Posts Tagged engines

Leo Goossen

Supercharger Assembly Drawing of Offenhauser Engine by Leo Goossen, April 21, 1934 / THF175170

Leo Goossen was an automotive draftsman, engineer, and one of the most influential engine designers in American auto racing. In a presentation from our monthly History Outside the Box series on Instagram earlier this year, Processing Archivist Janice Unger recognized Goossen’s 130th birthday with a quick biography and look at some of Goossen’s work from our collections. If you missed it on Insta, you can watch below.

California, 20th century, racing, race cars, Michigan, History Outside the Box, engines, engineering, drawings, cars, by Janice Unger, by Ellice Engdahl, archives

Barney Korn: Tether Car Craftsman

Barney Korn’s work is featured in The Henry Ford’s exhibit Driven to Win: Racing in America. / Photo by Matt Anderson

In the 1930s and 1940s, race fans who didn’t have the budget or the bravery for full-size auto racing could find big thrills in small scale through the world of tether cars. These gas-powered model cars were raced by adults in organized competition. The models either raced against the clock, running in circles while tethered to a pole, or they raced against each other on a scaled-down board track fitted with guide rails.

The fastest tether cars topped 100 miles per hour—real miles, not scale miles—which explains another name given to them: spindizzies. (Imagine watching a little car zooming around a pole and the name makes perfect sense.) Though they look like toys, these models could be expensive. By the time you bought the car, the engine, the tools, and the accessories, you could be looking at more than $100—at a time when you could by a Ford DeLuxe Convertible for well under $1,000. At the hobby’s peak, some 25 major manufacturers and hundreds of individual builders produced tether cars. But few makers matched the skill and craftsmanship of Barney Korn.

Barney Korn’s skill was apparent from his high school days, as when he built this working engine in shop class. / THF160779

Bernard Barney Korn was born in Los Angles on April 24, 1903. He showed his modeling talents at an early age, building an elaborate water-cooled model engine as a project for his high school shop class. After high school, Korn honed his skills in part by working as a machinist for aviation innovator Howard Hughes, whom he joined in 1924.

One of Barney Korn’s “Indianapolis” models, with the hood removed to expose the single-cylinder gas engine. / THF157084

As tether cars became more popular, Barney Korn joined the booming business and formed B.B. Korn Specialty Manufacturing Company in 1939. His first production model, the “Meteor,” was also his rarest. Only 18 examples are known to have been made. The following year, Korn began production of his best-known and, many would say, best-looking model: the “Indianapolis.” Based on real Indianapolis 500 race cars of the time, Korn’s “Indianapolis” was handsome and well proportioned. It was a big model, with an overall length over 20 inches. Many were also exceptionally detailed. The “Liberty Special” car even had a working compass in its dashboard! But the “Indianapolis” was rare too. It’s believed that Korn produced fewer than 70 examples in total. Most featured rear-wheel drive trains and aluminum bodies, though a few had lightweight magnesium bodies. When materials were restricted during World War II, Korn mixed and matched aluminum and magnesium components as needed.

Korn’s working dynamometer measured engine performance in his model cars. / THF159749

Barney Korn used precision tools, molds, and patterns to build his model cars. In a particularly impressive feat, Korn even built a working dynamometer to test his cars’ performance. Like full-size dynamometers, Korn’s version was basically a treadmill for engines. It allowed a model car’s drive wheels to spin while the car itself remained stationary. Korn’s dyno measured the power and torque of the .60-cubic inch engine as it delivered power to the wheels. The little dynamometer was even adjustable to accommodate both front and rear-wheel drive models.

This unfinished Korn “Indianapolis 29” kit would have appealed to the budget-conscious tether car buyer. / THF162913

The B.B. Korn Manufacturing Company provided a few options for budget-conscious buyers. Instead of a standard “Indianapolis” model, they could purchase one of Korn’s “Indianapolis 29” cars. Everything about the “29” series was smaller—from the .29-cubic inch engines (source of the name), to the dimensions, to the all-important price tags. Those wanting to save even more could opt for an unassembled “Indianapolis 29” kit rather than a fully assembled car. With the kit, it was up to the buyer to finish rough edges on the balsa wood body, and to source an engine separately.

Barney Korn’s tether cars were beautifully made and carefully detailed, but that quality came at a price—in dollars and in performance. Korn’s models were too expensive for amateur hobbyists and too slow for serious racers. Poor sales made the B.B. Korn Manufacturing Company unsustainable, and it closed just a few years after it opened.

Barney Korn went on to a career in modelmaking for special effects work in films. His detailed miniatures can be seen in movies like To Please a Lady, a 1950 racing melodrama staring Clark Gable and Barbara Stanwyck, and Moby Dick, the 1956 adaptation of Herman Melville’s novel directed by John Huston. In the early 1980s, Korn even built a few improved versions of his original tether car designs.

Barney Korn died in Los Angeles on October 23, 1996, but his craftsmanship survives. Replicas of Korn’s models are readily available today, and originals are highly prized by collectors. It’s a proud legacy for a talented artist who some regard as the Leonardo da Vinci of the tether car hobby.

Explore Further

“Barney Korn: Tether Car Craftsman” expert set

“Tether Cars: Big Thrills in Small Scale” expert set

Driven to Win: Racing in America exhibit information

Artifacts related to tether cars in our Digital Collections

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- 2016 Le Mans Class-winning Ford GT Race Car, On Loan from Ford Motor Company

- 1901 Ford "Sweepstakes" Race Car

- 1902 Ford "999" Race Car, Built by Henry Ford

- 1906 Locomobile "Old 16" Race Car

engineering, engines, making, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, toys and games, by Matt Anderson, cars, racing

Horse Power

Detail, 1882 advertisement showing a three-horse tread power in use. / THF277170

How much horsepower really comes from a horse? While the answer to this may seem obvious, it is complicated. The most complete answers start out with "it depends."

Much of farming is strenuous, tedious, repetitive work. For American farmers, chronic labor shortages made the effort of farm work even more taxing, so they looked for ways to get farm work done with less manpower. Horses and oxen were the main source of power, used for centuries for plowing. Improved farm machinery throughout the 1800s added the power of horses to other activities such as planting, cultivating, and, eventually, mowing and harvesting. Farmers understood the effort required for these tasks in terms of the number of horses needed to pull the equipment, such as one horse for a cultivator, and three or more for a harvester or large plow. Applying the power of horses to farm work helped to steadily increase the productivity of American farms throughout the 1800s.

This 1854 engraving depicted the centuries-old practice of plowing with horses. Throughout the 1800s, farmers increasingly used horses or oxen for other work as well, including planting, cultivating, mowing, and harvesting. / THF118302

Yet horsepower as a measure of power pre-dates the mechanization of the farm. It was developed by James Watt in the 1780s as a way to measure the output of a steam engine. Horsepower was based on his observations of how much work a horse could do in a normal ten-hour day, pulling the sweep arms of the horse-powered pumps that were used to remove water from mines. This worked out to 33,000 foot-pounds per minute, or the effort required to raise 33,000 pounds of water by one foot in one minute.

An 1886 trade catalog depicted Russell & Co.’s “New Massillon” grain thresher powered by both a steam traction engine and a horse-driven sweep power. / THF627487, THF627489

As farmers mechanized barn or farmyard work like threshing, winnowing, corn shelling, and corn grinding, they began to use stationary power sources—either treadmills and sweeps powered by horses, or steam engines. Here, the agricultural idea of horsepower and the industrial idea of horsepower bumped heads. For example, the portable steam engine pictured just below is rated at ten horsepower. It could be used to run the same piece of farm equipment as the two-horse tread power depicted below the steam engine, which used, well, two horses. Some farmers came to use a rule of thumb for farm equipment, calculating that one horse was worth about three horsepower in an engine. Why is this?

This ten-horsepower steam engine (top) could power the same piece of farm equipment as a two-horse tread power (bottom). / THF92184, THF32303

Engine horsepower ratings (and there are many varieties of these) are typically overestimated because they are often calculations of the power delivered to the machine—not how much actually reaches its "business end." For example, they do not account for power losses that occur between the piston and whatever the piston is driving—which can be more like 70% to 90% of the rated horsepower. In addition, those measures are made at the ideal engine speed.

On the other hand, numerous studies have shown that peak horsepower for a horse (sustainable for a few seconds) is as high as 12-15 horsepower. This is based on calculated estimates, as well as observed estimates (recorded in a 1925 study of the Iowa State Fair's horse pull). Over the course of a ten-hour workday, however, the average output of a horse is closer to one horsepower—which coincides with James Watt's original way of describing horsepower.

So how much horsepower comes from a horse? As we see, it depends. If we measure it in an optimal way, as we do with engines, it is as high as 15 horsepower. If we measure it as James Watt did—over the course of a long 10-hour day, horses walking in a circle—it gets down to about one horsepower. Nineteenth-century farmers quickly learned that if they were buying an engine for a task horses had previously performed, they needed an engine rated for three horsepower for every horse they had used for the task.

This post by Jim McCabe, former Collections Manager and Curator at The Henry Ford, originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series in May 2007. It was updated for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content.

Additional Readings:

- Microscope Used by George Washington Carver, circa 1900

- Bringing in the Beans: Harvesting a New Commodity

- As Ye Sow So Shall Ye Reap: The Bickford & Huffman Grain Drill

- Oliver Chilled Cast Iron Plow, circa 189

engines, by Saige Jedele, by Jim McCabe, power, agriculture, farms and farming, farming equipment, farm animals

Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

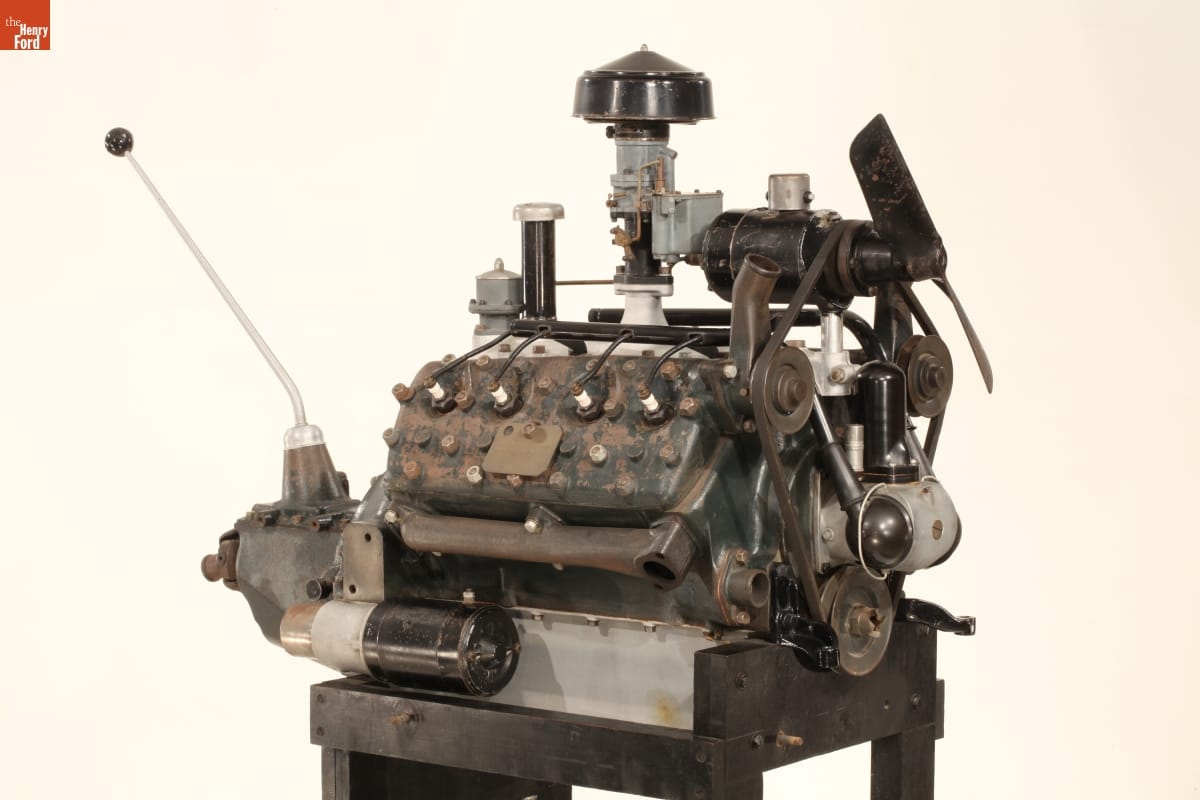

1932 Ford V-8 Engine, No. 1. / THF101039

It’s been said that when the Ford flathead V-8 went into production in 1932, Ford Motor Company revolutionized the automobile industry—again. And the engine put the hot rod movement into high gear.

What made this engine revolutionary? It was the first V-8 light enough and cheap enough to go into a mass-produced vehicle. The block was cast in one piece, and the design was conducive to backyard mechanics’ and gearheads’ modifications.

This 1932 brochure illustrates the difference between the Ford V-8, with the cylinders and crankcase cast as a single block of iron, and a traditional V-8, built by bolting separate cylinders onto the crankcase. / THF125666

With so much at stake, you would think Henry Ford would set up his engineers tasked with the engine’s design in the most state-of-the-art facility he had at his disposal.

Not so. Instead, Ford sent a handpicked crew to Greenfield Village to gather in Thomas Edison’s Fort Myers Laboratory, which had been moved from Fort Myers, Florida, to Dearborn not long before.

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison with Fort Myers Laboratory at its original site, Fort Myers, Florida, circa 1925. / adapted from THF115782

“Henry Ford likely used the building because it provided his engineers with privacy and freedom from distraction,” said Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. “I imagine he also thought the team might be inspired by the surroundings.”

Ford’s plan worked. In just two years, Ford’s engineering crew left the lab in Greenfield Village with a final design.

Continue Reading

Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Henry Ford, Ford Motor Company, manufacturing, design, engineering, engines, race cars, cars, racing, The Henry Ford Magazine

Remembering Mose Nowland (1934-2021)

Mose Nowland, with wife Marcia and daughter Suzanne, at The Henry Ford in June 2021.

The Henry Ford lost a dear friend and a treasured colleague on August 13, 2021, with the passing of Mose Nowland. When he joined our Conservation Department as a volunteer in 2012, Mose had just concluded a magnificent 57-year career with Ford Motor Company—most of it in the company’s racing program—and he was eager for something to keep himself occupied in retirement. We soon discovered that “retire” was just about the only thing that Mose didn’t know how to do.

To fans of Ford Performance, Mose was a legendary figure. He joined the Blue Oval in 1955 and, after a brief pause for military service, he spent most of the next six decades building racing engines. Mose led work on the double overhead cam V-8 that powered Jim Clark to his Indianapolis 500 win with the 1965 Lotus-Ford. Mose was on the team behind the big 427 V-8 that gave Ford its historic wins over Ferrari at Le Mans—first with the GT40 Mark II in 1966 and then again with the Mark IV in 1967. And Mose was there in the 1980s when Ford returned to NASCAR and earned checkered flags and championships with top drivers like Davey Allison and Bill Elliott.

Mose with one of his creations during Ford’s Total Performance heyday.

Following his retirement, Mose transitioned gracefully into the role of elder statesman, becoming one of the last remaining participants from Ford’s glory years in the “Total Performance” 1960s. Museums and private collectors sought him out with questions on engines and cars from that era, and he was always happy to share advice and insight. Mose’s expertise was exceeded only by his modesty. He never claimed any personal credit for Ford’s racing triumphs—he was just proud to have been part of a team that made motorsport history. Mose was able to see that history reach a wider audience with the success of the recent movie Ford v Ferrari.

Michigan, Dearborn, The Henry Ford staff, 21st century, 20th century, racing, race cars, philanthropy, Old Car Festival, Model Ts, Mark IV, making, in memoriam, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, engines, engineering, collections care, cars, by Matt Anderson, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Henry Ford: Case Study of an Innovator

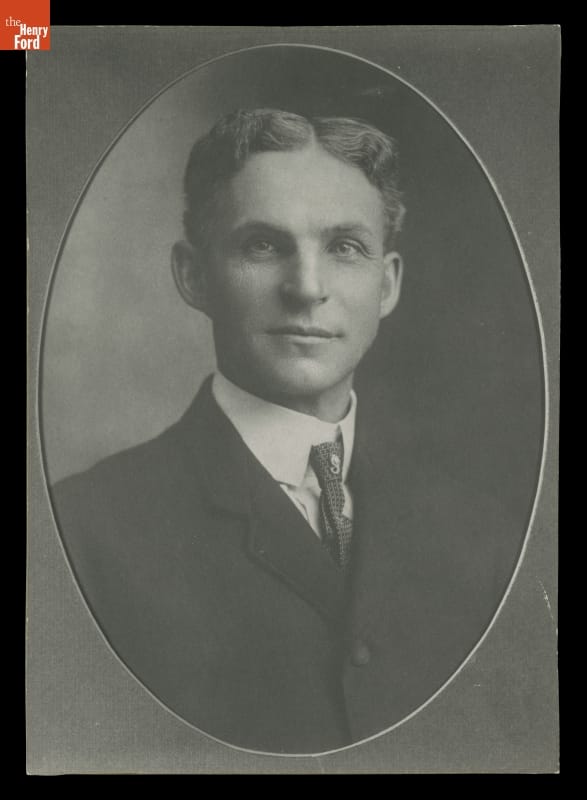

Henry Ford’s first official Ford Motor Company portrait, 1904. / THF97952

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile. But more than any other single individual, he was responsible for transforming the automobile from an invention of unknown utility into an innovation that profoundly shaped the 20th century and continues to affect the 21st. His work at Ford Motor Company revolutionized the automotive industry, setting new standards for production and accessibility.

Innovators change things. They take new ideas—sometimes their own, sometimes other people’s—and develop and promote those ideas until they become an accepted part of daily life. Innovation requires self-confidence, a taste for taking risks, leadership ability, and a vision of what the future should be. Henry Ford had all these characteristics, but it took him many years to develop all of them fully.

Portrait of the Innovator as a Young Man

Ford’s beginnings were perfectly ordinary. He was born on his father’s farm in what is now Dearborn, Michigan, on July 30, 1863. At this time, most Americans were born on farms, and most looked forward to being farmers themselves. Early on, Ford demonstrated some of the characteristics that would make him successful. In his family, he became infamous for taking apart his siblings’ toys as well as his own. He organized other boys to build rudimentary waterwheels and steam engines. He learned about full-size steam engines by becoming acquainted with the engines’ operators and pestering them with questions. He taught himself to fix watches and used the watches themselves as textbooks to learn the basics of machine design. Thus, at an early age, Ford demonstrated curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, the capacity for leadership, and a preference for learning by trial and error. These characteristics would become the foundation of his whole career.

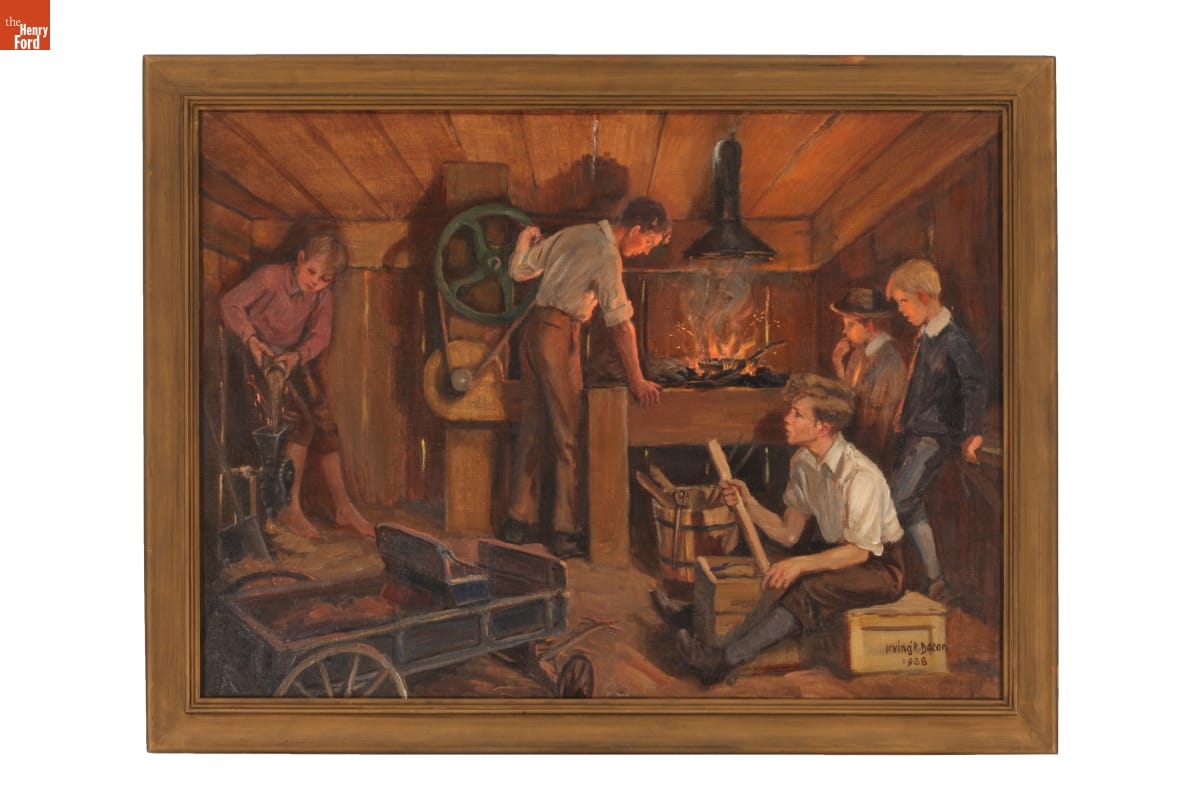

Artist Irving Bacon depicted Henry Ford in his first workshop, along with friends, in this 1938 painting. / THF152920

Ford could simply have followed in his father’s footsteps and become a farmer. But young Henry was fascinated by machines and was willing to take risks to pursue that fascination. In 1879, he left the farm to become an apprentice at a machine shop in Detroit. Over the next few years, he held jobs at several places, sometimes moving when he thought he could learn more somewhere else. He returned home in 1882 but did little farming. Instead, he operated and serviced portable steam engines used by farmers, occasionally worked in factories in Detroit, and cut and sold timber from 40 acres of his father’s land.

By now, Ford was demonstrating another characteristic—a preference for working on his own rather than for somebody else. In 1888, Ford married Clara Bryant, and in 1891 they moved to Detroit. Ford had taken a job as night engineer for the Edison Electric Illuminating Company—another risk on his part, because he did not know a great deal about electricity at this point. He took the job in part as an opportunity to learn.

Henry Ford (third from left, in white coat) with other employees at Edison Illuminating Company Plant, November 1895. / THF244633

Early Automotive Experiments: Failure and Then Success

Henry was a skilled student, and by 1896 had risen to chief engineer of the Illuminating Company. But he had other interests. He became one of the scores of other people working in barns and small shops trying to make horseless carriages. Ford read about these other efforts in magazines, copying some of the ideas and adding some of his own, and convinced a small group of friends and colleagues to help him. This resulted in his first primitive automobile, the Quadricycle, completed in 1896. A second, more sophisticated car followed in 1898. These early experiments laid the groundwork for his future endeavors in the automotive industry.

Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle Runabout, the first car he built. / THF90760

Ford now demonstrated one of his most important characteristics—the ability to articulate a vision and convince other people to sign on and help him achieve that vision. He convinced a group of businessmen to back him in the biggest risk of his life—starting a company to make horseless carriages. But Ford knew nothing about running a business, and learning by doing often involves failure. The new company failed, as did a second. His first venture, the Detroit Automobile Company, failed due to the poor quality of its vehicles. Ford tried again, this time with the Henry Ford Company. But disputes over the new company’s direction soon caused Ford and his investors to part ways.

To revive his fortunes, Ford took bigger risks, building and even driving a pair of racing cars. The success of these cars attracted additional financial backers, and on June 16, 1903, just before his 40th birthday, Henry incorporated his third automobile venture, the Ford Motor Company.

The early history of Ford Motor Company illustrates another of Henry Ford’s most valuable traits—his ability to identify and attract outstanding talent. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years and make Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years, reshaping America’s automotive industry while building Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises.

Print of Norman Rockwell's painting, "Henry Ford in First Model A on Detroit Street." / THF288551

The new company’s first car was called the Model A, and a variety of improved models followed. In 1906, Ford’s 4-cylinder, $600 Model N became the best-selling car in the country. But by this time, Ford had a vision of an even better, cheaper “motorcar for the great multitude.” Working with a small group of employees, he came up with the Model T, introduced on October 1, 1908. The Model T was a game-changer, designed to be simple, reliable, and ultimately affordable for the average American.

The Automobile: A Solution in Search of a Problem

As hard as it is for us to believe, in 1908 there was still much debate about exactly what automobiles were good for. We may see them as a necessary part of daily life, but the situation in 1908 was very different. Americans had arranged their world to accommodate the limits of the transportation devices available to them. People in cities got where they wanted to go by using electric street cars, horse-drawn cabs, bicycles, and shoe leather because all the places they wanted to go were located within reach of those transportation modes.

This Boston street scene, circa 1908, shows pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages on the road—but no cars. / THF203438

Most of the commercial traffic in cities still moved in horse-drawn vehicles. Rural Americans simply accepted the limited travel radius of horse- or mule-drawn vehicles. For long distances, Americans used our extensive, well-developed railroad network. People did not need automobiles to conduct their daily activities. Rather, the people who bought cars used them as a new means of recreation. They drove them on joyrides into the countryside. The recreational aspect of these early cars was so important that people of the time divided motor vehicles into two large categories: commercial vehicles, like trucks and taxicabs, and pleasure vehicles, like private automobiles. The term “passenger cars” was still years away. The automobile was an amazing invention, but it was essentially an expensive toy, a plaything for the rich. It was not yet a true innovation.

Henry Ford had a wider vision for the automobile. He summed it up in a statement that appeared in 1913 in the company magazine, Ford Times:

“I will build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one—and enjoy with his family the blessings of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.”

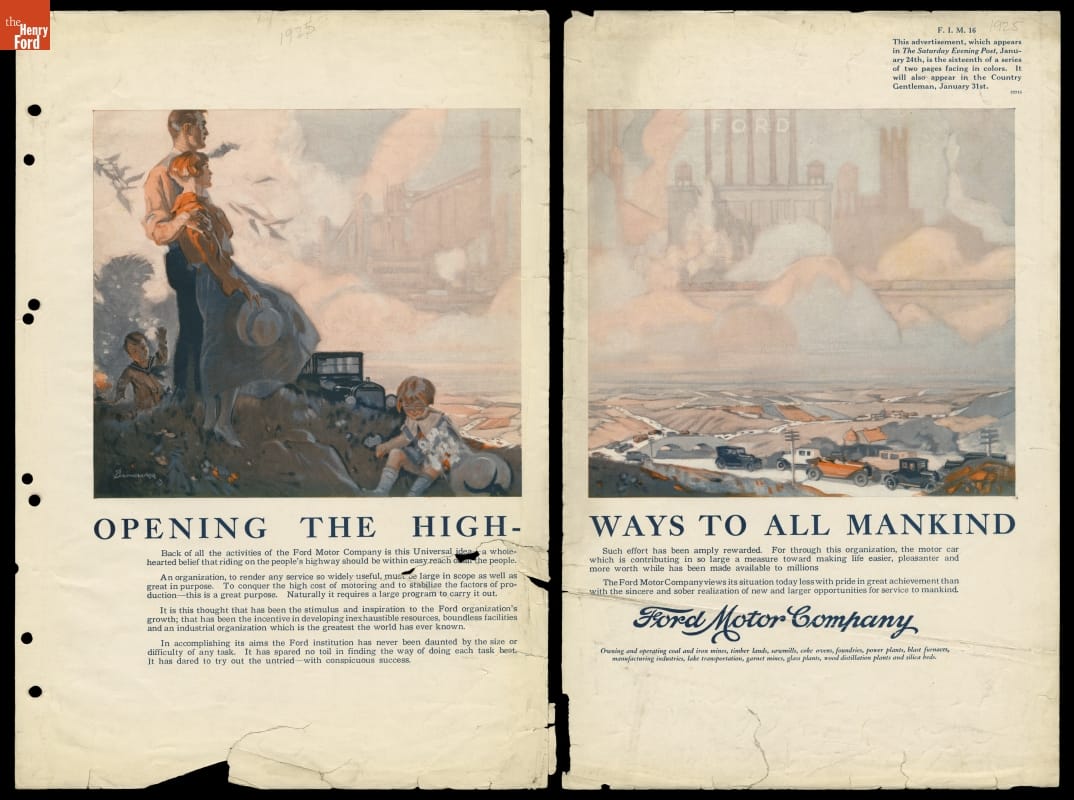

This 1924 Ford ad, part of a series, echoes the vision expressed 11 years earlier by Henry Ford: “Back of all of the activities of the Ford Motor Company is this Universal idea—a wholehearted belief that riding on the people’s highway should be in easy reach of all the people.” / THF95501

It was this vision that moved Henry Ford from inventor and businessman to innovator. To achieve his vision, Ford drew on all the qualities he had been developing since childhood: curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, leadership, a preference for learning by trial and error, a willingness to take risks, and an ability to identify and attract talented people.

One Innovation Leads to Another

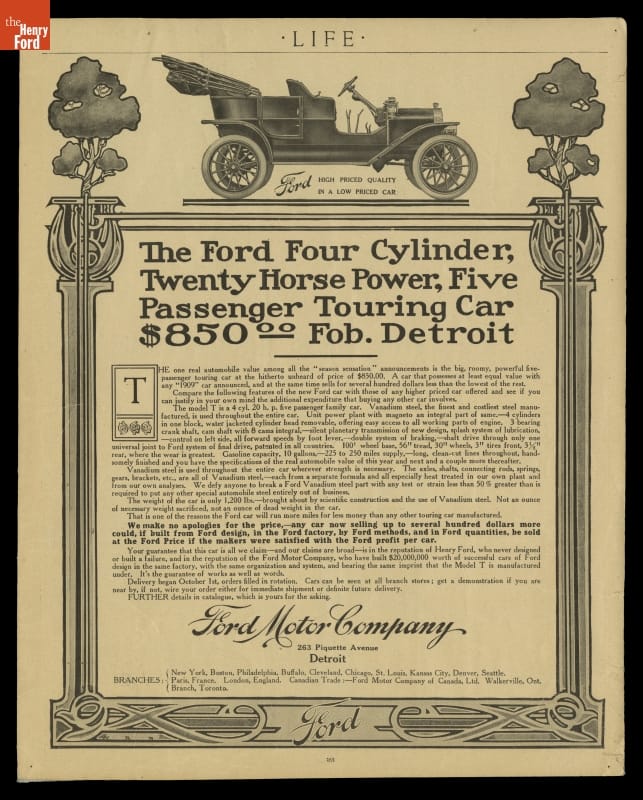

Ford himself guided a design team that created a car that pushed technical boundaries. The Model T’s one-piece engine block and removable cylinder head were unusual in 1908 but would eventually become standard on all cars. The Ford’s flexible suspension system was specifically designed to handle the dreadful roads that were then typical in the United States. The designers utilized vanadium alloy steel that was stronger for its weight than standard carbon steel. The Model T was lighter than its competitors, allowing its 20-horsepower engine to give it performance equal to that of more expensive cars. The Model T forever changed the automotive industry and American culture. Its impact can still be felt today.

1908 advertisement for the 1909 Ford Model T. In advertisements, Ford Motor Company emphasized key technological features and the low prices of their Model Ts. Ford's usage of vanadium steel enabled the company to make a lighter, sturdier, and more reliable vehicle than other early competitors. / THF122987

The new Ford car proved to be so popular that Henry could easily sell all he could make, but he wanted to be able to make all he could sell. So Ford and his engineers began a relentless drive both to raise the rate at which Model Ts could be produced and to lower the cost of production.

In 1910, the company moved into a huge new factory in Highland Park, a city just north of Detroit. Borrowing ideas from watchmakers, clockmakers, gunmakers, sewing machine makers, and meat processors, Ford Motor Company had, by 1913, developed a moving assembly line for automobiles. But Ford did not limit himself to technical improvements.

When his workforce objected to the relentless, repetitive work that the line entailed, Ford responded with perhaps his boldest idea ever—he doubled wages to $5 per day. With that one move, he stabilized his workforce and gave it the ability to buy the very cars it made. He hired a brilliant accountant named Norval Hawkins as his sales manager. Hawkins created a sales organization and advertising campaign that fueled potential customers’ appetites for Fords. Model T sales rose steadily while the selling price dropped. By 1921, half the cars in America were Model Ts, and a new one could be had for as little as $415.

Norval Hawkins headed the sales department at Ford Motor Company for 12 years, introducing innovative advertising techniques and increasing Ford’s annual sales from 14,877 vehicles in 1907 to 946,155 in 1919. / THF145969

Through these efforts, Ford turned the automobile from an invention bought by the rich into a true innovation available to a wide audience. By the 1920s, largely as a result of the Model T’s success, the term “pleasure car” was fading away, replaced by “passenger car.” Ford’s moving assembly line and $5 day ushered in a new era of mass production and affordability. American society itself was transformed as motorists were free to travel where they wanted, when they wanted.

The assembly line techniques pioneered at Highland Park spread throughout the auto industry and into other manufacturing industries as well. The high-wage, low-skill jobs pioneered at Highland Park also spread throughout the manufacturing sector. Advertising themes pioneered by Ford Motor Company are still being used today. Ford’s curiosity, leadership, mechanical ability, willingness to take risks, ability to attract talented people, and vision produced innovations in transportation, manufacturing, labor relations, and advertising. His legacy is preserved at places like Greenfield Village, showcasing his impact on American life and the evolution of the automotive industry.

What We Have Here Is a Failure to Innovate

Henry Ford was slow to admit that customers no longer wanted the Model T. However, in 1927, he finally acknowledged that shift, and Henry Ford and his son, Edsel Ford, drove this last Model T—number 15,000,000—off the assembly line at Highland Park. / THF135450

Henry Ford’s great success did not necessarily bring with it great wisdom. In fact, his very success may have blinded him as he looked to the future. The Model T was so successful that he saw no need to significantly change or improve it. He did authorize many detail changes that resulted in lower cost or improved reliability, but there was never any fundamental change to the design he had laid down in 1907.

He was slow to adopt innovations that came from other carmakers, like electric starters, hydraulic brakes, windshield wipers, and more luxurious interiors. He seemed not to realize that the consumer appetites he had encouraged and fulfilled would continue to grow. He seemed not to want to acknowledge that once he started his company down the road of innovation, it would have to keep innovating or else fall behind companies that did innovate. He ignored the growing popularity of slightly more expensive but more stylish and comfortable cars, like the Chevrolet, and would not listen to Ford executives who believed it was time for a new model.

But Model T sales were beginning to slip by 1923, and by the late 1920s, even Henry Ford could no longer ignore the declining sales figures. In 1927, he reluctantly shut down the Model T assembly lines and began the design of an all-new car. It appeared in December 1927 and was such a departure from the old Ford that the company went back to the beginning of the alphabet for a name—it was called the Model A.

Edsel and Henry Ford introduce the new Model A at the Ford Industrial Exposition in New York in January 1928. Edsel had worked to convince his father to replace the outmoded Model T with something new. / THF91597

One area where Ford did keep innovating was in actual car production. In 1917, he began construction of a vast new plant on the banks of the Rouge River southwest of Detroit. This plant would give Ford Motor Company complete control over nearly all aspects of the production process. Raw materials from Ford mines would arrive on Ford boats, and would be converted into iron and steel, which were transformed into engines, transmissions, frames, and bodies. Glass and tires would be made onsite as well, and all of this would be assembled into completed cars. Assembly of the new Model A was transferred to the Rouge. Eventually the plant would employ 100,000 people and generate many innovations in auto manufacturing. The River Rouge complex became a symbol of Ford's ambition and scale, a testament to his vision for vertically integrated production.

But improvements in manufacturing were not enough to make up for the fact that Henry Ford was no longer a leader in automotive design. The Model A was competitive for only four years before needing to be replaced by a newer model. In 1932, at age 69, Ford introduced his last great automotive innovation, the lightweight, inexpensive V-8 engine. It represented a real technological and marketing breakthrough, but in other areas Fords continued to lag behind their competitors. The Ford factory continued to evolve, but the company faced new challenges in keeping up with changing consumer preferences and technological advancements in the automotive industry.

The V-8 engine was Henry Ford’s last great automotive innovation. This is the first V-8 engine produced, which is on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF101039

By 1936, the company that once sold half of the cars made in America had fallen to third place behind both General Motors and the upstart Chrysler Corporation. By the time Henry Ford died in 1947, his great company was in serious trouble, and a new generation of innovators, led by his grandson Henry Ford II, would work long and hard to restore it to its former glory. Henry’s story is a textbook example of the power of innovation—and the power of its absence. His contributions to the automotive industry and American society are undeniable, but his later resistance to change serves as a cautionary tale.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Henry Ford and Innovation: From the Curators.”

Detroit, Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, 19th century, quadricycle, Model Ts, manufacturing, Henry Ford, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, entrepreneurship, engines, engineering, cars, by Bob Casey, advertising

"An Honest Effort": Claude Harvard and Ford Motor Company

“Speaking from my own experience, brief as it is, I feel certain that the man or woman who has put his very best into honest effort to gain an education will not find the doors to success barred.”

One of the few, if not the only, Black engineers employed by Henry Ford at the time, Claude had been personally sent to Tuskegee by Ford to showcase an invention of his own creation. Even in the face of societal discrimination, the message of empowerment and perseverance that Claude imparted on that day was one that he carried with him over the course of his own career. For him, there was always a path forward.

Claude Harvard practicing radio communication with other students at Henry Ford Trade School in 1930. / THF272856

Born in 1911, Claude spent the first ten years of his life in Dublin, Georgia, until his family, like other Black families of the time period, made the decision to move north to Detroit in order to escape the poor economic opportunities and harsh Jim Crow laws of the South. From a young age, Claude was intrigued by science and developed a keen interest in a radical new technology—wireless radio. To further this interest, he sold products door-to-door just so he could acquire his own crystal radio set to play around with. It would be Claude’s passion for radio that led him to grander opportunities.

At school in Detroit, Harvard demonstrated an aptitude for the STEM fields and was eventually referred to the Henry Ford Trade School, a place usually reserved for orphaned teen-aged boys to be trained in a variety of skilled, industrial trade work. His enrollment at Henry Ford Trade School depended on his ability to resist the racial taunting of classmates and stay out of fights. Once there, his hands-on classes consisted of machining, metallurgy, drafting, and engine design, among others. In addition to the manual training received, academic classes were also required, and students could participate in clubs.

Claude Harvard with other Radio Club members and their teacher at Henry Ford Trade School in 1930. / THF272854

As president of the Radio Club, Claude Harvard became acquainted with Henry Ford, who shared an interest in radio—as early as 1919, radio was playing a pivotal role in Ford Motor Company’s communications. Although he graduated at the top of his class in 1932, Claude was not given a journeyman’s card like the rest of his classmates. A journeyman’s card would have allowed Claude to be actively employed as a tradesperson. Despite this obstacle, Henry Ford recognized Claude’s talent and he was hired at the trade school. By the 1920s, Ford Motor Company had become the largest employer of African American workers in the country. Although Ford employed large numbers of African Americans, there were limits to how far most could advance. Many African American workers spent their time in lower paying, dirty, dangerous, and unhealthy jobs.

The year 1932 also saw Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company once again revolutionize the auto industry with the introduction of a low-priced V-8 engine. By casting the crankcase and cylinder banks as a single unit, Ford cut manufacturing costs and could offer its V-8 in a car starting under $500, a steal at the time. The affordability of the V-8 meant many customers for Ford, and with that came inevitable complaints—like a noisy rattling that emanated from the engine. To remedy this problem, which was caused by irregular-shaped piston pins, Henry Ford turned to Claude Harvard.

1932 Ford V-8 Engine, No. 1 / THF101039

To solve the issue, Harvard invented a machine that checked the shape of piston pins and sorted them by size with the use of radio waves. More specifically, the machine checked the depth of the cut on each pin, its length, and its surface smoothness. It then sorted the V-8 pins by size at a rate of three per second. Ford implemented the machine on the factory floor and touted it as an example of the company’s commitment to scientific accuracy and uniform quality. Along with featuring Claude’s invention in print and audio-visual ads, Ford also sent Harvard to the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago and to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to showcase the machine.

Piston Pin Inspection Machine at the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago, Illinois. / THF212795

During his time at Tuskegee, Harvard befriended famed agricultural scientist George Washington Carver, who he eventually introduced to Henry Ford. In 1937, when George Washington Carver visited Henry Ford in Dearborn, he insisted that Claude be there. While Carver and Ford would remain friends the rest of their lives, Claude Harvard left Ford Motor Company in 1938 over a disagreement about divorcing his wife and his pay. Despite Ford patenting over 20 of Harvard’s ideas, Claude’s career would be forced in a new direction and over time, the invention of the piston pin sorting machine would simply be attributed to the Henry Ford Trade School.

Despite these many obstacles, Claude’s work lived on in the students that he taught later in his life, the contributions he made to manufacturing, and a 1990 oral history, where he stood by his sentiments that if one put in a honest effort into learning, there would always be a way forward.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Detroit, 1930s, 20th century, technology, radio, manufacturing, making, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, engines, engineering, education, by Ryan Jelso, African American history, #THFCuratorChat

#InnovationNation: Power & Energy

Thomas Edison, engines, alternative fuel vehicles, Ford Motor Company, cars, railroads, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, power, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345, Used by Henry Ford. THF140104

In 1882, 19-year-old Henry Ford had an encounter with this little steam engine that changed his life. Though initially unsure of his abilities, he served as engineer, overseeing the maintenance and safe operation of the engine for a threshing crew organized by Wayne County, Michigan farmer John Gleason. He went on to run the engine for the rest of the season, developing the skills and knowledge of an experienced engineer. This assured Henry Ford that machines--not farming--were his future.

Pictured here with the steam engine are (left-to-right) Hugh McAlpine, James Gleason, and Henry Ford. This photograph was taken in 1920 on the Ford Farm in Dearborn. THF199289

Henry Ford never forgot this engine. Three decades later, as head of the world’s largest automobile company, he set out to find it again, sending representatives out scouring the countryside looking for the Westinghouse steam engine, serial number 345. Finally, one of his men found it in a farmer’s field in Pennsylvania. In 1912, Henry Ford purchased it from Carrolton R. Hayes, and had it completely rebuilt. Thereafter, Henry ran it regularly, often in the company of James Gleason, the brother of the man who originally bought it.

Read more content related to The Henry Ford's 90th anniversary here.

Additional Readings:

- Power by the Quarter

- Looking Back to Move Forward

- 1927 Plymouth Gasoline-Mechanical Locomotive

- Electrical Connection

Henry Ford Museum, farms and farming, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, engineering, engines, power, Henry Ford

Driving Through the Decades at Motor Muster 2018

Only at Motor Muster! The 1st Michigan Fife & Drum Corps passes a 1955 Buick Special Riviera.

Another summer means another car show season. Here at The Henry Ford, that means another Motor Muster. Our 2018 event goes down as one of the most exciting in recent memory, with a host of new activities and experiences – and more than a few great cars, too. Some 700 automobiles, trucks, motorcycles, scooters, bikes and military vehicles filled Greenfield Village with the sights and sounds of mid-20th century motoring. Chevrolet’s long-running small-block V-8 – under the hoods of the 1957 Bel Air and Corvette seen here – is a perfect example of an iconic engine.

Chevrolet’s long-running small-block V-8 – under the hoods of the 1957 Bel Air and Corvette seen here – is a perfect example of an iconic engine.

Our theme this year broke with tradition. Rather than feature one particular make or model, we celebrated “Iconic Engines of Detroit’s Big Three.” Our profiled power plants included Ford’s flathead V-8, which brought horsepower to the masses from 1932-1953; Chevrolet’s small-block V-8, which remained in production, in one form or another, from 1955-2003; and Chrysler’s celebrated hemispherical combustion head engines, first marketed under the “FirePower” name before gaining the better known – and still used – “Hemi” moniker. The broader theme allowed us to make the most of a visit from the Early Ford V-8 Club of America, as well as a consortium of dedicated Mopar owners and fans. Moving under its own power for the first time in several years, The Henry Ford’s 1956 Chrysler 300-B recalled NASCAR’s early days.

Moving under its own power for the first time in several years, The Henry Ford’s 1956 Chrysler 300-B recalled NASCAR’s early days.

Each of these iconic engines was on view in our special display tent across from Town Hall. From The Henry Ford’s own collection came a 60-horsepower variant of the Ford V-8. Our Chrysler 300-B, from the Carl Kiekhaefer team that dominated NASCAR’s 1956 Grand National series, not only sat in the tent but also wowed crowds with Hemi-powered noise during our Saturday afternoon racing Pass-in-Review presentation. We rounded out the tent’s Big Three display with a small-block-powered 1955 Chevy Bel Air courtesy of show participant John Dargel.

The Ford V-8 was an especially appropriate choice for Motor Muster. Some of the engine’s early design work was done by a small group of engineers working out of Thomas Edison’s Fort Myers Laboratory in Greenfield Village. The lab provided the team with privacy and freedom from distraction – and maybe even a little inspiration. Tether cars peaked in popularity in the years surrounding World War II, though newer models – like this 1990s example – continue to be built by enthusiasts.

Tether cars peaked in popularity in the years surrounding World War II, though newer models – like this 1990s example – continue to be built by enthusiasts.

We added a small-scale surprise to the tent this year. Throughout the weekend, visitors could watch our conservators at work on a gasoline-powered tether car. These miniature racers competed against the clock while tethered to a central pivot, or against each other on scaled-down board tracks. The featured car was one of dozens acquired by The Henry Ford from the E-Z Spindizzy Foundation in 2013.

Scenes from the World War II home front came to life at our small-town War Bond drive.

Building on the “historical vignette” concept that debuted at last year’s Old Car Festival, this year’s Motor Muster included period settings for each decade represented by the cars in the show. For the 1930s, we staged a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at the McGuffey School. For the 1940s, we reenacted a home front War Bond drive, circa 1943, along Washington Boulevard. (In keeping with the theme, Spam sandwiches were available for lunch!)

The 1951 General Motors Le Sabre concept car, on loan courtesy of our friends at GM, was a highlight of the “FuturaFair” auto show vignette. GM also provided the 1958 Firebird III.

The 1950s were represented by a Motorama-style auto show in the Village Pavilion. Our “FuturaFair” display included three of that decade’s notable concept cars: the 1951 GM Le Sabre, the 1953 Ford X-100, and the 1958 GM Firebird III. At the Scotch Settlement School, a happy group of revelers enjoyed a suburban-style picnic set in the 1960s. And the Spirit of ’76 reigned at the foot of the Ackley Covered Bridge, where the 1st Michigan Fife & Drum Corps and the Plymouth Fife & Drum Corps performed Bicentennial-themed concerts throughout the weekend.

Badminton kept our Bicentennial vignette lively, while mid-1970s AMC wagons and cars provided atmosphere.

If just looking at cars wasn’t enough, visitors could learn about them either by watching our narrated Pass-in-Review programs at the Main Street grandstand, or by sitting in on one of several presentations in the Village Pavilion. Topics included everything from Ford factory paint methods to the lasting impact of the Chevrolet Corvair. Of course, you could also learn simply by asking the owners about their cars. They enjoy sharing share their stories: where they found the car, why they bought it, and why they love the hobby.

It was another magical weekend filled with good friends, good food, and hundreds of vintage vehicles. And for our 2018 Motor Muster award recipients, it was a winning weekend as well. What better way to welcome another summer?

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, Motor Muster, Greenfield Village, events, engines, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson