Posts Tagged henry ford

Clara Ford’s Travel Diaries

When traveling today, it is easy to document our journey through swift clicks of our phones and cameras. The people, sights, and sounds of a moment are captured and recorded through photos, videos, and social media posts making it easy to reflect on where we were and what we enjoyed.

The desire to document a memorable trip has remained a common tradition and in the age of Clara Ford, was accomplished through travel journals or diaries. Even with the advent of photography, film had to be thoughtfully allocated to document the most meaningful memories from a trip.

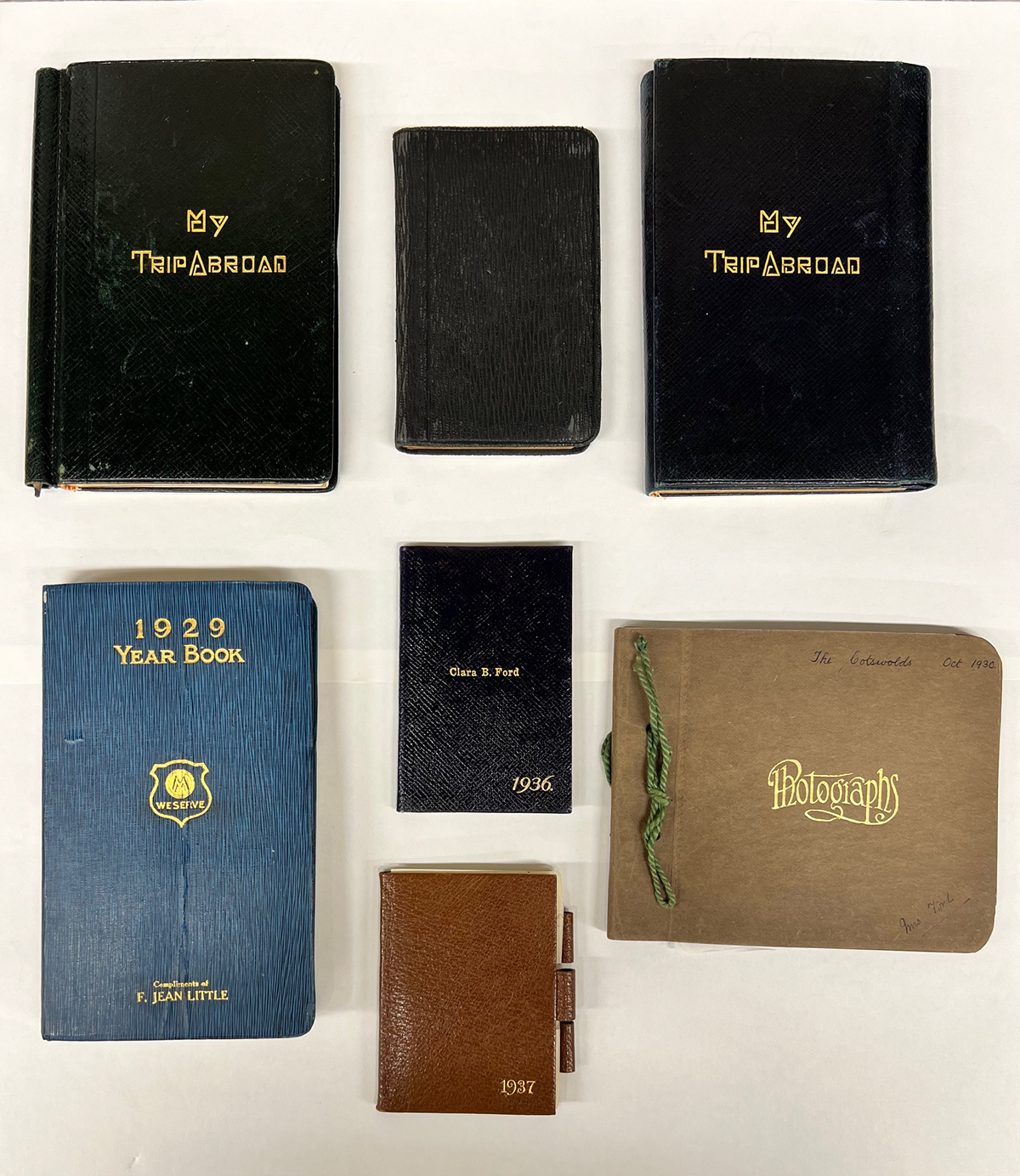

The Henry Ford's collections include several travel diaries written by Clara Ford dating from 1912 to 1945. Clara did not keep a diary for every trip she took. As the wife of Henry Ford, her travels were frequent and varied. Most of the diaries document her travels overseas, a momentous journey for anyone at that time, and winter retreats to Richmond Hill, Georgia, and Fort Meyers, Florida.

Clara Ford Travel Diaries. Accession 1, Box 105 and 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Unlike social media posts, travel diaries were not always intended for sharing or future publication. Entries were meant to document travel details and for personal reflection.

This means the writer was often sharing their thoughts more freely. For a notable figure like Clara Ford, travel diaries provide insight into her personal opinions and interests that might have been left out of an official record of her travels. They also provide a valuable record of Clara at a given time and place. They tell us who she interacted with, where she stayed, and what she saw.

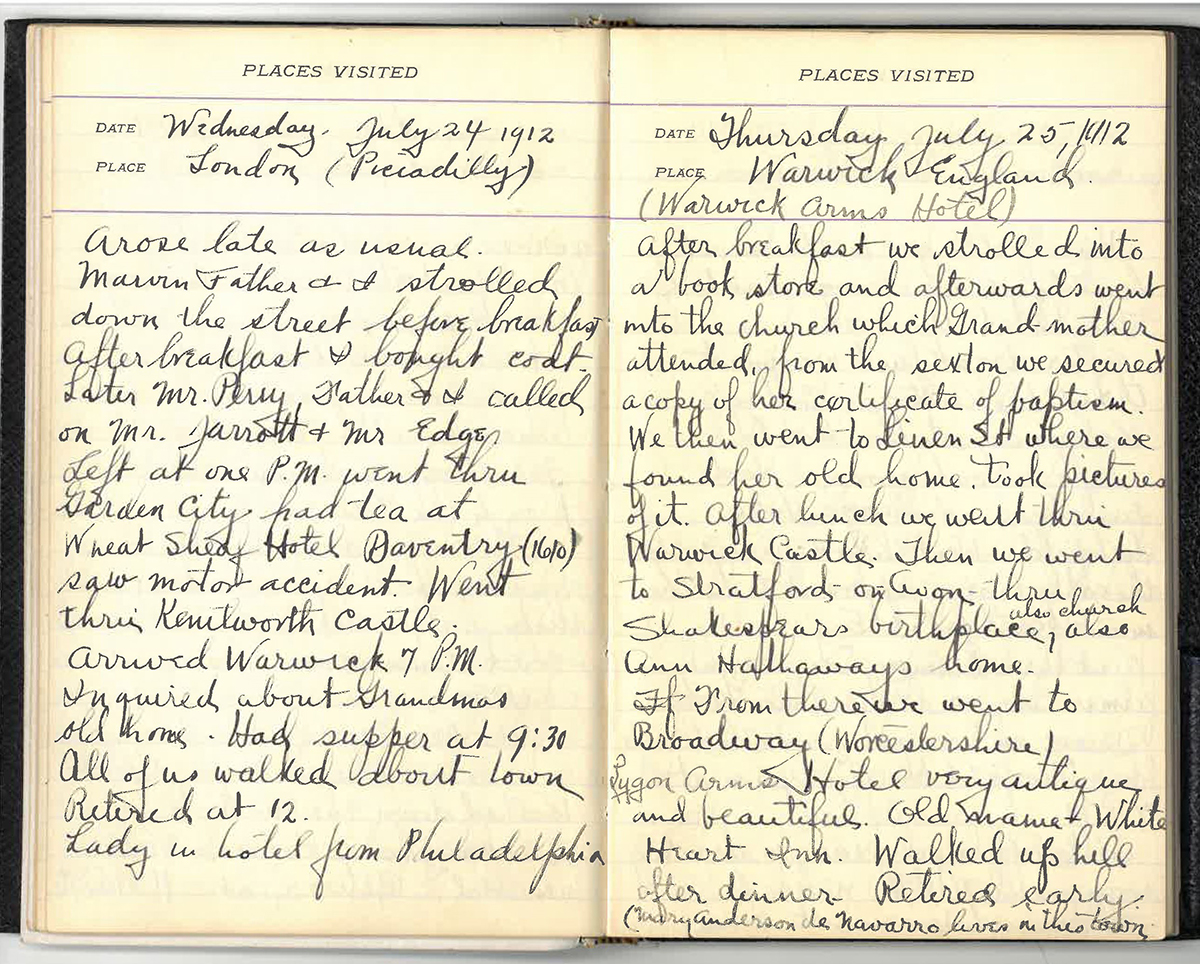

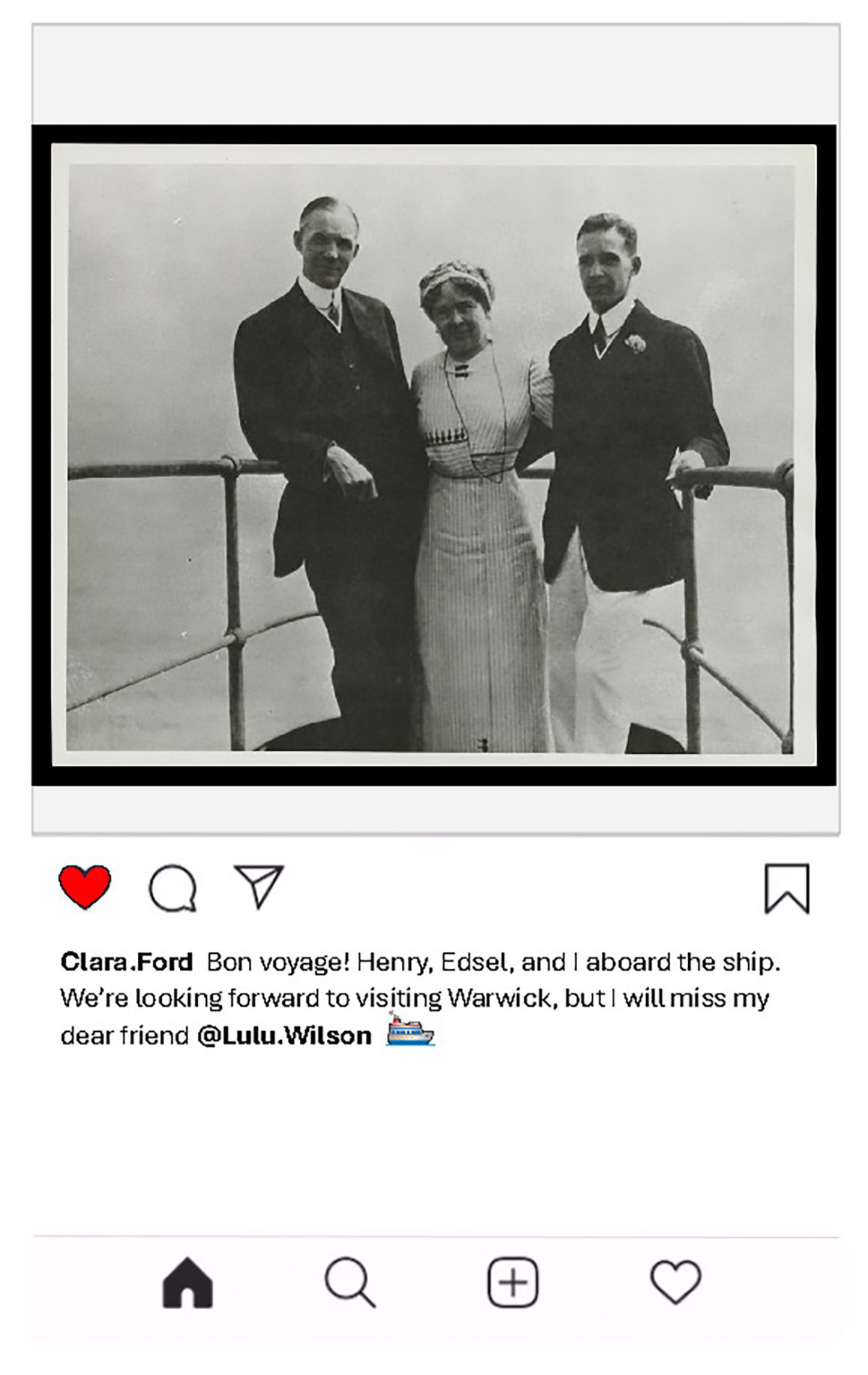

The earliest travel diary penned by Clara was for her first trip to Europe in 1912. She, Henry, and Edsel explored sites throughout Great Britain and France.

Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford aboard Ship on their European Trip, 1912. / THF117563

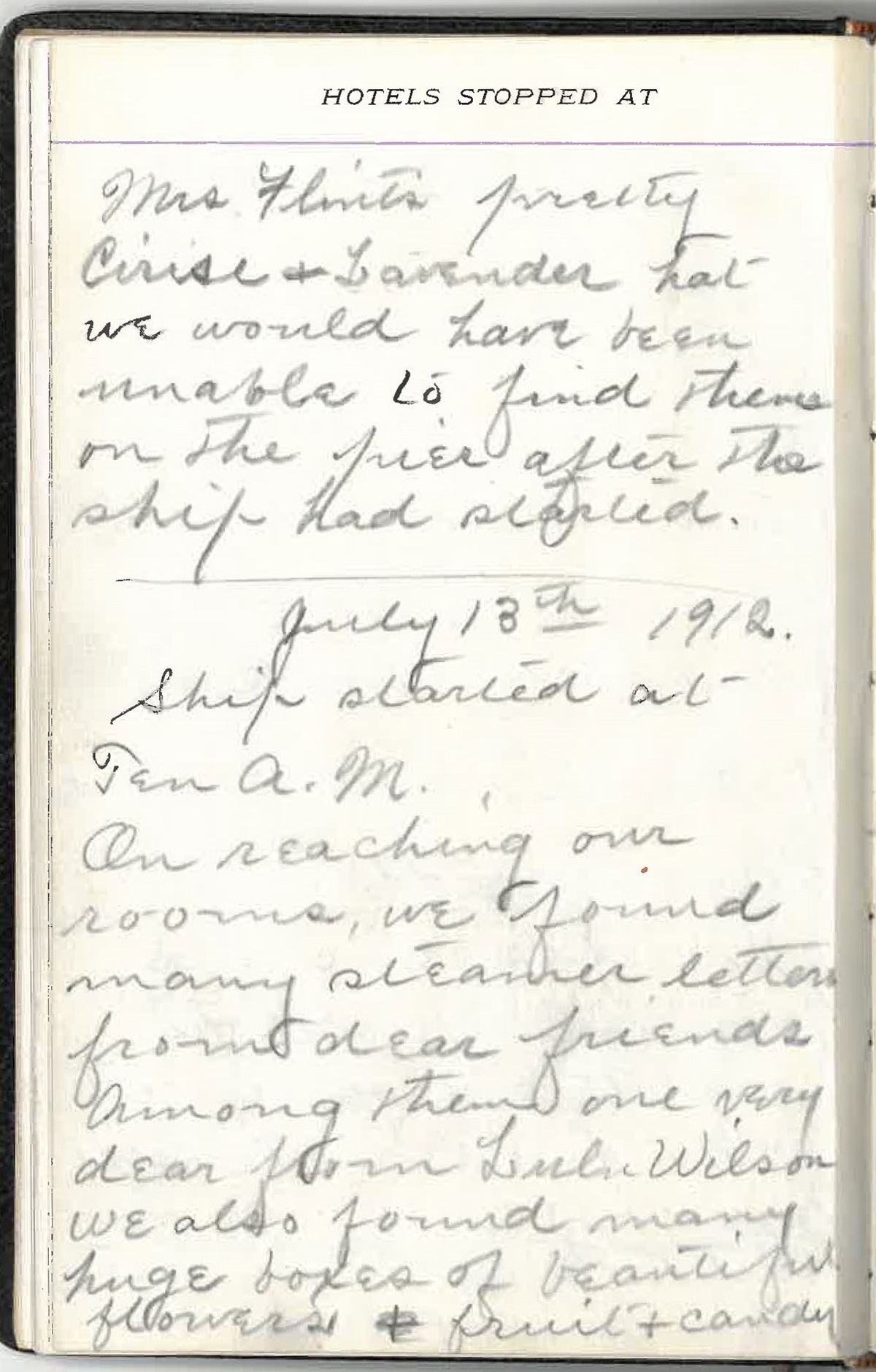

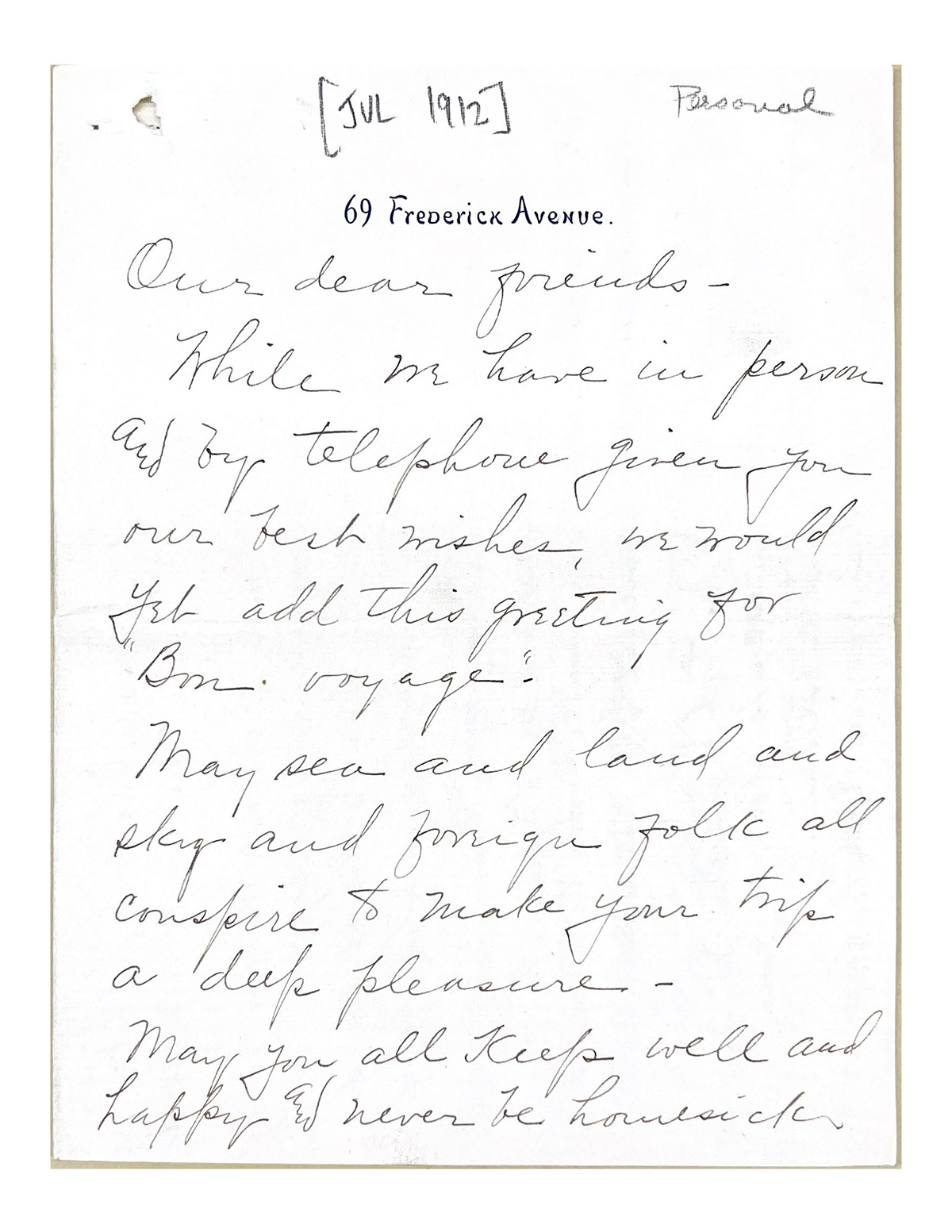

In one of the first entries, Clara documents the time the ship set sail and describes the warm welcome they received. Among flowers, fruits, and candy were several letters from friends wishing them a “Bon Voyage!” Clara references a letter from her close friend, Lulu Wilson, which we also hold in our collection. Connecting archival records like these illustrates a larger picture for historians and researchers.

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Letter to Clara Ford from her friend Lulu Wilson, July 1912. Accession 1, Box 66. / Image by Lauren Brady

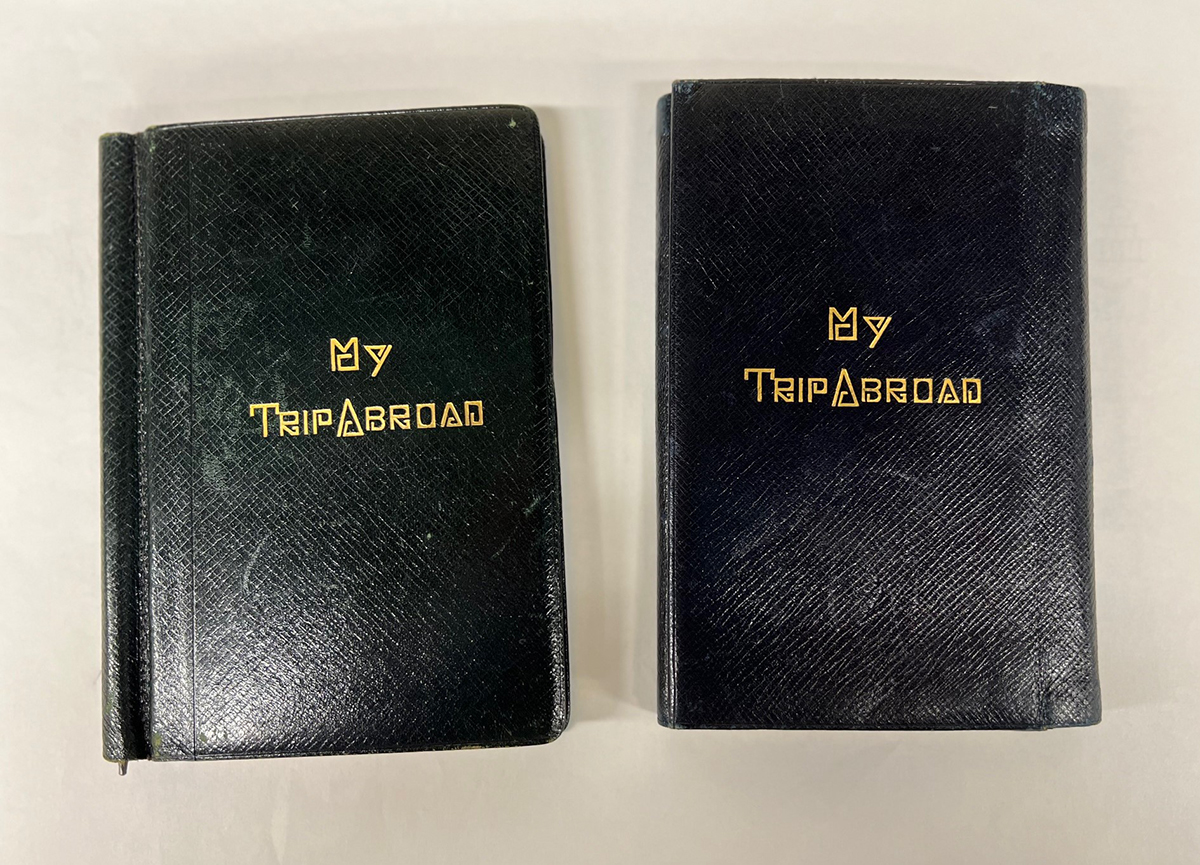

In addition to Clara's diary, we also have Edsel's diary from this trip in our collection.

Clara Ford's and Edsel Ford's Travel Diaries, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

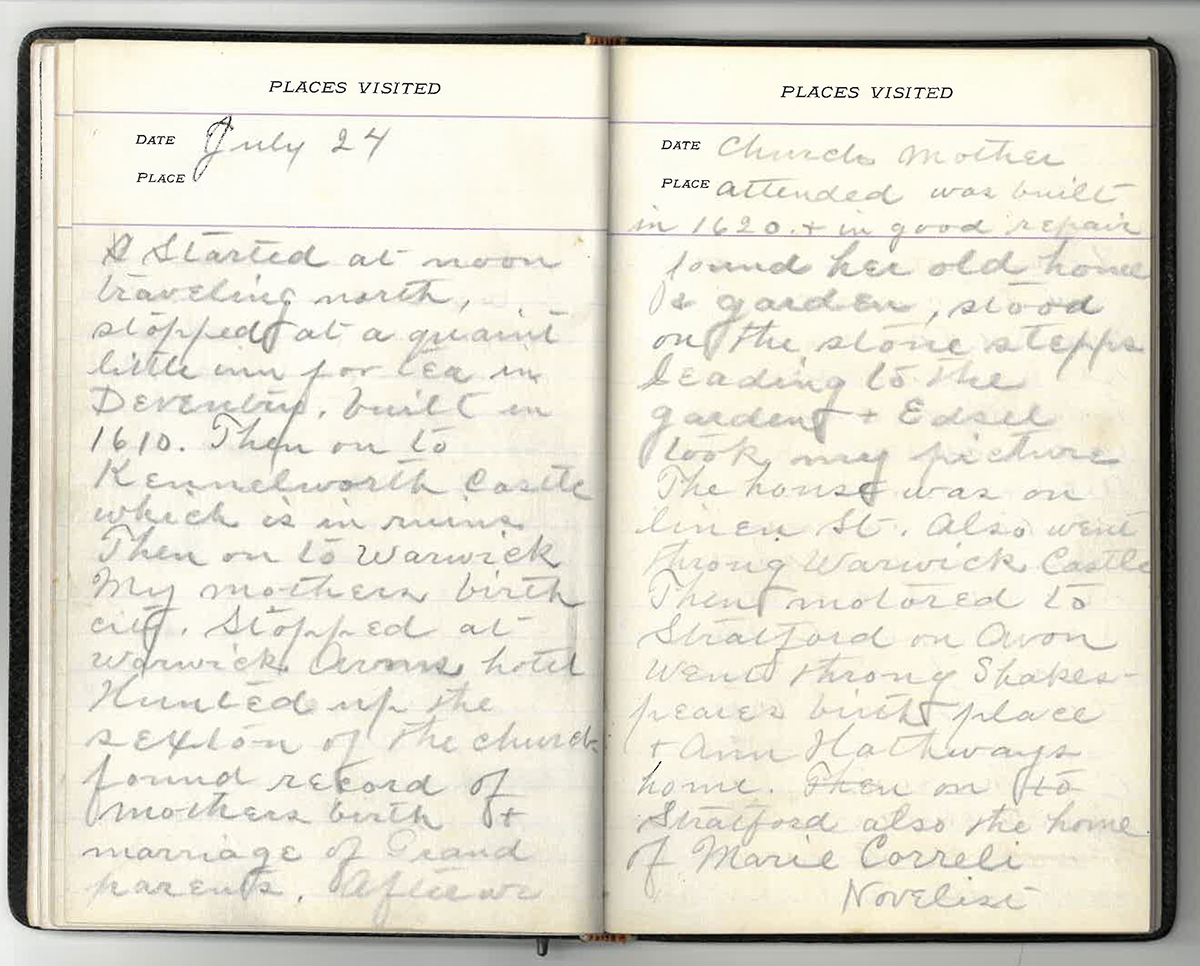

During their travels, they visited Clara's ancestral home. There are parallel accounts of the visit in both diaries. It reads as a meaningful visit for Clara who also describes important genealogical details about her family history that may not have been recorded elsewhere in our archival collections.

Edsel Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

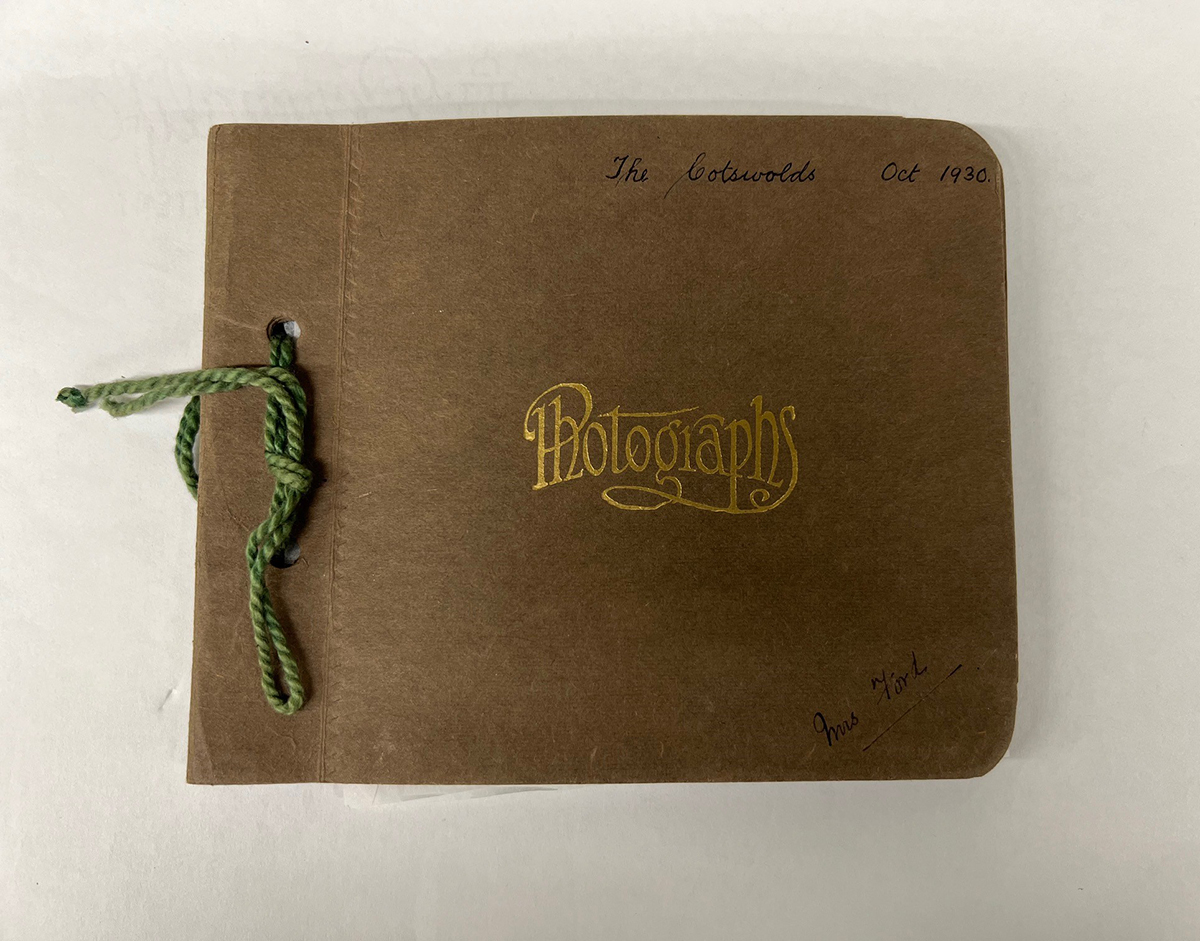

The Fords returned to Europe many times, including a trip in 1930 which Clara documented in a diary and a unique photo album. In her diary, Clara makes note of Henry's visit to Buckingham Palace before he departed for the Cotswold region of England where Cotswold Cottage had recently been acquired for Greenfield Village.

This visit received special commemoration in a photo diary with handwritten notes by Clara.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

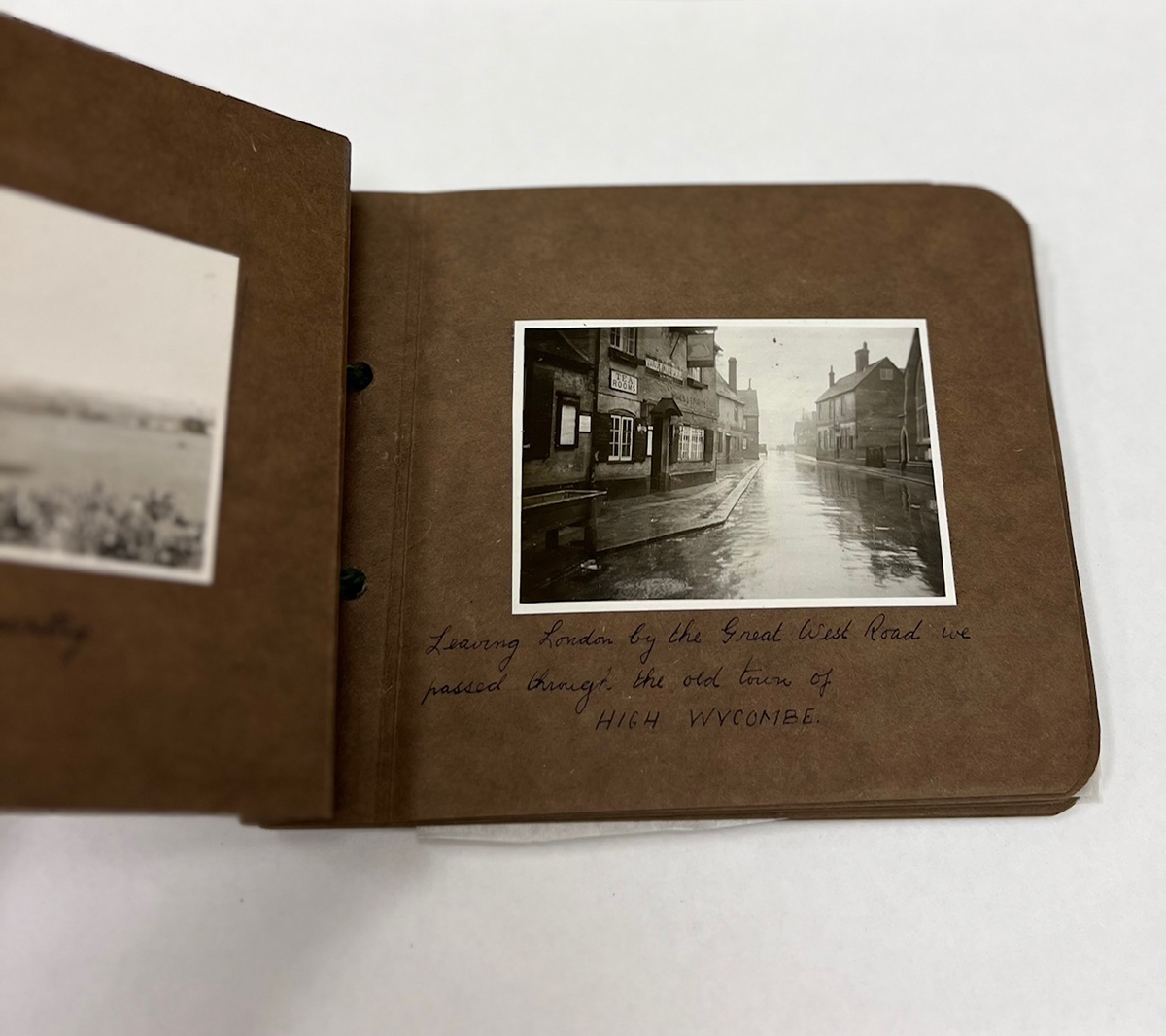

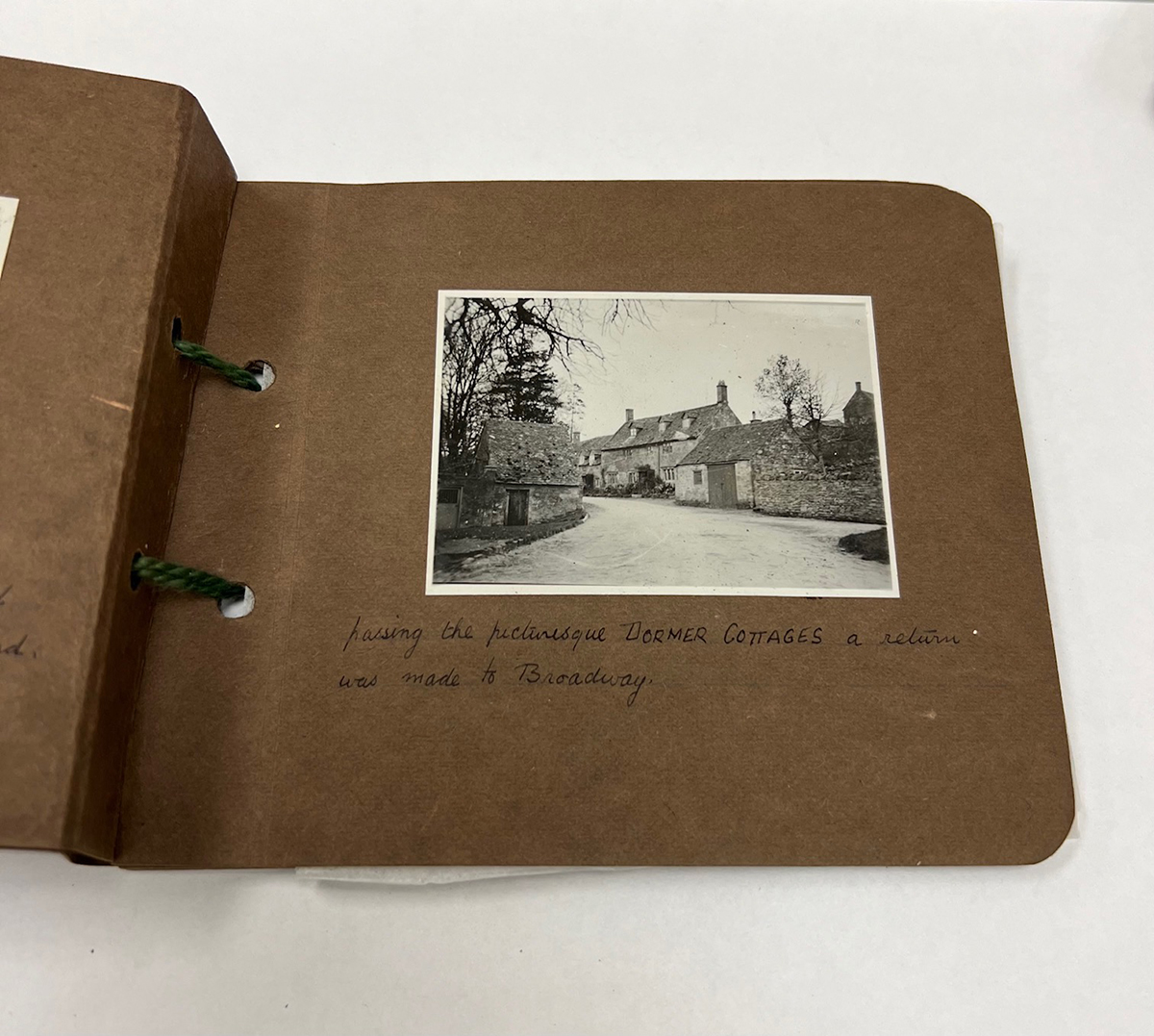

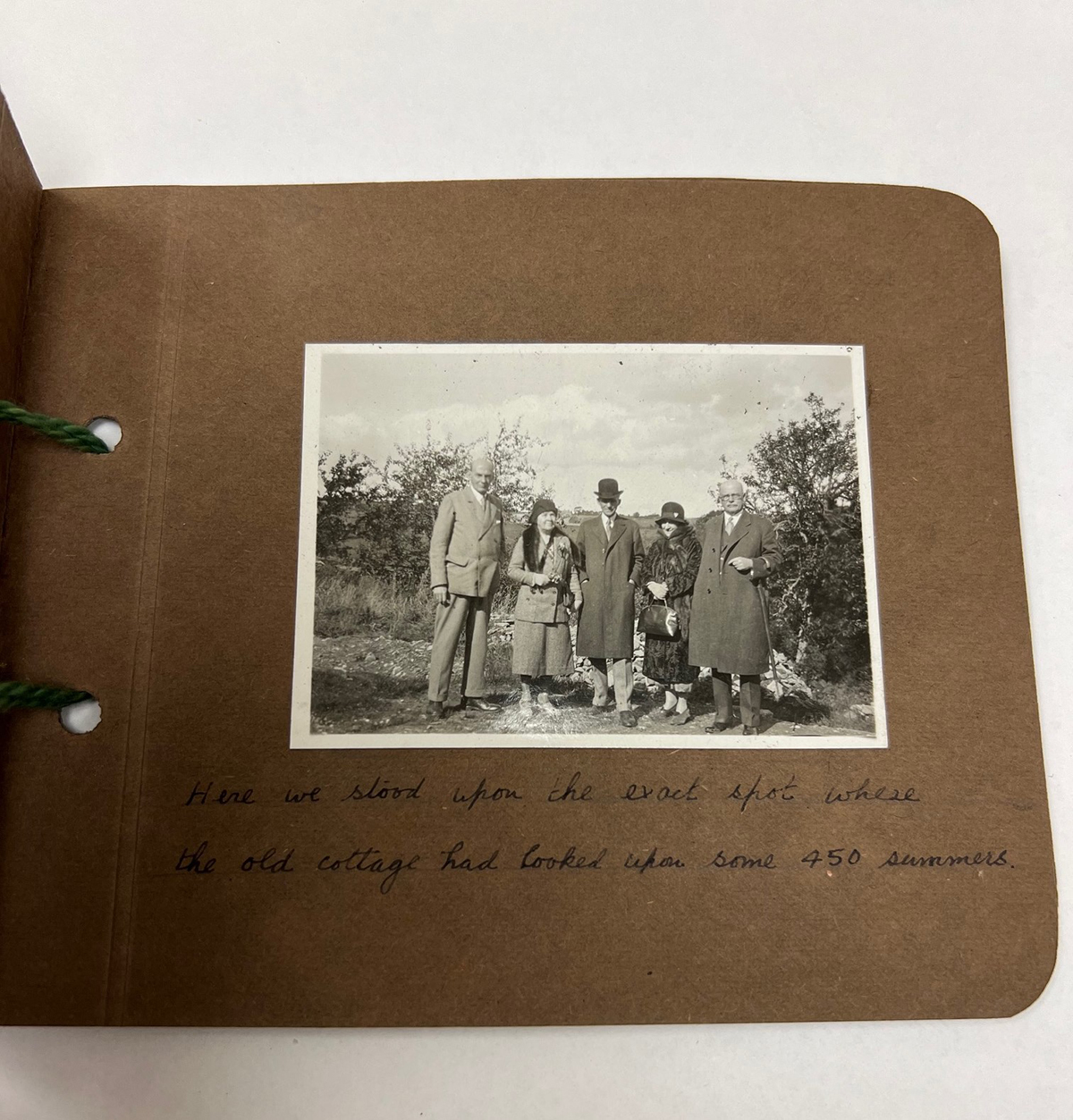

The album includes several snapshots of their visit culminating with a group photo at the former site of Cotswold Cottage. Clara's notes read like a short story as she describes the photos and recounts details.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara's diary entries with descriptions of cities and historic sites she encountered are valuable to historians looking for written records of landscapes altered by wars and other major events. Her words help us understand Clara Ford as a historical figure, but they also help us understand a location as it stood at that moment in time.

We are grateful to have these valuable archival records, but it is fun to wonder how a modern Clara may have documented her travels. Perhaps a post like this...

If you have any questions or would like to learn more about our collections, please contact the Benson Ford Research Center at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Lauren Brady is a reference archivist at The Henry Ford.

Edsel Ford, Ford family, Henry Ford, Clara Ford, by Lauren Brady

Frank Kulick: Early Ford Racer

Frank Kulick sitting in a 1910 Ford Model T race car. / THF123278

Frank Kulick (1882–1968) was a lucky man who beat rivals and cheated death on the race track. But his greatest stroke of luck may have been being in the right place at the right time. Born in Michigan, Kulick started his first job—in a Detroit foundry—at age 12. He was listed as a spring maker in the 1900 census. But in 1903 he was working for Northern Manufacturing Company—an automobile company founded by Detroit auto pioneer Charles Brady King.

That’s where Frank Kulick met Henry Ford.

Ford stopped by Northern to borrow a car. Impressed with young Kulick, Ford lured him to his own Ford Motor Company, where Kulick signed on as one of Ford Motor’s first employees. Kulick was there at Lake St. Clair in January 1904 when Henry Ford set a land speed record of 91.37 miles per hour with his “Arrow” racer. Not long after, Ford told Kulick, “I’m going to build you a racing car.” By that fall, Frank Kulick was driving to promote Ford Motor Company on race tracks and in newspapers.

Frank Kulick scored his early victories driving this four-cylinder Ford racer. Its engine consisted of a pair of two-cylinder (1903) Model A engines mated together. / THF95388

Kulick went head-to-head with drivers who became legends in American motorsport—people like Barney Oldfield, whose cigar-chomping bravado set the mold for racing heroics, and Carl Fisher, who established Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1909 and the Indianapolis 500 two years later. Kulick firmly established his credentials with an improbable win at Yonkers, New York, in November 1904. Through skillful driving in the corners and a bit of good luck (which is to say, bad luck for his competitors), Kulick’s little 20-horsepower Ford pulled out a win against a 90-horsepower Fiat and a 60-horsepower Renault. Kulick covered a mile in 55 seconds—an impressive racing speed of 65 miles per hour.

Frank Kulick (second from right) and Henry Ford (third from left) were photographed in New Jersey with the Model K racer in 1905. / THF95015

Frank Kulick’s four-cylinder, 20-horsepower car was superseded in 1905 by a larger car with a six-cylinder, 60-horsepower engine. It was one of a series of cars using engines based on the six-cylinder unit that appeared in the Ford Model K. The bigger engine did not bring better results. Henry Ford himself drove one of the cars twice in the summer of 1905, chasing new land speed records on the New Jersey beach. But the car came up short each time.

With Kulick at the wheel, Ford tried again for a record at Ormond Beach, Florida, in January 1906—this time with the six-cylinder engine improved to 100 horsepower. But Kulick had trouble with the soft sand, and he managed no better than 40 miles per hour on the straightaway. (The record was broken at the Ormond Beach event—but by a steam-powered Stanley that hit 127.66 miles per hour.)

The end of the road for Ford’s six-cylinder racers nearly ended Frank Kulick’s career—and his life. It happened in October 1907, on the one-mile oval at the Michigan State Fairgrounds near Detroit. Kulick was trying to lap the dirt track in fewer than 50 seconds—a speed better than 72 miles per hour. His latest car was dubbed “666”—a name that simultaneously called attention to its cylinder count and paid homage to Henry Ford’s earlier “999.” In retrospect, that nefarious name was a bad omen.

Miraculously, Frank Kulick survived this crash in 1907, but it left him with a broken leg and a permanent limp. / THF125717

As Kulick was going through a turn on the fairgrounds oval, his rear wheel collapsed. Car and driver went careening off the track, through the fence, and down a 15-foot embankment. When rescuers arrived, they found Kulick some 40 feet from his wrecked racer. He was alive, but with his right kneecap fractured and his right leg broken in two places. Frank Kulick survived the crash, but his injuries healed slowly and imperfectly. He wore a brace for two years, and he walked with a limp for the rest of his life—his right leg having come out of the ordeal 1 ½ inches shorter than his left leg. The “666” was repaired, but it never competed again.

Henry Ford was horrified by Kulick’s accident, and he very nearly swore his company off racing for good. It wasn’t until 1910 that Kulick competed again under the company’s colors. By then, Ford Motor Company wasn’t building anything but the Model T, so Kulick naturally raced in a series of highly modified T-based cars. Arguably, his first effort in the renewed campaign was more show business than sport. Kulick went to frozen Lake St. Clair, northeast of Detroit, that February to challenge an ice boat. He easily won the match and earned quick headlines for the Model T.

Kulick posed in a Model T racer at the Algonquin Hill Climb, near Chicago, in 1912. / THF140161

Over the next two years, Kulick and his nimble Model T racers crossed the country competing—and frequently winning—road races and hill climbs. Despite Kulick’s success, Henry Ford remained lukewarm on racing. Ford Motor Company built nearly 70,000 cars in 1912 and still struggled to meet customer demand, so it certainly didn’t need the promotion—or problems—that came with an active motorsport program. Kulick later recalled that, after a race at Detroit in September 1912, Henry pulled $1,000 in cash from his pocket and told Frank, “I’ll give you that to quit racing.” Despite the generous offer (almost $30,000 in today’s dollars), Kulick continued a bit longer.

Frank Kulick may have started having second thoughts the next month. While practicing for the Vanderbilt Cup road race in Milwaukee, he grew concerned about the narrow roadway. There wasn’t enough room to pass another car without dipping into a ditch, so Kulick protested and dropped out of the contest. His concerns proved well founded when driver David Bruce-Brown was killed in the next round of practice.

It was the 1913 Indianapolis 500 that finally changed Kulick’s career path. Then in its third running, the Indy 500 was well on its way to becoming the most important race in the American motorsport calendar. Henry Ford was determined to enter Kulick in a modified Model T. But Indy’s rules specified a minimum weight for all entries. The Ford racer weighed in at less than 1,000 pounds—too light to meet the minimum. Indy officials rejected the modified T, and a frustrated Henry Ford reportedly replied, “We’re building race cars, not trucks.” With that, there would be no Ford car in the Indianapolis 500—in fact, there would be no major factory-backed Ford racing efforts for 22 years.

Kulick’s later career involved more genteel assignments, like driving the ten millionth Ford on a coast-to-coast publicity tour in 1924. Here, he takes a back seat to movie stars Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. / THF134645

Frank Kulick’s racing days were over, but he remained with Ford Motor Company for another 15 years. His assignments varied from research and development to publicity. In 1924, Kulick was charged with driving the ten millionth Ford Model T on a transcontinental tour from New York to San Francisco. Three years later, Kulick was called on to help celebrate the 15 millionth Model T. This time, rather than driving it across the country, Kulick—as one of Ford Motor Company’s eight senior-most employees—had the honor of helping stamp digits into the engine’s serial number plate. It was perfectly fitting that, as someone who’d done so much to promote the Model T through racing, Kulick was there to make his mark on the ceremonial last T. Kulick left Ford not long after that. He had done well investing in real estate, which afforded him a comfortable retirement.

Frank Kulick passed away in 1968. He survived to see Ford Motor Company achieve its great racing triumphs at Indianapolis and Le Mans during the “Total Performance” era. He also lived long enough to sit for an interview with author Leo Levine, whose 1968 book, Ford: The Dust and the Glory, remains the definitive history of Ford racing in the first two-thirds of the 20th century. Levine wrote a whole chapter on Frank Kulick—but then, Frank Kulick wrote a whole chapter in Ford’s racing history.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Remembering Al Unser, Sr. (1939-2021)

- Eight Questions with Vaughn Gittin, Jr.

- Race Cars of Driven to Win

- 2016 Ford GT Full-Size Clay Model, 2014

Michigan, Model Ts, Indy 500, cars, by Matt Anderson, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford, race cars, race car drivers, racing

Ackley Covered Bridge in Pennsylvania

Few visitors to Greenfield Village cross Ackley Covered Bridge realizing the significance of the structure surrounding them. It is one of the oldest surviving covered bridges in the country, and considerable thought went into its overall design. Covered bridges have long been stereotyped as quaint, but the reason behind their construction was never charm or shelter for travelers. The sole function of the “cover” was to protect the bridge’s truss system by keeping its structural timbers dry.

Built in 1832, Ackley Covered Bridge represents an early form of American vernacular architecture and is the oldest “multiple kingpost” truss bridge in the country. This structural design consists of a series of upright wooden posts with braces inclined from the abutments at either end of the bridge and leaning towards the center post, or “kingpost.” It is also a prime example of period workmanship and bridge construction undertaken with pride as a community enterprise.

This map of Washington County, Pennsylvania, shows the original site of Ackley Covered Bridge (bottom left). / THF625813

Ackley Covered Bridge was constructed across Wheeling Creek on the Greene-Washington County line near West Finley, Pennsylvania. The single-span, 80-foot structure was built to accommodate traffic caused by an influx of settlers. Daniel and Joshua Ackley, who had moved with their mother to Greene County in 1814, donated the land on which the bridge was originally constructed, as well as the building materials. More than 100 men from the local community, including contractor Daniel Clouse, were involved in the bridge’s construction. Like most early bridge builders in America, they were little known outside their community. But their techniques were sound, and their work stood the test of time.

Initial community discussions about the bridge included a proposal to use hickory trees, which were abundant in the region, in honor of President Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson. Instead, they settled on white oak, which was more durable and less likely to warp. The timber came from Ackley property a half mile south of the building site. It was cut at a local sawmill located a mile south of the bridge. Hewing to the shapes and size desired was done by hand on site. Stone for the abutments was secured from a quarry close by.

Ackley Covered Bridge replaced an earlier swinging grapevine bridge, and it may soon have been replaced itself if settlement and construction in the region had continued. Instead, the area remained largely undeveloped for several decades. This, along with three roof replacements (in 1860, 1890, and 1920), helped ensure the bridge’s survival.

Ackley Covered Bridge at its original site before relocation to Greenfield Village, 1937. / THF235241

Plans to replace the more than 100-year-old structure with a new concrete bridge in 1937 spurred appeals from the local community to Henry Ford, asking him to relocate Ackley Covered Bridge to Greenfield Village. Ford sent representatives to inspect, measure, and photograph the bridge before accepting it as a donation from Joshua Ackley’s granddaughter, Elizabeth Evans. She had purchased the well-worn structure from the state of Pennsylvania for $25, a figure based on the value of its timber. Evans had a family connection to one of Ford’s heroes, William Holmes McGuffey. McGuffey’s birthplace, already in Greenfield Village, had stood a mere seven miles from the original site of Ackley Covered Bridge—an association that likely factored in Ford’s decision to rescue the structure.

Dismantling of Ackley Covered Bridge began in December 1937. Its timbers were shipped by rail to Dearborn, Michigan, and the bridge was constructed over a specially designed pond in Greenfield Village just in time for its formal dedication in July 1938.

Ackley Covered Bridge after construction in Greenfield Village, 1938. / THF625902

This post was adapted by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford, from a historic structure report written in July 1999 by architectural consultant Lauren B. Sickels-Taves, Ph.D.

Michigan, Dearborn, Pennsylvania, 1830s, 19th century, travel, roads and road trips, making, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Saige Jedele, by Lauren B. Sickels-Taves, Ackley Covered Bridge

Spotlight on Master Presenter Cindy Melotti

Cooking in the Ford Home. / Photo by Ken Giorlando

Cindy Melotti is currently master presenter and house lead at the Ford Home, which is often considered to be the intellectual center of Greenfield Village. I had the honor of working alongside her in the Ford Home and Daggett Farmhouse in 2012. Cindy captivates guests with her energetic and authentic storytelling, and I’m delighted to chat with her about 17 years of adventures at The Henry Ford.

What did you do before you worked at The Henry Ford? And why were you interested in working here?

I worked at Wyandotte Public Schools as an elementary school teacher for 35 years, mostly in the upper elementary grades. Not surprisingly, I taught language arts and social studies. It was interesting in that we didn't really use textbooks. We, like Henry Ford, thought history should not be just about memorizing generals, dates, and wars. So I taught my social studies classes in a more contextual way. We learned about people in the times that they lived, and how they lived, not just timelines and titles.

I had always wanted to work at The Henry Ford. After retiring from Wyandotte Public Schools and taking a couple years to think about it, I decided that I was going to try and get a job here. So I went to a job fair. I didn't even tell my husband and my family that I was going, because I was afraid I wouldn't be accepted. This was actually the first time I wrote a resume. And it was the first time I applied for a job since I got my teaching position, which was when Lyndon Baines Johnson was president! I was as scared as a 16-year-old sitting there waiting to be interviewed. Despite there not being any historical presenter positions open, [The Henry Ford staffer] Mike Moseley recognized that I had the potential to be a good presenter. Thankfully, I got an interview with Cathy Cwiek, our former manager of domestic life. I got the job and was in training within a week.

Preparing food at Edison Homestead. / Photo by Ken Giorlando

Do you have any highlights of your teaching career or adventurous experiences that you’d like to share?

Well, a person of my age very typically followed the dictates of society at that time. I always wanted to be a teacher. I was fortunate to be able to go to Wayne State University. My parents were a one-income family, and we didn’t have a whole lot of money. So I considered myself lucky that I got hired by the school district where I student taught. I worked there for 35 years.

The brightest highlights for me are the memories of the children and their families. Some I still associate with and frequently talk to. I am still delighted to find out that I had a really big impact on a former student’s life. Once I became friends with a woman whose best friend from college remembered me from the fourth grade. She said that her friend had broken her arm near the start of the year, so she wasn’t able to write. This student was already ashamed of her handwriting, as she had been previously criticized in another class. She was telling our mutual friend that she had been so tense about this issue. And she said that I saved her life by suggesting she use a typewriter!

After all this time, this former student was so encouraged by my advice, she was still talking about it as an adult to her best friend. To think that I made that much difference in this this child's life! It was so wonderful that this story got back to me.

And in another instance on Facebook, one woman made a comment to me: “I just wanted to let you know that you were the most important teacher I ever had.” Never would I have expected that. It's amazing. Now, it was hard work. It was a lot of fun, and I enjoyed myself, but I never really thought about the impact I had on people's whole lives.

But those are the kind of things when you asked about adventurous experiences, that was the adventure. I guess the adventure was working with people and hopefully making an impact on their lives and making their lives better—making them better to fit their lives.

And of course, there's part of that that goes into presenting at The Henry Ford too. Because every guest that you interact with, you want their experience to make a difference. You want them to be different and more open to our stories when they leave, than when they came in.

Which historic homes and what programs have you worked at?

When I started in 2005, everyone in domestic life started at Daggett Farm. You also worked in uniform at the Noah Webster Home, Hermitage Slave Quarters, and the Mattox [Family] Home. You had to work your way into the Susquehanna Plantation and the Adams [Family Home]. Well, I never quite got to do that before they made me the house lead at the Ford Home, which was I think was 2007–2008. I eventually presented at Susquehanna Plantation. As I became a master presenter, they could schedule me in any home, really. I always wanted to work at Adams House, and I never got in there before it was closed for renovation. I can work at Firestone Farmhouse. And I’ve worked at the Edison Homestead.

I’m trying to think of the clothes I have in my closet, which period clothes are hanging there? So, it's Daggett, Edison, Ford Home, and Firestone, which are the buildings where we dress in period clothing. And then I wore the field uniform at Webster, Hermitage, and Mattox. I have also worked on a number of programs with the Henry Ford Academy.

Preparing food at Daggett Farm. / Photo by Ken Giorlando

What is your favorite home to work in?

I've been house lead at the Ford Home for over 10 years, so that’s a contender. I’ll always love Daggett Farm, and I’ll always say, once a Daggetteer, always a Daggetteer. But I really can’t say what my favorite building is.

Now with the Ford Home, people think it's strange when I'm elsewhere in the village besides the Ford Home. I'm like a fence post almost. I put in a lot of work at that house when they made me the lead, and I’m seen here most often.

The Ford Home was categorized differently over the years. It was part of the Ford Motor Company group when I started as a presenter. And then it went to the domestic life group. So the story of the home needed a little extra attention by then. We needed to work on the stories, and make sure they were authentic and correct. So that's when Cathy Cwiek asked me to upgrade the presentation at the building.

For about three or four years, anyone who presented there, if they were asked a question that wasn't in the manual, we wrote it down and researched it. That's why the manual is now very thick. Because when guests go into the Ford Home, they're not just asking about Henry Ford growing up in the house. There are so many different aspects of that house that are asked about and you want to be able to answer. Ford Home certainly demands a lot of work. But as much as I love Daggett, I really cannot pick a favorite.

Front of Ford Home. / Photo by Ken Giorlando

What is the relevance of the Ford Home within the village? I’ve considered it to be the intellectual center. Do you see it this way as well?

Well as Cathy Cwiek said when I became the house lead, the Ford Home is the cornerstone of the village. We needed to tell a more full story. We really want to have the best stories told there. In one perspective, Henry Ford restored and saved his childhood home to memorialize his beloved mother. His home played a big role in eventually developing the village and the museum itself.

And then there’s the perspective that you have this space that when you sit in it, you must realize the brilliant ideas that bounced off those walls from a little boy who eventually used those ideas to change the world. And when you think of that, it's awe-inspiring. The key for every presenter in any home is that it isn't about the house—it's about the people who lived in it and their ideas.

Presenters only have so much time to try and tell these stories as guests go through the house. You just never know what's going to interest the guests as they come in. You must have your background and information ready for basically any question. Plus, in many cases, the Ford Home is the first house that our guests visit. As they enter the village, they either go to the left to Firestone Farm, or they go to the right to the Ford Home.

A good presentation can set the tone for every guest’s entire day, especially for those who have never been here before. They’re not always aware of the scope of our campus. They might say: I have an hour, what should I see? In many ways, we are the ambassadors for the whole village at that point, and we can set the tone for an international guest or someone from out of state. We can set the tone for their whole day. We want to make sure the tone is one of positiveness, curiosity, interest, and amazement of the stories we have to share.

I know you have a lot of favorite stories about what you most like about working here, but perhaps you can pick one right off the top of your head?

If I can pick out a little snapshot, it would be during Holiday Nights [in Greenfield Village] in the Ford Home. I was in the dining room in the back, and a three-generation family came in. They were in the parlor up front where we've got the tree up with music and lighting, and I'm listening to their 10-year-old boy who’s giving my presentation! And he is spot on!

When the family came through the house to me, I said to the boy: “wow, you really did a good job telling our story.” He said: “of course, I was here on a field trip this year.” I love to tell this story because despite this kid having access to all the bells and whistles of electronics and technology—this kid learned it from our field trip program. I’m proud to say we’re still reaching an audience and, yes, we have a future and a purpose. This little boy is telling the story, and his whole family is interested.

There are so many instances when I’m very happy to see guests leave the building with a look as if they’re saying: “wow, I need to think about this.” I try my best to encourage them to understand that, as much of what we thought was true in history, there are preconceptions that aren’t always true, and you need to think in terms of the time and the setting of the place to understand what was going on.

This leads me to my cheese straw story. Before it was closed for renovation, the Adams House made these cheese straws, which were a specific recipe for that house. They could not be made at the Ford Home. When they closed Adams, we were now able to make them at the Ford Home. I had heard how good these cheese straws were and I was excited. We made the first batch, and after they came out of the oven, we just kind of sat there and looked at them. They were these flat, long things. I thought they were going to turn out puffier. They didn't rise at all. We realized that they were named, not after a modern sipping straw, but after actual straw from a field. We were completely off the mark.

When we look back at history, we need to ask ourselves: if my modern perception doesn’t allow me to understand what a cheese straw was, how can I use my modern perception to say, understand our Civil War? How do we understand a single event back then when we’re looking through our modern eyes and not going further? We encourage that “aha” moment that opens your mind for the stories that are accurate, instead of stories based in preconceptions or fantasy.

Spinning wool at Daggett Farm. / Photo by Ken Giorlando

What skills have you picked up and learned how to do and demonstrate at the village?

Well, there are textile skills like carding, spinning, and dying wool that I’ve done at Daggett. I did do some weaving on the big old colonial loom when that was set up inside Daggett. But I only had a little experience on that because I was so short. I had to jump down to change the bottom pedals, so it would take me an awfully long time. But I did work successfully on the treadle wheel that you pump with your foot. That's very difficult to do, as I was spinning with linen. Linen is a whole different process compared to wool.

Also, during the first year I was here, we had candle dipping over in the Liberty Craftworks area, near where the Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass is now. We wore field uniforms. We were considering it to be a craft at the time, as opposed to it being part of a culture or time period. That was my first experience with it. Candle dipping was a lot cooler in period clothing and more fun to set up under the trees next to Daggett or the [William Holmes] McGuffey Birthplace, where the activity fit with the history of the building.

Screenshot of 1876 centennial program at the Ford Home for WDIV.

Along with this WDIV segment, and a previous video promoting Fall Flavor making an 1860s apple cake, you were most recently involved in a video celebrating the Fourth of July in 1876 outside the Ford Home recorded during the pandemic. Could you tell us how this came about?

Yes, it was 2020 during COVID, and we were unable to host Salute to America. Over the years, we had developed a Fourth of July program specifically for the 1876 centennial at the Ford Home. And I was asked if I could do a video presentation of this program. I didn’t know what the filming was for at the time. I thought it was for a kind of video that we do for in-house purposes.

We filmed this on June 16. We didn't open the village up until July 2. And I came in early to work to do the video. It was basically a sample of the program we would do for a Fourth of July holiday at the Ford Home—a few of the games and the food that we’d make. So it was fun.

It wasn't until after filming that I learned that this was not being used for our website. I learned that it was for a WDIV Fourth of July virtual celebration! It was a surprise for sure, but we are presenters. And just because there's a camera there doesn't change the energy and information you give. You know, it's what we do.

So WDIV aired this the following Friday night at 8 p.m., and they broadcast snippets of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra playing, along with my Ford Home centennial program. It was hosted by Tati Amare, who I met previously. Of course, they filmed theirs, and I filmed mine, and it was only on television that we met, so I couldn't say hello again. But they pieced it all together as a virtual presentation for the holiday on WDIV. I was honored to be a part of it.

So you’ve been in many pictures and videos. Can you think of any other fun or unusual stories regarding getting your picture taken?

When I was going through training in 2005, and we needed to sign the waiver to give permission for The Henry Ford to use our photographs, guess who said: “why would anybody want to take my picture?” Ironically, my picture has been in so many places. It’s been amazing. I knew within a month that I asked this that I had made a silly statement, because I realized that guests are taking our pictures all the time and sending them all over the world. Presenters are world travelers in that way.

I remember presenting at Edison Homestead one day during our noon meal, and an Asian guest came in and he wanted his picture taken with us. We handed him a cup to hold, to make it look like he was having a meal with us. A young couple also came in and they graciously took this photo of us. I turned to the gentleman and asked where our picture was going. And he said it was going to Beijing, China. Well, I didn't want the young couple to feel left out, so I asked where they were visiting from. The young man said Wyandotte, Michigan—and then he said that I had been his teacher! This is the experience of presenter. You can have a visitor from Beijing, China, and also someone that you knew years before in your classroom. Like, how does this happen?

Barney Litogot in 1865. / THF226856

Did you have any experiences at the Ford Home of guests reaffirming stories of Henry Ford’s life? Any other surprising interactions with guests?

When I first started working at the Ford Home around 2007, I used to get guests who had firsthand memories of the Fords, just little stories. People who had funny interactions with the Ford family, for instance, neighborhood kids who would be playing on the farm, when it was in its original location, and they’d get caught.

I remember there was an elderly man who would take walks in the village in the morning, and he told me once that he used to drive by the Ford Home every day on his way to work when it was located on Ford Road. And sometimes he’d see Henry Ford walking around. He’d be picking vegetables and fruits to put in baskets that would be placed on the porches of neighbors who didn’t have enough food. I heard stories like that all the time. But all of a sudden, kind of recently, I realized those guests are gone, that generation is gone.

So the guest in 2009 who was 78 years old when he told me this story about getting caught by Henry Ford—he said it was actually his brother's fault. He also told me about the time the Ford family was moving the house to the village, and he got on his bike and followed it down the road. I have a pile of stories that were told to me. You come to think that after hearing the same story over and over again, that there is truth to them, and that's exciting.

I have at least twice had guests tell me stories that I've read in my research, which is amazing. There’s the story of the Vagabonds—Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and John Burroughs—when they were driving around Kentucky or Tennessee. There were no roads, so they had to follow river beds and try to find open areas to drive. They were scouting and looking for forests and sources of wood, because they needed wood to build Model Ts. Henry Ford owned many forested areas for that purpose.

And to paraphrase a story, the Vagabonds were driving through the wilderness, and their car got stuck. A farmer came by and used his horse to get them out. As the story goes in the research that we have in our Ford Home manual, Henry Ford introduces himself to the farmer. Thomas Edison introduces himself to the farmer. Harvey Firestone was there, and he introduces himself. And then John Burroughs who has this long white beard, right? He says: “well, you know, if you want to believe those guys then you can believe I’m Santa Claus!” Now, there are other ways people have told this story, of course.

Back to the Ford Home, I’m presenting and there's a three-generation family who comes in and we're talking about the house and the history, and the man said: I have a Ford story. He said: “my great grandfather had one of the first Ford dealerships (around Kentucky or Tennessee) and my grandfather told me the story about how Ford and his friends got stuck in a riverbed and one of our local farmers with horses pulled them out.”

The guest went on to explain that it wasn't long after this incident happened that a Ford tractor was delivered to the dealership to be given to the farmer who had helped them out. Isn't that amazing? I was delighted then to tell him and his family about the Vagabonds introducing themselves to the farmer. So where else could you ever present where you hear a direct story from a family that you had read about in a book as part of your research? You know, what's not to like about that?

One of the most emotionally powerful days I ever worked in the Ford Home was on the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's death. In the museum, they took Lincoln’s chair out and put it up on a platform behind the cornerstone. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to see it. However, there is a connection to Lincoln's death at the Ford Home. We have a photo in the sitting room of Barney Litogot, Henry Ford’s uncle on his mother, Mary Litogot’s, side. Barney was in the 24th Michigan Volunteer Infantry, part of the famed “Iron Brigade,” serving as an honor guard on the train carrying Lincoln to his final resting site in Springfield, Illinois.

I told Barney’s story to the guests who had already been to the museum and seen the chair. I really wish that I could have had a camera taking pictures of people’s expressions, because they were so moved, even crying. The museum exhibit, along with Barney’s story, was so emotional. It was just so special to be a part of that immediate tie-in to that event in our country's history, and I don't know that you could have felt too much closer. Presenting an artifact, a story, an emotion—that is what we do best.

I really love the story of Barney, and I’ve visited his burial site at Sandhill Cemetery on Telegraph Road near the I-75 ramp in Taylor, Michigan. And I always wave as I drive by and say: “hi, Barney”!

Yes, I do too! My husband doesn’t even think I’m weird anymore, he’s used to it! I always say hi to Barney. Speaking of the Litogots, the Litogot family had a reunion in the village a few years ago. They visited the Ford Home, and I got to talk to them for about 10–15 minutes. And they were talking about Uncle Barney as he was a true part of their family. It was really cool. You just never know who's going to walk through the door.

I've had fun remembering all these stories and experiences, and it's really hard to rank anything when you've been doing it for so long. But every experience and interaction deals with a relationship with guests and co-workers, and that's where the good stuff comes from. When you look over everything that goes on at The Henry Ford, it's a wonderful job, and it's why people get hooked.

Amy Nasir is Digital Marketing Specialist and former Historical Presenter in Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford.