Posts Tagged farm animals

Horse Power

Detail, 1882 advertisement showing a three-horse tread power in use. / THF277170

How much horsepower really comes from a horse? While the answer to this may seem obvious, it is complicated. The most complete answers start out with "it depends."

Much of farming is strenuous, tedious, repetitive work. For American farmers, chronic labor shortages made the effort of farm work even more taxing, so they looked for ways to get farm work done with less manpower. Horses and oxen were the main source of power, used for centuries for plowing. Improved farm machinery throughout the 1800s added the power of horses to other activities such as planting, cultivating, and, eventually, mowing and harvesting. Farmers understood the effort required for these tasks in terms of the number of horses needed to pull the equipment, such as one horse for a cultivator, and three or more for a harvester or large plow. Applying the power of horses to farm work helped to steadily increase the productivity of American farms throughout the 1800s.

This 1854 engraving depicted the centuries-old practice of plowing with horses. Throughout the 1800s, farmers increasingly used horses or oxen for other work as well, including planting, cultivating, mowing, and harvesting. / THF118302

Yet horsepower as a measure of power pre-dates the mechanization of the farm. It was developed by James Watt in the 1780s as a way to measure the output of a steam engine. Horsepower was based on his observations of how much work a horse could do in a normal ten-hour day, pulling the sweep arms of the horse-powered pumps that were used to remove water from mines. This worked out to 33,000 foot-pounds per minute, or the effort required to raise 33,000 pounds of water by one foot in one minute.

An 1886 trade catalog depicted Russell & Co.’s “New Massillon” grain thresher powered by both a steam traction engine and a horse-driven sweep power. / THF627487, THF627489

As farmers mechanized barn or farmyard work like threshing, winnowing, corn shelling, and corn grinding, they began to use stationary power sources—either treadmills and sweeps powered by horses, or steam engines. Here, the agricultural idea of horsepower and the industrial idea of horsepower bumped heads. For example, the portable steam engine pictured just below is rated at ten horsepower. It could be used to run the same piece of farm equipment as the two-horse tread power depicted below the steam engine, which used, well, two horses. Some farmers came to use a rule of thumb for farm equipment, calculating that one horse was worth about three horsepower in an engine. Why is this?

This ten-horsepower steam engine (top) could power the same piece of farm equipment as a two-horse tread power (bottom). / THF92184, THF32303

Engine horsepower ratings (and there are many varieties of these) are typically overestimated because they are often calculations of the power delivered to the machine—not how much actually reaches its "business end." For example, they do not account for power losses that occur between the piston and whatever the piston is driving—which can be more like 70% to 90% of the rated horsepower. In addition, those measures are made at the ideal engine speed.

On the other hand, numerous studies have shown that peak horsepower for a horse (sustainable for a few seconds) is as high as 12-15 horsepower. This is based on calculated estimates, as well as observed estimates (recorded in a 1925 study of the Iowa State Fair's horse pull). Over the course of a ten-hour workday, however, the average output of a horse is closer to one horsepower—which coincides with James Watt's original way of describing horsepower.

So how much horsepower comes from a horse? As we see, it depends. If we measure it in an optimal way, as we do with engines, it is as high as 15 horsepower. If we measure it as James Watt did—over the course of a long 10-hour day, horses walking in a circle—it gets down to about one horsepower. Nineteenth-century farmers quickly learned that if they were buying an engine for a task horses had previously performed, they needed an engine rated for three horsepower for every horse they had used for the task.

This post by Jim McCabe, former Collections Manager and Curator at The Henry Ford, originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series in May 2007. It was updated for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content.

Additional Readings:

- Microscope Used by George Washington Carver, circa 1900

- Bringing in the Beans: Harvesting a New Commodity

- As Ye Sow So Shall Ye Reap: The Bickford & Huffman Grain Drill

- Oliver Chilled Cast Iron Plow, circa 189

engines, by Saige Jedele, by Jim McCabe, power, agriculture, farms and farming, farming equipment, farm animals

Horse-Drawn Vehicles in the Country

Farm wagon with horse and driver, 1911–1915. / THF200478

During the Carriage Era, while large American cities were crowded with horses, rural areas had fewer animals—but horses were just as important. In the country, horses were much less likely to be used for hauling people and more likely to pull farm equipment, such as plows and reapers, or to haul wagons loaded with hay, grain, cotton, or freight.

In large parts of the South, mules (the offspring of male donkeys and female horses) were preferred over horses. Mules are sterile and so cannot reproduce on their own, but live longer than horses. Southerners believed that mules withstood heat better than horses, though they are smaller and weaker than the large draft-horse breeds. Unlike horses, mules will refuse to be overworked. Their famous “stubbornness” is in reality a self-preservation method—when tired, they simply stop and will not resume their labor until their energy is restored.

Uses for Horse-Drawn Vehicles in the Country

At the beginning of the 19th century, rural horses were primarily employed in tilling the soil, pulling plows, harrows, and cultivators. But later in the century, inventive minds rolled out a steady stream of new farm equipment—reapers, rakes, binders, mowers, seed drills, and manure spreaders. Implements that could be pulled with one or two horses gave way to four-horse plows, eight-horse disc harrows, and giant combines pulled by 25 mules. In addition, every farmer needed one or more wagons for hauling crops to market or supplies from town.

For much of the 19th century, most farmers could not afford vehicles whose only purpose was hauling people. The family could always ride in a wagon. But by mid-century, light people-hauling buggies were cheap enough for some to afford. Mechanization caused their price to fall steadily, so that by the end of the century, one could mail-order a buggy from Sears or Montgomery Ward for $25. Well before Henry Ford’s Model T automobile, cheap carriages whetted people’s appetites for inexpensive personal transportation that did not depend on public conveyances running on fixed routes and fixed schedules.

Milton Bryant with his nephew, Edsel Ford, in a typical farm buggy, 1894. / THF204970

A good deal of commercial transportation also moved through the countryside. Stagecoaches carried passengers between towns and cities. Freight wagons hauled goods from depots to towns not served by railroads. Commodities like kerosene were distributed by wagon.

Horse-Drawn Country Vehicle Highlights from The Henry Ford’s Collection

Fish Brothers Farm Wagon, 1895-1902

THF80599

This is a typical, all-purpose farm wagon with a basic square-box body and a seat mounted on leaf springs. Wagons like these were usually drawn by two horses, and thousands were made by many companies across the country. Franz Eilerman of Shelby County, Ohio, bought this particular wagon, which is on exhibit in Agriculture and the Environment in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, in 1902 for his son, Henry.

Hay Wagon, circa 1890

THF80616

This wagon, used in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, is an example of a special purpose wagon. It has flared sides to increase its load-carrying capacity and includes tall end racks, called “hay ladders,” to assist in tying down large loads of hay. In a horse-powered world, hay was an essential crop. While much hay was used on farms, huge quantities were also transported to cities on wagons like this and sold at central hay markets.

Buckboard Used by the Dr. George E. Woodbury Family, circa 1885

THF87328

The buckboard is an American innovation. It is essentially a pair of axles connected by springy floorboards mounting a seat. The floorboards provide a springing action in place of a heavier, more complex spring system. Buckboards were developed in the first third of the 19th century and could carry both people and goods. This rather elaborate buckboard with a pair of seats was used by a Massachusetts physician, Dr. George E. Woodbury, and was drawn by two horses.

Mail Wagon Used for Rural Delivery in Missouri, circa 1902

THF75675a

One of the major innovations that helped break down rural isolation was Rural Free Delivery (RFD), instituted by the Post Office Department in 1896. Prior to 1896, farmers had to pick up their mail at the post office. Rural mail carriers were required to provide their own vehicles, and many chose light mail wagons like this one. Its wood and canvas construction keeps its weight down, and it features pigeonholes for sorting mail. It is even outfitted with a coal-burning stove to keep the mail carrier warm in winter. This wagon was used by August Edinger to deliver mail in Kimmswick, Missouri, from 1902 to 1925. In 1925, he bought a Model T Ford and retired his horse-drawn wagon.

Oil Tank Wagon for Standard Oil Company, circa 1892

THF80588

Standard Oil of Indiana used wagons like this one to distribute kerosene and lubricating oils throughout the Midwest. By 1902, some 6,000 such wagons plied the rural roads. This two-horse wagon served the region of Michigan between Chicago and Detroit.

Pleasure Wagon, circa 1820

THF75657

The pleasure wagon is an American innovation developed in the early 19th century. The idea was to create a light wagon suitable for carrying both people and goods. The seat is mounted on long pieces of wood that serve as springs; the seat can be removed to increase the carrying capacity. The wagon is suspended on leather thoroughbraces and is highly decorated with paint. It was drawn by a single horse.

Skeleton Break, circa 1900

THF148858

Horses had to be trained to pull vehicles and farm implements. A whole class of vehicles called breaks was created for this purpose. Individual farmers would likely not have breaks, but breeders would have them so they could break their animals to the harness before selling them.

This vehicle takes its name from its purpose—to break, train, and exercise pairs and teams of carriage horses. Heavily built, to give animals the feel of a heavy carriage, it can also stand the abuse that unruly horses might give it. An unbroken horse was usually matched with a steady, reliable horse during training.

Julian Stage Line Stage Wagon, circa 1900

THF75679

Lighter and less expensive than the more famous Concord coach, stage wagons served much the same purpose. They carried passengers and mail over designated rural routes on a regular schedule. This one ran between Julian, a California mining town, and Foster Station, where passengers caught a train for the 25-mile trip to San Diego. This wagon was pulled by two, possibly four, horses.

Two-Horse Treadmill-Type Horse Power, circa 1900

THF32303

Not all horse power was used to pull vehicles. With the aid of treadmills, sweeps, and whims, horses could become portable motors for powering sugar cane mills, threshers, corn shellers, small grain elevators and so forth. This two-horse model of treadmill, on exhibit in the Soybean Lab Agricultural Gallery in Greenfield Village, is typical: The horses walked on an endless belt, turning wheels that could power machines.

Runabout, 1876

THF87349

An example of the light, relatively cheap passenger vehicles that appeared in the last quarter of the 19th century, this runabout features James B. Brewster’s patented sidebar suspension and extremely light, steam-bent hickory wheels. It exemplifies the light construction that came to characterize American carriages, weighing just 96 pounds. It was pulled by a single horse.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Transportation: Past, Present, and Future—From the Curators.”

Additional Readings:

- Agriculture and the Environment

- A Horse-Drawn Recycler: The Manure Spreader

- Fordson Tractor, 1917-1918, Used by Luther Burbank

- Hidden Histories of the Cotton Gin

farming equipment, horse drawn transport, farms and farming, farm animals, by Bob Casey

The Carriage Era: Horse-Drawn Vehicles

In this country of “magnificent distances,” we are all, more or less, according to the requirements of either business or pleasure, concerned in the use of riding vehicles.

— The New York Coach-Maker’s Magazine, volume 2, number 4, 1860

This print, circa 1875, depicts a variety of horse-drawn vehicles available from Frank D. Fickinger, a manufacturer in Ashtabula, Ohio. / THF288907

The period from the late 17th century until the first decades of the 20th century has been called by many transportation historians the “Carriage Era.” In the 17th and 18th centuries, carriages were extremely expensive to own and maintain and consequently were scarce. Because roads were poor and vehicle suspension systems rather primitive, riding in a carriage or wagon was not very comfortable. As the 19th century advanced, industrialization profoundly affected the production, design, and use of horse-drawn vehicles. In the United States, the combination of industrialization and the ingenuity of individual vehicle designers and makers made possible the production of a wide range of vehicles—some based on European styles, but many developed in the United States.

The Horse as a Living Machine

The horse is looked on as a machine, for sentiment pays no dividend.

— From W.J. Gordon, The Horse World of London, 1893

Horses pulling a carriage filled with people start as a dog barks, in this circa 1893 trade card for Eureka Harness Oil and Boston Coach Axle Oil. / THF214647

For most of the Carriage Era, business owners regarded horses primarily as machines whose principal value was in the profits that could be derived from their labor. One pioneer of modern breeding, Robert Bakewell, said that his goal was to find the best animal for turning food into money.

The vehicles themselves really make up only half of the machine. The other half, the half that makes the carriage or wagon useful, is the horse itself. In engineering terms, the horse is the “prime mover.” Thinking of a vehicle and a horse as two parts of the same machine raises many questions, such as:

- What sort of physical connection is needed between the horse and the vehicle? How do we literally harness the power of the horse?

- How do we connect more than one horse to a vehicle?

- How is the horse controlled? How does the driver get him to start, stop, and change direction?

- How are vehicles designed to best take advantage of the horse’s capabilities?

- Assuming the same weight, are some vehicle styles or types harder to pull than others?

- Are horses bred for specific purposes or for pulling specific types of vehicles?

- How much work can a horse do?

But despite what horse owners of the Carriage Era thought, horses are not merely machines—they are living, sentient beings. They have minds of their own, they feel pain, they get sick, and they experience fear, excitement, hunger, and fatigue. Today we would blanch at regarding the horse as simply a means of turning food into money.

The Aesthetic Dimension and Uniquely American Traits of Horse-Drawn Vehicles

A carriage is a complex production. From one point of view it is a piece of mechanism, from another a work of art.

—Henry Julian, “Art Applied to Coachbuilding,” 1884

Kentucky governor J. C. W. Beckham is among the party aboard this horse-drawn coach at the 27th running of the Kentucky Derby in Louisville in 1901. / THF203336

Horse-drawn vehicles were created with aesthetic as well as practical objectives. Aesthetics were asserted with the broadest connotation, expressing social position, concepts of beauty, elevation of sensibility, and the more formal attributes of design and details of construction. Horse-drawn vehicles traveled at slow speeds—from 4 to 12 miles per hour. This allowed intense scrutiny, as evidenced by 19th-century sources ranging from etiquette books to newspaper articles. From elegant coaches to colorful commercial vehicles, pedestrians and the equestrian audience alike judged aesthetics, design, and detail. In many respects, carriages were an extension of a person, like their clothes.

During the 19th century, there were many arenas for owners to display their horse-drawn vehicles. New York’s Central Park included roads designed for carriages. Central Park was a work of landscape art, and architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux saw elegant horse-drawn vehicles as essential, mobile parts of that landscape. Other cities developed similar parks on a smaller scale. But a park was not necessary—any street or road was an opportunity to show off.

Horse-drawn vehicles carry passengers through New York’s Central Park around 1900. / THF203316

Central to horse-drawn vehicle aesthetics was the “turnout.” This meant not only the vehicle itself, but also the horses, the harness, the drivers, and often the passengers. Horses were chosen to harmonize with the size and color of the vehicle, and their harness, the drivers’ uniforms, and even the passengers’ clothes were expected to harmonize as well.

Elegant turnout was not limited to the carriages of the rich. Businesses knew that their vehicles sent a message about the business itself. A smartly turned-out delivery wagon or brewery wagon told everyone that the company that owned the vehicle and team was a quality operation. Even the owner of a simple buggy could make an impression by hitching up a good-looking horse and wearing his best clothes.

These purveyors of “table luxuries” in New York, circa 1890–1915, used a horse-drawn vehicle that showed off their products—both via artwork on their wagon and via the goods themselves. / THF38079

Many things influenced the styling of vehicles. In the United States, one of the unexpected influences was natural resources. The country had abundant supplies of strong, light wood, like hickory. After 1850, more and more hickory began to be used in vehicles. American vehicles gradually took on a lighter, more spidery look, characterized by thin wheels and slim running gear. European observers were astonished at how light American vehicles were. Many American vehicles also moved away from smooth curves to adopt a sharper, more angular look. This had nothing to with function. It was simply an expression of fashion.

Diversity of Vehicle Types

When Alfred Sloan used the words, “A Car for Every Purse and Purpose,” he was describing General Motors’ goal of making a range of automobiles that filled every need and fit every budget. But substitute “horse-drawn vehicle” for “car,” and the statement could apply to the Carriage Era.

The sheer variety of horse-drawn vehicles is astonishing. There were elegant private carriages, closed and open, designed to be driven by professional drivers. At the other end of the scale were simple, inexpensive buggies, traps, road wagons, pony carts, and buckboards, all driven by their owners. Most passenger vehicles had four wheels, but some, like chaises, gigs, sulkies, and hansom cabs, had only two wheels. Commercial passenger vehicles included omnibuses, stagecoaches, and passenger wagons that came in several sizes and weights. Horse railway cars hauled people for decades before giving way to electrically powered streetcars.

This horse-drawn streetcar, or “horsecar,” circa 1890, traveled over fixed rails on set schedules, delivering residents of Seattle to and from places of work, shops, and leisure destinations. / THF202625

Work vehicles included simple drays for hauling heavy cargo, as well as freight wagons like the Conestoga and its lighter cousin, the prairie schooner. Delivery vehicles came in many sizes and shapes, from heavy beer wagons to specialized dairy wagons. Horses drew steam-powered fire engines and long ladder trucks. Bandwagons and circus wagons were familiar adjuncts to popular entertainments, and hearses carried people to their final reward. Ambulances carried people to hospitals, and specially constructed horse ambulances carried injured horses to the vet—or perhaps to slaughter if the injury was grave enough.

In the Carriage Era, horse-drawn hearses like this one, photographed in 1897, delivered the coffins of the deceased to their final resting places. / THF210197

On the farm, wagons came in many different sizes and were part of a range of vehicles that included manure spreaders, reapers, binders, mowers, seed drills, cultivators, and plows. Huge combines required 25 to 30 horses each. Rural vehicles often featured removable seats so they could do double duty, hauling both people and goods. Special vehicles called breaks were used to train horses to pull carriages and wagons. In winter weather, a large variety of sleighs was available, and many vehicles could be adapted to the snow by the substitution of runners for wheels.

This farmer’s wagon, with an open body and no driver's seat, was simple, but handy—it could readily haul this load of bagged seed or grain. / THF200482

In a series of forthcoming blog posts, we’ll look more closely at some of these very specific uses of horse-drawn transport, along with examples from our collections.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Transportation: Past, Present, and Future—From the Curators.”

There’s Only One Greenfield Village

Greenfield Village map, 1951. / THF133294

Greenfield Village map, 1951. / THF133294

Greenfield Village may just look like a lot of buildings to some, but each building tells stories of people. When I wrote The Henry Ford Official Guidebook, it really hit me how unique and one-of-a-kind Greenfield Village is. I wanted to share several stories I found particularly interesting about Greenfield Village.

Researching Building Stories

Whenever we research a Village building, we usually start with archival material—looking at sources like census records, account books, store invoices (like the one below, related to Dr. Howard’s Office), and old photographs—to give us authentic accounts about our subjects’ lives. Here are some examples.

1881 invoice for Dr. Howard. / THF620460

At Daggett Farmhouse, Samuel Daggett’s account book showed that he not only built houses but also dug stones for the community schoolhouse; made shingles for local people’s houses; made chairs, spinning wheels, coffins, and sleds; and even pulled teeth! If you are interested in learning more about how our research influenced the interpretation at Daggett, along with four other Village buildings, check out this blog post.

Daggett Farmhouse, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF54173

For Dr. Howard’s Office, we looked at old photographs, family reminiscences, the doctor’s daily record of patients and what he prescribed for them, his handwritten receipt (recipe) book of remedies, and invoices of supplies and dried herbs he purchased. You can read more about the history of Dr. Alonson Howard and his office in this blog post.

Page from Dr. Howard’s receipt book. / THF620470

For J.R. Jones General Store, we used a range of primary sources, from local census records to photographs of the building on its original site (like the one below) to account books documenting purchases of store stock from similar general stores. You can read more about the history of J.R. Jones General Store in this blog post.

Photo of J.R. Jones General Store on its original site. / THF255033

Urbanization and Industrialization Seen through Greenfield Village Buildings

Many Greenfield Village buildings were acquired because of Henry Ford’s interests. But some give us the opportunity to look at larger trends in American life, especially related to urbanization and industrialization.

Engelbert Grimm sold clocks and watches to Detroit-area customers, including Henry Ford, in the 1880s. But Grimm Jewelry Store also demonstrates that in an increasingly urban and industrial nation, people were expected to know the time and be on time—all the time.

Grimm Jewelry Store in Greenfield Village. / THF1947

Related to this, notice the public clock in the Detroit Publishing Company photograph below of West 23rd Street, New York City, about 1908. (Clue: Look down the street, above the horse-drawn carriage, and you’ll see a large street clock on a stand.) You can read more about the emergence of “clock time” in this blog post.

THF204886

Smiths Creek Depot is here because of its connection with Thomas Edison. But this building also shows us that railroad depots at the time were more than simply the place to catch a train—they were also bustling places where townspeople connected with the outside world. Below you can see a photo of Smiths Creek in Greenfield Village, as well asthe hustle and bustle of railroad depots in a wonderful image of the Union Pacific Depot in Cheyenne, Wyoming, from about 1910.

Smiths Creek Depot in Greenfield Village. / THF1873

Union Pacific Depot. / THF204972

Henry Ford brought Sarah Jordan Boarding House to Greenfield Village because it was home to many of Thomas Edison’s workers. It was also one of three residences wired for Edison’s new electrical lighting system in December 1879—and it is the only one still in existence. In the bigger picture, the mushrooming of boarding houses at this time was particularly due to a shortage of affordable housing in the growing urban-industrial centers, which were experiencing a tremendous influx of new wage laborers.

Sarah Jordan Boarding House in Greenfield Village. / THF2007

Sarah Jordan Boarding House on its original site in Menlo Park, New Jersey, in 1879. / THF117242

Luther Burbank and Henry Ford

Other buildings in Greenfield Village have strong ties to Henry’s personal relationships. Henry Ford met horticulturalist Luther Burbank in connection with the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. That year, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and a few other companions traveled there to attend Edison Day. Luther Burbank welcomed them to the area.

Panama-Pacific International Exposition Souvenir Medal. / THF154006

Afterward, the group followed Burbank up on an invitation to visit him at his experimental garden in Santa Rosa, California. Edison and Ford had a grand time there. Burbank later wrote, “The ladies said we acted like three schoolboys, but we didn’t care.”

Thomas Edison, Luther Burbank, and Henry Ford at Burbank's home in Santa Rosa, California. / THF126337

After that visit, the original group, plus tire magnate Harvey Firestone, drove by automobile to the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego. During that trip, Edison proposed a camping trip for Ford, Firestone, and himself. The Vagabonds camping trips, taking place over the next nine years, were born!

“Vagabonds” camping trip. / THF117234

Henry Ford was so inspired by Luther Burbank’s character, accomplishments, and “learning by doing” approach that he brought to Greenfield Village a modified version of the Luther Burbank Birthplace and a restored version of the Luther Burbank Garden Office from Santa Rosa.

Luther Burbank Garden Office in Greenfield Village. / THF1887

Greenfield Village Buildings and World’s Fair Connections

Greenfield Village has several other direct connections to World’s Fairs of the 1930s. At Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition of 1933–1934, for example, an “industrialized American barn” with soybean exhibits later became the William Ford Barn in Greenfield Village.

THF222009

In a striking Albert Kahn–designed building, Ford Motor Company boasted the largest and most expensive corporate pavilion of the same Chicago fair. It drew some 75% of visitors to the fair that year. After the fair, the central part of this building was transported from Chicago to Dearborn, where it became the Ford Rotunda. It was used as a hospitality center until it burned in a devastating fire in 1962.

Ford at the Fair Brochure, showing the building section that would eventually become the Ford Rotunda. / THF210966

Ford Rotunda in Dearborn after a 1953 renovation. / THF142018

At the Texas Centennial Exposition in 1936, a model soybean oil extractor was demonstrated. This imposing object is now prominently displayed in the Soybean Lab Agricultural Gallery in Greenfield Village.

A presenter at the Texas Centennial Exposition demonstrates how the soybean oil extraction process works with a model of a soybean oil extractor that now resides in the Soybean Lab in Greenfield Village. / THF222337

At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Henry Ford promoted his experimental school system in a 1/3-scale version of Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park Machine Shop in Greenfield Village. Students made model machine parts and demonstrated the use of the machines.

Boys from Henry Ford's Edison Institute Schools operate miniature machine replicas in a scale model of the Menlo Park Machine Shop during the 1939-40 New York World's Fair. / THF250326

Village Buildings That Influenced Famous Men

Several people whose stories are represented in Greenfield Village were influenced by the places in which they grew up and worked, like the Wright Brothers, shown below on the porch of their Dayton, Ohio, home, now the Wright Home in the Village, around 1910.

THF123601

In addition to practicing law in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln traveled to courthouses like the Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village to try court cases for local folk. The experiences he gained in these prepared him for his future role as U.S. president (read more about this in this “What If” story).

THF110836

Enterprising young Tom Edison took a job as a newsboy on a local railway, where one of the stops was Smiths Creek Station. This and other experiences on that railway contributed to the man Thomas Edison would become—curious, entrepreneurial, interested in new technologies, and collaborative.

Young Thomas Edison as a newsboy and candy butcher. / THF116798

Henry Ford, the eldest of six children, was born and raised in the farmhouse pictured below, now known as Ford Home in Greenfield Village. Henry hated the drudgery of farm work. He spent his entire life trying to ease farmers’ burdens and make their lives easier.

THF1938

Henry J. Heinz

Henry J. Heinz (the namesake of Heinz House in Greenfield Village) wasn’t just an inventor or an entrepreneur or a marketing genius: he was all of these things. Throughout the course of his career, he truly changed the way we eat and the way we think about what we eat.

H.J. Heinz, 1899. / THF291536

Beginning with horseradish, Heinz expanded his business to include many relishes and pickles—stressing their purity and high quality at a time when other processed foods did not share these characteristics. The sample display case below highlights the phrase “pure food products.”

Heinz Sample Display Case. / THF174348

Heinz had an eye for promotion and advertising unequaled among his competitors. This included signs, billboards, special exhibits, and, as shown below, the specially constructed Heinz Ocean Pier, in Atlantic City, New Jersey, which opened in 1898.

Advertising process photograph showing Heinz Ocean Pier. / THF117096

The pickle pin, for instance, was a wildly successful advertising promotion. Heinz first offered a free pickle-shaped watch fob at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. At some point, a pin replaced the watch fob, and the rest is history!

Heinz Pickle Pin "Heinz Homestyle Soups." / THF158839

By the time of H.J. Heinz’s death in 1919, his company had grown into one of the largest food processing businesses in the nation. His company was known for its innovative food processing, packaging, advertising, and enlightened business practices. You can learn more about Heinz House and its journey to Greenfield Village here.

Even More Fun Facts about Greenfield Village Buildings

Most of the time, we focus on big themes that tell American history in relatable ways. When we choose a theme to focus on, we inevitably leave out interesting little-known facts. For example, Cohen Millinery was a dry goods store, a candy store, a Kroger grocery, and a restaurant during its lifetime!

Cohen Millinery at its original site. / THF243213

Surprisingly, for most of its life prior to its incorporation into Greenfield Village, Logan County Courthouse was a private residence. Many different families had lived there, including Mr. and Mrs. Elijah Watkins, the last caretakers before Henry Ford acquired the building. They are depicted below, along with an interior shot of one of their rooms when Henry Ford’s agents went to look at the building.

Mr. and Mrs. Watkins. / THF238624

Interior of Logan County Courthouse at its original site. / THF238596

In the 1820s, eastern Ohio farmers realized huge profits from the fine-grade wool of purebred Merino sheep. But by the 1880s, competition had made raising Merino sheep unprofitable. Benjamin Firestone, the previous owner of Firestone Farmhouse and father of Harvey Firestone, however, stuck with the tried and true. Today, you can visit our wrinkly friends grazing one of several pastures in the Village.

Merino sheep at Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village in 2014. / THF119103

We have several different breeds of animals at the Village, but some of our most memorable were built, not bred. The Herschell-Spillman Carousel is a favorite amongst visitors. Many people think that all carousel animals were hand-carved. But the Herschell-Spillman Company, the makers of our carousel, created quantities of affordable carousel animals through a shop production system, using machinery to rough out parts. You can read more on the history of our carousel in this blog post.

THF5584

And there you have it! Remember, odd and anachronistic as it might seem at times—the juxtaposed time periods, the buildings from so many different places, the specific people highlighted—there’s only one Greenfield Village!

Presenters at Daggett Farmhouse. / THF16450

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

#THFCuratorChat, Wright Brothers, world's fairs, Thomas Edison, research, railroads, Luther Burbank, Logan County Courthouse, J.R. Jones General Store, Henry Ford, Heinz, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Ford Motor Company, farm animals, Dr. Howard's Office, Daggett Farmhouse, Cohen Millinery, by Donna R. Braden, archives, agriculture, Abraham Lincoln

“Whenever Henry Ford visited England, he always liked to spend a few days in the Cotswold Country, of which he was very fond … during these sojourns I had many happy times driving Mr. Ford around the lovely scenes which abound in this part of Britain.”

—Herbert Morton, Strange Commissions for Henry Ford

A winding road through a Cotswold village, October 1930. / THF148434, detail

The Cotswolds Catch Henry Ford’s Eye

Henry Ford loved the Cotswolds, a rural region in southwest England—nearly 800 square miles of rolling hills, pastures, and small villages.

During the Middle Ages, a vibrant wool trade brought the Cotswolds great prosperity—at its heart was a breed of sheep known as Cotswold Lions. For centuries, the Cotswold region was well-known throughout Europe for the quality of its wool. Raising sheep, trading in wool, and woolen cloth fueled England’s economic growth from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution. Cotswold’s prosperity and its rich belt of limestone that provided ready building material resulted in a distinctive style of architecture: limestone homes, churches, shops, and farm buildings of simplicity and grace.

During Henry Ford’s trips to the Cotswolds in the 1920s, he became intrigued with the area’s natural beauty and charming architecture—all those lovely stone buildings that “blossomed” among the verdant green countryside and clustered together in Cotswold’s picturesque villages. By early 1929, Ford had decided he wanted to acquire and move a Cotswold home to Greenfield Village.

A letter dated February 4, 1929, from Ford secretary Frank Campsall described that Ford was looking for “an old style that has not had too many changes made to it that could be restored to its true type.” Herbert Morton, Ford’s English agent, was assigned the task of locating and purchasing a modest building “possessing as many pretty local features as might be found.” Morton began to roam the countryside looking for just such a house. It wasn’t easy. Cotswold villages were far apart, so his search covered an extensive area. Owners of desirable properties were often unwilling to sell. Those buildings that were for sale might have only one nice feature—for example, a lovely doorway, but no attractive window elements.

Cotswold Cottage (buildings shown at left) nestled among the rolling hills in Chedworth, 1929–1930. / THF236012

Herbert Morton was driving through the tiny village of Lower Chedworth when he saw it. Constructed of native limestone, the cottage had “a nice doorway, mullions to the windows, and age mellowed drip-stones.” Morton knew he had found the house he had been looking for. It was late in the day, and not wanting to knock on the door and ask if the home was for sale, Morton returned to the town of Cheltenham, where he was staying.

The next morning Morton strolled along a street in Cheltenham, pondering how to approach the home’s owner. He stopped to look into a real estate agent’s window—and saw a photograph of the house, which was being offered for sale! Later that day, Morton arrived in Chedworth, and was greeted by the owner, Margaret Cannon Smith, and her father. The cottage, constructed out of native limestone in the early 1600s, had begun life as a single cottage, with the second cottage added a bit later.

Interior of Cotswold Cottage, 1929-1930. / THF236052

The home was just as quaint inside—large open fireplaces with the mantels supported on oak beams. Heavy oak beams graced the ceilings and the roof. Spiral stone staircases led to the second floor. Morton bought the house and the two acres on which it stood under his own name from Margaret Smith in April 1929 for approximately $5000. Ford’s name was kept quiet. Had the seller been aware that the actual purchaser was Henry Ford, the asking price might have been higher.

Cotswold Cottage (probably built about 1619) as it looked when Herbert Morton spotted it, 1929–1930. / THF236020

“Perfecting” the Cotswold Look

Over the next several months, Herbert Morton and Frank Campsall, Ford’s personal secretary, traded correspondence concerning repairs and (with the best of intentions on Ford’s part) some “improvements” Ford wanted done to the building: the addition of architectural features that best exemplified the Cotswold style. Morton sent sketches, provided by builder and contractor W. Cox-Howman from nearby Stow-on-the-Wold, showing typical Cotswold architectural features not already represented in the cottage from which to choose. Ford selected the sketch which offered the largest number of typical Cotswold features.

Ford’s added features on the left cottage included a porch (a copy of one in the Cotswold village of Rissington), a dormer window, a bay window, and a beehive oven.

Cotswold Cottage, 1929–1930, showing modifications requested by Henry Ford: the beehive oven, porch, and dormer window. / THF235980

Bay window added to the left cottage by Henry Ford (shown 1929–1930). Iron casement windows were added throughout. / THF236054

The cottage on the right got a doorway “makeover” and some dove-holes. These holes are commonly found in the walls of barns, but not in houses. It would have been rather unappealing to have bird droppings so near the house!

Ford’s modifications to the right cottage—a new doorway (top) and dove-holes (bottom) on the upper wall. / THF236004, THF235988

Cotswold Cottage, now sporting Henry Ford’s desired alterations. / THF235984

Ford wanted the modifications completed before the building was disassembled—perhaps so that he could establish the final “look” of the cottage, as well as be certain that there were sufficient building materials. The appearance of the house now reflected both the early 1600s and the 1920s—each of these time periods became part of the cottage’s history. Ford’s additions, though not original to the house, added visual appeal.

The modifications were completed by early October 1929. The land the cottage stood on was transferred to the Ford Motor Company and later sold.

Cotswold Cottage Comes to America

Cotswold Cottage being disassembled. / THF148471

By January 1930, the dismantling of the modified cottage was in process. To carry out the disassembly, Morton again hired local contractor W. Cox-Howman.

Building components being crated for shipment to the United States. / THF148475

Doors, windows, staircases, and other architectural features were removed and packed in 211 crates.

Cotswold building stones ready for shipment in burlap sacks. / THF148477

The building stones were placed in 506 burlap sacks.

Cotswold barn and stable on original site, 1929–1930. / THF235974

The adjacent barn and stable, as well as the fence, were also dismantled and shipped along with the cottage.

Hauled by a Great Western Railway tank engine, 67 train cars transported the materials from the Cotswolds to London to be shipped overseas. / THF132778

The disassembled cottage, fence, and stable—nearly 500 tons worth—were ready for shipment in late March 1930. The materials were loaded into 67 Great Western Railway cars and transported to Brentford, west London, where they were carefully transferred to the London docks. From there, the Cotswold stones crossed the Atlantic on the SS London Citizen.

As one might suspect, it wasn’t a simple or inexpensive move. The sacks used to pack many of the stones were in rough condition when they arrived in New Jersey—at 600 to 1200 pounds per package, the stones were too heavy for the sacks. So, the stones were placed into smaller sacks that were better able to withstand the last leg of their journey by train from New Jersey to Dearborn. Not all of the crates were numbered; some that were had since lost their markings. One package went missing and was never accounted for—a situation complicated, perhaps, by the stones having been repackaged into smaller sacks.

Despite the problems, all the stones arrived in Dearborn in decent shape—Ford’s project manager/architect, Edward Cutler, commented that there was no breakage. Too, Herbert Morton had anticipated that some roof tiles and timbers might need to be replaced, so he had sent some extra materials along—materials taken from old cottages in the Cotswolds that were being torn down.

Cotswold “Reborn”

In April 1930, the disassembled Cotswold Cottage and its associated structures arrived at Greenfield Village. English contractor Cox-Howman sent two men, mason C.T. Troughton and carpenter William H. Ratcliffe, to Dearborn to help re-erect the house. Workers from Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant also came to assist. Reassembling the Cotswold buildings began in early July, with most of the work completed by late September. Henry Ford was frequently on site as Cotswold Cottage took its place stone-by-stone in Greenfield Village.

Before the English craftsmen returned home, Clara Ford arranged a special lunch at the cottage, with food prepared in the cottage’s beehive oven. The men also enjoyed a sight-seeing trip to Niagara Falls before they left for England in late November.

By the end of July 1930, the cottage walls were nearly completed. / THF148485

On August 20, 1930, the buildings were ready for their shingles to be put in place. The stone shingles were put up with copper nails, a more modern method than the wooden pegs originally used. / THF148497

Cotswold barn, stable, and dovecote, photographed by Michele Andonian. / THF53508

Free-standing dovecotes, designed to house pigeons or doves which provided a source of fertilizer, eggs, and meat, were not associated with buildings such as Cotswold Cottage. They were found at the homes of the elite. Still, for good measure, Ford added a dovecote to the grouping about 1935. Cutler made several plans and Ford chose a design modeled on a dovecote in Chesham, England.

Henry and Clara Ford Return to the Cotswolds

The Lygon Arms in Broadway, where the Fords stayed when visiting the Cotswolds. / THF148435, detail

As reconstruction of Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village was wrapping up in the fall of 1930, Henry and Clara Ford set off for a trip to England. While visiting the Cotswolds, the Fords stayed at their usual hotel, the Lygon Arms in Broadway, one of the most frequently visited of all Cotswold villages.

Henry (center) and Clara Ford (second from left) visit the original site of Cotswold Cottage, October 1930. / THF148446, detail

While in the Cotswolds, Henry Ford unsurprisingly asked Morton to take him and Clara to the site where the cottage had been.

Cotswold village of Stow-on-the-Wold, 1930. / THF148440, detail

At Stow-on-the-Wold, the Fords called on the families of the English mason and carpenter sent to Dearborn to help reassemble the Cotswold buildings.

Village of Snowshill in the Cotswolds. / THF148437, detail

During this visit to the Cotswolds, the Fords also stopped by the village of Snowshill, not far from Broadway, where the Fords were staying. Here, Henry Ford examined a 1600s forge and its contents—a place where generations of blacksmiths had produced wrought iron farm equipment and household objects, as well as iron repair work, for people in the community.

The forge on its original site at Snowshill, 1930. / THF146942

A few weeks later, Ford purchased the dilapidated building. He would have it dismantled, and then shipped to Dearborn in February 1931. The reconstructed Cotswold Forge would take its place near the Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village.

To see more photos taken during Henry and Clara Ford’s 1930 tour of the Cotswolds, check out this photograph album in our Digital Collections.

Cotswold Cottage Complete in Greenfield Village—Including Wooly “Residents”

Completed the previous fall, Cotswold Cottage is dusted with snow in this January 1931 photograph. Cotswold sheep gather in the barnyard, watched over by Rover, Cotswold’s faithful sheepdog. (Learn Rover's story here.) / THF623050

A Cotswold sheep (and feline friend) in the barnyard, 1932. / THF134679

Beyond the building itself, Henry Ford brought over Cotswold sheep to inhabit the Cotswold barnyard. Sheep of this breed are known as Cotswold Lions because of their long, shaggy coats and faintly golden hue.

Cotswold Cottage stood ready to welcome—and charm—visitors when Greenfield Village opened to the public in June 1933. / THF129639

By the Way: Who Once Lived in Cotswold Cottage?

Cotswold Cottage, as it looked in the early 1900s. From Old Cottages Farm-Houses, and Other Stone Buildings in the Cotswold District, 1905, by W. Galsworthy Davie and E. Guy Dawber. / THF284946

Before Henry Ford acquired Cotswold Cottage for Greenfield Village, the house had been lived in for over 300 years, from the early 1600s into the late 1920s. Many of the rapid changes created by the Industrial Revolution bypassed the Cotswold region and in the 1920s, many area residents still lived in similar stone cottages. In previous centuries, many of the region’s inhabitants had farmed, raised sheep, worked in the wool or clothing trades, cut limestone in the local quarries, or worked as masons constructing the region’s distinctive stone buildings. Later, silk- and glove-making industries came to the Cotswolds, though agriculture remained important. By the early 1900s, tourism became a growing part of the region’s economy.

A complete history of those who once occupied Greenfield Village’s Cotswold Cottage is not known, but we’ve identified some of the owners since the mid-1700s. The first residents who can be documented are Robert Sley and his wife Mary Robbins Sley in 1748. Sley was a yeoman, a farmer who owned the land he worked. From 1790 at least until 1872, Cotswold was owned by several generations of Robbins descendants named Smith, who were masons or limeburners (people who burned limestone in a kiln to obtain lime for mixing with sand to make mortar).

As the Cotswold region gradually evolved over time, so too did the nature of some of its residents. From 1920 to 1923, Austin Lane Poole and his young family owned the Cotswold Cottage. Medieval historian, fellow, and tutor at St. John’s College at Oxford University (about 35 miles away), Poole was a scholar who also enjoyed hands-on work improving the succession of Cotswold houses that he owned. Austin Poole had gathered documents relating to the Sley/Robbins/Smith families spanning 1748 through 1872. It was these deeds and wills that revealed the names of some of Cotswold Cottage’s former owners. In 1937, after learning that the cottage had been moved to Greenfield Village, Poole gave these documents to Henry Ford.

In 1926, Margaret Cannon Smith purchased the house, selling it in 1929 to Herbert Morton, on Henry Ford’s behalf.

“Olde English” Captures the American Imagination

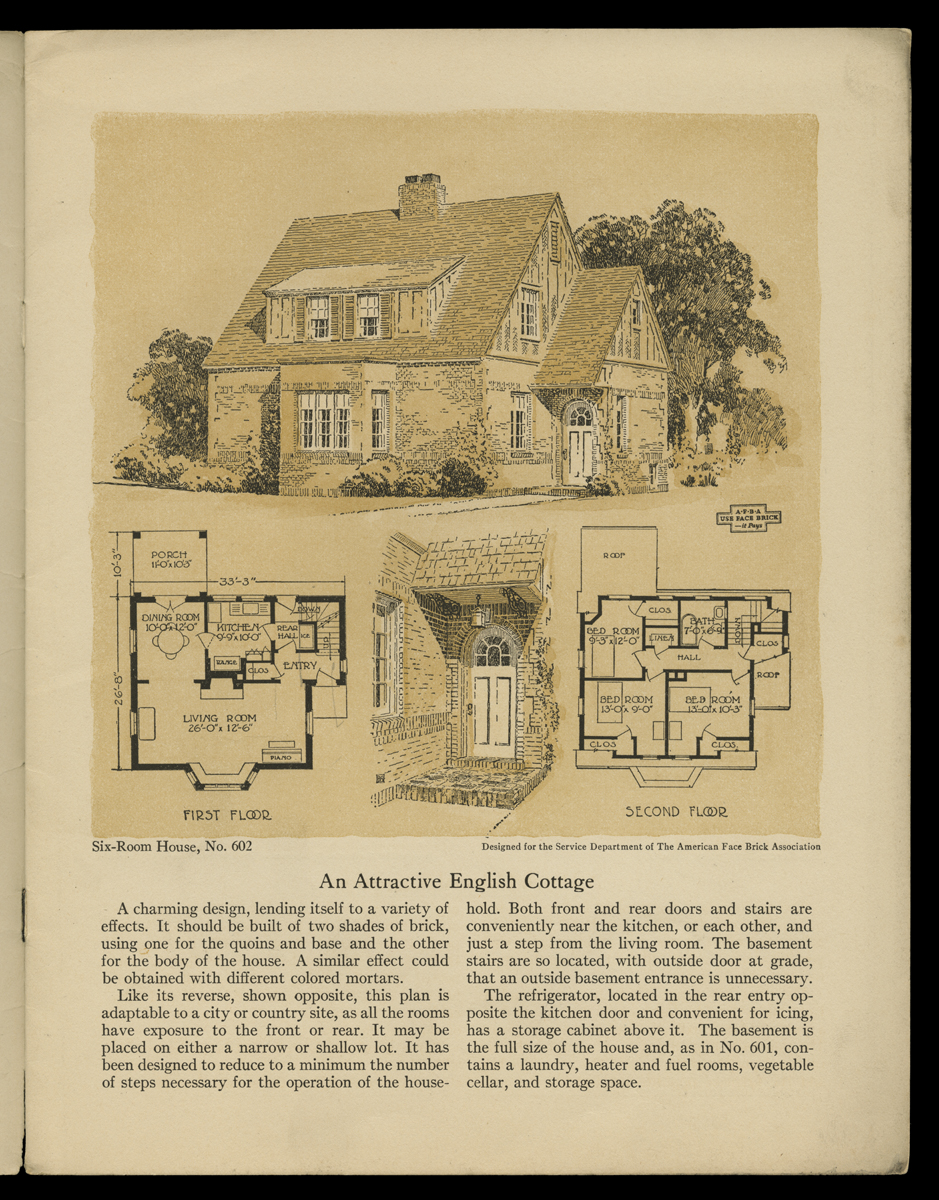

At the time that Henry Ford brought Cotswold Cottage to Greenfield Village, many Americans were drawn to historic English architectural design—what became known as Tudor Revival. The style is based on a variety of late Middle Ages and early Renaissance English architecture. Tudor Revival, with its range of details reminiscent of thatched-roof cottages, Cotswold-style homes, and grand half-timbered manor houses, became the inspiration for many middle-class and upper-class homes of the 1920s and 1930.

These picturesque houses filled suburban neighborhoods and graced the estates of the wealthy. Houses with half-timbering and elaborate detail were often the most obvious examples of these English revival houses, but unassuming cottage-style homes also took their place in American towns and cities. Mansion or cottage, imposing or whimsical, the Tudor Revival house was often made of brick or stone veneer, was usually asymmetrical, and had a steep, multi-gabled roof. Other characteristics included entries in front-facing gables, arched doorways, large stone or brick chimneys (often at the front of the house), and small-paned casement windows.

Edsel Ford’s home at Gaukler Pointe, about 1930. / THF112530

Henry Ford’s son Edsel and his wife Eleanor built their impressive but unpretentious home, Gaukler Pointe, in the Cotswold Revival style in the late 1920s.

Postcard, Postum Cereal Company office building in Battle Creek, Michigan, about 1915. / THF148469

Tudor Revival design found its way into non-residential buildings as well. The Postum Cereal Company (now Post Cereals) of Battle Creek, Michigan, chose to build an office building in this centuries-old English style.

Plan for “An Attractive English Cottage” from the American Face Brick Association plan book, 1921. / THF148542

Plans for English-inspired homes offered by Curtis Companies Inc., 1933. / THF148549, THF148550, THF148553

Tudor Revival homes for the middle-class, generally more common and often smaller in size, appeared in house pattern books of the 1920s and 1930s.

Sideboard, part of a dining room suite made in the English Revival style, 1925–1930. / THF99617

The Tudor Revival called for period-style furnishings as well. “Old English” was one of the most common designs found in fashionable dining rooms during the 1920s and 1930s.

Christmas card, 1929. / THF4485

Even English-themed Christmas cards were popular.

Cotswold Cottage—A Perennial Favorite

Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF53489

Henry Ford was not alone in his attraction to the distinctive architecture of the Cotswold region and the English cottage he transported to America. Cotswold Cottage remains a favorite with many visitors to Greenfield Village, providing a unique and memorable experience.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Cotswold Cottage Tea

- Interior of Cotswold Cottage at its Original Site, Chedworth, Gloucestershire, England, 1929-1930

- Cotswold Cottage

home life, design, farm animals, travel, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village, by Jeanine Head Miller

Rover: The Canine Keeper of Cotswold Cottage

Rover Keeping Watch outside Cotswold Barn, January 1931 / THF623050

When Cotswold Cottage and its surrounding buildings were brought to Greenfield Village, Henry Ford aimed to recreate every detail of one of his and Clara’s favorite regions of England.

Henry purchased the cottage, barn, and a nearby blacksmith shop for Greenfield Village in 1929 and the structures were shipped in 1930. Along with the disassembled structures came English stonemasons, who were tasked with reconstructing each building stone by stone. Henry promoted one of his own employees, Gus Munchow, to take charge of recreating the gardens and grounds around them.

Cotswold Cottage / THF1690

The earliest interpretation of Cotswold Cottage intended to present it as a home for English sheepherders. To fully bring this story to life, Henry had a group of sheep imported from the Cotswold region of England to take up residence on the grounds.

Cat Riding a Sheep at Cotswold Cottage, 1932 / THF134679

Plans for the Cotswold setting were nearly perfect, except for one very large missing detail.

When the English stonemasons recalled a black Newfoundland sheep dog roaming the original site, Henry inquired if the dog might consider a move to Michigan. The stonemasons suggested the dog “undoubtedly adored the King” and probably “did not like boats.” Instead, it was decided to find a substitute puppy that could be raised at the cottage to act as sheepherder and guardsman like his English predecessor.

Henry’s secretary began researching the best genetic strains of Newfoundland dogs and located a litter from a lineage of aristocratic, award-winning dogs nearby in Canada. Rover, deemed their best dog, was sent by train to Dearborn.

Rover at Cotswold Cottage, 1932 / THF134670

Rover was trained by Gus Munchow, manager of the gardens and grounds, and was given a home in the Cotswold barn—although some accounts recall he often made himself comfortable inside the cottage. Weighing more than 130 pounds by his first birthday, Rover quickly grew into a smart and dedicated companion to both the sheep and Gus.

Dedicated in all seasons, day and night, Rover happily attended to chores with Gus. He delivered feeding buckets to the sheep, carried extra tools, and was responsible for holding the clock on their night rounds.

Rover outside Cotswold Barn with Gus Munchow and Sheep / THF623048

One of several canine citizens of Greenfield Village at the time, Rover’s neighbors included two Dalmatian coach dogs and a Scottish Terrier named McTavish that enjoyed the company of the schoolchildren who learned in the Giddings Family Home next door.

Enthusiastic in his pursuit to keep any of the other Village dogs from approaching the grounds he guarded, Rover had the stature and size to insist upon them keeping their distance—and they happily obeyed.

Rover at Cotswold Cottage, 1932 / THF134667

Rover with Edison Institute Schoolchildren, Featured in The Herald, April 5, 1935 / THF623054

Even Henry Ford was an admirer of Rover. Gus recalled in his oral history: “That dog would only take orders from myself and Mr. Ford. Mr. Ford used to come through that gate, and the dog would run up to him, and he would play with him for a minute or two.”

Henry realized Rover’s deep bond to Gus when his beloved master fell ill in July 1934. Gus had suffered from appendicitis and was rushed to Henry Ford Hospital, where he stayed for more than a week. When Henry came to visit Rover, he found him lying in the middle of the road, unwilling to move. He seemed to be waiting for Gus to return and was refusing to eat. Realizing Rover must be distressed by Gus’s absence, he requested the dog receive a special bath and be driven in his personal car to the hospital.

The scene of the giant dog visiting the hospital caught the attention of the Detroit News, which wrote a feature article on the visit: “There was a great deal of difficulty in getting the large dog into the hospital, and once inside the door, he had to be dragged along. But when he approached the room where Gus lay and heard the sound of his master’s voice, he ran joyfully to the bed, jumped upon it, and threw everybody and everything into confusion.” The article was happy to report that following the reunion, Rover quickly regained both his appetite and the 15 pounds he had lost from worry.

Feature photo from a Detroit News article found in Ford Motor Company Clipping Book, Volume 88, April–November 1934 / THF623060

When Gus returned to work, Rover always had one eye on his sheep and one eye on his master, making sure neither wandered too far out of sight.

Rover continued serving Gus and Cotswold Cottage for many years. He was indeed “a very good and faithful pal” whose spirit will live on forever as part of Greenfield Village. His grave marker can still be seen today behind the cottage.

Rover’s grave marker, located behind Cotswold Cottage / Photo by Lauren Brady

Lauren Brady is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, 1930s, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, farm animals, by Lauren Brady

The Rise of the American Carding Mill

THF91531 (photographed by John Sobczak)

Carding mills became extremely popular in 19th-century America because the machines used in them mechanized the laborious hand process of straightening and combing wool fibers—an important step in preparing yarn and making woolen cloth. Customers were happy to let others handle this incredibly tedious job while using their own skill and creativity to control the final product.

Before carding mills, farm families prepared wool by hand using hand cards like these. / THF183701

Between 1840 and 1880, Michigan farmers raised millions of sheep, whose wool was turned into yarn and woolen goods. The Civil War, especially, caused a demand for wool, as it became the raw material for soldiers’ uniforms. Afterward, while the highest quality woolen broadcloth for men’s clothing was still imported from England, a growing number of wool mills (mostly small and local, but some larger ones, especially in New England) produced lower-end woolen goods like flannel (for work shirts, summer coats, and overcoat linings), men’s and children’s underwear, blankets, and rugs.

Sheep graze outside of Henry Ford’s boyhood home in Greenfield Village / THF1937

Farmers who raised large flocks of sheep might sell their raw wool to local merchants or to dealers who shipped it directly to a small wool mill in the local area or a large wool mill in New England. But most farm families raised a modest flock of sheep and spun their own wool into yarn, which they used at home for knitted goods. They might also take their spun yarn or items they knitted to their local general store for credit to purchase other products they needed in the store.

While sawmills and gristmills were the first types of mills established in newly-formed communities, carding mills rapidly became popular—particularly in rural areas where sheep were raised. While the tradition of wool spinning at home continued well into the 19th century, machine carding took the tedious process of hand carding out of the home. Learn more about the mechanization of carding in this blog post.

Faster and more efficient carding machines replaced traditional carding methods in the 19th century. / THF621302

At the carding mill, raw wool from sheep was transformed into straightened rolls of wool, called rovings—the first step to finished cloth. Faster and more efficient carding machines at these mills replaced the hand cards traditionally used at home (by women and children) for this process. Through the end of the 19th century, carding mills provided this carding service for farm families, meeting the needs of home spinners.

“Picked” wool that has been loosened and cleaned, ready to be fed into a carding machine / THF91532 (photographed by John Sobczak)

Young Henry Ford was a member one of these farm families. Henry fondly remembered accompanying his father on trips to John Gunsolly’s carding mill (now in Greenfield Village) from their farm in Springwells Township (now part of Dearborn, Michigan)—traveling about 20 miles and waiting to have the sheared wool from his father’s sheep run through the carding machine. There it would be combed, straightened, and shaped into loose fluffy rovings, ready for spinning. The Ford family raised a modest number of sheep (according to the 1880 Agricultural Census, the family raised 13 sheep that year), so they likely brought the rovings back to spin at home, probably for knitting.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

farm animals, manufacturing, making, home life, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Donna R. Braden, agriculture

#InnovationNation: Agriculture & Environment

cars, Greenfield Village buildings, manufacturing, farms and farming, Greenfield Village, farm animals, farming equipment, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, agriculture

Until We Meet Again

First of the 2020 crop of Firestone Farm Merino lambs: twins born April 11. A ram and ewe are showing a few of the prized wrinkles.

As I begin my second full year as director of Greenfield Village, I was truly looking forward to welcoming everyone back for our 91st season and sharing the exciting things happening in the village. Instead, as we all face a new reality and a new normal, I would like to share how, even as we have paused so much of our own day-to-day routines, work continues in Greenfield Village.

As we entered the second week of March, signs of spring were everywhere, and the anticipation, along with the preparations for the annual opening of Greenfield Village, were picking up pace. The Greenfield Village team was looking forward to a challenging but exciting year, with a calendar full of exciting new projects.

It's not only about the new stuff, though. We all looked forward to our tried-and-true favorites coming back to life for another season: Firestone Farm, Daggett Farm, Menlo Park, Liberty Craftworks and the calendar of special events, to name a few. Each of these has a special place in our hearts and offers its own opportunities for new learning and perspectives. Despite all our hope and anticipation for this coming year, however, our plans took a different direction.

As our campus closed this past March, it had long been obvious that the year was going to be very different than the one we had planned. The Henry Ford's leadership quickly assessed the daily operations in order to narrow down to essential functions. For most of Greenfield Village, this meant keeping what had been closed for the season closed. Liberty Craftworks, which typically continues to produce glass, pottery and textile items through the winter months, was closed, and the glass furnaces were emptied and shut down. This left the most basic and essential work of caring for the village animals to continue.

Here I am with the Percheron horse Tom at Firestone Barn, summer 1985.

As proud as I am to be director of Greenfield Village, I am equally proud, if not more so, to be part of a small team of people providing daily care for its animals. This work has brought me full circle to my roots as a member of the first generations of Firestone Farmers 35 years ago. It’s amazing to me how quickly the sights, sounds and smells surrounding me in the Firestone Barn bring back the routines I knew so well so long ago. I am also proud of my colleagues who work along with me to continue these important tasks.

The pandemic has not stopped the flow of the seasons and daily life at Firestone Farm. Our team made the decision very soon after we closed to move the group of expecting Merino ewes off-site to a location where they could have around-the-clock care and monitoring as they approached lambing time in early April. This group of nearly 20 is now under the watchful eye of Master Farmer Steve Opp in Stockbridge, Michigan, about 60 miles away.

Meet the newest members of the Firestone Farm family.

After their move, the ewes were given time to settle into their new temporary home. They were then sheared in preparation for lambing, as is our practice this time of year. I am very pleased to report that the first lambs were born Easter weekend, Saturday, April 11. All are doing well, and several more lambs are expected over the next few weeks. Once the lambs are old enough to safely travel, and we have a better understanding of our operating schedule looking ahead, they will all return to Firestone Farm, having the distinction of being the first group of Firestone lambs not born in the Firestone Barn in 35 years.

The last of the Firestone Farm sheep getting sheared in the Firestone Barn.

The wethers, rams and yearling ewes that remain at Firestone Farm were also recently sheared and are ready for the warm weather. One of the wethers sheared out at 18 pounds of wool, which will eventually be processed into a variety of products that are sold in our stores.

Continue Reading

farms and farming, farm animals, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Jim Johnson, Greenfield Village, COVID 19 impact

A Closer Look: The Champion Egg Case Maker

After the Civil War, urban populations swelled. Until this time, farm families had kept flocks of chickens and gathered eggs for their own consumption, but with increased demand for eggs in growing cities, egg farming grew into a specialized industry. Some families expanded egg production at existing farms, and other entrepreneurs established large-scale egg farms near cities and on railroad lines. Networks developed for shipping eggs from farms to buyers – whether wholesalers, retailers, or individuals operating eating establishments.

While farmers who sold eggs directly to customers carried their products to market in different ways, sellers who shipped eggs to buyers standardized their containers to ensure a consistent product. The standard egg case became an essential and enduring part of the egg industry.

Egg producers initially used different sizes and types of containers to pack eggs for market. As the egg industry developed, standardized cases that held thirty dozen (360) eggs – like this version first patented by J.L. and G.W. Stevens in 1867 – became the norm. THF277733

Egg distributors settled on a lightweight wooden box to hold 30 dozen (360) eggs. The standard case had two compartments that held a total of twelve “flats” – pressed paper trays that held 30 eggs each and provided padding between layers. Retailers who purchased wholesale cases of eggs typically repackaged them for sale by the dozen (though customers interested in larger quantities could – and still can – buy flats of 30 eggs).

The standard egg case held 12 of these pressed paper trays, or “flats,” which held 30 eggs each. THF169534

Some egg shippers purchased premade egg cases from dedicated manufacturers. Others made their own. Enter James K. Ashley, who invented a machine to help people build egg cases to standard specifications. Ashley, a Civil War veteran, first patented his egg case maker in 1896 and received additional patents for improvements to the machine in 1902 and 1925.

James K. Ashley’s patented Champion Egg Case Maker expedited the assembly of standard egg cases.

Ashley’s machine, which he marketed as the Champion Egg Case Maker, featured three vises, which held two of the sides and the interior divider of the egg case steady. Using a treadle, the operator could rotate them, making it easy to nail together the remaining sides, bottom, and top to complete a standard egg case, ready to be stenciled with the seller’s name and filled with flats of eggs for shipment.

Ashley’s first customer was William Frederick Priebe, who, along with his brother-in-law Fred Simater, operated one of the country’s largest poultry and egg shipping businesses. As James Ashley continued to manufacture his egg case machines (first in Illinois, then in Kentucky) in the early twentieth century, William Priebe found rising success as the big business of egg shipping grew ever bigger.

One of James K. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Makers, now in the collections of The Henry Ford. THF169525

James Ashley received some acclaim for his invention. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Maker earned a medal (and, reputedly, the high praise of judges) at the St. Louis World's Exposition in 1904. And in 1908, The Egg Reporter – an egg trade publication that Ashley advertised in for more than a decade – described him as “the pioneer in the egg case machine business” (“Pioneer in His Line,” The Egg Reporter, Vol. 14, No. 6, p 77).

While the machine in the The Henry Ford’s collection no longer manufactures egg cases, it still has purpose – as a keeper of personal stories and a reminder of the complex ways agricultural systems respond to changes in where we live and what we eat.

Additional Readings:

- Henry’s Assembly Line: Make, Build, Engineer

- Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882

- The Wool Carding Machine

farming equipment, manufacturing, food, farms and farming, farm animals, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture