had Budd building body components for two-seat T-Birds several years earlier. Our 2002 model wasn’t the only post-1978 T-Bird in the show. We also included a 1994 Thunderbird representing the model’s tenth generation.

Thunderbird Jr. kiddie cars were built in cooperation with Ford from 1955 to 1967. / Image by Matt Anderson

There was another big—make that small— feature in Detroit Central Market. Fourteen Thunderbird Jr. cars added to the fun. Built in Mystic, Connecticut, with the blessing of Ford Motor Company, the Thunderbird Jr. was a scaled-down version of the real thing powered either by an electric motor or a single-cylinder gasoline engine. The junior cars were updated each year to match the look of the real T-Bird, and paint colors were all factory-correct. Smaller Thunderbird Jr. cars, roughly one-quarter size, were intended for children and either given away by Ford dealers or sold by high-end retailers like FAO Schwarz. Larger versions, about one-third size, were used at carnivals and amusement parks. About 5,000 Thunderbird Jr. cars were produced from 1955 to 1967. The fourteen examples at Motor Muster may have been the largest gathering of these little cars since the factory closed nearly sixty years ago.

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

From the Armington & Sims Machine Shop to the Daggett Farmhouse, Greenfield Village was packed with historic vehicles. A visitor might easily spend all day walking around to see everything. But for those who preferred to let the show come to them, we offered pass-in-review programs throughout the weekend. As spectators relaxed on shaded bleachers, expert narrators offered insights and expertise on participating vehicles that rolled through in a steady chronological parade. While most of these presentations were organized by decade, we had special sessions devoted to commercial vehicles, race cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and —of course— Thunderbirds.

The cars were complemented by a variety of musical performances and historical vignettes. At Town Hall in the heart of the village, the Village Cruisers offered a selection of 1950s vocal pop perfect for the chrome-and-tailfins era. At the same location, Larry Callahan and the Selected of God Quartet sang stirring freedom songs from the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Their performance offered a wonderful preview of programming to come with the opening of the Jackson Home next year. The 1970s came alive through the Mach I band as they played classic rock hits both at the gazebo near Ackley Covered Bridge and in a larger Saturday evening concert on Main Street.

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pedal-powered transportation is in vogue at The Henry Ford thanks to Bicycles: Powering Possibilities, a temporary exhibit now on view in the Collections Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. There were many bikes to enjoy at Motor Muster, from an eccentric-hub Ingo-Bike like this one in the museum’s collection, to an early 1970s Schwinn Twinn tandem that allowed two cyclists to ride together. And just as Motor Muster vehicles need not be motorized, they don't have to travel on land either. We celebrated outboard boating’s golden age on the shores of Suwanee Lagoon. The fascinating display of boats and engines was titled “Tailfins and Two-Tones,” reflecting a couple of 1950s design fads that were found on land and sea alike.

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

As is tradition, Motor Muster ended on Sunday with our awards ceremony. We presented trophies to vehicles from each decade based on popular-choice ballots submitted by show participants and visitors. We also gave Curator’s Choice prizes to a pair of unrestored vehicles. This year’s unrestored winners included, fittingly, a 1966 Ford Thunderbird and a 1974 Ford Gran Torino. The full list of 2025 Motor Muster winners is available here. The ceremony put a perfect cap on another wonderful weekend.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

On November 8, 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered electromagnetic radiation, or invisible light, which he dubbed x-rays; immediately they became a huge fad, used for everything from photographic filters to miracle cures for a variety of ailments. X-rays bridged the gap between the public's interest in scientific advancement and commerce. One fascinating artifact in The Henry Ford's collection demonstrates the X-ray craze well: a shoe-fitting fluoroscope.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. X-Ray Shoe Fitters, Inc., a subsidiary of the Adrian Company of Madison, Wisconsin, was one of largest manufacturers of shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and made this X-ray. / THF803832

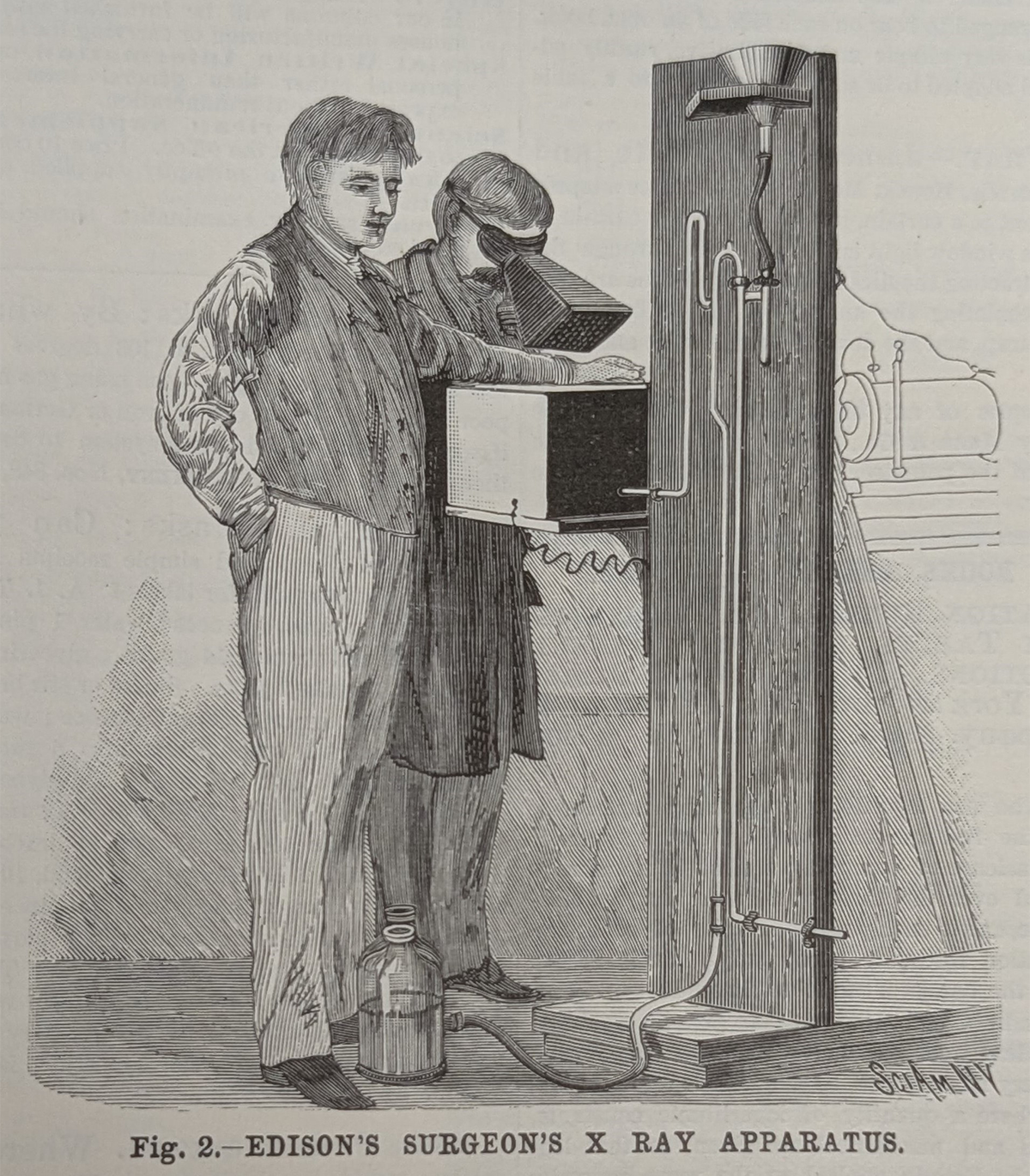

Fluoroscopes are real-time, continuously moving X-ray images — like an X-ray movie. Thomas Edison created the first commercially available fluoroscope in 1896 by adapting the basic principle of static X-rays.

Illustration from Scientific American announcing Edison's fluoroscope in April 1896. / Photo by Staff of The Henry Ford.

X-rays are beams of invisible light moving in short wavelengths, which pass through objects and create negative images of them on a fluorescent screen. What you see in the negative image depends on how much radiation an object can absorb. More dense objects like bones absorb more radiation, so they show up as white on an X-ray picture; less dense objects like muscle tissue absorb less radiation, so they show up as dark on an X-ray picture. Edison's fluoroscope allowed people to look at their bones in real-time when they placed their bodies between a cathode tube that made X-rays and a fluorescent screen that displayed the images created.

Box of fluoroscope Slides, 1895-1905. / THF157985

In the early days of fluoroscopy, they were primarily used in hospitals or as novelties. In 1919, Jacob Lowe, owner of a Boston-based X-ray laboratory, filed a patent for the first fluoroscope explicitly for fitting shoes. Lowe saw the problem of ill-fitted shoes causing discomfort in the short term and foot deformities in the long term; his machine would allow the customers to see their feet inside of their shoes and would presumably prevent future issues.

Shoe-fitting fluoroscope, circa 1936. To use a shoe-fitting fluoroscope, customers would stand on this side of the X-ray and put their feet in the chamber at the bottom. / THF803822

To use Lowe's fluoroscope, customers placed their feet on the enclosed platform where the X-ray tube was and looked through one of the fluoroscope's viewfinders to check their feet on the fluorescent screen. The three viewfinders also allowed simultaneous observation: for example, a salesperson, a child trying on shoes, and the child's parent.

Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, circa 1936. A customer could see a fluoroscope of their feet from the viewing chamber above. / THF803831

The patent was granted in 1927, and Lowe assigned the patent to the Adrian Company in Madison, Wisconsin, which began manufacturing shoe-fitting fluoroscopes in 1922. For the next thirty years, shoe-fitting X-rays became ubiquitous in shoe stores across the world.

Did X-raying feet actually help customers and store employees fit shoes? In the 1990s, a former shoe shop clerk was interviewed about shoe-fitting fluoroscopes and revealed that the machines did not help him properly size customers. Additionally, he did not know any salespeople who felt the machine truly helped them. Shoe-fitting fluoroscopes were essentially a marketing gimmick that incentivized customers to buy shoes.

During the 1920s, businesses began to focus on ways to drive consumer habits through driving demand. For example, Charles Kettering of General Motors championed the idea of selling "newness" to customers in his 1929 essay "Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied": "If everyone were satisfied, no one would buy the new thing because no one would want it […] You must accept this reasonable dissatisfaction with what you have and buy the new thing, or accept hard times." Kettering's philosophy was pivotal to understanding why fluoroscopes were popular among shoe sellers. Even the Adrian Company's shoe fitting X-ray manual touted the unverified statistic that 75% of people wore shoes too small for them and therefore needed new shoes. That statistic could be repeated to customers to bolster dissatisfaction and drive sales. Additionally, there was a perception that using fluoroscopes was a necessary form of consumer safety. The "see for yourself" nature of the fluoroscope created the illusion of an "objective" way for salespeople to determine if new shoes were necessary.

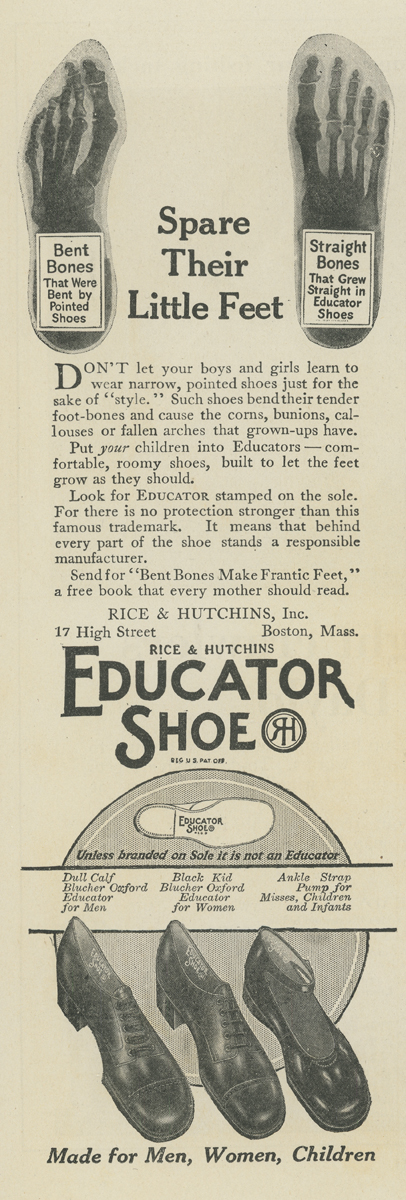

"Spare Their Little Feet," 1917-1921. / THF723224

The fluoroscopic sales tactic was used on women especially by playing into the idea of "scientific motherhood." At the beginning of the 20th century, there was an increasing expectation that women needed the latest technological advancements and advice to raise their families correctly. The concept of "scientific motherhood" was utilized to great effect in advertising, where companies marketed their products with sometimes-dubious claims of "expert approval" or "rigorous scientific testing."

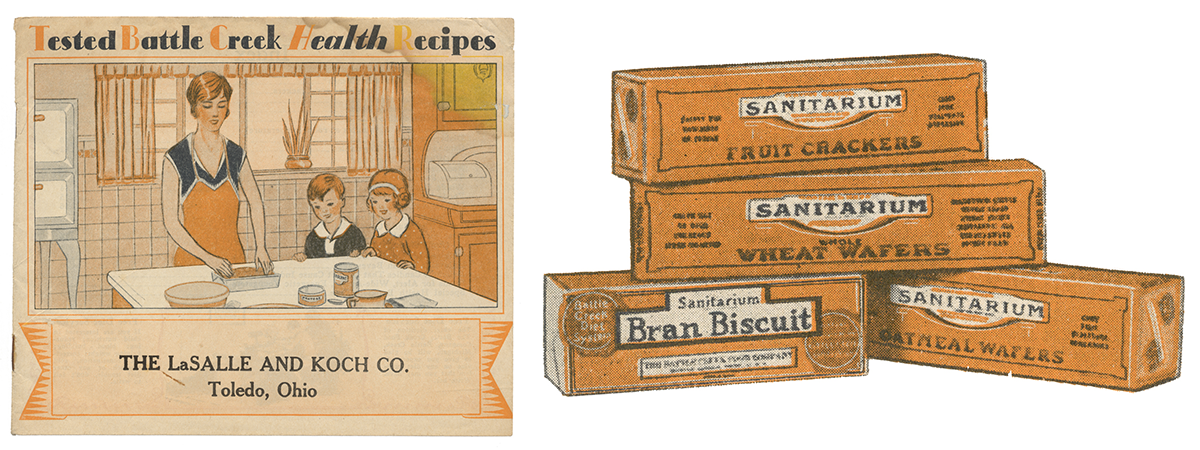

Tested Battle Creek Health Recipes, 1928. This recipe booklet is a great example of scientific motherhood in advertising. The booklet was sold along with crackers and cookies but used words like "health," "sanitarium," and "tested" to imply that the food was healthy for families like the one shown on the cover. / THF17004 and THF17005

With the fluoroscope, shoe store owners played into the medicalization of mothering. Salespeople often recommended annual or even quarterly foot X-rays for children in the way doctors might recommend yearly physicals. Repeat X-rays created repeat customers.

Additionally, kids loved fluoroscopes! Stores would advertise their shoe-fitting fluoroscopes alongside other child-friendly customer perks like balloons, contests, and candy.

Keds window display at the Campbell Boot Shop, Charlevoix, Michigan, circa 1930. This shoe store used window display contests to attract young customers with the possibility of brand new shoes. / THF723228

Until the late 1940s, fluoroscopes were used everywhere from first aid stations on job sites to quality control inspections on orange tree farms. However, the lack of regulation for radioactive machines endangered people. Several high-profile incidents eroded the public's trust in fluoroscopy. For example, between 1941 and 1943, 57 California Shipbuilding Corp. workers received mutilating radiation injuries after using the company's first aid fluoroscope. This lack of regulation also affected shoe fitting X-rays. A 1948 study of Detroit-area shoe stores showed that over 20% of stores' fluoroscopes produced 16 to 75 röntgens — the measure of radioactive discharge — per minute. At the time the maximum radiation exposure recommendation was .3 röntgen per week.

X-ray tube, circa 1915. Vacuum tubes like this are used to produce X-rays in fluoroscopes and other forms of radiography. / THF174376

In 1950, Carl Braestrup, senior physicist for New York City hospitals, was one of the first health officials to warn the public that shoe-fitting fluoroscopes could cause radiation burns and leukemia, especially in children. That same year, city health officers in Los Angeles reported that shoe-fitting fluoroscopy caused abnormal bone growth in children. But shoe stores were initially reluctant to get rid of their machines; Los Angeles shoe store owners claimed that parents' demand for X-rays drove them to keep them. It took until 1957 for Pennsylvania to become the first state to ban shoe-fitting fluoroscopes.

In many ways, the shoe X-ray represents a time when science and commerce seemed to go hand-in-hand but went toe-to-toe instead. Innovations, like the X-ray, were used to turn profits but also harmed the public.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope being photographed for digitization. / Photo by Staff of the Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford's shoe-fitting fluoroscope was conserved, rehoused, and digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

Kayla Chenault is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The WASP: “An Airplane Knows No Sex”

During World War II, a groundbreaking group of American women defied expectations and gender bias to apply their skill in the air, flying over 60 million miles and 12,650 ferrying missions for their country during the war. Nearly 1,100 women volunteered as pilots with the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). As WASP Bernice “Bee” Haydu said in a 2013 oral history interview for The National WWII Museum, “We showed the world that an airplane knows no sex.” Yet while they flew military aircraft for military purposes and risked their lives in doing so, they remained classified as civilian aviators and as such they received no military status, benefits, or recognition until decades later.

Even prior to the United States' entry into war, two pioneering pilots Jacqueline Cochran and Nancy Harkness Love were pushing for opportunities for American women in military aviation. They lobbied for inclusion and were bolstered by successful efforts abroad, where women were flying in support of the European Allies. Cochran and Love submitted independent proposals to the Army Air Forces for the noncombat employment of women. As a result, the two women were granted leadership of two programs — the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron led by Love and the Women’s Flying Training Detachment directed by Cochran. The momentum to use women pilots had some powerful advocates. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote about the subject in her September 1, 1942, "My Day" column: “We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.” In August 1943, a year after the inception of the two, they were merged into the Women Airforce Service Pilots under Cochran with Love in an executive role.

The WASP program took off. Trainees were based at Avenger Field near the small town of Sweetwater, Texas. A love of flying drew fierce competition for limited spots. Training on military aircraft was rigorous and difficult even for the experienced pilots accepted into the program. Unlike male fliers, who learned to fly as part of their training, the WASP trainees entered their program knowing how to fly. They were required to have completed 200 to 500 flight hours before being admitted to the program. Still, the washout rate hovered at just under 50 percent. Out of 25,000 applications received, 1,830 women were accepted and of those 1,074 completed their training.

Ruth Westheimer (2nd from left) and fellow trainees at Avenger Field. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.155

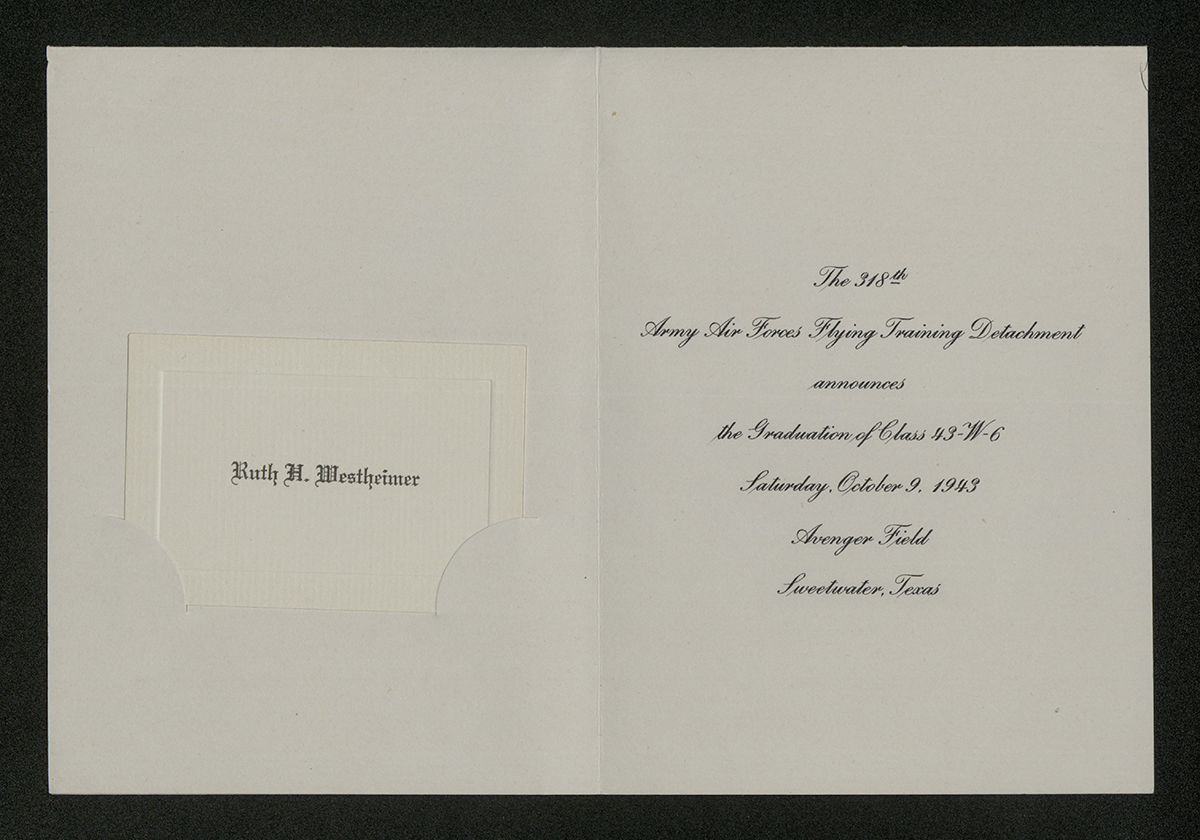

The 30-week training program at Sweetwater included 210 hours of flying time on a wide variety of military aircraft. The training culminated in a graduation where the pilots received their wings, often pinned on by Cochran herself. Whether the civilian graduates would receive wings like their military pilot counterparts was initially questioned by some. And Cochran personally funded the purchase of the insignia for the first seven graduating classes (43-1 through 43-7).

The WASP went on to their assignments, ferrying planes from factories to airbases, “test-hopping” planes that other pilots had flagged as unreliable, and even towing targets used to train anti-aircraft gunners.

Class 43-6 included 22-year-old Ruth Westheimer. Raised by German Jewish immigrant parents in Jackson, Michigan, Westheimer was fascinated by flying from a young age, watching planes at the airstrip near her home. After graduating from Jackson High School in 1939, she plotted her path to the skies and attended the Civilian Pilot Training Program while studying at Jackson Junior College. She took a job as a secretary at Montgomery Ward & Co. in Chicago until she jumped at the opportunity to fly. Accepted for WASP training in April 1943, Westheimer initially failed the required day-long physical exam due to insufficient lung capacity. Determined to fly, she recognized what was holding her back and brazenly demanded to be tested again after removing her brassiere. She passed and became part of Class 43-6. In Sweetwater, Westheimer flew a variety of planes, but her favorite was the AT-6 “Texan” training aircraft. Westheimer loved ferrying duty.

Ruth stands in the foreground with her trainee roommates at Avenger Field. Ruth’s caption reads, “This is half of our bay. The gal with the magazine and pigtails is Mac. Bernie is the other one. Both are kids.” / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.073

For a time, Westheimer was based not far from home, with the 3rd Ferrying Group at Romulus Army Air Field in Michigan. At the same time, Chinese American Hazel Ying Lee was also flying out of Romulus. Lee is a tragic example of the extreme risks inherent in the WASP’s work. Lee was later transferred to Texas for Pursuit School training. She died on November 25, 1944, two days after a collision while transporting a P-63 Kingcobra fighter aircraft. She was the last of 38 WASP who died in service.

Clipping from Ruth’s scrapbook showing Hazel Lee and her husband. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.237

February 1944 travel orders for Westheimer and Hazel Lee from Romulus to Montreal. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.244

During one of Westheimer's assignments, flying with a group from Montreal to New Jersey, the WASP ran into weather trouble. Navigating visually, she eventually found an airfield and was assisted in landing by military personnel. Westheimer later said, “You should’ve seen the surprise on their faces when they saw a 120-lb girl in uniform climb out of the cockpit of that large military plane.”

Ruth Westheimer steps out of a Fairchild PT-19A primary trainer aircraft at Avenger Field on May 6, 1943. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.017

WASP often carried out their missions in a hostile atmosphere. Despite the shared purpose of American victory, not everyone wanted the women to succeed. There was even some resentment from male pilots who wanted the women’s stateside jobs rather than overseas combat duty.

In March 1944, Cochran and Army Air Forces Commander General “Hap” Arnold presented a strong case for militarization of the WASP before Congress, but the push was unsuccessful. With the war in Europe won and the war in the Pacific winding down, the WASP militarization bill was defeated in the House of Representatives on June 21, 1944. With no active path to service, the WASP were dismissed and their program disbanded, finalized on December 20, 1944. The devastated women even had to pay for their own fares home. Some were able to get contract work with Air Transport Command or flying in other capacities, but many returned to prewar occupations or began new lives.

Ruth’s graduation announcement from Class 43-W-6. / Gift in Memory of Ruth Westheimer, 2020.220.207

Ruth Westheimer moved to Boyne City, Michigan, with her husband, 10th Mountain Division Army veteran Marshall Neymark. They raised four children, and she worked at city hall as treasurer. Later in life, Ruth made her way back to flying. Her second marriage to Boyne city manager and pilot Forbes Tompkins returned her to the cockpit. She renewed her pilot's license and began to fly again in their Cessna. After Forbes retired, Ruth stepped into the position of city manager, the first time the position was ever held by a woman.

The WASP were finally recognized for their service in 1977, when they were retroactively granted veteran status. In 2009, a bill passed to award the Congressional Gold Medal to the WASP. At the U.S. Capitol ceremony in March 2010, Ruth was one of the 200 (out of 300 surviving) WASP present to receive her award. She considered herself a “Lucky Lady,” in the right place at the right time. Ruth passed away in 2016 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery — a right that would not have been afforded during the war.

This guest blog was written by Kimberly Guise, Senior Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs at The National WWII Museum, and Curator of Our War Too: Women in Service, currently on display at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation now through September 7.