Posts Tagged home life

“Like Teaching an Elephant to Tap Dance”: Designing the IBM 5150 Personal Computer

On August 12, 1981, as members of the press gathered in the Waldorf-Astoria ballroom in New York City, one of the largest technology companies in the world was about to make an announcement. At the time, the name “IBM” was mostly associated with the room-sized installations of mainframe computers that the company had become famous for in the 1950s. They cost millions of dollars to purchase, needed their own air-conditioned rooms, and required specially trained staff. They were found in large corporations, universities, and research facilities—but not in a typical home. That was about to change with the introduction of the IBM Model 5150, also known as the IBM PC.

An IBM 5150 PC, circa 1984. / THF156040

The idea of internally producing a small, affordable computer was at odds with IBM’s corporate culture. One naysayer remarked that “IBM bringing out a personal computer would be like teaching an elephant to tap dance." Nonetheless, a development team was formed, and the lofty goal of completing the project in one short year was established. “Project Chess” began its race toward the finish line. The team of twelve was fronted by Don Estridge and Mark Dean, who designed the ISA bus (an interface allowing easy expansion of memory and peripherals) and color graphics system.

Part of the success story of designing the 5150 in such a short span of time is an exception to a long-standing IBM company rule: the engineers were allowed to include technology made by outside companies, rather than building every aspect of the PC, from the ground up, themselves. This is why the IBM PC uses an Intel 8088 microprocessor, can run on Microsoft DOS, and is compatible with software made by other companies. It was also released under an open architecture model—a philosophy that would soon lead to a flood of PC-inspired “clones.”

An Atari 800 computer: an early attempt by a video game company to harness the home computing market. / THF155976

In truth, the IBM PC was not the first small home computer, and by entering this market, the company would face competition from Commodore, Atari, Tandy, and Apple—all of whom had produced successful microcomputers beginning in the mid-1970s. To match the wide reach of these rivals, IBM sold their machines at convenient retailers like Sears and ComputerLand. Importantly, it was affordable by 1981 standards at an introductory price of $1,565. And… it fit on your desktop.

A positive effect of IBM creating a PC is that it helped to legitimize the notion of home computers beyond specialists and the home hobbyist crowd. IBM was essentially a well-recognized “heritage brand” by 1981, so the type of consumers reluctant to invest in a computer produced by a scrappy start-up were suddenly scrambling to put deposits down for a 5150. Whereas as “young” computing companies (many of which started out as video game companies) were under threat of being swallowed up in a competitive market, IBM projected an aura of measured reliability and was trusted to stick around.

A button advertising the IBM PC. / THF323543

Ironically, while IBM’s plan was to break out of the office and into the home, PCs were purchased in bulk by businesses to populate desks and cubicles. A visual unity was established in office environment—fields of putty gray and beige personal computers.

The IBM 5150 arrived at an important “boom” moment in computing history. It is evidence of an established company challenging its established design modes by harnessing emerging technologies. And IBM’s decision to pivot proved to be a timely decision too, since affordable microprocessors began to render behemoth, expensive mainframes largely obsolete. But most importantly, the IBM PC—and the wave of computers like it that followed—were designed with the non-specialist in mind, helping to make the personal computer an everyday device in people’s homes.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications and Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

New York, 20th century, 1980s, technology, home life, computers, by Kristen Gallerneaux

Mowtron: The Mower That “Mows While You Doze”

Lawn care takes commitment. Implements designed to reduce the time required to improve a lawn's appearance hit the commercial market during the mid-1800s. Push-powered lawn mowers in a variety of configurations from that era gave way to motorized models, with riding mowers gaining popularity in the 1950s. (For more on the evolution of lawn mowers, check out this expert set.) The American Marketing and Sales Company (AMSC) went one step further in the 1970s. AMSC’s autonomous Mowtron mower, the company proclaimed, “Mows While You Doze.”

Mowtron Mower, 1974. / THF186471

AMSC released the futuristic mower, invented in 1969 by a man named Tyrous Ward, in Georgia in 1971. Its designers retained the familiar form of a riding mower, even incorporating a fiberglass “seat”—though no rider was needed. But Mowtron’s sleek, modern lines and atomic motif symbolized a new day in lawn care.

If the look of the mower promised a future with manicured lawns that required minimal human intervention, Mowtron’s underground guidance system delivered on that promise. Buried copper wire, laid in a predetermined pattern, operated as a closed electrical circuit when linked to an isolation transformer. This transistorized system directed the self-propelled, gasoline-powered mower, which, once started, could mow independently and then return to the garage.

Components of Mowtron’s transistorized guidance system. / THF186481, THF186480, and THF186478

AMSC understood that despite offering the ultimate in convenience, Mowtron would be a tough sell. To help convince skeptical consumers to adopt an unfamiliar technology, the company outfitted Mowtron with safety features, such as sensitized bumpers that stopped the mower when it touched an obstacle, and armed its sales force with explanatory material.

Mowtron’s market expanded from Georgia throughout the early 1970s. The Mowtron equipment and related materials in The Henry Ford’s collection belonged to Hubert Wenzel, who worked as a licensed Mowtron dealer as a side job. Wenzel had two Mowtron systems: he displayed one at lawn and garden shows and installed another as the family mower at his homes in New Jersey and Indiana. Wenzel’s daughter recalled cars stopping on the side of the road to watch whenever it was out mowing the lawn.

Display used by Mowtron dealer Hubert Wenzel. / THF623554, detail

Mowtron sales were never brisk—in fact, Hubert Wenzel never sold a mower—but company records show that the customers willing to try the new technology appreciated Mowtron’s styling, convenience, and potential cost savings. One owner compared her mower to a sleek Italian sports car. Another expressed pleasure at the ease of starting the mower before work and returning home to a fresh-cut yard. And one customer figured his savings in lawn care costs would pay for the machine in two years (Mowtron retailed at around $1,000 in 1974, including installation).

Despite its limited commercial success, the idea behind Mowtron had staying power. Today, manufacturers offer autonomous mowers in new configurations that offer the same promise: lawn care at the push of a button. (Discover one modern-day entrepreneur’s story on our YouTube channel.)

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture & the Environment at The Henry Ford. Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Georgia, 20th century, 1970s, technology, lawn care, home life, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, autonomous technology

“Whenever Henry Ford visited England, he always liked to spend a few days in the Cotswold Country, of which he was very fond … during these sojourns I had many happy times driving Mr. Ford around the lovely scenes which abound in this part of Britain.”

—Herbert Morton, Strange Commissions for Henry Ford

A winding road through a Cotswold village, October 1930. / THF148434, detail

The Cotswolds Catch Henry Ford’s Eye

Henry Ford loved the Cotswolds, a rural region in southwest England—nearly 800 square miles of rolling hills, pastures, and small villages.

During the Middle Ages, a vibrant wool trade brought the Cotswolds great prosperity—at its heart was a breed of sheep known as Cotswold Lions. For centuries, the Cotswold region was well-known throughout Europe for the quality of its wool. Raising sheep, trading in wool, and woolen cloth fueled England’s economic growth from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution. Cotswold’s prosperity and its rich belt of limestone that provided ready building material resulted in a distinctive style of architecture: limestone homes, churches, shops, and farm buildings of simplicity and grace.

During Henry Ford’s trips to the Cotswolds in the 1920s, he became intrigued with the area’s natural beauty and charming architecture—all those lovely stone buildings that “blossomed” among the verdant green countryside and clustered together in Cotswold’s picturesque villages. By early 1929, Ford had decided he wanted to acquire and move a Cotswold home to Greenfield Village.

A letter dated February 4, 1929, from Ford secretary Frank Campsall described that Ford was looking for “an old style that has not had too many changes made to it that could be restored to its true type.” Herbert Morton, Ford’s English agent, was assigned the task of locating and purchasing a modest building “possessing as many pretty local features as might be found.” Morton began to roam the countryside looking for just such a house. It wasn’t easy. Cotswold villages were far apart, so his search covered an extensive area. Owners of desirable properties were often unwilling to sell. Those buildings that were for sale might have only one nice feature—for example, a lovely doorway, but no attractive window elements.

Cotswold Cottage (buildings shown at left) nestled among the rolling hills in Chedworth, 1929–1930. / THF236012

Herbert Morton was driving through the tiny village of Lower Chedworth when he saw it. Constructed of native limestone, the cottage had “a nice doorway, mullions to the windows, and age mellowed drip-stones.” Morton knew he had found the house he had been looking for. It was late in the day, and not wanting to knock on the door and ask if the home was for sale, Morton returned to the town of Cheltenham, where he was staying.

The next morning Morton strolled along a street in Cheltenham, pondering how to approach the home’s owner. He stopped to look into a real estate agent’s window—and saw a photograph of the house, which was being offered for sale! Later that day, Morton arrived in Chedworth, and was greeted by the owner, Margaret Cannon Smith, and her father. The cottage, constructed out of native limestone in the early 1600s, had begun life as a single cottage, with the second cottage added a bit later.

Interior of Cotswold Cottage, 1929-1930. / THF236052

The home was just as quaint inside—large open fireplaces with the mantels supported on oak beams. Heavy oak beams graced the ceilings and the roof. Spiral stone staircases led to the second floor. Morton bought the house and the two acres on which it stood under his own name from Margaret Smith in April 1929 for approximately $5000. Ford’s name was kept quiet. Had the seller been aware that the actual purchaser was Henry Ford, the asking price might have been higher.

Cotswold Cottage (probably built about 1619) as it looked when Herbert Morton spotted it, 1929–1930. / THF236020

“Perfecting” the Cotswold Look

Over the next several months, Herbert Morton and Frank Campsall, Ford’s personal secretary, traded correspondence concerning repairs and (with the best of intentions on Ford’s part) some “improvements” Ford wanted done to the building: the addition of architectural features that best exemplified the Cotswold style. Morton sent sketches, provided by builder and contractor W. Cox-Howman from nearby Stow-on-the-Wold, showing typical Cotswold architectural features not already represented in the cottage from which to choose. Ford selected the sketch which offered the largest number of typical Cotswold features.

Ford’s added features on the left cottage included a porch (a copy of one in the Cotswold village of Rissington), a dormer window, a bay window, and a beehive oven.

Cotswold Cottage, 1929–1930, showing modifications requested by Henry Ford: the beehive oven, porch, and dormer window. / THF235980

Bay window added to the left cottage by Henry Ford (shown 1929–1930). Iron casement windows were added throughout. / THF236054

The cottage on the right got a doorway “makeover” and some dove-holes. These holes are commonly found in the walls of barns, but not in houses. It would have been rather unappealing to have bird droppings so near the house!

Ford’s modifications to the right cottage—a new doorway (top) and dove-holes (bottom) on the upper wall. / THF236004, THF235988

Cotswold Cottage, now sporting Henry Ford’s desired alterations. / THF235984

Ford wanted the modifications completed before the building was disassembled—perhaps so that he could establish the final “look” of the cottage, as well as be certain that there were sufficient building materials. The appearance of the house now reflected both the early 1600s and the 1920s—each of these time periods became part of the cottage’s history. Ford’s additions, though not original to the house, added visual appeal.

The modifications were completed by early October 1929. The land the cottage stood on was transferred to the Ford Motor Company and later sold.

Cotswold Cottage Comes to America

Cotswold Cottage being disassembled. / THF148471

By January 1930, the dismantling of the modified cottage was in process. To carry out the disassembly, Morton again hired local contractor W. Cox-Howman.

Building components being crated for shipment to the United States. / THF148475

Doors, windows, staircases, and other architectural features were removed and packed in 211 crates.

Cotswold building stones ready for shipment in burlap sacks. / THF148477

The building stones were placed in 506 burlap sacks.

Cotswold barn and stable on original site, 1929–1930. / THF235974

The adjacent barn and stable, as well as the fence, were also dismantled and shipped along with the cottage.

Hauled by a Great Western Railway tank engine, 67 train cars transported the materials from the Cotswolds to London to be shipped overseas. / THF132778

The disassembled cottage, fence, and stable—nearly 500 tons worth—were ready for shipment in late March 1930. The materials were loaded into 67 Great Western Railway cars and transported to Brentford, west London, where they were carefully transferred to the London docks. From there, the Cotswold stones crossed the Atlantic on the SS London Citizen.

As one might suspect, it wasn’t a simple or inexpensive move. The sacks used to pack many of the stones were in rough condition when they arrived in New Jersey—at 600 to 1200 pounds per package, the stones were too heavy for the sacks. So, the stones were placed into smaller sacks that were better able to withstand the last leg of their journey by train from New Jersey to Dearborn. Not all of the crates were numbered; some that were had since lost their markings. One package went missing and was never accounted for—a situation complicated, perhaps, by the stones having been repackaged into smaller sacks.

Despite the problems, all the stones arrived in Dearborn in decent shape—Ford’s project manager/architect, Edward Cutler, commented that there was no breakage. Too, Herbert Morton had anticipated that some roof tiles and timbers might need to be replaced, so he had sent some extra materials along—materials taken from old cottages in the Cotswolds that were being torn down.

Cotswold “Reborn”

In April 1930, the disassembled Cotswold Cottage and its associated structures arrived at Greenfield Village. English contractor Cox-Howman sent two men, mason C.T. Troughton and carpenter William H. Ratcliffe, to Dearborn to help re-erect the house. Workers from Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant also came to assist. Reassembling the Cotswold buildings began in early July, with most of the work completed by late September. Henry Ford was frequently on site as Cotswold Cottage took its place stone-by-stone in Greenfield Village.

Before the English craftsmen returned home, Clara Ford arranged a special lunch at the cottage, with food prepared in the cottage’s beehive oven. The men also enjoyed a sight-seeing trip to Niagara Falls before they left for England in late November.

By the end of July 1930, the cottage walls were nearly completed. / THF148485

On August 20, 1930, the buildings were ready for their shingles to be put in place. The stone shingles were put up with copper nails, a more modern method than the wooden pegs originally used. / THF148497

Cotswold barn, stable, and dovecote, photographed by Michele Andonian. / THF53508

Free-standing dovecotes, designed to house pigeons or doves which provided a source of fertilizer, eggs, and meat, were not associated with buildings such as Cotswold Cottage. They were found at the homes of the elite. Still, for good measure, Ford added a dovecote to the grouping about 1935. Cutler made several plans and Ford chose a design modeled on a dovecote in Chesham, England.

Henry and Clara Ford Return to the Cotswolds

The Lygon Arms in Broadway, where the Fords stayed when visiting the Cotswolds. / THF148435, detail

As reconstruction of Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village was wrapping up in the fall of 1930, Henry and Clara Ford set off for a trip to England. While visiting the Cotswolds, the Fords stayed at their usual hotel, the Lygon Arms in Broadway, one of the most frequently visited of all Cotswold villages.

Henry (center) and Clara Ford (second from left) visit the original site of Cotswold Cottage, October 1930. / THF148446, detail

While in the Cotswolds, Henry Ford unsurprisingly asked Morton to take him and Clara to the site where the cottage had been.

Cotswold village of Stow-on-the-Wold, 1930. / THF148440, detail

At Stow-on-the-Wold, the Fords called on the families of the English mason and carpenter sent to Dearborn to help reassemble the Cotswold buildings.

Village of Snowshill in the Cotswolds. / THF148437, detail

During this visit to the Cotswolds, the Fords also stopped by the village of Snowshill, not far from Broadway, where the Fords were staying. Here, Henry Ford examined a 1600s forge and its contents—a place where generations of blacksmiths had produced wrought iron farm equipment and household objects, as well as iron repair work, for people in the community.

The forge on its original site at Snowshill, 1930. / THF146942

A few weeks later, Ford purchased the dilapidated building. He would have it dismantled, and then shipped to Dearborn in February 1931. The reconstructed Cotswold Forge would take its place near the Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village.

To see more photos taken during Henry and Clara Ford’s 1930 tour of the Cotswolds, check out this photograph album in our Digital Collections.

Cotswold Cottage Complete in Greenfield Village—Including Wooly “Residents”

Completed the previous fall, Cotswold Cottage is dusted with snow in this January 1931 photograph. Cotswold sheep gather in the barnyard, watched over by Rover, Cotswold’s faithful sheepdog. (Learn Rover's story here.) / THF623050

A Cotswold sheep (and feline friend) in the barnyard, 1932. / THF134679

Beyond the building itself, Henry Ford brought over Cotswold sheep to inhabit the Cotswold barnyard. Sheep of this breed are known as Cotswold Lions because of their long, shaggy coats and faintly golden hue.

Cotswold Cottage stood ready to welcome—and charm—visitors when Greenfield Village opened to the public in June 1933. / THF129639

By the Way: Who Once Lived in Cotswold Cottage?

Cotswold Cottage, as it looked in the early 1900s. From Old Cottages Farm-Houses, and Other Stone Buildings in the Cotswold District, 1905, by W. Galsworthy Davie and E. Guy Dawber. / THF284946

Before Henry Ford acquired Cotswold Cottage for Greenfield Village, the house had been lived in for over 300 years, from the early 1600s into the late 1920s. Many of the rapid changes created by the Industrial Revolution bypassed the Cotswold region and in the 1920s, many area residents still lived in similar stone cottages. In previous centuries, many of the region’s inhabitants had farmed, raised sheep, worked in the wool or clothing trades, cut limestone in the local quarries, or worked as masons constructing the region’s distinctive stone buildings. Later, silk- and glove-making industries came to the Cotswolds, though agriculture remained important. By the early 1900s, tourism became a growing part of the region’s economy.

A complete history of those who once occupied Greenfield Village’s Cotswold Cottage is not known, but we’ve identified some of the owners since the mid-1700s. The first residents who can be documented are Robert Sley and his wife Mary Robbins Sley in 1748. Sley was a yeoman, a farmer who owned the land he worked. From 1790 at least until 1872, Cotswold was owned by several generations of Robbins descendants named Smith, who were masons or limeburners (people who burned limestone in a kiln to obtain lime for mixing with sand to make mortar).

As the Cotswold region gradually evolved over time, so too did the nature of some of its residents. From 1920 to 1923, Austin Lane Poole and his young family owned the Cotswold Cottage. Medieval historian, fellow, and tutor at St. John’s College at Oxford University (about 35 miles away), Poole was a scholar who also enjoyed hands-on work improving the succession of Cotswold houses that he owned. Austin Poole had gathered documents relating to the Sley/Robbins/Smith families spanning 1748 through 1872. It was these deeds and wills that revealed the names of some of Cotswold Cottage’s former owners. In 1937, after learning that the cottage had been moved to Greenfield Village, Poole gave these documents to Henry Ford.

In 1926, Margaret Cannon Smith purchased the house, selling it in 1929 to Herbert Morton, on Henry Ford’s behalf.

“Olde English” Captures the American Imagination

At the time that Henry Ford brought Cotswold Cottage to Greenfield Village, many Americans were drawn to historic English architectural design—what became known as Tudor Revival. The style is based on a variety of late Middle Ages and early Renaissance English architecture. Tudor Revival, with its range of details reminiscent of thatched-roof cottages, Cotswold-style homes, and grand half-timbered manor houses, became the inspiration for many middle-class and upper-class homes of the 1920s and 1930.

These picturesque houses filled suburban neighborhoods and graced the estates of the wealthy. Houses with half-timbering and elaborate detail were often the most obvious examples of these English revival houses, but unassuming cottage-style homes also took their place in American towns and cities. Mansion or cottage, imposing or whimsical, the Tudor Revival house was often made of brick or stone veneer, was usually asymmetrical, and had a steep, multi-gabled roof. Other characteristics included entries in front-facing gables, arched doorways, large stone or brick chimneys (often at the front of the house), and small-paned casement windows.

Edsel Ford’s home at Gaukler Pointe, about 1930. / THF112530

Henry Ford’s son Edsel and his wife Eleanor built their impressive but unpretentious home, Gaukler Pointe, in the Cotswold Revival style in the late 1920s.

Postcard, Postum Cereal Company office building in Battle Creek, Michigan, about 1915. / THF148469

Tudor Revival design found its way into non-residential buildings as well. The Postum Cereal Company (now Post Cereals) of Battle Creek, Michigan, chose to build an office building in this centuries-old English style.

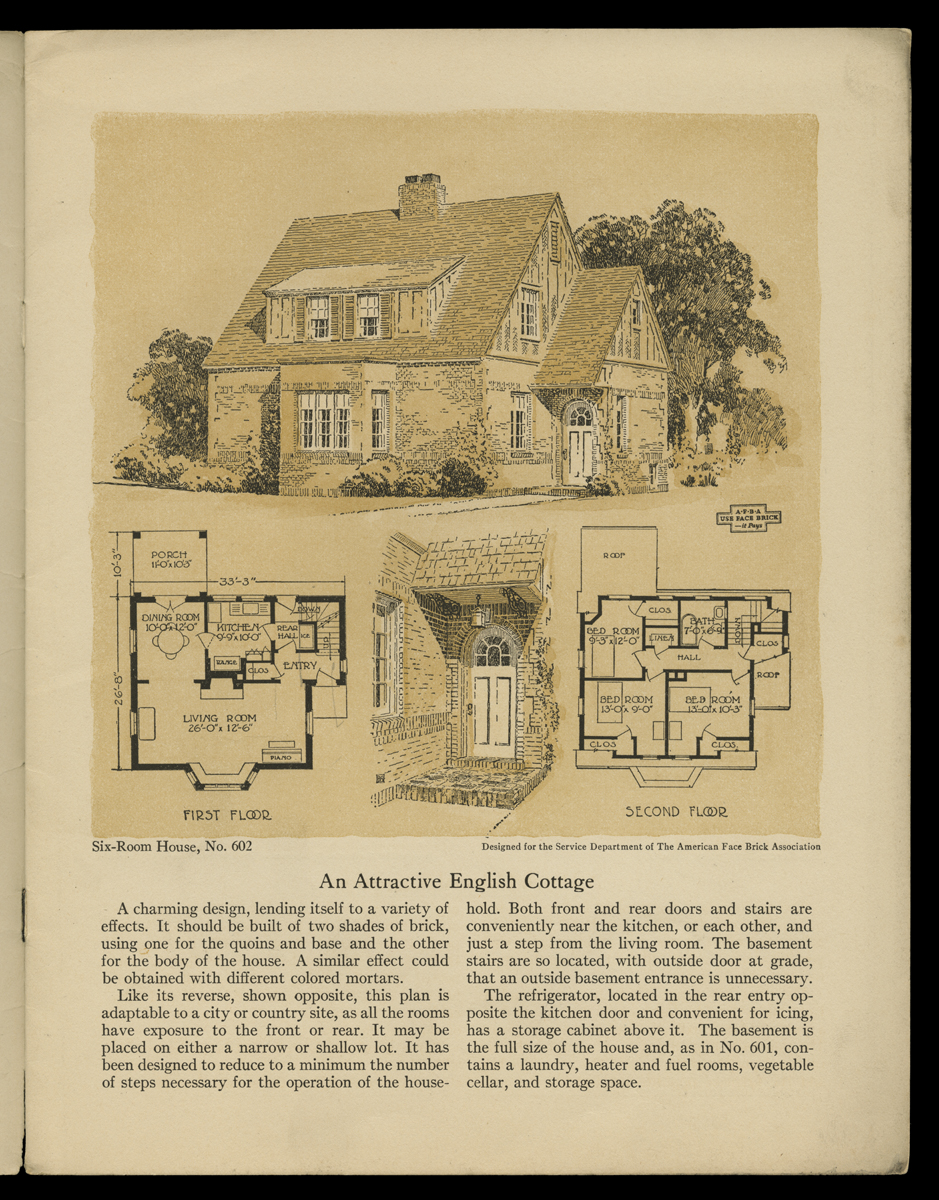

Plan for “An Attractive English Cottage” from the American Face Brick Association plan book, 1921. / THF148542

Plans for English-inspired homes offered by Curtis Companies Inc., 1933. / THF148549, THF148550, THF148553

Tudor Revival homes for the middle-class, generally more common and often smaller in size, appeared in house pattern books of the 1920s and 1930s.

Sideboard, part of a dining room suite made in the English Revival style, 1925–1930. / THF99617

The Tudor Revival called for period-style furnishings as well. “Old English” was one of the most common designs found in fashionable dining rooms during the 1920s and 1930s.

Christmas card, 1929. / THF4485

Even English-themed Christmas cards were popular.

Cotswold Cottage—A Perennial Favorite

Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF53489

Henry Ford was not alone in his attraction to the distinctive architecture of the Cotswold region and the English cottage he transported to America. Cotswold Cottage remains a favorite with many visitors to Greenfield Village, providing a unique and memorable experience.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Cotswold Cottage Tea

- Interior of Cotswold Cottage at its Original Site, Chedworth, Gloucestershire, England, 1929-1930

- Cotswold Cottage

home life, design, farm animals, travel, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village, by Jeanine Head Miller

Flowers: Deep Roots

Trade Card for Choice Flower Seeds, D.M. Ferry & Co., 1880-1900 / THF214403

Sustenance is not usually associated with flowers or the horticultural industry, but cut flowers and ornamental plants have been nourishing humans for centuries. Flowers aid people through hard times by providing joy, mental health benefits, and ephemeral beauty unmatched in many eyes. Additionally, cut flower cultivation is a critical source of revenue and ecosystem service for agricultural entrepreneurs.

Stereograph of a blooming tree peony, circa 1865 / THF66255

The horticulture industry grew rapidly during the 19th century. New businesses, such as Mount Hope Nursery and Gardens out of Rochester, New York, used an expanding transportation infrastructure to market ornamental plants to Midwesterners starting during the 1840s. Yet, while consumers’ interest in ornamentation grew, so did their displeasure with distant producers distributing plants of unverifiable quality. Soon enough, local seed companies and seedling and transplant growers met Detroiters’ needs, establishing greater levels of trust between producer and consumer (Lyon-Jenness, 2004). D.M. Ferry & Co., established in Detroit in 1867, sold vegetable and flower seeds, as well as fruit tree grafts, direct to consumers and farmers.

At the heart of horticulture lies a tension between respect for local, native species and the appeal of newly engineered, “perfect” cultivars. Entrepreneurs such as Hiram Sibley invested in the new and novel, building fruit, vegetable, and flower farms, as well as distribution centers, in multiple states.

Hiram Sibley & Co. Seed Box, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888 / THF181542

Plant breeders such as Luther Burbank sought a climate to support year-round experimentation. As a result, he relocated from Massachusetts to California, where he cultivated roses, crimson poppies, daisies, and more than 800 other plants over the decades. Companies in other parts of the country—Stark Bro’s Nurseries & Orchards Co. in Louisiana, Missouri, and the W. Atlee Burpee Company in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—partnered with Burbank or established their own California operations to maintain a competitive edge. These larger farms had to send their flowers by rail across the country and as such, engineered for consistency and mass production.

Field of Burbank's Rosy Crimson Escholtzia, April 13, 1908, Santa Rosa, California. / THF277209

Advertising fueled growth. Companies marketed seeds directly to homeowners, farmers, and market gardeners through a combination of colorful packets, seed boxes, catalogs, specimen books, trade cards, and purchasing schemes. Merchants could reference colorful trade literature issued by D.M. Ferry & Company as they planned flower seed purchases for the next year. The 1879 catalog even oriented merchants to its seed farms and trial grounds near Detroit. A D.M. Ferry trade card (seen below) advertised more than the early flowering sweet pea (Lathyrus odoratus) in 1889, featuring twelve “choice kinds” available in Ferry seed boxes or through orders submitted by merchants directly to the company (Little and Kantor, Journal of Heredity, 1941). Customers who returned ten empty seed packets earned a copy of Ferry’s Floral Album.

Trade Card for Sweet Pea Seeds, D.M. Ferry & Company, 1889. / THF214415

Additionally, magazines such as Vick’s Illustrated Family Magazine, published by Rochester, New York, seedsman James Vick, served as a clearinghouse of information for consumers and growers alike.

Floral lithographs by James Vick / Digital Collections

Flowers were not always grown in isolation. Cultivating and selling vegetables side-by-side with flowers was common practice, as it provided farmers diversity in income with the ebb and flow of seasons. The addition of flowers proved mutually beneficial to both profits and productivity for farms, as they attract pollinators and receive a high mark-up in the market. Furthermore, flowers could be placed alongside vegetables on farm stands as a means to decorate and draw the attention of market goers.

Market gardeners who also grew flowers saw the potential in Detroit, and this helped develop the floriculture industry. John Ford, a Scottish immigrant, gained visibility through his entries at the Annual Fair of Michigan State Agricultural Society, winning awards for cut flowers, dahlias, and German asters, as well as culinary vegetables, strawberries, and nutmeg melons, throughout the 1850s and 1860s (The Michigan Farmer, 1855, 1856, 1857, 1858, 1861/62, 1863/64). Ford served on the Detroit City Common Council. After that body approved construction, in 1860, of a new Vegetable Shed for Detroit’s City Hall Market (also known as Central Market), Ford or members of his family operated a stand in the market until at least 1882.

Nurseryman's Specimen Book, 1871-1888, page 76 / THF620239

Another market gardener, John Breitmeyer, an immigrant from Bavaria, settled in Detroit in 1852 and grew a booming floral business. He anticipated the growth of the floral industry, building hot houses for roses in 1886 and establishing the first florist shop in Detroit in 1890 off Bates Street (The American Florist, April 28, 1900, pg. 1213). He worked with his two sons, who had studied floriculture in Philadelphia, to raise plants and flowers, but “the latter seemed the most profitable” (Detroit Journal, reprinted in Fort Worth Daily Gazette, August 12, 1889, pg. 4). There were 200 floral shops in Detroit by 1930, when the Breitmeyer family operation grew to specialize in “chrysanthymums [sic], carnations, and sweet peas” in addition to roses (Detroit Free Press, April 6, 1930).

Detroit City Business Directory, Volume II, 1889-1890, page 125 / THF277531

Florists sold cut flowers to satisfy consumers willing to part with hard-earned money on such temporary satisfaction. Many factors influenced their decisions: weddings, funerals, and other rites of passage; brightening a home interior; thanking a host; or treating a sweetheart. Whatever the reason, Breitmeyer and Ford and others responded to the zeal for floral ornamentation.

Memorial Floral Arrangement, circa 1878 / THF210195

The Michigan Farmer encouraged readers to “bring a few daisies and butter-cups from your last field walk, and keep them alive in a little water; aye, preserve but a branch of clover, or a handful of flower grass—one of the most elegant, as well as cheapest of nature’s productions and you have something on your table that reminds you of the beauties of God’s creation, and gives you a link with the poets and sages that have done it most honor. Put but a rose, or a lily, or a violet, on your table, and you and Lord Bacon have a custom in common.” (July 1863, pg. 32). Though the preferences varied, flowers inside the home were simultaneously a luxury and something that everyday people could afford, and connected them to poets and lords.

Publications encouraged the trade through how-to columns on decorating with flowers. This clipping from the Michigan Farmer explained how to construct a centerpiece featuring cut flowers.

Description of simple DIY floral ornaments in the household. Excerpt from Michigan Farmer, August, 1863/64, pg. 84. / Image via HathiTrust

What types of flowers might growers raise to fill their baskets and ornament their tables? The Michigan Farmer indicated that “no garden” should be without dahlias “as a part of its autumn glory” (April 1857, pg. 115) and that growers should “never be without” a Moutan peony (February 1858, pg. 48).

Urban markets featured many more plants and cut flowers to satisfy consumer demand. The Detroit News reported in May 1891 that “tulips of every hue and the modest daisy or bachelor’s button still linger on the stalls, but they are the first floral offerings of the spring, and their day is now about over.” The florists rapidly restocked, filling their southern row of stalls in the vegetable market with “floral radiance and beauty…. The hydrangeas with their pink or snow-white balls; fuchsias, with their bell-like cups and purple hearts; geraniums, in all the colors of the rainbow; the heliotrope, with its light-pink blossom; the begonia, with its wax green leaves; verbenas in pink, purple and white; the marguerite, with its white and yellow star; the kelseloria [Calceolaria] in blushing red or golden yellow; the modest mignonette, with its neutral tints but exquisite perfume; and the blue and fragrant forget-me-not” (“Seen on the Streets,” May 24, 1891).

Florists stood at the ready to satisfy customers’ needs, especially for a beau seeking a bouquet to woo his lover (Detroit Free Press, June 19, 1870). On one occasion, a woman reluctantly bought sunflower seeds and catnip instead of climbers that would make her house look “almost like Paradise,” fearing that this ornamentation would cause the landlord to raise her rent (Detroit Free Press, April 27, 1879). In other instances, men “commissioned” by their wives stopped by the flower stands in Central Market, perusing “roses, pansies, and hyacinth bulbs” (Detroit Free Press, January 10, 1890).

Shoppers at Central Market crowd around potted lilies and cut flowers wrapped in paper, undated (BHC glass neg. no. 1911). / Image from Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library (EB02e398)

By the late 19th century, customers had many options to satisfy their appetite for flowers. Many Detroiters purchased their flowers and ornamental plants at the Vegetable Building in Central Market. One huckster turned florist, Mary Judge, engaged customers at her Central Market floral stand with a pretty rose bush for a quarter (not 20 cents, or she’d make no profit), geraniums for 10 cents, or a “beyutiful little flower” for 5 cents (Detroit News, May 24, 1891).

They could also frequent florist shops like John Breitmeyer’s by 1890, or purchase seed from merchants to raise their own. Many reasons motivated them, from satisfying a sweetheart to keeping up with their neighbors’ ornamental plantings. No doubt, beautiful trade cards helped stir up allure and demand for popular garden flowers such as pansies.

Trade Card for Pansies Seeds, D. M. Ferry & Co., 1889 / THF298777

The entrepreneurs and florists of the 19th century sowed the seeds for an industry that remains vigorous but is far more globalized. There are botanic stories still to uncover and after centuries of cultivation, these beautiful ornaments still sustain something deeper within us.

Secondary Sources:

Stewart, Amy. Flower Confidential: The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful. Algonquin Books, 2008.

Lyon-Jenness, C. (2004). Planting a Seed: The Nineteenth-Century Horticultural Boom in America. Business History Review, 78(3), 381-421. doi:10.2307/25096907

Ayana Curran-Howes is 2021 Simmons Intern at The Henry Ford. Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

entrepreneurship, home life, shopping, farms and farming, agriculture, by Debra A. Reid, by Ayana Curran Howes, Michigan, Detroit, Detroit Central Market, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

| “The fact that Webster dwelt and worked on his dictionary there gives this structure singular historic interest…. That all this must disappear shortly before the crowbars of the wreckers is a matter of genuine regret…” —J. Frederick Kelly, New Haven resident and architect, quoted in New Haven Register, July 20, 1936 |

Article from the New Haven Register, New Haven, Connecticut, July 20, 1936. / THF624813

In the mid-1930s, Yale University, owner of the Noah Webster Home on Temple Street in New Haven, Connecticut, decided this former home of one of its notable alumni needed to be torn down. It was the Depression, and Yale’s financial situation required some retrenchment. Tearing down the Webster house, along with eleven other Yale-owned homes, would cut the university’s tax bill and save the expense of maintenance, while providing space for new construction better suited to the university’s needs.

The house came very near to being demolished.

In this comfortable home, completed in 1823 at Temple and Grove streets, Noah Webster had enjoyed an active family life, written many of his publications, and completed his ultimate life’s work—America’s first dictionary. Noah and Rebecca Webster had moved to New Haven in their later years to be near family and friends, as well as the library at nearby Yale College. While living in this house, Webster published his famous American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828.

Silhouette of Noah and Rebecca Webster by Samuel Metford, 1842. / THF119764

What happened to the house after the deaths of Noah in 1843 and Rebecca in 1847? For the next seven decades, the Temple Street house was filled with new generations of Webster descendants and their relations.

The Trowbridge Era

After Noah Webster’s death in 1843, the house became part of Webster’s estate. In his will, his wife Rebecca received the lifetime use of the Temple Street house. In March 1849, executors of the Webster estate, William Ellsworth (a son-in-law) and Henry White, deeded the property to Henry Trowbridge, Jr., a merchant who sold goods imported from the Far East and a director of the New Haven Bank. (Trowbridge took out a mortgage on the house in 1850, probably to compensate the estate for the value of the house.) Trowbridge had married Webster granddaughter Mary Southgate in 1838. Mary had been raised by Noah and Rebecca Webster and had grown up in the Temple Street house. Henry and Mary Trowbridge had six children: five daughters as well as a son who died young. Mary Southgate Trowbridge passed away in May 1860 of tuberculosis at the age of 41.

In 1861, Henry Trowbridge married again, to Sarah Coles Hull. Their son Courtlandt, born in 1870, was the only surviving child of the marriage.

About 1870, prosperous Henry Trowbridge decided to remodel the house, adding a wealth of “updates” in the then-fashionable Victorian style. These included five bay windows, as well as marble fireplace mantles, plaster ceiling medallions, exterior and interior doors, and elaborately carved walnut woodwork on the first floor. Trowbridge also lengthened the first-floor windows and built a brick addition on the back.

Noah Webster Home showing Victorian-era changes, including the bay windows and addition at the rear of the home. Top photo taken about 1927; bottom photo, in 1936. / THF236369, THF236375

Over the years, the house was filled with the rhythms of everyday life and the comings and goings of family. Nine Trowbridge children grew up there—six of them were born in the house and three of them died there. Daughters married and moved out. One Trowbridge daughter made two long-distance visits home during the years she and her merchant husband lived in Hong Kong. Another returned home for a time as a widow with a young child. In the 1910s, during the final years of Trowbridge ownership, the widowed Sarah lived in the house with her son Courtlandt, his wife Cornelia, and their three children.

Webster Home—perhaps a bit overgrown—about 1912. / THF236373

In 1918, the year following his mother’s death, 68-year-old Courtlandt Trowbridge sold the Temple Street house in which he had lived since birth “for the consideration of one dollar,” deeding the property to the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, located a block from the Webster house on Grove Street. Courtlandt, a Sheffield graduate, then moved to Washington, a rural village in northwest Connecticut, along with his wife, Sarah, and youngest son, Robert.

From Family Home to College Dorm

Postcard, Sheffield Scientific School, Yale College, 1915-1920. / THF624831

Sheffield Scientific School offered courses in science and engineering. Following World War I, its curriculum gradually became completely integrated with Yale University’s—undergraduate courses were taught at Sheffield from 1919 to 1945, coexisting with Yale’s science programs. (Sheffield would cease to function as a separate entity in 1956.) The Sheffield Scientific School used the Webster house as a men’s dormitory for freshmen for almost 20 years.

Postcard, Vanderbilt-Sheffield dormitories on Chapel Street in New Haven, about 1909. / THF624833

The Webster house wasn’t Sheffield’s only dormitory, though. The impressive Vanderbilt-Sheffield dorms, dating from the early 1900s, served most of Sheffield’s students. The Noah Webster Home provided some additional space for freshmen to live.

A view of Temple street about 1927, during the time Yale University used the Webster house (shown at far right) as a dormitory. / THF236367

In 1936, Yale decided that retaining the “non-revenue-bearing” house was not financially viable for the university. It was no longer needed as a dorm because of the construction of Yale’s Dwight College, opened in September 1935. Removing the Webster home would also provide space for growth for the university. (The site would become part of Yale’s Silliman College.)

A Timely Rescue

In early July 1936, Yale University was granted permission to demolish the house. (The louvered, elliptical window was to go to the Yale Art School.) The house was sold to Charles Merberg and Sons, a wrecking company. But there were attempts to save the home. Soon after Yale University was granted a permit on July 3 to tear down the house, the local newspaper, the New Haven Register, began a campaign to save it. New Haven resident Arnold Dana, a retired journalist, offered to contribute to a fund to preserve the house, but no additional offers of funds came. For several weeks, articles appeared in newspapers in New York and other large cities on the subject.

Initial interest in preserving the building by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA, now Historic New England) waned because of the Victorian-era changes. William Sumner Appleton, the society’s founder and a chief force behind the preservation of many historic buildings in New England, thought the building might make an interesting museum if a private individual would take on the project. Appleton said that SPNEA had no funds to do so.

J. Frederick Kelly, a New Haven resident, architect, and author of books on early Connecticut architecture, noted the building’s historical significance and commented on its architecture: “…the fine proportion and delicate scale of the Temple Street façade mark it as one of unusual distinction. The design of the gable … contains a very handsome elliptical louvre … an outstanding feature that has no counterpart in the East so far as I am aware.”

Telegram to Edsel Ford concerning the imminent demolition of the Noah Webster Home in New Haven, Connecticut. / THF624805

On July 29, R.T. Haines Halsey sent a telegram to Edsel Ford. Halsey let Edsel know that the Webster house was “in the hands of wreckers” and that it would fit in well with “your father’s scheme” for Greenfield Village. Immediate action was needed to save the house.

1924 postcard, American wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, built to display American decorative arts from the 1600s to the early 1800s. / THF148348

Halsey, a retired New York City stockbroker, was a collector of decorative arts who was instrumental in the opening of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City in 1924. In the 1930s, Halsey had become a research assistant in the Stirling Library at Yale University. Halsey may have chosen to contact Henry through Edsel because of Edsel’s interest in art and involvement with the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

On July 27, Ralph J. Sennott, manager of the Wayside Inn in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, a historic inn restored by Henry Ford, sent Ford a letter. (Perhaps it reached Ford about the time that Halsey’s telegram did.) Sennott also made Ford aware that the Webster home was in the hands of the wrecking company and that the building needed to be removed by September 1. The wrecker was willing to sell the house, but demolition work was to begin August 3. Henry Ford paid a $100 deposit on the house on August 2 to prevent demolition going forward. Ford was given until September 15 to make his final decision on acquiring the building.

Henry Ford arrived in New Haven on September 10 to see the Webster home in person. According to Lewis Merberg of the wrecking company, Ford appreciated the building for its historical significance more than for its “antiquity.” Noah Webster likely would have appealed to Ford as the author of the popular “Blue-Backed Speller,” used by many early American schools. Ford completed the purchase, paying about $1000 for the home.

Letter from Harold Davis of the Historic American Buildings Survey to Henry Ford, September 14, 1936. / THF624811

Noting Ford’s interest in the building, Harold Davis, the Connecticut district officer of the Historic America Building Survey, made Ford aware that the organization—whose purpose it was to measure and record historic buildings—had documented the Webster house in 1934. Ford acquired copies of these drawings, which were available at the Library of Congress.

The Noah Webster Home Moves to Dearborn

When Edward Cutler, the man responsible for moving and reassembling buildings in Greenfield Village for Henry Ford, arrived in New Haven in mid-September, wreckers had already removed windows and other parts of the house. The interior was not in the best state of repair—likely a little worse for wear after almost 20 years serving as home to college freshmen. Additional documentation of the house was needed before a wrecking crew disassembled the building under Edward Cutler’s direction. Cutler took more measurements. More photos of the home’s exterior and interior would assist with its reassembly in Greenfield Village.

Edward J. Cutler made detailed drawings of the house before it was dismantled. / THF132776

Image of the back of the Webster home taken in 1936 by a local New Haven photographer, perhaps at the request of Henry Ford or one of his representatives. / THF236377

Interior of house, view from the dining room looking towards the bay window in the sitting room. / THF236381

Edsel’s son Henry Ford II, then a Yale freshman, posed in front of the Noah Webster Home during its dismantling in October 1936. / THF624803

With this move, the Noah Webster Home would shed some of its Victorian-era “modernizing.” Cutler removed the four second-floor bay windows added during the Trowbridge renovation. He did retain some Trowbridge updates—exterior and interior doors, interior architectural details, and the first-floor bay window.

In October 1936, the Webster house was dismantled and packed up in about two weeks, according to Ed Cutler. Then it was shipped to Dearborn.

Webster Home reassembled in Greenfield Village, September 1938. / THF132717

Reassembly in Greenfield Village took about a year. In June 1937, workmen broke ground for the foundation of the home. By the end of December, most of the exterior work had been completed. Progress on the interior continued through the winter months. By July 1938, finishing touches were being added to the house.

Edison Institute High School girls prepare a meal in the Webster kitchen, 1942. THF118924

Until 1946, high school girls from the Edison Institute Schools used the Noah Webster Home as a live-in home economics laboratory—a modern kitchen was provided in the brick addition built on the back of the home. Henry Ford had opened the school on the campus of his museum and village in 1929.

Webster dining room in 1963. / THF147776

The Noah Webster Home finally opened to the public for the first time in 1962, telling the story of Webster and America’s first dictionary. Yet the Webster house was furnished to showcase fine furnishings in period room-like settings, rather than reflecting a household whose elderly inhabitants started housekeeping decades before.

Noah Webster Home Today

Noah Webster Home in Greenfield Village. / THF1882

In 1989, after much research on the house and the Webster family, museum staff made the decision to return the entire home to its original appearance during the Websters’ lifetime. The remaining Victorian additions were removed, including the first-floor bay window, interior woodwork, and interior doorways added during the Trowbridge era.

Noah Webster Home sitting room after 1989 reinstallation. / THF186509

Webster family correspondence and other documents painted a picture of a household that included not only family activities, but more public ones as well. Based on this research, curators created a new furnishings plan for the reinstallation. Now visitors could imagine the Websters living there.

Pay the Websters a Visit

Whew—close call. In 1936, the Noah Webster Home was saved in the nick of time.

Now that you know “the rest of the story,” stop by the Webster Home in Greenfield Village. Enjoy this immersive look into the past and its power to inspire us today. Hear the story of the Websters’ lives in this home during the 1830s, learn about Noah’s work on America’s first dictionary and other publications, and experience the furnished rooms that give the impression that the Websters still live there today.

For more on the Noah Webster Home, see “The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner.”

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Noah Webster Home, Henry Ford, home life, by Jeanine Head Miller, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

Meet Calvin Wood, Caterer of Eagle Tavern

“Calvin Wood, Caterer” sign outside Eagle Tavern. / THF237357

Outside Greenfield Village’s Eagle Tavern, an early 1830s building originally from Clinton, Michigan, is a sign that reads: “Calvin Wood, Caterer.” Yes, Calvin Wood was a real guy—and the tavernkeeper at Eagle Tavern in 1850. The Eagle Tavern building was just a few years old when Calvin Wood and his young family arrived in nearby Tecumseh Township about 1834. Little could Calvin guess that life’s twists and turns would mean that one day he would be the tavernkeeper there!

William H. Ladd’s Eating House, Boston, about 1840. Image courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Why caterer? In the 19th century, a “caterer” meant someone who not only provided food and drink, but who also catered in any way to the requirements of others. Some tavernkeepers, like Calvin Wood, referred to themselves as “caterers.” As Eagle Tavern’s tavernkeeper a few years hence, Calvin Wood would offer a bed for the night to travelers, a place to get a meal or a drink, a place to socialize and learn the latest news, and a ballroom upstairs to hold dances and other community events.

Moving to Michigan

1857 map of portion of Tecumseh Township, inset from “Map of Lenawee County, Michigan” (Philadelphia: Bechler & Wenig & Co., 1857), highlighted to show Calvin Wood’s farm located southeast of the village of Clinton. Map image from Library of Congress.

In the mid-1830s, Calvin and his wife Jerusha sold their land in Onondaga, New York, and settled on a farm with their children in Lenawee County, Michigan—a few miles south of the village of Clinton and a few miles north of the village of Tecumseh. (Calvin and Jerusha’s children probably numbered four—all but one would die in infancy or childhood.) The Wood family had plenty of company in this journey. From 1830 to 1837, Michigan was the most popular destination for westward-moving settlers caught up in the highly contagious “Michigan Fever.” During this time, the Michigan Territory’s population grew five-fold!

The move to Michigan offered promise, but the years ahead also held misfortune. In the early 1840s Calvin lost Jerusha, and some of their children likely passed away during this time as well. By 1843, Calvin had married for a second time, this time to Clinton resident Harriet Frost Barnum.

Harriet had left New York State with her parents and siblings and settled in Monroe County by 1830. The following year, 19-year-old Harriet married John Wesley Barnum. The Barnums moved to Clinton, where they were operating a “log hotel” along the Chicago Road in the fall of 1835. In October 1836, Wesley Barnum died, leaving Harriet a young widow with two daughters: Irene, age two, and Frances, age four. After their marriage, Calvin and Harriet’s blended household included not only Harriet’s two daughters, but also Calvin’s son. (There may also have been other Wood children in the home as well, though they might have passed away before this time.)

Calvin Wood, Tavernkeeper

In the early and mid-19th century, tavernkeeping was a small and competitive business. It didn’t require much experience or capital, and as a result, most taverns changed hands often. In 1849, farmer Calvin Wood decided to try his hand at tavernkeeping, an occupation he would engage in for five years. Many other tavernkeepers were farmers as well—like other farmer-tavernkeepers, Calvin Wood probably supplied much of the food for tavern customers from his farm. Calvin Wood didn’t run the tavern alone—a tavernkeeper’s family was often deeply involved in business operations as well. And, of course, Calvin’s wife Harriet was the one with previous experience running a tavern! Harriet would have supervised food preparation and the housekeeping. Frances and Irene likely helped their mother and stepfather in the tavern at times. Calvin’s son, Charles, was married and operating his own Tecumseh Township farm by this time.

Residence of F.S. Snow, & D. Keyes, Clinton, Michigan,” detail from Combination Atlas Map of Lenawee County, Michigan, 1874. / THF108376

By the time that Calvin and Harriet Wood were operating the Eagle Tavern, from 1849 to 1854, the first stage of frontier life had passed in southern Michigan. Frame and brick buildings had replaced many of the log structures often constructed by the early settlers twenty-some years before. The countryside had been mostly cleared and was now populated by established farms.

Mail coaches changing horses at a New England tavern, 1855. / THF120729

Detail from Michigan Southern & E. & K. RR notice, April 1850. / THF108378, not from the collections of The Henry Ford

Yet Clinton, whose early growth had been fueled by its advantageous position on the main stagecoach route between Detroit and Chicago, found itself bypassed by railroad lines to the north and south. The Chicago Road ran right in front of the Eagle Tavern, but it was no longer the well-traveled route it had once been. Yet stagecoaches still came through the village, transporting mail and providing transportation links to cities on the Michigan Central and Michigan Southern railroad lines.

Map of Clinton, Michigan, inset from “Map of Lenawee County, Michigan” (Philadelphia: Bechler & Wenig & Co., 1857). Map image from Library of Congress.

Though Clinton remained a small village, it was an important economic and social link—its businesses and stores still served the basic needs of the local community. During the years that Calvin operated the Eagle Tavern, Clinton businesses included a flour mill, a tannery, a plow factory, a wagon maker, wheelwrights, millwrights, coopers who made barrels, cabinetmakers who made furniture, chair manufacturers, and a boot and shoe maker. Clinton had a blacksmith shop and a livery stable. The village also had carpenters, painters, and masons. Tailors and seamstresses made clothing. A milliner crafted ladies’ hats. Merchants offered the locals the opportunity to purchase goods produced in other parts of the country, and even the world: groceries (like salt, sugar, coffee, and tea), cloth, notions, medicines, hardware, tools, crockery, and boots and shoes. A barber provided haircuts and shaves. Three doctors provided medical care. In 1850, like Calvin and Harriet Wood, most of Clinton’s inhabitants had Yankee roots—they had been born in New York or New England. But there were also a number of foreign-born people from Ireland, Scotland, England, or Germany. At least two African American families also made Clinton their home.

Many of Calvin’s customers were probably people who lived in the village. Others lived on farms in the surrounding countryside. Calvin’s customers would have included some travelers—in 1850, people still passed through Clinton on the stagecoach, in their own wagons or buggies, or on horseback.

Advertisements for Eagle Hotel, Clinton, and The Old Clinton Eagle, Tecumseh Herald, 1850. / THF147859, detail

Though Clinton was a small village, Calvin Wood faced competition for customers—the Eagle Tavern was not the only tavern in Clinton. Along on the Chicago Road also stood the Eagle Hotel, operated by 27-year-old Hiram Nimocks and his wife Melinda. It appears that the Eagle Hotel accommodated boarders as well—seven men are listed as living there, including two of the town’s merchants. These men probably rented bedrooms (likely shared with others) and ate at a common table.

Moving On

In 1854, Calvin Wood decided that it was time for his five-year tavernkeeping “career” to draw to a close. He and Harriet no longer operated the Eagle Tavern, selling it to the next tavernkeeper. Initially, the Woods didn’t go far. In 1860, Calvin is listed in the United States census as living in Clinton as a retired farmer. Yet Calvin and Harriet Wood soon moved to Hastings, Minnesota, where Harriet’s daughters, now married, resided. There Calvin and Harriet would end their lives, Calvin dying in 1863 and Harriet the following year.

The Wood family tombstone in Brookside Cemetery. / THF148371

You can still pay Calvin a “visit” at Brookside Cemetery in Tecumseh, where he shares a tombstone with his first wife, children, his father, and his brother’s family. For Harriet? You’ll have to make a trip to Hastings, Minnesota.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources, and Lisa Korzetz, Registrar, for assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Eagle Tavern Happy Hour: Mint Julep Recipe

- Eagle Tavern Happy Hour: Maple Bourbon Sour Recipe

- Making Eagle Tavern's Butternut Squash Soup

- Eagle Tavern at its Original Site, Clinton, Michigan, February 2, 1925

1850s, 1840s, 19th century, restaurants, Michigan, hotels, home life, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, food, Eagle Tavern, by Jeanine Head Miller, beverages

George Nelson’s Visionary Design

Product Tag for an Original George Nelson Design Executed by Herman Miller, 1955 / THF298217

George Nelson is one of the giants of American Modern design. Often with such individuals, it is usually sufficient to point to their output—the architecture, products, graphics they designed—as a way to simplify and quantify their impact. While George Nelson’s output was undeniably significant, an accounting of his legacy in this way will always fall short. Nelson’s contributions to Modernism and the field of design are akin to his office’s famous Marshmallow Sofa—a study in how parts relate to the whole.

Born in 1908 to an affluent family in Connecticut, George Nelson was encouraged to cultivate his intellect from a young age. He attended Yale University—more so for its proximity to home and prestige in the eyes of his parents than due to his own desire—and quite literally happened upon the study of architecture by chance. He recalled ducking into the architecture building on Yale’s campus to avoid a sudden rainfall. Student renderings of cemetery gateways hung in the halls. Nelson “fell in love instantly with the whole business of creating designs for cemetery gateways” and decided, “without further question,” to become an architect. He graduated with his B.A. in 1928 and a B.F.A. in 1931.

Marshmallow Love Seat, 1956-1965 / THF134573

Writing on Design

Nelson graduated with his new degree as the Great Depression tightened its grip on the United States. He was offered a teaching job at Yale, but was soon let go. He later considered this lucky, saying “…if you’re lucky, you are not allowed to stay safe. You’re thrown into jeopardy.” After a period of uncertainty in which he threw himself into applications for architectural fellowships in Europe, he was successful in winning the prestigious Rome Prize. This came with an all expenses paid, two-year architectural fellowship in Rome, which he took from 1932–1934. Those years in Rome allowed Nelson to travel throughout Europe, study great architecture, and become acquainted with many of the leading figures in the budding Modernism movement.

Architectural criticism and theory writing became a continuous outlet for Nelson throughout his career, beginning in the early 1930s when he first published drawings and articles in Pencil Points and Architecture magazines. Upon his return to the United States, he took a position with The Architectural Forum in New York City and worked his way up to co-managing editor. Nelson’s career path didn’t continue in a linear fashion, but sprouted offshoots. Soon, he simultaneously continued his journalistic pursuits (and expanded to other publications), designed architectural commissions, and created exhibitions. The work was never about the output, but about the process and the solving of problems in whichever way a circumstance demanded.

LIFE magazine for January 22, 1945 / THF623999

The Storage Wall

While writing a book on the house of the future titled Tomorrow’s House with Architectural Forum colleague Henry Wright, Nelson confronted the problem of household storage inadequacies, among other domestic matters. He explained his method in writing the book, “you will not find a chapter on bedrooms … but a great deal about sleeping.” His storage solution was a masterful rethinking of furniture and architecture in one. He recalled his “aha” moment: “My goodness, if you took those walls and pumped more air into them and they got thicker and thicker until maybe they were 12 inches thick, you would have hundreds and hundreds of running feet of storage.” Nelson’s innovative “storage wall” opened new doors for the furniture industry for years to come. His idea was featured in Architectural Forum in 1944 and then in a generous 1945 spread in Life magazine. It also attracted the attention of D.J. De Pree, the founder of the Herman Miller Furniture Company in Zeeland, Michigan.

LIFE Magazine for January 22, 1945 / THF623998

A Market for Good Design

After the untimely death of Gilbert Rohde, D.J. De Pree began to look for a new director of design. Rohde had successfully set the Herman Miller Furniture Company on the path of Modernism and De Pree was looking to continue that trajectory. Initially, De Pree considered German architect Erich Mendelsohn or industrial designer Russel Wright for the post, but eventually chose George Nelson, sensing a kindred spirit in a perhaps unlikely partnership. De Pree was devoutly religious and a teetotaler; Nelson, always accompanied by the lingering smell of cigarette smoke, questioned everything—especially religion—and loved martinis. Despite these differences, De Pree thought, rightfully, that Nelson was “thinking well ahead of the parade,” and hired him for the job. Like De Pree and Rohde, Nelson was completely invested in continuing Herman Miller’s focus on honesty and quality in Modern design. In the forward to a groundbreaking 1948 catalogue, Nelson outlined the company philosophy:

The attitude that governs Herman Miller’s behavior, as far as I can make out, is compounded of the following set of principles:

What you make is important….

Design is an integral part of the business….

The product must be honest….

You decide what you will make….

There is a market for good design.

Advertisement for Herman Miller Furniture Company, "George Nelson Designs," October 1947 / THF623977

Herman Miller and George Nelson’s decades-long collaboration was fruitful almost immediately. Nelson rethought some of Gilbert Rohde’s furniture and issued lines of his own furniture design. He had proven himself a prescient thought leader in the design world through his writing, but became adept at finding talented people and bringing them together for the greater good of design. D.J. De Pree admitted surprise when Nelson requested to bring on other designers—even before his own contract was formalized. Instead of hoarding the glory (and potential income) for himself, Nelson saw the far-reaching benefits of collaboration with other visionary designers. It was Nelson who brought together the core design team that still shapes Herman Miller’s design today—most notably, Charles and Ray Eames, Isamu Noguchi, and Alexander Girard.

A tendency towards collaboration was not isolated to Nelson’s work at Herman Miller. In his personal life, he counted architect Minoru Yamasaki and architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller among his close friends. And those that he employed in his eponymous design office (which had many clients, although Herman Miller was certainly the largest account for many years) were the best of the best too. These staff designers—Irving Harper, Tomoko Miho, Lance Wyman, and Don Ervin, to name just a few—maintained the constant hum of the office. They diligently continued to ideate, design, and make for the office’s clients. Sometimes they executed their own concepts, and other times the staff designers brought their metaphorical and literal pens to paper for some of Nelson’s lofty visions.

Nelson has faced fair criticism of taking more credit than was due for some of the designs that came from his office. He positioned himself as a powerful brand—and many of those who worked under him gained valuable experience, but perhaps never the full realization of their efforts in the public sphere.

Trade Card for Herman Miller, “Come and See the New Designs at the Herman Miller Showroom,” circa 1955 / THF215327

George Nelson actively designed for Herman Miller until the early 1970s and continued designing products, exhibits, interiors, graphics, and more with his own firm until 1984. He lectured and wrote on design theory and practice until his death in 1986, influencing and inspiring generations of designers. George Nelson’s contributions to design are much greater than his output—the products, writings, structures, and graphics he produced. He may have been more concerned with principles and processes than about the tangible result—but his loftier focus is what made his tangible designs so effective. Nelson’s ideas and ideals shaped the Modernist design movement and his influence can still be felt, reverberating through the halls of design offices and school halls alike.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

20th century, Michigan, New York, home life, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White

Memorial Paintings for Memorial Day

Americans always treasured the memory of the dearly departed, but during the era just after American independence, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, elaborate and artistic memorials were the norm. Scholars debate the reasons. Many believe that with the death of America’s most revered founding father, George Washington, in 1799, a fashion developed for creating and displaying memorial pictures in the home. Other scholars argue that the death of Washington coincided with the height of the Neoclassical, or Federal style in America. During the period after the Revolution, Americans saw themselves as latter-day Greeks and Romans. After all, they argued, the United States was the first democracy since ancient times. So, they used depictions of leaders like George Washington, along with imagery derived from antiquity.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for George Washington, by Mehetabel Wingate, 1800-1810 / THF6971

This wonderful memorial painting of George Washington was drawn in pencil and ink and painted in watercolors by a woman in Haverhill, Massachusetts, named Mehetabel Wingate. Born in 1772, Mehetabel was likely trained in painting as part of her education at an academy for genteel young ladies, much like a “finishing school” for young ladies in the 20th century. She also would have been tutored in the needle arts. The concept was to teach proper young ladies the arts as part of an appreciation for the “finer things” in life. This would prepare them for a suitable marriage and help them take their place in refined society.

In the academies, young women were taught to copy from artistic models for their work. In this case, Mehetabel Wingate copied a print engraved by Enoch G. Grindley titled in Latin “Pater Patrae” (“Father of the Country”) and printed in 1800, just after Washington’s death in 1799. Undoubtedly, she saw the print and was skilled enough to copy it in color. The image of the soldier weeping in front of the massive monument to Washington is impressive. Also impressive are the angels or cherubs holding garlands, and women dressed up as classical goddesses, grieving. One of the goddesses holds a portrait of Washington. Of course, the inscriptions tout many of Washington’s accomplishments. Mehetabel Wingate was a talented artist and ambitious in undertaking a composition as complicated as this one.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for Mehetabel Bradley Wingate, by her daughter Mehetabel Wingate, 1796 / THF237513

Fortunately, The Henry Ford owns two additional works made by Mehetabel Wingate (1772–1846). From these, we can learn a bit about her life and her family. This remarkably preserved watercolor painting memorializes her mother, also named Mehetabel, who died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1796. Young Mehetabel, who would have been 24 in 1796, is shown mourning in front of a grave marker, which is inscribed. Although it is simplified, she wears a fashionable dress in the most current style. Around her is an idealized landscape, which includes a willow tree, or “weeping” willow, on the left, which symbolized sadness. On the right is a pine tree, which symbolized everlasting life. In the background is a group of buildings, perhaps symbolizing the town, including the church, which represented faith and hope. These are standard images seen in many, if not most, American memorial pictures. Mehetabel Wingate undoubtedly learned these conventions in the young girls’ academy in her hometown of Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Women in Classical Dress, 1790-1810, by Mehetabel Wingate / THF152522

The painting, above, while not a memorial painting, shows us how young ladies in the academies learned how to paint. Mehetabel seems to be practicing poses and angles, as the young ladies dressed as classical goddesses reach out to each other. It likely pre-dates both works previously shown and may have been done as a classroom exercise. As such, it is a remarkable survival.

In memory of Freeman Bartlett Jr. who died in Calcutta November the 1st 1817, aged 19 years, by Eliza T. Reed, about 1818 / THF14816

This example, painted later than Mehetabel Wingate’s work, shows the same conventions: a grieving female in front of a tomb with an inscription about the dearly departed—in this case, a young man who died at the tender age of 19 in far-off Calcutta. We also see the idealized landscape with the “weeping” willow tree and the church in the background.

Memorial Painting for Elijah and Lucy White, unknown artist, circa 1826 / THF120259

The painting above, done a few years later, shows some of the variations possible in memorial pictures. Unlike the previous examples, painted on paper, this was painted on expensive, white silk. It commemorates two people, Elijah and Lucy White, presumably husband and wife, who both died in their sixties. We see the same imagery here as before, although the trees, other than the “weeping” willows, are so abstract as to be difficult to identify.

Memorial Painting for Sarah Burgat, J. Preble, 1826 / THF305542

The example above represents a regional approach to memorial paintings. German immigrants to Pennsylvania in the late 1700s and early 1800s brought an interesting, stylized approach to their memorial paintings that have come to be known as “Fraktur.” The urn that would be seen on top of the monument in the previous examples now takes center stage, and is surrounded by symmetrically arranged birds. What we are seeing here is a combination of New England imagery, such as the urn, with Pennsylvania German imagery, such as the stylized birds. We know that this work was made in a town called Paris, as the artist, J. Preble, signed it in front of her name. There are two possible locations for Paris—one in Stark County, Ohio, and the other in Kentucky. Both had sizeable German immigrant populations in the 1820s. As America was settled and people moved west in the early 19th century, cultural practices melded and merged.

By the 1840s and 1850s, the concept of the memorial painting came to be viewed as old-fashioned. The invention of photography revolutionized the way folks could save representations of loved ones and friends. By the middle of the 19th century, these paintings were viewed as relics from the past. But in the early 20th century, collectors like Henry Ford recognized the historic and artistic value of these works and began to collect them. As a uniquely American art, they provide insight into the values of Americans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, 19th century, 18th century, women's history, presidents, paintings, making, home life, holidays, education, by Charles Sable, art

"American Sports, Base Ball, Striker & Catcher" Plate, circa 1850 / THF135816

| "On Saturday afternoon, Sept. 10, at the farm of Louis Bradley, might have been seen a small gathering of people. They came to see the final game between the Lah-da-dahs, of Waterford, and the White Lakes of Webster neighborhood." –Pontiac Bill Poster, September 14, 1887 |

In the 1880s, many Michigan towns supported baseball teams, including Waterford, in Oakland County, but the game's history goes back further. The game of base ball (as it was often spelled into the 1890s) had its origins in a number of children's games, but especially a British game called "Rounders." Rounders rules called for the game to be played on a diamond, with a striker (batter) who faced a feeder (pitcher).

The American game of base ball gained in popularity in the mid-1800s, so much so that English ceramic makers produced dishes such as the "Base Ball" plate above, depicting a "Striker & Catcher," to appeal to American consumers. American interest in base ball in the late 1800s is evident in the production and marketing of such a plate.

Americans purchased these English-made ceramics to celebrate their national game, but base ball did not have all the regulations we know in modern baseball today. Until the 1880s, rules stated that the pitcher had to deliver the ball underhanded with a straight arm. The batter could call for a high or low pitch. A high pitch was considered one between the belt and shoulders, and a low pitch was to be delivered between the belt and knees, a range close to the modern strike zone. Balls and strikes were usually not called until the 1870s.

Some rules called for home plate to be made of marble or stone, but there was no batter's box, only a line that bisected the plate. Consequently, today's historic base ball umpires will frequently signal the start of a game by calling, "Striker to the line!" Early rules discouraged, and often forbade, players being paid.

You can browse artifacts related to both the early and more modern forms of baseball in our Digital Collections. Or, if you want to see vintage base ball firsthand, check out the schedule for the Greenfield Village Lah-De-Dahs, who borrowed the name of the old Waterford team. The Village nine suit up to play teams from Ohio and Michigan throughout the summer as a part of Historic Base Ball in Greenfield Village. Though the song "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" was not written until 1908, you might hear the band play it. If you wish, you can sing along and cheer on the base ball strikers for the Lah-De-Dahs.

This post was adapted from the July 2000 entry in our former Pic of the Month series.

Additional Readings: