Posts Tagged by debra a. reid

A Closer Look: The Champion Egg Case Maker

After the Civil War, urban populations swelled. Until this time, farm families had kept flocks of chickens and gathered eggs for their own consumption, but with increased demand for eggs in growing cities, egg farming grew into a specialized industry. Some families expanded egg production at existing farms, and other entrepreneurs established large-scale egg farms near cities and on railroad lines. Networks developed for shipping eggs from farms to buyers – whether wholesalers, retailers, or individuals operating eating establishments.

While farmers who sold eggs directly to customers carried their products to market in different ways, sellers who shipped eggs to buyers standardized their containers to ensure a consistent product. The standard egg case became an essential and enduring part of the egg industry.

Egg producers initially used different sizes and types of containers to pack eggs for market. As the egg industry developed, standardized cases that held thirty dozen (360) eggs – like this version first patented by J.L. and G.W. Stevens in 1867 – became the norm. THF277733

Egg distributors settled on a lightweight wooden box to hold 30 dozen (360) eggs. The standard case had two compartments that held a total of twelve “flats” – pressed paper trays that held 30 eggs each and provided padding between layers. Retailers who purchased wholesale cases of eggs typically repackaged them for sale by the dozen (though customers interested in larger quantities could – and still can – buy flats of 30 eggs).

The standard egg case held 12 of these pressed paper trays, or “flats,” which held 30 eggs each. THF169534

Some egg shippers purchased premade egg cases from dedicated manufacturers. Others made their own. Enter James K. Ashley, who invented a machine to help people build egg cases to standard specifications. Ashley, a Civil War veteran, first patented his egg case maker in 1896 and received additional patents for improvements to the machine in 1902 and 1925.

James K. Ashley’s patented Champion Egg Case Maker expedited the assembly of standard egg cases.

Ashley’s machine, which he marketed as the Champion Egg Case Maker, featured three vises, which held two of the sides and the interior divider of the egg case steady. Using a treadle, the operator could rotate them, making it easy to nail together the remaining sides, bottom, and top to complete a standard egg case, ready to be stenciled with the seller’s name and filled with flats of eggs for shipment.

Ashley’s first customer was William Frederick Priebe, who, along with his brother-in-law Fred Simater, operated one of the country’s largest poultry and egg shipping businesses. As James Ashley continued to manufacture his egg case machines (first in Illinois, then in Kentucky) in the early twentieth century, William Priebe found rising success as the big business of egg shipping grew ever bigger.

One of James K. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Makers, now in the collections of The Henry Ford. THF169525

James Ashley received some acclaim for his invention. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Maker earned a medal (and, reputedly, the high praise of judges) at the St. Louis World's Exposition in 1904. And in 1908, The Egg Reporter – an egg trade publication that Ashley advertised in for more than a decade – described him as “the pioneer in the egg case machine business” (“Pioneer in His Line,” The Egg Reporter, Vol. 14, No. 6, p 77).

While the machine in the The Henry Ford’s collection no longer manufactures egg cases, it still has purpose – as a keeper of personal stories and a reminder of the complex ways agricultural systems respond to changes in where we live and what we eat.

Additional Readings:

- Henry’s Assembly Line: Make, Build, Engineer

- Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882

- The Wool Carding Machine

farming equipment, manufacturing, food, farms and farming, farm animals, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture

Freedmen’s Bureau: Exercising Citizenship

President Abraham Lincoln signed The Freedmen’s Bureau Act on March 3, 1865. That Act created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands as part of the War Department. It provided one-year of funding, and made Bureau officials responsible for providing food, clothing, fuel, and temporary shelter to destitute and suffering refugees behind Union lines and to freedmen, their wives, and children in areas of insurrection (in other words, within the Confederate States). The legislation specified the Bureau’s administrative structure and salaries of appointees. It also directed the Bureau to put abandoned or confiscated land back into production by allotting not more than 40 acres to each loyal refugee or freedman for their use for not more than three years, at a rent equal to six percent of its 1860 assessed value, and with an option to purchase. The Bureau assumed additional duties in response to freed people’s goals, namely building schools, negotiating labor contracts, and mediating conflicts.

Lincoln supported the Bureau because it fit his plan to hasten peace and reconstruct the nation, but after Lincoln’s assassination, support wavered. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1866 provided two years of funding. During 1868, increasing violence and for a return to state authority undermined the goals of freed people and the Bureau that worked for them. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1868 authorized only the educational department and veteran services to continue. All other operations ceased effective January 1, 1869.

Collections at The Henry Ford help document public perceptions of the Freedmen’s Bureau as well as actions taken by Bureau advocates. Letters, labor contracts, and newspapers indicate the contests that played out as the Bureau tried to introduce a new model of economic and social justice and civil rights into places where absolute inequality based on human enslavement previously existed. The Bureau did not win the post-war battle for freedmen’s rights. Congress did not reauthorize the Bureau, and it ceased operations in mid-1872.

The Beginning

Bureau appointees went to work at the end of the Civil War in 1865 to serve the interests of four-million newly freed people intent on exercising some self-evident truths itemized in the Declaration of Independence:

That all men are created equal

That they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights

That among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

Engraved Copy of the 1776 Declaration of Independence, Commissioned by John Quincy Adams, Printed 1823.

With freedom came responsibility to sustain the system of government that “We the People” constituted in 1787, and that the Union victory over secession reaffirmed in 1865. Little agreement over the best course of action existed. The national government extended the blessings of liberty by abolishing slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865. It established the Freedmen’s Bureau which advocated for the general welfare of newly freed people.

Book, "The Constitutions of the United States, According to the Latest Amendments," 1800. THF 155864

Expanding liberty and justice came at a price, both economic and human. Every time freed people exercised new-found liberty and justice, others resisted, perceiving the expansion of another person’s liberty as a threat to their own. The Bureau operated between these factions, as an 1868 illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicted. The newspaper claimed that the Bureau was “the conscience and common-sense of the country stepping between the hostile parties, and saying to them, with irresistible authority, ‘Peace!’.”

“The Freedmen’s Bureau,” Harper’s Weekly, July 25, 1868, pg. 473. 2018.0.4.38. THF 290299

Economics

Building a new southern economy went hand in hand with expanding social justice and civil rights. Concerned citizens and commanding officers knew that African Americans serving in the U.S. Colored Troops had money to save. They started private banks to meet the need. The U.S. Congress responded with "An Act to Incorporate the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company." Lincoln signed the legislation on March 3, 1865, the same day he signed “An Act to Establish a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees.” Agents of the public Freedmen’s Bureau worked closely with staff at the private Freedman’s Bank because freed people needed the economic stability the bank theoretically provided.

At least 400,000 people, one tenth of the freed population, had an association with a person who opened a savings account in the 37 branches of the savings bank that operated between 1865 and 1874. This included Amos H. Morrell, whose daughter’s heirs resided in the Mattox House. Soldiers listed on the Muster Roll of Company E, 46th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry, also appear in records of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. Charles Maho, a private in Company E, 46th USCT, opened an account on August 13, 1868. He worked in a tobacco factory at the time. His brother in arms, James Parvison/Parkinson, also a private, opened an account on December 1, 1869 and his estranged wife, Julia Parkerson opened an account on May 14, 1870.

Mattox Family Home, circa 1880

Freedmen’s Bureau officials encouraged deposits into the Freedmen’s Bank. This helped freed people become accustomed to saving the coins they earned, literally the coins that symbolized their independence as wage earners. Sadly, Bureau officials often assured account holders that their investments were safe. The deposits were not protected by the national government, however, and when the bank closed in 1874 it left depositors penniless and petitioning for return of their investments.

One-cent piece. Minted in 1868. THF 173625 (front) and THF 173624 (back)

Three-cent piece (made of nickel). Minted in 1865. THF 173623 (front) and THF 173622 (back).

The U.S. Congress authorized the Bureau to collect and pay out money due soldiers, sailors, and marines, or their heirs. Osco Ricio, a private in Company E, 46th U.S. Colored Infantry, who enlisted for three years in 1864, but was mustered out in 1866, made use of this service in his effort to secure $187 due him.

Freedmen’s Bureau staff mediated between freed people and employers, negotiating contracts that specified work required, money earned, and protection afforded if employers reneged on the agreement. A blank form, printed in Virginia in 1865, included language common to an indenture – that the employer would provide “a sufficiency of sound, wholesome food and comfortable lodging, to treat him humanely, and to pay him the sum of _____ Dollars, in equal monthly instalments of ____ Dollars, good and lawful money in Virginia.”

Freedman's Work Agreement Form, Virginia, 1865 Object ID 2001.48.18. THF 290704

Another pre-printed form reinforced terms of enslavement, that the work should be performed “in the manner customary on a plantation,” even as it confirmed the role of Freedmen’s Bureau agents as adjudicator. Freedman Henry Mathew, and landowner R. J. Hart, in Schley County, Georgia, completed this contract which legally bound Hart to furnish Mathew “quarters, food, 1 mule, and 35 acres of land” and to “give. . . one-third of what he [Mathew] makes.” This type of arrangement became the standard wage-labor contract between landowners and sharecroppers, paid for their labor with a share of the crops grown on the land.

Freedman's Contract for a Mule and Land, Dated January 1, 1868. THF 8564

Many criticized sharecropping as another form of unfree labor rather than as a fair labor contract. Close reading confirms the inequity which often took the form of additional work that laborers performed but that benefitted owners. In the case of Hart and Mathew, Mathew had to repair Hart’s fencing which meant that Mathew realized only one-third return on his labor investment in the form of a crop perhaps more plentiful because of the fence. Hart claimed the other two-thirds of the crop plus all of the increased value of fencing.

Education

Freed people wanted access to education to learn what they needed to make decisions as informed and productive citizens.

Harper’s Weekly, a New York magazine, often featured freedmen’s schools that resulted from a cooperative agreement between the Freedmen’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association (AMA), based in New York. A reporter informed readers on June 23, 1866 that “the prejudice of the Southern people against the education of the ‘negroes’ is almost universal.” Regardless, freed people needed schools, teachers, and institutes to train teachers. The Freedmen’s Bureau and its partners committed their resources in support of this cause.

Commentary accompanying an illustration of the “Primary School for Freedmen” indicated that the school building was dilapidated and owned by someone who wanted rid of the school, but the students were eager to learn and as capable as other students of their age in New York public schools.

“Primary School for Freedmen, in Charge of Mrs. Green, at Vicksburg, Mississippi, Harper’s Weekly, June 23, 1866, pg. 392 (bottom), story on pg. 398. THF 290712

School curriculum often emphasized agricultural and technical training. The “Freedmen’s Farm School,” located near Washington, D.C., also known as the National Farm-School, taught orphans and children of U.S. Colored Troops reading, writing and arithmetic, standard primary school subjects. Students also cultivated a one-hundred-acre farm. The combination compared to a new effort launched with the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 to create a system of colleges, federally funded but operated at the state level to train students in agricultural and mechanical subjects. The combination could help students realize the American dream – owning and operating their own farm. While the system of land-grant colleges grew steadily during Reconstruction, the freedmen’s schools faced opposition locally and at the state level. Increasingly educators turned to philanthropists to fund education for freed people.

Struggles

The individuals appointed to direct the Freedmen’s Bureau often had military experience. Brigadier General Oliver Otis Howard served in the Union Army and gained a reputation as a committed abolitionist if not a strong officer. President Andrew Johnson appointed him the first Commission of the Bureau, and he remained in that position until the Bureau closed in 1872. Two years later Howard lamented lost opportunities: “I believe there are many battles yet to be fought in the interest of human rights”….“There are wrongs that must be righted. Noble deeds that must be done.”

Many shared Howard’s frustrations with the lack of public support for freed people’s goals. They also resented the obstructions that thwarted those goals. Newspaper reporting, such as the regular features in Harper’s Weekly, emphasized the good work of the Freedmen’s Bureau, but reporting also threatened projects aimed at sustaining the momentum.

Henry Wilson, a Republican Senator from Massachusetts, sought equality for African Americans. He took a correspondent to the Republican, a newspaper in Springfield, Massachusetts, to task for publishing misinformation about the extent of congressional fundraising for political purposes, and for downplaying the need for sharing facts with voters, especially the 700,000 Southerners newly enfranchised after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. Wilson explained that hundreds of thousands of documents, possible through the congressional fundraising, could educate voters about issues and prepare them for the upcoming election. Without donations from U.S. congressmen, Wilson believed such efforts would fail.

The End

The short life but complicated legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau leaves much to ponder. The Bureau, as a part of the War Department, and then an independent national agency, mediated local conflict and supported local education. This occurred at an exceptional time as the Union began rebuilding the nation in 1865. Then, the Republican party interpreted the U.S. Constitution as a mandate for the national government to protect civil rights broadly defined. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, incorporated newly freed people as full citizens. Most believed that the Bureau had no more work to do, and Congress did not reauthorize it after July 1872. Those who favored the Bureau lamented its abrupt end and believed that much remained to be done to open the American experiment in equal rights to all.

Debra Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Sources and Further Reading

- African American Records: Freedmen’s Bureau, National Archives and Records Administration

- Carpenter, John A. Sword and Olive Branch: Oliver Otis Howard (1999)

- Cimbala, Paul A. The Freedmen's Bureau: Reconstructing the American South after the Civil War (2005)

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988).

- Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (1979).

- McFeely, William S. Yankee Stepfather: General O.O. Howard and the Freedmen (1994).

- Osthaus, Carl R. Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedman's Savings Bank (1976)

- Oubre, Claude F. Forty Acres and a Mule: The Freedmen’s Bureau and Black Land Ownership (2012).

- Washington, Reginald. “The Freedman's Savings and Trust Company and African American Genealogical Research,” Federal Records and African American History (Summer 1997, Vol. 29, No. 2)

1870s, 1860s, 19th century, Civil War, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Small Objects with Big Stories

Timber Scribe: A small tool, a timber scribe, helps inform us about resourcefulness and entrepreneurship.

Timber Scribe: A small tool, a timber scribe, helps inform us about resourcefulness and entrepreneurship.

The Oxford English Dictionary confirms use of the term “timber scribe” by 1858 as “a metal tool or pointed instrument for marking logs and casks.” Another tool, a “race-knife” (also spelled rase knife) performed a similar function, “marking timber,” but the tools differed in detail.

The race knife had a “bent-over, sharp lip for scribing,” according to Edward H. Knight who compiled the Practical Dictionary of Mechanics, a nearly 8,000-page behemoth containing 20,000 subjects and around 6,000 illustrations, published in 1877. The timber scribe included two pieces with bent-over sharp lips as well as a point. The combination made it possible to scribe Arabic numbers, not just gouge Roman numerals, into logs and casks and timber, as shown below.

This tool has a wooden handle, a brass band that helped stabilize the wooden end where the forged steel was inset into the wooden handle, and the steel point with a cutter/gouge and separate “bent-over sharp lip”/gouge Dimensions: Length 7.25 inches; Height 2 inches; Width 1 inch. Object ID: 2017.0.34.625

This tool has a wooden handle, a brass band that helped stabilize the wooden end where the forged steel was inset into the wooden handle, and the steel point with a cutter/gouge and separate “bent-over sharp lip”/gouge Dimensions: Length 7.25 inches; Height 2 inches; Width 1 inch. Object ID: 2017.0.34.625

Simply stated, a timber scribe included the components of the race knife. Lumbermen, shipbuilders, house wrights and carpenters, coopers, and surveyors, all used the timber scribe to make uniform marks on wood, but they could also use the elongated cutter/gouge to make free-hand marks. They used the race knife to make free-hand marks.

Appearances mattered. The timber scribe at The Henry Ford combines three natural materials – iron/steel, brass, and wood – all processed and refined in ways that make the tool pleasing to the eye, and useful to the woodsman or craftsman. The maker chamfered the edges of the wooden handle and scribed the brass collar.

An 1897 catalog from a Detroit hardware distributor, the Charles A. Strelinger Company, advertised a “rase knife or timber scribe.” The company sold three variations: a large size (though the catalog provided no dimensions), a small size, and a pocket rase knife. The large timber scribe included all three steel components (point with cutter gouge and “bent-over sharp lip” gouge) while the small version included just two of the three (point and gouge). The pocket rase knife likely consisted of just the gouge, which folded into the wooden handle of the knife, as seen below.

Rase Knife or Timber Scribe. Detail from Wood Workers’ Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery, and Similar Goods used by Carpenters, Builders, Cabinet Makers, Pattern Makers, Millwrights, Carvers, Ship Carpenters, Inventors, Draughtsmen, and [also] all “Wood Butchers” not included in Foregoing Classification and in Manufactories, Mills, Mines, etc., etc. Detroit Michigan: Charles A. Strelinger & Company, 1897, page 662. In the collection of the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan.

The tool in The Henry Ford's collection compares to the large timber scribe illustrated in Strelinger & Company’s 1897 catalog. The tool’s dimensions (7.25 inches long) inform us about the size of a “large” scribe.

Charles A. Strelinger was born in Detroit in 1856. The 1897 catalog Charles A. Strelinger Company indicated that the company had 30 years of experience in manufacturing and selling tools, supplies and machinery. Strelinger’s approach to advertising his wares through print media indicated how little change occurred in the tool business. The front page of the catalog had a blank space to write in the date, and, as he explained in “This Year’s Catalogue”: “our 1895 catalogue is also our 1896-’97-’98, and perhaps, 1899 catalogue. If we were selling Seeds and Plants, Ladies’ Hats and Bonnets, Patent Medicines, etc., we would, doubtless, find it necessary to issue a new catalogue every year, but our goods are of a stable nature, changes are comparatively few, and we are not warranted to going to the expense of printing a new book every year.”

The timber scribe and the Strelinger Company catalog confirm the need for specialized tools that serve many in various wood-working trades. The Company was resourceful in advertising, because the hand tools in woodworking were remarkably standardized by the late-nineteenth century and remained useful despite industrialization.

Debra A. Reid is Curator, Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford received funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) in 2017 to support a three-year project to conserve, rehouse, and digitize thousands of objects. This is work, supported through IMLS’s Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, will continue over three years as The Henry Ford consolidates offsite collections into a new location on campus. The work “will improve the physical condition of the project artifacts through conservation treatment, rehousing, and removal to improved environments.” Finally, IMLS funding “will facilitate collections access through the creation of catalog records and digital images, available to all via THF's Digital Collections.”

A series of blogs shares the stories of small items that tell big stories of innovation, ingenuity, and resourcefulness, and that relate to other collections and interpretation at The Henry Ford.

Solving a Collections Mystery with IMLS

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

As the grant narrative explains, the IMLS funding supports a “critical element in a major institutional project: the consolidation of The Henry Ford's off site collections into a new location on campus.” The work “will improve the physical condition of the project artifacts through conservation treatment, rehousing, and removal to improved environments.” Finally, IMLS funding “will facilitate collections access through the creation of catalog records and digital images, available to all via The Henry Ford's digital collections.”

Occasionally Susan comes upon an artifact that needs additional explanation to accurately catalog it, such as this one. Here's what we knew upon examination:

- It's 16" long, 7" wide

- Has a smooth wooden handle

- Is bent and welded iron

- There's a ringed brass flange positioned to reduce wear where the metal is imbedded into the organic material.

The questions we then ask: What is this instrument? What purpose does it serve?

We turned to our horse experts with the Ford Barn team in Greenfield Village to help us understand its use.

A steady diet of oats, grass, and hay wears a horse’s teeth down as they age. Persistent grinding of food can leave sharp burrs or edges on the outside of their molars. Untreated, this causes pain when the horse chews, and they lose weight.

Farmers and veterinarians used this instrument (called a “gag” or speculum) to hold a horse’s mouth open as they floated the horse’s teeth to balance their bite. Floating helps a horse maintain a healthy bite in their senior years.

A person (farmer or veterinarian) would insert the “gag” into the horse’s mouth, holding it by the handle. Then, the farmer/veterinarian would pull downward on the handle which “encouraged” the horse’s mouth to open. The oval area provided a window through which to place the float (a rasp used to file down the sharp edges).

The device proved useful when treating younger horses with other dental issues, too. Today caring for aging horses still requires floating and balancing their teeth. Caregivers still use a speculum to hold the horse’s mouth open, and to keep their head steady during floating and balancing, but the instruments today have padding to reduce stress on the horse’s jaw during the procedure.

Thanks to the IMLS for providing the invaluable funding to help make this exploration of animal care possible.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Jim Slining is Curator of Museum Collections at Tillers International.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, IMLS grant, healthcare, farm animals, by Jim Slining, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Winter Nature Studies

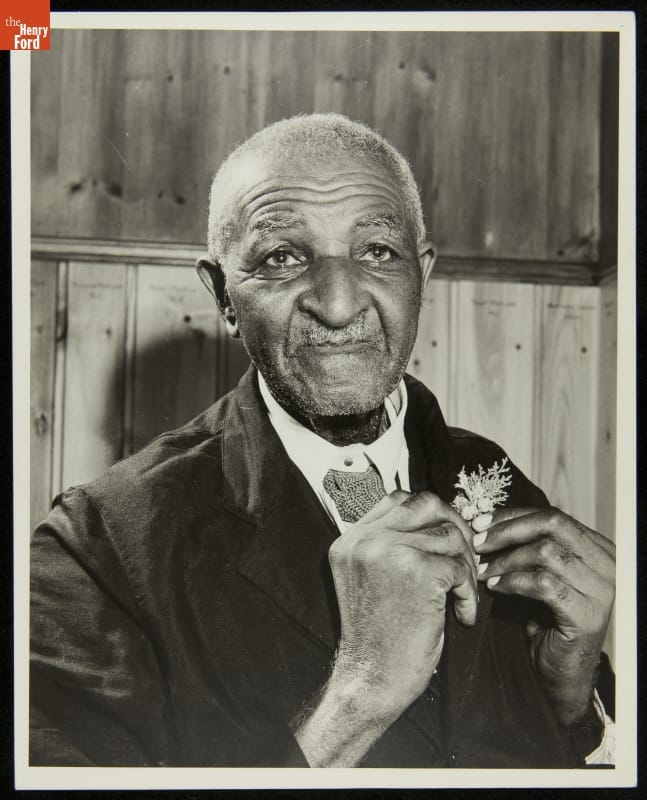

THF213753 / George Washington Carver at Dedication of George Washington Carver Cabin, Greenfield Village, 1942.

On this day in 1946, George Washington Carver Recognition Day was designated by a joint act of the U.S. Congress and proclaimed by President Harry S. Truman. Carver died just three years earlier on this day in 1943.

Immediately, public officials and the news media began to celebrate his life and create lasting reminders of his work in education, agricultural science, and art. Carver, mindful of his own legacy, had already established the Carver Foundation during the 15th annual Negro History Week, on February 14, 1940, to carry on his research at Tuskegee. It seems fitting to pay respects to Carver on his death day by taking a closer look at the floral beautis that Carver so loved, and that we see around us, even during winter.

Carver recalled that, “day after day I spent in the woods alone in order to collect my floral beautis” [Kremer, ed., pg. 20]. He believed that studying nature encouraged investigation and stimulated originality. Experimentation with plants “rounded out” originality, freedom of thought and action.

THF213747 / George Washington Carver Holding Queen Anne's Lace Flowers, Greenfield Village, 1942.

Carver wanted children to learn how to study nature at an early age. He explained that it is “entertaining and instructive, and is the only true method that leads up to a clear understanding of the great natural principles which surround every branch of business in which we may engage” (Progressive Nature Studies, 1897, pg. 4). He encouraged teachers to provide each student a slip of plain white or manila paper so they could make sketches. Neatness mattered. As Carver explained, the grading scale “only applies to neatness, as some will naturally draw better than others.”

Neatness equated to accuracy, and with accuracy came knowledge. Farm families could vary their diet by identifying additional plants they could eat, and identify challenges that plants faced so they could correct them and grow more for market.

Carver understood how the landscape changed between the seasons, and exploring during winter was just as important as exploring during summer. Thus, it is appropriate to apply Carver’s directions about observing nature to the winter landscape around us, and to draw the winter botanicals that we see, based on directions excerpted from Carver’s Progressive Nature Studies (1897). (Items in parentheses added to prompt winter-time nature study - DAR and DE, 3 Jan 2018.)

- Leaves – Are they all alike? What plants retain their leaves in winter? Draw as many different shaped leaves as you can.

- Stems – Are stems all round? Draw the shapes of as many different stems as you can find. Of what use are stems? Do any have commercial value?

- Flowers (greenhouses/florists) – Of what value to the plant are the flowers?

- Trees – Note the different shapes of several different trees. How do they differ? (Branching? Bark?) Which trees do you consider have the greatest value?

- Shrubs – What is the difference between a shrub and a tree?

- Fruit (winter berries) – What is fruit? Are they all of value?

Carver worked in greenhouses and encouraged others to use greenhouses and hot beds to start vegetables earlier in the planting system. The sooner farm families had fresh vegetables, the more quickly they could reduce the amount they had to purchase from grocery stores, and the healthier the farm families would be.

THF213726 / George Washington Carver in a Greenhouse, 1939.

In 1910, Carver included directions for work with nature studies and children’s gardens over twelve months. Selections from “January” suitable for nearly all southern states” included:

- Begin in this month for spring gardening by breaking the ground very deeply and thoroughly

- Clear off and destroy trash (plant debris) that might be a hiding place for noxious insects.

- Cabbages can be put in hot beds, cold frames, or well-protected places.

- Grape vines, fruit trees, hedges and ornamental trees should receive attention (pruning, fertilizing)

- Both root and top grafting of trees should be done.

THF213314 / Pamphlet, "Nature Study and Children's Gardens," by George Washington Carver, circa 1910.

Carver illustrated his own publications, basing his botanical drawings on what he observed in his field work. He conveyed details that his readers needed to know, be they school children tending their gardens, or farm families trying to raise better crops.

THF213278 / Pamphlet, "Some Possibilities of the Cow Pea in Macon County, Alabama," by George Washington Carver, 1910 / page 12.

Edible wild botanicals, also known as weeds, appeared in late winter. Carver encouraged everyone from his students at Tuskegee to Henry Ford to consumer more wild greens year round, but especially in late winter when greens became a welcome respite from root crops and preserved meats which dominated winter fare. His pamphlet, Nature’s Garden for Victory and Peace, prepared during World War II, featured numerous drawings of edible wild botanicals, also called weeds. Americans could contribute to the war effort by diversifying their diets with these greens that sprouted in the woods during the late winter and early spring. Carver illustrated each wild green, including dandelion, wild lettuce, curled dock, lamb’s quarter, and pokeweed. Following the protocol used in botanical drawing, he credited the source, as he did with several illustrations identified as “after C.M. King.” This referenced the work of Charlotte M. King, who taught botanical drawing at Iowa State University during the time of Carver’s residency there, and who likely influenced Carver’s approach to botanical drawing. King’s original of the “Small Pepper Grass” drawing appeared in The Weed Flora of Iowa (1913), written by Carver’s mentor, botanist Louis Hermann Pammel.

Edible wild botanicals, also known as weeds, appeared in late winter. Carver encouraged everyone from his students at Tuskegee to Henry Ford to consumer more wild greens year round, but especially in late winter when greens became a welcome respite from root crops and preserved meats which dominated winter fare. His pamphlet, Nature’s Garden for Victory and Peace, prepared during World War II, featured numerous drawings of edible wild botanicals, also called weeds. Americans could contribute to the war effort by diversifying their diets with these greens that sprouted in the woods during the late winter and early spring. Carver illustrated each wild green, including dandelion, wild lettuce, curled dock, lamb’s quarter, and pokeweed. Following the protocol used in botanical drawing, he credited the source, as he did with several illustrations identified as “after C.M. King.” This referenced the work of Charlotte M. King, who taught botanical drawing at Iowa State University during the time of Carver’s residency there, and who likely influenced Carver’s approach to botanical drawing. King’s original of the “Small Pepper Grass” drawing appeared in The Weed Flora of Iowa (1913), written by Carver’s mentor, botanist Louis Hermann Pammel.

THF213586 / Pamphlet, "Nature's Garden for Victory and Peace," by George Washington Carver, March 1942.

To learn more about Carver, consult these biographies:

- Hersey, Mark D. My Work is that of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

- Kremer, Gary R. George Washington Carver: A Biography. Santa Barbara, Cal.: Greenwood, 2011.

- Kremer, Gary R. ed. George Washington Carver in His Own Words. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1987.

- McMurry, Linda O. George Washington Carver, Scientist and Symbol. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

To read more about Carver and Nature Study, see:

- Carver, G. W. Progressive Nature Studies. (Tuskegee Institute Print, 1897), Digital copy available at Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/98621#page/132/mode/1up

- Harbster, Jennifer. “George Washington Carver and Nature Study,” blog, March 2, 2015, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2015/03/george-washington-carver-and-nature-study/

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Deborah Evans is Master Presenter at The Henry Ford.

winter, nature, George Washington Carver, education, by Debra A. Reid, by Deborah Evans, art, agriculture, African American history

Ford Radio and Fordlandia

Henry Ford used wireless radio to communicate within Ford Motor Company (FMC) starting after October 1, 1919. This revolutionary new means of communication captured Ford’s interest because it allowed him to transmit messages within his vast operation. By August 1920, he could convey directions from his yacht to administrators in FMC offices and production facilities in Dearborn and Northville, Michigan. By February 1922, Ford’s railroad offices and the plant in Flat Rock, Michigan were connected, and by 1925, the radio transmission equipment was on Ford’s Great Lake bulk haulers and ocean-going vessels. Historian David L. Lewis claimed that “Ford led all others in the use of intracompany radio communications” (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 311).

Ford Motor Company also used radio transmissions to reach external audiences through promotional campaigns. During 1922, FMC sales branches delivered a series of expositions that featured Ford automobiles and Fordson tractors. An article in Motor Age (August 10, 1922) described highlights of the four-month tour of western Oregon:

“The days are given over to field demonstrations of tractors, plows and implements, while at night a radio outfit that brings in the concerts from the distant cities and motion pictures from the Ford plant, keep an intensely interested crowd on the grounds until the Delco Light shuts down for the night.”

The Ford Radio and Film crew that broadcast to the Oregon crowds traveled in a well-marked vehicle, taking every opportunity available to inform passers-by of Ford’s investment in the new technology – radio – and the utility of new FMC products. Ray Johnson, who participated in the tour, recalled that he drove a vehicle during the day and then played dance music in the evenings as a member of the three-piece orchestra, “Sam Ness and his Royal Ragadours.”

Ford and Fordson Power Exposition Caravan and Radio Truck, Seaside, Oregon, 1922 . THF134998

In 1922, Intra-Ford transmissions began making public broadcasts over the Dearborn’s KDEN station (call letters WWI) at 250-watts of power, which carried a range of approximately 360 meters. The radio station building and transmission towers were located behind the Ford Engineering Laboratory, completed in 1924 at the intersection of Beech Street and Oakwood Boulevard in Dearborn.

Ford Motor Company Radio Station WWI, Dearborn, Michigan, March 1925. THF134748

Staff at the station, conveying intracompany information and compiled content for the public show which aired on Wednesday evenings.

Ford Motor Company Radio Station WWI, Dearborn, Michigan, August 1924. THF134754

The station did not grow because Ford did not want to join new radio networks. He discontinued broadcasting on WWI in early February 1926 (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 179).

Ford did not discontinue his intracompany radio communications. FMC used radio-telegraph means to communicate between the head office in Dearborn and remote locations, including, Fordlandia, a 2.5-million-acre plantation that Ford purchased in 1927 and that he planned to turn into a source of raw rubber to ease dependency on British colonies regulated by British trade policy.

Brazil and other countries in the Amazon of South American provided natural rubber to the world until the early twentieth century. The demand for tires for automobiles increased so quickly that South American harvests could not satisfy demand. Industrialists sought new sources. During the 1870s, a British man smuggled seeds out of Brazil, and by the late 1880s, British colonies, especially Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) and Malaysia, began producing natural rubber. Inexpensive labor, plus a climate suitable for production, and a growing number of trees created a viable replacement source for Brazilian rubber.

British trade policies, however, angered American industrialists who sought to establish production in other places including Africa and the Philippines. Henry Ford turned to Brazil, because of the incentives that the Brazilian government offered him. His goals to produce inexpensive rubber faced several hurdles, not the least of which was overcoming the traditional labor practices that had suited those who harvested rubber in local forests, and the length of time it took to cultivate new plants (not relying on local resources).

Ford built a production facility on the Tapajós River in Brazil. This included a radio station. The papers of E. L. Leibold, in The Henry Ford’s Benson Ford Research Center, include a map with a key that indicated the “proposed method of communication between Home Office and Ford Motor Company property on Rio Tapajos River Brazil.” The system included Western Union (WU) land wire from Detroit to New York, WU land wire and cable from New York to Para, Amazon River Cable Company river cable between Para and Santarem, and Ford Motor Company radio stations at each point between Santarem and the Ford Motor Company on Rio Tapajós. Manual relays had to occur at New York, Para, and Santarem.

Map Showing Routes of Communication between Dearborn, Michigan and Fordlandia, Brazil, circa 1928. THF134693

Ford officials studied the federal laws in Brazil that regulated radio and telegraph to ensure compliance. Construction of the power house and processing structures took time. The community and corporate facilities at Boa Vista (later Fordlandia) grew. By 1931, the power house had a generator that provided power throughout the Fordlandia complex.

Generator in Power House at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134711

Power House and Water Tower at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134714

Lines from the power house stretching up the hill from the river to the hospital and other buildings, including the radio power station. The setting on a higher elevation helped ensure the best reception for radio transmissions.

Sawmill and Power House at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134717

Workers built the radio power house, which held a Delco Plant and storage batteries, and the radio transmitter station with its transmission tower. The intracompany radio station operated by 1929.

Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134697

Radio Transmitter House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134699

Storage Batteries in Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134701

Delco Battery Charger for Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134703

Radio Power House Motor Generator Set, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134705

The radio power house is visible at the extreme left of a photograph showing the stone road leading to the hospital (on an even higher elevation) at Fordlandia.

Stone Road Leading to Hospital, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134709

Radio Transmitter Station, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134707

Back at FMC headquarters in Dearborn, Ford announced in late 1933 that he would sponsor a program on both NBC and CBS networks. The Waring show aired two times a week between 1934 and 1937, when Ford pulled funding. Ford also sponsored World Series broadcasts. The most important radio investment FMC made, however, was the Ford Sunday Evening Hour, launched in the fall of 1934. Eighty-six CBS stations broadcast the show. Programs included classical music and corporate messages delivered by William J. Cameron, and occasionally guest hosts. Ford Motor Company printed and sold transcripts of the weekly talks for a small fee.

On August 24, 1941 Linton Wells (1893-1976), a journalist and foreign correspondent, hosted the broadcast and presented a piece on Fordlandia.

Program, "Ford Summer Hour," Sunday, August 24, 1941. THF134690

Linton Wells was not a stranger to Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village, he and his wife, Fay Gillis Wells, posed for a tintype in the village studio on 2 May 1940.

Tintype Portrait of Linton Wells and Fay Gillis Wells, Taken at the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, circa 1940. THF134720

This radio broadcast informed American listeners of the Fordlandia project, in its 16th year in 1941. Wells summarized the products made from rubber (by way of an introduction to the importance of the subject). He described the approach Ford took to carve an American factory out of an Amazonian jungle, and the “never-say-quit” attitude that prompted Ford to re-evaluate Fordlandia, and to trade 1,375 square miles of Fordlandia for an equal amount of land on Rio Tapajós, closer to the Amazon port of Santarem. This new location became Belterra. Little did listeners know the challenges that arose as Brazilians tried to sustain their rubber production, and Ford sought to grow its own rubber supply.

By 1942, nearly 3.6 million trees were growing at Fordlandia, but the first harvest yielded only 750 tons of rubber. By 1945, FMC sold the holdings to the Brazilian government (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 165).

The Ford Evening Hour Radio broadcasts likewise ceased production in 1942 after eight years and 400 performances.

Learn more about Fordlandia in our Digital Collections.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment; Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication and Information Technology; and Jim Orr is Image Services Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Sources

- Relevant collections in the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan.

- Grandin, Greg. Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City. Picador. 2010.

- Lewis, David L. The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1976.

- Frank, Zephyr and Aldo Musacchio. “The International Natural Rubber Market, 1870-1930.″ EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March 16, 2008.

South America, 20th century, 1940s, 1930s, 1920s, technology, radio, Michigan, Henry Ford, Fordlandia and Belterra, Ford Motor Company, communication, by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Jim Orr, by Debra A. Reid

The Dog Days of Summer

Is the saying, “dog days of summer,” about dogs? Not directly; at least, not about any farm dog (or city dog) we know. Instead, the “dog” is Sirius, the nose of the constellation, Canis Major, and the brightest star in the night sky. We get the best look at the constellation between November and April, but during late summer in the Northern hemisphere, Sirius appears in the eastern sky before dawn, and “rises” with the sun. Ancient Greeks considered Canis Major a homage to Orion’s greater hunting dog, Laelaps. Ancient Egyptians associated the rising of Sirius with the sun, and believed the “double sun” created the hottest season of the year. Today when we hear, “Sirius,” we might first think if Sirius Black, Harry Potter’s godfather, and not about the association between the star, Sirius, and summer heat. Let’s not forget the historic association between the hot “dog days of summer” and Sirius’ rising in tandem with the sun (July 22 through August 23).

During these “dog days,” let’s take a look at some of the photographs in The Henry Ford's collections, and think more about the dogs and the people that posed with them.

Woman Feeding Cats and Dog in a yard, circa 1900. THF211312

Can we tell whether Nellie consider her cats, or her dog as her “best friend”? It is difficult to tell because the image indicates that she paid attention to both the felines and the canine. A closer look indicates that the dog has a collar and that Nellie is either feeding him a treat or has a stick as a chew to distract him from the cats at the feed bowl.

A Young Girl and Her Dog, circa 1865. THF226464

Other photographs remind us that dogs lure us into a relaxed state. This carte-de-visite of a girl and her dog, taken in a photographer’s studio, shows a remarkably relaxed pose given the often formal and stiff portraits of the Civil War era. How many of us spend hours lounging with our own dogs?

John Burroughs with His Dog, “I Know,” 1885-1890. THF113982

Famous men struck poses with their favorite dogs, too. This photograph of internationally renowned naturalist, John Burroughs, shows him at eye level with his dog, “I Know,” sometime between 1885 and 1890. A closer look at “I Know” indicates that he has some border collie features, including his alert view and focus beyond the camera, the furry, light-colored ruff, and the white blaze on his face.

John Burroughs at his birthplace, Roxbury, New York, 1918. THF241519

A photograph taken thirty years later (1918) shows John Burroughs at his birthplace in Roxbury, New York, with another attentive border-collie-type dog. This photograph could be of anyone anywhere with a loyal canine pet.

Trade Card for Cultivating Tools, Syracuse Chilled Plow Co., circa 1880. THF225590

Do your hunting expeditions involve dogs? A trade card advertising Syracuse Chilled Plow Company cultivators, featured a colorful scene of a hunter with two bird dogs.

"Eager for Deer," Man and Dogs Ready for Hunting in the Woods, circa 1903 THF118863

Working dogs had jobs to do, but they also bonded with their handlers. A photograph of a man sitting on a felled tree has seven hunting dogs close in proximity, including one in his arms. At least one of the dogs is on a chain, and most have collars, tools which helped hunters controlled the pack of dogs that they used to flush out deer or other game from heavily wooded areas.

Edsel Ford with His Pet Dog at the Ford's Edison Avenue House, Detroit, Michigan, circa 1908. THF95291

Other dogs lived more of a life of leisure. A photograph of Edsel Ford taken around 1908, had the following inscription on the back: "Edsel & his dog, sitting on step that goes down into our garden. Garrage (sic) in rear.” Clara Bryant Ford likely took the photograph and wrote the description. It was taken at the Edison Avenue Home in Detroit.

Boy on a Bicycle Holding a Dog, circa 1950. THF201327

Compassion can make young men do some surprising things to protect their dogs. Some dogs romp in the snow, but this fellow seems to be sparing his little rat terrier the shock by giving him a ride on the back of his bicycle.

Little Snoopy pull toy, 1968-1975. THF97420

Numerous images of dogs and of objects featuring dogs exist in the collections of The Henry Ford. How many of our parents thought they could use a “Little Snoopy” pull toys to distract us from the craving for a real dog?

You can see more dog-related items in The Henry Ford collections here.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Stories of the USCT

”We are Bound for Glory with a Fair Wind, Nothing but Working and Fighting Ahead.” – Samuel Chapman Armstrong, Lt. Col., 9th USCT, between Hilton Head, South Carolina and Petersburg, VA, 1864

The American Civil War was the seminal event affecting daily life and ideals about freedom and citizenship during the 1860s and beyond. People coped with the reality of war-time devastation in a variety of ways. As the Civil War generation passed during the late 1920s and 1930s, when the collections of The Henry Ford were forming, the sacred family mementos that associated with personal memories of pride, honor and glory became part of this great museum of the American experience. Even though The Henry Ford is not a military history museum, the collections are rich with Civil War photographs and letters, battlefield relics, and even a medal of honor. The war is deeply imbedded in the collective memory of 19th and early 20th century Americans, and it was so often included in the “archives” of their lives that, by default, their mementos became part of our collections.

Henry Ford’s own interest in documenting the lives of his parents and his own childhood and young adulthood, caused him to collect his own family’s rich Civil War stories. Two of Henry’s mother’s brothers, John and Barney Litogot, served in the storied 24th Michigan. John was killed near Fredericksburg, Virginia, and Barney survived to fight in many battles, including Gettysburg. He also served in the honor guard at Abraham Lincoln’s funeral.

John and Barney Litogot at the time of their enlistment, August, 1862. THF 226852

The variety of Civil War objects in the collection is amazing, and represents both Union and Confederate perspectives.

Keeping troops in the field proved challenging for the Confederacy and the Union. A broadside confirms pay scales for Union troops and employees of the United States Army.

Recruiting Broadside, United States Army, c1863. THF 8551

Lackluster enlistment, however, prompted both armies to institute conscription. The Confederacy did this in April 1862 and the Union followed in March 1863.

The U.S. Army issued broadsides to recruit soldiers, including men of African descent, after passage of the Emancipation Proclamation. One broadside in the collection depicts a white male standard bearer front and center and elevated above others in the scene. He is armed with a sword and the banner, “Freedom to the Slave.” To the left sits a public school and a black man reading a newspaper rather than manning the plow. This implied that education and literacy could free people from manual labor. To the right, a black soldier aids black women and children recently freed from the shackles of slavery while black troops fight in the background.

“Freedom to the Slave. . . Fight for the Stars and Stripes,” 1863-1865. THF 118383

Black men had opportunities to serve in the Union forces before the Emancipation Proclamation. In fact, in May 1862, General David Hunter, in command of occupying forces in Hilton Head, South Carolina, organized the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. He acted without permission of the War Department and reputedly impressed men enslaved on plantations in the occupied territory into service. This sparked controversy about whether contraband of war, the enslaved in occupied territory, could, or should, serve in the military. The regiment disbanded in August 1862

Wood Engraving, First and Last Dress Review of 1st Regiment South Carolina (Negro) Volunteers, 1862. THF 11672.

The Militia Act on July 1, 1862 made it legal for the U.S. President, as commander in chief, to accept “persons of African descent” into the Union military or navy. The Militia Act authorized their pay and rations equivalent to that of soldiers already serving, but instead of $13 per month, they received $10 per month, with the remaining $3 paid in clothing). It also allowed persons of African descent to work for the Union, performing camp service and building fortifications.

Union officers reorganized the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry in November 1862, in conjunction with the Port Royal Experiment to redistribute lands on the Sea Islands of South Carolina to the formerly enslaved. Company A, under command of Charles T. Trowbridge, became the first official regiment of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) on January 1, 1863, the same day that officials read the Emancipation Proclamation for the first time, in Beaufort, South Carolina, on Port Royal Island, just south of Fort Sumter. The First South Carolina was renamed the 33rd U.S. Colored Infantry in 1864 and remained in service until January 31, 1866.

"Dress Parade of the First South Carolina Regiment (Colored) near Beaufort, South Carolina," 1861-1865. THF 8221

Stories of tragedy and triumph abound in the history of the USCT, including experiences lived by residents on our own Susquehanna Plantation.

Susquehanna as it appears in Greenfield Village today. THF 2024

Morris Robertson, an enslaved carpenter, left Susquehanna and enlisted with the Federal Army on October 25, 1863. He became a member of the 9th USCT, Company C. This regiment was organized at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland, from November 11 to December 31, 1863. They saw service in South Carolina and Virginia, including Petersburg and Richmond. Following the end of hostilities, the regiment was moved to Brownsville, Texas, where it remained until September 1866. The 9th was ordered to Louisiana in October and mustered out at New Orleans, November 26, 1866. Sadly, it was in Brownsville, Texas, very near the end of his term of service that Morris Robertson died of cholera on August 25, 1866. We would like to think that Morris’ brief time of freedom, though under frequent periods of extreme danger, gave him some joy. It is troubling to know that though free, he would never see his family again.

Service Record for Morris Robertson from the Company Descriptive Book. (Library of Congress)

Other objects in the collections document USCT in several other states, and confirms their service across the Confederate States from Virginia to south Texas. Examples include the 54th Massachusetts, perhaps the most well-known USCT regiment. It received national media attention in July 1863 for its “gallant charge” on rebel-held Fort Wagner, on Morris Island in the Charleston, South Carolina harbor.

Lithograph: GALLANT CHARGE OF THE FIFTY FOURTH (COLORED) MASSACHUSETTS REGIMENT / On the Rebel Works at Fort Wagner; Morris Island near Charleston, July 18th 1863, and the death of Colonel Robt. G. Shaw. THF 73704

USCT saw action in the Gulf of Mexico. Evidence includes a portrait of J.D. Brooker. Inscriptions on the back of the photo matte indicated that Brooker served with the Corps d’Afrique, 79th Regiment of Infantry. U.S. Army recruiters worked at the parish-level in occupied Louisiana, to attract volunteers. Troops saw heavy action during the Port Hudson campaign, May through July 1863. Major General Nathaniel P. Banks praised the Corps--"It gives me great pleasure to report that they answered every expectation. In many respects their conduct was heroic. No troops could be more determined or more daring."

Portrait of J.D. Brooker, soldier with the Corps d'Afrique 79th U.S. Colored Troops from Louisiana. THF 93151

Fragments of “our flag” were glued to the back of J.D. Brooker’s portrait.

Collections include portraits of white commanding officers of black troops.

Union Army Colonel Bernard Gains Farrar, who assisted in the siege of Vicksburg, recruited African-American troops from the area after Vicksburg fell. He commanded the 6th U. S. Colored Heavy Artillery.

Portrait of a Union Army Colonel Bernard Gains Farrar, 1862-1864. THF 6229

Lieutenant Andrew Coats, served with the 7th Colored Infantry Regiment and as Acting Assistant Adjutant General for the District of Florida. In 1864, the 7th Colored Infantry Regiment was part of the 10th Army Corps, located in the area of Hilton Head and Beaufort, South Carolina.

Portrait of Lieutenant Andrew Coats, 7th Colored Infantry Regiment, 1864. THF 57539

Americans of African descent remained the fulcrum around which debates about status and citizenship revolved. An 1864 print by Currier and Ives, conveyed this debate graphically as a contrast between the George B. McClellan, the Democratic presidential candidate, who wanted to restore the Union, but not abolish slavery, and the incumbent, Abraham Lincoln, author of the Emancipation Proclamation. If McClellan won the election, the CSA president, Jefferson Davis, would slit their throats. If President Lincoln retained his seat, black soldiers could stand at Lincoln’s right hand, defending the Union of States against CSA president Davis, in rags and on his posterior and held at bay by Lincoln. Black soldiers, however, remained culturally distinctive in the Currier and Ives depiction, as the dialect in the captioning re-enforced.

“Your Plan and Mine,” Political Cartoon, Presidential Campaign, 1864. THF 251879

Our collections also document post-war service of USCT. The Muster Roll for Company E, 46th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry confirmed the presence of men serving in the Regiment between April 30 and June 30, 1865. It also included names of at least fifteen men who had been taken as prisoners of war and men who had been discharged and deceased. The roll may have been used to keep track of soldiers after the war, perhaps for pension applications. Some annotations are dated 1885 and 1890. The Company E, 46th Regiment USCT saw action in Arkansas and the Mississippi Delta.

Another muster roll, confirmed the presence of thirteen soldiers in Company G, 25th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry, on April 12, 1865. Col. F.L. Hitchcock, commanding officer of the troops in Fort Barrancas, Florida, signed the roll. It includes details about each soldier:

Name; Rank; Date mustered in; Place mustered in; Mustered in by [name]; How long in service; Hair color; Eye color; Complexion color; Height (feet and inches); Where born; Age; Occupation; Pay information.

The 25th Regiment USCT was on garrison duty at Fort Barrancas, Florida, when these soldiers were recruited, and remained on garrison duty until December, 1865, never seeing action. During the spring and summer of 1865 about 150 men died of scurvy, the result of lack of proper food. Col. Hitchcock wrote:

"I desire to bear testimony to the esprit du corps, and general efficiency of the organization as a regiment, to the competency and general good character of its officers, to the soldierly bearing, fidelity to duty, and patriotism of its men. Having seen active service in the Army of the Potomac, prior to my connection with the Twenty-fifth, I can speak with some degree of assurance. After a proper time had been devoted to its drill, I never for a moment doubted what would be its conduct under fire. It would have done its full duty beyond question. An opportunity to prove this the Government never afforded, and the men always felt this a grievance."

Muster Roll of 13 Soldiers in Company G, 25th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry, April 12, 1865. THF 284824

As we pause to celebrate Memorial Day, a holiday with its origins linked to the Civil War, we need to pause to also honor all those who have given their lives in service, and all those who have, and continue to, serve to protect our freedoms. Americans did not agree on the meaning of freedom during the 1860s, and the evidence indicates that Americans of African descent were not given their freedom by white Americans. They fought during the Civil War to attain it.

Jim Johnson is Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes at The Henry Ford. Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

1860s, 19th century, Civil War, by Jim Johnson, by Debra A. Reid, African American history