Posts Tagged massachusetts

“Female Operatives Are Preferred”: Two Stories of Women in Manufacturing

Automatic Pinion Cutter, Used by the Waltham Watch Company, circa 1892 / THF110250

The roles women play in manufacturing are occasionally highlighted, but are often hidden—opposing states that these two stories from our collections demonstrate.

The Waltham Watch Company in Massachusetts was a world-famous example of a highly mechanized manufacturer of quality consumer goods. Specialized labor, new machines, and interchangeable parts combined to produce the company's low-cost, high-grade watches. Waltham mechanics first invented machines to cut pinions (small gears used in watch movements) in the 1860s; the improved version above, on exhibit in Made in America in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, was developed in the 1890s.

This article, “The American Watch Works,” from the July-December 1884 issue of Scientific American, discussed the women workers of the Waltham Watch Company. / THF286663

In the late 19th century, reports on the world-renowned company featured women workers. An 1884 Scientific American article specifically called out women’s work. The article explained that, “For certain kinds of work female operatives are preferred, on account of their greater delicacy and rapidity of manipulation.” Recognizing that gendered experiences—activities that required manual dexterity, such as sewing, or the exacting work of textile production—had prepared women for a range of delicate watchmaking operations, the Waltham company hired them to drill, punch, polish, and finish small watch parts, often using machines like the pinion cutter above. The company publicized equal pay and benefits for all its employees, but women workers were still segregated in many factory facilities and treated differently in the surrounding community.

Burroughs B5000 Core Memory Plane, 1961. / THF170197

The same reasoning that guided women’s work at Waltham in the 19th century led 20th-century manufacturers to call on women to produce an early form of computer memory called core memory. Workers skillfully strung tiny rings of magnetic material on a wire grid under the lens of a microscope to create planes of core memory, like the one shown above from the Burroughs Corporation. (You can learn more about core memory weaving here, and more about the Burroughs Corporation here.) These woven planes would be stacked together in a grid structure to form the main memory of a computer.

However, unlike the women of Waltham, the stories of most core memory weavers—and other women like them in the manufacturing world—are still waiting to be told.

This post was adapted from a stop on our forthcoming “Hidden Stories of Manufacturing” tour of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in the THF Connect app, written by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. To learn more about or download the THF Connect app, click here.

Additional Readings:

- Ingersoll Milling Machine Used at Ford Motor Company Highland Park Plant, 1912

- The China Trade in the 17th and 18th Centuries

- Ford Methods and the Ford Shops

- Thomas Blanchard’s Wood Copying Lathe

20th century, 19th century, Massachusetts, women's history, THF Connect app, technology, manufacturing, Made in America, Henry Ford Museum, computers, by Saige Jedele

Memorial Paintings for Memorial Day

Americans always treasured the memory of the dearly departed, but during the era just after American independence, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, elaborate and artistic memorials were the norm. Scholars debate the reasons. Many believe that with the death of America’s most revered founding father, George Washington, in 1799, a fashion developed for creating and displaying memorial pictures in the home. Other scholars argue that the death of Washington coincided with the height of the Neoclassical, or Federal style in America. During the period after the Revolution, Americans saw themselves as latter-day Greeks and Romans. After all, they argued, the United States was the first democracy since ancient times. So, they used depictions of leaders like George Washington, along with imagery derived from antiquity.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for George Washington, by Mehetabel Wingate, 1800-1810 / THF6971

This wonderful memorial painting of George Washington was drawn in pencil and ink and painted in watercolors by a woman in Haverhill, Massachusetts, named Mehetabel Wingate. Born in 1772, Mehetabel was likely trained in painting as part of her education at an academy for genteel young ladies, much like a “finishing school” for young ladies in the 20th century. She also would have been tutored in the needle arts. The concept was to teach proper young ladies the arts as part of an appreciation for the “finer things” in life. This would prepare them for a suitable marriage and help them take their place in refined society.

In the academies, young women were taught to copy from artistic models for their work. In this case, Mehetabel Wingate copied a print engraved by Enoch G. Grindley titled in Latin “Pater Patrae” (“Father of the Country”) and printed in 1800, just after Washington’s death in 1799. Undoubtedly, she saw the print and was skilled enough to copy it in color. The image of the soldier weeping in front of the massive monument to Washington is impressive. Also impressive are the angels or cherubs holding garlands, and women dressed up as classical goddesses, grieving. One of the goddesses holds a portrait of Washington. Of course, the inscriptions tout many of Washington’s accomplishments. Mehetabel Wingate was a talented artist and ambitious in undertaking a composition as complicated as this one.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for Mehetabel Bradley Wingate, by her daughter Mehetabel Wingate, 1796 / THF237513

Fortunately, The Henry Ford owns two additional works made by Mehetabel Wingate (1772–1846). From these, we can learn a bit about her life and her family. This remarkably preserved watercolor painting memorializes her mother, also named Mehetabel, who died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1796. Young Mehetabel, who would have been 24 in 1796, is shown mourning in front of a grave marker, which is inscribed. Although it is simplified, she wears a fashionable dress in the most current style. Around her is an idealized landscape, which includes a willow tree, or “weeping” willow, on the left, which symbolized sadness. On the right is a pine tree, which symbolized everlasting life. In the background is a group of buildings, perhaps symbolizing the town, including the church, which represented faith and hope. These are standard images seen in many, if not most, American memorial pictures. Mehetabel Wingate undoubtedly learned these conventions in the young girls’ academy in her hometown of Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Women in Classical Dress, 1790-1810, by Mehetabel Wingate / THF152522

The painting, above, while not a memorial painting, shows us how young ladies in the academies learned how to paint. Mehetabel seems to be practicing poses and angles, as the young ladies dressed as classical goddesses reach out to each other. It likely pre-dates both works previously shown and may have been done as a classroom exercise. As such, it is a remarkable survival.

In memory of Freeman Bartlett Jr. who died in Calcutta November the 1st 1817, aged 19 years, by Eliza T. Reed, about 1818 / THF14816

This example, painted later than Mehetabel Wingate’s work, shows the same conventions: a grieving female in front of a tomb with an inscription about the dearly departed—in this case, a young man who died at the tender age of 19 in far-off Calcutta. We also see the idealized landscape with the “weeping” willow tree and the church in the background.

Memorial Painting for Elijah and Lucy White, unknown artist, circa 1826 / THF120259

The painting above, done a few years later, shows some of the variations possible in memorial pictures. Unlike the previous examples, painted on paper, this was painted on expensive, white silk. It commemorates two people, Elijah and Lucy White, presumably husband and wife, who both died in their sixties. We see the same imagery here as before, although the trees, other than the “weeping” willows, are so abstract as to be difficult to identify.

Memorial Painting for Sarah Burgat, J. Preble, 1826 / THF305542

The example above represents a regional approach to memorial paintings. German immigrants to Pennsylvania in the late 1700s and early 1800s brought an interesting, stylized approach to their memorial paintings that have come to be known as “Fraktur.” The urn that would be seen on top of the monument in the previous examples now takes center stage, and is surrounded by symmetrically arranged birds. What we are seeing here is a combination of New England imagery, such as the urn, with Pennsylvania German imagery, such as the stylized birds. We know that this work was made in a town called Paris, as the artist, J. Preble, signed it in front of her name. There are two possible locations for Paris—one in Stark County, Ohio, and the other in Kentucky. Both had sizeable German immigrant populations in the 1820s. As America was settled and people moved west in the early 19th century, cultural practices melded and merged.

By the 1840s and 1850s, the concept of the memorial painting came to be viewed as old-fashioned. The invention of photography revolutionized the way folks could save representations of loved ones and friends. By the middle of the 19th century, these paintings were viewed as relics from the past. But in the early 20th century, collectors like Henry Ford recognized the historic and artistic value of these works and began to collect them. As a uniquely American art, they provide insight into the values of Americans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, 19th century, 18th century, women's history, presidents, paintings, making, home life, holidays, education, by Charles Sable, art

The Incredible Life of Frederick Douglass

The story of Frederick Douglass’s life is, at turns, tragic and awe-inspiring. He is a testament to the strength and ingenuity of the human spirit. The Henry Ford is fortunate to have some materials related to Douglass, as well as to the many areas of American history and culture he touched. What follows is an exploration of Frederick Douglass’s story through the lens of The Henry Ford’s collection, using our artifacts as touchpoints in Douglass’s life.

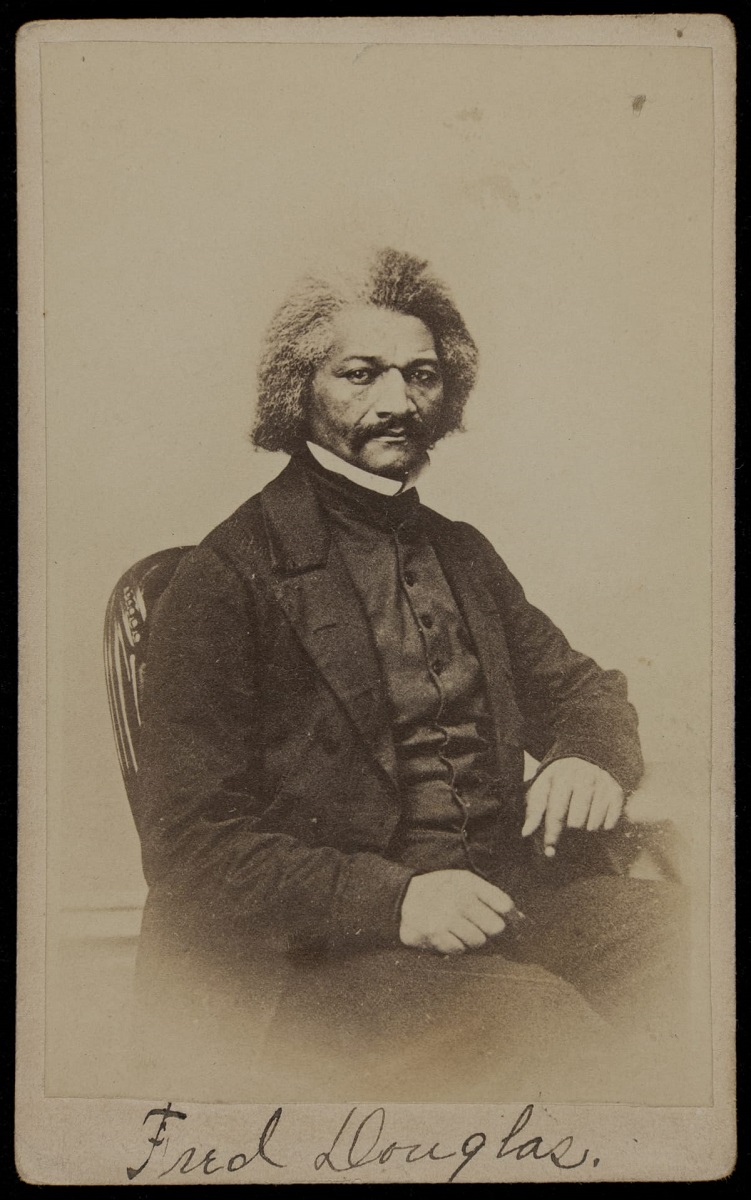

This portrait of Douglass was taken circa 1860, around the time Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States. / THF210623

Early Life & Escape

Born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, Frederick Douglass was named Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey by his enslaved mother, Harriet Bailey. Tragically, Douglass only saw his mother a few times before her early death, when Douglass was just seven years old. Though he had few memories of his mother, he recalled her fondly and was proud to learn that she also knew how to read. He wrote that he was “quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess” to his mother. Few enslaved people could read at that time—Douglass’s pride in his mother was certainly justified.

In 1826, Douglass was sent to Baltimore, Maryland, to live with the family of Hugh and Sophia Auld—extended family of his master, Aaron Anthony. This move to Baltimore would be transformative for Douglass. It not only exposed Douglass to the wider world, but was also where Douglass learned to read.

Douglass was initially taught to read by Sophia Auld, who considered him a bright pupil. However, the lessons were put to a stop by Hugh Auld. It was not only illegal to teach an enslaved person to read, but Hugh also believed literacy would “ruin” Douglass as a slave. In a sense, Douglass agreed, as he came to understand the vast power of literacy. Douglass would later remark that “education and slavery are incompatible with each other.”

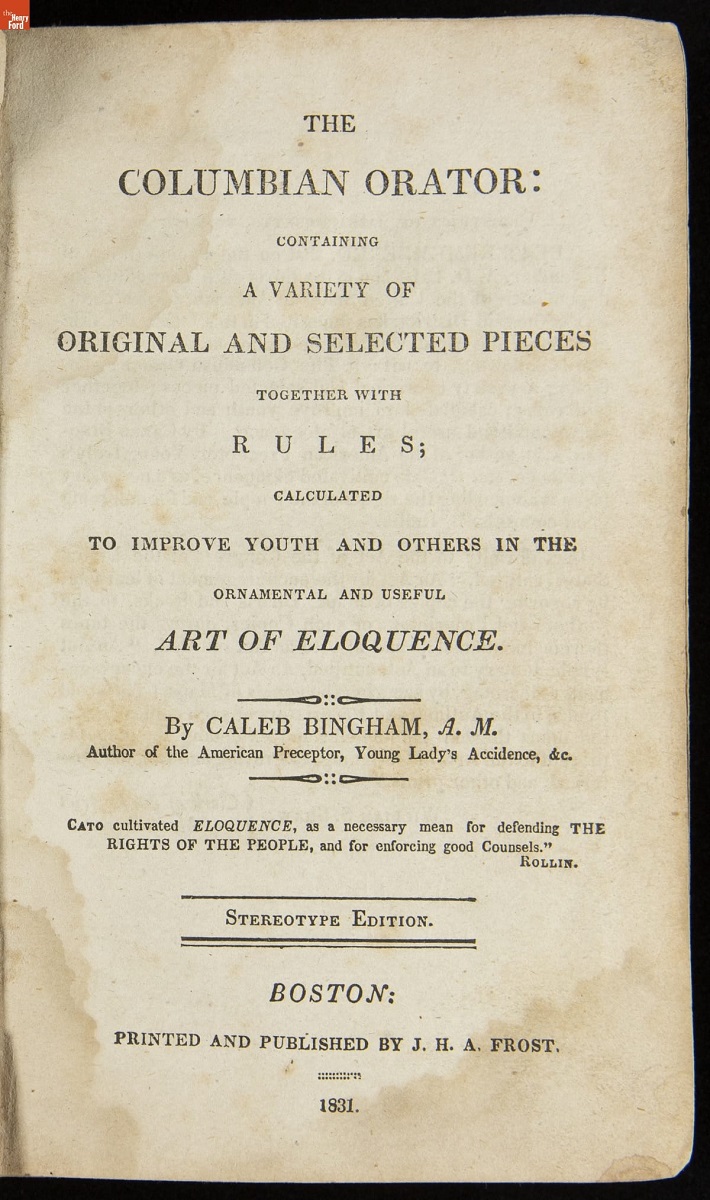

Douglass was determined to read. He “converted to teachers” some of the friendlier white children in the neighborhood. They showed him a school reader entitled The Columbian Orator, by Caleb Bingham, that he came to rely upon. In 1830, he purchased his own copy for 50 cents. The book—a collection of exceptional oration, poems, dialogue, and tips on the “art of eloquence”—became a great inspiration to Douglass. He carried it with him for many years to come.

“The Columbian Orator” features a discussion between an enslaved person and their master which impressed Douglass. The enslaved person’s dialogue—referred to as “smart” by Douglass—resulted in the man’s unexpected emancipation. / THF621972, THF621973

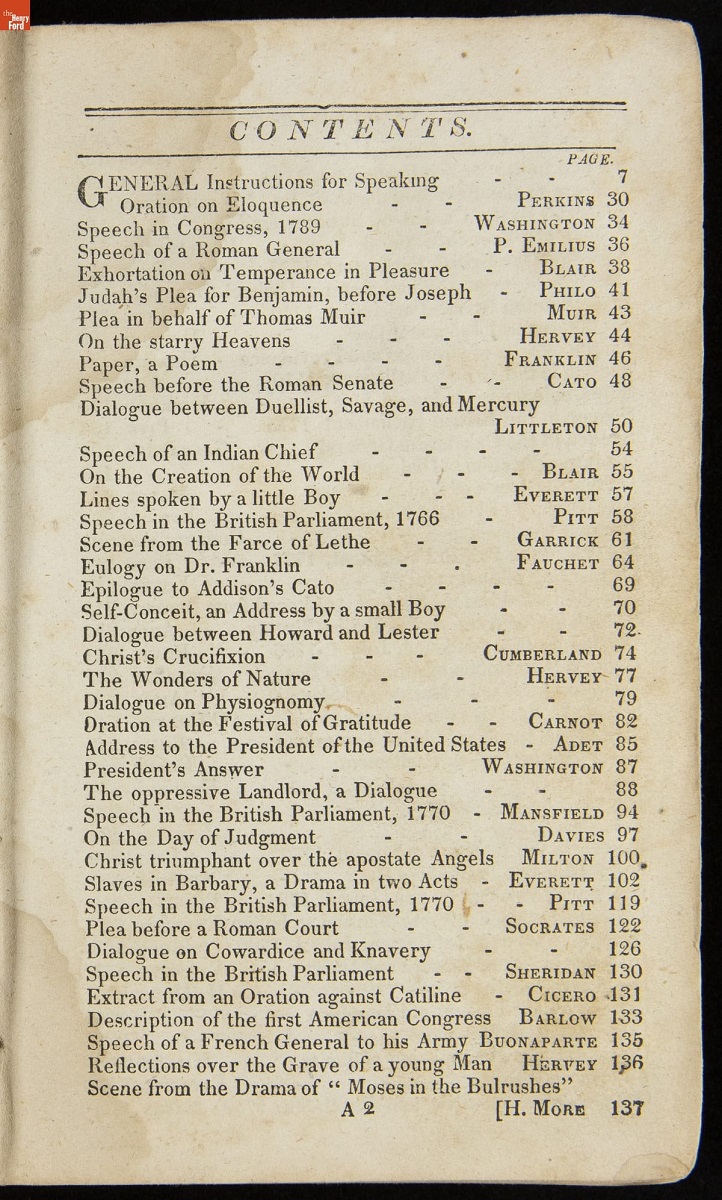

As recollected in his first memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, published in 1845, Douglass’s teenage years were some of his most challenging. He became viewed as a “troublemaker.” He was hired out to different farmers in the area, including one who had the reputation as an “effective slave breaker” and was especially cruel. Knowing that a larger world awaited and facing a terrible quality of life, Douglass attempted an escape in 1836. The escape failed and he was put in jail. Douglass was surprised to be released. He was sent not to the deep South as he had feared, but instead, back to Baltimore and the family of Hugh Auld, to learn the trade of caulking at the shipyards. While working there, Douglass was subjected to the animosities of his white coworkers, who beat him mercilessly—and were never arrested for it because a white witness would not testify and the word of a Black man was not admissible. He continuously dreamt of escape.

In this first memoir, Douglass provides great detail into his early life. However, because he was still a fugitive at the time of publication, he omitted details related to his escape. / THF8133

Recalling the ships on Chesapeake Bay, Douglass wrote:

“Those beautiful vessels, robed in purest white, so delightful to the eye of the freemen, were to me so many shrouded ghosts, to terrify and torment me with thoughts of my wretched condition. You are loosed from your moorings and are free; I am fast in my chains and am a slave! You move merrily before the gentle gale, and I sadly before the bloody whip!”

The ships’ freedom taunted him.

On September 3rd, 1838, Douglass courageously escaped slavery. Dressed as a sailor and using borrowed documents, he boarded a train, then a ferry, and yet another train to reach New York City—and freedom. His betrothed, Anna Murray Douglass, a free Black woman, followed, and soon after they were married. Frederick and Anna Murray Douglass moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, with hopes that Frederick could find work as a caulker in the whaling port. Instead, he took on a variety of jobs—but, finally, the money he earned was fully his. It is believed that Anna Murray Douglass played a crucial role in supporting Frederick's escape. Their shared commitment to freedom made them a formidable team in the fight against slavery.

The American Anti-Slavery Society & the Abolitionists

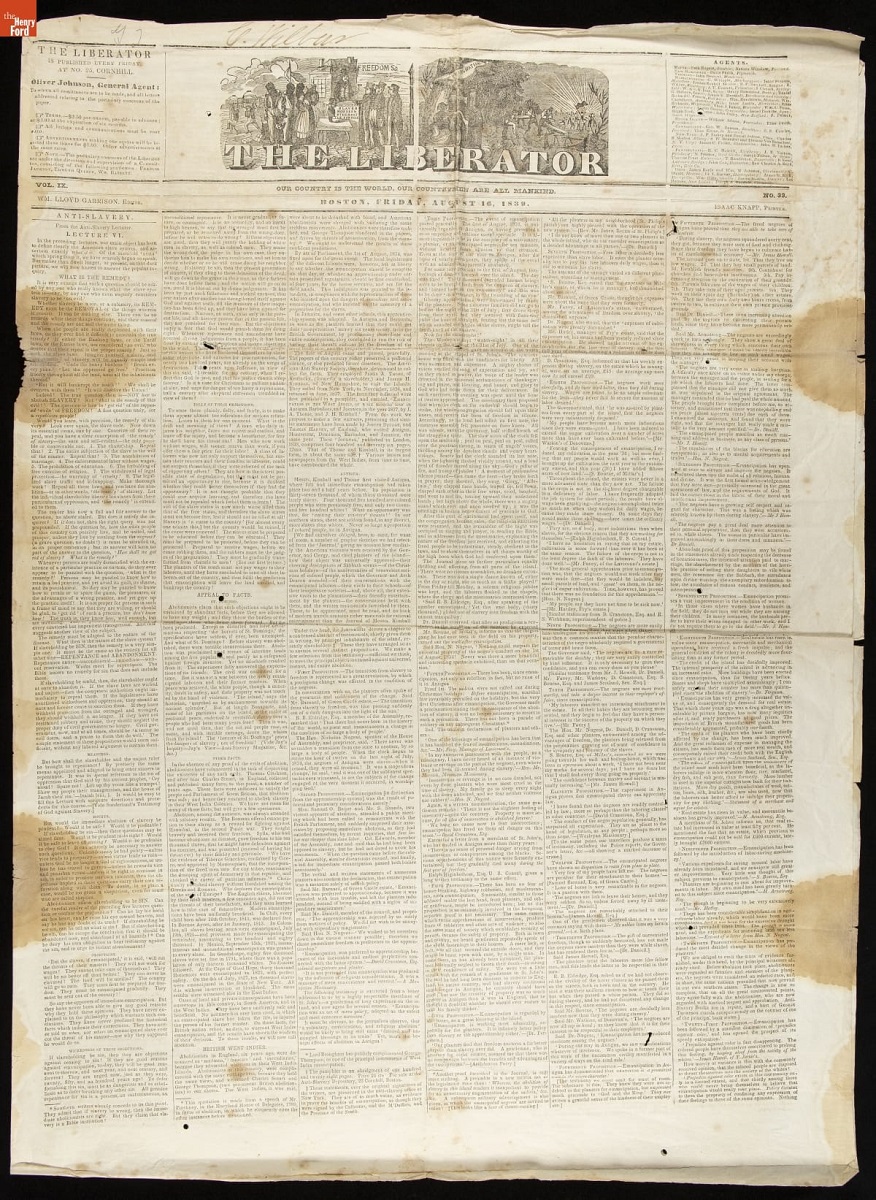

While living in New Bedford, Douglass encountered William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, for the first time. Douglass later wrote that the paper “took its place with me next to the Bible.” The Liberator introduced to Douglass the official abolitionist movement. This was a pivotal moment in his journey to becoming a prominent abolitionist leader.

In August of 1841, Douglass attended an abolitionist convention. In an impromptu speech, he regaled the audience with stories of his enslaved past. William Lloyd Garrison and other leading abolitionists noticed—Douglass’s career as an abolitionist orator had begun. Douglass became a frequent speaker at meetings of the American Anti-Slavery Society. His personal story of life enslaved humanized the abolitionist movement for many Northerners—and eventually, the world. His powerful speeches resonated deeply, inspiring many to join the cause.

In 1845, he published his first memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. By 1847, it had already sold more than 11,000 copies! This would be followed by two more memoirs: My Bondage and Freedom in 1855 and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in 1881. These narratives became essential texts in the abolitionist movement and the aftermath of the Civil War, providing firsthand accounts of the horrors of slavery.

This copy of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator was published on August 16, 1839—around the time when Douglass first encountered the paper. / THF621979

Women’s Suffrage

Douglass was also supportive of the women’s suffrage movement. He spoke at the famous Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 in support of women’s rights. In fact, the motto of his newspaper, The North Star, was “Right is of no sex—Truth is of no color—God is the Father of us all, and we are brethren.”

While Douglass forcefully supported women’s suffrage, some of his actions put him at odds with others in the movement. He supported the adoption of the 14th amendment, ratified in 1868, which guaranteed equality to all citizens—which included Black and white males, including the formerly enslaved. It did not include women. He also supported adoption of the 15th amendment, ratified in 1870, which secured Black males voting rights. Again, the amendment excluded women. Although a dedicated women’s rights activist, Douglass supported the adoption of the 14th and 15th amendments as he believed the matter to be “life or death” for Black people. This put him in disagreement with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, two of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement, as well as his friends. Despite this disagreement about timing, Douglass would continue to lecture in support of women’s equality and suffrage until his death.

John Brown’s Raid

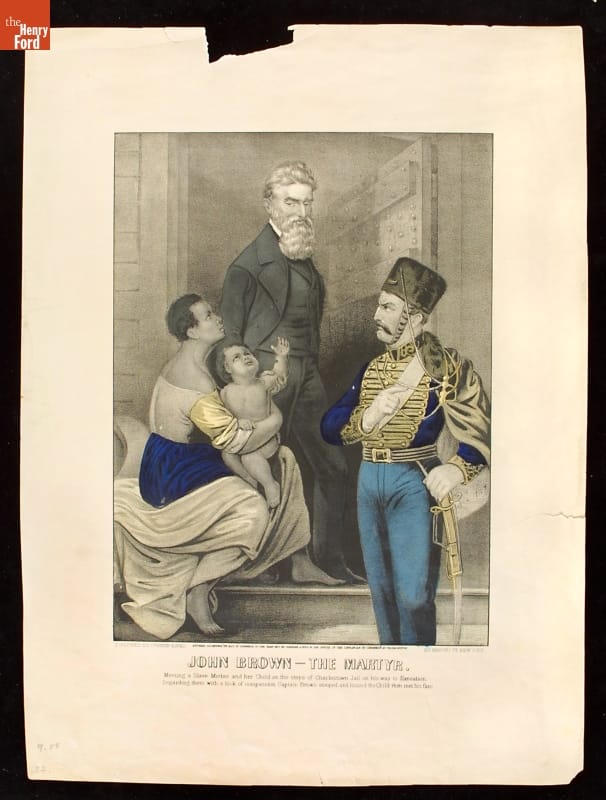

Douglass was well-acquainted with famous abolitionist leader John Brown, first meeting him in 1847 or 1848. Brown became known for leading a raid on the armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, intending to create an “army of emancipation” to liberate enslaved people. Douglass and Brown spoke shortly before John Brown’s raid. Brown had hoped that Douglass would join him, but Douglass declined. He believed that Brown was “going into a perfect steel trap, and that once in he would not get out alive.”

Douglass was right. Brown was captured during the raid and was subsequently tried, convicted, and executed. Brown became seen as an anti-slavery martyr, as the below print shows. Henry David Thoreau remarked about him, “No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature…”

A letter from Douglass was found among John Brown’s belongings, leading to warrants for Douglass’s arrest as a conspirator. He was lecturing in Philadelphia at the time of the discovery. John Hurn, Philadelphia’s telegraph operator, was sympathetic to the abolitionist cause. He received a dispatch for the sheriff calling for Douglass’s arrest and both sent a warning to Douglass and delayed relaying the dispatch to the sheriff. Douglass fled and made it to Canada, narrowly escaping arrest. He then went abroad on a lecture tour, resisting apprehension in the States.

The text on this Currier & Ives print reads “John Brown—The Martyr: Meeting a Slave Mother and her Child on the steps of Charlestown Jail on his way to Execution. Regarding them with a look of compassion Captain Brown stooped and kissed the Child then met his fate." This did not actually occur, but became popular lore, as well as the subject of artwork and literature. / THF8053

The Civil War & Abraham Lincoln

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. At the time, Douglass was not optimistic about the cause of abolition under Lincoln’s presidency. As tensions between the North and South grew and Civil War loomed, Douglass welcomed the impending war. As biographer David Blight states, “Douglas wanted the clarity of polarized conflict.”

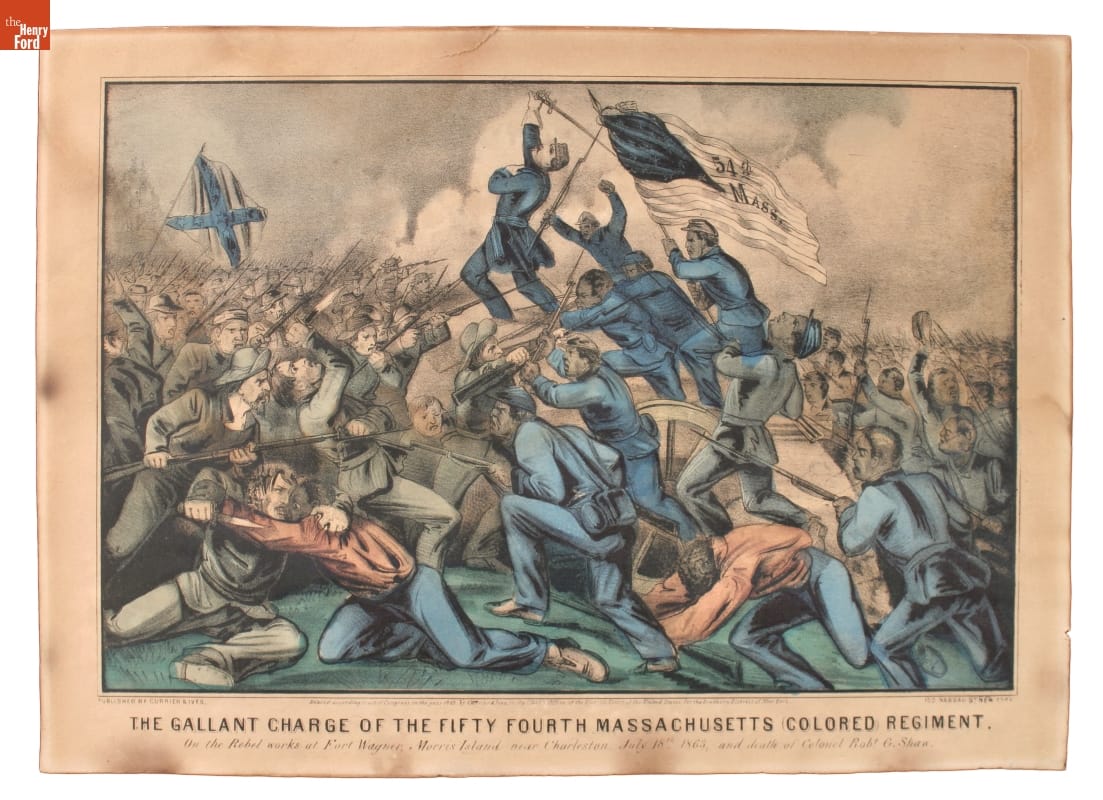

Douglass got involved in the war effort through the recruitment of Black soldiers. Two of his sons, Charles and Lewis, joined the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the second Black regiment in the Union Army. Douglass first met President Abraham Lincoln in August 1863, when he visited the White House to discuss grievances against Black troops. Even without an appointment and a room full of people waiting, Douglass was admitted to see Lincoln after just a few minutes.

Two of Frederick Douglass’s sons, Lewis and Charles, fought with the 54th Massachusetts Colored Regiment. Lewis Douglass was appointed Sergeant Major, the highest rank that a Black person could then hold. / THF73704

Douglass would go on to advise Lincoln over the following years. After Lincoln’s second inaugural address, he asked Douglass his thoughts about it, adding, “There is no man in these United States whose opinion I value more than yours.”

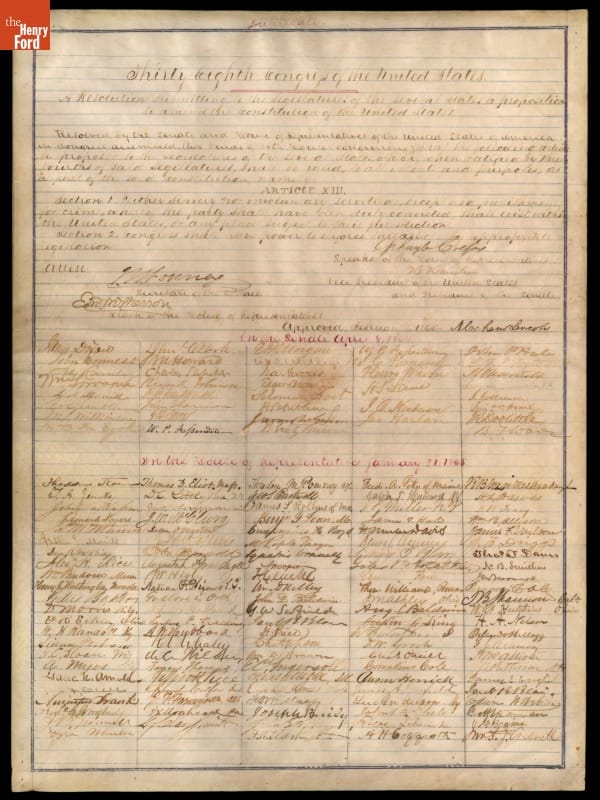

On February 1, 1865, Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of the United States Congress proposing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution—the “nail in the coffin” for the institution of slavery in the United States. But before the 13th Amendment could be ratified, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on April 15, 1865. While Douglass and Lincoln certainly disagreed on many topics, Douglass remembered him fondly. In his eulogy, Douglass called Lincoln “the Black man’s president: the first to show any respect to their rights as men.”

After the Civil War and even after Reconstruction, Douglass held high-ranking government appointments—often becoming the first Black person to do so. Douglass was appointed the Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti in 1889.

While Douglass certainly supported the 13th Amendment’s abolition of slavery, he did not think it went far enough. He remarked, “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot. While the legislatures of the south retain the right to pass laws making any discrimination between black and white, slavery still lives there.” / THF118475

Douglass continued to lecture in support of his two primary causes—racial equality and women’s suffrage—until the very end. On February 20, 1895, he attended a meeting of the National Council of Women, went home, and suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 77 years old.

Frederick Douglass remains one of the most inspirational figures in American history. We can still feel the weight of the words he wrote and spoke, more than 125 years after his passing. Douglass said, “Memory was given to man for some wise purpose. The past is … the mirror in which we may discern the dim outlines of the future and by which we may make it more symmetrical.” This work continues.

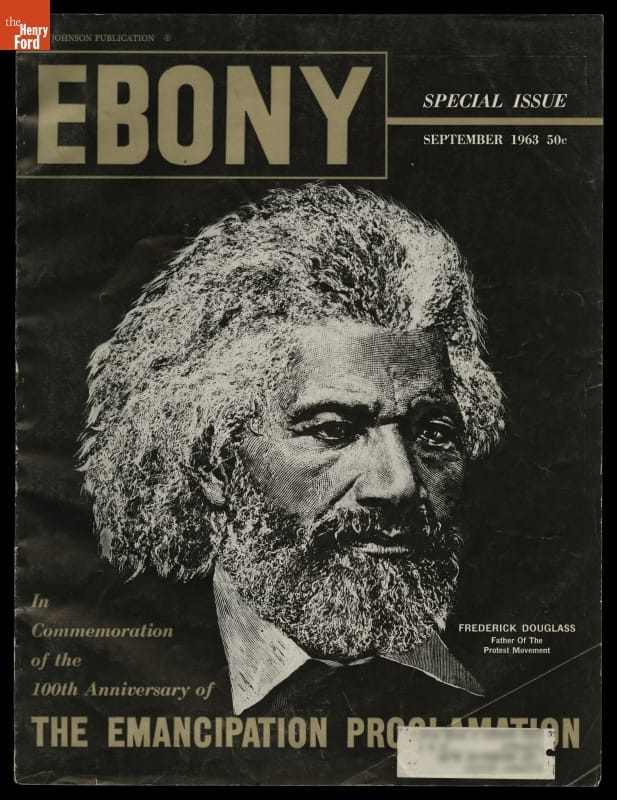

Frederick Douglass remains a powerful symbol of the fight for racial justice and equality. Here, his image graces the cover of Ebony Magazine’s issue celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. / THF98736_REDACTED

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. She appreciated the recently published book by David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, as she conducted research for this post.

Maryland, women's history, voting, Massachusetts, education, Civil War, Civil Rights, by Katherine White, books, African American history, Abraham Lincoln, 19th century, #THFCuratorChat

An Artifact Love Story, Featuring the Wizard of Oz

My name is Shannon Rossi, and I’m a Collections Specialist, Cataloger, for archival items. I started at The Henry Ford as a Simmons Intern in 2018, and have been a Collections Specialist since March 2019. Anyone who knows me knows that I love The Wizard of Oz. It is my favorite film. I collect Oz memorabilia and am a member of The International Wizard of Oz Club.

The artifact I’m going to talk about here is related to The Wizard of Oz. But it’s not the artifact you might expect.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, first edition, 1900 / THF135495

On my second day as a Simmons intern in 2018, Sarah Andrus, Librarian at The Henry Ford, showed me a beautiful first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. The little girl who used to dance around the house singing “We’re Off to See the Wizard” rejoiced when I was able to hold that book in my hands. In my own collection of Oz memorabilia, I have a 1939 edition, but this was another experience entirely.

Last year marked the 80th anniversary of the 1939 musical starring Judy Garland. I signed up to do a History Outside the Box presentation to commemorate the anniversary. History Outside the Box allows us to showcase some of our archival items that visitors to The Henry Ford might not otherwise get a chance to see. In addition to the first edition book, I knew we had some fantastic Oz artifacts in our collection. We have copies of the special edition TV Guides that came out in July 2000, each with one of the main characters on the cover. We have sheet music for “We’re Off to See the Wizard” and “Over the Rainbow,” a coloring book from the 1950s, an original 1939 advertisement for the film an issue of Life magazine, and a photograph of Bert Lahr (the Cowardly Lion) when he visited Greenfield Village in the 1960s.

Bert Lahr Signing Autographs during a Visit to Greenfield Village, August 22, 1966 / THF128032

The artifact I want to talk about isn’t as famous or recognizable as anything I listed above. You pretty much have to be a diehard Oz fan (or have worked on acquiring, cataloging, or digitizing this item—which I did not) to even associate much meaning with it.

While browsing our collections for archival items to use in my History Outside the Box presentation, I found a theater program from the 1903 musical production of The Wizard of Oz at the Boston Theatre. (Be honest, how many of you knew that the 1939 film wasn’t the first musical production of Oz?)

Theater Program, "The Wizard of Oz," Boston Theatre, Boston, Massachusetts, 1903 / THF93092

We’ve established that I am a huge Oz fan. I knew about this production, as well as several of the early film productions (check them out if you get a chance!), but I had never seen a program from the show. This program is not visually spectacular. It is black and white. The vivid colors and magical illustrations from W.W. Denslow that are featured in the Oz first edition are conspicuously absent. In fact, the only illustration that anyone might associate with Oz is on the cover, which features a beautiful illustration of the Cowardly Lion about to fall asleep among a field of poppies that create a border around the page.

The story and lyrics for this musical adaptation was written by L. Frank Baum, but not all of it would seem familiar. We’d see, of course, Dorothy, the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and the Wizard. The Cowardly Lion, however, cannot speak, as he does in the book and almost every later adaption, nor does he ever befriend Dorothy. Dorothy’s house doesn’t land on any Wicked Witch. Nor does she receive any magical slippers (silver, as in the book, or ruby, as in the movie). Even our favorite precocious Cairn Terrier, Toto, is missing from this story. Toto is replaced by a cow named Imogene, who serves as Dorothy’s Kansas companion.

The cast list for Act I in the program includes Dorothy Gale and “Dorothy’s playmate,” the cow Imogene. / THF141760

The action in Oz has to do with political tensions between the Wizard and Pastoria, the King of Oz (who does appear in later Oz books). In fact, even real-life politicians and notable members of society at the time, including Theodore Roosevelt and John D. Rockefeller, were mentioned in the script.

The Boston Theatre production that audiences saw in November 1903 featured songs by composer Paul Tietjens, who had approached L. Frank Baum about creating an Oz musical as early as March 1901. Tietjens wasn’t exactly famous, but the play did feature some well-known actors of the early 20th century.

Most importantly, there are two names in the program that stand out: Fred Stone and David Montgomery. The two actors were paired on stage in many vaudeville shows. The pair played the Scarecrow and Tin Man in this musical adaptation. Later, when Ray Bolger was cast as the Scarecrow in the 1939 musical, he would credit Stone with inspiring his “boneless” style of dance and movement as the character.

Page seven of the program lists actors Fred A. Stone as the Scarecrow and David C. Montgomery as the Tin Woodman / THF141761

I’m grateful that this artifact was digitized. It’s not something you see or hear about very often, but it has a lot of power for Oz fans like me. That’s the power of digitization—the impact of a digitized artifact doesn’t have to reach huge audiences, if it reaches a smaller but enthusiastic audience. Digitization can allow us to marvel (slight pun about Professor Marvel in the 1939 musical definitely intended…) at an object we know exists somewhere out in the world, but have never seen before.

Continue Reading

Massachusetts, music, 20th century, 1900s, popular culture, digitization, digital collections, by Shannon Rossi, books, archives, actors and acting, #digitization100K

Inventing America’s Favorite Cookie

Many of us have been baking a bit more than usual while staying at home. So, let’s take look at how America’s favorite cookie, the chocolate chip, was born.

Before we get to chocolate chips, let’s talk chocolate. It’s made from the beans of the cacao tree and was introduced by the Aztec and Mayan peoples to Europeans in the late 1500s. Then a dense, frothy beverage thickened with cornmeal and flavored with chilies, vanilla, and spices, it was used in ancient ceremonies.

Map of the Americas, 1550. THF284540

Colonial Americans imported cacao from the West Indies. They consumed it as a hot beverage, made from ground cacao beans, sugar, vanilla and water, and served it in special chocolate pots.

Chocolate Pot, 1760-1790 THF145291

In the 1800s, chocolate made its way into an increasing number of foods, things like custards, puddings, and cookies, and onto chocolate-covered candy. It was not just for drinking anymore!

Trade Card, Granite Ironware, 1880-1890 THF299872

Today, most Americans say chocolate is their favorite flavor. Are you a milk or dark chocolate fan? My vote? Dark chocolate.

Cookies were special treats into the early 1800s; sweeteners were costly and cookies took more time and labor to make. Imagine easing them in and out of a brick fireplace over with a long-handled peel.

Detail of late 18th century kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. See the kitchen for yourself with this virtual visit.

As kitchen technology improved in the early 1900s, especially the ability to regulate oven temperature, America’s cookie repertoire grew.

Detail of 1930s kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. See the kitchen yourself with this virtual visit.

Until the 1930s, baking chocolate was melted in a double boiler before being added to cookie dough. Check out this 1920 recipe for Chocolate Mousse from our historic recipe bank.

Then came Ruth Graves Wakefield and the chocolate chip cookie. Ruth, a graduate of the Framingham State Normal School of Household Arts, had taught high school home economics and had worked as a dietitian.

Image: "Overlooked No More: Ruth Wakefield, Who Invented the Chocolate Chip Cookie" from The New York Times

In 1930, 27-year-old Ruth and her husband Kenneth opened a restaurant in Whitman, Massachusetts called the Toll House Inn. The building had never been a toll house, but was located on an early road between Boston and New Bedford. The restaurant would grow from seven tables to 60.

Toll House Inn business card, 1930s. THF183299

A quick aside: our 1820s Rocks Village Toll House in Greenfield Village. Early travelers paid tolls to use roads or cross bridges. This one collected fares for crossing the Merrimack River.

Rocks Village, Massachusetts toll house in Greenfield Village. THF2033

With Ruth Wakefield’s background in household arts, she was well-prepared to put together a menu for her restaurant. It was a great location. The Toll House Inn served not only the locals, but people passing through on their way between Boston and Cape Cod.

Toll House Inn business card, 1930s. THF18330

Over time, Ruth’s reputation grew, and the restaurant became well-known for her skillful cooking, wonderful desserts, and excellent service. On the back of this circa 1945 Toll House Inn postcard, a customer wrote: “…down here two weeks ago & had a grand dinner.”

Toll House Inn postcard, about 1945. THF183298

Ruth Wakefield, curious and willing to experiment, liked to create new dishes and desserts to delight her customers. The inn had been serving a butterscotch cookie--which everyone loved--but Ruth wanted to “give them something different.”

About 1938, Ruth had an inspiration. She chopped up a Nestle’s semisweet chocolate bar with an ice pick and stirred the bits into her sweet butter cookie batter. The chocolate bits melted--and didn’t spread, remaining in chunks throughout the dough.

Recipe Booklet, "Favorite Chocolate Recipes made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate," 1940. THF125196

Legend has it that the cookies were an accident--that Ruth had expected to get all-chocolate cookies when the chocolate melted. One of those “creation myths?” A great marketing tale? Ruth was a meticulous cook and food science savvy. She said it was a deliberate experiment.

The marriage of sweet, buttery cookie dough and semisweet chocolate was a hit--the cookies quickly became popular with guests. Ruth shared the recipe when asked. Local newspapers published it. And she included it in the 1938 edition of her “Tried and True Recipes” cookbook.

The Toll House, Whitman, Massachusetts, circa 1945. THF183297

Nestle’s saw sales of its semisweet chocolate bar jump dramatically in New England--especially after the cookie was featured on a local radio show. When Nestle discovered why, they signed a contract with Ruth Wakefield, allowing Nestle to print the recipe on every package.

Nestle’s truck, 1934. Z0001194

Nestle began scoring its semisweet chocolate bar, packaging it with a small chopper for easy cutting into morsels. The result was chocolate “chips”--hence the name.

Recipe Booklet, "Favorite Chocolate Recipes made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate," 1940. THF125194

In 1939, Nestle introduced semisweet morsels. Baking Toll House Cookies became even more convenient, since you didn’t have to cut the chocolate into pieces.

Toll House Cookies and Other Favorite Chocolate Recipes Made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate, 1941. THF183303

Nestle included the Toll House Cookie “backstory” and the recipe in booklets promoting their semisweet chocolate.

During World War II, Nestle encouraged people to send Toll House Cookies to soldiers. For many, it was their first taste of a chocolate chip cookie--its popularity spread beyond New England.

Advertisement, "His One Weakness, Toll House Cookies from Home" November 1943. THF183306

The homemaker in this 1940s Nestle’s ad celebrates her success as a hostess when serving easy-to-make Toll House Cookies. Chocolate chips would, indeed, soon become our “national cookie.”

They Never Get Enough of My Toll-House Cookies!, 1945-1950. THF183304

Chocolate chip morsels were a great idea, so other companies followed suit.

Recipe Leaflet, "9 Famous Recipes for Hershey's Semi-Sweet Chocolate Dainties," 1956. THF295928

Other delectable treats, like these “Chocolate Refresher” bars shown in this 1960 ad, can be made with chocolate morsels. The possibilities are endless.

Nestle's Semi-Sweet Morsels Advertisement, "Goody for You," 1960. THF43907

More from The Henry Ford: Enjoy a quick “side trip” to this blog about more American chocolate classics.

Holiday baking is a cherished tradition for many. Chocolate chip cookies are frequently a key player in the seasonal repertoire. Hallmark captured holiday baking memories in this ornament.

Hallmark "Christmas Cookies" Christmas Ornament, 2004. THF177747

The museum’s 1946 Lamy’s Diner serves Toll House Cookies. Whip up a batch of chocolate chips at home and enjoy a virtual visit.

Cookie dough + chocolate chips = America’s favorite cookie! It may have been simple, but no one else had ever tried it before! Hats off to Ruth Wakefield!

Toll House Cookies and Other Favorite Chocolate Recipes Made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate, 1941. THF183301

After all this talk of all things chocolate, are you ready for a cookie? This well-known cookie lover probably is!

Cookie Monster Toy Clock, 1982-1986. THF318447

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Massachusetts, 1930s, 20th century, women's history, restaurants, recipes, food, entrepreneurship, by Jeanine Head Miller, #THFCuratorChat

New Acquisition: LINC Computer Console

A LINC console built by Jerry Cox at the Central Institute for the Deaf, 1964.

There are many opinions about which device should be awarded the title of "the first personal computer." Contenders range from the well-known to the relatively obscure: the Kenbak-1 (1971), Micral N (1973), Xerox Alto (1973), Altair 8800 (1974), Apple 1 (1976), and a few other rarities that failed to reach market saturation. The "Laboratory INstrument Computer" (aka the LINC) is also counted among this group of "firsts." Two original examples of the main console for the LINC are now part of The Henry Ford's collection of computing history.

The LINC is an early transistorized computer designed for use in medical and scientific laboratories, created in the early-1960s at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory by Wesley A. Clark with Charles Molnar. It was one of the first machines that made it possible for individual researchers to sit in front of a computer in their own lab with a keyboard and screen in front of them. Researchers could directly program and receive instant visual feedback without the need to deal with punch cards or massive timeshare systems.

These features of the LINC certainly make a case for its illustrious position in the annals of personal computing history. For a computer to be considered "personal," the device must have had a keyboard, monitor, data storage, and ports for peripherals. The computer had to be a stand-alone device, and above all, it had to be intended for use by individuals, rather than the large "timeshare" systems often found in universities and large corporations.

The inside of a LINC console, showing a network of hand-wired and assembled components.

Prototyping

In 1961, Clark disappeared from the Lincoln Lab for three weeks and returned with a LINC prototype to show his managers. His ideal vision for the machine was centered on user friendliness. Clark wanted his machine to cost less than $25,000, which was the threshold a typical lab director could spend without needing higher approval. Unfortunately, Clark’s budget goal wasn’t reached—when commercially released in 1964, each full unit cost $43,000 dollars.

The first twelve LINCs were assembled in the summer of 1963 and placed in biomedical research labs across the country as part of a National Institute of Health-sponsored evaluation program. The future owners of the machines—known as the LINC Evaluation Program—travelled to MIT to take part in a one-month intensive training workshop where they would learn to build and maintain the computer themselves.

Once home, the flagship group of scientists, biologists, and medical researchers used this new technology to do things like interpret real-time data from EEG tests, measure nervous system signals and blood flow in the brain, and to collect date from acoustic tests. Experiments with early medical chatbots and medical analysis also happened on the LINC.

In 1964, a computer scientist named Jerry Cox arranged for the core LINC team to move from MIT to his newly formed Biomedical Computing Laboratory at Washington University at St. Louis. The two devices in The Henry Ford's recent acquisition were built in 1963 by Cox himself while he was working at the Central Institute for the Deaf. Cox was part of the original LINC Evaluation Board and received the "spare parts" leftover from the summer workshop directly from Wesley Clark.

Mary Allen Wilkes and her LINC "home computer." In addition to the main console, the LINC’s modular options included dual tape drives, an expanded register display, and an oscilloscope interface. Image courtesy of Rex B. Wilkes.

Mary Allen Wilkes

Mary Allen Wilkes made important contributions to the operating system for the LINC. After graduating from Wellesley College in 1960, Wilkes showed up at MIT to inquire about jobs and walked away with a position as a computer programmer. She translated her interest in “symbolic logic” philosophy into computer-based logic. Wilkes was assigned to the LINC project during its prototype phase and created the computer's Assembly Program. This allowed people to do things like create computer-aided medical analyses and design medical chatbots. In 1964, when the LINC project moved from MIT to the Washington University in St. Louis, rather than relocate, Wilkes chose to finish her programming on a LINC that she took home to her parent’s living room in Baltimore. Technically, you could say Wilkes was one of the first people in the world to have a personal computer in her own home.

Wesley Clark (left) and Bob Arnzen (right) with the "TOWTMTEWP" computer, circa 1972.

Wesley Clark

Wesley Clark's contributions to the history of computing began much earlier, in 1952, when he launched his career at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory. There, he worked as part of the Project Whirlwind team—the first real time digital computer, created as a flight simulator for the US Navy. At the Lincoln Lab, he also helped create the first fully transistorized computer, the TX-0, and was chief architect for the TX-2.

Throughout his career, Clark demonstrated an interest in helping to advance the interface capabilities between human and machine, while also dabbling in early artificial intelligence. In 2017, The Henry Ford acquired another one of Clark's inventions called "The Only Working Turing Machine There Ever Was Probably" (aka the "TOWTMTEWP")—a delightfully quirky machine that was meant to demonstrate basic computing theory for Clark's students.

Whether it was the “actual first” or not, it is undeniable that the LINC represents a philosophical shift as one of the world’s first “user friendly” interactive minicomputers with consolidated interfaces that took up a small footprint. Addressing the “first” argument, Clark once said: "What excited us was not just the idea of a personal computer. It was the promise of a new departure from what everyone else seemed to think computers were all about."

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

Missouri, women's history, technology, Massachusetts, computers, by Kristen Gallerneaux, 20th century, 1960s, #THFCuratorChat

Lamy’s Diner Gets a Makeover

Where can you get a real diner experience, especially here in Michigan? The answer is Lamy’s Diner inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation—an actual 1946 diner brought here from Massachusetts, restored, and operating as a restaurant in the Museum since 2012.

Now Lamy’s Diner is more authentic, more immersive, and serving more delicious food than ever! What’s behind this makeover?

In 1984, the Henry Ford Museum purchased the Clovis Lamy's diner. It took a crane to lift the diner in preparation for transporting it from Hudson, Massachusetts. Once here, it was restored to its original 1946 appearance. THF 25768

Back in the 1980s, museum staff worked with diner expert Richard Gutman to track down an intact vintage diner for the new “Automobile in American Life” exhibit. Gutman not only found such a diner in Hudson, Massachusetts (moved twice from its original location in Marlborough, Massachusetts) but also helped in its restoration and in interviewing its original owner, Clovis Lamy, about his experiences running the diner and about the menu items he served.

Diners are innovative and uniquely American eating establishments. Lamy, like other World War II veterans, was lured by dreams of prosperity and the independence that came with being an entrepreneur of his own diner. As he remarked, “during the war, everyone had his dreams. I said if I got out of there alive, I would have another diner—a brand new one.”

This photograph shows Lamy's Diner on its original site in Marlborough, Massachusetts, 1946. The diner moved three times, first to Framingham, Massachusetts, next to Hudson, Massachusetts in 1949, and finally to the Henry Ford Museum in 1984. THF88966

Sure enough, when he was discharged from the army, he ordered a 40-seat, 36- by 15-foot model from the Worcester Lunch Car Company, a premier diner builder at that time. It boasted a porcelain enamel exterior, 16 built-in stools, six hardwood booths, a marble counter, and a stainless steel back bar. Lamy could choose the diner’s colors, door locations, and outside lettering. He and his wife Gertrude visited the Worcester plant once a week, eager to check on its construction.

Clovis Lamy stands behind the counter of his diner in Massachusetts. His favorite part of running a diner was talking to his customers. THF 114397

Lamy’s Diner opened for business in April 1946, in Marlborough, Massachusetts. As Lamy remembered, business was brisk:

We jammed them in here at noon—workers from the town’s shoe shops—and we had a good dinner trade too… People stopped in after the show…[and] after the bars closed, the roof would come off the place.

During the long hours of operation (the place closed at 2 a.m.), the kitchen turned out everything from scrambled eggs to meat loaf. To Clovis Lamy, there was no better place than standing behind the counter talking to people.

But the dream had its downside. The work day was long. He was seldom able to eat with his family. After moving the diner to Framingham, Massachusetts, he sold the business in 1950. The new owner moved it down the road to Hudson.

Lamy’s Diner exterior as it looked in the Museum in 1987. THF 77241

When Clovis Lamy and his wife viewed the diner at the 1987 opening for “The Automobile in American Life” exhibition, they confirmed that it looked as good as new. “Even the sign is the same,” he remarked later with a tear in his eye.

Lamy’s Diner interior as it looked in the Museum in 1987. THF 3869

For 25 years, no food was served at Lamy’s Diner in the museum. It was interpreted as a historic structure, until the opening of the new “Driving America” exhibit in 2012, when museum staff decided to once again serve diner fare there. Delicious smells of toast and coffee wafted out of its doors, while the place hummed with activity. Museum guests sat in the booths, on stools at the counter, or at tables on the new deck with accessible seating. They could choose entrees, beverages, and desserts from a menu that was loosely inspired by diner fare of the past.

Then, in 2016, Lee Ward, the new Director of Food Service and Catering, came to me and posed the question, what if we served food and beverages at Lamy’s that more closely approximated what customers would have actually ordered here in 1946? The diner is already an authentic, immersive setting. What if we took it even further and truly transported guests to that time and place? I have always believed in the power of food to both transport guests to another era and to serve as a teaching tool to better understand the people and culture of that era. Over the years, I’ve helped create Eagle Tavern, the Cotswold Tea Experience, the Taste of History menu, the Frozen Custard Stand, and cooking programs in Greenfield Village buildings. So I excitedly responded, sure, we could certainly do that!

But, as the chefs and food service managers at The Henry Ford began to ply me with endless questions about the correct menu, recipes, and serving accoutrements for a 1946 Massachusetts diner, I realized I needed help.

Dick Gutman talking to Lamy’s staff.

Fortunately, help was forthcoming, as Richard Gutman—the diner expert who had found Lamy’s Diner for us in the 1980s—was overjoyed to return to the project and give us ideas and advice. And the 300-some diner menus he owned in his personal collection didn’t hurt either. In fact, they became our best documentation on diner foods and what they were called in 1946, as well as the graphic look of the menus.

Cookbooks of the era offered actual recipes for the dishes we saw listed on the menus, while historic images of diner interiors provided clues as to what the serving staff might wear, what kinds of dishes customers ate on, and what was displayed in the glass cases on the counter.

All of these are reflected in the current Lamy’s Diner experience. Here’s a glimpse of what you’ll encounter when you visit Lamy’s after its recent makeover:

New Lamy’s Diner menu, front and inside

Kids’ menu

New England Clam Chowder, a signature dish in New England diners and here at Lamy’s

Chicken salad sandwich, using a recipe from the 1947 edition of the Boston Cooking School Cookbook, a pioneering cookbook that offered practical recipes for the average housewife.

Meat loaf plate, using Clovis Lamy’s original meatloaf recipe

Milkshake, which in Massachusetts is a very refreshing drink made of milk, chocolate syrup, and sometimes crushed ice (no ice cream), shaken until it is creamy and frothy.

Toll House cookies, invented by a female chef named Ruth Graves Wakefield in 1938, at the Toll House Inn in Whitman, Massachusetts.

Peanut butter and marshmallow fluff sandwich, a New England specialty based upon Archibald Query’s original marshmallow creme invention and later called “Fluffernutter”

Prices are, by necessity, modern, but typical prices of the era can be found on the menu boards mounted up on the wall, based upon Lamy’s original menu and prices.

So, for a fun, immersive, and delicious experience, check out the makeover at Lamy’s Diner!

In Other Food News...

A Taste of History: Now featuring recipes and menu items guests might see prepared in Greenfield Village historical structures, such as Firestone Farm and Daggett Farmhouse.

Mrs. Fisher's Southern Cooking: The menu is based solely on Mrs. Fisher's 1881 cookbook or authentic recipes.

American Doghouse: New regional hot dog options are available, from the Detroit Coney and Chicago dogs to the California dog wrapped in bacon and avocado, tomato and arugula.

Donna R. Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford and author of this blog post, has decided that her new favorite drink is the refreshing Massachusetts version (without ice cream) of the chocolate milkshake. She thanks Richard Gutman and Lee Ward for their enthusiasm and support in making this makeover possible.

Massachusetts, 21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1980s, 1940s, restaurants, Henry Ford Museum, food, Driving America, diners, by Donna R. Braden, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Paul Revere and The Henry Ford's Tie to Tea

Examining the social and economic context of The Henry Ford's rare Paul Revere teapot. Other examples can be seen in some of the country's premier art museums. THF 166148

Today, coffee and tea are enjoyed by millions of people, including blog readers. While connoisseurs of these beverages take their enjoyment very seriously, the relative affordability of these caffeinated drinks means that almost anyone can “benefit” from a caffeine boost and also enjoy their flavors. The resulting billion-dollar industries help power the world economy – and its workforce.

America has an especially close relationship with these drinks, one that dates back to before the country was formed. In modern times, coffee has dominated American tastes, but until the 20th century, Americans favored tea. Although still popular, tea drinking in America can be traced back to trade with China by Dutch merchants in the early 1600s.

Today, fast-paced Americans prefer their caffeinated beverages on the go, often consuming them from disposable drinkware. This is in marked contrast to colonial America, where these beverages would have been served from vessels made to impress and consumed as part of elaborate entertainments expressing the host’s good taste. THF 102595

Dutch traders not only introduced Chinese tea to their colony in present-day New York, but also introduced it to Europe. The hot drink quickly rose in popularity and by the end of the 1600s, tea became the most favored hot beverage in Britain. To support the mass consumption by its citizens at home and in its colonies, England became heavily involved in the China trade and the importation of tea.

As social customs evolved around the drinking of tea, so did the equipment used to consume the beverage. Wealthy citizens could afford to have their teapots fashioned in silver and silversmiths in the colonies, like Paul Revere, learned how to create silver designs from imported English examples. Son of Apollos Rivoire, a French immigrant and Boston silversmith, Paul Revere got his start as his father's apprentice.

Pictured here, an English teakettle-on-stand. Paul Revere imitated designs from English silver objects and pattern books in order to create silver in the most fashionable styles. THF 155178

After his father died in 1754, Revere started his career producing a wide variety of silver objects, including elaborate teapots for his wealthier clients. By the 1760s, the colonies faced increased taxation as England attempted to pay off their war debt from the French and Indian War. High taxes on imports like tea angered colonists, resulting in boycotts that affected what Revere could produce as a silversmith.

These taxes led Revere to join a resistance group known as the "Sons of Liberty" whose members included some of his customers angered by the increased taxation. The organization helped fuel anti-British sentiment in the colonies and Revere aided the groups’ cause by printing propaganda that provoked colonist anger towards the Crown.

As a member of the Sons of Liberty, Paul Revere helped energize the movement toward American independence by printing illustrations like this one of the Boston Massacre. An active citizen, he was part of numerous other civic organizations. THF 8141

In 1773, with tensions mounting, Paul Revere and the Sons of Liberty protested England's control over the tea trade by boarding recently docked British tea ships in the Boston harbor and dumping some of their tea chests overboard. The British responded to the event, known as the Boston Tea Party, by shutting the port of Boston and stripping the Massachusetts colony of its right to self-government.

War erupted in 1775 when Britain moved to seize the colonists' gunpowder and firearms outside of Boston. Revere made his famous midnight ride during this time to warn some of his fellow patriots that the British were on their way to arrest them. While patriot duties limited Paul Revere's silversmithing during the Revolutionary War, he returned to his craft as the war came to an end in the 1780s.

Post-war American silver customers preferred the neoclassical design that became popular in Europe during the war. In the years before the War, silver customers had preferred the Rococo style, an aesthetic known for its ornate decorations and curvilinear body designs. In contrast, neoclassical silver celebrated the classical style of Greece and Rome, making use of symmetry, hard lines, and an emphasis on simple forms. As a master craftsman, Revere developed an elegant and personal interpretation of the neoclassical style.

This 1782 teapot shows Revere’s experimentation with the neoclassical style.

The neoclassical teapot shown above was created in 1782 by Revere. Only six teapots featuring this cylindrical body are known to exist and were some of the last that Revere hand-forged, hammering or "raising" them up from a block of silver. In 1785 Revere acquired silver rolling machinery that he used to produce silver sheets. These sheets were cut to form standardized pieces and allowed Revere's shop to produce silver products more quickly. An example of a Revere teapot made from this later method can be seen in our collections here.

On the bottom of the 1782 teapot, the clear markings of Revere are stamped next to a monogram that can be attributed to Joseph and Sarah Henshaw of Boston. THF 166147

With the assistance of the Massachusetts Historical Society, home of the Revere Family Papers, Revere's own record books identified Joseph Henshaw as the patron for this teapot. The records show that on February 22, 1782 Paul Revere made a note that he needed to make a teapot and spoons for Joseph Henshaw. By April 27, 1782 it appears that Revere had completed the order and marked the weight of the teapot as "16-17". This weight of "16-17" can be seen scratched on the bottom of the teapot in the upper right of the picture above.

Joseph Henshaw was a prominent Boston merchant. With his wife Sarah, the two used their home to help plan further American resistance by occasionally hosting "Sons of Liberty" meetings. It was his membership in this radical group that led Joseph Henshaw to form a friendship with Paul Revere. While this teapot is a good representation of the tea culture that existed in the colonies, it is also a symbol of Revere and Henshaw's relationship, a relationship that helped establish the United States of America.

See more on Paul Revere's life from our Digital Collections in this expert set.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

18th century, Massachusetts, making, design, decorative arts, by Ryan Jelso, beverages, #THFCuratorChat

Opening the Door to Preservation

“Opening the Door” is an unusual and large ( 6 feet tall and 4 feet wide) painting that recently received some much-needed conservation here at The Henry Ford.

Painted in the 1840s by self-trained artist George W. Mark, it depicts a young girl holding a flower. She stands in an elaborately-painted open doorway. Behind the girl a bust and lamp are visible on the table in a very shadowy room. The intent is to present a life-size vision that fools the eye into thinking that we are looking into a real space.

If you have the opportunity to take part in a VIP or Special Access tour of our Benson Ford Research Center storage, you will see this painting. It is greatly admired and it is positioned in a prominent location in the state-of-the-art storage facility here at The Henry Ford.

The painting needed conservation attention because it was not in stable condition after years of storage and many moves. Some of the damages were due to the challenges of handling – the painting is not framed, so corners got crushed when it was set down with too much force. And past attempts to hang it resulted in old patched holes near the top.

Take a look behind the scenes to see some of our work conserving "Opening the Door." This project was made possible by the generous support of The American Folk Art Society and Susan and Henry Fradkin. Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable, Conservator Celina Contreras de Berenfeld, and Senior Conservator Clara Deck examine the work in progress.

Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable, Conservator Celina Contreras de Berenfeld, and Senior Conservator Clara Deck examine the work in progress.

This image shows the last old, yellowed varnish as it was removed from the paint surface.

This is a microscopic image of the thick varnish, before and during removal. The cracks (which are actually quite small!) are expected in a painting of this age and type.

Many paintings suffer over time due to the natural aging that darkens the once-clear protective varnish coat. As the varnish darkens, it shifts colors that were originally intense and bright; they become murky and brownish. Varnish removal restores the painting’s original colors. It is not unusual for old varnishes to require renewal, and this was done as part of an extensive conservation treatment completed last year.

Old patches were also redone so that they are invisible from the front and the whole painting was lined with stable backing material to support its large size. The restoration of damaged areas of the paint was done by “in-painting” only the small areas of lost paint. Finally a new, reversible varnish was applied overall.

The final result is a stronger, stable painting that can survive for at least another 171 years in the care of The Henry Ford.

Clara Deck is former Senior Conservator at The Henry Ford.

Massachusetts, 19th century, 1840s, paintings, conservation, collections care, by Clara Deck, art

Lamy's: A Diner from the Golden Age

The 1946 Lamy's diner, as it appears today in Henry Ford Museum. THF77241

Back before diners were considered revered icons of mid-20th-century American culture, Henry Ford Museum's acquisition of a dilapidated 1940s diner raised more than a few eyebrows. Was a diner, from such a recent era, significant enough to be in a museum?

Happily, times have changed. Diners have gained newfound respect and appreciation, as innovative and uniquely American eating establishments. A closer look at Lamy's diner reveals much about the role and significance of diners in 20th-century America. Continue Reading

Massachusetts, 1980s, 1940s, 20th century, restaurants, Henry Ford Museum, food, entrepreneurship, Driving America, diners, by Donna R. Braden