Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1950s

Henry Ford’s energy had been the animating force behind the Edison Institute. His death in 1947 challenged the institution to manage a collection that had grown to massive proportions – with no adequate storage solutions and no formal cataloging system.

Aerial View of Henry Ford Museum, circa 1953. THF112188

Clara Ford took over for her husband after his death, and the skeletal staff maintained the status quo at the Institute for the next few years without real direction. In 1950, the death of Clara signaled the end of another era. The Ford family stepped away from the daily management of the institution and began a strong tradition of lay leadership. In the early 1950s, all three of the Fords’ grandsons served on the Board of Trustees. William Clay Ford took over the position of board president in 1951 and remained chairman of the board for 38 years. Museum Executives and "Today" Show Staff after Live Broadcast from Greenfield Village, October 25, 1955. THF116184

Museum Executives and "Today" Show Staff after Live Broadcast from Greenfield Village, October 25, 1955. THF116184

In January 1951, the board appointed A.K. Mills to the new post of executive director of Greenfield Village and the Edison Institute Museum. He implemented business practices and hired professional staff members. During the 1950s, the public – especially the vast traveling public – became the focus of the institution’s attention. In 1952, as a tribute to its founder, the Edison Institute was renamed Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. Mills died suddenly in 1954; Donald Shelley replaced him as executive director, a position he held for the next 22 years. Industrial Progress U.S.A. Exhibit, Henry Ford Museum, 1952-1954. THF112172

Industrial Progress U.S.A. Exhibit, Henry Ford Museum, 1952-1954. THF112172

Traveling exhibits, developed by the institution in the 1950s, offered the museum a chance to promote itself beyond the local area, increase awareness, and increase visitation. Henry Ford Museum’s attendance steadily climbed each year. The number of visitors doubled over the decade, from 500,000 in 1950, to 1 million by 1960. The village and museum had become a national attraction.

Acquisitions to the Collections: 1950s

Walking Doll

In the 1950s, the museum’s curators acquired many objects for the collection through a network of antique collectors and dealers. Curators were especially looking for folk art and other “early American” objects. Collector Titus Geesey of Wilmington, Delaware had filled his home with three decades worth of collecting. Ready to pare down a bit, Geesey sold over 300 objects to the museum over the years, including prints, tableware, coverlets, a weathervane, and toys. This late 19th-century mechanical doll from Geesey’s collection came in 1958. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Moravian Bowl with Stylized Fish and Turtles in Center, 1810-1820

In the mid-20th century, Henry Ford Museum built on its early holdings to become one of the preeminent collections of American decorative and folk arts. This ceramic serving bowl was made by Moravian-German immigrants in Alamance County, North Carolina. The playfully arranged turtles and fish are unique representations in Moravian ceramics, which usually emphasizes abstract decoration. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

1941 Allegheny Steam Locomotive

It's perhaps the most photographed object in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, and certainly among the best-remembered by our visitors. The mighty Allegheny has anchored the museum's railroad collection since 1956. Used steam locomotives were a dime a dozen in those days as railroads switched to diesel-electric power. Some went to museums and some to tourist railroads. But many more went to city parks and county fairgrounds, left to the mercies of the weather. The Allegheny is a gem carefully preserved indoors for more than 60 years now -- four times longer than it actually operated on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

"Battle Scenes of the Rebellion" Battle of Gettysburg, Civil War Panorama"

In the 1880s, Thomas Clarkson Gordon (1841-1922), a self-taught artist and Civil War veteran, created a panorama depicting scenes from the Civil War. Gordon toured his 15-paneled panorama throughout eastern Indiana, retelling the history of the conflict through his vivid illustrations. In 1956, Thomas Gordon's daughters wrote to Henry Ford II, hoping he would want the panorama for his grandfather's "Dearborn Museum." The request was redirected to the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. The donation arrived in 1958. - Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Birth and Baptismal Certificate for Maria Heimbach, 1784|

German immigrants in Pennsylvania created fraktur – highly-decorated documents – to commemorate life’s most significant events. This particular fraktur is a Geburts-und Taufscheine – or a birth and baptismal certificate – and is the most common type. The name fraktur is rooted in a German calligraphic tradition and was primarily used for official documents. The Pennsylvania German frakturs continue this typographic tradition but expand upon it to create a new cultural tradition for a new homeland. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

1953 Ford X-100 Concept Car

During its 50th anniversary in 1953, Ford Motor Company celebrated the past and looked to the future. A. K. Mills -- former head of Public and Employee Relations and recently-appointed Executive Director of the newly-renamed Henry Ford Museum -- managed multiple anniversary projects. While Mills organized new exhibits, oral histories, books, films, and -- most importantly -- a company archive, Ford engineers completed a special project of their own. Their fully-functional concept car, known as the X-100, was showcased during anniversary celebrations and featured more than 50 futuristic innovations, including heated seats and a telephone. - Ryan Jelso, Associate Curator

Print of Mary Vaux Walcott Wildflower Sketch, "Trumpet Honeysuckle," 1925

Clara Ford was an active gardener who presided over several gardening organizations during her lifetime. Citing her interest in flowers, the William Edwin Rudge Printing House of New York sent Mrs. Ford a set of prints originally illustrated by Mary Vaux Walcott in 1925. (The gift also served to demonstrate the quality of the firm’s color reproductions.) When Clara Ford died in 1950, a group of items from her estate – including these prints – came into the museum’s collection. - Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

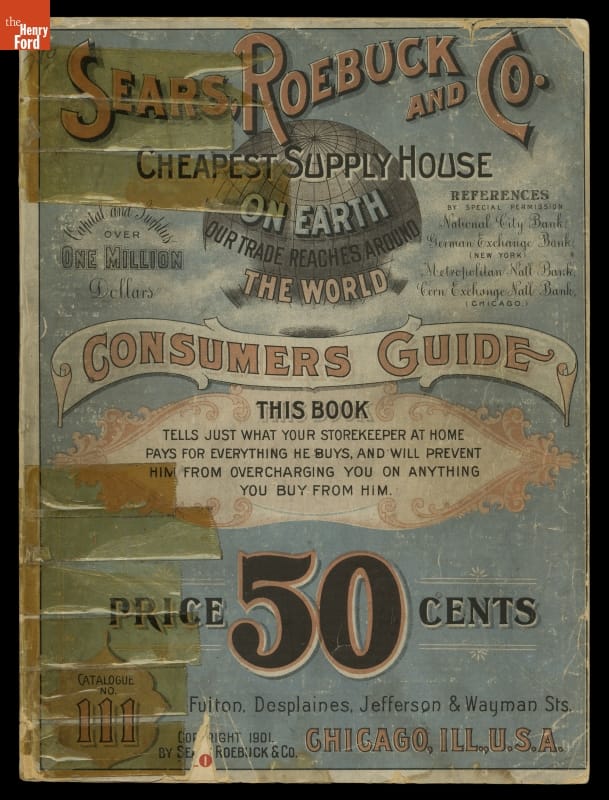

Sears, Roebuck and Company Mail-Order Catalog, "Consumers Guide, 1901," Catalogue No. 111

Mail order catalogs opened up the world of retail to families around the country. With thousands of items right at their fingertips this Sears and Roebuck catalog would give access to clothing, equipment, home goods, and everything in between to anyone in the United States. The Benson Ford Research Center now utilizes trade catalogs like this to document fashion and innovation of the time. - Sarah Andrus, Librarian

H.J. Heinz Company Collection

Expansion at the H.J. Heinz Company in Pittsburgh during the early 1950s looked to be the end for “The Little House Where We Began,” the small brick building where H.J. Heinz began his business and that had been moved by barge to Pittsburgh in 1904. To save it from demolition, the H.J. Heinz Company donated the building to the Edison Institute, where it was reconstructed in Greenfield Village as the Heinz House. Along with the building, the H.J. Heinz Company donated this sizable archival collection that includes photographs, advertising layouts, publications, scrapbooks, and business records, all of which help convey the history of the Heinz House, the H.J. Heinz Company, and other stories of innovation and entrepreneurship. - Brian Wilson, Senior Manager, Archives and Library

Ford-Ferguson Model 9N Tractor, 1940

The Ford Motor Company re-entered the tractor business in the United States in 1939 with the 9N, a Ford tractor with a 3-point hydraulic hitch-and-lift system invented by Harry Ferguson. After Edsel and Henry both died, Henry Ford II ended the Ford-Ferguson arrangement and released a new model, the 8N, marketed through the Dearborn Motor Corporation, not through Ferguson. Ferguson sued, and after four years he accepted $9.25 million paid by FMC to settle the patent-infringement case. This tractor was one of eight that FMC assembled for the litigation and then transferred to the Edison Institute to complete its display of Ford tractors. - Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Robert Propst: Unorthodox Thinker

Portraits of Robert Propst. THF137271

Portraits of Robert Propst. THF137271

PROFESSION: Designer (Although he preferred to be called "searcher")

INNOVATION: The Action Office II System (1968) and the movable "coherent structures” of the Co/Struc System designed for hospitals (1971)

ATTRIBUTES: Empathetic observer, serial problem solver, unorthodox thinker

You could be forgiven if you aren’t familiar with the work of Robert Propst. After all, if his designs were working as he intended, they simply disappeared.

Propst became director of the Herman Miller Research Division (HMRD) in 1960, setting up shop in a small concrete building in Ann Arbor, Mich. The founder of Herman Miller, D.J. DePree, saw potential in Propst’s ambitious thinking and hired him to broaden the company’s product range. Very few guidelines were in place at HMRD: Nothing should be connected to military use, no furniture designs — and whatever was designed should simply “be useful.” Robert Propst Outside Herman Miller Research Division Office, Ann Arbor, Michigan, July 1964. THF137214

Robert Propst Outside Herman Miller Research Division Office, Ann Arbor, Michigan, July 1964. THF137214

Deliberately choosing a building more than 150 miles away from Herman Miller’s headquarters in Zeeland, Mich., Propst exercised his freedom to research without the distraction of corporate meetings. For every idea he had that went into production, hundreds more were filed away.

Two of Propst’s most impactful projects were holistic environments designed for high-impact workplaces: the improved Action Office II system (1968) and the movable “coherent structures” of the Co/Struc system designed for hospitals (1971).

In Propst’s mind, offices had become chaotic wastelands. Cobbled together furniture, nonergonomic chairs and an invasion of technology onto ad hoc surfaces. Action Office — a modular system of free standing panel walls — could be fluidly arranged into nooks for working, conference areas and other purpose-driven needs. An idealistic vision for the birth of the modern office cubicle.

Propst wasn’t always a designer of “things” but of situations. He attacked issues from the reverse, finding clues in the algorithms of human behavior working in high-stakes spaces. How did people move while working? Where was time being spent? Wasted? How can we support safety? Privacy? Collaboration? The physical solutions he engineered encouraged ideas of access, mobility and efficiency. His modular approach to office landscapes was intended to have a 1 + 1 = 3 effect. Which is to say that by implementing physical change, “knowledge” workers could then springboard off an improved relationship with their workspaces, which were suddenly more hospitable to launching new ideas, productive workflows and transformative projects. Action Office Project Drawing by Robert Propst, April 6, 1964. THF241708

Action Office Project Drawing by Robert Propst, April 6, 1964. THF241708

Did You Know

- The proliferation of the office cubicle is almost single-handedly due to the introduction of the Action Office II system in 1968. Unfortunately, the mobile aspect of Action Office became rooted to the floor, quite literally. Large businesses filled their buildings with Action Office (or its various knock-offs) to create Dilbertesque “cubicle farms.”

- The first version of Action Office was conceived by Robert Propst and designed by George Nelson in 1964, but sales were lackluster. Corporate managers worried about the porous borders being offered to their staff, now called “knowledge workers,” and the cost was simply too high. Propst returned to the drawing board alone for AO2.

- Robert Propst did not like to be referred to as a designer. He also didn’t like the term “researcher,” because it implied looking backward. His ideal description for his activities was “searcher.”

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from an article in the January-May 2019 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Herman Miller, The Henry Ford Magazine, by Kristen Gallerneaux, Robert Propst, furnishings, design

The Tale of the Nauga’s Hide

Naugahyde Advertisement in Life Magazine, October-December 1967. This image is not an original photograph and is a combination of two images created for illustrative proposes.

The Nauga, a colorful, horned, happy-looking creature native to the island of Sumatra, was once hunted to near-extinction. They were hunted for sport, but more often for their smooth and durable leather-like hide – Naugahyde, as it’s generally known. However, hunting a Nauga for its hide is quite unnecessary -- they painlessly shed their hide at least once each year for use in furniture, clothing, and more.

Wait a minute.

You’ve never heard of the Nauga?

All right, you’ve got me. The Nauga is a fictional creature. It was an advertising gimmick created to help Uniroyal Engineered Products promote their soft vinyl-coated fabric that feels like leather but is more durable. The product, Naugahyde, was used primarily as upholstery in the furniture industry, but also was used for clothing, shoes, accessories and other home goods. Its success spawned many imitators. In the mid-1960s, Uniroyal hired legendary ad-man George Lois and designer Kurt Weihs to craft an advertising campaign to differentiate their product from the competition. And what did Lois and Weihs create? The Nauga.

A humorous ad campaign featured the Nauga engaged with the world – as the life of the party, as a child’s play companion, adorned in splattered paint from a craft went awry, even as a vacationer readying for travel with golf clubs in hand. These advertisements emphasized the suitability of Naugahyde upholstery for all areas of life, claiming it could be indistinguishable from other fabrics like leather, tweed, or silk -- but “last about ten times as long.” An image of the Nauga found its way onto hang-tags that accompanied all genuine Naugahyde products. Many of the ad campaigns ended with this directive: “If you can’t find the Nauga, find another store.”

Naugahyde advertisement in Life Magazine, July-September 1967.

The advertising worked – at least in that it caused excitement over the mysterious Nauga creature. Allegedly, some people even believed Naugas were real creatures and became concerned about inhumane treatment as the use of Naugahyde boomed in the late 1960s. A New York comic, Al Rosenberg, invented a fictional character named Earl C. Watkins who spearheaded the “Save the Nauga” project to protect the species from extinction, adding that a “herd of Naugas is often mistaken for a roomful of furniture.'' The Nauga even made an appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Nauga dolls, like this one in The Henry Ford’s collection, were also produced to promote the brand. In fact, if you visit the Naugahyde website today, you can still “Adopt a Nauga,” which, according to the company’s webpage, are bred on a ranch outside Uniroyal’s headquarters in Stoughton, Wisconsin.

Uniroyal "Nauga" Toy, 1955-1975

It isn’t unusual for companies to go to great lengths to endear a product to the public. These efforts have often yielded highly creative and memorable results, like Oscar Mayer’s Wienermobile, the Heinz pickle charms and pins, or the Pets.com Sock Puppet, to name a few. While the Nauga creature has faded nearly into obscurity, the leather-like product it represents lives on…perhaps even as the upholstery of the chair you’re currently sitting on.

Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford, recently adopted a Nauga doll of her very own.

toys and games, by Katherine White, advertising, furnishings

In the 1980s, desktop computers emphasized non-committal, neutral shades: beige, off-white, black, and the just-barely-greys of putty and fog. During a time when popular culture included the flashiness of MTV, new wave music pressed onto colorful records, and hip hop culture--why so much beige?

Truthfully, home computers were becoming more common, but the largest market remained in office environments. Neutral computers provided visual unity among cubicles, and masked aging plastic.

IBM Personal Computer, Model 5150, 1984. THF156040

The Apple Newton eMate was one of the first personal computers to break away from the typical form of the "opaque beige box."

Apple eMate 300, 1997. THF172045

The eMate's distinctive translucency was soon echoed by Jonathan Ive in his radical case design for the iMac G3 computer. From 1998-2001, the iMac was available in an array of 13 colors--from Bondi Blue to Flower Power.

View all 13 colors of the Apple iMac in The Henry Ford’s digital collections.

This post features objects and text displayed in the 2018 pop-up exhibition Looking Through Things: Transparent Tech, Fashion, and Systems at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

Archival Inspiration: Decorating for Easter

Many of us celebrate Easter with a number of traditions: dyed eggs, baskets full of candy, or decorations inspired by spring, just to name a few. Many of these traditions go back in history more than 100 years.

At Edison Homestead in Greenfield Village, we showcase a variety of activities during the Easter weekend that would have been enjoyed around 1915. Where do we find our inspiration? Much of the instructional information used to plan these activities come from promotional booklets from companies like Dennison Manufacturing Co. and their Dennison’s Party Book, or from magazine publications like the Ladies Home Journal, both available to families at the time.

In 1915, Easter crafts ranged from decorative pieces for the table to edible delights. Dennison Manufacturing Co., which today is now known as Avery Products Corporation, was a large supplier of inexpensive paper products that encouraged decorations for any number of parties, including an Easter celebration. Listings in the Dennison’s Party Book contain a rabbit with basket of eggs decoration, decorated crepe paper, bon bon boxes, and purple and white festoons, all of which were priced at 25 cents or less. They also suggest how a table might be decorated using the items they have listed for sale as well as homemade items (made of paper, of course).

Easter cards are one of the projects suggested in The Ladies Home Journal, 1912 April edition, and would have been an inexpensive craft to make as a gift. In fact, the journal states that, “[Easter] gifts should always be simple and inexpensive; if they are made rather than bought, so much the better.” Using images from flower catalogues, garden and agricultural magazines, the picture is traced on a folded edge of thick paper to create the body of the card. Once cut out, the image is then colored in and an insert is created to write an Easter note to the recipient.

Like our own Easter traditions today, the journal included many references to sweet treats that could be given as gifts. Chocolate eggs could be made by carefully removing the raw egg from the shell, washing the shell, then filling it with melted chocolate. Once cooled, the egg shell could be colored and decorated with crayons and colored pencils, with a scrapbook pictured glued over the opening. Not only were sweets made, but so were displays to put them in. Moss glued onto a half egg shell provided a holding space for small candy eggs or jelly beans.

Feeling inspired and ready to try creating your own archive-inspired holiday decorations? Stop by the Benson Ford Research Center to see a copy of the Dennison's Party Book for yourself.

Emily Sovey is Supervisor of Inspiring and Living History at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1910s, research, making, home life, holidays, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Easter, by Emily Sovey

Keeping the Roundhouse Running

As any member of the railroad operations team in Greenfield Village will tell you, there’s never a shortage of work to be done at the roundhouse. Learn more about a typical day of making sure everything is running smoothly from early in the morning to late in the evening.

The beginning of a day in railroad operations starts when the scheduled fireman arrives at 6:30 am in the morning. Upon arriving he’ll look over the day’s locomotive for anything that might be out of place. When he’s satisfied, he will begin by cleaning the remnants of the previous day’s fire from the firebox.

A fresh bed of coal will be laid down and he will then light a new fire. For the next two hours, the fireman will continue to tend this fire as the boiler builds steam pressure. He will also fill oil cans, clean the cab, and tidy up in general around the engine. At 7:00 am, the morning mechanic reports for duty. He’ll wash and assist in oiling the engine.

The morning mechanic is also present for any mechanical failures that may arise as the locomotive “wakes up.” At 7:30 am the engineer arrives; he starts his day by inspecting the passenger cars that will be pulled behind his locomotive. After this, he will proceed to the locomotive and look the engine over before beginning the process of oiling and greasing. Around 8:45 am the fireman will have the boiler near operating pressure; at this time the locomotive is ready to start its day. The engineer with fireman onboard will take the locomotive from the roundhouse area out onto the railroad to retrieve the train cars. Once coupled up, a test of the air brakes and a final inspection is performed. This is done to ensure that the brakes are operating correctly.

At 9:00 am the conductor reports for duty and boards the rear of the train, which then proceeds up to Firestone station to receive the first passengers of the day.

Did you know that the train will make 13 trips around the railroad in a single day, covering just over 30 miles? Amongst these trips the engine crew takes on water four times and will take on coal only once. Throughout the day the fireman will maintain a steady, hot fire, adequate steam pressure, and a safe water level in the boiler.

The engineer will replenish oil and grease to important components of the locomotive, as well as ensure a safe and comfortable ride to our passengers.

Meanwhile, back at the shop, our mechanical department will perform various duties to keep the railroad up and running.

These duties include rebuilding spare parts, manufacturing new parts, boiler washes, boiler water testing, and disposing of dumped ash; just to name a few. Like we said, there is never a shortage of work to be done at the roundhouse.

Finally, the engine will be parked next to the roundhouse on the washing rack. Its boiler will be topped off with water and a large mound of coal, known as a bank, will be shoveled into the firebox. With the smokestack nearly capped, allowing only a small amount of smoke to escape, the bank will slowly burn overnight, maintaining a small amount heat in the boiler. The evening hostlers normally finish their day at 6:30 in the evening. However, this can be much later depending on the extent of needed evening repairs; every day on the railroad can lead to something new.

Mac Johnson is Roundhouse Foreman at The Henry Ford. Matt Goodman is Assistant Manager of Railroad Operations at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Canadian Pacific Snowplow, 1923

- Railroads

- Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Passenger Coach Replica

- Garage Art

by Matt Goodman, by Mac Johnson, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, trains, railroads

It’s not every day that you get to see a newly acquired artifact in action – in Greenfield Village just weeks before the opening of the 2019 season.

Meet the 1971 Wooster, Ltd. Sno-Bob, recently acquired by The Henry Ford. A Sno-Bob, also referred to as a ski bike, ski bob, or ski toy, is a bicycle frame attached to skis instead of wheels, or sometimes to a set of foot skis. The origins of bicycle-ski contraptions like the Sno-Bob date back to the mid-1800s. Equipped with real skis and a steering system to give the rider more control than a standard sled, the Sno-Bob is a unique offering in the world of winter toys.

The Sno-Bob isn’t just a fun winter-themed toy, it’s a bit of a rare find for our collections. As a society, we don’t buy as many snow toys to begin with, let alone save them to be possibly donated to a museum in the future. The Sno-Bob also has a connection to the Beatles, too: those loveable Liverpudlian mop tops ride Sno-Bobs in the Austrian Alps during the “Ticket to Ride” sequence in Help!, their second movie.

While not quite the Austrian Alps, you can see our Sno-Bob in action in Greenfield Village earlier this winter as Conservator Cuong Nguyen takes it out for a spin. While we generally don’t “play” with the artifacts in our collection, we feel that this toy is unique enough to justify video documentation showing how it’s used. (We’re fortunate that the weather cooperated with our plans this winter.)

2010s, 21st century, 20th century, 1970s, winter, toys and games, by Matt Anderson, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Charisma Tatum, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Rural America Shops by Mail

With mail order catalogs, rural Americans could choose from among a much wider variety of goods than at their local general store. THF119939 and THF115221

Today, shopping opportunities are everywhere—as a way to purchase things we need, as well as leisure time entertainment. We cruise the mall, trod the aisles of big-box stores, browse the shelves of trendy boutiques, roll our carts down the grocery store aisle, stop off at the convenience store, flip through store catalogs delivered to our door, and shop online. We can even shop from the convenience of our smartphone or tablet. Shopping is now a 24-7 opportunity filled with endless choices of goods made all over the world.

During the late 19th century, things were quite different. Most Americans lived on farms or in small villages--shopping choices were limited. Yet, the advent of mail order shopping was opening up a world of new possibilities.

Shopping Locally

Where did most rural people shop during the late 19th century? Usually the small stores located at a nearby village or town or perhaps a general store located at a country crossroads. These stores provided a narrow selection of items that served the needs of the locals, yet offered shoppers the tactile experience of handling the goods before deciding to purchase. Factories were turning out consumer goods of all kinds, advertising trumpeted the merits of the products to potential customers, and railroads made it easier to get those goods to rural stores as well urban ones—so rural shoppers in America’s hinterland could obtain some of the same or similar items found in the city.

Still—small town shopkeepers couldn’t afford to stock an endless variety of merchandise to broaden their customers’ choices. So, instead of selecting from dozens of shoe styles or tableware patterns, or printed fabric designs, rural customers often made their choices from whatever goods were at hand in the local merchant’s store.

Mail Order Shopping Debuts

During the final decades of the 19th century, America’s farmers developed a growing discontent towards institutions they felt were stealing too large a share of their hard-earned profits: “middlemen” like the grain elevator operators who they felt were paying too low a price for their crops and the storekeepers who they felt charged them too high a price for the goods they bought at retail. Farmers organized themselves into “the Patrons of Husbandry,” also known as the Grange, to protest these inequities as well as seek opportunities to form cooperatives through which they could purchase goods at wholesale prices.

Aaron Montgomery Ward of Chicago recognized that his innovative idea for direct-mail marketing meshed well with this growing discontent on the part of farmers. In 1872, Montgomery Ward & Company launched what would become the first general mail order company in American history. Advertising his company as “The Original Wholesale Grange Supply House,” Ward stated that the firm sold its goods to “Patrons of Husbandry, Farmers and Mechanics at Wholesale Prices.” His recipe for success—high volume, a wide selection of goods, ease of handling, and low prices—enabled Ward to extend the advantages found in urban marketplace directly to rural customers.

As Montgomery Ward & Company’s mail order business quickly grew, other companies joined in. The other mail order giant, Sears, Roebuck and Company, also located in Chicago, began offering mail order in 1888. By 1900, these two mail order houses were the two greatest merchandisers in the world. Countless other firms offered a variety of goods from ready-made clothing to hardware and farm equipment, using the direct-marketing of mail order to extend their reach to customers all over the nation.

Mail order catalogs brought city and country together. The enticing products shown on their pages represented the new and modern to their rural readers, promising higher standards of living and material progress through the attractive goods and labor-saving devices displayed there. Mail order catalogs offered rural residents a “taste” of the urban experience, offering goods found in the shops and department stores that blossomed in the commercial districts of America’s burgeoning cities. Catalogs, of course, broadened the merchandise selection for some city people as well.

Montgomery Ward & Company launched America’s first general mail order company. Over 22 years later, their 1894-1895 catalog still proudly trumpeted this fact: “Originators of the Mail Order Business.” THF119789

A Cornucopia of Material Delights

Flipping through these mail order catalogs brought a visual feast of tens of thousands of products—some satisfying needs and some gratifying wants. For a farm family whose lives and daily activities brought little variety, these catalogs opened a world of new material possibilities: fashionable ready-made clothing, hats and hat trimmings, jewelry of all kinds, sewing machines, cook stoves, and hardware for use on the farm or stylish hinges to update farmhouse doors. Even carriages and automobiles could be shopped for by mail.

The northern Indiana family shown in this circa 1900 parlor photograph could have obtained many of the goods by mail order—even the piano. THF119591

The photograph above depicts a middle-class family from a farm or small town surrounded by the mass-produced goods that provided an attractive, comfortable lifestyle. Many of the items could have been purchased from a mail order catalog. (Keep in mind that, while rural residents might have access to many of the same goods, they often had far less spending power than urban America.)

Delivering the Catalogs—and the Goods

From placing the order to delivery of the goods, the image on the cover of this 1880s Jordan Marsh catalog suggests the ease of “successful” shopping by mail—allaying any concerns for those new to the process. THF119786

Mail order catalogs came to farmers—not surprisingly--through the mail. Yet, for many years, that did not mean convenient delivery to their doorstep. Though city dwellers had enjoyed free home delivery of mail since 1863, rural residents still had to pick up their own mail at the nearest post office—even though they paid the same postage as the rest of the nation. Bad roads and distance often meant that farmers rarely picked up their mail more than once a week. So placing a catalog order could take longer for farm folk than city dwellers. A farm family might pick up a catalog on a trip to town one week, then place the order the next time someone went to town. Payment for mail orders was made by money order, purchased through the post office.

In 1896, the success of mail order retailing helped encourage the introduction of rural free delivery, which began as an experiment with mail being delivered at no charge to customers on a few rural routes. Delivering mail throughout the countryside soon proved successful and sustainable, and additional routes continued to be added. In July 1902, rural free delivery became a permanent service. Now all rural Americans enjoyed mail delivery to their homes, opening their mailboxes to find not only letters from family and friends, but a growing number of mail order catalogs presenting enticing goods for their consideration.

How did merchandise ordered get to the person who ordered it? Before the advent of rural free delivery, people could pick up small packages at the post office. Private express companies delivered larger packages shipped to the nearest railroad station, transporting them to the customer’s home. Farmers might use their own wagons to transport goods shipped by rail to them.

Heavy or large packages sent by mail were shipped to the local railroad station. An express company would then deliver them to the customer. If the customer owned a horse-drawn wagon, they might pick up the package at the railroad station themselves. THF204912

After the beginning of rural free delivery, mail carriers delivered packages weighing up to four pounds to their customers’ mailboxes. By law, heavier packages had to be delivered by private express companies.

In January 1913, the U.S. Postal Service established parcel post—now goods could be delivered directly to homes. It was an instant success, boosting mail-order businesses enormously. During the first five days of parcel post service nearly 1,600 post offices handled over 4 million parcel post packages. Within the first six months, 300 million parcels had been delivered. Weight and size limits were gradually expanded. By 1931, parcel post deliveries included packages weighing up to 70 pounds and measuring up to 100 inches.

In the early years of rural mail delivery, farmers could use whatever was at hand as a mailbox—pails, cans or wooden crates. When rural free delivery became permanent and universal in 1902, the United States Post Office required rural customers to have regulation mailboxes in order to receive their mail. THF158049

Something Gained, Something Lost

While catalog shopping brought variety and convenience to rural Americans during the late 19th and early 20th century, there was an important trade-off. The face-to-face communication and personal relationship that had existed between a local storekeeper and his customers was eroding, helped along by national advertising which told potential customers what to buy—rather than customers seeking the advice of the storekeeper. Too, stores became increasingly self-serve. This trend toward less personal, “non-local” shopping continued to grow throughout the 20th century for rural and urban people alike, involving not only orders by mail, but by phone and, eventually, the internet. In the 21st century, sales of consumer goods increasingly take place online.

Yet, more recently, people have come to value the attentive personal service offered and unique goods stocked by many local retailers. Many shoppers combine the advantages of shopping online for the wide variety goods available there, with the personal touch and service-oriented experience of shopping locally. Encouraging this shop-local trend are national campaigns like Small Business Saturday, which takes place Thanksgiving weekend, encouraging shoppers to patronize small retailers.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

shopping, by Jeanine Head Miller, 20th century, 19th century

Americans Adjust to Microwave Cooking

Microwave ovens gained popularity in the 1970s, becoming all but standard in American kitchens by the mid-1980s. These new appliances cooked food differently than conventional stovetop or oven methods, which worked by surrounding food with heat. In a microwave oven, electromagnetic waves caused food molecules to vibrate, creating heat that transferred from the outside to the center of the food.

Foods cooked much faster in microwave ovens than in conventional ones. For example, microwaving reduced the cooking time for a baked potato from 75 minutes to just four. And frozen meat pies, which could take 45 minutes to bake, would be ready after nine minutes in the microwave.

This time-saving cooking method promised convenience, but it took some getting used to, requiring adjustments to cookware and cooking techniques. Glass and plastic transmitted electromagnetic waves in microwave ovens, but metal reflected them, causing sparks that could damage the appliance or even cause a fire. Manufacturers had to develop heat-resistant cookware and cooking utensils safe for use in the microwave.

With specialized cookware and new cooking techniques, Americans could microwave a variety of foods (including fish) quickly, with familiar results. THF174103

In addition to purchasing microwave-safe cookware, Americans needed to learn new cooking techniques. Familiar foods required different preparation -- eggs had to be removed from shells and stirred to break the yolks, and potatoes needed to be pierced before cooking. People also had to change their expectations, as microwave cooking didn’t brown or crisp many foods the way conventional methods did. Meat could be cooked in the microwave -- with varying results. Specialized browning skillets provided some familiar texture and flavor to meats that would otherwise seem limp and unappetizing.

Microwave manufacturers included instruction manuals and recipe suggestions with the ovens they sold. Cookbooks also helped home cooks adjust. Some offered information on how to convert conventional recipes for microwave cooking, while others focused solely on recipes created specifically for the microwave. Two booklets from the collections of The Henry Ford offer a look at the early decades of microwave cooking in America.

Some manufacturers published microwave cookbooks to promote their products. From Freezer to Microwave to Table (1978) encouraged people to use Amana microwaves and freezers and cover foods with Saran Wrap. Recipes in Campbell's Microwave Cooking (1987) called for ingredients made by the Campbell Soup Company.THF275056 and THF275081

Microwave cooking required people to arrange, stir or turn, and cover food differently than with conventional methods. Cookbooks describing these techniques helped Americans adjust. THF275059 and THF275060

This brownie recipe reminded cooks to use heat-resistant glass dishes and included instructions for melting, baking, defrosting, and reheating in the microwave. THF27506

This omelet recipe with an Italian twist emphasized convenience and efficiency. It called for store-bought spaghetti sauce and required only two dishes for cooking--one of which, according to the suggestion highlighted in yellow, could be reused to sauce and serve pasta. THF275089

View these and other cookbooks at the Reading Room in the Benson Ford Research Center, and browse objects related to microwave ovens in our Digital Collections.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

recipes, by Saige Jedele, by Jeanine Head Miller, home life, making, food

Since the dawn of motorized transportation at the turn of the 20th century, buses have been part of America's transportation network. Bus routes have crisscrossed the nation, providing affordable connections to thousands of American cities and small towns. Buses have carried workers to their places of employment, shoppers to downtown stores or suburban malls, and children to school. They’ve shuttled people from the airport to the rental car agency or parking lot. And leisure travelers have boarded buses to explore the wonders of nature or enjoy the adventures offered in urban environments.

In 2009, The Henry Ford acquired the unique collection of internationally-renowned author and photographer Bill Luke, for whom buses were a personal passion as well as a career.

Bill Luke became a devotee of buses and bus travel at a very early age. He was born in Duluth, Minnesota, an area noted for several early bus companies, including Greyhound and National City Lines. As a kid, Luke became fascinated with the history and activities of these major lines. He started collecting bus memorabilia and then began a career in the bus industry, working for the Jefferson Transportation Company in Minneapolis and, later, for the Empire Lines in Spokane. Until 1996, Luke also published a well-known bus and motor coach trade publication, Bus Ride, which covered the people, products, and services in this ever-evolving industry.

Luke's collection is filled with photographs, periodicals, and ephemeral material such as uniform patches, tickets, company publications, timetables, and route maps for bus lines operating throughout the United States. “Hop aboard” and explore some selections from the William Luke Bus Collection (all items gifts of William Luke):

Greyhound held the transportation contract for the 1933-1934 Chicago World's Fair. Sixty futuristic “trailer coaches” transported fairgoers to displays and attractions during the fair. THF108449

In this late-1920s photograph, Greyhound bus drivers pose in new uniforms. Uniform jackets, pants, caps and boots gave drivers a professional appearance, implying that -- with these experts at the wheel -- Greyhound riders would enjoy a safe and comfortable trip. THF108451

Helen M. Schultz started the Red Ball Transportation Company in 1922. Her bus route ran from Waterloo to Des Moines, Iowa. Schultz met many challenges while establishing her business, including competition from rival bus lines and the railroad, government regulations, and poor highway conditions. She sold Red Ball to the Jefferson Highway Transportation Company in 1930. THF108453

Bus terminals of the 1920s and 1930s were often located in hotels. The Pickwick organization, which owned the Pickwick bus line, commonly built terminals adjacent to or inside its hotels, like this one in Kansas City. The bus terminal located on the first floor featured a turntable that rotated buses 180 degrees within a narrow space -- allowing buses to exit the same way they entered. THF108455

Bus stations were often attractive as well as practical. Many terminals of the 1930s and 1940s sported streamlined facades -- the height of modernity during this time. These images of a Detroit terminal appeared in the 1941 book "Modern Bus Terminals and Post Houses," which featured photographs and floor plans of 45 recently-built bus stations. THF108459 and THF108460

Bus Transportation magazine sponsored a yearly contest for bus terminal window displays promoting the industry. This entry, a 1940 winner, enticed viewers to dream of a Michigan vacation enjoyed while traveling on the Blue Goose line. The judging staff called it "a highly original design with 'stop and look' appeal." THF108462

Many long-distance bus companies operated special restaurants to service their travelers. This 1955 menu explains that Greyhound established its Post House restaurants -- named after stops along stagecoach routes where travelers could rest, eat, and possibly even secure lodgings -- to guarantee quality food and sanitary conditions. THF108464

This 1980 photograph shows rapid transit buses -- part of an order for 940 vehicles bound for the Southern California Rapid Transit District in Los Angeles, California -- on the assembly line at General Motors’ Truck & Bus Division in Pontiac, Michigan. THF108469

Bus Ride magazine kept readers apprised of developments in the bus industry, including new technologies, changing regulations, and the evolving travel market. The William Luke Bus Collection includes a complete run of Bus Ride from 1967 to 2012, providing a glimpse into decades of opportunities and challenges in the bus industry and historical information about individual bus lines. THF108470

For more information about the William Luke Bus Collection, please contact The Henry Ford's Benson Ford Research Center. A version of this post originally ran in 2013 as part of our Pic of the Month series