Posts Tagged ford family

Henry Ford and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Concert in the Ford Symphony Gardens, Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1934. THF212561

For the past 24 years the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and The Henry Ford have teamed up for Salute to America, our annual concert and fireworks celebration in Greenfield Village. But the affiliation between the DSO and our organization goes back much farther than that.

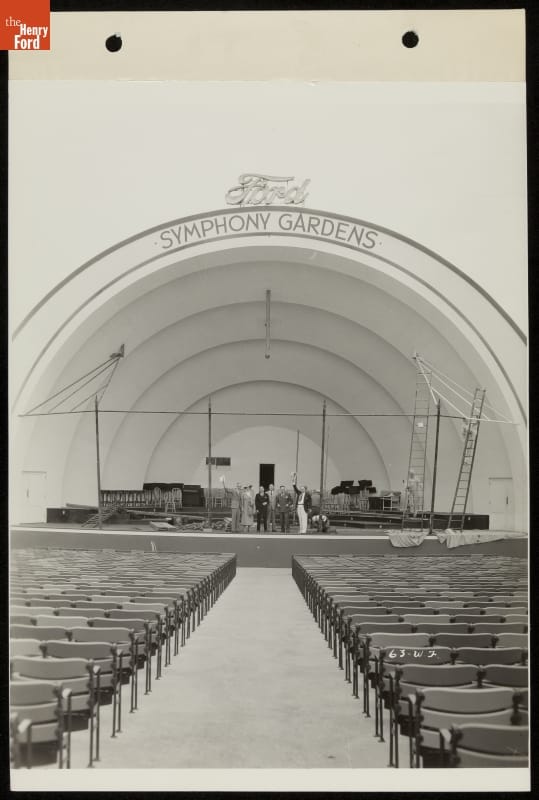

Preparing for a Performance in Ford Symphony Gardens, Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1934. THF212547

The connection dates back to the 1934 Chicago World's Fair, A Century of Progress International Exposition. Ford Motor Company’s exhibits were housed in the famous Rotunda building and also included the Magic Skyway and the Ford Symphony Gardens. The large amphitheater of the Symphony Gardens hosted several musical and stage acts, including the DSO, who Ford sponsored for 150 concerts over the course of the year. The symphonic notes proved so popular that Henry and Edsel Ford decided to launch a radio program featuring selections from symphonies and operas - the Ford Sunday Evening Hour. The weekly program played to over 10,000,000 listeners each broadcast over the CBS network (the same network that now presents The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation). Musical pieces were played by DSO musicians under the name Ford Symphony Orchestra, a 75-piece ensemble, and were conducted by Victor Kolar, the DSO’s associate director, for the first few years of the show. Pieces ranged from symphony classics including works by Handel, Strauss, Liszt, Wagner, Handel, Puccini, Bizet, and Tchaikovsky (including, of course, the 1812 Overture), to some of Henry Ford’s favorite traditional and folk songs like Turkey in the Straw and Annie Laurie, and even included popular tunes such as Night and Day by Cole Porter.

Each broadcast featured guest stars, soloists, and singers such as Jascha Heifetz, Grisha Goluboff, Gladys Swarthout, Grete Stükgold, and José Iturbi. The broadcast performances were open to the public for free, first at Orchestra Hall from 1934-1936, and then at the Masonic Temple 1936-1942. The show ran from 1934-1942, September-May with 1,300,000 live attendees and countless radio listeners tuning in.

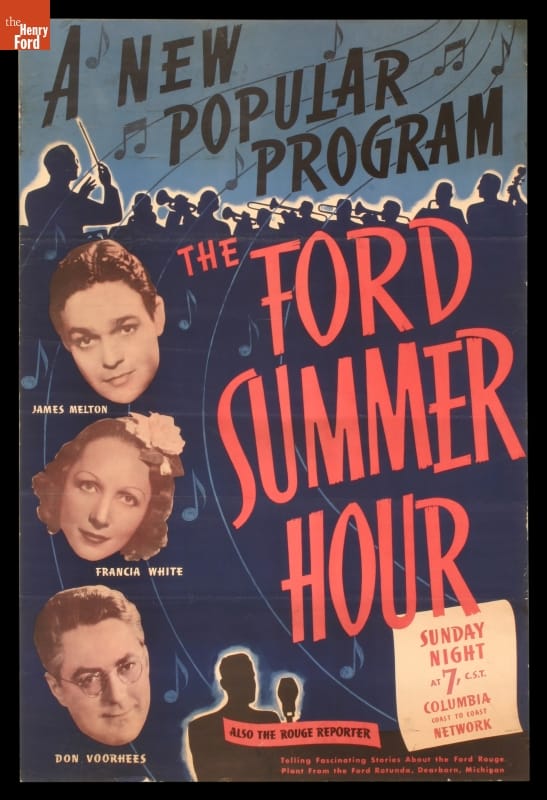

Advertising Poster, The Ford Summer Hour, 1939. THF111542

Salute to America is our summer music tradition, and listeners in 1939 must have wanted some summer-themed music as well because Henry and Edsel started the Ford Summer Hour that year. Like the winter program, it was broadcast each Sunday evening on CBS, from May to September and featured a smaller 32-piece orchestra, again mostly made up of DSO musicians. Guest stars and conductors appeared, such as Don Voorhees, James Melton, and Jessica Dragonette.

The show included music from Ford employee bands like the River Rouge Ramblers, Champion Pipe Band, and the Dixie Eight. This was a program of lighter music, popular songs, and tunes from musical comedies and operettas. Apparently not everyone appreciated the lighter fare; a letter from a concerned listener stated:

“...as the strains of the trivial program of Ford Summer Show float into my room, I am moved to contrast them with the fine programs of your winter series, and to wonder why the myth persists that in hot weather the human mentality is unequal to the strain of listening to good music. Pardon me while I switch my radio to station WQXR which has fine music the year round.”

Strong words from the listening public, though apparently not the majority as the summer program rivaled the winter program with about 9,000,000 listeners per broadcast. The Ford Summer Hour, broadcast from the Ford Rotunda, only ran three seasons, but played a wide range of music for listeners such as Heigh Ho from Snow White, Dodging a Divorcee, selections from Carmen, Oh Dear, What Can the Matter Be, and One Fine Day from Madame Butterfly.

Both programs ceased by 1942 with the opening of World War II. Henry Ford II tried to bring back the Ford Sunday Evening Hour in 1945, broadcasting the same type of music by DSO musicians, but times and tastes had changed and the program was discounted after the first season.

Kathy Makas is a Benson Ford Research Center Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford. To learn more about the Ford Sunday Evening Hour or Ford Summer Hour, visit the Benson Ford Research Center or email your questions to us here.

Greenfield Village, events, Salute to America, by Kathy Makas, Ford Motor Company, Edsel Ford, Ford family, radio, world's fairs, Michigan, Henry Ford, music, Detroit

You could argue that one of the most visible buildings in Greenfield Village is Martha-Mary Chapel, standing as it does at the end of the Village Green, with its columns in front and high steeple. However, unlike many of the other buildings in the Village, the Chapel is not a historic building that was moved from elsewhere, but was built in the Village in 1929. Henry Ford wanted to recreate a typical village green and therefore had the Chapel (a characteristic building for a green) built, and named it after both his own mother, Mary Litogot Ford, and his wife Clara’s mother, Martha Bench Bryant. Some of the fixtures on the building came from Clara Ford’s childhood home, adding another layer of personal resonance. We’ve just digitized more than 100 images of the Chapel taken over its nearly 90-year history, including this classic shot from 1935—browse them all by visiting our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Clara Ford, Henry Ford, Ford family, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl

Cooking with Clara Ford

Clara Ford reminiscing over her first cookbook, the Buckeye Cookbook, at the Women’s City Club, 1949

“I don’t think Mrs. Ford had any outstanding hobby outside her gardening, except possibly recipes” – Rosa Buhler, maid at Fair Lane.

Clara certainly seemed to enjoy her recipes, from Sweet Potato Pudding to Corned Tongue, Clara collected hundreds of recipes. Some were in the form of cookbooks, some typed up, others cut out of magazines or newspapers, but the majority of them were handwritten, either by Clara or the many friends she gathered recipes from.

By the time the Fords moved to Fair Lane, Clara probably wasn’t cooking much from the Buckeye Cookbook her mother gave her when she married as the household staff now included a cook, but Clara never stopped searching out new recipes to try. According to Buhler, “Mrs. Ford would come down every day to talk over the day’s menu. She always saved recipes from cookbooks or the newspaper.” Clara was also very particular about her food, which led to a high turnover in cooks, so when there wasn’t a cook the other servants had to prepare the meals. John Williams, the Fair Lane houseman (and occasional cook) remarked that “Mrs. Ford had a lot of good cookbooks. Sometimes when I was in the kitchen, she would come out and say, ‘John, I found a good recipe. Sometime we’ll try it.’” Everywhere she went, Clara would pay close attention to the food and would frequently ask hostesses for their recipes. Buhler remembered when the Fords would visit Georgia, “every once in a while they’d spring something new on her in the way of Southern cooking. That intrigued her, and she’d ask about it. She’d probably get the recipe from the lady who served it, and she’d want her cook to try it.” There’s plenty of correspondence between Clara and her friends and acquaintances swapping recipes and menu ideas. Clara responded to one such letter from Charlotte Copeland which included a recipe for “Tongue en Casserole” saying, “thank you so much. I do love recipes from friends that have tried them,” and reciprocated with a recipe of her own. In her collection are recipes from Mrs. Ernest Liebold (wife of Henry Ford’s secretary), Mrs. Gaston Plantiff (wife of another Ford associate), and there’s even a recipe for “Mr. Burroughs’ Brigand Stake” (possibly from the famous Vagabond naturalist himself).

While Henry preferred very plain foods, Clara liked richer fare; cream sauces, butter, and lots of spices. She also preferred the traditional English cuisine and style of cooking of her mother’s family. Not a few of the servants questioned the wisdom of the English methods, and as noted above many cooks came and went at Fair Lane. Buhler said that, “Mrs. Ford stuck to the old-fashioned ways, for instance, plum pudding for Christmas. We always had to have it cooked in a cloth and though it always turned out to be a failure, the very next Christmas we had to do the very same thing over.” Not all the traditional recipes resulted in less than satisfactory results however, John Williams spoke of one particular recipe he became expert at, “Mrs. Ford had a favorite recipe that she taught me how to make. It was her mother’s recipe. The crust was made with sour cream, salt and soda, and the apples were sliced and put in a pie plate. This crust was spread over the top very thinly which made it very light….After it was baked, you would turn it on a platter that it was to be served on, and then you would add your sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg after it was cooked. It made a very delicious pie. Any time any cook was hired, I would have to show them that recipe,” though he did say “In my way of thinking, you could make a two-crust pie much quicker than you could make this.”

While Henry preferred very plain foods, Clara liked richer fare; cream sauces, butter, and lots of spices. She also preferred the traditional English cuisine and style of cooking of her mother’s family. Not a few of the servants questioned the wisdom of the English methods, and as noted above many cooks came and went at Fair Lane. Buhler said that, “Mrs. Ford stuck to the old-fashioned ways, for instance, plum pudding for Christmas. We always had to have it cooked in a cloth and though it always turned out to be a failure, the very next Christmas we had to do the very same thing over.” Not all the traditional recipes resulted in less than satisfactory results however, John Williams spoke of one particular recipe he became expert at, “Mrs. Ford had a favorite recipe that she taught me how to make. It was her mother’s recipe. The crust was made with sour cream, salt and soda, and the apples were sliced and put in a pie plate. This crust was spread over the top very thinly which made it very light….After it was baked, you would turn it on a platter that it was to be served on, and then you would add your sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg after it was cooked. It made a very delicious pie. Any time any cook was hired, I would have to show them that recipe,” though he did say “In my way of thinking, you could make a two-crust pie much quicker than you could make this.”

- Clara appears to have had a sweet tooth, the majority of the recipes fall into the dessert category. A variety of cakes, cookies, puddings, and pies appear in her collection with flavors from chocolate and butterscotch to blackberry. Many of the entrees and sides were vegetarian, reflecting on Henry’s preferences for lighter fare and Clara’s love of gardening, there were even recipes for alcoholic beverages (something Henry hardly ever consumed). In all there are recipes ranging from Green Mango Pie and Blueberry Dumplings, to Suet Pudding and Frizzled Oysters. If you’re looking to “Coddle an Egg” or find a recipe “For Crusty Top to Soufflé” Clara Ford has a recipe in her collection for you. The only ingredient that seems to be notable for its lack of representation in the collection is the soybean, only one recipe “25% Soybean Bread” features Henry’s favorite legume. John Thompson, butler at Fair Lane noted “Mr. Ford tried to convince Mrs. Ford she should have an interest in soybean products, but she never did. She never thought much of them...Mr. Ford used to eat soybean soup every day during the period he was interested in those experiments…Mrs. Ford didn’t go for this soup.” Though they could both agree on wheat germ, one of their favorite cookies being Model T’s, and according to Ford employee A.G. Wolfe, “You haven’t had anything until you have had a Model T cookie!”

Learn more:

Ford family, Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, women's history, recipes, making, food, Clara Ford, by Kathy Makas, archives

Turn, Turn, Turn

As the story goes, William Ford traveled to Philadelphia for the Centennial Exposition in 1876. William, a farmer from Springwells Township in Wayne County, Mich., took a keen interest in the agricultural displays. One device struck him as particularly useful, a Stover Windmill, or as the Stover Wind Engine Company's advertisement called it, "Stover's Automatic Wind Engine." Continue Reading

Greenfield Village history, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Ford family, power, agriculture

Just Added to Our Digital Collections: 1952 Ferrari 212 Barchetta Images

Something that may not be widely known outside the museum world is how much collaboration and cooperation goes on between cultural heritage institutions. As an example, Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford, was recently approached by the Petersen Automotive Museum about a 1952 Ferrari 212 Barchetta originally given to Henry Ford II by Enzo Ferrari, now in the collections of the Petersen. The Barchetta served as one of the design inspirations for the 1955 Ford Thunderbird, and was exhibited from time to time in the past at special car shows in Henry Ford Museum. When our staff dug into our archives, they found more than two dozen vintage photographs of the car, including this shot showing the sleek lines of the vehicle from the side. We provided these images to the Petersen, which will enhance their curation of this fine vehicle, and in addition have posted them to our digital collections for anyone to access and enjoy.

If you’d like to know more about the Barchetta, you can watch an interview with Petersen chief curator Leslie Kendall and a road test of the car in this episode of Jay Leno’s Garage, or you can check out all of our digitized Barchetta images by visiting our collections website.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1950s, Ford family, digital collections, cars, by Ellice Engdahl

Detroit Industry Frescoes: The Backstory

The Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit exhibit will be on display at the Detroit Institute of Arts from March 15, 2015 through July 12, 2015. As a community partner for the exhibit, The Henry Ford has been digitizing selections from our collection that document Diego Rivera’s creation of the Detroit Industry frescoes and Diego and Frida’s time in Detroit. Below are links to six sets within our digital collections that bring some additional context to the exhibition.

Detroit Industry Frescoes: The Backstory

Edsel Ford funded the Detroit Industry frescoes, and Diego Rivera was inspired by the Ford Rouge Factory. As a result, Ford Motor Company, Edsel, Diego, and Frida became intertwined during the artists’ time in Detroit. This set features behind-the-scenes photographs of Diego, Frida, and others involved in the project; photos of Diego’s original drawings for the murals; a photograph taken by Ford Motor Company at Diego’s request; and correspondence between the DIA and Ford Motor Company about supplying glass and sand for the work.

20th century, 1930s, Michigan, Detroit, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, Ford family, Edsel Ford, Detroit Institute of Arts, by Ellice Engdahl, art

Who Cancelled Edsel Ford's Detroit Lions Season Pass?

Earlier this week we shared another set of items that were recently digitized for our online collections: football artifacts to supplement our latest traveling exhibit, Gridiron Glory: The Best of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. One of those items is Edsel Ford’s 1934 season pass to home games of the Detroit Lions, which is actually on display inside the exhibit. In the picture of the pass you'll see that "Cancelled" is written in one of the top corners. After we shared the photo on Twitter yesterday Dave Birkett sent us this Tweet:

Anyone have any idea why "cancelled" would be written on that pass? @thehenryford

— Dave Birkett (@davebirkett) October 1, 2014

The explanation wasn't included in the online narrative for the pass and actually had several of us scratching our own heads - why was the pass cancelled? Thanks to Brian Wilson, Digital Processing Archivist at The Henry Ford, we found the answer. Here's Brian's report as he took a trip to our archives. - Lish Dorset Social Media Manager, The Henry Ford. Continue Reading

20th century, 1930s, sports, research, Michigan, Ford family, football, Edsel Ford, Detroit, by Lish Dorset, by Brian Wilson

It should come as no surprise, given the founder of this institution, that our digital collections already contain hundreds of items related to Henry Ford’s son, Edsel. We’ve just expanded this selection by digitizing some of Edsel’s childhood artwork. My personal favorite is this bear, made of brown thread stitched into paper and likely created when Edsel was between 5 and 10 years old, but other pieces include family portraits, highly geometric works, and slightly later, more sophisticated works. View these and other items related to Edsel Ford in our online collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Detroit, Michigan, 19th century, 20th century, 1910s, 1890s, Ford family, Edsel Ford, drawings, digital collections, childhood, by Ellice Engdahl, art

Edsel Ford's 1941 Lincoln Continental

Visitors to Henry Ford Museum will see a new vehicle in Driving America. Edsel Ford’s 1941 Lincoln Continental convertible is now in the exhibit’s “Design” section, located just behind Lamy’s Diner. The original Lincoln Continental, built between 1939 and 1948, is regarded as one of the most beautiful automobiles ever to come out of Detroit. It’s an important design story that we’re delighted to share.

The Continental’s tale began in the fall of 1938 as Edsel Ford returned from a trip to Europe. While overseas, Ford was struck by the look of European sports cars with their long hoods, short trunks and rear-mounted spare tires. When Ford got home, he approached Lincoln designer E.T. “Bob” Gregorie and asked him to create a custom car with a “continental” look. Using the Lincoln Zephyr as his base, Gregorie produced an automobile with clean, pure lines free of superfluous chrome ornaments or then-standard running boards. Continue Reading

1930s, 20th century, 1940s, luxury cars, Ford Motor Company, Ford family, Edsel Ford, design, convertibles, cars, by Matt Anderson

Jens Jensen (1860–1951) was a Danish-born landscape architect who did a large amount of design work for the Ford family and Ford Motor Company. This included Ford Motor Company pavilion landscaping for the 1933–34 Chicago World’s Fair, landscape design for multiple residences of Edsel Ford, and complete landscaping for Fair Lane, the Dearborn estate of Henry and Clara Ford. We’ve just digitized 29 blueprints from the Jens Jensen Drawings Series showing planting plans, grading and topographical plans, and water feature plans for the Fair Lane estate, such as this one for a bird pool. View all related material in our digital collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, Ford family, Clara Ford, home life, 20th century, 1920s, 1910s, Henry Ford, drawings, digital collections, design, by Ellice Engdahl