Posts Tagged music

Fozzie Bear’s 1951 Studebaker Commander

The Henry Ford’s 1951 Studebaker Champion, a cousin to Fozzie Bear’s 1951 Commander. / THF90649

Cars and movies go together like peanut butter and jelly, or cake and ice cream. It’s only natural. The two industries appeared almost simultaneously around the turn of the 20th century. Southern California became a major center of American automobile culture and, of course, the center of the U.S. film industry. Over time, certain movies even came to define certain marques. Aston Martin had Goldfinger, DeLorean had Back to the Future, and Studebaker had… The Muppet Movie.

For those who haven’t seen The Muppet Movie, which brought Jim Henson’s creations to the big screen, for the first time, in 1979, stop reading and go watch it right now. Seriously. I’ll wait.

But if a summary has to suffice, then I’ll tell you that The Muppet Movie is in the tradition of the Bing Crosby-Bob Hope “Road” movies, where a simple trip turns into a series of misadventures. But instead of Bing and Bob, you get Kermit the Frog and Fozzie Bear. (Well, you get Bob too, but I digress.) The movie follows Kermit as he makes his way from the Florida swamps to the bright lights of Hollywood, chasing his dream to “make millions of people happy” in show business. Along the way he meets Fozzie, the Great Gonzo, Miss Piggy, and all the usual Muppet favorites.

Paul Williams, seen on a 1980 visit to The Henry Ford, co-wrote The Muppet Movie’s songs. He’d previously penned hits for Three Dog Night, the Carpenters, and Barbra Streisand. / THF128260

Kermit begins his journey on a bicycle, but, after meeting Fozzie Bear, the two continue the trip in Fozzie’s uncle’s 1951 Studebaker Commander. The Stude doesn’t make it all the way to Hollywood—they trade it in for a 1946 Ford station wagon partway through—but it features in two of the movie’s memorable musical numbers: “Movin’ Right Along” and “Can You Picture That?,” both co-written by Paul Williams and Kenny Ascher.

The Muppet Movie is more than great songs and story. The film set new standards in puppetry by convincingly putting its characters into “real world” settings. Prior to Henson’s work, puppets were largely stationary figures, stuck behind props that hid puppeteers from view. Even early Muppet projects, notably The Muppet Show, suffered from this limitation. But in The Muppet Movie, Kermit rides a bicycle, Gonzo floats through the sky below a bunch of balloons, and Fozzie, of course, drives his Commander.

The Studebaker’s “bullet nose” served a practical purpose for the filmmakers. / THF90652

In a way, these elaborate special effects were responsible for the Studebaker appearing in the film. The 1951 Commander’s most distinctive feature is the chrome “bullet nose” between its headlights. The special-effects Commander used in The Muppet Movie had its bullet removed and replaced with a small video camera. The car’s trunk was fitted with a TV screen connected to the camera, a steering wheel, throttle and brake controls, and a seat. With these modifications, a small person was able to operate the car, hidden from view and able to see the road ahead via the camera. With Fozzie placed in the driver’s seat; his puppeteer, Frank Oz, hidden under the dashboard; and the car’s operator concealed in the trunk, it appeared as though the comic bear himself was driving the Studebaker in several scenes. The trick worked so well that, more than 40 years later in the age of computer-generated special effects, Fozzie’s driving is still remarkably convincing. The crew used a second, unmodified Commander for shots where driving effects weren’t needed.

Practical concerns weren’t the only reasons a Commander was used in the movie. In comments published in Turning Wheels, the newsletter of the Studebaker Drivers Club, The Muppet Movie screenwriter Jerry Juhl described the ’51 Commander as perhaps the “goofiest” looking car ever put into production. Goofiness, Juhl added, was a highly-respected quality in the Henson organization, so it seemed only fitting that Fozzie should drive that particular car.

Studebaker’s bullet nose was part of a long, productive relationship between the automaker and industrial designer Raymond Loewy. / THF144005

That bullet nose is a story unto itself. Credit for the feature goes to designer Bob Bourke, working for Studebaker contractor Raymond Loewy Associates at the time. As Bourke later recalled, Loewy told him to model the car’s appearance after an airplane. Bourke responded with the bullet, more properly described as a propeller or a spinner, since it’s a direct reference to that crucial aviation device. And a divisive device it was. People either loved the Studebaker bullet nose or they hated it (and so it goes today).

It’s worth noting that the feature wasn’t without precedent. Ford had used a similar device on its groundbreaking 1949 models. (In fact, Bob Bourke later said that he had contributed informally to the design of the 1949 Ford. You can read Bourke’s reminiscences here.) Studebaker used the bullet nose for just two model years, 1950 and 1951, but it remains one of the company’s most memorable designs.

Studebaker emphasized the aviation influence on the bullet nose design in this 1950 advertisement. / THF100021

The Henry Ford’s collections include a Maui Blue 1951 Studebaker Champion coupe. The lower-priced Champion featured a six-cylinder engine, while the Commander came with a standard V-8. Other than their different badges, the look of the two models is nearly identical. But if you’d like to see the actual car that Fozzie and Kermit used in The Muppet Movie, then head over to South Bend, Indiana. The effects car survives in the collections of (where else) the Studebaker National Museum. It still wears the psychedelic paint scheme applied by Dr. Teeth and the Electric Mayhem in a clever plot device—faded with age, but unmistakable.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Women in the War Effort Workforce During WWII

- Mimi Vandermolen and the 1986 Ford Taurus

- 1956 Continental Mark II Sedan: “The Excitement of Being Conservative”

- 2002 Toyota Prius Sedan: An Old Idea Is New Again

1970s, 20th century, 1950s, popular culture, music, Muppets, movies, Jim Henson, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, design, cars, by Matt Anderson

Women Design: Ray Eames’ Choral Robes

Imagine attending a choral concert in a century-old church. Instead of monochromatic robes, the choristers emerge in bright, radiant color with bold geometric design. The colors of the robes are a musical key, made visual—yellow for the soprano, orange for the contralto, red for the tenor, and purple for the bass. As the choristers sing and sway, the robes come alive, a modern counterpoint to the traditional church interior.

Imagination aside, this is a scene familiar to those who have watched the Hope College Chapel Choir perform. Originally a creation of Charles and Ray Eames from the 1950s, faithful replicas of the robes continue to be used.

The Hope College Chapel Choir at Dimnent Chapel, circa 2001. Photo Courtesy of the Joint Archives of Holland.

Although husband-and-wife design team Charles and Ray Eames collaborated in nearly everything, it was Ray who showed an early and enduring interest in textiles and fashion design. The daughter of a theatre aficionado and manager, she attended the Bennett School for Girls, a two-year college in Millbrook, New York, earning a degree in Fashion Design in 1933. She completed fashion sketches throughout her life—even creating original paper dolls with custom clothing, complete with the tabs used to affix the clothing onto the doll! She designed a few textiles (one of which—“Crosspatch”—won an honorable mention in a 1946 Museum of Modern Art competition) and dedicated significant energy into the design and creation of her own clothing. The clothes she designed for herself and for Charles are quintessential Eames—functional yet beautiful, with playful delights to be found in the details.

D.J. De Pree, the founder and president of the Herman Miller Furniture Company (which produced Charles and Ray Eames’ furniture), was known for his religious fervor. Further, the company is headquartered in Zeeland, Michigan, a Dutch-American enclave with deep Protestant Christian roots. So, when an employee suggested the creation of a company-sponsored chorus in 1952 (something that might otherwise have been an unusual corporate activity), the De Prees granted it legitimacy, naming it the Herman Miller Mixed Chorus and inviting the chorus to perform at company and company-sponsored events. They soon required choral robes to outfit the company chorus and asked Charles and Ray Eames to design them.

Herman Miller Mixed Chorus Soprano and Contralto Vocalist Choir Robes, 1953-1960 / THF75585, THF75580

With Ray’s background, it is likely that she was primarily responsible for the design, although as always in collaboration with her husband. The robes are bold and colorful and make a statement, but they are also functional. Their symbolism is evidence of the Eames’ signature research-heavy process and attention to detail. The colors of the robes identify the vocal type (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) and each color’s hue (from light to dark) corresponds with the vocal range (from high to low). The horizontal black lines at the center of each robe reference the musical staff. Charles and Ray may have scoured the extensive Eames Office reference library to ensure symbolic depth and accuracy. Or, perhaps, this came from an ingrained knowledge of music. They enjoyed a variety of musical types, like jazz, folk, and classical, and music was a major component of the films they produced throughout their life, often collaborating with talented composers like Elmer Bernstein. The theatrical backdrop of Ray’s childhood, her interest in textiles and fashion, and the Eames’ interest in music coalesce in these robes.

Herman Miller Mixed Chorus Tenor and Bass Vocalist Choir Robes, 1953-1960 / THF75574, THF75569

The robes were designed at the Eames Office in Los Angeles, but it is unknown whether the robes were created there and shipped, finished, to Zeeland, or if the patterns and fabric were shipped and the robes were then sewn locally.

By 1960, the Herman Miller Mixed Chorus was disbanded, and Hugh De Pree, son of D.J. De Pree, donated the robes to the Hope College Chapel Choir in the neighboring city of Holland, Michigan, where the family had deep connections. The Hope College Chapel Choir was larger than the Herman Miller Mixed Chorus, so more robes had to be made. Doris Schrotenboer and Millie Grinwis, a mother and daughter team from Zeeland, made the extra. Millie Grinwis recalls that the fabric and patterns were shipped from the Eames Office to her mother’s home, where they were painstakingly put together.

After over 44 years in use, the original robes were retired in 2004. Unwilling, however, to part with the signature design, Hope College commissioned replicas, albeit in a slightly lighter fabric. The original robes were donated to several institutions. At The Henry Ford, these robes add an extra dimension to our design collections, as well as another way to better understand the many talents of Charles and Ray Eames.

The Hope College Chapel Choir recording at Milwaukee’s WTMJ-TV, circa 1965. / Photo Courtesy of the Joint Archives of Holland.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. She is also an alumnus of Hope College, where she was first delighted by these robes! Thank you to Geoffrey Reynolds at the Joint Archives of Holland for graciously sharing pictures of the Hope College Chapel Choir through the years.

20th century, 1950s, women's history, music, Michigan, Herman Miller, fashion, Eames, design, by Katherine White

Kalamazoo, Michigan, is known for its industry. For a relatively small midwestern city, it became a leader in the production of an impressive number of products, some more readily remembered today than others—including celery, paper, stoves, taxicabs, guitars, craft beer, and pharmaceuticals. At the turn of the 20th century, the Kalamazoo Corset Company gave the city more reasons to be noticed—for its high output of corsets, the advertising used to sell them, and for an historic labor strike, led primarily by women.

The Kalamazoo Corset Company began as the Featherbone Corset Company. The company’s name changed in 1894, a few years after the company was relocated 70+ miles from Three Oaks, Michigan, to the city of Kalamazoo. As the original name suggests, the company prided itself on its innovative use of turkey wing feathers—“featherbone”—which replaced the occasionally malodorous whalebone corsets (while these corsets were referred to as containing “whalebone,” it was actually whale baleen that was used, which is not bone).

While the company featured numerous lines of corsets, by 1908, they were focusing on advertising for their “American Beauty” line. These corsets were named to reflect a version of an idealized American woman—an “American Beauty.” Charles Dana Gibson had created his version of the feminine ideal of physical attractiveness, the “Gibson Girl,” during the 1890s—this “American Beauty” followed in her footsteps. The company’s use of “American Beauty” also likely referenced a deep crimson hybrid rose bred in Europe in 1875, which by the turn of the 20th century was popularized in America as the rather expensive American Beauty Rose. By associating their corset line with both the concept of the quintessential American girl and the coveted American Beauty Rose, they were sending a message to the consumer—"buy our corset and you too will take on these qualities!”

Kalamazoo Corset Company "American Beauty Style 626" Corsets, 1891-1922 / THF185765

Promotional songs that advertised a product were becoming increasingly popular at the time. Since the end of the Civil War, Americans had been purchasing parlor pianos for their homes in great numbers—as many as 25,000 per year. The parlor piano became the center of most Americans’ musical experience. Music publishers, like those in the famous Tin Pan Alley of New York City, took note and sold sheet music aimed at these amateur musicians. The rise of music publishing led to a new mode of advertising for retailers and manufacturers. How better to promote your product than by creating a tune that consumers could play in their homes? It seems the Kalamazoo Corset Company agreed, hiring Harry H. Zickel and the Zickel Bros. to write three such songs to advertise the “American Beauty” line: the “American Beauty March and Two-Step” (1908), “My American Beauty Rose: Ballad” (1910), and “My American Beauty Girl” (1912).

My American Beauty Rose: Ballad, 1910 / THF621565

Around the time these songs were being written, issues at the company began to come to light. The company was a major employer in the area, employing 1026 people, 835 of whom were women, in 1911. This made the company the largest employer of women in Kalamazoo. First in 1911, and then again in 1912, around 800 mostly female workers went on strike. They formed the Kalamazoo Corset Workers’ Union, Local 82 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), and protested unequal wages, unsanitary working conditions, and sexual harassment.

The strike gained national attention and the ILGWU headquarters in New York City sent well-known women’s rights advocates Josephine Casey and Pauline Newman to Kalamazoo to assist in the negotiations. The strike looked to New York as an example—the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and subsequent “Uprising of the 20,000” strike of 1909–1910 had sparked more uprisings, some far from New York City, as in Kalamazoo’s example.

The Story of the I.L.G.W.U., 1935 / THF121022

The protesters received support from local unions, but the owner of the company, James Hatfield, was a prominent Kalamazoo businessman and was well-liked among his upper-class peers. Local women’s organizations did not come to the aid of the protestors. Even the local group of suffragettes did not openly support the strike, possibly due to class issues (the suffragettes were upper class, while the women protesting were working class) or because their focus was on getting a women’s suffrage amendment to the state’s constitution passed. The women of the Kalamazoo Corset Company faced an uphill battle to obtain even a semblance of equality in the workplace.

The strike ended on June 15, 1912, ultimately unsuccessful. While an agreement was reached which addressed many of Local 82’s demands, no measures were put in place to ensure adherence, and the company quickly lapsed in its promises. Within just a few years, James Hatfield left the company to begin another, and the company was renamed Grace Corset Company. Between the financial woes wrought by the strike and changing fashions, difficult days for the company were ahead.

The Kalamazoo Corset Company’s business was women—manufacturing garments for women, shaping idealized notions of women—but it was still unable to adequately value the many women it employed by creating an equitable and safe workplace. In the end, the inability of the company to recognize the value of the gender by which they made their business helped to ensure its downfall.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 19th century, women's history, music, Michigan, manufacturing, labor relations, fashion, by Katherine White

Ford Motor Company Radio and TV Programs

The Henry Ford’s archives contain a great deal of material about radio and television shows produced or sponsored by Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company. Here is just a small sampling of the types of items and shows covered.

Henry Ford began broadcasting over his WWI radio station in 1922. Early broadcasts featured musical acts from company bands, such as the Ford Motor Company Band and the Ford Hungarian Gypsy Orchestra. Later broadcasts expanded the talent pool to acts across the United States, including singers, bands, soloists, and even the California Bird Man.

Ford Motor Company Radio Station WWI, Dearborn, Michigan, February 1924. / THF134739

The Ford Sunday Evening Hour was a popular radio show produced by Ford. This show was broadcast from 1934–1942 (and then again from 1945–1946). The show was performed live in Detroit, first at Orchestra Hall and then at the Masonic Temple, and broadcast over the CBS radio network. Musical pieces were played by 75 members of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under the name the Ford Symphony Orchestra, with each show featuring guest star soloists and singers.

Ford Sunday Evening Hour program, October 7, 1934. / THF137776

Ford Sunday Evening Hour Dealer Display, 1938. The program was broadcast across the U.S. and was advertised by Ford dealers all over the country. / THF269154

In the summer, the Ford Summer Hour offered lighter, more popular tunes. This program used a smaller 32-piece orchestra and sometimes featured Ford employee bands such as the River Rouge Ramblers and the Champion Pipe Band.

The Ford Summer Hour poster, 1939. / THF111542

Ford Summer Hour program, August 24, 1941. / THF134690

Ford Motor Company sponsored their share of television programs in the 1940s and 1950s as well. The Lincoln-Mercury division sponsored Toast of the Town, later The Ed Sullivan Show. The archives holds this scrapbook of reviews of the first season of the show (or shew) in 1948.

Toast of the Town scrapbook, 1948-1949. / THF622224, THF622504

The 50th anniversary of Ford Motor Company in 1953 was a big celebration. Paintings were commissioned by Norman Rockwell to depict the company history, calendars were assembled, banquets and celebrations were planned worldwide, and the company put together a TV special to celebrate its 50-year history.

Advertisement, "Ford 50th Anniversary Show," June 15, 1953 / THF622247

The TV program featured many well-known performers, many of whom signed Benson Ford’s personal copy of the script.

Script for the Ford Motor Company 50th Anniversary TV Show, Broadcast June 15, 1953 / THF622239, THF622240

These are only a few of the radio and TV shows produced or sponsored by Ford over the years. The archive at the Benson Ford Research Center has additional material, including scripts, ratings, and public relations analysis reports, for several of these shows. Some of these items may be viewed in our Digital Collections, while others have yet to be digitized. While the reading room at the Benson Ford Research Center remains closed at present for research, if you have any questions, please feel free to email us at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Kathy Makas is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford. This post is based on a February 2021 presentation of History Outside the Box as a story on The Henry Ford’s Instagram channel.

Dearborn, Michigan, Detroit, archives, TV, music, radio, Ford Motor Company, by Kathy Makas, History Outside the Box

An Artifact Love Story, Featuring the Wizard of Oz

My name is Shannon Rossi, and I’m a Collections Specialist, Cataloger, for archival items. I started at The Henry Ford as a Simmons Intern in 2018, and have been a Collections Specialist since March 2019. Anyone who knows me knows that I love The Wizard of Oz. It is my favorite film. I collect Oz memorabilia and am a member of The International Wizard of Oz Club.

The artifact I’m going to talk about here is related to The Wizard of Oz. But it’s not the artifact you might expect.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, first edition, 1900 / THF135495

On my second day as a Simmons intern in 2018, Sarah Andrus, Librarian at The Henry Ford, showed me a beautiful first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. The little girl who used to dance around the house singing “We’re Off to See the Wizard” rejoiced when I was able to hold that book in my hands. In my own collection of Oz memorabilia, I have a 1939 edition, but this was another experience entirely.

Last year marked the 80th anniversary of the 1939 musical starring Judy Garland. I signed up to do a History Outside the Box presentation to commemorate the anniversary. History Outside the Box allows us to showcase some of our archival items that visitors to The Henry Ford might not otherwise get a chance to see. In addition to the first edition book, I knew we had some fantastic Oz artifacts in our collection. We have copies of the special edition TV Guides that came out in July 2000, each with one of the main characters on the cover. We have sheet music for “We’re Off to See the Wizard” and “Over the Rainbow,” a coloring book from the 1950s, an original 1939 advertisement for the film an issue of Life magazine, and a photograph of Bert Lahr (the Cowardly Lion) when he visited Greenfield Village in the 1960s.

Bert Lahr Signing Autographs during a Visit to Greenfield Village, August 22, 1966 / THF128032

The artifact I want to talk about isn’t as famous or recognizable as anything I listed above. You pretty much have to be a diehard Oz fan (or have worked on acquiring, cataloging, or digitizing this item—which I did not) to even associate much meaning with it.

While browsing our collections for archival items to use in my History Outside the Box presentation, I found a theater program from the 1903 musical production of The Wizard of Oz at the Boston Theatre. (Be honest, how many of you knew that the 1939 film wasn’t the first musical production of Oz?)

Theater Program, "The Wizard of Oz," Boston Theatre, Boston, Massachusetts, 1903 / THF93092

We’ve established that I am a huge Oz fan. I knew about this production, as well as several of the early film productions (check them out if you get a chance!), but I had never seen a program from the show. This program is not visually spectacular. It is black and white. The vivid colors and magical illustrations from W.W. Denslow that are featured in the Oz first edition are conspicuously absent. In fact, the only illustration that anyone might associate with Oz is on the cover, which features a beautiful illustration of the Cowardly Lion about to fall asleep among a field of poppies that create a border around the page.

The story and lyrics for this musical adaptation was written by L. Frank Baum, but not all of it would seem familiar. We’d see, of course, Dorothy, the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and the Wizard. The Cowardly Lion, however, cannot speak, as he does in the book and almost every later adaption, nor does he ever befriend Dorothy. Dorothy’s house doesn’t land on any Wicked Witch. Nor does she receive any magical slippers (silver, as in the book, or ruby, as in the movie). Even our favorite precocious Cairn Terrier, Toto, is missing from this story. Toto is replaced by a cow named Imogene, who serves as Dorothy’s Kansas companion.

The cast list for Act I in the program includes Dorothy Gale and “Dorothy’s playmate,” the cow Imogene. / THF141760

The action in Oz has to do with political tensions between the Wizard and Pastoria, the King of Oz (who does appear in later Oz books). In fact, even real-life politicians and notable members of society at the time, including Theodore Roosevelt and John D. Rockefeller, were mentioned in the script.

The Boston Theatre production that audiences saw in November 1903 featured songs by composer Paul Tietjens, who had approached L. Frank Baum about creating an Oz musical as early as March 1901. Tietjens wasn’t exactly famous, but the play did feature some well-known actors of the early 20th century.

Most importantly, there are two names in the program that stand out: Fred Stone and David Montgomery. The two actors were paired on stage in many vaudeville shows. The pair played the Scarecrow and Tin Man in this musical adaptation. Later, when Ray Bolger was cast as the Scarecrow in the 1939 musical, he would credit Stone with inspiring his “boneless” style of dance and movement as the character.

Page seven of the program lists actors Fred A. Stone as the Scarecrow and David C. Montgomery as the Tin Woodman / THF141761

I’m grateful that this artifact was digitized. It’s not something you see or hear about very often, but it has a lot of power for Oz fans like me. That’s the power of digitization—the impact of a digitized artifact doesn’t have to reach huge audiences, if it reaches a smaller but enthusiastic audience. Digitization can allow us to marvel (slight pun about Professor Marvel in the 1939 musical definitely intended…) at an object we know exists somewhere out in the world, but have never seen before.

Continue Reading

Massachusetts, music, 20th century, 1900s, popular culture, digitization, digital collections, by Shannon Rossi, books, archives, actors and acting, #digitization100K

The Jazz Bowl: Emblem of a City, Icon of an Age

The Jazz Bowl, originally called The New Yorker, about 1930. THF88363

Cowan Pottery of Rocky River, Ohio, was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy in early 1930 when a commission arrived from a New York gallery for a New York City-themed punch bowl. The client -- who preferred to remain unknown -- wanted the design to capture the essence of the vibrant city.

The assignment went to 24-year-old ceramic artist Viktor Schreckengost. His design would become an icon of America’s “Jazz Age” of the 1920s and 1930s.

The Artist and His Design

The cosmopolitan Viktor Schreckengost was a perfect choice for this special commission. Schreckengost (1906-2008), born in Sebring, Ohio, had studied ceramics at the Cleveland Institute of Art in the late 1920s. He then spent a year in Vienna, where he was introduced to cutting-edge ideas in European art and design. When Schreckengost returned to Ohio, he took a part-time teaching position at his alma mater and spent the balance of his time as a designer at Cowan Pottery.

A jazz musician as well as an artist, Schreckengost had firsthand knowledge of New York, where he frequented jazz clubs during visits. To Schreckengost, jazz music represented the spirit of New York. He wanted to capture its excitement and energy in visual form on his bowl. Schreckengost later recalled: “I thought back to a magical night when a friend and I went to see [Cab] Calloway at the Cotton Club [in Harlem] ... the city, the jazz, the Cotton Club, everything ... I knew I had to get it all on the bowl.”

During its heyday in the 1920s and 30s, the Cotton Club was the place to listen to jazz in New York. THF125266

A “Jazz”-inscribed drumhead surrounded by musical instruments symbolize the Cotton Club. Organ pipes represent the grand theater organs that graced New York City’s movie palaces during the 1920s and 1930s. Schreckengost recalled that he was especially fond of Radio City Music Hall’s Wurlitzer organ. THF88363

A show in progress at Radio City Music Hall auditorium, 1936. THF125259

The images on the Jazz Bowl, then, may be read as a night on the town in New York City, starting out in bustling Times Square; then on to Radio City Music Hall to enjoy a show; next, a stroll uptown past a group of soaring skyscrapers to take in a sweeping view of the Hudson River; afterward, a stop at a cocktail party; and finally--topping off the evening with a visit to the famous Cotton Club.

Times Square, circa 1930. THF125262i

The blinking traffic signals, and "Follies" and "Dance" signs on the Jazz Bowl portray the vitality of Times Square at night. THF88358

Schreckengost decorated the punch bowl with a deep turquoise blue background he described as “Egyptian,” since it recalled the shade found on ancient Egyptian pottery. According to Schreckengost, the penetrating blue immerses the viewer in the glow of the night air--and the sensation of mystery and magic of a night on the town.

This is the view of the New York skyline and the Hudson River that Schreckengost saw on his trips to the city and later interpreted in the Jazz Bowl. THF125264g

Skyscrapers, a luxury ocean liner, cocktails on a tray, and liquor bottles represent a night on the town. THF88364

The Famous Client

In early 1931, the finished bowl was delivered to New York. The pleased patron who had commissioned it immediately ordered two additional punch bowls. To Schreckengost’s delight, the patron turned out to be Eleanor Roosevelt, then First Lady of New York State. Mrs. Roosevelt had commissioned the bowl to celebrate her husband Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1930 reelection as governor. She presumably placed one bowl in the Governor’s Residence in Albany, one in the Roosevelts’ home in Hyde Park, and one in their Manhattan apartment. When the Roosevelts moved into the White House in 1933, after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election as President, one of the bowls made its way there as well.

Eleanor Roosevelt commissioned the Jazz Bowl to celebrate her husband’s 1930 reelection as governor of New York. THF208655

Mass Producing the Jazz Bowl?

Immediately after the Jazz Bowl was delivered to Eleanor Roosevelt, the New York City gallery placed an order for fifty identical bowls. Unfortunately, Schreckengost’s process was laborious--it took Cowan Pottery’s artisans an entire day to produce the incised decoration on Mrs. Roosevelt’s version. Cowan Pottery sought to mass produce the punch bowl, simplifying the original design to create a second and third version the company originally marketed as “The New Yorker.”

The Henry Ford’s bowl is the third version, known informally as “The Poor Man’s Jazz Bowl.” It is slightly smaller than the original and the decoration is raised, rather than scratched into the surface. No one knows exactly, but perhaps fifty of the original version, only a few of the unsuccessful second version, and possibly twenty of the third version of the Jazz Bowl were made in total. The whereabouts of many of the Jazz Bowls are not known, though they appear periodically on the art market and are acquired by eager collectors. Even the present location of the bowls made for Eleanor Roosevelt seems to be a mystery.

Jazz Bowl as Icon

The “Poor Man’s Jazz Bowl” didn’t save the Cowan Pottery from the ravages of the Great Depression -- by the end of 1931, the company folded. Viktor Schreckengost moved on, continuing to teach at the Cleveland Institute of Art and pursuing freelance design for several firms. His Jazz Bowl would come to be recognized as a visual icon of the Jazz Age in America.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series.

New York, 20th century, 1930s, 1920s, presidents, music, manufacturing, making, Henry Ford Museum, furnishings, decorative arts, by Charles Sable, art

Boomboxes at The Henry Ford

An image from the set of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation.

For many people—especially those who grew up between the decades of the 1970s through the 1990s—the sight of a boombox often prompts the thought: “I wonder how heavy that thing would feel, if I carried it around on my shoulder?” Boomboxes are infused with the promise of human interaction, ready for active use—to be slung from arm to arm, hoisted up on a shoulder, or planted with purpose on a park bench or an empty slice of asphalt in a city somewhere.

Here at The Henry Ford, we recently acquired a trio of classic boomboxes to document stories about the growth of mobile media and the social communication of music in American culture.

The Norelco 22RL962 was developed in the mid-1960s by the Dutch company, Philips. A combination radio and compact cassette player, it had recording and playback functions as well as a carrying handle. While it was generally thought of as the first device that could be accurately called a “boombox,” the Norelco failed to gain mass traction. The core issue wasn’t due to poor performance from a technological standpoint, but rather the bad sound quality of the tapes. In 1965, the American engineer Ray Dolby invented the Dolby Noise Reduction system, which led to clean, hiss-free sound on compact cassette tapes. His invention sparked a revolution in hi-fi cassette audio.

The ubiquitous compact cassette tape.

In the early 1970s, Japanese manufacturers began to make advancements in boombox technology as an outgrowth of modular hi-fi stereo components. Living spaces in Japan were typically small, and there was a desire to condense electronics into compact devices without losing sound quality.

Later that decade, the improved boombox made its way to the United States, where it was embraced by hip hop, punk, and new wave musicians and fans—many of whom lived in large cities like New York and Los Angeles. In many ways, the boombox was a protest device, as youth culture used them to broadcast politically charged music in public spaces.

An early image of the Brooklyn Bridge and New York Skyline. THF113708

Boomboxes literally changed the sonic fabric of cities, but this effect was divisive. By the mid-1980s, noise pollution laws began to restrict their use in public. The golden years of the boombox were also short lived due to the rising popularity and affordability of personal portable sound devices like the Sony Walkman (and later, the MP3 player), which turned music into a private, insular experience.

The JVC RC-550 ”El Diablo” boombox. THF179795

JVC RC-550 “El Diablo”

This boombox was built for the street, and it is meant to be played loud. Its design is rugged, with a carrying handle and protective “roll bars” in case it is dropped. Many classic photos from the early years of hip-hop depict fans and musicians carrying the El Diablo around cities and on the subway in New York.

The JVC RC-550 is a member of what sound historians refer to as the “holy trinity” of innovative boomboxes. While the origins of its “El Diablo” nickname are uncertain, it is believed to stem from the impressive volume of sound it can transmit—or its flashing red sound meters. It is a monophonic boombox, meaning that it has one main speaker and it is incapable of reproducing sound in stereo. A massive offset 10-inch woofer dominates its design, coupled with smaller midrange and tweeter speakers. As with most boomboxes of this time, bass and treble levels could be adjusted.

An input for an external microphone led to the RC-550 being advertised as a mobile personal amplifier system. Brochures from the Japanese version show the boombox being used by salesmen to amplify their pitches in front of crowds, as a sound system in a bar, and by a singing woman accompanied by a guitarist. Recording could take place directly through the tape deck, or through the microphone on top, which could be rotated 360-degrees.

JVC 838 Biophonic Boombox. THF177384

JVC 838 Biphonic Boombox

The JVC 838 is important for its transitional design. It was one of the first boomboxes to incorporate the symmetrical arrangement of components that would become standard in 1980s portable stereos: visually balanced speakers, buttons and knobs, and a centered cassette deck.

As boombox designs evolved, they began to include (almost to the point of parody) sound visualization components such as VU meters and other electronic indicators. In many cases, these were purely for visual effect rather than function. The needle VU meters on the JVC 838 however, were accurate.

A unique feature of the JVC 838 boombox is its “BiPhonic” sound—a spatial stereo feature that creates a “being there” effect through its binaural speaker technology, resulting in “three-dimensional depth, spaciousness, and pinpoint imaging.” The box also includes an “expand” effect to widen the sound even further.

Sharp GF-777 “Searcher.” THF177382

Sharp “Searcher” GF-777

The Sharp “Searcher” GF-777 is an exercise in excess. Often referred to as the “king of the boomboxes,” it was also one of the largest ever produced. Weighing thirty pounds (minus ten D-cell batteries) and measuring over one foot tall and two feet wide, it took a certain amount of lifestyle commitment to carry this device around a city.

The Searcher played a key part in the performance and representation of hip-hop music. Its six speakers include four woofers individually tuned for optimal bass transmission and amplitude. It appeared in a photograph on the back cover of the first Run-DMC album, found its way into several music videos, and was photographed alongside breakdancing crews.

Many people used this boombox as an affordable personal recording studio. Two high quality tape decks opened the possibility for people to create “pause tapes” – a way of creating looped beats through queuing, recording, rewinding, and repeating a short phrase of music. A microphone input and an onboard echo effect meant people could rap or sing over top of music backing tracks.

Much like Thomas Edison’s phonograph, the boombox came full circle, allowing people to record and play back music for public and communal consumption. And while they may not mesh with our ideas of what a “mobile” device is in our age of smartphones and streaming services, their reach permeated popular culture in the 1970s well into the 1990s. Sometimes acting as portable sound systems, sometimes used as affordable personal recording studios—carrying a boombox through the streets (wherever you happened to live) was as much a fashion statement and lifestyle choice as it was a celebration of music and social technology.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications and Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

1980s, 1970s, 1960s, 20th century, technology, radio, portability, popular culture, music, communication, by Kristen Gallerneaux

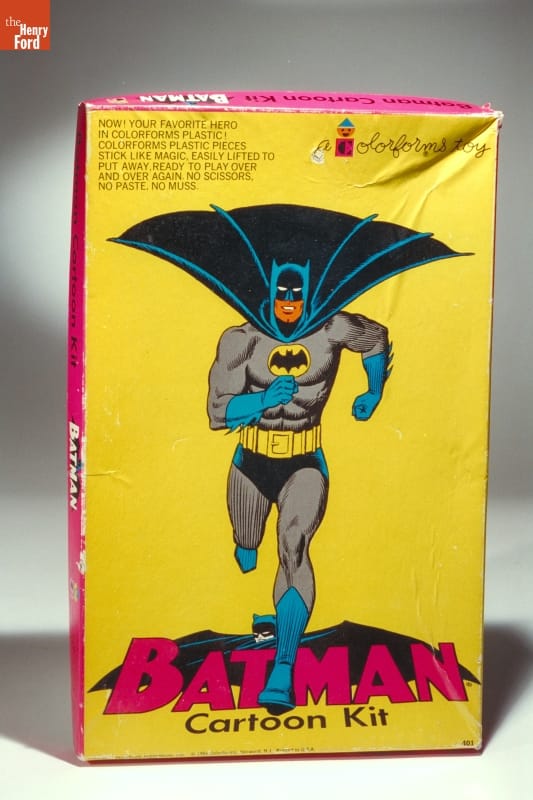

“Batman Cartoon Kit” Colorforms, 1966-68. THF 6651

It was the 1960s—the golden age of television. Some 95% of American homes boasted at least one TV. These were primarily black and white sets, as color TV was still out of the reach of many families. It’s hard to imagine now but there were only three channels at the time. Every year, the three networks (CBS, NBC, and ABC) vied for viewer ratings, shifting and changing shows and showtimes at two pivotal times during the television season—Fall and Winter.

As the Fall 1966 season unfolded, it became evident to TV viewers that something extraordinary was happening. Sure, there were the usual long-running sitcoms, like Green Acres, Petticoat Junction, and The Beverly Hillbillies. But change was in the wind. A new crop of programs emerged—colorful, fast-paced, poking fun at things that were supposed to be serious and exploring contemporary social issues.

Why the difference all of a sudden? Many of these shows were aimed at the youth audience, considered by this time an influential group of TV watchers. Others purposefully took advantage of the new color televisions. Sometimes show producers and creators were simply tired of the old formulas and wanted to break out of the box.

Let’s take a look at a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season—starting with the staid and true and working up to the wild and wacky—and see what all the hubbub was about!

Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Sunday, 7:30-8:30 p.m., NBC)

Snow Globe, “The Wonderful World of Disney,” 1969-79. THF174650

On Sunday nights since 1954, millions of Americans had tuned in to watch Walt Disney host his TV show, with a changing array of animated and live-action features, nature specials, movie reruns, travelogues, programs about science and outer space, and—best of all—updates on Walt Disney’s theme park, Disneyland. Since 1961, this show had been broadcast in color.

The 1966-67 season was particularly memorable because Walt Disney tragically passed away on December 15, 1966. But since the episodes had been pre-recorded, there was Walt still hosting them until April 1967. Viewers found this both comforting and disconcerting. Finally, after April, Walt was dropped as the host and, eventually, the show was retitled The Wonderful World of Disney. It ran with solid ratings until the mid-1970s.

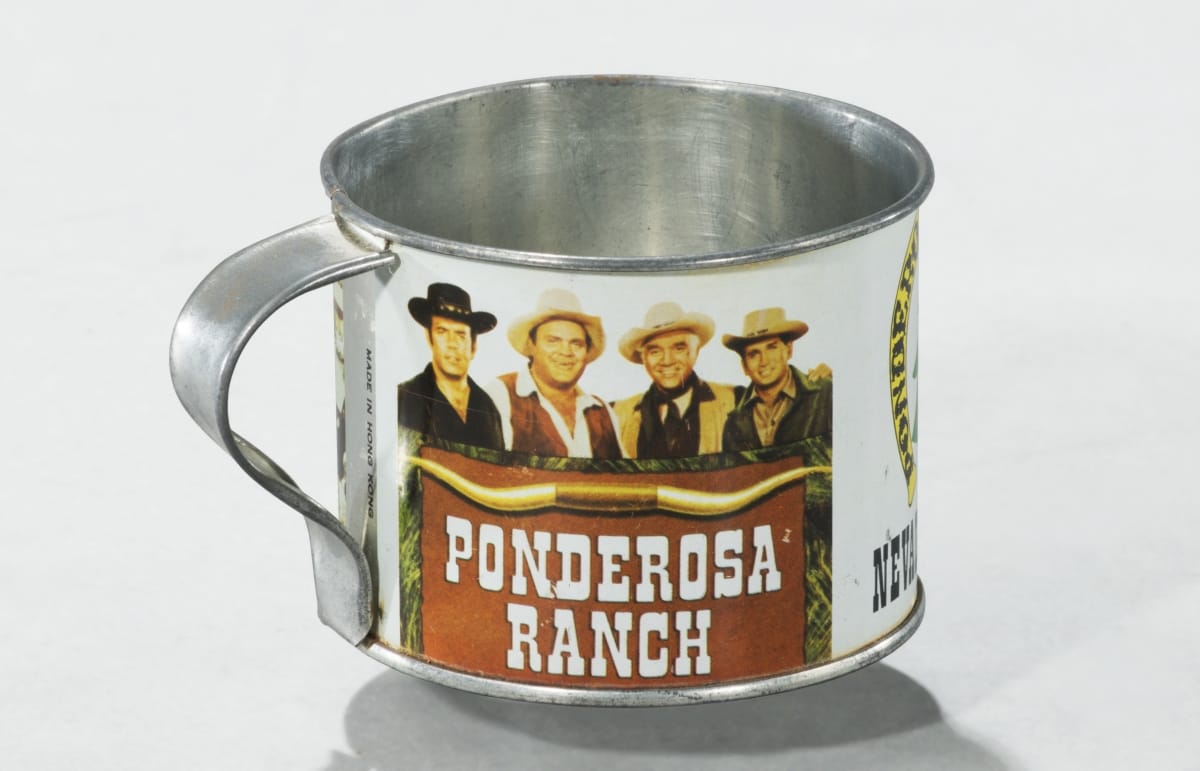

Bonanza (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m., NBC)

“Ponderosa Ranch” Mug, ca. 1970. THF174648

Viewership was high on NBC on Sunday nights at 9:00, as Bonanza was one of the most popular TV shows of all time. Running for 14 seasons and 430 episodes, this series about the trials and tribulations of widower Ben Cartwright and his three sons on the Ponderosa Ranch was an immediate breakout hit when it premiered in 1959, amidst a plethora of more run-of-the-mill prime-time westerns. Its popularity was primarily due to its quirky characters and unconventional stories—including early attempts to confront social issues. It was the first major western to be filmed in color and was the top-rated show on TV from 1964 to 1968. Bonanza ran until 1973.

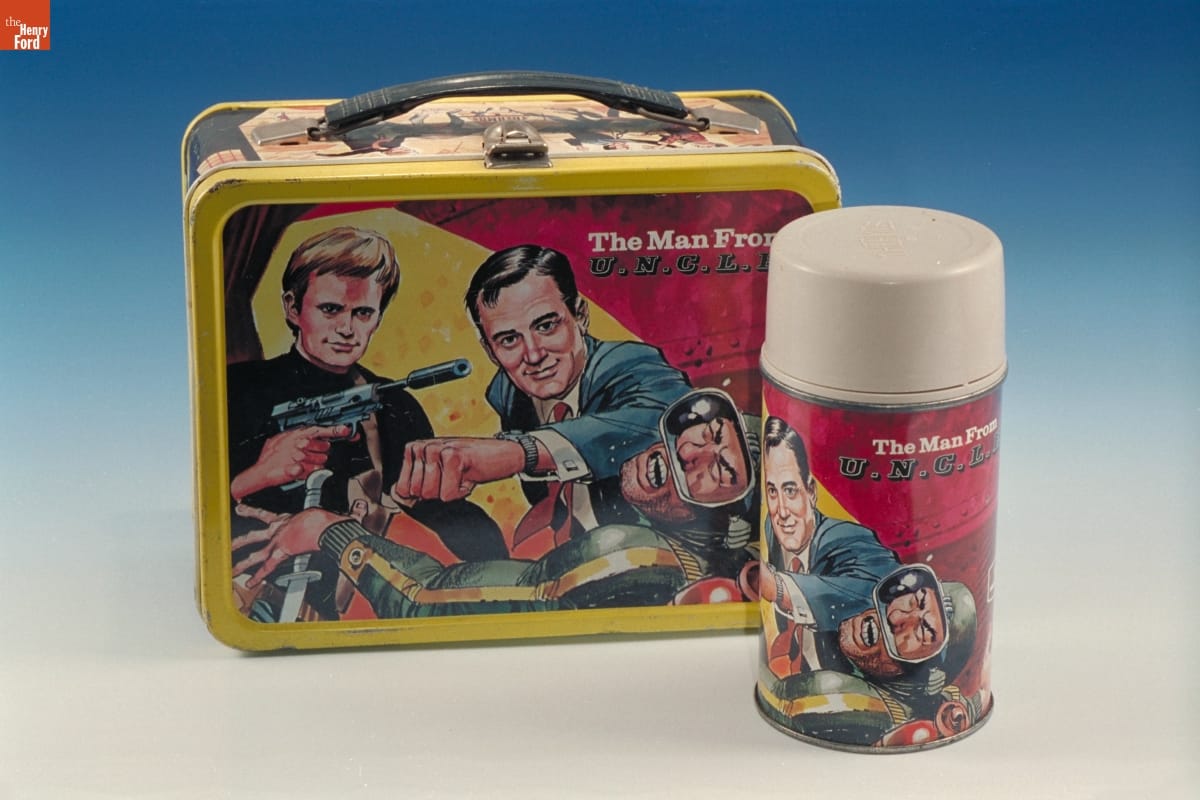

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (Friday, 8:30-9:30, NBC)

“The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” lunchbox and thermos, 1966. THF92303

Premiering in September 1964, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. took full advantage of the popularity of the spy genre launched by the James Bond film series. In fact, early concepts for it were conceptualized by Bond creator Ian Fleming. In this series, Napoleon Solo (originally conceived as the lone star) and Russian agent Ilya Kuryakin (added in response to popular demand) teamed up as part of a secret international counterespionage and law enforcement agency called U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement). Solo and Kuryakin banded together with a global organization of other agents to fight THRUSH, an international organization that aimed to conquer the world.

During this, the Cold War era, it was groundbreaking for a show to portray a United States-Soviet Union pair of secret agents, as these two countries were ideologically at odds most of the time. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was also known for its high-profile guest stars and—taking a cue from the Bond films—its clever gadgets. In 1966, this series won the Golden Globe for Best Television Program and, building upon its popularity, spun off into two related double-feature movies that year. Unfortunately, attempting to compete with lighter, campier programs of the era, the producers made a conscious effort to increase the level of humor—leading to a severe ratings drop. Although the serious plot lines were soon reinstated, the ratings never recovered. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was canceled in January 1968.

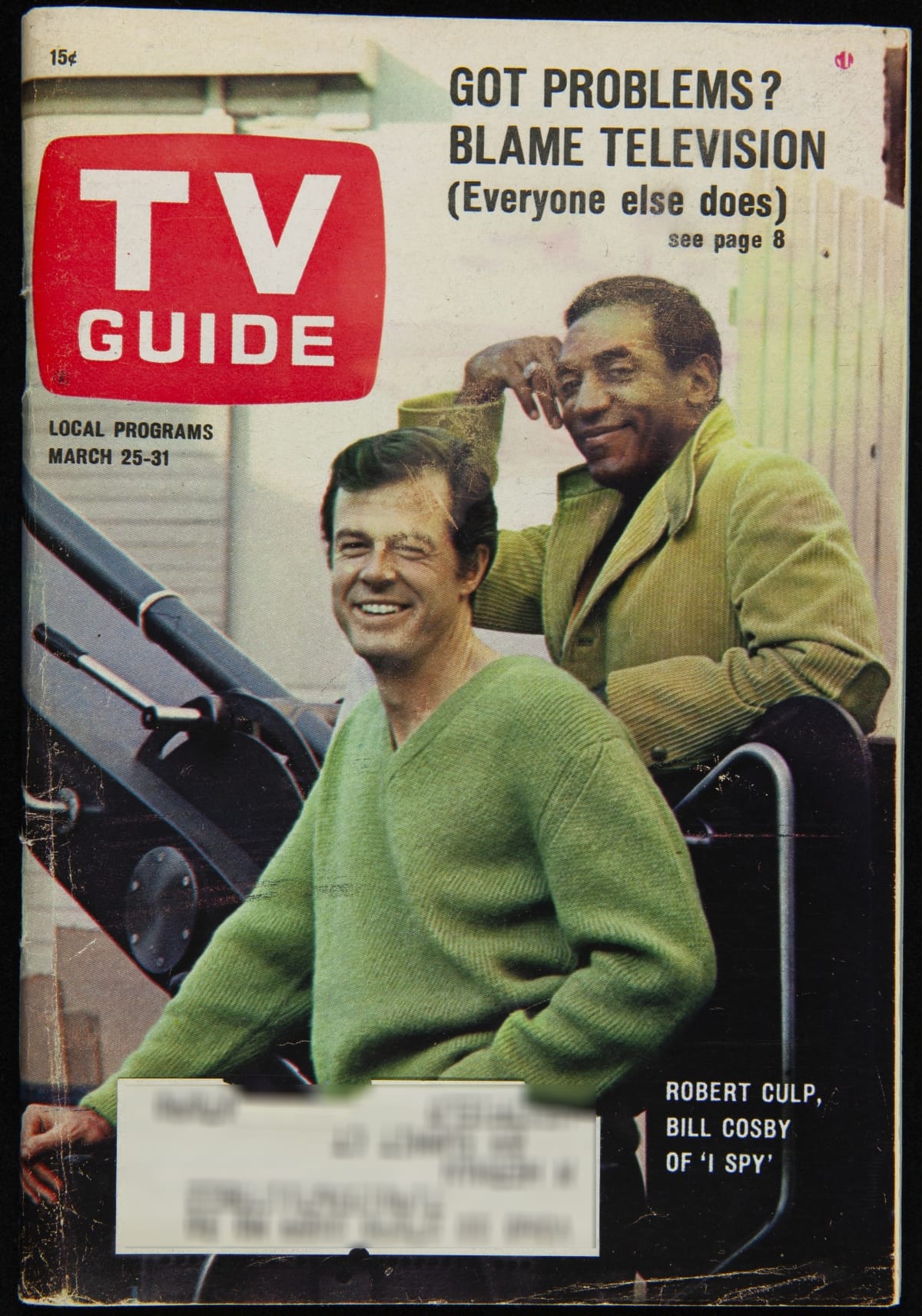

I Spy (Wednesday 10:00-11:00, NBC)

TV Guide featuring “I Spy” characters Robert Culp and Bill Cosby on cover, March 25-31, 1967. THF275655

One series that never opted for campy was I Spy, which starred Bill Cosby and Robert Culp playing two U.S. intelligence agents traveling undercover as international “tennis bums.” This series, which premiered in 1965, was also inspired by the James Bond film series and remained a fixture in the secret agent/espionage genre until cancelled in April 1968. I Spy, additionally a leader in the buddy genre, broke new ground as the first American TV drama series to feature a black actor in a lead role. It was also unusual in its use of exotic locations—much like the James Bond films—when shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. were completely filmed on a studio backlot.

I Spy offered hip banter between the two stars and some humor, but it focused primarily on the grittier side of the espionage business, sometimes even ending on a somber note. The success of this series was attributed to the strong chemistry between Culp and Cosby. Cosby’s presence was never called out in the way that black stars and co-stars were made a big deal of on later TV programs like Julia (1968) and Room 222 (1969).

Get Smart (Saturday, 8:30-9:00 NBC)

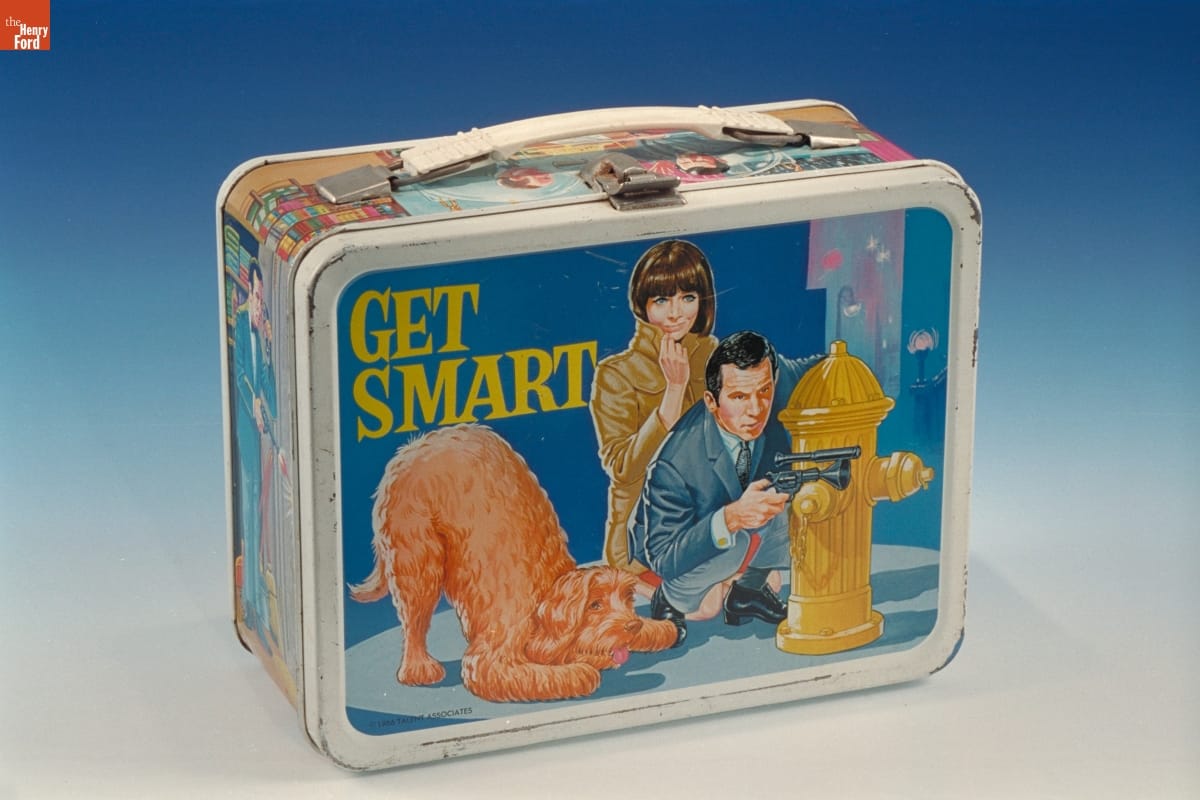

“Get Smart” Lunchbox, 1966. THF92304

Premiering in September 1965, Get Smart was a comedy that satirized virtually everything considered serious and sacred in the James Bond films and such TV shows as I Spy and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Created by comic writers Mel Brooks and Buck Henry as a response to the grim seriousness of the Cold War spy genre, it starred bumbling Secret Agent 86—otherwise known as Maxwell “Max” Smart, along with supporting characters, female Agent 99 and the Chief. These characters worked for CONTROL, a secret U.S. government counterintelligence agency, against KAOS, “an international organization of evil.” Brooks and Henry also poked fun at this genre’s use of high-tech spy gadgets (Max’s shoe phone perhaps being the most memorable), world takeover plots, and enemy agents. Somehow, despite serious mess-ups in every episode, Maxwell Smart always emerged victorious in the end.

Get Smart was considered groundbreaking for broadening the parameters of TV sitcoms but was especially known for catchphrases like “Would you believe…” and “Sorry about that, Chief.” Despite a declining interest in the secret-agent genre, Get Smart’s talented writers attempted to keep it fresh until it was finally cancelled in May 1970.

Batman (Wednesday and Thursday, 7:30-8:00, ABC)

Toy Batmobile, 1966-69. THF174647

Bursting onto the scene in January 1966, Batman became an instant hit and took the country by storm. Batmania was in full swing by the Fall 1966-67 TV season. The series, based upon the DC comic book of the same name, featured the Caped Crusader (millionaire Bruce Wayne in his alter-ego of Batman) and the Boy Wonder (his young ward Dick Grayson in his alter-ego of Robin). These two crime-fighting heroes defended Gotham City from a variety of evil villains. It aired twice weekly, with most stories leaving viewers hanging in suspense the first night until they tuned in the second night.

This show successfully captured the youth audience, with its campy style, upbeat theme music, and tongue-in-cheek humor. Despite the fact that it verged on being a sitcom, the producers wisely left out the laugh track, reinforcing the seriousness with which the characters seemed to take the often absurd and wildly improbable situations in which they found themselves. The filming simulated a surreal comic-book quality, with characters and situations shot at high and low angles, with bright splashy colors and with sound effects, like Pow, Bam, and Zonk, appearing as words splashed across the action sequences on screen. The series was also replete with numerous gadgets and over-the-top props, with the Batmobile undoubtedly most memorable. Batman ran until March 1968, experiencing a significant ratings drop after its initial novelty faded.

Lost in Space (Wednesday 7:30-8:30, CBS)

“Lost in Space” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92298

Loosely based upon the story of the Swiss Family Robinson, this TV series depicted the adventures of the Robinson family, a pioneering family of space colonists who struggled to survive in the depths of space in the futuristic year of 1997—as the United States was gearing up to colonize space due to overpopulation. But the family’s mission was sabotaged, forcing the crew members to crash-land on a strange planet and leaving them lost in space.

The show had premiered in September 1965 as a serious science fiction series about space exploration and a family searching to find a new place for humans to dwell. But, in January 1966, pitted against Batman’s time slot, Lost in Space producers attempted to imitate Batman’s campiness with ever-more-outrageous villains, brightly colored outfits, and over-the-top action. The plots increasingly featured Robby the Robot and the evil Dr. Zachary Smith. Viewers and actors alike strongly disapproved of this shift. The show lingered on until March 1968.

The Monkees (Monday, 7:30-8:00, NBC)

“Monkees” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92313

Where other shows might have been lighthearted, campy, or tongue-in-cheek, The Monkees at times verged on pure anarchy. This series, which premiered on September 12, 1966, led off NBC’s prime-time programming every Monday night. It lasted only two seasons but during that time, its star shone brightly. The Monkees followed the experiences of four young men trying to make a name for themselves as a rock ‘n’ roll band, often finding themselves in strange, even bizarre, circumstances while searching for their big break. Aimed directly at the youth audience, the band members were characterized as heroes down on their luck while the adults were consistently depicted as the “heavies.”

The Beatles’ films A Hard Day’s Night and Help! inspired producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider to create not only a show about a rock ‘n’ roll band but also to adapt a loose narrative structure (each member of the Monkees was trained in improvisational acting techniques at the outset of the show) and the musical sequences or “romps” that appeared each week. The series built a reputation for its innovative use of avant-garde filming techniques like quick jump cuts and breaking the fourth wall (that is, having the characters directly address the TV viewers). A well-oiled marketing machine behind the show also ensured that strong tie-ins were maintained with teen magazines, merchandise, and live concerts.

The Monkees won the Emmy for best comedy series during its first, the 1966-67, season. However, backlash was inevitable among critics and older teenagers when the Monkees admitted that they did not play their own instruments—although they clearly played them in their live concerts and, in fact, eventually had a falling-out with network executives about this very issue. Though the show was cancelled in 1968, it experienced a huge revival among younger audiences through Saturday morning reruns and especially with the 1986 MTV Monkees Marathon. Remaining band members Micky Dolenz and Mike Nesmith still attract large audiences of intergenerational fans at their live concerts, while reruns of their TV shows continue to draw new audiences.

Star Trek (Thursday, 8:30-9:30 NBC)

“Star Trek” lunchbox, 1968. THF92299

When Star Trek premiered on September 8, 1966, science fiction shows were not very advanced—or even thought of very highly. Star Trek’s closest competitor, Lost in Space, offered only shallow plots, one-dimensional characters, and fake sets. No one could imagine at the time that this rather low-key show would become one of the biggest, longest-running, and highest-grossing media franchises of all time. This series traced the interstellar adventures of Captain James T. Kirk and his crew aboard the United Federation of Planets’ starship Enterprise, on a five-year mission “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Creator Gene Roddenberry, aiming the show at the youth audience, wanted to combine suspenseful adventure stories with morality tales reflecting contemporary life and social issues. So, to get by network scrutiny, he set the premise of the show in an imaginary future. With the freedom to experiment, he put in place one of TV’s first multiracial and multicultural casts and was able to explore through different episodes some of the most relevant political and social allegories on TV at the time. The stories were also considered exceptionally high quality for that era, involving believable characters with which viewers could both identify and sympathize. Unlike the gloomy predictions of most science fiction writings of the time, Roddenberry hoped that the futuristic utopia he created on Star Trek would give young people hope, that it would empower them to create a better future for themselves someday. Star Trek, with only modest ratings, lasted only three seasons. But it would go on to become a cult classic.

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m. beginning February 1967, CBS)

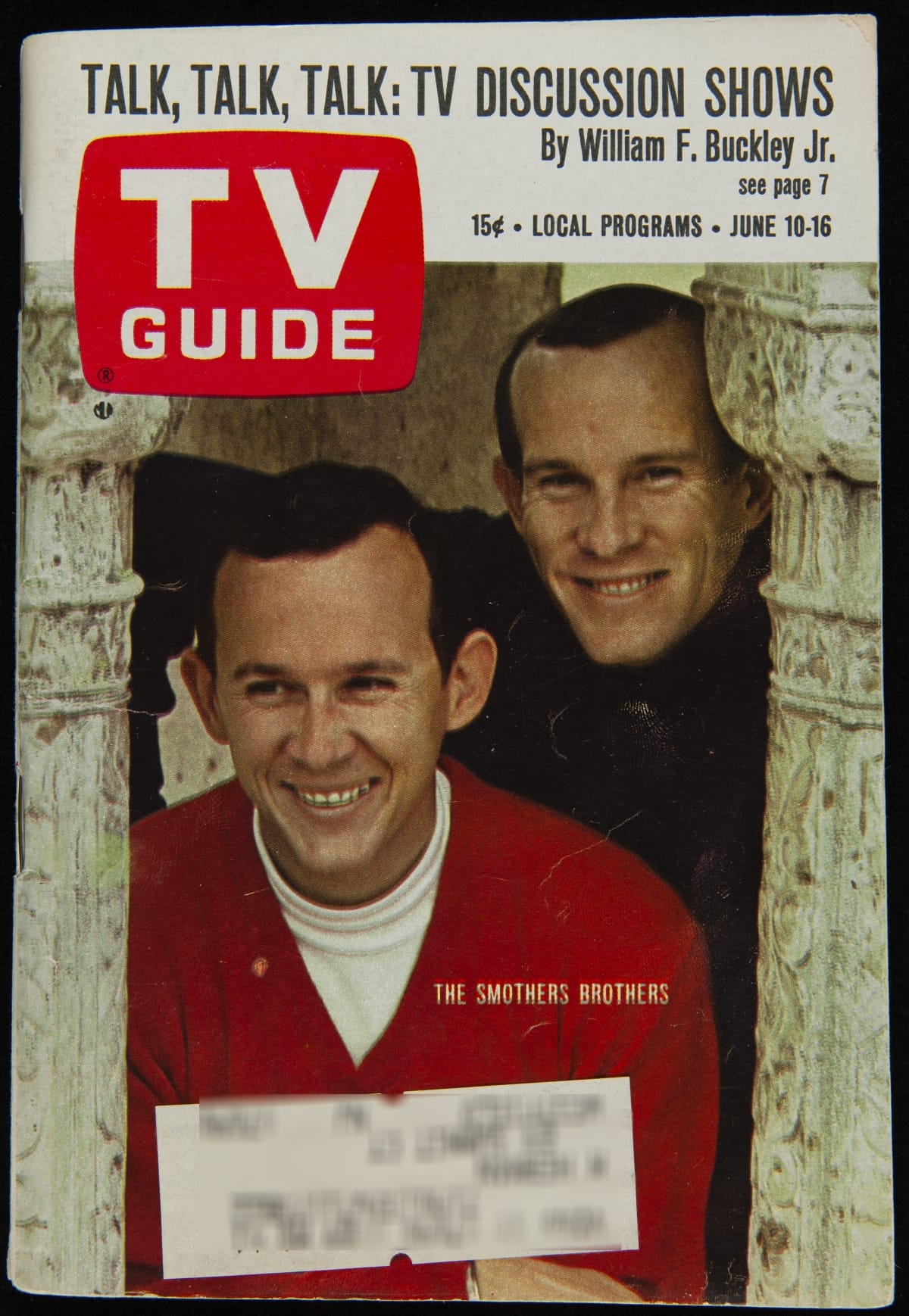

TV Guide featuring The Smothers Brothers on cover, June 10-16, 1967. THF275657

In Fall 1966, The Garry Moore Show, a variety show on CBS hosted by the aging radio and TV star, was no match when pitted against Bonanza—even with this, its first season in color. Network executives, at their wit’s end to try to attract viewership, decided the only way they could come up with a quick replacement was to substitute another variety show. In desperation, they landed on a simple variety series featuring the soft-spoken, clean-cut, non-threatening folk-music-playing Smothers Brothers. Considered a “young act,” an added bonus was that their show might capture the coveted youth audience. Little did they know what they were in for.

As the show evolved, the brothers not only became more politicized themselves but felt that they owed it to their young viewers to increase the show’s relevance, boldly addressing overtly divisive political and social issues. Their staff of young writers was only too happy to comply. Unfortunately, as a result, the brothers were continually at odds with the network censors until the show was finally cancelled after three seasons. In its continual conflicts with network executives, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour turned the variety show genre on its ear and paved the way for Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) and, in pushing TV’s all-out rebellion against the status quo, led an explosive charge that resulted in 1970s shows like All in the Family (1971).

These are but a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season. Some say that this was the greatest television season ever, a clear indication that TV had finally come of age. Because of shows like these, television would certainly never be the same again. And, come to think of it, neither would we!

Donna Braden, Curator of Public Life, was 13 years old during that memorable TV season and proudly wears her fan club button to every Monkees concert she still attends.

20th century, 1960s, TV, Star Trek, space, popular culture, music, Disney, by Donna R. Braden

Woodstock 1969

Estimate: 200,000 attendees. Over 400,000 showed up.

This flag was at Woodstock, too--a witness to this legendary event that reflected the 1960s counterculture movement’s quest for freedom and social harmony.

Flags like this one were provided to vendors, musicians, and technical crew to allow them access to the Woodstock Musical Festival grounds at Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm in upstate New York during the August 1969 event. They were to fly the flag from their vehicles or attach it to their booths.

Woodstock’s organizers--none of whom were over 27-- billed the event as “An Aquarian Exposition: Three Days of Peace and Music.” Held from Friday, August 15 and extending into the early morning of Monday, August 18, the music festival featured 32 iconic performers including Joan Baez, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, The Who, the Grateful Dead and Jimi Hendrix.

An Extraordinary Event Creates Enormous Challenges

There was a lot that went right with Woodstock. And many things that didn’t. The free-spirted and peaceful audience was filled with excitement and the musicians turned in electrifying performances. But the inexperienced organizers found their planning for this unprecedented event enormously inadequate--especially since they had to find a new venue only a few weeks before the concert.

The original location--an industrial park near Woodstock, New York--pulled out only a month and a half before the event. Fortunately, two weeks later Max Yasgur agreed to rent his Bethel, New York farm as the new venue. Nathan’s Hot Dogs--Coney Island’s famous vendor--pulled out when the location of the festival was moved. Two weeks before the concert, the organizers hired Food for Love, a trio with little experience in the food business. Larger food-vending companies hadn’t wanted to take on Woodstock--no one had ever handled food services for such a large event. Many were reluctant to put in the investment required--what if the festival didn’t draw enough of a crowd to make a profit?

Woodstock’s organizers had told the Bethel authorities that they expected no more than 50,000 people. As the event drew near, with 186,000 advance tickets sold, 200,000 concertgoers seemed a more likely estimate. The organizers then hurriedly tried to bring in more toilets, more water, and more food. Woodstock would ultimately draw an inconceivable number--over 400,000 concertgoers.

The roads around Bethel became jammed for miles with people heading to the concert. Many abandoned their vehicles and made the long walk in. The plugged roads would also make it extremely difficult to get needed supplies in.

The stage, parking lots, and concession stands were barely finished in time for the event. Concert-goers started arriving two days before--with the ticket booths and gates still uncompleted. Since people were able to just walk in, the organizers were forced to declare it a free concert--creating a monumental debt for them. (Though profits from a soundtrack and movie made from films of the Woodstock Festival would help bring down the debt.)

Most concertgoers arrived expecting to be able to purchase food. Food for Love concessions were quickly overwhelmed. Food became very hard to find. The Hog Farm, a West Coast commune hired to help with security, stepped in to help. They provided free food lines serving brown rice and vegetables--and granola. For some of the crowd, granola was nothing new. But for many it was. Granola would soon become the iconic food of the hippie era.

When the people of Sullivan County, where Yasgur’s farm was located, heard reports of food shortages, they gathered thousands of food donations, including 10,000 sandwiches, as well as water, fruit, and canned goods. Concertgoers who had brought their own food shared what they had with others.

It rained off and on during the event, interrupting or delaying performances--and creating a sea of mud. There weren’t enough receptacles for garbage. People waited an hour to use one of the portable toilets--then finding it an extremely unsanitary experience when they finally reached the front of the line.

Yet--despite unbelievably crowded conditions with wall-to-wall concertgoers, massive traffic jams, serious food shortages, no running water, no telephones, no electricity (except for the performance stage--and even that was sketchy at times), lack of sufficient restroom facilities, and the muddy quagmire--Woodstock was a place of communal peace and sharing for the three days of the festival. There were no reported incidents of violence among this gathering of over 400,000 people.

What Really Mattered

In the end, Woodstock wasn’t really about the food, the weather, or even the lack of creature comforts. For many who attended, Woodstock was about experiencing three days of legendary rock and roll music, being part of a peaceful community with hundreds of thousands of other young people, and immersing yourself freely and fully in the moment. (And, yes, free love and drugs in addition to rock and roll.) The Woodstock concert logo on this flag--the guitar and dove of peace--sums up the idealism of many of Woodstock’s concertgoers.

This flag’s faded and tattered appearance seems to suggest the logistical challenges of Woodstock. But it is more likely that its owner displayed this treasured keepsake for years after--the flag couldn’t fade this much or get this tattered in just three days. Instead, this flag attests to the eternal staying power of Woodstock as a cultural landmark for an entire generation of American youth--and for the nation.

Woodstock captured, vividly and indelibly, the spontaneity and free spirit of the counterculture movement of the 1960s--and its vision of freedom and social harmony that would ignite change in American society during the coming years.

Woodstock made history.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford

Woodstock has left its “mark”--not only in memory--but in archeology. Binghamton University’s archaeology team can really “dig it.” In 2018, they determined the location of the stage. By analyzing rocks and vegetation, they also located the area of the vendors’ booths, known as the Bindy Bazaar.

1960s, 20th century, New York, popular culture, music, by Jeanine Head Miller

Lunchbox Fandom

"Monkees" Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967 (THF92313)

Beaver Cleaver may have carried a plain metal lunch box to school, but lunch boxes with pictures on them have been big business since the days of the Leave It to Beaver television show. Since the 1950s, children have been persuading their parents that they absolutely must have a school lunch box sporting their favorite character. For, to show off a Davy Crockett or a Beatles or a Star Wars lunch box to the world (or to your friends, which meant basically the same thing) when these were popular was simply the essence of cool. And, for young children, this is still true today -- only the characters and the lunch box materials have changed.

The first true pictorial lunch box was created in 1950, when a painted image of Hopalong Cassidy was applied to a steel lunch box and matching thermos bottle. In the first year of its production, Nashville, Tennessee manufacturer Aladdin Industries sold an unprecedented 600,000 of these, at a (not inexpensive) retail cost of $2.39.

Three years later, American Thermos introduced a fully lithographed steel lunch box depicting Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. Sales of these reached an astonishing 2 1/2 million the first year, and these types of lunch boxes -- with pictures covering all sides -- immediately became the industry standard. The pictorial lunch box industry was off and running, and competition between companies became fierce. Over the next three decades, steel lunch boxes featured dozens of television shows, movies, popular musicians, sports stars, special events, fads, and famous places.

Pictorial lunch boxes made of waterproof vinyl wrapped around cardboard first came on the market in 1959. Their shiny, purse-like qualities lent themselves to pictorial themes marketed to girls, like the highly popular Barbie lunch boxes, introduced in 1961. Unfortunately, these could not stand up to heavy use -- their seams split and their corners crushed easily.

During the 1970s, vocal parents and school administrators began to complain that metal lunch boxes were to blame for students' injuries-enough so that, by 1987, lunch box manufacturers were forced to cease using steel in favor of safer (and cheaper) plastic.

Hopalong Cassidy, 1950 (THF92292)

William (Bill) Boyd brought this fictional character to life, first at the movies then on television in 1950. "Hoppy" became the first television hero for many American children. This show precedes the major era of television westerns ushered in by Gunsmoke in 1955, when the huge popularity of westerns signaled Americans' nostalgia for a simpler past and their need for clear-cut heroes and villains during an uncertain time.

Tom Corbett: Space Cadet, 1954 (THF92296)

On television from 1950 to 1955, this early science fiction show was a spin-off of a comic book and teen adventure novel series. The show, which took place in a futuristic world of scientific marvels, was made somewhat believable by the technical expertise of Willy Ley, an associate of Werner von Braun.

Rocky and Bullwinkle, 1962 (THF92316)

Like The Simpsons, Rocky and His Friends disguised adult entertainment in the form of a cartoon. The show aired from 1957 to 1963 during prime time, and with its clever, tongue-in-cheek scripts, it could well be considered the most subversive show about the Cold War of its time. From 1964 to 1973, the show continued under the new name The Bullwinkle Show, and it has since been entertaining children and adults alike through reruns and videos.

"Sock It To Me," 1968 (THF92319)

Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In was a mid-season replacement in 1968, and no one expected it to be very popular. That's probably why its producers were able to experiment with virtually a new format-a rapid-fire pace using video editing and no narrative structure-and a new kind of hip topicality couched in one-liner jokes. Although its novelty is lost to us today -- the one-liners seem hopelessly outdated, even old-fashioned -- catch-phrases like "Sock It to Me" have become instantly recognizable cultural icons, while the show's short skits, slapstick humor, and use of topical material helped to revolutionize television.

Happy Days, 1976 (THF92322)

A mid-season replacement in 1974, this show had its origins in a 1972 Love, American Style episode and took great advantage of the popularity of the film American Graffiti. The first television show to take place in an era where television had already been invented, this version of the 1950s was embraced especially by young people who had not known the real decade first-hand. The show's true star was "The Fonz," who may have seemed like an unlikely role model but became television's biggest star for several years.

Sesame Street, 1983 (THF92308)

From the time this show premiered on PBS in 1969, it quickly established itself as the most significant educational program in television history. Envisioned as an entertaining show for preschoolers-especially those from underprivileged backgrounds-to help prepare for school, Sesame Street incorporated the rapid-fire style of both television commercials and television programs like Laugh-In. With its consistently high quality and humor geared toward both children and their parents, this show continues to be extremely popular today.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, TV, school, popular culture, music, movies, food, childhood, by Donna R. Braden