Posts Tagged by jeanine head miller

Quinceañera: A Rite of Passage

A 15th birthday is very special for many young women in Hispanic culture. Quinceañera, Spanish for “15 years,” marks her passage from girlhood to womanhood. Both a religious and a social event, quinceañera emphasizes the importance of family and community in the life of a young woman.

Invitation to Detroiter Maritza Garza’s quinceañera mass and reception, April 4, 1992. / THF91662

Historically, the quinceañera signified that a girl—having been taught skills like cooking, weaving, and childcare—was ready for marriage. The modern celebration is more likely to signal the beginning of formal dating. Today, the custom of quinceañera remains strongest in Mexico, where it likely originated. It is also celebrated not only in the United States, but also in Spanish-speaking countries in the Americas.

Maritza Garza in her formal quinceañera gown. She selected a dress in a traditional pastel color, pink, purchasing it at a local bridal shop in Detroit. / THF91665

Quinceañera tiara, 2011. / THF150077

An occasion shared with family and friends, the celebration is as elaborate as the family’s wishes and budget allow. The honoree wears a formal gown, along with a tiara or other hair ornament. The oldest tradition was a white dress, with other conventional choices being light pink, blue, or yellow. Now, quinceañera dresses come in many shades—from pastels to darker hues.

Maritza Garza’s quinceañera court of honor. / THF207367

A “court” of family and friends help her celebrate her special day—the young women wear dresses that match and the young men don tuxedos.

Maritza Garza during her quinceañera mass at Most Holy Redeemer Catholic Church in April 1992. Holy Redeemer is located in the heart of Detroit’s Mexicantown neighborhood. Here, masses have been offered in Spanish since 1960 for the Mexican American congregation. / THF91666

A quinceañera begins with a religious service at a Catholic church. Then comes a party with food and dancing. Dancing at the “quince” traditionally includes a choreographed waltz-type dance—one of the highlights of the evening. Toasts are often offered. Sometimes, the cutting of a fancy cake takes place. Symbolic ceremonies at this celebration may include swapping out the honoree’s flat shoes for high heels, slipped onto her feet by her father or parental figure.

Quinceañera celebrations may also include a ride in a lowrider. Arising from Mexican American culture, lowriders are customized family-size cars with street-scraping suspensions and ornamental paint. / THF104135

Some girls choose to celebrate their 15th birthday in a less traditional way, perhaps with a trip abroad. Like other celebrations and rites of passage, quinceañera traditions continue to evolve.

Traditional or non-traditional, a quinceañera celebration makes a young woman feel special as she continues her journey to adulthood.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Michigan, Detroit, home life, childhood, women's history, Hispanic and Latino history, by Jeanine Head Miller

What We Wore: Unpacking a Trunk

Our current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation features clothing from generations of one family. / THF188474

In 1935, 59-year-old Louise Hungerford sent a trunk full of clothing to Henry Ford—clothing that had belonged to her mother’s family, the Mitchells, who had lived in the village of Port Washington, New York, for six generations.

Letter from Louise Hungerford to Henry Ford, September 9, 1935. / THF624791 and THF624793

Ford had opened his museum to the public only two years before. Louise Hungerford was one of the hundreds of people who sent letters to Henry Ford at this time offering to give or sell him objects for his museum. The clothing she sent remains among the oldest in The Henry Ford’s collection.

Map of Port Washington in 1873—the Mitchell home is highlighted in red. / (Not from the collections of The Henry Ford.)

The Mitchell Family and Port Washington

Since the 1690s, the Mitchells had been respected members of the Long Island community of Port Washington as it evolved from farming to shellfishing and construction sand and gravel. In the early 1800s, Port Washington (then called Cow Neck) provided garden produce for New York City residents and hay for their horses—all shipped to the city by packet ships. By the mid-1800s, oystering was profitable in the area. After the Civil War, the sand and gravel industry took hold, providing construction materials for the growing city of New York.

By the early 1900s, the village had become a summer resort and home for the wealthy. The Long Island Railroad reached Port Washington in 1898, providing convenient transportation to the area from New York City. The city’s Knickerbocker Yacht Club moved to Port Washington in 1907. By the mid-1930s—when Louise Hungerford sent Henry Ford the letter and trunk full of family clothing--Port Washington’s quaint homes and wooded hills had been giving way to prestigious residences and sailboats for over 30 years.

Postcard views of Port Washington sent by tourists to family or friends about 1910. / THF624985 and THF624981

Mitchell family occupations evolved through the years along with Port Washington’s local economy: farmer, ship’s captain, stagecoach operator, land developer, highway commissioner, librarian.

Preserving the Past

The Mitchell family had changed with the times—yet hung onto vestiges of its past. Family clothing had been stored for over a century, first in Manhasset Hall, the house that had been home to the Mitchells since the late 1760s. Generations of the extended Mitchell family were born there, grew up there, married there, raised families there, and died there.

By the early 1900s, the Mitchell family home—added onto over the years before being sold out of the family—offered accommodations to tourists. The house was later torn down to make way for a housing development. / THF624821

When the Mitchell home was sold in 1887, the trunk full of clothing remained in the family. By the early 1900s, it was probably kept by Louise Hungerford’s aunt, Wilhelmina, and then by Louise’s mother, Mary. Wilhelmina had remained in Port Washington, helping establish the town’s first library and serving as its first librarian.

Port Washington Public Library, where Wilhelmina Mitchell served as the first librarian. / THF624979

Wilhelmina’s sister, Mary Hungerford, lived most of her adult life in Watertown, New York, after her marriage to produce dealer Egbert Hungerford. But, sometime before 1930, Mary—now a widow—returned to her hometown of Port Washington, along with her daughter, Louise. Wilhelmina Mitchell passed away in 1927; Mary Mitchell Hungerford died in 1933. Fewer Mitchell family members remained in Port Washington to cherish these tucked-away pieces of the family’s past. So Louise Hungerford wrote her letter, offering the trunk and its contents to Henry Ford for his museum.

Looking Inside

Trunk, 1860-1880. / THF188046

What clothing was in the Mitchell family trunk? Once-fashionable apparel. Garments outgrown. Clothing saved for sentimental reasons—perhaps worn on a special occasion or kept in someone’s memory. Everything was handsewn; much was probably homemade.

Louise Hungerford—if she knew—didn’t provide the names of the family members who had once worn these items, and Henry Ford’s assistants didn’t think to ask. For a few garments, though, we made some guesses based on recent research. For many, the mystery remains.

Women’s Slippers, about 1830. / THF156005

Flat-soled slippers were the most common shoe type worn by women during the first part of the 1800s. The delicate pair above might have been donned for a special occasion. Footwear did not yet come in rights and lefts—the soles were straight.

Child’s Dress, 1810-1825. / THF28528

The high-waisted style and pastel silk fabric of the child’s dress depicted above mirror women’s fashions of the 1810s. This dress was probably worn with pantalettes (long underwear with a lace-trimmed hem) by a little girl—though a boy could have worn it as well. Infants and toddlers of both genders wore dresses at this time. The tucks could be let down as the child grew.

Woman’s Gaiters, 1830-1860. / THF31093

Gaiters—low boots with fabric uppers and leather toes and heels—were very popular as boots became the footwear of choice for walking. To give the appearance of daintiness, shoes were made on narrow lasts, a foot-shaped form. By the late 1850s, boots made entirely of leather were the most popular.

Dress, 1780-1795. / THF29521

By the late 1700s, women’s fashions were less full and less formal than earlier. The side seams of this dress are split—allowing entry into a pair of separate pockets that would be tied around the waist. The dress, lined with a different fabric, appears to be reversible. The dress above was possibly worn by Rebecca Hewlett Mitchell, who died in 1790—or by her sister Jane Hewlett, who became the second wife of Rebecca’s husband, John Mitchell, Jr.

Pockets, 1790-1810. / THF30851

In the 1700s and early 1800s, women’s gowns didn’t have pockets stitched in. Instead, women wore separate pockets that tied around their waist. A woman put her hand through a slit in her skirt to pull out what she needed. This pocket has the initials JhM cross-stitched on the back. They were possibly owned by John Mitchell, Jr.’s second wife, Jane Hewlett Mitchell (born 1749), or by his unmarried daughter, Jane H. Mitchell (born 1785).

Boy’s Eton Suit, 1820-1830. / THF28536

During the early 1800s, boys wore Eton suits—short jackets with long, straight trousers—for school or special occasions. The trousers buttoned to a shirt or suspenders under the short jacket. This one, made of silk, was a more expensive version, possibly worn by Charles W. Mitchell, who was born in 1816.

Sleeve Puffs, about 1830. / THF188039

The enormous, exaggerated sleeves of 1830s women’s fashion needed something to hold them up. Sleeve plumpers did the trick, often in the form of down-filled pads like these that would tie on at the shoulder under the dress.

Corset, 1830-1840. / THF30853

A corset was a supportive garment worn under a woman’s clothing. A busk—a flat piece of wood, metal, or animal bone—slid into the fabric pocket in front to keep the corset straight, while also ensuring an upright posture and a flatter stomach.

Quilted Petticoat, 1760-1780. / THF30943

In the mid-to-late 1700s, women’s gowns had an open front or were looped up to reveal the petticoat underneath. Fashionable quilted petticoats usually had decorative stitching along the hemline. Women might quilt their own petticoats or buy one made in England—American merchants imported thousands during this time.

Man’s Trousers, 1820-1850. / THF30007

These trousers appear to have been worn on an everyday basis for work. Both knees, having seen a lot of wear, have careful repairs.

Woman’s House Slippers, 1840-1855. / THF156001

The quilted fabric on these house slippers made them warmer—quite welcome during cold New York winters in a house heated only by fireplaces or cast-iron stoves.

Calash Bonnet, 1830-1839. / THF188043

Collapsible calash bonnets were named after the folding tops of horse-drawn carriages. These bonnets had been popular during the late 1700s with a balloon-shaped hood that protected the elaborate hairstyles then in fashion. Calash bonnets returned in the 1820s and 1830s, this time following current fashion—a small crown at the back of the head and an open brim. The ruffle at the back shaded the neck.

| When Henry Ford was collecting during the mid-1900s, many of the objects were gathered from New England or the Midwest—often from people of similar backgrounds to his. We are looking to make our clothing collection and the stories it tells more inclusive and diverse. Do you have clothing you would like us to consider for The Henry Ford’s collection? Please contact us. |

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Joan DeMeo Lager of the Cow Neck Peninsula Historical Society, Phyllis Sternemann, church historian at Christ Church Manhasset, and Gil Gallagher, curatorial volunteer at The Henry Ford, for meticulous research that revealed the story of generations of Port Washington Mitchells. Thanks also to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

New York, 19th century, 18th century, women's history, What We Wore, home life, Henry Ford Museum, fashion, by Jeanine Head Miller

The Changing Nature of Sewing

This 1881 Singer sewing machine is on exhibit in Made in America in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Isaac Singer developed the first practical sewing machine for home use in the 1850s. / THF173635

Innovation has intended, and often unintended, effects. Take the sewing machine, for example. Its invention in the mid-1840s would make clothing more available and affordable. Yet, ironically, the sewing machine also resulted in a decline of sewing skills—not immediately, but over time. Nowadays, few of us know how to make clothing.

Once, things were very different. For centuries, sewing a family’s clothing by hand was a time-consuming and constant task for women. A woman often made hundreds of garments in her lifetime; all young girls were taught to sew.

A trade card for Clark's O.N.T. Spool Cotton from the late nineteenth century depicts a young girl using her sewing skills to repair a rip in her brother’s jacket so that “It will be as good as new and Ma won’t know!” / THF298697

When the sewing machine came on the scene during the mid-1800s, this handy invention made a big difference. For example, it now took about an hour to sew a man’s shirt by machine—rather than 14 hours by hand. In the 1850s, clothing manufacturers quickly acquired sewing machines for their factories, and, as they became less expensive, people bought them for home use.

While machines made it easier to make clothing at home, buying clothing ready-made was even less work. By the early 1900s, the ready-to-wear industry offered a broad range of attractive clothing for men, women, and children. Increasingly, people bought their clothing in stores rather than making it themselves.

Patricia Jean Davis wears a prom dress she made herself in 1960. / THF123841

Sewing skills may have declined, but what have we gained? A lot. Mass-produced clothing has raised our standard of living: stylish, affordable clothing can be had off the rack. For many, sewing remains a creative outlet, rather than a required task. For them, making clothing is no longer something you have to do, but something you want to do.

This post was adapted from a stop on our forthcoming “Hidden Stories of Manufacturing” tour of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in the THF Connect app, written by Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. To learn more about or download the THF Connect app, click here.

Additional Readings:

- Collecting Mobility: Insights from Ford Motor Company

- The Hitchcock Chair: An American Innovation

- The Wool Carding Machine

- Making the Cut: The Tripp Sawmill

Henry Ford Museum, women's history, THF Connect app, manufacturing, making, home life, fashion, by Jeanine Head Miller

“Whenever Henry Ford visited England, he always liked to spend a few days in the Cotswold Country, of which he was very fond … during these sojourns I had many happy times driving Mr. Ford around the lovely scenes which abound in this part of Britain.”

—Herbert Morton, Strange Commissions for Henry Ford

A winding road through a Cotswold village, October 1930. / THF148434, detail

The Cotswolds Catch Henry Ford’s Eye

Henry Ford loved the Cotswolds, a rural region in southwest England—nearly 800 square miles of rolling hills, pastures, and small villages.

During the Middle Ages, a vibrant wool trade brought the Cotswolds great prosperity—at its heart was a breed of sheep known as Cotswold Lions. For centuries, the Cotswold region was well-known throughout Europe for the quality of its wool. Raising sheep, trading in wool, and woolen cloth fueled England’s economic growth from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution. Cotswold’s prosperity and its rich belt of limestone that provided ready building material resulted in a distinctive style of architecture: limestone homes, churches, shops, and farm buildings of simplicity and grace.

During Henry Ford’s trips to the Cotswolds in the 1920s, he became intrigued with the area’s natural beauty and charming architecture—all those lovely stone buildings that “blossomed” among the verdant green countryside and clustered together in Cotswold’s picturesque villages. By early 1929, Ford had decided he wanted to acquire and move a Cotswold home to Greenfield Village.

A letter dated February 4, 1929, from Ford secretary Frank Campsall described that Ford was looking for “an old style that has not had too many changes made to it that could be restored to its true type.” Herbert Morton, Ford’s English agent, was assigned the task of locating and purchasing a modest building “possessing as many pretty local features as might be found.” Morton began to roam the countryside looking for just such a house. It wasn’t easy. Cotswold villages were far apart, so his search covered an extensive area. Owners of desirable properties were often unwilling to sell. Those buildings that were for sale might have only one nice feature—for example, a lovely doorway, but no attractive window elements.

Cotswold Cottage (buildings shown at left) nestled among the rolling hills in Chedworth, 1929–1930. / THF236012

Herbert Morton was driving through the tiny village of Lower Chedworth when he saw it. Constructed of native limestone, the cottage had “a nice doorway, mullions to the windows, and age mellowed drip-stones.” Morton knew he had found the house he had been looking for. It was late in the day, and not wanting to knock on the door and ask if the home was for sale, Morton returned to the town of Cheltenham, where he was staying.

The next morning Morton strolled along a street in Cheltenham, pondering how to approach the home’s owner. He stopped to look into a real estate agent’s window—and saw a photograph of the house, which was being offered for sale! Later that day, Morton arrived in Chedworth, and was greeted by the owner, Margaret Cannon Smith, and her father. The cottage, constructed out of native limestone in the early 1600s, had begun life as a single cottage, with the second cottage added a bit later.

Interior of Cotswold Cottage, 1929-1930. / THF236052

The home was just as quaint inside—large open fireplaces with the mantels supported on oak beams. Heavy oak beams graced the ceilings and the roof. Spiral stone staircases led to the second floor. Morton bought the house and the two acres on which it stood under his own name from Margaret Smith in April 1929 for approximately $5000. Ford’s name was kept quiet. Had the seller been aware that the actual purchaser was Henry Ford, the asking price might have been higher.

Cotswold Cottage (probably built about 1619) as it looked when Herbert Morton spotted it, 1929–1930. / THF236020

“Perfecting” the Cotswold Look

Over the next several months, Herbert Morton and Frank Campsall, Ford’s personal secretary, traded correspondence concerning repairs and (with the best of intentions on Ford’s part) some “improvements” Ford wanted done to the building: the addition of architectural features that best exemplified the Cotswold style. Morton sent sketches, provided by builder and contractor W. Cox-Howman from nearby Stow-on-the-Wold, showing typical Cotswold architectural features not already represented in the cottage from which to choose. Ford selected the sketch which offered the largest number of typical Cotswold features.

Ford’s added features on the left cottage included a porch (a copy of one in the Cotswold village of Rissington), a dormer window, a bay window, and a beehive oven.

Cotswold Cottage, 1929–1930, showing modifications requested by Henry Ford: the beehive oven, porch, and dormer window. / THF235980

Bay window added to the left cottage by Henry Ford (shown 1929–1930). Iron casement windows were added throughout. / THF236054

The cottage on the right got a doorway “makeover” and some dove-holes. These holes are commonly found in the walls of barns, but not in houses. It would have been rather unappealing to have bird droppings so near the house!

Ford’s modifications to the right cottage—a new doorway (top) and dove-holes (bottom) on the upper wall. / THF236004, THF235988

Cotswold Cottage, now sporting Henry Ford’s desired alterations. / THF235984

Ford wanted the modifications completed before the building was disassembled—perhaps so that he could establish the final “look” of the cottage, as well as be certain that there were sufficient building materials. The appearance of the house now reflected both the early 1600s and the 1920s—each of these time periods became part of the cottage’s history. Ford’s additions, though not original to the house, added visual appeal.

The modifications were completed by early October 1929. The land the cottage stood on was transferred to the Ford Motor Company and later sold.

Cotswold Cottage Comes to America

Cotswold Cottage being disassembled. / THF148471

By January 1930, the dismantling of the modified cottage was in process. To carry out the disassembly, Morton again hired local contractor W. Cox-Howman.

Building components being crated for shipment to the United States. / THF148475

Doors, windows, staircases, and other architectural features were removed and packed in 211 crates.

Cotswold building stones ready for shipment in burlap sacks. / THF148477

The building stones were placed in 506 burlap sacks.

Cotswold barn and stable on original site, 1929–1930. / THF235974

The adjacent barn and stable, as well as the fence, were also dismantled and shipped along with the cottage.

Hauled by a Great Western Railway tank engine, 67 train cars transported the materials from the Cotswolds to London to be shipped overseas. / THF132778

The disassembled cottage, fence, and stable—nearly 500 tons worth—were ready for shipment in late March 1930. The materials were loaded into 67 Great Western Railway cars and transported to Brentford, west London, where they were carefully transferred to the London docks. From there, the Cotswold stones crossed the Atlantic on the SS London Citizen.

As one might suspect, it wasn’t a simple or inexpensive move. The sacks used to pack many of the stones were in rough condition when they arrived in New Jersey—at 600 to 1200 pounds per package, the stones were too heavy for the sacks. So, the stones were placed into smaller sacks that were better able to withstand the last leg of their journey by train from New Jersey to Dearborn. Not all of the crates were numbered; some that were had since lost their markings. One package went missing and was never accounted for—a situation complicated, perhaps, by the stones having been repackaged into smaller sacks.

Despite the problems, all the stones arrived in Dearborn in decent shape—Ford’s project manager/architect, Edward Cutler, commented that there was no breakage. Too, Herbert Morton had anticipated that some roof tiles and timbers might need to be replaced, so he had sent some extra materials along—materials taken from old cottages in the Cotswolds that were being torn down.

Cotswold “Reborn”

In April 1930, the disassembled Cotswold Cottage and its associated structures arrived at Greenfield Village. English contractor Cox-Howman sent two men, mason C.T. Troughton and carpenter William H. Ratcliffe, to Dearborn to help re-erect the house. Workers from Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant also came to assist. Reassembling the Cotswold buildings began in early July, with most of the work completed by late September. Henry Ford was frequently on site as Cotswold Cottage took its place stone-by-stone in Greenfield Village.

Before the English craftsmen returned home, Clara Ford arranged a special lunch at the cottage, with food prepared in the cottage’s beehive oven. The men also enjoyed a sight-seeing trip to Niagara Falls before they left for England in late November.

By the end of July 1930, the cottage walls were nearly completed. / THF148485

On August 20, 1930, the buildings were ready for their shingles to be put in place. The stone shingles were put up with copper nails, a more modern method than the wooden pegs originally used. / THF148497

Cotswold barn, stable, and dovecote, photographed by Michele Andonian. / THF53508

Free-standing dovecotes, designed to house pigeons or doves which provided a source of fertilizer, eggs, and meat, were not associated with buildings such as Cotswold Cottage. They were found at the homes of the elite. Still, for good measure, Ford added a dovecote to the grouping about 1935. Cutler made several plans and Ford chose a design modeled on a dovecote in Chesham, England.

Henry and Clara Ford Return to the Cotswolds

The Lygon Arms in Broadway, where the Fords stayed when visiting the Cotswolds. / THF148435, detail

As reconstruction of Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village was wrapping up in the fall of 1930, Henry and Clara Ford set off for a trip to England. While visiting the Cotswolds, the Fords stayed at their usual hotel, the Lygon Arms in Broadway, one of the most frequently visited of all Cotswold villages.

Henry (center) and Clara Ford (second from left) visit the original site of Cotswold Cottage, October 1930. / THF148446, detail

While in the Cotswolds, Henry Ford unsurprisingly asked Morton to take him and Clara to the site where the cottage had been.

Cotswold village of Stow-on-the-Wold, 1930. / THF148440, detail

At Stow-on-the-Wold, the Fords called on the families of the English mason and carpenter sent to Dearborn to help reassemble the Cotswold buildings.

Village of Snowshill in the Cotswolds. / THF148437, detail

During this visit to the Cotswolds, the Fords also stopped by the village of Snowshill, not far from Broadway, where the Fords were staying. Here, Henry Ford examined a 1600s forge and its contents—a place where generations of blacksmiths had produced wrought iron farm equipment and household objects, as well as iron repair work, for people in the community.

The forge on its original site at Snowshill, 1930. / THF146942

A few weeks later, Ford purchased the dilapidated building. He would have it dismantled, and then shipped to Dearborn in February 1931. The reconstructed Cotswold Forge would take its place near the Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village.

To see more photos taken during Henry and Clara Ford’s 1930 tour of the Cotswolds, check out this photograph album in our Digital Collections.

Cotswold Cottage Complete in Greenfield Village—Including Wooly “Residents”

Completed the previous fall, Cotswold Cottage is dusted with snow in this January 1931 photograph. Cotswold sheep gather in the barnyard, watched over by Rover, Cotswold’s faithful sheepdog. (Learn Rover's story here.) / THF623050

A Cotswold sheep (and feline friend) in the barnyard, 1932. / THF134679

Beyond the building itself, Henry Ford brought over Cotswold sheep to inhabit the Cotswold barnyard. Sheep of this breed are known as Cotswold Lions because of their long, shaggy coats and faintly golden hue.

Cotswold Cottage stood ready to welcome—and charm—visitors when Greenfield Village opened to the public in June 1933. / THF129639

By the Way: Who Once Lived in Cotswold Cottage?

Cotswold Cottage, as it looked in the early 1900s. From Old Cottages Farm-Houses, and Other Stone Buildings in the Cotswold District, 1905, by W. Galsworthy Davie and E. Guy Dawber. / THF284946

Before Henry Ford acquired Cotswold Cottage for Greenfield Village, the house had been lived in for over 300 years, from the early 1600s into the late 1920s. Many of the rapid changes created by the Industrial Revolution bypassed the Cotswold region and in the 1920s, many area residents still lived in similar stone cottages. In previous centuries, many of the region’s inhabitants had farmed, raised sheep, worked in the wool or clothing trades, cut limestone in the local quarries, or worked as masons constructing the region’s distinctive stone buildings. Later, silk- and glove-making industries came to the Cotswolds, though agriculture remained important. By the early 1900s, tourism became a growing part of the region’s economy.

A complete history of those who once occupied Greenfield Village’s Cotswold Cottage is not known, but we’ve identified some of the owners since the mid-1700s. The first residents who can be documented are Robert Sley and his wife Mary Robbins Sley in 1748. Sley was a yeoman, a farmer who owned the land he worked. From 1790 at least until 1872, Cotswold was owned by several generations of Robbins descendants named Smith, who were masons or limeburners (people who burned limestone in a kiln to obtain lime for mixing with sand to make mortar).

As the Cotswold region gradually evolved over time, so too did the nature of some of its residents. From 1920 to 1923, Austin Lane Poole and his young family owned the Cotswold Cottage. Medieval historian, fellow, and tutor at St. John’s College at Oxford University (about 35 miles away), Poole was a scholar who also enjoyed hands-on work improving the succession of Cotswold houses that he owned. Austin Poole had gathered documents relating to the Sley/Robbins/Smith families spanning 1748 through 1872. It was these deeds and wills that revealed the names of some of Cotswold Cottage’s former owners. In 1937, after learning that the cottage had been moved to Greenfield Village, Poole gave these documents to Henry Ford.

In 1926, Margaret Cannon Smith purchased the house, selling it in 1929 to Herbert Morton, on Henry Ford’s behalf.

“Olde English” Captures the American Imagination

At the time that Henry Ford brought Cotswold Cottage to Greenfield Village, many Americans were drawn to historic English architectural design—what became known as Tudor Revival. The style is based on a variety of late Middle Ages and early Renaissance English architecture. Tudor Revival, with its range of details reminiscent of thatched-roof cottages, Cotswold-style homes, and grand half-timbered manor houses, became the inspiration for many middle-class and upper-class homes of the 1920s and 1930.

These picturesque houses filled suburban neighborhoods and graced the estates of the wealthy. Houses with half-timbering and elaborate detail were often the most obvious examples of these English revival houses, but unassuming cottage-style homes also took their place in American towns and cities. Mansion or cottage, imposing or whimsical, the Tudor Revival house was often made of brick or stone veneer, was usually asymmetrical, and had a steep, multi-gabled roof. Other characteristics included entries in front-facing gables, arched doorways, large stone or brick chimneys (often at the front of the house), and small-paned casement windows.

Edsel Ford’s home at Gaukler Pointe, about 1930. / THF112530

Henry Ford’s son Edsel and his wife Eleanor built their impressive but unpretentious home, Gaukler Pointe, in the Cotswold Revival style in the late 1920s.

Postcard, Postum Cereal Company office building in Battle Creek, Michigan, about 1915. / THF148469

Tudor Revival design found its way into non-residential buildings as well. The Postum Cereal Company (now Post Cereals) of Battle Creek, Michigan, chose to build an office building in this centuries-old English style.

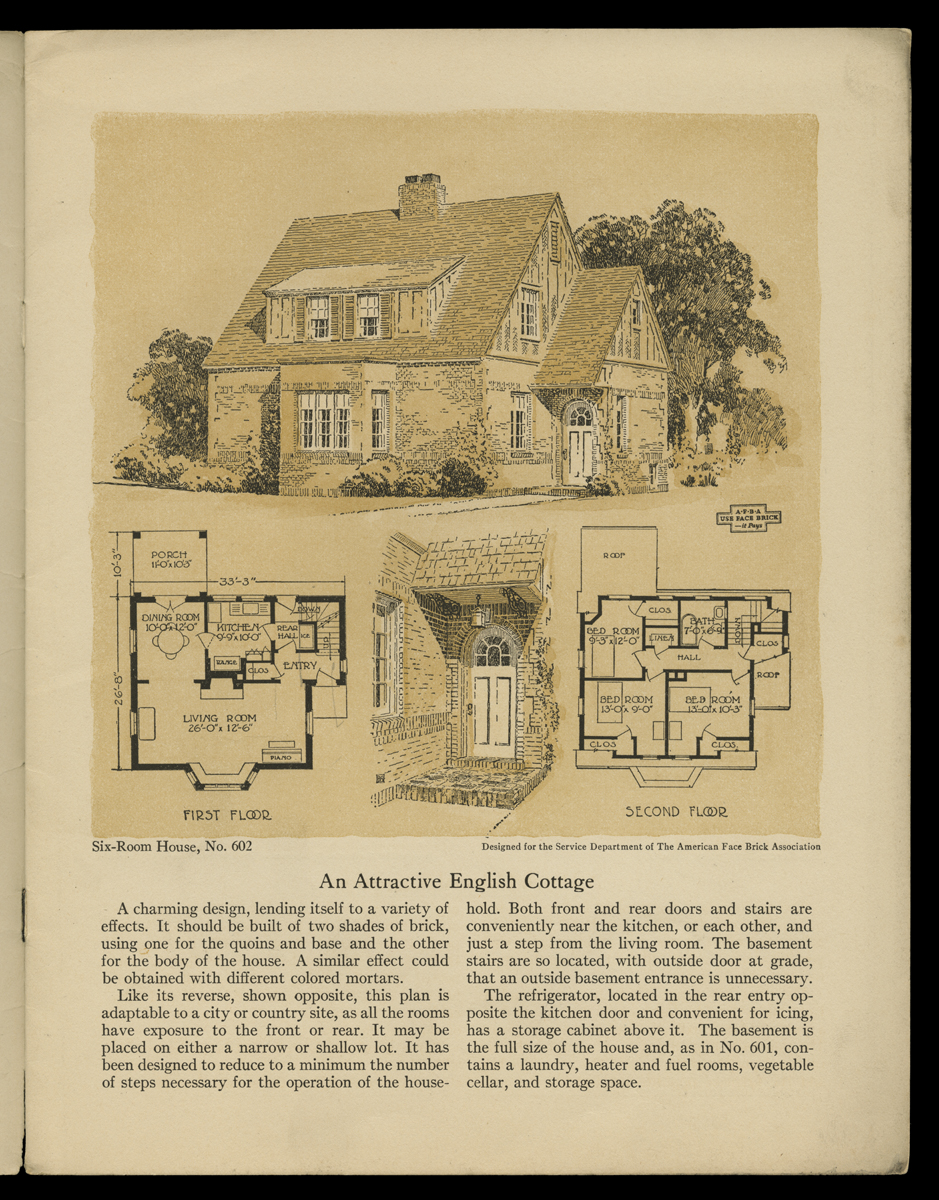

Plan for “An Attractive English Cottage” from the American Face Brick Association plan book, 1921. / THF148542

Plans for English-inspired homes offered by Curtis Companies Inc., 1933. / THF148549, THF148550, THF148553

Tudor Revival homes for the middle-class, generally more common and often smaller in size, appeared in house pattern books of the 1920s and 1930s.

Sideboard, part of a dining room suite made in the English Revival style, 1925–1930. / THF99617

The Tudor Revival called for period-style furnishings as well. “Old English” was one of the most common designs found in fashionable dining rooms during the 1920s and 1930s.

Christmas card, 1929. / THF4485

Even English-themed Christmas cards were popular.

Cotswold Cottage—A Perennial Favorite

Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF53489

Henry Ford was not alone in his attraction to the distinctive architecture of the Cotswold region and the English cottage he transported to America. Cotswold Cottage remains a favorite with many visitors to Greenfield Village, providing a unique and memorable experience.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Cotswold Cottage Tea

- Interior of Cotswold Cottage at its Original Site, Chedworth, Gloucestershire, England, 1929-1930

- Cotswold Cottage

home life, design, farm animals, travel, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village, by Jeanine Head Miller

| “The fact that Webster dwelt and worked on his dictionary there gives this structure singular historic interest…. That all this must disappear shortly before the crowbars of the wreckers is a matter of genuine regret…” —J. Frederick Kelly, New Haven resident and architect, quoted in New Haven Register, July 20, 1936 |

Article from the New Haven Register, New Haven, Connecticut, July 20, 1936. / THF624813

In the mid-1930s, Yale University, owner of the Noah Webster Home on Temple Street in New Haven, Connecticut, decided this former home of one of its notable alumni needed to be torn down. It was the Depression, and Yale’s financial situation required some retrenchment. Tearing down the Webster house, along with eleven other Yale-owned homes, would cut the university’s tax bill and save the expense of maintenance, while providing space for new construction better suited to the university’s needs.

The house came very near to being demolished.

In this comfortable home, completed in 1823 at Temple and Grove streets, Noah Webster had enjoyed an active family life, written many of his publications, and completed his ultimate life’s work—America’s first dictionary. Noah and Rebecca Webster had moved to New Haven in their later years to be near family and friends, as well as the library at nearby Yale College. While living in this house, Webster published his famous American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828.

Silhouette of Noah and Rebecca Webster by Samuel Metford, 1842. / THF119764

What happened to the house after the deaths of Noah in 1843 and Rebecca in 1847? For the next seven decades, the Temple Street house was filled with new generations of Webster descendants and their relations.

The Trowbridge Era

After Noah Webster’s death in 1843, the house became part of Webster’s estate. In his will, his wife Rebecca received the lifetime use of the Temple Street house. In March 1849, executors of the Webster estate, William Ellsworth (a son-in-law) and Henry White, deeded the property to Henry Trowbridge, Jr., a merchant who sold goods imported from the Far East and a director of the New Haven Bank. (Trowbridge took out a mortgage on the house in 1850, probably to compensate the estate for the value of the house.) Trowbridge had married Webster granddaughter Mary Southgate in 1838. Mary had been raised by Noah and Rebecca Webster and had grown up in the Temple Street house. Henry and Mary Trowbridge had six children: five daughters as well as a son who died young. Mary Southgate Trowbridge passed away in May 1860 of tuberculosis at the age of 41.

In 1861, Henry Trowbridge married again, to Sarah Coles Hull. Their son Courtlandt, born in 1870, was the only surviving child of the marriage.

About 1870, prosperous Henry Trowbridge decided to remodel the house, adding a wealth of “updates” in the then-fashionable Victorian style. These included five bay windows, as well as marble fireplace mantles, plaster ceiling medallions, exterior and interior doors, and elaborately carved walnut woodwork on the first floor. Trowbridge also lengthened the first-floor windows and built a brick addition on the back.

Noah Webster Home showing Victorian-era changes, including the bay windows and addition at the rear of the home. Top photo taken about 1927; bottom photo, in 1936. / THF236369, THF236375

Over the years, the house was filled with the rhythms of everyday life and the comings and goings of family. Nine Trowbridge children grew up there—six of them were born in the house and three of them died there. Daughters married and moved out. One Trowbridge daughter made two long-distance visits home during the years she and her merchant husband lived in Hong Kong. Another returned home for a time as a widow with a young child. In the 1910s, during the final years of Trowbridge ownership, the widowed Sarah lived in the house with her son Courtlandt, his wife Cornelia, and their three children.

Webster Home—perhaps a bit overgrown—about 1912. / THF236373

In 1918, the year following his mother’s death, 68-year-old Courtlandt Trowbridge sold the Temple Street house in which he had lived since birth “for the consideration of one dollar,” deeding the property to the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, located a block from the Webster house on Grove Street. Courtlandt, a Sheffield graduate, then moved to Washington, a rural village in northwest Connecticut, along with his wife, Sarah, and youngest son, Robert.

From Family Home to College Dorm

Postcard, Sheffield Scientific School, Yale College, 1915-1920. / THF624831

Sheffield Scientific School offered courses in science and engineering. Following World War I, its curriculum gradually became completely integrated with Yale University’s—undergraduate courses were taught at Sheffield from 1919 to 1945, coexisting with Yale’s science programs. (Sheffield would cease to function as a separate entity in 1956.) The Sheffield Scientific School used the Webster house as a men’s dormitory for freshmen for almost 20 years.

Postcard, Vanderbilt-Sheffield dormitories on Chapel Street in New Haven, about 1909. / THF624833

The Webster house wasn’t Sheffield’s only dormitory, though. The impressive Vanderbilt-Sheffield dorms, dating from the early 1900s, served most of Sheffield’s students. The Noah Webster Home provided some additional space for freshmen to live.

A view of Temple street about 1927, during the time Yale University used the Webster house (shown at far right) as a dormitory. / THF236367

In 1936, Yale decided that retaining the “non-revenue-bearing” house was not financially viable for the university. It was no longer needed as a dorm because of the construction of Yale’s Dwight College, opened in September 1935. Removing the Webster home would also provide space for growth for the university. (The site would become part of Yale’s Silliman College.)

A Timely Rescue

In early July 1936, Yale University was granted permission to demolish the house. (The louvered, elliptical window was to go to the Yale Art School.) The house was sold to Charles Merberg and Sons, a wrecking company. But there were attempts to save the home. Soon after Yale University was granted a permit on July 3 to tear down the house, the local newspaper, the New Haven Register, began a campaign to save it. New Haven resident Arnold Dana, a retired journalist, offered to contribute to a fund to preserve the house, but no additional offers of funds came. For several weeks, articles appeared in newspapers in New York and other large cities on the subject.

Initial interest in preserving the building by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA, now Historic New England) waned because of the Victorian-era changes. William Sumner Appleton, the society’s founder and a chief force behind the preservation of many historic buildings in New England, thought the building might make an interesting museum if a private individual would take on the project. Appleton said that SPNEA had no funds to do so.

J. Frederick Kelly, a New Haven resident, architect, and author of books on early Connecticut architecture, noted the building’s historical significance and commented on its architecture: “…the fine proportion and delicate scale of the Temple Street façade mark it as one of unusual distinction. The design of the gable … contains a very handsome elliptical louvre … an outstanding feature that has no counterpart in the East so far as I am aware.”

Telegram to Edsel Ford concerning the imminent demolition of the Noah Webster Home in New Haven, Connecticut. / THF624805

On July 29, R.T. Haines Halsey sent a telegram to Edsel Ford. Halsey let Edsel know that the Webster house was “in the hands of wreckers” and that it would fit in well with “your father’s scheme” for Greenfield Village. Immediate action was needed to save the house.

1924 postcard, American wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, built to display American decorative arts from the 1600s to the early 1800s. / THF148348

Halsey, a retired New York City stockbroker, was a collector of decorative arts who was instrumental in the opening of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City in 1924. In the 1930s, Halsey had become a research assistant in the Stirling Library at Yale University. Halsey may have chosen to contact Henry through Edsel because of Edsel’s interest in art and involvement with the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

On July 27, Ralph J. Sennott, manager of the Wayside Inn in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, a historic inn restored by Henry Ford, sent Ford a letter. (Perhaps it reached Ford about the time that Halsey’s telegram did.) Sennott also made Ford aware that the Webster home was in the hands of the wrecking company and that the building needed to be removed by September 1. The wrecker was willing to sell the house, but demolition work was to begin August 3. Henry Ford paid a $100 deposit on the house on August 2 to prevent demolition going forward. Ford was given until September 15 to make his final decision on acquiring the building.

Henry Ford arrived in New Haven on September 10 to see the Webster home in person. According to Lewis Merberg of the wrecking company, Ford appreciated the building for its historical significance more than for its “antiquity.” Noah Webster likely would have appealed to Ford as the author of the popular “Blue-Backed Speller,” used by many early American schools. Ford completed the purchase, paying about $1000 for the home.

Letter from Harold Davis of the Historic American Buildings Survey to Henry Ford, September 14, 1936. / THF624811

Noting Ford’s interest in the building, Harold Davis, the Connecticut district officer of the Historic America Building Survey, made Ford aware that the organization—whose purpose it was to measure and record historic buildings—had documented the Webster house in 1934. Ford acquired copies of these drawings, which were available at the Library of Congress.

The Noah Webster Home Moves to Dearborn

When Edward Cutler, the man responsible for moving and reassembling buildings in Greenfield Village for Henry Ford, arrived in New Haven in mid-September, wreckers had already removed windows and other parts of the house. The interior was not in the best state of repair—likely a little worse for wear after almost 20 years serving as home to college freshmen. Additional documentation of the house was needed before a wrecking crew disassembled the building under Edward Cutler’s direction. Cutler took more measurements. More photos of the home’s exterior and interior would assist with its reassembly in Greenfield Village.

Edward J. Cutler made detailed drawings of the house before it was dismantled. / THF132776

Image of the back of the Webster home taken in 1936 by a local New Haven photographer, perhaps at the request of Henry Ford or one of his representatives. / THF236377

Interior of house, view from the dining room looking towards the bay window in the sitting room. / THF236381

Edsel’s son Henry Ford II, then a Yale freshman, posed in front of the Noah Webster Home during its dismantling in October 1936. / THF624803

With this move, the Noah Webster Home would shed some of its Victorian-era “modernizing.” Cutler removed the four second-floor bay windows added during the Trowbridge renovation. He did retain some Trowbridge updates—exterior and interior doors, interior architectural details, and the first-floor bay window.

In October 1936, the Webster house was dismantled and packed up in about two weeks, according to Ed Cutler. Then it was shipped to Dearborn.

Webster Home reassembled in Greenfield Village, September 1938. / THF132717

Reassembly in Greenfield Village took about a year. In June 1937, workmen broke ground for the foundation of the home. By the end of December, most of the exterior work had been completed. Progress on the interior continued through the winter months. By July 1938, finishing touches were being added to the house.

Edison Institute High School girls prepare a meal in the Webster kitchen, 1942. THF118924

Until 1946, high school girls from the Edison Institute Schools used the Noah Webster Home as a live-in home economics laboratory—a modern kitchen was provided in the brick addition built on the back of the home. Henry Ford had opened the school on the campus of his museum and village in 1929.

Webster dining room in 1963. / THF147776

The Noah Webster Home finally opened to the public for the first time in 1962, telling the story of Webster and America’s first dictionary. Yet the Webster house was furnished to showcase fine furnishings in period room-like settings, rather than reflecting a household whose elderly inhabitants started housekeeping decades before.

Noah Webster Home Today

Noah Webster Home in Greenfield Village. / THF1882

In 1989, after much research on the house and the Webster family, museum staff made the decision to return the entire home to its original appearance during the Websters’ lifetime. The remaining Victorian additions were removed, including the first-floor bay window, interior woodwork, and interior doorways added during the Trowbridge era.

Noah Webster Home sitting room after 1989 reinstallation. / THF186509

Webster family correspondence and other documents painted a picture of a household that included not only family activities, but more public ones as well. Based on this research, curators created a new furnishings plan for the reinstallation. Now visitors could imagine the Websters living there.

Pay the Websters a Visit

Whew—close call. In 1936, the Noah Webster Home was saved in the nick of time.

Now that you know “the rest of the story,” stop by the Webster Home in Greenfield Village. Enjoy this immersive look into the past and its power to inspire us today. Hear the story of the Websters’ lives in this home during the 1830s, learn about Noah’s work on America’s first dictionary and other publications, and experience the furnished rooms that give the impression that the Websters still live there today.

For more on the Noah Webster Home, see “The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner.”

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Noah Webster Home, Henry Ford, home life, by Jeanine Head Miller, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

Meet Calvin Wood, Caterer of Eagle Tavern

“Calvin Wood, Caterer” sign outside Eagle Tavern. / THF237357

Outside Greenfield Village’s Eagle Tavern, an early 1830s building originally from Clinton, Michigan, is a sign that reads: “Calvin Wood, Caterer.” Yes, Calvin Wood was a real guy—and the tavernkeeper at Eagle Tavern in 1850. The Eagle Tavern building was just a few years old when Calvin Wood and his young family arrived in nearby Tecumseh Township about 1834. Little could Calvin guess that life’s twists and turns would mean that one day he would be the tavernkeeper there!

William H. Ladd’s Eating House, Boston, about 1840. Image courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Why caterer? In the 19th century, a “caterer” meant someone who not only provided food and drink, but who also catered in any way to the requirements of others. Some tavernkeepers, like Calvin Wood, referred to themselves as “caterers.” As Eagle Tavern’s tavernkeeper a few years hence, Calvin Wood would offer a bed for the night to travelers, a place to get a meal or a drink, a place to socialize and learn the latest news, and a ballroom upstairs to hold dances and other community events.

Moving to Michigan

1857 map of portion of Tecumseh Township, inset from “Map of Lenawee County, Michigan” (Philadelphia: Bechler & Wenig & Co., 1857), highlighted to show Calvin Wood’s farm located southeast of the village of Clinton. Map image from Library of Congress.

In the mid-1830s, Calvin and his wife Jerusha sold their land in Onondaga, New York, and settled on a farm with their children in Lenawee County, Michigan—a few miles south of the village of Clinton and a few miles north of the village of Tecumseh. (Calvin and Jerusha’s children probably numbered four—all but one would die in infancy or childhood.) The Wood family had plenty of company in this journey. From 1830 to 1837, Michigan was the most popular destination for westward-moving settlers caught up in the highly contagious “Michigan Fever.” During this time, the Michigan Territory’s population grew five-fold!

The move to Michigan offered promise, but the years ahead also held misfortune. In the early 1840s Calvin lost Jerusha, and some of their children likely passed away during this time as well. By 1843, Calvin had married for a second time, this time to Clinton resident Harriet Frost Barnum.

Harriet had left New York State with her parents and siblings and settled in Monroe County by 1830. The following year, 19-year-old Harriet married John Wesley Barnum. The Barnums moved to Clinton, where they were operating a “log hotel” along the Chicago Road in the fall of 1835. In October 1836, Wesley Barnum died, leaving Harriet a young widow with two daughters: Irene, age two, and Frances, age four. After their marriage, Calvin and Harriet’s blended household included not only Harriet’s two daughters, but also Calvin’s son. (There may also have been other Wood children in the home as well, though they might have passed away before this time.)

Calvin Wood, Tavernkeeper

In the early and mid-19th century, tavernkeeping was a small and competitive business. It didn’t require much experience or capital, and as a result, most taverns changed hands often. In 1849, farmer Calvin Wood decided to try his hand at tavernkeeping, an occupation he would engage in for five years. Many other tavernkeepers were farmers as well—like other farmer-tavernkeepers, Calvin Wood probably supplied much of the food for tavern customers from his farm. Calvin Wood didn’t run the tavern alone—a tavernkeeper’s family was often deeply involved in business operations as well. And, of course, Calvin’s wife Harriet was the one with previous experience running a tavern! Harriet would have supervised food preparation and the housekeeping. Frances and Irene likely helped their mother and stepfather in the tavern at times. Calvin’s son, Charles, was married and operating his own Tecumseh Township farm by this time.

Residence of F.S. Snow, & D. Keyes, Clinton, Michigan,” detail from Combination Atlas Map of Lenawee County, Michigan, 1874. / THF108376

By the time that Calvin and Harriet Wood were operating the Eagle Tavern, from 1849 to 1854, the first stage of frontier life had passed in southern Michigan. Frame and brick buildings had replaced many of the log structures often constructed by the early settlers twenty-some years before. The countryside had been mostly cleared and was now populated by established farms.

Mail coaches changing horses at a New England tavern, 1855. / THF120729

Detail from Michigan Southern & E. & K. RR notice, April 1850. / THF108378, not from the collections of The Henry Ford

Yet Clinton, whose early growth had been fueled by its advantageous position on the main stagecoach route between Detroit and Chicago, found itself bypassed by railroad lines to the north and south. The Chicago Road ran right in front of the Eagle Tavern, but it was no longer the well-traveled route it had once been. Yet stagecoaches still came through the village, transporting mail and providing transportation links to cities on the Michigan Central and Michigan Southern railroad lines.

Map of Clinton, Michigan, inset from “Map of Lenawee County, Michigan” (Philadelphia: Bechler & Wenig & Co., 1857). Map image from Library of Congress.

Though Clinton remained a small village, it was an important economic and social link—its businesses and stores still served the basic needs of the local community. During the years that Calvin operated the Eagle Tavern, Clinton businesses included a flour mill, a tannery, a plow factory, a wagon maker, wheelwrights, millwrights, coopers who made barrels, cabinetmakers who made furniture, chair manufacturers, and a boot and shoe maker. Clinton had a blacksmith shop and a livery stable. The village also had carpenters, painters, and masons. Tailors and seamstresses made clothing. A milliner crafted ladies’ hats. Merchants offered the locals the opportunity to purchase goods produced in other parts of the country, and even the world: groceries (like salt, sugar, coffee, and tea), cloth, notions, medicines, hardware, tools, crockery, and boots and shoes. A barber provided haircuts and shaves. Three doctors provided medical care. In 1850, like Calvin and Harriet Wood, most of Clinton’s inhabitants had Yankee roots—they had been born in New York or New England. But there were also a number of foreign-born people from Ireland, Scotland, England, or Germany. At least two African American families also made Clinton their home.

Many of Calvin’s customers were probably people who lived in the village. Others lived on farms in the surrounding countryside. Calvin’s customers would have included some travelers—in 1850, people still passed through Clinton on the stagecoach, in their own wagons or buggies, or on horseback.

Advertisements for Eagle Hotel, Clinton, and The Old Clinton Eagle, Tecumseh Herald, 1850. / THF147859, detail

Though Clinton was a small village, Calvin Wood faced competition for customers—the Eagle Tavern was not the only tavern in Clinton. Along on the Chicago Road also stood the Eagle Hotel, operated by 27-year-old Hiram Nimocks and his wife Melinda. It appears that the Eagle Hotel accommodated boarders as well—seven men are listed as living there, including two of the town’s merchants. These men probably rented bedrooms (likely shared with others) and ate at a common table.

Moving On

In 1854, Calvin Wood decided that it was time for his five-year tavernkeeping “career” to draw to a close. He and Harriet no longer operated the Eagle Tavern, selling it to the next tavernkeeper. Initially, the Woods didn’t go far. In 1860, Calvin is listed in the United States census as living in Clinton as a retired farmer. Yet Calvin and Harriet Wood soon moved to Hastings, Minnesota, where Harriet’s daughters, now married, resided. There Calvin and Harriet would end their lives, Calvin dying in 1863 and Harriet the following year.

The Wood family tombstone in Brookside Cemetery. / THF148371

You can still pay Calvin a “visit” at Brookside Cemetery in Tecumseh, where he shares a tombstone with his first wife, children, his father, and his brother’s family. For Harriet? You’ll have to make a trip to Hastings, Minnesota.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources, and Lisa Korzetz, Registrar, for assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Eagle Tavern Happy Hour: Mint Julep Recipe

- Eagle Tavern Happy Hour: Maple Bourbon Sour Recipe

- Making Eagle Tavern's Butternut Squash Soup

- Eagle Tavern at its Original Site, Clinton, Michigan, February 2, 1925

1850s, 1840s, 19th century, restaurants, Michigan, hotels, home life, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, food, Eagle Tavern, by Jeanine Head Miller, beverages

What We Wore: Sports

A new group of garments from The Henry Ford’s rich collection of clothing and accessories has made its debut in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in our What We Wore exhibit. With spring here and summer on the horizon, this time it’s a look at garments Americans wore as they delighted in the “sporting life” in their leisure time.

By the 20th century, recreational sports were an increasingly popular way to get exercise while having fun. Most Americans lived in cities rather than on farms—and lifestyles had become less physically active. Many people viewed sports as a necessity—an outlet from the pressures of modern life in an urban society.

Bicycling

The easy-to-ride safety bicycle turned cycling into a national obsession in the 1890s. At the peak in 1896, four million people cycled for exercise and pleasure. Most importantly, a bicycle meant the freedom to go where you pleased—around town or in the countryside.

Women found bicycling especially liberating—it offered far greater independence than they had previously experienced. Clothing for women became less restrictive while still offering modesty. Cycling apparel might include a tailored jacket, very wide trousers gathered above the ankles, stockings, and boots. Specially designed cycling suits with divided skirts also became popular.

Women's cycling suit, 1895-1900 / THF133355

Columbia Model 60 Women's Safety Bicycle, 1898. Gift of Mr. & Mrs. H. Benjamin Robison. / THF108117

This 1895 poster for bicycle road maps offered a pleasant route for cyclists north of New York City. / THF207603

Young men and women enjoy cycling and socializing in Waterville, Ohio about 1895. Gift of Thomas Russell. / THF201329

Baseball

Baseball has long been a popular pastime—countless teams sprang up in communities all over America after the Civil War. During the early 20th century, as cities expanded, workplace teams also increased in popularity. Companies sponsored these teams to promote fitness and encourage “team spirit” among their employees. Company teams were also good “advertising.”

Harry B. Mosley of Detroit wore this uniform when he played for a team sponsored by the Lincoln Motor Company about 1920. Of course, uniforms weren’t essential—many players enjoyed the sport while dressed in their everyday clothing.

Baseball uniform (shirt, pants, stockings, cleats, and cap), about 1920, worn by Harry B. Mosley of Detroit, Michigan. / THF186743

Baseball glove and bat, about 1920, used by Harry B. Mosley of Detroit, Michigan. / THF121995 and THF131216

The H.J. Heinz Company baseball team about 1907. Gift of H.J. Heinz Company. / THF292401

Residents of Inkster, Michigan, enjoy a game of baseball at a July 4th community celebration in 1940. Gift of Ford Motor Company. / THF147620

Golf

The game of golf boomed in the United States during the 1920s, flourishing on the outskirts of towns at hundreds of country clubs and public golf courses. By 1939, an estimated 8 million people—mostly the wealthy—played golf. It provided exercise—and for some, an opportunity to build professional or business networks.

When women golfed during the 1940s, they did not wear a specific kind of outfit. Often, women golfers would wear a skirt designed for active endeavors, paired with a blouse and pullover sweater. Catherine Roddis of Marshfield, Wisconsin, likely wore this sporty dress for golf, along with the stylish cape, donned once she had finished her game.

Dress and cape, 1940–1945, worn by Catherine Prindle Roddis, Marshfield, Wisconsin. Gift in Memory of Augusta Denton Roddis. / THF162615

Golf Clubs, about 1955. Gift of David & Barbara Shafer. / THF186328

Woman putts on a golf course near San Antonio, Texas, 1947. / THF621989

Clubhouse at the public Waukesha Golf Club on Moor Bath Links, Waukesha, Wisconsin, 1948–1956. Gift of Charles H. Brown and Patrick Pehoski. / THF622612

Swimming

Swimming had become a popular sport by the 1920s—swimmers could be found at public beaches, public swimming pools, and resorts. In the 1950s, postwar economic prosperity brought even more opportunities for swimming. Americans could enjoy a dip in the growing number of pools found at public parks, motels, and in suburban backyards. Pool parties were popular—casual entertaining was in.

For men, cabana sets with matching swim trunks and sports shirts—for “pool, patio, or beach”—were stylish. The 1950s were a conservative era. The cover-up shirt maintained a modest appearance—while bright colors and patterns let men express their individuality.

Cabana set with short-sleeved shirt and swim trunks, 1955. Gift of American Textile History Museum. / THF186127

Advertisement for Catalina’s swimsuits—including cabana sets for men, 1955. / THF623631

In the years following World War II, the number of public and private swimming pools increased dramatically. Shown here in this June 1946 Life magazine advertisement, pool parties were popular. / THF622575

Swimming pool at Holiday Inn of Daytona Beach, Florida, 1961. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Moores. / THF104037

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

home life, by Jeanine Head Miller, popular culture, bicycles, baseball, What We Wore, sports, Henry Ford Museum, fashion

The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner

THF1882

THF1882With Greenfield Village reopening soon, you’ll find something new at the Noah Webster Home!

THF186494

We have reinstalled the formerly sparsely furnished Webster dining room to better reflect a more active family life that took place in the Webster household at the time of our interpretation: 1835.

THF107986

Noah and Rebecca Webster moved to their New Haven, Connecticut, home in their later years to be near family and friends, as well as the library at nearby Yale College. This painting of Noah dates from about this time.

THF119510

The Websters moved into their comfortable, newly-built home on Temple Street in New Haven in 1823. This portrait shows Rebecca Webster from about this time as well.

THF147812

New research and evolving historical perspective often lead us to reinterpret Greenfield Village buildings. So, furnishings change to reflect these richer or more accurate stories. This is what the Webster dining room looked like in 1947.

THF147776

In 1962, the Webster house was refurnished to showcase fine furnishings in period room-like settings—rather than reflecting a household whose elderly inhabitants started housekeeping decades before.

THF186507

In 1989, after meticulous research on the house and on the Webster family, the home was beautifully transformed, and its furnishings more closely reflected the Webster family’s lives.

THF53248

You could imagine the Websters living there. This is Rebecca Webster’s dressing room.

THF147817

Yet the dining room was sparsely furnished. The 1989 reinstallation suggested that the Websters were “in retirement” and “withdrawn from society,” and didn’t need or use this room much.

THF53258

The dining room was presented as a seldom-used space in the Webster home during the mid-1830s. This detail showed boots being cleaned in the otherwise unused room.

THF186509

Webster family correspondence and other documents paint a picture of a household that included not only family activities, but more public ones as well, during the 1830s and beyond.

THF236367

Daughter Julia Goodrich and her family lived down the street and were frequent visitors. The Webster house appears at far right in this photo of Temple Street taken in the 1920s.

THF174984

Webster children and grandchildren who lived farther away came for extended visits. Daughter Eliza Jones and her family traveled from their Bridgeport, Connecticut, home for visits.

THF186515

At times, some Webster family members even joined the household temporarily. They could stay in a guest room in the Webster home.

THF204255

Webster’s Yale-attending grandsons and their classmates stopped in for visits and came to gatherings. This print shows Yale College—located not far from the Webster home—during this time.

THF133637

The Webster family home was also Noah’s “office.” He had moved his study upstairs in October 1834, met there with business associates and students.

THF53243

Guests—including visiting clergymen, publishing associates, Yale faculty, and political leaders—would have called at the house or would have been invited to gatherings in the home. This is the Webster parlor.

THF186495

To help reflect the active family life that took place in the Webster household in 1835, the new dining room vignette suggests members of the extended Webster family casually gathering for a meal.

THF186496

The room’s arrangement is deliberately informal, with mismatched chairs. Hepplewhite chairs that are part of the dining room set are supplemented by others assembled for this family meal.

THF186497

A high chair is provided for the youngest Webster grandchild.

THF186498

The grandchildren’s domino game was quickly set aside as the table was set and three generations of the family began to gather.

THF186500

The dining room furnishings, like those in the rest of the home, reflect a household whose elderly inhabitants started housekeeping decades before. The Websters would have owned most of their furniture, tableware, candlesticks, and other items for decades. The Connecticut-made clock on the mantel would have been a bit newer, since it dates from 1825–1835.

THF186499

But the Hepplewhite style chairs—no longer in fashion—would have been purchased more than 30 years before.

THF186501

The early 1800s Chinese export dishes would have likely been bought decades before. Quite fine and fashionable when new, the sturdy dishes would have survived to be used at everyday meals and for family gatherings many years later.

THF186503

The Websters would have acquired other furnishings more recently--including newly available whale oil lamps, which provided brighter lighting than candles. In coastal New Haven, whale oil was readily available.

THF186505

Stylish curtains of New England factory-made roller-printed cotton fabric are gracefully draped over glass curtain tiebacks and decoratively arranged.

THF186506

Do stop by the Noah Webster Home when Greenfield Village opens this spring and see what the Websters are having for dinner as they “gather” with their children and grandchildren! And for even more Village building makeover stories, see also this recent post from Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life Donna Braden.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life and Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Prototype Eames Fiberglass Chair, circa 1949

- Arts and Crafts Furniture Making in West Michigan: The Charles Limbert Company of Grand Rapids and Holland

- Creatives of Clay and Wood

- Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Estate

Connecticut, 19th century, 1830s, 21st century, 2020s, Noah Webster Home, home life, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, furnishings, food, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Charles Sable, #THFCuratorChat, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Jeanetta Holder with Her Indianapolis 500 Quilt Made for Bobby Unser, 1975-1980 / THF78732

On May 30, 1932, the day that Jeanetta Pearson Holder was born in Kentucky, race cars sped around the track at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway about 250 miles to the north. The timing of Jeanetta’s birth was certainly a hint of things to come: she would grow up with a passion for auto racing, and, as an adult, become that sport’s “Quilt Lady.”

For four decades, Jeanetta combined her love of auto racing and her sewing talents to create unique quilts for winners of the Indianapolis 500 and other auto races.

Dale Earnhardt is wrapped in pride and his quilt after the 1995 Brickyard 400 race at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. / THF78819

A Love for Racing, A Talent for Sewing

As a little girl growing up on a Kentucky farm, Jeanetta made her own small race cars out of tobacco sticks and lard cans which she “raced everywhere [she] went.” Jeanetta’s childhood creative streak soon extended to sewing. She began to make clothes for her doll—and her pet cat. By the time she was 12, Jeanetta began sewing quilts, filling them with cotton batting from cotton she grew herself.

Jeanetta was clearly “driven.” When she didn’t have a car in which to take her driver’s license test, the teenager borrowed a taxicab. About this same time, Jeanetta started going to the race track. Soon 20-year-old Jeanetta was speeding around an oval dirt track at the wheel of a 1950 Hudson at Beech Bend Park in Warren County, Kentucky. In the early 1950s, women drivers were uncommon—and so was safety equipment. Jeanetta was dressed in a t-shirt and blue jeans for these regional races.

Continue Reading

Indiana, 20th century, women's history, racing, race car drivers, quilts, making, Indy 500, cars, by Jeanine Head Miller

A Quilt with a Cause

Nude is Not a Color quilt, made by Hillary Goodwin, Rachael Dorr, and contributors from around the world, 2017. / THF185986

Nude is Not a Color quilt, made by Hillary Goodwin, Rachael Dorr, and contributors from around the world, 2017. / THF185986We often associate quilts with warmth and creativity. They can also make statements —serving as banners advocating a cause.

For nearly 200 years, American women have used needle and thread—once the only medium available to them—to express opinions, raise awareness, and advocate for social change. Women gathered in homes and in their communities to create quilts supporting causes like abolition, voting rights for women, and war relief.

This striking quilt, Nude is Not a Color, was created in 2017 by a worldwide community of women who gathered virtually to take a stand against racial bias. Learn more about the quilt below, and see it for yourself on exhibit as part of What We Wore in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, from March 11 through April 18, 2021.

The Quilt’s Story

In 2014, a clothing brand that sewist and blogger Bianca Springer of Pearland, Texas, had publicly supported introduced a new line of pale beige garments called Nude—a name long used by the fashion and cosmetic industries for products like hosiery and lipstick. Bianca took action. She contacted the company, thinking that the name was perhaps an oversight —reminding them that “nude” is a state of undress, not a color. And that the shade they chose as “nude” reflected only people of lighter skin tone—thus marginalizing people of color. Bianca’s perspective was repeatedly dismissed by company officials as overblown and irrelevant. She felt excluded and invisible.

Quiltmaker Hillary Goodwin of Auburn, California—also a fan of the company's clothing designs—wanted to stand in solidarity with her friend Bianca, and with other people of color. Together they decided to make a statement in fabric. Through Instagram, Hillary asked quilters to create a shirt block in whatever color fabric they felt best represented their skin tone, or that of their loved ones. Twenty-four quilters responded, from around the United States and around the world, including Canada, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, and Australia. Hillary then combined these shirt blocks with an image of Bianca wearing one of the “Nude” brand garments—creating this motif of a woman of color clothed in many shades of “nude.” Rachael Dorr of Bronxville, New York, then free-motion machine-quilted the completed quilt top.

More people became aware of the company’s bias and lent their voices to the issue, demanding change—and the brand eventually altered the name of the garment collection. A global community of women, willing to use their talent and voices to take a stand against racism, made a difference.

Quilt Contributors

*Designed and constructed by Hillary Goodwin, Auburn California

*Design assistance by Robin King, Auburn, California

*Paper-pieced shirt pattern designed by Carolyn Friedlander, Lake Wales, Florida

*Shirt blocks contributed by:

- Carmen Alonso, Oviedo, Spain

- Agnes Ang, Thousand Oaks, California

- Berene Campbell, North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

- Kirsty Cleverly, Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia

- Silvana Pereira Coutinho, Brazil

- Anne Eriksson, Egmond aan den Hoef, The Netherlands

- Hillary Goodwin, Auburn, California

- Rebecca Green, United Kingdom

- Lynn Carson Harris, Chelsea, Michigan

- Phoebe Adair Harris, Chelsea, Michigan

- Krista Hennebury, North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

- Sandra Johnson, Orange, California

- Chawne Kimber, Easton, Pennsylvania

- Tamara King, Portland, Oregon

- Alexandra Ledgerwood, Kansas City, Missouri

- Maite Macias, Oviedo, Spain

- Nicole Neblett, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Krishma Patel, Carteret, New Jersey

- Amy Vaughn Ready, Billings, Montana

- Sonia Sanchez, Oviedo, Spain

- Rachel Singh, Seattle, Washington

- Michele Spirko, Amherst, Massachusetts

- Bianca Springer, Pearland, Texas

- Jess Ziegler, Adel, Iowa

*Free-motion machine quilted by Rachael Dorr, Bronxville, New York

Maker Stories

The makers each had a unique story to tell—below are some of their insights.

“Hearing of this encounter was an eye opener for me as a white woman. How would I feel if I had to explain to my daughter that her skin tone was not the “standard”? How many other ways does my white privilege benefit me without me acknowledging it? How could I help stand in solidarity with my friend?” —Hillary Goodwin, Auburn, California

“The … collection featured a non-diverse group of models wearing beige fabrics classified as "nude.” My "nude" skin is not beige and the use of the term made it clear they did not have me in mind… the color … only fits the white majority, signals white supremacy and marginalizes people of color… With the conceptualization of the quilt, the issue went from commiseration and emotional processing of systemic and overt racism, to a broader statement of activism.” —Bianca Springer, Pearland, Texas

“Although I considered myself a non-racist white person, I am not, of course, and I had never really given any thought to what it felt like to live life in a skin color that was not white. I credit my participation in the making of this quilt as the beginning of my slow and never-ending quest to be an anti-racist ally and to use the unearned privilege afforded me solely by my skin color to help bring some long overdue justice to this country.” —Tamara King, Portland, Oregon

"We are a group of three friends, we met through sewing… We live in Asturias, a small region in the north of Spain, that has traditionally been a land of emigrants … concepts such as "white privilege,” "black lives matter" … "segregation" ... sound very foreign to us… Choosing the fabrics for our "shirts" was … a surprise. How different we all are! And then seeing all the "shirts" … Mind blowing!” —Sonia Sanchez (along with friends Carment Alonso and Maite Macias), Oviedo, Spain

“I hope that the message of the quilt reaches a lot of people and, at least, has them thinking.” —Kirsty Cleverly, Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia

“I grew up in the South at a time when bare legs were scandalous and pantyhose were expected on any good young lady. The color options were black, suntan, and nude. It never quite made sense why nude was so white and why my own predominant skin tone was equated to someone's suntan. Why would white skin be the default in such a creative industry as fashion? Unfortunately the industry still adheres to these color naming schemes, which only serve to make sure I know that I am Other in this society.” —Chawne Kimber, Easton, Pennsylvania

“My daughter, Phoebe, who was 10 at the time, often spent time in my sewing room with me and loved to help choose fabrics for my projects. I had Phoebe help choose a fabric that matched my skin tone. She noticed that HER skin matched a different color and wanted to contribute a block too. I loved that teachable moment we had in the sewing room… This moment contributed to her journey of looking at how people are the same, how people are different, representation, and fighting for social justice as she is now doing in her teens.” —Lynn Carson Harris, Chelsea, Michigan