Posts Tagged #thfcuratorchat

The Henry Ford’s Model i learning framework identifies collaboration as a key habit of an innovator. When considering inspirational collaborators from our collection, Charles and Ray Eames immediately came to mind. So, as part of The Henry Ford’s Twitter Curator Chat series, I spent the afternoon of June 18th sharing how collaboration played an important role in Charles and Ray Eames’ design practice. Below are some of the highlights I shared.

First things first, Charles and Ray Eames were a husband-and-wife design duo—not brothers or cousins, as some think! Although Charles often received the lion’s share of credit, Charles and Ray were truly equal partners and co-designers. Charles explains, "whatever I can do, she can do better... She is equally responsible with me for everything that goes on here."

THF252258 / Advertising Poster for the Exhibit, "Connections: The Work of Charles and Ray Eames," 1976

So when you see early advertisements that don’t mention Ray Eames as designer alongside Charles, know that she was equally responsible for the work. Here’s one such advertisement from 1947.

THF266928 / Herman Miller Advertisement, June 30, 1947, "Now Available! The Charles Eames Collection...."

And here’s another from 1952. I could go on, but I think you get the point!

THF66372 / Wood, Plastic, Wire Chairs & Tables Designed by Charles Eames, circa 1952

For more on Ray’s background and vital role in the Eames Office, check out this article from the New York Times, as part of their recently-debuted “Mrs. Files” series.

Charles and Ray Eames were experimenting with plywood when America entered World War II. A friend from the Army Medical Corps thought their molded plywood concept could be useful for the war effort—specifically for a new splint for broken limbs. Metal splints then in use were heavy and inflexible. Charles and Ray created a molded plywood version and sent a prototype to the U.S. Navy. They worked together and created a workable—and beautiful—solution for the military.

THF65726 / Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943

Out of these molded plywood experiments and products came the iconic chairs we know and love, like this lounge chair.

THF16299 / Molded Plywood Lounge Chair, 1942-1962

But Charles and Ray Eames wanted to make an affordable, complex-curved chair out of a single shell. The molded plywood checked some of their boxes, but the seat was not a single piece—not a single shell. They turned to other materials.

Around 1949, Charles brought a mock-up of a chair to John Wills, a boat builder and fiberglass fabricator, who created two identical prototypes. This is one of those prototypes—it lingered in Will's workshop, used for over four decades as a utility stool. The other became the basis for the Eames’ single-shell fiberglass chair.

THF134574 / Prototype Eames Fiberglass Chair, circa 1949

Charles and Ray recognized when their expertise fell short and found people in other fields to help them solve design problems. Their single-shell fiberglass chairs became a rounding success. Have you ever sat in one of them?

THF126897 / Advertising Postcard, "Herman Miller Furniture is Often Shortstopped on Its Way to the Destination...," 1955-1960

If you’ve been to the museum in the past few years, you’ve surely spent some time in another Eames project, the Mathematica: A World of Numbers…and Beyond exhibit. This too was a project full of collaborative spirit!

While those of us not mathematically inclined might have a hard time finding math fun, mathematicians truly think their craft is fun. Charles and Ray worked with these mathematicians to develop an interactive math exhibit that is playful.

THF169792 / Quotation Sign from Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond Exhibition, 1960-1961

Charles Eames said of science and play, “When we go from one extreme to another, play or playthings can form a transition or sort of decompression chamber – you need it to change intellectual levels without getting a stomachache."

THF169740 / "Multiplication Cube" from Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond Exhibition, 1960-1961

Charles and Ray Eames sought out expertise in others and worked together, understanding that everyone can bring something valuable to the table. This collaborative spirit allowed them to design deep and wide—solving in-depth problems across a multitude of fields.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. For a deeper dive into this story, please check out her long-form article, “What If Collaboration is Design?”

Eames, women's history, Model i, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White, #THFCuratorChat

A More Colorful World

This vibrant dress was likely dyed using an early aniline purple dye. Dress, 1863-1870 (THF182481)

In 1856, British chemistry student William Henry Perkin made a groundbreaking discovery. Perkin’s professor, August Wilhelm von Hofmann, encouraged his students to solve real-world problems. High on the list for Hofmann (and chemists all over the world) was the need to create a synthetic version of quinine. The only effective treatment for the life-threatening malaria disease, quinine could only be found in the bark of the rare Cinchona tree. Just a teenager at the time, Perkin decided to tackle this problem in a makeshift laboratory in his parents’ attic while on Easter holiday. Perkin experimented with coal tar—a coal byproduct in which Professor Hofmann saw promise—and made his discovery. No, not the discovery of a synthetic quinine, but something altogether different and extraordinarily significant nonetheless.

Wells, Richardson & Company "Leamon's Genuine Aniline Dyes: Purple," 1873-1880 (THF170208)

Perkin’s coal tar experiments resulted in a dark-colored sludge which dyed cloth a vibrant purple color. The purple dye was colorfast too (meaning it did not fade easily). He had discovered aniline purple—also known as mauveine or Perkin’s mauve—the first synthetic dye. Though this was not the medical miracle he had initially sought, he immediately understood the vast significance and marketability of a colorfast, synthetic dye.

Prior to Perkin’s discovery, natural dyes were used to color fabrics and inks and were derived primarily from plants, invertebrates, and minerals. Extracting natural dyes was time consuming and certain colors were rare. For example, arguably the most precious natural dye also happened to be a vibrant purple, called Tyrian Purple. This dye was found in the glands of several species of predatory sea snails. Each snail contained just a small amount of dye, so it took tens of thousands of sea snails to dye a garment a deep purple. Tyrian purple was so expensive that the very wealthy could afford to wear it. It’s no wonder purple was seen as the color of royalty!

Fabric Dye Swatch Book, "Kalle & Co. Manufacturers of Aniline Colors," circa 1900 (THF286612 and THF286614)

William Henry Perkin turned out to be multi-talented, finding success both as a chemist and as an entrepreneur. By 1857, with the help of his family, he began commercially manufacturing his aniline dye near London. He first produced purple, but other colors soon followed. The water in the nearby Grand Union Canal was said to have turned a different color each week depending on what dyes were being made. In 1862, Queen Victoria attended the Great London Exposition in a gown dyed with Perkin’s mauve and the color took off. Newspapers even reported a “mauve mania” in the 1860s! These new synthetic dyes were affordable too and other manufacturers around the world began to produce them. By 1880, companies like The Diamond Dye Company of Vermont sold many colors of dye—from magenta to gold or even “drab”—for just 10 cents apiece.

Trade Card for Diamond Dyes Company, 1880-1890 (THF214453 and THF214454)

Perkin’s discovery spawned an entirely new industry that transformed the world’s access to color. It is fitting that the very first synthetic dye created was purple—the color of Roman emperors and royalty could now be purchased for pennies. Louis Pasteur’s famous quote, “Chance favors the prepared mind,” characterizes Perkin’s serendipitous discovery well. His accidental discovery was far from simple luck – others may have dismissed it as a failed experiment. Instead, Perkin recognized the potential in his mistake and seized the opportunity to bring color to the masses.

Katherine White is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Europe, 19th century, 1850s, fashion, entrepreneurship, by Katherine White, #THFCuratorChat

Inventing America’s Favorite Cookie

Many of us have been baking a bit more than usual while staying at home. So, let’s take look at how America’s favorite cookie, the chocolate chip, was born.

Before we get to chocolate chips, let’s talk chocolate. It’s made from the beans of the cacao tree and was introduced by the Aztec and Mayan peoples to Europeans in the late 1500s. Then a dense, frothy beverage thickened with cornmeal and flavored with chilies, vanilla, and spices, it was used in ancient ceremonies.

Map of the Americas, 1550. THF284540

Colonial Americans imported cacao from the West Indies. They consumed it as a hot beverage, made from ground cacao beans, sugar, vanilla and water, and served it in special chocolate pots.

Chocolate Pot, 1760-1790 THF145291

In the 1800s, chocolate made its way into an increasing number of foods, things like custards, puddings, and cookies, and onto chocolate-covered candy. It was not just for drinking anymore!

Trade Card, Granite Ironware, 1880-1890 THF299872

Today, most Americans say chocolate is their favorite flavor. Are you a milk or dark chocolate fan? My vote? Dark chocolate.

Cookies were special treats into the early 1800s; sweeteners were costly and cookies took more time and labor to make. Imagine easing them in and out of a brick fireplace over with a long-handled peel.

Detail of late 18th century kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. See the kitchen for yourself with this virtual visit.

As kitchen technology improved in the early 1900s, especially the ability to regulate oven temperature, America’s cookie repertoire grew.

Detail of 1930s kitchen in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. See the kitchen yourself with this virtual visit.

Until the 1930s, baking chocolate was melted in a double boiler before being added to cookie dough. Check out this 1920 recipe for Chocolate Mousse from our historic recipe bank.

Then came Ruth Graves Wakefield and the chocolate chip cookie. Ruth, a graduate of the Framingham State Normal School of Household Arts, had taught high school home economics and had worked as a dietitian.

Image: "Overlooked No More: Ruth Wakefield, Who Invented the Chocolate Chip Cookie" from The New York Times

In 1930, 27-year-old Ruth and her husband Kenneth opened a restaurant in Whitman, Massachusetts called the Toll House Inn. The building had never been a toll house, but was located on an early road between Boston and New Bedford. The restaurant would grow from seven tables to 60.

Toll House Inn business card, 1930s. THF183299

A quick aside: our 1820s Rocks Village Toll House in Greenfield Village. Early travelers paid tolls to use roads or cross bridges. This one collected fares for crossing the Merrimack River.

Rocks Village, Massachusetts toll house in Greenfield Village. THF2033

With Ruth Wakefield’s background in household arts, she was well-prepared to put together a menu for her restaurant. It was a great location. The Toll House Inn served not only the locals, but people passing through on their way between Boston and Cape Cod.

Toll House Inn business card, 1930s. THF18330

Over time, Ruth’s reputation grew, and the restaurant became well-known for her skillful cooking, wonderful desserts, and excellent service. On the back of this circa 1945 Toll House Inn postcard, a customer wrote: “…down here two weeks ago & had a grand dinner.”

Toll House Inn postcard, about 1945. THF183298

Ruth Wakefield, curious and willing to experiment, liked to create new dishes and desserts to delight her customers. The inn had been serving a butterscotch cookie--which everyone loved--but Ruth wanted to “give them something different.”

About 1938, Ruth had an inspiration. She chopped up a Nestle’s semisweet chocolate bar with an ice pick and stirred the bits into her sweet butter cookie batter. The chocolate bits melted--and didn’t spread, remaining in chunks throughout the dough.

Recipe Booklet, "Favorite Chocolate Recipes made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate," 1940. THF125196

Legend has it that the cookies were an accident--that Ruth had expected to get all-chocolate cookies when the chocolate melted. One of those “creation myths?” A great marketing tale? Ruth was a meticulous cook and food science savvy. She said it was a deliberate experiment.

The marriage of sweet, buttery cookie dough and semisweet chocolate was a hit--the cookies quickly became popular with guests. Ruth shared the recipe when asked. Local newspapers published it. And she included it in the 1938 edition of her “Tried and True Recipes” cookbook.

The Toll House, Whitman, Massachusetts, circa 1945. THF183297

Nestle’s saw sales of its semisweet chocolate bar jump dramatically in New England--especially after the cookie was featured on a local radio show. When Nestle discovered why, they signed a contract with Ruth Wakefield, allowing Nestle to print the recipe on every package.

Nestle’s truck, 1934. Z0001194

Nestle began scoring its semisweet chocolate bar, packaging it with a small chopper for easy cutting into morsels. The result was chocolate “chips”--hence the name.

Recipe Booklet, "Favorite Chocolate Recipes made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate," 1940. THF125194

In 1939, Nestle introduced semisweet morsels. Baking Toll House Cookies became even more convenient, since you didn’t have to cut the chocolate into pieces.

Toll House Cookies and Other Favorite Chocolate Recipes Made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate, 1941. THF183303

Nestle included the Toll House Cookie “backstory” and the recipe in booklets promoting their semisweet chocolate.

During World War II, Nestle encouraged people to send Toll House Cookies to soldiers. For many, it was their first taste of a chocolate chip cookie--its popularity spread beyond New England.

Advertisement, "His One Weakness, Toll House Cookies from Home" November 1943. THF183306

The homemaker in this 1940s Nestle’s ad celebrates her success as a hostess when serving easy-to-make Toll House Cookies. Chocolate chips would, indeed, soon become our “national cookie.”

They Never Get Enough of My Toll-House Cookies!, 1945-1950. THF183304

Chocolate chip morsels were a great idea, so other companies followed suit.

Recipe Leaflet, "9 Famous Recipes for Hershey's Semi-Sweet Chocolate Dainties," 1956. THF295928

Other delectable treats, like these “Chocolate Refresher” bars shown in this 1960 ad, can be made with chocolate morsels. The possibilities are endless.

Nestle's Semi-Sweet Morsels Advertisement, "Goody for You," 1960. THF43907

More from The Henry Ford: Enjoy a quick “side trip” to this blog about more American chocolate classics.

Holiday baking is a cherished tradition for many. Chocolate chip cookies are frequently a key player in the seasonal repertoire. Hallmark captured holiday baking memories in this ornament.

Hallmark "Christmas Cookies" Christmas Ornament, 2004. THF177747

The museum’s 1946 Lamy’s Diner serves Toll House Cookies. Whip up a batch of chocolate chips at home and enjoy a virtual visit.

Cookie dough + chocolate chips = America’s favorite cookie! It may have been simple, but no one else had ever tried it before! Hats off to Ruth Wakefield!

Toll House Cookies and Other Favorite Chocolate Recipes Made with Nestle's Semi-Sweet Chocolate, 1941. THF183301

After all this talk of all things chocolate, are you ready for a cookie? This well-known cookie lover probably is!

Cookie Monster Toy Clock, 1982-1986. THF318447

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Massachusetts, 1930s, 20th century, women's history, restaurants, recipes, food, entrepreneurship, by Jeanine Head Miller, #THFCuratorChat

Kemmons Wilson’s Holiday Inns

Detail, THF104041

At a time when Americans are traveling less and the lodging industry is making big changes, let’s take a look back at the story of Kemmons Wilson, whose Holiday Inns revolutionized roadside lodging in the mid-20th century.

In the early days of automobile travel, motorists had few lodging options. Some stayed in city hotels; others camped in cars or pitched tents. Before long, entrepreneurs began to offer tents or cabins for the night.

Auto Campers with Ford Model T Touring Car and Tent, circa 1919 THF105459

More from The Henry Ford: Here’s a look inside a 1930s tourist cabin. Originally from the Irish Hills area of Michigan, the cabin is now on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. For motorists weary of camping out, these affordable “homes away from home” offered a warmer, more comfortable night’s sleep than a tent. You can read more about tourist cabins and see photos of this one on its original site in this blog post.

THF52819

Soon, “motels” -- shortened from “motor hotels” -- evolved to meet travelers’ needs. Compared to other lodging options, these mostly mom-and-pop operations were comfortable and convenient. They were also affordable. This expert set showcases the wide variety of motels that dotted the American landscape in the mid-20th century.

Crouse's Motor Court, a motel in Fort Dodge, Iowa THF210276

More from The Henry Ford: Photographer John Margolies documented the wild advertising some roadside motels employed to tempt passing motorists (check out some of his shots in our digital collections), and our curator of public life, Donna Braden, chatted with MoRocca about motorists’ early lodging options on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation (you can watch here).

After World War II, more Americans than ever before hit the open road for business and leisure travel. Associations like Best Western helped travelers find reliable facilities, but motel standards were inconsistent, and there was no guarantee that rooms would meet even limited expectations. When a building developer named Kemmons Wilson took a family road trip in 1951, he got fed up with motel rooms that he found to be uncomfortable and overpriced (he especially disliked being charged extra for his children to stay). Back home in Memphis, Tennessee, he decided to build his own group of motels.

As a young man, Wilson (born in 1913) displayed an entrepreneurial streak. To help support his widowed mother, Wilson earned money in many ways, including selling popcorn at a movie theater, leasing pinball machines, and working as a jukebox distributor. By the early 1950s, Wilson had made a name for himself in real estate, homebuilding, and the movie theater business.

Later in life, Kemmons Wilson tracked down his first popcorn machine and kept it in his office as a reminder of his early entrepreneurial pursuits. Detail, THF212457

Kemmons Wilson trusted his hunch that other travelers had the same demands as his own family -- quality lodging at fair prices. He opened his first group of motels, called “Holiday Inns,” in Memphis starting in 1952. Wilson’s gamble paid off -- within a few years, Holiday Inns had revolutionized industry standards and become the nation’s largest lodging chain.

An early Holiday Inn “Court” in Memphis, 1958 THF120734

What set Holiday Inns apart? Consistent, quality service and amenities Guests could expect free parking, air conditioning, in-room telephones and TVs, free ice, and a pool and restaurant at each location. And -- Kemmons Wilson determined -- no extra charge for children!

Swimming Pool at Holiday Inn of Daytona Beach, Florida, 1961 THF104037

Thanks to the chain’s reliable offerings (including complimentary toiletries!), many guests chose a Holiday Inn for every trip.

Holiday Inn Bar Soap, 1960-1970 THF150050

Holiday Inn Sewing Kit, circa 1968 THF150119

Inspired by Holiday Inns’ success, competitors began offering many of the same services and amenities. Kemmons Wilson had set a new standard -- multistory motels with carpeted, air conditioned rooms became the norm.

"Sol-Mar Motel," an example of a Holiday Inn-style motel in Jacksonville Beach, Florida THF210272

Kemmons Wilson knew location was key. He chose sites on the right-hand side of major roadways (to make stopping convenient for travelers) and took risks, buying property based on plans for the new Interstate Highway System.

Holiday Inn adjacent to highways in Paducah, Kentucky, 1966 THF287335

Holiday Inns’ iconic “Great Signs” beckoned travelers along roadways across the country from the 1950s into the 1980s. Kemmons Wilson’s mother, Ruby “Doll” Wilson, selected the sign’s green and yellow color scheme. She also designed the décor of the original Holiday Inn guestrooms!

Holiday Inn "Great" Sign, circa 1960 THF101941

Holiday Inns unveiled a new "roadside" design in the late 1950s: two buildings -- one for guestrooms and one for the lobby, restaurant, and meeting spaces -- surrounding a recreational courtyard. These roadside Holiday Inns featured large glass walls. The inexpensive material lowered construction costs while creating a modern look and brightening guestrooms. The recreated Holiday Inn room in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation demonstrates the “glass wall” design. Take a virtual visit here.

Holiday Inn Courtyard, Lebanon, Tennessee, circa 1962 THF204446

After becoming a public company in 1957, Holiday Inns developed a network of manufacturers and suppliers to meet its growing operational needs. To help regulate and maintain standards, property managers (called “Innkeepers”) ordered nearly everything -- from linens and cleaning supplies to processed foods and promotional materials -- from a Holiday Inns subsidiary. This menu, printed by Holiday Inns’ own “Holiday Press,” shows how nearly every detail of a guest’s stay -- even meals -- met corporate specifications.

Holiday Inn Dinner Menu, February 15, 1964 THF287323

By the 1970s, with more than 1,400 locations worldwide, Holiday Inns had become a fixture of the global and cultural landscape. Founder Kemmons Wilson even made the cover of Time magazine.

Time Magazine for June 12, 1972 THF104041

We hope his story inspires you to make your own mark on the American landscape -- or at least take a fresh look at the roadside the next time you’re out for a drive, whether down the street or across the country!

Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content at The Henry Ford, has happy poolside memories from a childhood stay at one of Holiday Inns’ family-friendly “Holidome” concepts. For more on the Holiday Inn story, check out chapter 9 of "The Motel in America," by John Jakle, Keith Sculle, and Jefferson Rogers.

20th century, travel, roads and road trips, hotels, entrepreneurship, by Saige Jedele, #THFCuratorChat

Be Empathetic like AAA

THF171209 / Automobile Club of Michigan Sign

It was my privilege to take over The Henry Ford’s Twitter feed for a while on the morning of May 14. Our theme for the day was "Be Empathetic." To me that means "be helpful and supportive," and those attributes remind me of early auto organizations like the Automobile Club of Michigan, founded in 1916. The Automobile Club of Michigan is one of several regional organizations that joined the American Automobile Association. Over the years, AAA’s work has included advocating for better roads, providing roadside assistance to stranded motorists, encouraging traffic safety generally – particularly near schools, and promoting tourism and travel by car throughout the United States. During my Twitter session, I shared several AAA items in the collections of The Henry Ford.

To the Rescue on the Road

THF103500 / Pamphlet from AAA of Michigan, "Emergency Road Service Guide," June 1951 / front

AAA began offering emergency roadside service in 1915. This 1951 pamphlet lists affiliated service garages throughout Michigan.

THF333431 / 1947 Ford Repair Truck at the Ralph Ellsworth Dealership, Garden City, Michigan, October 1946

This photo shows one of the AAA-affiliated wreckers that might've come to your aid in the late 1940s or early 1950s. In this case, it's a 1947 Ford.

THF304296 / Toy Truck, Used by James Greenhoe, 1937-1946

Children could play their own "roadside assistance" games with a toy truck like this one, made circa 1940.

Keeping Children Safe

THF153486 / Automobile Club of Michigan Safety Patrol Armband, 1950-1960

Speaking of children, one of AAA's most important initiatives is its School Safety Patrol program, established in 1920.

THF208042 / Music Sheet, "The Official Song of the Safety Patrol," 1937

Safety patrollers help adults in protecting students at crosswalks, and in bus and car drop-off and pick-up zones. Their dedicated efforts were celebrated in "Song of the Safety Patrol" from 1937.

THF289667 / Detroit Police Officer Anthony Hosang Talks with Safety Patrol Students on a Tour of the Ford Rouge Plant, May 10, 1950

Here's a group of Detroit safety patrol members in 1950. They're listening to police officer Anthony Hosang as a part of a tour through Ford's Rouge Plant – a reward for a job well done.

Reaching Your Destination

THF104025 / "Official Highway Map of Michigan," Automobile Club of Michigan, 1934

AAA also helps drivers find their way by publishing road maps. Here's one showing the Detroit metro area in 1934. Many of the highway numbers are familiar, but their routes have changed.

THF136038 / Log and Map of Automobile Routes between Detroit-Gary and Chicago, 1942

Here's a map of routes between Detroit and Gary-Chicago in 1942. The northern-most route (then U.S. 12) parallels modern I-94.

THF151706 / Automobile Club of Michigan, "Know Michigan Better, Stay Longer," Sign, 1950-1960

AAA also promotes tourism, encouraging drivers to explore America – and their own states. Residents can "know Michigan better," and visitors can "stay longer."

THF14793 / Travel Brochure for Holland Michigan, circa 1940

Springtime brings tulips, and what better place to enjoy them then Holland? (Holland, Michigan, that is.)

THF14744 / Souvenir Book, "Northern Michigan, Lower Peninsula," 1940

Here's a AAA guidebook promoting travel to Michigan's northern Lower Peninsula.

THF9103 / Host Mark Magazine, "Greenfield Village & Henry Ford Musem, A Bicentennial Site," 1976

And here's a familiar sight on the cover of AAA's Host Mark magazine. It's Greenfield Village, where bicentennial celebrations were underway throughout 1976.

It was great fun sharing these pieces with our Twitter followers. I also enjoyed answering some questions about our wider transportation holdings along the way. “Be Empathetic” – it’s an important lesson anytime, but especially right now.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

roads and road trips, travel, cars, by Matt Anderson, AAA, #THFCuratorChat

How Does Your Vegetable Garden Grow?

Do you raise vegetables to feed yourself? If the answer is “Yes,” you are not alone. The National Gardening Survey reported that 77 percent of American households gardened in 2018, and the number of young gardeners (ages 18 to 34) increased exponentially from previous years. Why? Concern about food sources, an interest in healthy eating, and a DIY approach to problem solving motivate most to take up the trowel.

The process of raising vegetables to feed yourself carries with it a sense of urgency that many of us with kitchen cabinets full of canned goods cannot fathom. Farm families planted, cultivated, harvested, processed and consumed their own garden produce into the 20th century. This was hard but required work to satisfy their needs.

Two members of the Lancaster Unit of the Woman’s National Farm and Garden Association digging potatoes, 1918. THF 288960

Seed Sources

Gardeners need seeds. Before the mid-19th century, home gardeners saved their own seeds for the next year’s crop. If a disaster destroyed the next year’s seeds, home gardeners had to purchase seeds.

Commercial seed sales began as early as 1790 in the community of Shakers at Watervliet, New York. The Mt. Lebanon, New York, Shaker community established the Shaker Seed Company in 1794. The Watervliet Shakers first sold pre-packaged seeds in 1835, but the Mt. Lebanon community dominated the garden seed business until 1891. They marketed prepackaged seeds in boxes like this directly to store owners who sold to customers.

Shakers Genuine Garden Seeds Box, 1861-1895. THF 173513

Satisfying the demand for garden seeds became big business. Entrepreneurs established seed farms and warehouses in cities where laborers cultivated, cleaned, stored and packaged seeds. The D.M. Ferry & Co. provides a good example.

D.M. Ferry & Company Headquarters and Warehouse, Detroit, Michigan, circa 1880. THF76854

Entrepreneurs invested earnings into this lucrative industry.

Hiram Sibley, who made a fortune in telegraphy, and spent 16 years as president of the Western Union Telegraph Company, claimed to have the largest seed farm in the world, and an international production and distribution system based in Rochester, New York, and Chicago, Illinois. Though the company name changed, the techniques of prepackaging seeds developed by the Shakers at Watervliet and direct marketing of filled boxes to store owners remained an industry standard.

Hiram Sibley & Co. Seed Box, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181542

Planting gardens requires prepackaged seeds (unless you save your own!). These little packets tell big stories about ingenuity and resourcefulness. We acquired this 1880s Sibley & Co. seed box from the Barnes Store in Rock Stream, NY in 1929.

The original Sibley seed papers and packets are on view in a replica Hiram Sibley & Co seed box in the J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village, which our members and guests will be able to enjoy once again when we reopen. Until then, take a virtual trip to the store by way of Mo Rocca and Innovation Nation.

Looking for gardening inspiration? Historic seed and flower packets can provide plenty! Survey the hundreds of seed packets dated 1880s to the present in our digital collections and create your own virtual garden.

The variety might astound you, from the mangelwurzel (raised for livestock feed) to the Early Acme Tomato and the Giant Rocca Onion.

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Beet Long Red Mangelwurtzel” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181520

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Tomato Early Acme” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF278980

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Onion Giant Rocca” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF279020

Families in cities often did not have land to cultivate, so they relied on the public markets and green grocers as the source of their vegetables.

Canned goods changed the relationships between gardeners and their responsibility for meeting their own food needs. Affordable and available canned goods made it easy for most to hang up their garden trowels. As a result, raising vegetables became a lifestyle choice rather than a necessity for most Americans by the 1930s.

Can Label, “Butterfly Brand Stringless Beans,” circa 1880. THF293949

Times of crisis increase both personal interest and public investment in home-grown vegetables, as the national Victory Garden movements of the 20th century confirm.

Victory Gardens

Man Inspecting Tomato Plant in Victory Garden, June 1944. THF273191

Victory Gardens, a patriotic act during World War I and World War II, provide important examples of food resourcefulness and ingenuity.

You can find your own inspiration from Victory Garden items in our collections – from 1918 posters to Ford Motor Company gardens during the 1930s, and home-front mobilization during World War II here.

Woman's National Farm and Garden Association at Dedham Square Truck Market, 1918. THF288964

But the “fruits” of the garden didn’t just stay at home. Entrepreneurial-minded Americans took their goods to market, like these members of the Woman's National Farm & Garden Association and their "pop-up" curbside market in Dedham, Massachusetts, in 1918.

Clara Ford with a Model of the Roadside Market She Designed, circa 1930. THF117982

Clara Ford, at one time a president of the Women’s National Farm and Garden Association, also believed in the importance of eating local. Read more about her involvement with roadside markets here.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

food, agriculture, gardening, #THFCuratorChat, by Debra A. Reid

New Acquisition: LINC Computer Console

A LINC console built by Jerry Cox at the Central Institute for the Deaf, 1964.

There are many opinions about which device should be awarded the title of "the first personal computer." Contenders range from the well-known to the relatively obscure: the Kenbak-1 (1971), Micral N (1973), Xerox Alto (1973), Altair 8800 (1974), Apple 1 (1976), and a few other rarities that failed to reach market saturation. The "Laboratory INstrument Computer" (aka the LINC) is also counted among this group of "firsts." Two original examples of the main console for the LINC are now part of The Henry Ford's collection of computing history.

The LINC is an early transistorized computer designed for use in medical and scientific laboratories, created in the early-1960s at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory by Wesley A. Clark with Charles Molnar. It was one of the first machines that made it possible for individual researchers to sit in front of a computer in their own lab with a keyboard and screen in front of them. Researchers could directly program and receive instant visual feedback without the need to deal with punch cards or massive timeshare systems.

These features of the LINC certainly make a case for its illustrious position in the annals of personal computing history. For a computer to be considered "personal," the device must have had a keyboard, monitor, data storage, and ports for peripherals. The computer had to be a stand-alone device, and above all, it had to be intended for use by individuals, rather than the large "timeshare" systems often found in universities and large corporations.

The inside of a LINC console, showing a network of hand-wired and assembled components.

Prototyping

In 1961, Clark disappeared from the Lincoln Lab for three weeks and returned with a LINC prototype to show his managers. His ideal vision for the machine was centered on user friendliness. Clark wanted his machine to cost less than $25,000, which was the threshold a typical lab director could spend without needing higher approval. Unfortunately, Clark’s budget goal wasn’t reached—when commercially released in 1964, each full unit cost $43,000 dollars.

The first twelve LINCs were assembled in the summer of 1963 and placed in biomedical research labs across the country as part of a National Institute of Health-sponsored evaluation program. The future owners of the machines—known as the LINC Evaluation Program—travelled to MIT to take part in a one-month intensive training workshop where they would learn to build and maintain the computer themselves.

Once home, the flagship group of scientists, biologists, and medical researchers used this new technology to do things like interpret real-time data from EEG tests, measure nervous system signals and blood flow in the brain, and to collect date from acoustic tests. Experiments with early medical chatbots and medical analysis also happened on the LINC.

In 1964, a computer scientist named Jerry Cox arranged for the core LINC team to move from MIT to his newly formed Biomedical Computing Laboratory at Washington University at St. Louis. The two devices in The Henry Ford's recent acquisition were built in 1963 by Cox himself while he was working at the Central Institute for the Deaf. Cox was part of the original LINC Evaluation Board and received the "spare parts" leftover from the summer workshop directly from Wesley Clark.

Mary Allen Wilkes and her LINC "home computer." In addition to the main console, the LINC’s modular options included dual tape drives, an expanded register display, and an oscilloscope interface. Image courtesy of Rex B. Wilkes.

Mary Allen Wilkes

Mary Allen Wilkes made important contributions to the operating system for the LINC. After graduating from Wellesley College in 1960, Wilkes showed up at MIT to inquire about jobs and walked away with a position as a computer programmer. She translated her interest in “symbolic logic” philosophy into computer-based logic. Wilkes was assigned to the LINC project during its prototype phase and created the computer's Assembly Program. This allowed people to do things like create computer-aided medical analyses and design medical chatbots. In 1964, when the LINC project moved from MIT to the Washington University in St. Louis, rather than relocate, Wilkes chose to finish her programming on a LINC that she took home to her parent’s living room in Baltimore. Technically, you could say Wilkes was one of the first people in the world to have a personal computer in her own home.

Wesley Clark (left) and Bob Arnzen (right) with the "TOWTMTEWP" computer, circa 1972.

Wesley Clark

Wesley Clark's contributions to the history of computing began much earlier, in 1952, when he launched his career at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory. There, he worked as part of the Project Whirlwind team—the first real time digital computer, created as a flight simulator for the US Navy. At the Lincoln Lab, he also helped create the first fully transistorized computer, the TX-0, and was chief architect for the TX-2.

Throughout his career, Clark demonstrated an interest in helping to advance the interface capabilities between human and machine, while also dabbling in early artificial intelligence. In 2017, The Henry Ford acquired another one of Clark's inventions called "The Only Working Turing Machine There Ever Was Probably" (aka the "TOWTMTEWP")—a delightfully quirky machine that was meant to demonstrate basic computing theory for Clark's students.

Whether it was the “actual first” or not, it is undeniable that the LINC represents a philosophical shift as one of the world’s first “user friendly” interactive minicomputers with consolidated interfaces that took up a small footprint. Addressing the “first” argument, Clark once said: "What excited us was not just the idea of a personal computer. It was the promise of a new departure from what everyone else seemed to think computers were all about."

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

Missouri, women's history, technology, Massachusetts, computers, by Kristen Gallerneaux, 20th century, 1960s, #THFCuratorChat

Celebrating Earth Day

As we celebrate Earth Day, do you know which iconic symbol for the environmentalism movement came first? The bird wing design on an Earth Day poster or the “Give Earth a Chance” button? If you thought it was the button, you’re correct.

Give Earth a Chance Button, 1970. THF284833

Students at the University of Michigan formed ENACT (Environmental Action for Survival Committee, Inc.) in 1969. They prototyped the button and started selling it in late 1969, months before the official Earth Day on April 22, 1970. This button was reputedly worn during Earth Day 1970.

Advertising Poster, "Earth Day April 22, 1970.” THF81862

If you picked the wing, the artist that created the poster, Jacob Landau, used a stylized wing in earlier artwork. Landau, an award-winning illustrator and artist, taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He created this poster for the Environmental Action Coalition which coordinated New York Earth Day activities in 1970.

Did Earth Day launch the Age of Conservation?

“Newsweek” Magazine. THF139548_redacted

Newsweek itemized threats that ravaged the environment in its January 26, 1970 issue. All resulted from human actions. Emissions and sewage polluted the air and water. Garbage clogged landfills. Population growth threatened to overtake available food supplies. Solving these challenges required cooperation and unity on the part of individuals as well as local, state, and national governments. Editors believed that replenishing the environment to sustain future generations could be “the greatest test” humans faced. They featured the “Give Earth a Chance” button with the caption: "Symbol of The Age of Conservation?"

What to do to save the Earth?

The overall goal of replenishing the environment to sustain future generations required action on many fronts. More than 20 million people across the United States participated in the first Earth Day. The teach-ins informed, marches conveyed the intensity of public interest, and graphic arts spoke volumes about what needed to be done.

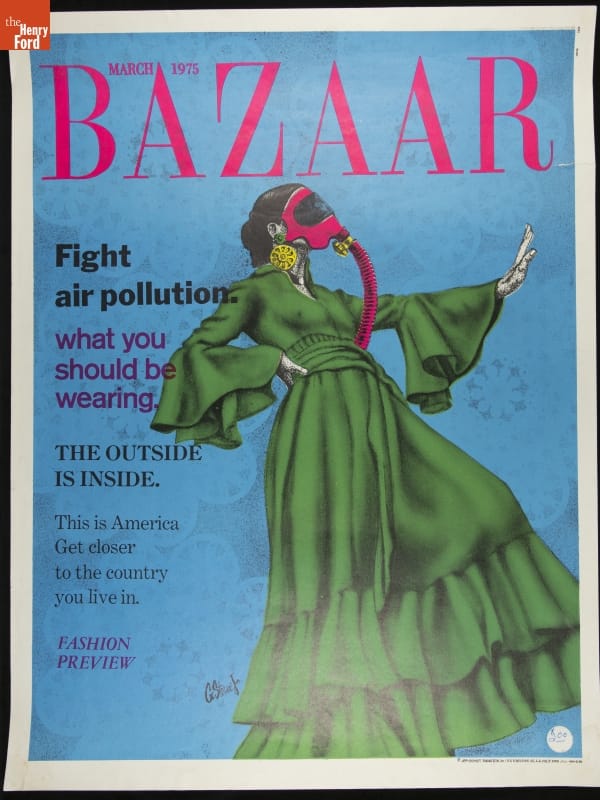

“March 1975, Bazaar, Fight Air Pollution, What You Should Be Wearing,” Poster, 1970. THF288328

This 1970 poster envisioned high fashion of the future, complete with a gas mask accessory. The moral of the story? Self-protection would not solve the problem of environmental pollution.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 empowered states and the national government to reduce emissions through regulation. This applied to industrial emissions as well as mobile sources (trains, planes, and automobiles, among others).

Interest in Recycling Grows

Poster by Eli Leon for Ecology Action, “Recycle” 1971. THF284835

Recycling emerged as a natural outgrowth of Earth Day, but local efforts could not succeed without explanation. First, consumers had to be convinced to save their newspapers, bottles, and cans, and then to make the extra effort to drop them off at centralized locations. This flyer showed how every-day consumer activity (grocery shopping) contributed to deforestation, littering, and garbage pile-up. Everybody could participate in the solution – recycling.

Recycling cost money, and this caused communities to balance what was good for the Earth, acceptable to residents, and possible within available operating funds. Even if customers voluntarily recycled, it still cost money to store recyclables and to sell the post-consumer materials to buyers.

Recycling Bin, Designed for Use in University City, Missouri, 1973. THF181540

City officials and residents in University City, Missouri, started curbside newspaper recycling in 1973, one of the first in the country to do so. Some argued that the city lost money because the investment in staff and trucks to haul materials cost more than the city earned from the sale, but saving the planet, not profit, motivated the effort. Eight years into the program, in 1981, city officials estimated that newspaper recycling kept 85,000 trees from the paper mill.

Easter Greeting Card, "Happy Easter," 1989-1990. THF114178

Today, more than 1/3 of post-consumer waste, by weight, is paper. Processing requires energy & chemicals, but recycled paper uses less water and produces less air pollution than making new paper from wood pulp. Maybe you buy greeting cards of 100% recycled paper, like this late 1980s example from our digital collections.

Environmentalism and Vegetable Gardening

Awareness of environmental issues affected the habits and actions of gardeners. Home gardening became an act of self-preservation in the context of Earth Day and environmentalism.

Lyman P. Wood founded Gardens for All in 1971, and the association conducted its first Gallup poll of a representative sample of American gardeners in 1973. It helped document the actions of gardeners, those proactive subscribers to new serials such as Mother Earth News. It confirmed their demographics and their economic investment.

Mother Earth News, 1970. THF290238

Raising vegetables using organic or natural fertilizers and traditional pest control methods became an act of resistance to increased use of synthetic chemical applications as concern about residual effects on human health increased.

How to Grow Vegetables and Fruits by the Organic Method, 1971. THF145272

Interest in organic methods remains high as concern about genetic-engineered foods polarizes consumers. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines biotechnology broadly. The definition includes plants that result from selective breeding and hybridization, as practiced by Luther Burbank, among others, as well as genetic modification accomplished by inserting foreign DNA/RNA into plant cells. This last became commercially viable only after 1987. These definitions affect seed marketing, as this “organic” Burbank Tomato (not genetically engineered) indicates.

Charles C. Hart Seed Company “Burbank Slicing Tomato” Seed Packet, circa 2018. THF276144

What Gardening Means Today

Gardening as an act of personal autonomy

"Assuming Financial Risk," Clip from Interview with Melvin Parson, April 5, 2019. THF295329

Social justice entrepreneurs believe gardens and gardening can change lives. Learn about the work of Melvin Parson, the Spring 2019 William Davidson Foundation Entrepreneur in Residence at The Henry Ford, in this expert set. You can also learn more from Will Allen in an interview in our Visionaries on Innovation series.

Environmentalism

The 1970 “The Age of Conservation” has changed with the times, but individual acts and world-wide efforts still sustain efforts to “Give the Earth a Chance.” You can learn more about environmentalism over the decades by viewing artifacts here.

To read more about Adam Rome and The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (2013), take a look at this site.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. This post came from a Twitter chat hosted in celebration of Earth Day 2020.

20th century, 1970s, nature, gardening, environmentalism, by Debra A. Reid, #THFCuratorChat

Diners: An American Original

In 1984, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation acquired an old, dilapidated diner. When Lamy’s Diner—a Massachusetts diner from 1946—was brought into the museum, it raised more than a few eyebrows. Was a common diner, from such a recent era, worthy of restoration? Was it significant enough to be in a museum?

Happily, times have changed. Diners have gained newfound respect and appreciation. A closer look at diners reveals much about their role and significance in 20th-century America.

Diner, Wason Mfg. Co., interior, 1927-9. THF228034

Diners changed the way Americans thought about dining outside the home. A uniquely American invention, diners were convenient, social, and fun.

Horse-drawn lunch wagon, The Way-side Inn. THF38078

Diners originated with horse-drawn lunch wagons that came out on city streets at night, providing food to workers. They also attracted “night owls” like reporters, politicians, policemen, and supposedly even underworld characters!

Peddler’s cart: NYC street scene, 1890-1915. THF241185

Most people agree that horse-drawn lunch wagons evolved from peddler’s carts, like those shown here on this New York City street.

Cowboys at the Chuck Wagon, Crazy Woman Creek, Wyoming Territory, 1885. THF124569

Some people even think that cowboy chuck wagons helped inspire lunch wagons. Here’s a cool scene of a group of cowboys in Wyoming from 1885. Take a look at the fully outfitted chuck wagon in the picture above.

The Owl Night Lunch Wagon. THF88956

The Owl Night Lunch Wagon in Greenfield Village is thought to be the last surviving lunch wagon in America!

Visitors at the Owl Night Lunch Wagon. THF113945

Henry Ford ate here as a young engineer at Edison Illuminating Company in downtown Detroit. In 1927, Ford acquired the old lunch wagon to become the first food operation in Greenfield Village. Notice the menu and clothing worn by the guests.

In this segment of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, you can watch Mo Rocca and me eating hot dogs with horseradish at the Owl—just like Henry Ford might have done back in the day!

Walkor Lunch Car, c. 1918. THF297240

When cars increased congestion on city streets, horse-drawn lunch wagons were outlawed. To stay in business, operators had to re-locate their lunch wagons off the street. Sometimes these spaces were really cramped.

County Diner, 1926. THF297148

By the 1920s, manufacturers were producing complete units and shipping them to buyers’ specified locations. Here’s a nice exterior of one from that era.

Hi-Way Diner, Holyoke, Mass., ca. 1928. THF227976

These units were roomier and often cleaner than the by-now-shabby lunch wagons. To make them seem more upscale, people began calling these units “diners,” evoking the elegance of railroad dining cars.

Ad with streamlined diner, railroad, and airplane, 1941. THF296820

As more people got used to eating out in diners, more diners were produced. By the 1940s, some diners took on a streamlined form—inspired by the designs of the new, modern streamlined trains and airplanes.

Lamy’s Diner. THF77241

By the 1940s, there were so many diners around that this era became known as the “Golden Age of Diners.” This is where our own Lamy’s Diner comes in. It was made in 1946 by the Worcester Lunch Car Company of Massachusetts. You may not be able to get a cup of coffee and a piece of pie inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation right now, but you can visit Lamy’s virtually through this link.

Move of diner from Hudson, Mass., 1984. THF124974

The Henry Ford acquired Lamy’s Diner in 1984, then restored it for a new exhibition, “The Automobile in America Life” (1987). Here’s an image of it being lifted for its move to The Henry Ford.

Lamy’s Diner on original site. THF88966

Lamy’s Diner was originally located in Marlborough, Mass. Here’s a photograph of it on its original site. But, like other diners, it moved around a lot—to two other towns over the next four years.

Snapshot of Clovis Lamy in diner, ca. 1946. THF114397

Clovis Lamy was among other World War II veterans who dreamed of owning his own business when the war was over, and diners promised easy profits. As you can see here, he loved talking to people from behind the counter. From the beginning, Lamy’s Diner was a hopping place all hours of the day and night. You can read the whole story of Clovis Lamy and his diner in this blog post.

Lamy’s as a working restaurant in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

In 2012, Lamy’s became a working restaurant again—inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Nowadays, servers even wear diner uniforms that let you time-travel back to the 1940s. A few years ago, the menu was revamped. So now you can order frappes (Massachusetts-style milkshakes), New England clam chowder, and some of Clovis Lamy’s original recipes. Read more about the recent makeover here.

View of a McDonalds restaurant and sign, 1955. THF125822

Diners declined when fast food restaurants became popular. McDonald’s was first, with food prepared by an assembly-line process, paper packaging, and carry-out service. Check out this pre-Golden Arches McDonald’s.

Mountain View steel diner, Village Diner, Milford, PA, c. 1963. THF297276

The 1982 movie Diner helped spur a new revival in diners, as some people got tired of fast food and chain restaurants. Here’s an image of a Mountain View steel diner, much like the one used in that movie.

Dick Gutman in front of a Kullman diner, 1993. THF297029

One person was particularly instrumental in documenting and helping revive the interest in diners. That’s diner historian Richard Gutman. Here he is in 1993 with camera in hand—in front of a diner, of course. We are thrilled that last year, Richard donated his entire collection of historic and research materials to The Henry Ford—including thousands of slides, photos, catalogs, postcards, and diner accouterments!

Modern Diner, Pawtucket, RI, 1974 slide. THF296836

Richard not only documented existing diners but helped raise awareness of the need to save diners from extinction. The Modern Diner, shown here, was the first to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places (1978).

Robbins Dining Car, Nantasket, Mass., ca. 1925. THF277072

Be sure to check out our Digital Collections for many items from Richard’s collection already online.

Diners continue to have popular appeal. They offer a portal into 20th-century social mores, habits, and values. Furthermore, they represent examples of American ingenuity and entrepreneurship that connect to small business startups and owners today.

This post was originally part of our weekly #THFCuratorChat series. Follow us on Twitter to join the discussion. Your support helps makes initiatives like this possible.

Additional Readings:

20th century, restaurants, Henry Ford Museum, food, Driving America, diners, by Donna R. Braden, #THFCuratorChat

Travel has changed a lot over the past 150 years, from something that only the wealthy could afford to something for everyone. This post looks at the relationship between forms of luggage and methods of transportation, from stagecoaches through airline travel.

THF206455 / Concord Coach Hitched to Four Horses in Front of Post Office, circa 1885.

In the 19th century, travel was relatively uncommon. People who traveled used heavy trunks to carry a great number of possessions, usually by stagecoach and rail. The traveler didn't usually hand his or her luggage, porters did all the work. As late as 1939, railway express companies transferred trunks to a traveler's destination.

THF288917 / Horse-Drawn Delivery Wagon, "Express Trunks Transferred & Delivered, We Meet All Trains"

A typical 19th century American trunk, this example was used by Captain Milton Russell during the Civil War.

THF174670 / Carpet Bag, 1870-1890

People used valises or other types of lighter bags in the 19th century. This is a carpet bag made of remnants of "ingrain" carpet.

THF145224 / Trunk Used for File Storage By Harvey S. Firestone, circa 1930

In the 19th and 20th centuries, "steamer trunks" were used on ocean-going vessels in your state room. It was literally a closet in a box. This example was used by Harvey Firestone to hold important papers.

THF105708 / Loading Luggage into the Trunk of 1939 Ford V-8 Automobile

With the rise of automobile travel, more people had access and suitcases (as we know them) became the norm. Much easier to manager than steamer trunks, they fit a car trunk.

THF166453 / Oshkosh "Chief" Trunk, Used by Elizabeth Parke Firestone, 1920-1955

This is a standard 1920s/1930s suitcase made by the Oshkosh Suitcase Co. of Oshkosh, Wisc. This was for auto travel, etc. It was for everything! This belonged to Elizabeth Parke Firestone.

THF285021 / Passengers Entering Ford Tri-Motor 4-AT Airplane, 1927

With the rise of air travel, passengers were limited to lighter-weight bags due to weight restrictions.

THF169109 / Orenstein Trunk Company Amelia Earhart Brand Luggage Overnight Case, 1943-1950

Famed aviator Amelia Earhart licensed her own line of luggage beginning in 1933. It was marketed as "real 'aeroplane' luggage." It was lightweight and made to last. (Learn more about the famed aviator as an entrepreneur in this expert set.)

THF318431 / Postcard, Plymouth Savoy 4-Door Sedan, 1961-1962

By the 1960s, fashionable Americans bought luggage in colorful sets, like this lady directing the porters. Notice she also has a steamer trunk!

THF154923 / Travelpro Rolling Carry-On Suitcase, 1997

With the explosive growth of air travel in the '80s & '90s, & the growth of airports, travelers needed light and portable bags. Roller bags were the answer. They could be carried on or checked.

THF94783 / American Airlines Duffel Bag, circa 1991

Flight attendants need to carry extremely light bags. This American Airlines tote bag was used by a flight attendant in the 1990s.

How have your luggage choices and preferences evolved over time?

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. These artifacts were originally shared as part our weekly #THFCuratorChat series. Join the conversation! Follow @TheHenryFord on Twitter.

If you’re enjoying our content, consider a donation to The Henry Ford. #WeAreInnovationNation