“Was Henry Ford’s father unhappy that Henry didn’t become a farmer? Did they get along?”

A few years back, my friend Regina stood in the Ford Home and asked that question to the uniformed presenter. We were on a homeschooling field trip with our children.

As many times as I’d been to Greenfield Village, I’d never considered that kind of relationship question. I had a tendency to be fascinated with the stuff – the artifacts, the décor, the period clothing, etc. I was a little surprised with the question, but even more surprised by the detail of presenter’s reply. It was a weekday, and the home wasn’t very busy, so this gentleman graciously took the time to share with us some really interesting insights and stories. That question charged my curiosity to look beyond what I was seeing, and the presenter’s deep knowledge and ability to weave a story transformed how I experienced The Henry Ford.

So, who are these presenters?

To begin with, they aren’t only the people wearing period attire. In addition to those clad in the clothes of the past, uniformed presenters drive Model Ts, carriages and other historic transportation; they operate the carousel and work throughout the village, museum and Ford Rouge Factory Tour in a multitude of capacities. They are the working storytellers who help make the artifacts and objects at The Henry Ford come alive – a key element to turning a visit into an inspirational experience.

“Presenters are an all part-time staff of highly committed, highly educated people,” Jim Van Bochove, The Henry Ford’s director of workforce development told me. They may be college students, teachers, retired professionals or someone who comes to the position with a different background or interest that fits the role. “It’s a unique position, and some people are willing to travel quite a distance to dedicate their time to being a presenter here.” He also said the presenter staff is extremely loyal, and there’s not a lot of turnover. (I’d sure say so. There's a presenter who has been with The Henry Ford for 55 years.)

New presenters and all staff for that matter – service, administrative, volunteer, intern, and executive – start their career at The Henry Ford with a daylong program called Traditions, Vision and Values. It’s a busy season for the training as Greenfield Village’s April 15 opening day approaches.

“It’s up to the all of our colleagues here to deliver The Henry Ford experience to our guests,” Jim said. The TVV training, as they call it, is where they learn about the history, culture and vision of the institution. I caught some of it, and it was a pretty lively time – appropriate for working at such a dynamic place.

This group is enjoying an early March TVV program. Some of the participants are assigned as presenters in one of the seven districts in Greenfield Village such as Working Farms or Edison at Work.

Above, Tim Johnson and Meg Anderson from The Henry Ford’s workforce development department engage new staff. You can see that Henry Ford himself remains an important part of the training.

After this training, presenters go through a day of hospitality training. Then they attend two days of basic presenter training to learn storytelling techniques, engage in role playing, make presentations on newly learned material, and benefit from the constructive comments from other new and experienced presenters.

After the general training, presenters move on to hands-on instruction by their managers, supervisors and site leaders depending on where they will be assigned. Kathie Flack, training and event logistics manager, explained to me that by assigning presenters to specific districts, they have more of an opportunity to really become experts in their area.

Since most new presenters this time of year are gearing up for work assignments in Greenfield Village, they might be instructed on how to start and maintain a fire or cook using a wood burning stove. They may attend Model T driving school or learn to milk a cow, harness a horse, operate a plow, or make candles or pumpkin ale. During this time, they’ll also get some of the details regarding the logistics of working at their assigned venue.

At the William Ford barn, I looked on as an experienced presenter and carriage driver instructed a new presenter in harnessing a horse. It looked pretty complicated to me, but Ryan Spencer, manager of Firestone Farm, assured me that after some practice, it only takes one person five minutes to collar, harness and hitch a team of two horses to a carriage.

Before she can drive visitors, she’ll have to pass certification which includes 50 hours of guided training and passing a driving test with 100-percent.

“It’s pretty involved,” Ryan said. “The driver has to be prepared, and the team has to be confident with the driver. She also has to be able to get out of uncomfortable situations and to anticipate certain others.”

In addition to all the horse-related training necessary, new drivers have to pass a tour test and a written test – also with a perfect score.

The new presenter (on the right) spent the day at Firestone Farm learning about chores in the house and barn. In the photo above, he’s examining the grooves from the pit saw used to cut the white oak into lumber when the Firestone’s built the barn in about 1830. He will most likely be horse trained next winter season. “There’s a lot of other work to learn at the farm first,” Ryan said.

In addition to the specific presenter training, there’s getting dressed for the job. The clothing studio outfits all workers who encounter guests at The Henry Ford – whether it is in a uniform or period-specific gear.

This presenter stands for a final fitting of a new custom ensemble as a seamstress inspects. Tracy Donohue, the manager of the clothing studio said they make most all elements of period attire, with the exception of a few foundational garments such as corsets. Uniforms are also purchased in pieces, but all are tailored for each wearer.

The studio works with curators and available historic resources to fit presenters with the most accurate period clothing. There are often multiple fittings. Tracy said that depending on the detail and the pattern challenges, there might be as many as 80 hours of work put in making one dress.

I have to say, the studio storage warehouse is a pretty spectacular place – with aisles and aisles of period clothing, historically accurate fabrics and accessories, and the fantastic costumes for special events like the Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village and Holiday Nights.

Tracy told me the studio has a very comprehensive cataloging system since it inventories close to 50,000 items.

Once presenters are trained, outfitted and equipped with the key elements of the stories they’ll tell, and after they gain a little experience, they can really dig in to learn more by visiting the reading room at the Benson Ford Research Center.

The green binders above are filled with detailed information and interesting facts specific to the buildings and artifacts; community and domestic life, and customs and historic practices of the time periods represented in Greenfield Village.

Presenters (and visitors for that matter) may also access some primary source materials associated with each building, including its move to Greenfield Village. The photo on the right is of the Wright Brothers’ bicycle shop in its original location, before Henry Ford had it moved to the village from 1127 West Third St. in Dayton, Ohio, in 1937.

It’s no doubt the people who become presenters at The Henry Ford are there because they want to be there. They’re eager to delve into more of the details and history and share it because they understand Henry Ford’s original vision and want to inspire visitors to learn from the traditions of the past to make a better future.

I love this photo I took a couple years ago. This presenter was pleased (and relieved) with her successful first experience making grape preserves.

The Henry Ford staff, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Culture Lab Detroit is a catalyst for conversations and collaborations between Detroit's artists, designers, innovators, technologists and the larger design world. In other words Culture Lab Detroit was designed for all of us.

Two years ago I attended an exhibition in Paris that examined the importance of the relationship between nature, culture, business, and the social fabric within a city. The exhibit began with a look at how a 16th century Spanish city was designed to incorporate and encourage creativity and growth and it ended by asking the same questions of a modern city: what are the ingredients of a thriving city and how to fill its spaces.

The exhibit was called The Fertile City. And that modern day city it examined was Detroit.

It was astonishing to travel to a European museum to see an exhibit that focused so heavily on the struggles of Detroit. But I soon realized it was fitting that anyone looking at the effects of a damaged urban landscape in the 21st century would study Detroit. We have so many open uncertain spaces, and yet so many assets, so much ripe potential.

Some of those open spaces are geographic. Some are economic. Some are social. But the thing is that's all changing. Bit by bit, this city that has captured international attention is starting to fill its voids, recognizing them as assets in a way that is uniquely Detroit.

Today's Detroit innovators are pioneers. Through their efforts they're carefully blazing the trail for a more culturally vibrant landscape. They are the new vanguard of Detroit. Each one is a piece of the puzzle - gardening here, sewing there, creating art over there. And hundreds more pieces have found a home at incubator sites like the Detroit Creative Corridor Center, the Russell Industrial Center, Ponyride or the Green Garage. These places give structure and a home to artists, innovators, entrepreneurs and technologists.

This is a world-class town filled with world-class people. Culture Lab hopes to connect and inspire the best problem solvers in Detroit with world-class artists, innovators and thinkers internationally as a way to increase awareness and the imprint of Detroit's creative community around the globe.

I hope you can join me in learning more about these new innovators and celebrating this surge of creativity and ideas on Thursday, April 18, at the College for Creative Studies for an evening of conversation and collaboration with my good friend David Stark. David is a world-renowned event designer, author, and installation artist. Joining David that evening will be Mark Binelli, Michael Rush, Toni Griffin, and Daniel Caudill. You can learn more about the event, hosted by Culture Lab Detroit, here.

Jane Schulak is the founder of Culture Lab Detroit. Jane believes that by sharing these experiences this will increase the awareness and the imprint of Detroit's creative community internationally.

Guest Judging at Detroit Autorama 2013

Over the weekend of March 9-10, I had the pleasure of serving as a guest judge at the 2013 Detroit Autorama. The show, which features some of the best hot rods and custom cars in the country, is to car guys what the World Series is to baseball fans. My task was to select the winner of the CASI Cup, a sort of “sponsor’s award” given by Championship Auto Shows, Inc., Autorama’s producer.

I’d like to say that I entered Cobo Center and got straight to work, diligently focused on my duties. But it would be a lie! I quickly got distracted by the amazing vehicles. There was “Root Beer Float,” the ’53 Cadillac named for its creamy brown paint job. There was the ’58 Edsel lead sled with its chrome logo letters subtly rearranged into “ESLED.” There was the famous Monkeemobile built by Dean Jeffries. And, from my own era, there was a tribute car modeled on Knight Rider’s KITT. (You’ve got to admire someone who watched all 90 episodes – finger ever on the pause button – so he could get the instrument panel details just right.)

Every vehicle was impressive in its own way, whether it was a 100-point show car or a rough and rusted rat rod. In the end, though, my pick for the CASI Cup spoke to my curator’s soul. Dale Hunt’s 1932 Ford Roadster was, to my mind, the ultimate tribute car. It didn’t honor one specific vehicle – it honored the rodder’s hobby itself.

Hunt built his car to resemble the original hot rods, the fenderless highboy coupes that chased speed records on the dry lakes of southern California. The car’s creative blend of parts and accessories – the ’48 Ford wheel covers, the stroked and bored Pontiac engine, the lift-off Carson top – all spoke to the “anything goes” attitude that is at the heart of hot rodding and customizing to this day.

It was a privilege to be a part of the show. Like most of the fans walking the floor with me, I’m already looking forward to Autorama 2014!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, Michigan, Detroit, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson, Autorama

Autism Alliance of Michigan Partnership

Last week we were pleased to announce our partnership with the Autism Alliance of Michigan, a state-based agency dedicated to improving the lives of families with autism. Our goal every day at The Henry Ford is to make sure our guests have an outstanding experience while here on our campus, so calling out special information for guests with autism is something we’re very happy to do.

Last week we were pleased to announce our partnership with the Autism Alliance of Michigan, a state-based agency dedicated to improving the lives of families with autism. Our goal every day at The Henry Ford is to make sure our guests have an outstanding experience while here on our campus, so calling out special information for guests with autism is something we’re very happy to do.

Providing specialized information for guests’ needs isn’t new to us. We’re always looking to communities to tell us what would make their visit here even better. When we created large-scale maps to hand out on site, we worked with special groups to make sure the printed materials were beneficial to those with vision impairments.

As part of our partnership with AAOM, resource guidelines are being created for families to review prior to their visit. Some of those guidelines will help guests with learning about our:

Key members of our front-line staff will also be receiving training in basic aspects of autism. We’ll continue to meet with the AAOM to learn more about autism and improve our offerings for those guests.

Whether you’re enjoying a walk around Greenfield Village or a visit inside Henry Ford Museum, The Henry Ford is a safe place for all families. Everyday our staff members continue to grow and learn how we can best serve the needs of all of our guests.

We’re looking forward to growing our partnership with AAOM. Making all of our guests happy is what we do - it’s our job, and we’re proud to do it.

Make sure to keep an eye on our “Visit” section of our website for links to AAOM in the coming weeks.

Michigan, accessibility, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

This year brings a couple of notable – and not particularly pleasant – anniversaries for Studebaker fans. Fifty years ago, in December 1963, the company closed its operations in South Bend, Ind. – where brothers J.M., Clement, Henry, Peter and Jacob founded the venerable firm more than 100 years before. While Studebaker built cars in Canada for a few more years, many say that the company really ended when it left its longtime home.

We also mark the anniversary of an earlier corporate struggle. Eighty years ago this month, Studebaker filed for bankruptcy. While many car companies went under during the Great Depression – and few recovered – Studebaker’s bankruptcy is a particularly sad story of poor management and human tragedy.

Albert Erskine joined Studebaker as treasurer in 1911 and assumed its presidency in 1915. He cut prices and boosted sales, leading to generally good years for Studebaker marked by stylish vehicles and progressive labor relations.

When the Depression hit and sales crashed, Erskine turned to South Bend’s closest thing to a superhero: Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne. The football legend died in a 1931 plane crash, and Erskine named Studebaker’s new line of small, affordable automobiles “Rockne” is his honor. The Rockne was well-equipped for an inexpensive car and early sales were promising. But rather than concentrate all production in South Bend, Erskine built most of the Rocknes in Detroit. The two factories strained Studebaker’s shaky finances.

More troubling was Erskine’s insistence on paying high dividends to stockholders even in the Depression’s worst years. While other car companies hoarded cash to ride out the storm, Studebaker burned through it. Erskine simply refused to believe that the Great Depression was anything more than an economic hiccup.

Inevitably, Studebaker ran out of cash and, on March 18, 1933, entered receivership. Erskine was pushed out of the presidency in favor of more cost-conscious managers. His successors engineered a brilliant turnaround and led Studebaker out of receivership in two years. Sadly, Erskine’s ending was quite different. With his job gone, his Studebaker stock worthless, his personal debts mounting and his health failing, Erskine took his own life on July 1, 1933. While he may not have been wholly responsible – clearly the Board of Directors failed in its oversight – Albert Erskine paid the ultimate price for Studebaker’s ordeal.

Take a look at more of our Studebaker artifacts in our online Collections.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

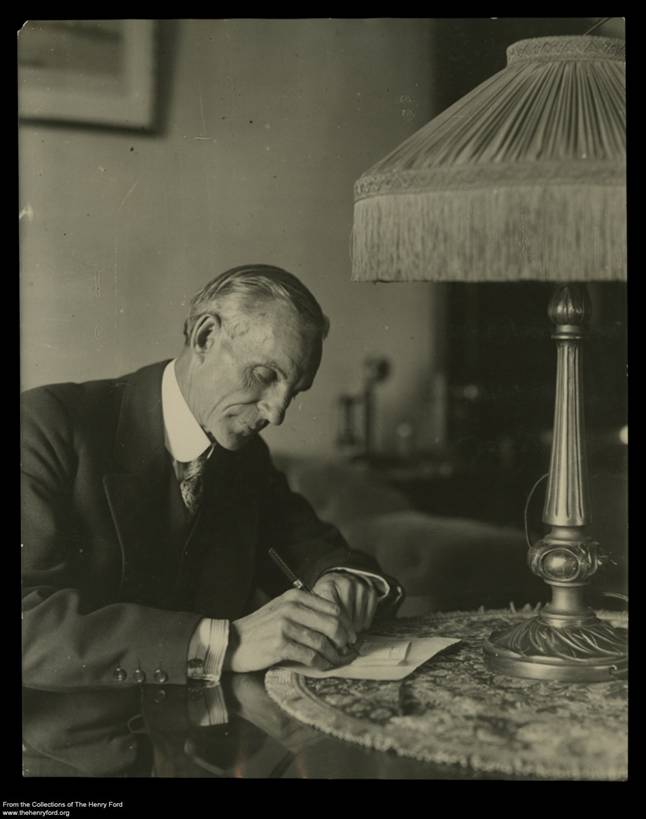

Henry Ford’s Quotations

Henry Ford's achievements, which revolutionized both industry and society, made him a folk hero. His unique and colorful personality helped cement his legend. A study in contrasts, he possessed an original mind and was a strong intuitive thinker, but had a distrust of formal learning and little personal education. Although he shrank from public speaking, he came to relish publicity.

Because of his immense popularity and notoriety during his lifetime and since, numerous sayings have been ascribed to Henry Ford. Many of these sound plausible but are incorrect, and some can’t be traced to him at all. Too often, a quote is attributed to Ford simply because its touches upon success in business or innovation: He has become a patron saint of the entrepreneur, a Paul Bunyan of the business world. One of the more popular of these quotations is, "If I had asked my customers what they wanted they would have said a faster horse," which has never been satisfactorily traced to Henry Ford. In fact, the quote only begins to appear in the early 21st century, "quoted" by modern-day business gurus using it as an object lesson, whereas germs of its main idea can be directly sourced to other speakers through the late mid to later 20th century. (See more at the Quote Investigator.)

Compounding the problem of misattribution is what could best be described as the unclear origin of legitimate Henry Ford quotes. As mentioned, Ford had a strong aversion to public speaking. Nervous in front of crowds, he opened up and even sparkled in smaller settings. (Known for avoiding the press, he would grant the rare interview to a changing circle of select reporters.) Moreover, the rough-hewn Henry Ford was no writer, and hence relied on helpers to prepare published materials. Among his ghostwriters were two longtime, trusted staff members: his executive secretary, Ernest G. Liebold; and his publicist, William J. Cameron. Joining them was the journalist Samuel Crowther, who was the prolific ghostwriter of three Henry Ford memoirs (My Life and Work, Today and Tomorrow, and Moving Forward). Crowther spent considerable time with Ford and proved adept at presenting the magnate's ideas for publication.

As a result of the foregoing complexity, many of the quotations attributed to Henry Ford in common circulation today prove at best problematic to verify or challenge.

Work on collecting and authenticating Henry Ford quotations was begun by Ford Motor Company staff in the Ford Motor Company Engineering Library—possibly as early as the mid-1920s. (The library, housed in Ford’s Engineering Department, maintained files on a wide variety of subjects of interest to or about Henry Ford.) A longtime Ford Engineering librarian, Rachel MacDonald, assembled the quotations into a collection, the Henry and Edsel Ford Quotations collection. This collection was later transferred to the Ford Motor Company Archives, in 1955. While we do not know the exact date MacDonald started her research, records indicate that she was at Ford Motor Company at least as early as 1940 (but no earlier than 1936) and up through the transfer of the collection to Ford Motor Company Archives. What we don't know is whether the collection was started before or after Henry Ford's death (or, consequently, how much input Ford himself had in verifying the quotations). The Henry Ford received the collection in 1964 as part of a much larger donation of Ford Motor Company records. Staff, interns, and volunteers of the Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford have continued work to authenticate Henry Ford quotes, resulting in this publicly accessible list.

The collection includes quotations that have been traced to a primary source or a reliable secondary source. Examples of reliable secondary sources would be a published interview with Henry Ford or other direct quotations of Henry Ford in newspapers contemporary to him, including but not limited to publications such as the Ford Times and Ford News. A book whose ghostwriting or collaboration was authorized by Henry Ford also falls under this category. Among the primary sources drawn on are Henry Ford's own "jot books," or personal notebooks, found in two different archival collections. These notebooks, few in number, provide a good example of Henry Ford's writing style and interests. If you are searching for a quote and do not see it on our list, it means that staff was not able to trace it to a reliable source.

So many of the unverified quotations are now out in the world and on the web that it is no small challenge to track and verify them. Quotations like the “faster horse” quip, as well as other maxims like the one illustrated below appear on a variety of products, including coasters, mugs, and T-shirts. These quotations and their use speak volumes to a natural human tendency to use legendary figures and a historical lens to illustrate the ideas and trends relevant for our time.

If you have questions or comments about the Henry Ford quotations page, please contact the Benson Ford Research Center at research [dot] center [at] thehenryford.org.

Rebecca Bizonet is former Archivist at The Henry Ford.

The Fashions of Elizabeth Parke Firestone

Elizabeth Parke Firestone (1897-1990) was destined to develop a refined sense of fashion. Born the daughter of a wealthy Decatur, Ill., businessman, she was given the opportunity to study in Europe in her mid-teens. Through this adventure she developed a deep appreciation for French culture, particularly French decorative arts. She also nurtured a lifelong love of dancing, which influenced not only her fashion sense but her choice of spouse.

Elizabeth met Harvey S. Firestone, Jr., at a dance. Their 1921 wedding was the union of two well-established business families, and their celebration was the most lavish Decatur had ever seen. It began a 52-year marriage, during which the couple raised four children at "Twin Oaks," their Akron, Ohio, home. They also maintained homes in New York City and Newport, R.I.

Elizabeth's background prepared her well for her role of representing her husband and family in the most influential business and social circles of the time. She joined her husband on business trips, traveling the United States, Europe and Asia throughout their marriage. She looked to both the New York and Paris fashion scenes to find couturiers who met her style standards, then worked through both correspondence and visits to modify their designs to fit her best features.

Elizabeth was meticulous about her looks, leaving no detail unattended. Her fair skin became radiant when she wore pinks and blues, and most of her clothing can be found in variations of these shades. Multiple matching gloves, shoes, purses and hats were commissioned for each outfit, so that replacements would be readily available in case of damage.

Trim, blonde and blue-eyed, Elizabeth looked stunning in designer gowns and was frequently photographed for fashion and society magazines. Well into her 50s her fashions were the talk of society, and her style-both classy and classic-was frequently noted in the press. In the 1950s she was named one of the "Best Dressed Women in the World" by the Couture Group of the New York Dress Institute along with the Duchess of Windsor and Hollywood actresses including Olivia de Havilland.

Prior to her death, Elizabeth and her family realized that the clothing she owned offered a rich and sweeping view of fashion history to future generations, and a large segment of her wardrobe was donated to The Henry Ford. Today that collection includes more than 1,000 dresses, shoes, gloves and other accessories, from early home-sewn creations including her wedding dress to custom-made American and European designer fashions. Each dress is truly a work of art, crafted by inventive couturiers for a patron who not only collaborated on the result, but well understood the contribution each made to the life of her family and the society of the day.

Gauging the Condition of the Dymaxion House

At The Henry Ford, Conservation’s job is to maintain artifacts as close to original condition as possible while also ensuring access. The Dymaxion House is a fairly fragile aluminum structure, and a very popular exhibit, which makes preservation a little bit of a challenge.

Last year we did some rather major surgery on the Dymaxion House. We opened up the floor and patched all 96 aluminum floor beams to reinforce them where many had developed cracks.

As I explained in past blog posts, linked below, the damages were found primarily on the heavy-traffic side of the house, where our guests walk through. The repair job in 2012 took two months of hard work.

After all that effort, how do we ensure that this kind of damage won’t progress?

This year we are setting up some cool monitoring devices that will help us understand the house better.

All metal structures move. We want to figure out how our beams are moving, and whether the structure can continue to withstand the forces we apply to it.

Under the guidance of our own engineer, Richard Jeryan, who is retired from Ford Motor Company, and with the generous assistance of Ford Senior Chassis Test Engineer Dave Friske and two skilled technicians, Instrumentation Expert Walter Milewsky and Fastener Lab Technician Richard Talbott, we are installing stress and strain gauges along with crack detection and propagation gauges.

These gauges are the kind of very precise instrument used by engineers to find out how structures perform. They are used to test automobile parts (even ones as small as bolts) during design, and are also used on buildings and bridges.

Strain gauges are used to measure the amount of deformation (strain) when a building is loaded. Put another way, stress is a measurement of the load on a material, strain is a measure of the change in the shape of the object that is undergoing stress. We will be recording a baseline stress on the beams with the house empty of people and collecting our strain data on a busy week in the museum (like the Fouth of July!).

The crack detection gauges will alert us to a crack that is starting, and the propagation gauges will tell us how quickly a new crack is progressing.

These tiny devices are glued onto the beams and wires soldered onto them so that electrical resistance can be monitored with special equipment. Engineers gather the electrical resistance data and use formulas to calculate the degree and character of stress. We are applying the gauges in a number of locations to gather the best overall picture of how the beams move.

We also measured the deflection of the structural wire “cage” using a fancy laser-level and we recorded the data. This will enable us to compare yearly readings during our annual inspection to determine how the cage may be moving.

This is science and technology – working for preservation.

Clara Deck is a Senior Conservator at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Dymaxion House

- Curating & Preserving: The Dymaxion House

- Learning about "The House of the Future"

- Dymaxion House at its 1948-1991 Site, near Andover, Kansas

technology, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, conservation, collections care, Henry Ford Museum, by Clara Deck, Dymaxion House, Buckminster Fuller

The Story of John Brown, the Martyr

I have always found John Brown to be an intriguing historical figure. Recently I studied a print in The Henry Ford's collection made by the popular printmakers Currier & Ives in 1870 featuring John Brown. This print has helped me to understand the connection between John Brown's actions and the emotions from over 150 years ago surrounding the Civil War in the United States.

In the years prior to the Civil War, Southern slave-owners stubbornly defended the necessity of slavery while vocal abolitionists continued to oppose it. For many people—especially in the North—slavery was still an abstract concept. But by appealing to emotions, different people during this time made thousands of Americans suddenly have a point of view.

One was John Brown, a long-time anti-slavery activist who took matters into his own hands. On October 16, 1859, he tried to steal government weapons in Harper's Ferry, Va., convinced that Southern slaves would follow him in a revolt. But he was caught and hanged for treason. Northerners honored him because he was willing to die for a cause. But it gave Southerners one more reason to prepare for war.

Currier & Ives of New York City published this hand-colored lithograph in 1870 based on the painting by Louis Ransom made soon after John Brown's death in 1859. This original painting was displayed in P. T. Barnum's American Museum in New York City during the spring and summer of 1863, the same year that Currier & Ives published their first lithograph on this subject. The second version of the lithograph, shown here, was made later but sentiment about Civil War heroes sold well and this scene continued to appeal to American popular taste of the 1870s.

The text printed below this lithograph includes "Meeting a Slave Mother and her Child on the steps of Charlestown Jail on his way to Execution. Regarding them with a look of compassion Captain Brown stooped and kissed the Child then met his fate." This did not actually happen the day John Brown was executed on December 2, 1859. Brown was surrounded by troops and the public had no direct access to him. This story was first published in the New-York Tribune on December 5, 1859. Although it was later revealed as untrue, it became a popular legend about John Brown.

The poet John Greenleaf Whittier included this story in his poem, "Brown of Ossawatomie" printed on December 22, 1859; as did James Redpath in his biography, The Public Life of Capt. John Brown, published in January 1860. Redpath wrote about John Brown's walk from jail to the gallows in his book on page 397:

"As he stepped out of the door, a black woman, with a little child in her arms, stood near his way. The twain were of the despised race for whose emancipation and elevation to the dignity of children of God he was about to lay down his life. His thoughts at that moment none can know except as his acts interpret them. He stopped for a moment in his course, stooped over, and with the tenderness of one whose love is as broad as the brotherhood of man, kissed it affectionately."

John Brown was a hero to many abolitionists during the Civil War and this legend surrounding him helps to explain what he represented to them. The Currier & Ives print version made in 1870 of "John Brown, The Martyr," attests to the continuing importance of this legend in the era following the Civil War.

Cynthia Read Miller, Curator of Photographs and Prints, is continually fascinated with the museum’s over one million historical graphics.

Civil War, by Cynthia Read Miller, archives, art, African American history

African American Workers at Ford Motor Company

No single reason can sufficiently explain why in a brief period between 1910 and 1920, nearly half a million Southern Blacks moved from farms, villages, towns and cities to the North, starting what would ultimately be a 50-year migration of millions. What would be known as the Great Migration was the result of a combination of fundamental social, political and economic structural problems in the South and an exploding Northern economy. Southern Blacks streamed in the thousands and hundreds of thousands throughout the industrial cities of the North to fill the work rolls of factories desperate for cheap labor. Better wages, however, were not the only pull that lured migrants north. Crushing social and political oppression and economic peonage in the South provided major impetus to Blacks throughout the South seeking a better life. Detroit, with its automotive and war industries, was one of the main destinations for thousands of Southern Black migrants.

In 1910 Detroit’s population was 465,766, with a small but steadily growing Black population of 5,741. By 1920 post-war economic growth and a large migration of Southerners to the industrialized North more than doubled the city’s population to 993,678, an overall increase of 113 percent from 1910. Most startling, at least for white Detroiters, was the growth of the city’s Black population to 40,838, with most of that growth occurring between 1915 and 1920.

Photo: P.833.34535 Fordson Tractor Assembly Line at the Ford Rouge Plant, 1923

Before the war, Detroit’s small Black community was barely represented in the city’s industrial workforce. World War I production created the demand for larger numbers of workers and served as an entry point for Black workers into the industrial economy. Growing numbers of Southern migrants made their way to Detroit and specifically to Ford Motor Company to meet increased production for military and consumer demands.

By the end of World War I over 8,000 black workers were employed in the city’s auto industry, with 1,675 working at Ford. Many of Ford’s Black employees worked as janitors and cleaners or in the dirty and dangerous blast furnaces and foundries at the growing River Rouge Plant’s massive blast furnaces and foundries. But some were employed as skilled machinists or factory foremen, or in white-collar positions. Ford paid equal wages for equal work, with Blacks and whites earning the same pay in the same posts. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Ford Motor Company was the largest employer of Black workers in the city, due in part to Henry Ford’s personal relationships with leading Black ministers. Church leaders in the Black community helped secure employment for hundreds and possibly thousands, but more importantly, they also helped to mediate conflicts between white and Black workers.

Photo: P.833.55880 African American workers at Ford Motor Company’s Rouge River Plant Cyanide Foundry, 1931

Photo: P.833.57788 Foundry Workers at Ford Rouge Plant, 1933

Photo: P.833.59567 Pouring Hot Metal into Molds at Ford Rouge Plant Foundry, Dearborn, Michigan, 1934

In addition to jobs, Ford Motor Company provided social welfare services to predominantly Black suburban communities in Inkster and Garden City during the depths of the Great Depression. Ford provided housing and fuel allowances as well as low-interest, short-term loans to its employees living in those communities. Additionally, Ford built community centers, refurbished several schools and ran company commissaries that provided inexpensive retail goods and groceries. (You can learn more about the complicated history of Ford and Inkster in The Search for Home.)

You can learn more by visiting the Benson Ford Research Center and our online catalog.

Peter Kalinski is Racing Collections Archivist at The Henry Ford. This post was last updated in 2020 with additional text by Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson.

20th century, Michigan, labor relations, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, by Peter Kalinski, African American history