THF Conversations: Autonomous Vehicles - Solving Problems & Driving Changes

In honor of National Engineers Week at The Henry Ford, our Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson led a panel (including Michigan Department of Transportation’s Michele R. Mueller, Kettering University’s Kip Darcy, and Arrow Electronics’ Grace Doepker) on the topic of autonomous vehicles. The panel wasn’t able to answer all of the questions asked, so we’ve collected our inquiries for the experts to weigh in on.

If you missed the panel, you can watch the presentation here.

Is the Comuta-Car a copy of The Dale?

Matt: The Dale is a story unto itself. That car (like the company behind it) was considered a fraud, while the Comuta-Car was a much more successful effort to manufacture and market vehicles. The Dale was a three-wheeled car powered by a two-cylinder internal-combustion engine. The Comuta-Car had four wheels and a DC electric motor. The Dale was also considerably larger, measuring 190 inches long to the Comuta-Car's 95 inches. That said, both cars were aimed at economy-minded customers looking for fuel efficiency.

Is there a danger to the vehicle being hacked?

Michele: There is a lot of work around security from all aspects (vehicle, infrastructure, supplier hardware, software, etc.) that put multiple layers of security in place to prevent that.

Kip: System security is a big deal - ensuring vehicle platforms are using the most sophisticated security is vital to building trust for owners and operators. Over-the-air updates is an important component to ensure the vehicle platform has the latest antivirus/security defenses. Like cell phones, the platform always needs to be secure.

What types of programs/coding is available to protect the confidentiality of the car to only be assigned to the driver?

Michele: The industry has developed and continues to develop things such as personal recognition items (facial features, fingerprint, eye scan, etc.) that would allow this type of driver confidentiality. It has also brought to light concern over law enforcement and emergency responder access if needed in cases of having to impound a vehicle, if the vehicle is in a crash etc. MDOT has worked very diligently with Michigan State Police specifically to meet with industry professionals and talk through these challenges from that perspective and has aided the industry in their development of the technology. MDOT also works with other entities to provide training opportunities to Emergency responders for how to handle these types of vehicles as well as electric vehicles as they become more common on the infrastructure.

Kip: Quite likely that users and owners will give up a fair amount of confidentiality w/technology providers/OEMS when using fully connected vehicles. Like web browsing and mobile phone usage, it will be used to personalize the experience. Flip side - multiple users of a vehicle would have user accounts/profiles like current smart key/fob profiles on vehicles. If someone uses your fob, they may have access to your profile and user data.

How do these cars account for winter driving in states like Michigan?

Michele: A lot of testing goes on with these vehicles in all weather conditions and many of the auto companies and Tier I suppliers have facilities in northern and Upper Peninsula of Michigan to do testing such as this in those conditions. They are run through many weather scenarios rigorously and this is a good use case for why we set up our pilot and deployments in this space as sustainable environments so that regardless of when the weather happens the environment is there to test with.

Kip: As Michele points out, Michigan is an amazing test environment: the combination of extreme weather and infrastructure challenges make for great testing to compliment all of the work done in California, Arizona, and Nevada.

How do you overcome the liability issue? If an individual is in a crash due to driver’s error, it’s their fault. If an individual is in a crash in an autonomous car, is the manufacture at fault?

Michele: This is a very hot topic with a lot of lawyers, legal teams, insurance entities, etc., all part of the conversation. That determination is not out yet and I believe we have a bit to go before it is resolved. I do know that the reduction of crashes is drastically reduced by taking the human error factor out which automatically leads to a reduction in injuries and fatalities.

Kip: I see the convergence of two issues; driver liability and product liability. Currently need a licensed driver in a vehicle - fault pinned to the driver (however, MI is no-fault) Malfunctioning systems would be a product liability issue - such as a possible design or manufacturing defect. In a future w/L4/L5 fully automated vehicles w/o a licensed driver, the insurance regulations will need to change. NAIC National Auto Insurance Commissioners has resources on the topic.

When do you think autonomous vehicles will become widely used in our everyday life?

Michele: I personally believe that a fully Level 5 automated vehicle being widely used with saturation is 15-20 years out. We have automated vehicles today with different feature sets and they are showing benefits. There will be a transition period and a mixed use for a quite a while yet.

Kip: Based on adoption studies done before the pandemic, I would concur: 2045 for 50% adoption rate for L4/L5. Important to remember the average fleet age in the US: 11- to 12-years old; a lot of old cars on the road.

You mentioned how highways impacted cities and Black communities. You could flip that question and ask about how autonomous vehicles will impact rural communities, especially in areas where cities are few and far between and infrastructure not as important. Is there an incentive to go automated in independent, rural America?

Michele: The speculation is that you will see some sort of incentivization at some point to adapt the technology in your vehicle whether new or after market. This may come as the technology and infrastructure are more advanced and refined for implementation, nobody knows for sure what that will look like however, it is very feasible. MDOT has done testing with industry partners in rural areas and to be honest there are some differences but not many, we currently do a lot of testing and deployments in the denser areas just due to the location of the industry partners doing development and testing, the closer they are to those platforms the more testing, tweaks, retesting that can be done for a lower cost. In the decision-making process for infrastructure standards and specifications we are looking at the entire State of Michigan for setting those and as upgrades and projects are done all areas are putting in the infrastructure to be ready for the technology as the needs and demand spreads.

Additional Resources: Please check out the following links to learn more.

Employment with the State of Michigan

State of Michigan Job Alerts

Application Process

Recruitment Bookmark

First-Time Applicants: How To

Working at MDOT

Internships at MDOT

MDOT: Planning for the Future

MDOT Transportation Technicians

MDOT Transportation Engineers

Engineer Development Program

| MDOT - Michigan Department of Transportation Michigan Department of Transportation – Michigan Department of Transportation is responsible for planning, designing, and operating streets, highways, bridges, transit systems, airports, railroads and ports. Find out more about lane closures, roads, construction, aeronautics, highways, road work and travel in Michigan. MDOT: 2021 Engineering Week Webpage |

| Arrow Electronics: Five Years Out |

| Kettering University: |

Capturing a Moment: How We Created a Display for Henry Ford’s “Sweepstakes”

In his first race ever, Henry Ford beat Alexander Winton in the Sweepstakes Race. / THF94819

On October 10, 1901, Henry Ford made history by overcoming the favored Alexander Winton in his first-ever automobile race. Backed by a willingness to take risks and an innovative engine design, Henry earned the reputation and financial backing through this one event to start Henry Ford Company, his second car-making venture.

His success that day is a natural introduction display for our newest permanent exhibition, Driven to Win: Racing in America, presented by General Motors. Driven to Win celebrates over 100 years of automotive racing achievements and the people behind the passion for going fast.

Photos of the 1901 race provide a view of the environment that written accounts don’t. / THF123903

In creating an exhibition, we start with many experience goals. In this case, one exhibition goal is to take our guests behind-the-scenes and trackside. As you experience Driven to Win, you’ll find many of the vehicles displayed on scenic surfaces and in front of murals that represent the places the cars raced. Henry Ford’s Sweepstakes Race took place on a horse racing track in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. Through reference photos and discussions with our exhibit fabrication partner, kubik maltbie, artisans created a surface that captures the loose dirt quality of a horse racing track. If you look closely, you’ll see hoof prints alongside tire tracks, which capture the unique location of this race.

kubik maltbie’s artists created a variety of samples to find the most accurate dirt display surface that’s also suitable for use in a museum setting.

Look closely and you can see evidence of horses having raced on the same track.

The next component in bringing this race to life needed to illustrate what the day was like. It also needed to convey the most exciting part—when Henry Ford overtook his competition. Working with a local artist, Glenn Barr, we created a background mural depicting Henry’s rival being left in the dust. To do this, we returned to available reference photos showing the track, grandstand, and Henry’s rival, Alexander Winton, who was the country’s most well-known racer at this time.

Sketches and small-scale paintings allowed Glenn Barr and the design team to discuss components of the mural before the final painting was created.

Glenn created a series of early sketches to make sure we had all the important elements. We then took those sketches and added them to our 3D model of the exhibition. This allowed us to pre-visualize the entire display from all angles, and verify we had the correct perspective in the mural. Color plays a big part in creating this scene with a certain mood. The goal was a color palette that felt like 100+ years ago, but also like we were watching the race. Glenn created a series of color samples that allowed us to find the right combinations.

Programs like Sketchup allow us to easily create exhibit spaces in three-dimensions so that we can study sightlines and relationships between exhibit elements.

While this photo was posed, likely to commemorate the race win, Henry Ford and Ed “Spider” Huff’s postures are confirmed from other photos, and this one provides clearer details. / THF116246

The last element in creating our day-of-the-race display was perhaps the most important—Henry Ford and his ride-along mechanic, Ed “Spider” Huff, themselves. Again, reference photos are vital tools in seeing the past. In creating these mannequins we had three key elements to address: Henry and Spider’s likenesses, the clothing they wore, and the postures they’d have sitting in the vehicle. kubik maltbie’s artists were able to capture this moment. They started with clay sculptures of Henry and Spider’s faces.

Henry Ford and Ed “Spider” Huff’s likenesses were captured in life-sized clay sculptures that would later be used to create molds for the finished mannequins.

As these mannequins needed to sit directly in the vehicle, a museum artifact, much of the final sizing, positioning, and decisions on how they interfaced with the car was done away from the actual vehicle. kubik maltbie’s sculptor came to the museum for several days and built a wood frame system around the Sweepstakes. This accurately captured important dimensions and connection points. An exact replica of the steering wheel became a template that sculptors could use in their studio to finalize hand positioning.

If you’ve visited Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford, you’ll have seen that period clothing is one of our specialties. Every spring we distribute over 1,000 sets of handmade attire authentic to many different time periods. With insight from our curators, our Clothing Studio provided period-accurate clothing, from shoes to hats, for Henry and Spider.

Henry Ford and Ed “Spider” Huff arrive at the museum.

Museum conservators and the installation team place Ed “Spider” Huff, Henry’s ride-along mechanic, on the Sweepstakes’ running board.

Together, all these elements allow us to take you on a trip back in time. I invite you to visit the museum and see this monumental moment in racing history, stand trackside, and imagine what it must have been like. You can even hear our faithful replica of the “Sweepstakes” running. It sounds nothing like today’s track-ready racing machines.

Wing Fong is Experience Design Project Manager at The Henry Ford.

cars, making, art, design, race car drivers, race cars, collections care, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Wing Fong, racing, Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win

"The Better Angels of Our Nature": President Lincoln's First Inaugural Address

Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States / THF118582

March 4, 1861: Inauguration Day. Abraham Lincoln, the President-elect, takes the oath of office to become the 16th President of the United States. It was an uncertain time. The country was torn over the issue of slavery. For years, a tenuous arrangement had been maintained between free and slaveholding states, but now many Americans—on both sides—seemed unwilling to compromise. The Democratic Party had fractured over the issue. Two Democrats and a former Whig, each with differing views, vied to become president in 1860. This left the Republican Party, which wanted to limit slavery, with an opportunity for an electoral victory.

Lincoln, the Republican Party candidate, was elected by a minority of eligible voters, winning mainly Northern and Western states—enough for an electoral majority—but receiving little or no support from the slaveholding South. Since Lincoln's election in November 1860, seven Southern states had seceded from the Union, and many Americans feared the other eight slave states would follow. Americans anxiously waited to hear from their new president.

Campaign Button, 1860 / THF101182

In his inaugural address, Lincoln tried to allay the fears and apprehensions of those who perceived him as a radical and those who sought to break the bonds of the Union. More immediately, his address responded to the crisis at hand. Lincoln, a practiced circuit lawyer, laid out his case to dismantle the theory of secession. He believed that the Constitution provided clear options to change government through scheduled elections and amendments. Lincoln considered the more violent option of revolution as a right held by the people, but only if other means of change did not exist. Secession, Lincoln argued, was not a possibility granted by the founders of the nation or the Constitution. Logically, it would only lead to ever-smaller seceding groups. And governing sovereignty devolved from the Union—not the states, as secessionists argued. Finally, if the Constitution was a compact between sovereign states, then all parties would have to agree to unmake it. Clearly, President Lincoln did not.

Lincoln did not want conflict. His administration had yet to govern, and even so, he believed that as president he would have "little power for mischief," as he would be constrained by the checks and balances framed in the Constitution. Lincoln implored all his countrymen to stop and think before taking rash steps. But if conflict came, he would be bound by his presidential oath to “preserve, protect, and defend” the government.

Lincoln concluded his case with the most famous passages in the speech—a call to remember the bonds that unify the country, and his vision of hope:

"I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."

Lincoln's appeal, however, avoided the cause of the onrushing war—slavery. Failing to take this divisive issue head-on only added to its polarizing effect. Many Americans in the North found Lincoln's speech too conciliatory. Southerners thought it threatened war. And the nation had little time to stop and think. Immediately after his inauguration, Lincoln had to decide whether to resupply Fort Sumter, the U.S. military post in Charleston harbor, the heart of secession. In April, the "bonds of affection" broke.

Lincoln had hoped that time and thoughtful deliberation would resolve this issue—and in a way it did. The tragedies of war empowered Lincoln to reconsider his views. His views on slavery and freedom evolved. No longer bound, Lincoln moved toward emancipation, toward freeing enslaved Americans, and toward his "better angels."

Engraving, "The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet" / THF6763

To read Lincoln's First Inaugural Address, click here.

Andy Stupperich is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1860s, Washington DC, 19th century, presidents, Civil War, by Andy Stupperich, Abraham Lincoln

The Incredible Life of Frederick Douglass

The story of Frederick Douglass’s life is, at turns, tragic and awe-inspiring. He is a testament to the strength and ingenuity of the human spirit. The Henry Ford is fortunate to have some materials related to Douglass, as well as to the many areas of American history and culture he touched. What follows is an exploration of Frederick Douglass’s story through the lens of The Henry Ford’s collection, using our artifacts as touchpoints in Douglass’s life.

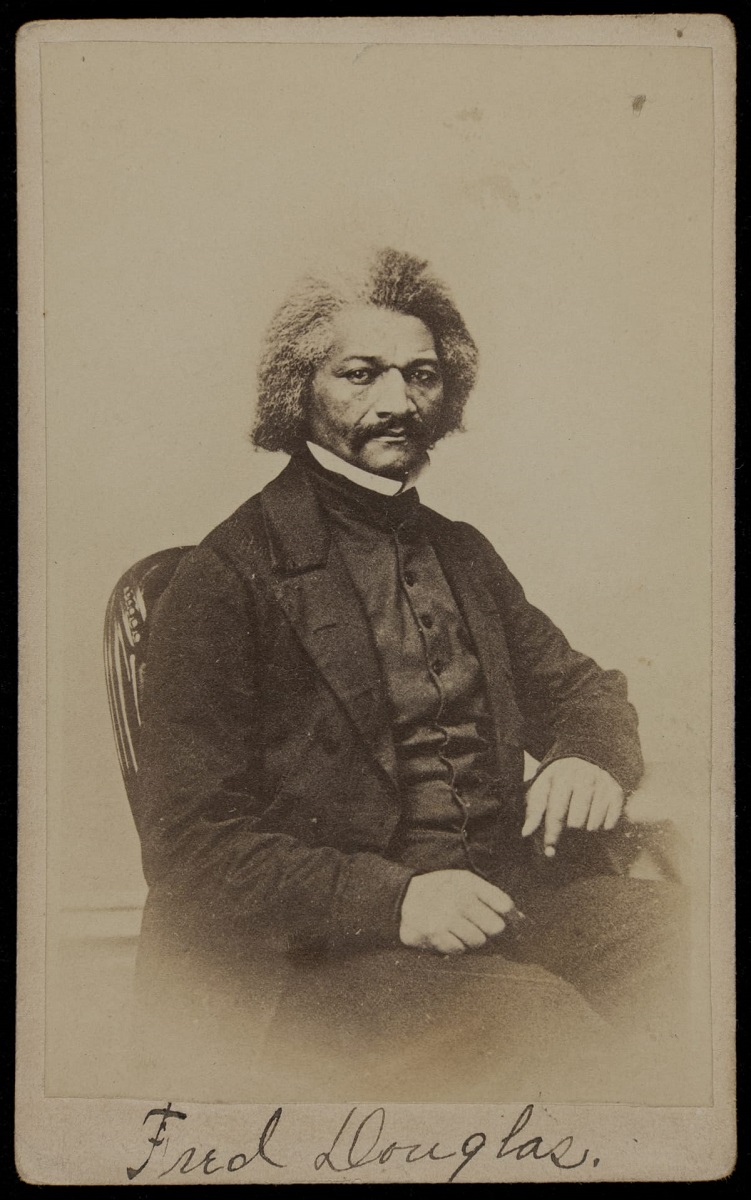

This portrait of Douglass was taken circa 1860, around the time Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States. / THF210623

Early Life & Escape

Born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, Frederick Douglass was named Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey by his enslaved mother, Harriet Bailey. Tragically, Douglass only saw his mother a few times before her early death, when Douglass was just seven years old. Though he had few memories of his mother, he recalled her fondly and was proud to learn that she also knew how to read. He wrote that he was “quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess” to his mother. Few enslaved people could read at that time—Douglass’s pride in his mother was certainly justified.

In 1826, Douglass was sent to Baltimore, Maryland, to live with the family of Hugh and Sophia Auld—extended family of his master, Aaron Anthony. This move to Baltimore would be transformative for Douglass. It not only exposed Douglass to the wider world, but was also where Douglass learned to read.

Douglass was initially taught to read by Sophia Auld, who considered him a bright pupil. However, the lessons were put to a stop by Hugh Auld. It was not only illegal to teach an enslaved person to read, but Hugh also believed literacy would “ruin” Douglass as a slave. In a sense, Douglass agreed, as he came to understand the vast power of literacy. Douglass would later remark that “education and slavery are incompatible with each other.”

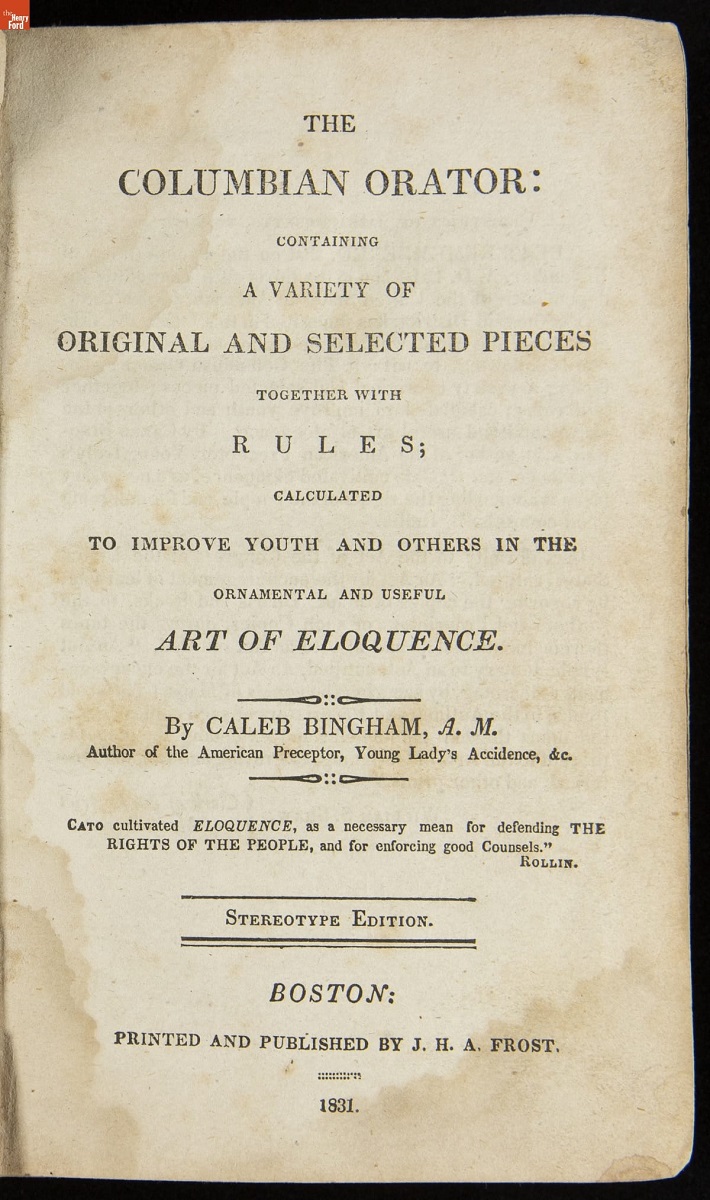

Douglass was determined to read. He “converted to teachers” some of the friendlier white children in the neighborhood. They showed him a school reader entitled The Columbian Orator, by Caleb Bingham, that he came to rely upon. In 1830, he purchased his own copy for 50 cents. The book—a collection of exceptional oration, poems, dialogue, and tips on the “art of eloquence”—became a great inspiration to Douglass. He carried it with him for many years to come.

“The Columbian Orator” features a discussion between an enslaved person and their master which impressed Douglass. The enslaved person’s dialogue—referred to as “smart” by Douglass—resulted in the man’s unexpected emancipation. / THF621972, THF621973

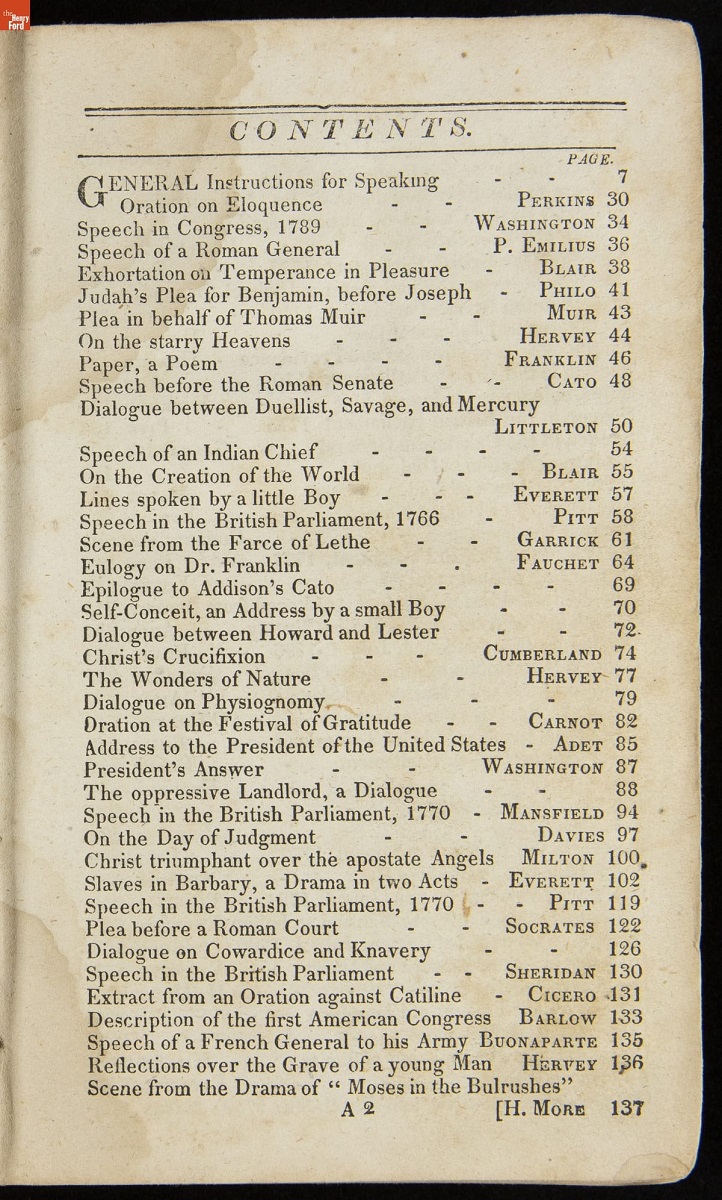

As recollected in his first memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, published in 1845, Douglass’s teenage years were some of his most challenging. He became viewed as a “troublemaker.” He was hired out to different farmers in the area, including one who had the reputation as an “effective slave breaker” and was especially cruel. Knowing that a larger world awaited and facing a terrible quality of life, Douglass attempted an escape in 1836. The escape failed and he was put in jail. Douglass was surprised to be released. He was sent not to the deep South as he had feared, but instead, back to Baltimore and the family of Hugh Auld, to learn the trade of caulking at the shipyards. While working there, Douglass was subjected to the animosities of his white coworkers, who beat him mercilessly—and were never arrested for it because a white witness would not testify and the word of a Black man was not admissible. He continuously dreamt of escape.

In this first memoir, Douglass provides great detail into his early life. However, because he was still a fugitive at the time of publication, he omitted details related to his escape. / THF8133

Recalling the ships on Chesapeake Bay, Douglass wrote:

“Those beautiful vessels, robed in purest white, so delightful to the eye of the freemen, were to me so many shrouded ghosts, to terrify and torment me with thoughts of my wretched condition. You are loosed from your moorings and are free; I am fast in my chains and am a slave! You move merrily before the gentle gale, and I sadly before the bloody whip!”

The ships’ freedom taunted him.

On September 3rd, 1838, Douglass courageously escaped slavery. Dressed as a sailor and using borrowed documents, he boarded a train, then a ferry, and yet another train to reach New York City—and freedom. His betrothed, Anna Murray Douglass, a free Black woman, followed, and soon after they were married. Frederick and Anna Murray Douglass moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, with hopes that Frederick could find work as a caulker in the whaling port. Instead, he took on a variety of jobs—but, finally, the money he earned was fully his. It is believed that Anna Murray Douglass played a crucial role in supporting Frederick's escape. Their shared commitment to freedom made them a formidable team in the fight against slavery.

The American Anti-Slavery Society & the Abolitionists

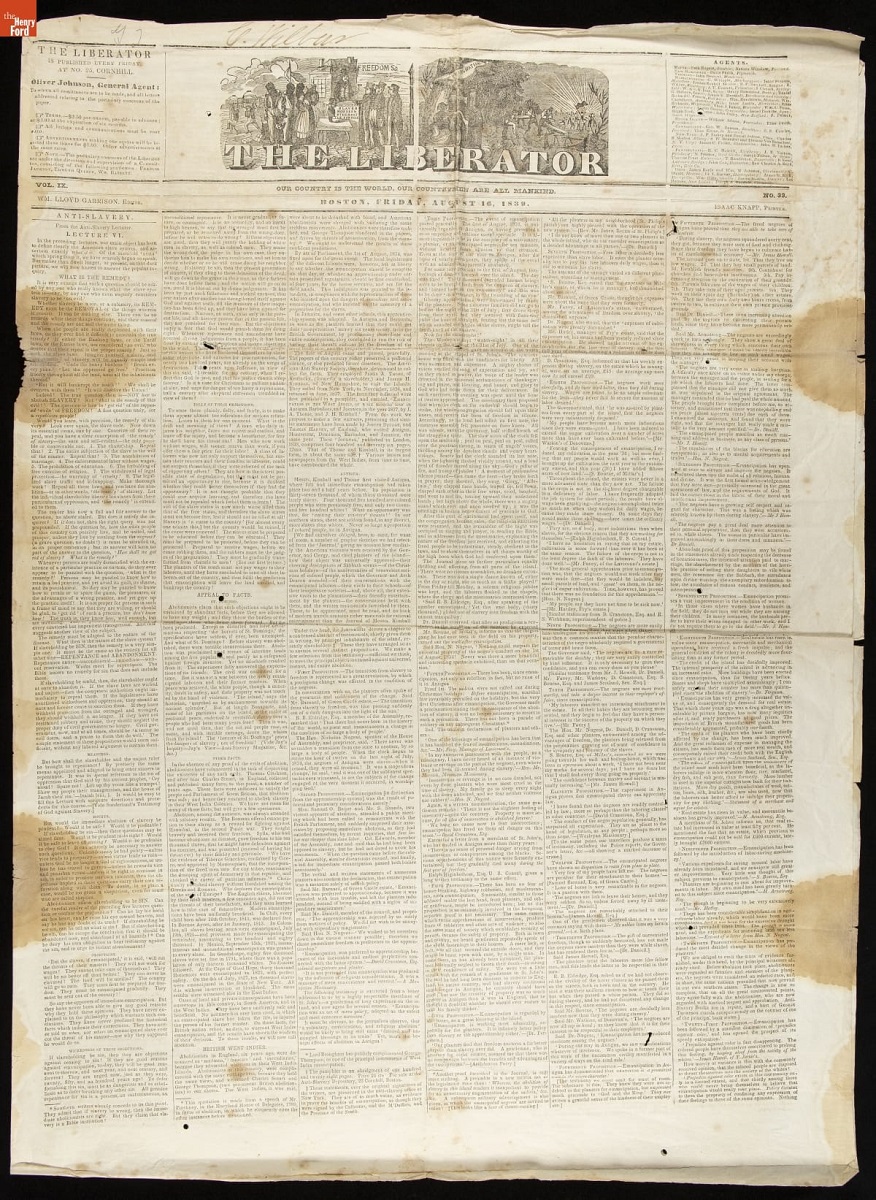

While living in New Bedford, Douglass encountered William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, for the first time. Douglass later wrote that the paper “took its place with me next to the Bible.” The Liberator introduced to Douglass the official abolitionist movement. This was a pivotal moment in his journey to becoming a prominent abolitionist leader.

In August of 1841, Douglass attended an abolitionist convention. In an impromptu speech, he regaled the audience with stories of his enslaved past. William Lloyd Garrison and other leading abolitionists noticed—Douglass’s career as an abolitionist orator had begun. Douglass became a frequent speaker at meetings of the American Anti-Slavery Society. His personal story of life enslaved humanized the abolitionist movement for many Northerners—and eventually, the world. His powerful speeches resonated deeply, inspiring many to join the cause.

In 1845, he published his first memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. By 1847, it had already sold more than 11,000 copies! This would be followed by two more memoirs: My Bondage and Freedom in 1855 and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in 1881. These narratives became essential texts in the abolitionist movement and the aftermath of the Civil War, providing firsthand accounts of the horrors of slavery.

This copy of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator was published on August 16, 1839—around the time when Douglass first encountered the paper. / THF621979

Women’s Suffrage

Douglass was also supportive of the women’s suffrage movement. He spoke at the famous Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 in support of women’s rights. In fact, the motto of his newspaper, The North Star, was “Right is of no sex—Truth is of no color—God is the Father of us all, and we are brethren.”

While Douglass forcefully supported women’s suffrage, some of his actions put him at odds with others in the movement. He supported the adoption of the 14th amendment, ratified in 1868, which guaranteed equality to all citizens—which included Black and white males, including the formerly enslaved. It did not include women. He also supported adoption of the 15th amendment, ratified in 1870, which secured Black males voting rights. Again, the amendment excluded women. Although a dedicated women’s rights activist, Douglass supported the adoption of the 14th and 15th amendments as he believed the matter to be “life or death” for Black people. This put him in disagreement with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, two of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement, as well as his friends. Despite this disagreement about timing, Douglass would continue to lecture in support of women’s equality and suffrage until his death.

John Brown’s Raid

Douglass was well-acquainted with famous abolitionist leader John Brown, first meeting him in 1847 or 1848. Brown became known for leading a raid on the armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, intending to create an “army of emancipation” to liberate enslaved people. Douglass and Brown spoke shortly before John Brown’s raid. Brown had hoped that Douglass would join him, but Douglass declined. He believed that Brown was “going into a perfect steel trap, and that once in he would not get out alive.”

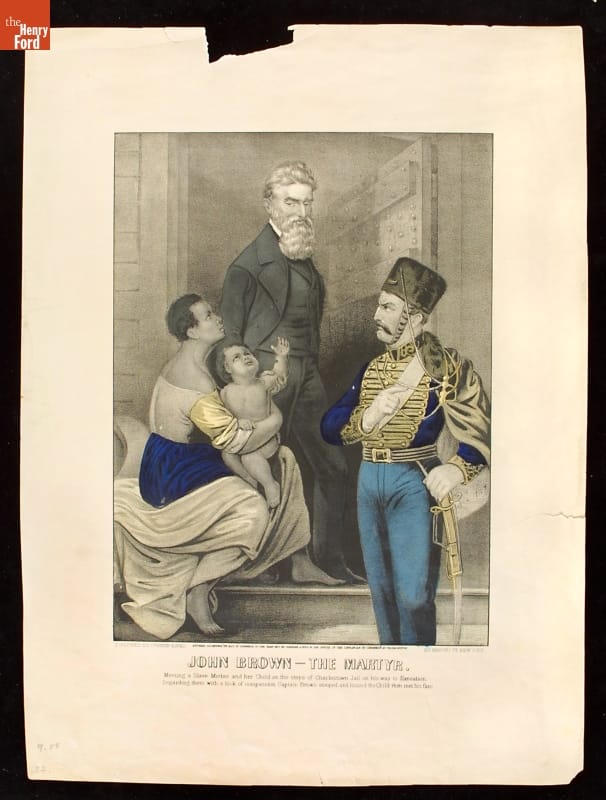

Douglass was right. Brown was captured during the raid and was subsequently tried, convicted, and executed. Brown became seen as an anti-slavery martyr, as the below print shows. Henry David Thoreau remarked about him, “No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature…”

A letter from Douglass was found among John Brown’s belongings, leading to warrants for Douglass’s arrest as a conspirator. He was lecturing in Philadelphia at the time of the discovery. John Hurn, Philadelphia’s telegraph operator, was sympathetic to the abolitionist cause. He received a dispatch for the sheriff calling for Douglass’s arrest and both sent a warning to Douglass and delayed relaying the dispatch to the sheriff. Douglass fled and made it to Canada, narrowly escaping arrest. He then went abroad on a lecture tour, resisting apprehension in the States.

The text on this Currier & Ives print reads “John Brown—The Martyr: Meeting a Slave Mother and her Child on the steps of Charlestown Jail on his way to Execution. Regarding them with a look of compassion Captain Brown stooped and kissed the Child then met his fate." This did not actually occur, but became popular lore, as well as the subject of artwork and literature. / THF8053

The Civil War & Abraham Lincoln

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. At the time, Douglass was not optimistic about the cause of abolition under Lincoln’s presidency. As tensions between the North and South grew and Civil War loomed, Douglass welcomed the impending war. As biographer David Blight states, “Douglas wanted the clarity of polarized conflict.”

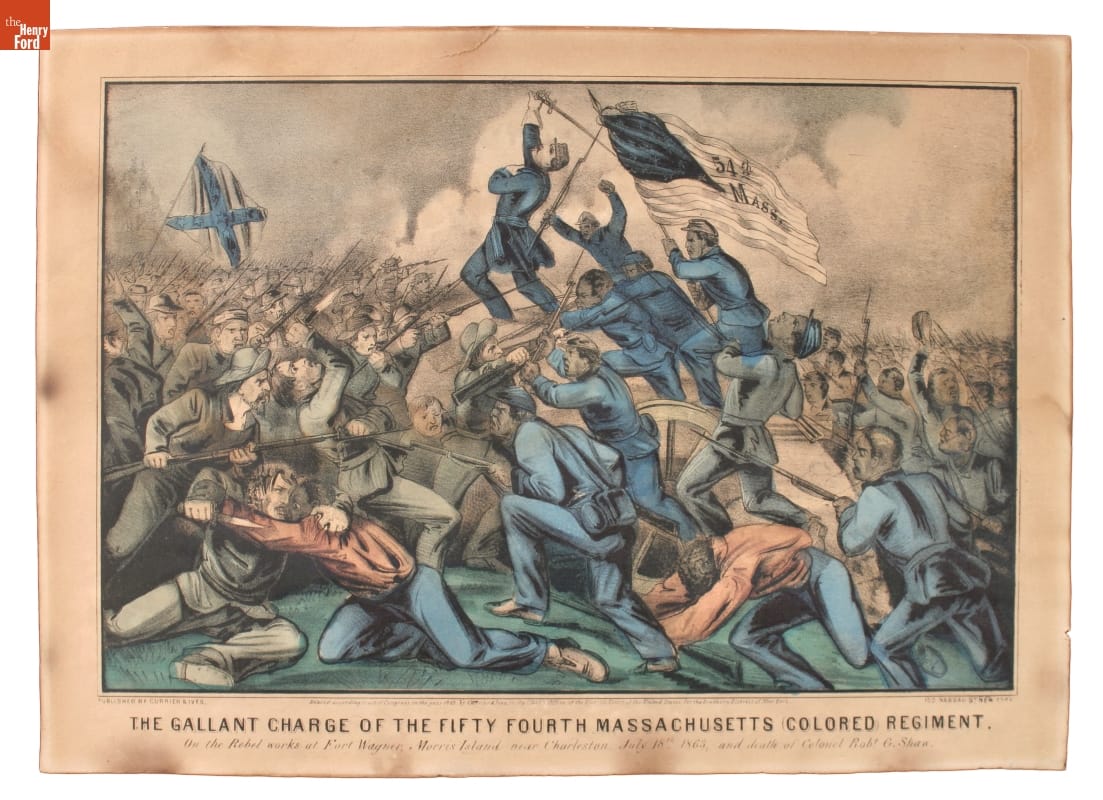

Douglass got involved in the war effort through the recruitment of Black soldiers. Two of his sons, Charles and Lewis, joined the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the second Black regiment in the Union Army. Douglass first met President Abraham Lincoln in August 1863, when he visited the White House to discuss grievances against Black troops. Even without an appointment and a room full of people waiting, Douglass was admitted to see Lincoln after just a few minutes.

Two of Frederick Douglass’s sons, Lewis and Charles, fought with the 54th Massachusetts Colored Regiment. Lewis Douglass was appointed Sergeant Major, the highest rank that a Black person could then hold. / THF73704

Douglass would go on to advise Lincoln over the following years. After Lincoln’s second inaugural address, he asked Douglass his thoughts about it, adding, “There is no man in these United States whose opinion I value more than yours.”

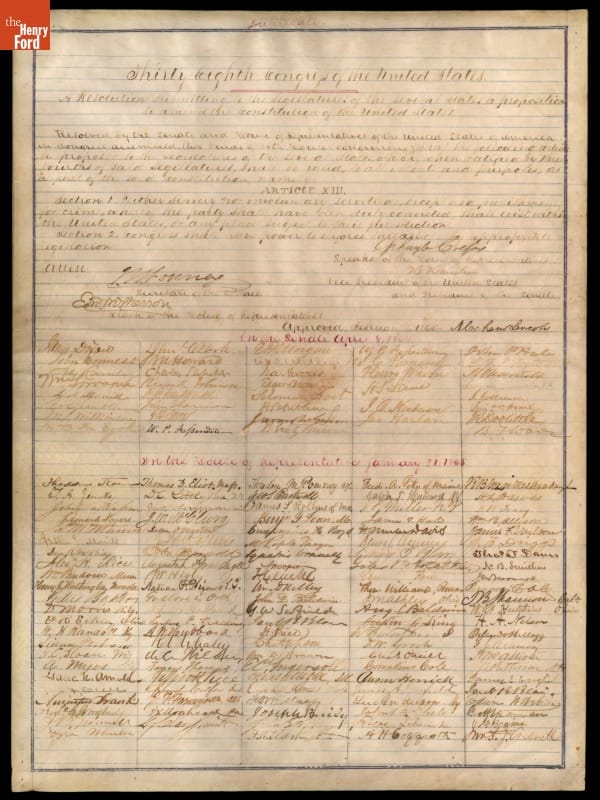

On February 1, 1865, Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of the United States Congress proposing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution—the “nail in the coffin” for the institution of slavery in the United States. But before the 13th Amendment could be ratified, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on April 15, 1865. While Douglass and Lincoln certainly disagreed on many topics, Douglass remembered him fondly. In his eulogy, Douglass called Lincoln “the Black man’s president: the first to show any respect to their rights as men.”

After the Civil War and even after Reconstruction, Douglass held high-ranking government appointments—often becoming the first Black person to do so. Douglass was appointed the Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti in 1889.

While Douglass certainly supported the 13th Amendment’s abolition of slavery, he did not think it went far enough. He remarked, “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot. While the legislatures of the south retain the right to pass laws making any discrimination between black and white, slavery still lives there.” / THF118475

Douglass continued to lecture in support of his two primary causes—racial equality and women’s suffrage—until the very end. On February 20, 1895, he attended a meeting of the National Council of Women, went home, and suffered a fatal heart attack. He was 77 years old.

Frederick Douglass remains one of the most inspirational figures in American history. We can still feel the weight of the words he wrote and spoke, more than 125 years after his passing. Douglass said, “Memory was given to man for some wise purpose. The past is … the mirror in which we may discern the dim outlines of the future and by which we may make it more symmetrical.” This work continues.

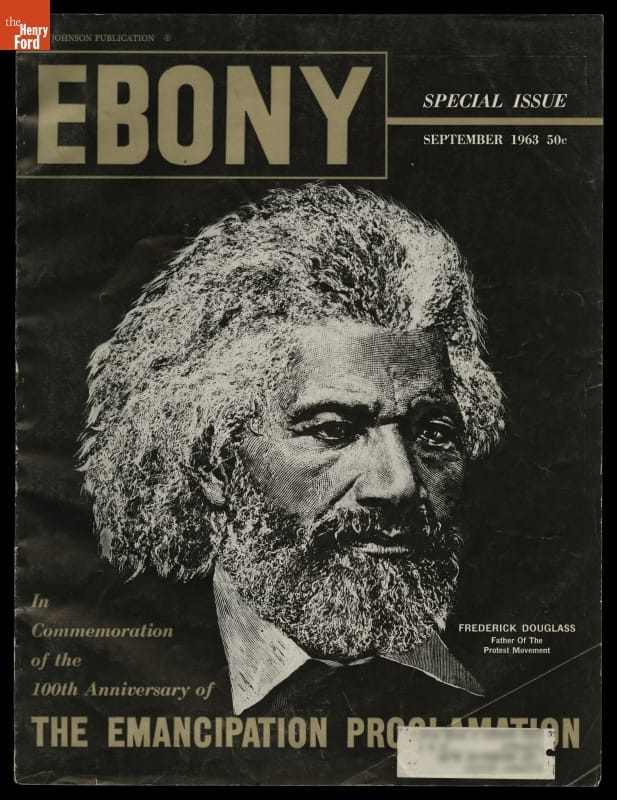

Frederick Douglass remains a powerful symbol of the fight for racial justice and equality. Here, his image graces the cover of Ebony Magazine’s issue celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. / THF98736_REDACTED

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. She appreciated the recently published book by David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, as she conducted research for this post.

Maryland, women's history, voting, Massachusetts, education, Civil War, Civil Rights, by Katherine White, books, African American history, Abraham Lincoln, 19th century, #THFCuratorChat

The Montgomery Bus Boycott in the News

This April 1956 issue of Liberation magazine featured the Montgomery bus boycott on its cover. / THF139343

In the 2021 book, Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, Civil Rights movement leader Julian Bond (1940–2015) stated that the Montgomery bus boycott provides a case study of how a social movement starts, develops, and grows. Such movements, Bond continued, begin with a concrete, precipitating event (in this case, Rosa Parks’s arrest), but they are usually the result of known or shared incidents on the part of the participants. A successful movement, he added, contains agitation, fosters fellowship, sustains morale, and develops tactics. The Montgomery bus boycott embodied all of these things—aided by both the words and actions of well-known leaders, such as Reverends Martin Luther King, Jr., and Ralph Abernathy, and the active involvement of countless others.

This 1957 comic book, produced by the international Fellowship of Reconciliation, highlighted the leadership of Martin Luther King, as well as featuring Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott. / THF110738

How did the Montgomery bus boycott begin? By 1955, Black activists and community leaders in Montgomery, Alabama, were exploring the idea of a city-wide bus boycott—an organized refusal to ride the buses after decades of humiliating incidents and indignities that the Black community suffered. But they knew they would need the united support of the city's African American bus riders, a notion that was unprecedented, untested, and likely to fail, given past experience. After some fits and starts in trying to find an appropriate test case, they finally found that test case when Rosa Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955, for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a city bus. Rosa Parks’s arrest led directly to a city-wide bus boycott, during which members of the Black community willingly walked, shared rides, and worked out carpools for 381 days—despite continual resistance from white segregationists in the community.

Bus in which Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, currently in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF134576

Accompanying The Henry Ford’s acquisition of the Rosa Parks bus in 2001 was a binder of newspaper clippings recounting the events of Rosa Parks’s arrest and the ensuing bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. These had been clipped, dated, taped onto pieces of blank white paper, and compiled in chronological order into a binder by Montgomery bus station manager Charles “Homer” Cummings.

I had initially naively thought that these articles would contain a neat, objective recounting of the bus boycott. A closer perusal, however, revealed that this was, of course, not the case. Newspaper journalists write with a story-based angle in mind, one that will capture the attention of their readers—and these accounts are no exception. Moreover, even though the newspapers included here—primarily the Montgomery Advertiser—had a large following among both Black and white citizens, the journalists who wrote these articles were white, as were the newspaper company owners, the Montgomery city bus company owners and operators, and the local Montgomery government that maintained ties with both of these.

Keeping these perspectives in mind, this selection of clippings—with occasional added content to provide context—provides a portal to the events that unfolded during the first three months of the twelve-month boycott. These clippings not only offer a powerful lens into how quickly and deeply the boycott divided members of the Montgomery community, but they also uncover a clear sense of the Black community’s collective strength and resilience when faced with continual obstacles.

Note that the images below were adapted from the original articles to emphasize the headlines; if you want to read the entire articles or see the original scrapbook pages, you can find links to those pages in the image captions. “5000 at Meeting Outline Boycott; Bullet Clips Bus,” by Joe Azbell, Montgomery Advertiser, December 5, 1955 / adapted from THF147008

“5000 at Meeting Outline Boycott; Bullet Clips Bus,” by Joe Azbell, Montgomery Advertiser, December 5, 1955 / adapted from THF147008

As the boycott began, an estimated 90–100% of local African Americans chose to participate. They walked, shared rides, and worked out carpools

This “mass demonstration of black pride” took by surprise the city’s white leaders, who were certain the boycott would end soon. Mayor W.A. Gayle was said to have remarked, “comes the first rainy day and the Negroes will be back on the buses.

But the Black community held fast and strengthened their resolve, inspired by ongoing mass meetings led by community and church leaders. Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., arose as a key leader, increasingly articulating a vision for nonviolent protest.

“Negroes to Continue Boycott,” Montgomery Advertiser, December 5, 1955 / adapted from THF147011

According to this article, on the evening of the first day of the boycott, “an estimated 5000 hymn-singing Negroes” packed the Holt Street Baptist Church and voted to continue “a racial boycott against the Montgomery City buses.” The “emotional group” unanimously passed a resolution “with roaring applause” to extend the boycott beyond the first day, refraining from riding city buses “until the bus situation is settled to the satisfaction of its patrons.”

Detailed in the article is the speech given at the meeting by “the Rev. M.L. King, pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church,” who told the crowd that the “tools of justice” must be used to attain the “day of freedom, justice and equality.” He urged “unity of Negroes,” for “we must stick together and work together if we are to win and we will win in standing up for our rights as Americans.”

City officials assumed there would be violence but found little. The headline of this article reported that a bullet hit the rear of a city bus but further reading revealed that the bus driver could not determine from where it had been fired.

“Bus Boycott Conference Fails to Find Solution,” Montgomery Advertiser, December 9, 1955 / adapted from THF147024

On December 8, a delegation of Black leaders issued a formal list of requests to the city bus company and political officials, one of several attempts to reach a compromise. Led by Rev. King, the Black delegation assured bus company officials that “they were not demanding an end to segregated seating (as this was the law).” Instead, they issued three requests: more courteous treatment on the buses; the hiring of Black drivers on routes serving Black neighborhoods; and a first-come-first-serve seating by race, back to front and front to back, with no one having to give up their seat or stand over an empty seat.

City and bus company officials expressed surprise at these grievances and refused to comply with them. The bus company responded only by disciplining a few of its employees while avoiding the larger questions of systemic racial inequity and injustice on city buses. They also declared that they had no intention of hiring “Negro drivers” (stating “the time is not right in Montgomery”) and dismissed the third demand as illegal under existing segregation laws.

According to the article, Rev. King’s response was simple: “We are merely trying to peacefully obtain better accommodations for Negroes.”

“Notice to Bus Patrons,” Montgomery Advertiser, December 10, 1955 / adapted from THF147026

The Montgomery city bus company, lacking its usual business, soon raised fares, cut services to Black neighborhoods, begged local citizens to use the buses for Christmas shopping, and asked the city for help. The year ended with the mayor and other city officials determined to get tough, to find new ways of dealing with the Black community’s united display of nonviolent resistance to segregation with their own united response.

“Negro Rule in Boycott Is to Walk,” Alabama Journal, December 12, 1955 / adapted from THF147029

As the boycott continued into the second week, Black taxicab operators told their drivers to charge only 10 cents a person for Black passengers—the same price as bus fare. Almost immediately, Police Commissioner Clyde Sellers threatened to arrest any Black taxi driver who charged less than the minimum 45-cent fare.

Responding to this, Black leaders implemented a carpool system to support citizens taking part in the boycott. They called on car owners to volunteer their vehicles and urged those with licenses to volunteer as drivers. Ministers also volunteered to drive cars. These “car pools” had to be organized and executed precisely, with an intricate web of pickup and drop-off points that were developed by postal workers who knew the layout of neighborhoods.

Eventually 275 to 300 Black-owned vehicles transported thousands of boycotters, while thousands more walked. As the article described, “None thumbed rides. As each car passed, the Negro driver would inquire of the men and women on the street corner where they were going. If they were going in the same direction, they loaded in.” In addition, “scores of Negroes were walking, their lunches in brown paper sacks under their arms. None spoke to white people. They exchanged little talk among themselves. It was an event almost solemn.”

While the newspaper article claimed that the police were out in force to “protect” the boycotters, in fact, police harassment was formidable. Local police pulled over cars, intimidated drivers, and gave tickets for real or imagined infractions.

“White Citizens of Central Alabama / Rally to the Support of Your Central Alabama Citizens Council,” Montgomery Advertiser, December 15, 1955 / adapted from THF147035

This announcement is a membership appeal to white segregationists in the Montgomery community. In Fall 1955, a local group of the White Citizen’s Council (WCC) had been established in Montgomery to provide organized economic, political, and at times physical resistance to impending desegregation. Before the boycott, the council had less than 100 members. But after the boycott started, membership swelled to 14,000 members in three months.

The WCC played an increasing role in public life, believing that white citizens’ way of life was under siege. Whites were pressured to join—in fact, it was dangerous to be white and not join, as such people could be accused of sympathizing with the Black community.

“Mayor Stops Boycott Talk,” Montgomery Advertiser, January 24, 1956 / adapted from THF147077

In January, tensions were rising. The Montgomery bus company was on the verge of bankruptcy. WCC members supported economic reprisals. Mayor Gayle, who had been previously known as “pleasant and easy to approach,” now felt increased pressure from hardline segregationists, and urged putting an end to the boycott. Leaders of the Black community continued to take the stance that, “More than 99 per cent of the Negro citizens of Montgomery have stated their positions and it remains the same. The bus protest is still on and it will last until our proposals are given sympathetic treatment.”

But Mayor Gayle had had enough. This article describes his new “get tough” policy—stating that he would hold the line against integration and that there would be “no more discussions with the Negro boycott leaders until they are ready to end the boycott.” According to the article, Gayle remarked that, “We have pussyfooted around on this boycott long enough and it has come time to be frank and honest.” Furthermore, he made the accusation that, “The Negro leaders have proved they are not interested in ending the boycott but rather in prolonging it so that they may stir up racial strife.”

The city commissioners and members of the WCC were convinced that most Blacks wanted to ride the buses, but that they were tricked and manipulated by the boycott leaders, whom city officials began to refer to as “a group of Negro radicals.” Furthermore, they assumed that there was a single instigator behind the boycott, someone behind it who was inciting otherwise cooperative Black community members to boycott. They pinpointed Rev. King as that instigator, certain that getting rid of him would put an end to the boycott once and for all. They attacked King through words (calling him, among other names, a “troublesome outsider”) and, soon, through action.

“End to Free ‘Taxi Service,’” Montgomery Advertiser, January 25, 1956 / adapted from THF147081

One of Mayor Gayle’s first moves in his new “get tough” policy was to crack down on Black carpool drivers, especially urging white Montgomerians to halt the practice of using their automobiles as “taxi services for Negro maids and cooks who work for them.” As Gayle remarked, “When a white person gives a Negro a single penny for transportation or helps a Negro with his transportation, even if it’s a block ride, he is helping the Negro radicals who lead the boycott.” He also insisted, “We are not going to be a part of any program that will get Negroes to ride the buses again at the price of the destruction of our heritage and way of life.”

At this point, police were told to step up their issuing of tickets to Black drivers, whether they were deserved or not. They also harassed boycotters waiting at pickup stations, accusing some of “vagrancy.”

“None Injured after Bombing of King Home,” Montgomery Advertiser, January 31, 1956 / adapted from THF147091

Once city and WCC leaders (now one and the same) decided that Rev. King was the “ringleader” of the boycott, they focused their efforts on going after him. They arrested him for speeding and threw him in jail—attracting bigger and noisier mass meetings and more determination by the Black community to continue the boycott. King received threatening letters and phone calls from both angry white segregationists and members of the Ku Klux Klan.

This anger led to outright violence on January 30, when a bomb was thrown through a window of King’s home. As a crowd of about 300 anxious members of the Black community gathered outside his house, Rev. King asked the group to be “peaceful.” “I did not start this boycott,” he told the crowd. “I was asked by you to serve as your spokesman. I want it to be known the length and breadth of this land that if I am stopped this movement will not stop. If I am stopped our work will not stop. For what we are doing is right. What we are doing is just. And God is with us.”

"Grand Jurors Told to Probe Legality of Bus Boycott," Alabama Journal, February 13, 1956 / adapted from THF147126

The month of February saw both sides digging in, strengthening their resolve. The racial divide grew wider. White pushback increased, with more arrests. Black determination gained strength.

Continuing the Mayor’s “get tough” policy, a local circuit judge impaneled a Montgomery County grand jury to determine whether the bus boycott was legal. “If it is illegal,” Mayor Gayle said, “the boycott must be stopped.” He declared the jurors to be the “supreme inquisitorial body” and called the grand jury system “democracy in action.”

“Plan to End Bus Boycott is Rejected,” Mobile Register, February 21, 1956 / adapted from THF147150

This article reports that, on the eve of the grand jury report, Black leaders rejected a supposed “compromise plan for ending the boycott.” They argued that they did not see any change. The proposed seating was similar to the plan they had already rejected. Promises for driver courtesy were not called out and individual bus drivers still had the authority to assign seats. Finally, boycotters were not promised that there would be no retaliation against them for their participation in the boycott. At a mass meeting, the Black community voted to continue the boycott with a count of 3,998 to 2.

In “a prepared statement following the meeting,” Rev. Ralph Abernathy stated that, “We have walked for 11 weeks in the cold and rain. Now the weather is warming up. Therefore, we will walk on until some better proposals are forthcoming from our city fathers.”

“The protest is still on,” he confirmed, “and approximately 50,000 colored persons have stated that they will continue to walk.”

“75 Nabbed by Deputies on Boycott Indictments,” Montgomery Advertiser, February 23, 1956 / adapted from THF147165

The city called more than 200 Blacks to testify before the grand jury, including King, 23 other ministers, and all carpool drivers. The indictment was based upon an obscure 1921 state law prohibiting boycotts “without just cause or legal excuse” (and referencing an earlier 1903 law that outlawed boycotts in response to Black streetcar protests). Those indicted were accused of taking an “active part in the 12-week-old racial boycott” against the Montgomery City lines buses.

Rev. Abernathy called it a “a great injustice.” Many indicted boycott leaders showed defiance by voluntarily turning themselves in and drawing attention away from singular blame on Martin Luther King. Hundreds of Black spectators shouted encouragement, cheered, and applauded as leaders showed up one by one to be “taken through the arrest process at the county jail.” The act of being arrested had become a badge of honor.

"Boycotters Plan ‘Passive’ Battle," Montgomery Advertiser, February 24, 1956 / adapted from THF147180

The boycott indictments strengthened the resolve of the Black community. At a mass meeting that an estimated 5,000 attended, Black leaders called for a Prayer and Pilgrimage Day and asked all Black citizens to walk that day.

The Central Alabama White Citizens Council was incensed about the continuation of the boycott. State Senator Sam Englehardt of Macon County, Chairman of the Central Alabama Citizens’ Council, said, “If these people [who were indicted] succeed in getting the Negroes of Montgomery to break this law, and get away with it, then who’s to say what unlawful act they will advocate next?”

Rosa Parks reflected the feelings of the Black community that day by remarking, “The white segregationists tried to put pressure to stop us. Instead of stopping us, they would encourage us to go on.”

These events, as documented through a selection of newspaper clippings compiled in a bus manager’s scrapbook, mark just the first three months of the Montgomery bus boycott. The boycott went on to last more than one year—381 days to be exact—with members of the Black community enduring continual arrests, bombings, jailing, threats, and general harassment until the U.S. Supreme Court finally declared segregation on Alabama buses to be unconstitutional. Before it was over, it would become what Julian Bond referred to in his book as nothing short of “a struggle to achieve democracy in the mid-20th century.”

For more on Rosa Parks and what led to the Montgomery bus boycott, see also Segregated Travel and the Uncommon Courage of Rosa Parks and Anniversary of Rosa Parks’ Arrest: December 1, 1955.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks also to Hannah Glodich, Graphic Designer at The Henry Ford, for adapting the original scrapbook pages into the images shown in this post.

Alabama, 20th century, 1950s, Rosa Parks bus, Rosa Parks, newspapers, Civil Rights, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

The “F” Stands for “Fun”: Jerry Lawson & the Fairchild Channel F Video Entertainment System

Jerry Lawson, circa 1980. Image from Black Enterprise magazine, December 1982 issue, provided courtesy The Strong National Museum of Play.

In 1975, two Alpex Computer Corporation employees named Wallace Kirschner and Lawrence Haskel approached Fairchild Semiconductor to sell an idea—a prototype for a video game console code-named Project “RAVEN.” Fairchild saw promise in RAVEN’s groundbreaking concept for interchangeable software, but the system was too delicate for everyday consumers.

Jerry Lawson, head of engineering and hardware at Fairchild, was assigned to bring the system up to market standards. Just one year prior, Lawson had irked Fairchild after learning that he had built a coin-op arcade version of the Demolition Derby game in his garage. His managers worried about conflict of interest and potential competition. Rather than reprimand him, they asked Lawson to research applying Fairchild technology to the budding home video game market. The timing of Kirschner and Haskel’s arrival couldn’t have been more fortuitous.

A portrait of George Washington Carver in the Greenfield Village Soybean Laboratory. Carver’s inquisitiveness and scientific interests served as childhood inspiration for Lawson. / THF214109

Jerry Lawson was born in 1940 and grew up in a Queens, New York, federal housing project. In an interview with Vintage Computing magazine, he described how his first-grade teacher put a photo of George Washington Carver next to his desk, telling Lawson “This could be you!” He was interested in electronics from a young age, earning his ham radio operator’s license, repairing neighborhood televisions, and building walkie talkies to sell.

When Lawson took classes at Queens and City College in New York, it became apparent that his self-taught knowledge was much more advanced than what he was being taught. He entered the field without completing a degree, working for several electronics companies before moving to Fairchild in 1970. In the mid-1970s, Lawson joined the Homebrew Computer Club, which allowed him to establish important Silicon Valley contacts. He was the only Black man present at those meetings and was one of the first Black engineers to work in Silicon Valley and in the video game industry.

Refining an Idea

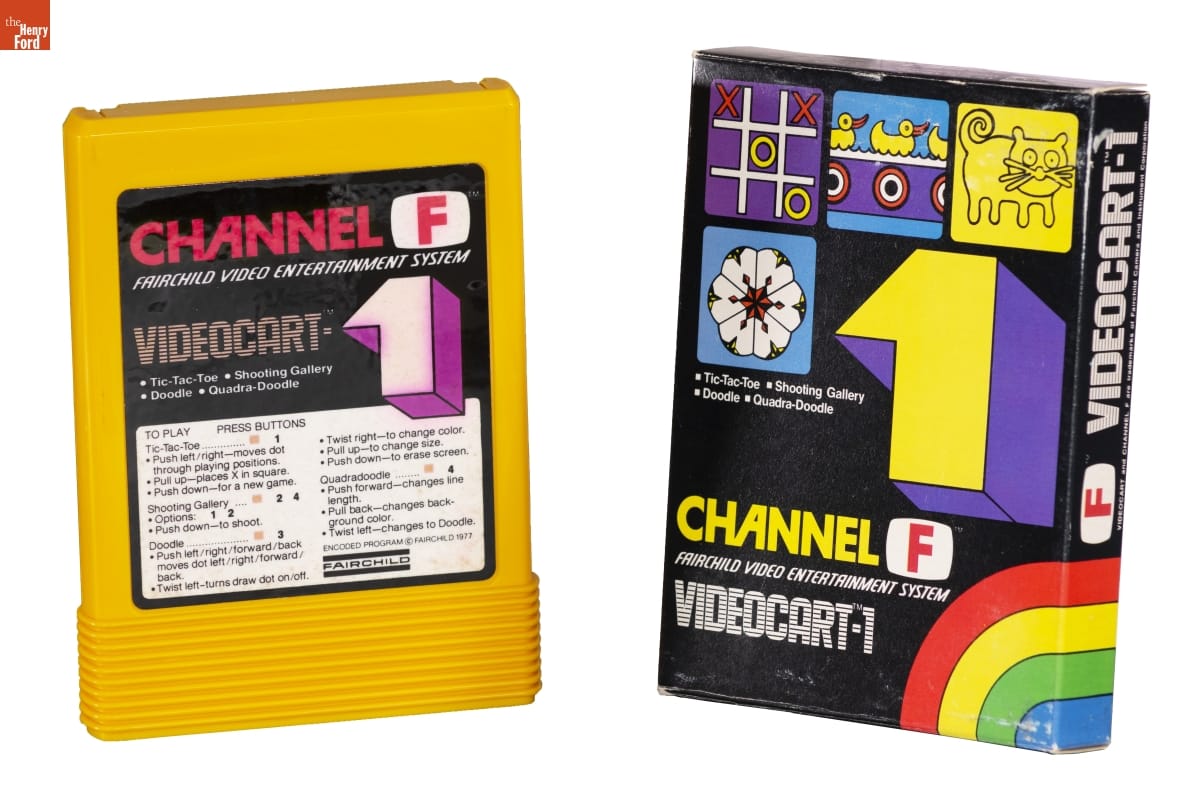

Packaging for the Fairchild Channel F Video Entertainment System. / THF185320

With Kirschner and Haskel’s input, the team at Fairchild—which grew to include Lawson, Ron Smith, and Nick Talesfore—transformed RAVEN’s basic premise into what was eventually released as the Fairchild “Channel F” Video Entertainment System. For his contributions, Lawson has earned credit for the co-invention of the programmable and interchangeable video game cartridge, which continues to be adapted into modern gaming systems. Industrial designer Nick Talesfore designed the look of cartridges, taking inspiration from 8-track tapes. A spring-loaded door kept the software safe.

A Fairchild “Video-Cart” compared to a typical 8-track tape. / THF185336 & THF323548

A Fairchild “Video-Cart” compared to a typical 8-track tape. / THF185336 & THF323548

Until the invention of the video game cartridge, home video games were built directly onto the ROM storage and soldered permanently onto the main circuit board. This meant, for example, if you purchased one of the first versions of Pong for the home, Pong was the only game playable on that system. In 1974, the Magnavox Odyssey used jumper cards that rewired the machine’s function and asked players to tape acetate overlays onto their television screen to change the game field. These were creative workarounds, but they weren’t as user-friendly as the Channel F’s “switchable software” cart system.

THF151659

Jerry Lawson also sketched the unique stick controller, which was then rendered for production by Talesfore, along with the main console, which was inspired by faux woodgrain alarm clocks. The bold graphics on the labels and boxes were illustrated by Tom Kamifuji, who created rainbow-infused graphics for a 7Up campaign in the early 1970s. Kamifuji’s graphic design, interestingly, is also credited with inspiring the rainbow version of the Apple Computers logo.

The Fairchild Video Entertainment System with unique stick controllers designed by Lawson. / THF185322

The Video Game Industry vs. Itself

The Channel F was released in 1976, but one short year later, it was in an unfortunate position. The home video game market was becoming saturated, and Fairchild found itself in competition with one of the most successful video game systems of all time—the Atari 2600. Compared to the types of action-packed games that might be found in a coin-operated arcade or the Atari 2600, many found the Channel F’s gaming content to be tame, with titles like Math Quiz and Magic Numbers. To be fair, the Channel F also included Space War, Torpedo Alley, and Drag Race, but Atari’s graphics quality outpaced Fairchild’s. Approximately 300,000 units of Channel Fun were sold by 1977, compared to several million units of the Atari 2600.

Channel F Games (see them all in our Digital Collections)

Around 1980, Lawson left Fairchild to form Videosoft (ironically, a company dedicated to producing games and software for Atari) but only one cartridge found official release: a technical tool for television repair called “Color Bar Generator.” Realizing they would never be able to compete with Atari, Fairchild stopped producing the Channel F in 1983, just in time for the “Great Video Game Crash.” While the Channel F may not be as well-known as many other gaming systems of the 1970s and 80s, what is undeniable is that Fairchild was at the forefront of a new technology—and that Jerry Lawson’s contributions are still with us today.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

1980s, 1970s, 20th century, New York, video games, toys and games, technology, making, home life, engineering, design, by Kristen Gallerneaux, African American history

Wendell Scott: Breaking NASCAR’s Color Barrier

Wendell Scott, NASCAR’s first full-time Black driver, used this 1966 Ford Galaxie, currently on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, during the 1967–68 seasons. (Vehicle on loan courtesy of Hajek Motorsports. Photo credit: Wes Duenkel Motorsports Photography.)

Stock car racing is a difficult business. Budgets and schedules are tight, travel is grueling, and competition is intense. Imagine facing all of these obstacles together with the insidious challenge of racism. Wendell Scott, the first African American driver to compete full-time in NASCAR’s top-level Cup Series, overcame all of this and more in his winning and inspiring career.

Portrait of Wendell Scott from the February 1968 Daytona 500 program. / THF146968

Born in Danville, Virginia, in 1921, Scott served in the motor pool during World War II, developing skills as a mechanic that would serve him well throughout his motorsport career. He started racing in 1947, quickly earning wins on local stock car tracks. Intrigued by the new National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR), formed in 1948, Scott traveled to several NASCAR-sanctioned events intent on competing. But each time, officials turned him away, stating that Black drivers weren’t allowed.

Undaunted, Scott continued to sharpen his skills in other stock car series. He endured slurs and taunts from crowds, and harassment on and off the track from other drivers, but he persevered. Of necessity, Scott was his own driver, mechanic, and team owner. Gradually, some white drivers came to respect Scott’s abilities and dedication to the sport. Through persistence and endurance, Scott obtained a NASCAR competition license and made his Cup Series debut in 1961. He started in 23 races and earned five top-five finishes in his inaugural season. On December 1, 1963, with his victory in a 100-mile race at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida, Wendell Scott became the first Black driver to win a Cup Series event.

Wendell Scott on the track—in a 1965 Ford Galaxie—in 1966. / THF146962

But that win did not come easy—even after the checkered flag fell. The track was rough, many drivers made multiple pit stops, and no one was sure just how many laps some cars had completed, or who truly had the lead. Initially, driver Buck Baker was credited with the victory. Baker went to Victory Lane, posed for photos, addressed the press, and headed home. Wendell Scott was certain that he had won and, as was his right, immediately requested a formal review. After two hours, officials determined that Scott was, in fact, the true winner. Scott received the $1,000 cash prize, but by that time the ceremony, the trophy, and the press were long gone. (The Jacksonville Stock Car Racing Hall of Fame presented Scott’s widow and children with a replica of the missing trophy in 2010—nearly 50 years later.)

Throughout his career, Scott never had the support of a major sponsor. He stretched his limited dollars by using second-hand cars and equipment. During the 1967–68 seasons, he ran a 1966 Ford Galaxie he acquired from the Holman-Moody racing team. That Galaxie was one of 18 delivered from Ford Motor Company to Holman-Moody for the 1965–66 NASCAR seasons. During the 1966 season, Cale Yarborough piloted the Galaxie under #27. Scott campaigned the car under his own #34, notably driving it at the 1968 Daytona 500 where he finished seventeenth.

Cale Yarborough at the wheel of the 1966 Ford Galaxie at that year’s Daytona 500. / THF146964

Wendell Scott’s Cup Series career spanned 13 years. He made 495 starts and earned 147 top-ten finishes. He might have raced longer if not for a serious crash at Talladega Superspeedway in 1973. Scott’s injuries put him in the hospital for several weeks and persuaded him to retire from competitive driving. Scott passed away from cancer in 1990, but not before seeing his life story inspire the 1977 Richard Pryor film Greased Lightning.

Scott’s 1966 Ford Galaxie is on loan to The Henry Ford courtesy of Hajek Motorsports, which previously loaned the car to the NASCAR Hall of Fame in Charlotte, North Carolina. We are proud to exhibit it, and to share the story of a pioneering driver who overcame almost every conceivable challenge in his hall-of-fame career.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

race car drivers, race cars, 1960s, 20th century, racing, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars, by Matt Anderson, African American history

The Rise of the American Carding Mill

THF91531 (photographed by John Sobczak)

Carding mills became extremely popular in 19th-century America because the machines used in them mechanized the laborious hand process of straightening and combing wool fibers—an important step in preparing yarn and making woolen cloth. Customers were happy to let others handle this incredibly tedious job while using their own skill and creativity to control the final product.

Before carding mills, farm families prepared wool by hand using hand cards like these. / THF183701

Between 1840 and 1880, Michigan farmers raised millions of sheep, whose wool was turned into yarn and woolen goods. The Civil War, especially, caused a demand for wool, as it became the raw material for soldiers’ uniforms. Afterward, while the highest quality woolen broadcloth for men’s clothing was still imported from England, a growing number of wool mills (mostly small and local, but some larger ones, especially in New England) produced lower-end woolen goods like flannel (for work shirts, summer coats, and overcoat linings), men’s and children’s underwear, blankets, and rugs.

Sheep graze outside of Henry Ford’s boyhood home in Greenfield Village / THF1937

Farmers who raised large flocks of sheep might sell their raw wool to local merchants or to dealers who shipped it directly to a small wool mill in the local area or a large wool mill in New England. But most farm families raised a modest flock of sheep and spun their own wool into yarn, which they used at home for knitted goods. They might also take their spun yarn or items they knitted to their local general store for credit to purchase other products they needed in the store.

While sawmills and gristmills were the first types of mills established in newly-formed communities, carding mills rapidly became popular—particularly in rural areas where sheep were raised. While the tradition of wool spinning at home continued well into the 19th century, machine carding took the tedious process of hand carding out of the home. Learn more about the mechanization of carding in this blog post.

Faster and more efficient carding machines replaced traditional carding methods in the 19th century. / THF621302

At the carding mill, raw wool from sheep was transformed into straightened rolls of wool, called rovings—the first step to finished cloth. Faster and more efficient carding machines at these mills replaced the hand cards traditionally used at home (by women and children) for this process. Through the end of the 19th century, carding mills provided this carding service for farm families, meeting the needs of home spinners.

“Picked” wool that has been loosened and cleaned, ready to be fed into a carding machine / THF91532 (photographed by John Sobczak)

Young Henry Ford was a member one of these farm families. Henry fondly remembered accompanying his father on trips to John Gunsolly’s carding mill (now in Greenfield Village) from their farm in Springwells Township (now part of Dearborn, Michigan)—traveling about 20 miles and waiting to have the sheared wool from his father’s sheep run through the carding machine. There it would be combed, straightened, and shaped into loose fluffy rovings, ready for spinning. The Ford family raised a modest number of sheep (according to the 1880 Agricultural Census, the family raised 13 sheep that year), so they likely brought the rovings back to spin at home, probably for knitting.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

farm animals, manufacturing, making, home life, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Donna R. Braden, agriculture

Food Soldiers: Nutrition and Race Activism

A pattern of Black activism exists, a pattern evident in the work of individuals who dedicate themselves to improving the health and wellbeing of others. These individuals may best be described as “food soldiers.” They arm themselves with evidence from agricultural and domestic science. They build their defenses one market garden at a time. They ally with grassroots activists, philanthropists, and policy makers who support their cause. Past action informs them, and they in turn inspire others to use their knowledge to build a better nation.

June Sears, Rosemary Dishman, and Dorothy Ford Discussing Women's Nutrition, May 1970. / THF620081

Food Sources

Food is one of life’s necessities (along with clothing and shelter). Centuries of legal precedent confirmed the need for employers to provide a food allowance (a ration), as well as clothing and shelter, to “bound” employees. For example, a master craftsman had to provide life’s necessities to an indentured servant, contracted to work for him for seven years, or a landowner was legally required (though adherence and enforcement varied) to provide food, clothing, and shelter to an enslaved person, bound to labor for life. This legal obligation changed after the Civil War with the coming of freedom.

Landowner R.J. Hart scratched out the clause in a contract that obligated him to furnish “healthy and substantial rations” to a freedman in 1868. Hart instead furnished laborer Henry Mathew housing (“quarters”) and fuel, a mule, and 35 acres of land. In exchange, Mr. Mathew agreed to cultivate the acreage, to fix fencing, and to accept a one-third share of the crop after harvest. The contract did not specify what Mr. Mathew could or should grow, but cotton dominated agriculture in the part of Georgia where he lived and farmed after the Civil War.

Cotton is King, Plantation Scene, Georgia, 1895 / THF278900

This new agricultural labor system—sharecropping—took hold across the cotton South. As the number of people laboring for a share of the crops increased, those laborers’ access to healthy foods decreased. Instead of gardening or raising livestock, sharecroppers had to concentrate on cash-crop production—either cotton or more localized specialty crops such as sugar cane, rice, or tobacco. Anything they grew for themselves on their landlord’s property went first to the landlord.

Postcard, "Weighing Cotton in the South," 1924 / THF8577

With no incentive or opportunity to garden, sharecroppers had few options but to buy groceries on credit from local merchants, who often were also the landowners. A failed crop left sharecroppers even more indebted, impoverished, and malnourished. This had lasting consequences for all, but race discrimination further disadvantaged Black Southerners, as sociologist Stewart Tolnay documented in The Bottom Rung: African American Family Life on Southern Farms (1999).

As food insecurity increased across the South, educators added agricultural and domestic science to classroom instruction. Many schools, especially land-grant colleges, gained distinction because of this practical instruction. Racism, however, limited Black students’ access to education. Administrators secured private funding to deliver similar content to Black students at private institutes and at a growing number of public teacher-training schools across the South.

Microscope Used by George Washington Carver, circa 1900, when he taught agricultural science at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, as it was known at the time. / THF163071

Lessons in domestic science aligned with agricultural science most obviously in courses in market gardening. A pamphlet, Everyday Life at Hampton Institute, published around 1907, featured students cultivating, harvesting, and marketing fresh fruits and vegetables. Female students also processed and preserved these foods in domestic science classes. Graduates of these programs stood at the ready to share nutrition lessons. Many, however, criticized this training as doing too little to challenge inequity.

Sixth Street Market, Richmond, Va., 1908-1909 / THF278870

Undaunted food soldiers remained committed to arguing for the value of raising healthy foods to build healthy communities. They justified their advice by tying their self-help messages to other goals. Nature study, a popular approach to environmental education early in the twentieth century, became a platform on which agricultural scientist George Washington Carver built his advocacy for gardening, as Nature Study and Children’s Gardens (1910) indicates.

Nature Study and Children's Gardens, circa 1910, page 6 / THF213304

Opportunity increased as the canning industry offered new opportunities for farm families to produce perishable fruits and vegetables for shipment to processors, as well as for home use. Black experts in agriculture and domestic science encouraged Black landowning farm families that could afford the canning equipment to embrace this opportunity. These families also had some local influence and could encourage broader community investment in new market opportunities, including construction of community canning centers and purchase of canning equipment to use in them.

The Canning and Preserving of Fruits and Vegetables in the Home, 1912 / THF288039

Nutritionists who worked with Black land-owning farm families reached only about 20 percent of the total population of Black farmers in the South. Meeting the needs of the remaining 80 percent required work with churches, clubs, and other organizations. National Health Week, a program of the National Negro Business League, began in 1915 to improve health and sanitation. This nation-wide effort put the spotlight on need and increased opportunities for Black professionals to coordinate public aid that benefitted families and communities.

Nutritionists advocated for maternal health. This studio portrait features a woman with two children, circa 1920, all apparently in good health. / THF304686

New employment opportunities for nutritionists became available during the mid-1910s. Each Southern state created a “Negro” Division within its Agricultural Extension Service, a cooperative venture between the national government’s U.S. Department of Agriculture and each state’s public land-grant institution. Many hired Black women trained at historically Black colleges across the South. They then went on the road as home demonstration agents, sharing the latest information on nutrition and food preservation.

Woman driving Chevrolet touring car, circa 1930. Note that the driver of this car is unidentified, but she represents the independence that professional Black women needed to do their jobs, which required travel to clients and work-related meetings. / THF91594

Class identity affected tactics. Black nutritionists were members of the Black middle class. They shared their wellness messages with other professional women through “Colored” women’s club meetings, teacher conferences, and farmer institutes.

Home economics teachers and home demonstration agents worked as public servants. Some supervisors advised them to avoid partisanship and activist organizations, which could prove difficult. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), most noted for attacking inequity through legal challenges, first hosted Baby Contests in 1924. These contests had double meanings. For nutritionists, healthy babies illustrated their wellness message. Yet, “Better Baby” contests had a longer history as tools used by eugenicists to illustrate their race theory of white supremacy. The most impoverished and malnourished often benefitted least from these middle-class pursuits.

Button, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 1948 / THF1605

Nutrition

Nutrition became increasingly important as science linked vitamins and minerals to good health. While many knew that poor diets could stunt growth rates and negatively affect reproductive health, during the 1920s and 1930s medical science confirmed vitamins and minerals as cures for some diseases that affected children and adults living in poverty. This launched a virtual revolution in food processing as manufacturers began adding iodine to salt to prevent goiters, adding Vitamin D to milk to prevent rickets, and adding Vitamin B3 to flour, breads, and cereals to prevent pellagra.

"Blue Boy Sparkle" Milk Bottle, 1934-1955 / THF169283

It was immediately obvious that these cures could help all Americans. The American Medical Association’s Committee on Foods called for fortifying milk, flour, and bread. The National Research Council first issued its “Recommended Dietary Allowances” in 1941. Information sharing increased during World War II as new wartime agencies reiterated the benefits of enriched foods.

World War II Poster, "Enrichment is Increasing; Cereals in the Nutrition Program," 1942 / THF81900

Black nutritionists played a significant role in this work for many reasons. They understood that enriched foods could address the needs of Black Americans struggling with health concerns. They knew that poverty and unequal access to information could slow adoption among residents in impoverished rural Black communities. Black women trained in domestic science or home economics also understood how racism affected health care by reducing opportunities for professional training and by segregating care into underfunded and underequipped doctor’s offices, clinics, and hospitals. That segregated system further contributed to ill health by adding to the stress level of individuals living in an unequal system.

Mobilization during World War II offered additional opportunities for Black nutritionists. The program for the 1942 Southern Negro Youth Conference at Tuskegee Institute addressed “concrete problems which the war has thrust in the forefront of American life.” Of the conference’s four organizing principles, two spoke directly to the aims of food soldiers: "How can Negro youth on the farms contribute more to the nation’s war production effort?” and “How can we strengthen the foundations of democracy by improving the status of Negro youth in the fields of: health and housing; education and recreation; race relations; citizenship?”

Program for the 5th All -Southern Negro Youth Conference, "Negro Youth Fighting for America," 1942 / THF99161

Extending the Reach

Food soldiers knew that the poorest suffered the most from malnutrition, but times of need tended to result in the most proactive legislation. For example, high unemployment during the Great Depression led to increased public aid. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) built new schools with cafeterias and employed dieticians to establish school lunch programs. Impoverished families also had access to food stamps to offset high food prices for the first time in 1939 through a New Deal program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Elizabeth Brogdon, Dietitian at George Washington Carver School, Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1947 / THF135669

Elizabeth Speirs Brogdon (1915–2008) opened school lunchrooms under the auspices of the WPA in 19 Georgia counties for six years. She qualified for her position with a B.S. in home economics from Georgia State College for Women, the state’s teacher’s college, and graduate coursework in home economics at the University of Georgia (which did not officially admit women until after she was born).

While Mrs. Brogdon could complete advanced dietetics coursework in her home state, Black women in Georgia had few options. The Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth, designated as Georgia’s Black land-grant school at the time, did not admit women as campus residents until 1921, and did not offer four-year degrees until 1928. Black women seeking advanced degrees in Home Economics earned them at Northern universities.

Flemmie Pansy Kittrell (1904–1980), a native of North Carolina and graduate of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, became the first Black woman to hold a PhD in nutrition (1938) from Cornell University. Her dissertation, “A Study on Negro Infant Feeding Practices in a Selected Community of North Carolina,” indicated the contribution that research by Black women could have made, if recognized as valid and vital.

Increased knowledge of the role of nutrition in children’s health informed Congress’s approval of the National School Lunch Program in 1946. In addition to this proactive legislation, some schools, including the school in Richmond Hill, Georgia, where dietitian Elizabeth Brogdon worked, continued the tradition of children’s gardens to ensure a fresh vegetable supply.

Child in a School Vegetable Garden, Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1940 / THF288200

The pace of reform increased with the arrival of television. The new medium raised the conscience of the nation by broadcasting violent suppression of peaceful Civil Rights demonstrations. This coverage coincided with increased study of the debilitating effects of poverty in the United States. Michael Harrington’s book The Other America (1962) increased support for national action to address inequity, including public health. President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s “War on Poverty” became a catalyst for community action, action that Kenneth Bancroft Clark analyzed in A Relevant War Against Poverty (1969).