Posts Tagged agriculture

Resilient Foods, Resourceful People

Members of the Woman's National Farm and Garden Association, 1918. THF288950

Members of the Woman's National Farm and Garden Association, 1918. THF288950

Most Americans rely on grocery stores today. Few remember the time when there was constant demand on people to produce and preserve the grain, vegetables and meat they needed to feed themselves.

Over the last few weeks, self-isolation and social distancing have brought into sharp focus the need to plan for your next meal. Do you do it yourself, heading to your cellar to extract the last potatoes or turnips from the bins, or lift the lid off the sauerkraut crock, or pull down a cured ham from the rafters? Probably not. Do you head to the local market or the grocery store and stock up on fresh supplies to see you through for a few days? Or do you dig into the back of your cupboard and pull out a boxed mix or canned goods.

There’s never been a greater time to be resourceful than now. Last week, we donated food from The Henry Ford’s restaurants and cafeteria to Forgotten Harvest to help support our community after our campus closed this month because of COVID-19.

Looking for inspiration to be resourceful in your kitchen? We've dipped into resources and stories from The Henry Ford's collections to try to help. Explore the differences between home cooking and food resourcefulness today and in the past — from farm fresh and family raised to preserved and prepackaged. These digital resources will help you find inspiration whether it’s breakfast, lunch or dinner. Sort through recipe books, dig out that potato — is it a Burbank?! — and season with that essential preservative, salt, reflect and enjoy.

What are you doing in your kitchens right now to make the most of what’s in your cabinets? Share your examples of resourcefulness by tagging your photos and ideas with #WeAreInnovationNation.

Resilient Foods, Resourceful People

Women and the Land: Agricultural Organizations of WWI

Freedom from Want

Mattox Home

Staples

A Versatile Ingredient (Salt)

What If A Potato Could Change the World of Agriculture?

Summer Staples: Tomato and Corn

Eggs

Eggs (as seen on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation)

Historic Recipe Bank

Bread & Biscuits

Preservation & Processing Foods

Henry J. Heinz: His Recipe for Success

Canning

Refrigerators

Fresh Paper (as seen on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation)

Supply Chains

Horse-Drawn Deliveries

Lunch Wagons: The Business of Mobile Food

Tri-Motor Flying Grocery Store

Alternative Eating & Home Cooking

Farmbot

Food Huggers (as seen on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation)

Individual Artifacts

Swanson Frozen Dinners, 1967

Waffle Iron

Victory Gardens

Macaroni

Bean Pot

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment. Did you find this content useful? Consider making a gift to The Henry Ford.

COVID 19 impact, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, philanthropy, food

A Closer Look: The Champion Egg Case Maker

After the Civil War, urban populations swelled. Until this time, farm families had kept flocks of chickens and gathered eggs for their own consumption, but with increased demand for eggs in growing cities, egg farming grew into a specialized industry. Some families expanded egg production at existing farms, and other entrepreneurs established large-scale egg farms near cities and on railroad lines. Networks developed for shipping eggs from farms to buyers – whether wholesalers, retailers, or individuals operating eating establishments.

While farmers who sold eggs directly to customers carried their products to market in different ways, sellers who shipped eggs to buyers standardized their containers to ensure a consistent product. The standard egg case became an essential and enduring part of the egg industry.

Egg producers initially used different sizes and types of containers to pack eggs for market. As the egg industry developed, standardized cases that held thirty dozen (360) eggs – like this version first patented by J.L. and G.W. Stevens in 1867 – became the norm. THF277733

Egg distributors settled on a lightweight wooden box to hold 30 dozen (360) eggs. The standard case had two compartments that held a total of twelve “flats” – pressed paper trays that held 30 eggs each and provided padding between layers. Retailers who purchased wholesale cases of eggs typically repackaged them for sale by the dozen (though customers interested in larger quantities could – and still can – buy flats of 30 eggs).

The standard egg case held 12 of these pressed paper trays, or “flats,” which held 30 eggs each. THF169534

Some egg shippers purchased premade egg cases from dedicated manufacturers. Others made their own. Enter James K. Ashley, who invented a machine to help people build egg cases to standard specifications. Ashley, a Civil War veteran, first patented his egg case maker in 1896 and received additional patents for improvements to the machine in 1902 and 1925.

James K. Ashley’s patented Champion Egg Case Maker expedited the assembly of standard egg cases.

Ashley’s machine, which he marketed as the Champion Egg Case Maker, featured three vises, which held two of the sides and the interior divider of the egg case steady. Using a treadle, the operator could rotate them, making it easy to nail together the remaining sides, bottom, and top to complete a standard egg case, ready to be stenciled with the seller’s name and filled with flats of eggs for shipment.

Ashley’s first customer was William Frederick Priebe, who, along with his brother-in-law Fred Simater, operated one of the country’s largest poultry and egg shipping businesses. As James Ashley continued to manufacture his egg case machines (first in Illinois, then in Kentucky) in the early twentieth century, William Priebe found rising success as the big business of egg shipping grew ever bigger.

One of James K. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Makers, now in the collections of The Henry Ford. THF169525

James Ashley received some acclaim for his invention. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Maker earned a medal (and, reputedly, the high praise of judges) at the St. Louis World's Exposition in 1904. And in 1908, The Egg Reporter – an egg trade publication that Ashley advertised in for more than a decade – described him as “the pioneer in the egg case machine business” (“Pioneer in His Line,” The Egg Reporter, Vol. 14, No. 6, p 77).

While the machine in the The Henry Ford’s collection no longer manufactures egg cases, it still has purpose – as a keeper of personal stories and a reminder of the complex ways agricultural systems respond to changes in where we live and what we eat.

Additional Readings:

- Henry’s Assembly Line: Make, Build, Engineer

- Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882

- The Wool Carding Machine

farming equipment, manufacturing, food, farms and farming, farm animals, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture

George Washington Carver – Difference Maker

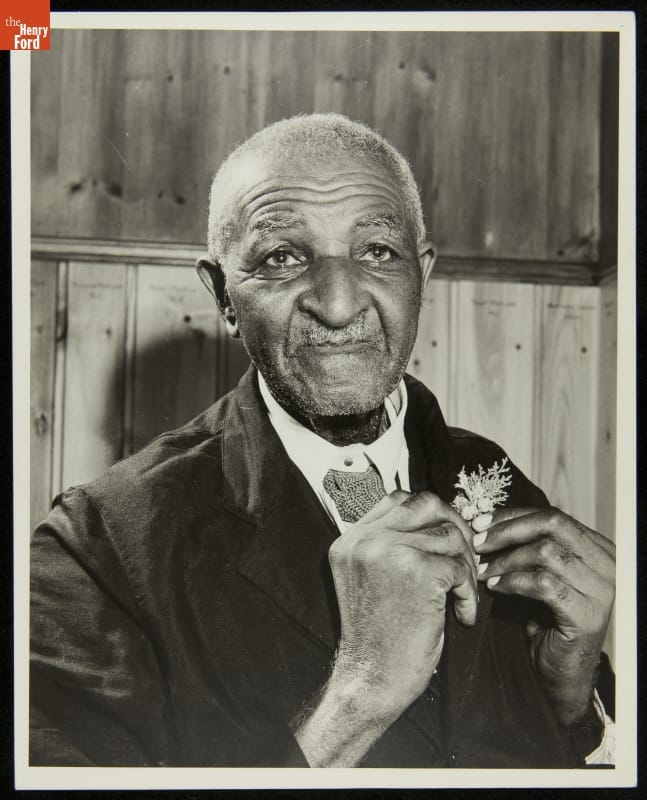

George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, 1939 THF213730

George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, 1939 THF213730

George Washington Carver’s commitment to knowledge, serving the community, and making a difference drove his work as an influential agricultural scientist.

Carver loved plants as a child and studied them his entire life. Despite the many challenges he faced, he earned degrees in agricultural science and gained international recognition for his work.

In 1896, Carver began his 47-year career at Tuskegee Institute, a university in Alabama committed to educating African-Americans. There, he taught agricultural science, managed the school’s experimental farm, and researched better farming practices.

One of the many bulletins Carver produced to help southern farmers THF288047

Carver shared his knowledge through practical instruction, “how-to” publications, and a mobile classroom. His research became the basis for lessons on improving the health and nutrition of the soil as well as the health and well-being of people and the livestock they tended.

Carver understood that farm families who raised cash crops like cotton had little time to grow food for themselves and no extra money to buy it. He identified hundreds of new uses for undervalued food crops like peanuts and sweet potatoes, which increased market opportunities and improved diets.

An interactive digital experience in Henry Ford Museum features the stories of Luther Burbank, Rachel Carson, and George Washington Carver.

Learn more about Carver’s remarkable career in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, where a new digital experience in the Agriculture & the Environment exhibit explores

- Bulletins produced by Carver to help southern farm families

- Carver’s work to create nutrient-rich soil needed to grow healthy crops

- Weeds – an untapped food source Carver liked to call “nature’s vegetables”

- New products Carver developed from crops southern farmers already grew

agriculture, African American history, Henry Ford Museum, George Washington Carver

Bring the Detroit Central Farmers Market to Greenfield Village

The Henry Ford acquired the Vegetable Building from Detroit's Central Farmers Market in 2003, saving it from demolition. Like the farmers markets of today, the Detroit Central Farmers Market was a gathering place – a commercial center, a hub of entrepreneurship and a community space where family, friends, and neighbors congregated and socialized.

This farmers market can become a destination again, a resource for exploring America's agricultural past, present, and future. We need your help to make this happen. #PledgeYourPassion by making a gift this Giving Tuesday.

Vegetable Building at Detroit Central Farmers Market, circa 1888. THF200604

Learn more about the remarkable history of this important structure.

The City of Detroit invested in a new permanent market building - this expansive vegetable hall - in 1860. Located at the east end of Michigan Avenue, just east of Woodward at Campus Martius, it was roughly four blocks square, extending from Woodward to Randolph. The major building in the market was the expansive vegetable building. Market gardeners, florists, orchardists, and nurserymen sold their produce from rented stalls between 1861 and 1893.

The growth of Central Market reflects Detroit’s growth as a city. Much of Detroit’s early history revolved around its importance as a port and strategic location in the Great Lakes. During the 19th century, Detroit’s manufacturing base and its population grew rapidly, more than doubling every 10 years from just 2,222 people in 1830 to 45,619 in 1860. The Central Market was the first Detroit market not located by the docks, reflecting the city’s transition from a port town to a city. Farmers were now coming to Detroit to sell to city residents, rather than to ship produce to eastern cities.

This certified 1884 Sanborn insurance map shows the Central Market area, including the Vegetable Building and other shops.

The Central Farmers Market began in 1843 as a simple shed built off the rear of the old City Hall building. Problems with traffic congestion caused by the market, along with the desire to make the prominent square more presentable, led newly elected Mayor Christian H. Buhl to pledge to build a new covered market building. The city hired local architect John Schaffer to develop plans. Schaffer’s design called for a “structure to be comprised of forty-eight iron columns supporting a wooden roof, [measuring] 70 by 242 feet from outside to outside.” The construction contract was awarded in June to Joel Gray at a cost of $5,312. In late September of 1860, the Detroit Free Press wrote:

“The new market building in the rear of the City Hall is nearly competed and promises to be a fine structure. It covers the whole of the space occupied as a vegetable market, and consists of an open shed, the roof of which is supported on iron columns and a well-finished framework. The roof is of slate and cost about $1,500. It is designed in time to make a tile floor and erect fountains. The building will accommodate all the business of the market and will constitute an ornament as well as a great convenience to that important branch of city commerce.”

Carved wooden ornamentation enhanced the appearance of the market building. THF113542

In its first year, the market earned the city $1,127 in rent, covering 20% of the construction costs in one year. The building thrived as the vegetable market through the 1880s. The emergence of the Eastern Market, and the continuing desire to open the street to traffic, led the Common Council to decide to close the Central Market in 1892. In 1893 the Parks and Boulevards Commission, which operated Belle Isle, received approval to move the building to Belle Isle for use as a horse and vehicle shelter. The building was re-erected on Belle Isle in 1894.

In later years it was converted to a riding stable – the sides were bricked in, the roof was altered to add clerestory windows to let in light, and an office and wash area was constructed in the south end. After the riding stable closed in 1963, the building was used to keep the horses of the Detroit Mounted Police, and then later used for storage. It was considered for demolition since the early 1970s. Over the summer of 2003, the building was dismantled and the parts from the original market building were preserved for re-erection in Greenfield Village.

After the market building was moved to Belle Isle, it was converted to a riding stable. It had been vacant for more than 20 years at the time of this photo. THF113549

The Detroit Central Farmers Market vegetable building is a rare and important building. Because of fires and development pressures, wooden commercial buildings, particularly timber-framed buildings, rarely survive to the present in urban settings. This may be the only 19th century timber-frame market building surviving in the United States. Its move to Belle Isle saved it from demolition.

Historic view of the Detroit Central Farmers Market, taken in the late 1880s. THF96803

The building is architecturally significant. It is an excellent expression of prevailing architectural tastes, as demonstrated by the Free Press review. It captures the rapidly changing world of building construction of the mid-19th century. The building represents the pinnacle of the timber framer’s craft; it is elegantly shaped and ornamented in a way that makes the frame itself the visual keystone of the design. It was built shortly before timber frame construction was eclipsed by the new balloon frame construction, which used dimensional lumber and nailed joints. The cast iron columns that support the timber-framed roof represent the newest in manufactured construction materials. Cast iron was the favorite material of the modern builder in the mid-19th century. It was easy to form into a variety of shapes, and ideal for adding ornamentation to buildings at a moderate cost. The columns in the market building have been formed to represent two different materials – the lower section resembles an elaborately carved stone column, while the upper section looks like the timber frame structure that it supports.

Elegant joinery, supplemented by elaborated carvings, enhances the appearance of the timber frame. THF113530

The cast-iron columns were made to resemble stone below the capital and wood above the capital. THF113505

The building captures the exuberance and optimism of the city of Detroit as it grew in its first wave from a frontier fort and outpost, to an important city. A “useful and beautiful” market building in the city’s central square was important to this image of this growing city – as evidenced by the fact that it took only nine months from Mayor Buhl’s inaugural address of January 11, 1860 promising a new market building, to its substantial completion. Few buildings survive from this first era of growth in the city of Detroit.

For 30 years customers engaged with vendors at the Vegetable Building in Detroit's Central Market. For 110 years the building served the public in a variety of ways on Belle Isle. Your donation will help The Henry Ford rebuild this structure in the heart of Greenfield Village. There it will inspire future generations to learn about their food sources. Make history and #PledgeYourPassion this Giving Tuesday.

Jim McCabe is former Collections Manager at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

Detroit Central Market, shopping, philanthropy, Michigan, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, farms and farming, Detroit, by Jim McCabe, agriculture

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345, Used by Henry Ford. THF140104

In 1882, 19-year-old Henry Ford had an encounter with this little steam engine that changed his life. Though initially unsure of his abilities, he served as engineer, overseeing the maintenance and safe operation of the engine for a threshing crew organized by Wayne County, Michigan farmer John Gleason. He went on to run the engine for the rest of the season, developing the skills and knowledge of an experienced engineer. This assured Henry Ford that machines--not farming--were his future.

Pictured here with the steam engine are (left-to-right) Hugh McAlpine, James Gleason, and Henry Ford. This photograph was taken in 1920 on the Ford Farm in Dearborn. THF199289

Henry Ford never forgot this engine. Three decades later, as head of the world’s largest automobile company, he set out to find it again, sending representatives out scouring the countryside looking for the Westinghouse steam engine, serial number 345. Finally, one of his men found it in a farmer’s field in Pennsylvania. In 1912, Henry Ford purchased it from Carrolton R. Hayes, and had it completely rebuilt. Thereafter, Henry ran it regularly, often in the company of James Gleason, the brother of the man who originally bought it.

Read more content related to The Henry Ford's 90th anniversary here.

Additional Readings:

- Power by the Quarter

- Looking Back to Move Forward

- 1927 Plymouth Gasoline-Mechanical Locomotive

- Electrical Connection

Henry Ford Museum, farms and farming, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, engineering, engines, power, Henry Ford

Solving a Collections Mystery with IMLS

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

As the grant narrative explains, the IMLS funding supports a “critical element in a major institutional project: the consolidation of The Henry Ford's off site collections into a new location on campus.” The work “will improve the physical condition of the project artifacts through conservation treatment, rehousing, and removal to improved environments.” Finally, IMLS funding “will facilitate collections access through the creation of catalog records and digital images, available to all via The Henry Ford's digital collections.”

Occasionally Susan comes upon an artifact that needs additional explanation to accurately catalog it, such as this one. Here's what we knew upon examination:

- It's 16" long, 7" wide

- Has a smooth wooden handle

- Is bent and welded iron

- There's a ringed brass flange positioned to reduce wear where the metal is imbedded into the organic material.

The questions we then ask: What is this instrument? What purpose does it serve?

We turned to our horse experts with the Ford Barn team in Greenfield Village to help us understand its use.

A steady diet of oats, grass, and hay wears a horse’s teeth down as they age. Persistent grinding of food can leave sharp burrs or edges on the outside of their molars. Untreated, this causes pain when the horse chews, and they lose weight.

Farmers and veterinarians used this instrument (called a “gag” or speculum) to hold a horse’s mouth open as they floated the horse’s teeth to balance their bite. Floating helps a horse maintain a healthy bite in their senior years.

A person (farmer or veterinarian) would insert the “gag” into the horse’s mouth, holding it by the handle. Then, the farmer/veterinarian would pull downward on the handle which “encouraged” the horse’s mouth to open. The oval area provided a window through which to place the float (a rasp used to file down the sharp edges).

The device proved useful when treating younger horses with other dental issues, too. Today caring for aging horses still requires floating and balancing their teeth. Caregivers still use a speculum to hold the horse’s mouth open, and to keep their head steady during floating and balancing, but the instruments today have padding to reduce stress on the horse’s jaw during the procedure.

Thanks to the IMLS for providing the invaluable funding to help make this exploration of animal care possible.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Jim Slining is Curator of Museum Collections at Tillers International.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, IMLS grant, healthcare, farm animals, by Jim Slining, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Winter Nature Studies

THF213753 / George Washington Carver at Dedication of George Washington Carver Cabin, Greenfield Village, 1942.

On this day in 1946, George Washington Carver Recognition Day was designated by a joint act of the U.S. Congress and proclaimed by President Harry S. Truman. Carver died just three years earlier on this day in 1943.

Immediately, public officials and the news media began to celebrate his life and create lasting reminders of his work in education, agricultural science, and art. Carver, mindful of his own legacy, had already established the Carver Foundation during the 15th annual Negro History Week, on February 14, 1940, to carry on his research at Tuskegee. It seems fitting to pay respects to Carver on his death day by taking a closer look at the floral beautis that Carver so loved, and that we see around us, even during winter.

Carver recalled that, “day after day I spent in the woods alone in order to collect my floral beautis” [Kremer, ed., pg. 20]. He believed that studying nature encouraged investigation and stimulated originality. Experimentation with plants “rounded out” originality, freedom of thought and action.

THF213747 / George Washington Carver Holding Queen Anne's Lace Flowers, Greenfield Village, 1942.

Carver wanted children to learn how to study nature at an early age. He explained that it is “entertaining and instructive, and is the only true method that leads up to a clear understanding of the great natural principles which surround every branch of business in which we may engage” (Progressive Nature Studies, 1897, pg. 4). He encouraged teachers to provide each student a slip of plain white or manila paper so they could make sketches. Neatness mattered. As Carver explained, the grading scale “only applies to neatness, as some will naturally draw better than others.”

Neatness equated to accuracy, and with accuracy came knowledge. Farm families could vary their diet by identifying additional plants they could eat, and identify challenges that plants faced so they could correct them and grow more for market.

Carver understood how the landscape changed between the seasons, and exploring during winter was just as important as exploring during summer. Thus, it is appropriate to apply Carver’s directions about observing nature to the winter landscape around us, and to draw the winter botanicals that we see, based on directions excerpted from Carver’s Progressive Nature Studies (1897). (Items in parentheses added to prompt winter-time nature study - DAR and DE, 3 Jan 2018.)

- Leaves – Are they all alike? What plants retain their leaves in winter? Draw as many different shaped leaves as you can.

- Stems – Are stems all round? Draw the shapes of as many different stems as you can find. Of what use are stems? Do any have commercial value?

- Flowers (greenhouses/florists) – Of what value to the plant are the flowers?

- Trees – Note the different shapes of several different trees. How do they differ? (Branching? Bark?) Which trees do you consider have the greatest value?

- Shrubs – What is the difference between a shrub and a tree?

- Fruit (winter berries) – What is fruit? Are they all of value?

Carver worked in greenhouses and encouraged others to use greenhouses and hot beds to start vegetables earlier in the planting system. The sooner farm families had fresh vegetables, the more quickly they could reduce the amount they had to purchase from grocery stores, and the healthier the farm families would be.

THF213726 / George Washington Carver in a Greenhouse, 1939.

In 1910, Carver included directions for work with nature studies and children’s gardens over twelve months. Selections from “January” suitable for nearly all southern states” included:

- Begin in this month for spring gardening by breaking the ground very deeply and thoroughly

- Clear off and destroy trash (plant debris) that might be a hiding place for noxious insects.

- Cabbages can be put in hot beds, cold frames, or well-protected places.

- Grape vines, fruit trees, hedges and ornamental trees should receive attention (pruning, fertilizing)

- Both root and top grafting of trees should be done.

THF213314 / Pamphlet, "Nature Study and Children's Gardens," by George Washington Carver, circa 1910.

Carver illustrated his own publications, basing his botanical drawings on what he observed in his field work. He conveyed details that his readers needed to know, be they school children tending their gardens, or farm families trying to raise better crops.

THF213278 / Pamphlet, "Some Possibilities of the Cow Pea in Macon County, Alabama," by George Washington Carver, 1910 / page 12.

Edible wild botanicals, also known as weeds, appeared in late winter. Carver encouraged everyone from his students at Tuskegee to Henry Ford to consumer more wild greens year round, but especially in late winter when greens became a welcome respite from root crops and preserved meats which dominated winter fare. His pamphlet, Nature’s Garden for Victory and Peace, prepared during World War II, featured numerous drawings of edible wild botanicals, also called weeds. Americans could contribute to the war effort by diversifying their diets with these greens that sprouted in the woods during the late winter and early spring. Carver illustrated each wild green, including dandelion, wild lettuce, curled dock, lamb’s quarter, and pokeweed. Following the protocol used in botanical drawing, he credited the source, as he did with several illustrations identified as “after C.M. King.” This referenced the work of Charlotte M. King, who taught botanical drawing at Iowa State University during the time of Carver’s residency there, and who likely influenced Carver’s approach to botanical drawing. King’s original of the “Small Pepper Grass” drawing appeared in The Weed Flora of Iowa (1913), written by Carver’s mentor, botanist Louis Hermann Pammel.

Edible wild botanicals, also known as weeds, appeared in late winter. Carver encouraged everyone from his students at Tuskegee to Henry Ford to consumer more wild greens year round, but especially in late winter when greens became a welcome respite from root crops and preserved meats which dominated winter fare. His pamphlet, Nature’s Garden for Victory and Peace, prepared during World War II, featured numerous drawings of edible wild botanicals, also called weeds. Americans could contribute to the war effort by diversifying their diets with these greens that sprouted in the woods during the late winter and early spring. Carver illustrated each wild green, including dandelion, wild lettuce, curled dock, lamb’s quarter, and pokeweed. Following the protocol used in botanical drawing, he credited the source, as he did with several illustrations identified as “after C.M. King.” This referenced the work of Charlotte M. King, who taught botanical drawing at Iowa State University during the time of Carver’s residency there, and who likely influenced Carver’s approach to botanical drawing. King’s original of the “Small Pepper Grass” drawing appeared in The Weed Flora of Iowa (1913), written by Carver’s mentor, botanist Louis Hermann Pammel.

THF213586 / Pamphlet, "Nature's Garden for Victory and Peace," by George Washington Carver, March 1942.

To learn more about Carver, consult these biographies:

- Hersey, Mark D. My Work is that of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

- Kremer, Gary R. George Washington Carver: A Biography. Santa Barbara, Cal.: Greenwood, 2011.

- Kremer, Gary R. ed. George Washington Carver in His Own Words. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1987.

- McMurry, Linda O. George Washington Carver, Scientist and Symbol. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

To read more about Carver and Nature Study, see:

- Carver, G. W. Progressive Nature Studies. (Tuskegee Institute Print, 1897), Digital copy available at Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/98621#page/132/mode/1up

- Harbster, Jennifer. “George Washington Carver and Nature Study,” blog, March 2, 2015, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2015/03/george-washington-carver-and-nature-study/

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Deborah Evans is Master Presenter at The Henry Ford.

winter, nature, George Washington Carver, education, by Debra A. Reid, by Deborah Evans, art, agriculture, African American history

Seventy-five Years of the George Washington Carver Cabin

This year, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the dedication of the George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village. There is not a great deal of specific information about this project in the archival collections, but here is what we do know.

Henry Ford’s connections and interest in the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute began as early as 1910 when he contributed to the school’s scholarship fund. At this time, George Washington Carver was the head of the Research and Experimental Station there.

Henry Ford always had interests in agricultural science, and as his empire grew, he became even more focused on using natural resources, especially plants, to maximize industrial production. He was especially interested in plant materials that could be grown locally. Carver has similar interest, but his focus was on improving the lives of southern farmers. His greatest fame was that of a “Food Scientist”, though he was also very well known for developing a variety of cotton that was better suited for the growing conditions in Alabama. Through the decades that followed, connections and correspondences were made, but it would not be until 1937 that the two would meet face to face.

Through the 1930s, work and research began to really ramp up in the Research or Soybean Laboratory in Greenfield Village. Various plants with the potential to produce industrial products were researched, but eventually, the soybean became the focus. Processes that extracted oils and fibers became very sophisticated, and some limited production of soy based car parts did take place in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as a result of the work done there.

In 1935, the Farm Chemurgic Council had its very first meeting in Dearborn. This group, formed to study and encourage better use of renewable resources, would meet annually becoming the National Farm Chemurgic Council. It was at the 1937 meeting, also held in Dearborn, that George Washington Carver, and his assistant, Austin Curtis, were asked to speak. Carver was put up in a suite of rooms at the Dearborn Inn, and it was here that he and Henry Ford were able to meet and discuss their ideas for the first time, face to face. During the visit, Ford entertained Carver at Greenfield Village and gave him the grand tour. Carver was also invited to address the students of the Edison Institute Schools. Carver would write to Ford following the visit, “two of the greatest things that have come into my life have come this year. The first was the meeting with you, and to see the great educational project that you are carrying on in a way that I have never seen demonstrated before.”

It was at some point during the visit that Henry Ford put forth the idea of including a building dedicated to George Washington Carver in Greenfield Village. It seems that he asked Carver about his recollections of his birthplace, and went as far as to ask for descriptions and drawings. Later correspondence from Austin Curtis in November of 1937 confirm Ford’s interest. It was determined by that point that the original building that stood on the farm of Moses Carver in Diamond Point, Missouri had long been demolished. Granting Ford’s request, Curtis would go on to supply suggested dimensions and a sketch, to help guide the project. The cabin was described as fourteen feet by eighteen feet with a nine- foot wall, reaching to fourteen feet at the peak of the roof. It included a chimney made of clay and sticks.

A 1937 rendering of the birthplace of George Washington Carver based on his recollections. No artist is attributed, but it is likely this was drawn by Carver. THF113849

It would not be until the spring of 1942 that the project would get underway. The building, very loosely based on the descriptions provided by Carver, would be constructed adjacent to the Logan County Courthouse. In 1935, the two brick slave quarters from the Hermitage Plantation, had been reconstructed on the other side of the courthouse. The grouping was completed with the addition of the Mattox House (thought to be a white overseers house from Georgia) in 1943. As Edward Cutler, Henry Ford’s architect, would state in a 1955 interview, “we had the slave huts, the Lincoln Courthouse, the George Washington Carver House. The emancipator was in between the slaves and the highly- educated man, It’s a little picture in itself.”

There are no records beyond Henry Ford’s requests for information as to how the final design of the building, that now stands in Greenfield Village, was determined. An invoice and correspondence does appear requesting white pine logs, of specific dimensions, from Ford’s Iron Mountain property. There is also an extensive photo documentation of the construction process in the spring and early summer of 1942.

Foundation being set, spring 1942. THF28591

Beginnings of the framing, Spring 1942. THF285293

Logs in place, roof framing in process, spring 1942. THF285285

Newly Completed George Washington Carver Memorial, Early Summer, 1942. THF285295

In the end, the cabin would resemble less of a hard scrabble slave hut, and more of a 1940s Adirondack style cabin that any of us would be proud to have on some property “up north”. It was fitted out with a sitting room, two small bedrooms (with built in bunks), a bathroom, and a tiny kitchen. It was furnished with pre-civil war antiques and was also equipped with a brick fireplace that included a complete set-up for fireplace cooking. As an interesting tribute to Carver, a project, sponsored by the Boy Scouts of America, provided wood representing trees from all 48 states and the District of Columbia to be used as paneling throughout the cabin. Today, one can still see the names of each wood and state inscribed into the panels.

Plans had initially been made for Carver to come for an extended stay in Dearborn in August of 1942, but those plans changed and he arrived on July 19. This was likely due to Carver’s frail health and bouts of illness. While the memorial was being built, extensive plans were also underway for the conversion of the old Waterworks building on Michigan Avenue, adjacent to Greenfield Village, into a research laboratory for Carver. The unplanned early arrival date forced a massive effort into place to finish the work before Carver arrival. Despite wartime restrictions, three hundred men were assigned to the job and it was finished in about a week’s time.

George Washington Carver would stay for two weeks and during his visit, he was given the “royal” treatment. His visit was covered extensively by the press and he made at least one formal presentation to the student of the Edison Institute at the Martha Mary Chapel. During his stay, he resided at the Dearborn Inn, but on July 21, following the dedication of the laboratory and the memorial in Greenfield Village, just to add another level of authenticity to the cabin, Carver spent the night in it.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford at the Dedication of the George Washington Carver National Laboratory, July 21, 1942. THF253993

Edsel Ford, George Washington Carver, and Henry Ford, Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF253989

George Washington Carver at fireplace in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285303

George Washington Carver seated at the table in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285305

Interior views of Carver Memorial, August, 1943. THF285309 and THF285307

The completed George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village c.1943. THF285299

Beginning in 1938, Carver began to suffer from some serious health issues. Pernicious anemia is often a fatal disease and when first diagnosed, there was not much hope for Carver’s survival. He surprised everyone by responding to the new treatments and gaining back his strength. Henry and Clara visited Tuskegee in 1938 for the first time, later, when Henry Ford heard of Carver’s illness, he sent an elevator to be installed in the laboratory where Carver spent most of his time. Carver would profusely thank Ford, calling it a “life saver”. In 1939, Carver visited the Fords at Richmond Hill and visited the school the Fords had built and named for him there. In 1941, the Fords made another visit to Tuskegee to attend the dedication of the George Washington Carver Museum.

During this time, Carver would suffer relapses, and then rebound, each time surprising his doctors. This likely had much to do with his change in travel plans in the summer of 1942. Following his visit to Dearborn, through the fall, there was regular correspondence to Henry Ford. One of the last, dated December 22, 1942, was a thank you for the pair of shoes made by the Greenfield Village cobbler. Following a fall down some stairs, George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943, he was seventy-eight years old.

Carver Memorial in its whitewashed iteration, c.1950. THF285299

It was seventy-five years ago, that George Washington Carver made his last trip to Dearborn. His legacy lives on here, and he remains in the excellent company of those everyday Americans such as Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, and Henry Ford, who despite very ordinary beginnings, went on to achieve extraordinary things and inspire others. His fame lives on today, and even our elementary school- age guests, know of George Washington Carver and his work with the peanut.

Jim Johnson is Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes at The Henry Ford.

Sources Cited

- Bryan, Ford, Friends, Family & Forays: Scenes from the Life & Times of Henry Ford, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2002.

- Edward Cutler Oral Interview, 1955, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- Collection of correspondences between Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, 1937-1943, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- George Washington Carver Memorial Building Boxes, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- The Herald, August, 1942, The Edison Institute, Dearborn, MI

Dearborn, Michigan, farms and farming, agriculture, Henry Ford, by Jim Johnson, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, George Washington Carver, African American history

Agriculture in Today's Classroom

Agriculture is an important collecting focus for The Henry Ford, so we’re very honored to have the Michigan Farm Bureau join us as a partner. Catherine Tuczek, our curator of school and public learning, sat down with Education Specialist Amelia Miller to talk about the importance of agriculture in today’s classroom.

Agriculture is an important collecting focus for The Henry Ford, so we’re very honored to have the Michigan Farm Bureau join us as a partner. Catherine Tuczek, our curator of school and public learning, sat down with Education Specialist Amelia Miller to talk about the importance of agriculture in today’s classroom.Why does it make sense for The Henry Ford and the Michigan Foundation for Agriculture and Michigan Agriculture in the Classroom to partner together?

The Michigan Agriculture in the Classroom program strives to provide educators with standards-based lessons which teach about local agriculture through classroom subjects such as science, social studies, English language arts, math and more. To partner with The Henry Ford allows us a direct link to put these lessons in the hands of the teachers. With the historical agriculture exhibits and The Henry Ford’s focus on innovation, it makes sense to showcase modern agriculture, showing the progression in agricultural technologies throughout time.

Where do most people learn about agriculture these days?

Knowledge of food and agriculture is no different than any other topic. Consumers today turn to social media for information about their food and the way it’s raised. 63% of Michigan consumers say they prefer to purchase products grown and raised in Michigan. Today’s consumer expects transparency between farmers, food processors and consumers. About half of U.S. consumers want to learn about food safety and the impact of food on their health directly from food labels; while about 40% want to learn about animal well-being, environmental impact and business ethics from company websites. (source: Center for Food Integrity)

What are common misconceptions children have about agriculture?

Many students (and parents!) draw conclusions from their immediate surroundings. Less than 2% of the U.S. population live on farms or ranches, with this disconnect comes misconceptions. Often, students guess their milk comes from a grocery store cooler rather than a dairy cow. Careers in agriculture don’t just mean working on a farm, from sales and marketing to plant science to animal health jobs are available in business, biology, mechanics, and more. Today’s agriculturalists are very technology-savvy people. Farmers utilize advancements in plant breeding and genetics to grow more food on less land while utilizing less water, fertilizer and pesticides than ever before. 98% of Michigan farms are family owned rooted in the tradition of raising plants and animals in our Great Lakes state. No matter the size of the farm, these farmers are working to take care of the land, animals, plants and the environment. How can agriculture enrich traditional curriculum like science, social studies, math or English Language Arts?

How can agriculture enrich traditional curriculum like science, social studies, math or English Language Arts?

Agriculture can be the tangible subject which brings any content area to life. With educational trends focusing on inquiry-based learning, agriculture provides a living platform to ask questions or present scenarios. Beginning in preschool, students explore basic plant science through growing seeds, labeling plant parts and drawing conclusions that some plants produce edible fruits or vegetables. Similarly animal science can be integrated into cell biology, nutrition or physiology. When we think about advanced science, we also think about math.  These two foundational concepts go hand in hand as students progress in physics, chemistry and biology all of which are necessary in plant, animal and food science. Agriculture, food and natural resources is Michigan’s second largest economic sector, easily connecting to third and fourth grade social studies. The Mitten State’s unique geography creates many microclimates which allow our state to be the second most diverse food producing state in the nation, growing more than 300 different agricultural commodities. Not to be forgotten, English Language Arts (ELA) can tie all these subjects together. Particularly at elementary levels, reading and ELA is of a primary focus. Utilizing recommended Agriculture Literacy texts and their partnering lesson plans, teachers can pair ELA standards with connecting science standards within one lessons.

These two foundational concepts go hand in hand as students progress in physics, chemistry and biology all of which are necessary in plant, animal and food science. Agriculture, food and natural resources is Michigan’s second largest economic sector, easily connecting to third and fourth grade social studies. The Mitten State’s unique geography creates many microclimates which allow our state to be the second most diverse food producing state in the nation, growing more than 300 different agricultural commodities. Not to be forgotten, English Language Arts (ELA) can tie all these subjects together. Particularly at elementary levels, reading and ELA is of a primary focus. Utilizing recommended Agriculture Literacy texts and their partnering lesson plans, teachers can pair ELA standards with connecting science standards within one lessons. How can agricultural education enrich children’s personal lives?

How can agricultural education enrich children’s personal lives?

There is great reward in seeing the fruits of our own labor. Learning to care for the land or animals is one of our most basic life skills. With trends focusing on unplugging from our electronic device toting society and theories about “Nature-Deficit Disorder” creating the “No Child Left Inside” movement, agriculture education encourages children to learn from the environment. Hands-on lessons focusing on growing plants, caring for animals or studying natural resources gets students out of the classroom. Agriculture education easily caters to all learning styles providing visual, kinesthetic and auditory teaching methods. From early on, society encourages children to consider “what they want to be when they grow up.” While many answers are simple, familiar responses such as firefighter, teacher or doctor, those are just three of the wide world of careers available, each requiring varying levels of post-high school training. Between 2015 and 2020 we expect to see 57,900 average annual openings for graduates with bachelor’s degrees or higher in agriculture. A farmer or veterinarian may be popular career choices amongst children, but reality is agriculture needs scientists, engineers, business managers, marketing professionals, graphic designers, agronomists, animal nutrition specialists, food processors, packaging engineers, mechanics, welders, electricians, educators, and government officials. (source: USDA, AFNR Employment Opportunities)

What are the most important components in agricultural education?

There are five basic groupings of agricultural literacy lessons: Agriculture and the Environment; Plants and Animals for Food, Fiber and Energy; Food, Health and Lifestyle; STEM; and Culture, Society, Economy and Geography. These National Agricultural Literacy Outcomes developed by the National Agriculture in the Classroom Organization focus agriculture learning and assist in aligning lessons with national education standards. If K-12 teachers utilize these groupings when incorporating agriculture into curriculum, students will effectively gain an understanding of agriculture in their daily life.

As with any topic of study, utilizing authentic resources, which are founded in research-based theory is also an important component of agricultural education. Product marketing can often lead consumers astray as to the potential health benefits or risks of food and fiber products. Focusing on teaching accurate agricultural lessons from credible resources will mitigate this confusion in the grocery store aisles.  What are some easy first steps or activities for agricultural education, that a teacher or parent can try?

What are some easy first steps or activities for agricultural education, that a teacher or parent can try?

In Michigan, agriculture is all around us! Ready to go lesson plans paired with state and national standards can be found online from Michigan Agriculture in the Classroom or search more options from the National Agriculture in the Classroom organization. Play learning games on your tablet or computer from My American Farm or visit their educator center for free to download lessons and activities. Gain first-hand knowledge by visiting farm markets around the state, the Michigan 4-H Children’s Garden at MSU, Michigan Grown Michigan Great or any of these Breakfast on the Farm events. Other national organizations such as Nutrients for Life, Journey 2050, Discovery Education, Food Dialogues or Best Food Facts provide great resources for agriculture, food and natural resource learning!

innovation learning, food, philanthropy, educational resources, education, agriculture, by Amelia Miller, by Catherine Tuczek

Making History Come Alive

When I told some of my teacher colleagues that I was planning a field trip to The Henry Ford's Greenfield Village for my world history classes, many reacted with surprise. They asked, “What does Greenfield Village have to do with world history?” At face value, their reaction seems justified. What does the Model T or the Wright Brothers have to do with the development of writing and agriculture? Well, Greenfield Village has the ability to make both ancient and modern history come alive.

With a little creative planning, the buildings and artifacts on display in Greenfield Village were the ideal companion to my current world history unit. I’m teaching about the Neolithic Era of world history, which is from approximately the end of the last Ice Age (10,000 years ago) until about 3,000 BC. The Agricultural Revolution began around 5,000 BC. It is when humanity moved away from hunting and gathering, instead domesticating animals and beginning to plant crops. They also developed tools like the plow and used canals to irrigate crops and fields.

With a little creative planning, the buildings and artifacts on display in Greenfield Village were the ideal companion to my current world history unit. I’m teaching about the Neolithic Era of world history, which is from approximately the end of the last Ice Age (10,000 years ago) until about 3,000 BC. The Agricultural Revolution began around 5,000 BC. It is when humanity moved away from hunting and gathering, instead domesticating animals and beginning to plant crops. They also developed tools like the plow and used canals to irrigate crops and fields.

My students do not have a very concrete understanding of agriculture, as they come from an urban/suburban area. They have seen farms on television and in movies. But they have not had the personal experiences that would bring the agricultural revolution to life.

Fortunately Greenfield Village allowed my students to experience in person a farm that employs principles of the agricultural revolution, like using domesticated animals as a source of power. Using Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village, my colleagues and I constructed a “farm-focused” field trip as a component of our world history course.

The people, animals, and artifacts at Firestone Farm made our world history unit come alive. The employees and volunteers were happy to explain how and why farmers have used and interacted with domesticated animals. The students were excited to see the Merino sheep, draft horses, pigs, and chickens in and around the barnyard at Firestone. They gained a greater understanding of the tools and technology created during the agricultural revolution by examining the plows, seed drills, and other pieces of equipment in the Firestone Barn. Reading about a barn, or seeing one on TV doesn’t compare to actually stepping foot in one. Holding the tools, watching the animals, and smelling the barn did far more to impress upon my students the rigors of farming more than any textbook could.

The Henry Ford is, and should be, a favorite destination for American history field trips. But with the help of The Henry Ford, creative teachers can also make textbooks come alive for STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), art, economics, civics, world history, and English language arts.

Matthew Mutschler is a veteran teacher currently teaching middle school in the Warren Consolidated School District. He has been involved with The Henry Ford for a number of years, and is an alumnus of both The Henry Ford Teacher Fellow Program and the National Endowment for the Humanities Landmarks of American History and Culture workshop America’s Industrial Revolution at The Henry Ford.

This #GivingTuesday consider helping us bring more teachers and students on field trips to The Henry Ford by giving a gift of at least $8.

by Matthew Mutschler, agriculture, education, childhood, teachers and teaching, field trips, #GivingTuesday