Gilbert Rohde and D.J. De Pree: The Partnership that Modernized the Herman Miller Furniture Company

Brochure for Chicago Merchandise Mart Exhibit, "Herman Miller Modern for Your Home," 1935-1940 (THF229429)

West Michigan is known for its furniture. Furniture factories-turned-apartment or office buildings can be seen throughout Grand Rapids and its surroundings—some with company names like Baker Furniture, John Widdicomb Co., and Sligh Furniture still visible, painted on the brick exterior. While fewer in numbers today than in 1910, West Michigan still boasts numerous major furniture manufacturers. One of these, the Herman Miller Furniture Company in Zeeland, is known around the world for its long history of producing high quality modern furniture—but the Herman Miller name was not always synonymous with “modern.”

A young man named Dirk Jan (D.J.) De Pree began working as a clerk at the Zeeland-based Michigan Star Furniture Company in 1909, after graduating from high school. It was a small company and De Pree excelled, partly due to his appetite for reading books about business, accounting, and efficiency. Just a decade after starting with the company, he was promoted to president. In 1923, De Pree convinced his father-in-law, Herman Miller, to go in with him to purchase the majority of the company’s shares. The furniture company was renamed the Herman Miller Furniture Company in honor of De Pree’s father-in-law’s contribution, although Miller was never involved in its operation. Renamed, rebranded, and under new ownership, D.J. De Pree pushed a new culture of quality and good design that, he hoped, would help the company stand out amongst a competitive and crowded West Michigan furniture industry.

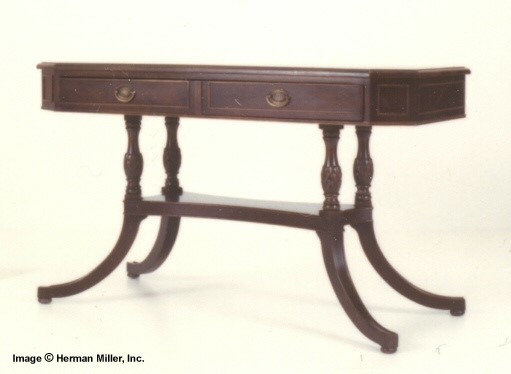

Dressing Table, ca. 1933 (Object ID: 89.177.112), Image copyright: Herman Miller, Inc.

At the time, many West Michigan furniture companies were producing stylistically similar pieces that were essentially reproductions of historic forms, especially Colonial and European Revivals. Most of the manufacturers “designed” furniture by copying from books or authentic vintage furniture found in museums. The best designers were known to be the most faithful copyists. The Herman Miller Furniture Company manufactured primarily reproduction furniture until the early 1930s. Their furniture lines were typically very ornate and sold in large suites—and following in the footsteps of other West Michigan companies, Herman Miller released new lines with each quarterly furniture market, despite the undue pressure this placed upon them.

As the Great Depression crippled industry across America in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Herman Miller Furniture Company struggled to survive. With bankruptcy on the horizon, D.J. De Pree reflected on the shortcomings of the furniture industry and issues within the company. A devoutly religious man, he also prayed. Whether by divine intervention or regular old coincidence, Gilbert Rohde—a young designer that would leave an indelible mark on the Herman Miller Furniture Company—walked into the company’s Grand Rapids showroom in July of 1930, bringing with him the message of Modernism.

The Herman Miller Furniture Company, Makers of Fine Furniture, Zeeland, Michigan, 1933 (Left: THF64292, Right: THF64290). Herman Miller continued to produce historic revival furniture, like the above Chippendale bedroom suite, even while embracing the more modern Gilbert Rohde lines, like the above No. 3321 Dining Room Group.

Born in New York City to German immigrants in 1894, Gilbert Rohde (born Gustav Rohde) showed aptitude for drawing at a young age—he claimed to have drawn an identifiable horse by the age of two-years-old! He was admitted to Stuyvesant High School in 1909, which was reserved for gifted young men. There, he designed covers for the school’s literary magazine, won drawing contents, and began to experiment with furniture design. While he had aspirations (and demonstrated aptitude) to become an architect, he began working as an illustrator and later, a commercial artist. He was successful in this venture for years and learned invaluable lessons about advertising and marketing which would help him—and his future clients—tremendously in the years to come. With determination to become a furniture designer, in 1927 Rohde departed on a months-long European tour of sites associated with the modern design movement. Among his stops, he visited the Bauhaus design school in Germany and the Parisian design studios that featured the modernist ideas exhibited in the breakthrough Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes of 1925. Returning to the United States months later, he began designing furniture with a clear European modern influence and soon began to focus on designing mass-produced furniture for industry, namely for the Heywood-Wakefield Company of Massachusetts.

Dresser, 1933-1937 (THF156178). An early example of Rohde-designed furniture manufactured by Herman Miller, this dresser was designed for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair’s “Design for Living Home.” The house and its furniture garnered broad public acclaim, benefitting the budding Rohde and Herman Miller partnership.

By 1930, Rohde was looking for more clients. He visited the Herman Miller showroom in Grand Rapids, Michigan—at the end of a long day of denials by other manufacturers—and met D.J. De Pree. Rohde argued that modern furniture was the future and told him, “I know how people live and I know how they are going to live.” This confidence, despite few years of actual furniture design, convinced De Pree to give Rohde a chance at designing a line for Herman Miller. Further, Rohde was willing to work on a royalty arrangement with a small consultation fee instead of all cash up front. In combination with Herman Miller’s already-precarious financial situation, these factors helped to offset some of the risk in producing this forward-thinking furniture. Herman Miller began selling Rohde’s first design, an unadorned, modern bedroom suite in 1932, but still played it safe by continuing to sell historic revival lines alongside Rohde’s modern furniture. As design historian Ralph Caplan notes, in those early years, Herman Miller was “like a company unsure of what it wanted to be when it grew up.” But Rohde’s furniture sold. By the early 1940s, Rohde’s modern lines made up the vast majority of Herman Miller’s output.

Left: Coffee Table, 1940-1942 (THF35998), Right: Rohde Sideboard, 1941-1942 (THF83268). Gilbert Rohde admired the Surrealist Art Movement. In his early 1940s Paldao Group, the forms and materials pay homage to the work of the Surrealists—and were the first biomorphic forms used in furniture manufactured in the United States.

Tragically, Rohde’s tenure at Herman Miller was cut short by his untimely death at the age of 50 in 1944, but his impact is lasting. Rohde’s emphasis on simplicity and functionality of design meant the materials and the manufacturing had to be of the highest quality—this honesty of design and emphasis on quality appealed to De Pree’s Christian values. It remains a hallmark of Herman Miller’s furniture to this day and undoubtedly contributed to the longevity of Rohde’s furniture sales. Sales of Rohde’s furniture did not slow the season after it was introduced, like many of the historic reproductions. The Laurel Line, Rohde’s first coordinated living, dining, and sleeping group, remained in production almost his entire tenure with Herman Miller. D.J. De Pree recounted that his lines often sold for 5-10 years instead of the 1-3 that was typical of the historic reproduction styles. Rohde’s design work for Herman Miller extended far beyond furniture and into advertising, catalogues, and showrooms, and he advised on the manufacture of his furniture too. This expansion of the designer’s role and the creative freedom allowed by D.J. De Pree came to define Herman Miller’s relationship with designers and then the company itself.

Rohde Modular Desk, 1934-1941 (THF159907). This Laurel Group desk was part of one of Rohde’s early—and most successful—lines for Herman Miller. It was part of a coordinated modular line, which meant that new pieces would be added regularly over years. This was in opposition to the new lines for each quarterly furniture market approach that D.J. De Pree counted as an “evil” of the furniture industry.

Cover and interior page from Catalog for Herman Miller Furniture, "20th Century Modern Furniture Designed by Gilbert Rohde," 1934 (left: THF229409, right: THF229411). Gilbert Rohde expanded the role of the designer during his tenure at Herman Miller. In this 1934 catalogue, he was educator as well as designer, explaining to the consumer that “Every age has had its modern furniture…When Queen Elizabeth furnished her castles, she did not order her craftsmen to imitate an Egyptian temple…”

Gilbert Rohde and D.J. De Pree transformed the Herman Miller Furniture Company—from one manufacturing reproductions at the brink of bankruptcy, to one revolutionizing the world of modern furniture. George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames, Isamu Noguchi, Alexander Girard and countless others were able to make incredible leaps in the name of modernism, largely due to the culture and partnership developed by Gilbert Rohde and D.J. De Pree. In George Nelson’s words, “we really stood on Rohde’s shoulders.”

Katherine White is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

20th century, Michigan, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White

Walt Disney and His Creation of Disneyland

Postcard, “Disneyland,” 1975. THF 207872

Welcome to Disneyland!

Disneyland was created from a combination of Walt Disney’s innovative vision, the creative efforts and technical genius of the team he put together, and the deep emotional connection the park elicits with guests when they visit there. Walt Disney himself claimed, “There is nothing like it in the entire world. I know because I’ve looked. That’s why it can be great: because it will be unique.” Here’s the story of how Walt created Disneyland, the first true theme park.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205151

Disneyland is much like Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World in Florida, but it’s smaller and more intimate. To me, it seems more “authentic.” It’s like you can almost feel the presence of Walt Disney everywhere because he had a personal hand in things.

Walt Disney posing the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, 1940. THF 109756

In creating Disneyland, Walt Disney challenged many rules of traditional amusement parks. We’ll see how. But first…since he insisted that everyone he met call him by his first name, that’s what we’ll do. From now on, I’ll be referring to him as Walt!

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205155

DISNEY INSIDER TRIVIA: Do you know where Walt Disney’s inspiration for Main Street, USA, came from?

ANSWER: Born in 1901, Walt loved the bustling Main Street of his boyhood home in Marceline, Missouri. Marceline later provided the inspiration for Disneyland’s Main Street, USA.

Map and guide, “Hollywood Movie Capital of the World,” circa 1942. THF 209523

After trying different animated film techniques in Kansas City, Walt left to seek his fortune in Hollywood.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Valentine, 1938. THF 335750

There, he made a name for himself with Mickey Mouse (1927) and—10 years later—the first full-length animated feature film, Snow White. Walt innately understood what appealed to the American public and later brought this to Disneyland.

Handkerchief, circa 1935. THF 128151

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: Here’s how Mickey Mouse looked on a child’s handkerchief in the 1930s.

“Merry-Go-Round-Waltz,” 1949. THF 255058

Walt claimed the idea of Disneyland came to him while watching his two daughters ride the carousel in L.A.’s Griffith Park. There, he began to imagine a clean, safe, friendly place where parents and children could have fun together!

Herschell-Spillman Carousel. THF 5584

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: That carousel in Griffith Park was built in 1926 by the Spillman Engineering Company—a later name for the Herschell-Spillman Company, the company that made the carousel now in our own Greenfield Village in 1913! Here’s what ours looks like.

Coney Island, New York, circa 1905 – THF 241449

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: For more on the evolution of American amusement parks, see my blog post, “From Dreamland to Disneyland: American Amusement Parks.”

1958 Edsel Bermuda Station Wagon Advertisement, “Dramatic Edsel Styling is Here to Stay.” THF 124600

The decline of these older amusement parks ironically coincided with the rapid growth of suburbs, freeways, car ownership, and an unprecedented baby boom—a market primed for pleasure travel and family fun!

Young Girl Seated on a Carousel Horse, circa 1955. THF 105688

Some amusement parks added “kiddie” rides and, in some places, whole new “kiddie parks” appeared. But that’s not what Walt had in mind. Adults still sat back and watched their kids have all the fun.

Chicago Railroad Fair Official Guidebook, 1948. THF 285987

Walt’s vision for his family park also came from his lifelong love of steam railroads. In 1948, he and animator/fellow train buff Ward Kimball visited the Chicago Railroad Fair and had a ball. Check out the homage to old steam trains in this program.

Tintype of Walt and Ward. THF 109757

After the Railroad Fair, Walt and Ward visited our own Greenfield Village, where they enjoyed the small-town atmosphere during a special tour. At the Tintype Studio, they had their portrait taken while dressed up as old-time railroad engineers.

Walt Disney and Artist Herb Ryman with illustration proposals for the Ford Pavilion, 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. THF 114467

DISNEY INSIDER TRIVIA: Walt Disney used the word Imagineers to describe the people who helped him give shape to what would become Disneyland. What two words did he combine to create this new word?

ANSWER: Walt hand-picked a group of studio staff and other artists to help him create his new family park. He later referred to them as Imagineers—combining the words imagination and engineering. This image shows Walt with Herb Ryman—one of his favorite artists.

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: For a deeper dive on an early female Imagineer, see my blog post, “The Exuberant Artistry of Mary Blair.”

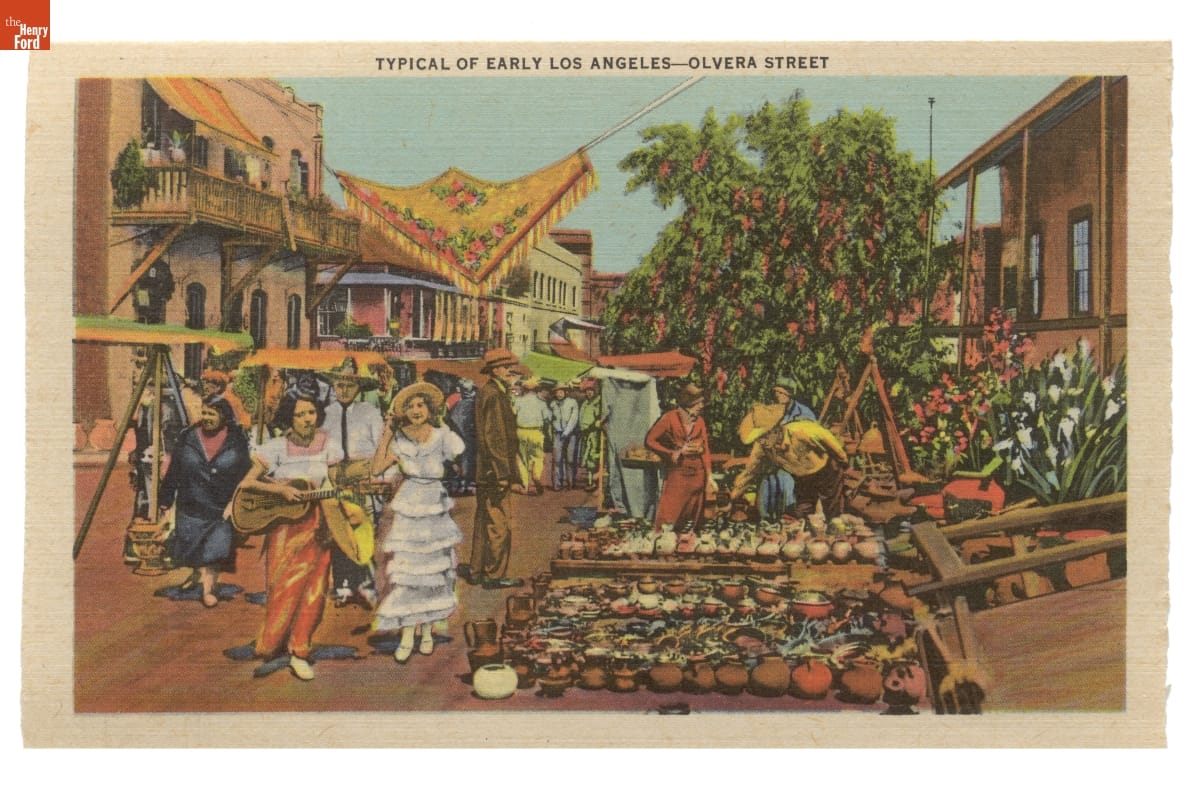

Postcard viewbook of Los Angeles, California. THF 7376

Walt continually looked for new ideas and inspiration for his park, including places around Los Angeles, like Knott’s Berry Farm, the Spanish colonial-style shops on Olvera Street, and the bustling Farmer’s Market—one of Walt’s favorite hangouts.

Times Square – Looking North – New York City, August 7, 1948. THF 8840

Walt also worried about how people got fatigued in large and crowded environments. So, he studied pathways, traffic flow, and entrances and exits at places like fairs, circuses, carnivals, national parks, museums, and even the streets of New York City.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205154

Studying these led to Walt’s first break from traditional amusement parks: the single entrance. Amusement park operators argued this would create congestion, but Walt wanted visitors to experience a cohesive “story”—like walking through scenes of a movie.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205152

Another new idea in Walt’s design was the central “hub,” that led to the park’s four realms, or lands, like spokes of a wheel. Walt felt that this oriented people and saved steps. Check out the circular hub in front of the castle on this map.

Disneyland cup & saucer set, 1955-1960. THF 150182

A third rule-challenging idea in Walt’s plan was the attractor, or “weenie” for each land—in other words, an eye-catching central feature that drew people toward a goal. The main attractor was, of course, Sleeping Beauty Castle.

To establish cohesive stories for each land, Walt insisted that the elements in them fit harmoniously together—from buildings to signs to trash cans. This idea—later called “theming”—was Walt’s greatest and most unique contribution.

Halsam Products, “Walt Disney’s Frontierland Logs,” 1955-1962. THF 173562

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: This Lincoln Logs set reinforced the look and theming of Frontierland in Disneyland.

Woman’s Home Companion, March 1951. THF 5540

DISNEY INSIDER TRIVIA: Which came first, Disneyland the park, or Disneyland the TV show?

ANSWER: To build his park, Walt lacked one important thing—money! So, he took a risk on the new medium of TV. While most Hollywood moviemakers saw TV as a fad or as the competition, Walt saw it as “my way of going direct to the public.” Disneyland the TV show premiered October 27, 1954—with weekly features relating to one of the four lands and glimpses of Disneyland the park being built.

Child’s coonskin cap, 1958-1960. THF 8168

The TV show was a hit, but never more than when three Davy Crockett episodes aired in late 1954 and early 1955.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205153

Disneyland, the park, opened July 17, 1955, to special guests and the media. So many things went wrong that day that it came to be called “Black Sunday.” But Walt was determined to fix the glitches and soon turned things around.

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: For more on “Black Sunday” and the creation of Disneyland, see my blog post, “Happy Anniversary, Disneyland.”

Walt Disney World Magic Kingdom guidebook, 1988. THF 134722

Today, themed environments from theme parks to restaurants to retail stores owe a debt to Walt Disney. Sadly, Walt Disney passed away in 1966. It was his brother Roy who made Walt Disney World in Florida a reality, beginning with Magic Kingdom in 1971.

Torch Lake steam locomotive pulling passenger cars in Greenfield Village, August 1972. THF 112228

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: In an ironic twist, a steam railroad was added to the perimeter of Greenfield Village for the first time during a late 1960s expansion—an attempt to be more like Disneyland!

Marty Sklar speaking at symposium for “Behind the Magic” at Henry Ford Museum, November 11, 1995. THF 12415

In 2005, The Henry Ford celebrated Disneyland’s 50th anniversary with a special exhibit, “Behind the Magic: 50 Years of Disneyland.” The amazing and talented Marty Sklar, then head of Walt Disney Imagineering, made that possible.

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: Check out this blog post I wrote to honor Marty’s memory when he passed away in 2017.

During these unprecedented times, Disneyland has begun its phased reopening. When you feel safe and comfortable going there, I suggest adding it to your must-visit (or must-return) list. When you're there, you can look around for Walt Disney's influences, just like I do.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Continue ReadingCalifornia, 20th century, popular culture, Disney, by Donna R. Braden, #THFCuratorChat

The Railroad Roundhouse

The Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse in Greenfield Village. (THF2001)

Symbolic Structure

Apart from the ubiquitous small-town depot, there may be no building more symbolic of railroading than the roundhouse. At one time, thousands of these peculiar structures were spread across the country. Inside them, highly-skilled workers used specialized tools, equipment, and techniques to care for the steam locomotives that powered American railroads for more than a century.

Today, only a handful of American roundhouses are still in regular use maintaining steam locomotives. Visitors to The Henry Ford have the rare opportunity to see one of these buildings in action. The Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse is the heart of our Weiser Railroad, the steam-powered excursion line that transports guests around Greenfield Village. Our dedicated railroad operations team maintains our operating locomotives using many of the same methods and tools as their predecessors of earlier generations.

Workers pose outside the Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse on its original site in Marshall, Michigan, circa 1890-1900. (THF129728)

Roundhouses were built wherever railroads needed them, whether in the heart of a large city or out on the open plains. In 1884, the Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Railroad constructed its roundhouse in Marshall, Michigan – the approximate midpoint on DT&M’s 94-mile line between the Michigan cities of Dundee and Allegan. Larger railroads operated multiple roundhouses, generally located at 100-mile intervals – roughly the distance one train crew could travel in a single shift. The roundhouses on these large railroads served as relay points where a new locomotive (and crew) took over the train while the previous locomotive went in for maintenance.

Roundhouses gave crews space to work, but also kept locomotives and equipment within easy reach, as seen in this 1924 view inside a Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad roundhouse. (THF116641)

Circular Reasoning

Railroads embraced the circular roundhouse design for a variety of reasons. It allowed for a compact layout, keeping the locomotives and equipment inside closely spaced and within accessible reach. The building pattern was flexible, permitting a railroad to add stalls to an existing roundhouse (or remove them) as conditions warranted. The turntable – used to access each roundhouse stall – simplified trackwork and didn’t require multiple switches to move locomotives from place to place.

Not all “roundhouses” were round. See this example from Massachusetts, photographed in 1881. But round structures offered decided advantages over rectangular buildings. (THF201503)

Likewise, the single-space stalls and turntable allowed for convenient access to any one locomotive. Long, rectangular service buildings required moving several locomotives to extract one located at the end of a track. (If you’ve ever had to ask people to move their cars from a driveway so that you could get yours out, then you’ll recognize this problem.) The turntable had the added benefit of being able to reverse the direction of a locomotive without the need for a space-consuming “wye” track.

People made the roundhouse work, like this man at the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton’s Flat Rock, Michigan, roundhouse photographed in 1943. (THF116647)

A Variety of Trades

Of course, roundhouses were more than locomotives, turntables, and tracks. Their most important feature was the variety of skilled tradespeople and unskilled workers who made them function. Boilermakers, blacksmiths, machinists, pipefitters, and more all labored within a roundhouse’s stalls. Large roundhouses might employee hundreds of people. The environment was noisy and smoky, and much of the work was dangerous and dirty – emptying ash pans, cleaning scale from boilers, greasing rods and fittings – but it had its advantages. Unlike train crews who worked all hours and spent long periods away from home, roundhouse workers enjoyed more regular schedules and returned to their own beds at the end of the day.

Roundhouses faded after the transition from steam to diesel, illustrated by this 1950 photo taken at Ford’s Rouge plant. (THF285460)

Roundhouses Retired

With the widespread adoption of diesel-electric locomotives following World War II, the roundhouse gradually disappeared from the American railroad. Diesels needed far less maintenance than steam engines, and required fewer specialized skills from the crews that serviced them. Following dieselization, a few roundhouses were modified to maintain the new locomotives, while others were put to other railroad uses. Some were preserved as museums, and a few were even converted into shopping centers or restaurants. But most were simply torn down or abandoned.

The Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse followed a similar pattern of slipping into disuse – though in its case, it was more a victim of the DT&M Railroad’s failing fortunes than the transition to steam. After a series of acquisitions and mergers, the little DT&M became a part of the Michigan Central. The much larger MC had no need for DT&M’s Marshall roundhouse, and the new owner repurposed the structure into a storage building. In 1932, the roundhouse was abandoned altogether. It was in a dilapidated condition by the late 1980s, when The Henry Ford began the process of salvaging what components we could. After many years of planning and fundraising, the reconstructed DT&M Roundhouse opened to Greenfield Village guests in 2000. Clearly, the building itself is rare enough, but it’s the work that goes on inside that makes it truly special. Today, the DT&M Roundhouse is one of the few places in the world where visitors can still observe the crafts and skills that kept America’s steam railroads rolling so many years ago.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 19th century, railroads, Michigan, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Matt Anderson

Greenfield Village Tintype Studio

THF151617

Just before the official dedication of his museum and historical village in 1929, Henry Ford decided he wanted a tintype studio added to the village. Ford’s staff worked feverishly to construct and furnish this building in one day! It was designed to look like a small tintype photographic studio from the 1870s and 1880s. Last minute details, including curtains hastily brought from the home of Ford’s photographer and hung at the windows, helped complete the look.

The Greenfield Village Tintype Studio has three rooms:

- A dressing room or “primping” room where customers got ready for their picture

- The studio or “operating room,” originally equipped with head rests (to hold people’s heads still so the picture wouldn’t come out blurry), posing chairs, cameras, and a painted backdrop. Large windows provided maximum light for the photographer.

- The darkroom for preparing and developing the tintypes

Ford’s staff built this tintype studio in one day—just in time for the rainy dedication of Greenfield Village on October 21, 1929. THF139188

Tintypes, the popular “instant photographs” of the mid-1800s, could be produced in a matter of minutes at a price the average American could afford. This quick, affordable process gave more people than ever before the chance to have a real likeness of themselves.

Though tintypes became less popular as new and better forms of photography replaced them, traveling tintypists found work at country fairs, summer resorts and other vacation spots as late as the 1930s. One such tintypist was Charles Tremear, who eventually gave up photography and went to work for Ford Motor Company in 1909. When Henry Ford heard that Tremear had been the “last wandering tintypist in America,” he transferred him to Greenfield Village.

Charles Tremear, the “last wandering tintypist in America,” ran the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio from 1929-1943. THF132794

Charles Tremear ran the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio from 1929 until his death in 1943. The studio was a popular destination. Tremear produced more than 40,000 tintypes during his tenure, including many of celebrities. Joe Louis, Walt Disney, and Henry Ford numbered among the famous people who posed for tintype portraits in Greenfield Village.

Though tintypes are no longer made in the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, it's still a great place to learn more about the tintype process and practice some poses. Selfies are welcome!

20th century, Michigan, Dearborn, photography, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

Refrigerated rail transport revolutionized meatpacking and other agricultural industries by broadening the markets for fresh produce. Refrigerator cars enabled farmers in regions with extended growing seasons, such as Florida and California, to market perishable foods across the country--greatly expanding agricultural production and allowing people in cold climates to enjoy fresh fruits and vegetables year-round.

Serious experimentation with ice-cooled refrigerated railroad car design began in the 1860s. At first, refrigerator cars primarily shipped meat from Chicago to cities in the eastern United States. But by the late 1890s, refrigerated shipping of all kinds of perishable foods by railroad had become big business. When this refrigerator car was built in 1924, there were 150,000 such cars in use.

Fruit Growers Express Company, a pioneer in refrigerator car service, operated this car from 1924 until 1971. THF68309

This car was built and operated by Fruit Growers Express Company of Alexandria, Virginia, a pioneer in refrigerator car service. To cool the car, laborers loaded blocks of ice through roof hatches at each end into two large bunkers. Fans driven by the car’s axles helped to circulate the cool air. Mats of felted flax or cattle hair lined the floor and walls of the car to insulate delicate cargo against both hot and cold temperature extremes.

Ice melted quickly in refrigerator cars, despite their clever design. Fruit Growers Express and other refrigerator car companies maintained a nationwide network of ice-making and ice-loading facilities to support their business. They carefully coordinated transportation schedules and labor, because to prevent spoiled cargo, trains had to reach icing stations on time and workers had to be available to move food to market quickly once it reached its destination. Special trains made up entirely of refrigerator cars were sometimes given right-of-way priority over other traffic.

Refrigerator car companies carefully coordinated transportation schedules and labor to prevent cargo from spoiling before delivery to market. THF145082

Mechanically cooled refrigerator trucks began to replace rail transport for perishable goods after World War II, but The Henry Ford’s refrigerator car had a lengthy career. Following a rebuild in 1948, it remained in service until 1971. Today, in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, it serves as an example of a railway innovation that revolutionized American agriculture.

Additional Readings:

Food on the Move

Florida oranges on grocery store shelves in Minnesota. Fresh blueberries from Chile at fruit markets in New England -- in the middle of winter. Beef processed and packaged in Texas purchased and consumed by families in the Carolinas. Whether we realize it or not, our relationship with food is directly dependent on the transportation industry. And it has been for nearly 200 years.

“As the U.S. became more urbanized, the demand for fresh food shipped over long distances increased,” said Matt Anderson, curator of transportation at The Henry Ford. Before widespread adoption of refrigerated railcars after the Civil War, such variety of eats was unfathomable. People ate what was grown in their immediate area. Farming was a local endeavor. “Refrigerated cars revolutionized the agriculture industry,” said Anderson. A growing desire to move processed and packaged beef hundreds of miles, rather than a whole herd of living cattle, sparked the larger movement to cool things down inside the railcars.

At first, refrigerator cars primarily shipped meat from Chicago to cities in the eastern United States. THF110235

The Henry Ford has a refrigerator car, built in 1924 for Fruit Growers Express, in its collection. Cooling was provided by ice, loaded through roof hatches into large compartments at each end of the car. Fans, driven by the car’s axles, helped to circulate the cool air. “I consider our Fruit Growers Express car to be the cornerstone of our food transportation collection,” said Anderson. “Refrigerator cars like this changed the American diet, permitting fresh produce and meat to be shipped anywhere in the U.S.” Discover how West Coast fruit growers marketed their produce to the new markets opened up by refrigerated rail transport in this blog post.

Refrigerator cars enabled farmers in regions with extended growing seasons to market fresh produce, like California grapefruit, year-round across the country. THF295680

And while we’re talking about moving fruit and keeping it fresh, ponder this: When McDonald’s introduced sliced apples to its menu in 2011, it quickly became the largest purchaser of apple slices at 60 billion pounds per year. Give some thought to who grows all those apples and how they get where they need to go.

This post originally ran in the June-December 2015 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Jenny Young Chandler: Photojournalist

When Jenny Chandler photographed these Brooklyn children playing games about 1900, she also unwittingly provided us with a “cameo” image of herself. The photograph includes her shadow, slightly bent over her camera as she takes the shot. THF 38025

In 1890, 25-year-old Jenny Young Chandler suddenly found herself a widow with a two-month-old baby to provide for. This heart-rending personal loss would take her on an unexpected path--one as a photojournalist and feature writer for the New York Herald, capturing life in Brooklyn, New York and vicinity. Over the next three decades, Chandler’s sensitive, insightful photography would depict people from all walks of life and the world in which they lived--a legacy preserved in over 800 glass plate negatives.

Jenny Chandler was born in 1865 in New Jersey to William Young and Mary Lewis Young. An only child, Jenny was raised by her father and stepmother, Sarah Bennett Young. The family moved to Brooklyn, New York, when Jenny was six, so her father could work as the city editor for the New York Sun newspaper. Jenny followed the normal “career path” for a young lady at that time, marrying William G. Chandler on April 25, 1888. The groom, a neighbor, worked as a sales representative for a picture frame manufacturer. Jenny and William welcomed a son, William Young Chandler, on October 12, 1890. Two months later, Jenny’s husband died of typhoid fever. Chandler unexpectedly needed to earn a living for herself and her child.

When Jenny Chandler embarked on her career, photographs were made by lugging a heavy camera, glass plate negatives and tripod. Understanding how the photo chemicals worked and how light and camera lenses interacted proved to be an exacting task. While photography was growing in popularity as a hobby for young women whose families could afford the equipment, as a profession, it was still considered a male domain. Yet Jenny Chandler mastered the technical details of camera and chemicals, then used her sensitivity and insight as a professional photojournalist to create evocative images of the world around her.

Jenny Chandler’s photographs have an immediacy—a “you are there” quality. She had a remarkable talent for portraying on film the lives of people of diverse economic and ethnic backgrounds. Chandler captured well-off Brooklyn girls and boys playing games, the exuberance of families enjoying the beach at Coney Island, the well-mannered curiosity of students on a museum visit, young girls bent over their sewing tasks, scruffy boys hanging out at the beach, children gathering tomatoes, a fisherman mending his net, shipwrights making wooden boats, and Norwegian immigrant women laboring at their farm work.

In 1922, at the age of 56, Jenny Young Chandler died of a heart ailment. For nearly 10 years, her photographic legacy quietly remained in her Brooklyn home. The subsequent owner of the house, Betty R.K. Pierce--recognizing its importance--contacted Henry Ford hoping “to have Mrs. Chandler’s work preserved in some way.” Mrs. Pierce had read about Henry Ford’s museum and historical village, and thought the photographs particularly related to Ford’s collections. In May 1932, five large boxes containing the carefully packed 800 glass negatives were on their way to Dearborn.

The result of this donation is an amazing document of early 20th century life.

Cynthia Read Miller, former curator, photography & prints, and Jeanine Head Miller, curator of domestic life at The Henry Ford.

Brooklyn and its environs offered Jenny Chandler a varied palette of urban and rural scenes, wealthy and impoverished people, and daily work life and leisure experiences. Below are a few selections from her remarkable collection of photographs.

Coney Island’s beaches and amusement parks offered cooling breezes and leisure opportunities to New York City area residents. THF38292

Girls learn to cook at a trade school. THF38041

Girls visit a children’s museum in Brooklyn, 1900-1910. THF38128

A family enjoys an outing in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, about 1905. THF 38192

A photograph of residents in their backyard - a rare “behind the scenes” glimpse of everyday life. THF38085

Clearing streets of snow. THF38073

“Tomboy of Darby Patch, Nellie punching bag.” In “The Patch,” a down-at-the-heels part of Brooklyn, the majority of residents were working class Irish immigrants. THF38251

A gypsy family enjoys an outdoor meal. THF241184

Boat Builders, New York, 1890-1915. THF38018

Children in front of a Gowanus Canal house, Brooklyn, New York. Gowanus Canal was a busy - and polluted - domestic shipping canal. THF38009

Gathering radishes in Ridgewood. Ridgewood - a neighborhood that straddled the Queens/Brooklyn boundary - remained largely rural until about 1900. Buildings in the background attest to the increasing urbanization of the area. THF38392

Norwegian immigrant women laboring at their farm work, about 1900. THF38397

It was so difficult to choose only a few of Jenny Chandler’s photographs! You can enjoy hundreds more of her images in our digital collections.

20th century, 19th century, New York, communication, women's history, photography, photographs, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Cynthia Read Miller

Lady and the Tramp Celebrates 65 Years

June 1955 magazine advertisement for the release of Lady and the Tramp. THF145583

Although this animated feature film received mixed reviews when it was first released on June 22, 1955, Walt Disney’s Lady and the Tramp has since become a classic. It is beloved for its songs, its story, its gorgeously rendered and meticulously detailed settings, and its universal themes of love and acceptance—not to mention that scene with the spaghetti! Numerous story artists and animators contributed their talents to creating this film, but it would take years before Walt Disney would finally give it his nod of approval.

Unlike other Disney animated films of the time, Lady and the Tramp is not based upon a venerable old fairy tale or a previously published book. Its origins can be traced back to 1937, when Disney story artist Joe Grant showed Walt Disney some sketches and told him of his idea for a story based upon the antics of his own English Springer Spaniel named Lady, who was “shoved aside” when the family’s new baby arrived. Walt encouraged Grant to develop the story but was unhappy with the outcome—feeling that Lady seemed too sweet and that the story didn’t have enough action. For the next several years, Grant and other artists worked on a variety of conceptual sketches and many different approaches.

In 1945, the storyline took a drastic turn, which ultimately led to its final film version. That year, Walt Disney read a magazine short story called, “Happy Dan, the Cynical Dog.” Here, in the story of a cynical, devil-may-care dog, Walt found the perfect foil for the prim and proper Lady. By 1953, the film had evolved to the point that Walt asked Ward Greene, the short story’s author, to write a novelization of it. It is Greene—not Joe Grant—who received credit in the final film. Walt couldn’t resist adding a personal tidbit to the story. According to his telling of the story, the opening scene came from his own experience of giving his wife a puppy as a gift in a hat box to make up for having forgotten a dinner date with her.

Interestingly, the spaghetti-eating scene was almost cut, as Walt Disney initially thought it was silly and unromantic. But animator Frank Thomas had such a strong vision for the scene that he completed all the animation for it before showing it to Walt, who was so impressed he agreed to keep in the now-iconic scene.

1955 charm bracelet of the dogs in Lady and the Tramp, likely a souvenir obtained at Disneyland. THF8604

Since the dogs were the main characters of the film, it seemed only natural to both show and tell the story from the dogs’ point of view. The animators studied many real dogs to capture their movements, behaviors, and personalities, while the scenes themselves were shot from a low “dog’s-eye-view” perspective.

A depiction of Main Street, U.S.A. at Disneyland from the 1955 Picture Souvenir Book to the park. THF205154

The film’s setting—early 20th century small-town America—referenced Walt Disney’s own return to his roots, particularly his growing up in the small town of Marceline, Missouri. As the setting was coming to life on film, a real live 3D version of it was being constructed at Disneyland, Walt Disney’s new park in Anaheim, California. Disneyland opened a mere three weeks after the film was released.

Although the setting hearkened back to the past, the filmmaking technique that Walt chose was typically state-of-the-art. As Walt marked the growing interest in widescreen film technology, he decided this would be the first of his animated films to use CinemaScope. To fill in the extra-wide space of this format, the animators extended the backgrounds—resulting in settings that are unusually breathtaking, detailed, mood-setting and, when the story called for it, filled with dramatic tension. Unfortunately, many theatres were not equipped with CinemaScope, so Walt decided that two versions of the film had to be created, forcing layout artists to scramble to restructure key scenes for a standard format as well. CinemaScope ultimately proved too expensive and did not last past the early 1960s. But its influence on Lady and the Tramp lives on—a testament to Walt’s commitment to filmmaking innovation.

Although souvenirs related to Lady and the Tramp are hard to come by these days, I was thrilled to find these salt-and-pepper shakers and collectible pins over several visits to Walt Disney World.

I saw Lady and the Tramp when it was re-released in theatres in 1962. I was nine years old at the time and I was completely enraptured. The details and setting—from the frilly ladies’ dresses, dapper men’s suits, and overstuffed furniture inside Lady’s house to the horses’ clip-clopping down the cobblestone streets—seemed like old photographs come to life. Taking in these details on the big screen as a girl, I was transfixed. Is this where my interest in history began?

After seeing Lady and the Tramp at the movies, I also became obsessed with wanting a dog. Not just any dog. I wanted Lady, or a cocker spaniel as close to Lady as I could get. I dreamed of her, drew pictures of her, transferred her personality onto the stuffed dogs I inevitably got as presents. When I was in eighth grade, my parents finally relented. One day my Mom surprised us and took us kids down to the animal shelter to get a dog. It wasn’t a cocker spaniel. But we did find a little golden-haired puppy that was a fine substitute.

I don’t know that I thought much of Tramp when I was a girl. He was wayward, a nuisance, too different. But from my older perspective, I see that Lady meeting, and ultimately falling for, Tramp was really a symbol of what happens in your life. Forced out of your comfort zone, broadening your horizons, seeing things from new perspectives, taking life’s curves with grace until, rather than resisting it, you accept it—even embrace it.

Who knew, when I was a girl, that this movie was not just about dogs but about life?

Note: The complete story of the making of Lady and the Tramp, including Joe Grant’s contributions, can be found in the bonus feature, “Lady’s Pedigree: The Making of Lady and the Tramp,” in the 50th Anniversary DVD of Lady and the Tramp.

Donna R. Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford’s Model i learning framework identifies collaboration as a key habit of an innovator. When considering inspirational collaborators from our collection, Charles and Ray Eames immediately came to mind. So, as part of The Henry Ford’s Twitter Curator Chat series, I spent the afternoon of June 18th sharing how collaboration played an important role in Charles and Ray Eames’ design practice. Below are some of the highlights I shared.

First things first, Charles and Ray Eames were a husband-and-wife design duo—not brothers or cousins, as some think! Although Charles often received the lion’s share of credit, Charles and Ray were truly equal partners and co-designers. Charles explains, "whatever I can do, she can do better... She is equally responsible with me for everything that goes on here."

THF252258 / Advertising Poster for the Exhibit, "Connections: The Work of Charles and Ray Eames," 1976

So when you see early advertisements that don’t mention Ray Eames as designer alongside Charles, know that she was equally responsible for the work. Here’s one such advertisement from 1947.

THF266928 / Herman Miller Advertisement, June 30, 1947, "Now Available! The Charles Eames Collection...."

And here’s another from 1952. I could go on, but I think you get the point!

THF66372 / Wood, Plastic, Wire Chairs & Tables Designed by Charles Eames, circa 1952

For more on Ray’s background and vital role in the Eames Office, check out this article from the New York Times, as part of their recently-debuted “Mrs. Files” series.

Charles and Ray Eames were experimenting with plywood when America entered World War II. A friend from the Army Medical Corps thought their molded plywood concept could be useful for the war effort—specifically for a new splint for broken limbs. Metal splints then in use were heavy and inflexible. Charles and Ray created a molded plywood version and sent a prototype to the U.S. Navy. They worked together and created a workable—and beautiful—solution for the military.

THF65726 / Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943

Out of these molded plywood experiments and products came the iconic chairs we know and love, like this lounge chair.

THF16299 / Molded Plywood Lounge Chair, 1942-1962

But Charles and Ray Eames wanted to make an affordable, complex-curved chair out of a single shell. The molded plywood checked some of their boxes, but the seat was not a single piece—not a single shell. They turned to other materials.

Around 1949, Charles brought a mock-up of a chair to John Wills, a boat builder and fiberglass fabricator, who created two identical prototypes. This is one of those prototypes—it lingered in Will's workshop, used for over four decades as a utility stool. The other became the basis for the Eames’ single-shell fiberglass chair.

THF134574 / Prototype Eames Fiberglass Chair, circa 1949

Charles and Ray recognized when their expertise fell short and found people in other fields to help them solve design problems. Their single-shell fiberglass chairs became a rounding success. Have you ever sat in one of them?

THF126897 / Advertising Postcard, "Herman Miller Furniture is Often Shortstopped on Its Way to the Destination...," 1955-1960

If you’ve been to the museum in the past few years, you’ve surely spent some time in another Eames project, the Mathematica: A World of Numbers…and Beyond exhibit. This too was a project full of collaborative spirit!

While those of us not mathematically inclined might have a hard time finding math fun, mathematicians truly think their craft is fun. Charles and Ray worked with these mathematicians to develop an interactive math exhibit that is playful.

THF169792 / Quotation Sign from Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond Exhibition, 1960-1961

Charles Eames said of science and play, “When we go from one extreme to another, play or playthings can form a transition or sort of decompression chamber – you need it to change intellectual levels without getting a stomachache."

THF169740 / "Multiplication Cube" from Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond Exhibition, 1960-1961

Charles and Ray Eames sought out expertise in others and worked together, understanding that everyone can bring something valuable to the table. This collaborative spirit allowed them to design deep and wide—solving in-depth problems across a multitude of fields.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. For a deeper dive into this story, please check out her long-form article, “What If Collaboration is Design?”

Eames, women's history, Model i, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White, #THFCuratorChat

1953 Ford Sunliner Pace Car

The 1953 Ford Sunliner, Official Pace Car of the 1953 Indianapolis 500. (THF87498)

As America’s longest-running automobile race, it’s not surprising that the Indianapolis 500 is steeped in special traditions. Whether it’s the wistful singing of “Back Home Again in Indiana” before the green flag, or the celebratory Victory Lane milk toast – which is anything but milquetoast – Indy is full of distinctive rituals that make the race unique. One of those long-standing traditions is the pace car, a fixture since the very first Indy 500 in 1911.

This is no mere ceremonial role. The pace car is a working vehicle that leads the grid into the start of the race, and then comes back out during caution laps to keep the field moving in an orderly fashion. Traditionally, the pace car’s make has varied from year to year, though it is invariably an American brand. Indiana manufacturers like Stutz, Marmon, and Studebaker showed up frequently, but badges from the Detroit Three – Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors – have dominated. In more recent years, Chevrolet has been the provider of choice, with every pace car since 2002 being either a Corvette or a Camaro. Since 1936, the race’s winning driver has received a copy of pace car as a part of the prize package.

Amelia Earhart rides in the pace car, a 1935 Ford V-8, at the 1935 Indianapolis 500. (THF256052)

Likewise, honorary pace car drivers have changed over time. The first decades often featured industry leaders like Carl Fisher (founder of Indianapolis Motor Speedway), Harry Stutz, and Edsel Ford. Starting in the 1970s, celebrities like James Garner, Jay Leno, and Morgan Freeman appeared. Racing drivers have always been in the mix, with everyone from Barney Oldfield to Jackie Stewart to Jeff Gordon having served in the role. (The “fastest” pace car driver was probably Charles Yeager, who drove in 1986 – 39 years after he broke the sound barrier in the rocket-powered airplane Glamorous Glennis.)

Ford was given pace car honors for 1953. It was a big year for the company – half a century had passed since Henry Ford and his primary shareholders signed the articles of association establishing Ford Motor Company in 1903. The firm celebrated its golden anniversary in several ways. It commissioned Norman Rockwell to create artwork for a special calendar. It built a high-tech concept car said to contain more than 50 automotive innovations. And it gave every vehicle it built that year a commemorative steering wheel badge that read “50th Anniversary 1903-1953.”

Henry Ford’s 1902 “999” race car poses with the 1953 Ford Sunliner pace car on Ford’s Dearborn test track. (Note the familiar clocktower at upper right!) (THF130893)

For its star turn at Indianapolis, Ford provided a Sunliner model to fulfill the pace car’s duties. The two-door Sunliner convertible was a part of Ford’s Crestline series – its top trim level for the 1953 model year. Crestline cars featured chrome window moldings, sun visors, and armrests. Unlike the entry-level Mainline or mid-priced Customline series, which were available with either Ford’s inline 6 or V-8 engines, Crestline cars came only with the 239 cubic inch, 110 horsepower V-8. Additionally, Crestline was the only one of the three series to include a convertible body style.

William Clay Ford at the tiller of “999” at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. (THF130906)

Ford actually sent two cars to Indianapolis for the big race. In addition to the pace car, Henry Ford’s 1902 race car “999” was pulled from exhibit at Henry Ford Museum to participate in the festivities. True, “999” never competed at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. But its best-known driver, Barney Oldfield, drove twice in the Indy 500, finishing in fifth place both in 1914 and 1916. Fittingly, Indy officials gave William Clay Ford the honor of driving the pace car. Mr. Ford, the youngest of Henry Ford’s grandchildren, didn’t stop there. He also personally piloted “999” in demonstrations prior to the race.

As for the race itself? The 1953 Indianapolis 500 was a hot one – literally. Temperatures were well over 90° F on race day, and hotter still on the mostly asphalt track. Many drivers actually called in relief drivers for a portion of the race. After 3 hours and 53 minutes of sweltering competition, the victory went to Bill Vukovich – who drove all 200 laps himself – with an average race speed of 127.740 mph. It was the first of two consecutive Indy 500 wins for Vukovich. Sadly, Vukovich was killed in a crash during the 1955 race.

Another view of the 1953 Ford Sunliner pace car. (THF87499)

Following the 1953 race and its associated ceremonies, Ford Motor Company gifted the original race-used pace car to The Henry Ford, where it remains today. Ford Motor also produced some 2,000 replicas for sale to the public. Each replica included the same features (Ford-O-Matic transmission, power steering, Continental spare tire kit), paint (Sungate Ivory), and lettering as the original. Reportedly, it was the first time a manufacturer offered pace car copies for purchase by the general public – something that is now a well-established tradition in its own right.

Sure, the Sunliner pace car is easy to overlook next to legendary race cars like “Old 16,” the Lotus-Ford, or – indeed – the “999,” but it’s a special link to America’s most important auto race, and it’s a noteworthy part of the auto racing collection at The Henry Ford.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Indiana, 20th century, 1950s, racing, race cars, Indy 500, Ford Motor Company, convertibles, cars, by Matt Anderson