Posts Tagged thf90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 2010s

As the 21st century began, The Henry Ford’s automotive exhibit, Automobile in American Life, was into its second decade of life, and needed a refresh. In a major change that affected 80,000 square feet on the Museum floor, Driving America roared into life in January of 2012.

Not only were the themes and artifacts included in the exhibit completely rethought, but digital technologies were integrated from the beginning to fuel touchscreen kiosks containing activities, curator interviews, and tens of thousands of digitized artifacts from The Henry Ford’s collections—including a substantial new set of glamour shots for each vehicle in the exhibit. This first big experiment with digitized collections within an exhibit is forming the basis for the use of interactive technologies in upcoming exhibits.

Technology Accelerates at the Rouge

In late 2014, Ford Motor Company began producing the first mass-produced truck in its class featuring a high-strength, military-grade, aluminum-alloy body and bed after having completely redesigned its F-150 assembly line at the Ford Rouge plant. This posed a challenge for the Ford Rouge Factory Tour—the manufacturing story had completely changed. An overhaul of the entire experience involved updated experiences in both theaters, particularly in the Manufacturing Innovation Theater, offering a multisensory, multidirectional show. An interactive kiosk, similar to those installed in Driving America, was also installed to allow visitors to access The Henry Ford’s digital collections with the touch of a finger.

Village Growth

While the Village has not yet seen any more changes as substantial as those that occurred in the early part of the 21st century, the period since 2010 has brought a couple of notable upgrades to the working districts of Greenfield Village. One was the 2014 addition of a 50-foot-tall coaling tower, based on historic designs and used to store and load coal into the historic operating locomotives of Greenfield Village.

The other recent project was the physical expansion of the Pottery Shop in 2013, a project sparked by the need to replace a salt kiln that was nearly three decades old. The kiln room was rebuilt and slightly expanded, and by reconfiguring the layout, a spacious area for the decorators to work was also created.

Anniversaries and Remembrances

Despite the growth in digital experiences, the power of physical artifacts is still undeniable. Many significant anniversaries related to the objects and stories of The Henry Ford have been observed with events within Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in recent years.

One of the largest and most notable was the Day of Courage, celebrated with an all-day event on February 4, 2013. Historians, musicians, students, and Museum guests remembered the life of Rosa Parks on her 100th birthday. In November 2013, lectures by newscaster Dan Rather and former Secret Service agent Clint Hill, as well as an opportunity to visit the fateful limousine, formed a remembrance of President John F. Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his assassination. April 2015, the 150th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, was marked with a lecture by historian Doris Kearns Goodwin and the first removal of the Lincoln chair from its display case in decades.

Innovation Focus

Our collecting continues to focus on resourcefulness, innovation, and ingenuity—and both new and old artifacts, along with their stories, are featured in new ways. In particular, as digital technologies became ubiquitous, The Henry Ford began developing new strategies to accomplish its mission to share, teach, and inspire, particularly focused on the “innovation” portion of the mission statement.

The Henry Ford Archive of American Innovation™ represents the core assets of The Henry Ford that illustrate the process and context of innovation. It refers to artifacts and documents in the collection that provide an unprecedented window into America’s traditions of resourcefulness, innovation, and ingenuity. It is the key to understanding how our entire modern world was created.

Related stories of artifacts and innovation are featured on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, a weekly educational TV program produced by Litton Entertainment and hosted by Mo Rocca, which has aired since Fall 2014. Innovation is also brought in through events such as Maker Faire Detroit, hosted annually at The Henry Ford since 2010.

Active Collecting

Though the world has become increasingly digital, The Henry Ford continues to collect hundreds or even thousands of physical artifacts each year. In the second decade of the 21st century, this has included material related to significant artifacts we already hold (John F. Kennedy material, to add additional context to the Kennedy Limousine; and the George Devol collection, which relates to the world’s first industrial robot), design (an Eames-designed, IBM-used kiosk and hundreds of examples of 20th century soap packaging), and auto racing (photographic collections from John Clark and Ray Masser and dozens of tether cars or “spindizzies”).

Major recent acquisitions include the John Margolies Roadside America collection, the Bachmann studio collection of American glass, the Roddis clothing collection, and Mathematica, a circa 1960 exhibit designed by Charles and Ray Eames.

The Collections Go Digital

The Henry Ford began scaling up its collections digitization effort in 2010, hiring new staff with new skills to advance this technology-intensive effort that involves conservation, cataloging, photography, and scanning. Images of tens of thousands of artifacts are now freely available online, from our Digital Collections, and provide the basis for additional layers of supporting content, helping the public to understand artifacts in the context of their original time and place as well as the context of today.

Digitization efforts include artifacts on display within the Museum or Village, new acquisitions, and “hidden” items currently in storage. In 2013–15, for example, more than 1,200 communications-related artifacts in storage, including many significant rediscovered treasures, were digitized through a grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

From Digital Artifacts to Digital Stories

While more than 20,000 artifacts are on public exhibit in Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, the Benson Ford Research Center, and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, The Henry Ford’s collection holds many more—about 250,000 objects and millions more photographs and documents within our archives. Institutional commitment to the digitization of The Henry Ford Archive of American Innovation™ is making these collections, and the ideas behind them, more accessible to more people in more ways than ever.

Acquisitions Made to the Collections - 2010s

Apple 1 Computer, 1976

In 2013, The Henry Ford acquired an Apple 1 computer—one of the first fifty ever made, and fully operational. This groundbreaking device documents an important “first,” as one of the earliest desktop computers to be sold with a pre-assembled motherboard (although users had to purchase a separate keyboard, monitor, and power source). The Apple 1 is also the beginning of something in the sense that it led to the founding of one of today’s most successful computer companies in the world. This artifact demonstrates The Henry Ford’s commitment to collecting the hardware, software, and the ephemeral culture that powers the digital age. You can see a video describing the Apple 1 acquisition and the process of booting it up here. - Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

Throstle Spinning Frame

This rare spinning frame was part of a landmark acquisition, perhaps the largest since Henry Ford’s time--nine truckloads of textile history-related objects and archival materials! Spinning frames like this circa 1835 example--likely the earliest surviving American industrial textile machine--helped spin the large quantities of thread that growing industrial weaving operations needed in the early and mid-19th century. In 2016, the American Textile History Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts closed its doors and began to transfer their collections to other organizations. The Henry Ford was among them--able to provide a home for many thousands of objects dating from the 18th to 21st centuries: textile machinery and tools, clothing and domestic textiles, and hundreds of sample books of printed fabrics from several major New England companies. This rich collection from ATHM tells the story of a key player in America’s Industrial Revolution--the textile industry. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

La-Z-Boy Reclina Rocker

La-Z-Boy is a story of technological innovation, marketing, and sales savvy. Two cousins created the first chair in the late 1920s but didn’t gain acclaim until the 1960s with the Reclina Rocker, which combined a built-in ottoman with a rocking feature. Multi-faceted promotional strategies, including celebrity endorsements, caught the eye of middle-class Americans, who eagerly bought the chair for their homes. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

2016 General Motors First-Generation Self-Driving Test Vehicle

Self-driving cars have the potential to reduce accidents, ease traffic, reduce pollution, and improve mobility for people unable to drive themselves. Assuming we can solve the remaining technical, legal, and psychological challenges, autonomous cars promise to bring the most significant change in our relationship with the automobile since the Model T itself. This experimental vehicle represents General Motors' first major step toward our autonomous future -- and The Henry Ford's first major step to document the journey. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Ruth Adler Schnee Textiles

Designer Ruth Adler Schnee's modern textiles are bold, colorful, and pushed the mid-20th century modern design movement forward. She drew inspiration from the world around her, the ordinary as well as the extraordinary. The Henry Ford's acquisition of her textiles in 2000 and in 2018 speak to her continued relevance to our collection-- as a modern design pioneer, a female entrepreneur, and a Jewish immigrant. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

Robert Propst Papers

Noted industrial designer Robert L. Propst is best known for his work with Herman Miller and for designing the “Action Office,” an office furnishing system which became the basis for the modern cubicle. Propst’s papers cover the design and business aspects of “Action Office” as well many of his other projects such as a residential housing system, hotel housekeeping carts, hospital furniture, an industrial timber harvester, and even children's playground equipment. - Brian Wilson, Sr. Manager, Archives and Library

Champion Egg Case Machine, 1900-1925

This artifact furthers The Henry Ford's mission in several ways –it’s the product of an innovator. James Ashley first patented a box-making machine in 1892. Resourceful farm families with eggs to sell built boxes with this machine, marked the contents "farm fresh," and shipped their product to meet the growing demand of chicken-less urban consumers. The machine created a standardized box which held 12 flats (six on each side). Each flat held 30 eggs for a total of 360 eggs (30 dozen) in one box. Consumers today eat eggs transported to market on flats in boxes similar to the ones this machine was designed to build. Ashley's egg-case maker helps document the long history of farm-market exchange that responded to wary consumers' concerns over the freshness of the agricultural product. - Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

events, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Robert O. Derrick, Architect of Henry Ford Museum

Robert O. Derrick, about 1930. THF 124645

As part of our 90th anniversary celebration the intriguing story of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s design bears repeating. It was last discussed in depth in the 50th anniversary publication “A Home for our Heritage” (1979).

Our tale begins on the luxury ocean liner R.M.S. Majestic, then the largest in the world, on its way to Europe in the spring of 1928. On board were Henry and Clara Ford, their son Edsel and Edsel’s wife Eleanor. Serendipitously, Detroit-based architect Robert O. Derrick and his wife, Clara Hodges Derrick, were also on board. The Derricks were approximately the same age as the Edsel Fords and the two couples were well-acquainted. According to Derrick’s reminiscence, housed in the Benson Ford Research Center, he was invited by Henry Ford to a meeting in the senior Fords’ cabin, which was undoubtedly arranged by Edsel Ford. During the meeting Derrick recalled that Mr. Ford asked how he would hypothetically design his museum of Americana. Derrick responded, “well, I’ll tell you, Mr. Ford, the first thing I could think of would be if you could get permission for me to make a copy of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. It is a wonderful building and beautiful architecture and it certainly would be appropriate for a collection of Americana.” Ford enthusiastically approved the concept and once back in Detroit, secured measured drawings of Independence Hall and its adjacent 18th century buildings which comprise the façade of the proposed museum. Both Derrick and Ford agreed to flip the façade of Independence Hall to make the clock tower, located at the back side of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, a focal point of the front of the new museum in Dearborn.

Robert Ovens Derrick (1890-1961) was an unlikely candidate for the commission. He was a young architect, trained at Yale and Columbia Universities, with only three public buildings to his credit, all in the Detroit area. He was interested in 18th century Georgian architecture and the related Colonial Revival styles, which were at the peak of their popularity in the 1920s.

In his reminiscence, he states that he was overwhelmed with the commission, but was also confident in his abilities: “I did visit a great many industrial and historical museums and went to Chicago. I remember that I studied the one abroad in Germany, [The Deutsches Museum in Munich] which is supposed to be one of the best. I studied them all very carefully and I did make some very beautiful plans, I thought. Of course, I was going according to museum customs. We had a full basement and a balcony going around so the thing wouldn’t spread out so far. We had a lot of exhibits go in the balcony. I had learned that, in museum practice, you should have a lot more storage space, maintenance space and repair shops than you should have for exhibition. That is why I had the big basement. I didn’t even get enough there because I had the floor over it plus the balconies all around.”

Original museum proposal, aerial view. THF 170442

Original museum proposal, facade design. THF 170443

Original museum proposal, side view. THF 170444

In the aerial view [THF0442], the two-story structure is a warren of courtyards and two-story buildings, with exhibition space on the first floor and presumably balconies above, although no interior views of this version survive. A domed area on the upper right was to be a roundhouse, intended for the display of trains. THF0443 shows a view of the front of the museum from the southeast corner. This view is close to the form of the completed museum, at least from the front. An examination of the side of the building [THF0444] shows a two-storied wing.

Derrick recalled Mr. Ford’s initial response to his proposals, “What’s this up here? and I said, that is a balcony for exhibits. He said, I wouldn’t have that; there would be people up there, I could come in and they wouldn’t be working. I wouldn’t have it. I have to see everybody. Then he said: What’s this? I said, that is the basement down there, which is necessary to maintain these exhibits and to keep things which you want to rotate, etc. He said, I wouldn’t have that; I couldn’t see the men down there when I came in. You have to do the whole thing over again and put it all on one floor with no balconies and no basements. I said, okay, and I went back and we started all over again. What you see [today] is what we did the second time.” Henry Ford Museum proposed Exhibit Hall. THF294368

Henry Ford Museum proposed Exhibit Hall. THF294368

A second group of presentation drawings show the museum as it was built in 1929. THF294368 is the interior of the large “Machine Hall,” the all-on-one-floor exhibit space that Mr. Ford requested. The unique roof and skylight system echo that of Albert Kahn’s Ford Engineering Laboratory, completed in 1923 and located just behind the museum. Radiant heating is located in the support columns through what appear to be large flanges or fins. The image also shows how Mr. Ford wanted his collection displayed – in long rows, by types of objects – as seen here with the wagons on the left and steam engines on the right.

Proposal for museum corridor. THF 294390

Proposal for museum corridor. THF 294388

These corridors, known today as the Prechter Promenade, run the width of the museum. Floored with marble and decorated with elaborate plasterwork, the promenade is the first part of the interior seen by guests. Mr. Ford wanted all visitors to enter through his reproduction of the Independence Hall Clock Tower. The location of Light’s Golden Jubilee, a dinner and celebration of the 50th anniversary of Thomas Edison’s development of incandescent electric lamp, held on October 21, 1929 is visible at the back of THF294388. This event also served as the official dedication of the Edison Institute of Technology, honoring Ford’s friend and mentor, Thomas Edison. Today the entire institution is known as The Henry Ford, which includes the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village.

Museum Auditorium. THF 294370

Just off the Prechter Promenade is the auditorium, now known as the Anderson Theater. Intended to present historical plays and events, this theater accommodates approximately 600 guests. During Mr. Ford’s time it was also used by the Greenfield Village schools for recitals, plays, and graduations. Today, it is used by the Henry Ford Academy, a Wayne County charter high school, and the museum for major public programs.

Virginia Courtyard inside Henry Ford Museum. THF294374

Pennsylvania Courtyard inside Henry Ford Museum. THF294392

Derrick created two often-overlooked exterior courtyards between the Prechter Promenade and the museum exhibit hall. Each contains unique garden structures, decorative trees and plantings, and both are accessible to the public from neighboring galleries.

Greenfield Village Gatehouse front view, about 1931. THF 294382

Greenfield Village Gatehouse rear view, about 1931. THF 294386

The Greenfield Village Gatehouse was completed in 1932 by Robert Derrick, in a Colonial Revival style to complement the Museum. From its opening in 1932 until the Greenfield Village renovation of 2003, the gatehouse served as the public entrance to the Village. Today, visitors enter the Village through the Josephine Ford Plaza behind the Gatehouse. Although the exterior was left unchanged in the renovation, the Gatehouse now accommodates guests with an updated facility, including new, accessible restrooms and a concierge lounge with a will-call desk for tickets.

Lovett Hall in 1941. THF 98409

Edison Institute students dancing in Lovett Ballroom, 1938. THF 121724

Edison Institute students in dancing class with Benjamin Lovett, instructor, 1944. THF 116450

In 1936 Robert Derrick designed the Education Building for Mr. Ford. Now known as Lovett Hall, the building served many purposes, mainly for the Greenfield Village School system. It housed a swimming pool, gymnasium, classrooms, and an elaborately-decorated ballroom, where young ladies and gentlemen were taught proper “deportment.” Like all the buildings at The Henry Ford, it was executed in the Colonial Revival style. Today the well-preserved ballroom serves as a venue for weddings and other special occasions.

Obviously, Mr. Derrick was a favorite architect of Mr. Ford, along with the renowned Albert Kahn, who designed the Ford Rouge Factory. The museum was undoubtedly Derrick’s greatest achievement, although he went on to design Detroit’s Theodore J. Levin Federal Courthouse in 1934. Unlike the Henry Ford commissions, the courthouse was designed in the popular Art Deco, or Art Moderne style. Derrick is also noted for many revival style homes in suburban Grosse Pointe, which he continued to design until his retirement in 1956. He is remembered as one of the most competent, and one of the many creative architects to practice in 20th century Detroit.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford, Dearborn, by Charles Sable, THF90, Michigan, Henry Ford Museum, drawings, design, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 2000s

By the late 20th century, competition for the public’s leisure time was fierce and audience expectations were changing. Museum staff laid the foundation for a new generation of offerings in several distinct and separate venues—creating a unique, multi-day destination opportunity for local and out-of-town guests. These included: Henry Ford Museum, featuring a new changing exhibit gallery in 2003; Greenfield Village, refreshed and reimagined in 2003; IMAX® Theatre, opened in 1999; Benson Ford Research Center, opened in 2002; and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, created in partnership with Ford Motor Company in 2004 and featuring a fully functioning, state-of-the-art manufacturing facility. Adding so many new venues to the museum led to a name change to encompass them all—The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford acquired its Douglas DC-3 airplane in 1975. Due to its size, the plane initially was displayed outside Henry Ford Museum. In 2002, the plane was disassembled and thoroughly conserved to correct the effects of 27 years of weather exposure. The treated DC-3 was reassembled for display inside the museum in 2003.

Bidding on History

Rosa Parks Bus in Montgomery, Alabama, 2000-2001, before Acquisition by The Henry Ford

In September 2001, an article in the Wall Street Journal announced that the Rosa Parks bus would be auctioned online in October, and we immediately began researching this opportunity.

We spoke to people involved in the original 1955 events, to those who planned other museum exhibits, and to historians. A forensic document examiner was hired to see if the scrapbook was authentic. A Museum conservator went to Montgomery to personally examine the bus.

Convinced that this was the Rosa Parks bus, we decided to bid on the bus in the Internet auction.

The bidding began at $50,000 on October 25, 2001 and went until 2:00 AM the next morning. We persevered, with our staff bidding $492,000 to outbid others who wanted the bus, including the Smithsonian Institution and the City of Denver. At the same time, our team also bought the scrapbook and a Montgomery City Bus Lines driver's uniform.

Collecting in the 2000s

Pig Pen Variation and Mosaic Medallion Quilt by Susana Allen Hunter, 1950-1955

Recent decades found curators gathering objects and stories of previously underrepresented groups. In 2006, the museum acquired 30 quilts made by African American quiltmaker Susana Hunter. After working the fields of her rural Alabama tenant farm and tending to her family's needs, Susana Hunter sat down to lavish her creativity on quiltmaking. On-the-fly inspiration--rather than tradition--guided her improvisational creations made from the worn clothing and fabric scraps available to her. Along with Susana Hunter’s quilts came quilting and household equipment from her simple, two-room house that had no running water, electricity, or central heat. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Everlast "Fallen Leaves" Relish Tray, 1940 – 1941

During the early 2000s, curators sought out collections representing entrepreneurial stories to broaden our holdings. From the 1930s into the 1960s, the Everlast Metal Products Company manufactured aluminum giftware, which became fashionable during the Depression as an alternative to silver. Founded by immigrant brothers-in-law in Brooklyn, New York, they also partnered with designers, such as Russel and Mary Wright, who designed this relish tray. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

"Monarch Coffee" Thermos, circa 1931

The Henry Ford opened "Heroes of the Sky" in 2003, just in time to commemorate the centennial of the Wright brothers' first flight. Several pieces were acquired in advance of the exhibit, but this simple little vacuum flask is a favorite. It's a relatable object that helps us to imagine those early days of open cockpits and seat-of-the-pants navigation -- when a pilot had little more than coffee with which to keep warm and alert. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

4-H Uniform, circa 1948

The 4-H began as a youth program in Ohio in 1902 and by 1914 it became an official program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Federal Extension Service and cooperating state-based land-grant colleges. Boys and girls formed and managed their own local clubs. Ruth Ann Goodell joined the Eden Willing Workers 4-H Club near Garrison, Iowa, in 1942 when she was 10 years old. She sewed this uniform during the late 1940s, likely applying sewing skills she learned through club activities. The Henry Ford, anticipating the 100th anniversary of 4-H, collected this uniform as evidence of rural and farm youth culture.- Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Support 90 Years of Innovation

At The Henry Ford, we believe inside every person is the potential to change the world.

For 90 years, The Henry Ford has been a force for sparking curiosity and inspiring tomorrow’s innovators, inventors and entrepreneurs thanks to the generosity of our visitors, members, staff, volunteers and more. Their support helps us build on Henry Ford’s original mission to make this institution a hands-on learning resource for the visionary in all of us.

As we move closer to celebrating our 90th anniversary this October, here are nine ways you can go above and beyond to support The Henry Ford and our mission.

Visit

It may sound simple, but bringing your friends and family to The Henry Ford any day of the year is a great way to support our organization! When you’re here, make sure to post pictures and videos from your visit and don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter and social accounts.

Shop at The Henry Ford

Consider supporting The Henry Ford by making a purchase at one of our retail locations. Gift cards can be used in any of our stores, as well as towards the purchase of a membership, handcrafted Liberty Craftworks piece or hands-on learning kit for all ages.

Become a member

Our members help make so much of what we do at The Henry Ford possible! If you’re already a member, you can always give the gift of membership, encourage your employer to become a corporate member or join the Donor Society.

Host an event

During many days of the week, when our doors close at 5 pm, we’re simultaneously opening our doors to evening event guests. Weddings, company picnics and holiday parties are all great ways to support our mission at The Henry Ford.

Volunteer your time

We love our volunteers! There are many ways to serve as a volunteer here at The Henry Ford. We are always looking for greeters, counselors with our summer camps and extra assistance at special programs throughout the year.

Donate to our Annual Fund

Donations to The Henry Ford Annual Fund go towards projects both big and small across our campus. You can make a monthly gift, apply for an employer-matched gift or leave a legacy through a planned gift.

Support local schools and students

Every year thousands of students visit The Henry Ford and are inspired by our collection. Help even more students learn from these stories of American Innovation by providing a school field trip scholarship, sending a child to summer camp or supporting a student in our Youth Mentorship Program.

Honor a loved one with a memorial gift

Memorial benches in Greenfield Village, named theater seats at the Giant Screen Experience and book plates in the Benson Ford Research Center are all wonderful ways to honor a family member, friend or special occasion.

Donate to The Innovation Project

The Innovation Project is a $150 million comprehensive campaign to build digital and experiential learning tools, programs and initiatives to advance innovation, invention and entrepreneurship. Gifts made to The Innovation Project will help us achieve greater accessibility, inclusivity and exposure to unlock the potential of the next generation.

Amanda Floyd is the Annual Fund Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1990s

Rosa Parks Visiting Mattox House in Greenfield Village, August 1992. THF125176

By the early 1990s, museum staff decided that The Henry Ford's mission statement about America’s change through time was both too oriented toward the past and too inwardly focused on the museum’s own work.

In 1992, staff settled upon a new mission statement with three key words—innovation, resourcefulness, and ingenuity—that both aligned with Henry Ford’s original vision and provided better opportunities to impact and inspire current and future audiences. These three words shaped and energized collecting—to encompass such topics as social transformation, modern design, and the stories and objects connected with innovators and visionaries. The Museum would launch its first web site in 1995.

In the 1990s, collecting objects that reflected social and technological history of the second half of the 20th century increasingly became a focus. This 1960 Park and Shop game--representing a typical shopping center of the era, complete with parking lot--mirrored the rapid suburbanization of the post-World War II era as people moved from cities into the surrounding new suburbs. This game also immersed children in an adult world of shopping and consumerism. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

In the 1990s curators sought out Arts and Crafts era objects—especially those made by women—such as this charming silver and enameled jam dish and spoon, made about 1905 by silversmith Mary Winlock. Winlock was educated at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the 1890s, and in 1903 she joined the Handicraft Shop, an artist cooperative, where she sold her distinctive enameled silver and jewelry. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

The Henry Ford's auto racing collection covers all of the most popular racing types in the United States, and it includes several landmark cars. None may be more significant than "Old 16," winner of the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup. This legendary Locomobile was the first American car to win America's first great international race, and it served notice that American-built cars were every bit as good as their European counterparts. Never restored, "Old 16" still looks much as it did at the time of that victory. We intend to preserve the car just as it is -- a rare and important survivor from motorsport's earliest years. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

During the 1990s, the museum leadership actively sought to represent more diverse American voices at Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. In response, a collections task force called for an increase in the racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity of the collections. Curators purchased images, like this one, that depicted the lives of African Americans, Jews, and immigrant populations. - Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

The Henry Ford's collection of mid-20th century design expanded as the century came to a close. In 1992, the Herman Miller furniture company donated a substantial collection of material designed by Alexander Girard, the Director of Design of Herman Miller's textile division from 1952-1973. Girard's incredible eye for color, texture, and whimsy helped transform the aesthetic of the modern movement. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

In the 1990s, the museum assessed its holdings and developed guidelines for future collecting. The acquisition of a group of pictorial lunchboxes in 1999 reflected a new focus on post-World War II America. Introduced in 1950, pictorial lunchboxes relate to mass media, merchandising, and the Baby Boomer generation. Curators selected lunchboxes representing current events and popular culture, especially TV shows and movies. -Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Large machine designed to harvest a delicate crop - the mass-produced and processed tomato. Tomato genetic research in California made the machine viable but this machine was sold in Ohio to a northern Illinois truck farming family. The story is essential to conveying the massive scale required to put canned tomatoes on grocery store shelves. - Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum, THF90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1980s

Construction at Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village, January 1985. THF138461

Guided by the 1980s mission-based phrase, “Stories of a Changing America,” Greenfield Village took on new life and Henry Ford Museum exhibits explored new topics. These included the acquisition of the Firestone farmhouse and creation of its living history program (1985), the “Automobile in American Life” exhibit (1987), and the “Made in America” exhibit (1992). During the 1980s and 1990s, museum staff placed new attention on accurate research, creative program planning, and engaging public presentations.

Additions the collections: 1980s

Elizabeth Parke Firestone donated a large segment of her stunning wardrobe in 1989, including custom-made garments created for her by prominent American and European couturiers. Firestone was an early client of French designer Christian Dior, who had just caused a sensation introducing his “New Look” to a post-WWII world, emphasizing slim waists and rounded feminine features. Firestone visited Dior’s Paris salon in 1946 and commissioned this dress, made for her daughter Martha’s wedding to William Clay Ford. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

This type of lamp is typically called a "Television Lamp." It was made to sit atop a television console and to provide a low level of illumination, sufficient to keep one's eyes from being "harmed" by watching the small TV screens of that time (1946-1960). This marks a change in collecting as curators sought out objects that provided insight into social history. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

For 50 years Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation generally presented artifacts in a traditional typological format. Tractors, airplanes, furnishings -- you name it -- sat in tidy rows where visitors were left to trace an item's technological evolution. That all began to change in the 1980s as the museum refocused on social history. No exhibit signaled this shift more dramatically than "The Automobile in American Life," opened in 1987. Cars were moved out of their stodgy rows and instead placed alongside contextual items like maps and travel literature, menus from quick-service restaurants, and replicated roadside lodgings. This Holiday Inn "Great Sign" was one of the more visible artifacts acquired for the new show. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

In 1982, Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village purchased the Seymour Dunbar Collection from Chicago's Museum of Science & Industry. The collection consists of over 1,700 prints, drawings, maps, and other items documenting various modes of travel from 1680 to 1910. Dunbar compiled this material while researching his four-volume history of travel in the U.S., which was published in 1915. - Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Reflecting a new emphasis on social history, museum staff developed interpretive exhibits that integrated objects from across collections categories to examine special themes. “Streamlining America” explored an influential mid-20th-century ideology and design style. This striking poster, selected for the exhibit, embodies the streamlined environment of the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair. - Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Harold K. Skramstad, Jr., president of The Edison Institute, considered the opening of Firestone Farm a "landmark event." Why? The house, barn, and outbuildings added a living historical farm to Greenfield Village, complete with wrinkly Merino sheep collected to sustain the type and increase interpretive potential. - Debra A. Reid, Curator, Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1970s

Lighting and Communications Exhibits at Henry Ford Museum, 1979. THF112161

Home Arts Exhibit at Henry Ford Museum, 1979. THF112157

Transportation Exhibit at Henry Ford Museum, 1979. THF112159

Inaugural Run of the Torch Lake Steam Locomotive and Passenger Train in Greenfield Village, August 9, 1972. THF133929

With an unmatched treasury of America’s past already at their fingertips, the staff at Henry Ford Museum continued Henry Ford’s vision as they began to add to the collection.

1939 Douglas DC-3 after Move from Ford Proving Ground to Henry Ford Museum, June 2, 1975. THF124077

In 1974, North Central Airlines (known today as our partner Delta after a series of mergers) donated a 1939 DC-3 Douglas airplane that, at the time of its donation, had flown more than 85,000 hours, more than any other plane. In 1978, the Ford Motor Company donated the limousine President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy rode in when he was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. The car, leased by the government from Ford Motor Company, was extensively rebuilt and then used by four presidents after Kennedy. The Ford Motor Company donation stipulated that the car could not be displayed until the Kennedy children reached adulthood.

Decorative Arts Gallery in the Henry Ford Museum Promenade, 1976. THF271166

In the 1970s, museum staff began to place more emphasis on collection decorative and fine arts, such as furniture and paintings. The museum’s research library began to acquire engravings, rare books, and documents associated with the early history of the country, such as an original Paul Revere engraving of the Boston Massacre and a copy of the famous “Stamp Act,” published in London in 1761. In the early 1970s, the museum purchased an extraordinary collection of 19th century quilts made my Susan McCord, an Indiana farmwife.

Fire Damage, Henry Ford Museum, August 9, 1970. THF111720a

As the museum staff worked to make significant improvements to the museum experience, they faced another challenge. In August 1970, as more than 1,000 visitors toured the exhibits, a fire broke out in the museum. It was one of the worst fires to ever hit an American museum, destroying hundreds of artifacts, including major portions of the textile collections. Though the museum reopened to the public in just two days, it was a full year before the building was completely repaired.

Torch Lake Locomotive at Main Street Station in Greenfield Village, July 1978. THF133933

Let Freedom Ring Parade, Greenfield Village, 1976. THF112250

This decade witnessed a flurry of planning and construction, with a steady stream of improvements designed to broaden the appeal and educational impact of Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. (Attendance at historic sites was climbing during the early 1970s as the nation moved toward the bicentennial of its founding.) The expansion was intended to attract new audiences and set the institution on a path to self-sufficiency. In Greenfield Village, the most dramatic changes were the new railroad and period amusement park. The railroad line, completed in 1972, circled the village perimeter. Visitors rode in open cars, pulled by a steam locomotive. The train quickly became a visitor favorite.

Suwanee Park and Steamboat, Greenfield Village, 1975. THF95455

Suwanee Park, located alongside the Suwanee Lagoon, opened in 1974 as a recreation of a turn-of-20th amusement park. The complex was designed to be a “focal point fun,” offering a “nostalgic look at how American amused themselves in bygone days.” The centerpiece of the new amusement park complex was a restored, fully operational, 1913 Herschell-Spillman Carousel.

The village received an important new building in the 1970s, a mid-18th-century rural Connecticut saltbox house (now Daggett Farmhouse). In Henry Ford Museum, the vast Hall of Technology underwent a total redesign. New restaurants and gift shops further improved the visitor experience. In 1972, the museum opened its first professional conservation lab and staffed it with trained conservators. A year later, the Tannahill Research Center (now incorporated into the Benson Ford Research Center) opened and held the institution’s remarkable collection of historical manuscripts, books, periodicals, maps, prints, photographs, music, and graphic collections.

Additions Made to the Collections: 1970s

“Brewster” Chair, 1969

In 1970, the Museum purchased what was believed to be a rare and remarkable 17th century armchair. In 1977, a story broke about a woodworker who attempted to demonstrate his skill by making a similar chair that would fool the experts. Analysis proved the Museum's chair was the woodworker's modern fake. Today we use this chair as a teaching tool in understanding traditional craft techniques. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

Susan McCord Vine Quilt

In 1970, a fire in Henry Ford Museum destroyed many objects on exhibit and in storage--including much of the quilt collection. Curators soon began to fill the void. An exceptional acquisition in 1972 brought ten quilts made by Indiana farmwife Susan McCord--an ordinary woman with an extraordinary sense of color and design. This distinctive vine pattern is a McCord original, made by sewing together fabric scraps to create over 300 leaves for each of the thirteen panels. McCord’s quilts remain among the most significant in the museum’s collection. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

1961 Lincoln Continental Presidential Limousine

For years, the White House leased Lincoln parade limousines from Ford Motor Company. When the leases ended, Ford Motor reclaimed the cars and generously gifted them to The Henry Ford. This arrangement enabled our unmatched collection of presidential vehicles. None is more significant than the 1961 Continental that carried President Kennedy through Dallas in November 1963. Following the assassination, the open car was rebuilt with a permanent roof, armor plating, and other protective features and put back into service. The Henry Ford acquired the limo in 1978 and first exhibited it -- alongside its 1939 and 1950 Lincoln predecessors -- in 1981. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Black & Decker Type AA Circular Saw, 1930-1931

In the 1970s, curators worked to bring Henry Ford Museum’s considerable tool collection into the 20th century. As part of that effort, staff wrote to power tool manufacturer Black & Decker for information about its history and most important products. The company responded with a donation of five electric power tools, including this example of Black & Decker’s first portable circular saw. -Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Self-Propelled Cotton Picker, 1950

John Rust invented a wet-spindle system for mechanically picking cotton in 1928. By 1933 his machine picked five bales per day (2,500 lbs). Peter Cousins, Curator of Agriculture, wanted one of Rust’s machines, and Allan Jones agreed to donate his 1950 picker, named "Grandma," in 1975. Twenty years of life intervened before the picker arrived at The Henry Ford in January 1995. -Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1960s

Henry Ford Museum, 1965. THF133278

During the 1950s and the 1960s, the museum prepared to engage a new generation of visitors. Fresh paint, improved exhibits, special events, and enhanced amenities began to transform the museum into an increasingly attractive destination for the visiting public.

Staffordshire Case in Decorative Arts Gallery in Henry Ford Museum, circa 1960. THF139326

In Henry Ford Museum, curators reduced the number of objects on display in the main exhibit hall, arranged the artifacts in a more orderly fashion, and provided explanatory labels. The transportation collections were rearranged, presenting the trains, automobiles, and bicycles in chronological order for the first time. This helped visitors see more clearly how technology and design had evolved over time, Similarly, the decorative arts galleries grouped furniture, ceramics, glassware, and silver to show the evolution of American taste.

Edison Institute Board of Trustees, 1967. THF133538

In 1969, as the institution celebrated its 40th anniversary, William Clay Ford, then board chairman of Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, announced that both the Ford Motor Company and the Ford Foundation would each donate $20 million in grants to the organization. In speaking at the anniversary celebration that year, William Clay Ford said, “I think the institute is one of the great philanthropic legacies of my grandfather. It in no way diminishes the significance of this historic resource to note that he underestimated its financial needs when he conceived it more than a generation ago.”

Nearly half of the money was used for needed improvements to museum and village facilities and programming. The remainder was used to create an endowment fund to provide for future income. The announcement launched a period of development not see seen since Henry Ford’s era.

Acquisitions Made to the Collections in the 1960s

Samuel Metford Silhouette of Noah and Rebecca Webster

Samuel Metford Silhouette of Noah and Rebecca Webster

The museum purchased this 1842 silhouette of Noah and Rebecca Webster in 1962--just in time to be placed in the Webster House as it was being opened to the public for the first time since it was moved from New Haven, Connecticut in 1936. This silhouette, mentioned in Rebecca’s will, had been left to a Webster daughter. Curators were fortunate to have also acquired an original Webster desk, sofa, and some portraits to include along with other period furniture, tableware, paintings, quilts, and accessories. Yet, when completed, the rooms were more effective at showcasing fine decorative arts objects than reflecting the Webster family’s life. The era of historically accurate, immersive settings had not yet arrived in the museum field. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Oil Painting, "Sarah ... at the Age of Four," 1830-1840

Throughout the mid-20th century, curators sought out the best examples of decorative and folk arts, one of which is this portrait of a 4-year-old girl named Sarah. Painted around 1830 by an itinerant artist, this endearing girl carries a basket of stylized fruit and flowers and wears a necklace of coral beads, which were thought to ward off illness. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

1965 Ford Mustang Serial Number One

Mustang fans know the story well. Canadian airline pilot Stanley Tucker bought Serial Number One in Newfoundland on April 14, 1964. After Mustang became a sales sensation, Ford spent two years convincing Tucker to give it back (ultimately, in trade for a fully-loaded '66 Mustang). Ford Motor Company then gave Serial Number One to The Henry Ford where the landmark vehicle immediately... went into storage until 1984. Such was the museum's philosophy in those days. A vehicle wasn't truly historic -- and worthy of display -- until it reached 20 years of age. Happily, exhibit policies and visitor expectations are quite different today! - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

License plate - "Michigan License Plate, 1913" - Michigan. Dept. of State

The museum's collection not only includes automobiles, but automotive accessories and registration materials. In the 1960s, the State of Michigan donated a run of Michigan license plates dating from about 1906 to 1968. Alongside the museum's historic vehicles, these objects help tell the rich story of America's automotive history. -Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

First Portable Superheterodyne Radio Receiver, Made by Edwin Howard Armstrong, 1923

By the 1960s, Curator of Mechanical Arts, Frank Davis, and his curatorial colleagues had started to organize the thousands of artifacts collected during Henry Ford's lifetime. The collections displayed in the museum's vast Mechanical Arts Hall, curated by Davis, contained machines related to agriculture, power generation, lighting, transportation, and communication. With a special interest in radio, Davis couldn't pass up the chance to add this radio to the collection in 1967. Created by pioneer of radio engineering and credited inventor of FM radio, Edwin Howard Armstrong, this radio was a gift to Armstrong’s wife for their 1923 honeymoon and the first portable "superhet" radio receiver ever made. - Ryan Jelso, Associate Curator of Digital Content

Torch Lake Steam Locomotive, 1873

In 1969, as the institution celebrated its 40th anniversary, board chairman William Clay Ford announced an extensive expansion and improvement program that would include the creation of a perimeter railroad for Greenfield Village. The 1873 Torch Lake, originally used by a copper mining company in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, fit in perfectly with these plans. Returned to operating condition, the engine shifted from hauling ore to transporting passengers and was just shy of 100 years old when the railroad opened in 1972. - Saige Jedele, Associate Curator of Digital Content

Ford Motor Company Historic Business Records Collection

In 1964, the Ford Motor Company donated its archive to Edison Institute, with the records from the office of Henry Ford at the collection’s core. Housed in over 3,000 boxes and forming an unbroken run of correspondence from 1921 through 1952, the Engineering Lab Office Records are a remarkable group of materials that document a period of more than thirty years of activity of one of the world's great industrialists and his company. -Brian Wilson, Sr. Manager, Archives and Library

The Ford Motor Company transferred business records to the Edison Institute in 1964. The transfer included this 1960 advertisement for the Ford 981 diesel tractor and the Ford 250 hay baler. Existing collections had not covered this time period. Henry Ford and collectors such as Felix Roulet focused on earlier technological innovations as they built the collection between the 1920s and 1940s. When Peter Cousins joined the staff in 1969 as the first trained historian hired to curate agriculture, his research confirmed inventors and patent numbers and affirmed the richness of the collection. He also identified items still needed to tell authentic stories about technological history after Henry Ford's era. - Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum, THF90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1950s

Henry Ford’s energy had been the animating force behind the Edison Institute. His death in 1947 challenged the institution to manage a collection that had grown to massive proportions – with no adequate storage solutions and no formal cataloging system.

Aerial View of Henry Ford Museum, circa 1953. THF112188

Clara Ford took over for her husband after his death, and the skeletal staff maintained the status quo at the Institute for the next few years without real direction. In 1950, the death of Clara signaled the end of another era. The Ford family stepped away from the daily management of the institution and began a strong tradition of lay leadership. In the early 1950s, all three of the Fords’ grandsons served on the Board of Trustees. William Clay Ford took over the position of board president in 1951 and remained chairman of the board for 38 years. Museum Executives and "Today" Show Staff after Live Broadcast from Greenfield Village, October 25, 1955. THF116184

Museum Executives and "Today" Show Staff after Live Broadcast from Greenfield Village, October 25, 1955. THF116184

In January 1951, the board appointed A.K. Mills to the new post of executive director of Greenfield Village and the Edison Institute Museum. He implemented business practices and hired professional staff members. During the 1950s, the public – especially the vast traveling public – became the focus of the institution’s attention. In 1952, as a tribute to its founder, the Edison Institute was renamed Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. Mills died suddenly in 1954; Donald Shelley replaced him as executive director, a position he held for the next 22 years. Industrial Progress U.S.A. Exhibit, Henry Ford Museum, 1952-1954. THF112172

Industrial Progress U.S.A. Exhibit, Henry Ford Museum, 1952-1954. THF112172

Traveling exhibits, developed by the institution in the 1950s, offered the museum a chance to promote itself beyond the local area, increase awareness, and increase visitation. Henry Ford Museum’s attendance steadily climbed each year. The number of visitors doubled over the decade, from 500,000 in 1950, to 1 million by 1960. The village and museum had become a national attraction.

Acquisitions to the Collections: 1950s

Walking Doll

In the 1950s, the museum’s curators acquired many objects for the collection through a network of antique collectors and dealers. Curators were especially looking for folk art and other “early American” objects. Collector Titus Geesey of Wilmington, Delaware had filled his home with three decades worth of collecting. Ready to pare down a bit, Geesey sold over 300 objects to the museum over the years, including prints, tableware, coverlets, a weathervane, and toys. This late 19th-century mechanical doll from Geesey’s collection came in 1958. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Moravian Bowl with Stylized Fish and Turtles in Center, 1810-1820

In the mid-20th century, Henry Ford Museum built on its early holdings to become one of the preeminent collections of American decorative and folk arts. This ceramic serving bowl was made by Moravian-German immigrants in Alamance County, North Carolina. The playfully arranged turtles and fish are unique representations in Moravian ceramics, which usually emphasizes abstract decoration. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

1941 Allegheny Steam Locomotive

It's perhaps the most photographed object in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, and certainly among the best-remembered by our visitors. The mighty Allegheny has anchored the museum's railroad collection since 1956. Used steam locomotives were a dime a dozen in those days as railroads switched to diesel-electric power. Some went to museums and some to tourist railroads. But many more went to city parks and county fairgrounds, left to the mercies of the weather. The Allegheny is a gem carefully preserved indoors for more than 60 years now -- four times longer than it actually operated on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

"Battle Scenes of the Rebellion" Battle of Gettysburg, Civil War Panorama"

In the 1880s, Thomas Clarkson Gordon (1841-1922), a self-taught artist and Civil War veteran, created a panorama depicting scenes from the Civil War. Gordon toured his 15-paneled panorama throughout eastern Indiana, retelling the history of the conflict through his vivid illustrations. In 1956, Thomas Gordon's daughters wrote to Henry Ford II, hoping he would want the panorama for his grandfather's "Dearborn Museum." The request was redirected to the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. The donation arrived in 1958. - Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Birth and Baptismal Certificate for Maria Heimbach, 1784|

German immigrants in Pennsylvania created fraktur – highly-decorated documents – to commemorate life’s most significant events. This particular fraktur is a Geburts-und Taufscheine – or a birth and baptismal certificate – and is the most common type. The name fraktur is rooted in a German calligraphic tradition and was primarily used for official documents. The Pennsylvania German frakturs continue this typographic tradition but expand upon it to create a new cultural tradition for a new homeland. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

1953 Ford X-100 Concept Car

During its 50th anniversary in 1953, Ford Motor Company celebrated the past and looked to the future. A. K. Mills -- former head of Public and Employee Relations and recently-appointed Executive Director of the newly-renamed Henry Ford Museum -- managed multiple anniversary projects. While Mills organized new exhibits, oral histories, books, films, and -- most importantly -- a company archive, Ford engineers completed a special project of their own. Their fully-functional concept car, known as the X-100, was showcased during anniversary celebrations and featured more than 50 futuristic innovations, including heated seats and a telephone. - Ryan Jelso, Associate Curator

Print of Mary Vaux Walcott Wildflower Sketch, "Trumpet Honeysuckle," 1925

Clara Ford was an active gardener who presided over several gardening organizations during her lifetime. Citing her interest in flowers, the William Edwin Rudge Printing House of New York sent Mrs. Ford a set of prints originally illustrated by Mary Vaux Walcott in 1925. (The gift also served to demonstrate the quality of the firm’s color reproductions.) When Clara Ford died in 1950, a group of items from her estate – including these prints – came into the museum’s collection. - Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

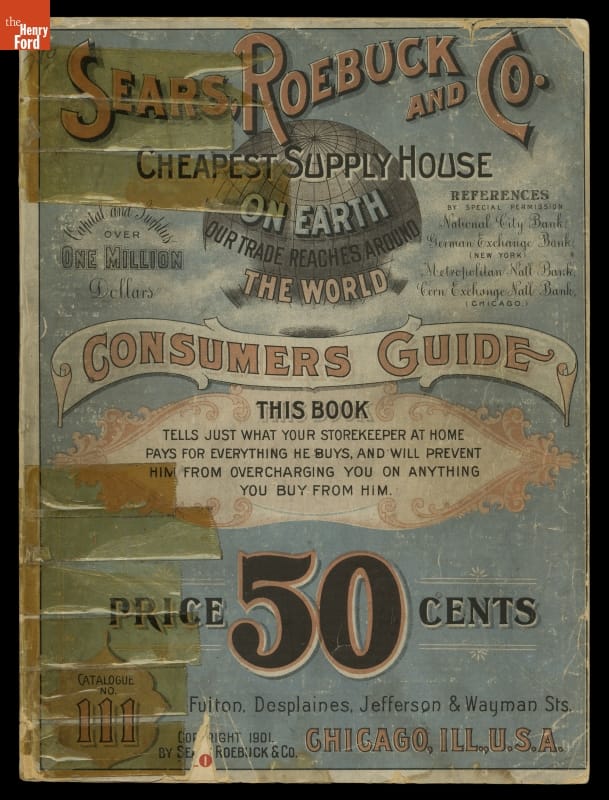

Sears, Roebuck and Company Mail-Order Catalog, "Consumers Guide, 1901," Catalogue No. 111

Mail order catalogs opened up the world of retail to families around the country. With thousands of items right at their fingertips this Sears and Roebuck catalog would give access to clothing, equipment, home goods, and everything in between to anyone in the United States. The Benson Ford Research Center now utilizes trade catalogs like this to document fashion and innovation of the time. - Sarah Andrus, Librarian

H.J. Heinz Company Collection

Expansion at the H.J. Heinz Company in Pittsburgh during the early 1950s looked to be the end for “The Little House Where We Began,” the small brick building where H.J. Heinz began his business and that had been moved by barge to Pittsburgh in 1904. To save it from demolition, the H.J. Heinz Company donated the building to the Edison Institute, where it was reconstructed in Greenfield Village as the Heinz House. Along with the building, the H.J. Heinz Company donated this sizable archival collection that includes photographs, advertising layouts, publications, scrapbooks, and business records, all of which help convey the history of the Heinz House, the H.J. Heinz Company, and other stories of innovation and entrepreneurship. - Brian Wilson, Senior Manager, Archives and Library

Ford-Ferguson Model 9N Tractor, 1940

The Ford Motor Company re-entered the tractor business in the United States in 1939 with the 9N, a Ford tractor with a 3-point hydraulic hitch-and-lift system invented by Harry Ferguson. After Edsel and Henry both died, Henry Ford II ended the Ford-Ferguson arrangement and released a new model, the 8N, marketed through the Dearborn Motor Corporation, not through Ferguson. Ferguson sued, and after four years he accepted $9.25 million paid by FMC to settle the patent-infringement case. This tractor was one of eight that FMC assembled for the litigation and then transferred to the Edison Institute to complete its display of Ford tractors. - Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1940s

Igor Sikorsky Landing the VS-300 Helicopter before Presenting it to Henry Ford Museum, October 7, 1943. THF118083

This year, Henry Ford’s museum and village complex – now known as The Henry Ford – celebrates its 90th anniversary. Throughout 2019, we’ll be reflecting decade-by-decade on significant additions to the collection he began, with a focus on our institution's evolving collecting philosophies. This post covers our history and acquisitions during the 1940s.

Edison Institute Schools Students in Class, Giddings Family Home, Greenfield Village, September 1944. THF126142

While the collection did continue to grow, the 1940s were quieter years for the museum and village. As World War II tooled up, activities and personnel were cut back, not as many visitors attended, and the Edison Institute school system, which peaked in 1940 with 300 students enrolled, was reduced in size.

Henry Ford and Former Colleagues at the Edison Illuminating Company Building Dedication, Greenfield Village, November 8, 1944. THF244447

Henry Ford added few new buildings to Greenfield Village, but he rounded out the representation of his personal history with replicas of the one-room Miller School he had attended, the Edison Illuminating Company power plant in Detroit where he had worked, and Ford Motor Company's Mack Avenue Automobile Plant (these last two at reduced scale). In 1944, Ford moved his childhood home – which he had painstakingly preserved on the family farm 25 years before – to Greenfield Village, assuring that it would be cared for after he was gone.

Henry Ford and Edsel Ford Visiting the Rouge Plant Tool and Die Shop Construction Site, June 16, 1938. THF116315

In 1943, Henry and Clara Ford’s only son, Edsel, who was an able and enthusiastic supporter of the museum and the arts in general, died of stomach cancer at the age of 49. Two years later, Henry suffered a severe stroke. On April 7, 1947 at the age of 83, Henry died at Fair Lane, his Dearborn home, with Clara by his side.

The passing of the Edison Institute’s founder begged the question “what next?” for the institution. Henry’s vision had been the driving force behind his creation. Who would drive that vision now?

Additions to the Collections: 1940s

Writing Slate, 1880-1910

As word spread of Henry Ford’s historical endeavors, people offered him objects that they themselves had gathered. In 1941, Ethel G. Douglas sent Ford over 2,500 objects “collected in several years travel.” Many of these - toys, games, clothing, dolls, and books - related to childhood, including this slate. Millions of kids used slates like this one in 19th century one-room schools. Henry Ford was one. For him, the slate might evoke personal memories, but also appreciation for traditional teaching methods these rural schools represented - and that he incorporated into his private Greenfield Village school system.

Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Centripetal Spring Chair from a Pullman Train Car, 1860-1880

This is the first attempt at a mass-produced, comfortable chair. It is supported by a series of springs which provides resilience, meaning that it "gives" with the weight of the sitter. When it was patented, this was a revolutionary achievement. This was the second in a series of centripetal designs by Thomas E. Warren of Troy, New York. Dating to 1852, this version was intended to smoothen out the inevitable bumps for passengers riding in a railroad car. Donated by the Michigan Central Railroad in 1941, the revolutionary nature of the technology was yet to be recognized by scholars.

Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

1939 Sikorsky VS-300A Helicopter

The Henry Ford's collecting efforts have never been confined only to faraway history. Contemporary collecting - of artifacts from the recent past or present day - has always been core to the institution's work. Henry Ford eagerly accepted Igor Sikorsky's VS-300A helicopter in 1943 - a mere four years after its first test flight. Like Sikorsky, Ford understood the helicopter's enormous potential. The gift was initiated by a mutual friend of Ford's and Sikorsky's who also recognized an aviation innovation when he saw one: Charles Lindbergh.

Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Folding Portable Spinning Wheel Used by Mahatma M. K. Gandhi

Henry Ford was an admirer of Gandhi's selfless life, self-reliant ideals and nonviolent principles. In July 1941, Henry Ford wrote a short note to Gandhi praising the "lofty work" of the Indian leader. Gandhi returned the compliment and sent a spinning wheel, or charkha, that he had used. Gandhi used the charkha as a symbol in India's struggle for independence and economic self-sufficiency.

Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Sampler Made for Henry Ford, 1943

Henry Ford received hundreds of gifts from admirers all around the world. Many of these gifts were made intricately and carefully by hand, like this embroidery sampler crafted by Ms. Ellen E. Merrow of Eagle Springs, North Carolina. The embroidered verse is a cautionary message that still feels relevant today – more than 75 years later.

Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Shards Found at Henry Ford's Birthplace, Dearborn, Michigan, 1860-1919

Henry Ford began his first restoration project in 1919 after a road extension required the moving of his dilapidated childhood home. Over the next few years, Ford meticulously refurnished the home to how it looked in 1876, the year his mother died. While employees combed the countryside for antiques, others excavated the original site for ceramic shards like this for reproduction. Even though this project launched Henry's passion for collecting, the Ford home and its contents, which included these shards, weren't moved to Greenfield Village until 1944 - the last building he personally had moved there.

Ryan Jelso, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Slippers, Worn by Sophia E. Ewing on Her Wedding Day, 1864

In 1940, a cartoon appeared in newspapers around the country. It emphasized Henry Ford’s unusual interest in artifacts from everyday life, rather than the fine art and antiques collected by other wealthy individuals. Text beneath an image of Ford holding a woman’s shoe read, “…he gets a whale of a kick out of collecting a sample of every type of shoe ever made in the U.S.!” In response to the cartoon, donations from readers – including this pair of wedding shoes worn in 1864 – poured in.

Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

George Washington Carver Cabin

George W. Carver and Henry Ford shared an interest in chemurgy or the chemical transformation of agricultural commodities into byproducts such as hydrogenated oils. Ford invited Carver to speak at the 1937 chemurgy conference in Dearborn. In 1942, Ford honored Carver with this replica of Carver's birthplace, paneled in wood donated by Boy Scouts from every state. Carver spent the night of July 21, 1942 in the building.

Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90