#InnovationNation: Power & Energy

Thomas Edison, engines, alternative fuel vehicles, Ford Motor Company, cars, railroads, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, power, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

How Does Your Vegetable Garden Grow?

Do you raise vegetables to feed yourself? If the answer is “Yes,” you are not alone. The National Gardening Survey reported that 77 percent of American households gardened in 2018, and the number of young gardeners (ages 18 to 34) increased exponentially from previous years. Why? Concern about food sources, an interest in healthy eating, and a DIY approach to problem solving motivate most to take up the trowel.

The process of raising vegetables to feed yourself carries with it a sense of urgency that many of us with kitchen cabinets full of canned goods cannot fathom. Farm families planted, cultivated, harvested, processed and consumed their own garden produce into the 20th century. This was hard but required work to satisfy their needs.

Two members of the Lancaster Unit of the Woman’s National Farm and Garden Association digging potatoes, 1918. THF 288960

Seed Sources

Gardeners need seeds. Before the mid-19th century, home gardeners saved their own seeds for the next year’s crop. If a disaster destroyed the next year’s seeds, home gardeners had to purchase seeds.

Commercial seed sales began as early as 1790 in the community of Shakers at Watervliet, New York. The Mt. Lebanon, New York, Shaker community established the Shaker Seed Company in 1794. The Watervliet Shakers first sold pre-packaged seeds in 1835, but the Mt. Lebanon community dominated the garden seed business until 1891. They marketed prepackaged seeds in boxes like this directly to store owners who sold to customers.

Shakers Genuine Garden Seeds Box, 1861-1895. THF 173513

Satisfying the demand for garden seeds became big business. Entrepreneurs established seed farms and warehouses in cities where laborers cultivated, cleaned, stored and packaged seeds. The D.M. Ferry & Co. provides a good example.

D.M. Ferry & Company Headquarters and Warehouse, Detroit, Michigan, circa 1880. THF76854

Entrepreneurs invested earnings into this lucrative industry.

Hiram Sibley, who made a fortune in telegraphy, and spent 16 years as president of the Western Union Telegraph Company, claimed to have the largest seed farm in the world, and an international production and distribution system based in Rochester, New York, and Chicago, Illinois. Though the company name changed, the techniques of prepackaging seeds developed by the Shakers at Watervliet and direct marketing of filled boxes to store owners remained an industry standard.

Hiram Sibley & Co. Seed Box, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181542

Planting gardens requires prepackaged seeds (unless you save your own!). These little packets tell big stories about ingenuity and resourcefulness. We acquired this 1880s Sibley & Co. seed box from the Barnes Store in Rock Stream, NY in 1929.

The original Sibley seed papers and packets are on view in a replica Hiram Sibley & Co seed box in the J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village, which our members and guests will be able to enjoy once again when we reopen. Until then, take a virtual trip to the store by way of Mo Rocca and Innovation Nation.

Looking for gardening inspiration? Historic seed and flower packets can provide plenty! Survey the hundreds of seed packets dated 1880s to the present in our digital collections and create your own virtual garden.

The variety might astound you, from the mangelwurzel (raised for livestock feed) to the Early Acme Tomato and the Giant Rocca Onion.

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Beet Long Red Mangelwurtzel” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181520

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Tomato Early Acme” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF278980

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Onion Giant Rocca” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF279020

Families in cities often did not have land to cultivate, so they relied on the public markets and green grocers as the source of their vegetables.

Canned goods changed the relationships between gardeners and their responsibility for meeting their own food needs. Affordable and available canned goods made it easy for most to hang up their garden trowels. As a result, raising vegetables became a lifestyle choice rather than a necessity for most Americans by the 1930s.

Can Label, “Butterfly Brand Stringless Beans,” circa 1880. THF293949

Times of crisis increase both personal interest and public investment in home-grown vegetables, as the national Victory Garden movements of the 20th century confirm.

Victory Gardens

Man Inspecting Tomato Plant in Victory Garden, June 1944. THF273191

Victory Gardens, a patriotic act during World War I and World War II, provide important examples of food resourcefulness and ingenuity.

You can find your own inspiration from Victory Garden items in our collections – from 1918 posters to Ford Motor Company gardens during the 1930s, and home-front mobilization during World War II here.

Woman's National Farm and Garden Association at Dedham Square Truck Market, 1918. THF288964

But the “fruits” of the garden didn’t just stay at home. Entrepreneurial-minded Americans took their goods to market, like these members of the Woman's National Farm & Garden Association and their "pop-up" curbside market in Dedham, Massachusetts, in 1918.

Clara Ford with a Model of the Roadside Market She Designed, circa 1930. THF117982

Clara Ford, at one time a president of the Women’s National Farm and Garden Association, also believed in the importance of eating local. Read more about her involvement with roadside markets here.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

food, agriculture, gardening, #THFCuratorChat, by Debra A. Reid

New Acquisition: LINC Computer Console

A LINC console built by Jerry Cox at the Central Institute for the Deaf, 1964.

There are many opinions about which device should be awarded the title of "the first personal computer." Contenders range from the well-known to the relatively obscure: the Kenbak-1 (1971), Micral N (1973), Xerox Alto (1973), Altair 8800 (1974), Apple 1 (1976), and a few other rarities that failed to reach market saturation. The "Laboratory INstrument Computer" (aka the LINC) is also counted among this group of "firsts." Two original examples of the main console for the LINC are now part of The Henry Ford's collection of computing history.

The LINC is an early transistorized computer designed for use in medical and scientific laboratories, created in the early-1960s at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory by Wesley A. Clark with Charles Molnar. It was one of the first machines that made it possible for individual researchers to sit in front of a computer in their own lab with a keyboard and screen in front of them. Researchers could directly program and receive instant visual feedback without the need to deal with punch cards or massive timeshare systems.

These features of the LINC certainly make a case for its illustrious position in the annals of personal computing history. For a computer to be considered "personal," the device must have had a keyboard, monitor, data storage, and ports for peripherals. The computer had to be a stand-alone device, and above all, it had to be intended for use by individuals, rather than the large "timeshare" systems often found in universities and large corporations.

The inside of a LINC console, showing a network of hand-wired and assembled components.

Prototyping

In 1961, Clark disappeared from the Lincoln Lab for three weeks and returned with a LINC prototype to show his managers. His ideal vision for the machine was centered on user friendliness. Clark wanted his machine to cost less than $25,000, which was the threshold a typical lab director could spend without needing higher approval. Unfortunately, Clark’s budget goal wasn’t reached—when commercially released in 1964, each full unit cost $43,000 dollars.

The first twelve LINCs were assembled in the summer of 1963 and placed in biomedical research labs across the country as part of a National Institute of Health-sponsored evaluation program. The future owners of the machines—known as the LINC Evaluation Program—travelled to MIT to take part in a one-month intensive training workshop where they would learn to build and maintain the computer themselves.

Once home, the flagship group of scientists, biologists, and medical researchers used this new technology to do things like interpret real-time data from EEG tests, measure nervous system signals and blood flow in the brain, and to collect date from acoustic tests. Experiments with early medical chatbots and medical analysis also happened on the LINC.

In 1964, a computer scientist named Jerry Cox arranged for the core LINC team to move from MIT to his newly formed Biomedical Computing Laboratory at Washington University at St. Louis. The two devices in The Henry Ford's recent acquisition were built in 1963 by Cox himself while he was working at the Central Institute for the Deaf. Cox was part of the original LINC Evaluation Board and received the "spare parts" leftover from the summer workshop directly from Wesley Clark.

Mary Allen Wilkes and her LINC "home computer." In addition to the main console, the LINC’s modular options included dual tape drives, an expanded register display, and an oscilloscope interface. Image courtesy of Rex B. Wilkes.

Mary Allen Wilkes

Mary Allen Wilkes made important contributions to the operating system for the LINC. After graduating from Wellesley College in 1960, Wilkes showed up at MIT to inquire about jobs and walked away with a position as a computer programmer. She translated her interest in “symbolic logic” philosophy into computer-based logic. Wilkes was assigned to the LINC project during its prototype phase and created the computer's Assembly Program. This allowed people to do things like create computer-aided medical analyses and design medical chatbots. In 1964, when the LINC project moved from MIT to the Washington University in St. Louis, rather than relocate, Wilkes chose to finish her programming on a LINC that she took home to her parent’s living room in Baltimore. Technically, you could say Wilkes was one of the first people in the world to have a personal computer in her own home.

Wesley Clark (left) and Bob Arnzen (right) with the "TOWTMTEWP" computer, circa 1972.

Wesley Clark

Wesley Clark's contributions to the history of computing began much earlier, in 1952, when he launched his career at the MIT Lincoln Laboratory. There, he worked as part of the Project Whirlwind team—the first real time digital computer, created as a flight simulator for the US Navy. At the Lincoln Lab, he also helped create the first fully transistorized computer, the TX-0, and was chief architect for the TX-2.

Throughout his career, Clark demonstrated an interest in helping to advance the interface capabilities between human and machine, while also dabbling in early artificial intelligence. In 2017, The Henry Ford acquired another one of Clark's inventions called "The Only Working Turing Machine There Ever Was Probably" (aka the "TOWTMTEWP")—a delightfully quirky machine that was meant to demonstrate basic computing theory for Clark's students.

Whether it was the “actual first” or not, it is undeniable that the LINC represents a philosophical shift as one of the world’s first “user friendly” interactive minicomputers with consolidated interfaces that took up a small footprint. Addressing the “first” argument, Clark once said: "What excited us was not just the idea of a personal computer. It was the promise of a new departure from what everyone else seemed to think computers were all about."

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

Missouri, women's history, technology, Massachusetts, computers, by Kristen Gallerneaux, 20th century, 1960s, #THFCuratorChat

The Jazz Bowl: Emblem of a City, Icon of an Age

The Jazz Bowl, originally called The New Yorker, about 1930. THF88363

Cowan Pottery of Rocky River, Ohio, was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy in early 1930 when a commission arrived from a New York gallery for a New York City-themed punch bowl. The client -- who preferred to remain unknown -- wanted the design to capture the essence of the vibrant city.

The assignment went to 24-year-old ceramic artist Viktor Schreckengost. His design would become an icon of America’s “Jazz Age” of the 1920s and 1930s.

The Artist and His Design

The cosmopolitan Viktor Schreckengost was a perfect choice for this special commission. Schreckengost (1906-2008), born in Sebring, Ohio, had studied ceramics at the Cleveland Institute of Art in the late 1920s. He then spent a year in Vienna, where he was introduced to cutting-edge ideas in European art and design. When Schreckengost returned to Ohio, he took a part-time teaching position at his alma mater and spent the balance of his time as a designer at Cowan Pottery.

A jazz musician as well as an artist, Schreckengost had firsthand knowledge of New York, where he frequented jazz clubs during visits. To Schreckengost, jazz music represented the spirit of New York. He wanted to capture its excitement and energy in visual form on his bowl. Schreckengost later recalled: “I thought back to a magical night when a friend and I went to see [Cab] Calloway at the Cotton Club [in Harlem] ... the city, the jazz, the Cotton Club, everything ... I knew I had to get it all on the bowl.”

During its heyday in the 1920s and 30s, the Cotton Club was the place to listen to jazz in New York. THF125266

A “Jazz”-inscribed drumhead surrounded by musical instruments symbolize the Cotton Club. Organ pipes represent the grand theater organs that graced New York City’s movie palaces during the 1920s and 1930s. Schreckengost recalled that he was especially fond of Radio City Music Hall’s Wurlitzer organ. THF88363

A show in progress at Radio City Music Hall auditorium, 1936. THF125259

The images on the Jazz Bowl, then, may be read as a night on the town in New York City, starting out in bustling Times Square; then on to Radio City Music Hall to enjoy a show; next, a stroll uptown past a group of soaring skyscrapers to take in a sweeping view of the Hudson River; afterward, a stop at a cocktail party; and finally--topping off the evening with a visit to the famous Cotton Club.

Times Square, circa 1930. THF125262i

The blinking traffic signals, and "Follies" and "Dance" signs on the Jazz Bowl portray the vitality of Times Square at night. THF88358

Schreckengost decorated the punch bowl with a deep turquoise blue background he described as “Egyptian,” since it recalled the shade found on ancient Egyptian pottery. According to Schreckengost, the penetrating blue immerses the viewer in the glow of the night air--and the sensation of mystery and magic of a night on the town.

This is the view of the New York skyline and the Hudson River that Schreckengost saw on his trips to the city and later interpreted in the Jazz Bowl. THF125264g

Skyscrapers, a luxury ocean liner, cocktails on a tray, and liquor bottles represent a night on the town. THF88364

The Famous Client

In early 1931, the finished bowl was delivered to New York. The pleased patron who had commissioned it immediately ordered two additional punch bowls. To Schreckengost’s delight, the patron turned out to be Eleanor Roosevelt, then First Lady of New York State. Mrs. Roosevelt had commissioned the bowl to celebrate her husband Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1930 reelection as governor. She presumably placed one bowl in the Governor’s Residence in Albany, one in the Roosevelts’ home in Hyde Park, and one in their Manhattan apartment. When the Roosevelts moved into the White House in 1933, after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election as President, one of the bowls made its way there as well.

Eleanor Roosevelt commissioned the Jazz Bowl to celebrate her husband’s 1930 reelection as governor of New York. THF208655

Mass Producing the Jazz Bowl?

Immediately after the Jazz Bowl was delivered to Eleanor Roosevelt, the New York City gallery placed an order for fifty identical bowls. Unfortunately, Schreckengost’s process was laborious--it took Cowan Pottery’s artisans an entire day to produce the incised decoration on Mrs. Roosevelt’s version. Cowan Pottery sought to mass produce the punch bowl, simplifying the original design to create a second and third version the company originally marketed as “The New Yorker.”

The Henry Ford’s bowl is the third version, known informally as “The Poor Man’s Jazz Bowl.” It is slightly smaller than the original and the decoration is raised, rather than scratched into the surface. No one knows exactly, but perhaps fifty of the original version, only a few of the unsuccessful second version, and possibly twenty of the third version of the Jazz Bowl were made in total. The whereabouts of many of the Jazz Bowls are not known, though they appear periodically on the art market and are acquired by eager collectors. Even the present location of the bowls made for Eleanor Roosevelt seems to be a mystery.

Jazz Bowl as Icon

The “Poor Man’s Jazz Bowl” didn’t save the Cowan Pottery from the ravages of the Great Depression -- by the end of 1931, the company folded. Viktor Schreckengost moved on, continuing to teach at the Cleveland Institute of Art and pursuing freelance design for several firms. His Jazz Bowl would come to be recognized as a visual icon of the Jazz Age in America.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series.

New York, 20th century, 1930s, 1920s, presidents, music, manufacturing, making, Henry Ford Museum, furnishings, decorative arts, by Charles Sable, art

The Henry Ford’s Ingersoll Milling Machine and Mass Production at Highland Park

THF129649

What are the icons of the Industrial Revolution—steam engines, printing presses, combine harvesters, textile machinery? Any such list would surely include Ford’s Model T. Like the other machines that would make the grade it too was a complex mechanism, but it was also a beloved consumer product rooted in personal practical everyday use, and it was a design icon—in its day a symbol of absolute modernity.

The T’s success came about through two revolutions within the Industrial Revolution—those of power generation and distribution, and precision production manufacturing. Developments in the electrical industry liberated Henry Ford and his production experts from the constraints of mechanical power distribution. Earlier systems dictated where machinery was placed based on long straight runs of shafts and associated pulleys. Electric motors powering first groups and then individual machines enabled Ford’s engineers to position machine tools where the production process dictated. It was the incredible machines developed specifically for that process that were crucial to the speed and quality of Model T production.

Henry Ford and his assistants developed a system of mass production at Ford Motor Company’s Highland Park plant that was based on moving components through a refined sequence of manufacturing, machining and assembly steps. Launched in October 1913, Ford’s new system ultimately reduced the time of producing Model Ts from about 12½ man-hours to only 1½ man-hours.

Model Ts contained more than ten thousand parts. Ford’s moving assembly line required that each one of these parts be manufactured to exacting tolerances (the acceptable amount of variation) and be fully interchangeable with any other part of its kind. By organizing the automobile’s construction into a series of distinct small steps and using precision machinery, the assembly line generated enormous gains in productivity.

This is the only survivor of the vast range of custom-designed high-production machine tools used at Ford’s Highland Park plant. THF129616

Machines like this 1912 Ingersoll milling machine were crucial to the high production levels attained at Highland Park. Milling machines are machine tools that rotate cutters to plane or shape surfaces. Teams of Ford specialists collaborated with machine tool designers to develop and continually improve machinery for Highland Park, resulting in milling machines that were capable of undertaking highly accurate, multiple cutting operations on many components at the same time.

One of six similar machines in a careful arrangement of machine tools in Highland Park’s cylinder finishing shop, this planer-type milling machine – both a vertical and a horizontal miller – simultaneously milled the underside and main bearing holders of Model T engine blocks. Cutters on the horizontal spindle shaped the bearing holders, while large cutters on vertical spindles milled the bottom surface of the blocks flat. The machine could mill 15 engine blocks in one batch—loaded and unloaded by semi-skilled labor. The work was physically demanding, and while it did not demand the skills of a trained machinist, it did require dexterity and attention to detail in addition to stamina.

The Henry Ford’s Ingersoll milling machine is represented by one of the six horizontal cross shapes labeled #2 on the left of this diagram, which shows the arrangement of machine tools in the cylinder block machining shop at Highland Park. THF300582

The Ingersoll milling machine first arrived at Ford’s Highland Park plant in December 1912. It was just one of a vast range of new, specialized machines that enabled Ford to mass produce quality, affordable vehicles – and capture 50% of the American market! Today, it is exhibited in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation as the only survivor of the custom-designed high-production machine tools used at Highland Park. Twenty-one feet long and eight feet high, the machine is an imposing presence and a compelling reminder of Ford’s moving assembly line—as important a development as the Model T itself.

Additional Readings:

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882- “Female Operatives Are Preferred”: Two Stories of Women in Manufacturing

- The Changing Nature of Sewing

- Collecting Mobility: Insights from Hagerty

cars, Ford Motor Company, Made in America, Henry Ford Museum, Model Ts, manufacturing

Celebrating Earth Day

As we celebrate Earth Day, do you know which iconic symbol for the environmentalism movement came first? The bird wing design on an Earth Day poster or the “Give Earth a Chance” button? If you thought it was the button, you’re correct.

Give Earth a Chance Button, 1970. THF284833

Students at the University of Michigan formed ENACT (Environmental Action for Survival Committee, Inc.) in 1969. They prototyped the button and started selling it in late 1969, months before the official Earth Day on April 22, 1970. This button was reputedly worn during Earth Day 1970.

Advertising Poster, "Earth Day April 22, 1970.” THF81862

If you picked the wing, the artist that created the poster, Jacob Landau, used a stylized wing in earlier artwork. Landau, an award-winning illustrator and artist, taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He created this poster for the Environmental Action Coalition which coordinated New York Earth Day activities in 1970.

Did Earth Day launch the Age of Conservation?

“Newsweek” Magazine. THF139548_redacted

Newsweek itemized threats that ravaged the environment in its January 26, 1970 issue. All resulted from human actions. Emissions and sewage polluted the air and water. Garbage clogged landfills. Population growth threatened to overtake available food supplies. Solving these challenges required cooperation and unity on the part of individuals as well as local, state, and national governments. Editors believed that replenishing the environment to sustain future generations could be “the greatest test” humans faced. They featured the “Give Earth a Chance” button with the caption: "Symbol of The Age of Conservation?"

What to do to save the Earth?

The overall goal of replenishing the environment to sustain future generations required action on many fronts. More than 20 million people across the United States participated in the first Earth Day. The teach-ins informed, marches conveyed the intensity of public interest, and graphic arts spoke volumes about what needed to be done.

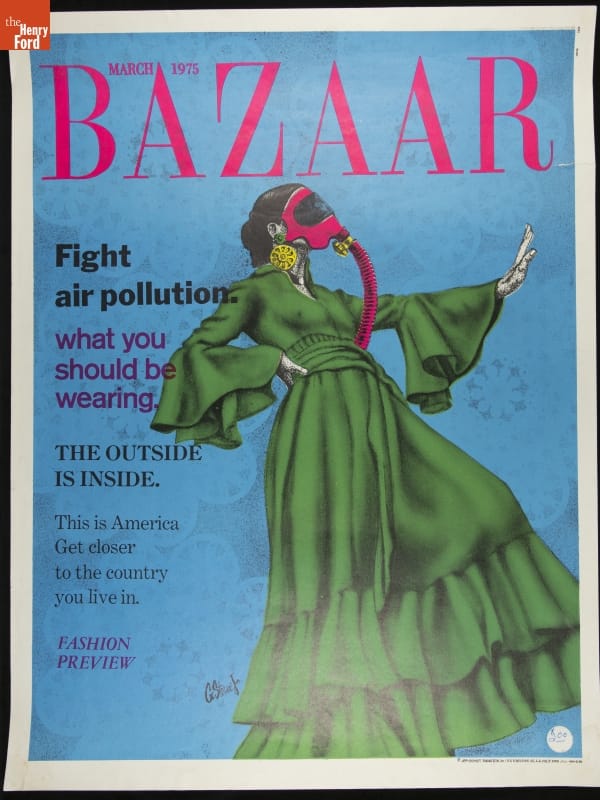

“March 1975, Bazaar, Fight Air Pollution, What You Should Be Wearing,” Poster, 1970. THF288328

This 1970 poster envisioned high fashion of the future, complete with a gas mask accessory. The moral of the story? Self-protection would not solve the problem of environmental pollution.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 empowered states and the national government to reduce emissions through regulation. This applied to industrial emissions as well as mobile sources (trains, planes, and automobiles, among others).

Interest in Recycling Grows

Poster by Eli Leon for Ecology Action, “Recycle” 1971. THF284835

Recycling emerged as a natural outgrowth of Earth Day, but local efforts could not succeed without explanation. First, consumers had to be convinced to save their newspapers, bottles, and cans, and then to make the extra effort to drop them off at centralized locations. This flyer showed how every-day consumer activity (grocery shopping) contributed to deforestation, littering, and garbage pile-up. Everybody could participate in the solution – recycling.

Recycling cost money, and this caused communities to balance what was good for the Earth, acceptable to residents, and possible within available operating funds. Even if customers voluntarily recycled, it still cost money to store recyclables and to sell the post-consumer materials to buyers.

Recycling Bin, Designed for Use in University City, Missouri, 1973. THF181540

City officials and residents in University City, Missouri, started curbside newspaper recycling in 1973, one of the first in the country to do so. Some argued that the city lost money because the investment in staff and trucks to haul materials cost more than the city earned from the sale, but saving the planet, not profit, motivated the effort. Eight years into the program, in 1981, city officials estimated that newspaper recycling kept 85,000 trees from the paper mill.

Easter Greeting Card, "Happy Easter," 1989-1990. THF114178

Today, more than 1/3 of post-consumer waste, by weight, is paper. Processing requires energy & chemicals, but recycled paper uses less water and produces less air pollution than making new paper from wood pulp. Maybe you buy greeting cards of 100% recycled paper, like this late 1980s example from our digital collections.

Environmentalism and Vegetable Gardening

Awareness of environmental issues affected the habits and actions of gardeners. Home gardening became an act of self-preservation in the context of Earth Day and environmentalism.

Lyman P. Wood founded Gardens for All in 1971, and the association conducted its first Gallup poll of a representative sample of American gardeners in 1973. It helped document the actions of gardeners, those proactive subscribers to new serials such as Mother Earth News. It confirmed their demographics and their economic investment.

Mother Earth News, 1970. THF290238

Raising vegetables using organic or natural fertilizers and traditional pest control methods became an act of resistance to increased use of synthetic chemical applications as concern about residual effects on human health increased.

How to Grow Vegetables and Fruits by the Organic Method, 1971. THF145272

Interest in organic methods remains high as concern about genetic-engineered foods polarizes consumers. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines biotechnology broadly. The definition includes plants that result from selective breeding and hybridization, as practiced by Luther Burbank, among others, as well as genetic modification accomplished by inserting foreign DNA/RNA into plant cells. This last became commercially viable only after 1987. These definitions affect seed marketing, as this “organic” Burbank Tomato (not genetically engineered) indicates.

Charles C. Hart Seed Company “Burbank Slicing Tomato” Seed Packet, circa 2018. THF276144

What Gardening Means Today

Gardening as an act of personal autonomy

"Assuming Financial Risk," Clip from Interview with Melvin Parson, April 5, 2019. THF295329

Social justice entrepreneurs believe gardens and gardening can change lives. Learn about the work of Melvin Parson, the Spring 2019 William Davidson Foundation Entrepreneur in Residence at The Henry Ford, in this expert set. You can also learn more from Will Allen in an interview in our Visionaries on Innovation series.

Environmentalism

The 1970 “The Age of Conservation” has changed with the times, but individual acts and world-wide efforts still sustain efforts to “Give the Earth a Chance.” You can learn more about environmentalism over the decades by viewing artifacts here.

To read more about Adam Rome and The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (2013), take a look at this site.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. This post came from a Twitter chat hosted in celebration of Earth Day 2020.

20th century, 1970s, nature, gardening, environmentalism, by Debra A. Reid, #THFCuratorChat

Diners: An American Original

In 1984, Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation acquired an old, dilapidated diner. When Lamy’s Diner—a Massachusetts diner from 1946—was brought into the museum, it raised more than a few eyebrows. Was a common diner, from such a recent era, worthy of restoration? Was it significant enough to be in a museum?

Happily, times have changed. Diners have gained newfound respect and appreciation. A closer look at diners reveals much about their role and significance in 20th-century America.

Diner, Wason Mfg. Co., interior, 1927-9. THF228034

Diners changed the way Americans thought about dining outside the home. A uniquely American invention, diners were convenient, social, and fun.

Horse-drawn lunch wagon, The Way-side Inn. THF38078

Diners originated with horse-drawn lunch wagons that came out on city streets at night, providing food to workers. They also attracted “night owls” like reporters, politicians, policemen, and supposedly even underworld characters!

Peddler’s cart: NYC street scene, 1890-1915. THF241185

Most people agree that horse-drawn lunch wagons evolved from peddler’s carts, like those shown here on this New York City street.

Cowboys at the Chuck Wagon, Crazy Woman Creek, Wyoming Territory, 1885. THF124569

Some people even think that cowboy chuck wagons helped inspire lunch wagons. Here’s a cool scene of a group of cowboys in Wyoming from 1885. Take a look at the fully outfitted chuck wagon in the picture above.

The Owl Night Lunch Wagon. THF88956

The Owl Night Lunch Wagon in Greenfield Village is thought to be the last surviving lunch wagon in America!

Visitors at the Owl Night Lunch Wagon. THF113945

Henry Ford ate here as a young engineer at Edison Illuminating Company in downtown Detroit. In 1927, Ford acquired the old lunch wagon to become the first food operation in Greenfield Village. Notice the menu and clothing worn by the guests.

In this segment of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, you can watch Mo Rocca and me eating hot dogs with horseradish at the Owl—just like Henry Ford might have done back in the day!

Walkor Lunch Car, c. 1918. THF297240

When cars increased congestion on city streets, horse-drawn lunch wagons were outlawed. To stay in business, operators had to re-locate their lunch wagons off the street. Sometimes these spaces were really cramped.

County Diner, 1926. THF297148

By the 1920s, manufacturers were producing complete units and shipping them to buyers’ specified locations. Here’s a nice exterior of one from that era.

Hi-Way Diner, Holyoke, Mass., ca. 1928. THF227976

These units were roomier and often cleaner than the by-now-shabby lunch wagons. To make them seem more upscale, people began calling these units “diners,” evoking the elegance of railroad dining cars.

Ad with streamlined diner, railroad, and airplane, 1941. THF296820

As more people got used to eating out in diners, more diners were produced. By the 1940s, some diners took on a streamlined form—inspired by the designs of the new, modern streamlined trains and airplanes.

Lamy’s Diner. THF77241

By the 1940s, there were so many diners around that this era became known as the “Golden Age of Diners.” This is where our own Lamy’s Diner comes in. It was made in 1946 by the Worcester Lunch Car Company of Massachusetts. You may not be able to get a cup of coffee and a piece of pie inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation right now, but you can visit Lamy’s virtually through this link.

Move of diner from Hudson, Mass., 1984. THF124974

The Henry Ford acquired Lamy’s Diner in 1984, then restored it for a new exhibition, “The Automobile in America Life” (1987). Here’s an image of it being lifted for its move to The Henry Ford.

Lamy’s Diner on original site. THF88966

Lamy’s Diner was originally located in Marlborough, Mass. Here’s a photograph of it on its original site. But, like other diners, it moved around a lot—to two other towns over the next four years.

Snapshot of Clovis Lamy in diner, ca. 1946. THF114397

Clovis Lamy was among other World War II veterans who dreamed of owning his own business when the war was over, and diners promised easy profits. As you can see here, he loved talking to people from behind the counter. From the beginning, Lamy’s Diner was a hopping place all hours of the day and night. You can read the whole story of Clovis Lamy and his diner in this blog post.

Lamy’s as a working restaurant in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

In 2012, Lamy’s became a working restaurant again—inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Nowadays, servers even wear diner uniforms that let you time-travel back to the 1940s. A few years ago, the menu was revamped. So now you can order frappes (Massachusetts-style milkshakes), New England clam chowder, and some of Clovis Lamy’s original recipes. Read more about the recent makeover here.

View of a McDonalds restaurant and sign, 1955. THF125822

Diners declined when fast food restaurants became popular. McDonald’s was first, with food prepared by an assembly-line process, paper packaging, and carry-out service. Check out this pre-Golden Arches McDonald’s.

Mountain View steel diner, Village Diner, Milford, PA, c. 1963. THF297276

The 1982 movie Diner helped spur a new revival in diners, as some people got tired of fast food and chain restaurants. Here’s an image of a Mountain View steel diner, much like the one used in that movie.

Dick Gutman in front of a Kullman diner, 1993. THF297029

One person was particularly instrumental in documenting and helping revive the interest in diners. That’s diner historian Richard Gutman. Here he is in 1993 with camera in hand—in front of a diner, of course. We are thrilled that last year, Richard donated his entire collection of historic and research materials to The Henry Ford—including thousands of slides, photos, catalogs, postcards, and diner accouterments!

Modern Diner, Pawtucket, RI, 1974 slide. THF296836

Richard not only documented existing diners but helped raise awareness of the need to save diners from extinction. The Modern Diner, shown here, was the first to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places (1978).

Robbins Dining Car, Nantasket, Mass., ca. 1925. THF277072

Be sure to check out our Digital Collections for many items from Richard’s collection already online.

Diners continue to have popular appeal. They offer a portal into 20th-century social mores, habits, and values. Furthermore, they represent examples of American ingenuity and entrepreneurship that connect to small business startups and owners today.

This post was originally part of our weekly #THFCuratorChat series. Follow us on Twitter to join the discussion. Your support helps makes initiatives like this possible.

Additional Readings:

20th century, restaurants, Henry Ford Museum, food, Driving America, diners, by Donna R. Braden, #THFCuratorChat

Until We Meet Again

First of the 2020 crop of Firestone Farm Merino lambs: twins born April 11. A ram and ewe are showing a few of the prized wrinkles.

As I begin my second full year as director of Greenfield Village, I was truly looking forward to welcoming everyone back for our 91st season and sharing the exciting things happening in the village. Instead, as we all face a new reality and a new normal, I would like to share how, even as we have paused so much of our own day-to-day routines, work continues in Greenfield Village.

As we entered the second week of March, signs of spring were everywhere, and the anticipation, along with the preparations for the annual opening of Greenfield Village, were picking up pace. The Greenfield Village team was looking forward to a challenging but exciting year, with a calendar full of exciting new projects.

It's not only about the new stuff, though. We all looked forward to our tried-and-true favorites coming back to life for another season: Firestone Farm, Daggett Farm, Menlo Park, Liberty Craftworks and the calendar of special events, to name a few. Each of these has a special place in our hearts and offers its own opportunities for new learning and perspectives. Despite all our hope and anticipation for this coming year, however, our plans took a different direction.

As our campus closed this past March, it had long been obvious that the year was going to be very different than the one we had planned. The Henry Ford's leadership quickly assessed the daily operations in order to narrow down to essential functions. For most of Greenfield Village, this meant keeping what had been closed for the season closed. Liberty Craftworks, which typically continues to produce glass, pottery and textile items through the winter months, was closed, and the glass furnaces were emptied and shut down. This left the most basic and essential work of caring for the village animals to continue.

Here I am with the Percheron horse Tom at Firestone Barn, summer 1985.

As proud as I am to be director of Greenfield Village, I am equally proud, if not more so, to be part of a small team of people providing daily care for its animals. This work has brought me full circle to my roots as a member of the first generations of Firestone Farmers 35 years ago. It’s amazing to me how quickly the sights, sounds and smells surrounding me in the Firestone Barn bring back the routines I knew so well so long ago. I am also proud of my colleagues who work along with me to continue these important tasks.

The pandemic has not stopped the flow of the seasons and daily life at Firestone Farm. Our team made the decision very soon after we closed to move the group of expecting Merino ewes off-site to a location where they could have around-the-clock care and monitoring as they approached lambing time in early April. This group of nearly 20 is now under the watchful eye of Master Farmer Steve Opp in Stockbridge, Michigan, about 60 miles away.

Meet the newest members of the Firestone Farm family.

After their move, the ewes were given time to settle into their new temporary home. They were then sheared in preparation for lambing, as is our practice this time of year. I am very pleased to report that the first lambs were born Easter weekend, Saturday, April 11. All are doing well, and several more lambs are expected over the next few weeks. Once the lambs are old enough to safely travel, and we have a better understanding of our operating schedule looking ahead, they will all return to Firestone Farm, having the distinction of being the first group of Firestone lambs not born in the Firestone Barn in 35 years.

The last of the Firestone Farm sheep getting sheared in the Firestone Barn.

The wethers, rams and yearling ewes that remain at Firestone Farm were also recently sheared and are ready for the warm weather. One of the wethers sheared out at 18 pounds of wool, which will eventually be processed into a variety of products that are sold in our stores.

Continue Reading

farms and farming, farm animals, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Jim Johnson, Greenfield Village, COVID 19 impact

#InnovationNation: Social Transformation

aviators, flying, presidents, education, books, women's history, Abraham Lincoln, Ford Motor Company, World War II, airplanes, cars, limousines, presidential vehicles, Rosa Parks bus, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

Travel has changed a lot over the past 150 years, from something that only the wealthy could afford to something for everyone. This post looks at the relationship between forms of luggage and methods of transportation, from stagecoaches through airline travel.

THF206455 / Concord Coach Hitched to Four Horses in Front of Post Office, circa 1885.

In the 19th century, travel was relatively uncommon. People who traveled used heavy trunks to carry a great number of possessions, usually by stagecoach and rail. The traveler didn't usually hand his or her luggage, porters did all the work. As late as 1939, railway express companies transferred trunks to a traveler's destination.

THF288917 / Horse-Drawn Delivery Wagon, "Express Trunks Transferred & Delivered, We Meet All Trains"

A typical 19th century American trunk, this example was used by Captain Milton Russell during the Civil War.

THF174670 / Carpet Bag, 1870-1890

People used valises or other types of lighter bags in the 19th century. This is a carpet bag made of remnants of "ingrain" carpet.

THF145224 / Trunk Used for File Storage By Harvey S. Firestone, circa 1930

In the 19th and 20th centuries, "steamer trunks" were used on ocean-going vessels in your state room. It was literally a closet in a box. This example was used by Harvey Firestone to hold important papers.

THF105708 / Loading Luggage into the Trunk of 1939 Ford V-8 Automobile

With the rise of automobile travel, more people had access and suitcases (as we know them) became the norm. Much easier to manager than steamer trunks, they fit a car trunk.

THF166453 / Oshkosh "Chief" Trunk, Used by Elizabeth Parke Firestone, 1920-1955

This is a standard 1920s/1930s suitcase made by the Oshkosh Suitcase Co. of Oshkosh, Wisc. This was for auto travel, etc. It was for everything! This belonged to Elizabeth Parke Firestone.

THF285021 / Passengers Entering Ford Tri-Motor 4-AT Airplane, 1927

With the rise of air travel, passengers were limited to lighter-weight bags due to weight restrictions.

THF169109 / Orenstein Trunk Company Amelia Earhart Brand Luggage Overnight Case, 1943-1950

Famed aviator Amelia Earhart licensed her own line of luggage beginning in 1933. It was marketed as "real 'aeroplane' luggage." It was lightweight and made to last. (Learn more about the famed aviator as an entrepreneur in this expert set.)

THF318431 / Postcard, Plymouth Savoy 4-Door Sedan, 1961-1962

By the 1960s, fashionable Americans bought luggage in colorful sets, like this lady directing the porters. Notice she also has a steamer trunk!

THF154923 / Travelpro Rolling Carry-On Suitcase, 1997

With the explosive growth of air travel in the '80s & '90s, & the growth of airports, travelers needed light and portable bags. Roller bags were the answer. They could be carried on or checked.

THF94783 / American Airlines Duffel Bag, circa 1991

Flight attendants need to carry extremely light bags. This American Airlines tote bag was used by a flight attendant in the 1990s.

How have your luggage choices and preferences evolved over time?

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. These artifacts were originally shared as part our weekly #THFCuratorChat series. Join the conversation! Follow @TheHenryFord on Twitter.

If you’re enjoying our content, consider a donation to The Henry Ford. #WeAreInnovationNation