1917 Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck” Biplane

The Curtiss JN-4 always turns heads in “Heroes of the Sky.” / THF39670

The Curtiss JN-4 always turns heads in “Heroes of the Sky.” / THF39670Walk into the barnstormers section of our Heroes of the Sky exhibit and odds are the first airplane to catch your eye will be our 1917 Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck” biplane. Whether it’s the airplane’s inverted attitude, its dangling wing-walker, or its fishy-looking fuselage, there’s a lot to draw your attention. And well there should be. The Curtiss Jenny was among the most significant early American airplanes.

Conceived by British designer Benjamin D. Thomas and built by American aviation entrepreneur Glenn Curtiss, the JN airplanes combined the best elements of Thomas’s earlier Model J and Curtiss’s earlier Model N trainer planes. New variants of the JN were increasingly refined. The fourth in the series, introduced in 1915, was logically designated JN-4. Pilots affectionately nicknamed it the “Jenny.” The inspiration is obvious enough, but even more so if you imagine the formal model name (JN-4) written as many flyers first saw it—with an open-top “4” resembling a “Y.”

This Curtiss JN, circa 1915, left no doubt about its manufacturer’s identity. / THF265971

Despite not being a combat aircraft, the Curtiss Jenny became the iconic American airplane of the First World War. Some 6,000 units were built, and nine of every ten U.S. military pilots learned to fly on a Jenny. The model’s low top speed (about 75 mph) and basic but durable construction were ideal for flight instruction. Dual controls in the front and back seats allowed teacher or student to take charge of the craft at any time.

Our JN-4 is one of approximately 1,200 units built under license by Canadian Aeroplanes, Ltd., of Toronto. In a nod to their Canadian origins, these airplanes were nicknamed “Canucks.” While generally resembling American-built Jennys, the Canadian planes have a different shape to the tailfin and rudder, a refined tail skid, and a control stick rather than the wheel used stateside. (The stick became standard on later American-built Jennys.)

Barnstormer “Jersey” Ringel posed while (sort of) aboard his Jenny about 1921. / THF135786

Following the war, many American pilots were equally desperate to keep flying and to earn a living. “Barnstorming”—performing death-defying aerial stunts for paying crowds—offered a way to do both. Surplus military Jennys could be bought for as little as $300. The same qualities that suited the planes to training—durability and reliability—were just as well-suited to stunt flying. The JN-4 became the quintessential barnstormer’s plane, which explains why our Canuck is featured so prominently in the Heroes of the Sky barnstorming zone. As for the inspiration behind our plane’s paint job… that’s another kettle of fish.

Fishing lures, similar to this one, inspired the unusual paint scheme on our Curtiss JN-4. / THF150858

Founded in 1902, James Heddon and Sons produced fishing lures and rods at its factory in Dowagiac, Michigan. Heddon’s innovative, influential products helped it grow into one of the world’s largest tackle manufacturers. That inventive streak spilled over into Heddon’s advertising efforts. In the early 1920s, the company acquired two surplus JN-4 Canucks and painted them to resemble Heddon lures. These “flying fish” toured the airshow circuit to promote Heddon and its products. While our Canuck isn’t an original Heddon plane, it’s painted as a tribute to those colorful aircraft. (Incidentally, the Heddon Museum is well worth a visit when you’re in southwest Michigan.)

Every airplane in Heroes of the Sky has a story to tell. Some of them are even fish stories!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Getting into the Air: Alexander Graham Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association

- A Stunt-Flying Aviatrix

- 1939 Sikorsky VS-300A Helicopter

- A Closer Look: Air Traffic Control Radar Scope

World War I, Canada, 20th century, 1910s, popular culture, Heroes of the Sky, Henry Ford Museum, flying, by Matt Anderson, airplanes

1937 Cord 812 Convertible: Unusual Technology, Striking Style

THF90811

Although it wasn’t the most expensive car of its day, the 1937 Cord was pricey. But its Depression-era buyers were well-off and didn’t mind a stylish car that attracted attention. The Cord’s swooping fenders, sweeping horizontal radiator grille, and hidden headlights were unlike anything else on American highways. And although it wasn’t the first, the Cord was the only front-wheel-drive production car available in America for the next three decades.

This 1937 Cord catalog shows the sedan version of the car. THF83512

The company’s definition of luxury included not only the Cord’s styling but also its comfort, its ease of driving and parking, and the advantages of front-wheel drive. THF83513

Customers who wanted even more luxurious touches could buy accessories from the dealer. The Cord Approved Accessories catalog for 1937 included some items now considered basics, such as a heater, a windshield defroster, and a compass. Image (THF86243) taken from copy of catalog.

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1959 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz Convertible: Is This the Car for You?

- Noyes Piano Box Buggy, about 1910: A Ride of Your Own

- Douglas Auto Theatre Sign, circa 1955

- 2016 General Motors First-Generation Self-Driving Test Vehicle

20th century, 1930s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

Patent Medicine Entrepreneurs: Friend or "Faux"?

Before modern pharmaceuticals and medical practice came to be widely accepted, people had essentially three choices to try to cure what ailed them, none of which was perfect. The first choice was to be treated by a doctor, if one was available, affordable, and trustworthy. The second option was to try a home remedy, found in cookbooks or periodicals or passed down through a family member. The third choice was patent medicines. Readily available and relatively inexpensive—though often suspect and sometimes downright dangerous—patent medicines were a popular option for treatment throughout the 1800s.

The popularity of patent medicines encouraged entrepreneurs to manufacture their own remedies and enter the flourishing patent medicine industry. Some of these entrepreneurs were licensed doctors who decided to become businessmen instead of practitioners. Others were businessmen with a flair for marketing who saw an opportunity to use their skills to peddle an acquired formula or small medicine business they purchased. Unfortunately, some entrepreneurial manufacturers were complete con artists concocting their own remedies that either did absolutely nothing or were quite dangerous to whomever consumed them. Through this blog post, we'll explore the stories behind various entrepreneurial patent medicine manufacturers.

Trade Card for Brown’s Iron Bitters, Brown Chemical Co., 1890-1900. Patent medicines were often advertised as “cure-alls” with packaging and advertisements listing illnesses and complaints that the product was intended to “cure.” This trade card for Brown’s Iron Bitters claims that it cured “indigestion, dyspepsia, intermittent fevers, want of appetite, loss of strength, lack of energy, malaria and malaria fevers,” and other things. / THF277429

The term “patent medicine” is misleading as the medicine advertised was very rarely patented. It originally referred to medicine in which the ingredients were “granted protection for exclusivity,” meaning that the same composition could not be sold by another manufacturer. While it was relatively simple to obtain a patent for medicine, most manufacturers didn’t apply for one because it meant that they would have to divulge the remedy’s ingredients. More often than not, these medicines contained dangerous substances like morphine, cocaine, and high levels of alcohol.

Trade Card for Burdock Blood Bitters, Foster, Milburn & Co., circa 1885. A study conducted by the American Medical Association in 1917 found that Burdock Blood Bitters, a popular patent medicine, contained 25.2% alcohol by volume. This medicine, and others like it, would most likely dull any pain (thanks to the alcohol) but its contents also increased the likelihood of developing dependency or addiction in adults, and could be fatal to children. / THF215182

Having originated in England in the 17th century, patent medicines made their way to America in the 18th century and were a major industry by the 1850s. The last half of the 1800s is considered the “golden age” of American patent medicine, with hundreds of products flooding the market. A number of factors led to this boom in the industry. For one, advances in industrial and manufacturing technology made the process of producing bottles, containers, labels, and the medicine itself more efficient. As the century progressed, advanced transportation methods opened new markets across the continent. Additionally, the introduction of color printing created an advertising frenzy with thousands of newspaper, magazine, trade card, and poster advertisements. And finally, there were essentially no regulations imposed on the drug trade at this time, meaning that individuals could put whatever they wanted into a remedy and advertise it however they pleased. All of this culminated to ensure that the patent medicine trade was highly lucrative, encouraging enterprising individuals to launch their own brand of medicines regardless of medical knowledge or background.

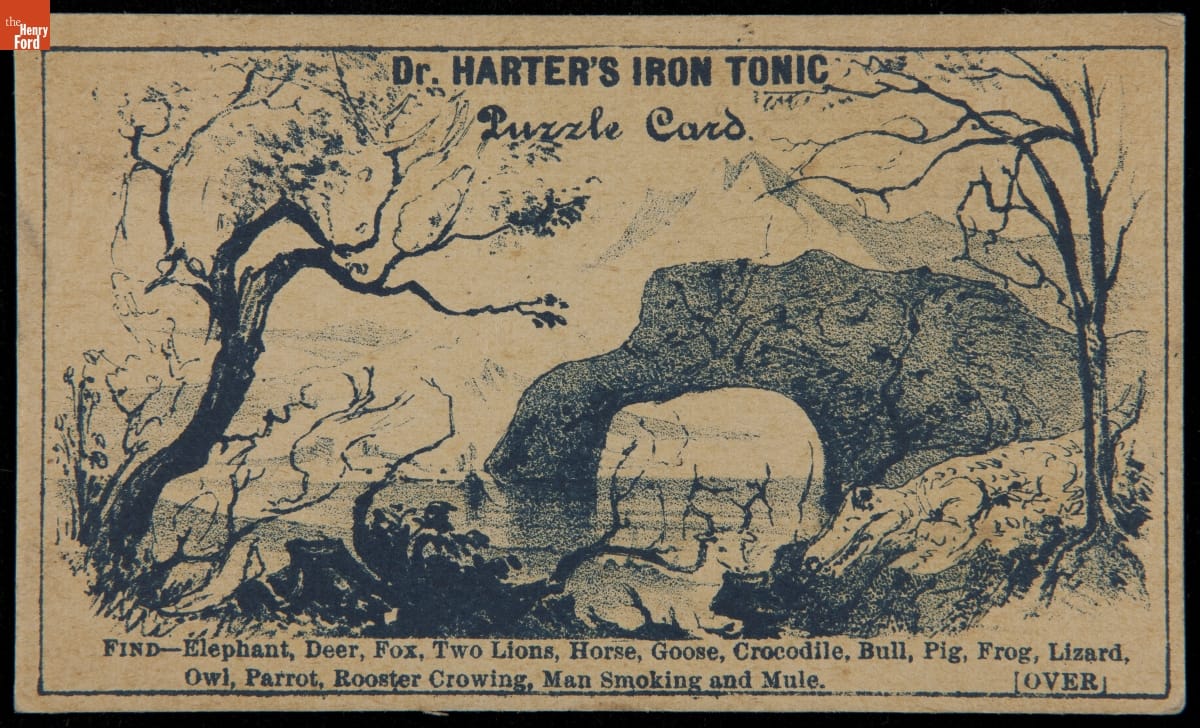

Trade Card for Dr. Harter’s Iron Tonic, 1875-1890. Trade cards were the most popular method for advertising patent medicines. This puzzle card for Dr. Harter’s Iron Tonic featured hidden figures within a drawing for customers to find. / THF214474

While there were hundreds of patent medicines created during this time, the most successful were the ones that were heavily advertised. Consumers encountered many advertisements and brand recognition became extremely important with so many patent medicines on the market. Trade cards of the era inform us who the major players were in the patent medicine industry. They also allow us to examine the advertising tactics used by patent medicine manufacturers to entice potential customers.

Foster, Milburn & Co.

Trade Card for Burdock Blood Bitters, Foster, Milburn, & Co., circa 1885. / THF215179

Orrin Foster and Thomas Milburn were patent medicine manufacturers and distributors. They organized their first business in the 1870s in Toronto before opening a distribution office in Buffalo, New York. The company’s best-known product was Dr. Thomas’ Eclectric Oil, which the pair had purchased from Dr. Samuel N. Thomas in 1876 and marketed heavily to the general public. The back of this trade card for Burdock Blood Bitters—another well-known product by the company—features a popular strategy for advertising patent medicines: testimonials. Testimonials provided prospective buyers with “first-hand experiences” of those who had tried the product. With praises sung by doctors, reverends, and members of the general public, testimonials instilled confidence in the products, persuading consumers to buy. Whether the testimonials were truthful or fabricated is up for debate.

Humphreys’ Homeopathic Medicine Company

Trade Card for Humphreys’ Witch Hazel Oil, Humphrey’s Med. Co., 1870-1900. / THF299894

Humphreys’ Homeopathic Medicine Company is an example of a patent medicine company that actually had a proprietor in the medical field. The company was founded by Frederick K. Humphreys in 1853. He graduated in 1850 from the Pennsylvania Homeopathic Medical College with a Doctor of Homeopathic Medicine degree and established a successful medical practice. Homeopathy is an alternative medical practice based in the belief that the same substances that cause disease in healthy people can be used to treat those who are sick with similar symptoms. According to the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors, Humphreys helped “form the New York State Homeopathic Medical Society and became an important member of the American Homeopathic Institute.” In 1854, Humphreys began manufacturing and selling homeopathic remedies. Witch Hazel Oil—for curing itching, pain from cuts and burns, chapped hands and feet, bug bites, sunburns, etc.—became one of Humphreys' most popular products over time.

Lydia E. Pinkham’s Medicine Company

Trade Card for Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, 1880-1890. / THF298977

Lydia E. Pinkham was one of the most prominent names in the sector of the patent medicine industry that catered to “female complaints.” Before entering the business, Pinkham was a teacher and mother. It is said that she was known among her neighbors for mixing her own herbal remedies, keeping a personal notebook she called “Medical Directions for Ailments.” Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound is believed to have been a secret formula given to Lydia’s husband as payment for money owed to him. The couple began producing the compound in 1875, thus entering the patent medicine business. Their sons, Will and Dan, were tasked with marketing the product. In 1879, Dan came up with the idea of using Lydia’s portrait in advertisements—the first woman’s likeness to be used in advertising. Attaching her likeness and signature to advertising was a huge hit, providing women with a friendly and “knowing” face, which instilled confidence in the product.

Carter Medicine Company

Trade Card for Carter’s Little Liver Pills, Carter Medicine Company, 1880-1890. Trade cards were generally printed as small rectangles but unique shapes, like the painter’s palette shape of this card, were also created and were a beneficial advertising tool. / THF297541

The Carter Medicine Company provides another example of a patent medicine manufacturer with a background in the medical field. Pharmacist Dr. John Samuel Carter began selling “Carter’s Little Liver Pills” out of his pharmacy in Pennsylvania for those with “digestive distress.” The product gained popularity throughout the 1850s and in 1880, Carter formed a partnership with New York businessman Brent Good to establish Carter Medicine Company. By World War I, "Carter's Little Liver Pills" had become such a staple in American households that the company remained in business despite a global economic downturn.

C.I. Hood & Co.

Trade Card for C.I. Hood & Co. with Hood’s Photos of the World, “Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris,” 1890-1910. Trade Cards from Hood’s Photos of the World series gave customers views of faraway places, providing a window to the broader world. / THF297455

C.I. Hood & Co. was one of the most recognized names in the patent medicine industry. In 1875, Charles Ira Hood opened his drug store, C.I Hood & Company, in Lowell, Massachusetts. Within a few years, Hood’s was one of the largest patent medicine producers in the United States. The thing that set Hood’s company apart was its state-of-the-art factory, which included its own advertising department. Hood’s factory produced all sorts of ephemera, including calendars, trade cards, and even cookbooks, which helped make it one of the most successful patent medicine manufacturers.

Dr. Seth Arnold’s Medical Corporation

Trade Card for Dr. Seth Arnold Medical Corporation, 1880-1890 / THF214532, THF214533

Seth Arnold worked in a series of industries before entering the patent medicine business in the late 1840s. Following a venture in hotel management, Arnold took several years off due to his health, beginning in 1835. He was said to have used this time to create a remedy for his illness, a medicine that came to be called “Dr. Arnold’s Balsam.” In the New England Union Directory of 1849, Arnold was cited as an “eclectic physician and patent medicine manufacturer” in Smithfield, Rhode Island, where he was also a physician for cholera. In addition to his balsam, two additional products were created—“Cough Killer” and “Bilious Pills”—to be sold by his company, known as Dr. Seth Arnold’s Medical Corporation. Dr. Seth Arnold’s Cough Killer was believed to be his most popular product, but the others were successful as well. If the testimonial on the back of the trade card above is to be believed, customers as far away as Nebraska used Dr. Seth Arnold’s Bilious Pills.

Sterling Remedy Company

Trade Card for “No-To-Bac” Tobacco Habit Cure, Sterling Products Co., circa 1894. / THF298541

Sterling Remedy Company provides an example of a businessman entering the patent medicine industry without any medical knowledge or background. H.L. Kramer was a self-made businessman who established a publishing and advertising company in Lafayette, Indiana, and held interest or managerial positions in the Humane Remedy Company and the Universal Remedy Company (both manufacturers of patent medicines). One of Kramer’s advertising clients was John W. Heath, a local Indiana banker who owned Sterling Remedy Company. Heath also consulted with Kramer on a project to develop a local health spring into a medicinal spa. Following Heath’s death in 1890, Kramer bought out his widow’s interest in the Sterling Remedy Company and the medical springs. By the mid-1890s, Kramer had launched the springs as a “fashionable Midwestern health resort” known as “Mudlavia” because of its specialty mud bath cures. Under Kramer’s leadership (and with thousands of dollars spent on advertising yearly), Sterling Remedy Company gained popularity. Universal Remedy Company’s “No-To-Bac,” a popular tobacco habit cure, was merged with Sterling Remedy Company’s product line. A common side effect of No-To-Bac was constipation, so the company produced Cascarets to help with this inconvenience. Cascarets became the company's most popular product. Despite success, Kramer sold the company in 1909.

Dr. J.C. Ayer & Co.

Trade Card for Ayer’s Hair Vigor, circa 1885. Ayer’s Hair Vigor became a popular hair restorative following its introduction in the 1860s. Examples of packaging for this patent medicine are on display at the J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village. / THF297658

James C. Ayer was one of the most recognized names in the patent medicine industry. This is largely due to the fact that Ayer was an advertising genius, producing thousands of advertisements in the form of trade cards, almanacs, posters, and newspaper and magazine ads. Young Ayer apprenticed for several years at Jacob Robbins’ Apothecary Shop in Ledyard, Connecticut, and studied under Dr. Samuel Dana. Within a few years, Ayer purchased the apothecary shop and began manufacturing his own medicines, including Cherry Pectoral. His medicine was so popular that he was forced to find a larger manufacturing facility, moving operations to Lowell, Massachusetts. In 1855, Ayer entered into a partnership with his brother to form J.C. Ayer & Company, manufacturing patent medicines. Additional remedies created by Ayer since introducing Cherry Pectoral included Cathartic Pills in 1853, Sarsaparilla and Ague Cure in 1858, and restorative Hair Vigor in 1867. In 1860, the Philadelphia Medical University awarded Ayer with an honorary medical degree, leading to the addition of “Dr.” to the company’s name.

“Ayer’s American Almanac, 1907” / THF285177

While trade cards were certainly one of the most effective advertising methods for patent medicines, major manufacturers printed their own almanacs as well. Dozens of almanacs littered the counters of local general stores and urban pharmacies. In an average year, J.C. Ayer & Co. produced roughly 16 million almanacs. In 1889, Ayer’s distributed 25 million almanacs in 21 languages.

Federal Regulation

While the masses were content to self-prescribe patent medicines for themselves, there were some who questioned the effectiveness of the products and the legitimacy of their proprietors. As previously mentioned, relatively few restrictions were placed on the drug trade at this time and manufacturers were not inclined to provide a list of ingredients for their products. Some reputable doctors took it upon themselves to conduct studies to see what some of the most popular patent medicines were made of, and the results were often startling.

Many medicines were found to contain dangerous levels of alcohol. For instance, one study found that Lydia E. Pinkham's Vegetable Compound contained roughly 20% alcohol. Other remedies were found to contain morphine (like Dr. Seth Arnold's Cough Killer) and cocaine. With reports such as these making the general public aware of dangerous substances in some of their favorite medicines, and growing concern against the manufactured food industry regarding sanitation practices and food additives, the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed in 1906, placing federal regulations on these trades. For patent medicines, the passage of the act called for manufacturers to list any harmful ingredients on their containers and prohibited any false or misleading advertising.

Page from “Ayer’s American Almanac, 1907” noting that its products do not contain alcohol. / THF285178

Following the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act, there was a significant decrease in the number of patent medicines on the market, but there were some companies that were able to remain in business. One of the most successful was Carter Medicine Company. It sustained its legitimacy even with the passage of the Act, and throughout the 20th century, the company diversified its products, leading to research in anti-perspirants and deodorant. The company is still in business today as Carter-Wallace, with well-known products such as Arrid, an antiperspirant and deodorant, and Nair, a hair remover for women.

Two other manufacturers previously mentioned—the Lydia Pinkham Company and Humphreys' Homeopathic Medicine Company (now Humphreys' Pharmacal, Inc.)—also remain in business today with their products available for purchase online.

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford. Special thanks to Donna Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford, for sharing her knowledge and resources on the patent medicine industry and for reviewing this content.

19th century, patent medicines, healthcare, entrepreneurship, by Samantha Johnson, advertising

Recreating the Wright Brothers’ Christmas Tree

Christmas tree in the Wright Home during Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village. (Photo courtesy Jim Johnson)

During Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village, we really enjoy showing how Americans would have celebrated Christmas in the 19th century. In almost all the houses, we use historical primary sources to try to glean out descriptions of what people may have done—but we have almost no concrete visual evidence. However, one huge exception is the Wright Home, the family home of Wilbur and Orville Wright.

We know from various sources that in 1900 there was a big homecoming in Dayton, Ohio. Reuchlin Wright, one of Wilbur and Orville’s older brothers, was returning home from living apart for a very long time, slightly estranged. In celebration, the family decided to put up their first Christmas tree. Wilbur and Orville, who were amateur photographers but probably as good as any professional of the time, documented some of that process.

Within the last decade, we have been able to access a very high-resolution image of the Wright family Christmas tree image from the Library of Congress, and the details just leapt out at us. This photograph, which we know was taken in 1900, documents exactly how the Wright Brothers designed and put up their Christmas tree. We examined all the minutiae in the photo and have attempted to recreate this tree as exactly as possible.

Wright Home Parlor Decorated for Christmas, Original Site, Dayton, Ohio, circa 1900 / THF119489

The toys, the various ornaments—it's all in line with what's typical in the time period. So if you look at the tree in the Wright Home, you’ll see it lit with candles—this is not an electrified house yet in 1900. There's a variety of ornaments designed to hold candies and similar things. It has strung popcorn, which would have been homemade, but it also has store-bought German tinsel garland, glass ornaments (either from Poland or Germany), and all kinds of additional decorations that may have been saved from year to year. There's a homemade star on top that has tinsel tails coming off it.

For many years, we just had a low-resolution, fuzzy photograph of the tree, and we reproduced things as faithfully as we could—for example, what appeared to be a paper scrap-art angel. The first glimpse of the high-resolution photograph absolutely flabbergasted us, because front-and-center on the tree is a little scrap-art of a screaming, crying baby. It must have been some sort of inside joke within the family. We were able to reproduce it exactly as it would have looked on the tree.

The screaming baby scrap-art on the Wright Home Christmas tree, both in the original photo and during Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village.

In keeping with tradition, the tree is also covered with gifts for different members of the family. It seems that the adult gifts were hung unwrapped on the tree, whereas many of the children's things were either wrapped or just placed under the tree, based on the photograph. For example, on the tree, we see a pair of what are known as Scotch gloves—you would have found examples of these in Sears catalogues of the early 1900s. There's also a fur scarf, toy trumpets, and even a change purse, all hung on the tree.

Scotch gloves hanging on the Wright Home Christmas tree, both in the original photo and during Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village.

Beneath the tree, the arrangement of toys and gifts is quite fun. There’s a pair of roller skates, a little toy train, tea sets, furniture sets, and all kinds of different things geared specifically toward all the Wright nieces and nephews who would have come to visit on that Christmas morning.

There's also a wonderful set of photographs associated with the tree after Christmas. For example, there’s one of Bertha Wright, one of Reuchlin’s middle daughters, in the next room over, sitting playing with her toys. She's clearly been interrupted in her play, and you can see that in the expression on her face: “Okay, let's get this over with.”

Bertha Wright, Age Five, Niece of the Wright Brothers, Daughter of Reuchlin Wright, circa 1900 / THF243319

There are also photos outside the house, featuring the sleigh (which is prominent under the tree in the high-res photograph, stacked with books). Behind them in all these photographs is a little fir tree—the tree that was inside the house for Christmas has now been placed out there and propped up in the corner, probably for the winter season.

Milton, Leontine, and Ivonette Wright at Wright Home, Dayton, Ohio, circa 1900 / THF243321

During Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village, we have a wonderful large high-resolution blow-up of the tree photograph set up in the Wright Home for our guests to compare-and-contrast with the recreated tree in the corner. Be sure to stop by the Wright Home to see it on your next Holiday Nights visit!

The original historic photo of the Wright family Christmas tree, displayed in the Wright Home during Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village. (Photo courtesy Brian James Egen)

This post was adapted from the transcript of a video featuring Jim Johnson, Director of Greenfield Village, by Ellice Engdahl, Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, Ohio, 20th century, 1900s, Wright Brothers, research, photographs, home life, holidays, Holiday Nights, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, events, Christmas, by Jim Johnson, by Ellice Engdahl

"Sampling" the Past: Fabrics from America's Textile Mills

In 2017, The Henry Ford acquired a significant collection of materials from the American Textile History Museum (ATHM) when financial challenges forced that organization to close its doors. Founded in 1960, ATHM was located in Lowell, Massachusetts, a city key to the story of the Industrial Revolution and to the American textile industry. For decades, ATHM gathered and interpreted a superb collection of textile machinery and tools, clothing and textiles, and an extensive collection of archival materials. The Henry Ford was among the many museums, libraries, and other organizations to which ATHM's collections were transferred.

The Henry Ford acquired textile machinery, clothing, and textiles, as well as archival material that includes approximately 3,000 cubic feet of printed materials and fabric samples from various textile manufacturers, dating from the early 1800s into the mid-to-late 1900s. As part of the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, The Henry Ford has digitized many sample books, as well as product literature, from the archival material within the ATHM collection.

So, what is a sample book? Textile manufacturing companies – commonly referred to as mills or print works – kept a record of fabrics produced by the company within a given year or season. These records typically consist of a fabric sample attached to a blank page in a bound book, and are often accompanied by information including pattern name, inventory number, dyestuffs, and in a few cases, the retail company for which the fabric was made.

The pages of these books offer a rich look at the broad range of fabrics produced by an increasingly mechanized textile industry, allowing researchers to see the evolution in textile design, materials, and manufacturing techniques. They also allow a glimpse into the various methods of recordkeeping among the many companies represented in the collection. Finally, the books—and the fabric samples within them—provide us with a broad view into the rich color palate of American textiles of the 1800s and 1900s. This is especially helpful for exploring clothing and textiles in the era before widespread color photography, where our understanding of the period is dulled by black-and-white depictions. The sample books are strikingly beautiful, offering an intriguing glimpse of the evolution of styles and patterns over time.

In addition to the sample books, we had the opportunity to digitize several examples of product literature from the 1900s, including catalogs and brochures. The product literature was used for marketing and sales, rather than as a record of production. These materials offer insight into the fabric and designs available for clothing or domestic use during the 1900s.

Have I piqued your interest? Below are a few favorite items I’ve come across in this collection.

Sample Books

Cocheco Manufacturing Company (Dover, New Hampshire & Lawrence, Massachusetts)

Fabric Samples from the Notebook of Washington Anderton, Color Mixer for Cocheco Print Works, 1876-1877 / THF670738, THF670787, THF670757

Fabric Samples from the Notebook of Washington Anderton, Color Mixer for Cocheco Print Works, November to December 1877 / THF670668, THF670707, THF670697

Sample Book, January 9, 1880 to April 22, 1880 / THF600226

Hamilton Manufacturing Company (Lowell, Massachusetts)

Sample Book, April 9, 1900 to May 27, 1901 / THF600027, THF600141, THF600167

Lancaster Mills (Clinton, Massachusetts)

Sample Book, "36 Inch Klinton Fancies," Fall 1927 / THF299907, THF299924

Sample Book, "Glenkirk," Spring 1928 / THF299970, THF299971

Product Literature

Hellwig Silk Dyeing Company (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

Sample Book, "Indanthrene Colors," 1900-1920 / THF299990

Montgomery Ward & Co. (Chicago, Illinois)

Suit Catalog, "Made to Measure All Wool Suits," 1932 / THF600534

I.V. Sedler Company, Inc. (Cincinnati, Ohio)

Catalog, "The Nation's Stylists Present Sedler Frocks," 1934 / THF600502

Carlton Mills, Inc. (New York, New York)

Sales Catalog for Men's Fashion, 1940-1950 / THF670587

Harford Frocks, Inc. (Cincinnati, Ohio)

"Frocks by Harford Frocks, Inc.," 1949 / THF600604

Sears, Roebuck and Company (Chicago, Illinois)

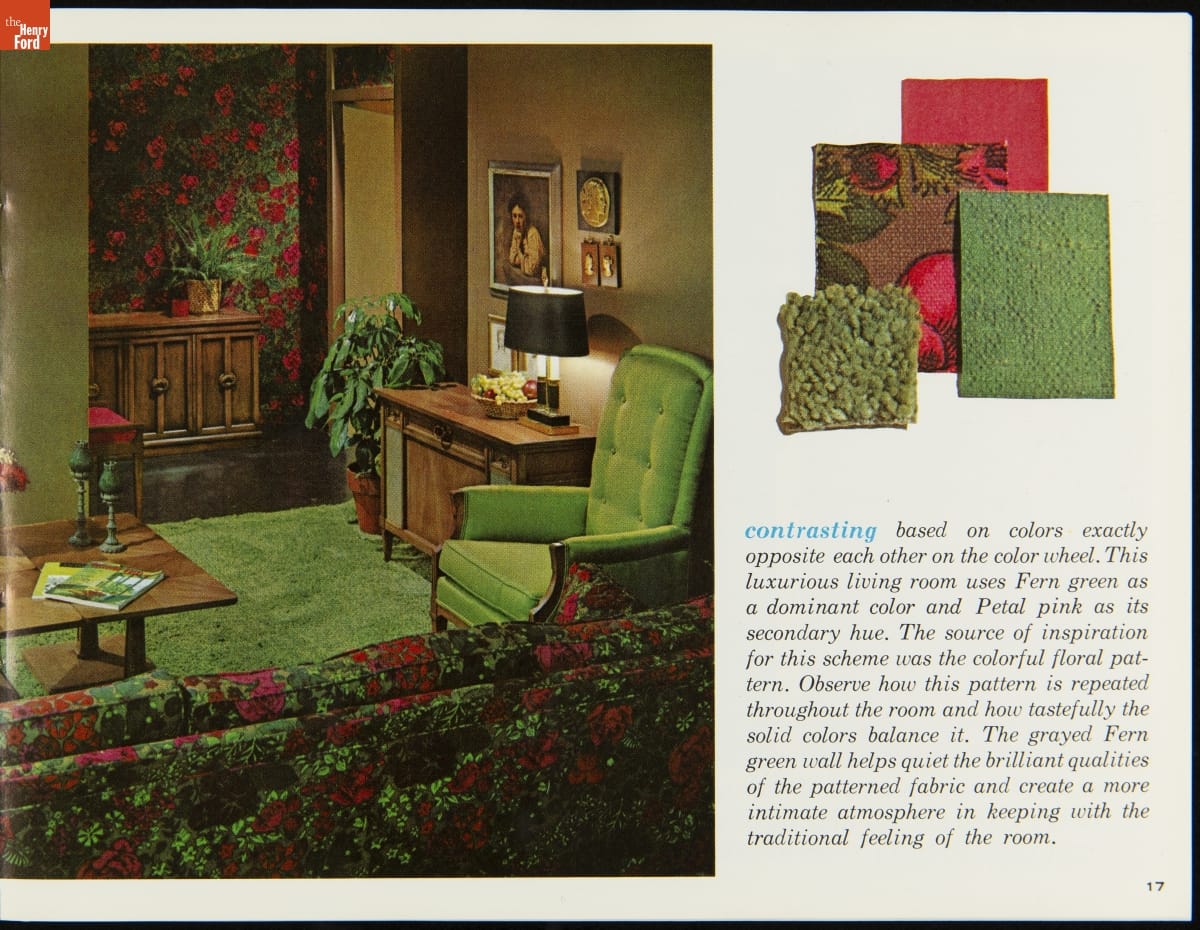

"Sears Decorating Made Easy," 1964 / THF600561

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford. Special thanks to Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford for sharing her expertise of the textile industry and for reviewing this content.

20th century, 19th century, manufacturing, furnishings, fashion, entrepreneurship, by Samantha Johnson

What Type of Super Hero Are You?

Superman lunchbox, 1954, THF145091

Comic book super heroes can now be found pretty much everywhere: movies, TV shows, handheld games, action figures, and other merchandise. For those of you unfamiliar with the universes and the multiverses, it’s easy to get confused about the plethora of super heroes that are out there today. But if you’re trying to make sense of it all, here’s the single most important thing you need to know. Is it a DC or a Marvel super hero?

To help you understand the differences between these two comic book companies’ approaches, here’s a little personality test. (If the embedded quiz below doesn't work for you, you can also access it here.)

Tour Our Entrepreneurship Sagan

The Henry Ford has long explored creative ways to share our world-renowned collections and provide our guests and visitors with exciting new ways to interact with them. Earlier this year, we launched a new virtual experience that we created in partnership with Saganworks, a technology startup from Ann Arbor, Michigan.

What we created is a Sagan: a virtual room capable of storing content in a variety of file formats, and experienced like a virtual gallery. The Henry Ford curated this Sagan to highlight some of the work the museum has done under the auspices of the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, which focuses on providing resources and encouragement for the entrepreneurs of today and tomorrow. Our Sagan highlights entrepreneurial stories and collections, displaying a sampling of objects we’ve digitized and content we’ve created, all in one place.

As a startup, Saganworks is continuously adapting and evolving its product, and we are happy to announce that we now have the ability to embed our Sagan right here within our blog for you to interact with. (Though please note that this is best experienced on desktop—to experience the Sagan on your phone, you’ll be prompted to download the Saganworks app.)

Continue Reading

Saganworks, entrepreneurship, by Samantha Johnson, technology

Arriving at the holiday season in true 2020 fashion, the Museum experience will be different this year. Santa is focusing his time at The Henry Ford on the physically distant experience at Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village. We will miss seeing the joy of personal visits at Santa’s Arctic Landing and the exploration at seasonal hands-on opportunities. While we regret our inability to offer these programs to guests, there are still many festive offerings in the Museum between November 21st and January 3rd.

A towering 25’ Christmas tree as the centerpiece of the Plaza.

Historic dollhouses decorated for the season. Look for three Marvel characters inviting themselves to these miniature vignettes!

Celebrating the Jewish Holiday of Hanukkah was a favorite in 2018. This year, it includes new acquisitions (face masks and a battery-operated menorah) to bring the display right up to the minute.

Della Robbia (Colonial Revival decorative items using fruit and foliage) on the façade of the Museum and within the Clocktower.

Our model train layout is once again decorated with festive lights and holiday happenings.

The Michigan LEGO Users Group (MichLUG) has brought us yet another knockout layout. While we usually ask them for a Detroit cityscape, this year they approached us with the idea of also adding Hogwarts. Why not?

Though the Years with Hallmark: Holiday Ornaments is back with 136 ornaments in a new location. Look for this sampling of our enormous collection of Hallmark ornaments in the awards alcove in the Promenade, between the Museum Store and the Clocktower.

In short, there are still plenty of reasons to feel the cheer of the season in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation—and you can explore even more of our seasonal events and stories on our holiday round-up page.

Kate Morland is Exhibits Manager at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2020s, holidays, Henry Ford Museum, Hanukkah, events, COVID 19 impact, Christmas, by Kate Morland

The Click Heard around the World

The auditorium at the 1968 Fall Joint Computer Conference before guests arrive. / THF610598

The setting is sparse. The downward sweep of theatre curtains, a man seated stage left, backed by a hinged office cubicle wall. Technology in this image is scarce, and yet it defines the moment. A video camera is perched on top of the wall, its electronic eye turned downwards to surveil a man named Douglas Engelbart, seated in a modified Herman Miller Eames Shell Chair below. A large projection screen shows a molded tray table holding a keyboard at its center, a chunky-looking computer mouse made of wood on the right side, and a “chording keyboard” on the left. Today, we take the computer mouse for granted, but in this moment, it was a prototype for the future.

The empty auditorium chairs in this image will soon be filled with attendees of a computer conference. It is easy to imagine the collective groan of theater seating as this soon-to-arrive audience leans a little closer, to understand a little better. With the click of a shutter from the back of the room, this moment was collapsed down into the camera lens of a young Herman Miller designer named Jack Kelley. He knew this moment was worth documenting because if the computer mouse under Douglas Engelbart’s right hand onstage was soon going to create “the click that was heard around the world,” this scene was the rehearsal for that moment.

Entrance to the 1968 Fall Joint Computer Conference, San Francisco Civic Auditorium. / THF610636

“The Mother of All Demos”

On December 9, 1968, Douglas Engelbart of the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) hosted a session at the Joint Computer Conference at the Civic Center Auditorium in San Francisco. The system presented—known as the oNLine System (or NLS)—was focused on user-friendly interaction and digital collaboration.

Douglas Engelbart demonstrates the oNLine System. / THF146594

In a span of 90 minutes, Engelbart (wearing a headset like the radar technician he once was) used the first mouse to sweep through a demonstration that became the blueprint for modern computing. For the first time, computing processes we take for granted today were presented as an integrated system: easy navigation using a mouse, “WYSIWYG” word processing, resizable windows, linkable hypertext, graphics, collaborative software, videoconferencing, and presentation software similar to PowerPoint. Over time, the event gained the honorific “The Mother of all Demos.” When Engelbart was finished with his demonstration, everyone in the audience gave him a standing ovation.

Fixing the Human-Hardware Gap

In 1957, Engelbart established the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at SRI to study the relationship between humans and machines. It was here, in 1963, that work on the first computer mouse began. The mouse was conceptualized by Engelbart and realized from an engineering standpoint by Bill English. All the while, work on NLS was percolating in the background.

Douglas Engelbart kicks back with the NLS at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). / THF610612

While Engelbart was gearing up to present the NLS, Herman Miller Research Corporation’s (HRMC’s) president and lead designer Robert Propst was updating the “Action Office” furniture system. Designed to optimize human performance and workplace collaboration, Action Office caught Engelbart’s attention. He was excited by its flexibility and decided to consult with Herman Miller to provide the ideal environment for people using the NLS. Propst sent a young HMRC designer named Jack Kelley to California so he could study the needs of the SRI group in person.

Jack Kelley and Douglas Engelbart testing Herman Miller’s custom Action Office setup at Stanford Research Institute. / THF610616

After observing and responding to the needs of the team, Kelley recommended a range of customized Action Office items, which appeared onstage with Engelbart at the Joint Computer Conference. One of the items that Kelley designed was the console chair from which Engelbart gave his lecture. He ingeniously paired an off-the-shelf Shell Chair designed by Charles and Ray Eames with a molded tray attachment to support the mouse and keyboard. This one-of-a-kind chair featured prominently in The Mother of All Demos.

An unobstructed view of Jack Kelley’s customization of an Eames Shell Chair with removable, swinging tray for the NLS. The chording keyboard is visible at left, and the prototype mouse is at right. / THF610615

During the consultation, Kelley also noticed that Engelbart’s mouse prototype had difficulty tracking on hard surfaces. He created a “friendly” surface solution by simply lining the right side of the console tray with a piece of Naugahyde. If Engelbart was seen to be controlling the world’s first mouse onstage in 1968, Kelley contributed one very hidden “first” in story of computing history too: the world’s first mousepad. Sadly, the one-of-a-kind chair disappeared over time, but luckily, we have many images documenting its design within The Henry Ford’s archival collections.

A closer view of the world’s first mousepad – the beige square of Naugahyde inset into the NLS tray at bottom right. / THF610645

The computer scientist Mark Weiser said, “the most profound technologies are the ones that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.” If this is true, the impact of Engelbart’s 1968 demonstration—supported by Kelley’s console chair and mousepad—are hidden pieces of the computing history. So as design shaped the computer, the computer also shaped design.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

California, 20th century, 1960s, technology, Herman Miller, design, computers, by Kristen Gallerneaux

Print-at-Home Holiday Gift Tags

My name is Cheryl Preston, and I’m a graphic designer and design director at The Henry Ford. What I get to do here is design graphics for print and online use—design to educate teachers and learners, market events, support the stories we tell, sell food experiences, tempt shoppers, and guide visits around the museum, village and factory tour. I get to combine two passions, history and design, in one job.

2020 Ballotini Ornament, combined with a gift tag.

We all know 2020 has been crazy and difficult in many ways. I have been working on this year’s digital-only holiday retail campaign, where we are featuring a lot of new and old favorite signature handcrafts, along with fun, innovative toys. This has been a bright spot in tough pandemic times for me right now.

It got me thinking how we still love to gift friends and family. After you’ve found the perfect collectible glass candy cane, or an overshot woven placemat set, made in the village weaving shop, which will look great on your friend’s table, you have to wrap it!

Overshot Placemat, combined with gift tags.

I wanted to create a tiny bit of “happy" to give our supporters, with these free printable gift tags to bring the cheer. We all need even the tiny smiles, right? You can preview the gift tags below, or click here to download a PDF version of them for printing at home.

I’m in awe of the handcrafts from our Greenfield Village artists, and the products we offer to bring the past forward, and hope these tags help you share the fun!

Cheryl Preston is Design Director at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2020s, shopping, making, holidays, design, COVID 19 impact, Christmas, by Cheryl Preston, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford