Posts Tagged george washington carver

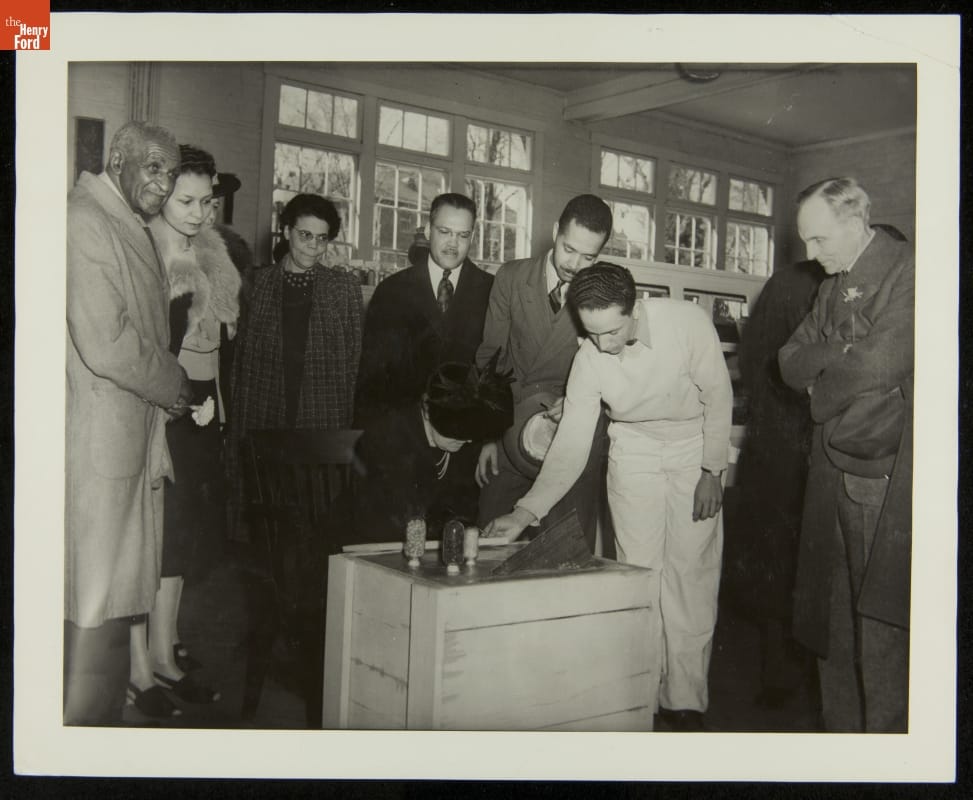

Austin W. Curtis (left) assisting George Washington Carver (right) during a lecture at Starr Commonwealth for Boys School, Albion, Michigan, 1939. / THF213740

Austin W. Curtis (left) assisting George Washington Carver (right) during a lecture at Starr Commonwealth for Boys School, Albion, Michigan, 1939. / THF213740

Austin Wingate Curtis, Jr. (1911–2004) assisted George Washington Carver for nearly eight years (1935–1943). Biographers often measure Curtis by his association with Carver, the renowned Black scientist who spent his career at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University). Mark D. Hersey described Curtis as “Carver’s best-known assistant” in his 2011 biography of Carver, titled My Work Is That of Conservation (page 181).

Curtis might be Carver’s best-known assistant, but his association with Carver accounted for only eight of Curtis’s ninety-three years. After Carver’s death, Curtis remained at Tuskegee until 1944 when the board decided not to retain him. He relocated to Detroit, Michigan, launched a business that emphasized his association with Carver, raised a family, pursued various business ventures, ran for political office, and added to The Henry Ford’s collection documenting George W. Carver. The following provides a fuller picture of Austin Curtis.

The Early Years

Austin Wingate Curtis, Jr., was born July 28, 1911, in Kanawha County, West Virginia. Support for education ran deep in his family. His maternal great-grandfather, Samuel I. Cabell (1802–1865), owned the land that the state acquired to build the West Virginia Colored Institute (which became the West Virginia Collegiate Institute in the early 20th century and is now West Virginia State University). This was one of 17 Black land-grant institutions that the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1890 partially funded by 1920.

Austin Curtis’s mother, Dora Throne Brown (1875–1960), enrolled at West Virginia Colored Institute to train as a teacher. His father, Austin Wingate Curtis, Sr. (1872–1950), graduated in 1899 from the Black land-grant college in North Carolina (now North Carolina A&T State University at Greensboro). He began teaching agriculture at the West Virginia Institute that same year. He and Dora Brown married in 1905. They had two children, Alice Cabell Curtis (1908–2000) and Austin Wingate Curtis, Jr.

The Henry Ford has no photographs of the Curtis family, but the Library of Congress does. These provide a rare glimpse into rural Black culture during the period when more Black families owned land than at any other time in U.S. history (approximately 25 percent of Black farmers nationwide identified as landowners in the 1920 census).

A support system operated out of the Black land-grant colleges that linked farm families to information shared by experts trained in agriculture and domestic science. Tuskegee Institute’s moveable school drew a lot of attention from the media, and might be the best-known example of the ways that experts reached farmers across the countryside, but it was one approach among many.

Training often focused on livestock, especially pigs.

Austin Curtis, Sr., agricultural expert, instructs George Cox, a 13-year-old 4-H club member and son of a “renter” or tenant farmer, in pork nutrition near the West Virginia Collegiate Institute (near Charleston). / Photograph by Lewis W. Hine, on assignment for the National Child Labor Committee, October 10, 1921, from the Library of Congress.

Austin Curtis, Sr., conveyed the latest information about swine management to young people organized through local 4-H clubs. His son, Austin Curtis, Jr., participated in these efforts, raising a sow and tending her piglets as part of his pig project. This work helped stabilize farm incomes, a critical step in farm solvency for owners and tenant farm families. Bulletins like “How to Raise Pigs With Little Money” (1915), by George Washington Carver, facilitated this type of instruction.

Austin Curtis, Jr., 10 years old, participated in the pig clubs that his father, Director of Agriculture at West Virginia Collegiate Institute, helped organize. / Photograph by Lewis W. Hine, on assignment for the National Child Labor Committee, October 10, 1921, from the Library of Congress.

Austin Curtis, Jr., grew up immersed in Black land-grant networks, but alternatives existed. Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950), who held the position of Dean at the West Virginia Collegiate Institute between 1920 and 1922, proved that working in a West Virginia coal mine could lead to higher education. Woodson became the second Black man to earn a doctoral degree at Harvard University in 1912. He founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) in 1915 and launched the Journal of Negro History (now the Journal of African American History) in 1916 to encourage Black and white scholars to study Black history. Woodson also launched Negro History Week (now Black History Month) in 1926 to facilitate exchange.

Curtis’s father took summer classes at Cornell University to remain current in livestock management. Ultimately, Curtis, Jr., selected Cornell University, too, and studied plant physiology there, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1932. After graduation he returned to West Virginia and worked in a greenhouse, for a landscaping business, and drove a cab, before accepting a teaching position at his father’s alma mater in Greensboro, North Carolina.

In 1935 Curtis, Jr., accepted a fellowship funded by the General Education Board to serve as George Washington Carver’s research assistant at Tuskegee Institute. He began work at Tuskegee in September 1935.

Tuskegee Institute football pennant, 1920–1950. / THF157606

Family Matters

As Austin Curtis, Jr., built his career as a chemist, he also pursued a personal life. While teaching at the A&T College in Greensboro, he met Belle Channing Tobias, head of biology at Bennett College for Women (now Bennett College). She was the daughter of Mary Pritchard and Channing Heggie Tobias, a minister, civil rights activist, and director of YMCA work among Black residents in New York City. The media reported on the Curtis-Tobias wedding as a society event held in St. Paul’s Chapel, Columbia University, New York City, on June 15, 1936.

Postcard, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, 1930–1945. / Wikimedia Commons

Described as “brilliant,” Tobias earned her bachelor’s degree at Barnard College, graduating Phi Beta Kappa. She studied zoology at Wellesley College and conducted research at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. She was on leave from her faculty position at Bennett College and enrolled in the doctoral program at Columbia University at the time of her marriage.

Austin and Belle Curtis planned to honeymoon in West Virginia and then drive to Tuskegee Institute. Tragically, Belle fell ill from kidney disease during the honeymoon, and died at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City on October 7, 1936, just four months after the wedding (“Death Claims Belle Tobias,” New York Amsterdam News, October 10, 1936).

Work with Carver consumed Curtis after his wife’s death. His loss coincided with the growth of chemurgy, a branch of chemistry dedicated to industrial uses of plant byproducts. Correspondence between Henry Ford and George W. Carver ensured that Carver (and Curtis) were well informed about industrialist Ford’s investment in chemurgy. This drew increased attention to their work.

Somehow Curtis found time to court Tuskegee Institute art teacher Oreta Adams (1905–1991). Her parents, King P. Adams (1870–1944) and Sarah Bibb Adams (1870–1944), lived in Lawrence, Kansas. Her father was a janitor at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, and a member of the Black Masons, an organization which supported leadership and service within Black neighborhoods. Curtis and Adams married at Adams’s parents’ home, 318 Locust Street in Lawrence, on August 3, 1938.

The Chicago Defender reported that the couple spent a week in Lawrence, then traveled through Illinois on their way back to Tuskegee, where they both resumed their posts. Their Illinois destination, in addition to Chicago, was the University of Illinois. This land-grant university was noted for soybean research. It had soybean experts on faculty and staff, and research in soybean genetics and in soybean uses ongoing. (“Kansas Girl Marries Aide to Dr. Carver,” Chicago Defender, August 13, 1938). Curtis also spent one summer working in the Soybean Laboratory in Greenfield Village. He stayed with his uncle, Cornelius S. Curtis, who lived in Detroit (Curtis Oral Interview, July 23, 1979, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, page 31–32).

Curtis: Carver’s Support System

Curtis provided a lot of support to Carver over the years, including driving him to public engagements.

Between the death of Belle and his marriage to Oreta, Curtis drove Carver to Dearborn, Michigan. They participated in the third Dearborn Conference on Industry held in 1937. Curtis presented information on Carver’s products, including peanut and sweet potato extracts, and on his own chemical work, including isolating pigments from wild plants and devising uses for oil extracted from magnolias (“Tuskegee Chemist in Address at Detroit,” Chicago Defender, June 5, 1937).

Curtis and Carver also toured Greenfield Village. Carver described it as “one of the greatest educational projects I have ever seen” in a thank-you letter to Henry Ford, written on Dearborn Inn letterhead. One highlight was their interaction with Francis Jehl, a research assistant to Thomas Edison and an advisor on the lab reconstruction in Greenfield Village. On the drive back to Tuskegee, they stopped to visit the Curtis family in Institute, West Virginia (“Tuskegee Chemist in Address at Detroit,” Chicago Defender, June 5, 1937).

Left to right: Austin W. Curtis, George Washington Carver, William Simonds, and Francis Jehl at Menlo Park Laboratory, Greenfield Village, 1937. / THF213745

One of the most important services Curtis provided involved promoting Carver’s work at every opportunity. Sometimes this took the form of public speaking. During the ceremony that recognized Carver’s 40 years of service to Tuskegee Institute, Curtis delivered a ten-minute overview of Carver’s life and work, broadcast on WJDX radio (“To Unveil Bust of Dr. Carver June 2,” Chicago Defender, May 22, 1937).

Curtis claimed to have started the Carver Museum (now part of the National Park Service’s Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site) at Tuskegee. Installed on the third floor of the Institute’s library building initially, it featured Carver’s paintings, needlework, extracts, and other plant byproducts (Curtis Oral Interview, page 27). Carver toured Henry Ford through the museum during Ford’s first of three visits to the Tuskegee campus in March 1938. The group inspected peanut oil, which Carver promoted as part of massage therapy for infantile paralysis (“Ford Visits Tuskegee; Talks on Science with Dr. Carver,” Chicago Defender, March 19, 1938).

The museum received more attention as the relationship between Carver and Ford grew. In March 1941, during Ford’s third trip to Tuskegee, the group dedicated a new George Washington Carver Museum. Curtis helped a Tuskegee student insert soy-based plastic composite material into concrete blocks as part of the ceremonies.

George Washington Carver, Clara Ford, and Henry Ford at dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, March 1941. / THF213788

Cultivating Carver’s legacy took Curtis and Carver on the road regularly. Trips often consisted of multiple speaking engagements with Curtis assisting. Audiences ranged from children to peers equally invested in chemurgy research. The photo at the top of this post shows one of those appearances.

Curtis was never far from Carver, as photographs of Carver’s entourage attest. Curtis drove Carver, assisted him as he became more infirm, and looked out for his well-being during two events hosted by Henry Ford. The first, in March 1940, focused on the dedication of the George Washington Carver Elementary School in Richmond Hill, Georgia. Then, in July 1942, the two traveled to Henry Ford’s Edison Institute (now The Henry Ford) in Dearborn, Michigan, for the dedication of the Carver Nutrition Laboratory and the Carver Memorial (now the George Washington Carver Cabin) in Greenfield Village.

Curtis urged Carver to leave a legacy. This took the form of an endowment to carry on Carver’s work. The media reported on formation of the George W. Carver Foundation during the 15th Negro History Week celebration, which occurred February 11–17, 1940 (“This Day in History,” Chicago Tribune, February 14, 1946).

A gentleman’s agreement of a sort apparently existed between Curtis and Carver. Curtis fully expected to continue Carver’s work, and he informed Henry Ford of that fact in a January 1943 letter. Tuskegee president F.D. Patterson had other ideas. The two disagreed over royalties specified in a publishing contract, and the Tuskegee board terminated Curtis in April 1944 (“Aide to Dr. Carver Eased Out at Tuskegee,” Atlanta Daily World, April 22, 1944). By that time, the book, George Washington Carver: An American Biography (Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1943), was selling well, and Carver’s contract with the publisher had guaranteed Curtis a percentage of the royalties.

Curtis after Tuskegee

Curtis pivoted rapidly after his firing. He had to. His wife, Oreta, had just given birth to their first child, Kyra. He had relatives in Detroit, and his association with Henry Ford and awareness of chemurgy networks likely drew him to the city. He launched A.W. Curtis Laboratories to manufacture health care products and cooking oil derived from Carver’s research. The Curtises’ second child, daughter Synka, was born in Detroit in 1946.

Curtis Rubbing Oil, circa 1987, for fast relief of minor aches and pains of arthritis and rheumatism. The back of the bottle describes best uses and warnings for children. The active ingredients are listed as "Peanut Oil, Methyl Salicylate.” / THF170781

Product marketing stressed Curtis’ connection to Carver. A. W. Curtis Laboratories held the grand opening of its sales office on National Carver Day, January 4, 1947 (he had died on January 5, 1943). The Detroit Tribune advertisement included a photograph of Carver and Curtis at work together in their Tuskegee laboratory and the oft-quoted phrase attributed to Carver: “through [Curtis] I see an Extension of my Work.” Curtis also arranged for Rackham Holt, author of George Washington Carver: An American Biography, to be available to sign books. To sweeten the prospects of a sales-office visit, Curtis offered three prizes for ticket holders, including one-half gallon of “our Peanut Cooking Oil” (January 4, 1947, page 8).

Austin Curtis, Jr., remained in touch with The Henry Ford, off and on, during his years in Detroit. He conducted an interview with Doug Bakken and Dave Click in 1979. Curtis visited Greenfield Village on August 17, 1982, to reminisce about the dedication ceremony that had occurred 40 years before.

Austin W. Curtis visiting the George Washington Carver Cabin in Greenfield Village, August 17, 1982. / THF287706

Curtis helped expand The Henry Ford’s collection of Carver items by offering, in 1997, a microscope and typewriter used by Carver at Tuskegee. By then, Curtis was also reducing his involvement in his business. The Reverend Bennie L. Thayer, chairman of the board for Natural Health Options, Inc. acquired A.W. Curtis Laboratories in 1999, and the next year, Dr. E. Faye Williams purchased the company and manufacturing rights. Curtis died in Culver City, California, on November 5, 2004.

Notes about Sources

Much remains to learn about Curtis’s life in Detroit. Consult the Austin W. Curtis Papers, 1896–1971, at the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, for more.

Newspaper articles mentioned Curtis in coverage of Carver through the years they worked together (and beyond). Newspaper accounts of Curtis, Jr., provided leads to follow. These appeared in the Chicago Defender (Arnold De Mille, January 29, 1955) and the New York Amsterdam News (Julian Jingles, February 24, 1996, and Herb Boyd, October 9, 2014).

Ancestry.com confirmed genealogical details. Newspapers articles affirmed events (as referenced throughout the text).

Secondary sources documenting Curtis, Sr., and Jr. and West Virginia history include:

Askins, John. “Austin W. Curtis, Jr.: He Lives in Shadow of G. W. Carver,” Biography News (May/June 1975), pg. 511.

“Austin Wingate Curtis [1872-1950],” History of the American Negro. West Virginia Edition. A. B. Caldwell, editor. Vol. 7. Atlanta, Georgia: A. B. Caldwell Publishing Company, 1923.

Moon, Elaine Latzman. “Austin W. Curtis, [Jr.,] D.S.C.” in Untold Tales, Unsung Heroes: An Oral History of Detroit’s African American Community, 1918–1967. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994, pp. 253-255.

Morgan, B.S., and J.F. Cork. “Beginning of West Virginia State University.” History of Education in West Virginia. Charleston: Moses W. Donnally, 1893, pp. 189-94.

Turner, Ruby M. “The Life and Times of Dr. Austin Wingate Curtis, Jr.,” Simpson College Archives, Indianola, Iowa.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Saige Jedele and Sophia Kloc shared comments that improved this blog.

entrepreneurship, agriculture, Michigan, Detroit, education, by Debra A. Reid, George Washington Carver, African American history

Cast in Plaster: Isaac Hathaway and Sculpture as Black Biography

Black sculptor Isaac Scott Hathaway (1872–1967) took issue with inadequate recognition of Black achievement. He dedicated his career to creating and marketing affordable plaster busts and other commemorative sculpture, literally putting Black activists, educators, ministers, and dozens of other individuals on a pedestal. These stood in stark contrast to lawn jockeys and other statuary that emphasized caricatures and stereotypes.

Plaster Plaque of George Washington Carver (1864?–1943) Cast by Isaac Scott Hathaway, 1945. / THF152082

Hathaway remembered visiting a Midwestern museum when he was nine years old (around 1881), with his father, Robert Elijah Hathaway (1842–1923). The young Hathaway wondered why museums did not include statues of Black people. His father explained that white people modeled their own, and that if Black Americans wanted to see sculptures of Black Americans, “we will have to grow our own sculptors.”

This museum visit changed Hathaway’s life, as he recalled in a 1939 Federal Writers’ Project interview and in a 1958 article in the Negro History Bulletin. He studied art during the era of the New Negro, a movement of the 1890s to 1910s that emphasized African and Black American contributions to the arts, literature, and culture. He taught school, created sculpture, and distributed his plaster casts through the Afro Art Company, which he launched after he moved to Washington, D.C., in 1907.

Hathaway moved when opportunities to further ceramics education arose. He relocated to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, by 1915 to launch ceramics education at the Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff). He moved his company, renamed the Isaac Hathaway Art Company, to Pine Bluff at the same time. In 1937, he joined the faculty at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama, to introduce a ceramics curriculum there. In 1947, he moved to Montgomery, Alabama, to direct ceramics instruction at Alabama State College (now Alabama State University).

Plaster Cast of George Washington Carver's Hand, 1943. / THF34092

The Henry Ford has two of Hathaway’s plaster casts. Hathaway gave them to Henry Ford in December 1945, explaining that he wanted Ford to have the small plaque (shown at the beginning of this post) and “a cast … made from the hand of the late Dr. George Washington Carver” (shown above). The plaque was one of three types of casts of Carver that Hathaway made. The others included a small bust (around one foot tall) and a heroic bust, visible in this photograph of the artist at work (courtesy of the Tuskegee University Archives).

Carver’s hands attracted a lot of attention, long and strong and well-worn after years of physical labor. Based on Hathaway’s description, it appears that he made the cast of Carver’s hand after Carver died on January 5, 1943. Hathaway instructed students in techniques he used. Photographs show him instructing students in creating molds of their hands at Alabama Polytechnic University (now Auburn University) around 1947.

Hathaway’s reputation earned him a commission in 1946 to design the Booker T. Washington Memorial Half Dollar. This was the first coin designed by a Black American for the U.S. Mint, and the first coin minted that featured a Black American. You can read more about this in “Coining Liberty: The Challenge of Commemorating Black History.”

Hathaway’s plaster casts remind us of the importance of acknowledging Black accomplishments. Others followed his examples.

Benjamin Akines (c1904–?), a bricklayer and brick mason living in Jackson, Mississippi, knew of Henry Ford’s interest in and respect for Carver’s work. Akines gave Ford a bust of the Black scientist in 1941, four years before Hathaway sent his two casts to Ford.

Bust of George Washington Carver, circa 1941. / THF170783

Akines sent the plaster bust and a letter directly to Henry Ford: “Enclosed you will find a token (in the form of a bust) of one of whom I am told you esteem very highly … I trust this will mean a moment of happiness to you.” Akines claimed that he “was divinely inspired to model,” though he worked as a bricklayer. The back of the bust represents the work of a bricklayer, sculpted with a cut stone foundation with a laid brick pier. This brickwork was his signature, as Akines included bricks in other creative works. On November 10, 1931, he received a patent for an ornamental clock case in the form of a brick façade and sides (Patent Des. 85,507).

Bust of George Washington Carver, circa 1941, Cast by Benjamin Akines. / THF170784

Eager to share his efforts, Akines communicated his news to the Chicago Defender, the Black newspaper in the then second-largest U.S. city, Chicago, Illinois. It reported that “Akines, a bricklayer who indulges in sculpturing as a hobby,” gave Ford a plaster cast of Carver, and that Ford’s secretary and Carver himself acknowledged his generosity (“Bricklayer-Sculpturor [sic] is Lauded for Bust of Carver,” July 12, 1941).

It is difficult to know whether others who cast busts of Carver influenced Akines’ approach. For example, German-born Steffen Thomas (1906–1990) sculpted a clay model of Carver during a 1936 visit to Tuskegee. This was the model from which he cast the sculpture recognizing Carver’s 40 years of service to Tuskegee. The gift received media coverage at the time Carver received it in 1937 and appeared prominently during the dedication of the Carver Museum in 1941, given its location on a plinth outside the museum.

George Washington Carver and Austin W. Curtis, Jr., at Tuskegee Institute with Sculpture by Steffen Thomas, circa 1938. / THF213732

These last two examples indicate more recent commemorations of Black historical figures. One represents a respectful but commercial venture, and the other an exceptional recognition.

Commemorative Bust of Rosa Parks (1913–2005), designed by Sarah’s Attic, Inc., 1995. / THF98391

A popular Michigan-based figurine manufacturer, Sarah’s Attic., Inc., released a limited-edition bust of rights activist Rosa Parks in 1995. Cast of synthetic resin and hand-painted, it was one of four “Faces of Courage” in the Black Heritage Collection. The others featured abolitionist Harriet Tubman, a Buffalo Soldier, and a Tuskegee Airman. The Rosa Parks bust was one of 9,898 made and distributed through a commercial contract, with Sarah’s Attic holding the copyright and Rosa Parks holding the license.

Commemorative Bust of Detroit Lions Tight End Charlie Sanders (1946–2015), 2007. / THF165543

This cast metal bust of the Detroit Lions’ legendary tight end Charlie Sanders exists because of his election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The Hall commissioned Tuck Langland, an artist and retired university educator, to cast Sanders. Langland first created a bust out of clay based on photographs and a visit with Sanders. That clay statue became the model for the cast bronze bust displayed in the Hall of Fame Gallery in Canton, Ohio, and the copy presented to Sanders (and later donated to The Henry Ford).

So many variables exist in the business of commemoration.

When Isaac Scott Hathaway created respectful sculptures of Black Americans, he challenged white exceptionalism. Who decided who received recognition? Hathaway. What criteria informed his decisions? He selected subjects he respected, but as an educator, he selected people with lessons to teach, and as a businessman, he selected subjects that would sell. Disagreements over selections can derail seemingly straightforward acknowledgment.

What form should the recognition take? Hathaway mass-produced inexpensive plaster casts. Others create one-of-a-kind sculpture or mass-produce limited-edition items. Other recognition in the form of a historical marker or a street sign can draw attention to places of significance and the people who lived there.

Recognition of Black accomplishments remains important—in fact, critical—to understanding the human experience.

Sources

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “The New Negro and the Black Image: From Booker T. Washington to Alain Locke.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center.

“The Hathaway Family: A Journey from Slavery to Civil Rights,” a paper compiled by scholars Yvonne Giles, Reinette Jones, Henri Linton, Brian McDade, Quantia "Key" M. Fletcher, and Mark Wilson, based in materials at these institutions: Alabama State University, Montgomery, Alabama; Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama; the Isaac Scott Hathaway Museum, Lexington, Kentucky; the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, Little Rock, Arkansas; Tuskegee University Archives, Tuskegee, Alabama; the University Museum and Cultural Center, University of Arkansas Pine Bluff, Pine Bluff, Arkansas. (n.d.).

“Isaac Scott Hathaway,” a product of the Appalachian Teaching Project, Auburn University, and the Tuskegee Human and Civil Rights Multicultural Center (2012).

"Isaac Scott Hathaway: Artist and Teacher," Negro History Bulletin, vol. 21, no. 4 (January 1958), pp. 74, 78-81.

Perry, Rhussus L. Federal Writers’ Project Interview of Isaac Hathaway. February 2, 1939. Folder 60, Coll. 03709, Federal Writers' Project papers, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Register, Heather. “Isaac Scott Hathaway (1872-1967).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

Zinkula, Jacob. “South Bend Artist Busts His Way into Football Hall of Fame.” South Bend Tribune. 13 July 2015.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford, and sends appreciation to Saige Jedele and Sophia Kloc for comments that strengthened this post.

teachers and teaching, education, making, George Washington Carver, Rosa Parks, by Debra A. Reid, art, African American history

This 1885 Harper's Weekly cover celebrated the freedom of enslaved African Americans 22 years after emancipation with the text, "Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants." / THF11676

Liberty stands as one of the ideals that inspired the United States from its beginning, as the following quotes from founding documents indicate:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” –Declaration of Independence, 1776

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, ensure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, and promote the general Welfare, and ensure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” –Constitution of the United States, 1788

National aspirations for liberty resonated, but “liberty” for some trapped others in servitude. United States expansion came at the highest cost to indigenous and enslaved individuals. For them, liberty rang hollow.

The Union victory in the Civil War affirmed the nation’s authority to abolish slavery, expand citizenship and civil rights protection, and grant universal manhood suffrage. The Fourteenth Amendment affirmed that “No state shall . . . deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the law.” Yet, newly freed Black Americans faced discrimination that deprived them of these unalienable rights.

Throughout this tumultuous history, the word “liberty” has been on all U.S. coins. The Coinage Act of 1792 established the U.S. Mint and decreed that all coins include an “impression emblematic of liberty” and the word “liberty.” Thus, the lawful tender in the United States, from the start of our national currency, emphasized liberty—even as the nation built its economy on and around the enslavement of people of African origin and descent.

The United States marked its 170th anniversary in the year that the U.S. Mint first linked “liberty” to Black history. Congress authorized production of a 50-cent coin to “commemorate the life and perpetuate the ideals and teachings of Booker T. Washington,” about 30 years after Washington’s death, on August 7, 1946 (Public Law 610-79th Congress, Chapter 763-2D Session, H.R 6528 August 7, 1946). Washington, noted educator and advocate for economic independence and Black autonomy, built his reputation as he built a segregated public school in Tuskegee, Alabama, into an engine of Black economic development. The Tuskegee alumni networks enthusiastically sustained his ideals, including liberty achieved regardless of racism and separate-but-equal segregation.

Commemorative Half Dollar Coin Featuring Booker T. Washington, 1946. / THF170779

In addition to the word “liberty,” the coin’s reverse side summarized Washington’s evolution, from his birth as an enslaved person to his induction into the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in 1945.

Verso, Booker T. Washington Commemorative Half Dollar Coin, 1946, Produced in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The back of the coin featured the log structure memorialized as the Booker T. Washington Birthplace Memorial in Franklin County, Virginia, and the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, into which Washington was posthumously inducted in 1945, located in the Bronx, New York City. / THF170780

The Black sculptor who designed the coin, Isaac Scott Hathaway, summarized Washington’s life story on a trajectory from enslavement to recognition. Hathaway had pursued this work for most of his life, convinced that Black Americans warranted representation in classical forms—specifically on busts and bas-relief plaques—that rivaled those of gods and goddesses. He mass-produced plaster busts and plaques of more than 200 Black women and men for customers to purchase and display in homes, schools, and churches. He divided his time between memorializing Black individuals and teaching in Tuskegee Institute’s Department of Ceramics, which he founded. His connection to Tuskegee helped secure his appointment as the first Black artist to design a coin for the U.S. Mint in 1945.

George Washington Carver Plaque, 1945. Hathaway knew Carver, and he cast this small bas-relief plaster plaque out of respect for “this venerable man whose acquaintance and friendship I enjoyed for 40 years.” He donated this plaque, as well as a plaster cast of Carver’s hand, to The Henry Ford in December 1945. / THF152082

The commemorative half-dollar coin featuring Booker T. Washington remained in production between 1946 and 1951. Sales of the commemorative sets, however, fell short of expectations. The U.S. Congress amended the August 7, 1946, act, reauthorizing a redesigned coin that added Tuskegee Institute agricultural scientist George Washington Carver to the front, and a patriotic message on the back (Public Law 151-82d Congress, Chapter 408, 1st Session. H.R. 3176 September 21, 1951). The Mint again retained Hathaway to design this second coin. One and one-half million Washington coins were melted and recast into the new issue.

Commemorative Half Dollar Coin Featuring George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington, 1953. / THF152213

Reverse Side, Commemorative Half Dollar Coin Featuring George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington, 1953, Produced at Denver, Colorado. / THF152214

Proceeds from sales of both of these commemorative coins were ear-marked for completion of the only national monuments documenting Black history at the time—the Booker T. Washington Birthplace Memorial in Virginia and the George Washington Carver National Monument in Missouri. But sluggish sales did not generate the anticipated income for these two projects. When the amended act expired on August 7, 1954, the remaining million coins minted but not sold were melted and used for other coins. The practice of issuing commemorative coins for private initiatives—funding historic sites and memorials, in the case of these two coins—also ended with the expiration of the Washington commemorative coin act.

Continue Reading

Alabama, Washington DC, 1950s, 1940s, 20th century, 19th century, George Washington Carver, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Interior of Henry Ford’s Private Railroad Car, “Fair Lane,” June 22, 1921 / THF148015

Beginning in 1921, Henry and Clara Ford used their own railroad car, the Fair Lane, to travel in privacy. Clara Ford designed the interior in consultation with Sidney Houghton, an interior designer based in London. The interior guaranteed a comfortable trip for the Fords, their family, and others who accompanied them on more than 400 trips between 1921 and 1942.

The view out the railcar windows often featured the landscape between Dearborn, Michigan, and Richmond Hill, Georgia, located near Savannah. The Fords purchased more than 85,000 acres in the area, starting in 1925, remaking it into their southern retreat.

On at least three occasions, Henry Ford might have looked out that Fair Lane window, observing changes in the landscape between Richmond Hill and a siding (or short track near the main railroad tracks, where engines and cars can be parked when not in use) near Tuskegee, Alabama. Henry Ford took the railcar to the Tuskegee Institute in 1938, 1941, and 1942, and Clara accompanied Henry at least twice.

Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Tuskegee, Alabama, March 1938 / THF213839

Henry first met with George Washington Carver and Austin W. Curtis at Tuskegee on March 11, 1938. A small entourage accompanied him, including Ford’s personal secretary, Frank Campsall, and Wilbur M. Donaldson, a recent graduate of Ford’s school in Greenfield Village and student of engineering at Ford Motor Company.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford on the Tuskegee Institute Campus, 1938. / THF213773

Photographs show these men viewing exhibits in the Carver Museum, installed at the time on the third floor of the library building on the Tuskegee campus (though it would soon move).

Austin Curtis, George Washington Carver, Henry Ford, Wilbur Donaldson, and Frank Campsall Inspect Peanut Oil, Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF 213794

Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, Henry Ford, and George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF214101

Clara accompanied Henry on her first trip to Tuskegee Institute, in the comfort of the Fair Lane, in March 1941. Tuskegee president F.D. Patterson met them at the railway siding in Chehaw, Alabama, and drove them to Tuskegee. While Henry visited with Carver, Clara received a tour of the girls’ industrial building and the home economics department.

During this visit, the Fords helped dedicate the George W. Carver Museum, which had moved to a new space on campus. The relocated museum and the Carver laboratory both occupied the rehabilitated Laundry Building, next to Dorothy Hall, where Carver lived. A bust of Carver—sculpted by Steffen Thomas, installed on a pink marble slab, and dedicated in June 1937—stood outside this building.

The dedication included a ceremony that featured Clara and Henry Ford inscribing their names into a block of concrete seeded with plastic car parts. The Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s most influential Black newspapers, reported on the visit in its March 22, 1941, issue. That story itemized the car parts, all made from soybeans and soy fiber, that were incorporated—including a glove compartment door, distributor cap, gearshift knob, and horn button. These items symbolized an interest shared between Carver and Ford: seeking new uses for agricultural commodities.

Clara Ford, face obscured by her hat, inscribes her name in a block of concrete during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, March 1941, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama. Others in the photograph, left to right: George Washington Carver; Carrie J. Gleed, director of the Home Economics Department; Catherine Elizabeth Moton Patterson, daughter of Robert R. Moton (the second Tuskegee president) and wife of Frederick Douglass Patterson (the third Tuskegee president); Dr. Frederick Douglass Patterson; Austin W. Curtis, Jr.; an unidentified Tuskegee student who assisted with the ceremony; and Henry Ford. / THF213788

Henry Ford inscribing his name in a block of cement during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, Tuskegee Institute, March 1941 / THF213790

After the dedication, the Fords ate lunch in the dining room at Dorothy Hall, the building where Carver had his apartment, and toured the veterans’ hospital. They then returned to the Fair Lane railcar and headed for the main rail line in Atlanta for the rest of their journey north.

President Patterson directed a thank you letter to Henry Ford, dated March 14, 1941. In this letter, he commended Clara Ford for her “graciousness” and “her genuine interest in arts and crafts for women, particularly the weaving, [which] was a source of great encouragement to the members of that department.”

The last visit the Fords made to Tuskegee occurred in March 1942. The Fair Lane switched off at Chehaw, where Austin W. Curtis, Jr., met the Fords and drove them to Tuskegee via the grounds of the U.S. Veterans’ Hospital. Catherine Patterson and Clara Ford toured the Home Economics building and the work rooms where faculty taught women’s industries. Clara rode in the elevator that Henry had funded and had installed in Dorothy Hall in 1941, at a cost of $1,542.73, to ease Carver’s climb up the stairs to his apartment.

The Fords dined on a special luncheon menu featuring sandwiches with wild vegetable filling, prepared from one of Carver’s recipes. They topped the meal off with a layer cake made from powdered sweet potato, pecans, and peanuts that Carver prepared.

Tuskegee shared the Fords’ itinerary with Black newspapers, and the April 20, 1942, issue of Atlanta Daily World carried the news, “Carver Serves Ford New Food Products.” They concluded, in the tradition of social columns at the time, by describing what Henry and Clara Ford wore during the visit. “Mrs. Ford wore a black dress, black hat and gloves and a red cape with self-embroidery. Mr. Ford wore as usual an inconspicuously tailored business suit.”

Dr. Patterson wrote to Henry Ford on March 23, 1942, extending his regrets for not being at Tuskegee to greet the Fords. Patterson also reiterated thanks for “Mrs. Ford’s interest in Tuskegee Institute”—“The people in the School of Home Economics are always delighted and greatly encouraged with the interest she takes in the weaving and self-help project in the department.”

The Fords sold the Fair Lane in 1942. After many more miles on the rails with new owners over the next few decades, the Fair Lane came home to The Henry Ford. Extensive restoration returned its appearance to that envisioned by Clara Ford and implemented to ensure comfort for Henry and Clara and their traveling companions. Now the view from those windows features other artifacts on the floor of the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, in place of the varied landscapes, including those around the Tuskegee Institute, traveled by the Fords.

A view of the interior of Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car, the “Fair Lane,” constructed by the Pullman Company in 1921, restored by The Henry Ford to that era of elegance, and displayed in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF186264

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

1940s, 1930s, 20th century, Alabama, women's history, travel, railroads, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, George Washington Carver, Ford family, Fair Lane railcar, education, Clara Ford, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Peanut Roll Cake with Jelly Recipe

A Taste of History in Greenfield Village offers our visitors seasonal, locally sourced and historically minded recipes. Over the past year, our chefs have been developing some new recipes, directly drawn from the recipes of George Washington Carver and the ingredients that he used. You can learn more about the inspiration behind the new options both in A Taste of History and in Plum Market Kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in our blog post here, or try out some of the recipes for yourself—like this Peanut Roll Cake with Jelly.

Chef’s Notes

When we were reading through hundreds of George Washington’s Carver’s recipes, this one stood out. It’s a wow—a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for dessert! Chef Kasem Faraj, our resident Greenfield Village chef, spent hours making this one just perfect. We’ve had many variations of the PB&J in our lifetime, and this one takes the cake—just have fun and roll with it.

Recipe: Peanut Roll Cake with Jelly

Makes 1 Cake; Serves 8

Cake ingredients

4 each Eggs

7 oz Granulated Sugar

¾ tsp Baking Powder

½ tsp Salt

¼ tsp Baking Soda

4 ½ oz All Purpose Flour, Sifted

3 oz Butter, Melted

1 oz Vanilla Extract

Filling ingredients

1 ½ oz Granulated Peanuts

2 oz Smooth Peanut Butter

4 oz Raspberry Currant Jam/Jelly

Procedure

- Preheat oven to 350°F.

- Combine eggs, sugar, baking powder, baking soda, and salt in the bowl of an electric mixture (or use a hand mixer and bowl).

- Mix on medium-low speed until the sugar has dissolved and the mixture is smooth and runny, about 3 minutes.

- Increase the speed to medium and whip until the mixture is a play yellow and thick enough to fall from the whisk in ribbons.

- Increase the speed again to high and continue whipping until the mixture has roughly doubled in volume and is thick.

- Reduce speed to medium-low and add vanilla and melted butter in a steady stream.

- Add sifted flour all at once and mix just enough to incorporate the flour.

- Pour batter into a half sheet tray or 13” x 9” baking dish that has been lined with parchment paper and nonstick spray.

- Bake for 8-10 minutes. Cake is done when the cake is puffed, lightly brown from edge to edge, and slightly firm.

- While cake is still warm, place on a linen towel and roll tightly. Allow cake to cool while rolled to shape and keep from cracking when filled and rolled.

- Once cake has cooled, unroll cake, and cover the inside of the roll with peanut butter, jelly, and granulated peanuts.

- Re-roll the cake and allow to sit with the seam on the bottom.

- Glaze cake with a simple icing and top with additional granulated peanuts if desired.

Eric Schilbe is Executive Sous Chef at The Henry Ford.

making, George Washington Carver, by Eric Schilbe, restaurants, Greenfield Village, food, recipes

Collard Greens with Smoked Turkey Recipe

A Taste of History in Greenfield Village offers our visitors seasonal, locally sourced and historically minded recipes. Over the past year, our chefs have been developing some new recipes, directly drawn from the recipes of George Washington Carver and the ingredients that he used. You can learn more about the inspiration behind the new options both in A Taste of History and in Plum Market Kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in our blog post here, or try out some of the recipes for yourself—like these Collard Greens with Smoked Turkey.

Chef’s Notes

What is Southern cooking without greens? There are lots of different ways to go, and almost no way to go wrong. Just be sure to cook the greens long enough, and don’t add any extra salt until done.

We chose to add smoked turkey to this dish to build truly rich flavors into something very simple. If you don’t have a smoker, smoked turkey wings or legs are readily available, fresh or frozen, at most local grocers. Or you can make this dish vegan by omitting the turkey and smoking the onions before adding—or simply cook it over a campfire to achieve a rich, smoky flavor.

Recipe: Collard Greens with Smoked Turkey

Makes 8 Portions

Ingredients

2 lb Fresh Collard Greens

8 oz White Onion

8 cloves Fresh Garlic

8 oz Smoked Turkey Wing Meat

1 oz Cider Vinegar

4 C Vegetable Stock/Broth

To taste Salt and Pepper

Procedure

- Dice onions and sauté in a pot until translucent.

- Mince garlic and add to pot along with turkey wings.

- Deglaze pan with cider vinegar, then add in chopped collard greens and vegetable stock.

- Simmer on low until greens are tender and all liquid has been absorbed, approximately 1 ½ hours.

- Season with salt and pepper as needed.

Eric Schilbe is Executive Sous Chef at The Henry Ford.

restaurants, Greenfield Village, food, George Washington Carver, by Eric Schilbe, making, recipes

Sweet Potato Hash Recipe

A Taste of History in Greenfield Village offers our visitors seasonal, locally sourced and historically minded recipes. Over the past year, our chefs have been developing some new recipes, directly drawn from the recipes of George Washington Carver and the ingredients that he used. You can learn more about the inspiration behind the new options both in A Taste of History and in Plum Market Kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in our blog post here, or try out some of the recipes for yourself—like this Sweet Potato Hash.

Chef’s Notes

This hash covers so many of the vegetables Carver used, all in one. This dish is bound to make a big impact on your table, as simple ingredients come together to create this wonderful dish. Follow the cooking directions carefully and the textures and flavors will all be distinct until they meld together on the plate.

You can cook all the ingredients separately and chill until you are ready to eat, then simply sauté everything together in a hot pan—that is what we chefs would do!

Recipe: Sweet Potato Hash

Makes 8 Portions

Ingredients

1 ½ lb Sweet Potatoes

¼ C Melted Butter

4 oz Red Onion

4 oz Celery

4 oz Red Bell Pepper

2 cloves Fresh Garlic

1 tsp Fresh Parsley

To taste Salt and Pepper

¼ cup Granulated Peanuts

Procedure

- Peel and dice sweet potatoes.

- Roast sweet potatoes in 350°F oven until tender.

- Dice onions, celery, and red pepper, keeping them all separate.

- Melt butter in a large pan and sauté onions until translucent.

- Add celery, minced garlic, and red pepper and sauté for an additional 3 minutes.

- Add peanuts and sweet potatoes and cook for another 3-5 minutes, making sure to stir constantly.

- Season with salt and pepper, and garnish with fresh chopped parsley.

Eric Schilbe is Executive Sous Chef at The Henry Ford.

George Washington Carver, food, making, by Eric Schilbe, Greenfield Village, restaurants, recipes

Brined and Roasted Chicken Recipe

A Taste of History in Greenfield Village offers our visitors seasonal, locally sourced and historically minded recipes. Over the past year, our chefs have been developing some new recipes, directly drawn from the recipes of George Washington Carver and the ingredients that he used. You can learn more about the inspiration behind the new options both in A Taste of History and in Plum Market Kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in our blog post here, or try out some of the recipes for yourself—like this Brined and Roasted Chicken.

Chef’s Notes

Running out of time? This recipe takes plenty of patience and is well worth it, but if you need something quick, you can roast the chicken with salt and pepper for a few minutes, then brush it with melted butter, apple cider vinegar, and pure maple syrup. Continue roasting, brushing with the mixture an additional two or three times, until the chicken is fully cooked.

We also recommend serving it alongside the sauce (link below). There are many other sauces that Carver has recipes for in his published papers, but we chose the green Tomato Chili Sauce because it uniquely balances the sweet maple flavor of the chicken with just enough spice to make it dance on your palette. You can make the sauce ahead of time and reheat when you are ready to eat.

Recipe: Brined and Roasted Chicken

Makes 8 Chicken Breasts

Maple Brine Ingredients

4 C Boiling Water

7 oz Granulated Sugar

3 oz Kosher Salt

1 C Maple Syrup

3 sprigs Fresh Thyme

4 C Ice

Additional Ingredients

8 Chicken Breasts (6–8 oz each)

Procedure

- Combine boiling water, sugar, salt, maple syrup, and thyme and stir until sugar and salt are completely dissolved.

- Add ice and stir, allowing the liquid to cool completely.

- Rinse the chicken breast and completely submerge in maple brine. Refrigerate for at least five hours.

- After five hours, remove the chicken and rinse clean. Discard the used brine.

- Roast at 350°F until the chicken reaches an internal temperature of 165°F, approximately 15-20 minutes.

- Serve chicken with Tomato Chili Sauce.

Whether you make it for yourself at home, or pay a visit to A Taste of History in Greenfield Village to let us make it for you, let us know what you think!

Eric Schilbe is Executive Sous Chef at The Henry Ford.

making, restaurants, food, by Eric Schilbe, Greenfield Village, recipes, George Washington Carver

Tomato Chili Sauce Recipe

A Taste of History in Greenfield Village offers our visitors seasonal, locally sourced and historically minded recipes. Over the past year, our chefs have been developing some new recipes, directly drawn from the recipes of George Washington Carver and the ingredients that he used. You can learn more about the inspiration behind the new options both in A Taste of History and in Plum Market Kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in our blog post here, or try out some of the recipes for yourself—like this Tomato Chili Sauce.

Chef’s Notes

There are many other sauces that Carver has recipes for in his published papers, but we chose the green Tomato Chili Sauce because it uniquely balances the sweet maple flavor of the Brined and Roasted Chicken (link below) with just enough spice to make it dance on your palette. You can make the sauce ahead of time and reheat when you are ready to eat.

Recipe: Tomato Chili Sauce

Makes 8 Portions

Ingredients

1 lb Fresh Green Tomatoes

3 oz Jalapeno Peppers

3 oz White Onion

1 oz Granulated Sugar

½ C Vinegar

1 Tbs Salt

¼ tsp Pepper

Procedure

- Peel tomatoes by placing in boiling water for 1 minute, shock by placing in ice water, and then peel skins.

- Slice jalapenos in half lengthwise and remove seeds and piths. Reserve seeds for later.

- Dice tomatoes, jalapenos, and onions and combine in small saucepan with all ingredients.

- Bring to a simmer, allow to simmer for 1-2 hours, and then puree.

- Adjust seasoning as necessary with salt, pepper, sugar, and jalapeno seeds. The spice level should be a medium, balanced heat.

- Serve with Brined and Roasted Chicken.

Whether you make it for yourself at home, or pay a visit to A Taste of History in Greenfield Village to let us make it for you, let us know what you think!

Eric Schilbe is Executive Sous Chef at The Henry Ford.

George Washington Carver, restaurants, recipes, making, Greenfield Village, food, by Eric Schilbe

Beyond the Peanut: Food Inspired by Carver

George Washington Carver's Graduation Photo from Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm (now Iowa State University), 1893 / THF214111

George Washington Carver and Food

George Washington Carver (1860s–1943) was born near the end of the Civil War in Missouri. He studied plants his entire life, loved art and science, earned two agricultural science degrees from Iowa State University, and shared his knowledge broadly during his 45-year-career at Tuskegee Institute. He urged farm families to care for their land. Today we call this regenerative agriculture, but in Carver’s day it amounted to a revolutionary agricultural ethic.

Carver’s curiosity about plants fueled another revolution as he promoted hundreds of new uses for things that farm families could grow and eat. Cookbooks inspired him to adapt, and he worked with Tuskegee students to test and refine recipes. Then he compiled them in bulletins that stressed the connection between the environment and human health.

Today, our chefs at The Henry Ford are inspired by Carver’s dozens of bulletins and hundreds of recipes for chutneys, roast meats, salads, and peanut-topped sweet rolls.

Some Possibilities of the Cow Pea in Macon County, Alabama, a 1910 bulletin by Carver featuring recipes. / THF213269

Developing Modern Carver-Inspired Recipes

All Natural Pork with Peanut Plum Sauce at Plum Market Kitchen.

Carver is known to most of us for his many uses for the peanut. The Henry Ford’s culinary team looks to go beyond that, knowing that there is so much more to his legacy. Cultural appropriation is a hot topic in the world of food service today, but as a public history institution, we recognize that food is culture, and we are committed to authentic representation of a variety of food traditions. We are constantly collaborating and developing new recipes in consultation with our curators, who provide expert understanding and context. Part of the mission that drives our chefs is to understand the full story, and to help all our guests complete that experience as well.

Carver-Influenced Menu at Plum Market Kitchen

Kale, Roasted Peanut, and Pickled Red Onion Salad with Molasses Vinaigrette at Plum Market Kitchen

Many aspects of Carver’s legacy are woven into a modern menu at Plum Market Kitchen at The Henry Ford. Today, the ideas of all-natural, healthy, and organic have become “tag lines” to sell you food. However, for Carver, and for Plum Market Kitchen, these have always been a driving ideology. Together, The Henry Ford and Plum Market Kitchen have taken inspiration from many of Carver’s recipes—always looking to honor and continue his legacy.

Digging Deeper into Carver’s Legacy at A Taste of History

Spring offerings from George Washington Carver's recipes at A Taste of History.

While our new recipes at Plum Market Kitchen are inspired by Carver, with modern adaptations, our new offerings in A Taste of History are more directly drawn from Carver’s own recipes and the ingredients he used. Spring offerings at A Taste of History include the following—click through for recipes to try at home.

- Brined and Roasted Chicken

- Tomato Chili Sauce

- Sweet Potato Hash

- Collard Greens with Smoked Turkey

- Peanut Roll Cake with Jelly

Learn More

Farmhouse Roasted Sweet Potatoes at Plum Market Kitchen.

If you’d like to further explore the life and work of George Washington Carver, issues surrounding food security, historic recipes, or dining at The Henry Ford, here are some additional resources across our website:

- Take a closer look at Black empowerment through Black education with the microscope used by agricultural scientist George Washington Carver during his tenure at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

- Throughout Carver’s life, he balanced two interests and talents—the creative arts and the natural sciences. Find out how each influenced the other.

- Learn more about the history of the George Washington Carver Cabin in Greenfield Village.

- Explore artifacts, photographs, letters, and other items related to Carver in our Digital Collections.

- Food security links nutritious food to individual and community health. Explore this concept through the collections of The Henry Ford in this blog post, which includes Carver’s work.

- Find out what a food soldier is, as well as how food and nutrition relate to issues of institutional racism and equity for African Americans.

- Explore historic cookbooks and recipes from our collections.

- Get up-to-date information about dining options in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village.

Eric Schilbe is Executive Sous Chef at The Henry Ford. Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, African American history, George Washington Carver, restaurants, by Eric Schilbe, by Debra A. Reid, recipes, food