Until We Meet Again

First of the 2020 crop of Firestone Farm Merino lambs: twins born April 11. A ram and ewe are showing a few of the prized wrinkles.

As I begin my second full year as director of Greenfield Village, I was truly looking forward to welcoming everyone back for our 91st season and sharing the exciting things happening in the village. Instead, as we all face a new reality and a new normal, I would like to share how, even as we have paused so much of our own day-to-day routines, work continues in Greenfield Village.

As we entered the second week of March, signs of spring were everywhere, and the anticipation, along with the preparations for the annual opening of Greenfield Village, were picking up pace. The Greenfield Village team was looking forward to a challenging but exciting year, with a calendar full of exciting new projects.

It's not only about the new stuff, though. We all looked forward to our tried-and-true favorites coming back to life for another season: Firestone Farm, Daggett Farm, Menlo Park, Liberty Craftworks and the calendar of special events, to name a few. Each of these has a special place in our hearts and offers its own opportunities for new learning and perspectives. Despite all our hope and anticipation for this coming year, however, our plans took a different direction.

As our campus closed this past March, it had long been obvious that the year was going to be very different than the one we had planned. The Henry Ford's leadership quickly assessed the daily operations in order to narrow down to essential functions. For most of Greenfield Village, this meant keeping what had been closed for the season closed. Liberty Craftworks, which typically continues to produce glass, pottery and textile items through the winter months, was closed, and the glass furnaces were emptied and shut down. This left the most basic and essential work of caring for the village animals to continue.

Here I am with the Percheron horse Tom at Firestone Barn, summer 1985.

As proud as I am to be director of Greenfield Village, I am equally proud, if not more so, to be part of a small team of people providing daily care for its animals. This work has brought me full circle to my roots as a member of the first generations of Firestone Farmers 35 years ago. It’s amazing to me how quickly the sights, sounds and smells surrounding me in the Firestone Barn bring back the routines I knew so well so long ago. I am also proud of my colleagues who work along with me to continue these important tasks.

The pandemic has not stopped the flow of the seasons and daily life at Firestone Farm. Our team made the decision very soon after we closed to move the group of expecting Merino ewes off-site to a location where they could have around-the-clock care and monitoring as they approached lambing time in early April. This group of nearly 20 is now under the watchful eye of Master Farmer Steve Opp in Stockbridge, Michigan, about 60 miles away.

Meet the newest members of the Firestone Farm family.

After their move, the ewes were given time to settle into their new temporary home. They were then sheared in preparation for lambing, as is our practice this time of year. I am very pleased to report that the first lambs were born Easter weekend, Saturday, April 11. All are doing well, and several more lambs are expected over the next few weeks. Once the lambs are old enough to safely travel, and we have a better understanding of our operating schedule looking ahead, they will all return to Firestone Farm, having the distinction of being the first group of Firestone lambs not born in the Firestone Barn in 35 years.

The last of the Firestone Farm sheep getting sheared in the Firestone Barn.

The wethers, rams and yearling ewes that remain at Firestone Farm were also recently sheared and are ready for the warm weather. One of the wethers sheared out at 18 pounds of wool, which will eventually be processed into a variety of products that are sold in our stores.

Continue Reading

farms and farming, farm animals, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Jim Johnson, Greenfield Village, COVID 19 impact

#InnovationNation: Social Transformation

aviators, flying, presidents, education, books, women's history, Abraham Lincoln, Ford Motor Company, World War II, airplanes, cars, limousines, presidential vehicles, Rosa Parks bus, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

Travel has changed a lot over the past 150 years, from something that only the wealthy could afford to something for everyone. This post looks at the relationship between forms of luggage and methods of transportation, from stagecoaches through airline travel.

THF206455 / Concord Coach Hitched to Four Horses in Front of Post Office, circa 1885.

In the 19th century, travel was relatively uncommon. People who traveled used heavy trunks to carry a great number of possessions, usually by stagecoach and rail. The traveler didn't usually hand his or her luggage, porters did all the work. As late as 1939, railway express companies transferred trunks to a traveler's destination.

THF288917 / Horse-Drawn Delivery Wagon, "Express Trunks Transferred & Delivered, We Meet All Trains"

A typical 19th century American trunk, this example was used by Captain Milton Russell during the Civil War.

THF174670 / Carpet Bag, 1870-1890

People used valises or other types of lighter bags in the 19th century. This is a carpet bag made of remnants of "ingrain" carpet.

THF145224 / Trunk Used for File Storage By Harvey S. Firestone, circa 1930

In the 19th and 20th centuries, "steamer trunks" were used on ocean-going vessels in your state room. It was literally a closet in a box. This example was used by Harvey Firestone to hold important papers.

THF105708 / Loading Luggage into the Trunk of 1939 Ford V-8 Automobile

With the rise of automobile travel, more people had access and suitcases (as we know them) became the norm. Much easier to manager than steamer trunks, they fit a car trunk.

THF166453 / Oshkosh "Chief" Trunk, Used by Elizabeth Parke Firestone, 1920-1955

This is a standard 1920s/1930s suitcase made by the Oshkosh Suitcase Co. of Oshkosh, Wisc. This was for auto travel, etc. It was for everything! This belonged to Elizabeth Parke Firestone.

THF285021 / Passengers Entering Ford Tri-Motor 4-AT Airplane, 1927

With the rise of air travel, passengers were limited to lighter-weight bags due to weight restrictions.

THF169109 / Orenstein Trunk Company Amelia Earhart Brand Luggage Overnight Case, 1943-1950

Famed aviator Amelia Earhart licensed her own line of luggage beginning in 1933. It was marketed as "real 'aeroplane' luggage." It was lightweight and made to last. (Learn more about the famed aviator as an entrepreneur in this expert set.)

THF318431 / Postcard, Plymouth Savoy 4-Door Sedan, 1961-1962

By the 1960s, fashionable Americans bought luggage in colorful sets, like this lady directing the porters. Notice she also has a steamer trunk!

THF154923 / Travelpro Rolling Carry-On Suitcase, 1997

With the explosive growth of air travel in the '80s & '90s, & the growth of airports, travelers needed light and portable bags. Roller bags were the answer. They could be carried on or checked.

THF94783 / American Airlines Duffel Bag, circa 1991

Flight attendants need to carry extremely light bags. This American Airlines tote bag was used by a flight attendant in the 1990s.

How have your luggage choices and preferences evolved over time?

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. These artifacts were originally shared as part our weekly #THFCuratorChat series. Join the conversation! Follow @TheHenryFord on Twitter.

If you’re enjoying our content, consider a donation to The Henry Ford. #WeAreInnovationNation

Connecting to the Natural World

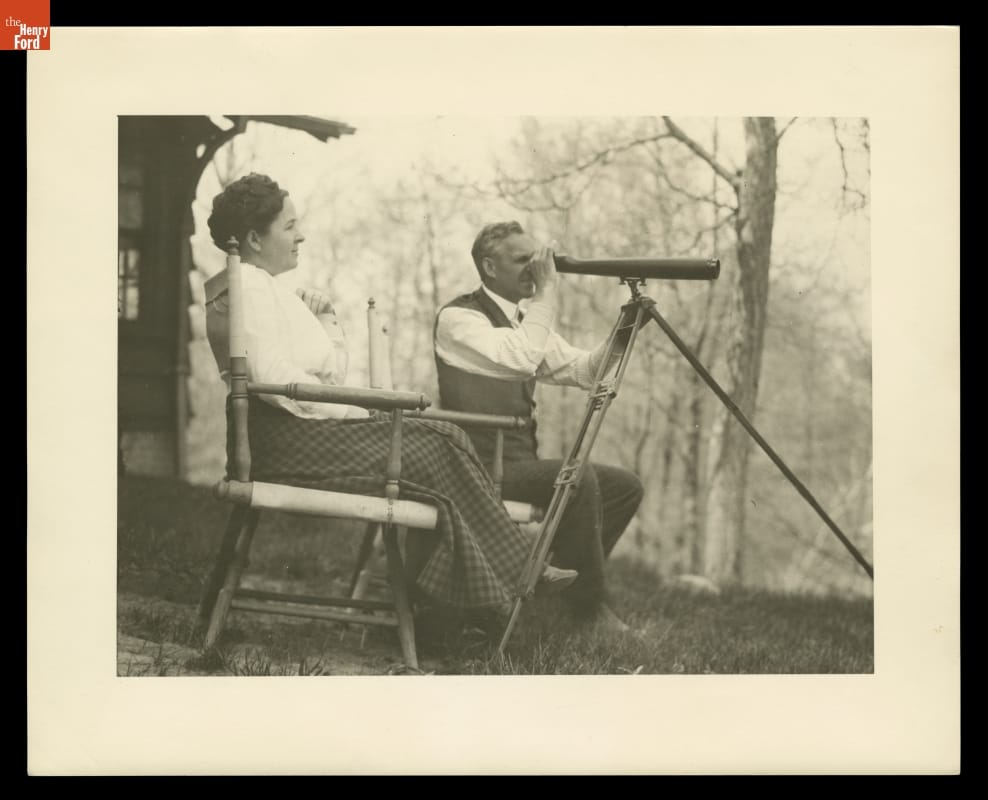

Henry and Clara Ford bird-watch near the Rouge River in Dearborn, Michigan. THF96013

Over the course of a few short weeks, our daily lives have been disrupted in an unprecedented way. For most of us, our daily schedules no longer require moving from place to place — from our homes to our workplaces, miles away.

In our rush to get to the next location, did we ever stop to think about the space we traveled through to reach our destination? Did we ever stop to admire the natural world that envelops our civilization?

We hastily moved through the world. Now, while many of us are temporarily stationary, the natural world continues its movement around us. This presents a unique opportunity. With less demand on where you have to be, take this chance to enjoy the beauty of that motion. All it takes is a look out the window or a step out the door.

Here are the stories of a few makers and doers from The Henry Ford’s collection whose connection to the natural world might just help you step back, admire, reconnect and recharge:

- Learn more about the life of naturalist and writer John Burroughs in this Google Arts & Culture digital exhibit. Or take a look through pressed wildflowers Burroughs collected on an 1899 trip to Alaska in this album.

- Agricultural scientist George Washington Carver was committed to teaching, serving the community and making a difference. Learn more about his work in this blog. Or take a read through one of his publications used by educators to teach kids about gardening.

- Glass artist Paul Stankard, considered one of the fathers of the studio glass movement, drew upon a deep connection with the natural world to intricately replicate flowers and other botanicals in his acclaimed paperweights. Learn more about Stankard’s life, work and inspiration through his own words in this Visionaries on Innovation interview.

- Before starting a national conversation on the use of pesticides, author Rachel Carson found success with her poetic book The Sea Around Us. A New York Times bestseller for nearly two years and winner of the John Burroughs Medal for nature writing, Carson's work can be checked out virtually for those who can’t make it outdoors.

Whether it’s a new flower blooming or the birds singing outside your window, find solace in the simple beauty of the world around you. Who knows, maybe the inspiration you find will lead you to spark a change in your own way.

Ryan Jelso is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

#InnovationNation: Design & Making

Take a look at a collection of clips showcasing design and making within the collections at The Henry Ford.

technology, African American history, quilts, fashion, manufacturing, Henry Ford Museum, Eames, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, making, design

Innovation Virtual Learning Series: Week 2

Welcome to week two of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Learning Virtual Series. Were you inspired to create or invent something this week? We want to see what you’re making! Please share your photos with us on #WeAreInnovationNation. If you missed the series last week, check out the recordings by clicking on the links at the bottom of this post. We hope that you will join us this week to explore our theme of Design & Making. Keep reading for more details about what’s in store.

What We Covered This Week

Theme: Design & Making — How do we collaborate and work with others?

STEAM Stories

This week is all about sand and glass. Join us for a reading of The Sand Castle Lola Built by Megan Maynor and then get hands-on activity ideas from our early childhood curriculum, Innovate for Tots. Register here.

#InnovationNation Tuesdays

See our design and making segments here.

Innovation Journeys Live!

How do artists use glass to create delicate works of art? Watch the story of studio glass unfold in a live innovation journey. Practice making your own journey using the Model i Primer activity. Register here.

#THFCuratorChat: Design & Making

Learn more about the evolution of luggage design from Curator of Charles Sable.

Kid Inventor Profile

Listen to serial inventor Lino as he discusses his three inventions: Kinetic Kickz, the String Ring and the Sole Solution. Then explore some Invention Convention Curriculum activities to keep your child innovating. Register here.

Resource Spotlight: Model i Primer+ Design Lesson

In our continued efforts to help parents, students and educators during these times of uncertainty, The Henry Ford is providing helpful tips to help parents adapt its educational tools for implementation at home. Last week we highlighted our Model i Primer, a facilitator’s guide that introduces the Actions of Innovation and Habits of an Innovator through fun, learn-by-doing activities.

This week we are highlighting the Model i Primer+. These five lesson plans, named after the Actions of Innovation, are designed as opportunities for students to practice the Actions and Habits introduced in the Model i Primer. Each lesson includes age-appropriate versions for grades 2-5, 6-8 and 9-12. In keeping with this week’s theme of Design & Making, we’ll focus on the Design lesson today. All you need for the lesson are some colored pencils or markers and paper.

We define designing as brainstorming solutions to a defined problem or need. This is one of the trickiest parts of any innovation journey for all inventors. In trying to solve a problem or need, kids can feel overwhelmed by a blank page, or they can get stuck on unfocused ideas. In order to help kids navigate these challenges, the Design lesson introduces two brainstorming techniques: the Zero Drafting technique and the Wishing technique.

Zero Drafting is an ideation technique that encourages kids to get their initial creative solutions out of their heads and on to paper, using information they already know. The Wishing technique encourages kids to frame solutions as wishes, making them more comfortable sharing ideas without pressure of producing real ideas. Combining Zero Drafting with Wishing, students focus on features of their creative ideas to trigger new, more realistic concepts to develop. By ideating feasible concepts, kids will be able to choose one solution to develop further.

When trying the Design lesson in your home, consider these adaptations for each of the lesson’s three parts:

Prep Activities: Begin by suggesting a problem that your kids may want to solve. This can be something simple, like a problem they have during their morning routine or always growing out of their shoes.

Core Activities: Use the Zero Drafting and Wishing techniques to brainstorm fantastical solutions, and then analyze these ideas to generate new, more realistic concepts. You can choose to just use one of the techniques. Brainstorm solutions along with your child.

Follow-Up Project: Have your child pick one of the solutions they came up with, and have them begin to write or draw ideas about how they would make that solution come true. You might be surprised by how your child begins to solve their own problems.

Take it further: Ask your child what Actions and Habits they practiced.

Please share your experience and follow others as they engage in our digital learning opportunities using the hashtag #WeAreInnovationNation.

Olivia Marsh is Program Manager, Educator Professional Development, at The Henry Ford.

by Olivia Marsh, Model i, educational resources, making, design, innovation learning

Look for the Helpers

Red Cross Volunteer Nurse's Aides, May 1942. THF289753

In uncertain times, it can be useful to stop and reflect on the ways in which others have overcome or responded to challenges. The passage of time can be a cushion, allowing us to use the lens of history to reach back and remember that remarkable creativity, kindness and courage have often pushed through fear in times of uncertainty.

Opportunities for compassion and ingenuity abound, even for those of us not on the front lines—be it the front lines of a hospital, of the food supply chain, or of municipal services. Perhaps your opportunity might be painting rocks to hide in your neighborhood to make a neighbor smile or sewing a mask for a health care worker. It could be putting groceries in your little library as well as books. Maybe it is inventing a vaccine or building new ventilators.

Let’s absolutely “look for the helpers,” as Mister Rogers said, but let’s also look for the makers, the inventors, the doers, the innovators—past and present—and be inspired to become more like them too. Encouragement from sidewalk chalk and painted rocks in a Michigan neighborhood.

Encouragement from sidewalk chalk and painted rocks in a Michigan neighborhood.

THF Resources

The Henry Ford's Blog: Uncovering Medical Innovations in the Collection

New surgical techniques and motorized medical care are just a few of the ingenious responses to medical demands featured in this blog post.

The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation: UpSee Walking Device

When Debby Elnatan’s son was unable to walk due to cerebral palsy, she invented a walking device to help him and other children with the disorder. In this clip from The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, she explains, “I believe there is no such thing as special needs, that we all have the same needs. What’s special are the solutions.”

The Henry Ford's Blog: A Technological Assist

Today, assistive devices and technology are increasingly common, but this wasn’t always the case. Empathetic design and inventiveness were required to create devices which allowed people like Shari, introduced in this blog post, to wake up on time, watch television, or chat with a friend.

Katherine White is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

COVID 19 impact, accessibility, healthcare, by Katherine White

Exposing the Collections Storage Building

This blog post is part of an ongoing series about storage relocation and improvements that we are able to undertake thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

A typical aisle in the Collections Storage Building before object removal.

Autumn of this year marks the end of a three-year IMLS-funded grant project to conserve, house, relocate and create a fully digital catalogue record for over 2,500 objects from The Henry Ford’s industrial collections storage building. This is the third grant THF has received from IMLS to work on this project. As part of this IMLS blog series, we have shown some of the treatments, digitization processes and discoveries of interest over the course of the project. Now, we’d like to showcase the transformation happening in the Collections Storage Building (CSB).

A view of the aisle and southwest wall before dismantling to create a Clean Room.

Objects were removed from shelves allowing an area in the storage building to be used as a clean space for vacuuming and quickly assessing the condition of these objects before heading to the conservation lab. Since the start of the grant in October 2017, 3,604 objects have been pulled from CSB shelves along with approximately 1,000 electrical artifacts and 1,100 communications objects from the previous two grants. As of mid-March 2020, 3,491 of those objects came from one aisle of the building. As a result, we were finally at a point of taking down the pallet racking in this area.

Pallets of dismantled decking and beams. A bit of cleaning before racking removal.

While it has taken multiple years to move these objects from the shelves, it took only three days to disassemble the racking! Members of the IMLS team first removed the remaining orange decking. On average, there were four levels of decking, separated in three sections per level. Next, we unhinged the short steel beams that attach the decking to the racking. Then was the difficult part of Tetris-style detachment of the long steel beams directly by the wall from the end section of height-extended, green pallet racking. As you can see this pallet racking almost touches the ceiling! After that, the long beams could be completely removed before taking down the next bay. Nine bays were disassembled this time to reveal the concrete wall and ample floor space. Just as the objects needed cleaning to remove years of dust and dirt, so did the floor!

The aisle in 2018. An open wall and floor!

What’s next? We will methodically continue pulling objects and taking down racking until no shelf is left behind! We are grateful to the IMLS for their continued support of this project and will be back for future updates.

Marlene Gray is the project conservator for The Henry Ford's IMLS storage improvement grant.

21st century, 2020s, 2010s, IMLS grant, collections care, by Marlene Gray, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Conscious Conservation Is In

The concept of resourceful living is nothing new. Many people have been reducing, reusing and recycling for years. But now that we find ourselves in the midst of a global pandemic, it seems that “conspicuous consumption” is out and “conscious conservation” is in.

"How to Fix Your Bicycle". THF206623

As we all learn to make do in our new world of social distancing and stay-at-home orders, here’s a look at how Americans have practiced resourceful living in the past. Whether it’s fixing the family car yourself, being proactive in your family’s health and well-being, or simply taking advantage of your extra at-home time to finally get organized, you’ll find much to inspire you in the collections of The Henry Ford.

In the Garage

The Railroad Roundhouse

“Fixing Cars, a People's Primer”

FIXD Car Diagnostic Sensor (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

“Anybody’s Bike Book”

“How to Fix Your Bicycle”

“A Rough Guide to Bicycle Maintenance”

Improvisation & Fixing Things

Whole Earth Catalogs

Quilt Maker Susana Hunter

Susana Hunter (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Revisit the Break, Repair, Repeat: Spontaneous & Improvised Design exhibit, on view Summer 2019

Video Tour of the Exhibit

Expert Set (Highlight Artifacts from the Exhibit)

Press Coverage by The Detroit News

Staying Healthy & Keeping Germs at Bay

Phone Soap (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Anti-Germ Sponge (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Historic Soap and Household Detergent Packaging

Braniff International Airways Bar Soap

For Health, Food and Fun Keep a Garden

An Organized Workspace

Julia Child’s Kitchen

Overhead Drawing of Julia Child's Kitchen

L. Miller & Son Store Displays of Hardware

Hoosier-Style Kitchen Cabinet

Handy Helper Utility Cabinet

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Did you find this content useful? Consider making a gift to The Henry Ford.

home life, healthcare, by Matt Anderson, environmentalism, COVID 19 impact

Home Entertainment

Portrait of Young Girl with Hoop and Stick, 1868-1870. THF226622

The challenges posed by COVID-19 have inspired us to figure out new ways of working — and also of playing. Our entertainment is now focused on what can be enjoyed in and around our homes.

The past century saw an explosion of entertainment choices to enjoy in our leisure time, and plenty of these remain accessible to help lift spirits and put smiles on our faces. Favorite music, movies and television shows are at our fingertips. Video and board games can be enjoyed. Craft projects await. Reading material surrounds us —found online, downloaded on tablets or discovered on our own bookshelves. Weather permitting, outdoor activities like walking, riding a bicycle or even barbecuing remain accessible — all while maintaining social distancing, of course!

Right now, for many, there is little physical or mental separation between work and leisure. Taking time to savor leisure activities while remaining at home helps renew energy and focus. There are so many ways to stay engaged. Enjoy!

Perhaps the close quarters many of us are currently experiencing may even inspire more face-to-face communication, creativity — and play.

Home Media Entertainment

Sesame Street 50th Anniversary

The Real Toys of Toy Story

Is That from Star Trek?

Star Wars: A Force to Be Reckoned With

Immersit Game Movement (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Travel Television with Samantha Brown's Passport to Great Weekends"

A TV Tour of the White House" with Jacqueline Kennedy

Edison Kinetoscope with Kinetophone

Allan McGrew and Family Reading and Listening to Radio

Staying Busy with Games

Games and Puzzles

Board Games

McLoughlin Brothers: Color Printing Pioneers

Playing Cards

Girl with Hoop and Stick

Alphabet Blocks and Spelling Toys

CBS Sunday Morning with Mo Rocca: Piecing together the history of jigsaw puzzles

Crafting at Home

Leatherworking Kit

Paragon Needlecraft American Glory Quilt Kit

Carte de Visite of Woman Knitting

Video Games

History of Video Games (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Player Up: Video Game History

Unearthing the Atari Tomb: How E.T. Found a Home at The Henry Ford

Reading for Pleasure

Comic Books Under Attack

Commercializing the Comics: The Contributions of Richard Outcault

The "Peanuts" Gang: From Comic Strip to Popular Culture

It All Started with a Book: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Woman Reading a Book

John Burroughs in His Study

Staying Engaged & Family Activities

Partio Cart Used by Dwight Eisenhower

Connect 3: Guided Creativity

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Did you find this content of value? Consider making a gift to The Henry Ford.

by Jeanine Head Miller, books, video games, radio, TV, movies, making, toys and games, COVID 19 impact