Posts Tagged by saige jedele

The History of Historic Base Ball in Greenfield Village

In 1993, inspired by a handful of century-old newspaper references, nine employees volunteered to form The Henry Ford’s first historic base ball club. What started small has become a grand and beloved Greenfield Village tradition, guided—as it was from the beginning—by a passion for authenticity.

The Greenfield Village Lah-De-Dahs and the general store that spurred the club’s formation, 1994. / THF136301

Beginnings

It all began with Greenfield Village’s general store. New research in the 1990s initiated a more accurate historical interpretation of the J.R. Jones General Store as it existed in Waterford, Michigan, during the 1880s. It also turned up references to a local amateur base ball club—the Lah-De-Dahs—in period newspapers. Employees eagerly set about reviving the Lah-De-Dahs as a historic base ball club. A clue about the original uniform came from a colorful report on the Lah-De-Dahs’ poor showing in a summer 1887 game:

As the contest went on, slowly but surely dawned upon the minds of all the truth that a fine uniform does not constitute a fine pitcher, nor La-de-dahs in their mammas’ red stockings make swift, unerring fielders. —Pontiac Bill Poster, September 14, 1887

The revived Lah-De-Dahs of Greenfield Village wore white base ball shirts with a red script “L” and, at first, nondescript white painter’s pants. (The Henry Ford’s period clothing studio soon produced matching, knickers-style bottoms.) That first season, the Lah-De-Dahs played a handful of matches with rules pieced together from various historical interpretations. At Firestone Farm, the club challenged farmhands in the harvested wheat field before whatever crowd gathered along the lane. The Lah-De-Dahs also hosted a few outside historic base ball clubs at their future home field, Walnut Grove.

Structure

Historic base ball in Greenfield Village quickly assumed a more structured form that incorporated thoughtful details rooted in history—beginning with the name of the sport itself. Virtually all of the earliest references to this style of bat-and-ball game in England and the United States used the hyphenated name, “base-ball.” By the late 1830s and into the 1840s, likely due to simple changes in typesetting practices, the two-word spelling, "base ball," had begun to replace "base-ball." Conventions continued to shift, with the hyphenated version reemerging in the mid-late 19th century and receiving formal backing from the U.S. Government Printing Office in 1896. But years earlier, in 1884, the New York Times had explicitly changed its style guide away from "base-ball" to "baseball"—an early move toward the one-word convention that would stick. To highlight overlapping customs in the sport’s formative decades, The Henry Ford emphasizes the two-word spelling in its historic base ball program.

Henry Chadwick’s 1867 Base Ball Player's Book of Reference, the first reference book designed to teach the game of base ball, from which the current rules of play in Greenfield Village were drawn. / THF214794

For demonstration in Greenfield Village outside of Lah-De-Dahs matches, a set of rules, known as “Town Ball” or “Massachusetts Rules,” was selected from the 1860 Beadle’s Dime Base Ball Player. Written by Henry Chadwick, a sports journalist and leading promoter of base ball, this book included early rules of the game we know today, as well as the alternative “Massachusetts Rules” version of the game. This early version of baseball requires minimal equipment, calls for a soft ball, and features chaotic rules, making it a perfect choice for guests of Greenfield Village to try.

Elements added for the comfort and enjoyment of spectators on Walnut Grove appropriately reflect the 1860s setting. On select dates, the Dodworth Saxhorn Band provides musical accompaniment representing that of a period brass band. (Much of the music commonly associated with the professional game of baseball in America—including its unofficial anthem, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game”—was published two generations later.) Refreshments are served from contextual, temporary structures fitting the rural environments where 1860s base ball was played. And a uniquely designed sound system—disguised by several strategically placed waste receptacles—allows the umpire and scorekeeper to present a real-time account of the game via concealed cordless microphones. The live music and play-by-play, combined with the unpredictability of the game, make for an entertaining afternoon.

The Dodworth Saxhorn Band during the World Tournament of Historic Base Ball, 2007, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF52297

Expansion

The Lah-De-Dahs’ roster grew to 25 players over the club’s second and third seasons. They wore handmade uniforms for matches, which were held whenever visiting clubs could make the trip to Greenfield Village. By 2002, the season consisted of a dozen games played on select Saturdays throughout the summer. After nearly a decade of play, the Lah-De-Dahs had attracted a dedicated fan base, and spectators increasingly requested a regular schedule with more games.

The reopening of Greenfield Village in 2003 after a massive restoration project heightened expectations for the historic base ball program. With financial support from Edsel and Cynthia Ford, The Henry Ford delivered an entire summer of base ball with expanded offerings: daily period base ball demonstrations, formal games on Saturdays and Sundays—now played by the “New York rules” specified in Henry Chadwick’s 1867 Base Ball Player's Book of Reference (which were more familiar to spectators than the Massachusetts Rules game)—and the development of the World Tournament of Historic Base Ball.

The Henry Ford’s World Tournament of Historic Base Ball pays homage to the original “World's Tournament of Base Ball” hosted in August 1867 by the Detroit Base Ball Club. Though organizers ultimately failed to attract the world-famous clubs of the day, they managed to stage a remarkable, one-of-a-kind event. The trophy bat awarded to the Unknown Base Ball Club of Jackson, Michigan—winners of the first-class division of the 1867 tournament—is now in The Henry Ford’s collections. It is displayed each year in Greenfield Village during the World Tournament of Historic Base Ball.

Trophy bat awarded at the 1867 World's Tournament of Base Ball. / THF8654

For 2004, the Lah-De-Dahs’ season expanded from 12 to 30 games, and its roster swelled to 42 players. To make sure they always had an opponent, The Henry Ford created a second club. The National Base Ball Club takes its name from a competitor in the 1867 World's Tournament of Base Ball. New uniforms purchased for both clubs added to the already vibrant atmosphere during matches, with the Lah-De-Dahs in their now-familiar red and white and the Nationals in striking dark blue and gold. At first, many considered the Lah-De-Dahs to be Greenfield Village’s “home” club, but displays of sportsmanship and close games going to either side have endeared fans to both.

One of the close plays that have helped endear fans to both Greenfield Village clubs.

Over time, baseball became “America’s pastime,” an enduring cultural touchstone—and a multibillion-dollar business. Historic Base Ball in Greenfield Village (and also played in many other venues around the country) showcases an early form of the sport, from a time when amateurs played for recreation and innocent amusement—for the love of the game!

Brian James Egen is Executive Producer and Head of Studio Productions at The Henry Ford and Marcus W. Dickson is Professor of Industrial/Organizational Psychology at Wayne State University. This post was prepared for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

research, Historic Base Ball, by Saige Jedele, by Marcus Dickson, by Brian James Egen, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Greenfield Village, events, sports, baseball

A Rosa Parks Baseball?: Inspiring Curt Flood's Battle with Major League Baseball

Baseball autographed for All-Star centerfielder Curt Flood by one of his heroes, civil rights icon Rosa Parks. / THF96558

Baseball autographed for All-Star centerfielder Curt Flood by one of his heroes, civil rights icon Rosa Parks. / THF96558

Curt Flood was an All-Star, Gold-Glove centerfielder for the powerhouse St. Louis Cardinals baseball team of the 1960s. He undoubtedly signed thousands of baseballs during and after his career. So why would Flood save a baseball signed by Rosa Parks among his personal effects?

The ball is part of a story of inspiration, courage, and perseverance.

Inspired to Take a Stand

Curt Flood grew up in Oakland, California, and had no direct experience with the intense racism of the Jim Crow South. He was among the first generation of Black players in Major League Baseball. In 1956, as a 19-year-old minor leaguer in the Deep South, Flood came face-to-face with the virulent racial hatred that had arisen in the wake of the 1955 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in schools, and from the ongoing Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott inspired by Rosa Parks. It was the courage shown by Rosa Parks, Jackie Robinson (the player famous for breaking Major League Baseball's color barrier), and others that gave Flood the strength to persevere through his two-year minor league stint.

Flood joined the Major Leagues when he was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals in 1958. He and two of his new teammates, Bill White and Bob Gibson, became increasingly outspoken about segregationist aspects of the Cardinals operation. These men successfully pressed the organization to patronize integrated hotels and restaurants. Flood also joined Jackie Robinson at NAACP rallies across the South.

Curt Flood was featured on the August 19, 1968, cover of Sports Illustrated. The issue, pictured here with Flood’s St. Louis Cardinals hat, called him "Baseball's Best Centerfielder." / THF76590

Fighting the Reserve Clause

Flood's stellar 12-year career with the Cardinals ended suddenly in 1969, when he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. The Phillies were a team going nowhere, with a fan base and management that were hostile to Black players. Flood had little desire to be part of that team. But the reserve clause gave Flood no choice in the matter. This clause was a standard part of every baseball player's contract, requiring him to play wherever the owners wanted him to play. The player had no say in the matter.

Flood's only options were to go along with the trade or retire. His first instinct was to retire. But, after reconsidering, he decided to challenge the reserve clause and sue Major League Baseball. Flood knew that this action would, in effect, end his baseball career and that he personally would gain little in the end. But the reserve clause made Flood feel like a piece of property, and he could not let that injustice stand.

Curt Flood's letter to baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn was brief and to the point:

Dear Mr. Kuhn:

After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

It is my desire to play in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia Club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions. I, therefore, request that you make known to all the Major League Clubs my feelings in the matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.

Sincerely yours, Curt Flood

Lonely Path to the Supreme Court

As expected, Major League Baseball rejected Flood’s request. Over the next two and a half years, Flood, with the support of Marvin Miller of the Players Association (the fledgling professional baseball players' union), pursued his case in court, then in appeals court, and finally to the United States Supreme Court. At the inception of the suit, Flood became one of the most hated men in baseball—he was criticized in the press for trying to destroy baseball and received mountains of hate mail from fans. But it was the lack of support from active players that hurt Flood the most. Some supported Flood privately but feared retribution if they spoke out. Others were outright hostile and tried to undermine the suit even though it would benefit all players. Only baseball outsiders testified on Flood's behalf: his hero, Jackie Robinson; Hank Greenberg, who battled anti-Semitism throughout his career with the Detroit Tigers; and the iconoclastic Bill Veeck, who had owned several major and minor league baseball teams.

Curt Flood (left) and pitcher Bob Gibson had been close friends since their days in the minor leagues. Gibson privately supported Flood in his activism, but despite being one of the best pitchers in the game, he feared he would be ostracized from baseball if he backed Flood publicly. / THF98488

The court battles took a physical and emotional toll on Flood. He fell out of shape physically and turned from a social drinker to an alcoholic. The relentless negative attention from the press and fans forced Flood out of the country, first to Denmark, and later to Spain. He lost touch with his children and, by 1975, was nearly destitute and homeless. Flood was despondent and depressed. In 1978, Richard Reeves interviewed him for Esquire magazine as part of a series on men who had stood up to the system. Reeves said, "He was about the saddest man I ever met."

The closely divided Supreme Court ruled against Flood in the end. The majority opinion said, in effect, that the reserve clause was "an anomaly," but that it was Congress's job to fix it, not the courts’. Despite the Supreme Court loss, Flood's fight had created an opening to challenge baseball's reserve clause on the bargaining table. Within a few years, Jim "Catfish" Hunter became the first free agent, followed closely by Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally. While Curt Flood lost the case, his efforts transformed the relationship between owners and players across professional sports, and for people with unique and valuable skills in the world at large.

Curt Flood signed this copy of the Supreme Court summary report of his suit against Major League Baseball. / THF98457

Recovery and Recognition

After more than a decade in a personal wilderness, Flood began to turn his life around with the help of friends. He was treated for alcoholism in 1980, re-married in 1986, gained a new family, and reconnected with the children of his first marriage. Flood took up the late Jackie Robinson's cause, pushing for more diversity in the management of baseball. Along with other former players, he co-founded a group known as the Baseball Network for that purpose.

In 1987, Curt Flood received the NAACP Jackie Robinson Sports Award. While he was never hired for a position in baseball management, Flood became a regular at old-timers’ games. There, many former players took the opportunity to thank him personally. In 1994, Flood was featured in Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary and attended the premiere, where he met President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton. Not long after, he met another hero from his youth, Rosa Parks, who signed a baseball for him. Flood wrote to friends in a Christmas letter that year, "I am in the process of living happily ever after."

In 1987, the NAACP recognized Curt Flood's fight by awarding him the Jackie Robinson Sports Award. / THF76582

In the summer of 1995, Flood developed throat cancer; he died on January 20, 1997. During that year and a half, many people visited him to express gratitude for what he had done for baseball and for society at large. At his death, Curt Flood was eulogized by many, including Jesse Jackson and conservative columnist George Will, who compared him to Rosa Parks.

Curt Flood and his wife, Judy Pace Flood, with Rosa Parks in 1994. / THF98496

While in retrospect, it may seem as though changes in society are predetermined and expected, Curt Flood's experience shows that they are not a sure thing—and they are never easy. The reserve clause was a legal anachronism that stripped players of their freedom to control their own careers. It took a successful man—inspired by heroes who had taken similar steps before him—who was willing to give up everything to make that change occur.

Jim McCabe is former Curator and Collections Manager at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran in February 2010 as part of our “Pic of the Month” series. It was updated for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

1970s, 1960s, Pennsylvania, 20th century, Missouri, sports, Rosa Parks, by Saige Jedele, by Jim McCabe, baseball, African American history

1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings Trading Card

This Cincinnati Red Stockings trading card, issued by Peck & Snyder in 1869, is one of the earliest baseball cards. / THF94408

What does an old baseball card tell us about life in the United States? This baseball card was issued by Peck & Snyder, a New York sporting goods store. It features a team photo of the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings. This card is one of the earliest baseball cards, and in many ways, it marks the emergence of the modern game as a national pastime.

Since the 1840s, baseball had been evolving rapidly from a game for children to one for gentlemen. The grown-ups soon imposed structure and standardization on the largely improvisational kids’ game. Baseball clubs formed for recreation and exercise, and friendly competition between clubs was soon part of the mix. Following the end of the Civil War, that friendly competition became more intense. Strong rivalries developed between local baseball clubs; gradually, playing for sport was replaced by playing to win. Clubs began to recruit better players. They cast nets that extended well beyond their communities and quietly offered top players various enticements to play, including jobs and cash. The best ball players gained celebrity status and came to be known far and wide. Newspapers covered their exploits, fanning the flames of "baseball fever" across the country. The spread of railroads allowed clubs to play games farther away from home.

The stage was set for the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings.

The Cincinnati Red Stockings are one of the legendary teams of baseball. Harry Wright, who played for several New York clubs before the Civil War, saw the business opportunity in baseball as a spectator sport. In 1869, Wright built a club around a nucleus of himself, his brother George, and several other strong players from teams from the eastern United States. Backed by Cincinnati investors, the Red Stockings became the first openly professional baseball team. Taking advantage of the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the Red Stockings embarked on a coast-to-coast national tour, covering 12,000 miles and playing before over 200,000 spectators. They were unbeaten in more than 70 games over two seasons, finally losing to the Brooklyn Atlantics in June 1870.

The exploits of the Red Stockings did much to popularize baseball around the nation and demonstrated that professional baseball teams could be an economic success. Major League Baseball marks its start with the Red Stockings’ national tour of 1869. The team lasted only five years (1866–1871), but Harry and George Wright went on to form the Boston Red Stockings (which eventually became the Boston-Milwaukee-Atlanta Braves) and are members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Andrew Peck, founder of Peck & Snyder, signed the reverse of this Cincinnati Red Stockings trading card. Peck & Snyder's offerings included a wide range of recreational items, from baseball equipment to accordions to magic tricks. / THF94409

Peck & Snyder was Manhattan's first sporting goods store. Founded by Andrew Peck, who got his start in 1865 making baseballs, Peck & Snyder is credited with starting the first baseball card series when the store pasted advertisements on the back of team photographs, including the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the Chicago White Stockings, the Boston Lowells, the Brooklyn Atlantics, the New York Mutuals, and the Philadelphia Athletics. Along with brewers, hotel keepers, and transit companies, sporting goods makers knew that baseball was good for business.

In this card, we can see the emergence of baseball as a true national pastime—and as a business. Here was a New York store, creating a trade card with a Cincinnati team on it. The example now in the collections of The Henry Ford was important enough that it was framed—reflecting the celebrity status of the players it depicted and, perhaps, the rooting interests of its owner.

Jim McCabe is former Curator and Collections Manager at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran in May 2008 as part of our “Pic of the Month” series. It was updated for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Ohio, 19th century, 1860s, sports, popular culture, by Saige Jedele, by Jim McCabe, baseball

What Have We Been Collecting at The Henry Ford?: A Peek at Recent Acquisitions

The Henry Ford’s curatorial team works on many, many tasks over the course of a year, but perhaps nothing is as important as the task of building The Henry Ford’s collections. Whether it’s a gift or a purchase, each new acquisition adds something unique. What follows is just a small sampling of recent collecting work undertaken by our curators in 2021 (and a couple in 2020), which they shared during a #THFCuratorChat session on Twitter.

In preparation for an upcoming episode of The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, Curator of Domestic Life Jeanine Head Miller made several new acquisitions related to board games. A colorful “Welcome to Gameland” catalog advertises the range of board games offered by Milton Bradley Company in 1964, and joins the 1892 Milton Bradley catalog—dedicated to educational “School Aids and Kindergarten Material”—already in our collection.

Milton Bradley Company Catalog, “Welcome to Gameland,” 1964. / THF626388

Milton Bradley Company Trade Catalog, “Bradley’s School Aids and Kindergarten Material,” 1892. / THF626712

We also acquired several more board games for the collection, including “The Game of Life”—a 1960 creation to celebrate Milton Bradley’s centennial anniversary that paid homage to their 1860 “The Checkered Game of Life” and featured an innovative, three-dimensional board with an integrated spinner. “The Game of Life,” as well as other board games in our collection, can be found in our Digital Collections.

Board games recently acquired for use in The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation. / THF188740, THF188741, THF188743, THF188750

This year, Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content, was thrilled to unearth more of the story of designer Peggy Ann Mack. Peggy Ann Mack is often noted for completing the "delineation" (or illustration) for two early 1940s Herman Miller pamphlets featuring her husband Gilbert Rohde's furniture line. After Rohde's death in 1944, Mack took over his office. One commission she received was to design interiors and radio cases for Templetone Radio. The Henry Ford recently acquired this 1945 radio that she designed.

Radio designed by Peggy Ann Mack, 1945. / Photo courtesy Rachel Yerke

Peggy Ann Mack wrote and illustrated the book Making Built-In Furniture, published in 1950, which The Henry Ford also acquired this year. The book is filled with her illustrations and evidences her deep knowledge of the furniture and design industries.

Making Built-In Furniture, 1950. / Photo courtesy Katherine White

Mack (like many early female designers) has never received her due credit. While headway has been made this year, further research and acquisitions will continue to illuminate her story and insert her name back into design history.

Katherine White also worked this year to further expand our collection of Herman Miller posters created for Herman Miller’s annual employee picnic. The first picnic poster was created by Steve Frykholm in 1970—his first assignment as the company’s internal graphic designer. Frykholm would go on to design 20 of these posters, 18 of which were acquired by The Henry Ford in 1988; this year, we finally acquired the two needed to complete the series.

Herman Miller Summer Picnic Poster, “Lollipop,” 1988. / THF626898

Herman Miller Summer Picnic Poster, “Peach Sundae,” 1989. / THF189131

After Steve Frykholm, Kathy Stanton—a graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s graphic design program—took over the creation of the picnic posters, creating ten from 1990–2000. While The Henry Ford had one of these posters, this year we again completed a set by acquiring the other nine.

Recently acquired posters created by Kathy Stanton for Herman Miller picnics, 1990–2000 / THF626913, THF626915, THF626917, THF626921, THF189132, THF189133, THF189134, THF626929, THF626931

Along with the picnic posters, The Henry Ford also acquired a series of posters for Herman Miller’s Christmas party; these posters were created from 1976–1979 by Linda Powell, who worked under Steve Frykholm at Herman Miller for 15 years. All of these posters—for the picnics and the Christmas parties—were gifted to us by Herman Miller, and you can check them out in our Digital Collections.

Posters designed by Linda Powell for Herman Miller Christmas parties, 1976–1979 / THF626900, THF189135, THF189137, THF189136, THF189138, THF626909, THF626905

Thanks to the work of Curator of Communications and Information Technology Kristen Gallerneaux, in early 2021, a very exciting acquisition arrived at The Henry Ford: the Lillian F. Schwartz and Laurens R. Schwartz Collection. Lillian Schwartz is a groundbreaking and award-winning multimedia artist known for her experiments in film and video.

Lillian Schwartz was a long-term “resident advisor” at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey. There, she gained access to powerful computers and opportunities for collaboration with scientists and researchers (like Leon Harmon). Schwartz’s first film, Pixillation (1970), was commissioned by Bell Labs. It weaves together the aesthetics of coded textures with organic, hand-painted animation. The soundtrack was composed by Gershon Kingsley on a Moog synthesizer.

“Pixillation, 1970 / THF611033

Complementary to Lillian Schwartz’s legacy in experimental motion graphics is a large collection of two-dimensional and three-dimensional materials. Many of her drawings and prints reference the creative possibilities and expressive limitations of computer screen pixels.

“Abstract #8” by Lillian F. Schwartz, 1969 / THF188551

With this acquisition, we also received a selection of equipment used by Lillian Schwartz to create her artwork. The equipment spans from analog film editing devices into digital era devices—including one of the last home computers she used to create video and still images.

Editing equipment used by Lillian Schwartz. / Image courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

Altogether, the Schwartz collection includes over 5,000 objects documenting her expansive and inquisitive mindset: films, videos, prints, paintings, sculptures, posters, and personal papers. You can find more of Lillian Schwartz’s work by checking out recently digitized pieces here, and dig deeper into her story here.

Katherine White and Kristen Gallerneaux worked together this year to acquire several key examples of LGBTQ+ graphic design and material culture. The collection, which is currently being digitized, includes:

Illustrations by Howard Cruse, an underground comix artist…

Illustration created by Howard Cruse. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

A flier from the High Tech Gays, a nonpartisan social club founded in Silicon Valley in 1983 to support LGBTQ+ people seeking fair treatment in the workplace, as LGBTQ+ people were often denied security clearance to work in military and tech industry positions...

High Tech Gays flier. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

An AIDSGATE poster, created by the Silence = Death Collective for a 1987 protest at the White House, designed to bring attention to President Ronald Reagan’s refusal to publicly acknowledge the AIDS crisis...

“AIDSGATE” Poster, 1987. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

A number of mid-1960s newspapers—typically distributed in gay bars—that rallied the LGBTQ+ community, shared information, and united people under the cause...

“Citizens News.” / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

A group of fliers created by the Mattachine Society in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, which paints a portrait of the fraught months that followed...

Flier created by the Mattachine Society. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

And a leather Muir cap of the type commonly worn by members of post–World War II biker clubs, which provided freedom and mobility for gay men when persecution and the threat of police raids were ever-present at established gay locales. Its many pins and buttons feature gay biker gang culture of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Leather cap with pins. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

Another acquisition that further diversifies our collection is the “Nude is Not a Color” quilt, recently acquired by Curator of Domestic Life Jeanine Head Miller. This striking quilt was created in 2017 by a worldwide community of women who gathered virtually to take a stand against racial bias.

“Nude is Not a Color” Quilt, Made by Hillary Goodwin, Rachael Door, and Contributors from around the World, 2017. / THF185986

Fashion and cosmetics companies have long used the term “nude” for products made in a pale beige—reflecting lighter skin tones and marginalizing people of color. After one fashion company repeatedly dismissed a customer’s concerns, a community of quilters used their talents and voices to produce a quilt to oppose this racial bias. Through Instagram, quilters were asked to create a shirt block in whatever color fabric they felt best represented their skin tone, or that of their loved ones.

Shirt blocks on the “Nude is Not a Color” quilt. / THF185986, detail

Quilters responded from around the United States and around the world, including Canada, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, and Australia. These quilt makers made a difference, as via social media the quilt made more people aware of the company’s bias. They in turn lent their voices, demanding change—and the brand eventually altered the name of the garment collection.

Jeanine Head Miller has also expanded our quilt collection with the addition of over 100 crib quilts and doll quilts, carefully gathered by Paul Pilgrim and Gerald Roy over a period of forty years. These quilts greatly strengthen several categories of our quilt collection, represent a range of quilting traditions, and reflect fabric designs and usage—all while taking up less storage space than full-sized quilts.

A few of the crib quilts acquired from Paul Pilgrim and Gerald Roy. / THF187113, THF187127, THF187075, THF187187, THF187251, THF187197

During 2021, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment Debra Reid has been developing a collection documenting the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal program that employed around three million young men. This year, we acquired the Northlander newsletter (a publication of Fort Brady Civilian Conservation Corps District in Michigan), a sweetheart pillow from a camp working on range land regeneration in Oregon, and a pennant from a camp working in soil conservation in Minnesota’s Superior National Forest.

Recent Civilian Conservation Corps acquisitions. / THF624987, THF188543, THF188542

We also acquired a partial Civilian Conservation Corps table service made by the Crooksville China Company in Ohio. This acquisition is another example of curatorial collaboration, this time between Debra Reid and Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable. These pieces, along with the other Civilian Conservation Corps material collected, will help tell less well-documented aspects of the Civilian Conservation Corps story.

Civilian Conservation Corps Dinner Plate, 1933–1942. / THF189100

If you’ve been to Greenfield Village lately, you’ve probably noticed a new addition going in—the reconstructed Vegetable Building from Detroit’s Central Market. While we acquired the building from the City of Detroit in 2003, in 2021, Debra Reid has been working to acquire material to document its life prior to its arrival at The Henry Ford. As part of that work, we recently added photos to our collection that show it in service as a horse stable at Belle Isle, after its relocation there in 1894.

“Seventy Glimpses of Detroit” souvenir book, circa 1900, page 20. While this book has been in our collections for nearly a century, it helps illustrate changes in the Vegetable Building structure over time. / THF139104

Riding Stable at the Eastern End of Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan, October 27, 1963. / THF626103

Horse Stable on Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan, July 27, 1978. / THF626107

This year, Debra Reid also secured a photo of Dorothy Nickerson, who worked with the Munsell Color Company from 1921 to 1926, and later as a Color Specialist at the United States Department of Agriculture. Research into this new acquisition—besides leading to new ideas for future collecting—brought new attention (and digitization) to a 1990 acquisition: A.H. Munsell’s second edition of A Color Notation.

Dorothy Nickerson of Boston Named United States Department of Agriculture Color Specialist, March 30, 1927. / THF626448

All of this is just a small part of the collecting that happens at The Henry Ford. Whether they expand on stories we already tell, or open the door to new possibilities, acquisitions like these play a major role in the institution’s work. We look forward to seeing what additions to our collection the future might have in store!

Compiled by Curatorial Assistant Rachel Yerke from tweets originally written by Associate Curators, Digital Content, Saige Jedele and Katherine White, and Curators Kristen Gallerneaux, Jeanine Head Miller, and Debra A. Reid for a curator chat on Twitter.

quilts, technology, computers, Herman Miller, posters, women's history, design, toys and games, #THFCuratorChat, by Debra A. Reid, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Katherine White, by Saige Jedele, by Rachel Yerke, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

FMC Cascade Tomato Harvester in Use, circa 1985 / THF146505

FMC Cascade Tomato Harvester in Use, circa 1985 / THF146505

The adoption of mechanical tomato harvesters in the 1960s both industrialized tomato production and ushered in a countermovement of small growers and local food advocates. How could one machine prompt such contradictory but real changes in agriculture? The full story spans decades and reveals complex relationships of supply and demand—for both agricultural products and the people who grow and harvest them.

Shortage and Struggle

California’s labor shortage threatened the supply of processing tomatoes for ketchup, sauces, tomato juice, canned tomatoes, and other products. Can label, "Del Monte Brand Spanish Style Tomato Sauce," circa 1930. / THF294183, detail

To meet rising demand for processing tomatoes (to be made into ketchups, sauces, tomato juice, canned tomatoes, and other products) in the early 20th century, growers needed laborers to pick them. Those laborers, in turn, needed living wages. Tensions between growers and laborers came to a head during the New Deal era of the 1930s, when government policies promised minimum wages, maximum hours, and workers’ compensation. Yet, lobbyists working for growers and agricultural processers convinced policy makers to exempt agricultural workers from these protections.

Laborers voted with their feet, seeking employment beyond farm fields. This caused a critical labor shortage that became even more acute during World War II for growers raising tomatoes and other crops in California and beyond. To meet demand, the United States and Mexican governments negotiated the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement. This guest labor program brought millions of farmworkers, known as braceros, from Mexico to work in the United States for short periods of time between 1942 and 1964.

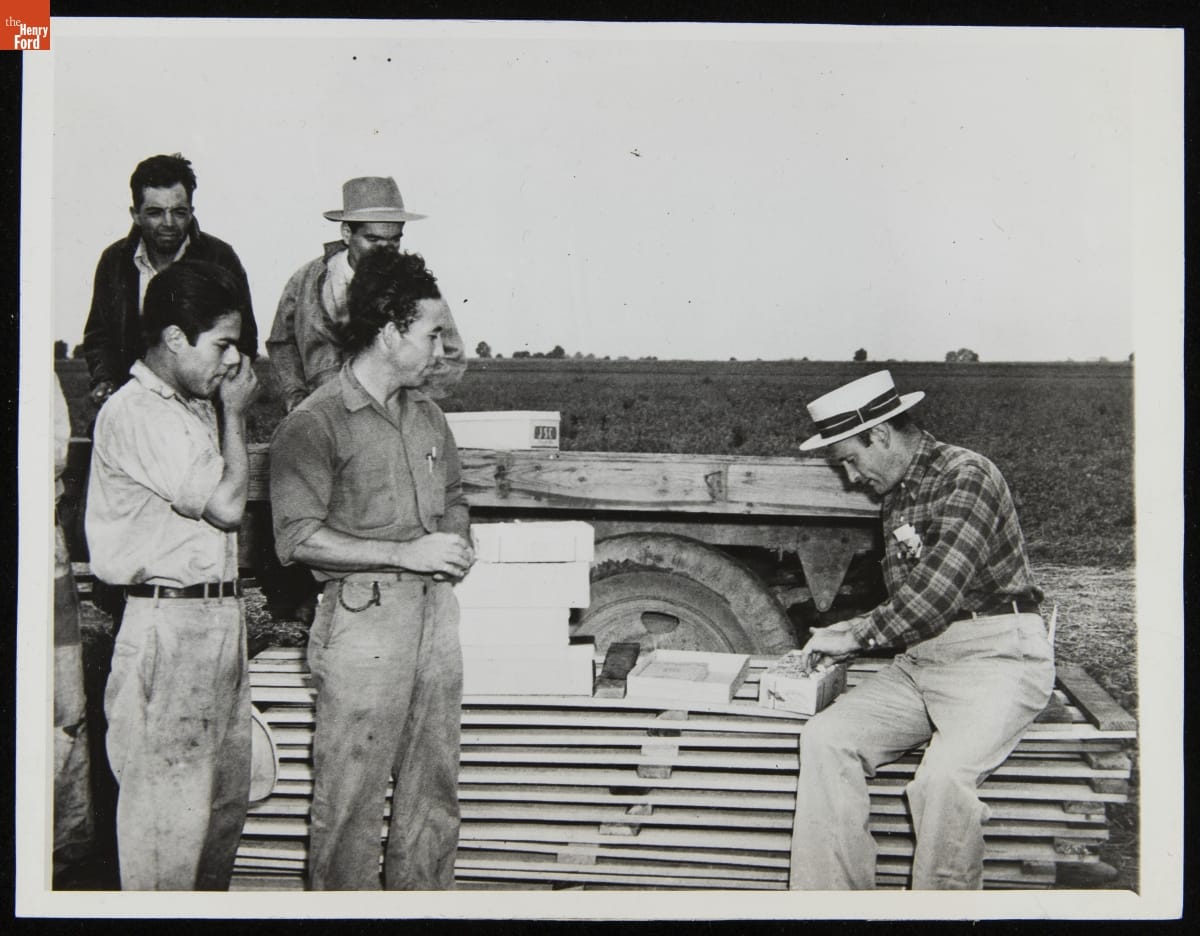

This photograph illustrated a news report on braceros resuming the tomato harvest near Danville, Illinois, in August 1945. / THF147934

A chain of events during the 1960s called attention to the plight of agricultural laborers. Edward R. Murrow’s television documentary Harvest of Shame (1960) highlighted the precarious existence of migrant laborers who worked picking perishable fruits and vegetables in the Midwest and along the East Coast. The Bracero Program expired in 1964, reducing the number of available laborers and increasing growers’ dependence on the existing labor pool. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which, along with other anti-poverty and housing legislation, made it clear that migratory and seasonal laborers had the right to humane treatment.

On the West Coast, Filipino laborers organized as part of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee. Seeking better wages and a more favorable rate of payment, they launched a grape strike that expanded into Delano, California, in 1965. The National Farm Workers Association, consisting mostly of Mexican migratory workers, joined the cause. This coordinated effort resulted in a new organization, the United Farm Workers (UFW), with Cesar Chavez as president.

The organizing efforts of groups like the United Farm Workers to secure better wages and living conditions for agricultural laborers in California gained national attention in the 1960s. United Farm Workers flag, circa 1970. / THF94392

The UFW devised innovative solutions to increase pressure on growers, and—especially due to the efforts of co-founder Dolores Huerta—built the Delano grape strike into a national boycott. This focused attention on basic needs for migratory and seasonal laborers. In addition to ensuring some protections for individuals, the coordinated effort secured the right for migratory and seasonal laborers as a class to collectively bargain.

Engineering a Solution to Labor Shortages

Tomato growers, keen on getting their crop planted, cultivated, and harvested at the optimum times, were interested in mechanical solutions that could address labor shortages. Mechanizing the harvest of this perishable commodity, however, proved to be a time-consuming challenge.

Scientists at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), sought a labor shortage solution through mechanical and biological engineering. Research and development begun in the 1940s finally resulted in the successful design of both a mechanical tomato harvester (created in partnership with Blackwelder Manufacturing Company) and a tomato that could withstand mechanical harvesting (the VF145).

Top: UC Davis vegetable crops researcher Gordie “Jack” Hanna developed the machine-harvestable VF145 tomato. Bottom: An early mechanical tomato harvester underway. Images from the 1968 USDA Yearbook, Science for Better Living. / THF621133 and THF621134

By 1961, Blackwelder had released a commercial harvester and recommended the VF145 tomato for optimum mechanical harvesting. FMC Corporation released a competing harvester by 1966. Manufacturers touted the labor-saving value of mechanical harvesters at a time when the supply of laborers was too small to meet demand, and the adoption of this new technology was swift. In 1961, 25 mechanical harvesters picked about one-half of one percent of California’s tomato crop. Between 1965 and 1966, the number of harvesters doubled from 250 to 512 and the percentage of mechanically harvested tomatoes in California rocketed from 20 percent to 70 percent. By 1970, the transition was complete, with 99.9 percent of California’s tomato crop harvested mechanically. (For more, see Mark Kramer’s essay, "The Ruination of the Tomato," in the January 1980 issue of The Atlantic.)

Contradictory Impact

Some might claim mechanical harvesters helped save California’s processed tomato industry—by 1980, California growers produced 85 percent of that crop. But a closer look reveals a more complicated cause-and-effect. While growers could theoretically save their crop by replacing some labor with machines, many small-scale growers could not save their businesses from large-scale competition. By 1971, the number of tomato farmers had dropped by 82 percent. (This consolidation was mirrored elsewhere in the industry, as just four companies—Del Monte, Heinz, Campbell, and Libby’s—processed 72 percent of tomatoes by 1980.)

Tomato harvester advertisements promised farmers could save their businesses by replacing scarce laborers with machines, but many small-scale growers could not save themselves from large-scale competitors. Advertisement for FMC Corporation Tomato Harvester, circa 1966. / THF610767

A group of growers sued UC Davis, challenging the school for investing so much to develop the tomato harvester without spending comparable resources to address the needs of small farmers. In response, UC Davis opened its Small Farm Center, an advocacy center for alternative farmers, in 1979. These events coincided with wider efforts to hold the United States Department of Agriculture accountable for unequal distribution of support, resulting in increased attention at the national level to economically disadvantaged and ethnically diverse farmers. Around this same time, food activist Alice Waters raised awareness through her advocacy of locally sourced foods. Her restaurant, Chez Panisse, founded in Berkeley, California, in 1971, became an anchor for the burgeoning Slow Food movement.

So, while mechanical tomato harvesters—like the one on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation—represent large-scale scientific and industrial advances, they also offer insight into this country’s complex labor history and help tell stories about small-scale farmers and their connections to communities, customers, and all of us who eat.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture & the Environment at The Henry Ford. Adapted by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Agriculture and the Environment

- Bringing in the Beans: Harvesting a New Commodity

- Women in Agricultural Work and Research

- As Ye Sow So Shall Ye Reap: The Bickford & Huffman Grain Drill

farming equipment, research, labor relations, Hispanic and Latino history, food, farms and farming, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture

Mechanizing the Tomato Harvest

Machine-harvesting new tomato varieties, as depicted in the 1968 USDA Yearbook, Science for Better Living. / detail, THF621132

For millennia, people have domesticated plants and animals to ensure survival—this process is agriculture. And while most of us neither grow crops nor raise livestock, agriculture affects all our lives, every day: through the clothes we wear, the food we eat, and the fuel we use to move from place to place.

But agriculture is also the changing story of how this work is done. At every step, people have created new technology and tools to challenge nature’s limitations and to reduce the physical labor required to plant, cultivate, and harvest.

People produced much of what they ate until processed foods became big business in the United States during the late 1800s. As market demand increased, and commercial growing and canning grew, it prompted changes in farming. Take the tomato. Canning required ample quantity to guarantee supply, and vast fields of perishable crops required rapid harvest to ensure delivery of the best crop to processors.

Workers harvest tomatoes by hand at a Heinz farm in 1908. / THF252058

But mechanizing the tomato harvest required changing the crop—the tomato itself—so it could tolerate mechanical harvesting. During the 1940s and 1950s, crop scientists cross-pollinated tomatoes to create uniform sizes and shapes that matured at the same time, and with skins thick enough to withstand mechanical picking.

Agricultural engineers developed harvesting machines that combined levers and gears to dislodge tomatoes from the stalk and stem. But humans remained part of the harvesting process. At least eight laborers rode along on the machines and removed debris from the picked fruit.

In 1969, the first successful mechanical harvester picked tomatoes destined for processing as sauce, juice, and stewed tomatoes.

The 1968 United States Department of Agriculture Yearbook, Science for Better Living, depicted new machine-harvestable tomato varieties that “all ripen near same time, come from vine easily, and are firm fruited.” The oblong shape reduced rolling and bruising. / THF621135

Today, all processed tomatoes—the canned products you find on grocery store shelves—make their way from field to table via the levers, gears, and conveyor belts of a mechanical harvester. But you can still buy a hand-picked tomato at your local farmers’ market—or grow your own.

The process of growing food still involves planting and nurturing a seed. But exploring agriculture in all its complexity helps us recognize the many effects of human interference in these natural processes—an ever-changing story that affects all our daily lives.

Adapted by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, from a film in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s Agriculture and the Environment exhibit. The team that wrote and refined the film script included Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture & the Environment; Ryan Jelso, Associate Curator, Digital Content; Ellice Engdahl, Manager, Digital Collections & Content; and Aimee Burpee, Associate Registrar—Special Projects.

Additional Readings:

- Agriculture and the Environment

- Horse Power

- #InnovationNation: Agriculture & Environment

- Biomimicry: Making Mother Nature Our Muse

Henry Ford Museum, farming equipment, food, farms and farming, by Saige Jedele, agriculture

Heritage Apple Trees at Ford Home

William Ford’s farm, depicted in an 1876 county atlas. / THF116253

Farm families in the late 1800s often maintained orchards. Just a couple of apple, pear, plum, or cherry trees could ensure a varied diet and foodstuffs to preserve for winter. And those with land to spare could raise enough excess produce to bring to market.

William Ford, Henry Ford’s father, raised apples for market on his Dearborn, Michigan, farm. The image above, from an 1876 county atlas, shows orchard trees, and the 1880 census of agriculture (collected by the census taker in the summer of 1879) reported 200 apple trees on 4½ acres of the Ford farm—a number that would produce apples well beyond the Ford family’s needs.

Forty years later, apple trees remained part of the landscape at the farmhouse, which was restored by Henry Ford in 1919. Ford’s historical architect, Edward Cutler, drew a map that situated the homestead among outbuildings and trees. It’s difficult to make out, but Cutler identified three varieties of apple trees there—Wagner, Snow, and Greening—that were presumably grown during Henry Ford’s childhood.

At that time, illustrations from horticultural sales books and descriptions in period literature would have helped customers like the Fords determine what fruit tree varieties to buy. An 1885 book on American fruit trees described the Wagner as an early bearer of tender, juicy apples that could be harvested in November and keep until February. A nurseryman’s specimen book itemized the merits of the Snow, “an excellent, productive autumn apple” whose flesh is “remarkably [snow-]white, tender, juicy and with a slight perfume.” And an 1867 book touted the Rhode Island Greening as “a universal favorite” that bears an enormous fruit superior for cooking.

Wagner, Snow, and Rhode Island Greening apple varieties, as illustrated in nurseryman’s specimen books. / THF620189, THF620326, THF620178

When Ford Home was relocated to Greenfield Village in early 1944, Edward Cutler made efforts to represent the surrounding vegetation as Henry Ford remembered it. He included apple trees, though age and condition took their toll on those plantings in the decades that followed. In 2019, The Henry Ford’s staff collaborated with Michigan State University’s Extension Office on a plan to keep the fruit trees of the historic landscapes throughout Greenfield Village healthy. Their strategy involved replacing heritage trees with young stock of the same variety. As part of this project, in April of that year, groundskeepers at The Henry Ford planted new Wagner, Snow, and Rhode Island Greening trees at Ford Home.

Kyle Krueger of The Henry Ford’s Grounds team plants a new Wagner apple tree near Ford Home in Greenfield Village, April 18, 2019. / Photograph by Debra Reid

It will take as many as five years before these new trees bear fruit—as long as weather conditions and the trees’ health allow it—but in the meantime, visitors to Greenfield Village can walk the orchards to check on their progress!

Debra Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content. It originally ran in a spring 2019 issue of The Henry Ford’s employee newsletter.

food, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, farms and farming, Ford family, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

Delicious Destinations: Exploring the Journey from Apple Tree to Table

Wood engraving showing cidermaking, 1854. / THF118316

Since Europeans first introduced apples into the North American colonies, these cultivars (Malus domestica) have been destined for a range of uses. Depending on the variety, apples grown on family farms and in commercial orchards could be eaten on their own (fresh, dried, or cooked), used as an ingredient in sweet or savory preparations, or made into apple sauce or butter; jams or jellies; apple cider (sweet or hard), brandy, or wine; or apple cider vinegar. Below, explore some of the many historical uses of this versatile fruit through selections from The Henry Ford’s Digital Collections and Historic Recipe Bank.

Apples are great for snacking as soon as they ripen, but they also store well. This made apples an important food item to preserve for the winter, when fresh fruit wasn’t available. They could be sliced and dried or packed in barrels whole to keep in a cellar or other cool space. Nurseries advertised apple varieties well-suited for this use. For example, in the early 1900s, Stark Bro's of Missouri claimed its Starking "Double-Red" Delicious apple—the company’s “latest keeper”—remained “firm, crisp, juicy, months longer than Ordinary Delicious.”

Trade card for Stark Bro's Nurseries, Starking "Double-Red" Delicious apple trees, 1914–1940. / THF296714

As a cooked ingredient, apples featured in an array of dishes for every meal of the day—and, of course, dessert. Peeled, cored, and sliced or segmented (tasks made easier with the emergence of mechanical tools such as apple parers by the 19th century), they could be paired with any number of meats, vegetables, or other fruits, or prepared as the star, often in baked goods. The Henry Ford’s holdings include recipes for pork pie (1796), fried sausages (1896), and pork chops (1962) with apples, as well as sweet preparations like apple fritters (1828), apple-butter custard pie (1890), sweet potatoes with apples (1932), and apple crisp (1997).

Trade card depicting apple preparation in a late 1800s kitchen. / THF296481

Apples could be pickled or cooked down and made into sweet jams and jellies, applesauce, or apple butter. Pressed apples yielded sweet juice, which could be fermented into hard cider—an overwhelmingly popular beverage in colonial America and beyond. Byproducts of the cidermaking process included a kind of apple brandy (known as applejack) and cider vinegar, which was an affordable replacement for imported vinegars and could also be served as a drink called switchel. Cider “champagne” and apple wine rounded out the alcoholic beverages made from apples.

To see how the Heinz company processed apples into apple butter and cider vinegar in the early 1900s, check out this expert set.

Streetcar advertising poster for Heinz apple butter, circa 1920. / THF235496

Adding to their amazing versatility, apples could also feed livestock, and wood from apple trees added flavor to smoked meats. Discover some of the many uses of apples firsthand on the working farms of Greenfield Village, and stop into Eagle Tavern to sample hot apple cider, hard cider, or applejack!

Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

“Female Operatives Are Preferred”: Two Stories of Women in Manufacturing

Automatic Pinion Cutter, Used by the Waltham Watch Company, circa 1892 / THF110250

The roles women play in manufacturing are occasionally highlighted, but are often hidden—opposing states that these two stories from our collections demonstrate.

The Waltham Watch Company in Massachusetts was a world-famous example of a highly mechanized manufacturer of quality consumer goods. Specialized labor, new machines, and interchangeable parts combined to produce the company's low-cost, high-grade watches. Waltham mechanics first invented machines to cut pinions (small gears used in watch movements) in the 1860s; the improved version above, on exhibit in Made in America in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, was developed in the 1890s.

This article, “The American Watch Works,” from the July-December 1884 issue of Scientific American, discussed the women workers of the Waltham Watch Company. / THF286663

In the late 19th century, reports on the world-renowned company featured women workers. An 1884 Scientific American article specifically called out women’s work. The article explained that, “For certain kinds of work female operatives are preferred, on account of their greater delicacy and rapidity of manipulation.” Recognizing that gendered experiences—activities that required manual dexterity, such as sewing, or the exacting work of textile production—had prepared women for a range of delicate watchmaking operations, the Waltham company hired them to drill, punch, polish, and finish small watch parts, often using machines like the pinion cutter above. The company publicized equal pay and benefits for all its employees, but women workers were still segregated in many factory facilities and treated differently in the surrounding community.

Burroughs B5000 Core Memory Plane, 1961. / THF170197

The same reasoning that guided women’s work at Waltham in the 19th century led 20th-century manufacturers to call on women to produce an early form of computer memory called core memory. Workers skillfully strung tiny rings of magnetic material on a wire grid under the lens of a microscope to create planes of core memory, like the one shown above from the Burroughs Corporation. (You can learn more about core memory weaving here, and more about the Burroughs Corporation here.) These woven planes would be stacked together in a grid structure to form the main memory of a computer.

However, unlike the women of Waltham, the stories of most core memory weavers—and other women like them in the manufacturing world—are still waiting to be told.

This post was adapted from a stop on our forthcoming “Hidden Stories of Manufacturing” tour of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in the THF Connect app, written by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. To learn more about or download the THF Connect app, click here.

Additional Readings:

- Ingersoll Milling Machine Used at Ford Motor Company Highland Park Plant, 1912

- The China Trade in the 17th and 18th Centuries

- Ford Methods and the Ford Shops

- Thomas Blanchard’s Wood Copying Lathe

20th century, 19th century, Massachusetts, women's history, THF Connect app, technology, manufacturing, Made in America, Henry Ford Museum, computers, by Saige Jedele

Mowtron: The Mower That “Mows While You Doze”

Lawn care takes commitment. Implements designed to reduce the time required to improve a lawn's appearance hit the commercial market during the mid-1800s. Push-powered lawn mowers in a variety of configurations from that era gave way to motorized models, with riding mowers gaining popularity in the 1950s. (For more on the evolution of lawn mowers, check out this expert set.) The American Marketing and Sales Company (AMSC) went one step further in the 1970s. AMSC’s autonomous Mowtron mower, the company proclaimed, “Mows While You Doze.”

Mowtron Mower, 1974. / THF186471

AMSC released the futuristic mower, invented in 1969 by a man named Tyrous Ward, in Georgia in 1971. Its designers retained the familiar form of a riding mower, even incorporating a fiberglass “seat”—though no rider was needed. But Mowtron’s sleek, modern lines and atomic motif symbolized a new day in lawn care.

If the look of the mower promised a future with manicured lawns that required minimal human intervention, Mowtron’s underground guidance system delivered on that promise. Buried copper wire, laid in a predetermined pattern, operated as a closed electrical circuit when linked to an isolation transformer. This transistorized system directed the self-propelled, gasoline-powered mower, which, once started, could mow independently and then return to the garage.

Components of Mowtron’s transistorized guidance system. / THF186481, THF186480, and THF186478

AMSC understood that despite offering the ultimate in convenience, Mowtron would be a tough sell. To help convince skeptical consumers to adopt an unfamiliar technology, the company outfitted Mowtron with safety features, such as sensitized bumpers that stopped the mower when it touched an obstacle, and armed its sales force with explanatory material.

Mowtron’s market expanded from Georgia throughout the early 1970s. The Mowtron equipment and related materials in The Henry Ford’s collection belonged to Hubert Wenzel, who worked as a licensed Mowtron dealer as a side job. Wenzel had two Mowtron systems: he displayed one at lawn and garden shows and installed another as the family mower at his homes in New Jersey and Indiana. Wenzel’s daughter recalled cars stopping on the side of the road to watch whenever it was out mowing the lawn.

Display used by Mowtron dealer Hubert Wenzel. / THF623554, detail

Mowtron sales were never brisk—in fact, Hubert Wenzel never sold a mower—but company records show that the customers willing to try the new technology appreciated Mowtron’s styling, convenience, and potential cost savings. One owner compared her mower to a sleek Italian sports car. Another expressed pleasure at the ease of starting the mower before work and returning home to a fresh-cut yard. And one customer figured his savings in lawn care costs would pay for the machine in two years (Mowtron retailed at around $1,000 in 1974, including installation).

Despite its limited commercial success, the idea behind Mowtron had staying power. Today, manufacturers offer autonomous mowers in new configurations that offer the same promise: lawn care at the push of a button. (Discover one modern-day entrepreneur’s story on our YouTube channel.)

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture & the Environment at The Henry Ford. Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Georgia, 20th century, 1970s, technology, lawn care, home life, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, autonomous technology