Beyond the Peanut: Food Inspired by Carver

George Washington Carver's Graduation Photo from Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm (now Iowa State University), 1893 / THF214111

George Washington Carver and Food

George Washington Carver (1860s–1943) was born near the end of the Civil War in Missouri. He studied plants his entire life, loved art and science, earned two agricultural science degrees from Iowa State University, and shared his knowledge broadly during his 45-year-career at Tuskegee Institute. He urged farm families to care for their land. Today we call this regenerative agriculture, but in Carver’s day it amounted to a revolutionary agricultural ethic.

Carver’s curiosity about plants fueled another revolution as he promoted hundreds of new uses for things that farm families could grow and eat. Cookbooks inspired him to adapt, and he worked with Tuskegee students to test and refine recipes. Then he compiled them in bulletins that stressed the connection between the environment and human health.

Today, our chefs at The Henry Ford are inspired by Carver’s dozens of bulletins and hundreds of recipes for chutneys, roast meats, salads, and peanut-topped sweet rolls.

Some Possibilities of the Cow Pea in Macon County, Alabama, a 1910 bulletin by Carver featuring recipes. / THF213269

Developing Modern Carver-Inspired Recipes

All Natural Pork with Peanut Plum Sauce at Plum Market Kitchen.

Carver is known to most of us for his many uses for the peanut. The Henry Ford’s culinary team looks to go beyond that, knowing that there is so much more to his legacy. Cultural appropriation is a hot topic in the world of food service today, but as a public history institution, we recognize that food is culture, and we are committed to authentic representation of a variety of food traditions. We are constantly collaborating and developing new recipes in consultation with our curators, who provide expert understanding and context. Part of the mission that drives our chefs is to understand the full story, and to help all our guests complete that experience as well.

Carver-Influenced Menu at Plum Market Kitchen

Kale, Roasted Peanut, and Pickled Red Onion Salad with Molasses Vinaigrette at Plum Market Kitchen

Many aspects of Carver’s legacy are woven into a modern menu at Plum Market Kitchen at The Henry Ford. Today, the ideas of all-natural, healthy, and organic have become “tag lines” to sell you food. However, for Carver, and for Plum Market Kitchen, these have always been a driving ideology. Together, The Henry Ford and Plum Market Kitchen have taken inspiration from many of Carver’s recipes—always looking to honor and continue his legacy.

Digging Deeper into Carver’s Legacy at A Taste of History

Spring offerings from George Washington Carver's recipes at A Taste of History.

While our new recipes at Plum Market Kitchen are inspired by Carver, with modern adaptations, our new offerings in A Taste of History are more directly drawn from Carver’s own recipes and the ingredients he used. Spring offerings at A Taste of History include the following—click through for recipes to try at home.

- Brined and Roasted Chicken

- Tomato Chili Sauce

- Sweet Potato Hash

- Collard Greens with Smoked Turkey

- Peanut Roll Cake with Jelly

Learn More

Farmhouse Roasted Sweet Potatoes at Plum Market Kitchen.

If you’d like to further explore the life and work of George Washington Carver, issues surrounding food security, historic recipes, or dining at The Henry Ford, here are some additional resources across our website:

- Take a closer look at Black empowerment through Black education with the microscope used by agricultural scientist George Washington Carver during his tenure at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

- Throughout Carver’s life, he balanced two interests and talents—the creative arts and the natural sciences. Find out how each influenced the other.

- Learn more about the history of the George Washington Carver Cabin in Greenfield Village.

- Explore artifacts, photographs, letters, and other items related to Carver in our Digital Collections.

- Food security links nutritious food to individual and community health. Explore this concept through the collections of The Henry Ford in this blog post, which includes Carver’s work.

- Find out what a food soldier is, as well as how food and nutrition relate to issues of institutional racism and equity for African Americans.

- Explore historic cookbooks and recipes from our collections.

- Get up-to-date information about dining options in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village.

Eric Schilbe is Executive Sous Chef at The Henry Ford. Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, African American history, George Washington Carver, restaurants, by Eric Schilbe, by Debra A. Reid, recipes, food

Driven to Win: Dawn of Racing

Lorraine-Detrich Automobile Driven by Arthur Duray at the Vanderbilt Cup Race, Long Island, New York, 1906 / THF203486

Early American Racing: A Compulsion to Prove Superiority

The quest for automotive superiority began on the track. Innovation proved to be king—it is the fuel that built reputations, generated interest and investment, and paved the way to newfound glory.

Near the end of the 19th century, the infant auto industry was bursting at the seams with ideas, experiments, and innovations. The automobile was new and primarily a novelty—as soon as there were two cars on the road, their builders and drivers were compelled to race each other. Being competitive: It’s just human nature. Which was the best car, the best driver?

Automobile races soon became a proving ground, where carmakers could showcase their design and engineering prowess. Winning built reputations, generated interest and attracted investment.

The “Dawn of Racing” section of our new exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America, immerses you in an exploration of the early days of racing, using period settings, images, and authentic artifacts. It features two of America’s most significant early race cars.

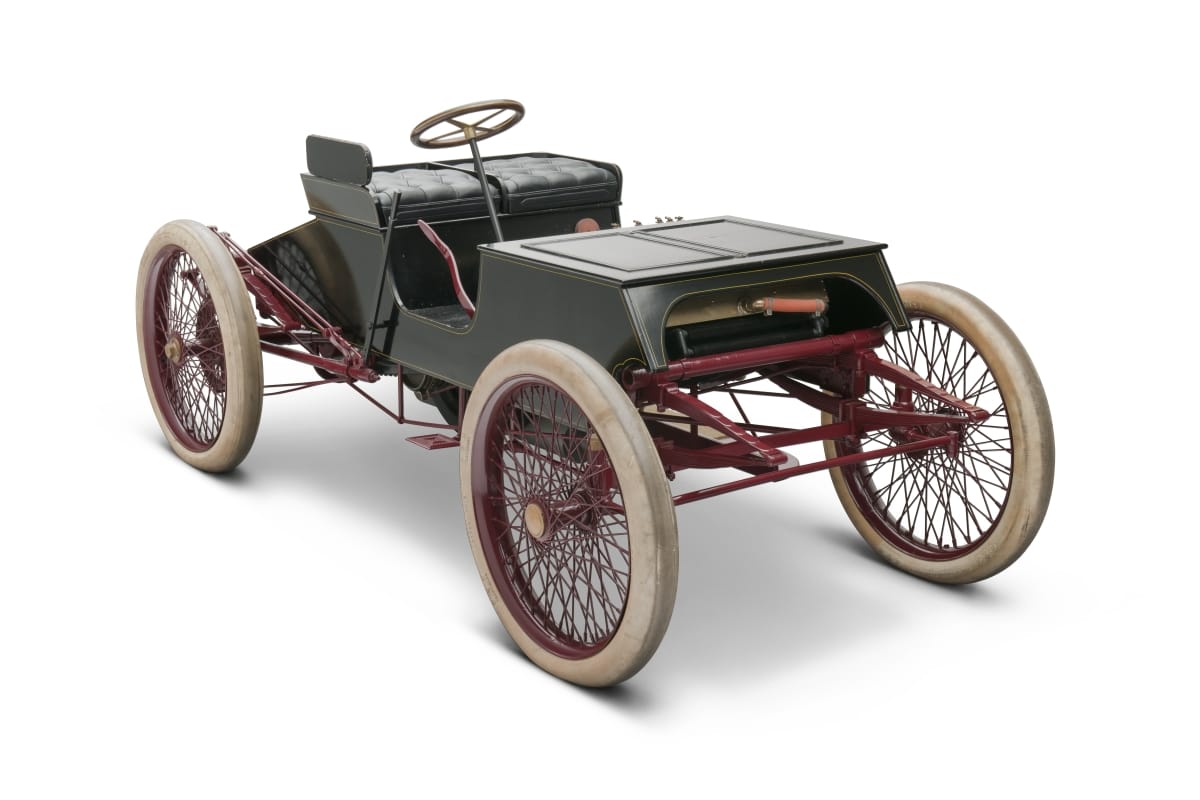

1901 Ford "Sweepstakes" Race Car

THF90167

Henry Ford only ever drove one race, on October 10, 1901, and that was in the car they called “Sweepstakes.” He certainly was the underdog, but against all odds he won. In Driven to Win, you will discover the innovations that Ford developed for “Sweepstakes” that helped him achieve that remarkable victory. It gave a powerful boost to his reputation, brought in financial backing that helped launch Ford Motor Company, and a few years later, Ford Motor Company put America—and much of the world—on wheels with the Model T.

1906 Locomobile "Old 16" Race Car

THF90188

Driving “Old 16” in the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup race, George Robertson scored the first victory by an American car in a major international auto race in the United States. At that time, the Vanderbilt Cup race was world-famous and highly prestigious, and “Old 16” became known as “the greatest American racing car.” In Driven to Win, you will learn about and see firsthand the expertise, craftsmanship and attention to detail that made this car a winner.

Additional Artifacts

THF154549

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts related to early racing in Driven to Win.

- Drop Box Used during the 1904 Vanderbilt Cup Race

- Automobile Racing Goggles, Used by Joe Tracy, circa 1905

- Early Automobile Racing Gloves, circa 1905, Owned by Joe Tracy

- Automobile Racing Face Mask, circa 1905, Owned by Joe Tracy

- Helmet Used by George Robertson in 1908 Vanderbilt Cup Race

- Paperweight Commemorating the 1908 Victory of the Locomobile Company at the Vanderbilt Cup Races

Dig Deeper

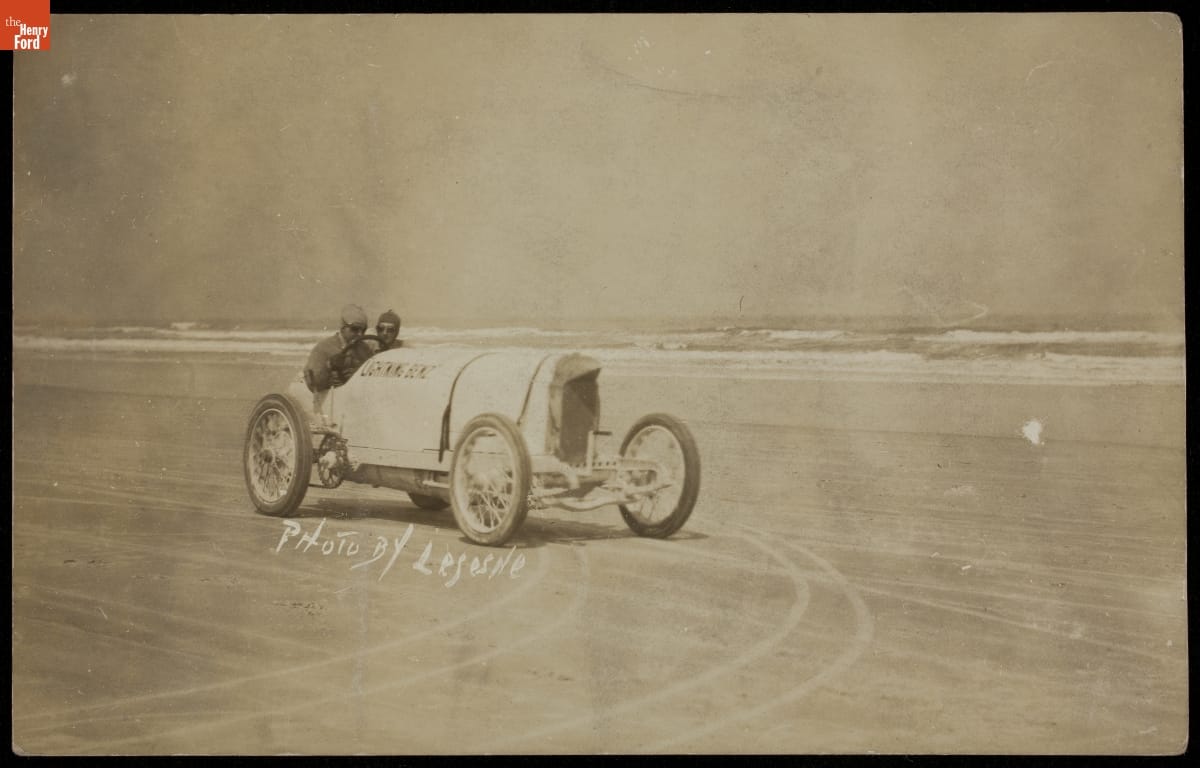

Barney Oldfield in "Lightning Benz," Daytona Beach, Florida, March 16, 1910 / THF228867

Learn more about early racing with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Discover the story of racer Barney Oldfield, one of America’s earliest celebrity sports figures.

- Watch our Sweepstakes replica run in Greenfield Village.

- Explore the world of board track racing.

- Learn how Ford Motor Company recognized Henry Ford’s 150th birthday with a custom-painted race car honoring Henry’s win in the Sweepstakes.

20th century, 1900s, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars

Let’s Tech Together

Illustration by Sylvia Pericles.

Welcome to the digital era. Now what?

In the fall of 2020, for the first time, an entire generation started school on a screen. As the new coronavirus abruptly cut many of us off from the world outside our homes, for those of us fortunate enough to enjoy digital communication tools, the Internet has become one of the most essential tools for surviving the COVID-19 pandemic. As sci-fi and scary as this may seem, there is also an opportunity here to transform—again—the Internet.

As COVID-19 continues to dramatically upend our lives, an ever-evolving digital world pushes us to rethink the purpose of the Internet and challenges us to re-create our digital and political lives as well as the Internet itself. The challenge is ensuring that all people will have the skills, knowledge and power to transform the Internet and shift its dependence on a commerce- and clickbait-driven economic model to become instead a universally guaranteed utility that serves people’s needs and allows creativity to flourish.

Societal Reflection

This challenge has been a long time coming. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Internet was on questionable ground. In early 2020, misinformation campaigns, privacy breaches, scams, and trolls proliferated online. When COVID-19 hit and the world was forced to shift the important tasks of daily life online, we saw (again) how digital inequalities persist—forcing poor and vulnerable communities to rely on low-speed connections and cheaper devices that can’t handle newer applications.

The Internet is a reflection of who we are as a society. We know that there are people who scam and bullies who perpetuate injustice. But there is also beauty, creativity, and brilliance. The more perspectives there are shaping this digital era, the more potential we have to tap the best parts of us and the world.

There is no silver bullet that will keep violence or small-mindedness at bay—online or off—but I know from 13 years of working on digital justice in Detroit that teaching technology is the first step toward decolonizing and democratizing it.

A City’s Story

Over the years, Detroit has faced many economic hardships, which has meant that digital access has too often taken a back seat. Bill Callahan, director of Connect Your Community 2.0, compiled data from the 2013 American Community Survey and found that Detroit ranked second for worst Internet connectivity in the United States.

Following that report, in 2017 the Quello Center of the Department of Media and Information at Michigan State University reported that 33% of Detroit households lacked an Internet connection, fixed or mobile. Yet the world had already moved online.

By 2011, many government agencies had transitioned away from physical spaces, making social services only accessible via the Internet. My colleagues and I at Allied Media Projects (a nonprofit that cultivates media strategies for a more just, collaborative world) understood that access to and control of media and technology would be necessary to ensure a more just future. As Detroiters, we needed to figure out how to create Internet access in a city that was flat broke and digitally redlined by commercial Internet providers. We also needed to address the fact that many Detroiters who had never before used digital systems had a steep learning curve ahead of them.

The question we asked our communities, and answered collectively, originated from and addressed Detroit’s unique reality: What can the role of media and technology be in restoring neighborhoods and creating new economies based on mutual aid?

Illustration by Sylvia Pericles.

To answer this question, the concept and practice of community technology—a method of teaching and learning technology with the goals of building relationships and restoring neighborhoods—emerged. If we want to harness the potential of the digital future ahead of us, we need to reshape our current relationships with the digital world. We need to understand how it works, demand our rights within it, and be aware of how digital tools shape our relationships with each other and with the larger world. Ultimately, the goal of community technology is to remake the landscape of technological development and shift the power of technology from companies to communities. The place where this begins is by rethinking our digital literacy and tech education models.

Community technology is inspired by the citizenship schools of the Civil Rights movement. Founded by Esau Jenkins and Septima Clark on Johns Island, South Carolina, in the 1950s, citizenship schools taught adults how to read so that they could pass voter-registration literacy tests. But under the innocuous cover of adult-literacy classes, the schools actually taught participatory democracy and civil rights, community leadership and organizing, practical politics, and strategies and tactics of resistance and struggle.

I saw a through line from the issues that encouraged citizenship schools to emerge in the 1950s to the struggles that Detroit faced in the early 2000s. In the 21st century, communities with high-speed Internet access and high levels of digital literacy enjoyed a competitive advantage. The denial of these resources to low-income and communities of color compounded the existing inequality and further undermined social and economic welfare in those neighborhoods.

Like the citizenship schools, community technology embraces popular education, a movement-building model that creates spaces for communities to come together in order to analyze problems, collectively imagine solutions, and build the skills and knowledge required to implement visions. This educational model structures lessons around the goal of immediately solving the problem at hand. In the citizenship schools, lessons were planned around the goal of reading the U.S. Constitution. Along the way, participants developed the profound technical and social skills needed to solve the problem.

In 2008, when I first started teaching elders in Detroit how to use and understand the Internet, it was always hard to know where to start. There were so many things to do online. The first question I asked was: “What do you wish you could do with the Internet?” Oftentimes, folks wanted to be able to view images of their grandchildren that had been sent to their email, or they would want to communicate with loved ones across the seas. It would be nearly impossible for me to teach a class that attended to all of those individual needs while keeping everyone engaged.

I wondered: If I taught problem-solving rather than teaching technology, could I support the same elder who couldn’t view a digital photo of their grandchild to build and install Wi-Fi antennas and run an Internet service provider (ISP) in their neighborhood?

As impossible as that may sound, it worked. In 20 weeks, I saw former Luddites work with their neighbors to build wireless networks. This curriculum went on to shape the Equitable Internet Initiative, which has trained over 350 Digital Stewards throughout Detroit, New York, and Tennessee.

Illustration by Sylvia Pericles.

Digital Liberation

Over the eight years I ran the Digital Stewards Program, what I realized is that relevance can engage someone to learn, but curiosity is what cultivates the kind of lifelong learning that leads to liberation.

Citizenship schools remind me that liberation is not a product of having learned a skill but rather the continued ability to participate in and shape the world to meet your and your communities’ needs. Becoming a lifelong learner of technology—and aspiring constantly to use it for liberatory ends—is essential because technology is constantly changing.

Every software program I ever learned in college is now obsolete. To meaningfully participate in the digital era, we need to be able to adapt technology to meet our needs rather than change ourselves to adapt to new technologies.

In order to cultivate the agency and self-determination necessary to rescue this digital era from corporations and trolls, we will need to change how we as a society pass on knowledge and how—and for whom—we cultivate leadership and innovation. Too often, technological knowledge is presented as a pathway for individual advancement through participation in a digital economy that further consolidates power and wealth for corporations. During this time of physical isolation, how do we change the experience of being forced into endless video meetings and classrooms into something more like inhabiting and co-creating a digital commons? Can we create environments that allow people to engage with technology from a community context rather than as distanced individuals stuck staring at our screens?

The Internet’s culture is currently being shaped by corporations. Social media platforms, ISPs, and algorithms control our movements through almost all online space. Can we remake the Internet into a community that we can all inhabit, and move away from the metaphor of the Internet as an information superhighway? Perhaps we can begin to build the equivalent of sidewalks, public parks, and bike lanes.

As a generation faces an unprecedented year of school online, we would be wise to realize that this is an opportunity for all of us to learn together and become both more critical of how we engage technology and more aware of what we see is lacking. How do we want to form a community online, navigating, creating, and adapting online spaces for our collective survival?

Perhaps, unwanted though it is, the global pandemic can inspire us to finally create a digital world that is befitting of our time and presence there—and can inspire the justice, equality, and hope that our IRL world so badly needs right now.

This post was adapted from an article by Diana J. Nucera that originally appeared in the January–May 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine. Nucera, aka Mother Cyborg, is an artist, educator, and community organizer who explores innovative technology with communities most impacted by digital inequalities. Post edited by Puck Lo; illustrations by Sylvia Pericles.

Civil Rights, education, COVID 19 impact, Michigan, Detroit, women's history, African American history, technology, by Diana J. Nucera, The Henry Ford Magazine

THF Conversations: Autonomous Vehicles - Solving Problems & Driving Changes

In honor of National Engineers Week at The Henry Ford, our Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson led a panel (including Michigan Department of Transportation’s Michele R. Mueller, Kettering University’s Kip Darcy, and Arrow Electronics’ Grace Doepker) on the topic of autonomous vehicles. The panel wasn’t able to answer all of the questions asked, so we’ve collected our inquiries for the experts to weigh in on.

If you missed the panel, you can watch the presentation here.

Is the Comuta-Car a copy of The Dale?

Matt: The Dale is a story unto itself. That car (like the company behind it) was considered a fraud, while the Comuta-Car was a much more successful effort to manufacture and market vehicles. The Dale was a three-wheeled car powered by a two-cylinder internal-combustion engine. The Comuta-Car had four wheels and a DC electric motor. The Dale was also considerably larger, measuring 190 inches long to the Comuta-Car's 95 inches. That said, both cars were aimed at economy-minded customers looking for fuel efficiency.

Is there a danger to the vehicle being hacked?

Michele: There is a lot of work around security from all aspects (vehicle, infrastructure, supplier hardware, software, etc.) that put multiple layers of security in place to prevent that.

Kip: System security is a big deal - ensuring vehicle platforms are using the most sophisticated security is vital to building trust for owners and operators. Over-the-air updates is an important component to ensure the vehicle platform has the latest antivirus/security defenses. Like cell phones, the platform always needs to be secure.

What types of programs/coding is available to protect the confidentiality of the car to only be assigned to the driver?

Michele: The industry has developed and continues to develop things such as personal recognition items (facial features, fingerprint, eye scan, etc.) that would allow this type of driver confidentiality. It has also brought to light concern over law enforcement and emergency responder access if needed in cases of having to impound a vehicle, if the vehicle is in a crash etc. MDOT has worked very diligently with Michigan State Police specifically to meet with industry professionals and talk through these challenges from that perspective and has aided the industry in their development of the technology. MDOT also works with other entities to provide training opportunities to Emergency responders for how to handle these types of vehicles as well as electric vehicles as they become more common on the infrastructure.

Kip: Quite likely that users and owners will give up a fair amount of confidentiality w/technology providers/OEMS when using fully connected vehicles. Like web browsing and mobile phone usage, it will be used to personalize the experience. Flip side - multiple users of a vehicle would have user accounts/profiles like current smart key/fob profiles on vehicles. If someone uses your fob, they may have access to your profile and user data.

How do these cars account for winter driving in states like Michigan?

Michele: A lot of testing goes on with these vehicles in all weather conditions and many of the auto companies and Tier I suppliers have facilities in northern and Upper Peninsula of Michigan to do testing such as this in those conditions. They are run through many weather scenarios rigorously and this is a good use case for why we set up our pilot and deployments in this space as sustainable environments so that regardless of when the weather happens the environment is there to test with.

Kip: As Michele points out, Michigan is an amazing test environment: the combination of extreme weather and infrastructure challenges make for great testing to compliment all of the work done in California, Arizona, and Nevada.

How do you overcome the liability issue? If an individual is in a crash due to driver’s error, it’s their fault. If an individual is in a crash in an autonomous car, is the manufacture at fault?

Michele: This is a very hot topic with a lot of lawyers, legal teams, insurance entities, etc., all part of the conversation. That determination is not out yet and I believe we have a bit to go before it is resolved. I do know that the reduction of crashes is drastically reduced by taking the human error factor out which automatically leads to a reduction in injuries and fatalities.

Kip: I see the convergence of two issues; driver liability and product liability. Currently need a licensed driver in a vehicle - fault pinned to the driver (however, MI is no-fault) Malfunctioning systems would be a product liability issue - such as a possible design or manufacturing defect. In a future w/L4/L5 fully automated vehicles w/o a licensed driver, the insurance regulations will need to change. NAIC National Auto Insurance Commissioners has resources on the topic.

When do you think autonomous vehicles will become widely used in our everyday life?

Michele: I personally believe that a fully Level 5 automated vehicle being widely used with saturation is 15-20 years out. We have automated vehicles today with different feature sets and they are showing benefits. There will be a transition period and a mixed use for a quite a while yet.

Kip: Based on adoption studies done before the pandemic, I would concur: 2045 for 50% adoption rate for L4/L5. Important to remember the average fleet age in the US: 11- to 12-years old; a lot of old cars on the road.

You mentioned how highways impacted cities and Black communities. You could flip that question and ask about how autonomous vehicles will impact rural communities, especially in areas where cities are few and far between and infrastructure not as important. Is there an incentive to go automated in independent, rural America?

Michele: The speculation is that you will see some sort of incentivization at some point to adapt the technology in your vehicle whether new or after market. This may come as the technology and infrastructure are more advanced and refined for implementation, nobody knows for sure what that will look like however, it is very feasible. MDOT has done testing with industry partners in rural areas and to be honest there are some differences but not many, we currently do a lot of testing and deployments in the denser areas just due to the location of the industry partners doing development and testing, the closer they are to those platforms the more testing, tweaks, retesting that can be done for a lower cost. In the decision-making process for infrastructure standards and specifications we are looking at the entire State of Michigan for setting those and as upgrades and projects are done all areas are putting in the infrastructure to be ready for the technology as the needs and demand spreads.

Additional Resources: Please check out the following links to learn more.

Employment with the State of Michigan

State of Michigan Job Alerts

Application Process

Recruitment Bookmark

First-Time Applicants: How To

Working at MDOT

Internships at MDOT

MDOT: Planning for the Future

MDOT Transportation Technicians

MDOT Transportation Engineers

Engineer Development Program

| MDOT - Michigan Department of Transportation Michigan Department of Transportation – Michigan Department of Transportation is responsible for planning, designing, and operating streets, highways, bridges, transit systems, airports, railroads and ports. Find out more about lane closures, roads, construction, aeronautics, highways, road work and travel in Michigan. MDOT: 2021 Engineering Week Webpage |

| Arrow Electronics: Five Years Out |

| Kettering University: |

Capturing a Moment: How We Created a Display for Henry Ford’s “Sweepstakes”

In his first race ever, Henry Ford beat Alexander Winton in the Sweepstakes Race. / THF94819

On October 10, 1901, Henry Ford made history by overcoming the favored Alexander Winton in his first-ever automobile race. Backed by a willingness to take risks and an innovative engine design, Henry earned the reputation and financial backing through this one event to start Henry Ford Company, his second car-making venture.

His success that day is a natural introduction display for our newest permanent exhibition, Driven to Win: Racing in America, presented by General Motors. Driven to Win celebrates over 100 years of automotive racing achievements and the people behind the passion for going fast.

Photos of the 1901 race provide a view of the environment that written accounts don’t. / THF123903

In creating an exhibition, we start with many experience goals. In this case, one exhibition goal is to take our guests behind-the-scenes and trackside. As you experience Driven to Win, you’ll find many of the vehicles displayed on scenic surfaces and in front of murals that represent the places the cars raced. Henry Ford’s Sweepstakes Race took place on a horse racing track in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. Through reference photos and discussions with our exhibit fabrication partner, kubik maltbie, artisans created a surface that captures the loose dirt quality of a horse racing track. If you look closely, you’ll see hoof prints alongside tire tracks, which capture the unique location of this race.

kubik maltbie’s artists created a variety of samples to find the most accurate dirt display surface that’s also suitable for use in a museum setting.

Look closely and you can see evidence of horses having raced on the same track.

The next component in bringing this race to life needed to illustrate what the day was like. It also needed to convey the most exciting part—when Henry Ford overtook his competition. Working with a local artist, Glenn Barr, we created a background mural depicting Henry’s rival being left in the dust. To do this, we returned to available reference photos showing the track, grandstand, and Henry’s rival, Alexander Winton, who was the country’s most well-known racer at this time.

Sketches and small-scale paintings allowed Glenn Barr and the design team to discuss components of the mural before the final painting was created.

Glenn created a series of early sketches to make sure we had all the important elements. We then took those sketches and added them to our 3D model of the exhibition. This allowed us to pre-visualize the entire display from all angles, and verify we had the correct perspective in the mural. Color plays a big part in creating this scene with a certain mood. The goal was a color palette that felt like 100+ years ago, but also like we were watching the race. Glenn created a series of color samples that allowed us to find the right combinations.

Programs like Sketchup allow us to easily create exhibit spaces in three-dimensions so that we can study sightlines and relationships between exhibit elements.

While this photo was posed, likely to commemorate the race win, Henry Ford and Ed “Spider” Huff’s postures are confirmed from other photos, and this one provides clearer details. / THF116246

The last element in creating our day-of-the-race display was perhaps the most important—Henry Ford and his ride-along mechanic, Ed “Spider” Huff, themselves. Again, reference photos are vital tools in seeing the past. In creating these mannequins we had three key elements to address: Henry and Spider’s likenesses, the clothing they wore, and the postures they’d have sitting in the vehicle. kubik maltbie’s artists were able to capture this moment. They started with clay sculptures of Henry and Spider’s faces.

Henry Ford and Ed “Spider” Huff’s likenesses were captured in life-sized clay sculptures that would later be used to create molds for the finished mannequins.

As these mannequins needed to sit directly in the vehicle, a museum artifact, much of the final sizing, positioning, and decisions on how they interfaced with the car was done away from the actual vehicle. kubik maltbie’s sculptor came to the museum for several days and built a wood frame system around the Sweepstakes. This accurately captured important dimensions and connection points. An exact replica of the steering wheel became a template that sculptors could use in their studio to finalize hand positioning.

If you’ve visited Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford, you’ll have seen that period clothing is one of our specialties. Every spring we distribute over 1,000 sets of handmade attire authentic to many different time periods. With insight from our curators, our Clothing Studio provided period-accurate clothing, from shoes to hats, for Henry and Spider.

Henry Ford and Ed “Spider” Huff arrive at the museum.

Museum conservators and the installation team place Ed “Spider” Huff, Henry’s ride-along mechanic, on the Sweepstakes’ running board.

Together, all these elements allow us to take you on a trip back in time. I invite you to visit the museum and see this monumental moment in racing history, stand trackside, and imagine what it must have been like. You can even hear our faithful replica of the “Sweepstakes” running. It sounds nothing like today’s track-ready racing machines.

Wing Fong is Experience Design Project Manager at The Henry Ford.

cars, making, art, design, race car drivers, race cars, collections care, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Wing Fong, racing, Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win

Membership Spotlight: The Meerkov/Maddipati Family

Meera, Sri, Maya, and Sonia. Photo by EE Berger.

Four-year The Henry Ford members Meera Meerkov and Sri Maddipati and their young daughters appreciate the hands-on nature and historical authenticity of trains, tractors and centuries-old buildings brought to life.

When Meera Meerkov and Sri Maddipati and their eldest daughter Maya moved back to metro Detroit in 2015, a good friend brought them to Greenfield Village. The bond was immediate. For little Maya, it was the beginning of a long-term adoration of a train ride and a carousel—one she later passed on to her younger sister Sonia. For the adults, it was an initial astonishment and then an enduring appreciation for attractions built around actual historical structures within Greenfield Village. Amazement over a collection of presidential vehicles in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, added Meera, has also bloomed. And the girls can’t ever miss a bit of playtime at the water tower, in the boiler tunnel or on the 1931 Model AA truck in the village’s historically themed playscape.

Their must-dos:

- Spending time near the Allegheny Steam Locomotive and New Holland TR70 Axial Flow Combine in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

- Stopping by the Glass Shop in Greenfield Village.

- Going to “school” in the one-room schoolhouses.

- Finding and riding the zebra on the Herschell-Spillman Carousel.

- Stopping for a creamy frozen custard at the Village stand.

Their favorite member perk:

We love being able to stop in for a quick visit and keep up with new exhibits. There is always so much to do and see in both Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.

What’s your spark? Let us know what inspires you on your next visit and what takes you forward from your membership. Email us at membership@thehenryford.org. Take it forward as a member—enjoy benefits like free parking, discounts on events and tours, exclusive member previews, and more.

This post was adapted from a page in the January-June 2021 issue of THF Magazine.

Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, The Henry Ford Magazine

"How Are We Going to Do That?": Driven to Win Vehicle Installation

The vehicles in Driven to Win: Racing in America are displayed in a much more dynamic and contextualized way than we’ve attempted in previous car exhibits. Cars that have been displayed for decades on the floor are now elevated and (in some cases) tilted, to recreate how you would see them while racing. The payoff in guest experience will be significant, but these varied vehicle positions required extensive conversations, engineering, and problem solving between our internal teams and kubik maltbie, our fabrication partner. This post highlights four of the most notable car installations.

1965 Goldenrod Land Speed Race Car

The 1965 Goldenrod Land Speed Race Car is now displayed on a salt-flat mimicking platform just three inches high. For most vehicles, three-five people would use a couple of short ramps and push or tug the vehicle up, all in less than an hour. But for a vehicle that is 32 feet long and sits less than 2 inches off the ground, another solution had to be found—since no ramp long enough to prevent the vehicle from bottoming-out would fit in the space provided.

As a land speed racer, Goldenrod achieved its fame in miles per hour, not in turning ability. To get the vehicle anywhere besides straight back and forward, custom gantries (mobile crane-like structures) are needed to lift it off the ground so that it can turn on the gantries’ wheels, not its own. The gantries provided inspiration to solve the issue of how to raise the Goldenrod high enough to make it onto the exhibit platform.

Conservation and Exhibits staff attach gantries to Goldenrod to enable movement.

Since Goldenrod can be raised several feet once it is attached to the gantries, we were able to get the vehicle as close as possible to the platform, align it properly, then detach the back gantry and lift it onto the exhibit platform. This ability to lift the gantries independently was critical to our success.

A forklift is attached to the rear gantry and used to tow Goldenrod into position over railroad tracks covered with steel plates.

Sections of plywood and Masonite were laid to the same height as the exhibit platform. At this point, the rear gantry was rolled forward onto this temporary surface, aligned once again with its hubs.

Plywood and Masonite were used to transition the gantries to the correct height to roll Goldenrod into the exhibit.

The back gantry was then reattached to Goldenrod, allowing three-quarters of the vehicle to roll onto the exhibit platform.

Halfway there!

The same process was followed with the front gantry, and the vehicle was then adjusted into place. Steel plates and Masonite allowed the gantries to roll on the platform without damage to the faux salt surface.

Exhibits and Conservation staff celebrate Goldenrod's final placement.

Installation into the Winner’s Circle

The Winner’s Circle is the premier location in Driven to Win, showcasing some of the most renowned winning vehicles in all of motorsports, and deserves to be elevated in display. During the planning process, we first returned to our typical method of placing cars on a platform: ramps. But in this case, as with Goldenrod, not every car would have made it up a ramp with the pitch necessary, due to other exhibit items in the way. We went back and forth from idea to idea for some time.

What we finally settled on was what we’ve deemed “rolling jackstands,” or dollies. kubik maltbie took our measurements of these vehicles and fabricated these dollies out of Unistrut and casters. Each was custom-fitted and modified on site to conform to the load when the car was rested on top of them. Once on these dollies, the cars are very easy to move. They slide into the Winner’s Circle and the fronts of their platforms slide into place in a theatrical, modular way.

Custom dollies, or "rolling jackstands" allow vehicles to be elevated for display and rolled into the exhibit at the appropriate height.

By this point, half of the problem was solved. The other half was how to get these cars onto their jackstands. For this, we employed three techniques. First, we were able to sling some of the cars and lift them using a huge gantry on the back half and a forklift on the front. We used this method on the 1958 Moore/Unser Pikes Peak Hill Climb Racing Car. It was a slow but effective means of raising the vehicle just high enough that the jackstands could be slid underneath.

1958 Moore/Unser Pikes Peak Hill Climb racing car being lifted using a gantry and forklift.

One vehicle, the 1956 Chrysler 300C Stock Car, had the ability to be lifted from below using floor jacks.

1956 Chrysler 300B Stock Car rolling into its display position.

Finally, some vehicles, including the Indy cars and the 1967 Mark IV Race Car, posed serious issues since they had nowhere that we could use a floor jack, and did not have bodies that could be slung with straps.

In this case, we benefited from having an expert volunteer on our team. Mose Nowland was one of the original engineers who built the Mark IV in the 1960s. A fantastic problem-solver, he designed a custom metal apparatus, which we call a “sling,” that would allow a telescopic handler to lift it. We had Mose’s design fabricated at a metal shop. Since the sling spread out the attachment points, straps could then be placed and balanced at appropriate points on the vehicles. It really helps to know one of the car’s original engineers when you need to figure out rigging stunts like this.

Mark IV being lifted onto its dollies with the help of a custom sling and a telescopic handler.

But what if we wanted some of these elevated cars to be on an angle, like they would be while actually racing? First, we needed to have that approved by a conservator, to make sure the car can physically handle years or decades in that position. Then, the same lifting methods described above were used, but the rolling jackstand dollies were made with legs of various heights. When the cars were set down upon them, they were strapped in with custom mounts so that they could sit comfortably for much time to come.

Ultimately, the goal of any artifact mount is to safely hold the object but not call attention to itself. We hope that we’ve succeeded in keeping the emphasis on an exciting presentation of these vehicles that we are looking forward to showing our guests.

The 1958 Moore/Unser racing up our scenic recreation of Pikes Peak in Driven to Win.

The Mark IV on permanent display in Driven to Win.

Kate Morland is Exhibits Manager at The Henry Ford.

race cars, Mark IV, racing, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, collections care, cars, by Kate Morland, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Improving Accessibility and Inclusion

Adult changing table in one of our two new accessible companion-care restrooms.

As for so many others, the year 2020 was not easy for The Henry Ford. The pandemic brought many challenges that we had to face as an institution. Despite those challenges, we remained committed to reaching strategic goals that we had set to improve accessibility and inclusion for all of our guests. Through teamwork and determination, we were able to stay on track toward this commitment.

We are excited to share that we received a three-year grant from the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to support sensory programming initiatives. With this grant, we will be able to expand our current programming and build on what we have learned with new programming for guests with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and sensory processing disorder (SPD). The grant will allow guests to have improved on-site experiences and access to our collections in all of our venues.

Another aspect provided by the grant is free general admission to families of those with ASD and SPD. Two of our special events, Sensory-Friendly Hallowe'en in Greenfield Village and Sensory-Friendly Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village, are included. In 2020, we hosted 875 guests for those very popular events.

In addition, we are excited to announce that, within the next year, we are planning to launch a new program for teens and young adults with ASD and SPD that will include activities aimed at social skill-building and networking.

The inclusion of all guests is one of the main pillars of our strategic plan. We believe that this is an important component that will help all guests feel welcome and comfortable on our campus. Because of this, we are expanding training for both current and new staff members. We are developing a module that will use information from the Autism Alliance of Michigan, as well as other organizations, to help our staff become more aware of those with disabilities. As an institution, we understand that it is our responsibility to become more aware of disabilities, as well as how we can modify our unique educational experiences for guests who may need additional support. It is important that guests of all ages, backgrounds and abilities have equal access to the collection and our campus.

Another example of how we are making a more comfortable experience for our guests with disabilities is with the installation of two new accessible companion care restrooms, located at both ends of the main promenade of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Our accessibility specialist, Caroline Braden, partnered with the Madison Center to help design these restrooms. The Madison Center has partnered with The Henry Ford for over 10 years through our Community Outreach Program. The project was supported in part by grants from the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs and the Ford Foundation.

Toilet in one of our new accessible companion-care restrooms.

The work done on the companion care restrooms goes above and beyond compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The restrooms are barrier-free and include power-operated doors, extra space, and a power-adjustable adult changing table. These tables will be able to accommodate guests with physical and cognitive disabilities. As an institution, we are very proud of this construction, and we are very grateful to those who worked so hard on this essential project.

Caroline Heise is Annual Fund Specialist at The Henry Ford.

by Caroline Heise, The Henry Ford Effect, IMLS grant, Henry Ford Museum, design, accessibility, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Wendell Scott: Breaking NASCAR’s Color Barrier

Wendell Scott, NASCAR’s first full-time Black driver, used this 1966 Ford Galaxie, currently on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, during the 1967–68 seasons. (Vehicle on loan courtesy of Hajek Motorsports. Photo credit: Wes Duenkel Motorsports Photography.)

Stock car racing is a difficult business. Budgets and schedules are tight, travel is grueling, and competition is intense. Imagine facing all of these obstacles together with the insidious challenge of racism. Wendell Scott, the first African American driver to compete full-time in NASCAR’s top-level Cup Series, overcame all of this and more in his winning and inspiring career.

Portrait of Wendell Scott from the February 1968 Daytona 500 program. / THF146968

Born in Danville, Virginia, in 1921, Scott served in the motor pool during World War II, developing skills as a mechanic that would serve him well throughout his motorsport career. He started racing in 1947, quickly earning wins on local stock car tracks. Intrigued by the new National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR), formed in 1948, Scott traveled to several NASCAR-sanctioned events intent on competing. But each time, officials turned him away, stating that Black drivers weren’t allowed.

Undaunted, Scott continued to sharpen his skills in other stock car series. He endured slurs and taunts from crowds, and harassment on and off the track from other drivers, but he persevered. Of necessity, Scott was his own driver, mechanic, and team owner. Gradually, some white drivers came to respect Scott’s abilities and dedication to the sport. Through persistence and endurance, Scott obtained a NASCAR competition license and made his Cup Series debut in 1961. He started in 23 races and earned five top-five finishes in his inaugural season. On December 1, 1963, with his victory in a 100-mile race at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida, Wendell Scott became the first Black driver to win a Cup Series event.

Wendell Scott on the track—in a 1965 Ford Galaxie—in 1966. / THF146962

But that win did not come easy—even after the checkered flag fell. The track was rough, many drivers made multiple pit stops, and no one was sure just how many laps some cars had completed, or who truly had the lead. Initially, driver Buck Baker was credited with the victory. Baker went to Victory Lane, posed for photos, addressed the press, and headed home. Wendell Scott was certain that he had won and, as was his right, immediately requested a formal review. After two hours, officials determined that Scott was, in fact, the true winner. Scott received the $1,000 cash prize, but by that time the ceremony, the trophy, and the press were long gone. (The Jacksonville Stock Car Racing Hall of Fame presented Scott’s widow and children with a replica of the missing trophy in 2010—nearly 50 years later.)

Throughout his career, Scott never had the support of a major sponsor. He stretched his limited dollars by using second-hand cars and equipment. During the 1967–68 seasons, he ran a 1966 Ford Galaxie he acquired from the Holman-Moody racing team. That Galaxie was one of 18 delivered from Ford Motor Company to Holman-Moody for the 1965–66 NASCAR seasons. During the 1966 season, Cale Yarborough piloted the Galaxie under #27. Scott campaigned the car under his own #34, notably driving it at the 1968 Daytona 500 where he finished seventeenth.

Cale Yarborough at the wheel of the 1966 Ford Galaxie at that year’s Daytona 500. / THF146964

Wendell Scott’s Cup Series career spanned 13 years. He made 495 starts and earned 147 top-ten finishes. He might have raced longer if not for a serious crash at Talladega Superspeedway in 1973. Scott’s injuries put him in the hospital for several weeks and persuaded him to retire from competitive driving. Scott passed away from cancer in 1990, but not before seeing his life story inspire the 1977 Richard Pryor film Greased Lightning.

Scott’s 1966 Ford Galaxie is on loan to The Henry Ford courtesy of Hajek Motorsports, which previously loaned the car to the NASCAR Hall of Fame in Charlotte, North Carolina. We are proud to exhibit it, and to share the story of a pioneering driver who overcame almost every conceivable challenge in his hall-of-fame career.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

race car drivers, race cars, 1960s, 20th century, racing, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars, by Matt Anderson, African American history

Food Soldiers: Nutrition and Race Activism

A pattern of Black activism exists, a pattern evident in the work of individuals who dedicate themselves to improving the health and wellbeing of others. These individuals may best be described as “food soldiers.” They arm themselves with evidence from agricultural and domestic science. They build their defenses one market garden at a time. They ally with grassroots activists, philanthropists, and policy makers who support their cause. Past action informs them, and they in turn inspire others to use their knowledge to build a better nation.

June Sears, Rosemary Dishman, and Dorothy Ford Discussing Women's Nutrition, May 1970. / THF620081

Food Sources

Food is one of life’s necessities (along with clothing and shelter). Centuries of legal precedent confirmed the need for employers to provide a food allowance (a ration), as well as clothing and shelter, to “bound” employees. For example, a master craftsman had to provide life’s necessities to an indentured servant, contracted to work for him for seven years, or a landowner was legally required (though adherence and enforcement varied) to provide food, clothing, and shelter to an enslaved person, bound to labor for life. This legal obligation changed after the Civil War with the coming of freedom.

Landowner R.J. Hart scratched out the clause in a contract that obligated him to furnish “healthy and substantial rations” to a freedman in 1868. Hart instead furnished laborer Henry Mathew housing (“quarters”) and fuel, a mule, and 35 acres of land. In exchange, Mr. Mathew agreed to cultivate the acreage, to fix fencing, and to accept a one-third share of the crop after harvest. The contract did not specify what Mr. Mathew could or should grow, but cotton dominated agriculture in the part of Georgia where he lived and farmed after the Civil War.

Cotton is King, Plantation Scene, Georgia, 1895 / THF278900

This new agricultural labor system—sharecropping—took hold across the cotton South. As the number of people laboring for a share of the crops increased, those laborers’ access to healthy foods decreased. Instead of gardening or raising livestock, sharecroppers had to concentrate on cash-crop production—either cotton or more localized specialty crops such as sugar cane, rice, or tobacco. Anything they grew for themselves on their landlord’s property went first to the landlord.

Postcard, "Weighing Cotton in the South," 1924 / THF8577

With no incentive or opportunity to garden, sharecroppers had few options but to buy groceries on credit from local merchants, who often were also the landowners. A failed crop left sharecroppers even more indebted, impoverished, and malnourished. This had lasting consequences for all, but race discrimination further disadvantaged Black Southerners, as sociologist Stewart Tolnay documented in The Bottom Rung: African American Family Life on Southern Farms (1999).

As food insecurity increased across the South, educators added agricultural and domestic science to classroom instruction. Many schools, especially land-grant colleges, gained distinction because of this practical instruction. Racism, however, limited Black students’ access to education. Administrators secured private funding to deliver similar content to Black students at private institutes and at a growing number of public teacher-training schools across the South.

Microscope Used by George Washington Carver, circa 1900, when he taught agricultural science at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, as it was known at the time. / THF163071

Lessons in domestic science aligned with agricultural science most obviously in courses in market gardening. A pamphlet, Everyday Life at Hampton Institute, published around 1907, featured students cultivating, harvesting, and marketing fresh fruits and vegetables. Female students also processed and preserved these foods in domestic science classes. Graduates of these programs stood at the ready to share nutrition lessons. Many, however, criticized this training as doing too little to challenge inequity.

Sixth Street Market, Richmond, Va., 1908-1909 / THF278870

Undaunted food soldiers remained committed to arguing for the value of raising healthy foods to build healthy communities. They justified their advice by tying their self-help messages to other goals. Nature study, a popular approach to environmental education early in the twentieth century, became a platform on which agricultural scientist George Washington Carver built his advocacy for gardening, as Nature Study and Children’s Gardens (1910) indicates.

Nature Study and Children's Gardens, circa 1910, page 6 / THF213304

Opportunity increased as the canning industry offered new opportunities for farm families to produce perishable fruits and vegetables for shipment to processors, as well as for home use. Black experts in agriculture and domestic science encouraged Black landowning farm families that could afford the canning equipment to embrace this opportunity. These families also had some local influence and could encourage broader community investment in new market opportunities, including construction of community canning centers and purchase of canning equipment to use in them.

The Canning and Preserving of Fruits and Vegetables in the Home, 1912 / THF288039

Nutritionists who worked with Black land-owning farm families reached only about 20 percent of the total population of Black farmers in the South. Meeting the needs of the remaining 80 percent required work with churches, clubs, and other organizations. National Health Week, a program of the National Negro Business League, began in 1915 to improve health and sanitation. This nation-wide effort put the spotlight on need and increased opportunities for Black professionals to coordinate public aid that benefitted families and communities.

Nutritionists advocated for maternal health. This studio portrait features a woman with two children, circa 1920, all apparently in good health. / THF304686

New employment opportunities for nutritionists became available during the mid-1910s. Each Southern state created a “Negro” Division within its Agricultural Extension Service, a cooperative venture between the national government’s U.S. Department of Agriculture and each state’s public land-grant institution. Many hired Black women trained at historically Black colleges across the South. They then went on the road as home demonstration agents, sharing the latest information on nutrition and food preservation.

Woman driving Chevrolet touring car, circa 1930. Note that the driver of this car is unidentified, but she represents the independence that professional Black women needed to do their jobs, which required travel to clients and work-related meetings. / THF91594

Class identity affected tactics. Black nutritionists were members of the Black middle class. They shared their wellness messages with other professional women through “Colored” women’s club meetings, teacher conferences, and farmer institutes.

Home economics teachers and home demonstration agents worked as public servants. Some supervisors advised them to avoid partisanship and activist organizations, which could prove difficult. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), most noted for attacking inequity through legal challenges, first hosted Baby Contests in 1924. These contests had double meanings. For nutritionists, healthy babies illustrated their wellness message. Yet, “Better Baby” contests had a longer history as tools used by eugenicists to illustrate their race theory of white supremacy. The most impoverished and malnourished often benefitted least from these middle-class pursuits.

Button, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 1948 / THF1605

Nutrition

Nutrition became increasingly important as science linked vitamins and minerals to good health. While many knew that poor diets could stunt growth rates and negatively affect reproductive health, during the 1920s and 1930s medical science confirmed vitamins and minerals as cures for some diseases that affected children and adults living in poverty. This launched a virtual revolution in food processing as manufacturers began adding iodine to salt to prevent goiters, adding Vitamin D to milk to prevent rickets, and adding Vitamin B3 to flour, breads, and cereals to prevent pellagra.

"Blue Boy Sparkle" Milk Bottle, 1934-1955 / THF169283

It was immediately obvious that these cures could help all Americans. The American Medical Association’s Committee on Foods called for fortifying milk, flour, and bread. The National Research Council first issued its “Recommended Dietary Allowances” in 1941. Information sharing increased during World War II as new wartime agencies reiterated the benefits of enriched foods.

World War II Poster, "Enrichment is Increasing; Cereals in the Nutrition Program," 1942 / THF81900

Black nutritionists played a significant role in this work for many reasons. They understood that enriched foods could address the needs of Black Americans struggling with health concerns. They knew that poverty and unequal access to information could slow adoption among residents in impoverished rural Black communities. Black women trained in domestic science or home economics also understood how racism affected health care by reducing opportunities for professional training and by segregating care into underfunded and underequipped doctor’s offices, clinics, and hospitals. That segregated system further contributed to ill health by adding to the stress level of individuals living in an unequal system.

Mobilization during World War II offered additional opportunities for Black nutritionists. The program for the 1942 Southern Negro Youth Conference at Tuskegee Institute addressed “concrete problems which the war has thrust in the forefront of American life.” Of the conference’s four organizing principles, two spoke directly to the aims of food soldiers: "How can Negro youth on the farms contribute more to the nation’s war production effort?” and “How can we strengthen the foundations of democracy by improving the status of Negro youth in the fields of: health and housing; education and recreation; race relations; citizenship?”

Program for the 5th All -Southern Negro Youth Conference, "Negro Youth Fighting for America," 1942 / THF99161

Extending the Reach

Food soldiers knew that the poorest suffered the most from malnutrition, but times of need tended to result in the most proactive legislation. For example, high unemployment during the Great Depression led to increased public aid. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) built new schools with cafeterias and employed dieticians to establish school lunch programs. Impoverished families also had access to food stamps to offset high food prices for the first time in 1939 through a New Deal program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Elizabeth Brogdon, Dietitian at George Washington Carver School, Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1947 / THF135669

Elizabeth Speirs Brogdon (1915–2008) opened school lunchrooms under the auspices of the WPA in 19 Georgia counties for six years. She qualified for her position with a B.S. in home economics from Georgia State College for Women, the state’s teacher’s college, and graduate coursework in home economics at the University of Georgia (which did not officially admit women until after she was born).

While Mrs. Brogdon could complete advanced dietetics coursework in her home state, Black women in Georgia had few options. The Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth, designated as Georgia’s Black land-grant school at the time, did not admit women as campus residents until 1921, and did not offer four-year degrees until 1928. Black women seeking advanced degrees in Home Economics earned them at Northern universities.

Flemmie Pansy Kittrell (1904–1980), a native of North Carolina and graduate of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, became the first Black woman to hold a PhD in nutrition (1938) from Cornell University. Her dissertation, “A Study on Negro Infant Feeding Practices in a Selected Community of North Carolina,” indicated the contribution that research by Black women could have made, if recognized as valid and vital.

Increased knowledge of the role of nutrition in children’s health informed Congress’s approval of the National School Lunch Program in 1946. In addition to this proactive legislation, some schools, including the school in Richmond Hill, Georgia, where dietitian Elizabeth Brogdon worked, continued the tradition of children’s gardens to ensure a fresh vegetable supply.

Child in a School Vegetable Garden, Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1940 / THF288200

The pace of reform increased with the arrival of television. The new medium raised the conscience of the nation by broadcasting violent suppression of peaceful Civil Rights demonstrations. This coverage coincided with increased study of the debilitating effects of poverty in the United States. Michael Harrington’s book The Other America (1962) increased support for national action to address inequity, including public health. President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s “War on Poverty” became a catalyst for community action, action that Kenneth Bancroft Clark analyzed in A Relevant War Against Poverty (1969).

Michigan examples indicate how agricultural policy expanded public aid during the 1960s. President Johnson’s War on Poverty expanded public programs. This included a new Food Stamp Program in 1964, a recommitment to school lunch programs, and new nutrition education programs, all administered through the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Nutritionists, including June L. Sears, played a central role in implementing this work.

“June Sears, Rosemary Dishman, and Dorothy Ford Discussing Women's Nutrition,” May 1970. Rosemary Dishman served as a program aide and Dorothy Ford as supervising aide for Michigan’s Expanded Nutrition Program. / THF620081

Mrs. Sears earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Wayne State University in Detroit and taught home economics before becoming the “Family Living Agent” in the Cooperative Extension Service of Michigan State University (Michigan’s land-grant university). In that capacity, she, along with Rosemary Dishman and Dorothy Ford, worked with low-income families in two metropolitan Detroit counties (Wayne and Oakland), educating them about nutrition and meal planning. The USDA’s Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP), funded in 1969, sustained this work.

Public aid became a central component of U.S. farm bills by 1973. That year, the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act reaffirmed the deployment of excess agricultural production to meet consumer need. Additional legislation, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), funded in 1975, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), evolved to meet need.

And need was great.

Detroit Mayor Coleman Young explained in February 1975 that as many as 200,000 of his city’s 1.5 million citizens were undernourished. This extreme need existed despite efforts to address food insecurity, documented as an issue that mobilized protestors during the violent summer of 1967. Then, investigations by Detroit-based Focus: HOPE, a community advocacy organization, confirmed that food was more expensive for lower-income Detroiters than for some wealthier suburbanites, a condition now described as a “food desert.”

“Depression's Harsh Impact at the Focus: HOPE Food Prescription Center in Detroit” Photograph, March 1975 / THF620068

Focus: HOPE staff opened a “Food Prescription Center,” stocked with USDA commodities that included enriched farina wheat cereal, canned meats, and other supplements.

Focus: HOPE Button, 1999 / THF98376

Commodity packaging has changed, as has farm policy over the years, but nutrition remains foundational to human health and well-being, and private and public partnerships remain essential to meeting need. The work continues with organizations such as Diversify Dietetics, Inc., which exists “to increase the racial and ethnic diversity in the field of nutrition.”

Food & Freedom

While nutritionists worked with schools, cooperative demonstration programs, and public service organizations, another brigade of food soldiers linked farming to full citizenship.

Mississippi activist Fannie Lou Hamer built her freedom struggle around land ownership and family farming. She founded Freedom Farms Cooperative to provide land to displaced sharecroppers, where they could grow crops and livestock and build self-esteem.

Hamer’s story, and those of other Black farm advocates, draw attention to a farm movement linked to the freedom struggle. A rich and growing body of scholarship indicates how much there is to learn about this movement. Two books, Greta De Jong’s You Can’t Eat Freedom: Southerners and Social Justice after the Civil Rights Movement (2016) and Monica M. White’s Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement (2018), document the geographic range and approaches taken by food soldiers. White devotes a chapter to the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network as an example of Northern urban agriculture.

Brussel Sprout Stalks after Harvest, Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, October 30, 2010 / THF87927

Other farmers write their own story, as does Leah Penniman, recipient of the James Beard Leadership Prize in 2019. She outlines best practices for establishing and sustaining a Black farm cooperative in her book, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land (2018).

Another model takes the form of social entrepreneurship, as undertaken by Melvin Parson, The Henry Ford’s first Entrepreneur in Residence (2019), funded by the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship. You can hear Farmer Parson (as his friends call him) compare his entrance into market gardening to taking a seat at the table as a full member of society.

“Melvin Parson Gardening during the Entrepreneurship Interview” / THF295401

Farmer Parson founded We The People Growers Association (now We The People Opportunity Farm) to help formerly incarcerated individuals transition back into freedom.

“Melvin Parson Gardening during the Entrepreneurship Interview” / THF295369

What nutritionist would you feature in your poster depicting the power of healthy food and race activism?

“We The People Opportunity Center” T-Shirt, circa 2019 / THF185710

Learn more with a visit to our pop-up exhibit on the same topic in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation now through March 31.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

food insecurity, women's history, Henry Ford Museum, food, farms and farming, education, Civil Rights, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, African American history, #THFCuratorChat