Posts Tagged luxury cars

Early American Luxury at 2022 Old Car Festival

Banners with vintage Lincoln artwork welcomed visitors to the 2022 Old Car Festival at Greenfield Village. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

We observed a beloved late-summer tradition September 10–11, 2022, with Old Car Festival, our annual celebration of automobiles built between the 1890s and 1932. First held in 1951, Old Car Festival is the longest-running antique automobile show in the United States. (Though we should probably put an asterisk on that, thanks to 2020, when Old Car Festival—like most events—was canceled.)

Luxury was often synonymous with a higher cylinder count. Cadillac delivered with this 1915 V-8 touring car. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Each year, we turn our spotlight on a special make, model, individual, or theme. February 2022 brought the 100th anniversary of Ford Motor Company’s acquisition of Lincoln Motor Company, so it seemed fitting to feature the broader subject of “Early American Luxury.” (We’d already celebrated Lincoln specifically at this year’s Motor Muster.) Certainly, this theme includes Lincoln, but it also encompasses names like Packard, Cadillac, LaSalle, Pierce-Arrow, and Peerless. These are the marques that defined the very term “luxury car” in the early decades of the 20th century.

Detroit Central Market housed a selection of luxury vehicles from show participants and from The Henry Ford’s own collection. / Photo by Matt Anderson

This year was our first opportunity to incorporate the Detroit Central Market building into Old Car Festival activities. We took advantage of the spacious new structure to show select upmarket American cars drawn from show participants and from The Henry Ford’s own collection. Among the museum’s cars on view were a 1915 Cadillac Type 51 touring car, representing the first mass-produced V-8 automobile, and a 1923 Lincoln Model L touring car that once belonged to Thomas Edison. We also showed our 1922 Detroit Electric coupe. The little coupe might not have seemed so impressive alongside the big touring cars, but there was a time when electric automobiles were purposely marketed to well-to-do women.

This 1915 Packard Twin Six (Packard’s term for its V-12 engine) embodies our “Early American Luxury” theme. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Several magnificent participant cars rounded out our Central Market display. From Packard, we had a 1915 Twin Six touring car and a 1927 Series 626 sedan. From Franklin, we had a 1931 Series 151 sedan. Auburn—part of E.L. Cord’s Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg empire—was represented by a pair of beautiful 1929 models, including a cabriolet and one of the company’s beloved boat-tail speedsters. Our special exhibit wasn’t limited to exclusive marques. Luxury cars for customers of (relatively) more modest means were represented by a 1928 Studebaker President sedan and a 1930 LaSalle coupe.

Model T cars, wagons and trucks were everywhere at Old Car Festival, including this 1924 depot hack parked near Sarah Jordan Boarding House. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

We had more than 730 vehicles registered for this year’s show. Automobiles, station wagons, trucks, bicycles, and even a few military vehicles were spread throughout Greenfield Village over the weekend. Visitors could enjoy the sights and sounds of a 1910s ragtime street fair along Washington Boulevard. They could attend a 1920s-era community garden party near Ackley Covered Bridge. They could watch the Canadian Model T assembly team put together a Ford automobile in mere minutes. Or they could hear about wartime struggles on the Western Front outside Cotswold Cottage. At the Ford Home, near the village entrance, Old Car Festival visitors could take in an exhibition of tractors and internal-combustion engines that took some of the backbreaking labor out of early-20th-century farming. For festival participants in a matrimonial mood, our friends at Hagerty arranged a Drive-Thru Vow Renewals experience. Registered show-car owners could drive their antique vehicles past the makeshift altar in front of Edison Illuminating Company’s Station A and “re-light” their nuptials.

Martha-Mary Chapel provided an inspiring backdrop for cars on the Village Green. It also housed a series of special programs throughout the weekend. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

Speaking of altars, Martha-Mary Chapel hosted several programs and presentations during Old Car Festival. Tom Cotter, author and host of the popular web series Barn Find Hunter, presented twice during the weekend. On Saturday, he went behind the scenes of his car-seeking show with “A Barn-Finding Life.” On Sunday, Cotter recalled the 3,000-mile journey chronicled in his book Ford Model T Coast to Coast. On both days, longtime festival participant Daniel Hershberger discussed early auto touring and roadside camping. Hershberger dedicated his talks to the memory of Randy Mason, a former curator of transportation at The Henry Ford who passed away earlier this year. Also on both days, historian Joseph Boggs looked at the fascinating relationship between automobiles and 1920s Prohibition. Cars factored into both sides of the equation—used by rumrunners and law enforcement officers alike.

Of special interest were two panel discussions on early American luxury cars, held on Saturday and Sunday. Through the generous support of the Margaret Dunning Foundation, we brought together three experts in the field: Bob Casey, retired curator of transportation at The Henry Ford; David Schultz, president of the Lincoln Owners Club; and Matt Short, former curator at the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Automobile Museum and former director of America’s Packard Museum. Our panelists discussed the innovators, manufacturers, and automobiles that defined luxury motoring into the 1930s. Their Sunday session was livestreamed and can be viewed here on The Henry Ford’s Facebook page.

Select participating vehicles at Old Car Festival were judged for various class awards. From those winners, one grand champion was selected each day. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

Visitors may not be aware of a special distinction (apart from chronology) that separates Old Car Festival from our Motor Muster show. Participants at Old Car Festival can choose to have their vehicles judged by a team of vintage-automobile experts. The judges determine Vehicle Class Awards based on authenticity, quality of the restoration work, and care with which each car is maintained. First-, second-, and third-place prizes are awarded in 11 different classes. One overall Grand Champion is selected on each day of the festival. Additionally, two Curator’s Choice Awards are presented to unrestored vehicles, and guests and participants are invited to vote for their favorites in the People’s Choice Awards. The full list of our 2022 award winners may be viewed here.

Old Car Festival includes trucks, too. Commercial vehicles line Christie Street during the event. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

Great crowds, good weather, and impressive vehicles made for a perfect show in 2022. While it’s always hard to say goodbye to summer, Old Car Festival is certainly a fine way to do it. We look forward to next year’s event already.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2020s, Old Car Festival, luxury cars, Greenfield Village, events, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson

1931 Duesenberg Model J Convertible Victoria: The World’s Finest Motorcar?

THF90796

Fred Duesenberg set out to build an automotive masterpiece. Its superlative engineering included a 265-horsepower engine that could push the car to a 116-mph top speed. Duesenberg built only 481 Model Js between 1928 and 1935. No two are identical because independent coachbuilders crafted each body to the buyer’s specifications. Is it the world’s finest? One thing is certain--the Model J will always be in the running.

Duesenberg ads associated the car with wealth and privilege. / THF101796, THF83515

These are a few of the many body styles offered in a 1930 catalog. But that was just a starting point--each car was customized to the owner’s taste. / THF83517, THF83518, THF83519

The Henry Ford’s Duesenberg has luggage designed to fit the trunk precisely. / THF90800

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1937 Cord 812 Convertible: Unusual Technology, Striking Style

- 1903 Oldsmobile Curved Dash Runabout

- 1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One

- 1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

20th century, 1930s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

1912 Rambler Knickerbocker Limousine: A Grand Car for Grand Living

THF91242

Seven feet, seven inches tall, this limousine was designed to make a grand entrance. And it wasn’t short on style, either. Even the chauffeur’s compartment was done up in leather and mahogany. The owners gazed at the world through French plate-glass windows or shut out prying eyes with silk curtains. They enjoyed an umbrella holder, a hat rack, a flower vase, and interior electric lights to illuminate them all.

This 1910 ad for the Rambler limousine promotes luxuries such as a mahogany ceiling, a mirror, a clock, a cigar case, and a speaking tube so the owner could talk to the chauffeur. / THF83353

The Rambler, like many luxury cars, published a magazine for owners. Many issues emphasized the company’s quality construction methods. / THF83351

Rambler Magazine showed workers putting finishing touches on a body in 1911. Before Henry Ford developed the moving automotive assembly line in 1913, cars were built like this—on sawhorses. / THF83356

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

1956 Continental Mark II Sedan: “The Excitement of Being Conservative”

THF90723

In an era of extreme automotive styling, the Mark II was elegantly understated. Its advertising slogan, “the excitement of being conservative,” confirmed that Mark II’s appeal depended not on chrome, but rather on flawless quality control, extensive road testing, shocks that adjusted to speed, and power steering, brakes, windows, and seats. Not understated was the $10,000 price. Owned by VIPs like Frank Sinatra and Nelson Rockefeller, it was the most expensive American car you could--or couldn’t--buy.

William Clay Ford (left) reviews a clay model of the Mark II in 1953. He inherited a passion for styling from his father, Edsel Ford, and directed the Mark II’s design and development. / THF112905

The dashboard--luxurious in 1956--featured an instrument panel inspired by airplanes, with a pushbutton radio, watch-dial gauges, and throttle-style climate control levers. / THF113250

Like the car, advertising was understated. This Vogue magazine ad links the car with classic design in architecture and fashion. / THF83341

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

- The Henry Ford’s Tollbooths and the Cost of Good Roads

- 1981 Checker Marathon Taxicab

20th century, 1950s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, cars

1931 Bugatti Type 41 Royale Convertible: Unmatched Style and Luxury

THF90825

Longer than a Duesenberg. Twice the horsepower of a Rolls-Royce. More costly than both put together. The Bugatti Royale was the ultimate automobile, making its owners feel like kings. It is recognized as the epitome of style and elegance in automotive design. Not only did it do everything on a grander scale than the world’s other great luxury cars, it was also rare. Bugatti built only six Royales, whereas there were 481 Model J Duesenbergs and 1,767 Phantom II Rolls-Royces.

Ettore Bugatti formed Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. in 1909. His cars were renowned for their exquisite design and exceptional performance—especially in motor racing. According to lore, Bugatti was at a dinner party when a woman compared his cars unfavorably with those of Rolls-Royce. In response, he designed the incomparable Royale.

The Royale's elephant mascot was based on a sculpture by Rembrandt Bugatti, Ettore Bugatti's brother, who died in 1916. / THF90827

Because Bugatti Royales are so rare, each has a known history. This is the third Royale ever produced. Built in France and purchased by a German physician, it traveled more than halfway around the world to get to The Henry Ford. Here is our Bugatti’s story.

Joseph Fuchs took this 1932 photograph of his new Bugatti, painted its original black with yellow trim. His daughter, Lola, and his mechanic, Horst Latke, sit on the running board. /THF136899

1931: German Physician Joseph Fuchs orders a custom Royale. Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. builds the chassis in France. Its body is crafted by Ludwig Weinberger in Munich, Germany.

1933: Fuchs leaves Germany for China after Hitler becomes chancellor, taking his prized car with him.

1937: Japan invades China. Fuchs leaves for Canada—again, with his car. Having evaded the furies of World War II, Fuchs and his Bugatti cross Canada and find a home in New York City.

1938: A cold winter cracks the car’s engine block. It sits, unable to move under its own power, for several years.

1943: Charles Chayne, chief engineer of Buick, buys the Bugatti. He has it restored, changing the paint scheme from black and yellow to white and green.

1958: Now a General Motors vice-president, Chayne donates the Bugatti to Henry Ford Museum.

1985: For the first time, all six Bugatti Royales are gathered together in Pebble Beach, California.

The first-ever gathering of all six Bugatti Royales thrilled the crowds at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in 1985. They are the ultimate automotive expression of style and luxury. / THF84547

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1903 Oldsmobile Curved Dash Runabout

- Fozzie Bear’s 1951 Studebaker Commander

- 1956 Chevrolet Bel Air Convertible

- Mimi Vandermolen and the 1986 Ford Taurus

20th century, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

1915 Brewster Town Landaulet: 20th-Century Technology, 19th-Century Comfort

THF91073

Wealthy Americans were familiar with the Brewster name because the company had been building elegant horse-drawn carriages for over 100 years. When Brewster finally began building automobiles in 1915, they looked like carriages. Chauffeurs dealt with the 20th-century auto technology—a quiet 55-horsepower engine, an electric starter, and electric lights—while owners rode in 19th-century carriage comfort. Tradition eventually lost out to the rush of modernity, and Brewsters began to look like cars.

Look closely at this 1890 Brewster landau carriage in The Henry Ford’s collection, and you’ll notice some similarities to the Brewster automobile. / THF80571

“Landaulet” is a car body style with separate compartments for passengers and driver. The passenger compartment is usually convertible. The driver’s compartment can be either enclosed or open. / THF206171

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

20th century, 1910s, luxury cars, horse drawn transport, cars

THF90312

The secret to this car’s striking look is a blend of English elegance and Italian aggressiveness. Late-1950s Rolls-Royces inspired the Riviera’s creased fenders and crisp roofline. But the Riviera leans forward, like a cat poised to pounce—or a Ferrari poised to win races. The tension between these approaches makes the Riviera one of the most memorable designs of the 1960s.

General Motors styling chief Bill Mitchell looked at Rolls-Royces, like this 1960 Silver Cloud II, for inspiration. They were modern without being trendy. THF84938

Many elements of this Ferrari 250 GT Pininfarina coupe slant forward to create an aggressive look. Can you see similarities between it and the Riviera? THF84932

Buick compared the car’s interior styling to that of an airplane, claiming the driver “probably feels more like a pilot” in the Riviera’s bucket seats. THF84935

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

1908 Stevens-Duryea Model U Limousine: What Should a Car Look Like?

THF90991

Early car buyers knew what motor vehicles should look like--carriages, of course! But automobiles needed things carriages didn’t: radiators, windshields, controls, horns, and hoods. Early automakers developed simple solutions. Brass, often used for carriage trim, was adopted for radiators, levers, and horns. Windshields were glass plates in wood frames. Rectangular sheet metal covers hid engines. The result? A surprisingly attractive mix of materials, colors, and shapes.

Although the Stevens-Duryea Company claimed its cars had stylish design, most early automakers worried more about how the car worked than how it looked. / THF84913

To build a car body, early automakers had to shape sheet metal over a wooden form. Cars made that way, like this 1907 Locomobile, often looked boxy. / Detail, THF84914

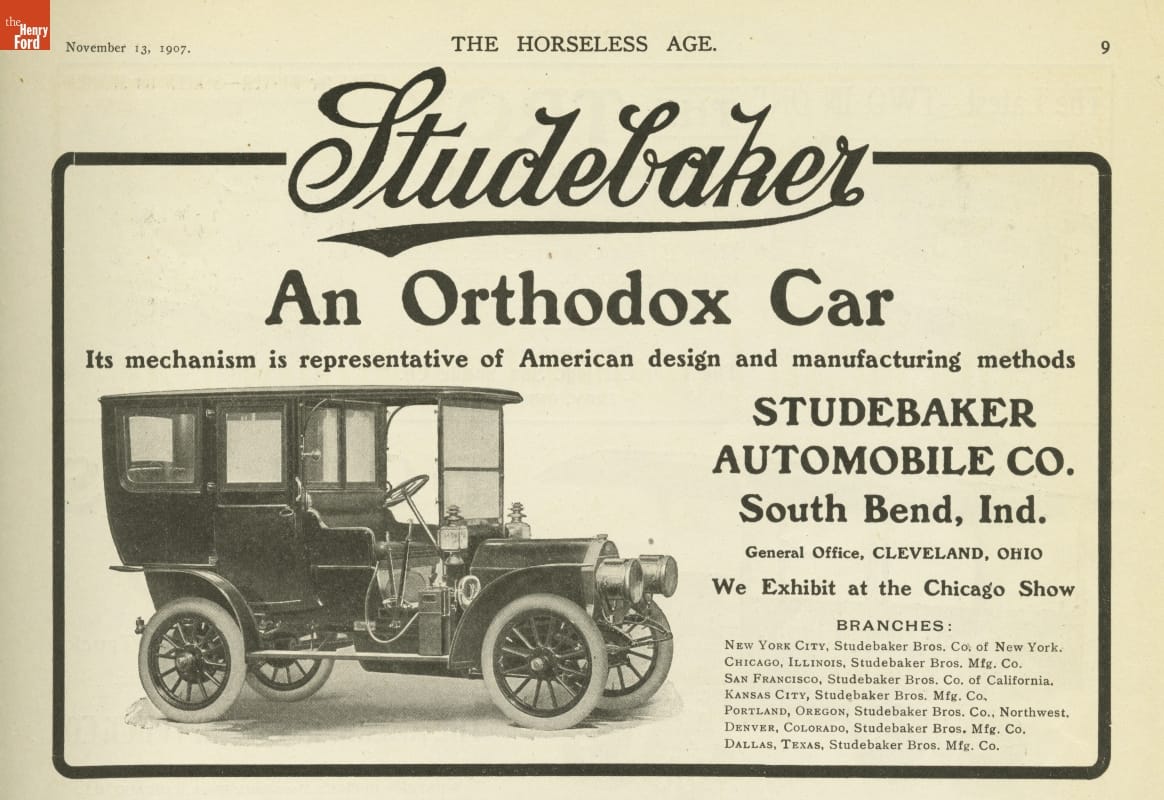

Some early automobiles looked good. But even the attractive ones looked like an assembly of parts, like the Studebaker shown in this 1907 ad. / THF84915

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- Women in the War Effort Workforce During WWII

- 2002 Toyota Prius Sedan: An Old Idea Is New Again

- 1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

20th century, 1900s, limousines, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, design, cars

1937 Cord 812 Convertible: Unusual Technology, Striking Style

THF90811

Although it wasn’t the most expensive car of its day, the 1937 Cord was pricey. But its Depression-era buyers were well-off and didn’t mind a stylish car that attracted attention. The Cord’s swooping fenders, sweeping horizontal radiator grille, and hidden headlights were unlike anything else on American highways. And although it wasn’t the first, the Cord was the only front-wheel-drive production car available in America for the next three decades.

This 1937 Cord catalog shows the sedan version of the car. THF83512

The company’s definition of luxury included not only the Cord’s styling but also its comfort, its ease of driving and parking, and the advantages of front-wheel drive. THF83513

Customers who wanted even more luxurious touches could buy accessories from the dealer. The Cord Approved Accessories catalog for 1937 included some items now considered basics, such as a heater, a windshield defroster, and a compass. Image (THF86243) taken from copy of catalog.

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1959 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz Convertible: Is This the Car for You?

- Noyes Piano Box Buggy, about 1910: A Ride of Your Own

- Douglas Auto Theatre Sign, circa 1955

- 2016 General Motors First-Generation Self-Driving Test Vehicle

20th century, 1930s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

Exposed Engine: 1926 Rolls-Royce New Phantom Limousine

1926 Rolls-Royce New Phantom Limousine

Inline 6-cylinder engine, overhead valves, 468 cubic inches displacement, 108 horsepower

Rolls-Royce’s New Phantom engine, introduced in 1925, featured twin ignition with two spark plugs in each of its six cylinders. Those cylinders were cast in two sets of three, coupled by a one-piece cylinder head. Great Britain taxed automobiles based on cylinder bore. To reduce its tax penalty, the New Phantom engine was “undersquare” with its 4¼ -inch bore smaller than its 5½-inch stroke.

20th century, 1920s, Europe, luxury cars, limousines, Engines Exposed, engines, cars, by Matt Anderson