Natural History – From The Henry Ford?

As part of our continuing partnership with Google Arts & Culture, we are excited to announce the September 13, 2016, launch of “Natural History,” our third themed release on the platform! This is an interactive, dynamic and immersive discovery experience covering the diversity and fragility of nature, featuring over 170 online exhibits and 300,000 artifacts from dozens of cultural heritage institutions.

You might wonder why The Henry Ford is included in this release, alongside some of the world’s most esteemed natural history museums. The answer is that though natural history is not a collecting focus for us, the stories we tell of American innovation, ingenuity, and resourcefulness often intertwine with the flora and fauna around us—in fact, many of our stories cannot be told without careful consideration of the environment in which they transpired.

Our participation in the release includes three online exhibits telling such stories. “The Many Facets of John Burroughs” tells the story of the famed naturalist and author who became close friends with Henry Ford in his later life. The challenges faced by Henry Ford’s rubber-growing venture along the Amazon River in Brazil from the 1920s through the 1940s are explored in “Fordlandia.” And last, “Yellowstone, America’s First National Park” chronicles the development of this attempt to share America’s natural wonders with the masses—even before the birth of the National Park Service.

Our presence also includes close to 300 individual artifacts from our collections. These include objects related to each of our exhibit themes, but also significant individual artifacts such as John Muir’s pocket compass, two science texts used by the Wright Brothers and their family, and George Washington Carver’s microscope. In addition, we were very pleased to discover during our research for this project three shadowboxes of seashells collected by legendary innovator Thomas Edison in Fort Myers, Florida, an unexpected find we documented earlier this year on our blog. Prints (including several each by John James Audubon and Alexander Wilson), photographs, and other items highlighting the natural world round out our participation.

Visit g.co/naturalhistory to check out all the exhibits and artifacts within this brand new Natural History experience.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

19th century, 2010s, 21st century, 20th century, nature, John Burroughs, Google Arts & Culture, environmentalism, by Ellice Engdahl

Improvisational Quilts of Susan Allen Hunter

African-American quiltmaker Susana Allen Hunter turned the "fabric" of everyday life into eye-catching quilts with an abstract, asymmetrical, and often, modern feel. Created from the 1930s to the 1970s, Susana Hunter's quilts reflect her life in rural Wilcox County, Alabama—one of the poorest counties in the United States.

Strip Quilt by Susana Allen Hunter, 1950-1955. THF73619

Susana Hunter made handsome, unique quilts, fashioned literally from the fabric of everyday life.

Susana's quilts are pieced in a design-as-you-go improvisational style found among both blacks and whites in poorer, more isolated pockets of the rural South. People living in these more remote areas had less access to quilt pattern ideas published in newspapers or printed in books. For fabrics, rural women depended on mail order catalogs or whatever was available in the local store. These "constraints" left quiltmakers like Susana Hunter free to use their imaginations.

Bedsheet Pieced Together from Commercial Sugar Sacks by Susana Allen Hunter, 1930-1970. THF94355

Making an improvisational quilt top required a continual stream of creativity during the entire process, as the quiltmaker made hundreds of design decisions on the fly, fashioning an attractive whole out of whatever materials were at hand. Overall visual impact mattered most—not minor details such as whether a patch in a row had a square or rectangular shape. Size and shape was determined by the scraps available at the time.

Sewing Thimble Used by Susana Allen Hunter, 1930-1969. THF93486

Handmade Fan Used by Susana Allen Hunter. THF44759

For Susana and her husband Julius, life often meant hard work and few resources. The Hunters were tenant farmers who grew cotton and corn, tended a vegetable garden, and raised hogs, chicken and cattle. They lived in a simple, two-room house that had no running water, electricity or central heat. The outside world came to them through a battery-powered radio and a wind-up phonograph. Though the Hunters didn't have much in the way of material goods or the latest 20th century technology, they never went hungry, raising much of their own food.

Portrait of Susana Allen Hunter, June 1960. THF125834

Susana Hunter wanted all of her quilts to be different. Some of her quilt designs have a warm, homey feel. Many resemble abstract art. Other quilts pulsate with the visual energy created by many small, irregular pieces of vividly-colored fabric sewn together. Still others incorporate cornmeal or rice sacks, often reserved for quilt backing, as part of the design of the carefully-pieced quilt top.Susana's quilts warmed her family during chilly Alabama winters in the inadequately heated home. They added splashes of color to the unadorned living space—a cheerful kaleidoscope of vivid pattern and design against newspaper-covered walls. Susana very rarely bought new fabric for her quilts, she used what was at hand. Yet the lack of materials didn't restrict this resourceful quilter's creativity. Susana Hunter could cast her artistic eye over her pile of worn clothing, dress scraps, and left-over feed and fertilizer sacks—and envision her next quilt.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, Alabama, women's history, quilts, making, design, by Jeanine Head Miller, African American history

Edsel Ford and the National Park Service: Part 2

Part 2: Mount Desert Island, Maine

Located off the coast of Maine, Mount Desert Island is one of the largest islands in the United States and home to Acadia National Park. Long known for its rocky coast, mountainous terrain, and dense wilderness, Mount Desert Island was popularized in the mid-19th century by the Hudson River School. The painters from this art movement focused on scenic landscape paintings, creating works of art that inspired many prominent citizens from the East Coast to build their summer homes on the island. By the late 19th century a resort tradition that became locally known as "rusticating" had taken root on Mount Desert. Wealthy East Coast families known as "rusticators" would spend their summers relaxing in their island mansions, taking in the scenery, and socializing with other prosperous families doing the same. In the early 20th century, the "rusticators" on Mount Desert Island also began to include affluent Detroit families as well.

Eleanor Lowthian Clay, Edsel Ford's future wife, was accustomed to affluence and spent her summers vacationing on Mount Desert Island as a child. Eleanor's wealthy uncle, Joseph Lowthian Hudson, was successful in the Detroit department store scene. As patriarch of the family, the childless J.L. Hudson cared for his other family members and allowed Eleanor's family, as well as some of his other nieces and nephews, to live with him. Hudson employed most of them in his business and groomed his four Webber nephews, Eleanor's cousins, to take over the family trade. Their sister, Louise Webber, married Roscoe B. Jackson, a business partner of J.L. Hudson. In 1909, Jackson helped formed the Hudson Motor Car Company with backing from Hudson. Jackson had found early success with the Hudson Motor Car Company and after inheriting the department store company, the Webber brothers were able to continue its success as well. The wealth and status that these families enjoyed allowed them to later choose Mount Desert Island as the location for their summer retreats and influenced Edsel to do the same.

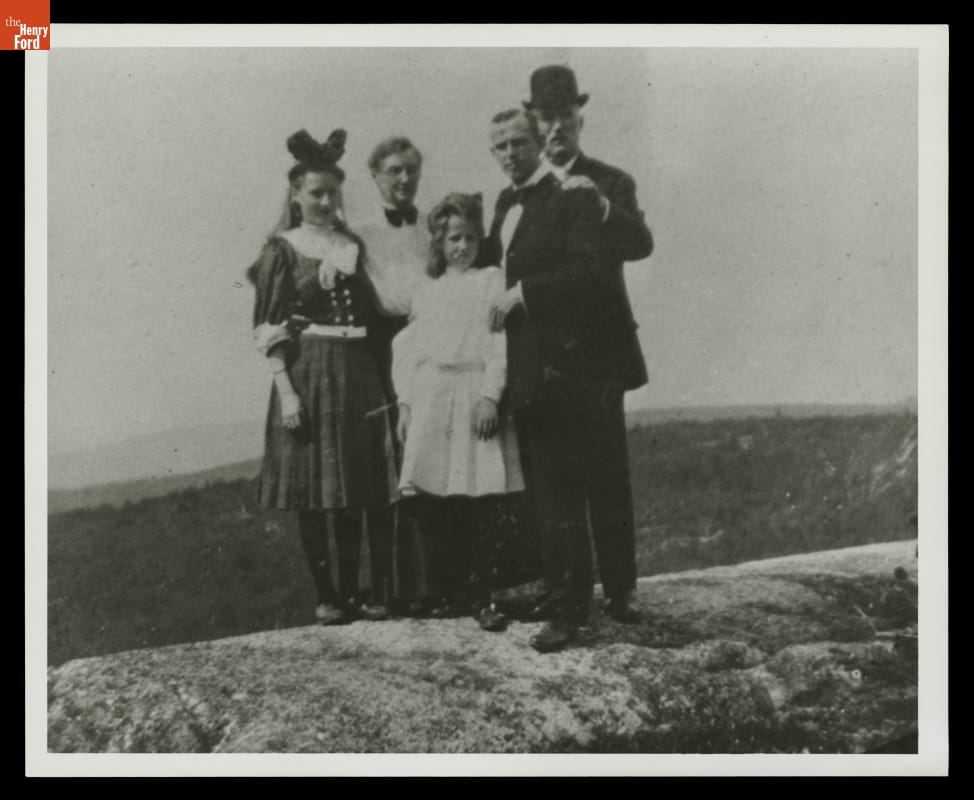

Eleanor, right, and her sister Josephine, left, vacationing in Maine with their family. THF130536

The wealth of J.L. Hudson had helped establish Eleanor's cousins and acquaint Eleanor with the son of another wealthy Detroiter in Edsel Ford. While Edsel courted Eleanor, her sister Josephine was simultaneously being courted by up-and-coming lawyer Ernest Kanzler. Edsel became close friends with Kanzler, his future brother-in-law, who eventually was hired by Henry Ford to help manage the Fordson tractor company. By the early 1920's, Edsel and Eleanor along with the Kanzlers, Webbers and Jacksons were all vacationing on Mount Desert Island. Edsel began his Mount Desert residency by renting summer homes there, occasionally inviting his parents to vacation with him. During the late summer or early fall of 1922, Edsel purchased property in the area known as Seal Harbor. Sitting 350 feet above sea level on what is known as Ox Hill, Edsel's property had a panoramic view of the surrounding sea and sky. Also within walking distance of Acadia, then Lafayette National Park, Edsel soon found that his property adjoined the property of the neighborhood national park's biggest benefactor, John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Edsel with his sons Henry II and Benson spending time at the beach in Seal Harbor. THF95355

Rockefeller Jr. first visited Mount Desert Island in 1908 and immediately became enamored with the area. He built a large estate in Seal Harbor and by the time he became neighbors with Edsel in 1922, Rockefeller Jr. had already used his wealth to donate large tracts of land to his local national park. During this time he was also in the process of building a network of carriage roads that allowed the beautiful vistas of Acadia to be accessed by the public. Preferring the quiet serenity of horse-drawn carriages over the noisy automobiles, Rockefeller Jr. worked personally with the engineers to ensure that the carriage roads captured the tranquil scenery the park had to offer. The beautiful landscapes of the area would become the topic that Rockefeller Jr. used to initiate his friendship with Edsel Ford.

Panoramic view of Seal Harbor located on Mount Desert Island, Maine. THF255236

Initially writing in December of 1922, Rockefeller Jr. didn't hide his feelings when congratulating Edsel on the purchase of his Seal Harbor property. He had visited Edsel's property at the top of Ox Hill during sunset one night and stated in his letter, "I do not know when I have seen a more magnificent and stunning view than that which met my eye on every side. You have certainly made no mistake in selecting a site for your home.” He concluded the letter by expressing how happy he and his family were at the thought of having Edsel as a permanent summer neighbor. In Edsel's gracious response to Rockefeller Jr., he mentioned that he would be using architect Duncan Candler to design his Seal Harbor home. Candler had previously designed the neighboring Rockefeller home, as well as other note-worthy properties on the island.

John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s initial letter to Edsel congratulating him on the purchase of Edsel's Seal Harbor property. This letter lead to a life-long friendship that would be fueled by the spirit of philanthropy. THF255332

Christened with the name "Skylands" due to the unbroken views of the Maine horizon line that the property provided, Edsel's summer retreat was built between 1923 and 1925. In 1924, familiar with his new summer neighbor's philanthropic efforts and swayed by his past experiences, Edsel began donating yearly to the National Parks Association, known today as the National Parks Conservation Association. Created by industrialist Stephen Mather in 1919, the organization's mission was to protect the fledgling National Park Service, of which Mather was the director. For eight years Edsel would donate $500 annually to the National Parks Association, until the Depression years of 1932 and 1933 when other business and philanthropic demands restrained his monetary donations.

By the time Edsel's summer home was done in 1925, he and Rockefeller Jr. had become good friends and philanthropic partners. They shared a love for the arts, beautiful scenery, social justice, and civic responsibility. Although twenty years his senior, Rockefeller Jr. found Edsel's situation relatable. Both men were the only sons of immensely wealthy industrialist fathers and both had inherited the responsibility of their massive family fortunes. Each looked to use those fortunes to serve humanity and steer society towards a positive future. Rockefeller Jr. cherished the trait of modesty, a trait that he saw Edsel strongly demonstrate throughout his life. For that reason, Rockefeller Jr. held Edsel, "in the highest regard and esteem," describing him as, "so modest and so simple in his own living and in his association with his fellow men." Their summers spent together at Seal Harbor would undoubtedly include conversations about where they could best direct their philanthropic efforts.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1920s, 20th century, philanthropy, nature, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Ryan Jelso

Building Stories

What did you do this summer?

Earlier this summer, winners of our 2015-16 Building Stories student creative contest visited Henry Ford Museum to tour the exhibit With Liberty and Justice for All. They had photos taken on the Rosa Parks Bus, a fitting memento of their hard work writing poignant stories on Rosa Parks, one of our nation’s most impactful social innovators. Please enjoy the story written by our grand prize winner, Yani Li, here.

From left: Teacher Dr. Melissa Collins, Elementary First Prize Winner Isaiah Watkins, Middle School First Prize Winner Sarah Ellis, High School First Prize and Overall Winner Yani Li, and teacher Julie Ellis.

While the Building Stories contest has been cancelled moving forward so that The Henry Ford can reconsider its contest offerings, we encourage teachers to make use of the primary source “foundational materials” developed for Building Stories.

Catherine Tuczek is Curator of School & Public Learning at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford Museum, educational resources, by Catherine Tuczek, childhood

Innovative Inspiration

Maureen Foelkl is one of this year's Teacher Innovator Award winners. She shared her thoughts about her experience here at The Henry Ford; take a look here to see the rest of this year's winners.

From the moment I spied the entrance gates to The Henry Ford it reminded me of Disneyland as a child. The anticipation of the innovative educators’ experience was coming to fruition. The Henry Ford's Frederick Rubin and Phil Grumm greeted the innovative teacher group with a warm welcome and an introduction to our week.

Our days were thoughtfully planned. We began the experience interacting with modern day creators at Maker Faire Detroit. We were given the privilege of awarding blue ribbons to makers we believe captured the true innovative spirit. There were many creative ideas that it made it virtually impossible to isolate just two blue ribbon winners.

I was personally inspired by a 12-year-old maker that had taken used clothing and converted the rags into costumes that young adults stylishly wore. He started his own YouTube channel to show others how they could create their own woven masterpieces. The maker ribbon was his true inspiration to continue his own innovative creations. As an educator, this is what I value. An avenue to make students feel valued and successful.

The team from The Henry Ford is a phenomenal group of leaders that made the Teacher Innovator award meaningful. Cynthia Jones, Marc Greuther, Catherine Tuczek, Ben Seymour, Ryan Spencer, along with the most pleasant and helpful group of employees contributed to the positive experience at the museum. I now have nine additional educators I feel connected to for future inspirational teaching lessons.

I am creating an E-STEM unit of study for outdoor school. The Henry Ford's website will be invaluable as I begin to generate meaningful lessons. One of my lessons, on John Muir the expert navigator will expose students to the history of direction. Young navigators will learn to use a compass. I will have students take a brief overview from and research the history of the compass. For me, the lesson comes to life because I was fortunate to have a behind the scenes tour of the archives. Standing inches away from this compass allows me to tell a story behind the piece. I will share the knowledge to the next generation of learners in hope that they too will become explorers of their world.

The 2016 Teacher Innovator Award Winners: Far Back: Scott Weiler. From Left to right: Fabian Reid, Catherine Turso, George Hademenos, Jill Badalamenti, Cindy Lewis, Leon Tynes, Tracie Adams, Maureen Foelkl. (Unable to attend: Jessica Klass)

I highly encourage teachers to visit Henry Ford Museum and take time to introduce your students to the world of innovation via their website to inspire the creativity in teaching and learning.

Maureen Foelkl is a Teacher Innovator Award Winner at The Henry Ford and is a teacher at Chapman Hill Elementary in Salem, Oregon.

education, teachers and teaching, by Maureen Foelkl, Teacher Innovator Awards

Edsel Ford and the National Park Service

On August 25, 2016, the National Park Service celebrated its 100th birthday, a celebration that encouraged us to seek connections within our collections. This blog post is the first part of four that will trace Edsel Ford’s relationship to the national parks.

The landscapes preserved by the national parks are a source of inspiration. Not only do they document the natural history of America, but they are also integral in telling the story of humanity on the continent. They remain powerful educational tools, allowing citizens to reflect on their collective history and where they want society to go in the future. Responsible for protecting these historical, cultural, and scenic landscapes, the National Park Service owes much of its existence to the forward-thinking industrialists who supported the early environmental movements in America.

The National Park Service's birth can largely be attributed to the efforts of millionaire industrialist Stephen Mather. Using his wealth and political connections, Mather secured the job of Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior and went to Washington. Once there, he worked to lobby, fundraise, and promote an agency that could manage America's national parks and monuments. Finding success, Mather became the first director of the newly-formed National Park Service in 1916. At times, he even funded the agency's administration and bought land out of his own pocket. Mather was not the only affluent American to donate his time and wealth to the National Park Service.

The Rockefellers and Mellons, two of America's wealthiest families in the early 20th century, also became champions of the national parks. Specifically during this time period, the biggest player in national park philanthropic efforts was John D. Rockefeller Jr., the only son of oil magnate John D. Rockefeller. Among his many other National Park Service donations, Rockefeller Jr. was noteworthy for purchasing the land or donating the money that helped create the national parks of Acadia, Great Smoky Mountains, and Shenandoah, including the expansion of Grand Teton and Yosemite National Parks. Rockefeller dominated this philanthropic scene and ultimately influenced the only son of another wealthy industrialist to join him in his cause.

Edsel Ford, born to Henry and Clara Ford in 1893, was not born into wealth, but the success of Ford Motor Company in the early years of the 20th century led his father to become one of the richest men in America. This set Edsel down a path to inherit the responsibility of that wealth, a position in which he would thrive. Remarking that wealth "must be put to work helping people to help themselves," Edsel understood the elite position he was in and acted with grace throughout his life. Often described as altruistic, sensible, reserved and most importantly modest, Edsel would go on to channel his family's money into countless philanthropies including medical research, scientific exploration, the creative arts and America's national parks.

While this photograph was taken during the Fords' 1909 trip to Niagara Falls, they posed for the shot in a studio and were later edited into a photo of the falls. THF98007

At a young age, Edsel experienced some of the monuments and landscapes that make up our current national park system, creating memories that surely influenced him later in life. Family trips in 1907 and 1909 took Edsel to Niagara Falls, today a National Heritage Area in the park system. For the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909, Edsel accompanied his father by train to Denver and from there they took a scenic drive to Seattle where the exposition was being held. In 1914, he joined Thomas Edison, John Burroughs and his family as they spent time camping in the Florida Everglades. He also had the opportunity to visit the Grand Canyon at least four times in his life, with his first glimpse of the gorge occurring during a family trip to Southern California in 1906.

Visiting the Grand Canyon in 1906, Edsel sits here with his mother, Clara Ford, and Clara's mother, Martha Bryant. The canyon can be faintly seen in the background. THF255176

Edsel recorded a subsequent trip to the canyon in his diary during January of 1911. He wrote that he spent time hiking, visiting the Hopi House to watch Native American dances, and photographing the canyon. Photography would become one of many artistic hobbies Edsel pursued over the course of his life. Undoubtedly the beautiful vistas of the Grand Canyon provided a spark of creativity for the burgeoning young artist. The national parks and monuments had inspired creative sparks previously, allowing Edsel to illustrate this picture of the Washington Monument in 1909. These forays into the arts helped Edsel later become the creative force that took Ford Motor Company beyond the Model T and successfully into the industry of automobile design.

Edsel recorded his second Grand Canyon trip in his diary. Interestingly, Edsel also mentions he has heard of the deaths of Arch Hoxsey and John B. Moisant, two record-breaking pilots who died while performing separate air stunts on New Year's Eve of 1910. THF255172

Before Edsel made his dreams of car design a reality, Ford Motor Company had played a role in helping to improve accessibility to the landscapes of the national parks by making the automobile, specifically the Model T, affordable to the masses. In 1915, at age 21, Edsel took off in a Model T on a cross-country road trip with six of his friends. Departing from Detroit and heading to San Francisco, the trip allowed Edsel to again witness the scenic changes in the countryside as he traveled across the continent, something he had experienced on numerous family trips before. This time though, he was in charge of the places he explored. Making various stops during his expedition, Edsel visited the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, the desert of New Mexico and the Grand Canyon for a third time.

Edsel Ford and friends hike down Bright Angel Trail while visiting the Grand Canyon during their 1915 cross-country road trip. THF243915

The Grand Canyon must have left quite the impression on Edsel because, in November of 1916, he brought his new wife Eleanor Clay there on the way to their honeymoon in Hawaii. He wrote his parents from the El Tovar Hotel saying "We are surely having a great time. Walking and breathing this great air." They had spent the previous day visiting Grandview Point, a spot that continues to provide park goers with breathtaking views of the canyon. Edsel's new wife Eleanor would play an important role in his future national park endeavors. She exposed him to the rugged shores and natural beauty of the Maine coast -- a place where Edsel would cross paths with John D. Rockefeller Jr., establishing a friendship that would last a lifetime.

Operated by the Fred Harvey Company, which owned a chain of railroad restaurants and hotels, El Tovar Hotel was opened in 1905 through a partnership with the Santa Fe Railway. THF255180

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1910s, 1900s, 20th century, travel, philanthropy, nature, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Ryan Jelso

Electrical Connection

We continue to work on our IMLS-grant funded project to conserve, catalog, photograph, rehouse, and digitize 900 artifacts from our electrical distribution equipment collection. A number of the meters and other artifacts we’ve turned up during that project were created by the Fort Wayne Electric Works (also known as the Fort Wayne Electric Corporation), an Indiana company that manufactured electrical equipment and other items in the late 19th century. To accompany the artifacts, we’ve just digitized photographs from our Fort Wayne Electric Works archival collection, which show various parts of the factory around 1894—including this shot of the testing and calibrating laboratory.

Connect our Fort Wayne artifacts with our Fort Wayne photographs for yourself by visiting our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- 1899 Locomobile Runabout: Freedom on Wheels

- Maudslay Production Lathe, circa 1800

- Gas-Steam Engine, 1916, Used to Generate Electricity at Highland Park Plant

- Surprising Stories from IMLS Discoveries

Indiana, 19th century, power, photographs, manufacturing, IMLS grant, electricity, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, archives

A Wardrobe Workshop

Visit Greenfield Village and you can’t help but notice the clothing. From the colonial-era linen garments worn by the Daggett Farmhouse staff as they go about their daily chores to the 1920s flapper-style dresses donned by the village singers, or even the protective clothing worn by the pottery shop staff in the Liberty Craftworks district — all outfits in Greenfield Village are designed to add to the guest experience. In many cases, these tangible elements help accurately showcase the time period being interpreted.

“Clothing is such a big part of history,” said Tracy Donohue, general manager of The Henry Ford’s Clothing Studio, which creates most of The Henry Ford’s reproduction apparel and textiles for daily programs as well as seasonal events. “It’s a huge part of how we live even today. The period clothing we provide helps bring to life the stories we tell in the village and enhances the experience for our visitors.”

The Clothing Studio is tucked away on the second floor of Lovett Hall. It provides clothing for nearly 800 people a year in accurate period garments, costumes and uniforms, and covers more than 250 years of fashion — from 1760 to the present day — making the studio one of the premier museum period clothing and costume shops in the country.

The scope and flow of work in the studio is immense, from outfitting staff and presenters for the everyday to clothing hundreds for extra seasonal programs such as Historic Base Ball, Hallowe’en and Holiday Nights. Work on the April opening of Greenfield Village, for example, begins before the Holiday Nights program ends in December, with the sewing of hundreds of stock garments and accessories in preparation for hundreds of fitting sessions for new and current employees.

“When it comes to historic clothing, our goal is to create garments accurate to the period — what our research indicates people in that time and place wore,” said Donohue. “For our group, planning for Hallowe’en is an especially fun challenge. We have more creative license with costumes for this event than we typically do with our daily period clothing.”

For Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village, the studio staff researches new characters and can work on the design and development for more elaborate wearables for months. In addition to new costume creation, each year existing outfits are refreshed and/or reinvented. Last year, for example, the studio added the Queen of Hearts, Opera Clown and a number of other new characters to the Hallowe’en catalog. Plus, they freshened the look of the beloved dancing skeletons and the popular pirates.

Historic clothing, period photographs, prints, trade catalogs and magazines from the Archive of American Innovation provide a wealth of on-site resources to explore the styles, clothing construction and fabrics worn by people decades or centuries ago. Each year, Jeanine Head Miller, curator of domestic life, and Fran Faile, textile conservator, host the studio’s talented staff for a field trip to the collections storage area for an up-close look at original clothing from a variety of time periods.

“Getting the details right really matters,” Miller said. “Clothing is part of the powerful immersive experience we provide in Greenfield Village. Having people in accurate period clothing in the homes and the buildings helps our visitors understand and immerse themselves in the past, and think about how it connects to their own lives today.”

Did You Know?

The Clothing Studio has a comprehensive computerized inventory management system, which tracks close to 50,000 items.

During each night of Hallowe’en, Clothing Studio staff are on call, checking on costumed presenters throughout the evening to ensure they look their best.

What They're Wearing Under There

At Greenfield Village, costume accuracy goes well beyond what’s on the surface. Depending on the time period they’re interpreting, women may also wear chemises, corsets and stays.

“Our presenters have a lot of pride in wearing the clothing and wearing it correctly,” said Donohue.

While the undergarments function in the service of historic accuracy, corsets also provide back support and chemises help absorb sweat. Natural fibers in cotton fabrics breathe, so they’re often cooler to wear than modern-day synthetic fabrics. And when the weather runs to extreme cold conditions, layers of period-appropriate outerwear help keep village staff warm. The staff at the Clothing Studio also sometimes turns to a few of today’s tricks to keep staff comfortable. Wind- and water-resistant performance fabrications are often built into Hallowe’en costumes to offer a level of protection from outdoor elements.

“It can be 100 degrees in the summer and 10 degrees on a cold Holiday Night,” Donohue said. “Our staff is out in the elements, and they still have to look amazing. We care about the look and overall visual appearance of the outfit, of course, but we also care about the person wearing it.”

From The Henry Ford Magazine. This story originally ran in the June-December 2016 issue.

Hallowe'en in Greenfield Village, events, Greenfield Village, making, costumes, fashion, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, The Henry Ford Magazine

From the Museum Floor to Our Collections

If you’ve visited Henry Ford Museum, this bench might look familiar to you. In fact, you might have sat on this bench or one of about two dozen exactly like it during your visit. However, this one is now off-limits to sitting, as it has found a place in our collections. The bench was commissioned in 1939 by Edsel Ford for use at what was then known as the Edison Institute, now The Henry Ford. It was designed by Walter Dorwin Teague, a leader in early industrial design, at the height of his career. We’ve just digitized the bench—visit our Digital Collections to see other artifacts from our collections related to Walter Dorwin Teague, including correspondence and blueprints associated with the bench.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1930s, Henry Ford Museum, furnishings, digital collections, design, by Ellice Engdahl

GT40s Land on Pebble Beach for 2016

Seventeen Ford GT cars pose for a group portrait on Pebble Beach’s 18th fairway. P/1046, which finished first at Le Mans 50 years ago, leads the pack.

It’s a big year for Ford Motor Company’s iconic GT40 race car. Fifty years ago, New Zealander drivers Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren realized Henry Ford II’s ambitious goal to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans endurance race, while two other GT40s took second and third place. This year, in a bold move, Ford returned to Le Mans with the all-new GT and, in fairy tale fashion, won its class 50 years to the day after the Amon/McLaren victory. Meanwhile, demand for the forthcoming street version of the new GT is so great that Ford just announced it’ll be adding two more production years to the supercar’s limited run. What better time, then, to celebrate the GT40 at the prestigious Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance? Three cars representing four years of consecutive Le Mans victories: Our Mark IV J-5 (1967), P/1075 (1968-69), and P/1046 (1966).

Three cars representing four years of consecutive Le Mans victories: Our Mark IV J-5 (1967), P/1075 (1968-69), and P/1046 (1966).

Private owners and museums around the world answered the call from Pebble Beach organizers. On August 21, they filled the 18th fairway with what might have been the most impressive collection of Ford GT cars ever assembled outside of the Circuit de la Sarthe. No fewer than 17 GT40s and GT40 variants made the trip to California, and it seemed that every important car was there. There was chassis P/1046, the GT40 Mark II that Amon and McLaren drove to victory in 1966. Freshly – and brilliantly – restored to its race day appearance, the car took “Best in Class” honors from the Pebble Beach judges. Alongside it were 1966’s second and third place cars driven by Ken Miles and Denny Hulme, and Ronnie Bucknum and Dick Hutcherson, respectively.

GT40 P/1015 won the 1966 24 Hours of Daytona with Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby. Four months later, it finished second at Le Mans with Miles and Denny Hulme.

GT40 P/1015 won the 1966 24 Hours of Daytona with Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby. Four months later, it finished second at Le Mans with Miles and Denny Hulme.

Le Mans winners from other years were present, too. Our Mark IV chassis J-5, of course, won in 1967 with Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt sharing the driver duties. Then there was chassis P/1075, the GT40 Mark I that won Le Mans twice in a row, with drivers Lucien Bianchi and Pedro Rodriguez in 1968, and with Jacky Ickx and Jackie Oliver in 1969. Ford Motor Company itself pulled out of Le Mans after 1967, but privateer John Wyer did the GT40 proud with those back-to-back victories.

From Switzerland came this replica of GT/101, the very first GT40, which turned heads at the 1964 New York Auto Show.

From Switzerland came this replica of GT/101, the very first GT40, which turned heads at the 1964 New York Auto Show.

Le Mans wasn’t the only race represented at Pebble Beach. Mark IV chassis J-4, which won the 1967 12 Hours of Sebring with Bruce McLaren and Mario Andretti at the wheel, was there on the fairway. So was GT40 P/1074, the Mirage variant which took first place at Belgium’s Spa 1000-kilometer race in 1968 with Jacky Ickx and Dick Thompson. The collection was rounded out with a replica of GT/101, the first-ever GT40, and the prototype 1967 GT40 Mark III that modified the track racer into a more civilized street machine.

The rare GT40 Mark III. Just seven of these refined road cars were ever built.

The rare GT40 Mark III. Just seven of these refined road cars were ever built.

To put the icing on the cake, the GT40 also featured on this year’s official concours poster. The painting, by noted automotive artist Ken Eberts, features the 1966 trio of 1-2-3 finish cars posed in front of the Lodge at Pebble Beach. Behind the cars stand Carroll Shelby, Henry Ford II and Edsel Ford II. (The younger Mr. Ford not only witnessed the 1966 victory with his father, he was also at Le Mans this year for the 2016 win.)

This year’s Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for fans of the GT40. We were honored to participate with the Mark IV, and we look forward to watching the next chapter of GT history unfold with Ford Performance’s new generation of cars.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

events, racing, Pebble Beach, Mark IV, Ford Motor Company, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson