Posts Tagged music

Behind Every Object Is a Story

The author at his desk at The Henry Ford. / Photo by Jeanine Head Miller

I grew up on Detroit’s far west side, just north of Dearborn, during the 1950s and 1960s. History was always my favorite subject, and I fondly remember school field trips to what was then called Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. I can trace my interest in American history to those visits and remember thinking how great it would be to work there someday.

I graduated from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1975 with a bachelor's degree in history. My original intention was to become a history teacher, but with teaching positions few and far between in those days, I ended up accepting a position in the mortgage department of Comerica Bank and stayed there for nearly 30 years.

I retired in 2008 and became a volunteer at The Henry Ford. After three years of doing computer data entry in the marketing department and helping at special events like Maker Faire, Old Car Festival, and Motor Muster, I met Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Jeanie was looking for a volunteer curatorial research assistant to work with her in the Historical Resources department. She was willing to take a chance on me, even though my professional life had been spent in banking, not historical research. The learning curve was steep, but with Jeanie’s knowledge and patience, I learned the ropes.

My primary focus as a volunteer has been to research the lives of some of the people who owned, made, or used the objects in The Henry Ford’s collection. Most of them were ordinary people, using these objects as part of their everyday activities.

Uncovering People’s Stories

I first look for clues in the object’s accession file—a file that contains whatever information we know about the object. Sometimes I find letters from the donor, often a descendent of the original owner, providing some family history and information about the maker or owner of the object, or how it may have been used. More often, though, there may be only a few clues—a name or a place. From these clues, I start my search to learn more about the background of the individual or family and the context of the object.

The advent of the Internet and genealogy websites like Ancestry.com—with access to census records, city directories, birth and death records, and other information—make researching the life of someone born more than a hundred years ago much easier. The census records are a particularly valuable tool in my research. They provide information about a person’s occupation, age, place of birth, marital status, immigration status, place of residence, home ownership, and more. The census also lists all the people living in the same home and their relationship to the head of the household.

Sites like Newspapers.com, with its access to many newspapers nationwide, can provide a wealth of information. I often find marriage and birth announcements, obituaries, and other information. Local historical societies are also a great research resource. I encounter other dedicated volunteers willing to search local records for information on people I am searching for—information not available online.

Conrad Hoffman’s Violin

Violin used by Conrad Ambrose Hoffman, 1793. / THF180694

A few years ago, The Henry Ford acquired a violin used by Conrad Ambrose Hoffman (1839–1916), a musician and teacher from Pontiac, Michigan. The violin had been made in 1793 by Czech violin maker Johann Michael Willer (1753–1826). The family not only donated Hoffman’s violin and bow, but also related archival materials, including concert programs, sheet music and librettos, calling cards, and stationery.

These materials helped provide some information about Hoffman. But further research in sources like Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com, and the Palmer Family Papers: 1853–1940 at University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library helped me enrich Hoffman’s story.

The United States census records for Conrad Hoffman revealed that he was born in New York in 1839, but moved to Oakland County, Michigan, with his family by 1840. His father, Ambrose D. Hoffman (1806–1881), made his living as a farmer and cooper. The 1870 census revealed that 31-year-old Hoffman was employed as a music teacher and was living at the family home in Pontiac, Michigan, with his parents and two sisters.

Most of the information I discovered about Hoffman’s life as a musician and teacher came from a biography that I found on Google Books, Biographical Sketches of Leading Citizens of Oakland County, Michigan, published in 1903. The account recalled Hoffman’s early interest in music, the musical abilities of his mother and sisters, and his study of the violin as a young boy—including his traveling to Dresden, Germany, to study music at the Dresden Conservatorium.

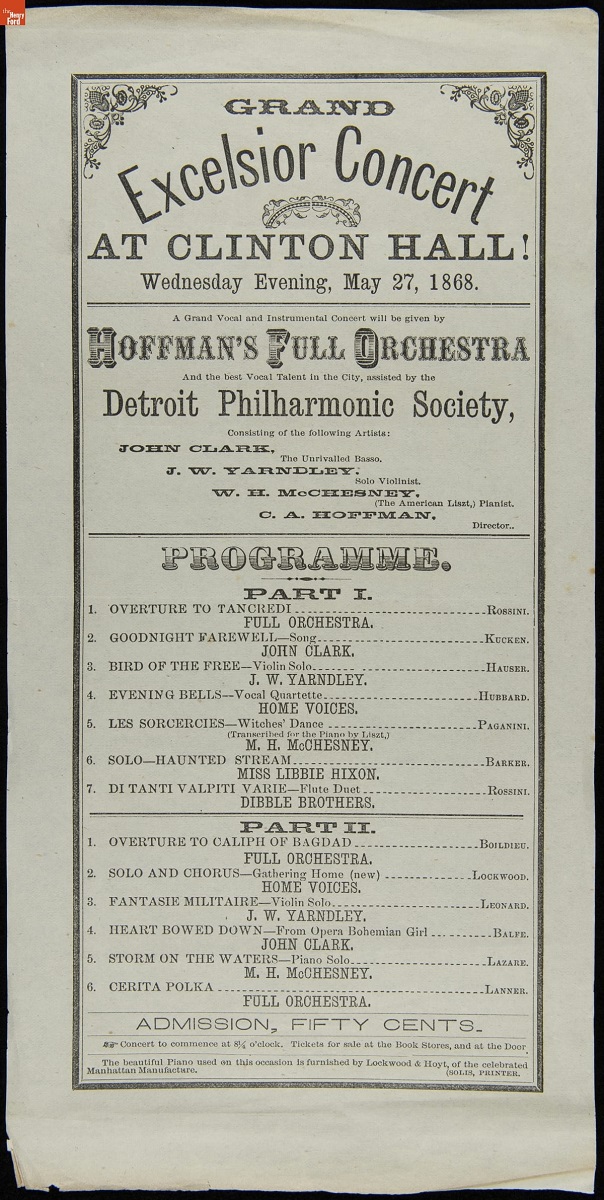

Hoffman and his orchestra performed at Clinton Hall in Pontiac, Michigan, on May 27, 1868. / THF279100

Hoffman’s biography also revealed that he served in the Union Army during the Civil War as a musician with the 15th Michigan Volunteer Infantry. In the years following the war, Hoffman organized an orchestra in the Pontiac area.

Conrad Hoffman performed at this concert at the Music Hall in Holly, Michigan, on May 24, 1866. / THF279106

Concert programs from the 1860s and 1870s document Hoffman’s performances in places like Birmingham, Holly, and Pontiac, Michigan. He performed as a solo violinist, as well as a conductor.

I discovered through a marriage announcement, published in the Detroit Free Press on September 25, 1900, that Conrad Hoffman married for the first time at the age of 60. His bride was childhood friend and pianist Philomela Cowles Palmer (1851–1930). Philomela was the daughter of Charles Henry Palmer (1814–1887) of Pontiac, an entrepreneur who was instrumental in helping develop Michigan’s copper industry.

Conrad Hoffman died in 1916. His obituary, found on Newspapers.com, was published in the Detroit Free Press on December 9, 1916. The obituary described Mr. Hoffman as a well-known violinist, the owner of a collection of old violins, and the instructor of several of the best-known Michigan violinists and violin teachers.

Audrey Wilder’s Dress

Audrey Wilder’s blue 1920s dress is second from the right.

In the fall of 2019, Jeanie Miller asked me to find out what I could about the life of Audrey Kenyon Wilder (1896–1979) of Albion, Michigan. Jeanie planned to use Wilder’s 1920s dress for an exhibit called What We Wore: A Matter of Emphasis in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. My task was to find out as much as I could about Wilder to help tell the story of the dress and the woman who wore it.

The donor correspondence in the accession file for Wilder’s dress provided just a few clues—her name and place of residence. I guessed Audrey Wilder’s birth date would be about 1900, based on the age of the dress. I was able to find four-year-old Wilder in the 1900 U.S. Census, living with her parents at the home of her paternal grandparents in Albion, Michigan. Her father was the owner of a lumber yard in Albion.

Yearbooks from high schools and colleges, which I found on Ancestry.com, provided information about Wilder’s education and career. I learned that she graduated from Albion High School in 1914, Albion College in 1918, and earned a master's degree from Columbia University in 1921. Wilder began teaching English at Albion College that same year.

In 1928, Audrey Wilder left Albion College to serve as Dean of Women at Ohio Northern University in Ada, Ohio. I was able to find an article written about her on Google Books, which shed some light on Audrey’s life and activities during this period of her life. The November 1935 issue of her college sorority newsletter, Anchora of Delta Gamma, published a story about Audrey’s life and career, entitled “Audrey Kenyon Wilder, Ohio Northern’s Dynamic Dean.” She is described as a woman “of exquisite grooming” and as having established the first social hall for women on the Ohio Northern campus, providing a setting for the female students on campus to hold teas, receptions, and co-ed dinners.

Dress owned by Audrey Wilder, 1927–1929 / THF177877

Tying an object to the story of its owner is the goal of my research. It is not hard to imagine Audrey Kenyon Wilder, the dynamic dean of exquisite grooming, attending a campus social function wearing the dress which is now part of the collection at The Henry Ford.

“Shopping” for the Collection

At times, I have assisted the curatorial staff in locating items for the museum’s collection. The curators identify a desired object and I then search eBay and other Internet sites to try to locate one in good condition. I then show the possibilities to the curator or curators, who select and acquire the object. These Internet sites make the search easier, but it often requires patient searching—sometimes for months.

Amelia Earhart brand overnight case made by the Orenstein Trunk Company, 1943–1950. / THF169109

One example is an Amelia Earhart brand suitcase. Earhart endorsed various products, including a line of luggage, in order to finance her aviation activities. I searched for six months and found one in like-new condition with the original price tag and keys! Though this example dates from the decade following Earhart’s disappearance, it attests to the staying power of the Earhart brand—this luggage line sold well for decades. This suitcase is on display in the museum’s Heroes of the Sky exhibit, in the section dedicated to Amelia Earhart.

I could not have asked for a more rewarding and interesting way to spend some of my time during my retirement years. I was finally able to find that “job” that I thoroughly enjoy and never get tired of. With millions of artifacts in the collection at The Henry Ford, there is always another life to explore and, for me, another adventure.

Gil Gallagher is Curatorial Research Volunteer at The Henry Ford.

Heroes of the Sky, women's history, Henry Ford Museum, What We Wore, fashion, Michigan, music, musical instruments, violins, The Henry Ford staff, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Gil Gallagher, research

Disney Songs as Storytellers

Poster for Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume.

Poster for Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume.Inspired by the creative thought process of founder Walt Disney, everything that the Walt Disney Company does is based upon the power of story. This can range from the plot of a film to the backstory of a theme park attraction. In all cases, the sets, props, and costumes help to provide clues for the audience about story elements and characters.

The songs in a Disney film can also enhance the story, moving it forward through emotion, detail, and nuance. Through songs, the characters become more believable, helping the audience become more invested in the story. Here are some classic examples.

Babes in Toyland

Babes in Toyland was a popular 1961 Christmas musical featuring a cast of Mother Goose characters. It starred Annette Funicello as Mary Quite Contrary, Tommy Sands as Tom Piper, Ray Bolger as the evil and villainous Barnaby, and Ed Wynn as the Toymaker. Annette Funicello later recounted that this was her favorite filmmaking experience.

The film was based upon Victor Herbert’s popular 1903 operetta of the same name. Herbert, a composer, wrote it with Glen McDonough, an opera librettist, in an attempt to outdo the extremely popular stage musical The Wizard of Oz, then playing on Broadway. (This was, of course, decades before the 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz.) The Babes in Toyland operetta continued to be performed for many years on the stage, where it was embraced as a children’s classic.

Disney’s was the second film version of the Babes in Toyland operetta released at movie theatres (the first was a film by Laurel and Hardy) and it was the first in Technicolor. In the Disney version, the plot was changed quite a bit and many of the song lyrics were rewritten. Some of the song tempos were even sped up.

“March of the Toys” is the best-known portion of the score of Babes in Toyland. It was used in the sequence in which the Toymaker displays his toys for the human children who have strayed into Toyland. One can almost imagine the toys coming alive in this lively up-tempo march.

“Toyland,” a whimsical song about a magical land filled with toys for girls and boys, also debuted in the original version of Babes in Toyland. This song still shows up on Christmas playlists, as it has been covered by many vocalists over the years, including Nat King Cole, Perry Como, Jo Stafford, Johnny Mathis, and—most notably—Doris Day.

Into the Woods

“No One is Alone” comes from the 2014 Disney musical fantasy film Into the Woods, which was adapted from a 1986 musical theater production. This song was created by American composer, songwriter, and lyricist Stephen Sondheim. It appears at the end of Act II, as the four remaining leads (the Baker, Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, and Jack) try to understand the consequences of their wishes and decide to place community wishes above their own. The song serves to demonstrate that even when life throws its greatest challenges, you do not have to face them alone.

With its universal theme, this song has been used for many other purposes, including the Minnesota AIDS Project in 1994, and a speech by President Barack Obama during the tenth anniversary of 9/11.

Although this film is lesser known than many other Disney live-action films, Stephen Sondheim is one of the most important figures in 20th-century musical theater, known for tackling dark, complex, unexpected themes that range far beyond the genre’s traditional subjects. He wrote the music for West Side Story, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Beauty and the Beast

Costumes from the live-action movie Beauty and the Beast in the Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume exhibit. / THF191450

The song “Beauty and the Beast” was written by lyricist Howard Ashman and composer Alan Menken for the Disney animated feature film of the same name (1991). This, truly the film’s theme song, was recorded by American-British-Irish actress Angela Lansbury in her role as the voice of the character Mrs. Potts. Lansbury was hesitant to record “Beauty and the Beast” because she felt that it was not suitable for her aging singing voice, but ultimately she completed the song in one take. It was also recorded as a pop song for the closing credits by the duet of Canadian singer Celine Dion and American singer Peabo Bryson. It was released as the only single from the film’s soundtrack. Both versions of “Beauty and the Beast” were very successful, garnering both Golden Globe and Academy Awards for Best Original Song.

Considered to be among Disney’s best and most popular songs, “Beauty and the Beast” has since been covered by numerous artists. In the 2017 live-action adaptation of the animated film, it was sung by Emma Thompson as Mrs. Potts and as a duet by Ariana Grande and John Legend during the end credits. In addition to Beauty and the Beast, Howard Ashman and Alan Menken collaborated on the music and lyrics for two other beloved Disney animated films—The Little Mermaid and Aladdin—before Ashman’s untimely death in 1991.

Mary Poppins

Costume from Mary Poppins in the Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume exhibit. / Photo by Real Integrated for The Henry Ford

Mary Poppins was an incredibly popular 1964 Disney live-action film. All the songs for this film were written by the inimitable Sherman brothers. Robert and Richard Sherman were hired by Walt Disney himself to be his staff songwriters in 1961. While at Disney, they wrote more motion-picture musical scores than any other songwriters in the history of film, including Mary Poppins, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, all but one song from The Jungle Book, Bedknobs and Broomsticks, and The Aristocats. But they are possibly best known for their can’t-get-them-out-of-your-head songs from two Disney theme park attractions: “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow” from the Carousel of Progress and “It’s a Small World (After All)” from the attraction of the same name.

But, back to Mary Poppins. First, the song “Feed the Birds” speaks of an old beggar woman who sits on the steps of St. Paul’s Cathedral, selling bags of breadcrumbs to passers-by for tuppence a bag so they can feed the pigeons. The scene is reminiscent of the real-life seed vendors of Trafalgar Square in London. It is intended to be a lesson about charity and the merits of giving to others.

The song was regarded as one of Walt Disney’s favorite songs. Robert Sherman recalled:

“On Fridays, after work, Walt Disney would often invite us into his office and we’d talk about things that were going on at the Studio. After a while, he’d wander to the north window, look out into the distance and just say, ‘Play it.’ And Dick would wander over to the piano and play ‘Feed the Birds’ for him. One time just as Dick was almost finished, under his breath, I heard Walt say, ‘Yep. That’s what it’s all about.’ ”

“A Spoonful of Sugar Helps the Medicine Go Down” is an up-tempo number sung by Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins as she instructs the children, Jane and Michael, to clean their room. Although the task is daunting, she tells them that, with a good attitude, it can be fun. Story has it that Robert Sherman, the primary lyricist of the duo, worked an entire day trying to come up with a song idea for this scene. As he walked in the door at home that evening, his wife, Joyce, informed him that the children had gotten their polio vaccine that day. He asked his son Jeffrey if it hurt, thinking he had received a shot. Jeffrey responded that the medicine was put on a cube of sugar and that he swallowed it. By the next morning, Robert had the title of his song. Richard put a melody to the lyric and the song was born.

Finally, “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” is sung by Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins and Dick Van Dyke as Bert the chimney sweep in the live-action film’s unique animated sequence—just after Mary Poppins wins a horse race. Flush with her victory, she is immediately surrounded by reporters who pepper her with leading questions and comment that she is probably at a loss for words. Mary disagrees, suggesting that at least one word is appropriate for the situation—a word to say when you have nothing to say, and that is: Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!

The Sherman Brothers have given several conflicting explanations for this word’s origin, in one instance claiming to have coined it themselves. But, this was disproven when two other songwriters sued the Walt Disney Company, claiming to have written a song using that word in 1949. The Disney publishers ultimately won the lawsuit because they produced affidavits showing that many variants of the word had been known prior to 1949.

These are just a few of the many memorable songs that enhance the stories in Disney animated and live-action films. Which songs from Disney films are your favorites?

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Remembering Anne Parsons

Anne Parsons (at right), then-President of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, with Patricia Mooradian, President and CEO of The Henry Ford, at Salute to America in 2017.

We are saddened by the passing of Anne Parsons, President Emeritus of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (DSO). Parsons was the longest-serving executive leader in the DSO's modern era, and she was a tremendous friend to The Henry Ford. We’ve had the great honor and privilege of working with Anne and her teams for more than 25 years with our Salute to America concerts in Greenfield Village.

Please join us in thoughts and prayers for Parsons' family, her friends, and the entire DSO community.

women's history, events, Greenfield Village, Salute to America, Michigan, Detroit, music, in memoriam

Ford Novelty Band Playing at Ford Baseball Team Game, 1941 / THF271722

Every month, we feature some items from our archives in our History Outside the Box program. You can check the new story out on The Henry Ford’s Instagram account on the first Friday of the month, but we’re reposting some of the stories here on our blog as well. In May 2021, Reference Archivist Kathy Makas shared photographs, articles, and other documents ranging from the 1910s through the 1950s that detail how employees at Ford Motor Company spent their leisure time. Learn more about Ford’s musical groups, sports teams, gardeners, and social/service clubs in the video below.

Continue Reading

Dearborn, Michigan, 20th century, sports, music, History Outside the Box, gardening, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, by Kathy Makas, by Ellice Engdahl, archives

Equality and Accessibility in Music: Music Not Impossible

Mick Ebeling, founder of Not Impossible Labs, home of Music: Not Impossible. / Photo courtesy Not Impossible Labs

Film producer Mick Ebeling founded Not Impossible Labs to be a tech incubator with the mission of righting wrongs with innovation. Since then, his credo to “create technology for the sake of humanity” has resulted in developments like an invention allowing people who are paralyzed to communicate using only their eye movements and 3D-printed arms for Sudanese children who’ve lost limbs to war. So when Ebeling witnessed a concert for deaf listeners—where the music was turned up loud enough for the crowd to feel the vibrations—around the same time as a friend lost his sense of smell in a skateboarding accident, he had a revelation. “He didn’t fall on his nose—he fell on his head,” Ebeling said. “That means you don’t smell with your nose. You smell with your brain, which means you don’t hear with your ears, you do that with your brain too. So what if we went around and kind of subverted the classic way that people hear and we just took a new pathway to the brain?”

Thus was born the Music: Not Impossible project. Ebeling enlisted Daniel Belquer, a Brazilian music composer and technologist, to be the “mad scientist” shepherding the endeavor. Belquer was obsessed with vibration and tickled by the observation that skin could act as a substitute for the eardrum. “In terms of frequency range, the skin is much more limited than the ears,” said Belquer, “but the skin is better at perceiving texture.”

Belquer and Ebeling worked with engineers at Bresslergroup, Cinco Design, and Avnet, in close collaboration with members of the deaf community, to create the current version of a wearable device consisting of a “vibrotactile” vest, wrist straps, and ankle straps. The harness features 24 actuators linked to different instruments and sounds that distribute vibrations all over the body. The system is totally customizable and could, for example, have the drums vibrate the ankles, guitars stimulate the wrists, basslines rumble along the base of the spine, vocals tickle the chest, and so on.

Mick Ebeling and Daniel Belquer worked with leading engineers and members of the deaf community to create the current version of their wearable device, which consists of a “vibrotactile” vest, wrist straps, and ankle straps. / Photos by Cinco Design

“What we’re doing is transforming the audio into small packets of information that convey frequency amplitude in the range that our device can recognize,” Belquer said. “And then we send this through the air to the technology of the device. The wearables receive that information and drive the actuators across the skin, so you get a haptic [a term describing the perception of objects by touch] translation of the sound as it was in its source.”

As the team tested prototypes and held demo events, they also discovered the device has benefits for hearing listeners as well as deaf ones. “We can totally provide an experience that is both auditory and haptic,” said Belquer. “So with the vibration and the music, you hear it and you feel it and you get gestalt. This combined experience is more powerful than the individual parts. It’s like nothing you’ve ever felt.”

Photo courtesy Not Impossible Labs

The project won silver in the Social Impact Design category at the 2020 Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA) International Design Excellence Awards (IDEA), which are hosted at The Henry Ford. Here’s what Marc Greuther, vice president at The Henry Ford and an IDEA juror, had to say about the project: “I like to think of design as an essentially friction-reducing discipline, reducing chafing in the functional, aesthetic, or durability realms—of design building bridges, shortening the route between user and a known destination promised by a tool’s outcome, whether it’s a really good cup of coffee, a comfortable office chair, or an intuitive e-commerce interface. Music: Not Impossible grabbed my attention for going an order of magnitude further—for bridging unconnectable worlds, making sound and music accessible to the deaf. In his design checklist, Bill Stumpf said good design should ‘advance the arts of living and working.’ Music: Not Impossible fulfills that goal by creating an opening into a vast landscape—not by reducing friction but by removing a wall.”

“In the beginning, people would say this might be something like Morse code or Braille, that you have to go through an educational process in order to understand,” said Belquer. “But as an artist, I was always against a learning curve. You might not know or like a specific kind of music or style, but you can relate to what the emotional message of the content is. You don’t need to be trained in order to have the experience and be impacted by it.”

Photo courtesy Not Impossible Labs

What may be most remarkable about the project is that it creates a shared experience among people who might not have had one otherwise. From what the Music: Not Impossible team has witnessed so far, wearing the device can be just as intense and euphoric for folks who can hear as those who can’t. “We’ve had maybe 3,000 demo participants at this point,” said Belquer, “and there’s this face we always see: Their eyes open wide and their mouth and jaw drops as they have this ‘wow!’ moment.”

Mike Rubin is a writer living in Brooklyn, and Jennifer LaForce is Editorial Director at Octane and Editor of The Henry Ford Magazine. This post was adapted from “Where Can Sound Take Us?,” an article in the June–December 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

design, inventors, by Jennifer LaForce, by Mike Rubin, music, The Henry Ford Magazine

Healing in Music: Lavender Suarez Sound Healing

Lavender Suarez. / Photo by Jenn Morse

Lavender Suarez has made music as an experimental improviser for over a dozen years as C. Lavender and studied the philosophy of “deep listening” with composer Pauline Oliveros, which helped her understand the greater impact of sound in our daily lives. But it was seeing fellow artists and friends experience burnout from touring and stress that inspired her to launch her own sound healing practice in 2014.

“Many artists are uninsured, and I wanted to help them recognize the importance of acknowledging and tending to their health,” she said. “It felt like a natural progression to go into sound healing after many years of being a musician and studying psychology and art therapy in college.”

Suarez defines sound healing as “the therapeutic application of sound frequencies to the body and mind of a person with the intention of bringing them into a state of harmony and health.” Suarez received her certification as a sound healer from Jonathan Goldman, the leader of the Sound Healers Association. She recently published the book Transcendent Waves: How Listening Shapes Our Creative Lives (2020, Anthology Editions), which showcases how listening can help us tap into our creative practices. She also has presented sound healing workshops at institutions like New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and Washington, D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum.

Continue Reading

healthcare, by Mike Rubin, The Henry Ford Magazine, women's history, music

Mentorship in Music: Waajeed of Underground Music Academy

Waajeed. / Photo by Bill Bowen

Waajeed has worn many hats in his musical career. Besides the stylish Borsalino he usually sports, he’s been the DJ for rap group Slum Village, half of R&B duo Platinum Pied Pipers, an acclaimed producer of hip-hop and house music, and proprietor of his own label, Dirt Tech Reck. But it’s his latest venture that feels closest to his heart: educator.

The 45-year-old Detroit native is now the director of the Underground Music Academy (UMA), a school set to launch in 2022 that will guide students through every step of tackling the music industry obstacle course. “You can learn how to make the music, put it out, publish it, own your company, and reap the benefits,” he said of his vision for UMA. “A one-stop shop.”

Photo by Bill Bowen

While Waajeed initially broke into music via hip-hop, UMA will, at least at first, focus on electronic dance music. Detroit is internationally renowned for techno, a form of electronic dance music first created in the Motor City in the mid-1980s by a group of young African American producers and DJs. But as the music exploded globally, particularly in Europe, techno became associated with a predominantly white audience. While Detroit’s pioneers were busy abroad introducing the music to foreign markets, the number of new, young Black practitioners at home kept dwindling.

UMA’s initial spark hit Waajeed a few years ago, when he was spending endless hours on planes and in airports, jetting to DJ gigs around the world. “On almost every flight I jumped on, I didn’t see a lot of people that looked like me, and it didn’t feel right,” he said. “All of this energy that’s being put into building Europe’s connection to our music and our past and our history, and it’s like, this needs to be happening in our own backyard. It was an awakening.”

Waajeed performing at Brunch Electronik Lisboa in Portugal. / Photo courtesy Brunch in the Park

Waajeed spoke to Mike Banks, a founder of the fiercely independent techno collective Underground Resistance, about how best to communicate to younger Black listeners that this music, primarily associated with Germans and Brits for the last 30 years, is actually an African American art form. The genesis of UMA flowed from their discussions. Waajeed described Underground Resistance’s credo of self-determination and mentorship as “a moral and business code that’s been the landmark cornerstone for our community.”

Another huge inspiration came from older musicians like Amp Fiddler, a keyboardist for Parliament-Funkadelic whose home in Detroit’s Conant Gardens neighborhood was close to Waajeed’s high school, Pershing. Whenever Waajeed and his friends (like future hip-hop producer J Dilla) skipped class, they’d end up in Fiddler’s basement, where he taught the teens how to use instruments and recording gear. “It started with people like Amp,” Waajeed said, “taking these disobedient kids in the neighborhood and giving us a shot in his basement, to trust us to come down there and use what felt like million-dollar equipment at the time, teaching us how to use those drum machines and keyboards. Amp put us in the position to be great at music.”

After years in the making, Waajeed is hoping to welcome students to the physical space for his Underground Music Academy in 2022. It will be located on Detroit’s East Grand Boulevard, near the internationally known Motown Museum. / Photo by Bill Bowen

Waajeed hopes UMA will institutionalize that same “each one teach one” tradition, not only with respect to music-making but also business and social acumen. “I heard stories about people who worked with Motown that would teach you what forks to use so you could sit down for a formal dinner, and that’s what I’m more interested in,” he said. “As much as being a beat maker is important, it’s just as important to be a person who is adamant about your business: knowing how to handle yourself the first time you go on tour, or how to set up publishing companies and bank accounts for those companies. That’s what we’re trying to do, to make that instruction more available so you have no excuses to fail.”

Until the physical space is ready to host students—scheduled for 2022, though the COVID-19 pandemic may alter that plan—UMA is concentrating on video tutorials that can be watched online, as well as fundraising, curriculum planning, and brainstorming about how best to reach the academy’s future pupils.

Waajeed sits on the steps of the future Underground Music Academy in Detroit. / Photo by Bill Bowen

“The result of this is something that will happen in another generation from us. We just need to plant the seed so that this thing will grow and be something of substance five or ten years from now,” Waajeed said. “I would be happy with a new generation of techno producers, but I would be happier with a new generation of producers creating something that has never been done before.”

Mike Rubin is a writer living in Brooklyn. This post was adapted from “Where Can Sound Take Us?,” an article in the June–December 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

The Henry Ford Magazine, school, popular culture, Michigan, Detroit, African American history, education, by Mike Rubin, music

Scotch Settlement School: A Community Christmas Celebration

Scotch Settlement School in Greenfield Village. / Photo courtesy of Jeanine Miller

Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village offers an engaging look into the ways Americans celebrated Christmas in the past. At Scotch Settlement School, the holiday vignette reflects the Christmas programs that took place in the thousands of one-room schoolhouses that once dotted the landscape of rural America.

Students and teacher pose outside their rural one-room school in Summerville, South Carolina, about 1903. / THF115900

The schoolhouse—often the only public building in the neighborhood—was a center of community life in rural areas. It was not only a place where children learned to read, write, and do arithmetic, but might also serve as a place to attend church services, go to Grange meetings, vote in elections, or listen to a debate.

Students dressed in patriotic costumes for a school program, pageant, or parade, about 1905. / THF700057

People in rural communities particularly looked forward to the programs put on by the students who attended these schools—local boys and girls who ranged in age from about seven to the mid-teens. School programs were often presented throughout the year for occasions such as George Washington and Abraham Lincoln’s birthdays, Arbor Day, Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and eighth-grade graduation. People came from miles around to country schools to attend these events.

Handwritten Christmas program from Blair School, Webster County, Iowa, December 23, 1914. / THF700097, THF700098

Among the most anticipated events that took place at the schoolhouse was the Christmas program—it was a highlight of the rural winter social season. Preparations usually started right after Thanksgiving as students began learning poems and other recitations, rehearsing a play, or practicing songs. Every child was included. Students might have their first experience in public speaking or singing before an audience at these school programs.

Interior of Scotch Settlement School during Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village. / Photo courtesy of Jeanine Miller.

The schoolroom was often decorated for the occasion, sometimes with a Christmas tree. During the late 1800s, when the presence of Christmas trees was not yet a widespread tradition, many children saw their first Christmas tree at the school Christmas program. Presents like candy, nuts, fruit, or mittens—provided by parents or other members of the community—were often part of the event. Growing up in the 1870s frontier Iowa, writer Hamlin Garland recalled the local minister bringing a Christmas tree to the schoolhouse one Christmas—a tree with few candles or shiny decorations, but one loaded with presents. Forty years later, Garland vividly remembered the bag of popcorn he received that day.

Teachers were often required to organize at least two programs a year. Teachers who put on unsuccessful programs might soon find themselves out of a teaching position. Teachers in rural schools usually came from a similar background to their students—often from the same farming community—so an observant teacher would have understood the kind of school program that would please students, parents, and the community.

Children at times performed in buildings so crowded that audience members had to stand along the edges of the classroom. Sometimes there wasn’t room for everyone to squeeze in. To see their parents and so many other members of the community in the audience helped make these children aware that the adults in their lives valued their schoolwork. This encouraged many of the students to appreciate their opportunity for education—even if they didn’t fully realize it until years later. Some children might even have been aware of how these programs contributed to a sense of community.

Postcard with the handwritten message, “Our school have [sic] a tree & exercises at the Church across from the schoolhouse & we all have a part in it,” from 11-year-old Ivan Colman of Tuscola County, Michigan, December 1913. / THF146214

These simple Christmas programs—filled with recitations, songs, and modest gifts—created cherished lifelong memories for countless children.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

childhood, music, actors and acting, events, holidays, Christmas, education, school, Scotch Settlement School, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Holiday Nights, by Jeanine Head Miller

Operating the Marionettes in Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little Marionette Show at the A.B. Dick Company Exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623950

The A.B. Dick Company, a major copy machine and office supply manufacturer, wanted to draw a crowd to its 1939 New York World’s Fair exhibition. The company decided that a musical marionette show, Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little, was just the ticket. A.B. Dick selected Tatterman Marionettes, a high-quality touring company managed by Edward H. Mabley (1906–1986) and William Duncan (1902–1978). Mabley wrote the musical comedy and Duncan produced the show, staged at the entrance to the A.B. Dick display in the Business Systems and Insurance Building.

A.B. Dick Company Mimeograph Exhibit and Writer’s Cramp Marionette Show at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623944

Writer’s Cramp featured changes in communication technology from “the days of the cave man” to the efficient modern office mimeograph machine. Marionettes represented Miss Jones, the secretary, and Mr. Whalen, the executive, trying to rush distribution of important correspondence. Father Time helped inform Mr. Whalen of his good fortune at present (1939) by escorting him through millennia of changes, starting with Stone Age stenographers, and including tombstone cutting, monks with their quill pens, and typists with their typewriters. The play culminated with the unveiling of A.B. Dick Company’s Model 100 Mimeograph, “the World’s Fairest writing machine!”

Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little Marionette Show at the A.B. Dick Company Exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623948

Mabley and Duncan organized Tatterman Marionettes in Detroit, Michigan, in 1922, and had relocated to Cleveland, Ohio, by 1930. They established a reputation through high-quality performances to a range of audiences.

Panel 4 of promotional material, “A Modern Adult Program and a New Children’s Program for the Tatterman Marionettes,” 1931-1932 / THF623902

Edsel B. Ford contracted with the company to perform for children in his home during March 1931. At that time, the always entrepreneurial Mabley recommended his and Duncan’s product, Master Marionettes, as “unusual gift favors” for the children attending that show.

Master Marionettes: Professional Puppets for Amateur Puppeteers, 1930-1940 / THF623904

Tatterman Marionettes’ reputation grew through work with the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago in 1934, where the company presented 1,300 plays. More World’s Fair performances followed. A.B. Dick Company and General Electric both contracted with Tatterman to produce marionette performances during the 1939 World’s Fair. General Electric’s Mrs. Cinderella promoted electrification as part of the modernization of Cinderella’s drafty old castle. (Libby, McNeill & Libby also featured marionette performances, and other corporations staged puppet shows.)

The A.B. Dick Company spared no expense to ensure a first-class production. Tatterman provided the marionettes and experienced operators, while industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague (1883–1960) prepared blueprints for a detailed stage set. Teague’s exhibit work for A.B. Dick and several corporations during the 1939 World’s Fair helped solidify his reputation as “Dean of Industrial Design.” The company invested in a conductor’s score by Tom Bennett (1906–1970), who would go on to join NBC Radio as staff arranger and musical director after the World’s Fair.

With the script finalized (February 27, 1939), experienced operators put the marionettes to work. After the World’s Fair opened on April 30, 1939, they delivered programs on a set schedule published in official daily programs. On Sunday, October 22, 1939, for example, Tatterman Marionettes performed 15 shows—at 10:20, 11:00, and 11:40 in the morning; at 12:20, 1:00, 1:40, 2:20, 3:00, 3:40 in the afternoon; and at 5:40, 6:20, 7:00, 7:20, 8:00, and 8:20 in the evening.

“Brighten Up Your Days,” Song for the Writer’s Cramp Marionette Show, New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623906

At the end of each Writer’s Cramp performance, A.B. Dick mass-produced the feature tune using a mimeograph machine and photochemical stencil. Attendants distributed this sheet music, calling attention to the modern conveniences: “Just a moment, PLEASE! The young lady right behind you is running off some of the words and music from our show—they’re for you to take home with our compliments. Don’t go away without your copy!”

The Tatterman marionettes from Writer’s Cramp featured prominently in World’s Fair promotional material intended to draw the attention of office outfitters to the Business Systems and Insurance Building. Their little stage set conveyed big lessons to the hundreds of thousands of professionals who flowed through the A.B. Dick exhibit at the New York World’s Fair.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Thanks to Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, for editorial guidance.

New York, 20th century, 1930s, world's fairs, popular culture, music, design, communication, by Debra A. Reid, advertising

The Rainbow Connection

Sheet music for “The Rainbow Connection,” 1979 / THF182956

How do the Muppets retain their appeal after all these years? Yes, they’re silly. And entertaining. And very clever. But I would argue that part of their enduring—and endearing—quality is that it doesn’t take much to imagine that they are real. Sure, you can see the materials they’re made out of. And occasionally catch a glimpse of the rods that make their arms move. But sometimes—when they talk like us, act like us, even think like us—we can suspend disbelief for a moment and believe in the magic. Nowhere is this feeling stronger than in the opening scene of the 1979 film, The Muppet Movie, in which Kermit the Frog sits alone on a log in the middle of the swamp, plucks his banjo, and wistfully sings “The Rainbow Connection.”

The Muppet Movie (1979) was the Muppets’ first foray into feature films. Muppet characters had already been known for more than two decades. The particular Muppets who starred in The Muppet Movie had become familiar to us through The Muppet Show, the breakout television series that ran from 1976 to 1981. But, unlike the rapidly changing vaudeville show format of the TV series, the full-length feature film needed a plot, character development, and several songs to keep the story moving. That’s where The Rainbow Connection came in. Through this song, we find out that Kermit—The Muppet Show’s “straight man” around whom all the mayhem and the other characters’ antics revolve—has hopes and dreams of his own. This was something new, something deeper, something more serious and spiritual than we had seen from a Muppet before.

Continue Reading

20th century, 1970s, popular culture, music, Muppets, movies, Jim Henson, by Donna R. Braden