Posts Tagged civil war

The Grand Army of the Republic and Memorial Day

Members of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) Visiting Mount Vernon, September 21, 1892 / THF254036

The Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) was a fraternal society founded in 1866 for Civil War veterans from the Union Army. Earlier this year, Collections Specialist Laura Myles shared some artifacts from our collections related to the G.A.R., and also explained their relationship with Memorial Day (originally called Decoration Day), as part of our History Outside the Box series on The Henry Ford’s Instagram channel. On the first Friday of every month, our collections experts share stories from our collection on Instagram—but if you missed this particular episode, you can watch it below.

Continue Reading

20th century, 19th century, veterans, holidays, History Outside the Box, Grand Army of the Republic, Civil War, by Laura Myles, by Ellice Engdahl

"Veterans of the Late Unpleasantness": A Brief History of the Grand Army of the Republic

Artwork Used in a Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) Hall in Bath, Maine, circa 1866 / THF119558

Following the end of the Civil War, numerous fraternal veterans’ societies were formed. These societies enabled veterans to socialize with individuals who had similar experiences and also allowed them to work towards similar goals.

Dr. Benjamin Franklin Stephenson formed the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) for all honorably discharged Union veterans on April 6, 1866, in Decatur, Illinois, and it quickly grew to encompass ten states and the District of Columbia. The G.A.R.’s growth was astronomical, peaking in the 1890s with nearly 400,000 members spread out through almost 9,000 posts in all 50 states, as well as a few in Canada, one in Mexico, and one in Peru. These posts were organized into departments, which were typically divided by state, but could include multiple states depending on the population of Union veterans in the area.

Woman's Relief Corps (W.R.C.) Conductor Badge, 1883-1920 / THF254030

Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War Membership Badge, circa 1900 / THF254033

The tenets of the G.A.R. were “Fraternity, Charity, and Loyalty,” and are depicted in the seal of the G.A.R. The fraternity aspect was met by fraternal gatherings such as meetings, as well as annual reunions known as encampments at the departmental and national level. Charity was demonstrated through fundraising for veterans’ issues, including welfare, medical assistance, and loans until work could be found, as well as opening soldiers’ and sailors’ homes and orphanages. Loyalty was demonstrated in several ways, including erecting monuments, preserving Civil War sites and relics, donating cannons and other relics to be displayed in parks and courthouses, and donating battle flags to museums. The G.A.R. was assisted in all of their work by their auxiliary organizations, known as the Allied Orders of the G.A.R.: the Women’s Relief Corps, Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic, Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUVCW), the Auxiliary to the SUVCW, and the Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War—all of which are still active today.

THF623379

Additionally, the G.A.R. was instrumental in having the tradition of memorializing the dead and decorating their graves recognized as the federal holiday Memorial Day, formerly known as Decoration Day. From its origins in smaller, localized observances throughout the country, it gained national recognition after Commander-in-Chief General John A. Logan issued a proclamation on May 30, 1868. Programs like the one above detail the order of events of these celebrations, and some even detail how to appropriately contribute.

Members of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) Visiting Mount Vernon, September 21, 1892 / THF254036

The annual and national encampments were not just big events for the G.A.R. and the Allied Orders of the G.A.R, but also for the railroads and cities in which the encampments were held. Railroad companies, such as the Maine Central Railroad Company, advertised the encampments and offered round-trip tickets to attendees. A typical schedule of events for encampments included speeches, business meetings where delegates voted on resolutions and other organizational business, receptions for the G.A.R. and the Allied Orders, parades reminiscent of the Grand Review of the Armies following the end of the Civil War, campfire activities, concerts, outings to nature or historic points of interest, and reunions of other groups, including regimental and other veteran organizations. Attendees to the 1892 Washington, D.C., National Encampment were able to visit Mount Vernon.

THF254025

THF254026

Members would show up in their uniforms, which often included hats with G.A.R. insignia, as well as their G.A.R. membership badge, an example of which can be seen above. Membership badges denoted the wearer’s rank at the time they mustered out and would also show what rank within the G.A.R. they held; Commander-in-Chief badges would be substantially more ornate.

In addition to their membership badges, attendees would also represent their home state, posts, or departments with ribbons or badges stating where they were from. An example is the Forsyth Post badge used at the 1908 Toledo, Ohio National Encampment. These ribbon badges are all unique to the host city—for instance, Detroit’s national encampments’ badges featured an image of Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac sailing to Detroit, signifying the city’s founding in 1701; national encampments held in California typically featured a grizzly bear, like their state flag; Denver’s 1905 National Encampment featured a cowboy on a bucking bronco; and Holland, Michigan’s 1904 and 1910 Annual Encampments featured wooden shoes and windmills.

THF254023

THF254031

Badges help tell the story of the G.A.R., and make these events more relatable to modern audiences—who hasn’t bought a souvenir on vacation or at an event? Beginning in 1882, The G.A.R. produced official souvenir badges for purchase in addition to the membership badges. Some of these souvenirs were made from captured Confederate cannons authorized for destruction by acts of Congress. In the case of the G.A.R., badges were so important that in the 50th Congress, 1st Session, a bill (Report No. 784) was passed to “prevent the unlawful wearing of the badge or insignia of the Grand Army of the Republic or other soldier organizations.”

Watching the highly decorated G.A.R. members march in the parade was a sight that drew many thousands of spectators wherever the encampments were held. The members would have likely marched in their G.A.R. uniforms, which included a double-breasted, dark blue coat with G.A.R. buttons and a hat (either kepi or slouch felt) with G.A.R. insignia. Other uniform pieces, such as leather gauntlets with G.A.R. insignia, are known to exist, but they do not appear to be commonplace. As they had done in the Grand Review of the Armies, they would march with their flags. In 2013, one such flag was conserved by The Henry Ford, as documented in this blog post: “Conserving a G.A.R. Parade Flag.”

Grand Army of the Republic Parade at Campus Martius, Detroit, Michigan, 1881 / THF623825

As the G.A.R. members aged, the number capable of walking an entire parade route dwindled, but luckily for them, the rise of the automobile ensured that they could still participate. For veterans who did not take their personal automobiles to the encampments, calls were sent out to round up enough vehicles to provide each veteran with a car for the parade. In the case of the 1920 Indianapolis National Encampment, John B. Orman, Automobile Committee Chairman, sought to get enough automobiles for all of the veterans requiring them and said “The ‘boys’ of ’61 are no longer boys. Today the distance from the monument erected to their memory to Sixteenth Street is longer than the red road from Sumter to Appomattox.” Local dealerships loaned their cars for the parade, much like today’s parade sponsors sending cars or attaching their names to floats in parades.

At the 83rd and final G.A.R. National Encampment, held in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1949, six of the last sixteen G.A.R. members not only made the trip to Indianapolis but were able to “march” in the final parade—thanks to the automobile.

Joseph Clovese, one of the six to have participated in the final parade, can be seen with fellow G.A.R. members adorned with their G.A.R. badges on his Find a Grave page. Clovese was born into slavery on a plantation at St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, in 1844. He joined the Union Army during the siege of Vicksburg as a drummer boy, and then later became an infantryman in the 2nd Missouri Colored Infantry Regiment (later the 65th U.S. Colored Troops Regiment). Following the war, Clovese worked on riverboats on the Mississippi River and assisted with the construction of the first telegraph line between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Biloxi, Mississippi.

Clovese received a citation and medal at the “Blue and Gray” reunion, the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1938. At age 104, he moved to Pontiac, Michigan, with his niece, and, according to his obituary in the New York Times, he would take daily walks and was hardly ever ill. He died July 13, 1951, in the Dearborn Veterans Hospital at the age of 107. More information about his long and fascinating life, as well as additional photos of him wearing his G.A.R. badges, can be seen in his Fold3 Gallery.

The G.A.R. officially dissolved in 1956 with the death of the last member, Albert Woolson, but the spirit of the organization lives on through the Allied Orders of the G.A.R.

For additional looks at the G.A.R., check out the other G.A.R. artifacts in our Digital Collections and read a past blog post, “Fraternity, Charity, Loyalty: Remembering the Grand Army of the Republic.”

Laura Myles is Collections Specialist at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 19th century, veterans, philanthropy, holidays, Grand Army of the Republic, Civil War, by Laura Myles, African American history

Image of Martha Coston from her 1886 autobiography. (Not from the collections of The Henry Ford.)

Inventor Martha Coston overcame 19th-century gender stereotypes to help change the course of the Civil War, as well as boating safety. In 1848, tragedy struck when Martha’s husband, a successful inventor formerly employed in the Washington Navy Yard, died as a result of chemical exposure from his gas lighting experiments. His death was followed by the deaths of two of their children and a mother Martha was close to, and a relative mishandling Martha's remaining money. Martha was left a single mother with minimal support.

Sylvic Gas Light, B. Franklin Coston, Patentee, Washington City, D.C. N.B., Gas Light Generator, 1845. / THF287321

Martha needed a way to support herself and her two remaining children. Within her husband's papers, she discovered drawings for a pyrotechnic night signal that could be used by ships to communicate. After finding that the invention didn't work, she took on years of experiments in hopes of creating a functional signal flare. With no knowledge of chemistry or scientific methodology, Martha relied on others for help. Men often ignored her, didn't take her seriously, or deceived her.

Section of the First Transatlantic Cable, 1858. / THF77301

The signal set used three colors to create coded messages. As a patriotic woman, Martha wanted flares that burned red, white, and blue. While she had developed recipes for red and white, blue remained elusive. A breakthrough came in 1858, when Martha was in New York City watching fireworks during celebrations for the first transatlantic cable.

Illustration from an 1858 Harper's Weekly depicting the New York translatlantic cable firework celebration. / THF265993

Inspired by the fireworks, Martha wrote New York pyrotechnists looking for a strong blue, corresponding under a man's name for fear that she would be ignored. Instead of a blue, Martha was able to locate a recipe for a brilliant green. In 1859, Patent No. 23,536, a pyrotechnic night signal and code system, was granted, with Martha Coston as administrator—and her late husband as the inventor.

U.S. Army Model 1862 Percussion Signal Pistol, circa 1862. / THF170773

The U.S. Navy showed high interest in Martha's invention, but stalled the purchase of the patent until 1861, after the Civil War erupted. With a blockade of Southern ports in place, the Navy needed Martha's flares to communicate. Her business, the Coston Manufacturing Company, produced the flares and sold them at cost for the duration of the war. New York gun manufacturer William Marston produced the signal pistol above to exclusively fire Coston's multicolored signal flare.

A carte-de-visite depicting the "Official Escorts for the Japanese Ambassador's Visit to the United States,” circa 1860. Admiral David Dixon Porter is pictured right. / THF211796

In her 1886 autobiography, A Signal Success: The Work and Travels of Mrs. Martha J. Coston, Martha acknowledged the use of her flares in the success of the blockade. Confederate ships known as blockade-runners regularly sailed at night, and Coston's flares helped Union ships pursue these runners effectively, often resulting in prize money for the ship's officers. Admiral David Porter, pictured on the right above, wrote Martha about the impact her flares had on military operations, saying:

"The signals by night are very much more useful than the signals by day made with flags, for at night the signals can be so plainly read that mistakes are impossible, and a commander-in-chief can keep up a conversation with one of his vessels."

In January 1865, Wilmington, North Carolina, remained the last open port of the Confederacy. To cut the port off, Admiral David Porter and Major General Alfred Terry coordinated a joint assault of sea and land forces. The ensuing conflict, known as the Battle of Fort Fisher, resulted in a Union victory.

Illustration from an 1865 Harper's Weekly depicting the fall of Fort Fisher. / THF287568

According to Admiral Porter, Martha Coston's flares played a critical role. He later reminisced, "I shall never forget the beautiful sight presented at ten o'clock at night when Fort Fisher fell.... The order was given to send up rockets without stint and to burn the Coston Signals at all the yard-arms."

After the war, Martha Coston continued to improve upon her invention, filing several more patents—this time in her own name. When the United States Life-Saving Service, precursor to the United States Coast Guard, began using the Coston flare, Martha's invention became standard safety equipment for all boating vessels. Worldwide adoption of her invention led to the success of Martha's business, Coston Supply Company, which focused on maritime safety and stayed in business until the late 20th century.

Illustration from an 1881 Harper's Weekly depicting the United States Life-Saving Service using the Coston flare. / THF287571

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Washington DC, 19th century, women's history, inventors, Civil War, by Ryan Jelso, #THFCuratorChat

"The Better Angels of Our Nature": President Lincoln's First Inaugural Address

Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States / THF118582

March 4, 1861: Inauguration Day. Abraham Lincoln, the President-elect, takes the oath of office to become the 16th President of the United States. It was an uncertain time. The country was torn over the issue of slavery. For years, a tenuous arrangement had been maintained between free and slaveholding states, but now many Americans—on both sides—seemed unwilling to compromise. The Democratic Party had fractured over the issue. Two Democrats and a former Whig, each with differing views, vied to become president in 1860. This left the Republican Party, which wanted to limit slavery, with an opportunity for an electoral victory.

Lincoln, the Republican Party candidate, was elected by a minority of eligible voters, winning mainly Northern and Western states—enough for an electoral majority—but receiving little or no support from the slaveholding South. Since Lincoln's election in November 1860, seven Southern states had seceded from the Union, and many Americans feared the other eight slave states would follow. Americans anxiously waited to hear from their new president.

Campaign Button, 1860 / THF101182

In his inaugural address, Lincoln tried to allay the fears and apprehensions of those who perceived him as a radical and those who sought to break the bonds of the Union. More immediately, his address responded to the crisis at hand. Lincoln, a practiced circuit lawyer, laid out his case to dismantle the theory of secession. He believed that the Constitution provided clear options to change government through scheduled elections and amendments. Lincoln considered the more violent option of revolution as a right held by the people, but only if other means of change did not exist. Secession, Lincoln argued, was not a possibility granted by the founders of the nation or the Constitution. Logically, it would only lead to ever-smaller seceding groups. And governing sovereignty devolved from the Union—not the states, as secessionists argued. Finally, if the Constitution was a compact between sovereign states, then all parties would have to agree to unmake it. Clearly, President Lincoln did not.

Lincoln did not want conflict. His administration had yet to govern, and even so, he believed that as president he would have "little power for mischief," as he would be constrained by the checks and balances framed in the Constitution. Lincoln implored all his countrymen to stop and think before taking rash steps. But if conflict came, he would be bound by his presidential oath to “preserve, protect, and defend” the government.

Lincoln concluded his case with the most famous passages in the speech—a call to remember the bonds that unify the country, and his vision of hope:

"I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."

Lincoln's appeal, however, avoided the cause of the onrushing war—slavery. Failing to take this divisive issue head-on only added to its polarizing effect. Many Americans in the North found Lincoln's speech too conciliatory. Southerners thought it threatened war. And the nation had little time to stop and think. Immediately after his inauguration, Lincoln had to decide whether to resupply Fort Sumter, the U.S. military post in Charleston harbor, the heart of secession. In April, the "bonds of affection" broke.

Lincoln had hoped that time and thoughtful deliberation would resolve this issue—and in a way it did. The tragedies of war empowered Lincoln to reconsider his views. His views on slavery and freedom evolved. No longer bound, Lincoln moved toward emancipation, toward freeing enslaved Americans, and toward his "better angels."

Engraving, "The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet" / THF6763

To read Lincoln's First Inaugural Address, click here.

Andy Stupperich is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1860s, Washington DC, 19th century, presidents, Civil War, by Andy Stupperich, Abraham Lincoln

The Incredible Life of Frederick Douglass

The story of Frederick Douglass’s life is, at turns, tragic and awe-inspiring. He is a testament to the strength and ingenuity of the human spirit. The Henry Ford is fortunate to have some materials related to Douglass, as well as to the many areas of American history and culture he touched. What follows is an exploration of Frederick Douglass’s story through the lens of The Henry Ford’s collection, using our artifacts as touchpoints in Douglass’s life.

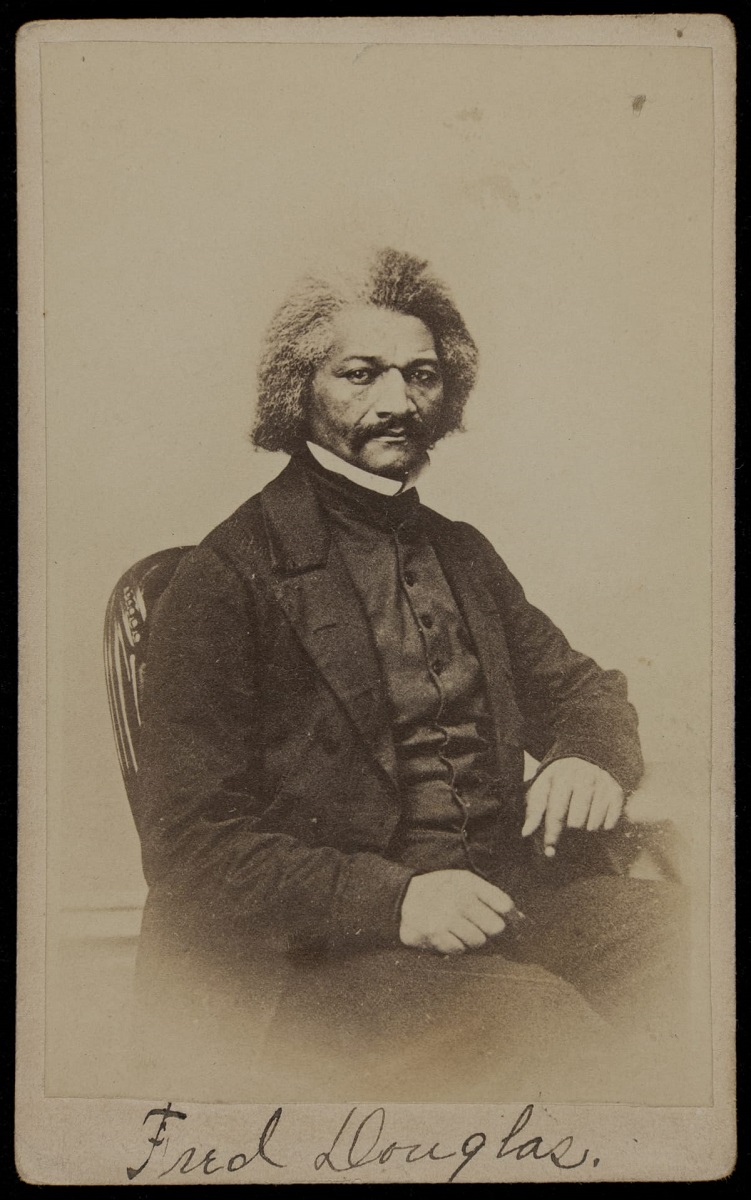

This portrait of Douglass was taken circa 1860, around the time Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States. / THF210623

Early Life & Escape

Born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, Frederick Douglass was named Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey by his enslaved mother, Harriet Bailey. Tragically, Douglass only saw his mother a few times before her early death, when Douglass was just seven years old. Though he had few memories of his mother, he recalled her fondly and was proud to learn that she also knew how to read. He wrote that he was “quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess” to his mother. Few enslaved people could read at that time—Douglass’s pride in his mother was certainly justified.

In 1826, Douglass was sent to Baltimore, Maryland, to live with the family of Hugh and Sophia Auld—extended family of his master, Aaron Anthony. This move to Baltimore would be transformative for Douglass. It not only exposed Douglass to the wider world, but was also where Douglass learned to read.

Douglass was initially taught to read by Sophia Auld, who considered him a bright pupil. However, the lessons were put to a stop by Hugh Auld. It was not only illegal to teach an enslaved person to read, but Hugh also believed literacy would “ruin” Douglass as a slave. In a sense, Douglass agreed, as he came to understand the vast power of literacy. Douglass would later remark that “education and slavery are incompatible with each other.”

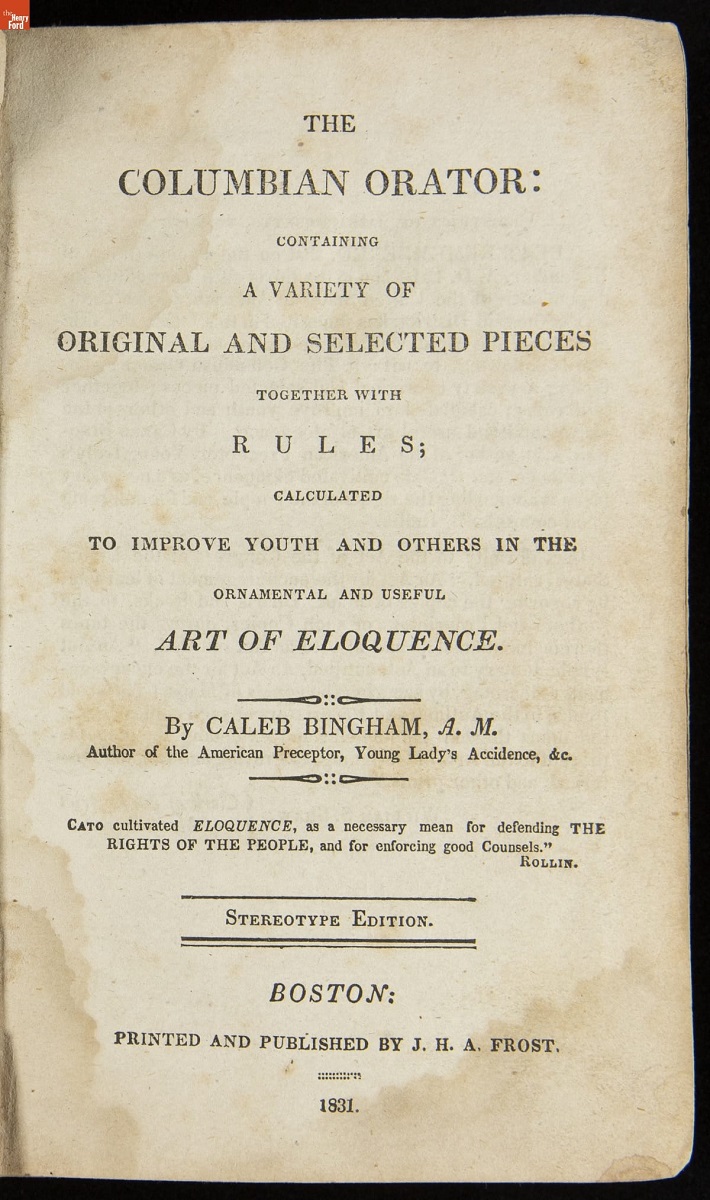

Douglass was determined to read. He “converted to teachers” some of the friendlier white children in the neighborhood. They showed him a school reader entitled The Columbian Orator, by Caleb Bingham, that he came to rely upon. In 1830, he purchased his own copy for 50 cents. The book—a collection of exceptional oration, poems, dialogue, and tips on the “art of eloquence”—became a great inspiration to Douglass. He carried it with him for many years to come.

“The Columbian Orator” features a discussion between an enslaved person and their master which impressed Douglass. The enslaved person’s dialogue—referred to as “smart” by Douglass—resulted in the man’s unexpected emancipation. / THF621972, THF621973

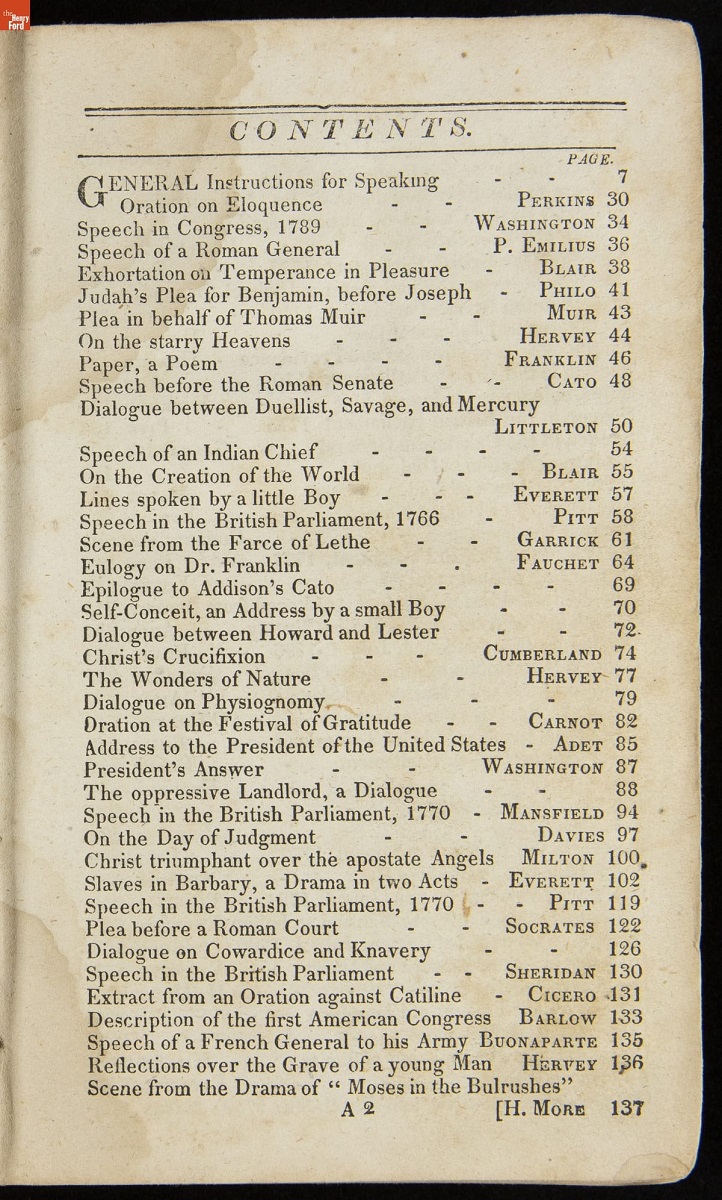

As recollected in his first memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, published in 1845, Douglass’s teenage years were some of his most challenging. He became viewed as a “troublemaker.” He was hired out to different farmers in the area, including one who had the reputation as an “effective slave breaker” and was especially cruel. Knowing that a larger world awaited and facing a terrible quality of life, Douglass attempted an escape in 1836. The escape failed and he was put in jail. Douglass was surprised to be released. He was sent not to the deep South as he had feared, but instead, back to Baltimore and the family of Hugh Auld, to learn the trade of caulking at the shipyards. While working there, Douglass was subjected to the animosities of his white coworkers, who beat him mercilessly—and were never arrested for it because a white witness would not testify and the word of a Black man was not admissible. He continuously dreamt of escape.

In this first memoir, Douglass provides great detail into his early life. However, because he was still a fugitive at the time of publication, he omitted details related to his escape. / THF8133

Recalling the ships on Chesapeake Bay, Douglass wrote:

“Those beautiful vessels, robed in purest white, so delightful to the eye of the freemen, were to me so many shrouded ghosts, to terrify and torment me with thoughts of my wretched condition. You are loosed from your moorings and are free; I am fast in my chains and am a slave! You move merrily before the gentle gale, and I sadly before the bloody whip!”

The ships’ freedom taunted him.

On September 3rd, 1838, Douglass courageously escaped slavery. Dressed as a sailor and using borrowed documents, he boarded a train, then a ferry, and yet another train to reach New York City—and freedom. His betrothed, Anna Murray Douglass, a free Black woman, followed, and soon after they were married. Frederick and Anna Murray Douglass moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, with hopes that Frederick could find work as a caulker in the whaling port. Instead, he took on a variety of jobs—but, finally, the money he earned was fully his. It is believed that Anna Murray Douglass played a crucial role in supporting Frederick's escape. Their shared commitment to freedom made them a formidable team in the fight against slavery.

The American Anti-Slavery Society & the Abolitionists

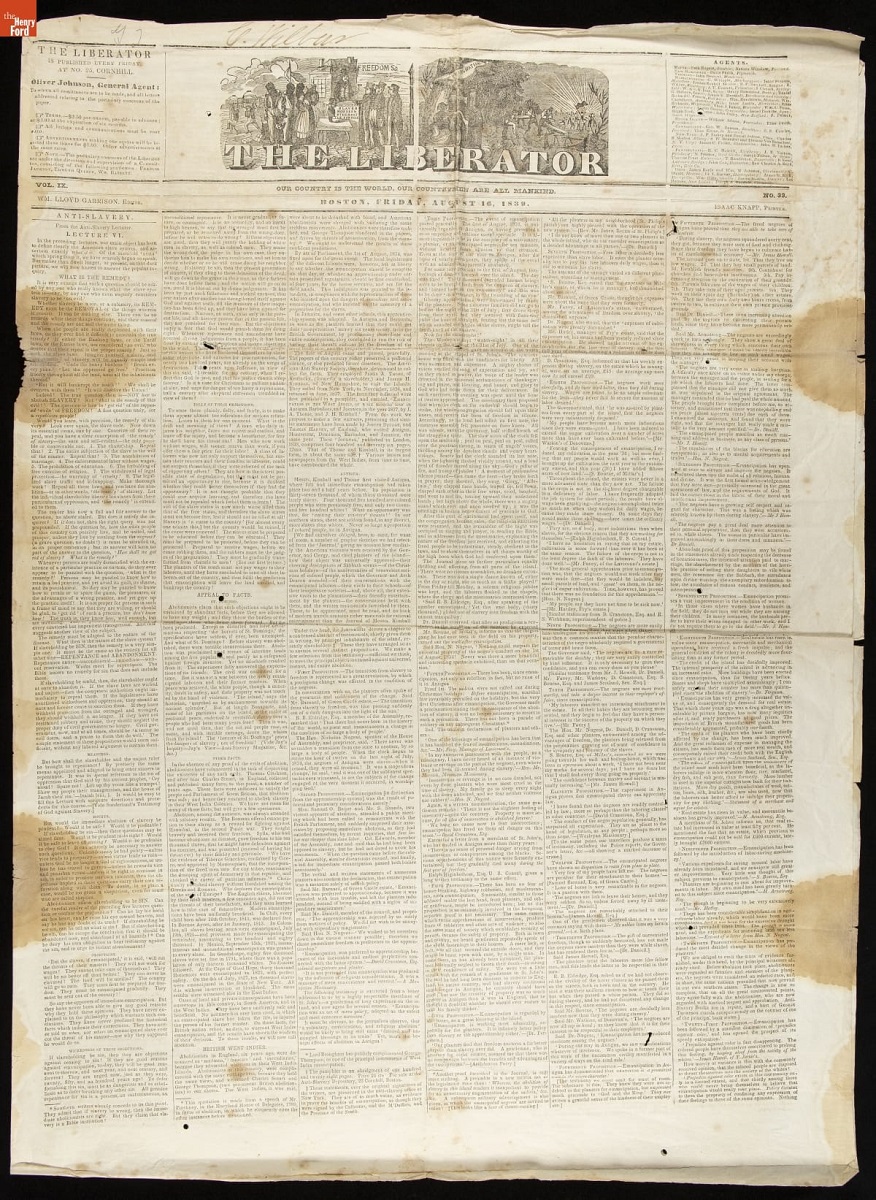

While living in New Bedford, Douglass encountered William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, for the first time. Douglass later wrote that the paper “took its place with me next to the Bible.” The Liberator introduced to Douglass the official abolitionist movement. This was a pivotal moment in his journey to becoming a prominent abolitionist leader.

In August of 1841, Douglass attended an abolitionist convention. In an impromptu speech, he regaled the audience with stories of his enslaved past. William Lloyd Garrison and other leading abolitionists noticed—Douglass’s career as an abolitionist orator had begun. Douglass became a frequent speaker at meetings of the American Anti-Slavery Society. His personal story of life enslaved humanized the abolitionist movement for many Northerners—and eventually, the world. His powerful speeches resonated deeply, inspiring many to join the cause.

In 1845, he published his first memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. By 1847, it had already sold more than 11,000 copies! This would be followed by two more memoirs: My Bondage and Freedom in 1855 and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in 1881. These narratives became essential texts in the abolitionist movement and the aftermath of the Civil War, providing firsthand accounts of the horrors of slavery.

This copy of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator was published on August 16, 1839—around the time when Douglass first encountered the paper. / THF621979

Women’s Suffrage

Douglass was also supportive of the women’s suffrage movement. He spoke at the famous Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 in support of women’s rights. In fact, the motto of his newspaper, The North Star, was “Right is of no sex—Truth is of no color—God is the Father of us all, and we are brethren.”

While Douglass forcefully supported women’s suffrage, some of his actions put him at odds with others in the movement. He supported the adoption of the 14th amendment, ratified in 1868, which guaranteed equality to all citizens—which included Black and white males, including the formerly enslaved. It did not include women. He also supported adoption of the 15th amendment, ratified in 1870, which secured Black males voting rights. Again, the amendment excluded women. Although a dedicated women’s rights activist, Douglass supported the adoption of the 14th and 15th amendments as he believed the matter to be “life or death” for Black people. This put him in disagreement with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, two of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement, as well as his friends. Despite this disagreement about timing, Douglass would continue to lecture in support of women’s equality and suffrage until his death.

John Brown’s Raid

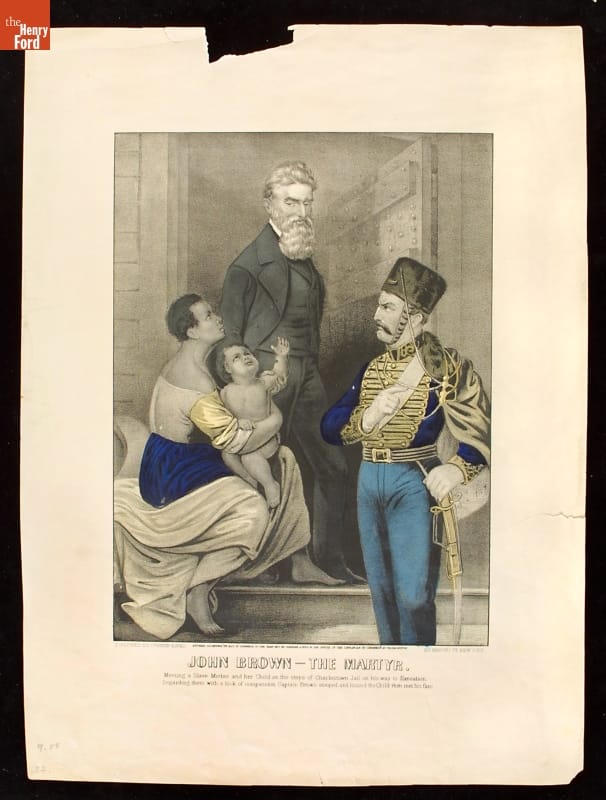

Douglass was well-acquainted with famous abolitionist leader John Brown, first meeting him in 1847 or 1848. Brown became known for leading a raid on the armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, intending to create an “army of emancipation” to liberate enslaved people. Douglass and Brown spoke shortly before John Brown’s raid. Brown had hoped that Douglass would join him, but Douglass declined. He believed that Brown was “going into a perfect steel trap, and that once in he would not get out alive.”

Douglass was right. Brown was captured during the raid and was subsequently tried, convicted, and executed. Brown became seen as an anti-slavery martyr, as the below print shows. Henry David Thoreau remarked about him, “No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature…”

A letter from Douglass was found among John Brown’s belongings, leading to warrants for Douglass’s arrest as a conspirator. He was lecturing in Philadelphia at the time of the discovery. John Hurn, Philadelphia’s telegraph operator, was sympathetic to the abolitionist cause. He received a dispatch for the sheriff calling for Douglass’s arrest and both sent a warning to Douglass and delayed relaying the dispatch to the sheriff. Douglass fled and made it to Canada, narrowly escaping arrest. He then went abroad on a lecture tour, resisting apprehension in the States.

The text on this Currier & Ives print reads “John Brown—The Martyr: Meeting a Slave Mother and her Child on the steps of Charlestown Jail on his way to Execution. Regarding them with a look of compassion Captain Brown stooped and kissed the Child then met his fate." This did not actually occur, but became popular lore, as well as the subject of artwork and literature. / THF8053

The Civil War & Abraham Lincoln

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. At the time, Douglass was not optimistic about the cause of abolition under Lincoln’s presidency. As tensions between the North and South grew and Civil War loomed, Douglass welcomed the impending war. As biographer David Blight states, “Douglas wanted the clarity of polarized conflict.”

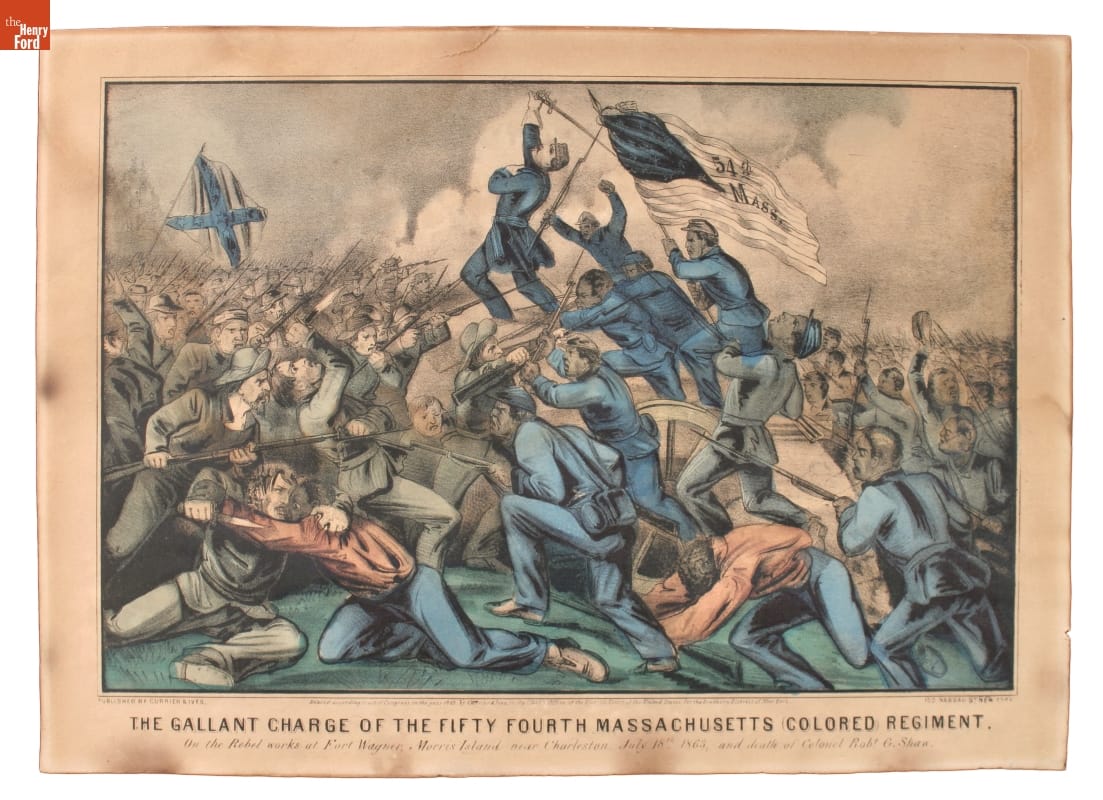

Douglass got involved in the war effort through the recruitment of Black soldiers. Two of his sons, Charles and Lewis, joined the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the second Black regiment in the Union Army. Douglass first met President Abraham Lincoln in August 1863, when he visited the White House to discuss grievances against Black troops. Even without an appointment and a room full of people waiting, Douglass was admitted to see Lincoln after just a few minutes.

Two of Frederick Douglass’s sons, Lewis and Charles, fought with the 54th Massachusetts Colored Regiment. Lewis Douglass was appointed Sergeant Major, the highest rank that a Black person could then hold. / THF73704

Douglass would go on to advise Lincoln over the following years. After Lincoln’s second inaugural address, he asked Douglass his thoughts about it, adding, “There is no man in these United States whose opinion I value more than yours.”

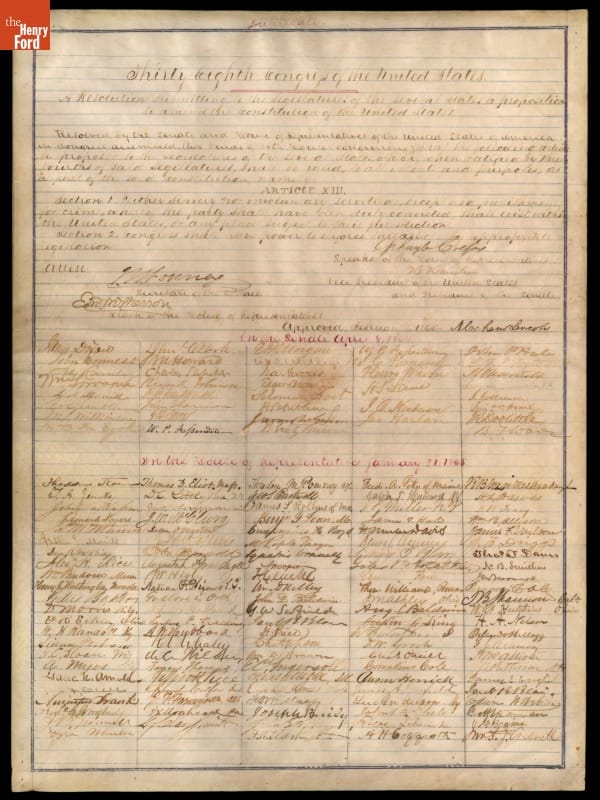

On February 1, 1865, Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of the United States Congress proposing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution—the “nail in the coffin” for the institution of slavery in the United States. But before the 13th Amendment could be ratified, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on April 15, 1865. While Douglass and Lincoln certainly disagreed on many topics, Douglass remembered him fondly. In his eulogy, Douglass called Lincoln “the Black man’s president: the first to show any respect to their rights as men.”

After the Civil War and even after Reconstruction, Douglass held high-ranking government appointments—often becoming the first Black person to do so. Douglass was appointed the Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti in 1889.

While Douglass certainly supported the 13th Amendment’s abolition of slavery, he did not think it went far enough. He remarked, “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot. While the legislatures of the south retain the right to pass laws making any discrimination between black and white, slavery still lives there.” / THF118475

Douglass continued to lecture in support of his two primary causes—racial equality and women’s suffrage—until the very end. On February 20, 1895, he attended a meeting of the National Council of Women, went home, and suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 77 years old.

Frederick Douglass remains one of the most inspirational figures in American history. We can still feel the weight of the words he wrote and spoke, more than 125 years after his passing. Douglass said, “Memory was given to man for some wise purpose. The past is … the mirror in which we may discern the dim outlines of the future and by which we may make it more symmetrical.” This work continues.

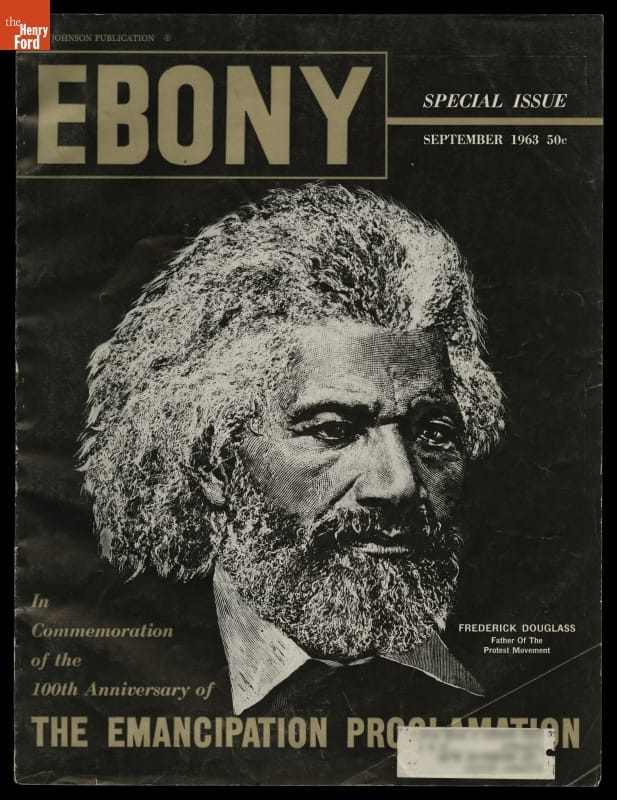

Frederick Douglass remains a powerful symbol of the fight for racial justice and equality. Here, his image graces the cover of Ebony Magazine’s issue celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. / THF98736_REDACTED

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. She appreciated the recently published book by David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, as she conducted research for this post.

Maryland, women's history, voting, Massachusetts, education, Civil War, Civil Rights, by Katherine White, books, African American history, Abraham Lincoln, 19th century, #THFCuratorChat

Anniversary of the Thirteenth Amendment

Joint Resolution of the United States Congress, Proposing the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery, February 1, 1865 / THF118475

December 6, 2020, marks the 155th anniversary of the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, which legally abolished slavery.

The Emancipation Proclamation, first made public by President Abraham Lincoln in September 1862, laid the foundation for this amendment. With this presidential proclamation and executive order, President Lincoln hoped to counteract severe Union losses during the Civil War by calling on all Confederate states to rejoin the Union within 100 days (by January 1863) or the proclamation would declare enslaved people “thenceforward, and forever free.” On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln proceeded to sign this document, announcing freedom to all enslaved people in the Confederacy. It helped enlist needed support for the war from abolitionists and pro-union and anti-war supporters. But it was not a legal document, and Lincoln knew it.

President Lincoln and his allies in Congress soon began working to enact a constitutional amendment that would legally abolish slavery. Various versions were brought before Congress until, on April 8, 1864, the strongly pro-Union Senate approved this version of the Thirteenth Amendment as we know it today:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

However, this amendment failed to pass in the House of Representatives, whose members were more split on their views. The amendment stalled until November of that year, when, upon his own reelection and with like-minded Republican gains in the House, President Lincoln urged members of the Congress to reconsider the measure and give it their utmost urgency. He enlisted members of his Cabinet and selected allies in the House to help him sway enough House member votes for the amendment to pass.

On January 31, 1865, it barely squeaked by with the requisite two-thirds majority. Upon learning of the final vote, pro-Union and anti-war members of the House erupted in shouts and cheers, while outside spectators who had filled the Capitol’s galleries (both Black and white) wept tears of joy.

On February 1, 1865, members of Congress signed this Joint Resolution of the Thirteenth Amendment, indicating that it had passed by both the Senate and the House of Representatives but had yet to receive state ratification. Although not legally required to do so, President Lincoln signed it as well. Immediately, Lincoln’s foes in both Congress and the press criticized him for wielding unseemly presidential power. But Lincoln was undeterred. Celebrating that evening, Lincoln happily announced, “This amendment is a King’s cure for all evils. It winds the whole thing up.”

It did help wind up the war. Its primary motive was, in fact, to preserve the Union by destroying the cornerstone of the Southern Confederacy. Sadly, on April 15, just as the war was winding down, President Lincoln was assassinated. Afraid that slavery might be re-established by individual states, Radical Republicans in Congress determinedly pushed the Thirteenth Amendment forward for state ratification. It was finally ratified by the requisite three-quarters of states on December 6, 1865—the date we are now commemorating.

Unfortunately, the Thirteenth Amendment was not a “cure for all evils.” Some Southern states were already instituting black codes, denying African Americans basic rights. The Thirteenth Amendment was followed by a Fourteenth and a Fifteenth—legally guaranteeing African Americans the basic rights of citizenship and the ability to vote. But these were just legal documents. Enforcing them was another matter, one fraught with violence and discrimination. African Americans would face an ongoing struggle for freedom and justice.

This is one of a limited number of original manuscript copies known to survive of the February 1, 1865, Joint Resolution of the US Congress, proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery. Lincoln’s signature was added by another hand.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

presidents, 1860s, 19th century, Civil War, Civil Rights, by Donna R. Braden, African American history, Abraham Lincoln

Freedmen’s Bureau: Exercising Citizenship

President Abraham Lincoln signed The Freedmen’s Bureau Act on March 3, 1865. That Act created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands as part of the War Department. It provided one-year of funding, and made Bureau officials responsible for providing food, clothing, fuel, and temporary shelter to destitute and suffering refugees behind Union lines and to freedmen, their wives, and children in areas of insurrection (in other words, within the Confederate States). The legislation specified the Bureau’s administrative structure and salaries of appointees. It also directed the Bureau to put abandoned or confiscated land back into production by allotting not more than 40 acres to each loyal refugee or freedman for their use for not more than three years, at a rent equal to six percent of its 1860 assessed value, and with an option to purchase. The Bureau assumed additional duties in response to freed people’s goals, namely building schools, negotiating labor contracts, and mediating conflicts.

Lincoln supported the Bureau because it fit his plan to hasten peace and reconstruct the nation, but after Lincoln’s assassination, support wavered. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1866 provided two years of funding. During 1868, increasing violence and for a return to state authority undermined the goals of freed people and the Bureau that worked for them. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1868 authorized only the educational department and veteran services to continue. All other operations ceased effective January 1, 1869.

Collections at The Henry Ford help document public perceptions of the Freedmen’s Bureau as well as actions taken by Bureau advocates. Letters, labor contracts, and newspapers indicate the contests that played out as the Bureau tried to introduce a new model of economic and social justice and civil rights into places where absolute inequality based on human enslavement previously existed. The Bureau did not win the post-war battle for freedmen’s rights. Congress did not reauthorize the Bureau, and it ceased operations in mid-1872.

The Beginning

Bureau appointees went to work at the end of the Civil War in 1865 to serve the interests of four-million newly freed people intent on exercising some self-evident truths itemized in the Declaration of Independence:

That all men are created equal

That they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights

That among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

Engraved Copy of the 1776 Declaration of Independence, Commissioned by John Quincy Adams, Printed 1823.

With freedom came responsibility to sustain the system of government that “We the People” constituted in 1787, and that the Union victory over secession reaffirmed in 1865. Little agreement over the best course of action existed. The national government extended the blessings of liberty by abolishing slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865. It established the Freedmen’s Bureau which advocated for the general welfare of newly freed people.

Book, "The Constitutions of the United States, According to the Latest Amendments," 1800. THF 155864

Expanding liberty and justice came at a price, both economic and human. Every time freed people exercised new-found liberty and justice, others resisted, perceiving the expansion of another person’s liberty as a threat to their own. The Bureau operated between these factions, as an 1868 illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicted. The newspaper claimed that the Bureau was “the conscience and common-sense of the country stepping between the hostile parties, and saying to them, with irresistible authority, ‘Peace!’.”

“The Freedmen’s Bureau,” Harper’s Weekly, July 25, 1868, pg. 473. 2018.0.4.38. THF 290299

Economics

Building a new southern economy went hand in hand with expanding social justice and civil rights. Concerned citizens and commanding officers knew that African Americans serving in the U.S. Colored Troops had money to save. They started private banks to meet the need. The U.S. Congress responded with "An Act to Incorporate the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company." Lincoln signed the legislation on March 3, 1865, the same day he signed “An Act to Establish a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees.” Agents of the public Freedmen’s Bureau worked closely with staff at the private Freedman’s Bank because freed people needed the economic stability the bank theoretically provided.

At least 400,000 people, one tenth of the freed population, had an association with a person who opened a savings account in the 37 branches of the savings bank that operated between 1865 and 1874. This included Amos H. Morrell, whose daughter’s heirs resided in the Mattox House. Soldiers listed on the Muster Roll of Company E, 46th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry, also appear in records of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. Charles Maho, a private in Company E, 46th USCT, opened an account on August 13, 1868. He worked in a tobacco factory at the time. His brother in arms, James Parvison/Parkinson, also a private, opened an account on December 1, 1869 and his estranged wife, Julia Parkerson opened an account on May 14, 1870.

Mattox Family Home, circa 1880

Freedmen’s Bureau officials encouraged deposits into the Freedmen’s Bank. This helped freed people become accustomed to saving the coins they earned, literally the coins that symbolized their independence as wage earners. Sadly, Bureau officials often assured account holders that their investments were safe. The deposits were not protected by the national government, however, and when the bank closed in 1874 it left depositors penniless and petitioning for return of their investments.

One-cent piece. Minted in 1868. THF 173625 (front) and THF 173624 (back)

Three-cent piece (made of nickel). Minted in 1865. THF 173623 (front) and THF 173622 (back).

The U.S. Congress authorized the Bureau to collect and pay out money due soldiers, sailors, and marines, or their heirs. Osco Ricio, a private in Company E, 46th U.S. Colored Infantry, who enlisted for three years in 1864, but was mustered out in 1866, made use of this service in his effort to secure $187 due him.

Freedmen’s Bureau staff mediated between freed people and employers, negotiating contracts that specified work required, money earned, and protection afforded if employers reneged on the agreement. A blank form, printed in Virginia in 1865, included language common to an indenture – that the employer would provide “a sufficiency of sound, wholesome food and comfortable lodging, to treat him humanely, and to pay him the sum of _____ Dollars, in equal monthly instalments of ____ Dollars, good and lawful money in Virginia.”

Freedman's Work Agreement Form, Virginia, 1865 Object ID 2001.48.18. THF 290704

Another pre-printed form reinforced terms of enslavement, that the work should be performed “in the manner customary on a plantation,” even as it confirmed the role of Freedmen’s Bureau agents as adjudicator. Freedman Henry Mathew, and landowner R. J. Hart, in Schley County, Georgia, completed this contract which legally bound Hart to furnish Mathew “quarters, food, 1 mule, and 35 acres of land” and to “give. . . one-third of what he [Mathew] makes.” This type of arrangement became the standard wage-labor contract between landowners and sharecroppers, paid for their labor with a share of the crops grown on the land.

Freedman's Contract for a Mule and Land, Dated January 1, 1868. THF 8564

Many criticized sharecropping as another form of unfree labor rather than as a fair labor contract. Close reading confirms the inequity which often took the form of additional work that laborers performed but that benefitted owners. In the case of Hart and Mathew, Mathew had to repair Hart’s fencing which meant that Mathew realized only one-third return on his labor investment in the form of a crop perhaps more plentiful because of the fence. Hart claimed the other two-thirds of the crop plus all of the increased value of fencing.

Education

Freed people wanted access to education to learn what they needed to make decisions as informed and productive citizens.

Harper’s Weekly, a New York magazine, often featured freedmen’s schools that resulted from a cooperative agreement between the Freedmen’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association (AMA), based in New York. A reporter informed readers on June 23, 1866 that “the prejudice of the Southern people against the education of the ‘negroes’ is almost universal.” Regardless, freed people needed schools, teachers, and institutes to train teachers. The Freedmen’s Bureau and its partners committed their resources in support of this cause.

Commentary accompanying an illustration of the “Primary School for Freedmen” indicated that the school building was dilapidated and owned by someone who wanted rid of the school, but the students were eager to learn and as capable as other students of their age in New York public schools.

“Primary School for Freedmen, in Charge of Mrs. Green, at Vicksburg, Mississippi, Harper’s Weekly, June 23, 1866, pg. 392 (bottom), story on pg. 398. THF 290712

School curriculum often emphasized agricultural and technical training. The “Freedmen’s Farm School,” located near Washington, D.C., also known as the National Farm-School, taught orphans and children of U.S. Colored Troops reading, writing and arithmetic, standard primary school subjects. Students also cultivated a one-hundred-acre farm. The combination compared to a new effort launched with the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 to create a system of colleges, federally funded but operated at the state level to train students in agricultural and mechanical subjects. The combination could help students realize the American dream – owning and operating their own farm. While the system of land-grant colleges grew steadily during Reconstruction, the freedmen’s schools faced opposition locally and at the state level. Increasingly educators turned to philanthropists to fund education for freed people.

Struggles

The individuals appointed to direct the Freedmen’s Bureau often had military experience. Brigadier General Oliver Otis Howard served in the Union Army and gained a reputation as a committed abolitionist if not a strong officer. President Andrew Johnson appointed him the first Commission of the Bureau, and he remained in that position until the Bureau closed in 1872. Two years later Howard lamented lost opportunities: “I believe there are many battles yet to be fought in the interest of human rights”….“There are wrongs that must be righted. Noble deeds that must be done.”

Many shared Howard’s frustrations with the lack of public support for freed people’s goals. They also resented the obstructions that thwarted those goals. Newspaper reporting, such as the regular features in Harper’s Weekly, emphasized the good work of the Freedmen’s Bureau, but reporting also threatened projects aimed at sustaining the momentum.

Henry Wilson, a Republican Senator from Massachusetts, sought equality for African Americans. He took a correspondent to the Republican, a newspaper in Springfield, Massachusetts, to task for publishing misinformation about the extent of congressional fundraising for political purposes, and for downplaying the need for sharing facts with voters, especially the 700,000 Southerners newly enfranchised after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. Wilson explained that hundreds of thousands of documents, possible through the congressional fundraising, could educate voters about issues and prepare them for the upcoming election. Without donations from U.S. congressmen, Wilson believed such efforts would fail.

The End

The short life but complicated legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau leaves much to ponder. The Bureau, as a part of the War Department, and then an independent national agency, mediated local conflict and supported local education. This occurred at an exceptional time as the Union began rebuilding the nation in 1865. Then, the Republican party interpreted the U.S. Constitution as a mandate for the national government to protect civil rights broadly defined. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, incorporated newly freed people as full citizens. Most believed that the Bureau had no more work to do, and Congress did not reauthorize it after July 1872. Those who favored the Bureau lamented its abrupt end and believed that much remained to be done to open the American experiment in equal rights to all.

Debra Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Sources and Further Reading

- African American Records: Freedmen’s Bureau, National Archives and Records Administration

- Carpenter, John A. Sword and Olive Branch: Oliver Otis Howard (1999)

- Cimbala, Paul A. The Freedmen's Bureau: Reconstructing the American South after the Civil War (2005)

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988).

- Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (1979).

- McFeely, William S. Yankee Stepfather: General O.O. Howard and the Freedmen (1994).

- Osthaus, Carl R. Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedman's Savings Bank (1976)

- Oubre, Claude F. Forty Acres and a Mule: The Freedmen’s Bureau and Black Land Ownership (2012).

- Washington, Reginald. “The Freedman's Savings and Trust Company and African American Genealogical Research,” Federal Records and African American History (Summer 1997, Vol. 29, No. 2)

1870s, 1860s, 19th century, Civil War, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Stories of the USCT

”We are Bound for Glory with a Fair Wind, Nothing but Working and Fighting Ahead.” – Samuel Chapman Armstrong, Lt. Col., 9th USCT, between Hilton Head, South Carolina and Petersburg, VA, 1864

The American Civil War was the seminal event affecting daily life and ideals about freedom and citizenship during the 1860s and beyond. People coped with the reality of war-time devastation in a variety of ways. As the Civil War generation passed during the late 1920s and 1930s, when the collections of The Henry Ford were forming, the sacred family mementos that associated with personal memories of pride, honor and glory became part of this great museum of the American experience. Even though The Henry Ford is not a military history museum, the collections are rich with Civil War photographs and letters, battlefield relics, and even a medal of honor. The war is deeply imbedded in the collective memory of 19th and early 20th century Americans, and it was so often included in the “archives” of their lives that, by default, their mementos became part of our collections.

Henry Ford’s own interest in documenting the lives of his parents and his own childhood and young adulthood, caused him to collect his own family’s rich Civil War stories. Two of Henry’s mother’s brothers, John and Barney Litogot, served in the storied 24th Michigan. John was killed near Fredericksburg, Virginia, and Barney survived to fight in many battles, including Gettysburg. He also served in the honor guard at Abraham Lincoln’s funeral.

John and Barney Litogot at the time of their enlistment, August, 1862. THF 226852

The variety of Civil War objects in the collection is amazing, and represents both Union and Confederate perspectives.

Keeping troops in the field proved challenging for the Confederacy and the Union. A broadside confirms pay scales for Union troops and employees of the United States Army.

Recruiting Broadside, United States Army, c1863. THF 8551

Lackluster enlistment, however, prompted both armies to institute conscription. The Confederacy did this in April 1862 and the Union followed in March 1863.

The U.S. Army issued broadsides to recruit soldiers, including men of African descent, after passage of the Emancipation Proclamation. One broadside in the collection depicts a white male standard bearer front and center and elevated above others in the scene. He is armed with a sword and the banner, “Freedom to the Slave.” To the left sits a public school and a black man reading a newspaper rather than manning the plow. This implied that education and literacy could free people from manual labor. To the right, a black soldier aids black women and children recently freed from the shackles of slavery while black troops fight in the background.

“Freedom to the Slave. . . Fight for the Stars and Stripes,” 1863-1865. THF 118383

Black men had opportunities to serve in the Union forces before the Emancipation Proclamation. In fact, in May 1862, General David Hunter, in command of occupying forces in Hilton Head, South Carolina, organized the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. He acted without permission of the War Department and reputedly impressed men enslaved on plantations in the occupied territory into service. This sparked controversy about whether contraband of war, the enslaved in occupied territory, could, or should, serve in the military. The regiment disbanded in August 1862

Wood Engraving, First and Last Dress Review of 1st Regiment South Carolina (Negro) Volunteers, 1862. THF 11672.

The Militia Act on July 1, 1862 made it legal for the U.S. President, as commander in chief, to accept “persons of African descent” into the Union military or navy. The Militia Act authorized their pay and rations equivalent to that of soldiers already serving, but instead of $13 per month, they received $10 per month, with the remaining $3 paid in clothing). It also allowed persons of African descent to work for the Union, performing camp service and building fortifications.

Union officers reorganized the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry in November 1862, in conjunction with the Port Royal Experiment to redistribute lands on the Sea Islands of South Carolina to the formerly enslaved. Company A, under command of Charles T. Trowbridge, became the first official regiment of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) on January 1, 1863, the same day that officials read the Emancipation Proclamation for the first time, in Beaufort, South Carolina, on Port Royal Island, just south of Fort Sumter. The First South Carolina was renamed the 33rd U.S. Colored Infantry in 1864 and remained in service until January 31, 1866.

"Dress Parade of the First South Carolina Regiment (Colored) near Beaufort, South Carolina," 1861-1865. THF 8221

Stories of tragedy and triumph abound in the history of the USCT, including experiences lived by residents on our own Susquehanna Plantation.

Susquehanna as it appears in Greenfield Village today. THF 2024

Morris Robertson, an enslaved carpenter, left Susquehanna and enlisted with the Federal Army on October 25, 1863. He became a member of the 9th USCT, Company C. This regiment was organized at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland, from November 11 to December 31, 1863. They saw service in South Carolina and Virginia, including Petersburg and Richmond. Following the end of hostilities, the regiment was moved to Brownsville, Texas, where it remained until September 1866. The 9th was ordered to Louisiana in October and mustered out at New Orleans, November 26, 1866. Sadly, it was in Brownsville, Texas, very near the end of his term of service that Morris Robertson died of cholera on August 25, 1866. We would like to think that Morris’ brief time of freedom, though under frequent periods of extreme danger, gave him some joy. It is troubling to know that though free, he would never see his family again.

Service Record for Morris Robertson from the Company Descriptive Book. (Library of Congress)

Other objects in the collections document USCT in several other states, and confirms their service across the Confederate States from Virginia to south Texas. Examples include the 54th Massachusetts, perhaps the most well-known USCT regiment. It received national media attention in July 1863 for its “gallant charge” on rebel-held Fort Wagner, on Morris Island in the Charleston, South Carolina harbor.

Lithograph: GALLANT CHARGE OF THE FIFTY FOURTH (COLORED) MASSACHUSETTS REGIMENT / On the Rebel Works at Fort Wagner; Morris Island near Charleston, July 18th 1863, and the death of Colonel Robt. G. Shaw. THF 73704

USCT saw action in the Gulf of Mexico. Evidence includes a portrait of J.D. Brooker. Inscriptions on the back of the photo matte indicated that Brooker served with the Corps d’Afrique, 79th Regiment of Infantry. U.S. Army recruiters worked at the parish-level in occupied Louisiana, to attract volunteers. Troops saw heavy action during the Port Hudson campaign, May through July 1863. Major General Nathaniel P. Banks praised the Corps--"It gives me great pleasure to report that they answered every expectation. In many respects their conduct was heroic. No troops could be more determined or more daring."

Portrait of J.D. Brooker, soldier with the Corps d'Afrique 79th U.S. Colored Troops from Louisiana. THF 93151

Fragments of “our flag” were glued to the back of J.D. Brooker’s portrait.

Collections include portraits of white commanding officers of black troops.

Union Army Colonel Bernard Gains Farrar, who assisted in the siege of Vicksburg, recruited African-American troops from the area after Vicksburg fell. He commanded the 6th U. S. Colored Heavy Artillery.

Portrait of a Union Army Colonel Bernard Gains Farrar, 1862-1864. THF 6229

Lieutenant Andrew Coats, served with the 7th Colored Infantry Regiment and as Acting Assistant Adjutant General for the District of Florida. In 1864, the 7th Colored Infantry Regiment was part of the 10th Army Corps, located in the area of Hilton Head and Beaufort, South Carolina.

Portrait of Lieutenant Andrew Coats, 7th Colored Infantry Regiment, 1864. THF 57539

Americans of African descent remained the fulcrum around which debates about status and citizenship revolved. An 1864 print by Currier and Ives, conveyed this debate graphically as a contrast between the George B. McClellan, the Democratic presidential candidate, who wanted to restore the Union, but not abolish slavery, and the incumbent, Abraham Lincoln, author of the Emancipation Proclamation. If McClellan won the election, the CSA president, Jefferson Davis, would slit their throats. If President Lincoln retained his seat, black soldiers could stand at Lincoln’s right hand, defending the Union of States against CSA president Davis, in rags and on his posterior and held at bay by Lincoln. Black soldiers, however, remained culturally distinctive in the Currier and Ives depiction, as the dialect in the captioning re-enforced.

“Your Plan and Mine,” Political Cartoon, Presidential Campaign, 1864. THF 251879

Our collections also document post-war service of USCT. The Muster Roll for Company E, 46th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry confirmed the presence of men serving in the Regiment between April 30 and June 30, 1865. It also included names of at least fifteen men who had been taken as prisoners of war and men who had been discharged and deceased. The roll may have been used to keep track of soldiers after the war, perhaps for pension applications. Some annotations are dated 1885 and 1890. The Company E, 46th Regiment USCT saw action in Arkansas and the Mississippi Delta.

Another muster roll, confirmed the presence of thirteen soldiers in Company G, 25th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry, on April 12, 1865. Col. F.L. Hitchcock, commanding officer of the troops in Fort Barrancas, Florida, signed the roll. It includes details about each soldier:

Name; Rank; Date mustered in; Place mustered in; Mustered in by [name]; How long in service; Hair color; Eye color; Complexion color; Height (feet and inches); Where born; Age; Occupation; Pay information.

The 25th Regiment USCT was on garrison duty at Fort Barrancas, Florida, when these soldiers were recruited, and remained on garrison duty until December, 1865, never seeing action. During the spring and summer of 1865 about 150 men died of scurvy, the result of lack of proper food. Col. Hitchcock wrote:

"I desire to bear testimony to the esprit du corps, and general efficiency of the organization as a regiment, to the competency and general good character of its officers, to the soldierly bearing, fidelity to duty, and patriotism of its men. Having seen active service in the Army of the Potomac, prior to my connection with the Twenty-fifth, I can speak with some degree of assurance. After a proper time had been devoted to its drill, I never for a moment doubted what would be its conduct under fire. It would have done its full duty beyond question. An opportunity to prove this the Government never afforded, and the men always felt this a grievance."

Muster Roll of 13 Soldiers in Company G, 25th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry, April 12, 1865. THF 284824

As we pause to celebrate Memorial Day, a holiday with its origins linked to the Civil War, we need to pause to also honor all those who have given their lives in service, and all those who have, and continue to, serve to protect our freedoms. Americans did not agree on the meaning of freedom during the 1860s, and the evidence indicates that Americans of African descent were not given their freedom by white Americans. They fought during the Civil War to attain it.

Jim Johnson is Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes at The Henry Ford. Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

1860s, 19th century, Civil War, by Jim Johnson, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Jacket, Worn by Robert H. Hendershot, circa 1890. THF 155871

In the 1880s and 1890s, Civil War veteran Robert Hendershot wore this elaborate jacket when he played his drum at Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) events and at other community gatherings. The accompanying “souvenir” card is actually an advertisement, letting interested parties know Hendershot was available for hire.

Trade Card from Major Robert H. Hendershot, "The Original Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock," circa 1895. THF 115938

Since the 1860s, Hendershot had billed himself as “The Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock.” But was he? In December 1862, during the fighting at Fredericksburg, Virginia, reports had come of a brave young drummer boy who had crossed the Rappahannock River with the 7th Michigan Infantry under a hail of Confederate bullets. The 12-year-old Hendershot was indeed with a Michigan regiment at Fredericksburg at this time. But so were several other young drummer boys.

The controversy over who really was “The Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock” raged for decades among Civil War veterans—reports from members of Michigan units engaged at Fredericksburg offered conflicting stories. But Hendershot used his savvy promotion skills to keep his name before the public, receiving recognition from some G.A.R. members and even from prominent men like newspaper editor Horace Greeley.

Hendershot may or may not have been “The Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock.” But throughout his life, he certainly used his celebrity to his advantage.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Virginia, 19th century, 1890s, 1880s, 1860s, veterans, musical instruments, music, Michigan, Grand Army of the Republic, Civil War, by Jeanine Head Miller

The Gettysburg battlefield monument depicted in this painting honors the Michigan Cavalry Brigade. The figure of the soldier looks out over the field where this famed unit fought fiercely on July 3, 1863 to help assure Union victory on the final day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Their commander was 23-year-old Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer, promoted only three days before. Gettysburg was the Michigan Brigade's first major engagement.

This "Wolverine Brigade" fought in every major campaign of the Army of the Potomac, from Gettysburg to the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House in April 1865. A number of the surviving veterans were present at the monument's dedication in Gettysburg on June 13, 1889.

Jessie Zinn created this painting of the monument soon after. Did a proud Michigan Brigade veteran ask the 26-year-old Gettysburg artist to paint it? Did Michigan veterans commission the artwork to hang in their local Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) Hall?To learn more about Jessie's story, take a look at this special visit To Henry Ford.

Continue Reading1880s, 1860s, 1890s, 19th century, Pennsylvania, women's history, veterans, paintings, Michigan, Civil War, by Jeanine Head Miller, art