Monthly Archives: June 2021

Motor Muster Returns for 2021

We spotlighted racing at Motor Muster for 2021. This 1953 Oldsmobile 88 stock car, brought to us by the R.E. Olds Transportation Museum, fit the theme perfectly. / Image from The Henry Ford’s livestream

Gearheads and automobile aficionados had reason to celebrate as Motor Muster returned to Greenfield Village on June 19 and 20. Like so much else, last year’s show was canceled in the wake of COVID-19. But with restrictions eased and a brighter situation all around, we returned in 2021 for another memorable show. We also welcomed a new sponsor. For the first time, this year’s Motor Muster was powered by Hagerty.

It’s no surprise, given the recent opening of our exhibit Driven to Win: Racing in America Presented by General Motors, that our Motor Muster spotlight was on racing. Yes, we had competition cars in the mix, but we opened the celebration to include production cars inspired by racing events, locations, and personalities. Whether it’s a model like Bonneville or a make like Chevrolet, racing names have appeared on automobiles from the start.

The Henry Ford’s 1953 Ford Sunliner convertible, official pace car at that year’s Indianapolis 500. / Image by Matt Anderson

As always, we brought out a special vehicle from The Henry Ford’s collection. Many of our prominent competition cars are in Driven to Win, but we found a perfect match for the theme in our 1953 Ford Sunliner. The convertible served as pace car at the 1953 Indianapolis 500, driven by William Clay Ford in honor of Ford Motor Company’s 50th anniversary. In addition to its decorative lettering (with flecks of real gold in the paint), the pace car featured a gold-toned interior, distinctive wire wheels, and a specially tuned V-8 engine rated at 125 horsepower.

From the GM Heritage Center, a 1955 Chevrolet from the days when stock cars were still largely stock. / Image by Matt Anderson

Our friends at General Motors got into the spirit of things by lending an appropriate car from the GM Heritage Center collection. Their 1955 Chevrolet 150 sedan is a replica of the car in which NASCAR driver Herb Thomas won the 1955 Southern 500 at Darlington Raceway. Thomas’s car benefited from Chevy’s new-for-’55 V-8 engine which, with the optional PowerPak dual exhausts, was rated at 180 horsepower. The Chevy small-block design went on to win more NASCAR races than any other engine.

Historical vignettes were in place throughout Greenfield Village—everything from a Civilian Conservation Corps setup from the 1930s to a patriotic bicentennial picnic right out of the mid-1970s. Even the Herschell-Spillman Carousel got into the spirit of the ’70s, playing band organ arrangements of the hits of ABBA. (I wonder if that 1961 Volvo at the show ever drove past the carousel. What a smorgasbord of Swedish splendor that would’ve been!)

Our awards ceremony included prizes for unrestored cars, like this 1941 Ford Super Deluxe Fordor. / Image by Matt Anderson

As always, we capped the weekend with our awards ceremony. Our popular choice voting allows visitors to choose their favorite vehicles from each Motor Muster decade. Top prize winners this year included a 1936 Hupmobile, a 1948 MG TC, a 1958 Chevrolet Corvette, a 1969 Plymouth Barracuda, and a 1976 Ford Econoline van. The blue ribbon for motorcycles went to a 1958 Vespa Allstate, and the one for bicycles to a 1952 JC Higgins bike. For commercial and military vehicles, our top vote-getters were a 1937 Ford 77 pickup and a 1942 White M2A1 half-track, respectively. We also presented trophies to two unrestored vehicles honored with our Curator’s Choice award. For 2021, those prizes went to a 1936 Buick Victoria Coupe and a 1967 Chevrolet C/10 pickup.

It was a longer-than-usual time in coming, but Motor Muster 2021 was worth the wait. Everyone was in good spirits and enjoying the cars, the camaraderie, and the chance to enjoy a bit of normalcy after a trying year. Let’s all do it again soon.

If you weren’t able to join us at Motor Muster this year, though, you can watch parts of the program right now. Our popular pass-in-review program, in which automotive historians provide commentary on participating vehicles, returned this year with a twist. We livestreamed portions of the program so that people who couldn’t attend Motor Muster in person could still enjoy some of the show. Enjoy those streams below, or use the links in the captions to jump straight to Facebook.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2020s, racing, race cars, Motor Muster, Greenfield Village, events, cars, by Matt Anderson

Baseball, 1880s Style

Welcome to the 1880s. Baseball fever is sweeping the country! Urban centers boast professional teams of paid, recruited players, like the Detroit Base Ball Club pictured on the trade card below, part of the National League from 1881 to 1888. (The Detroit Tigers were created in 1901, as part of the newly organized American League.) The Detroit Base Ball Club is gaining some notoriety. They'll win the pennant (the forerunner of the World Series) in 1887, beating the St. Louis Browns of the American Association in 10 out of 15 games.

Trade Card for the Detroit League Base Ball Club, Sponsored by "Splendid" Plug Tobacco, P. & G. Lorillard, 1886 / THF225148

Chief among the team's heroes is star catcher Charley Bennett (pictured upper right). Charley is the first professional-league catcher to wear a chest protector outside his uniform. Detroit fans so adore him that they will name their first official ballyard Bennett Park. Charley is the team's "muscle"; center fielder and team captain Ned Hanlon (pictured center) is its "brains."

The passion for baseball is equally evident in small-town America. Amateur clubs show up just about anywhere that nine men can agree on a time and place to practice. Games against rival towns and villages engender fierce local pride. Over in the village of Waterford, Michigan, some country lads have formed a team called the Lah-De-Dahs. Their exploits are well documented in the local newspaper. On September 2, 1887, local fans will smile to read, "George Wager is the best catcher in the township and of the Waterford nine; if he fails to catch the ball with his hands he will catch it with his mouth."

The back of the trade card features an ad for Lorillard’s “Splendid” plug tobacco, as well as the home and “abroad” schedules for Detroit. / THF225149

See the Lah-De-Dahs in Action

Would you like to see the Lah-De-Dahs in action? You can, every summer in Greenfield Village. Our own team borrows the look and playing style of an 1880s amateur baseball club like the original Waterford Lah-De-Dahs.

When you go to a Historic Base Ball in Greenfield Village game, you will notice some different baseball terminology. For example, instead of "batter up," the umpire will declare "striker to the line." When he notes "three hands dead," he simply means that the side is retired.

Visit a Historic Base Ball game this summer and learn some new terminology for yourself!

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This article was adapted from the May 1997 entry in our previous “Pic of the Month” online series.

19th century, 1880s, sports, Michigan, Historic Base Ball, Greenfield Village, events, Detroit, by Donna R. Braden, baseball

Operating the Marionettes in Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little Marionette Show at the A.B. Dick Company Exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623950

The A.B. Dick Company, a major copy machine and office supply manufacturer, wanted to draw a crowd to its 1939 New York World’s Fair exhibition. The company decided that a musical marionette show, Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little, was just the ticket. A.B. Dick selected Tatterman Marionettes, a high-quality touring company managed by Edward H. Mabley (1906–1986) and William Duncan (1902–1978). Mabley wrote the musical comedy and Duncan produced the show, staged at the entrance to the A.B. Dick display in the Business Systems and Insurance Building.

A.B. Dick Company Mimeograph Exhibit and Writer’s Cramp Marionette Show at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623944

Writer’s Cramp featured changes in communication technology from “the days of the cave man” to the efficient modern office mimeograph machine. Marionettes represented Miss Jones, the secretary, and Mr. Whalen, the executive, trying to rush distribution of important correspondence. Father Time helped inform Mr. Whalen of his good fortune at present (1939) by escorting him through millennia of changes, starting with Stone Age stenographers, and including tombstone cutting, monks with their quill pens, and typists with their typewriters. The play culminated with the unveiling of A.B. Dick Company’s Model 100 Mimeograph, “the World’s Fairest writing machine!”

Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little Marionette Show at the A.B. Dick Company Exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623948

Mabley and Duncan organized Tatterman Marionettes in Detroit, Michigan, in 1922, and had relocated to Cleveland, Ohio, by 1930. They established a reputation through high-quality performances to a range of audiences.

Panel 4 of promotional material, “A Modern Adult Program and a New Children’s Program for the Tatterman Marionettes,” 1931-1932 / THF623902

Edsel B. Ford contracted with the company to perform for children in his home during March 1931. At that time, the always entrepreneurial Mabley recommended his and Duncan’s product, Master Marionettes, as “unusual gift favors” for the children attending that show.

Master Marionettes: Professional Puppets for Amateur Puppeteers, 1930-1940 / THF623904

Tatterman Marionettes’ reputation grew through work with the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago in 1934, where the company presented 1,300 plays. More World’s Fair performances followed. A.B. Dick Company and General Electric both contracted with Tatterman to produce marionette performances during the 1939 World’s Fair. General Electric’s Mrs. Cinderella promoted electrification as part of the modernization of Cinderella’s drafty old castle. (Libby, McNeill & Libby also featured marionette performances, and other corporations staged puppet shows.)

The A.B. Dick Company spared no expense to ensure a first-class production. Tatterman provided the marionettes and experienced operators, while industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague (1883–1960) prepared blueprints for a detailed stage set. Teague’s exhibit work for A.B. Dick and several corporations during the 1939 World’s Fair helped solidify his reputation as “Dean of Industrial Design.” The company invested in a conductor’s score by Tom Bennett (1906–1970), who would go on to join NBC Radio as staff arranger and musical director after the World’s Fair.

With the script finalized (February 27, 1939), experienced operators put the marionettes to work. After the World’s Fair opened on April 30, 1939, they delivered programs on a set schedule published in official daily programs. On Sunday, October 22, 1939, for example, Tatterman Marionettes performed 15 shows—at 10:20, 11:00, and 11:40 in the morning; at 12:20, 1:00, 1:40, 2:20, 3:00, 3:40 in the afternoon; and at 5:40, 6:20, 7:00, 7:20, 8:00, and 8:20 in the evening.

“Brighten Up Your Days,” Song for the Writer’s Cramp Marionette Show, New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623906

At the end of each Writer’s Cramp performance, A.B. Dick mass-produced the feature tune using a mimeograph machine and photochemical stencil. Attendants distributed this sheet music, calling attention to the modern conveniences: “Just a moment, PLEASE! The young lady right behind you is running off some of the words and music from our show—they’re for you to take home with our compliments. Don’t go away without your copy!”

The Tatterman marionettes from Writer’s Cramp featured prominently in World’s Fair promotional material intended to draw the attention of office outfitters to the Business Systems and Insurance Building. Their little stage set conveyed big lessons to the hundreds of thousands of professionals who flowed through the A.B. Dick exhibit at the New York World’s Fair.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Thanks to Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, for editorial guidance.

New York, 20th century, 1930s, world's fairs, popular culture, music, design, communication, by Debra A. Reid, advertising

On July 3, 1981, the New York Times published an article that would send shockwaves through the LGBTQ+ community across the country. Headlined “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” the article, which appeared not on the first page, but on page A20, reported the death of eight individuals, and that the cause of the outbreak was unknown. For LGBTQ+ individuals living in the affected areas, the article was more a confirmation of their fears than new information. And for many heterosexual people, it sparked trepidation and deepened discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community. Other smaller publications had published articles in the months preceding July 1981, and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, from the U.S. Center for Disease Control (now known as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), documented early cases of the epidemic in June. In the gay community, friends and loved ones were getting sick and many were dying. The alarm bell had been rung.

The Silence = Death Collective designed this poster prior to the formation of the ACT UP organization, but transferred ownership to ACT UP in 1987. / THF179775

Silence = Death

The Silence = Death poster has come to symbolize the early fight against the AIDS epidemic. It was borne of deep grief and an unrelenting desire for action. One evening in late 1985, after the loss of his partner from AIDS in November 1984, Avram Finkelstein met with Jorge Socarras and Oliver Johnston in a New York City diner to catch up. Although the AIDS epidemic was a constant, tumultuous undercurrent in the gay community in the mid-1980s, the topic was often coded or avoided. That night, Finkelstein recalls, AIDS was all the men discussed, which he found “exhilarating after so many years of secrecy.” They decided to form a collective, each agreeing to bring one additional person to their next meeting. Chris Lione, Charles Kreloff, and Brian Howard joined. These six men met regularly to discuss the epidemic’s impact on their lives—and to process, rage, mourn, and, eventually, strategize. Finkelstein illustrates these meetings in his book After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images: “There were animated conversations, always, and there was often hilarity. We were almost never mean, but we frequently fought. There was shouting, there was fist pounding, and occasionally tears…. Fear may have been the canvas for our conversations. But anger was definitely the paint.”

These conversations turned to action. Each of the men had an artistic background—the group was comprised of art directors, graphic designers, and a musician. They decided to create a political poster, hoping to inspire action from the community’s fear. According to Finkelstein, “the poster needed to simultaneously address two distinctly different audiences, with a bifurcated goal: to stimulate political organizing in the lesbian and gay community, and to simultaneously imply to anyone outside the community that we were already fully mobilized.” The group spent six months designing the poster—debating everything from the background color to the text before deploying the poster all over Manhattan by March of 1987.

The poster’s central graphic element is a pink triangle. It references and reclaims the pink triangle patches on concentration camp uniforms that homosexual men were forced to wear by the Nazi regime during World War II (lesbian women were given a black triangle). The pink triangles subjected the men to added brutality. The poster’s triangle is inverted, however, from the one used during the Holocaust. This was initially a mistake. Chris Lione had recently been to the Dachau concentration camp and recalled that the pink triangle he saw on exhibit pointed upward. However, the collective embraced the accident once it was discovered, reasoning that the inverted triangle was “superimposing an activist stance by borrowing the ‘power’ intonations of the upwards triangle in New Age spirituality.” The expansive black background created a meditative negative space that further emphasized the bright pink triangle and the white text below.

The tagline for the poster—“SILENCE = DEATH”—was quickly developed. It also soon became the name of the men’s group: the Silence = Death Collective. The equation references the deafening silence of the public and government-at-large—the New York Times didn’t give the AIDS crisis front-page coverage until 1983; President Ronald Reagan’s administration made light of the epidemic in its early years (the administration’s press secretary jokingly referred to the epidemic as the “gay plague” in 1982); and President Reagan didn’t address the AIDS epidemic publicly until September of 1985. The tagline also targeted the LGBTQ+ community, whose uncomfortable silence came at ultimate risk. Without discussion, education, and action about the AIDS crisis, many more people would die. By the end of 1987, over 47,000 people had already died of AIDS. Silence—quite literally—equaled death.

Artist and activist Keith Haring designed this poster, titled “IGNORANCE = FEAR, SILENCE = DEATH Fight AIDS ACT UP,” in 1989 for the ACT UP organization. It utilizes the “Silence = Death” tagline and the inverted pink triangle symbol initially created by the Silence=Death Collective. / THF179776

The Formation of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power)

At almost the same time that the Silence = Death Collective’s poster began appearing around Manhattan, playwright and activist Larry Kramer gave a legendary lecture at New York’s Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center on March 10, 1987. Kramer famously began this speech by telling the crowd that half of them would be dead within the year (due to the AIDS epidemic). He repeatedly asked the crowd “What are you going to do about it!?!” Kramer’s rage and urgency pushed the crowd towards actionable steps to combat the AIDS crisis. Within days, a group met that would become the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—or ACT UP. Around 300 people attended that first meeting, including some of the members of the Silence = Death Collective.

ACT UP quickly mobilized and became the political action group that many in the LGBTQ+ community—including the Silence = Death Collective—had envisioned. ACT UP was (and still is) “committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” On March 24, 1987, just two weeks after Larry Kramer’s lecture, the group held its first “action” when it protested pharmaceutical price-gouging of AIDS medication on Wall Street. Kramer had published an op-ed in the New York Times the day before, titled “The FDA’s Callous Response to AIDS,” which helped contextualize ACT UP’s protest in the media. ACT UP and its many chapters, subcommittees, and affinity groups kept pressure on the government for its inaction in the AIDS epidemic by frequently staging creative acts of civil disobedience and nonviolent protest.

“We had designed Silence = Death. ACT UP was about to create it,” Finkelstein wrote. The Silence = Death Collective gave the rights for the poster to ACT UP and it became a fundraiser for the organization. When this transition occurred, a few changes were made to the poster, including the correction of some minor errors (the “Food and Drug Administration” had been mistakenly referred to as the “Federal Drug Administration,” for example) and the addition of the “© 1987 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power” in the bottom righthand corner.

Over the last four decades, AIDS has taken the lives of men, women, and children, without regard to sexual orientation or race. However, the LGBTQ+ community has suffered the bulk of misinformation and discrimination related to the disease and done the difficult work to push direct action to end the AIDS crisis. The work of activists like the Silence = Death Collective, the members of ACT UP, and many others made treatment available to more people and curbed the spread of the disease. ACT UP broadened its mission to the eradication of AIDS at the global level and remains an active organization.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

New York, 20th century, 1980s, posters, healthcare, design, by Katherine White, art

The Columbus Buggy Company’s sprawling factory, depicted as it was in 1889. / THF124829

When we hear the name “Firestone,” our thoughts inevitably turn to motor vehicle tires, proving themselves where the rubber meets the road. It’s a bit surprising, then, to learn that members of the Firestone family were building horse-drawn vehicles decades before the first Model T turned a wheel.

Clinton Firestone, in partnership with the brothers George and Oscar Peters, established the Columbus Buggy Company in Columbus, Ohio, in 1875. The firm grew into one of the largest buggy manufacturers in the world. By 1900, it employed more than 1,000 people and operated branch offices throughout the United States.

Clinton Firestone was a first cousin to Benjamin Firestone. Benjamin was a prosperous farmer in Columbiana, Ohio, and the father to future tire magnate Harvey Firestone. (Greenfield Village visitors will recognize the brick farmhouse that Benjamin and Catherine Firestone called home.) After a stint selling patent medicines and flavor extracts, young Harvey went to work at his cousin Clinton’s buggy company in the early 1890s. Harvey Firestone bounced between bookkeeping and sales duties at branch offices in Columbus, Des Moines, and Detroit. He remained with the firm until 1896. Four years later, he established his own business selling rubber buggy tires—the famous Firestone Tire & Rubber.

Harvey Firestone, pictured here about 1920, worked at several Columbus Buggy Company branch offices throughout the Midwest. / THF124780

Working in sales, Harvey Firestone was a first-hand witness to one of the problems that led to Columbus Buggy’s demise. While the company offered well-built wagons priced around $100, a growing number of competitors, like Durant-Dort, offered similar-quality wagons for around $35. Some buyers continued to pay the premium for Columbus Buggy’s perceived prestige, but most were content to get a comparable vehicle elsewhere for one-third the price.

There was another problem too: the horseless carriage. Columbus Buggy tackled that challenge by introducing an automobile of its own in 1903. Despite a marvelous slogan—“A vehicle for the masses, not a toy for the classes”—the $750, ten-horsepower high-wheeler auto could not save the firm. Columbus Buggy Company went bankrupt in 1913.

Harvey Firestone, of course, did make a successful transition into the new motorized world. In 1906, Firestone Tire & Rubber secured its first contract to supply Ford Motor Company with automobile tires. That prosperous business relationship grew into a lifelong personal friendship between Harvey Firestone and Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford’s Columbus Buggy Company surrey.

In 2015, The Henry Ford acquired a beautifully-restored Model 300½ four-passenger surrey manufactured by Columbus Buggy. Open-sided surreys were a favorite warm-weather conveyance in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. (Ask anyone who’s seen Oklahoma!) Given the Columbus Buggy Company’s family ties, the surrey was an ideal fit for programming use at Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village. A surrey of this style and quality would have been within the means of an upper middle-class family like the Firestones—the sort of carriage they might have taken to church on Sunday, or to town on social calls.

Automobiles may have put the Columbus Buggy Company out of business, but we’re glad to keep a little part of its legacy rolling along.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 19th century, Ohio, horse drawn transport, Firestone family, entrepreneurship, by Matt Anderson

The Office of George Nelson & Co.

In 1947, George Nelson opened his eponymous design office on Lexington Avenue in New York City. George Nelson & Co., as the first iteration of the office was named, was located on the second floor of a narrow building; the ground floor was a health food restaurant. In the introduction to Nelson’s collection of 26 essays called Problems of Design, Museum of Modern Art curator Arthur Drexler recalled that the restaurant had a loyal customer base, even though it “smelled funny.” Drexler observed an “unnerving contrast between the solemnity on the ground floor and that haphazard urbanity on the floor above.” George Nelson’s tendency to do many things simultaneously would have created a sometimes chaotic but always exhilarating environment that perhaps occasionally featured a pungent reminder of its downstairs neighbor.

Over the next four decades, the office would change names, move around New York City, employ many of the best and brightest designers, and complete a dizzying number of projects for a variety of clients. Constant through these changes was George Nelson’s emphasis on the importance of the design process. Even late nights at the office, sometimes saturated with drink, could be productive. Concepts imagined the night before might find their way to the drawing board in the bright light of the morning to be refined, altered, and honed further.

Sometimes, Nelson was more involved with the ideation and later refinement of an idea than with its realization—the office’s staff designers tended to that. A one-time employee of the office, architect and designer Michael Graves, reminisced that Nelson “would come in and touch down his magic dust on somebody and then leave.” While Nelson’s “magic dust”—and the powerful brand that his name symbolized—was vital to the office’s success, Nelson’s own hand in the development of a product or design was sometimes exaggerated. It has taken many years for certain designs to be accurately attributed—and surely there are many more that have not been and may never be. This problem is not unique to Nelson’s office, however, and was often the price designers paid to gain experience and contacts in the field. Hilda Longinotti, the office’s long-time receptionist, reflected on this: “As the years went by, George with all of his intelligence, did not do one thing he should have done and that is make the most talented designers partners in the firm. He gave them titles, but he didn’t give them a piece of the business. As the years went by, they left to form their own offices…”

The hundred-plus people employed by George Nelson over the course of his career—some for a short time and others much longer—include Lance Wyman, Ernest Farmer, Tomoko Miho, Irving Harper, Michael Graves, Don Ervin, Lucia DeRespinis, George Tscherny, and many others. The Henry Ford’s collections feature graphics and products designed by Nelson himself as well as some confirmed to be designed by the office’s staff. Below, we will focus on three of these designers: Irving Harper, George Tscherny, and Tomoko Miho.

Irving Harper

For many of the years that George Nelson was Herman Miller’s design director, Irving Harper was the director of design at George Nelson’s office. George Nelson hired Harper in 1947, and Harper did a little bit of everything in his tenure there—industrial design, furniture, and, eventually, graphics. Although he didn’t have much experience in graphic design, Harper quickly excelled. Herman Miller’s sweeping red “M” logo was one of Harper’s first forays into graphic design, and, 75 years later, the logo is still beloved and used by the company. Harper also designed many of the Nelson Office’s notable products, including many of the clocks for Howard Miller and the iconic Marshmallow sofa.

Born in New York City in 1916, Harper trained as an architect at New York’s Cooper Union and Brooklyn College. He soon began designing interiors. At the age of 19, Harper was hired by Gilbert Rohde, Nelson’s predecessor at Herman Miller, to work on projects for the 1939 World’s Fair, including renderings and production drawings. Harper worked for George Nelson from 1947 until 1963, when he left to start his own firm, Harper+George, which primarily designed interiors for commercial clients. Harper began to create incredibly intricate paper sculptures in the early 1960s as a stress relief measure, turning him into a proper sculptor as well as designer. The paper sculptures bridged his active design years into his retirement in 1983, when his sculpting output greatly increased. Harper died in 2015 at his long-time home in Rye, New York.

This 1947 advertisement features Herman Miller’s sweeping new “M” logo, which was designed by Irving Harper in one of his first forays into graphic design. / THF623975

Irving Harper designed this 1961 Herman Miller advertisement for the “Eames Chair Collection.” / THF266918

George Tscherny

George Tscherny began working at George Nelson & Co. in 1953. Nelson hired Tscherny specifically to design print advertisements for the office’s largest client, Herman Miller, under the direction of Irving Harper. Nelson reportedly had a hands-off approach. Tscherny recalled, “He had no pressing need to involve himself in my area. That meant I could do almost anything within reason.” Tscherny was able to expand and hone his graphic style, which stresses the inherent nature of objects and is always human-centered—even when a human isn’t visible.

Tscherny, born into a Jewish family in 1924 in Budapest, Hungary, grew up in Berlin, Germany. The rise of the Nazi Party and, specifically, the evening of Kristallnacht (“The Night of the Broken Glass”) on November 10, 1938, led Tscherny to believe “there was no future for us in Germany.” The following month, George and his younger brother Alexander escaped to the Netherlands, where they spent the following years moving between refugee camps and Jewish orphanages. Their parents, Mandel and Bella (Heimann) Tscherny, obtained visas and emigrated to the United States in 1939. It wasn’t until June of 1941 that George and Alexander finally joined their parents in New Jersey, after numerous close calls with the Nazi Party. In 1943, George Tscherny enlisted as a soldier in the U.S. Army to fight in World War II and went back to Europe, using his language skills as an interpreter. After the war, Tscherny used the G.I. Bill to fund his study of graphic design, attending the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York; he would leave just weeks before graduation to work for designer Donald Deskey. In 1953, he was hired by George Nelson.

Although Tscherny only worked for Nelson until 1955, numerous advertisements he designed for Herman Miller during his short tenure became iconic of the era. Tscherny left the office to start his independent design studio, which designed graphics for major corporations. He also taught at the School of the Visual Arts in New York City for over half a century. Tscherny says he attempted to teach his students, as Nelson taught him, “not to have preconceptions, but rather to be receptive to new ideas.” Tscherny, currently 96 years old, lives in New York City with Sonia, his wife of over 70 years.

The famous "Traveling Men" advertisement for Herman Miller was designed by George Tscherny in 1954. / THF624755

George Tscherny’s 1955 “Herman Miller Comes to Dallas” advertisement implies a human presence through the inclusion of a cowboy hat. / THF148287

Tomoko Miho

Tomoko Miho was one of a few women that George Nelson hired to design for his office. Miho is not very well-known today, both due to a societal tendency to ignore contributions of women working in the mid-century period and to her private and reserved nature. Although her name may be unfamiliar, this is not due to a lack of talent—Miho’s skill in graphic design and art direction were extraordinary. Once you identify her clean, minimalist, architectural style, it becomes distinct from the others working in the Nelson office.

Born Tomoko Kawakami in 1931 in Los Angeles, she and her family were held at the Gila River Japanese internment camp in Arizona during World War II. Afterwards, the family moved to Minneapolis, where Tomoko began coursework in art and design. She received a full scholarship to the Art Center School in Los Angeles, where she graduated with a degree in Industrial Design in 1958. She worked as a packaging designer for Harley Earl Associates before moving to New York City and, on the recommendation of George Tscherny, she contacted Irving Harper and was then hired by George Nelson in 1960. As the prominent graphic designer (and later colleague of Miho) John Massey stated, Miho was “a master of the dramatic understatement.” Her work is graceful, clean, and highly structured, while also seeming unrestricted. Her designs are masterfully well-balanced and lend themselves well to their primary purpose—conveying information.

Miho worked for the Nelson office until 1965, when family commitments took her to California, back to New York City, and then to Chicago, where she worked for the Center for Advanced Research and Design (CARD). She designed possibly her best known work while working for CARD—the 1967 "Great Architecture in Chicago" poster. It reflects her sense that Chicago’s architecture is “both solid and ethereal,” as Miho explained. Miho continued to collaborate with designers she met at George Nelson & Co. for years. She also had an incredibly long-lasting relationship with Herman Miller: she began designing for the company during her tenure at George Nelson & Co., continued while she was employed by CARD, and even after starting her own firm, Tomoko Miho Co., Herman Miller remained a client. Miho passed away in 2012 in New York City.

Tomoko Miho featured the Herman Miller logo in this price list, camouflaging it in bold contrasting stripes. This is one document in a suite, all featuring the same design, but in different colorways. / THF64160

The “Library Group” trade literature was designed by Tomoko Miho, circa 1970. / THF147737

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Europe, New York, 20th century, women's history, immigrants, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White, advertising

1981 Checker Marathon Taxicab

THF90395

A familiar vehicle few Americans use.

Most Americans rarely take taxis—perhaps only when going to an airport or visiting a city with unfamiliar transit systems. But taxis are a viable alternative to owning a car in cities where traffic is dense, and parking is inconvenient and expensive. They provide point-to-point transportation, alone or in combination with subways, elevated trains, and buses—and in increasing competition with Internet-based ridesharing services.

The term “cab” predates the automobile. It comes from “cabriolet,” a type of carriage used for paid fares.

"Omnibuses & Cabs, Their Origin & History," 1902 / THF105848

“Taxi” comes from taximètre, a French word for a meter that measures distance and calculates a fare. By 1900, meters were widely used in Europe and came to the U.S. in 1907.

The Automobile Magazine for March 19, 1908 / THF105850

In 1961, Checker had been creating purpose-built cabs for 39 years.

"Use the Only Real Taxicab, Checker," 1961 / THF105852

Checker cabs were spacious and easy to get into and out of, with big trunks for lots of luggage.

"Checker, The Only Real Taxicab!," 1967 / THF105854

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1956 Chevrolet Bel Air Convertible

- 1931 Duesenberg Model J Convertible Victoria: The World’s Finest Motorcar?

- Women in the War Effort Workforce During WWII

- 1959 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz Convertible: Is This the Car for You?

20th century, 1980s, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, cars

Which Muppet Are You?: A Personality Quiz

Several stars of The Muppet Show pose for a group shot on one side of "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187292

By the time The Muppet Show premiered in 1976, numerous Muppet characters had already been introduced to the public through a host of TV shows and commercials. However, this new weekly TV series that lasted for five seasons offered the opportunity for Jim Henson and his collaborators to further develop certain characters while introducing several new ones. The relatable personality traits of the main characters in The Muppet Show became part of their unique charm and lasting appeal.

What character from The Muppet Show are you most like? To find out, look at the following character traits of eight main characters from The Muppet Show, choose the group of traits that best fits you (or most intrigues you), then see which character matches those.

- You have your own hopes and dreams, but you often find yourself helping others in need. Because of this, others gravitate to you. You, in turn, treat them with patience and kindness. Well, at least you try.

- In school, you were the class clown, always trying to make people laugh. Even though they often didn’t get your unique sense of humor, that never deterred you from trying again. And again. Underneath that wise-cracking exterior, you are a friendly, loving, sensitive soul.

- You may be willing to go along with the crowd for a while, but underneath, you crave attention. You are bold, strong-willed, and, when pushed around, you have a tendency to be stubborn and single-minded. You know what you want and possess the steely determination for go after it.

- You are a risk-taking adventurer. You prefer excitement and thrills to patience and planning. This may not always turn out the way you had hoped, but you don’t give up. You are on a continual search for the meaning in life and have a strong desire to find a place where you belong.

- With a steady hand and a level head, you make sure that everything is functioning behind the scenes. You enjoy solving problems and assisting others. Staying in the background lets you get involved, in a low-pressure way, with everyone and everything. Which is not to say that you don’t enjoy the limelight every once in a while.

- You are extremely enthusiastic in everything you do. While some might say that you get carried away too easily, or are too obsessive about certain interests, you just think of yourself as passionate and devoted. Because why go just halfway when you really love something?

- Unlike friends and colleagues whose talents are hidden or still evolving, you already have real talent! This gives you the confidence to be calm, steady, easygoing, and charming. You are friendly with most everyone and willing to lend a hand when needed.

- You are studious, serious, and thoughtful. You feel that it’s important to live by the rules and you have little patience with those who don’t. Some might say you are judgmental, but you just feel that you have high standards—without those, everything would just descend into chaos. Unfortunately, it usually does.

Pick your set of traits, then scroll down to discover which Muppet you are most like!

Kermit the Frog

Closeup shot of Kermit, depicted on "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187305

If you chose #1, you are like Kermit the Frog. Introduced in 1955 on Jim Henson’s first TV show, Sam and Friends, Kermit evolved from a sort of abstract lizard-like creature to a definite frog with flippers, a fringed collar, and a distinct personality. Kermit was not initially intended to host The Muppet Show, but his warm personality and ability to get along with others won him the starring role. Only occasionally did he panic, get annoyed, or become frustrated by the chaos around him before he would once again resume the calm, easygoing demeanor that drew others to him in the first place.

Fozzie Bear

Closeup shot of Fozzie Bear, featured on one side of "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187309

If you chose #2, you are like Fozzie Bear. Fozzie is known as The Muppet Show’s resident stand-up comedian and Kermit’s best friend. In fact, the full range of his personality took a while to emerge. At first, his inability to deliver a punchline made him seem inept, embarrassing, even depressing. Eventually, as Fozzie developed a wider range of emotions, audiences began to connect with his newfound sense of optimism, enthusiasm, and just plain fun-loving nature.

Miss Piggy

Closeup shot of Miss Piggy, depicted on "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187310

If you chose #3, you relate to Miss Piggy, The Muppet Show’s resident diva, best known for her unrequited love for Kermit the Frog. Miss Piggy was also The Muppet Show’s most unexpected breakout character. Just like a true Hollywood movie star, she got her start as a little-known background singer and chorus girl named Miss Piggy Lee (a homage to singer Peggy Lee). But during the first episode of The Muppet Show, her true character began to emerge—that trademark determination hidden behind a coy exterior. Her newfound stardom pushed hapless Fozzie Bear to the background as a supporting character.

Gonzo the Great

Closeup shot of Gonzo, depicted on "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187306

If you chose #4, you are like Gonzo the Great. Gonzo traces his origin to the purple hook-nosed creature, Snarl, who appeared in Jim Henson’s 1970 TV special, The Great Santa Claus Switch. Newly recycled and slightly remodeled, Gonzo appeared on The Muppet Show as its resident stuntman. Well, Gonzo would not consider himself merely a stuntman. He would describe his stunts as avant-garde acts of performance art.

Scooter

Closeup shot of Scooter, depicted on "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187307

If you chose #5, you are like Scooter, The Muppet Show’s gofer and jack-of-all-trades. Scooter appeared most frequently in scenes that took place behind the scenes at the Muppet Theatre. He ostensibly got the job as the show’s backstage assistant because his uncle owned the theatre, but over the years—despite his moderate pestering of Kermit—he proved his worth and stayed on. He also occasionally appeared on stage, even hosting the show once. He was one of the few true aficionados of Fozzie Bear’s jokes, and the two occasionally performed acts together.

Animal

Closeup shot of Animal, depicted on "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187311

If you chose #6, you have the tendencies of Animal, the exuberant drummer of The Muppet Show’s house band, Dr. Teeth and the Electric Mayhem. Despite popular legend, he was not based upon any real-life drummer. However, he does consider Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa, Keith Moon of The Who, and Ginger Baker of Cream and Blind Faith to be among his musical influences. His most memorable moment on The Muppet Show was when he performed a drumming contest with legendary jazz musician Buddy Rich. Animal’s unrestrained style made him popular not only with young people but also among many of the guest stars on the show.

Rowlf

Closeup shot of Rowlf, depicted on "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187308

If you chose #7, you are like Rowlf, the resident piano-playing dog of indeterminate breed who performed on several episodes of The Muppet Show. Rowlf’s origins date back almost as far as Kermit’s—he first appeared on commercials for Purina Dog Chow in 1962. He gained fame soon after, making regular appearances on The Jimmy Dean Show—a variety show hosted by the country singer of that name, who became famous for his hit, “Big Bad John.” Rowlf’s confidence lent an air of stability to The Muppet Show, as he brought his years of experience to the cast of new, unformed, and unproven characters.

Sam Eagle

Closeup shot of Sam Eagle, depicted on "Jim Henson's Muppets" Lunchbox, 1979 / THF187297

If you chose #8, you are like Sam Eagle—short for Sam the American Eagle. With that name, it goes without saying that Sam is ultra-patriotic, especially about all things American. He also fashions himself as The Muppet Show’s moral compass, always on the lookout for acts of dignified, high-brow culture. The fact that he knows nothing about culture and never finds these types of acts on The Muppet Show does not seem to deter him.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Muppets, TV, quizzes, popular culture, Jim Henson, by Donna R. Braden

Driven to Win: Showmanship

Barney Oldfield and Lincoln Beachey Racing, Columbus, Ohio, 1914 / THF228829

Skilled Showmen

In racing, a skilled driver means everything, but if that person is blessed with charisma and an ability to attract attention, then the fruits of promotion are close at hand. Ability behind the wheel is essential for winning races. But from the sport’s earliest days, success in auto racing also has been augmented by a driver’s ability to attract attention and build a relationship with fans. This helps generate public awareness, fundraising, and sponsorship. In our new racing exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, two exceptional examples—one from the early days of the sport and one from today—are featured, along with their cars.

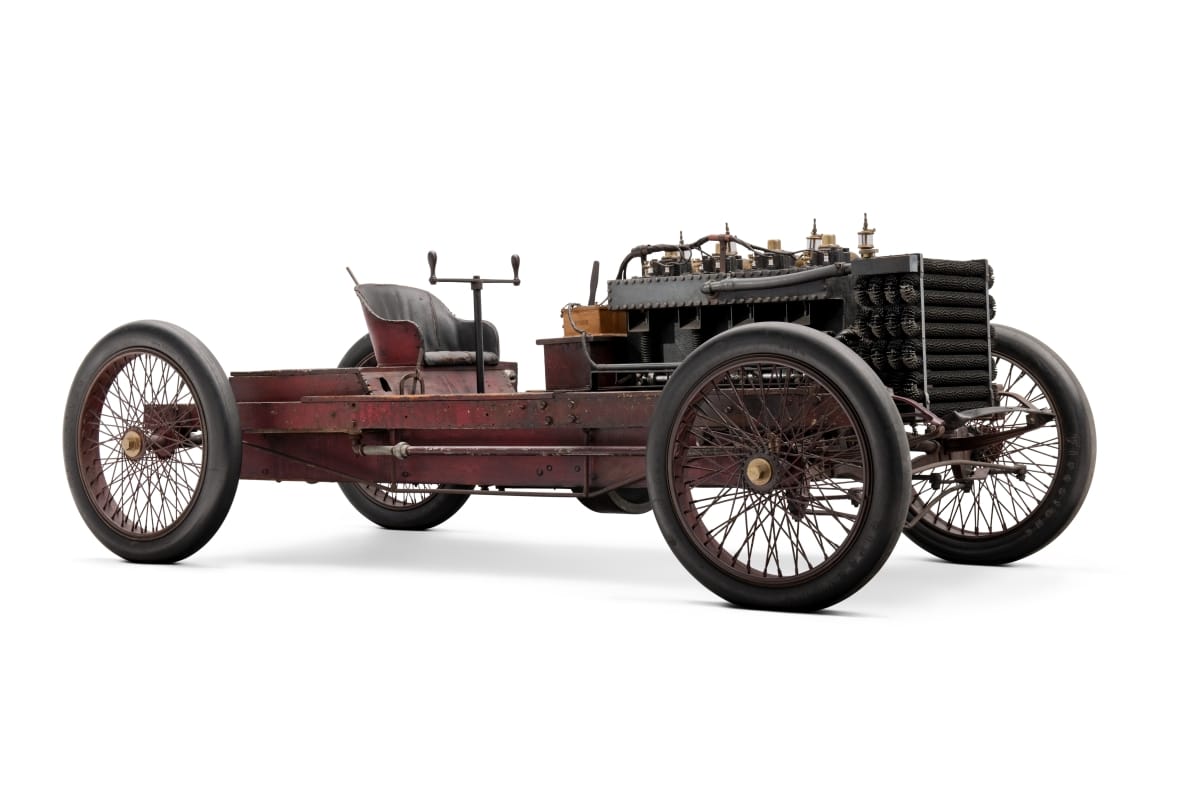

Ford “999,” Driven by Barney Oldfield

THF90218

In the early 1900s, Barney Oldfield made himself larger than life with his widely publicized exploits on racetracks. Oldfield had a reputation as a fearless bicycle racer, and the very first automobile he ever drove was Henry Ford’s “999.” That was about a week before he raced it in the Manufacturers' Challenge Cup on October 25, 1902. Oldfield won handily, which launched his colorful auto racing career. It also produced the first of many opportunities for Henry Ford to promote Oldfield’s exploits to continue building his own reputation on the way to founding Ford Motor Company a year later.

2012 Ford Fiesta ST HFHV, Driven by Ken Block

THF179703

Ken Block has successfully used his charisma, along with his unquestionable car-control skills, to create a name for himself and to build public awareness for his sponsors and their products. Barney Oldfield was largely limited to personal appearances, posters, and newspaper stories and ads to build his brand and those of his backers, but Ken Block has been able to add video, television, the Internet, and social media to his arsenal for attracting attention. His viral “Gymkhana” videos alone have generated hundreds of millions of views around the world. The car you’ll see in Driven to Win was used in “Gymkhana FIVE: Ultimate Urban Playground; San Francisco.”

Additional Artifacts

THF179739

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts related to showmanship in Driven to Win.

- Racing Helmet Worn by Ken Block in "Gymkhana Five," circa 2012

- Sunglasses, Worn by Ken Block, circa 2012

- Driving Shoes Worn by Ken Block in "Gymkhana Five," circa 2012

Dig Deeper

Katherine Stinson with Barney Oldfield at Ascot Speedway, Los Angeles, California, November 29, 1917 / THF129701

Learn more about showmanship in racing with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Learn even more about Barney Oldfield’s life and legacy through artifacts from our collections.

- Take a moment to get to know the “999.”

- Read our press release to learn more about Ken Block’s Ford Fiesta featured in the exhibit.

- Watch our interview with another great racing showman, Mario Andretti.

- Uncover the answers to eight questions with Vaughn Gittin, Jr. in The Henry Ford Magazine.

- See legend Richard Petty and a number of his NASCAR driver colleagues visit Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.

- Discover the story of Dale Earnhardt, Sr.’s breakthrough victory at the 1998 Daytona 500.

popular culture, Henry Ford, race cars, race car drivers, racing, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win

Market Day: Detroit Central Market’s Vegetable Shed Comes to Greenfield Village

Central Market in Downtown Detroit, Michigan, circa 1890 / THF96803

The historic Detroit Central Market vegetable shed will re-create a local food environment within Greenfield Village

Few mid-19th-century public market structures survive. Detroit’s vegetable shed or building, which opened in 1861, is one of the oldest of those survivors in the nation.

This ornamental bracket from the Detroit Central Market vegetable shed will be one of the architectural elements visitors will see when the building is reconstructed in Greenfield Village. / THF173219

The shed’s story is certainly harrowing. It escaped fire in 1876 and dismantling in 1894. A relocation to nearby Belle Isle saved it. There, it served many purposes until 2003, when The Henry Ford acquired it. And now, generous donors have made its reconstruction in Greenfield Village possible. (Follow @thehenryford on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, and/or via our e-mails for more on when the shed will officially open in the village.)

Detroit Central Market’s Vegetable Shed, repurposed as a “horse shed,” circa 1900, on Detroit’s Belle Isle. / THF139104

As a reconstructed event space, the shed will serve as an open-air market of ideas, a place where food and common cause will bring people together to discuss meaty subjects, such as land use and regenerative agriculture, social entrepreneurship, urban and alternative agriculture, and food security. It will shelter a vibrant historic market vignette where florists, fishmongers, hucksters (hucksters being another term for market gardeners, people who raised vegetables to sell at market to retail customers), and peddlers all vied for sales. The scripted exchanges will inform us about ways that vendors historically managed ethnic tensions and provided a social safety net to the homeless, impoverished, and downtrodden. This content will be carefully curated and managed by The Henry Ford’s dedicated staff, who will ensure programming on the stuff of life in perpetuity.

Heart of a City

The Henry Ford’s vision for the restored Detroit Central Market vegetable shed as a communal center in Greenfield Village is akin to what Detroit city officials envisioned when they adopted a nearly 1,000-year-old tradition to establish a public market in 1802.

View of Detroit Central Market (here called “Cadillac Square Market”) from the roof of City Hall, circa 1875 / THF146289

The market grew near the city hall and was maintained by the city for decades, calling attention to the symbiotic relationship between urban governments, the market gardeners and farmers in and near the city, and the health and well-being of city dwellers. The market, in fact, was called City Hall Market until the city hall moved across the centrally located downtown gathering space known as Campus Martius. Thereafter, the name Detroit Central Market came to be—denoting the market’s location, but also its centrality to the civic, cultural, and ceremonial heart of the city. Within an easy walk lay city hall, the Michigan Solders’ and Sailors’ Monument, churches, schools, playhouses, and the opera, among other attractions. Within this vibrant environment, vendors went about their daily business helping customers feed themselves, a routine that fed a city.

Theoretically, a thriving city market eased Detroiters’ worries about the source of their next meal. It freed them to build a livelihood around something other than agriculture, while farmers and market gardeners knew they had a steady market for their produce and fresh meat. Today, we would call Detroit’s Central Market a “local food environment,” the place where customers bought foodstuffs directly from butchers, hucksters, florists, fishmongers, and confectioners.

A community grew within and around the market that facilitated entrepreneurship. Vendors, usually sole proprietors and startups, had a fixed number of resources—the vegetables, fruit and flowers they raised, fish they caught, fresh meat they butchered, knickknacks or “Yankee trinkets” they sold, or services such as chimney sweeping that they hawked to customers.

They had to be ingenious to draw attention to their resources and thus increase the likelihood of a sale. This made for vibrant market days.

People & Prejudices

Practicality dictated that the market be in the center of downtown Detroit and in the shadow of city hall. These were heavily trafficked areas, and structures were built as enclosed spaces to protect vendors and customers from the weather. The Detroit Common Council authorized, funded, maintained, and updated structures and built new ones as needed. It authorized a “clerk of the market” to collect rents, monitor compliance, mediate conflicts, and report to elected officials.

All did not go smoothly at Detroit’s Central Market, however. The fish market in the Catholic city of Detroit was, by many accounts, the poorest fish market in the country. Why? As one fish dealer explained, people in Detroit fished. Therefore, they did not have to buy. Yet care went into designating northern stalls in the vegetable building as the purview of fishmongers, available for auction and then for rent by the month, for ten months of the year.

People gather at the vegetable building at Detroit's Central Market, circa 1885 / THF136886

Records indicate that there was no love lost between fishmongers and butchers, likely because butchers held power that fishmongers did not. Butchers were organized. Some even served as elected officials. They held membership in community associations and had strong ties to ethnic and immigrant communities.

The vegetable shed at Detroit Central Market most obviously housed hucksters, many of them women. Of the 32 greengrocers and market hucksters who listed their business address as City Hall Market (CH Market) in the 1864–1865 Detroit City Directory, nearly one-third (ten) were women. In 1874, the percentage of women hucksters increased to nearly 40%. Racial diversity also existed. Several Black hucksters had market addresses over the years, and at least one had a relatively stable business selling garden vegetables at the market from the early 1860s to the mid-1870s. Overall, however, newspaper accounts stereotyped hucksters as country bumpkins unable to handle their market wagons. This indicated a lack of respect on the part of city dwellers who depended on these growers for their food.

Cultural conflict erupted at the market as individuals from numerous ethnic groups, some well-established and others newcomers, had to cohabitate and compete at the public market. Louis Schiappecasse, an Italian immigrant identified as the first outdoor fruit merchant in Detroit, provides a good case in point. He established himself on Jefferson Avenue across from the Biddle House in 1870. When he died in 1916, the headline read: “Millionaire Fruit Merchant Is Dead.” Yet, in the fever pitch of anti-immigrant sentiment in 1890, a newspaper reporter, without naming names, quoted shop owners near Central Market who were frustrated with Italian fruit salesmen too cheap to pay rent for a market stall. Instead, they claimed that fruit salesmen set up pop-up stands that obstructed sidewalks and made it difficult for patrons to enter some stores.

A customer at the Detroit Central Market vegetable building, 1885–1893 / THF623871

Finally, one of the most notable entrepreneurs at Central Market, who appears regularly in minutes of Detroit Common Council meetings, gained attention for her refusal to accept the city’s decision to close the market. Mary Judge was a widow, listed her address as an alleyway at least once, and changed her market specialty almost every year—sometimes selling vegetables, sometimes flowers, sometimes candy, sometimes refreshments. She also received special dispensation from Detroit’s Committee on Markets when she was cited for violating three market standards. She was allowed to sell vegetables out of stall No. 44 because she was “very poor and unfit for any other occupation.” This last affirmed the function of the public market as a social safety net.

Vendors practiced benevolence, too, operating as social entrepreneurs, at least in relation to residents in the Home for the Friendless. The Ladies’ Christian Union organized the Home for the Friendless in May 1860 to aid homeless women, children (including the children of incarcerated individuals), and elderly women. Twice each week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays during the market season, boys from the home carried a basket to the market. Butchers and hucksters filled the basket with produce and meats, which helped make ends meet at the home.

National Platform

Some views of the Detroit Central Market vegetable shed on Belle Isle as The Henry Ford dismantled it in 2003, so it could be reconstructed later in Greenfield Village. You can browse over 100 additional photos of this complex process in our Digital Collections. / THF113491, THF113506, THF113516, THF113517, THF113545, THF113573

The Detroit Central Market vendors helped feed hundreds of thousands of mouths in downtown Detroit. When reconstructed in Greenfield Village, the vegetable shed where they once sold their wares will support programming that will enrich millions of minds on topics as wide ranging as agricultural ethics and food justice.

Countless stories await exploration: Stories based on the lives of vendors and their customers; city council members and market staff; and the business owners, entertainers, and entrepreneurs at work around the marketplace can all teach us lessons that we can adapt to help shape a better future.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from an article originally published in the January-May 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Additional Readings:

- Farmers Market

- Bring the Detroit Central Farmers Market to Greenfield Village

- Detroit Central Market Coming to Life

- The Market, Envisioned

Detroit Central Market, The Henry Ford Magazine, by Debra A. Reid, Michigan, Detroit, entrepreneurship, shopping, food, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village