Exploring Space (In Our Collections)

Motor Controllers for the Telescope at the Yerkes Observatory, Williams Bay, Wisconsin, 1932. THF134290

As long as humans have existed, we have looked up at the night skies and wondered about the stars, planets, moons, and more that we see there. Among the collections of The Henry Ford are objects that speak to the underlying tools and technologies that allow our understanding of the universe to grow. These artifacts demonstrate that whether we are observing celestial bodies or venturing into space, we design ways to overcome the many challenges of comprehending and exploring the cosmos.

We recently asked a number of our staff to pick a favorite artifact from among our space-related collections. Many of the selections showcase observatories—the process of constructing them, the machinery that makes them tick, and the ways they discover and share knowledge about our universe. Others cover the promise, challenges, and triumphs of our journeys beyond Earth's atmosphere.

All these artifacts, which you can explore in our Expert Set, tell the story of humanity's ambitious desire to learn more, understand more, and travel beyond our own world.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections and Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Exploring Entrepreneurship

Many experts describe entrepreneurship as the act of launching and managing a business venture. Those who establish these businesses are called entrepreneurs – but what does it really mean to be an entrepreneur?

The Parker Brothers honed their own entrepreneurship skills as they became a household name in the board game industry. Their “Make-a-Million” was a card game from the 1930s in which teams competed to win “tricks,” vying to become the first to reach one million dollars. THF91890

With the recent launch of the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, The Henry Ford hopes to become a recognized resource for the next generation of entrepreneurs and innovators. Through a $1.5 million grant, the institution-wide initiative will support the creation of a Speaker Series, youth programming, workshops, and Innovation Labs, which focus on cultivating an entrepreneurial spirit for the entrepreneurs of today and tomorrow. Additionally, four Entrepreneurs in Residence (EIRs) – beginning with local urban farmer Melvin Parson – will foster entrepreneurial learning for both youth and adults by engaging the EIR’s expertise in a project that connects The Henry Ford and the broader entrepreneurial community. Lastly, as a part of its commitment to connecting to and inspiring future entrepreneurs, the Initiative for Entrepreneurship will highlight the entrepreneurial stories within our collections. As Project Curator, I will work with Project Collections Specialist-Cataloger Katrina Wioncek and Project Imaging Technician Cory Taylor, as well as other staff from The Henry Ford, to identify and provide access to these stories through our Digital Collections and related content, including blog posts like this one.

The Henry Ford’s founder and namesake is one of the best-known American entrepreneurs. Persisting through multiple failures, Ford revolutionized the automotive industry and built a lasting enterprise in the Ford Motor Company. This 1924 photograph shows Ford posing in front of his first automobile – the 1896 Quadricycle – and the ten-millionth Model T to roll off the assembly line. THF113389

When I joined the project in January, my first task was to define “entrepreneur.” This proved to be challenging, as a simple Internet search produced dozens of definitions and interpretations. I soon discovered that the reason for the discrepancy is that there are several different categories of entrepreneurship, but the many sources I referenced agree on two points: all entrepreneurs launch and manage their own business and take on financial risks in creating that business.

Harvey Firestone was an entrepreneur in the tire making business, building the global brand Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. Here Henry Ford and Firestone observe an experimental watering system at Firestone Farm in Columbiana, Ohio in 1936. THF242526

Entrepreneurs can range from small business owners hoping to provide for their families to industry millionaires who head up large companies. There are also social entrepreneurs who seek to solve a local problem or large social enterprises hoping to save the world. The differences lie within their motivations and how they measure success. While most entrepreneurs are in the business to make a profit, social entrepreneurs have the goal of generating funds to contribute to a particular cause or solving a social problem. For-profit entrepreneurs measure success based on revenue or stock increases, while social entrepreneurs can be a blend of for-profit and non-profit agendas, assessing their impact on society while still generating revenue.

Social entrepreneur Lauren Bush Lauren was the first speaker in the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship Speaker Series. Lauren spoke about her business, FEED Projects, which seeks to tackle world hunger. Proceeds from her line of handbags and accessories provide meals to schoolchildren around the globe.

Throughout the two-year initiative we will highlight stories from our rich and varied collections that demonstrate the characteristics that entrepreneurs share. To name a few, entrepreneurs are creative thinkers, resourceful, passionate, highly motivated, willing to take risks, and able to persevere through hardship.

The Wright Brothers were fantastic inventors – their greatest invention being the first powered, controlled airplane. But the Wrights were better inventors than entrepreneurs as they never found great success in the manufacture or sale of their airplanes. An entrepreneur is tenacious and will do whatever it takes to see their plan through, regardless of setbacks and barriers. THF112405

Henry J. Heinz transformed the eating habits of late 19th– and early 20th—century America. He was passionate about providing a quality product and supported a strong working relationship with his employees. Here Heinz is in a cucumber field encouraging and motivating his workers. THF275188

The first six months of the initiative will focus on Social Transformation within Agriculture and the Environment – two of our collecting areas that encompass transformative social change in the history of how we grow and experience food. In addition to digital content and other programs created by the grant, local urban farmer and social justice activist Melvin Parson will serve as our first Entrepreneur in Residence, allowing us to connect these ideas to our community. Stay tuned over the next several months as we digitize related archival material and publish new entrepreneurial digital content!

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

We don’t generally associate Star Trek with historic automobiles (or, for that matter, with any automobiles). The classic original series is set circa 2265-2269, nearly 360 years after the first Model T rolled out of Ford’s Piquette Avenue Plant. By all evidence, Federation citizens in the 23rd century are content to get around by spaceship and shuttlecraft (with the notable exception of the Jupiter 8). But who can blame them for not driving? After all, we’re talking about a universe in which teleportation is a thing. But Star Trek isn’t an entirely auto-free zone. Through the clever storytelling devices of science fiction, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy encounter multiple 20th century American cars over the course of the show.

Ask fans to name their favorite episodes and you’ll likely hear “The City on the Edge of Forever” mentioned several times. The romantic yarn, which closed the first season, finds the crew of the Enterprise in a time-traveling misadventure. Dr. McCoy, less than lucid after an accidental overdose of medication, charges through a temporal gateway into New York City circa 1930. Kirk and Spock follow their ailing comrade and discover that McCoy has inadvertently altered history with serious consequences. Our heroes manage to put things right, but not without considerable anguish on Kirk’s part.

Ford’s 1929 Model AA stake body truck, similar to one seen in “The City on the Edge of Forever.” (THF28278)

The episode features several period automobiles including a 1930 Buick, 1928 and 1930 Chevrolets, and a circa 1930 Ford Model AA truck. Most are in the background, but a 1939 GMC AC-series truck plays a crucial part in the story. In fact, it’s not too much to say that the whole plot depends on it. (Beware of the spoiler at this link.) No, a ’39 truck has no business being on the streets of New York in 1930, but we’ll just let that slide.

The crew returns to a circa 1930 setting in the memorable season two episode “A Piece of the Action.” But this time they’re not on Earth. The Enterprise arrives at the planet Sigma Iotia II, last visited by outsiders before implementation of the Federation’s sacrosanct Prime Directive – barring any interference with the natural development of alien cultures. Kirk and company discover that the planet was indeed contaminated by those earlier visitors. They left behind a book on Chicago gangsters in the 1920s, and the Iotians – a society of mimics – have modeled their planet on that tome, with the expected chaotic results.

Cadillac, the choice of discerning Starfleet officers. (THF103936)

Those industrious Iotians somehow managed to replicate a host of 1920s and 1930s American cars. Look for a 1929 Buick, a 1932 Cadillac V-16, and a 1925 Studebaker in the mix. But the star car undoubtedly is the 1931 Cadillac V-12 used by Kirk and Spock. It’s one of the few times you’ll see Kirk drive, and it makes for one of the episode’s more amusing scenes. Give one point to Spock for knowing about clutch pedals, but take one point away for his referring to the Caddy as a “flivver.” One could quibble with ’30s cars appearing in a ’20s setting – but one should also remember that this isn’t Earth. We can’t expect the Iotians to get all the details right!

It’s also worth taking a look at season two’s final episode, “Assignment: Earth.” The Enterprise travels back in time to 1968 to conduct a little historical research on Earth. They cross paths with the mysterious Gary Seven, an interstellar agent on a mission of his own to prevent the launch of an orbiting missile platform that will – apparently – lead to nuclear war. It sounds like something right out of “Star Wars.” (No, not that Star Wars, this “Star Wars.”)

Based on the Department of Defense cars seen in “Assignment: Earth,” it seems the Pentagon prefers Plymouths. Now why could that be? (THF150740)

It’s all very complicated, but it provides another opportunity to see some vintage wheels. (Well, vintage to us and to the Enterprise crew. To TV audiences in 1968, these were contemporary cars.) Pay attention and you’ll spot a number of government agency vehicles including a 1963 Plymouth Savoy, a 1967 Dodge Coronet, and a 1968 Plymouth Satellite (the latter being particularly apropos for a space series). For those who aren’t Mopar fans, look quickly and you’ll also spy a 1966 Ford Falcon in the episode.

Okay, so no one will ever confuse Star Trek with Top Gear. But, if you keep your eyes peeled, every now and then you’ll find a little gasoline to go along with all of that dilithium. After all, sometimes the boldest way to go is the oldest way to go.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

by Matt Anderson, cars, popular culture, TV, space, Star Trek

In the 1950s, big cars ruled. Even low-priced cars like Plymouths, Chevrolets, and Fords were good-sized. The Nash Rambler was smaller and cheaper, with similar interior room. 1950 Nash Rambler Convertible THF90351

1950 Nash Rambler Convertible THF90351

Smallness was not attractive in itself, so Nash -- which competed for the same narrow slice of the market with small cars like the Crosley, the Willys, the Hudson Jet, and Kaiser’s Henry J -- pitched the Rambler as a small car that seemed big.

1950 Nash Sales Brochure, "The Smartest, Safest Convertible in the World" THF84551

1950 Nash Sales Brochure, "The Smartest, Safest Convertible in the World" THF84551

Nash tried to make the Rambler appeal to everyone by giving it a little bit of everything—even seemingly contradictory things: economy and luxury, convertible and hardtop, small enough to park and big enough to seat five, as safe as a sedan and as sexy as a sports car.

THF84553

But if big was so appealing, why build small cars at all? The sales figures added up to one answer—don’t. There simply weren’t enough buyers, and all the tiny cars failed.

From the staff at The Henry Ford.

Thanks to some digging into our collections, Chicago-based writer and editor James Hughes, son of director John Hughes, discovered some surprising connections between National Lampoon’s Vacation, which his father wrote, and The Henry Ford. In 2017, James joined Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson for a discussion about that connection, his father’s writing inspiration, and the time-honored tradition of the family road trip, both then and now.

Matt Anderson: James, of course it should be noted that your father wrote the screenplay for this picture, and here we are. And, of course when think about your father's films, whether it's Sixteen Candles, Pretty in Pink, Weird Science, right up to Uncle Buck, we tend to think of Chicago. The films are always rooted in that city or that area. But in fact, he's got some connections to southeast Michigan.

James Hughes: My father was born in Michigan in 1950, in Lansing, and spent his childhood in Grosse Pointe. It was probably around junior high age, I want to say around 12, possibly older, when his family moved to the North Shore of Chicago, to the suburb of Northbrook, which became the inspiration for the fictional town of Shermer, Illinois, where my father set many of his films, particularly in the ‘80s. I was thinking about this relation to Vacation—there are several Michigan connections. For one, Vacation was a summer movie, released in 1983. Within a few weeks of it, Mr. Mom was released as well, another screenplay he wrote, which was set in suburban Detroit. The Michael Keaton character, at the beginning of the movie, is fired from his job at Ford Motor Company. But before there was the screenplay for Vacation, there was my father’s short story, titled Vacation ’58. The Griswold family lived on Rivard Boulevard in Grosse Pointe. So, that was where the journey began.

You know, it's interesting, I've said this many times about my dad. He took a pretty significant step back from the movie business in the late '90s and early 2000s. But he continued to write every day. He was a very disciplined writer. And in his later years, before he passed away, he was working on developing his prose style. He was writing hundreds and hundreds of short stories. And there was an interesting series of stories within that about his Grosse Pointe childhood. He made himself the narrator, in much the same way that the Vacation short story was from the point of view of Rusty, the son. To tell his own stories, he created a character based on himself and wrote under the pseudonym JL Hudson, as a nod to the Detroit department store, in much the same way that the Griswold family is a nod to Griswold Street in downtown Detroit.

Matt: Your father, in the early-mid 1970s, he's working at an ad agency, right? For Leo Burnett in Chicago? Really one of the best-known ad agencies in the world, at that point. And he's got a successful career, but as I understand it, he also has kind of a shadow career. He's moonlighting on the side, right?

James: All throughout the ‘70s my father was a freelance humor writer. He got his start at a relatively young age. He was in his 20s, maybe, I want to say 22. And he was writing jokes for stand-up comedians. Rodney Dangerfield was one, Phyllis Diller was another. He would maybe write 10, 20 jokes a day and mail them off to comedians, and would get paid per joke, if that line was used in their acts. He was able to roll that into writing for publications. At the time, in the mid-70s, Chicago had a deeper publishing footprint than it has now. And the big magazine was Playboy, so he wrote a few humor pieces for Playboy, and conducted an interview or two for them as well. Concurrently, he was a copywriter and, ultimately, a creative director at Leo Burnett.

The big prize was to write for National Lampoon, which was, to him, the preeminent comedic voice in the country. He was really honored to contribute to the Lampoon. And he was able to pull this off in part because he often commuted from Chicago to New York. In particular, he was servicing the Virginia Slims campaign for Phillip Morris, which was based in Manhattan. So, either before or after meetings, he was able to sneak off to the National Lampoon offices, which were also in the epicenter of the New York advertising row, on Madison Avenue.

It's common for advertising writers to, say, work on their novel at night, or work freelance on the side. My father actually wrote at work quite often, at his desk. And his boss, Robert Nolan, allowed it because he wanted to keep him working on ad copy. Rob wrote an interesting piece for the Huffington Post soon after my father died, in 2009, where he recounted what it was like to be John Hughes' boss, knowing he was living this sort of double-life as a comedy writer. He likened it to a kind of Ferris Bueller/Principal Rooney dynamic, where my father was always able to stay one step ahead, and somehow get all of his work done, and somehow get to work on time, while also contributing steadily to the Lampoon, where he eventually earned a spot as an editor on the masthead, all while living in the North Shore of Chicago and skirting a move to New York.

Matt: Fantastic. Well, let's talk about that short story, Vacation ‘58. This is a real defining moment. Sort of a milestone in your father's career, right? He makes this decision now to move away from Leo Burnett and commit himself to writing full time.

James: This story was published in September 1979, which was about six months or so after I was born. So he was a young father of two and had all the commitments that come with that. But he enjoyed writing and contributing to the Lampoon so much that he took the risk and quit his job at Leo Burnett. He was on the verge of becoming a VP, though he quit to pursue writing full-time. Fortunately, for him, the release of National Lampoon’s Animal House in 1978 was such a smash that several Lampoon writers were being poached by the studios or offered development deals. And without my father even knowing, his short story was optioned by Warner Bros., pretty much upon publication. And though he had to work in the trenches on several projects between, let's say 1979 and 1983, when Vacation was released, it really did help launch his career.

Matt: Let's talk for a moment about the short story. The movie is a fairly faithful adaptation, going from that short story. But there are a few changes here and there, and one of the major changes, in fact, was quite a big change to the ending. And I should, just to do it justice, read the opening line:

"If Dad hadn't shot Walt Disney in the leg it would have been our best vacation ever."

I think that pretty much sets up the story beautifully. But that gets to the ending, which is quite different from what we see in the film.

James: Of course with the film, they weren't able to have Walt Disney portray himself—that might've been a bridge too far. The Roy Walley character was created for the purpose of the film. And yes, the ending of the short story is pretty rough, as much of the humor in the Lampoon was back then. Clark uses live rounds, it’s not a…

Matt: Not a BB gun?

James: No, not a BB gun. But when Clark arrives at the park, only to find that it's closed for repairs, he snaps and takes the family to the Bel Air home of Walt Disney and shoots Walt in the leg. Walt’s security dog doesn’t fare well, either.

Matt: Just the happy ending everyone wants. My understanding is they originally shot something like that for the film, and then realized it didn't play all that well with the test audiences.

James: True, yes. You know, perhaps because of my father’s advertising background, he was open to the test-screening process—the kind of diagnostics you learn from test audiences, and how you can adjust the picture accordingly. Of course, he wasn't the director of the film, but he was, as a result of the rather rough ending, which audiences rejected, brought back in to write an entirely new ending at the request of Harold Ramis, the director.

Matt: Speaking of that, when you think about your father's films, really starting in the mid-80s and on—films like Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and Ferris Bueller's Day Off—these are movies where you really see a large degree of creative control. He's writing the story, then directing, very much able to bring his vision to the screen. And that's not the case, of course, early in his career. He's written the screenplay for Vacation and adapted it from his short story, but he's turned over control, at some point, to Harold Ramis. And I wonder if you had any insight on that experience. If that was difficult for him?

James: I think the process of changing the ending, that might've been an area of difficulty. As a young writer for hire, he didn’t have much power in the industry. But I think time has certainly proven that Harold was a great choice to direct this picture. And casting is such a big part of the process, and I know my father was pleased with the cast that Harold and his team put together. I know they worked closely, but in terms of being on set, I don't believe he was there very much. Obviously with it being a road picture, the majority of which was filmed in Colorado and out west, I don't believe he was actually physically present for much of it. Though, I would imagine, because of that triage situation with the ending, he was brought closer into the fold.

Matt: This leads me to my next question, of talking about the road picture. From what I understand, it was more or less like a vacation for the cast. They were traveling to these places. The whole crew and support trucks, depending on the outfit. But, I was curious about your own family vacations. Did you take trips with your father, your parents? Have you had any wacky adventures or stories to share?

James: I was raised in Illinois, but my father's career demanded we move out west, to Los Angeles, from the mid- to late 80s. So much of my childhood was about alternating between Illinois and California. We kept our house in Illinois and went back often, so that meant a lot of air travel. I don't have any major road-trip stories to offer, unfortunately. As I grew older, we did travel by car with my grandparents to the Northwoods. My father, to some extent, rolled some of those experiences into his screenplay for The Great Outdoors, along with his own memories of traveling and exploring the Upper Midwest when he was younger. Or perhaps it was just him longing to revisit that corner of the world after being stationed in Los Angeles for years.

In 1990, when Home Alone was released, it was really the first time his work went truly international. He generally wrote stories that catered to a domestic audience. These were regional stories, particularly about the Midwest. And Home Alone changed the whole paradigm. That franchise played so widely overseas, which meant an obligation to do foreign press and promote the franchise around the world. And then he had a couple productions based in London, which meant going to England quite often. In a way, in the '90s, he made up for lost time. He was simply too busy for us to do any extensive road trips like the one in Vacation. But later in life, he made up for it, particularly by trying to open the world to the family a bit more, with overseas travel.

Model with 1979 Ford Country Squire Station Wagon. THF294571

Matt: Being an automotive curator, we've got to talk about that car. It’s more or less based on a 1979 Ford Country Squire station wagon, and just made up to look as gaudy as possible. You know, why do four headlights when you can do eight, right? I wondered if your father had any input on the design?

James: You know, I can't say for sure if he did. I would imagine, when you go from the page to the screen, there are so many different people making decisions—the art director, production designer, prop master, the director himself—that I don't know if, as a screenwriter, he was able to have input on the model that they chose and customized. I do know that from the short story, it's a Plymouth.

Matt: Right, a '58 Plymouth.

James: A running joke early on in the short story is how long it takes for the Griswold family to actually leave the house, or even just leave the state of Michigan. And one of the reasons is that the Plymouth dies. And Clark laments and kind of kicks himself for the fact that he didn't buy a Ford.

Matt: Right. There you go!

James: In the early '90s my father was working at 20th Century Fox. At that time, one of the hit shows on the Fox network was Married With Children. I remember my dad mentioning, offhandedly, that the opening shots of that show’s title sequence were from Harold's second unit photography on Vacation. That always stuck in my mind, and I never quite knew if it was true. I've seen that noted online here and there, but I wanted to confirm it before mentioning it here. I asked my friend Schawn Belston, head of archival and digital restoration at Fox, if he would ask around the lot on my behalf. Fortunately, there were some people who confirmed that, in fact, yes, Married With Children opens with the footage from Vacation. There was a very kind film stock librarian at Fox, Wendy Carter, who went so far as to track down Carl Barth, the aerial photographer who shot the Family Truckster driving through Chicago, to verify. It was noted that, if you look carefully at the title sequence for the show’s first three seasons, you can see the Family Truckster drive by. I believe it's on the Dan Ryan Expressway. A strange pop-culture afterlife for the Truckster.

Matt: I think they built maybe a total of five cars for the movie. I'm sure there was a hero car that was fully tricked-out, and then of course they had some stunt cars for the jump and so forth. But it's beloved. It's always interested me. I think if this film had been made even just a year or two later, they probably would've been driving a minivan, because this is the tail-end of the station wagon era.

James: That's true.

Matt: Vacation is essentially your father's big break, right? This is one of his first screenplays, and it's a hit film. There's no two ways about it. I would imagine, from that perspective, if nothing else, it would have a certain meaningfulness to him. But also, as you watch the movie, you notice that two of your father's future collaborators, Anthony Michael Hall and John Candy, both appear in this movie as well. I wondered if that's perhaps how he first crossed paths with them?

James: I believe that's the case. I'm glad you mentioned that. I appreciate that, because those are two actors, certainly John Candy, who my father cherished collaborating with. I don't think there are any two actors he gave more latitude to improvise or to develop characters alongside him when he was directing than Candy and Michael Hall. Another actor he admired was Eddie Bracken.

Matt: Yes, Roy Walley.

James: Eddie Bracken was cast to play Roy Walley, and I imagine it must've blown my father's mind at the time. He was a big fan of Preston Sturges, one of the great writer/directors of the 1940s, perhaps best remembered for Sullivan's Travels, which was one of my father's favorite movies. Bracken was the star of two of Sturges' greats, Hail the Conquering Hero and The Miracle of Morgan's Creek. It had to be a trip for him to have Bracken reading his dialogue. And he actually circled back later in his career and hired Eddie a couple of times more. Perhaps most prominently in Home Alone 2, when he was the toy-store owner in New York.

Matt: They talk about actors and roles they were born to play. I've always thought that about Eddie Bracken in this movie, you know, just the perfect sort of spitting image of Walt Disney. A great stand-in. There's some other, of course, perfect performances in this movie. Think about Randy Quaid as Cousin Eddie. Sort of steals every scene he's in. Imogene Coca, of course, a legend in TV comedy from Your Show of Shows. Brian Doyle-Murray, who plays the campground owner. Slight continuity error here because he returns in Christmas Vacation as Clark's boss, but we'll let that go for now. But I wondered, as we watch this movie, it's full of so many wonderful moments. I wondered if you had any favorite scenes or moments in this movie that you've continually referred to.

James: I'm partial to Clark's meltdown when the family throws in the towel and declares they're ready to head home. I think my father had a particular knack for writing passive-aggressive rants.

Matt: There's so many great moments in this movie. I kind of think of it as America's favorite R-rated family film. It's just so timeless. You think of the short story being written about a trip in 1958, this movie made in 1983, yet the situations are still recognizable to all of us today, taking a road trip in 2017.

Part of the reason we’re chatting is because there is a surprising connection between this movie and The Henry Ford. The collections in The Henry Ford, specifically. We see it right away in the opening title sequence of Vacation. Tell us a little bit about that.

Trout Haven Billboard, Spearfish, South Dakota, 1980. THF239534

James: I was thrilled about this. I was here at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation last year and our friend and colleague Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication and Information Technology, gave me a private tour of the archive. At that time, a recent acquisition was a portion of the photo archives of John Margolies, a great chronicler of Americana, particularly roadside Americana. He documented the kinds of landmarks that are spoofed in Vacation. You know how Clark wants to see the world's second-largest ball of twine? Well, Margolies was the photographer who would've had an entire portfolio of that. That name stuck in my mind when Kristen first told me about him. Then, a few months later, I came across an interview with Harold Ramis where he mentioned he was friends with Margolies and that he used his images for the postcards in the main and closing title sequences in Vacation. I told Kristen about this and she searched the Margolies archives and found several images that appear in Vacation.

This inspired me to reach out to the title designer, Wayne Fitzgerald, who’s a giant in his field. He’s retired now and lives in the Pacific Northwest. He created the titles for My Fair Lady, Judgment at Nuremberg, Bonnie and Clyde. The titles for the Netflix series Stranger Things are patterned after Wayne's titles for The Dead Zone, which was released a few months after Vacation. He and his son and collaborator, Eric, also worked on the titles for The Breakfast Club and filmed the shot where the title card with the David Bowie quote shatters at the start.

I had a great conversation with Eric, about what it was like putting the Vacation titles together, back when they were cutting to Lindsey Buckingham’s “Holiday Road” demo tape, which Eric remembered having no lyrics yet, only melodies. At one point, Buckingham riffed on Wayne’s name, to fill space during the verses.

Hat N' Boots Gas, Seattle, Washington, 1980. THF238979

I mentioned the Margolies archive to Eric, who of course remembered his images. What The Henry Ford has in the collection is even more special than what’s in the movie, because you have the slides themselves, John’s original photography. The titles for Vacation were made in the pre-digital era, so they were reproductions that were taken from books, as Eric explained, and then shot as animation cels. Many of them were Margolies’ images, which were doctored by Fitzgerald and his crew to appear as if they were postcards—given captions or a certain trim or border. Wayne and Eric were pleased to hear about this connection to the Margolies archives.

It’s great that Margolies, all these years ago, captured an America that was vanishing. Here we have a movie that's already over 30 years old. So fortunately, some of Margolies’ images live on, not only in the movie on a mass scale, but in the permanent archives of the museum. I think it's this really wonderful connection, and I'm thrilled that it's brought us to this discussion.

Matt: Those are two things we love here: highway travel and roadside Americana. You get both of them in the Margolies collection. James, thanks for chatting with me.

James: I'm happy to be here, thank you.

1980s, 1970s, Illinois, Michigan, 20th century, 21st century, 2010s, travel, roads and road trips, popular culture, movies, John Margolies, cars

The Walking Office

The Walking Office Wearable Computer is a visual prototype model that was created by the collaborative design group Salotto Dinamico in the mid-1980s. Salotto Dinamico, which translates to “dynamically, we grow,” was composed of Vincenzo Iavicoli, Paolo Bettini, Maria Luisa Rossi, Maurizio Pettini, and Letizia Schettini. Image of poster advertising Salotta Dinamico’s “The Walking Office” THF291245

Image of poster advertising Salotta Dinamico’s “The Walking Office” THF291245

While all five members of the group had input in the project, Vincenzo Iavicoli submitted the concept as his 1983 undergraduate Industrial Design thesis at the ISIA school in Florence, Italy (under the guidance of his mentor, Paolo Bettini). The designers entered a physical model of the ideas in Iavicoli’s thesis in the 1985 Mainichi International Industrial Design Competition in Tokyo, Japan. The Walking Office won the top prize in the “Harmonization of Office Automation and Environment” category, attracting global attention in design, fashion, and technology publications. It was featured on the covers of Domus, ID, and Interni magazines, and received coverage in Brutus, Vogue, and approximately 70 other publications. The success of the project sparked the careers of the youngest members of the group, Iavicoli and Rossi, who formed their own successful design consultancy and became educators in Industrial Design programs around the world.

Designers Vincenzo Iavicoli and Maria Luisa Rossi at the 1985 Mainichi International Industrial Design Competition THF274743

The Walking Office model is made of polished chrome. Two pieces fit together to form a keyboard, the display arch fits into the keyboard to serve as a display, and a cassette recorder links up with an acoustic coupler modem to record and transmit data through any available telephone line. The Walking Office also doubles as personal adornment, with the keyboard pieces worn on the shoulder and the display arch as a headpiece (looking much like a mohawk). It combines the expressive aesthetic detail of 1980s Italian design with provocative high-tech materials to create an unapologetically cyberpunk-chic device. The Walking Office was not meant to be concealed (comparisons might be drawn between it and the Google Glass Explorer program of recent years), and its seductive styling was quite revolutionary in 1984. In a 2016 interview, Iavicoli recalled that though Japanese designers adeptly diffused new technologies into the mainstream, they had not yet begun to focus consistently on styling their devices. Early in the prototyping process, Iavicoli decided not to try to compete with the fast pace of technology, prioritizing strategy and concept instead.

Model wearing “The Walking Office” prototype THF274747

Iavicoli’s thesis explored the design-thinking process behind the prototype: the history of physical office spaces (desks, lighting, cubicles, seating), the technology utilized within them (computers, calculators, modems, keyboards, online systems), and intangible aspects such as the psychology of work environments and spatial arrangements.

Page from Vincenzo Iavicoli’s undergraduate thesis THF275237

The designers of the Walking Office explored negative and positive elements of its proposed function. On one hand, they described it as “an Orwellian omen condemning portable work” (anticipating the desire of today’s knowledge workers to “unplug” themselves from the distractions of always-on technology.) A more positive spin situated the Walking Office as a route to freedom that would allow people to embrace the “amoral and amusing” aspects of creative work. They imagined “electronic machines…coming out of the office, conquering urban space, dwellings, golf courses, bars and beaches, becoming natural body accessories.”

Drawing imagining “The Walking Office” in use THF274752

The Walking Office was pitched as a “techno-human” object. As a modern prosthetic, it subverted where (and when) the office could be, essentially turning the human body into a mobile workstation. It proposed the same type of fluid interactions with technology as one would have with pens, watches, and eyeglasses. And finally, it provided an alternative method of accessing and using information in an efficient way.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications and Information Technology.

20th century, 1980s, Europe, technology, portability, design, computers, by Kristen Gallerneaux

Remembering Damon J. Keith

Today, The Henry Ford mourns the passing of Damon J. Keith, a civil rights icon and courageous champion for social justice. Judge Keith was the driving force in high impact cases which shaped our local community, our country and our collective national conscience. He was a leader, scholar, beloved mentor and dear friend of many, including The Henry Ford. During his visits to our campus, he took particular delight that among the automotive, aviation, power generation and agricultural exhibits presented on the floor of the museum, a visitor could also experience our With Liberty and Justice for All exhibition which presents the story of America’s historical and ongoing struggle to live up to the ideal articulated in the preamble of the Declaration of Independence.

We were also honored to host Judge Keith as our honored guest in 2011 when The Henry Ford had the rare privilege of putting the original Emancipation Proclamation on public display. We wanted to preserve some of the special moments and memories the event generated in over 21,000 visitors who viewed the document during its 36-hour public presentation via a limited printing, non-commercial commemorative keepsake book, and we were honored to include Judge Keith’s reflections on the document’s significance as the book’s close.

Judge Keith’s passing is a true loss for Detroit, Michigan, and our nation, but his inspirational and unwavering commitment to justice and civil rights will be his living legacy.

21st century, 20th century, Michigan, in memoriam, Detroit, Civil Rights, African American history

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1950s

Henry Ford’s energy had been the animating force behind the Edison Institute. His death in 1947 challenged the institution to manage a collection that had grown to massive proportions – with no adequate storage solutions and no formal cataloging system.

Aerial View of Henry Ford Museum, circa 1953. THF112188

Clara Ford took over for her husband after his death, and the skeletal staff maintained the status quo at the Institute for the next few years without real direction. In 1950, the death of Clara signaled the end of another era. The Ford family stepped away from the daily management of the institution and began a strong tradition of lay leadership. In the early 1950s, all three of the Fords’ grandsons served on the Board of Trustees. William Clay Ford took over the position of board president in 1951 and remained chairman of the board for 38 years. Museum Executives and "Today" Show Staff after Live Broadcast from Greenfield Village, October 25, 1955. THF116184

Museum Executives and "Today" Show Staff after Live Broadcast from Greenfield Village, October 25, 1955. THF116184

In January 1951, the board appointed A.K. Mills to the new post of executive director of Greenfield Village and the Edison Institute Museum. He implemented business practices and hired professional staff members. During the 1950s, the public – especially the vast traveling public – became the focus of the institution’s attention. In 1952, as a tribute to its founder, the Edison Institute was renamed Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. Mills died suddenly in 1954; Donald Shelley replaced him as executive director, a position he held for the next 22 years. Industrial Progress U.S.A. Exhibit, Henry Ford Museum, 1952-1954. THF112172

Industrial Progress U.S.A. Exhibit, Henry Ford Museum, 1952-1954. THF112172

Traveling exhibits, developed by the institution in the 1950s, offered the museum a chance to promote itself beyond the local area, increase awareness, and increase visitation. Henry Ford Museum’s attendance steadily climbed each year. The number of visitors doubled over the decade, from 500,000 in 1950, to 1 million by 1960. The village and museum had become a national attraction.

Acquisitions to the Collections: 1950s

Walking Doll

In the 1950s, the museum’s curators acquired many objects for the collection through a network of antique collectors and dealers. Curators were especially looking for folk art and other “early American” objects. Collector Titus Geesey of Wilmington, Delaware had filled his home with three decades worth of collecting. Ready to pare down a bit, Geesey sold over 300 objects to the museum over the years, including prints, tableware, coverlets, a weathervane, and toys. This late 19th-century mechanical doll from Geesey’s collection came in 1958. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Moravian Bowl with Stylized Fish and Turtles in Center, 1810-1820

In the mid-20th century, Henry Ford Museum built on its early holdings to become one of the preeminent collections of American decorative and folk arts. This ceramic serving bowl was made by Moravian-German immigrants in Alamance County, North Carolina. The playfully arranged turtles and fish are unique representations in Moravian ceramics, which usually emphasizes abstract decoration. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

1941 Allegheny Steam Locomotive

It's perhaps the most photographed object in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, and certainly among the best-remembered by our visitors. The mighty Allegheny has anchored the museum's railroad collection since 1956. Used steam locomotives were a dime a dozen in those days as railroads switched to diesel-electric power. Some went to museums and some to tourist railroads. But many more went to city parks and county fairgrounds, left to the mercies of the weather. The Allegheny is a gem carefully preserved indoors for more than 60 years now -- four times longer than it actually operated on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

"Battle Scenes of the Rebellion" Battle of Gettysburg, Civil War Panorama"

In the 1880s, Thomas Clarkson Gordon (1841-1922), a self-taught artist and Civil War veteran, created a panorama depicting scenes from the Civil War. Gordon toured his 15-paneled panorama throughout eastern Indiana, retelling the history of the conflict through his vivid illustrations. In 1956, Thomas Gordon's daughters wrote to Henry Ford II, hoping he would want the panorama for his grandfather's "Dearborn Museum." The request was redirected to the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. The donation arrived in 1958. - Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Birth and Baptismal Certificate for Maria Heimbach, 1784|

German immigrants in Pennsylvania created fraktur – highly-decorated documents – to commemorate life’s most significant events. This particular fraktur is a Geburts-und Taufscheine – or a birth and baptismal certificate – and is the most common type. The name fraktur is rooted in a German calligraphic tradition and was primarily used for official documents. The Pennsylvania German frakturs continue this typographic tradition but expand upon it to create a new cultural tradition for a new homeland. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

1953 Ford X-100 Concept Car

During its 50th anniversary in 1953, Ford Motor Company celebrated the past and looked to the future. A. K. Mills -- former head of Public and Employee Relations and recently-appointed Executive Director of the newly-renamed Henry Ford Museum -- managed multiple anniversary projects. While Mills organized new exhibits, oral histories, books, films, and -- most importantly -- a company archive, Ford engineers completed a special project of their own. Their fully-functional concept car, known as the X-100, was showcased during anniversary celebrations and featured more than 50 futuristic innovations, including heated seats and a telephone. - Ryan Jelso, Associate Curator

Print of Mary Vaux Walcott Wildflower Sketch, "Trumpet Honeysuckle," 1925

Clara Ford was an active gardener who presided over several gardening organizations during her lifetime. Citing her interest in flowers, the William Edwin Rudge Printing House of New York sent Mrs. Ford a set of prints originally illustrated by Mary Vaux Walcott in 1925. (The gift also served to demonstrate the quality of the firm’s color reproductions.) When Clara Ford died in 1950, a group of items from her estate – including these prints – came into the museum’s collection. - Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

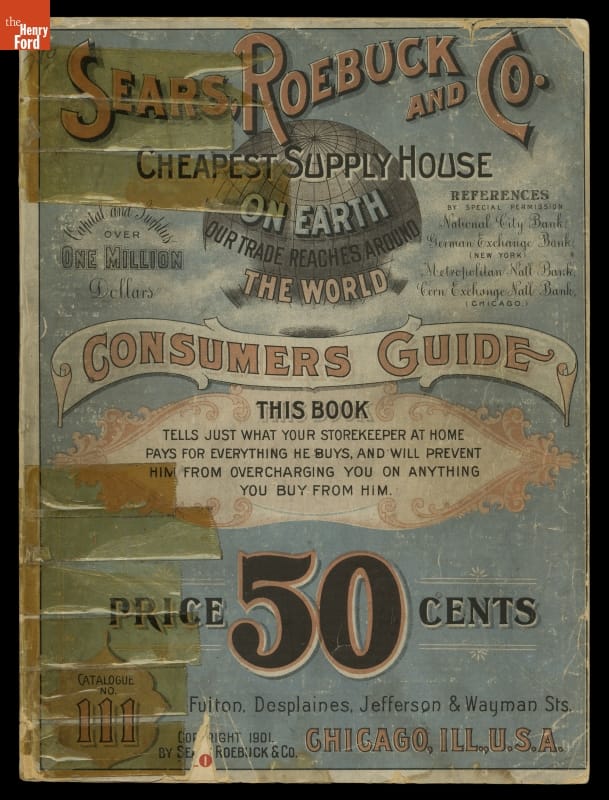

Sears, Roebuck and Company Mail-Order Catalog, "Consumers Guide, 1901," Catalogue No. 111

Mail order catalogs opened up the world of retail to families around the country. With thousands of items right at their fingertips this Sears and Roebuck catalog would give access to clothing, equipment, home goods, and everything in between to anyone in the United States. The Benson Ford Research Center now utilizes trade catalogs like this to document fashion and innovation of the time. - Sarah Andrus, Librarian

H.J. Heinz Company Collection

Expansion at the H.J. Heinz Company in Pittsburgh during the early 1950s looked to be the end for “The Little House Where We Began,” the small brick building where H.J. Heinz began his business and that had been moved by barge to Pittsburgh in 1904. To save it from demolition, the H.J. Heinz Company donated the building to the Edison Institute, where it was reconstructed in Greenfield Village as the Heinz House. Along with the building, the H.J. Heinz Company donated this sizable archival collection that includes photographs, advertising layouts, publications, scrapbooks, and business records, all of which help convey the history of the Heinz House, the H.J. Heinz Company, and other stories of innovation and entrepreneurship. - Brian Wilson, Senior Manager, Archives and Library

Ford-Ferguson Model 9N Tractor, 1940

The Ford Motor Company re-entered the tractor business in the United States in 1939 with the 9N, a Ford tractor with a 3-point hydraulic hitch-and-lift system invented by Harry Ferguson. After Edsel and Henry both died, Henry Ford II ended the Ford-Ferguson arrangement and released a new model, the 8N, marketed through the Dearborn Motor Corporation, not through Ferguson. Ferguson sued, and after four years he accepted $9.25 million paid by FMC to settle the patent-infringement case. This tractor was one of eight that FMC assembled for the litigation and then transferred to the Edison Institute to complete its display of Ford tractors. - Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Robert Propst: Unorthodox Thinker

Portraits of Robert Propst. THF137271

Portraits of Robert Propst. THF137271

PROFESSION: Designer (Although he preferred to be called "searcher")

INNOVATION: The Action Office II System (1968) and the movable "coherent structures” of the Co/Struc System designed for hospitals (1971)

ATTRIBUTES: Empathetic observer, serial problem solver, unorthodox thinker

You could be forgiven if you aren’t familiar with the work of Robert Propst. After all, if his designs were working as he intended, they simply disappeared.

Propst became director of the Herman Miller Research Division (HMRD) in 1960, setting up shop in a small concrete building in Ann Arbor, Mich. The founder of Herman Miller, D.J. DePree, saw potential in Propst’s ambitious thinking and hired him to broaden the company’s product range. Very few guidelines were in place at HMRD: Nothing should be connected to military use, no furniture designs — and whatever was designed should simply “be useful.” Robert Propst Outside Herman Miller Research Division Office, Ann Arbor, Michigan, July 1964. THF137214

Robert Propst Outside Herman Miller Research Division Office, Ann Arbor, Michigan, July 1964. THF137214

Deliberately choosing a building more than 150 miles away from Herman Miller’s headquarters in Zeeland, Mich., Propst exercised his freedom to research without the distraction of corporate meetings. For every idea he had that went into production, hundreds more were filed away.

Two of Propst’s most impactful projects were holistic environments designed for high-impact workplaces: the improved Action Office II system (1968) and the movable “coherent structures” of the Co/Struc system designed for hospitals (1971).

In Propst’s mind, offices had become chaotic wastelands. Cobbled together furniture, nonergonomic chairs and an invasion of technology onto ad hoc surfaces. Action Office — a modular system of free standing panel walls — could be fluidly arranged into nooks for working, conference areas and other purpose-driven needs. An idealistic vision for the birth of the modern office cubicle.

Propst wasn’t always a designer of “things” but of situations. He attacked issues from the reverse, finding clues in the algorithms of human behavior working in high-stakes spaces. How did people move while working? Where was time being spent? Wasted? How can we support safety? Privacy? Collaboration? The physical solutions he engineered encouraged ideas of access, mobility and efficiency. His modular approach to office landscapes was intended to have a 1 + 1 = 3 effect. Which is to say that by implementing physical change, “knowledge” workers could then springboard off an improved relationship with their workspaces, which were suddenly more hospitable to launching new ideas, productive workflows and transformative projects. Action Office Project Drawing by Robert Propst, April 6, 1964. THF241708

Action Office Project Drawing by Robert Propst, April 6, 1964. THF241708

Did You Know

- The proliferation of the office cubicle is almost single-handedly due to the introduction of the Action Office II system in 1968. Unfortunately, the mobile aspect of Action Office became rooted to the floor, quite literally. Large businesses filled their buildings with Action Office (or its various knock-offs) to create Dilbertesque “cubicle farms.”

- The first version of Action Office was conceived by Robert Propst and designed by George Nelson in 1964, but sales were lackluster. Corporate managers worried about the porous borders being offered to their staff, now called “knowledge workers,” and the cost was simply too high. Propst returned to the drawing board alone for AO2.

- Robert Propst did not like to be referred to as a designer. He also didn’t like the term “researcher,” because it implied looking backward. His ideal description for his activities was “searcher.”

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from an article in the January-May 2019 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Herman Miller, The Henry Ford Magazine, by Kristen Gallerneaux, Robert Propst, furnishings, design

The Tale of the Nauga’s Hide

Naugahyde Advertisement in Life Magazine, October-December 1967. This image is not an original photograph and is a combination of two images created for illustrative proposes.

The Nauga, a colorful, horned, happy-looking creature native to the island of Sumatra, was once hunted to near-extinction. They were hunted for sport, but more often for their smooth and durable leather-like hide – Naugahyde, as it’s generally known. However, hunting a Nauga for its hide is quite unnecessary -- they painlessly shed their hide at least once each year for use in furniture, clothing, and more.

Wait a minute.

You’ve never heard of the Nauga?

All right, you’ve got me. The Nauga is a fictional creature. It was an advertising gimmick created to help Uniroyal Engineered Products promote their soft vinyl-coated fabric that feels like leather but is more durable. The product, Naugahyde, was used primarily as upholstery in the furniture industry, but also was used for clothing, shoes, accessories and other home goods. Its success spawned many imitators. In the mid-1960s, Uniroyal hired legendary ad-man George Lois and designer Kurt Weihs to craft an advertising campaign to differentiate their product from the competition. And what did Lois and Weihs create? The Nauga.

A humorous ad campaign featured the Nauga engaged with the world – as the life of the party, as a child’s play companion, adorned in splattered paint from a craft went awry, even as a vacationer readying for travel with golf clubs in hand. These advertisements emphasized the suitability of Naugahyde upholstery for all areas of life, claiming it could be indistinguishable from other fabrics like leather, tweed, or silk -- but “last about ten times as long.” An image of the Nauga found its way onto hang-tags that accompanied all genuine Naugahyde products. Many of the ad campaigns ended with this directive: “If you can’t find the Nauga, find another store.”

Naugahyde advertisement in Life Magazine, July-September 1967.

The advertising worked – at least in that it caused excitement over the mysterious Nauga creature. Allegedly, some people even believed Naugas were real creatures and became concerned about inhumane treatment as the use of Naugahyde boomed in the late 1960s. A New York comic, Al Rosenberg, invented a fictional character named Earl C. Watkins who spearheaded the “Save the Nauga” project to protect the species from extinction, adding that a “herd of Naugas is often mistaken for a roomful of furniture.'' The Nauga even made an appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Nauga dolls, like this one in The Henry Ford’s collection, were also produced to promote the brand. In fact, if you visit the Naugahyde website today, you can still “Adopt a Nauga,” which, according to the company’s webpage, are bred on a ranch outside Uniroyal’s headquarters in Stoughton, Wisconsin.

Uniroyal "Nauga" Toy, 1955-1975

It isn’t unusual for companies to go to great lengths to endear a product to the public. These efforts have often yielded highly creative and memorable results, like Oscar Mayer’s Wienermobile, the Heinz pickle charms and pins, or the Pets.com Sock Puppet, to name a few. While the Nauga creature has faded nearly into obscurity, the leather-like product it represents lives on…perhaps even as the upholstery of the chair you’re currently sitting on.

Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford, recently adopted a Nauga doll of her very own.

toys and games, by Katherine White, advertising, furnishings