Posts Tagged by matt anderson

RadWagon 5 Joins the Bicycle Collection

The RadWagon 5 electric bicycle with an appropriate backdrop, Edison Illuminating Company’s Station A. / Image by Staff of The Henry Ford

Recent visitors to Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation know that bikes are prominent right now. The Bicycles: Powering Possibilities exhibit in the Collections Gallery features seventeen two-wheelers covering two centuries of bicycle history and technology, and it remains on view through February 15, 2026. Our bicycle collection continues to grow, and The Henry Ford acquired a new addition this fall: a RadWagon 5 electric cargo bicycle. It’s the first regular-production e-bike in the museum’s collection. (Our 2015 Ford Mode:Flex is also an e-bike, but it’s strictly a prototype.)

E-bikes, with electric motors to assist with propulsion, represent the most significant shift in the bicycle industry in years. Depending on the design, an e-bike’s motor might either add to the rider’s own muscle power by providing a boost when needed, or it might eliminate the need to pedal altogether. Modern e-bikes are capable of speeds up to 28 miles per hour, and their batteries are good for anywhere from 30 to 60 miles between charges.

While motorized bikes seem like a recent idea, patents for electric bicycles date back at least to the 1890s. But high cost and high weight, combined with low battery range, discouraged serious interest in e-bikes for a century. There was a more fundamental issue too: a widespread and long-held belief among riders and manufacturers that motors violated the very spirit of the human-powered bicycle. In the 1990s, advancing technologies and shifting attitudes began to make e-bikes practical. Ironically, former Ford and Chrysler executive (and consummate “car guy”) Lee Iacocca was a major promoter. In 1997, he founded EV Global Motors and sold about 25,000 e-bikes to consumers.

E-bikes gained a following in Asia and Europe, where bicycling itself is more common, but growth in the United States lagged due to a car-centric culture, a lack of bike lanes and charging infrastructure, and a general perception of cycling as a recreational or fitness activity rather than a regular mode of transportation. Then came COVID-19. Americans got more interested in outdoor activities, and they looked for socially distanced alternatives to carpools and public transit. Stimulated by these unique circumstances, U.S. e-bike sales topped one million units for the first time in 2022 — a significant milestone.

Cargo bikes are designed to haul. The RadWagon 5’s extended rear frame provides room for groceries, packages or — with seats and handlebars — young children. / THF806493

The Henry Ford’s newly acquired e-bike is a product of — and a gift of — Rad Power Bikes of Seattle, Washington. The company was formed by Mike Radenbaugh, whose interest in electric bicycles dates to his teenage experiments with motors and bikes in his parents’ garage. He launched the company in 2007 and introduced the RadWagon e-bike in 2015. With a longer frame, space at the rear for child seats or packages, and a carrying capacity of 350 pounds, the RadWagon cargo bike offered a practical, two-wheeled alternative to the family car. And like an automobile, the RadWagon went through several subsequent generations of technology and design updates. The model at The Henry Ford, a RadWagon 5, debuted in 2024 and boasted improvements like a front suspension fork, hydraulic disc brakes, and an increased cargo capacity of 375 pounds. The bike’s 750-watt motor has a top speed of 28 miles per hour and a range of about 60 miles between charges.

The RadWagon 5’s brake and shift controls resemble those on a traditional bike. Its display screen, near the center of the handlebars, includes a battery-level indicator, a speedometer, and a timer and trip meter, among other functions. / THF806494

E-bikes are still an emerging technology, and the regulations that govern them are evolving. Specific rules vary by state and city, but e-bikes are generally designated as one of three classes that determine where and how they may be ridden. Class 1 e-bikes are limited to 20 miles per hour, and their electric motors work only when the rider is pedaling. Usually, these bikes are allowed on bicycle paths that might otherwise be designated for non-motorized vehicles. Class 2 e-bikes are also limited to 20 miles per hour, but they have throttle controls that activate the motor even if the rider isn’t pedaling. Class 3 e-bikes operate at speeds up to 28 miles per hour, and they may or may not have throttle controls. Class 3 e-bikes are generally allowed in on-road bicycle lanes, but they are not permitted on separate bike paths or multiuse trails. One of the RadWagon 5’s key advantages is that it can be switched between Class 1, 2, or 3 settings depending on the rider’s location or needs.

The RadWagon 5 is an important addition to The Henry Ford’s bicycle collection. It helps us to document the growth of electric bikes and the increasing popularity of cargo bicycles among American riders. (Indeed, some of those rising cargo bike sales are due to electric motors — the power boost making it easier to ride with heavy loads.) E-bike sales are expected to climb at an annual rate of about 15 percent throughout the rest of the decade. It’ll be interesting to see how these machines change our laws, landscapes, and lives in the years ahead.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

The Oldest Cars Shine at 2025 Old Car Festival

Its top down under bright skies, this Ford Model A kept pace with the Torch Lake locomotive at the 2025 Old Car Festival. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pleasant temperatures and sunny skies greeted visitors and participants alike at our 2025 Old Car Festival, held in Greenfield Village on September 6 and 7. More than 750 vintage cars, trucks, motorcycles, and bicycles registered for this year’s event, making for one of the largest festivals in recent years. Throughout the weekend, the village was filled with the sights and sounds of early gasoline, steam, and electric cars all dating no later than 1932.

We choose a special theme for each year’s show. Often it’s a specific make or model, and sometimes it’s a geographic location or style of automobile. This year we went big by celebrating an entire century with our focus on Nineteenth-Century Motoring. The automobile may have defined the twentieth century, but its origins and earliest impacts lie firmly in the 1800s, from Karl Benz’s pioneering Patent-Motorwagen of 1885 to the Duryea brothers’ first series-produced automobile in 1896.

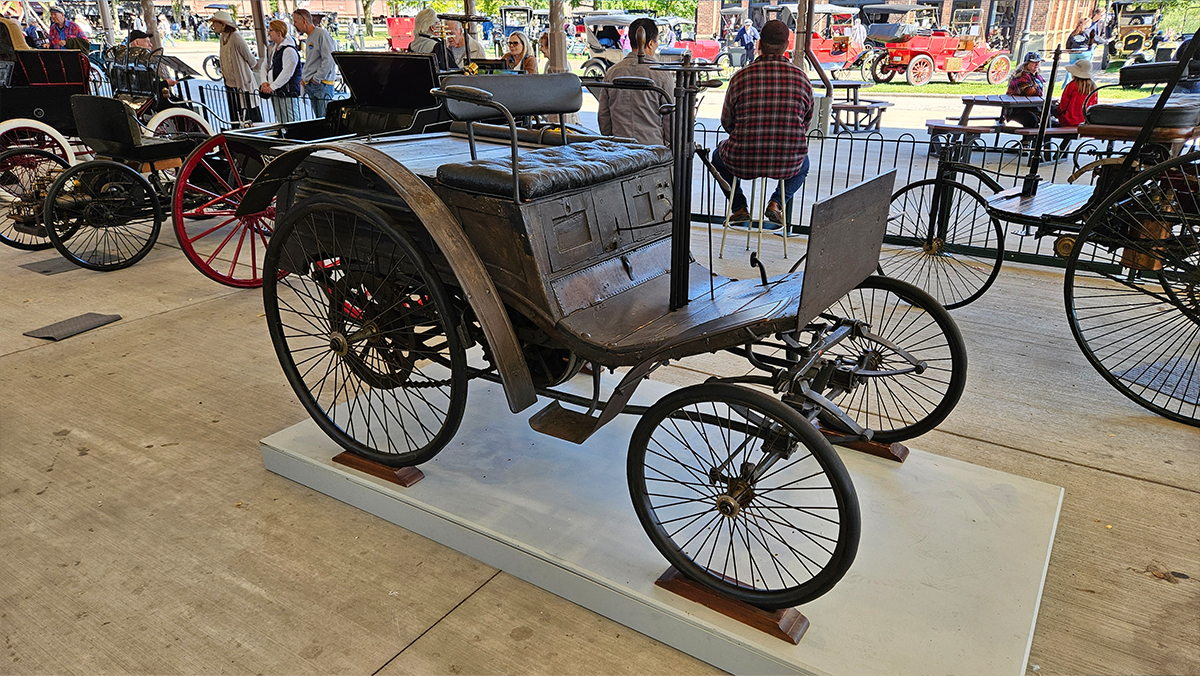

The Henry Ford’s 1893 Benz Velocipede, one of eleven pre-1900 vehicles shown in Detroit Central Market, embodied the festival’s Nineteenth-Century Motoring theme. / Image by Matt Anderson

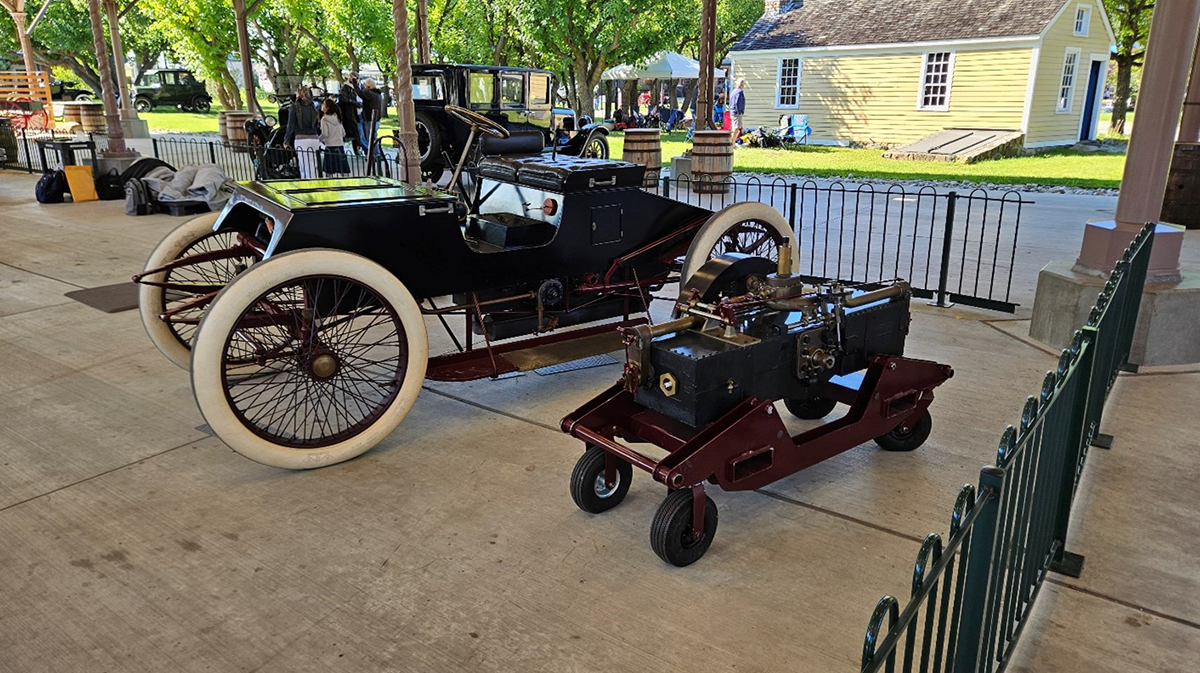

Incredibly, Old Car Festival featured eleven pre-1900 vehicles in Detroit Central Market. Four of them came from The Henry Ford’s own collection including an 1893 Benz Velocipede, our replica of Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle, an 1898 Autocar Runabout, and, perhaps most interesting of all, a conjectural full-size model of George Selden’s Motor Buggy based on his notorious patent first applied for in 1879 and awarded in 1895. Participants added another five vehicles to the mix, including a replica of an Iowa-built 1890 Morrison Electric, an 1896 Riker Electric prototype, an 1897 De Dion-Bouton Tricycle, an 1898 Beeston Quadricycle, and an 1899 Marot-Gardon. Our neighbors at the Automotive Hall of Fame provided two additional vehicles: replicas of the Benz Patent-Motorwagen and Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach’s 1885 Reitwagen motorcycle.

Visitors were treated to a variety of experiences throughout the village. Not far from the entrance, at the Ford Home, the Early Engine Club staged a Farm Power Expo showcasing early tractors and stationary engines, including The Henry Ford’s Pullford farm tractor — created from a Ford Model T using a widely marketed conversion kit. Outside the nearby Bagley Avenue Workshop, presenters demonstrated a replica of Henry Ford’s 1893 Kitchen Sink Engine that represented his first steps in the nascent automotive industry.

Old Car Festival included a number of imports like this 1924 Jowett made in Great Britain. / Photo by Matt Anderson

As is the custom at Old Car Festival, participating vehicles were parked in chronological order throughout Greenfield Village. The earliest automobiles sat near the Armington & Sims Machine Shop near the village entrance, while late 1920s and early 1930s cars had space near the Daggett Farmhouse. The Village Green was reserved for judged cars. Vehicle class awards were given based on authenticity, quality of restoration work and the care with which each car was maintained. First-, second- and third-place prizes were awarded in eight classes, and one overall Grand Champion was selected for the festival. We also presented two Curator’s Choice Awards to two unrestored vehicles. The complete list of our 2025 Old Car Festival award winners is available here.

Bicycles had their own pass-in-review sessions, ably narrated by Bill Smith, on Saturday and Sunday mornings. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Old Car Festival visitors were welcome to explore the village and learn about the cars on their own. As always, participants were eager to share stories and insights about their vehicles. But visitors interested in a more formal presentation could attend pass-in-review sessions throughout the weekend. Vintage vehicles were driven past a set of bleachers on Main Street where expert historians offered commentary on each one. Sometimes the narration included dates and production figures for a vehicle’s manufacturer, and other times it was a broader statement on that car’s impact on technology or design. These narrated sessions also provided an opportunity for us to individually thank our participants by giving them a moment in the spotlight.

Martha-Mary Chapel hosted its own series of special presentations. Automotive historian Andy Dervan shared a look at Ford Motor Company’s monthly publication, Ford Times, which launched in April 1908. Always promotional but often informative, Ford Times included travelogues, customer testimonials and general news on the company and its products. Roadside historian Daniel Hershberger shared insights on automobile touring and camping in the first decades of the 20th century. Not far from the chapel, next to Scotch Settlement School, Hershberger staged an impressive display of vintage camping equipment. Meanwhile, presenter Ray Swetman offered an informative talk in the chapel about Henry Ford’s efforts to finance Ford Motor Company, his third attempt at auto production, in 1903.

The Georgia farmhouse of Amos and Grace Mattox represented the trying Depression years, accented by a well-worn Ford Model TT parked out front. / Image by Matt Anderson

Music featured prominently in this year’s show. Old Car Festival’s 40-year timespan allowed for a variety of musical styles. The corner of Washington Boulevard and Post Road hosted a ragtime street fair, complete with a cakewalk set to syncopated piano rags by Scott Joplin and other giants of the genre. The River Raisin Ragtime Review orchestra joined the festivities on Saturday evening with a concert on Main Street. Throughout the weekend at the Mattox Family Home, Rosa Warner-Jones performed a selection of poignant gospel and blues songs evocative of the Georgia lowlands during the Great Depression. The Village Trio vocal group, the Greenfield Village Quartet and other artists added to the experience.

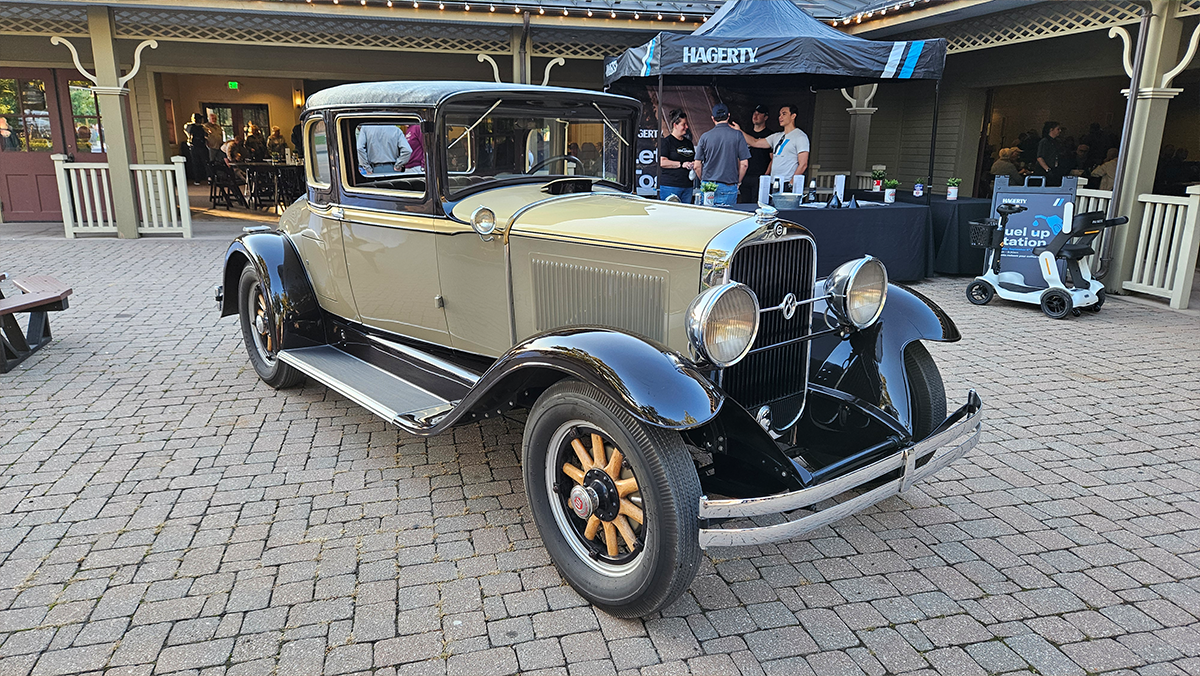

Hagerty’s 1930 Studebaker Victoria coupe drew onlookers at the Lodge. / Image by Matt Anderson

Once again, our friends at Hagerty helped make Old Car Festival the success it was. Not only did they sponsor their terrific youth judging program, in which children 8-10 years old get to view and choose their favorite cars; Hagerty also brought a 1930 Studebaker Commander 8 that fit in perfectly at the show. Hagerty had an active presence near the Herschell-Spillman Carousel with magazines, newsletters and fun promo products available to all comers.

We extend a special thanks to all the participants, presenters, performers and guests who made the 2025 Old Car Festival so special. This one may be in the history books, but you can be sure that we’re already looking forward to next year.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Thunderbird Soars at Motor Muster

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Crowds flocked to Greenfield Village for our 2025 Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Once again Father’s Day weekend brought a favorite event to Greenfield Village. Our 2025 Motor Muster, held June 14-15 and celebrating car culture from 1933 to 1978, featured more than 650 automobiles, trucks, motorcycles, military vehicles, and bicycles. Each Motor Muster features a special theme, and this time our spotlight fell on the Ford Thunderbird, seventy years after the sporty personal car was introduced for the 1955 model year. Thunderbird was a hit over eleven different styling generations through 2005, taking only a brief pause in production from 1998 to 2001.

Detroit Central Market housed Thunderbirds from seven of the car’s eleven styling generations, including a couple of post-1978 examples. / Image by Matt Anderson

We wanted to showcase Thunderbird properly, so our friends at the Water Wonderland Thunderbird Club and the Vintage Thunderbird Club International helped us pull together a selection of some of the best T-Birds pull together a display in Detroit Central Market featuring some of the best T-Birds ever built Detroit Central Market. We had cars from seven of Thunderbird’s eleven generations. Together, they represented the original two-seat “Little Birds” of the mid-1950s, the four-seat “Square Birds” of the late 1950s, the angular “Bullet Birds” of the early 1960s, and the larger luxury-focused Thunderbirds of the early 1970s. From The Henry Ford’s own collection, we included our 2002 Ford Thunderbird, serial number one from the final generation, and our 1962 Budd XT-Bird, which Budd pitched to Ford in hopes of reviving the partnership that had Budd building body components for two-seat T-Birds several years earlier. Our 2002 model wasn’t the only post-1978 T-Bird in the show. We also included a 1994 Thunderbird representing the model’s tenth generation.

Thunderbird Jr. kiddie cars were built in cooperation with Ford from 1955 to 1967. / Image by Matt Anderson

There was another big—make that small— feature in Detroit Central Market. Fourteen Thunderbird Jr. cars added to the fun. Built in Mystic, Connecticut, with the blessing of Ford Motor Company, the Thunderbird Jr. was a scaled-down version of the real thing powered either by an electric motor or a single-cylinder gasoline engine. The junior cars were updated each year to match the look of the real T-Bird, and paint colors were all factory-correct. Smaller Thunderbird Jr. cars, roughly one-quarter size, were intended for children and either given away by Ford dealers or sold by high-end retailers like FAO Schwarz. Larger versions, about one-third size, were used at carnivals and amusement parks. About 5,000 Thunderbird Jr. cars were produced from 1955 to 1967. The fourteen examples at Motor Muster may have been the largest gathering of these little cars since the factory closed nearly sixty years ago.

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pass-in-review programs shared some of the history behind participating cars, like this 1959 Mercury Monterey. / Image by Matt Anderson

From the Armington & Sims Machine Shop to the Daggett Farmhouse, Greenfield Village was packed with historic vehicles. A visitor might easily spend all day walking around to see everything. But for those who preferred to let the show come to them, we offered pass-in-review programs throughout the weekend. As spectators relaxed on shaded bleachers, expert narrators offered insights and expertise on participating vehicles that rolled through in a steady chronological parade. While most of these presentations were organized by decade, we had special sessions devoted to commercial vehicles, race cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and —of course— Thunderbirds.

The cars were complemented by a variety of musical performances and historical vignettes. At Town Hall in the heart of the village, the Village Cruisers offered a selection of 1950s vocal pop perfect for the chrome-and-tailfins era. At the same location, Larry Callahan and the Selected of God Quartet sang stirring freedom songs from the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Their performance offered a wonderful preview of programming to come with the opening of the Jackson Home next year. The 1970s came alive through the Mach I band as they played classic rock hits both at the gazebo near Ackley Covered Bridge and in a larger Saturday evening concert on Main Street.

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Bicycles, like this orange 1955 Evans Sonic Scout, added non-motorized charm to Motor Muster. / Image by Matt Anderson

Pedal-powered transportation is in vogue at The Henry Ford thanks to Bicycles: Powering Possibilities, a temporary exhibit now on view in the Collections Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. There were many bikes to enjoy at Motor Muster, from an eccentric-hub Ingo-Bike like this one in the museum’s collection, to an early 1970s Schwinn Twinn tandem that allowed two cyclists to ride together. And just as Motor Muster vehicles need not be motorized, they don't have to travel on land either. We celebrated outboard boating’s golden age on the shores of Suwanee Lagoon. The fascinating display of boats and engines was titled “Tailfins and Two-Tones,” reflecting a couple of 1950s design fads that were found on land and sea alike.

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

It’s a T-Bird of a different sort: a 1963 Thunderbird Cuddy Cruiser built by Formula Boats. / Image by Matt Anderson

As is tradition, Motor Muster ended on Sunday with our awards ceremony. We presented trophies to vehicles from each decade based on popular-choice ballots submitted by show participants and visitors. We also gave Curator’s Choice prizes to a pair of unrestored vehicles. This year’s unrestored winners included, fittingly, a 1966 Ford Thunderbird and a 1974 Ford Gran Torino. The full list of 2025 Motor Muster winners is available here. The ceremony put a perfect cap on another wonderful weekend.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Bicycles: Powering Possibilities

Bicycles take center stage in The Henry Ford’s newest Collections Gallery exhibit. / Photo by Matt Anderson

The Henry Ford is well known for its transportation collections, including automobiles from the road and race track, innovative early aircraft, and railroad locomotives of staggering size. But our holdings also include an impressive number of two-wheeled vehicles. Several of them are featured in our newest exhibit, Bicycles: Powering Possibilities, located in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s Collections Gallery (on view May 3, 2025 - February 15, 2026).

Bicycles gave many children a sense of independence, whether riding with friends or earning money on a paper route. / THF201333

There’s something almost magical about bicycles, powered by our own effort and ambition. For children, bikes provide an early taste of freedom and independence. For adults, they offer a green alternative for daily commuting, or a recreational escape along paved paths or off-road trails. It was the bicycle that introduced Americans to the power of personal transportation. Cyclists were the first group to lobby for better roads, and 19th-century bicycle technology and manufacturing techniques influenced two of the 20th century’s defining machines: the automobile and the airplane.

This simple Draisine, built about 1818, is an ancestor to the modern bicycle. / THF108100

Bicycles: Powering Possibilities tells the story through 17 significant machines. The oldest and most basic is our circa 1818 Draisine. It’s as simple as can be. Riders simply scooted their feet along the ground to make the vehicle go. Critics at the time said it was nothing more than a “good way to wear out shoes,” but the little Draisine effectively doubled a pedestrian’s pace. More influential, and more recognizable to modern cyclists, is our 1866 Sargent & Company Velocipede. French blacksmith Pierre Michaux is credited with adding foot pedals to the front axle, giving riders the means to move without their feet touching the ground.

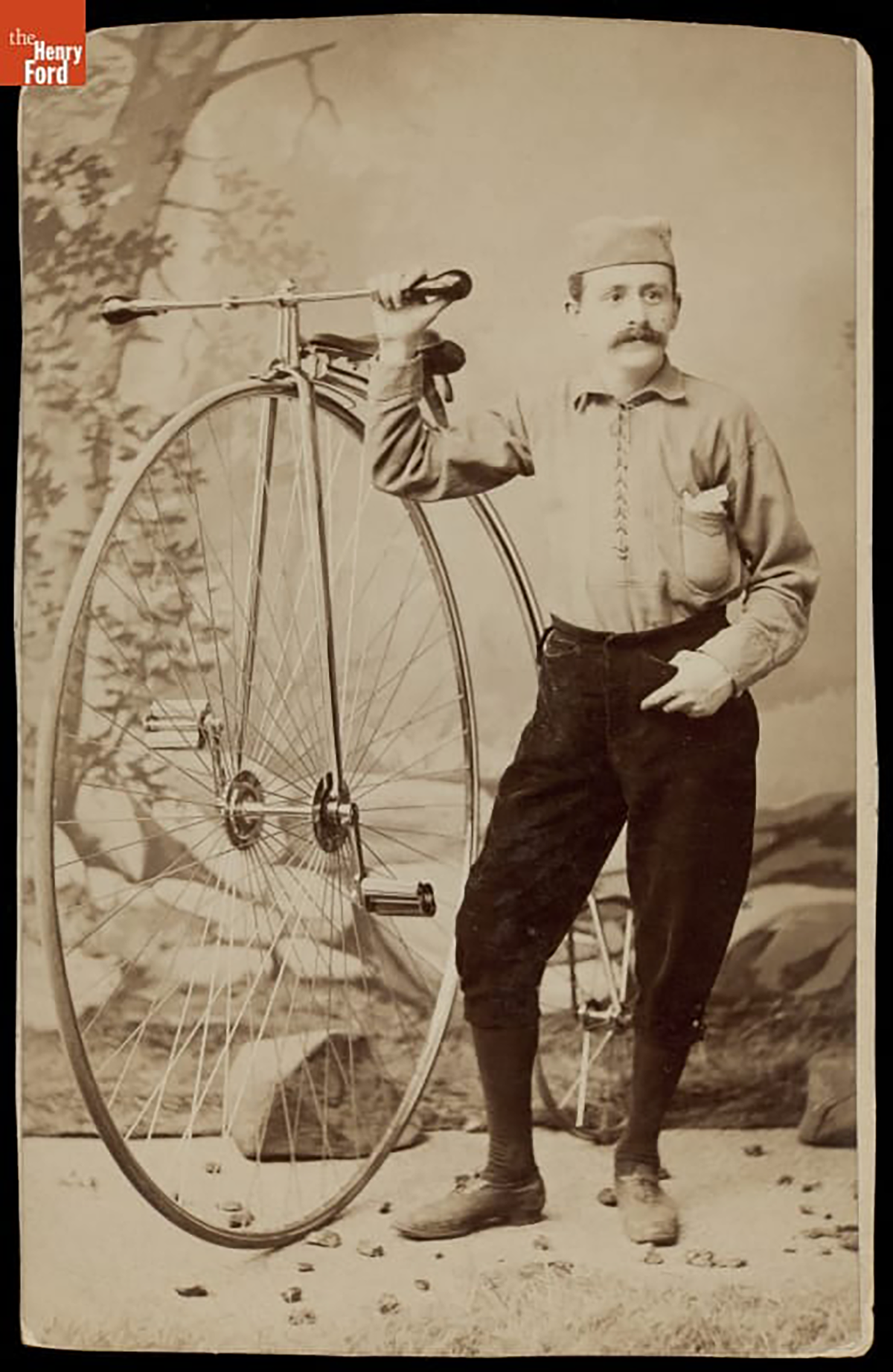

Big wheels increased a bicyclist’s speed and power, but they intimidated new riders. / THF203364

British racer James Moore turned heads in 1870 riding a bicycle with an oversized front wheel. That big wheel allowed Moore to move faster and farther with each turn of the pedals, and the seat’s location above the wheel increased his leverage when pumping his legs. By the end of the decade, high-wheel bikes like our circa 1878 Singer & Company machine were everywhere. But riding a high wheeler required an extra dose of athleticism. Just getting on or off was a challenge, and even experienced riders dreaded tumbling over the handlebars in a “header” accident.

British manufacturer Rover took the next step in the bicycle’s evolution with a new design in 1885. Rover’s “safety bicycle” featured two modestly sized wheels propelled by a chain-and-sprocket drive. The smaller wheels made it easier to climb into the saddle, and the sprockets provided the same mechanical advantage as direct-drive high wheelers. Safety bikes like The Henry Ford’s 1892 Rambler made biking more accessible and ignited a bicycle boom that, by the mid-1890s, saw more than a million new bikes built in the United States each year. At the same time, bicycle competitions grew in popularity both here and abroad. Racers used advanced, lightweight machines like the 1898 Tribune “Blue Streak” to break records and best opponents on tracks, trails, and roads.

All fads run their course, and the 1890s bicycle boom was no different. The turn of the 20th century saw the market flooded with poorly built budget bikes that turned off riders. At the same time, automobiles and motorcycles eclipsed the bicycle’s technical novelty. By 1902, American bicycle production was only a fraction of what it had been a few years earlier.

Adults may have abandoned the bicycle, but children kept riding. Savvy manufacturers shifted toward the youth market, producing children’s bicycles based on adult motorcycles, with flashy colors and stylish accessories that appealed to young riders. Schwinn had baby boomers dreaming about its top-of-the-line Phantom series, while Schwinn and Huffy both later lured the boomers’ Gen X and millennial kids with entry-level BMX bikes.

American cyclists won nine medals at the 1984 Summer Olympics, inspiring a new generation of riders / THF720378

In the early 1970s, lighter multi-speed machines lured American adults back into the saddle. Ten-speed bikes like the 1970 Schwinn Continental were well suited to road riding in a variety of conditions. Within 20 years, bikes with 18, 21 or even 25 speeds were widely available. Today bicycling is as popular as ever in the U.S., and new riders continue to take up the sport thanks to promotional efforts, safety campaigns, and the spread of urban bike lanes and rural recreational trails.

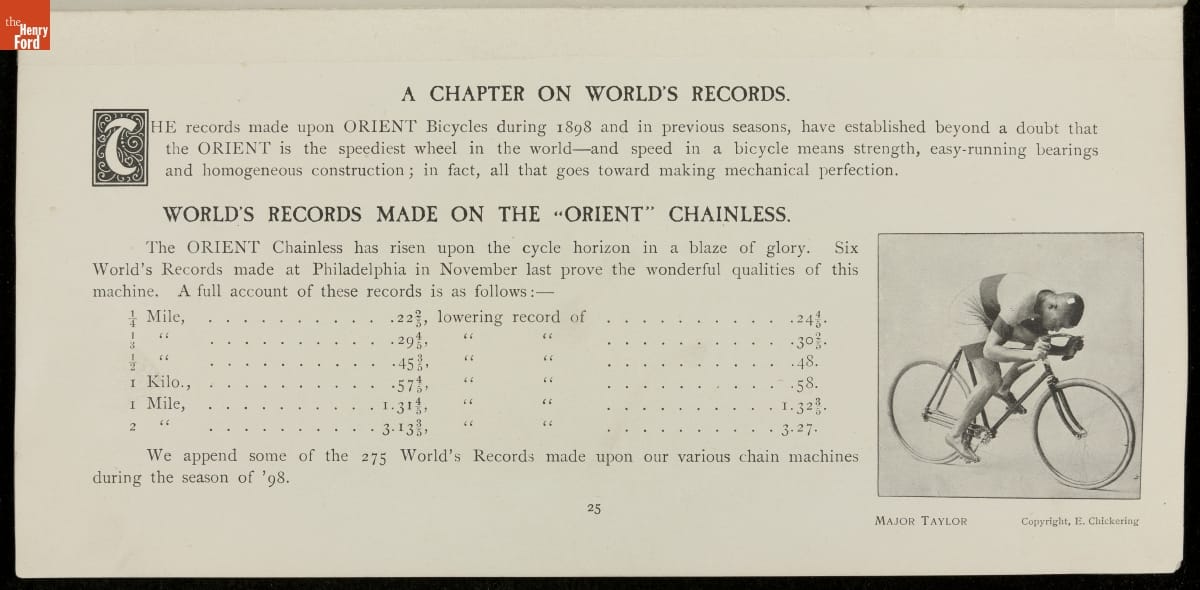

Bike racer Major Taylor broke records and endorsed manufacturers like Orient. / THF207504

Visitors to Bicycles: Powering Possibilities will meet several influential builders, riders, and racers. Albert A. Pope applied early mass-production techniques to bicycle manufacturing at his state-of-the-art factory in Connecticut. Major Taylor wowed audiences in the U.S., Europe and Australia with his speed sprints and, as a Black American, did so in the face of ugly discrimination. Tillie Anderson was praised as one of the best riders of her day and is said to have won all but seven of the 130 competitions she entered. Frank Schwinn and Horace “Huffy” Huffman revived their respective family businesses by building some of the 20th century’s most popular bicycles. Of course, we can’t forget the Wright brothers, whose 1890s bicycle shop gave them the resources to build and fly the world’s first successful airplane.

“Bicycles: Powering Possibilities” includes 17 machines representing 200 years of development. / Photo by Matt Anderson

The exhibit’s interactive experiences let visitors join in the fun. Handling different materials like wood, steel, and aluminum shows how a bike’s weight is affected by its very substance. Sprockets and chains illustrate the mechanical advantages of multiple gear ratios. Spokes with decorations and playing cards demonstrate how young riders have customized their bicycles for generations. Video displays feature bicycle scenes from favorite movies and television shows, while vintage newsreels showcase long-ago bicycle rides and races. Additionally, three point-of-view videos let visitors ride along over mountain trails in Utah, through Manhattan traffic to Times Square, and along Mackinac Island’s tranquil Main Street.

Bicycles: Powering Possibilities is on view in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s Collections Gallery from May 3, 2025, through February 15, 2026. Don’t miss the opportunity to see, study, and celebrate these mechanical marvels that have kept us moving for two centuries.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Exploring the Depths of Our Collections

Preserving the past is resource-intensive, and The Henry Ford actively seeks grant funding to support its mission "to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic objects, stories, and lives from America's traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation." Some of these grants focus on enhancing collections storage, stewardship, and accessibility — both physical and virtual. In late summer 2024, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) awarded The Henry Ford a two-year grant to clean, rehouse, and create digital records for artifacts related to power and energy, mobility and transportation, and communications and information technology.

Building on the progress made by previous grants, this project will focus on approximately 325 artifacts housed in The Henry Ford's Central Storage Building that require attention in these key areas. The Henry Ford is currently investing in upgrades to the HVAC system in the building, which will improve the ability to regulate the storage environment. In conjunction with those improvements, the grant work will address overcrowding and previous environmental issues, which in some cases have led to dirt, mold, and other forms of artifact deterioration. Each artifact will be moved, cleaned, and assessed for conservation needs. Registrar staff will update or create catalog records, working closely with curatorial staff to research additional context.

IMLS grant team members meet to discuss work progress. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

Of the 325 artifacts, about 100 priority artifacts identified by the curators will undergo conservation treatment to digitization standards, will be photographed at high resolution and made available online through The Henry Ford's Digital Collections. Curators and associate curators will create digital content, such as blog posts, to highlight these artifacts. Additionally, curatorial staff will write descriptive narratives for the website, providing essential historical context for public audiences.

The IMLS Collections Specialist takes a reference image of each artifact for the catalog record, such as this 1915 Gentry and Lewis V-8 Automobile Engine for the Model T (left), then, after conservation intervention, Photography Studio staff photographs this priority artifact for publication on digital collections. / Photo by Colleen Sikorski (left), THF802658 (right)

Work on the grant began in the fall of 2024, and the first priority artifact to be conserved is a six-cylinder General Motors 6-71 diesel engine — a legend in its own right. Introduced by General Motors' diesel engine division in 1938, the two-stroke unit powered everything from farm tractors and stationary generators to trucks and buses (including the 1948 GM bus on which Rosa Parks made her historic stand). GM produced variants with two, three, four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen, and twenty-four cylinders, practically guaranteeing there was a Detroit Diesel in whatever size and with whatever horsepower a customer required.

For 40 years, this GM 6-71 engine provided faithful service aboard Jacques Cousteau's ship Calypso / THF802646

The Henry Ford's Detroit Diesel just so happened to be used on one of the most celebrated scientific vessels of the 20th century: Calypso, the former World War II minesweeper converted into a floating laboratory by French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau. From 1950 through 1997, Calypso traveled the world's oceans for Cousteau's research, and for shooting many of his documentary television series and films. Calypso even visited the Great Lakes in 1980, when it traveled from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to Duluth, Minnesota, some 2,300 miles away.

It's important to note that The Henry Ford's engine was not Calypso's source of propulsion. The ship's propellers were driven by two eight-cylinder General Motors diesel engines. Our six-cylinder engine was one of two units that ran the generators that produced electricity. Our engine didn't make the boat go, but it kept the lights on — arguably just as important a task. Of course, it wasn't just lights. Calypso's electric generators powered pumps, hydraulic systems, steering mechanisms, radar and navigation devices, and video equipment, among other necessities.

By the time our engine was decommissioned in 1981, it had been used on Calypso for 40 years, with an estimated 100,000 service hours under its belt. Calypso received two brand-new Detroit Diesel engines as part of a wider refurbishment in anticipation of a voyage to the Amazon River. General Motors gifted the decommissioned engine to The Henry Ford in 1986.

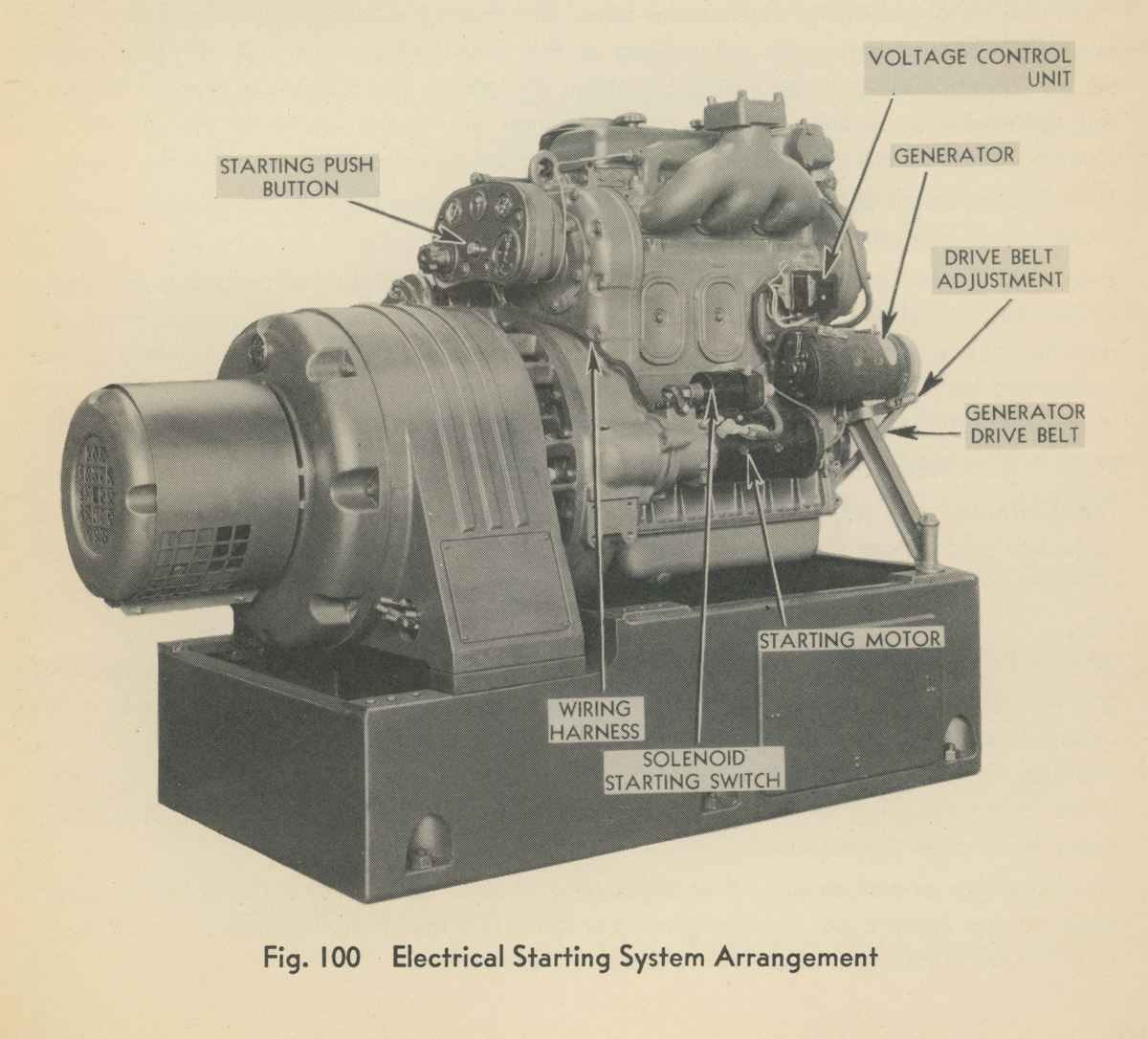

Vintage illustrations, like this one from a 1939 GM manual, guided efforts to conserve the Calypso engine. / THF721888

Through the IMLS grant project, conservators were able to clean the engine of accumulated dirt and dust, treat worn paint, and stabilize damaged gauges and controls. We were also able to replace a long-missing panel surrounding the starter button. Using period General Motors catalogs and manuals in the Benson Ford Research Center, we were able to design and 3D-print a new surround. Once the panel was painted to match, it became visually indistinguishable from the engine's original metal components. (Conservator notes, and inscriptions on the pieces themselves, identify replacement parts so as not to cause confusion in the future.) With that work done, the engine was photographed and given a new and much improved set of digital images on the website.

The Calypso Detroit Diesel is only the first of many important artifacts that will benefit from the IMLS grant and our ongoing work in the Central Storage Building. Stay tuned for future stories. It's a project that promises to be its own voyage of discovery.

This blog was produced by Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, and Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Hands-On History at the Texaco Service Station Experience

All-new interactives await guests of all ages and abilities in the reimagined Texaco Service Station Experience. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Young visitors to The Henry Ford will find a new group of interactive experiences in the reimagined service garage at our Texaco Service Station. Thanks to a grant from the Michigan Arts and Culture Council, we've been able to redesign and reopen this space that had been closed since 2018. Our Texaco Service Station Experience is more inclusive and accessible than ever before, with activities geared to guests of all abilities and varying age groups.

The new interactives are based on the actual work that took place in automotive service garages across the United States throughout the mid-20th century. Each activity is rooted in Model i, The Henry Ford's signature learning framework focusing on the actions and habits of innovators. Six concepts are highlighted in the garage: Diagnose, Assemble, Inspect, Maintain, Repair and Test.

Guests build electrical circuits and find the right tool for the job in the Test and Repair interactives. / Photo by Matt Anderson

“Test” is centered on the electrical systems that power everything from a car's spark plugs to its horn. In this activity, guests make an electrical circuit using puzzle pieces connecting the battery with the horn, headlights and turn signals. Build the circuit correctly and you’ll see these various components work. But if they don't power up as expected, then you can go back to your circuit to find and fix the wrong puzzle pieces. Next to “Test” is the “Repair” station, where visitors discover valve covers with various fasteners. The challenge is to match nuts, bolts and screws with the tools that fit them, whether it's an open-end wrench, a socket wrench or a flathead or square screwdriver.

Guests can perform routine maintenance tasks like checking tire pressure or oil level. / Photo by Matt Anderson

The “Maintain” activity contains three routine maintenance tasks familiar to any driver: checking tire pressure, oil level and battery charge. Guests push down on a T-handle plunger and watch a tire pressure gauge as it moves between "low" and "high." When the center of the gauge lights up, you know you've got it right. Pull on a dipstick to check engine oil and you're rewarded with an amusing slide whistle glissando. And in a nod to the growing popularity of electric vehicles, guests can charge a pair of EV batteries using a paddle charger inspired by the type used with the General Motors EV1.

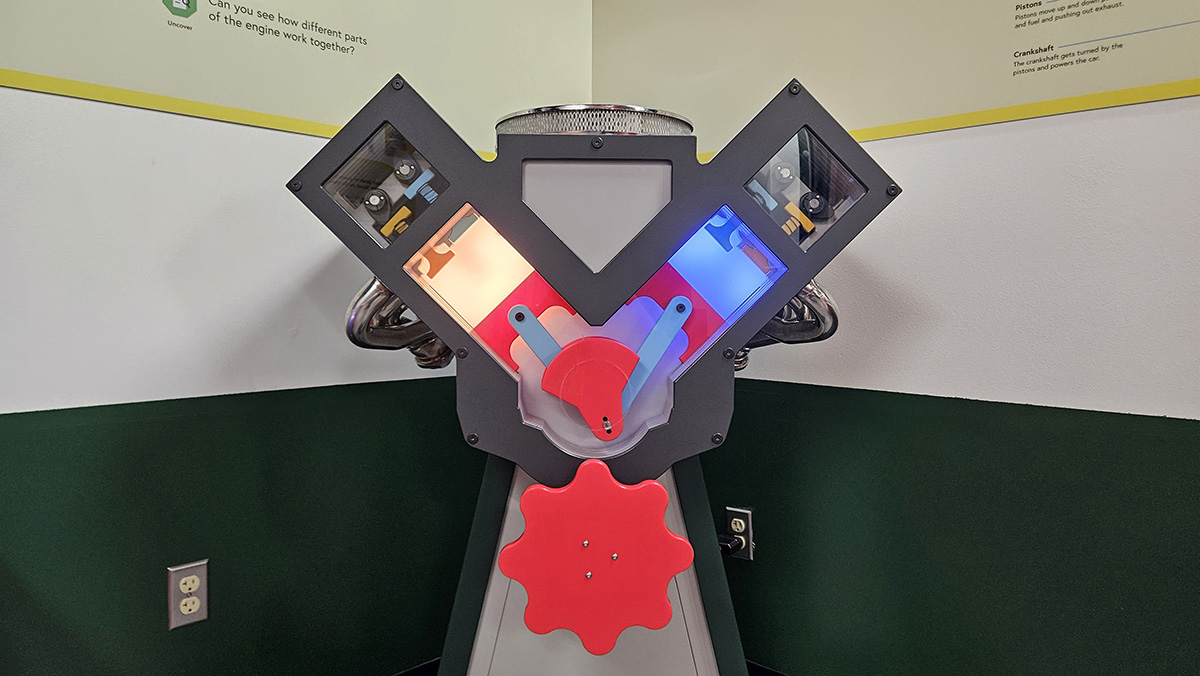

The basic workings of a four-stroke internal combustion engine are shown by this cutaway model. / Photo by Matt Anderson

The "Inspect" area includes an interactive that might appeal to adults as much as to children. We've created a cutaway model of a V-8 engine. Spin the red dial under the crankshaft and you can watch as pistons move up and down and valves open and close. What’s more, colored lights flash in sequence to illustrate ignition and exhaust within the two visible cylinders. As sophisticated as modern internal combustion engines are, most still use the same four-stoke cycle developed by Nikolaus Otto in the 1870s.

Guests assemble major automobile components in this puzzle activity. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Automobiles depend on multiple systems that work together to move the car. Young visitors discover some of the more significant ones in the service station's “Assemble” zone. Large puzzle pieces represent things like the engine, battery, driveshaft, muffler and tires on a typical car. Moving these pieces into their proper locations helps to show how they all work together to keep motorists moving down the road.

Youngsters can examine worn tire treads at this interactive station. / Photo by Matt Anderson

The station's "Diagnose" area is where the rubber meets the road. Children are invited to inspect a set of tires, looking for damage like a puncture from a nail or wear to the tread. This activity is a good reminder that today's highly reliable cars and trucks still depend on components that wear out with use and need replacing.

This scaled-down 1964 Ford Falcon replica hangs over the garage, allowing young visitors to see the car's undercarriage. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Visitors might recognize an old favorite returning from the previous version of the Texaco garage. Our scaled-down replica of a 1964 Ford Falcon, which previously sat on the garage floor, now hangs from the ceiling as if raised on a lift. This new placement lets visitors get a look at the car's undercarriage, as well as major components like the drivetrain and exhaust system. It all neatly mirrors the nearby "Assemble" puzzle activity.

Each of these new interactives was conceived, designed and built based on guest feedback and guidance from The Henry Ford's own accessibility advisory group. The activities bring new ideas and educational opportunities to the Texaco garage, and they make more efficient and effective use of the space. We're eager to share the reimagined Texaco Service Station Experience with everyone.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Celebrating the Chrysler Centennial at Old Car Festival 2024

Chrysler cars, like this 1927 Imperial Sportif from The Henry Ford’s collection, were honored at this year’s Old Car Festival. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Automotive enthusiasts, history lovers, and folks just looking to have a good time descended on Greenfield Village on September 7-8, 2024, for Old Car Festival, our annual celebration of early American motoring circa 1900 to 1932. Nearly 750 cars, trucks, motorcycles, fire engines, and bicycles gathered for the show favored with sunny skies and fall-like temperatures. Attendees enjoyed good food, entertaining music and programs, and the incomparable kinetic energy of all those early gas, steam, and electric vehicles motoring through the village.

This 1930 Chrysler Series 70 was among the vehicles highlighted in Detroit Central Market. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Each year at Old Car Festival we honor a specific make or model, or we celebrate a significant anniversary. Considering that Walter P. Chrysler introduced the first Chrysler-badged cars in 1924, the Chrysler Centennial was an obvious choice for our 2024 theme. Chrysler got his start as a railroad machinist, but his abilities and industry contacts led to a job as Buick’s production head in 1911. Chrysler grew frustrated with General Motors boss William C. Durant – who enjoyed building corporations more than cars – and left in 1919. Never one to sit still, Chrysler reinvented himself as a turnaround manager, first at ailing Willys-Overland then at Maxwell. Chrysler effectively transformed Maxwell into his own Chrysler Corporation, and within five years he expanded it into a full-line automaker by purchasing Dodge Brothers and introducing mid-priced DeSoto and low-priced Plymouth.

Our operating replica of Henry Ford’s 1901 “Sweepstakes” race car was in Detroit Central Market, alongside a separate copy of its 2-cylinder, 539-cubic-inch engine. / Photo by Matt Anderson

We honored Chrysler the man as much as Chrysler the company with a display in Detroit Central Market that covered all phases of his career. Several Old Car Festival participants kindly lent their own cars to the exhibit including a 1913 Buick 31, a 1920 Overland 4, a 1925 Maxwell 25-C, and various Chrysler models from 1927 to 1931 (including The Henry Ford’s own 1927 Chrysler Imperial Sportif). The special display was rounded out with a 1931 Plymouth PA and a 1932 Dodge Brothers DL.

Narrated pass-in-review sessions provided a moment in the spotlight for participating cars, like this 1923 Studebaker Big Six. / Photo by Matt Anderson

For those who preferred to let the action come to them, Old Car Festival included several pass-in-review programs on Saturday and Sunday. Attendees could grab a seat in the bleachers and listen as experts like Andrew Beckman, archivist at the Studebaker National Museum, and Derek Moore, curator of collections at the Lane Motor Museum, provided commentary on passing vehicles. Folks interested in pedal-powered transportation could listen as bicycle historian Bill Smith narrated programs featuring high-wheel and safety bikes from the mid-19th century into the early 20th century.

The corner of Maple and Post hosted a Ford Model T pickup and Model A roadster alongside a 1925 Franklin sedan and a 1931 Chevrolet pickup. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Beyond pass-in-review, the weekend included two special presentations in Martha-Mary Chapel. Bob Casey, retired curator of transportation at The Henry Ford, spoke about Fred Zeder, Owen Skelton and Carl Breer, the “Three Musketeers” who designed the first of Walter Chrysler’s eponymous cars – and many more thereafter. Andy Dervan, a volunteer with our Benson Ford Research Center, presented on Ford Times, Ford Motor Company’s promotional magazine published from 1908 to 1917. Meanwhile, roadside America historian Daniel Hershberger literally set up camp near Scotch Settlement School where he presented on early auto camping throughout the weekend.

Acetylene lamps like those on this 1911 Metz lit the way during the Saturday evening gaslight tour. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Saturday evening brought its own special magic with a concert of period music by the River Raisin Ragtime Revue, and the ever-popular gaslight tour in which cars ignited their vintage acetylene lamps and paraded through the twilight. The evening festivities concluded with a Dixieland-style parade to the exit gates led by the Tartarsauce Traditional Jazz Band. Additional weekend music offerings included ragtime piano performances, blues from Rev. Robert Jones, vocal pop from the Village Trio and the Greenfield Village Quartet, and selections from the Masters of Music band and the Village Strings.

Small engines, including the one powering this early 1930s Maytag washing machine, were demonstrated at the Ford Home. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Automobile engines weren’t the only featured powerplants. Once again in 2024, the Early Engine Club put together a farm power expo at the Ford Home. Antique hit-and-miss engines, a Ford Model T powering small machines, and even a Model T converted into a tractor demonstrated the internal combustion engine’s abilities beyond motorized transportation. At the nearby Bagley Avenue Workshop, our own presenters regularly demonstrated a replica of Henry Ford's "Kitchen Sink” Engine, which powered Ford’s early ambitions toward automobile manufacturing.

This 1916 Ford Model T, still running and still in the same family 108 years later, won a Curator’s Choice award. / Photo by Matt Anderson

As is a longstanding tradition, this year’s Old Car Festival included several cars that were judged for vehicle class awards based on authenticity, quality of restoration work, and care with which each car was maintained. First-, second-, and third-place prizes were awarded in eight classes, and one overall Grand Champion was selected for the festival. This year’s Henry Austin Clark, Jr., Grand Champion Award went to a 1932 Chevrolet Confederate Phaeton. We also presented two Curator’s Choice Awards to the best-preserved unrestored vehicles. Winners included a 1913 Oakland Model 40 Touring and a 1916 Ford Model T Touring. The complete list of our 2024 Old Car Festival award winners is available here

Old Car Festival is a tradition. This photo and banner are from the 1956 show, attended by a 1924 Dodge Brothers Series 116 that was here again in 2024. / Photo by Matt Anderson

We like to think that history comes alive in Greenfield Village every day, but rarely are the sights, sounds and smells of the past so fully resurrected as they are with the veteran motor vehicles of Old Car Festival. It’s an experience to savor year after year.

Matt Anderson is curator of transportation at The Henry Ford.

Protecting Pet Passengers with Sleepypod

Sleepypod carriers are designed to protect pets while traveling inside the family car. / THF185389

Improvements in automotive safety came gradually. Dodge Brothers crashed its early cars into brick walls to evaluate their strength during the mid-1910s. Ford offered laminated safety-glass windshields on its Model A cars in the late 1920s. And Chrysler and Plymouth models featured hydraulic brakes from their introductions in 1924 and 1928, respectively. But focus on seat belt use and scientific crash testing with anthropomorphic dummies didn’t come until the 1950s.

Continue ReadingFerris Bueller’s Faux Ferrari: A Replica with Real History

Like an actor cast in a role, this 1985 Modena Spyder California was chosen to play the part of a Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder in the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. / Photo by Matt Anderson

For those who haven’t visited Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in recent months, we have a wonderful new display space created in partnership with the Hagerty Drivers Foundation. Each year, we’ll share a couple of significant automobiles included on the foundation’s National Historic Vehicle Register. The (currently) 32 vehicles on the register each made a lasting mark on American history—whether through influence on design or engineering, success on the race track, participation in larger national stories, or starring roles on the silver screen.

Our first display vehicle is Hollywood through and through. It’s a “1961 Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder” (those quotes are intentional) used in the 1986 Gen-X classic Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Those who’ve seen the film know that the car is a crucial part of the plot—ferrying Ferris, Sloane Peterson, and Cameron Frye around Chicago; threatening to expose their secret skip day; and forcing a difficult conversation between Cameron and his emotionally distant father.

In true movie fashion, though, not all is what it appears to be.

This 1958 Ferrari 250 GT California is the real thing, as featured in Henry Ford Museum’s Sports Cars in Review exhibit in 1965. / THF139028

The Ferrari 250 is among the most desirable collector cars in the world. GT street versions sell at auction for millions of dollars. And GTO competition variants—well, the sky’s the limit. Even in the mid-1980s, these autos were too pricey for film work—particularly when the plot calls for the car to be (spoiler alert) destroyed. Instead, Ferris Bueller director John Hughes commissioned three replicas for the shoot: two functional cars used for most scenes, and a non-runner destined to fly out the back of Mr. Frye’s suburban Chicago garage.

Replica cars were nothing new in the 1980s. For years, enterprising manufacturers had been offering copies of collector cars that were no longer in production and too expensive for most enthusiasts. The coveted Duesenberg Model J is a prime example, having been copied by replica manufacturers for decades. Some replica cars were more about convenience than cost. Glassic Industries of West Palm Beach, Florida, produced fiberglass-bodied copies of the Ford Model A with available niceties like automatic transmissions and tape decks. Occasionally, the line between “real” and “replica” got blurry. Continuation cars like the Avanti II (based on Studebaker’s original) or post-1960s Shelby Cobras (based on Carroll Shelby’s racing sports cars) were sometimes built with formal permission or participation from the original automakers.

So, if the Ferris Bueller car at The Henry Ford isn’t a real Ferrari, then what is it?

The replica’s builder, Modena Design & Development, was founded in the early 1980s by Californians Neil Glassmoyer and Mark Goyette. When John Hughes read about Modena in a car magazine, he called the firm. As the story goes, Glassmoyer initially hung up on the famous writer/director—believing that it had to be a prank. Hughes phoned again, and Modena found itself with a desirable movie commission. Paramount Pictures, the studio behind Ferris Bueller, leased one car and bought two others.

The Modena replicas featured steel-tube frames and Ferrari-inspired design cues like hood scoops, fender vents, and raked windshields. While the genuine Ferrari bodies used a blend of steel and aluminum components, Modena’s bodies were formed from fiberglass—purportedly based on a British MG body and then fine-tuned for a more Ferrari-like appearance.

The replica Ferrari’s V-8 was sourced from a 1974 Ford Torino, not too different from these 1973 models. / THF232097

The most obvious differences were under the cars’ skin. Rather than a 180-cubic-inch Ferrari V-12, the Modena at The Henry Ford features a 302-cubic-inch Ford V-8 (originally sourced from a 1974 Ford Torino). While the Ford engine was rated at 135 horsepower from the factory, this one has been rebuilt and refined—surely capable of greater output now. And instead of the original Ferrari’s four-speed manual gearbox, the Modena has a Ford-built three-speed automatic transmission. (According to lore, actor Matthew Broderick wasn’t comfortable driving a manual.)

After filming wrapped, the leased car was sent back to Modena’s El Cajon, California, facility. After some work to repair damage from a stunt scene, the car was sold to the first in a series of private owners. By 2003, this beloved piece of faux Italiana/genuine Americana had been relocated to the United Kingdom. The current owner purchased it at auction in 2010 and repatriated the car to the United States. The Modena was much modified over the years, so the current owner had it carefully restored and returned to its on-screen appearance—as you see it today.

Imitation can be the sincerest form of flattery, but it can also be the quickest route to a lawsuit. Following the release of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Ferrari sued Modena Design & Development (along with other replica builders). The matter was settled out of court when Modena agreed to make some minor changes per the Italian automaker’s specifications. Replica production then resumed for a few more years.

The Modena Spyder California may not be a real Ferrari, but it’s certainly a real pop-culture icon. That’s reason enough to include it on the National Historic Vehicle Register, and to celebrate it at The Henry Ford.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford Museum, Europe, 1980s, 20th century, Illinois, California, by Matt Anderson, popular culture, movies, cars

Early American Luxury at 2022 Old Car Festival

Banners with vintage Lincoln artwork welcomed visitors to the 2022 Old Car Festival at Greenfield Village. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

We observed a beloved late-summer tradition September 10–11, 2022, with Old Car Festival, our annual celebration of automobiles built between the 1890s and 1932. First held in 1951, Old Car Festival is the longest-running antique automobile show in the United States. (Though we should probably put an asterisk on that, thanks to 2020, when Old Car Festival—like most events—was canceled.)

Luxury was often synonymous with a higher cylinder count. Cadillac delivered with this 1915 V-8 touring car. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Each year, we turn our spotlight on a special make, model, individual, or theme. February 2022 brought the 100th anniversary of Ford Motor Company’s acquisition of Lincoln Motor Company, so it seemed fitting to feature the broader subject of “Early American Luxury.” (We’d already celebrated Lincoln specifically at this year’s Motor Muster.) Certainly, this theme includes Lincoln, but it also encompasses names like Packard, Cadillac, LaSalle, Pierce-Arrow, and Peerless. These are the marques that defined the very term “luxury car” in the early decades of the 20th century.

Detroit Central Market housed a selection of luxury vehicles from show participants and from The Henry Ford’s own collection. / Photo by Matt Anderson

This year was our first opportunity to incorporate the Detroit Central Market building into Old Car Festival activities. We took advantage of the spacious new structure to show select upmarket American cars drawn from show participants and from The Henry Ford’s own collection. Among the museum’s cars on view were a 1915 Cadillac Type 51 touring car, representing the first mass-produced V-8 automobile, and a 1923 Lincoln Model L touring car that once belonged to Thomas Edison. We also showed our 1922 Detroit Electric coupe. The little coupe might not have seemed so impressive alongside the big touring cars, but there was a time when electric automobiles were purposely marketed to well-to-do women.

This 1915 Packard Twin Six (Packard’s term for its V-12 engine) embodies our “Early American Luxury” theme. / Photo by Matt Anderson

Several magnificent participant cars rounded out our Central Market display. From Packard, we had a 1915 Twin Six touring car and a 1927 Series 626 sedan. From Franklin, we had a 1931 Series 151 sedan. Auburn—part of E.L. Cord’s Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg empire—was represented by a pair of beautiful 1929 models, including a cabriolet and one of the company’s beloved boat-tail speedsters. Our special exhibit wasn’t limited to exclusive marques. Luxury cars for customers of (relatively) more modest means were represented by a 1928 Studebaker President sedan and a 1930 LaSalle coupe.

Model T cars, wagons and trucks were everywhere at Old Car Festival, including this 1924 depot hack parked near Sarah Jordan Boarding House. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

We had more than 730 vehicles registered for this year’s show. Automobiles, station wagons, trucks, bicycles, and even a few military vehicles were spread throughout Greenfield Village over the weekend. Visitors could enjoy the sights and sounds of a 1910s ragtime street fair along Washington Boulevard. They could attend a 1920s-era community garden party near Ackley Covered Bridge. They could watch the Canadian Model T assembly team put together a Ford automobile in mere minutes. Or they could hear about wartime struggles on the Western Front outside Cotswold Cottage. At the Ford Home, near the village entrance, Old Car Festival visitors could take in an exhibition of tractors and internal-combustion engines that took some of the backbreaking labor out of early-20th-century farming. For festival participants in a matrimonial mood, our friends at Hagerty arranged a Drive-Thru Vow Renewals experience. Registered show-car owners could drive their antique vehicles past the makeshift altar in front of Edison Illuminating Company’s Station A and “re-light” their nuptials.

Martha-Mary Chapel provided an inspiring backdrop for cars on the Village Green. It also housed a series of special programs throughout the weekend. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

Speaking of altars, Martha-Mary Chapel hosted several programs and presentations during Old Car Festival. Tom Cotter, author and host of the popular web series Barn Find Hunter, presented twice during the weekend. On Saturday, he went behind the scenes of his car-seeking show with “A Barn-Finding Life.” On Sunday, Cotter recalled the 3,000-mile journey chronicled in his book Ford Model T Coast to Coast. On both days, longtime festival participant Daniel Hershberger discussed early auto touring and roadside camping. Hershberger dedicated his talks to the memory of Randy Mason, a former curator of transportation at The Henry Ford who passed away earlier this year. Also on both days, historian Joseph Boggs looked at the fascinating relationship between automobiles and 1920s Prohibition. Cars factored into both sides of the equation—used by rumrunners and law enforcement officers alike.

Of special interest were two panel discussions on early American luxury cars, held on Saturday and Sunday. Through the generous support of the Margaret Dunning Foundation, we brought together three experts in the field: Bob Casey, retired curator of transportation at The Henry Ford; David Schultz, president of the Lincoln Owners Club; and Matt Short, former curator at the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Automobile Museum and former director of America’s Packard Museum. Our panelists discussed the innovators, manufacturers, and automobiles that defined luxury motoring into the 1930s. Their Sunday session was livestreamed and can be viewed here on The Henry Ford’s Facebook page.

Select participating vehicles at Old Car Festival were judged for various class awards. From those winners, one grand champion was selected each day. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

Visitors may not be aware of a special distinction (apart from chronology) that separates Old Car Festival from our Motor Muster show. Participants at Old Car Festival can choose to have their vehicles judged by a team of vintage-automobile experts. The judges determine Vehicle Class Awards based on authenticity, quality of the restoration work, and care with which each car is maintained. First-, second-, and third-place prizes are awarded in 11 different classes. One overall Grand Champion is selected on each day of the festival. Additionally, two Curator’s Choice Awards are presented to unrestored vehicles, and guests and participants are invited to vote for their favorites in the People’s Choice Awards. The full list of our 2022 award winners may be viewed here.

Old Car Festival includes trucks, too. Commercial vehicles line Christie Street during the event. / Photo by RuAnne Phillips

Great crowds, good weather, and impressive vehicles made for a perfect show in 2022. While it’s always hard to say goodbye to summer, Old Car Festival is certainly a fine way to do it. We look forward to next year’s event already.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2020s, Old Car Festival, luxury cars, Greenfield Village, events, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson