Posts Tagged 1960s

Man Who Sold First Mustang Reunited with Car 55 Years Later

1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One. THF90618

1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One. THF90618

Ford Mustang Serial Number 1 and Original Owner Captain Stanley Tucker, 1966. THF98053

More than 55 years ago, Harry Phillips sold Mustang Serial No. 1 to Stanley Tucker in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada.

The very first Mustang sold was a pre-production model only intended for display. It was meant to be sent back to Ford, and it took nearly two years for the car to be officially returned.

Harry Phillips and Mustang Serial No. 1, September 2019.

Thanks to a campaign spurred on by fellow Ford Mustang lovers, Mr. Phillips was reunited with that same car, in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, on Sept. 27, 2019. Hear his story of that landmark sale in 1964, and learn more about this important artifact: Stanley Tucker and Ford Mustang Serial Number One.

Continue Reading

Canada, Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1960s, Mustangs, Henry Ford Museum, Ford Motor Company, events, convertibles, cars

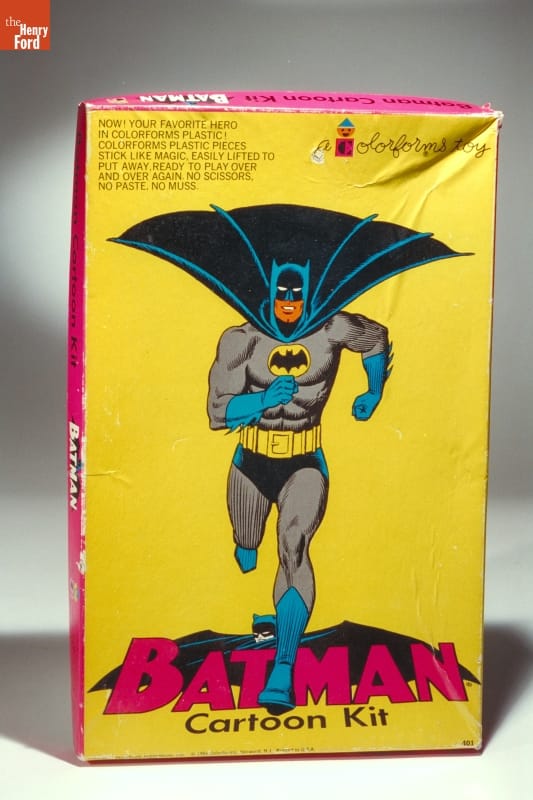

“Batman Cartoon Kit” Colorforms, 1966-68. THF 6651

It was the 1960s—the golden age of television. Some 95% of American homes boasted at least one TV. These were primarily black and white sets, as color TV was still out of the reach of many families. It’s hard to imagine now but there were only three channels at the time. Every year, the three networks (CBS, NBC, and ABC) vied for viewer ratings, shifting and changing shows and showtimes at two pivotal times during the television season—Fall and Winter.

As the Fall 1966 season unfolded, it became evident to TV viewers that something extraordinary was happening. Sure, there were the usual long-running sitcoms, like Green Acres, Petticoat Junction, and The Beverly Hillbillies. But change was in the wind. A new crop of programs emerged—colorful, fast-paced, poking fun at things that were supposed to be serious and exploring contemporary social issues.

Why the difference all of a sudden? Many of these shows were aimed at the youth audience, considered by this time an influential group of TV watchers. Others purposefully took advantage of the new color televisions. Sometimes show producers and creators were simply tired of the old formulas and wanted to break out of the box.

Let’s take a look at a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season—starting with the staid and true and working up to the wild and wacky—and see what all the hubbub was about!

Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Sunday, 7:30-8:30 p.m., NBC)

Snow Globe, “The Wonderful World of Disney,” 1969-79. THF174650

On Sunday nights since 1954, millions of Americans had tuned in to watch Walt Disney host his TV show, with a changing array of animated and live-action features, nature specials, movie reruns, travelogues, programs about science and outer space, and—best of all—updates on Walt Disney’s theme park, Disneyland. Since 1961, this show had been broadcast in color.

The 1966-67 season was particularly memorable because Walt Disney tragically passed away on December 15, 1966. But since the episodes had been pre-recorded, there was Walt still hosting them until April 1967. Viewers found this both comforting and disconcerting. Finally, after April, Walt was dropped as the host and, eventually, the show was retitled The Wonderful World of Disney. It ran with solid ratings until the mid-1970s.

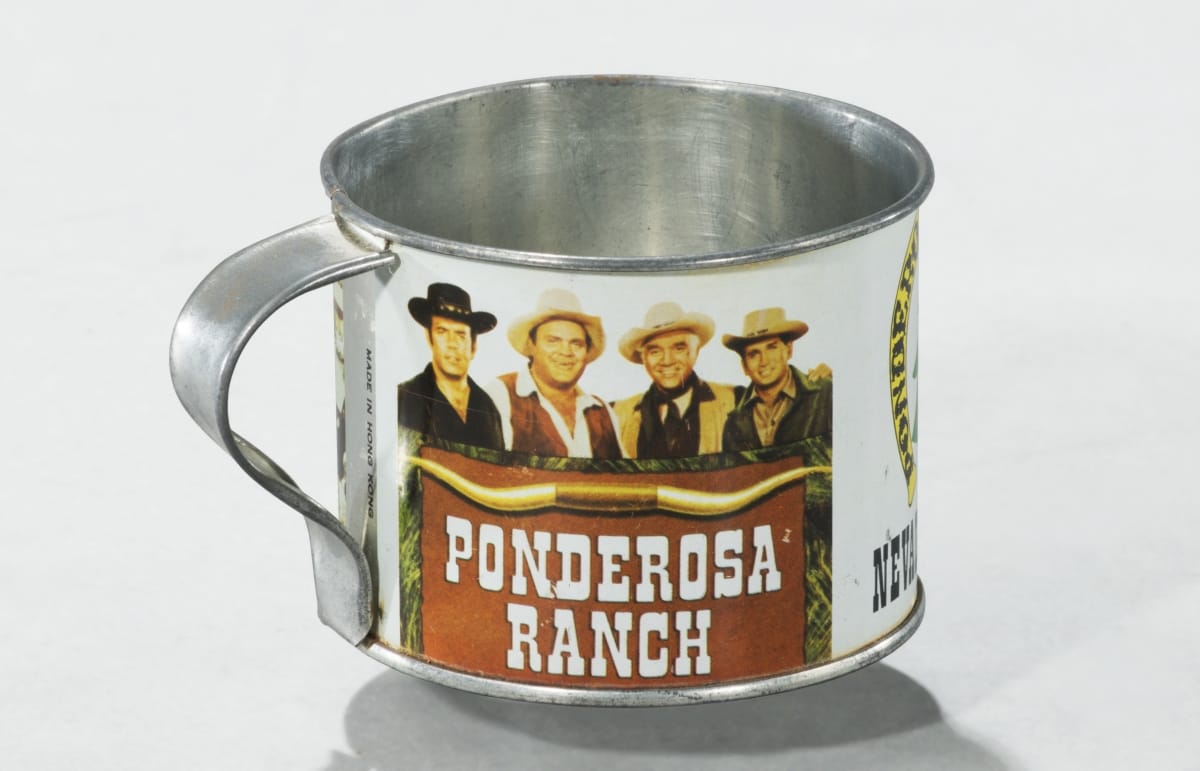

Bonanza (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m., NBC)

“Ponderosa Ranch” Mug, ca. 1970. THF174648

Viewership was high on NBC on Sunday nights at 9:00, as Bonanza was one of the most popular TV shows of all time. Running for 14 seasons and 430 episodes, this series about the trials and tribulations of widower Ben Cartwright and his three sons on the Ponderosa Ranch was an immediate breakout hit when it premiered in 1959, amidst a plethora of more run-of-the-mill prime-time westerns. Its popularity was primarily due to its quirky characters and unconventional stories—including early attempts to confront social issues. It was the first major western to be filmed in color and was the top-rated show on TV from 1964 to 1968. Bonanza ran until 1973.

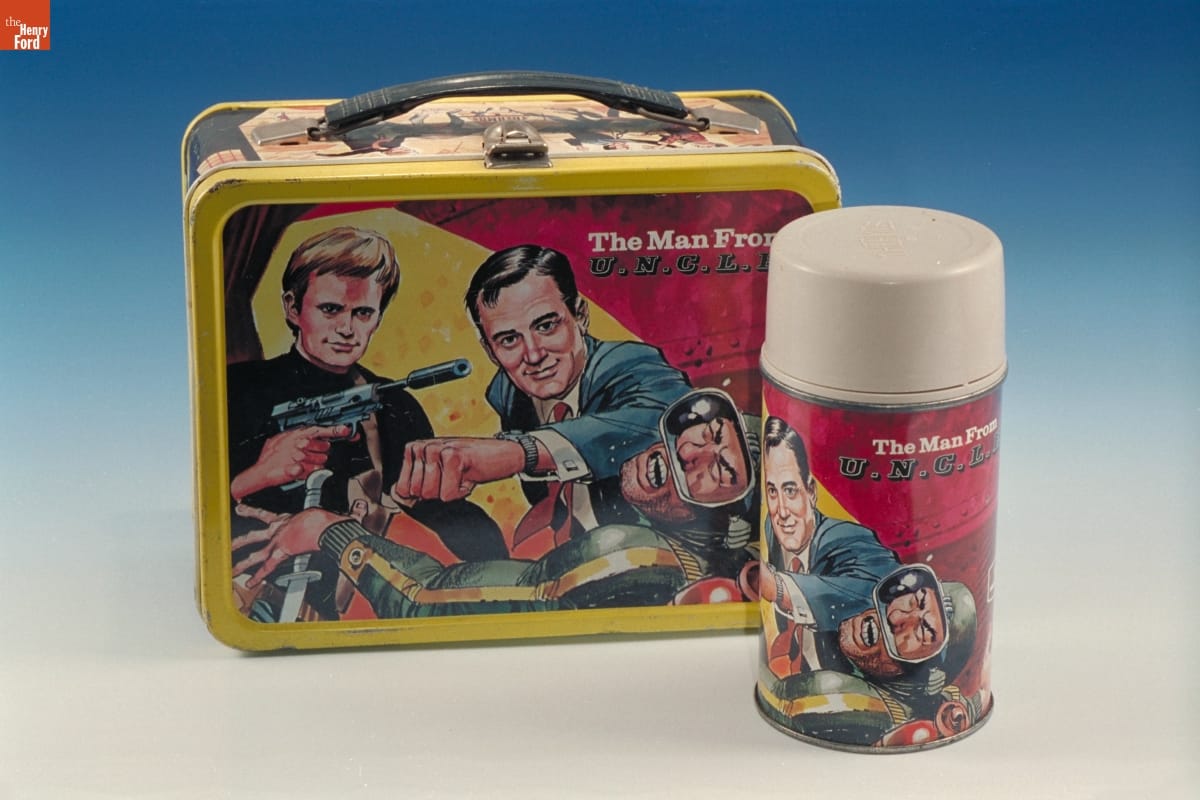

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (Friday, 8:30-9:30, NBC)

“The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” lunchbox and thermos, 1966. THF92303

Premiering in September 1964, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. took full advantage of the popularity of the spy genre launched by the James Bond film series. In fact, early concepts for it were conceptualized by Bond creator Ian Fleming. In this series, Napoleon Solo (originally conceived as the lone star) and Russian agent Ilya Kuryakin (added in response to popular demand) teamed up as part of a secret international counterespionage and law enforcement agency called U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement). Solo and Kuryakin banded together with a global organization of other agents to fight THRUSH, an international organization that aimed to conquer the world.

During this, the Cold War era, it was groundbreaking for a show to portray a United States-Soviet Union pair of secret agents, as these two countries were ideologically at odds most of the time. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was also known for its high-profile guest stars and—taking a cue from the Bond films—its clever gadgets. In 1966, this series won the Golden Globe for Best Television Program and, building upon its popularity, spun off into two related double-feature movies that year. Unfortunately, attempting to compete with lighter, campier programs of the era, the producers made a conscious effort to increase the level of humor—leading to a severe ratings drop. Although the serious plot lines were soon reinstated, the ratings never recovered. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was canceled in January 1968.

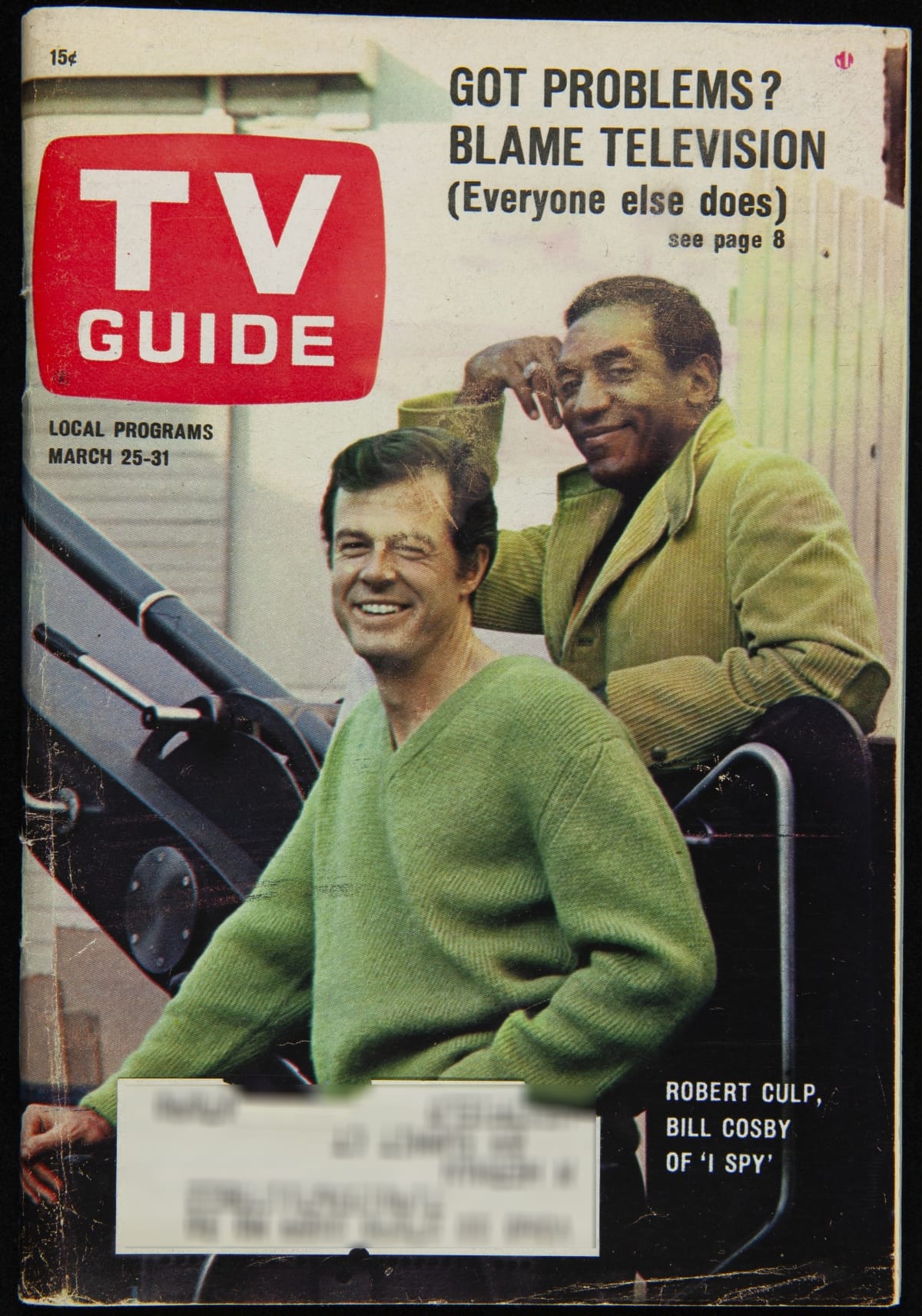

I Spy (Wednesday 10:00-11:00, NBC)

TV Guide featuring “I Spy” characters Robert Culp and Bill Cosby on cover, March 25-31, 1967. THF275655

One series that never opted for campy was I Spy, which starred Bill Cosby and Robert Culp playing two U.S. intelligence agents traveling undercover as international “tennis bums.” This series, which premiered in 1965, was also inspired by the James Bond film series and remained a fixture in the secret agent/espionage genre until cancelled in April 1968. I Spy, additionally a leader in the buddy genre, broke new ground as the first American TV drama series to feature a black actor in a lead role. It was also unusual in its use of exotic locations—much like the James Bond films—when shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. were completely filmed on a studio backlot.

I Spy offered hip banter between the two stars and some humor, but it focused primarily on the grittier side of the espionage business, sometimes even ending on a somber note. The success of this series was attributed to the strong chemistry between Culp and Cosby. Cosby’s presence was never called out in the way that black stars and co-stars were made a big deal of on later TV programs like Julia (1968) and Room 222 (1969).

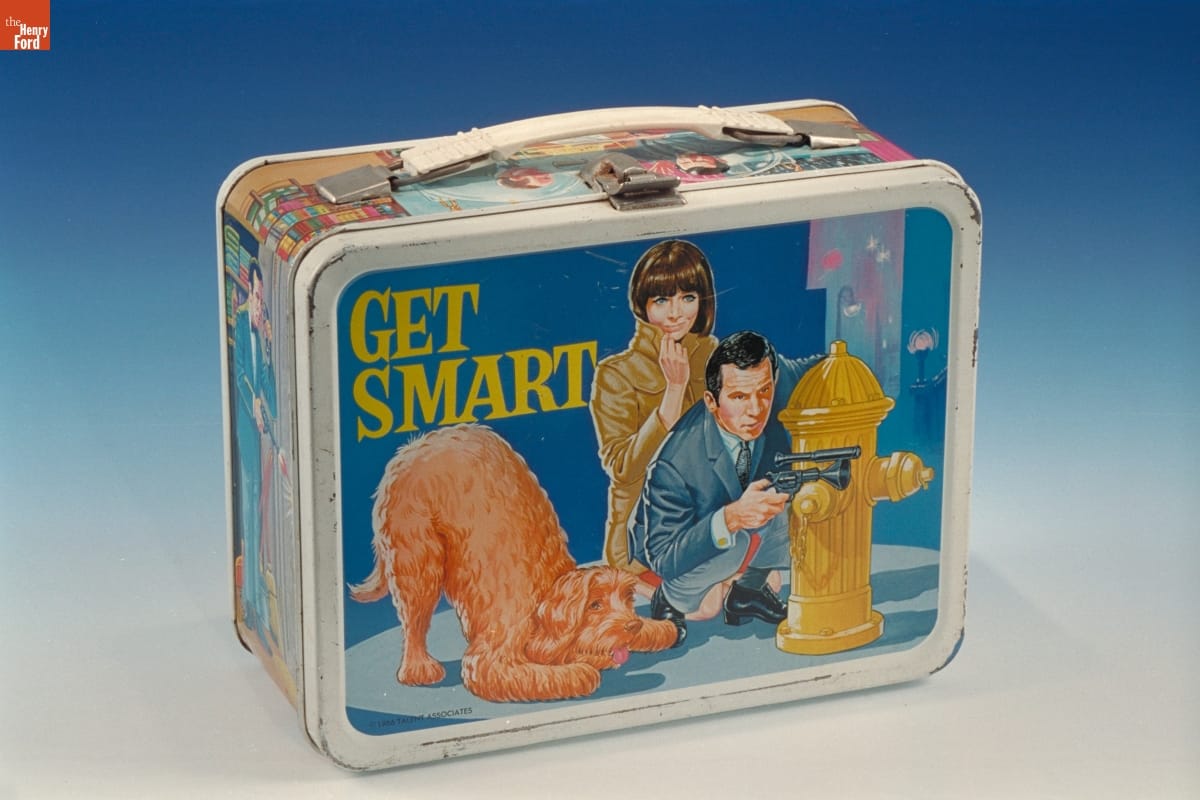

Get Smart (Saturday, 8:30-9:00 NBC)

“Get Smart” Lunchbox, 1966. THF92304

Premiering in September 1965, Get Smart was a comedy that satirized virtually everything considered serious and sacred in the James Bond films and such TV shows as I Spy and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Created by comic writers Mel Brooks and Buck Henry as a response to the grim seriousness of the Cold War spy genre, it starred bumbling Secret Agent 86—otherwise known as Maxwell “Max” Smart, along with supporting characters, female Agent 99 and the Chief. These characters worked for CONTROL, a secret U.S. government counterintelligence agency, against KAOS, “an international organization of evil.” Brooks and Henry also poked fun at this genre’s use of high-tech spy gadgets (Max’s shoe phone perhaps being the most memorable), world takeover plots, and enemy agents. Somehow, despite serious mess-ups in every episode, Maxwell Smart always emerged victorious in the end.

Get Smart was considered groundbreaking for broadening the parameters of TV sitcoms but was especially known for catchphrases like “Would you believe…” and “Sorry about that, Chief.” Despite a declining interest in the secret-agent genre, Get Smart’s talented writers attempted to keep it fresh until it was finally cancelled in May 1970.

Batman (Wednesday and Thursday, 7:30-8:00, ABC)

Toy Batmobile, 1966-69. THF174647

Bursting onto the scene in January 1966, Batman became an instant hit and took the country by storm. Batmania was in full swing by the Fall 1966-67 TV season. The series, based upon the DC comic book of the same name, featured the Caped Crusader (millionaire Bruce Wayne in his alter-ego of Batman) and the Boy Wonder (his young ward Dick Grayson in his alter-ego of Robin). These two crime-fighting heroes defended Gotham City from a variety of evil villains. It aired twice weekly, with most stories leaving viewers hanging in suspense the first night until they tuned in the second night.

This show successfully captured the youth audience, with its campy style, upbeat theme music, and tongue-in-cheek humor. Despite the fact that it verged on being a sitcom, the producers wisely left out the laugh track, reinforcing the seriousness with which the characters seemed to take the often absurd and wildly improbable situations in which they found themselves. The filming simulated a surreal comic-book quality, with characters and situations shot at high and low angles, with bright splashy colors and with sound effects, like Pow, Bam, and Zonk, appearing as words splashed across the action sequences on screen. The series was also replete with numerous gadgets and over-the-top props, with the Batmobile undoubtedly most memorable. Batman ran until March 1968, experiencing a significant ratings drop after its initial novelty faded.

Lost in Space (Wednesday 7:30-8:30, CBS)

“Lost in Space” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92298

Loosely based upon the story of the Swiss Family Robinson, this TV series depicted the adventures of the Robinson family, a pioneering family of space colonists who struggled to survive in the depths of space in the futuristic year of 1997—as the United States was gearing up to colonize space due to overpopulation. But the family’s mission was sabotaged, forcing the crew members to crash-land on a strange planet and leaving them lost in space.

The show had premiered in September 1965 as a serious science fiction series about space exploration and a family searching to find a new place for humans to dwell. But, in January 1966, pitted against Batman’s time slot, Lost in Space producers attempted to imitate Batman’s campiness with ever-more-outrageous villains, brightly colored outfits, and over-the-top action. The plots increasingly featured Robby the Robot and the evil Dr. Zachary Smith. Viewers and actors alike strongly disapproved of this shift. The show lingered on until March 1968.

The Monkees (Monday, 7:30-8:00, NBC)

“Monkees” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92313

Where other shows might have been lighthearted, campy, or tongue-in-cheek, The Monkees at times verged on pure anarchy. This series, which premiered on September 12, 1966, led off NBC’s prime-time programming every Monday night. It lasted only two seasons but during that time, its star shone brightly. The Monkees followed the experiences of four young men trying to make a name for themselves as a rock ‘n’ roll band, often finding themselves in strange, even bizarre, circumstances while searching for their big break. Aimed directly at the youth audience, the band members were characterized as heroes down on their luck while the adults were consistently depicted as the “heavies.”

The Beatles’ films A Hard Day’s Night and Help! inspired producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider to create not only a show about a rock ‘n’ roll band but also to adapt a loose narrative structure (each member of the Monkees was trained in improvisational acting techniques at the outset of the show) and the musical sequences or “romps” that appeared each week. The series built a reputation for its innovative use of avant-garde filming techniques like quick jump cuts and breaking the fourth wall (that is, having the characters directly address the TV viewers). A well-oiled marketing machine behind the show also ensured that strong tie-ins were maintained with teen magazines, merchandise, and live concerts.

The Monkees won the Emmy for best comedy series during its first, the 1966-67, season. However, backlash was inevitable among critics and older teenagers when the Monkees admitted that they did not play their own instruments—although they clearly played them in their live concerts and, in fact, eventually had a falling-out with network executives about this very issue. Though the show was cancelled in 1968, it experienced a huge revival among younger audiences through Saturday morning reruns and especially with the 1986 MTV Monkees Marathon. Remaining band members Micky Dolenz and Mike Nesmith still attract large audiences of intergenerational fans at their live concerts, while reruns of their TV shows continue to draw new audiences.

Star Trek (Thursday, 8:30-9:30 NBC)

“Star Trek” lunchbox, 1968. THF92299

When Star Trek premiered on September 8, 1966, science fiction shows were not very advanced—or even thought of very highly. Star Trek’s closest competitor, Lost in Space, offered only shallow plots, one-dimensional characters, and fake sets. No one could imagine at the time that this rather low-key show would become one of the biggest, longest-running, and highest-grossing media franchises of all time. This series traced the interstellar adventures of Captain James T. Kirk and his crew aboard the United Federation of Planets’ starship Enterprise, on a five-year mission “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Creator Gene Roddenberry, aiming the show at the youth audience, wanted to combine suspenseful adventure stories with morality tales reflecting contemporary life and social issues. So, to get by network scrutiny, he set the premise of the show in an imaginary future. With the freedom to experiment, he put in place one of TV’s first multiracial and multicultural casts and was able to explore through different episodes some of the most relevant political and social allegories on TV at the time. The stories were also considered exceptionally high quality for that era, involving believable characters with which viewers could both identify and sympathize. Unlike the gloomy predictions of most science fiction writings of the time, Roddenberry hoped that the futuristic utopia he created on Star Trek would give young people hope, that it would empower them to create a better future for themselves someday. Star Trek, with only modest ratings, lasted only three seasons. But it would go on to become a cult classic.

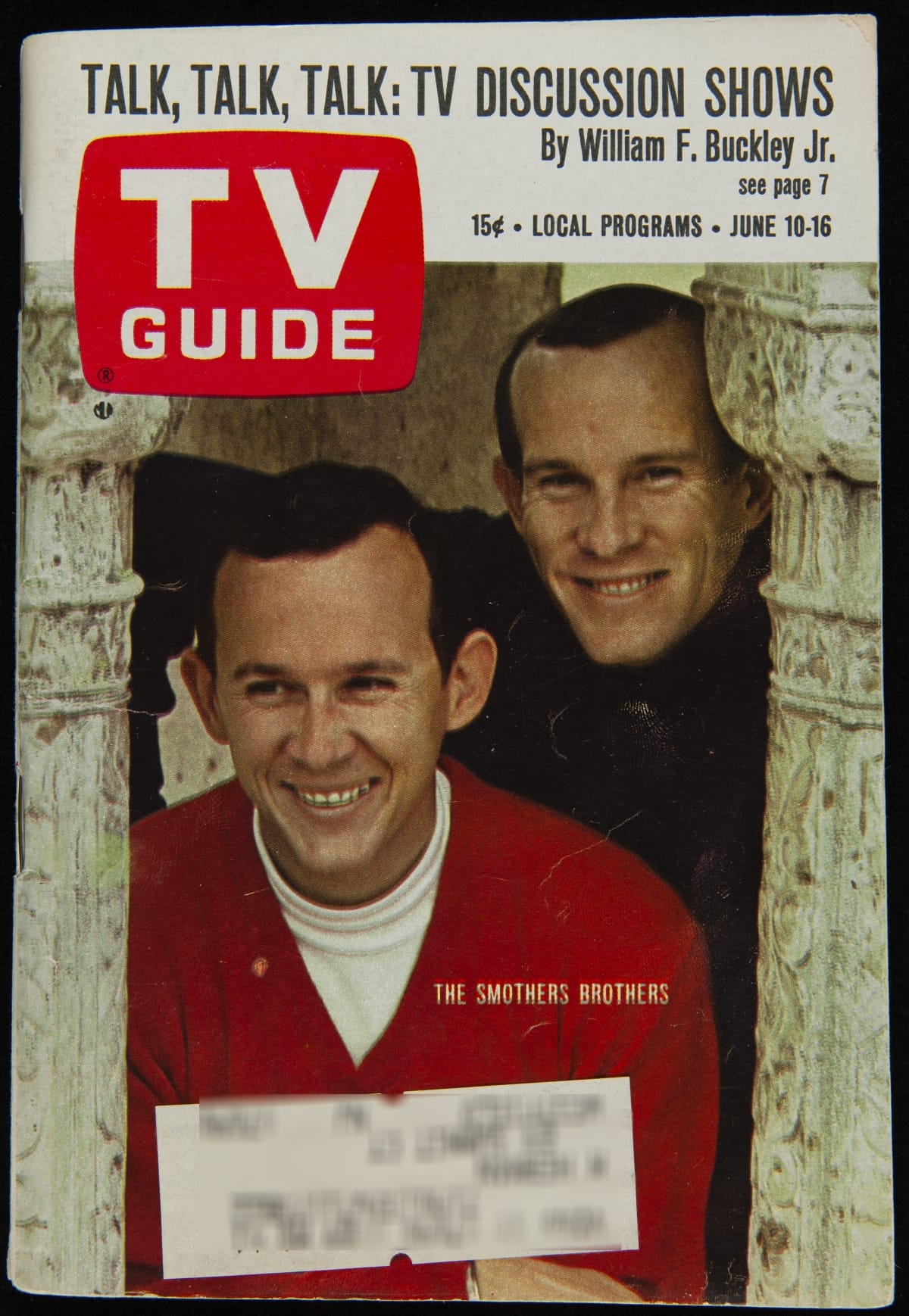

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m. beginning February 1967, CBS)

TV Guide featuring The Smothers Brothers on cover, June 10-16, 1967. THF275657

In Fall 1966, The Garry Moore Show, a variety show on CBS hosted by the aging radio and TV star, was no match when pitted against Bonanza—even with this, its first season in color. Network executives, at their wit’s end to try to attract viewership, decided the only way they could come up with a quick replacement was to substitute another variety show. In desperation, they landed on a simple variety series featuring the soft-spoken, clean-cut, non-threatening folk-music-playing Smothers Brothers. Considered a “young act,” an added bonus was that their show might capture the coveted youth audience. Little did they know what they were in for.

As the show evolved, the brothers not only became more politicized themselves but felt that they owed it to their young viewers to increase the show’s relevance, boldly addressing overtly divisive political and social issues. Their staff of young writers was only too happy to comply. Unfortunately, as a result, the brothers were continually at odds with the network censors until the show was finally cancelled after three seasons. In its continual conflicts with network executives, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour turned the variety show genre on its ear and paved the way for Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) and, in pushing TV’s all-out rebellion against the status quo, led an explosive charge that resulted in 1970s shows like All in the Family (1971).

These are but a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season. Some say that this was the greatest television season ever, a clear indication that TV had finally come of age. Because of shows like these, television would certainly never be the same again. And, come to think of it, neither would we!

Donna Braden, Curator of Public Life, was 13 years old during that memorable TV season and proudly wears her fan club button to every Monkees concert she still attends.

20th century, 1960s, TV, Star Trek, space, popular culture, music, Disney, by Donna R. Braden

Woodstock 1969

Estimate: 200,000 attendees. Over 400,000 showed up.

This flag was at Woodstock, too--a witness to this legendary event that reflected the 1960s counterculture movement’s quest for freedom and social harmony.

Flags like this one were provided to vendors, musicians, and technical crew to allow them access to the Woodstock Musical Festival grounds at Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm in upstate New York during the August 1969 event. They were to fly the flag from their vehicles or attach it to their booths.

Woodstock’s organizers--none of whom were over 27-- billed the event as “An Aquarian Exposition: Three Days of Peace and Music.” Held from Friday, August 15 and extending into the early morning of Monday, August 18, the music festival featured 32 iconic performers including Joan Baez, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, The Who, the Grateful Dead and Jimi Hendrix.

An Extraordinary Event Creates Enormous Challenges

There was a lot that went right with Woodstock. And many things that didn’t. The free-spirted and peaceful audience was filled with excitement and the musicians turned in electrifying performances. But the inexperienced organizers found their planning for this unprecedented event enormously inadequate--especially since they had to find a new venue only a few weeks before the concert.

The original location--an industrial park near Woodstock, New York--pulled out only a month and a half before the event. Fortunately, two weeks later Max Yasgur agreed to rent his Bethel, New York farm as the new venue. Nathan’s Hot Dogs--Coney Island’s famous vendor--pulled out when the location of the festival was moved. Two weeks before the concert, the organizers hired Food for Love, a trio with little experience in the food business. Larger food-vending companies hadn’t wanted to take on Woodstock--no one had ever handled food services for such a large event. Many were reluctant to put in the investment required--what if the festival didn’t draw enough of a crowd to make a profit?

Woodstock’s organizers had told the Bethel authorities that they expected no more than 50,000 people. As the event drew near, with 186,000 advance tickets sold, 200,000 concertgoers seemed a more likely estimate. The organizers then hurriedly tried to bring in more toilets, more water, and more food. Woodstock would ultimately draw an inconceivable number--over 400,000 concertgoers.

The roads around Bethel became jammed for miles with people heading to the concert. Many abandoned their vehicles and made the long walk in. The plugged roads would also make it extremely difficult to get needed supplies in.

The stage, parking lots, and concession stands were barely finished in time for the event. Concert-goers started arriving two days before--with the ticket booths and gates still uncompleted. Since people were able to just walk in, the organizers were forced to declare it a free concert--creating a monumental debt for them. (Though profits from a soundtrack and movie made from films of the Woodstock Festival would help bring down the debt.)

Most concertgoers arrived expecting to be able to purchase food. Food for Love concessions were quickly overwhelmed. Food became very hard to find. The Hog Farm, a West Coast commune hired to help with security, stepped in to help. They provided free food lines serving brown rice and vegetables--and granola. For some of the crowd, granola was nothing new. But for many it was. Granola would soon become the iconic food of the hippie era.

When the people of Sullivan County, where Yasgur’s farm was located, heard reports of food shortages, they gathered thousands of food donations, including 10,000 sandwiches, as well as water, fruit, and canned goods. Concertgoers who had brought their own food shared what they had with others.

It rained off and on during the event, interrupting or delaying performances--and creating a sea of mud. There weren’t enough receptacles for garbage. People waited an hour to use one of the portable toilets--then finding it an extremely unsanitary experience when they finally reached the front of the line.

Yet--despite unbelievably crowded conditions with wall-to-wall concertgoers, massive traffic jams, serious food shortages, no running water, no telephones, no electricity (except for the performance stage--and even that was sketchy at times), lack of sufficient restroom facilities, and the muddy quagmire--Woodstock was a place of communal peace and sharing for the three days of the festival. There were no reported incidents of violence among this gathering of over 400,000 people.

What Really Mattered

In the end, Woodstock wasn’t really about the food, the weather, or even the lack of creature comforts. For many who attended, Woodstock was about experiencing three days of legendary rock and roll music, being part of a peaceful community with hundreds of thousands of other young people, and immersing yourself freely and fully in the moment. (And, yes, free love and drugs in addition to rock and roll.) The Woodstock concert logo on this flag--the guitar and dove of peace--sums up the idealism of many of Woodstock’s concertgoers.

This flag’s faded and tattered appearance seems to suggest the logistical challenges of Woodstock. But it is more likely that its owner displayed this treasured keepsake for years after--the flag couldn’t fade this much or get this tattered in just three days. Instead, this flag attests to the eternal staying power of Woodstock as a cultural landmark for an entire generation of American youth--and for the nation.

Woodstock captured, vividly and indelibly, the spontaneity and free spirit of the counterculture movement of the 1960s--and its vision of freedom and social harmony that would ignite change in American society during the coming years.

Woodstock made history.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford

Woodstock has left its “mark”--not only in memory--but in archeology. Binghamton University’s archaeology team can really “dig it.” In 2018, they determined the location of the stage. By analyzing rocks and vegetation, they also located the area of the vendors’ booths, known as the Bindy Bazaar.

1960s, 20th century, New York, popular culture, music, by Jeanine Head Miller

One Giant Leap for Mankind

Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon Landing

The Space Race began in the 1950s, when both the United States and the Soviet Union attempted to launch ballistic missiles into outer space. Americans were surprised when the Russians beat them to it, launching the Sputnik I satellite in October 1957. But, when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited earth on April 12, 1961, Americans were downright shocked and not a little concerned. As a response, President Kennedy pledged to support a more aggressive space program than President Eisenhower had initiated before him.

On May 25, 1961, President Kennedy laid out a bold vision—that America should commit itself to landing a man on the moon “before the decade is out.” When astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin A. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. finally did set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969, many people considered it America’s finest hour.

Learn more about these artifacts below and then see them for yourself in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation during our pop-up exhibit now on display this summer.

This pictorial souvenir card depicts President Kennedy awarding NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal to America’s first astronaut, Navy Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr., on May 8, 1961, three days after his successful flight.

Souvenir Card, 1961. THF230121

Trading cards like these generated excitement among America’s youth about the achievements of the space program.

Topps Astronaut Trading Cards, 1963. THF230119

This “Destination Moon” mechanical bank commemorates astronaut John Glenn’s achievement of orbiting the earth in 1962.

Mechanical Bank, 1962. THF173785. (Gift of Raymond Reines, Dedicated to the Berzac Family)

Congress had to approve a massive budget increase for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to make Kennedy’s bold vision even a remote possibility.

Recruiting Advertisement for NASA, July 1962. THF230079

NASA’s Apollo 11 lunar mission captivated audiences watching the drama unfolding on television. Some even documented the events with their personal cameras.

Photographic Print, July 20, 1969. THF114240

Print made from slide, July 20, 1969. THF114242

Four months before real men landed on the moon, Snoopy appeared in a Peanuts comic strip as the “World Famous Astronaut” walking on the moon. This Peanuts Pocket Doll commemorates the 1969 moon landing.

Snoopy Toy, 1969. THF52. (Gift of CarolAnn Missant)

This coloring book included the Mercury, Apollo, and Saturn vehicles and astronauts, as well as some history of the space program.

Coloring Book, 1969. THF292641

Those who viewed the moon landing on TV on July 20, 1969, often have difficulty separating the historic occasion from the steadfast reporting of it by Cronkite—considered at the time “the most trusted man in America.”

Record Album, Narrated by Walter Cronkite, 1969. THF110908

The cover story for this issue contained an in-depth report of the historic moon-landing mission.

Time Magazine for July 25, 1969. THF230050. (Gift of the Estate of Dr. and Mrs. Martin A. Glynn)

This commemorative game, simulating the successful moon landing, had players collecting “moon rocks.”

Board Game, 1969-1975. THF91918

This phonograph record comprises a “recorded history of space exploration and the triumph of the lunar landing.”

Record Album, 1969. THF154908. (Gift of the Estate of Dr. and Mrs. Martin A. Glynn)

At the height of the Apollo space program, Marathon Gas Stations offered a series of promotional glasses featuring the Apollo 11, 12, 13, and 14 missions.

Tumblers commemorating Apollo 11 mission, circa 1969. THF175132 (Gift of Jan Hiatt)

The Apollo 11 astronauts took pieces of the 1903 Wright Flyer—the first practical heavier-than-air flying machine—on their 1969 mission to symbolize the incredible progress made in those 66 years. Here, Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong poses in front of the Wright brothers' home in Greenfield Village during a 1979 visit to The Henry Ford.

Photograph of Neil Armstrong in Greenfield Village, August 16, 1979. THF128246

The iconic image on this poster depicts Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon’s surface, a photo taken by Neil Armstrong.

Poster, 1969. THF56899

Read more

John Glenn, Space Hero

John F. Kennedy's Enduring Legacy

Donna Braden is Senior Curator & Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1960s, space, by Donna R. Braden

The Budd Company approached American Motors Corporation in 1962 with this concept car, which placed a sporty body and a powerful V-8 on an inexpensive Rambler Ambassador chassis. Fearing it would fail, AMC decided against putting the car into production. Two years later, Ford's Mustang became a massive hit using the same idea of a sporty body on an existing chassis.

Learn more about getting this car ready for the 30th Motor Muster, then see it for yourself June 15-16 in Greenfield Village.

conservation, collections care, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, car shows, Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, 1960s, Motor Muster, Greenfield Village, events, convertibles, cars

“Go Get ‘Em Tigers!”: 1968 World Series Champs

1968 World Series Official Souvenir Program, Tiger Stadium. THF 136034

It happened after the darkest year in Detroit’s history, 1967. What had started out as a police raid on an after-hours club early Sunday morning, July 23, 1967, escalated into five days and nights of uncontrolled violence, looting, and arson that left 43 people dead, 1,189 injured, and over 7,200 arrested. While civil unrest had occurred in many other cities before and during that summer, this event stood out as the largest of these uprisings to date.

The Detroit Tigers’ season ended on a dark note that year as well, with the team losing the pennant on the final play of the final game of the season.

When the baseball season returned in 1968, everyone wondered whether the violence of the previous summer would return. Detroiters expected the worst. But, when the Tigers started winning games—in dramatic fashion with new heroes emerging daily—people had something to look forward to. They rediscovered fun. And joy. And pride.

Exuding confidence from the start, the 1968 Detroit Tigers never lost a beat through the season. They clinched the American League pennant on September 17, 1968, with 103 wins and 59 losses—including a record-breaking 31 wins by pitcher Denny McLain.

1968 World Series poster, produced by Hudson’s and the Detroit Free Press, with a satirical caption referencing the popular 1963 film of that name.

Before the days of wildcard teams and inter-league division playoffs, the Tigers moved directly on to the World Series—pitted against National League (and defending World Series) champions, the St. Louis Cardinals. After a 3-1 deficit in the Series and the feeling of impending defeat, a masterful throw to home plate by Willie Horton in Game 5, a gutsy managerial decision to move centerfielder Mickey Stanley to shortstop, and three complete-game victories by pitcher Mickey Lolich (Games 2, 5, and 7) helped the Tigers stage a comeback during the last three games. On October 10, 1968, they clinched the Series. A city-wide celebration ensued, lasting until dawn. The memory has never quite been forgotten.

This marked the first time the Tigers had won a championship since 1945, only the third time in their history, and something they have not accomplished since 1984. This was also the final Major League Baseball World Series before the 1969 team expansion and the introduction of divisional play with the League Championship Series.

1968 World Series Souvenir Bumper Sticker, a supplement in the Detroit News. THF289559

As the donor of this bumper sticker (who was in eighth grade at the time) recalled, “Though I didn’t follow sports, I knew about the World Series, of course, and was SO proud that our hometown team would be participating. This was such a big thing that we students were allowed to watch the final game on a television rolled into our classroom (at Sacred Heart in Roseville, Michigan). That kind of thing very rarely happened—in fact, this is the only time I can recall that it did.”

Donna R. Braden, Senior Curator & Curator of Public Life, missed the 1968 World Series but was fortunate enough to attend the last game of the Tigers World Series in 1984.

20th century, 1960s, sports, Michigan, Detroit, by Donna R. Braden, baseball

"Partio" Cart Used by Dwight Eisenhower, circa 1960. THF151438

This upscale Partio outdoor kitchen is an eye-catching icon of America’s postwar prosperity during the Eisenhower era (1953-1961)—and was owned by none other than President Dwight D. Eisenhower himself. America enjoyed unprecedented prosperity as the economy soared to record heights. As people moved to the suburbs, they rediscovered the pleasures of outdoor cooking and eating.

In the 1950s--after the material deprivations of a decade and a half of economic depression, and then war--Americans were ready to buy. The number of homeowners increased by 50 percent between 1945 and 1960. Americans filled their homes with consumer goods that poured out of America’s factories—including televisions, refrigerators, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, electric mixers, and outdoor grills.

Advertising fueled their desire for materials things; credit cards made buying easier. Newsweek magazine commented in 1953 that, “Time has swept away the Puritan conception of immorality in debt and godliness in thrift.” Even President Eisenhower suggested that the American public “Buy anything,” during a slight business dip.

President Eisenhower used this Partio portable kitchen cart at his Palm Springs, California home. The Partio performed surface cooking (burners and griddle), oven cooking (roasting and broiling), and charcoal cooking (grilling and rotisserie). As mentioned in the article, “The Cottage the Eisenhowers Called Home,” published in the February 1962 issue of Palm Springs Life Magazine, the Partio appears pictured with the following caption: “Chef Eisenhower shows Mamie and Mary Jean the patio barbecue cart—‘It’s the most fantastic things you ever saw.’”

GE Partio Cart User's Manual, circa 1960. THF112534

GE Partio Cart User's Manual, circa 1960. THF112534

Designed and built by General Electric, the Partio offers both a seductive glimpse of mid-century southern California outdoor living and hints at trends that become pronounced five decades later. This unit, essentially a cart-mounted range, married with a charcoal grill and rotisserie, combines a vivid 1950s turquoise palette with that decade's angular "sheer" look, forecasting styling trends of the early 1960s. The high-end Partio prefigures the lavish outdoor kitchen barbeque/range units that became popular at the end of the 20th century. At the same time, along with the more familiar Weber charcoal grills, it speaks to an increased leisure and love of outdoor entertaining.

The Henry Ford acquired the Partio in 2012; currently the artifact is out on loan to the Atlanta History Center as part of its current exhibit, "Barbecue Nation," an exploration of the history behind one of America's greatest folk foods.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Marc Greuther is Chief Curator and Senior Director, Historical Resources, at The Henry Ford.

California, 20th century, 1960s, 1950s, presidents, popular culture, making, home life, food, by Marc Greuther, by Jeanine Head Miller

Motown’s Contribution to the Civil Rights Movement

Motown Record Album, “The Great March to Freedom: Rev. Martin Luther King Speaks, June 23, 1963.” THF31935

Detroit’s Walk to Freedom, held on June 23, 1963, helped move the southern Civil Rights struggle to a new focus on the urban North. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. later called this march “one of the most wonderful things that has happened in America.”

Organized by the Detroit Council on Human Rights, this was the largest Civil Rights demonstration to date. Its main purpose was to speak out against Southern segregation and the brutality that faced Civil Rights activists there. It was also meant to raise consciousness about the unique concerns of African Americans in the urban North, which included discriminatory hiring practices, wages, education, and housing. The date was chosen to correlate with both the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 20th anniversary of the 1943 Detroit race riots that had left 34 people (mostly African American) dead. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who agreed to lead the march, had by this time become committed to uniting both North and South through his grand vision of achieving racial justice by using non-violent protest.

On the day of the march, about 125,000 people filed down Woodward Avenue, singing freedom songs and carrying signs demanding racial equality. Some 15,000 spectators watched them pass by a 21-block area before turning west down Jefferson Avenue to Cobo Hall. Cobo was filled to capacity to hear the speeches of the march’s leaders while thousands more listened to them on loudspeakers outside. Of the speeches given that day, Dr. King’s was the most memorable. People were riveted while he expressed his vision for the future, sharing a dream that foreshadowed the “I Have a Dream” speech that he would give a few months later at the March on Washington.

Berry Gordy, founder of the Motown Record Corporation, considered Detroit’s Walk to Freedom to be such a historic event that he offered the resources of his Hitsville studio to produce a record album documenting Dr. King’s impassioned words. Gordy heightened the drama of the event by titling the album, “The Great March to Freedom: Reverend Martin Luther King Speaks.” He believed that this record belonged in every home, that it should be required listening for “every child, white or black.” No one realized at the time, including Gordy, that the August March on Washington would become the more remembered event.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dreams of social justice, voiced at Detroit’s Walk to Freedom, would prove elusive. Despite the fact that Detroit had gained a national reputation for being a “model city” of race relations at the time, in reality the city’s African-American population faced unemployment, housing discrimination, de facto segregation in public schools, and police brutality. Ultimately this disconnect between perception and reality would lead to the violence and civil unrest of July 1967.

For more on the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom held on August 28, 1963, take a look at this post.

Donna R. Braden is the Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

1960s, 20th century, music, Michigan, entrepreneurship, Detroit, Civil Rights, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

The 1963 Mustang II: A Not-So-Missing Link

THF233334 / Advertising Process Photograph Showing the 1963 Ford Mustang II Concept Car.

The 1963 Mustang II (not to be confused with the Ford Pinto-based production Mustang II of the 1970s) surely is one of the most unusual concept cars ever built. Industry practice (and common sense) tells us that an automaker builds a concept car as a kind of far-out “dream car” to generate excitement at car shows. Most never go past the concept stage, but a few do make it into regular production. (Chevrolet’s Corvette and Dodge’s Viper are notable examples.) The Mustang II previewed the production Ford Mustang we all know and love, but the concept car was designed and built after the production Mustang project already was well underway! Why? It’s a case of managing public expectations.

Most Mustang histories start with the 1962 Mustang I, but devoted pony fans know that Mustang I was an entirely separate project from the production car. Ford built the “Mustang Experimental Sports Car” (its original name – the “I” was a retrospective addition) to spark interest in the company’s activities. Ford was going back into racing and looking for a quick way to create some buzz about the exciting things happening in Dearborn. The plan worked a bit too well. When Mustang I debuted at Watkins Glen in October 1962, and then hit the car show circuit, the public went crazy and sent countless letters to Ford begging the company to put the little two-seater into production.

At the same time Mustang I was being built, another team at Ford was working on the production Mustang that would debut in April 1964. Mustang I’s popularity created a problem: Everyone loved the two-seat race car, but would they feel the same about the four-seat version? The solution was to build a new four-seat prototype closely based on the production Mustang’s design.

Enter the 1963 Mustang II.

The new concept car wasn’t just based on the production Mustang’s design – it was actually built from a prototype production Mustang body. Ford designers removed the front and rear bumpers, altered the headlights and grille treatment, and fitted Mustang II with a removable roof. While the car looked different from the production Mustang, a few of the production car’s trademark styling cues were retained, including the C-shaped side sculpting and the tri-bar taillights. Mustang II also consciously borrowed from Mustang I, employing the 1962 car’s distinct white paint and blue racing stripes. Conceptually and physically, the four-seat Mustang II formed a bridge linking the 1962 Mustang I with the 1965 production car. Mustang II was a hit when it debuted at Watkins Glen in October 1963, and when the production version premiered six months later, there were few complaints about the four seats instead of two.

Fortunately, Mustang II is one “link” that isn’t “missing.” The Detroit Historical Society acquired the car in 1975 and has taken great care of it ever since.

View artifacts related to Mustang II in The Henry Ford’s Digital Collections.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, 20th century, 1960s, Mustangs, Ford Motor Company, convertibles, cars, by Matt Anderson

A 1960s Christmas, Then and Now

Nostalgia for those who experienced it—and a hip mid-century modern revival for others.

The Visits with Santa experience in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation this year is a throwback to the 1960s. Kids can tell Santa their wishes as they sit next to him under a colorful kiosk made by Ray and Charles Eames for the IBM pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Nearby is a cozy 1960s living room vignette—complete with a La-Z-Boy chair, television set, and an aluminum Christmas tree from the era.

This mid-century modern theme coincides with the opening of our newest permanent exhibit in the museum, Mathematica, also designed by Ray and Charles. Several components of Mathematica were featured inside that IBM Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair, so we were excited to bring those two experiences together for this year’s holiday programming.

The scene provides a bit of nostalgia for those who experienced the 1960s—and a hip mid-century modern revival for others. Let’s look at some blasts from the 1960s Christmas past.

Aluminum trees brought a modern look to a mid-1960s Christmas. THF170112

The early 1960s brought a fresh, new look to Christmas tree aesthetics. A completely modern look--the aluminum Christmas tree. It made a shiny, metallic splash in living rooms all over America. More than a million trees were sold during the decade. A tree choice that eschewed the traditional pine- or fir-scented Christmas experience when it landed on the Christmas scene in the 1960s, now conjures up images of a retro Christmas past.

Color wheel sold by Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1960-1965. THF8379

A color wheel lit up the aluminum tree, with the tree changing from blue to red to green to gold as the wheel revolved. The color wheel was there for a practical reason—you couldn’t put strings of lights on aluminum trees because of fire safety concerns. But to those viewing the transformation, the color wheel seemed a no-brainer way to light these trees—so modern and so magical. It was mesmerizing to watch—whether from a front row seat in your living room or the view through your neighbor’s window.

The Smith family of Redford, Michigan purchased these ornaments in 1964 to hang on their aluminum Christmas tree. THF309083

Aluminum trees called for minimalist look. The trees were often sparingly decked with ornaments all of one color.

The Wojewidka siblings pose for a Christmas photo in front of their live tree in 1960. THF125145

Yet, “real” trees remained popular as well—fresh-cut trees chosen from one of the many temporary Christmas tree lots that popped up in cities and towns. (The cut-your-own trend was not yet widespread.) Scotch pines were favored by many—though there were diehard balsam fans as well. These trees were bedecked with a varied array of ornaments—glass ones by the Shiny Brite company were popular. And shiny “icicles”—made of lead before it was prohibited—hung from the branches to add to the sparkle.

Holiday Greetings in the Mail

By the early 1960s, Christmas cards offered a greater variety of seasonal images beyond those traditionally found. This image shows a woman clothed in a pine tree decorated with 1960s trendy-colored ornaments. THF287028

By mid-December, mailboxes were filling with Christmas cards, sent by family and friends to let the recipient know that they were being specially thought of during the holiday season. It was exciting to pull out handfuls of cards from the mailbox—it may have been the only time during the year when a kid had much interest in what the postman delivered. And not necessarily because of the cards themselves—the cards were a tangible sign that Christmas was indeed on its way and that Santa would soon be making his deliveries!

Christmas card display clothesline and pins, about 1964. THF155082

Where did people display all these Christmas cards? On a mantle, a table, or the top of the television. Or taped to a wall or a large mirror in the living room. Hanging them from a Christmas-themed clothesline was a more novel way to display them.

This 1962 stamp carried traditional Christmas images of lighted candles and a wreath. THF287036

In 1962, the United States Postal Service issued the first Christmas-themed postage stamps in America. (A few other countries had already beaten us to the punch on issuing Christmas-themed postage stamps.) But once begun, Christmas stamps graced more and more Christmas card envelopes to complete the annual presentation of holiday-themed greetings sent through the mail.

Making a List

Christmas catalogs like this 1964 Sears, Roebuck & Company got a workout in December. THF135874

Kids were busy deciding what to ask Santa for. Instead of perusing the web, kids looked forward to the arrival of Christmas season catalogs sent by stores like Sears, Roebuck and Company, J.C. Penney, and Montgomery Ward. Kids (and adults) eagerly leafed through the pages of the toys, clothing, and other gifts offered within, making their wish list for Santa’s perusal before passing the catalog along to another family member.

Television offered additional gift ideas, playing out the merits of products before viewers’ eyes in commercials that one couldn’t speed past with a DVR.

Toys for Girls and Boys

Many 1960s toys that appeared on the Christmas lists of millions of kids during the 1960s—some in updated versions—are still classics.

Silly Putty modeling compound, about 1962. THF135811

Silly Putty was invented during World War II as General Electric researchers worked to develop a synthetic substitute for rubber. While no practical purpose could be found for the stuff, it did turn out to be a great toy. Silly Putty bounced higher and stretched farther than rubber. It even lifted images off the pages of color comics. (My sister took Silly Putty to bed with her, leaving a perfect egg-shaped stain on the sheets that never came out.)

Eight-year-old Rachel Marone of New York received this Etch A Sketch as s Christmas gift in 1961. THF93827

The 1960s saw an innovative new arts and crafts toy—the Etch A Sketch. Turning the knobs at the bottom of the screen (one to create horizontal lines, one for vertical) let the user “draw” on the screen with a mixture of aluminum powder and plastic beads. To erase, you just turned the screen over and shook it. Incidentally, it was the first toy that Ohio Art, its manufacturer, ever advertised on television. (Accomplished users could make great drawings on the Etch A Sketch—and some of us were just happy to produce decent-looking curved lines.)

This 1962 Play-Doh Fun Factory was a childhood toy of Mary Sherman of Minnesota. THF170363

Play-Doh introduced their Fun Factory in 1960. Now kids could go beyond free-form modeling with their red, yellow, blue and white Play-Doh. The Play-Doh Fun Factory provided instructions on how to create things like trains, planes, and boats—and an extruder with dies to easily make the components.

Watching Christmas Specials on TV

Album from A Charlie Brown Christmas television special, about 1965. THF162745

Kids eagerly listened for announcements on television or leafed excitedly through TV Guide magazine to find out when the holiday specials would air. You didn’t want to miss them—it was your only shot at watching! There were no DVRs or DVDs back then. Two animated classics from the mid-1960s--A Charlie Brown Christmas and How the Grinch Stole Christmas--are among the earliest and most enduring of the Christmas specials developed for television.

Within their engaging storylines, these two shows carried a message about the growing commercialization of the holiday. As kids watched the barrage of toy ads that appeared with regularity on their television screens and leafed through catalogs to make their Christmas lists, seeing these cartoons reminded them that Christmas was also about higher ideals—not just about getting presents. These television shows—and the increasing number and variety of Christmas specials that have since joined them—remain a yearly reminder to temper one’s holiday-related commercialism and to think of the needs of others.

Not only have Charlie Brown and the Grinch become perennial favorites enjoyed by children and adults alike, but the soundtracks of these shows have joined the pantheon of musical Christmas classics.

Christmas Music

The Ronettes’ version of Sleigh Ride, with its freshly melodic “Ring-a-ling-a-ling Ding-dong ding” background vocals on this 1963 Phil Spector-produced album, has become an iconic Christmas classic. THF135943

What would a 1960s Christmastime be without Christmas-themed music heard on the stereo at home and over speakers in stores? The 1960s saw a flood of Christmas albums and singles. Various singers—like Andy Williams, Nat King Cole, Perry Como, Johnny Mathis, Brenda Lee, Ella Fitzgerald, Elvis Presley, the Ronettes, the Crystals, and the Beach Boys—recorded their versions of old favorites and new tunes.

The Annual Christmas Photo

In 1963, the Truby brothers of Royal Oak, Michigan, posed in Santa pajamas given to them by their grandmother. THF287005

After the presents were opened and everyone was dressed in their Christmas finery, it was time to round up the kids for photos. Siblings (and, sometimes, their parents) might be posed together in front of a seasonal backdrop like the Christmas tree or a fireplace. Some families filmed home movies of their celebrations. These home movies often captured only strategic snippets of the Christmas celebration—movie film was expensive. And these home movies were without sound—which was probably sometimes a good thing!

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

1960s, 20th century, home life, toys and games, popular culture, holidays, Henry Ford Museum, events, correspondence, Christmas, by Jeanine Head Miller