Posts Tagged edsel ford

Clara Ford’s Travel Diaries

When traveling today, it is easy to document our journey through swift clicks of our phones and cameras. The people, sights, and sounds of a moment are captured and recorded through photos, videos, and social media posts making it easy to reflect on where we were and what we enjoyed.

The desire to document a memorable trip has remained a common tradition and in the age of Clara Ford, was accomplished through travel journals or diaries. Even with the advent of photography, film had to be thoughtfully allocated to document the most meaningful memories from a trip.

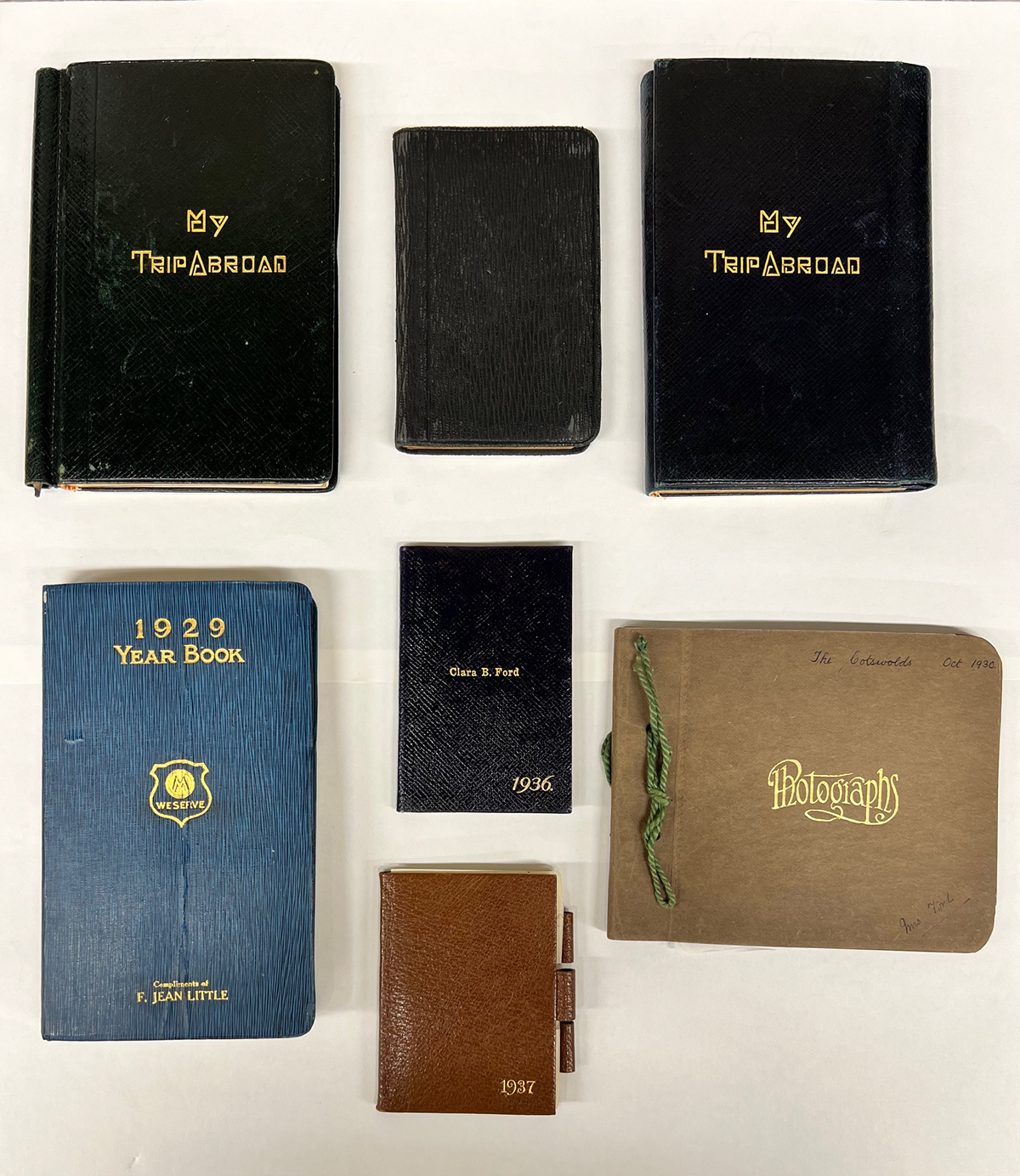

The Henry Ford's collections include several travel diaries written by Clara Ford dating from 1912 to 1945. Clara did not keep a diary for every trip she took. As the wife of Henry Ford, her travels were frequent and varied. Most of the diaries document her travels overseas, a momentous journey for anyone at that time, and winter retreats to Richmond Hill, Georgia, and Fort Meyers, Florida.

Clara Ford Travel Diaries. Accession 1, Box 105 and 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Unlike social media posts, travel diaries were not always intended for sharing or future publication. Entries were meant to document travel details and for personal reflection.

This means the writer was often sharing their thoughts more freely. For a notable figure like Clara Ford, travel diaries provide insight into her personal opinions and interests that might have been left out of an official record of her travels. They also provide a valuable record of Clara at a given time and place. They tell us who she interacted with, where she stayed, and what she saw.

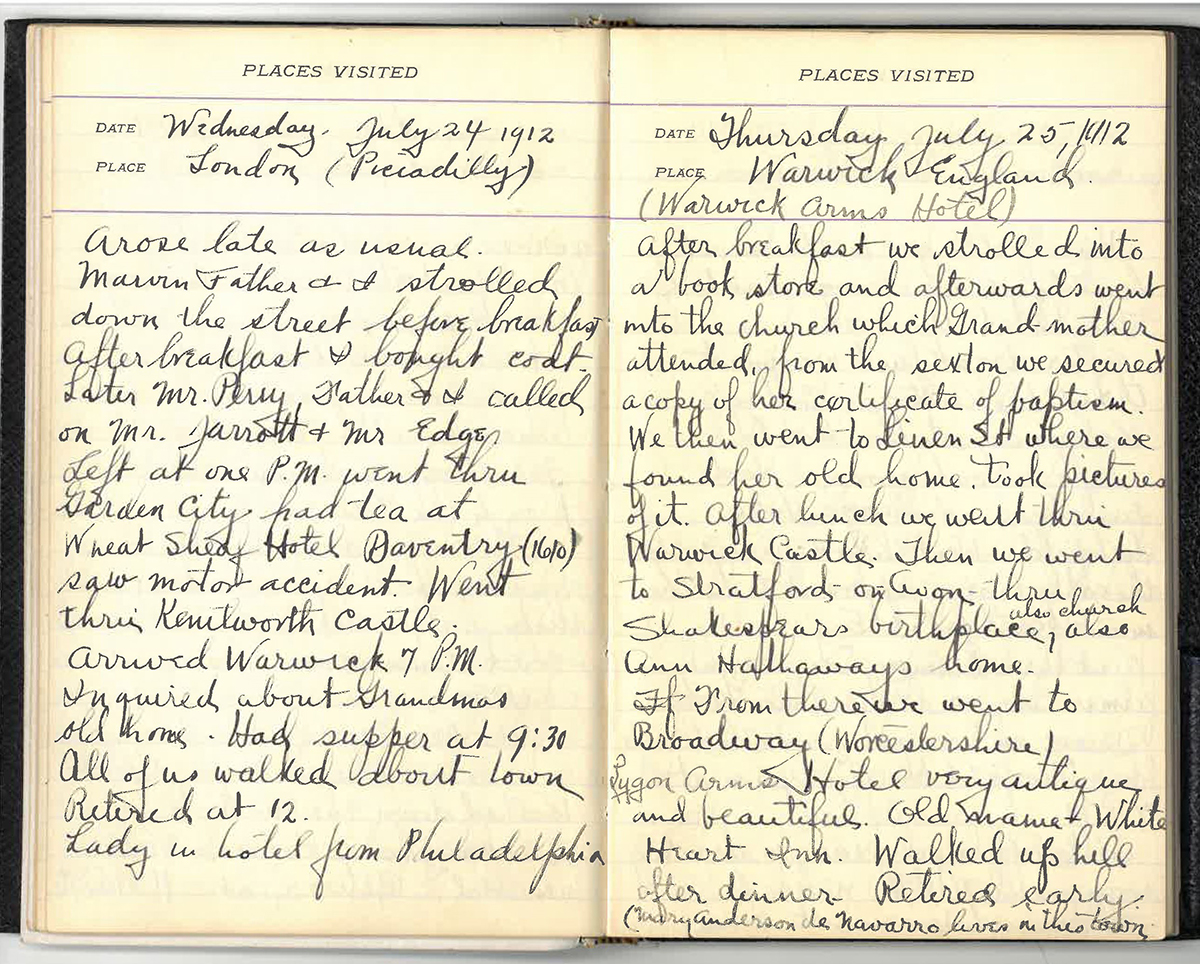

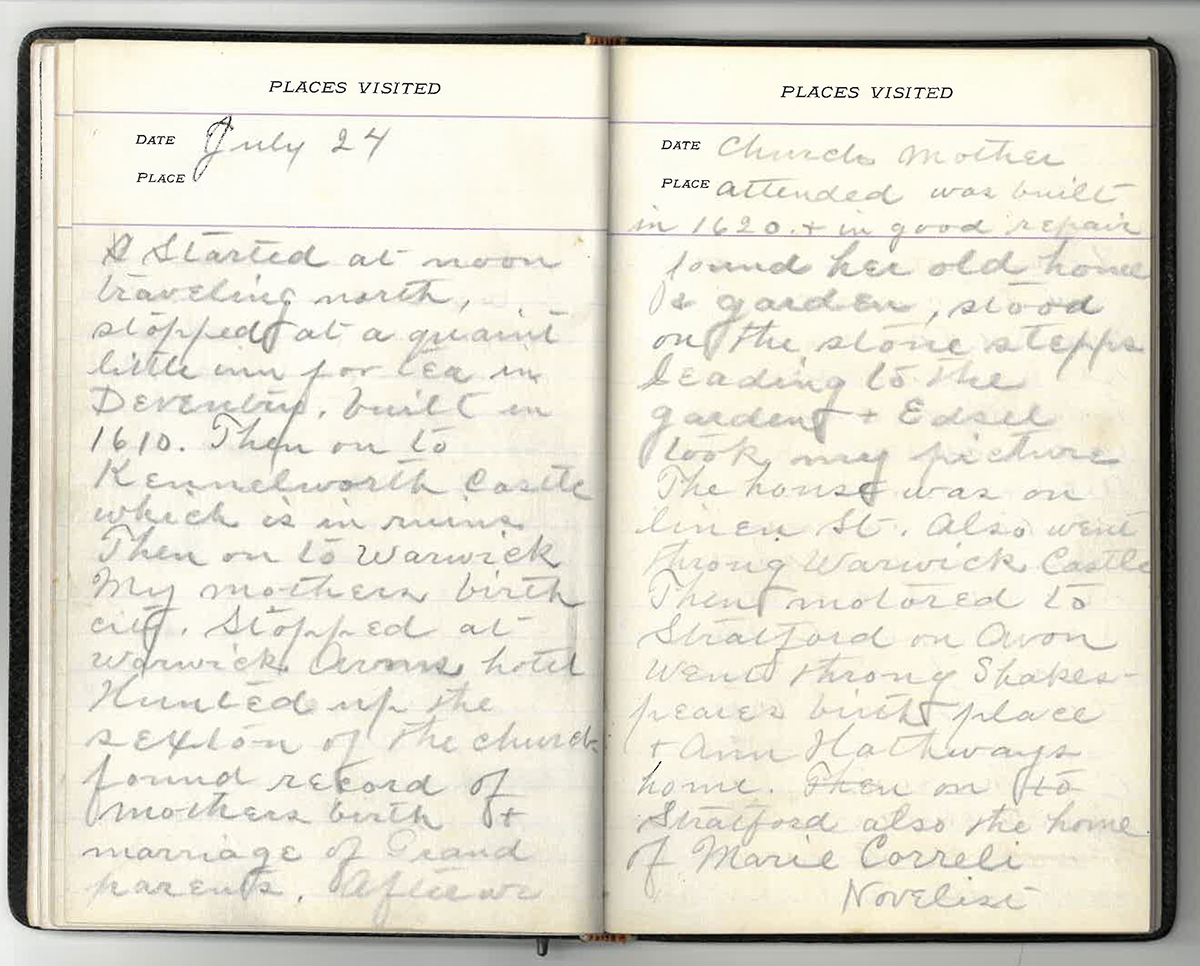

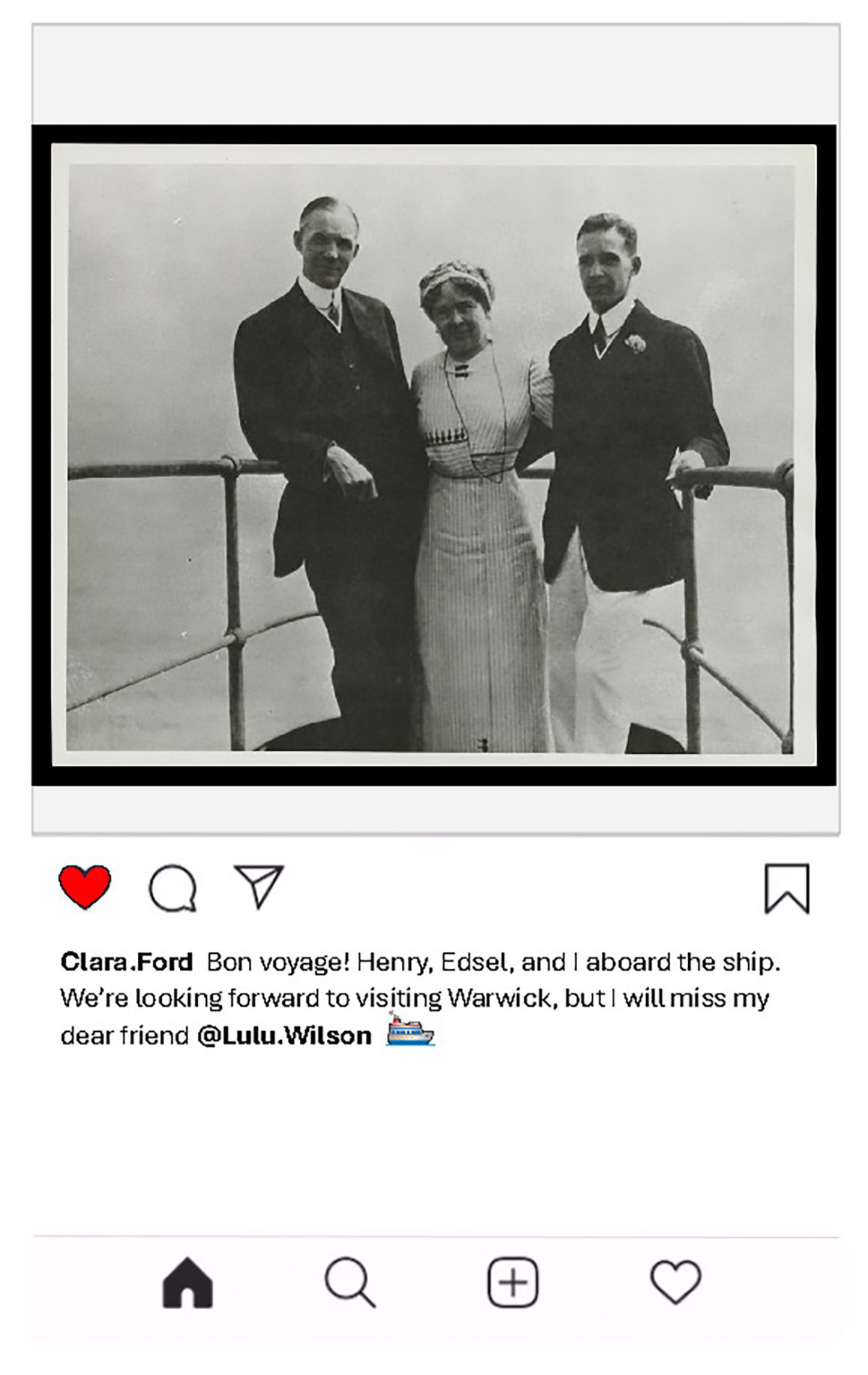

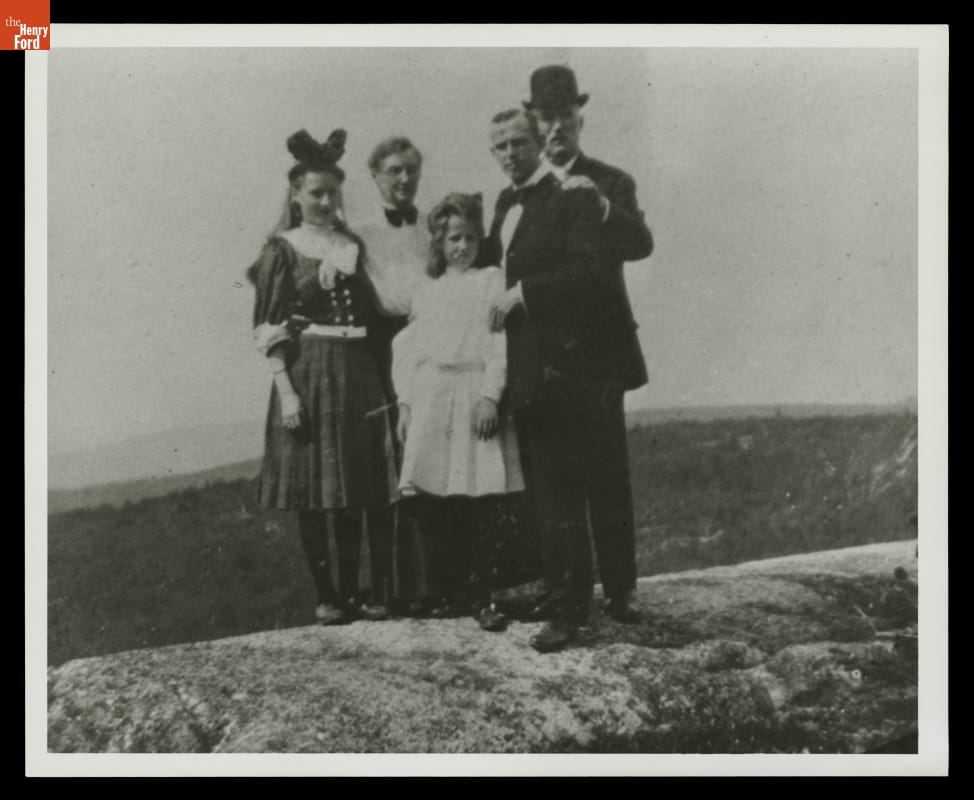

The earliest travel diary penned by Clara was for her first trip to Europe in 1912. She, Henry, and Edsel explored sites throughout Great Britain and France.

Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford aboard Ship on their European Trip, 1912. / THF117563

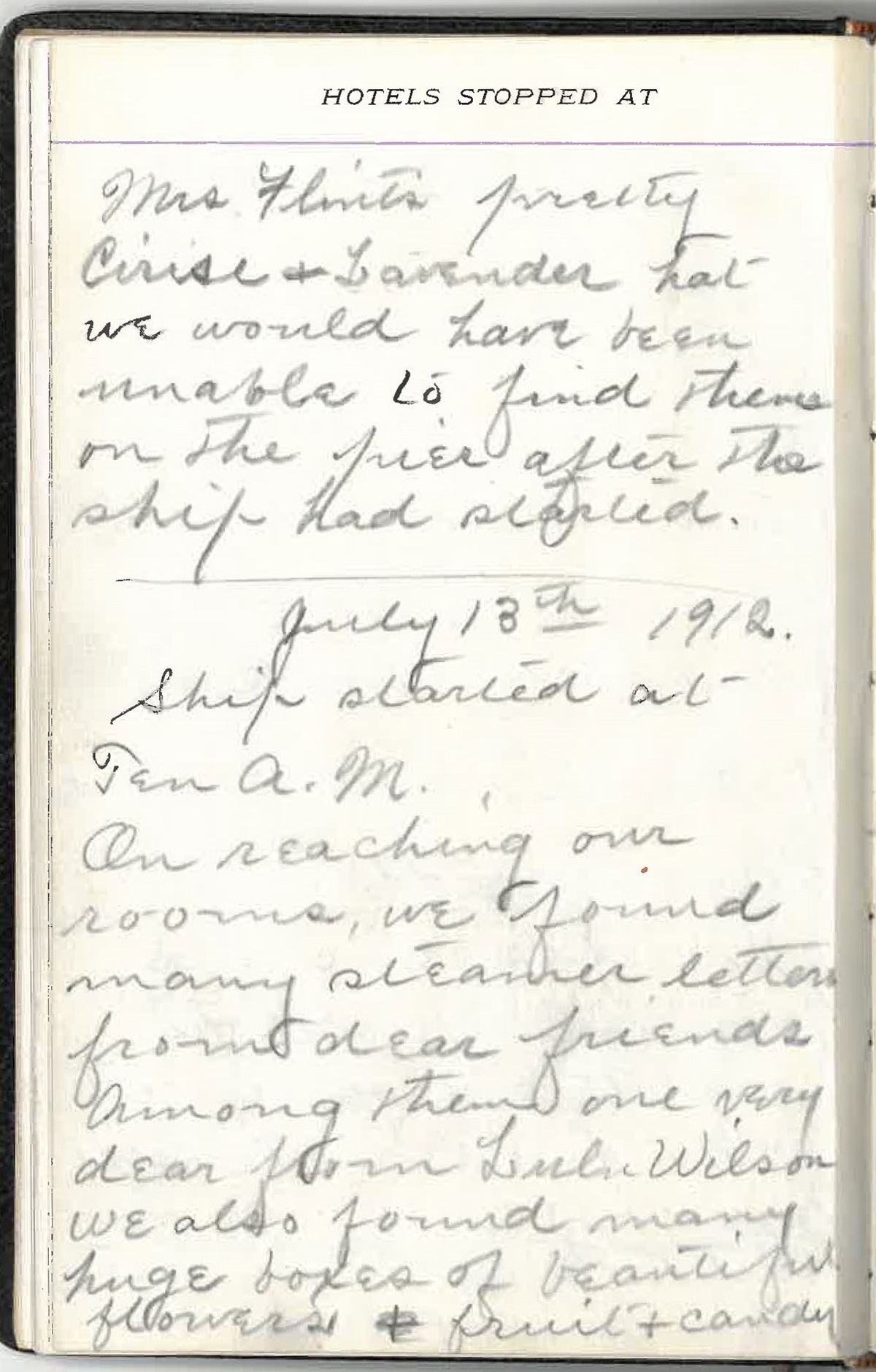

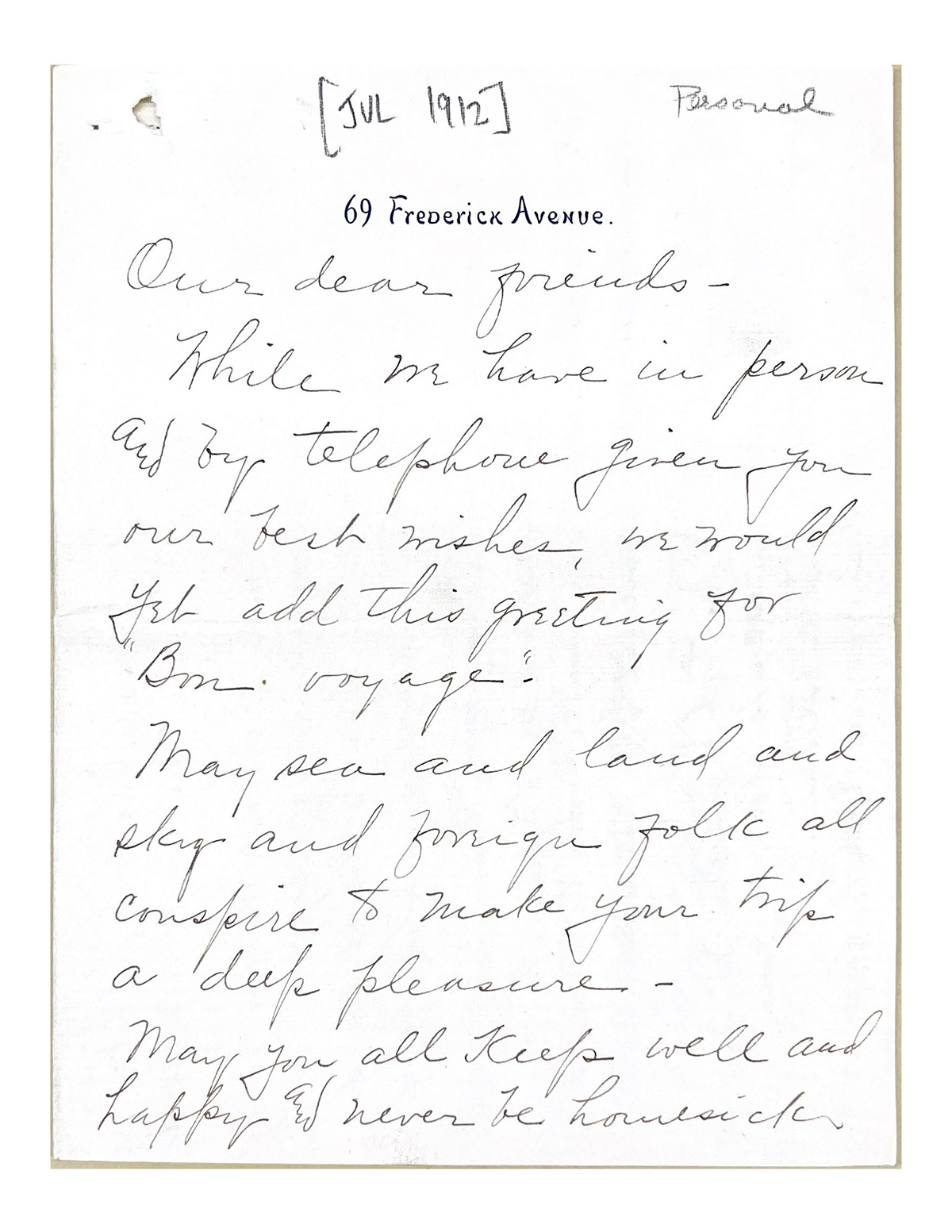

In one of the first entries, Clara documents the time the ship set sail and describes the warm welcome they received. Among flowers, fruits, and candy were several letters from friends wishing them a “Bon Voyage!” Clara references a letter from her close friend, Lulu Wilson, which we also hold in our collection. Connecting archival records like these illustrates a larger picture for historians and researchers.

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Letter to Clara Ford from her friend Lulu Wilson, July 1912. Accession 1, Box 66. / Image by Lauren Brady

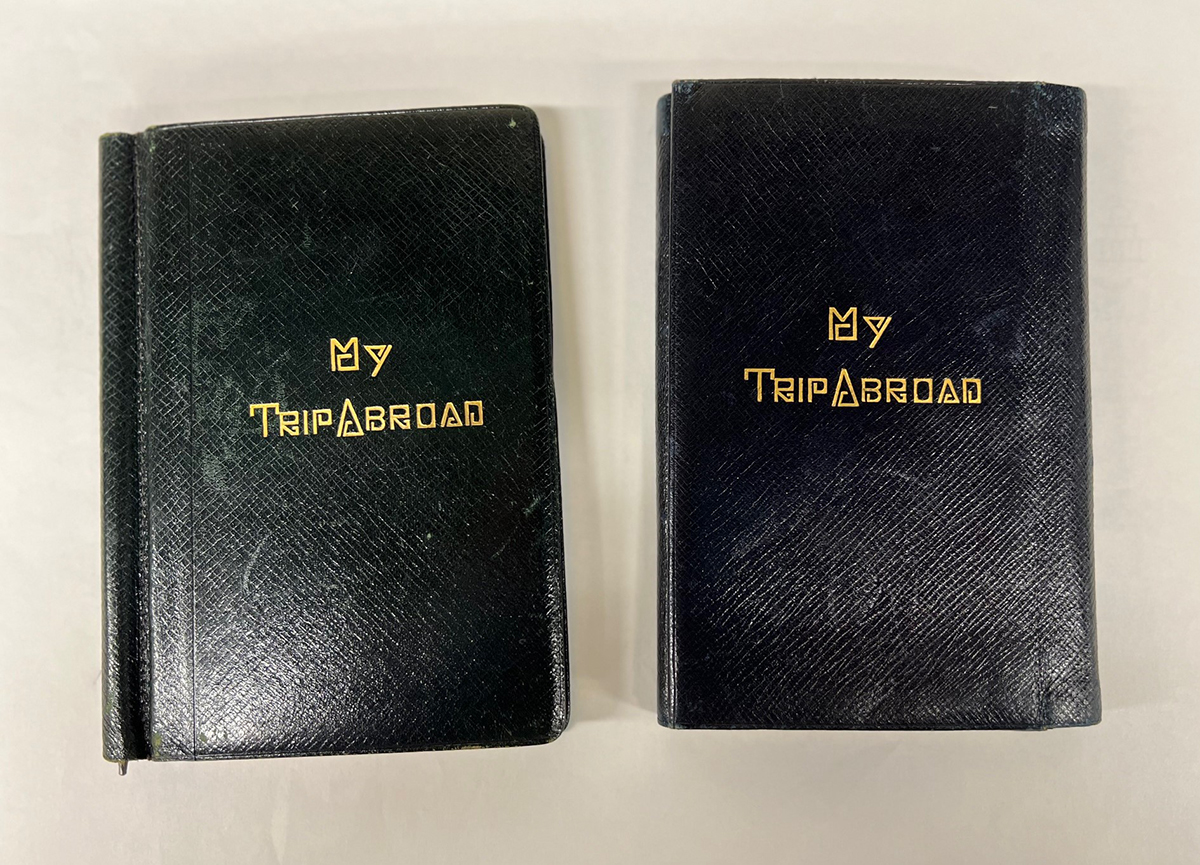

In addition to Clara's diary, we also have Edsel's diary from this trip in our collection.

Clara Ford's and Edsel Ford's Travel Diaries, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

During their travels, they visited Clara's ancestral home. There are parallel accounts of the visit in both diaries. It reads as a meaningful visit for Clara who also describes important genealogical details about her family history that may not have been recorded elsewhere in our archival collections.

Edsel Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

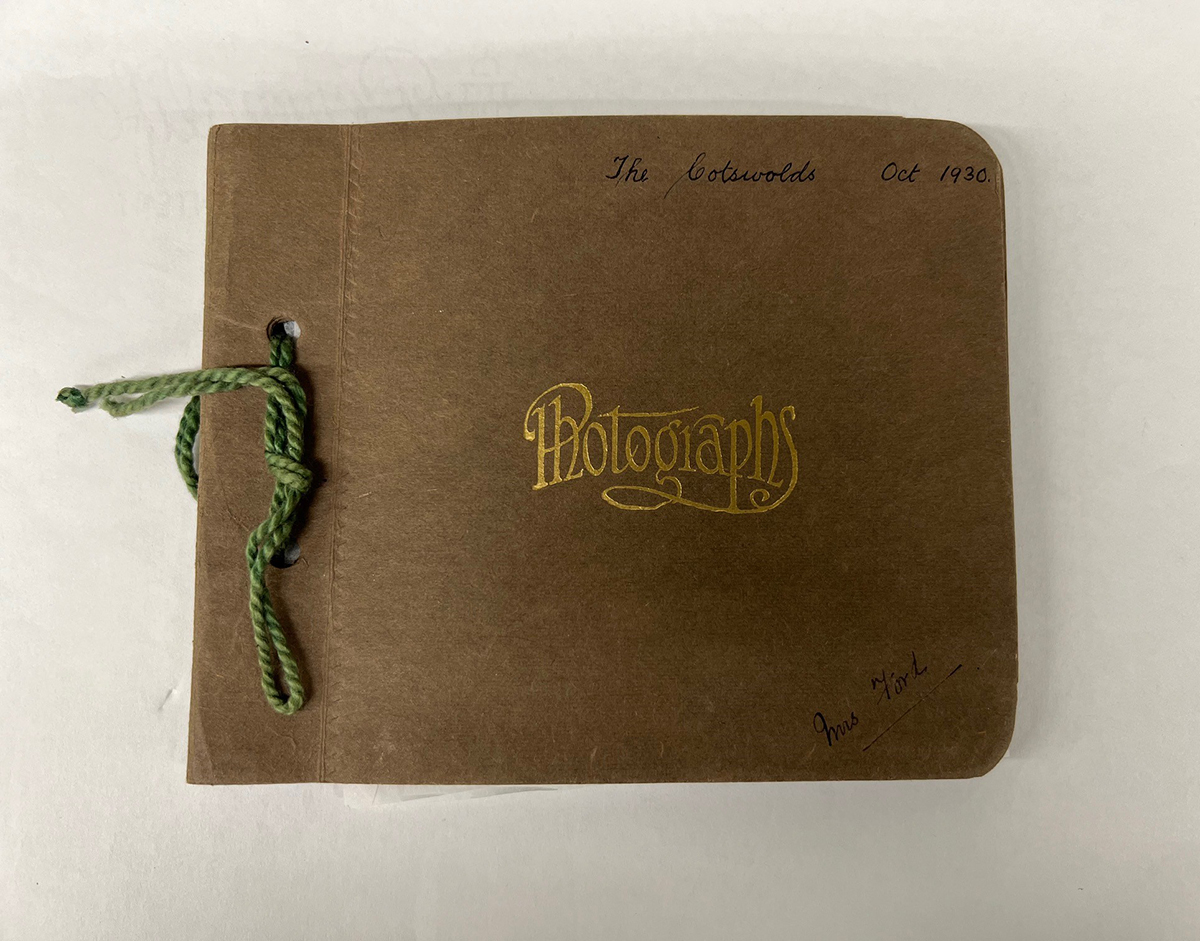

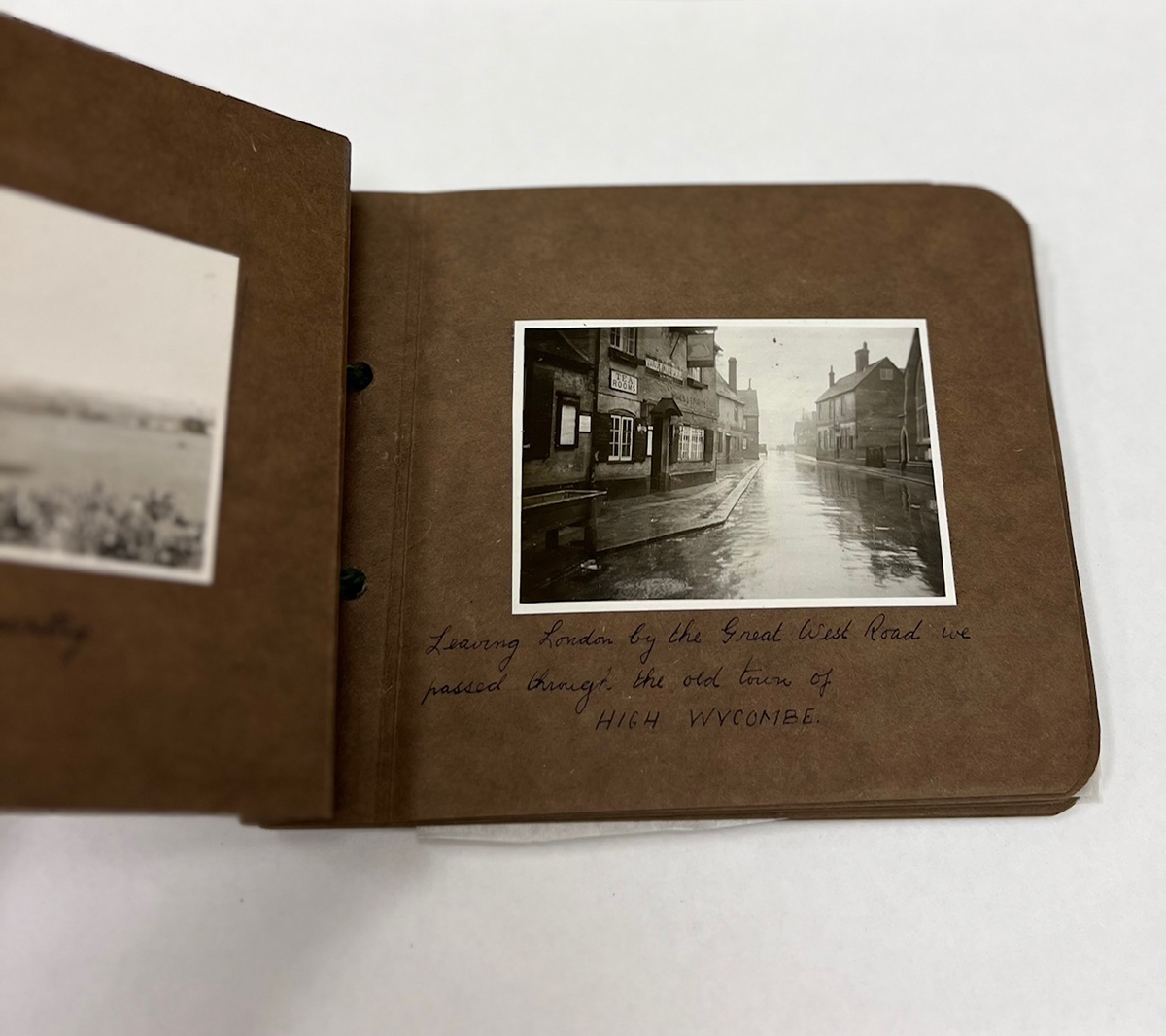

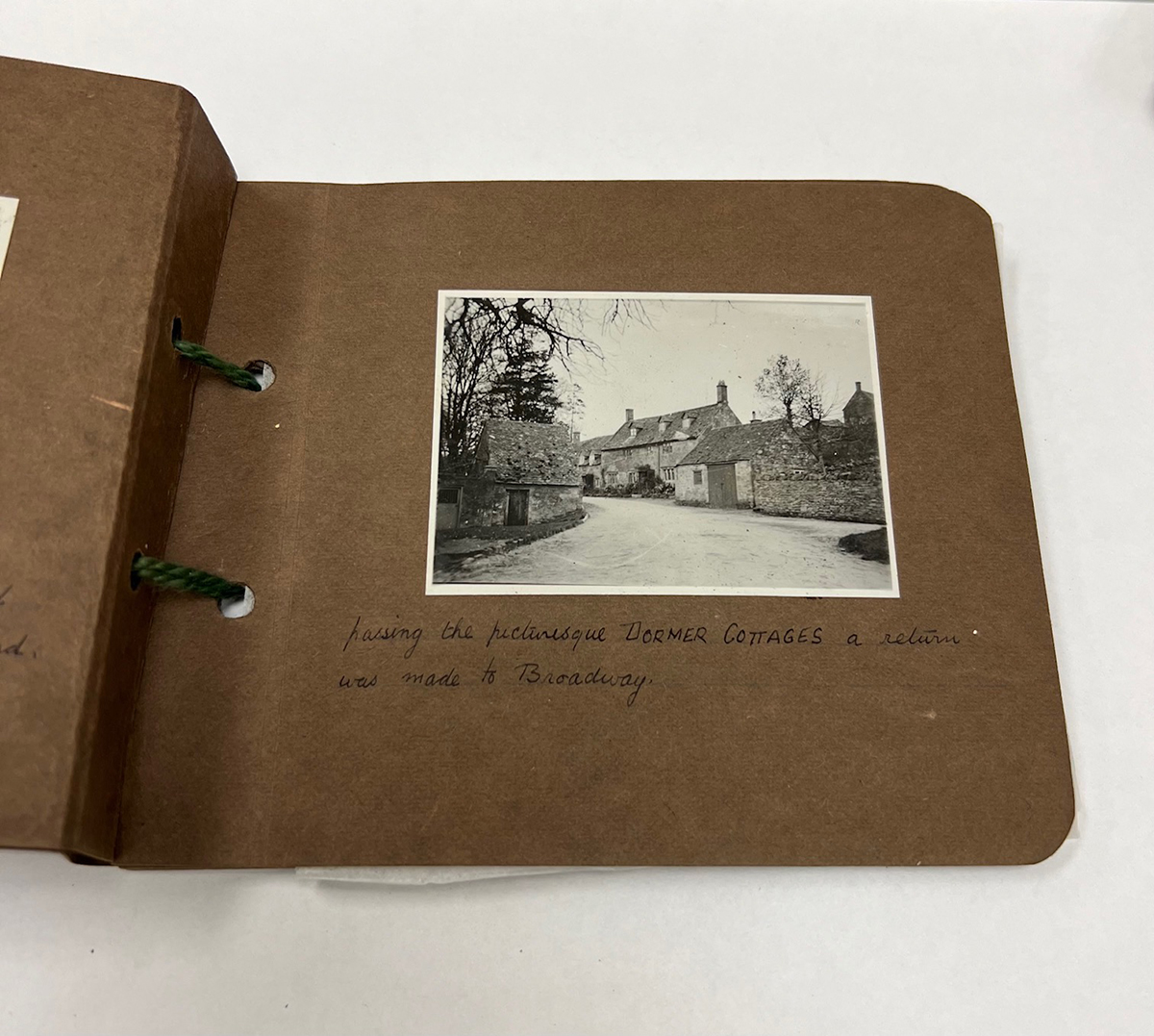

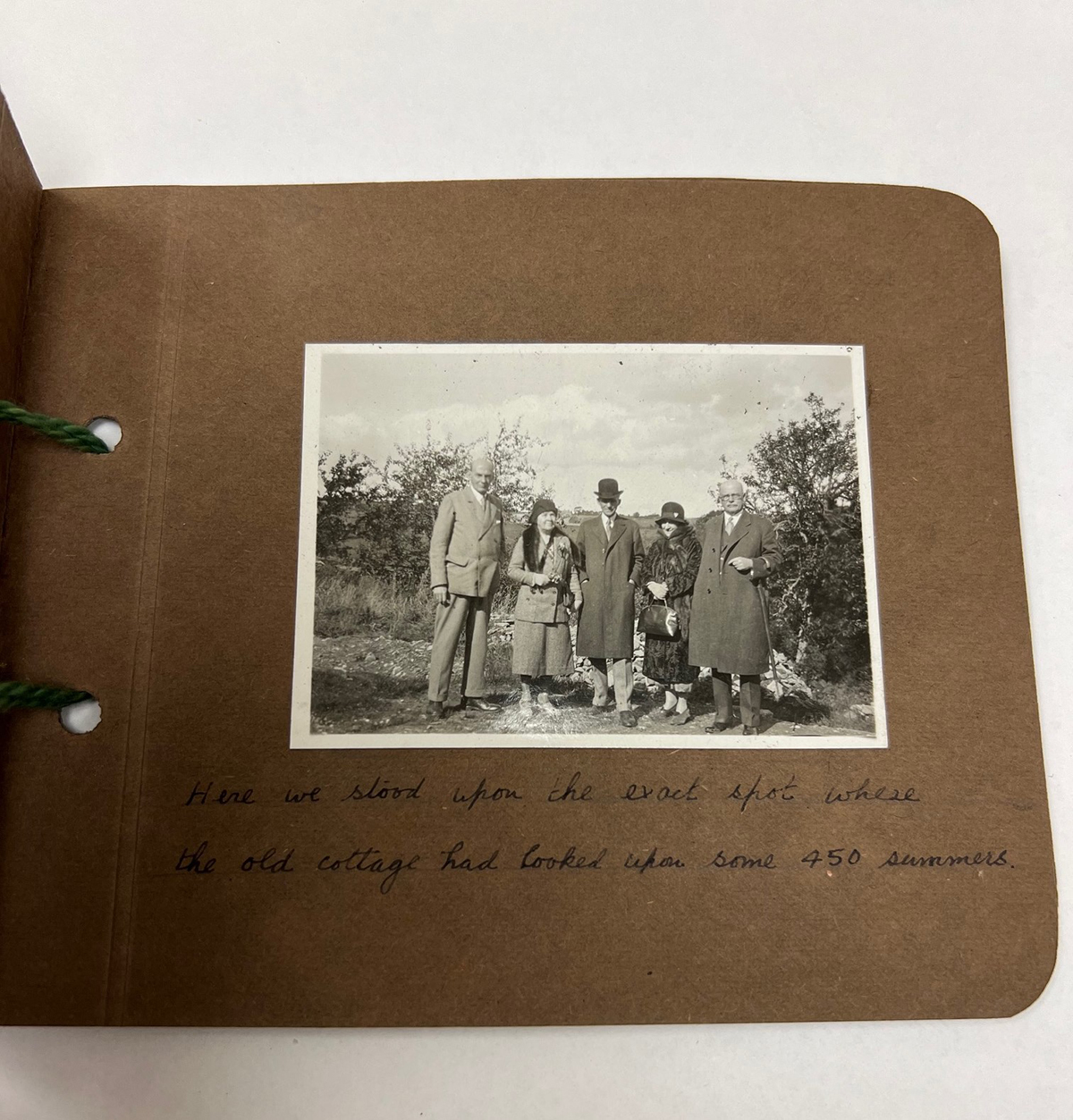

The Fords returned to Europe many times, including a trip in 1930 which Clara documented in a diary and a unique photo album. In her diary, Clara makes note of Henry's visit to Buckingham Palace before he departed for the Cotswold region of England where Cotswold Cottage had recently been acquired for Greenfield Village.

This visit received special commemoration in a photo diary with handwritten notes by Clara.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

The album includes several snapshots of their visit culminating with a group photo at the former site of Cotswold Cottage. Clara's notes read like a short story as she describes the photos and recounts details.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara's diary entries with descriptions of cities and historic sites she encountered are valuable to historians looking for written records of landscapes altered by wars and other major events. Her words help us understand Clara Ford as a historical figure, but they also help us understand a location as it stood at that moment in time.

We are grateful to have these valuable archival records, but it is fun to wonder how a modern Clara may have documented her travels. Perhaps a post like this...

If you have any questions or would like to learn more about our collections, please contact the Benson Ford Research Center at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Lauren Brady is a reference archivist at The Henry Ford.

Edsel Ford, Ford family, Henry Ford, Clara Ford, by Lauren Brady

Lincoln’s Century with Ford Motor Company

1928 Lincoln Four-Passenger Coupe Advertising Proof, "Every Lincoln Body is a Custom Creation of Some Master Body Builder" / THF113063

One hundred years ago this month, Henry Ford purchased the Lincoln Motor Company from Henry Leland. The Henry Ford joined in the centennial celebration on our website, where we published a new Popular Research Topic outlining key Lincoln assets from our collections; on Facebook and Twitter, where we shared social posts featuring artifacts from our collections; and on Instagram, where Reference Archivist Kathy Makas shared a Lincoln-related story. Kathy’s story was part of our History Outside the Box monthly series on Instagram, featuring interesting or noteworthy items from our archives.

If you missed the live version of our Instagram story, you can check it out below to learn how Edsel Ford, as president of Lincoln, brought a design eye to the company and how design at Lincoln evolved. You’ll also discover a few of the famous celebrities who owned Lincolns, take a look at some Lincoln publications, and more.

Continue Reading

Ford family, History Outside the Box, Ford Motor Company, Edsel Ford, design, cars, by Kathy Makas, by Ellice Engdahl

Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Rail Car and the Engineering Laboratory Offices

In my last blog post, I discussed how Sidney Houghton (1872–1950), a British interior designer and interior architect, met and befriended Henry Ford during World War I and, following the war, became part of the Fords’ inner circle.

The Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford holds significant correspondence, designs, and records relating to commissions between Houghton and Henry and Clara Ford. Probably the single document that details the variety of Ford commissions associated with Houghton is a brochure, more of a portfolio of projects, published by Houghton in the early 1930s, to promote his design firm.

Cover of Houghton brochure. / THF121214

From Houghton’s reference images, we can document many commissions that no longer survive, as well as provide background for some that are still do. This post centers on two projects, the Fair Lane rail car and Henry and Edsel Ford’s offices in the Ford Engineering Laboratory, which still exist. Fortunately, aspects of both still exist in The Henry Ford’s collection!

The Fair Lane Rail Car

The Fair Lane rail car. / THF80274

Edsel and Eleanor Ford, Henry and Clara Ford, and Mina and Thomas Edison pose on the car’s rear platform about 1923. / THF97966

Images of the Fair Lane rail car from Houghton brochure. / THF121225a

The Fair Lane rail car was built by the Pullman Rail Car Company in Pullman, Illinois, and delivered to Henry and Clara Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, in summer 1921. A detailed history and background on the rail car by Matt Anderson, The Henry Ford’s Curator of Transportation, can be found here.

Sidney Houghton was responsible for creating the interiors and furnishings for the car. Many sources state that he worked with Clara Ford on the designs. What is likely is that Clara Ford approved or disapproved of Houghton’s design work. This is especially evident in the public rooms of the rail car—what Houghton called the “dining saloon” and the “observation parlour.”

Dining saloon in 1921. / THF148009

The same view in 2021. / THF186285

Glassware storage. / THF186283

The dining room walls are paneled in dark walnut, with veneered elements of mahogany. The effect suggests a richly appointed room from which to view the passing scenery. The styles that Houghton employed, and Clara Ford approved, derived from a combination of eighteenth-century English classical styles, including the caned and oval-backed side chairs and the elegantly carved three-quarter relief columns around the walls. China and glassware were stored in built-in units fitted with slots or pegs to keep the objects from shifting during travel.

The observation saloon in 1921. / THF148015

The observation saloon in 1921. / THF148012

The observation saloon in 2021. / THF186264

Detail of the observation saloon. / THF186263

What Houghton called the “observation saloon” was where passengers would spend their days while traveling. It was fitted out with sets of upholstered armchairs below the windows and a slant front desk and bookcase against the inner wall. This was an extremely useful piece of furniture; while at the desk, you could read or write correspondence, and when done, store your letters in one of the many drawers in the desk. The upper case allowed plenty of room to store books and other reading materials. Dials above the door to the observation platform displayed the miles per hour, the time, and the outdoor temperature.

As you can see in the recent photographs, over time the painted woodwork in this room was stripped and refinished. Also, the wonderful slant front desk and original light fixtures have not survived. Fortunately, after the Fords sold the rail car in 1942, a subsequent owner lovingly restored the interior, including reproducing much of the furniture, before donating it to The Henry Ford.

The Ford Engineering Laboratory Offices

In the early 1920s, Henry Ford commissioned his favorite architect, Albert Kahn, to design what Ford called his Engineering Laboratory in Dearborn. Completed in 1923, this building came to be the heart of the Ford Motor Company enterprise. Both Henry and his son, Edsel, had offices in the building, and Henry commissioned Sidney Houghton to design identical furniture and woodwork for each. Both offices survive, as does most of the furniture, which is now in the collections of The Henry Ford. Of all of Houghton’s projects for the Fords, it is the best preserved.

Henry Ford’s office in 1923. / THF237704

Henry Ford’s office in 1923. / THF237702

Edsel Ford’s office (top) and Henry Ford’s office (bottom) from Houghton brochure. / THF121221a

In looking at the offices, one thing comes to mind: they were designed to impress. Like the rail car, they are paneled in rich walnut, with matching walnut furniture. Both have large conference tables; Henry’s is round, while Edsel’s is rectangular.

Conference table used in Edsel Ford’s office. / THF158754

The chairs and tables all feature heavy, turned, and curved legs, known as cabriole legs. They are also inlaid with woods with their grains carefully arranged to their fullest and most luxurious effect.

Desk chair. / THF158365

Armchair. / THF158349

Easy chair. / THF158367

Sofa. / THF158750

The style of this furniture is English Jacobean, deriving from forms used in the seventeenth century. The intent with this furniture was to show off wealth and good taste—as befit a person of Henry Ford’s status.

Console table. / THF158371

This console table, seen in the photograph behind Henry Ford’s desk, is inlaid with matched veneers along the drawer front and handles in the shapes of shells. The elaborately turned legs, which look like upside down trumpets, are characteristic of the Jacobean style in England. Combined with the cabriole legs on the chairs, Houghton has mixed and matched English furniture styles here in what decorative arts historians call an eclectic fashion.

Tall Case Clock, works by Waltham Clock Company. / THF158743

If the rest of the office furniture was meant to impress, the tall case clock takes it over the top. Henry Ford was known for his love of clocks and watches. This piece was undoubtedly something that he was proud to possess and show off to guests in his office.

We know from documents that Henry Ford rarely used his office. He preferred to be out in the field visiting with employees or, in later years, in Greenfield Village. Consequently, the furniture shows little signs of wear. Further, there are few photographs of Henry Ford in his office, other than those taken in 1923 when it was newly installed.

Henry Ford’s office in 1949. / THF149868

Taken two years after Henry Ford’s death in 1947, this image shows how he used the office.

Henry Ford by Edward Pennoyer, 1931. / THF174088

On the wall behind the desk is a painting by artist Edward Pennoyer, used as an illustration for a 1931 advertisement. Henry Ford undoubtedly liked the image of himself with the Quadricycle, his first automobile, and hung it behind his desk.

Photograph of Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, to Henry Ford’s right, surrounded by unknown figures, November 1941. / THF240734

Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, November 1941. / THF241506

Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, November 1941. / THF241508

Only three photographs survive of Henry Ford in his office. All date to November 1941, when the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, visited Henry Ford and toured the Rouge Factory. Guests to the Engineering Laboratory were almost always photographed outside the building or in the adjacent Henry Ford Museum or Greenfield Village.

The third photograph above shows another work of art in the office. The landscape shows Henry Ford’s Wayside Inn, in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, purchased in 1923. This, of course, was a place near and dear to Henry Ford, and helped him to realize his goal of creating Greenfield Village.

As we can see, Sidney Houghton was close to Henry and Clara Ford, designing Henry’s office and the Fair Lane rail car intimate environment, used on a very regular basis. In the next blog post, I will look at the most intimate of the Fords’ interiors—their Fair Lane Estate, onto which Houghton put his own influence during the first half of the 1920s.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner

Fully Furnished - Designs for Aging: New Takes on Old Forms

- The Enigmatic Sidney Houghton, Designer to Henry and Clara Ford

decorative arts, Sidney Houghton, railroads, Michigan, Henry Ford, furnishings, Ford Motor Company, Fair Lane railcar, Edsel Ford, design, Dearborn, by Charles Sable

Edsel Ford: A Legacy of Philanthropy

Edsel Ford and Eleanor Ford with Their Children, Henry, Benson, Josephine and William, at Gaukler Pointe, circa 1938. THF99953

Edsel Bryant Ford was born in Detroit to Henry and Clara Ford on November 6, 1893. As their only son, Edsel seemed destined for a career at Ford Motor Company. He began working for Ford after his high school graduation in 1912 and rose through the ranks to President by age 26. Edsel spent 31 years with the organization, but his life was tragically cut short when he passed away from cancer on May 26, 1943 at just 49 years old.

While his career at Ford was extremely important to Edsel, his wife, Eleanor, and their four children – Henry, Benson, Josephine, and William – were most precious to him. During his limited leisure time he enjoyed painting and collecting art, spending time outdoors, and relaxing with his family at their home in Grosse Pointe Shores. Edsel was also a prolific philanthropist, and, 75 years after his death, exploring his extensive philanthropy is a fitting way to honor his life and legacy of good will.

Edsel Ford at Yale-Harvard Boat Races, New London, Connecticut, 1939. THF94864

Edsel Ford is perhaps best-known for his involvement with the arts. Millions have viewed the Edsel Ford-sponsored and funded Detroit Industry murals by Diego Rivera at the Detroit Institute of Arts or visited the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, of which Edsel was a trustee from 1935 until 1943. Eleanor became a MoMA trustee in 1948, and the Ford Foundation (which was founded by Edsel in 1936) donated one million dollars to the museum in Edsel’s memory in 1963. He also attended many concerts at the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and was a generous patron of the Detroit Symphony Society.

Oil Portrait of Edsel Ford by Diego Rivera, 1932. THF116599

Edsel donated regularly to the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts – which is now the College for Creative Studies – and attended painting classes in the late 1920s. By 1933 the Society had altered its original mission of keeping handmade craftmanship alive in an increasingly industrialized world and was one of the first art institutions to acknowledge the automobile as an art form. In the book “Making the Modern: Industry, Art, and Design,” author Terry Smith describes this new relationship between art and industry in relation to the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts:

“Like the shift from the Model T, like the basic move within design itself, this group negotiated a passage from applying ‘art’ to industrial products (decorative devices, elaborate ornamentation) toward seeing ‘art’ in them (their ‘natural simplicity’, ‘precise’ beauty, their matching of ‘form’ and ‘function’). This implied the possibility of designing art into them, of controlling the matching so skillfully that the result would be ‘a work of art’.”

This emphasis on the intersection of art and design was also reflected in Edsel’s work at Ford. He was instrumental in moving the company beyond the Model T into a new automotive era in which both form and function were equally incorporated into the design process.

Edsel Ford as a Child, Fishing, Lake Orion, Michigan, 1899. THF99836

Edsel Ford, Fishing, 1915. THF130392

Another of Edsel’s lifelong passions was nature. He engaged in many outdoor hobbies, including fishing, golfing, camping, and sailing, and these interests are reflected in his philanthropy. He supported our national parks – “America’s best idea” – through his contributions to Shenandoah National Park in Virginia and the nonprofit National Parks Association (now the National Parks Conservation Association). In 1931 Congress authorized the creation of Isle Royale National Park in Michigan and Edsel served on the Isle Royale National Park Commission, which managed land acquisition. After the commission acquired most of Isle Royale the land was transferred back to the National Park Service to create the park.

State of Michigan Certificate Reappointing Edsel Ford to the Isle Royale National Park Commission, June 22, 1939. THF256194

Edsel unsurprisingly gave to Henry Ford Hospital, which was founded by his father in Detroit in 1915, but he also donated to many healthcare organizations across the United States and around the world. He contributed to the building fund of King George Hospital in London five years after King George’s son Prince Edward visited Ford Motor Company to learn more about methods of large-scale manufacturing.

Edsel Ford, Edward Albert the Prince of Wales, and Henry Ford at Fair Lane, Dearborn, Michigan, 1924. THF116352

He gave nearly every year to the Frontier Nursing Service, which provided nurse midwifery services to women in rural Kentucky and was one of his mother’s favorite charities. In 1939 he sent the nurses a used Ford station wagon, which they christened “Henrietta," and a second new station wagon in 1941. The American Red Cross, the American Foundation for the Blind, The Seeing Eye, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now March of Dimes), and many other health organizations also received generous contributions from Edsel.

Fundraising Letter from Mary Breckinridge, Frontier Nursing Service, to Edsel Ford, June 3, 1940. THF130768

Vanda Summers of the Frontier Nursing Service, with Automobile Donated by Edsel Ford, May 1940. THF130772

This list represents a miniscule fraction of Edsel’s charitable career, and the impact of his philanthropy is still felt today through the work of the hundreds of organizations that benefitted from his time and contributions. While remembering Edsel’s career and philanthropy in his 1956 Reminiscences for Ford Motor Company his longtime secretary A.A. Backus stated, “Yes, Mr. Edsel Ford was a swell individual and in my twenty-seven years with the Ford Motor Company I never heard anyone say anything different.”

Edsel Ford on the Beach with Henry Ford II and Benson Ford, 1921. THF95355

Meredith Pollock was formerly Special Assistant to the Vice President at The Henry Ford.

healthcare, Michigan, Detroit, nature, 20th century, 1940s, 1930s, 1920s, philanthropy, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Meredith Pollock, art

When the 29 millionth Ford came off the assembly line in 1941 there was no doubt who the owner would be - a group of American Red Cross volunteers were waiting for the keys as the car rolled into sight. The donation of the vehicle was just a small part of the role Ford Motor Company undertook with the American Red Cross during World War II. Both Henry and Edsel Ford not only made large monetary donations and sponsored blood drives and fundraisers at Ford plants, but they also gave space, teachers, supplies, and vehicles to the Detroit Chapter of the American Red Cross Motor Corp.

Edsel Ford Presents the 29-Millionth Ford to the Red Cross, April 29, 1941.

THF270135

The Motor Corp., which was started during WWI in 1918, was a segment of the American Red Cross made up of women civilian volunteers. They were responsible for transporting wounded and sick soldiers to various hospitals; conveying donated blood, supplies, and food to airstrips for over overseas transport, and also driving hospital volunteers, Red Cross personnel, and visiting military family members to hospitals, recovery centers, and funeral homes. The Motor Corp. served the Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Blood Blank, various social agencies, and the USO. These women provided their own vehicles, gas, time, and tools and also had to purchase their uniform, and insignias for their cars.

Not only were volunteers in the Motor Corp. required to provide their own vehicles but they had to perform their own maintenance as well. Many of the volunteers had never been called on to service a car, and with wartime restrictions on materials, auto repair was even more difficult. Ford Motor Company stepped in to offer mechanics training courses to Detroit Chapter Motor Corp. volunteers. The Company provided trained mechanics, free of charge, to teach groups of volunteers the basics of car maintenance. According to the National Red Cross Motor Corp. Volunteer Special Services Manual, the mechanics course should cover how to “change a tire, apply chains, replace light bulbs, check gas flow at carburetor back through fuel pump to tank, check battery, check loose electrical connections, check spark plugs, and check electrical current at generator and distributor.” Volunteers didn’t have it easy, instructor were encouraged to “disconnect various electrical wires and parts of the gas pipe system” so members could analyze what was wrong and fix it. Ford opened up rooms in Highland Park for many of the training classes in 1941, and dealerships all over Detroit were made available for evening classes. The classwork included both informational lecture instruction and hands-on training on automobiles. The company also provided trucks for driving tests, and other equipment needed by the local Corp.

Red Cross Women's Motor Corps Workers Learn about Auto Maintenance, March 1941. THF269991

The first vehicle Ford donated to the Red Cross during WWII was an important vehicle to the company. The car was a Super Deluxe Ford Station Wagon, but this was no ordinary car, it was the 29 millionth Ford car produced in their 38 year history. The car sported the Motor Corp. insignia on the front door and carried a ceremonial license plate of "29,000,000." The morning of April 29, 1941, found Edsel Ford with a group of volunteers from the Motor Corp. of the Detroit chapter of the American Red Cross. A dozen or so representatives of the Motor Corp gathered with Ford as the car rolled to the end of the line. Edsel handed off the keys to the Captain of the Detroit Motor Corp, Barbara Rumney, who took the wheel as Edsel joined her for a ride in the new car.

Edsel Ford Presents the 29-Millionth Ford to the Red Cross Women's Motor Corps, April 29, 1941. THF270143

By 1942, the Detroit Chapter of the Motor Corp. had over 1,300 trained volunteers, and after Ford’s donation of the 29 millionth car, had added 22 other pieces of equipment to broaden their reach and impact. Barbara Rumney wrote Ford stating “We realize that if it had not been for your generous response, we could not have attempted many of the things that we are doing to serve our country in its crisis.” Over the course of World War II 45,000 women volunteered for the American Red Cross Motor Corp. driving 41 million miles to support the war effort.

Red Cross Women's Motor Corps Worker Learning about Auto Maintenance, November 1941. THF270091

Kathy Makas is a Reference Archivist for the Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford. There’s plenty more in our collections on Ford Motor Company and the war effort. Visit the Benson Ford Research Center Monday-Friday from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm. Set up an appointment in the reading room or AskUs a question.

women's history, education, Michigan, Detroit, Edsel Ford, cars, World War II, World War I, by Kathy Makas, philanthropy, healthcare, Ford Motor Company

“A Very Practical and Purposeful Program”

Last summer, our 2016 Edsel B. Ford Design History Fellow, Meredith Pollock, investigated materials in our collection related to Edsel and Eleanor Ford’s philanthropy, including a thread concerning the NAACP. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded February 12, 1909, on the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. The goal at the time, as the NAACP’s website notes, was to “secure for all people the rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, which promised an end to slavery, the equal protection of the law and universal adult male suffrage, respectively.”

Judge Ira W. Jayne of the third judicial circuit of Michigan reached out to Eleanor Ford for a donation to the Detroit branch of the NAACP in 1922. In a letter we’ve just digitized, Jayne calls the organization “the most intelligent and wholesome effort for and in behalf of the betterment of race conditions in the country today” and notes that his “knowledge of [Eleanor’s] interest in fair play for the under man has prompted this letter.” Jayne did succeed in his goal—a reply two weeks later from Edsel Ford calls the NAACP’s goals “commendable” and includes a donation for $100.

Visit our Digital Collections to view more artifacts related to the NAACP.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

digital collections, Michigan, Detroit, African American history, Edsel Ford, philanthropy, by Ellice Engdahl

This summer, The Henry Ford hosted Meredith Pollock as our 2016 Edsel B. Ford Design History Fellow. Her work here investigated the materials in our collections related to Edsel Ford’s philanthropy, and turned up a great deal of information on the kinds of charities to which Edsel donated.

One thing that caught our eye, particularly in light of this year’s National Park Service centennial, is Edsel’s ongoing relationship with America’s national parks. We’ve just digitized a number of letters, photographs, and other artifacts that help explain how Edsel supported the park system, including this certificate reappointing Edsel to the Isle Royale National Park Commission.

Explore further by visiting our Digital Collections to see more material on Edsel and the national parks, or read parts one, two, and three of a blog series outlining Edsel’s associations with some of the parks.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

nature, 1940s, 1930s, 1920s, philanthropy, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl

Edsel Ford and the National Park Service: Part 3

Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah

During his 1927 summer retreat to Seal Harbor, Maine, Edsel Ford spent time having discussions with his neighbor John D. Rockefeller Jr. on the importance of the national parks to the American public. One year before, in 1926, Arno B. Cammerer, then Associate Director of the National Park Service, had initiated his career-defining project of establishing numerous national parks in the Eastern United States when Congress authorized the National Park Service's Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah park proposals. At the time, Lafayette National Park, now Acadia National Park, was the only park east of the Mississippi and despite growing travel to western parks, Cammerer was concerned that only a very small portion of those living east of the Mississippi would ever have the time or the money to visit them.

Realizing that there were millions of people in "the congested areas of the East who never will see the western parks," Cammerer helped the National Park Service establish an unofficial commission composed of park experts to ascertain whether there were lands in the East that would meet the National Park Service standards. The commission, partly funded by John D. Rockefeller Jr., focused on the Southern Appalachian Mountain region, concluding that the lands that would eventually make up the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and Shenandoah National Park should be set aside for the American public. West of the Mississippi, parks could be easily carved out of large public land holdings. In the East, however, a majority of land was privately held which meant that although these Eastern park projects had been authorized in 1926, they could not be fully established until a majority of the land in the planned areas had been bought by the state and deeded to the U.S. government. Cammerer soon realized that land purchasing financed by state funding and small public donations would not be enough to make the Eastern park project a reality.

Several popular tourist stops in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park appear on this pennant. THF238700

To remedy the funding problem, Cammerer again turned to one of the wealthiest men in America and the largest benefactor of the East's first national park, John D. Rockefeller Jr. After helping to fund the commission, Rockefeller Jr. had previously mentioned to Cammerer that he was very much interested in continuing his support of the Eastern national parks project. This prompted Cammerer to write him in the beginning of August 1927 at Rockefeller Jr.'s Seal Harbor home, "The Eyrie." Cammerer's letter explained that while he had intended for public donations to be split fifty-fifty between the Great Smoky Mountain project and the Shenandoah project, the Great Smoky Mountains project was further along and more time-sensitive, as some of the lands set aside for the project were being clear-cut of their primitive forests before being sold. Securing the land for the Great Smoky Mountains project had become the utmost priority.

Expressing that the potential Great Smoky Mountains park “appeals to him more than any national park," Cammerer also enclosed photographs in his letter that he thought illustrated the “wonderful scenic character of the country proposed for inclusion in the park.” In Seal Harbor, Rockefeller Jr. brought the issue to the attention of his philanthropic partner, neighbor, and avid photographer, Edsel Ford. Sparking an interest with Edsel to contribute to the project, Rockefeller Jr. relayed to Cammerer that Edsel would possibly be willing to donate, spurring Cammerer to contact Edsel in the beginning of September 1927. In his letter to Edsel, Cammerer added, “I am taking the liberty to enclose a considerable number of photographs showing the superb scenic qualities of the region, which Mr. Rockefeller also has seen, which I believe Mrs. Ford and you will enjoy looking over."

Over the course of September 1927, Cammerer kept sending Edsel information on the Eastern parks project, reiterating that the Great Smoky Mountains park in Tennessee and North Carolina continued to be the top priority. He also explained that the land required for the Shenandoah park consisted of mostly Virginian farmland and would take much longer to acquire. Luckily, the proposed Shenandoah park would include part of the Shenandoah Valley, which happened to be the birthplace of Harry F. Byrd, the Governor of Virginia at the time. The son of a wealthy apple grower from the Shenandoah Valley, Governor Byrd supported the idea of establishing a national park in his state and worked to make it a reality. Governor Byrd's brother, Admiral Richard E. Byrd, also happened to be a world-renowned explorer, pioneering aviator, and friend of Edsel Ford. Edsel would be responsible for helping to fund Richard Byrd's expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic, including convincing Rockefeller Jr. to aid in funding the latter.

Running the entire length of Shenandoah National Park, Skyline Drive offers 105 miles of scenic views along the Shenandoah Blue Ridge. This souvenir pennant depicts the 670-foot-long Mary's Rock Tunnel -- the only tunnel on the drive. THF239213

Rockefeller Jr. wrote Edsel from Seal Harbor at the end of September looking for a decision, noting that the Great Smoky Mountains project still needed money to purchase land and that Edsel had “expressed an interest in this project" when Rockefeller Jr. saw him in Seal Harbor a few weeks ago. Rockefeller sent him a copy of his pledge hoping that his letter of gift might be suggestive to the amount of money Edsel would donate. Edsel responded the same day saying, "I feel like I would like to help in this great undertaking," but financial obligations like a new home and other philanthropic efforts required him to donate "less than I would like to do if the circumstances were otherwise." Nonetheless, Edsel was "very glad to contribute $50,000 dollars" to the Great Smoky Mountains project and also would "be very glad to consider increasing" the pledge the next year if additional funds were needed.

In this letter from Edsel Ford to Rockefeller Jr., Edsel mentions his various other philanthropic activities, including an explanation on how important Richard Byrd's South Pole expedition will be. Due to Edsel's convincing justification above, Rockefeller Jr. would later help fund Byrd's expedition. THF255218

On October 6th, referring to their new partnership in funding the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Rockefeller Jr. wrote Edsel saying, “It is particularly gratifying to me that we are to be associated together with it." By November of 1927, Edsel had contacted Cammerer to declare that he intended to subscribe $50,000 to help establish the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which Cammerer graciously accepted. In February 1928 though, the Great Smoky Mountains project hit delays. Lagging fundraising meant that the lands designated for the park, which had yet to be acquired, were still under constant threat of being logged and needed to be procured immediately. The only public pledges to the park had been the ones made by Edsel and Rockefeller Jr. For the park to go forward, five million dollars would need to be raised in order to match the five million dollars in state funds already set aside to buy land for the park. With Edsel's pledge of $50,000 and Rockefeller Jr.'s pledge of $1,000,000, they had fallen well short of that goal.

Edsel Ford's signed letter to Arno B. Cammerer, stating that he is interested in contributing to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park project that Rockefeller Jr. had brought to his attention. THF255210

With time being of the essence, Rockefeller Jr. wrote Edsel with his proposed solution to the problem. The trustees of the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, a fund established by Rockefeller Jr.'s father in memory of his mother and headed by Rockefeller Jr., decided that an enterprise of this kind would have made a "very strong appeal" to Mrs. Rockefeller. The foundation would cover the entire five million dollars needed to match the state funds, helping to acquire all of the land needed to establish the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. With the total cost covered for the first park, Rockefeller Jr. suggested that Edsel transfer his donation over to the Shenandoah project, to which Edsel obliged.

While Edsel admitted that he had not taken a deeper look into the Shenandoah National Park project, he did accompany his family on a 1921 camping trip to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Maryland, a location less than hundred miles north of Shenandoah and geographically similar. Possible memories from this trip could have also played a role in Edsel's decision to donate to Shenandoah. THF255214

On February 28th, 1928, Edsel withdrew his pledge to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and promptly informed Cammerer that he would be transferring the same pledge over to the Shenandoah National Park fund. Rockefeller Jr. sent a letter thanking Edsel for his understanding and the transfer, ending the note with, “Looking forward to the reunion of our summer colony at Seal Harbor.” Cammerer also sent a letter thanking Edsel for his cooperation, noting, "There is nothing finer available in the East than these two areas selected for national park establishment and this is the psychological time, as the history of our country goes, to still procure these outstanding scenic beauty spots for the millions who will not have a chance to see the western wonderlands reserved in the national park system." Rockefeller Jr. would also contribute to the Shenandoah National Park fund as well.

This letter illustrates the pivotal role that Seal Harbor, Maine played in the friendship of Rockefeller Jr. and Edsel Ford. THF255212

In 1932, the state of Virginia began to collect the pledges that had been made to the Shenandoah National Park fund. Edsel reaffirmed his interest in this philanthropic endeavor with a letter to the Governor of Virginia saying, "It has been a great pleasure to contribute" to the fund. By 1935, Shenandoah had officially been established as a national park and, in 1936, they held a dedication ceremony to which Edsel was invited. Unfortunately, Edsel was leaving for Europe soon, which he explained to Cammerer, but his good friend Rockefeller Jr. was able to send a transcript of the dedication speech given by Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Part of the speech thanked Edsel for his contribution.

A page from Harold L. Ickes' Shenandoah National Park dedication speech. Named Secretary of the Interior by Franklin D. Roosevelt, Ickes held the position for thirteen years from 1933 to 1946. Known for being brutally honest, tough, and sharp-tongued, Ickes worked with Arno B. Cammerer to dramatically increase national park land even though the two constantly quarreled. THF255228

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

North Carolina, Virginia, philanthropy, nature, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Ryan Jelso, 20th century, 1930s, 1920s

Edsel Ford and the National Park Service: Part 2

Part 2: Mount Desert Island, Maine

Located off the coast of Maine, Mount Desert Island is one of the largest islands in the United States and home to Acadia National Park. Long known for its rocky coast, mountainous terrain, and dense wilderness, Mount Desert Island was popularized in the mid-19th century by the Hudson River School. The painters from this art movement focused on scenic landscape paintings, creating works of art that inspired many prominent citizens from the East Coast to build their summer homes on the island. By the late 19th century a resort tradition that became locally known as "rusticating" had taken root on Mount Desert. Wealthy East Coast families known as "rusticators" would spend their summers relaxing in their island mansions, taking in the scenery, and socializing with other prosperous families doing the same. In the early 20th century, the "rusticators" on Mount Desert Island also began to include affluent Detroit families as well.

Eleanor Lowthian Clay, Edsel Ford's future wife, was accustomed to affluence and spent her summers vacationing on Mount Desert Island as a child. Eleanor's wealthy uncle, Joseph Lowthian Hudson, was successful in the Detroit department store scene. As patriarch of the family, the childless J.L. Hudson cared for his other family members and allowed Eleanor's family, as well as some of his other nieces and nephews, to live with him. Hudson employed most of them in his business and groomed his four Webber nephews, Eleanor's cousins, to take over the family trade. Their sister, Louise Webber, married Roscoe B. Jackson, a business partner of J.L. Hudson. In 1909, Jackson helped formed the Hudson Motor Car Company with backing from Hudson. Jackson had found early success with the Hudson Motor Car Company and after inheriting the department store company, the Webber brothers were able to continue its success as well. The wealth and status that these families enjoyed allowed them to later choose Mount Desert Island as the location for their summer retreats and influenced Edsel to do the same.

Eleanor, right, and her sister Josephine, left, vacationing in Maine with their family. THF130536

The wealth of J.L. Hudson had helped establish Eleanor's cousins and acquaint Eleanor with the son of another wealthy Detroiter in Edsel Ford. While Edsel courted Eleanor, her sister Josephine was simultaneously being courted by up-and-coming lawyer Ernest Kanzler. Edsel became close friends with Kanzler, his future brother-in-law, who eventually was hired by Henry Ford to help manage the Fordson tractor company. By the early 1920's, Edsel and Eleanor along with the Kanzlers, Webbers and Jacksons were all vacationing on Mount Desert Island. Edsel began his Mount Desert residency by renting summer homes there, occasionally inviting his parents to vacation with him. During the late summer or early fall of 1922, Edsel purchased property in the area known as Seal Harbor. Sitting 350 feet above sea level on what is known as Ox Hill, Edsel's property had a panoramic view of the surrounding sea and sky. Also within walking distance of Acadia, then Lafayette National Park, Edsel soon found that his property adjoined the property of the neighborhood national park's biggest benefactor, John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Edsel with his sons Henry II and Benson spending time at the beach in Seal Harbor. THF95355

Rockefeller Jr. first visited Mount Desert Island in 1908 and immediately became enamored with the area. He built a large estate in Seal Harbor and by the time he became neighbors with Edsel in 1922, Rockefeller Jr. had already used his wealth to donate large tracts of land to his local national park. During this time he was also in the process of building a network of carriage roads that allowed the beautiful vistas of Acadia to be accessed by the public. Preferring the quiet serenity of horse-drawn carriages over the noisy automobiles, Rockefeller Jr. worked personally with the engineers to ensure that the carriage roads captured the tranquil scenery the park had to offer. The beautiful landscapes of the area would become the topic that Rockefeller Jr. used to initiate his friendship with Edsel Ford.

Panoramic view of Seal Harbor located on Mount Desert Island, Maine. THF255236

Initially writing in December of 1922, Rockefeller Jr. didn't hide his feelings when congratulating Edsel on the purchase of his Seal Harbor property. He had visited Edsel's property at the top of Ox Hill during sunset one night and stated in his letter, "I do not know when I have seen a more magnificent and stunning view than that which met my eye on every side. You have certainly made no mistake in selecting a site for your home.” He concluded the letter by expressing how happy he and his family were at the thought of having Edsel as a permanent summer neighbor. In Edsel's gracious response to Rockefeller Jr., he mentioned that he would be using architect Duncan Candler to design his Seal Harbor home. Candler had previously designed the neighboring Rockefeller home, as well as other note-worthy properties on the island.

John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s initial letter to Edsel congratulating him on the purchase of Edsel's Seal Harbor property. This letter lead to a life-long friendship that would be fueled by the spirit of philanthropy. THF255332

Christened with the name "Skylands" due to the unbroken views of the Maine horizon line that the property provided, Edsel's summer retreat was built between 1923 and 1925. In 1924, familiar with his new summer neighbor's philanthropic efforts and swayed by his past experiences, Edsel began donating yearly to the National Parks Association, known today as the National Parks Conservation Association. Created by industrialist Stephen Mather in 1919, the organization's mission was to protect the fledgling National Park Service, of which Mather was the director. For eight years Edsel would donate $500 annually to the National Parks Association, until the Depression years of 1932 and 1933 when other business and philanthropic demands restrained his monetary donations.

By the time Edsel's summer home was done in 1925, he and Rockefeller Jr. had become good friends and philanthropic partners. They shared a love for the arts, beautiful scenery, social justice, and civic responsibility. Although twenty years his senior, Rockefeller Jr. found Edsel's situation relatable. Both men were the only sons of immensely wealthy industrialist fathers and both had inherited the responsibility of their massive family fortunes. Each looked to use those fortunes to serve humanity and steer society towards a positive future. Rockefeller Jr. cherished the trait of modesty, a trait that he saw Edsel strongly demonstrate throughout his life. For that reason, Rockefeller Jr. held Edsel, "in the highest regard and esteem," describing him as, "so modest and so simple in his own living and in his association with his fellow men." Their summers spent together at Seal Harbor would undoubtedly include conversations about where they could best direct their philanthropic efforts.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1920s, 20th century, philanthropy, nature, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Ryan Jelso

Edsel Ford and the National Park Service

On August 25, 2016, the National Park Service celebrated its 100th birthday, a celebration that encouraged us to seek connections within our collections. This blog post is the first part of four that will trace Edsel Ford’s relationship to the national parks.

The landscapes preserved by the national parks are a source of inspiration. Not only do they document the natural history of America, but they are also integral in telling the story of humanity on the continent. They remain powerful educational tools, allowing citizens to reflect on their collective history and where they want society to go in the future. Responsible for protecting these historical, cultural, and scenic landscapes, the National Park Service owes much of its existence to the forward-thinking industrialists who supported the early environmental movements in America.

The National Park Service's birth can largely be attributed to the efforts of millionaire industrialist Stephen Mather. Using his wealth and political connections, Mather secured the job of Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior and went to Washington. Once there, he worked to lobby, fundraise, and promote an agency that could manage America's national parks and monuments. Finding success, Mather became the first director of the newly-formed National Park Service in 1916. At times, he even funded the agency's administration and bought land out of his own pocket. Mather was not the only affluent American to donate his time and wealth to the National Park Service.

The Rockefellers and Mellons, two of America's wealthiest families in the early 20th century, also became champions of the national parks. Specifically during this time period, the biggest player in national park philanthropic efforts was John D. Rockefeller Jr., the only son of oil magnate John D. Rockefeller. Among his many other National Park Service donations, Rockefeller Jr. was noteworthy for purchasing the land or donating the money that helped create the national parks of Acadia, Great Smoky Mountains, and Shenandoah, including the expansion of Grand Teton and Yosemite National Parks. Rockefeller dominated this philanthropic scene and ultimately influenced the only son of another wealthy industrialist to join him in his cause.

Edsel Ford, born to Henry and Clara Ford in 1893, was not born into wealth, but the success of Ford Motor Company in the early years of the 20th century led his father to become one of the richest men in America. This set Edsel down a path to inherit the responsibility of that wealth, a position in which he would thrive. Remarking that wealth "must be put to work helping people to help themselves," Edsel understood the elite position he was in and acted with grace throughout his life. Often described as altruistic, sensible, reserved and most importantly modest, Edsel would go on to channel his family's money into countless philanthropies including medical research, scientific exploration, the creative arts and America's national parks.

While this photograph was taken during the Fords' 1909 trip to Niagara Falls, they posed for the shot in a studio and were later edited into a photo of the falls. THF98007

At a young age, Edsel experienced some of the monuments and landscapes that make up our current national park system, creating memories that surely influenced him later in life. Family trips in 1907 and 1909 took Edsel to Niagara Falls, today a National Heritage Area in the park system. For the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909, Edsel accompanied his father by train to Denver and from there they took a scenic drive to Seattle where the exposition was being held. In 1914, he joined Thomas Edison, John Burroughs and his family as they spent time camping in the Florida Everglades. He also had the opportunity to visit the Grand Canyon at least four times in his life, with his first glimpse of the gorge occurring during a family trip to Southern California in 1906.

Visiting the Grand Canyon in 1906, Edsel sits here with his mother, Clara Ford, and Clara's mother, Martha Bryant. The canyon can be faintly seen in the background. THF255176

Edsel recorded a subsequent trip to the canyon in his diary during January of 1911. He wrote that he spent time hiking, visiting the Hopi House to watch Native American dances, and photographing the canyon. Photography would become one of many artistic hobbies Edsel pursued over the course of his life. Undoubtedly the beautiful vistas of the Grand Canyon provided a spark of creativity for the burgeoning young artist. The national parks and monuments had inspired creative sparks previously, allowing Edsel to illustrate this picture of the Washington Monument in 1909. These forays into the arts helped Edsel later become the creative force that took Ford Motor Company beyond the Model T and successfully into the industry of automobile design.

Edsel recorded his second Grand Canyon trip in his diary. Interestingly, Edsel also mentions he has heard of the deaths of Arch Hoxsey and John B. Moisant, two record-breaking pilots who died while performing separate air stunts on New Year's Eve of 1910. THF255172

Before Edsel made his dreams of car design a reality, Ford Motor Company had played a role in helping to improve accessibility to the landscapes of the national parks by making the automobile, specifically the Model T, affordable to the masses. In 1915, at age 21, Edsel took off in a Model T on a cross-country road trip with six of his friends. Departing from Detroit and heading to San Francisco, the trip allowed Edsel to again witness the scenic changes in the countryside as he traveled across the continent, something he had experienced on numerous family trips before. This time though, he was in charge of the places he explored. Making various stops during his expedition, Edsel visited the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, the desert of New Mexico and the Grand Canyon for a third time.

Edsel Ford and friends hike down Bright Angel Trail while visiting the Grand Canyon during their 1915 cross-country road trip. THF243915

The Grand Canyon must have left quite the impression on Edsel because, in November of 1916, he brought his new wife Eleanor Clay there on the way to their honeymoon in Hawaii. He wrote his parents from the El Tovar Hotel saying "We are surely having a great time. Walking and breathing this great air." They had spent the previous day visiting Grandview Point, a spot that continues to provide park goers with breathtaking views of the canyon. Edsel's new wife Eleanor would play an important role in his future national park endeavors. She exposed him to the rugged shores and natural beauty of the Maine coast -- a place where Edsel would cross paths with John D. Rockefeller Jr., establishing a friendship that would last a lifetime.

Operated by the Fred Harvey Company, which owned a chain of railroad restaurants and hotels, El Tovar Hotel was opened in 1905 through a partnership with the Santa Fe Railway. THF255180

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1910s, 1900s, 20th century, travel, philanthropy, nature, national parks, Ford family, Edsel Ford, by Ryan Jelso