Posts Tagged race car drivers

Driven to Win: Showmanship

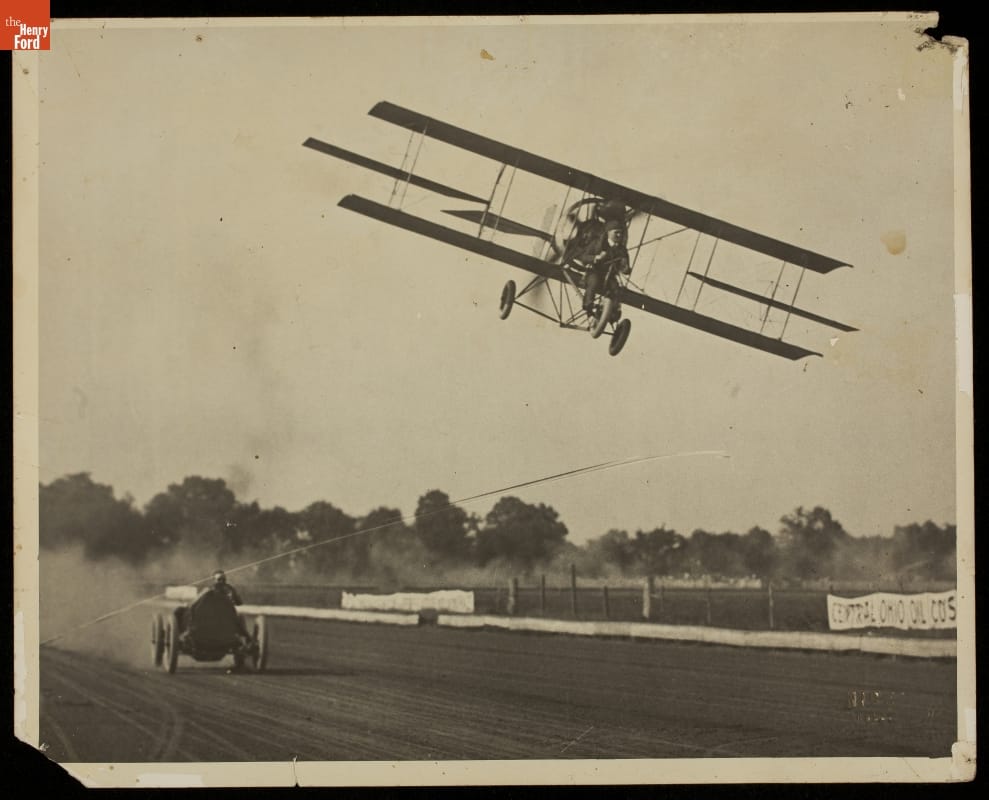

Barney Oldfield and Lincoln Beachey Racing, Columbus, Ohio, 1914 / THF228829

Skilled Showmen

In racing, a skilled driver means everything, but if that person is blessed with charisma and an ability to attract attention, then the fruits of promotion are close at hand. Ability behind the wheel is essential for winning races. But from the sport’s earliest days, success in auto racing also has been augmented by a driver’s ability to attract attention and build a relationship with fans. This helps generate public awareness, fundraising, and sponsorship. In our new racing exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, two exceptional examples—one from the early days of the sport and one from today—are featured, along with their cars.

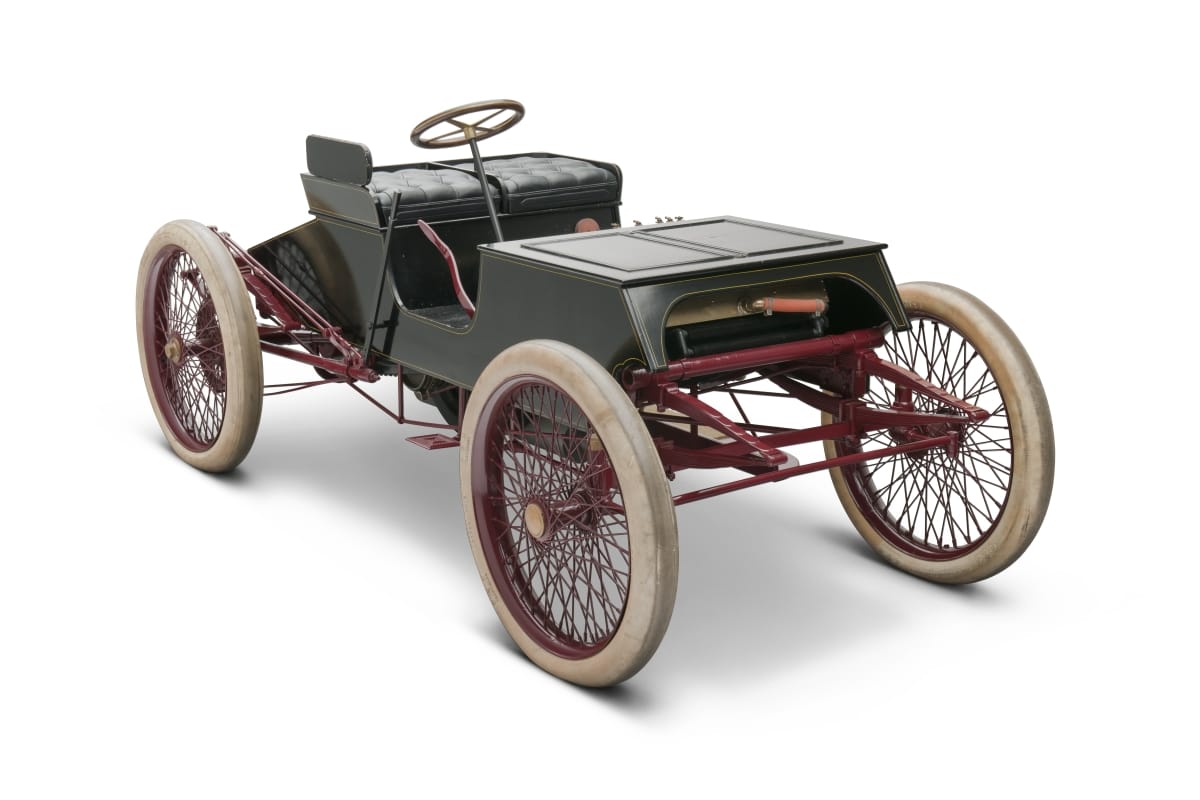

Ford “999,” Driven by Barney Oldfield

THF90218

In the early 1900s, Barney Oldfield made himself larger than life with his widely publicized exploits on racetracks. Oldfield had a reputation as a fearless bicycle racer, and the very first automobile he ever drove was Henry Ford’s “999.” That was about a week before he raced it in the Manufacturers' Challenge Cup on October 25, 1902. Oldfield won handily, which launched his colorful auto racing career. It also produced the first of many opportunities for Henry Ford to promote Oldfield’s exploits to continue building his own reputation on the way to founding Ford Motor Company a year later.

2012 Ford Fiesta ST HFHV, Driven by Ken Block

THF179703

Ken Block has successfully used his charisma, along with his unquestionable car-control skills, to create a name for himself and to build public awareness for his sponsors and their products. Barney Oldfield was largely limited to personal appearances, posters, and newspaper stories and ads to build his brand and those of his backers, but Ken Block has been able to add video, television, the Internet, and social media to his arsenal for attracting attention. His viral “Gymkhana” videos alone have generated hundreds of millions of views around the world. The car you’ll see in Driven to Win was used in “Gymkhana FIVE: Ultimate Urban Playground; San Francisco.”

Additional Artifacts

THF179739

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts related to showmanship in Driven to Win.

- Racing Helmet Worn by Ken Block in "Gymkhana Five," circa 2012

- Sunglasses, Worn by Ken Block, circa 2012

- Driving Shoes Worn by Ken Block in "Gymkhana Five," circa 2012

Dig Deeper

Katherine Stinson with Barney Oldfield at Ascot Speedway, Los Angeles, California, November 29, 1917 / THF129701

Learn more about showmanship in racing with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Learn even more about Barney Oldfield’s life and legacy through artifacts from our collections.

- Take a moment to get to know the “999.”

- Read our press release to learn more about Ken Block’s Ford Fiesta featured in the exhibit.

- Watch our interview with another great racing showman, Mario Andretti.

- Uncover the answers to eight questions with Vaughn Gittin, Jr. in The Henry Ford Magazine.

- See legend Richard Petty and a number of his NASCAR driver colleagues visit Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.

- Discover the story of Dale Earnhardt, Sr.’s breakthrough victory at the 1998 Daytona 500.

popular culture, Henry Ford, race cars, race car drivers, racing, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win

Driven to Win: Indy Car Racing

Festival Queen with the Borg-Warner Trophy at the 52nd Indianapolis 500, May 30, 1968 / Indy50005-68_1096

The Greatest Spectacle in Racing

Say "Indianapolis" and everyone immediately thinks "500." Yes, we’re talking about the greatest spectacle in racing.

The Indianapolis 500-mile race and its venue, Indianapolis Motor Speedway, are the grandparents of American races and race tracks. The 2.5-mile rectangular oval was constructed in 1909 and paved with 3.2 million bricks, which prompted the moniker, “The Brickyard.” A three-foot strip of bricks remains today at the start/finish line. The first Indianapolis 500 ran in 1911, and Ray Harroun won, driving a Marmon Wasp on which Harroun installed a rear-view mirror he had designed—the first ever used on an automobile. His average speed for the 500 miles was 74.602 mph. At present, the fastest 500-mile average speed was set by Tony Kanaan in 2013 at 187.433 mph.

As the 500 grew in importance, it soon became America’s most famous auto race and attracted interest globally. Out of the track’s fame, the name "Indy Car” soon was applied to the open-wheel cars that toured the United States (and much later were included in races in Canada and Mexico), but the Indianapolis 500 always has been the biggest, most important event on the calendar: “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing.”

Our new exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, has an entire section on Indy Car racing, in which you’ll find some key vehicles and other artifacts related to this grand tradition.

1935 Miller-Ford

THF90846

For the 1935 Indy 500, Henry Ford entered a factory team of cars, designed by Harry Miller and powered by modified Ford V-8 engines. This car is one of ten that were built. Miller was the most important American racing designer before World War II. His legacy includes the 4-cylinder Offenhauser engine (for an example, check out the Meskowski-Offenhauser, which you’ll also find in Driven to Win), plus innovation, superb craftsmanship, and artistic touches like the aerodynamic, cast-aluminum suspension arms that could be pieces of sculpture. This car is lower and more streamlined than any other 1935 race car, with four-wheel drive and independent suspension, front and rear—unheard of back then. Unfortunately, the project had insufficient development time, and the car had a flaw that abbreviated testing didn’t reveal until it was too late. The steering box was mounted too close to the exhaust manifold, and eventually the exhaust heat caused the steering to seize up. All the Miller-Ford cars that qualified for the 500 dropped out.

1972 McLaren M16-Offenhauser (crash remnants)

THF137315

This collection of parts is the remnants of one of the most horrific crashes in Indianapolis 500 history. It reminds us that auto racing, while much safer than it used to be, will always be dangerous. In a melee of cars on the front straight at the start of the 1973 Indy 500, this car, driven by David "Salt" Walther, crashed into the outside wall and flipped into the retaining fence. A fuel tank ruptured and the methanol fuel burst into flames. The front of the car ripped off, and videos show Walther's feet dangling outside. He was badly burned, and some spectators also were burned, but there were no fatalities. In spite of his severe injuries, Walther came back to race again in 1974. Safety equipment like a helmet, fire-resistant clothing, a roll bar, and rubber fuel tank liners helped Walther survive, but the crash also triggered some changes to safety rules. Smaller fuel tank capacity reduced the risk of fire, smaller rear wings were mandated to reduce speeds, and the track updated many of its rapid-response procedures.

1984 March 84C-Cosworth

THF90257

Tom Sneva qualified on the pole for the 1984 Indianapolis 500 in this car, with a four-lap average of 210.029 mph. He was the first driver ever to qualify at more than 200 mph. The car is powered by a 159-cubic-inch Ford/Cosworth V-8 engine that produces some 740 horsepower. This car’s design and engineering follow trends that began in the 1970s and are still seen in today’s Indy Cars. The front and rear wings generate aerodynamic downforce to help the car’s tires grip the road. Its cooling radiators are mounted in the side pods, and the bodywork under the pods is shaped to create a low-pressure area that adds more downforce to essentially suck the car down onto the track. The monocoque chassis is made with both aluminum and magnesium. Today’s Indy Cars still have wings and side pods, but the monocoque chassis are now fabricated from carbon fiber.

Additional Artifacts

THF69383

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts related to Indy Car racing in Driven to Win.

- Head and Neck Support Device from Lyn St. James' Race Car

- Commemorative Ring, Awarded to Lyn St. James for Placing in the Starting Grid of the Indianapolis 500, 1992

- Racing Suit Worn by Lyn St. James While Competing at the 1992 Indianapolis 500

- "Rookie of the Year" Trophy, Awarded to Lyn St. James at the 1992 Indianapolis 500

- Racing Glove Worn by Janet Guthrie during the 1977 Indy 500

- Racing Suit Worn by Sarah Fisher While Competing in the Homestead–Miami Indy 300 Race, 2009

- Racing Helmet Worn by Lyn St. James While Competing at the 1992 Indianapolis 500

- Racing Helmet Worn by Rudolf Caracciola, 1939

- Racing Helmet Worn by A. J. Foyt, 1967-1969

- Racing Helmet Worn by Dan Gurney, 1975

Dig Deeper

Ford Thunderbird, Official Pace Car at Indianapolis 500, May 30, 1961 / THF130832

Learn more about Indy Car racing with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Check out our Visionaries on Innovation video interviews with those who have left their mark on the Indy 500—as drivers, behind the scenes, or both: Mario Andretti, Jim Dilamarter, A.J. Foyt, Dan Gurney, Parnelli Jones, Lyn St. James, and Bobby Unser.

- Explore a few of the traditions of the Indianapolis 500 in this blog post.

- See more artifacts related to the Indy 500 from our collections in our expert set.

- Watch the story of Salt Walther’s 1973 crash.

- Dig into the pace car tradition, including the specific story of our 1953 Ford Sunliner pace car.

- Uncover how Scottish drivers have brought their talent across the pond to the Brickyard.

- Learn the story of Jeanetta Holder, who for four decades combined her love of auto racing and her sewing talents to create unique quilts for winners of the Indianapolis 500 and other auto races.

- See how Janet Guthrie broke Indy’s glass ceiling.

- Find out how Lyn St. James became the first woman to win Rookie of the Year at the 1992 Indy 500.

- Discover how Sarah Fisher became the youngest woman, at age 19, to compete in the Indianapolis 500.

- To find tons of additional resources related to some of our most significant Indianapolis 500 vehicles—the 1960 Meskowski Race Car, the 1965 Lotus-Ford Race Car, and the 1988 Rick Mears Winning Indy Car Replica (on loan courtesy General Motors Heritage Center)—check out our blog post on the “In the Winner’s Circle” section of Driven to Win.

Henry Ford Museum, racing, race car drivers, race cars, Indy 500, Driven to Win

New Racing Acquisitions at The Henry Ford

Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors.

The Henry Ford’s newest exhibition, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, opened to the public on March 27. It’s been a thrill to see visitors experiencing and enjoying the show after so many years of planning.

Along with all of that planning, we did some serious collecting as well. Visitors to Driven to Win will see more than 250 artifacts from all eras of American racing. Several of those pieces are newly acquired, specifically for the show.

Shoes worn by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five. Block co-founded DC Shoes in 1994. / THF179739

The most obvious new addition is the 2012 Ford Fiesta driven by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five: Ultimate Urban Playground; San Francisco. The car checked some important boxes for us. It represented one of America’s hottest current motorsport stars, of course, but it also gave us our first rally car. The Fiesta wasn’t just for show—Block drove it in multiple competitions, including the 2012 X Games in Los Angeles, where he took second place (one of five podium finishes Block took in the X Games series). At the same time, we collected several accessories worn by Block, including a helmet, a racing suit, gloves, sunglasses, and a pair of shoes. The footwear is by DC Shoes, the apparel company that Block co-founded with Damon Way in 1994.

Racing toys and games are prominently represented in Driven to Win. We have several vintage slot cars and die cast models, but I was excited to add a 1:64 scale model of Brittany Force’s 2019 Top Fuel car. Force is one of NHRA’s biggest current stars, and an inspiration to a new generation of fans.

Charmingly dated today, Pole Position’s graphics and gameplay were strikingly realistic in 1983. / THF176903

Many of those newer fans have lived their racing dreams through video games. We had a copy of Atari’s pioneering Indy 500 cartridge already, but I was determined to add newer, more influential titles to our holdings. While Indy 500 didn’t share much with its namesake race apart from the general premise of cars competing on an oval track, Atari’s Pole Position brought a new degree of realism to racing video games. Pole Position was a top arcade hit in 1982, and the home version, released the following year, retained the full-color landscapes that made the game so lifelike at the time. I was excited to acquire a copy that not only included the original box, but also a hype sticker reading “Arcade Hit of the Year!”

Another game that made the jump from arcade to living room was Daytona USA, released in 1995 for the short-lived Sega Saturn. Rather than open-wheel racing, Daytona USA based its gameplay on stock car competition. The arcade version was notable for permitting up to eight machines to be linked together, allowing multiple players to compete with one another.

More recently, the Forza series set a new standard for racing video games. The initial title, Forza Motorsport, featured more than 200 cars and encouraged people to customize their vehicles to improve performance or appearance. Online connectivity allowed Forza Motorsport players to compete with others not just in the same room, but around the world.

One of my favorite new acquisitions is a photograph showing a young racer, Basil “Jug” Menard, posing with his race car. There’s something charming in the way young Menard poses with his Ford, a big smile on his face and hands at his hips like a superhero. His car looks worse for the wear, with plenty of dents and an “85” rather hastily stenciled on the door, but this young driver is clearly proud of it. Menard represents the “weekend warrior” who works a regular job during the week, but takes on the world at the local dirt track each weekend.

When we talk about a racer’s tools, we don’t just mean cars and helmets. / THF167207

Drivers may get most of the glory, but they’re only the most visible part of the large team behind any race car. There are folks working for each win everywhere from pit lane to the business office. Engineers are a crucial part of that group, whether they work for the racing team itself, the car manufacturer, or a supplier. In the early 20th century, Leo Goossen was among the most successful racing engineers in the United States. Alongside designer Harry Miller, Goossen developed cars and engines that won the Indianapolis 500 a total of 14 times from 1922 to 1938. We had the great fortune to acquire a set of drafting tools used by Goossen in his work. The donor of those tools grew up with Goossen as his neighbor. As a boy, the donor often talked about cars and racing with Goossen. The engineer passed the tools on to the boy as a gift.

We could not mount a serious exhibit on motorsport without talking about safety. Into the 1970s, auto racing was a frightfully dangerous enterprise. Legendary driver Mario Andretti commented on the risk in the early years of his career during our 2017 interview with him. Andretti recalled that during the drivers’ meeting at the beginning of each season, he’d look around the room and wonder who wouldn’t survive to the end of the year.

Improved helmets went a long way in reducing deaths and injuries. Open-face, hard-shell helmets were common on race tracks by the late 1950s, but it wasn’t until 1968 that driver Dan Gurney introduced the motocross-style full-face helmet to auto racing. Some drivers initially chided Gurney for being overly cautious—but they soon came to appreciate the protection from flying debris. Mr. Gurney kindly donated to us one of the full-face helmets he used in occasional races after his formal retirement from competitive driving in 1970.

And speaking of Dan Gurney, he famously co-drove the Ford Mark IV to victory with A.J. Foyt at Le Mans in 1967. We have a treasure trove of photographs from that race, and of course we have the Mark IV itself, but we recently added something particularly special: the trophy Ford Motor Company received for the victory. To our knowledge, Driven to Win marks the first time this trophy has been on public view in decades. Personally, I think the prize’s long absence is a key part of the story. Ford went to Le Mans to beat Ferrari. After doing so for a second time in 1967, Ford shut down its Le Mans program, having met its goal and made its point. All the racing world had marveled at those back-to-back wins—Ford didn’t need to show off a trophy to prove what it had done!

Janet Guthrie wore this glove at the 1977 Indy 500—when she became the first woman to compete in the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. / THF166385

For most of its history, professional auto racing has been dominated by white men. Women and people of color have fought discrimination and intimidation in the sport for decades. It is important to include those stories in Driven to Win—and in The Henry Ford’s collections. We documented Janet Guthrie’s groundbreaking run at the 1977 Indianapolis 500, when she became the first woman to compete in America’s most celebrated race, with a glove she wore during the event. I quite like the fact that the glove had been framed with a plaque, a gesture that underlined the significance of Guthrie’s achievement. We’ve displayed the glove in the exhibit still inside that frame. More recently, Danica Patrick followed Guthrie’s footsteps at Indy. Patrick also competed for several years in NASCAR, and in 2013 she became the first woman to earn the pole position at the Daytona 500. She kindly donated a pair of gloves that she wore in 2012, her inaugural Cup Series season.

Wendell Scott, the first Black driver to compete full-time in NASCAR’s Cup Series, as photographed at Charlotte Motor Speedway in 1974. / THF147632

Wendell Scott broke NASCAR’s color barrier when he battled discrimination from officials and fans to become the first Black driver to win a Cup Series race. Scott earned the victory at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida, in December 1963. We acquired a photo of Scott taken later in his career, at the 1972 World 600. Scott retired in 1973 after sustaining serious injuries in a crash at Talladega Superspeedway. In addition to acquiring the photo, we were fortunate to be able to borrow a 1966 Ford Galaxie driven by Scott during the 1967 and 1968 NASCAR seasons.

Wendell Scott’s impact on the sport is still felt. Current star Darrell “Bubba” Wallace is the first Black driver since Scott to race in the Cup Series full-time. Following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, Wallace joined other athletes from all sports in supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. He and his teammates at Richard Petty Motorsports created a special Black Lives Matter paint scheme for Wallace’s #43 Chevrolet Camaro, driven at Virginia’s Martinsville Speedway on June 10, 2020. We acquired a model of that car for the exhibit. The interlocked Black and white hands on the hood are a hopeful symbol at a difficult time.

Our collecting efforts did not end when Driven to Win opened. We continue to add important pieces to our holdings—most recently, items used by rising star Armani Williams in his stock car racing career. There will be more to come: more artifacts to collect, more stories to share, and more insights on the people and places that make American racing special.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 20th century, women's history, video games, toys and games, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, engineering, Driven to Win, by Matt Anderson, African American history, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Remembering Bobby Unser (1934-2021)

Bobby Unser, 1963. / THF218272

The Henry Ford mourns the loss of Bobby Unser, who passed away on May 2, 2021. He was a good friend to our organization and, of course, one of America’s most accomplished racing drivers.

Bobby Unser was born into automobile racing. His father and uncles grew up in the shadow of Pikes Peak and competed in the legendary Pikes Peak Hill Climb race. Bobby’s uncle, Louie, earned nine victories in the contest from 1934 to 1953. Bobby’s father, Jerry, finished third as his personal best, but his sons would go on to dominate at Pikes Peak—and Indianapolis.

Bobby Unser was just one year old when his parents, Jerry and Mary, relocated the family from Colorado Springs, Colorado, to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Jerry opened a service station on Route 66—wisely locating it on the west side of town, so his station was the first one motorists saw after traveling across the New Mexico desert. Bobby and his brothers, Jerry Jr., Louis, and Al, grew up working in the station, living and breathing cars. Not surprisingly, they all caught the racing bug. Jerry Jr. and Louis each competed at Pikes Peak for the first time in 1955. Jerry Jr. won his class twice, in 1956 and 1957. He went on to compete in the 1958 Indianapolis 500, but died in a crash during qualifying for Indy the next year. Louis won his class at Pikes Peak in 1960 and 1961, but retired from competitive driving in 1964, when he developed multiple sclerosis. Al earned back-to-back Pikes Peak overall victories in 1964 and 1965. He made his Indy 500 debut in 1965 and went on to become only the second person to win the race four times, taking the checkered flag in 1970, 1971, 1978, and 1987.

Bobby Unser racing up Pikes Peak, 1960. / THF217906

Even in a family of racing legends, Bobby Unser stood out. Following service in the Air Force, he made his own debut at Pikes Peak in 1955. He earned the overall victory there the following year, kicking off an incredible run of nine overall wins in 13 years. Altogether, Bobby Unser claimed 10 overall victories and 13 class wins at Pikes Peak between 1956 and 1986. It’s no wonder they called him “King of the Mountain.”

Bobby followed his older brothers to Indianapolis in 1963. His first years at the Brickyard weren’t promising—crashes took him out early in the 1963 and 1964 races, and during qualifying in 1965—but he earned a top-ten finish in 1966. Two years later, Unser won his first victory at the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. Despite a challenge from Andy Granatelli’s turbine cars, and his own car getting stuck in high gear, Bobby finished nearly a lap ahead of second place finisher Dan Gurney.

Bobby Unser drinks the traditional bottle of milk following his first Indy 500 win, 1968. / THF140423

Unser and Gurney went from competitors to collaborators. Bobby joined Gurney’s All American Racers (AAR) as a driver and competed at Indy under the AAR banner through most of the 1970s. The capstone of their partnership came in 1975 when Unser once again became a reigning Indy 500 champion—or, more properly, a “raining” champion. Mother Nature put on the biggest show at the 1975 race. With 174 of the 200 laps down, the skies let loose with a torrential downpour. Visibility fell to nil, the track flooded, and cars spun left and right. Officials called the race early with Unser in the lead. The race may have been abbreviated, but it was enough to give Bobby his second win.

If Unser’s 1975 win was his most dramatic, then his third Indy 500 win, in 1981, was his most controversial. The final lap saw Bobby cross the finish line five seconds ahead of Mario Andretti. But Andretti and his teammates protested that Unser had passed cars illegally while under a caution flag earlier in the race. After a night of review and deliberation, race officials ruled in Andretti’s favor, penalizing Unser one position and giving Andretti the victory. Unser’s team appealed the ruling and, after months of further investigation, officials reinstated Bobby Unser’s win. The whole affair soured Unser’s love for racing, and he retired from IndyCar competition in 1983.

Bobby Unser in his sportscasting days, 1985. / THF222929

Thirteen wins at Pikes Peak, or three wins at the Indianapolis 500, would be enough to put any driver on a list of all-time greats, but Bobby Unser had more achievements still. He earned USAC national championships in 1968 and 1974, and an IROC championship in 1975. Following his retirement, Bobby worked in broadcasting, providing commentary on auto races for ABC, NBC and ESPN.

From the 1990s on, Bobby Unser was lauded by almost every imaginable racing heritage organization and hall of fame. In 2008, he gifted his personal papers to The Henry Ford, giving us a rich record of his career and accomplishments. He also kindly loaned us the family’s 1956 Ford F-100 pickup and the 1958 Moore/Unser car in which he won Pikes Peak seven times. Both vehicles debuted in our new exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America, presented by General Motors, just weeks ago.

We share the grief of racing fans everywhere at the loss of a true giant. At the same time, we celebrate Bobby Unser’s many achievements on and off the track, and we feel honored to have a role in preserving a significant part of his legacy.

- Hear Bobby Unser describe his career and accomplishments in his own words on our “Visionaries on Innovation” page here.

- Explore the Bobby Unser Papers, in the Benson Ford Research Center, through the finding aid here, and browse digitized photographs and other artifacts from the collection here.

- See highlights from The Henry Ford’s Bobby Unser Collection here.

Bobby Unser, 2009. / THF62889

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Indy 500, Indiana, New Mexico, 21st century, 20th century, racing, race car drivers, in memoriam, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, by Matt Anderson

Driven to Win: Hill Climb Racing

Bobby Unser Crossing the Finish Line, Winner of the 1956 Pikes Peak Auto Hill Climb Race / THF140569

King of the Mountain

What does it take to “race to the clouds”? Power, handling, endurance—and a spirit to conquer the summits of nature. Hill climbs were one of the very earliest forms of automobile competition. They test a car’s power and handling capabilities, and the car-control skills, focus, and endurance of the driver.

Today, there are many local amateur hill climbs, but the most famous one is the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb in Colorado, which has been running since 1916. Its tortuous 12.42-mile course has 156 turns and rises from an elevation of 9,390 feet at the start to 14,115 feet at the finish. For good reason, it’s known as the race to the clouds. Bobby Unser is probably the best-known racer to conquer Pikes Peak. He won the overall event a record ten times—in 1956, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1966, 1968, and 1986—which earned him the title “King of the Mountain.”

1958 Moore/Unser Pikes Peak Hill Climb Car

1958 Moore/Unser Pikes Peak Hill Climb Racing Car. On Loan from Bobby and Lisa Unser. / THF91311

Bobby Unser won seven of his ten Pikes Peak overall victories in this car, including five straight (1959–63), along with 1966 and 1968. In this section of our new racing exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America, presented by General Motors, you can "meet" Unser while he tells you what it took to win all those Pikes Peak races. Learn how he continually improved the car, making it lighter by modifying the frame and suspension and switching to an aluminum radiator, transmission case, and fuel tank.

Additional Artifacts

THF104667

Beyond the Moore/Unser car, you can see these artifacts related to hill climb racing in Driven to Win.

- "Climb to the Clouds" Trophy Won by Harry S. Harkness, 1904

- Cleveland Automobile Club Hill Climb Trophy, 1907

- Algonquin Hill Climb Trophy Won by Frank Kulick Driving a Ford, 1912

- Tire Samples Made with Crushed Walnut Shells for Bobby Unser, 1958

- Racing Harness, 1955-1960

- Duffel Bag, 1963, Used by Bobby Unser

Dig Deeper

Frank Sanborn Driving Chevrolet Stock Car at Pikes Peak Auto Hill Climb, Colorado Springs, Colorado, July 4, 1962 / THF246832

Learn more about hill climb racing with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Watch Bobby Unser talk about his racing history, including Pikes Peak, in our 2009 video interview with the legend.

- See curator-selected photos from our collections highlighting Bobby Unser’s long racing career.

- Browse hundreds of artifacts and photographs related to the Pikes Peak Race to the Clouds in our Digital Collections.

- Discover how we used ingenuity to move the Moore/Unser car (among others) into its new display area in Driven to Win.

cars, race cars, race car drivers, racing, Driven to Win, Henry Ford Museum

Armani Williams: Driving Autism Awareness

Armani Williams. (Photo courtesy Team Armani Racing.)

Grosse Pointe, Michigan, native Armani Williams is at the start of a promising career in auto racing. He competes in multiple professional truck and car racing series, and is honing his skills with an eye toward joining NASCAR’s Camping World Truck Series—one of NASCAR’s three national series and among the highest professional racing series in the United States. This is an impressive goal for any young driver, but especially so for Mr. Williams, who is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.

Autism generally is characterized by difficulty in focusing on and processing multiple stimuli and tasks simultaneously. “Focusing on and processing multiple stimuli and tasks simultaneously” is also a pretty fair description of what a competitive driver does behind the wheel, which makes Williams’s achievements all the more impressive.

Helmet worn by Armani Williams, Scorpion EXO. / THF186734

Like most racing drivers, Armani Williams developed his love for motorsport as a young boy. That passion was fostered by toy cars, televised NASCAR races, and a memorable trip to see NASCAR’s Brickyard 400 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 2010. Eager to get behind the wheel himself, Williams began racing go-karts at age eight. He then advanced to Bandolero racing, a type of motorsport in which young drivers pilot scaled-down versions of stock cars capable of speeds better than 70 miles per hour.

Williams made his competition debut in Automobile Racing Club of America (ARCA) Pro Series pickup truck races in 2016. He set ARCA records by becoming the highest-finishing African American driver in a series race, and by posting the best finish for an African American driver in the ARCA Truck Pro Series championship.

Racing suit worn by Armani Williams, Alpinestars. / THF186736

NASCAR invited Armani Williams to compete in its Drive for Diversity combined tryouts in 2016 and 2017. Established in 2004, the Drive for Diversity program is intended to create a more inclusive culture in NASCAR on the track, in the pits, and in the stands. The program provides training and support to people of color and women pursuing careers as drivers, crew members, sponsors, or team owners.

In 2017, Williams made his debut in the Pinty’s Series, NASCAR’s Canadian stock car racing series. To date, he has earned eighteen wins and two championships in the Pinty’s Series. In 2018, Williams joined the K&N Pro Series East. This American NASCAR series serves as an important development pipeline, building and supplying new talent headed toward NASCAR’s upper levels. Williams earned his first K&N Pro Series top-ten finish at New Hampshire Motor Speedway, where he finished ninth on September 22, 2018. Williams earned another top-ten finish—this time in ARCA’s Menards Series for stock cars—on August 9, 2020, at Michigan International Speedway, his “hometown” track. By competing in the Pinty’s and K&N Pro racing series, Armani Williams became the first driver in any NASCAR series with openly-diagnosed autism.

Race 4 Autism car driven by Armani Williams. (Photo courtesy Team Armani Racing.)

Throughout his growing career, Armani Williams has used his platform in racing to raise autism awareness. He established his Armani Williams Race 4 Autism Foundation in 2015. He also covered one of his race cars with a special Race 4 Autism paint scheme featuring the jigsaw puzzle motif that is widely used as a symbol for autism spectrum disorder.

Racing shoes worn by Armani Williams, Alpinestars. / THF186733

Mr. Williams recently donated pieces of his equipment to The Henry Ford. They include a helmet, a racing suit, and a pair of shoes used by him while racing in the ARCA Truck Pro Series. We are delighted to add these artifacts to the museum’s racing collections, and we look forward to incorporating some of them into our newest exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America Presented by General Motors. We also look forward to following Armani Williams’s competitive driving career. He’s already made history—and he’s just getting started.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

2020s, 2010s, 21st century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Michigan, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars, by Matt Anderson, African American history

The Making of “Fueled by Passion”: Behind the Scenes of Driven to Win

The multisensory theater in Driven to Win at The Henry Ford.

American innovation knows no bounds, and racing, which combines technical excellence with the human endeavor, speaks to our constant need to push the limits of what’s possible. That’s why Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation has gathered one of the finest collections of innovative, powerful, record-busting race cars and automotive artifacts in the world.

Building on this unparalleled collection, The Henry Ford’s newest exhibition, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, gives guests a visceral sense of just how thrilling it is to “go faster and push the limits of racing.” BRC Imagination Arts partnered with The Henry Ford to help bring its incredible collection to life through emotional storytelling, and to get guests excited about “the lives of those who invented their way into the winner's circle and often changed the world in the process.”

The result: Fueled by Passion, the exhilarating, immersive experience at the heart of the new exhibition. The 15-minute sensory-filled experience shares the stories of five people who have empowered themselves to push their personal limits, and ignites the drive we all have to power our passions.

Continue Reading

2010s, 2020s, 21st century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, movies, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Driven to Win: In the Winner’s Circle

Dan Gurney and A. J. Foyt with Victory Champagne at the 24 Heures du Mans (24 Hours of Le Mans) Race, June 1967 / THF127983

Celebration of Success

Whatever the form of racing, every team wants to be in the Winner’s Circle. It’s where victors are crowned and reputations are made. The Winner’s Circle in our new auto racing exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America Presented by General Motors, puts five remarkable race cars on an honorary pedestal. They are connected to some of the greatest drivers, teams, and personalities in racing. They broke records, they broke traditions, and they broke new ground with innovative designs and ideas that influenced all who followed. The Winner’s Circle is a celebration of success.

1956 Chrysler 300-B NASCAR Stock Car

1956 Chrysler 300-B Stock Car / THF107591

This car, and especially its team, brought a fundamental change to NASCAR racing. The team owner, Carl Kiekhaefer (founder of Kiekhaefer Corporation, maker of Mercury outboard boat motors), brought a level of professionalism to his team’s operation that set a new standard in auto racing. His drivers and mechanics all wore matching uniforms, and his cars were immaculately prepared. He transported his cars in closed trucks rather than open trailers (providing more advertising space), and his teams were among the first to practice pit stops. That alone might not have influenced other teams to follow his example, but the clincher was his team’s domination of the series in 1955 and 1956. In 1955, driver Tim Flock scored 18 wins and 32 top-10 finishes on his way to the NASCAR championship. Then, in 1956, Kiekhaefer drivers Buck Baker and Speedy Thompson together won 22 of 41 races, including 16 in a row, with Baker taking the championship. After that season, Kiekhaefer dropped out of racing, but the professionalism he brought soon became the norm.

1960 Meskowski-Offenhauser Indy Roadster

1960 Meskowski Race Car / THF90073

Racing legend A.J. Foyt made the most of this car’s dirt-track prowess. It was key to Foyt winning his first three Indy Car championships in 1960, 1961 and 1963. Race car builder Wally Meskowski engineered and built this car specifically for dirt-track racing, which comprised most of the USAC Championship (Indy Car) series in the early 1960s (the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was one of just three paved tracks in the series in 1960). From 1960 through 1963, Foyt drove this car in 26 races, and scored 13 of his 17 victories in it, all but three of them on dirt tracks. It was powered by the iconic Offenhauser four-cylinder racing engine that dominated Indy Car races from the late 1930s until well into the 1960s. Every Indianapolis 500 from 1947 to 1964 was won with an Offenhauser engine. The engine’s design, with the block and double-overhead-cam cylinder head cast as one unit, produced both the racing essentials: power and reliability.

1965 Lotus-Ford Indy Car

1965 Lotus-Ford Race Car / THF90585

Talk about a disruptor! This car could qualify as the greatest disruptor ever in American racing history. In 1965, Formula One champion Jim Clark drove this car to victory in the Indianapolis 500, marking that race’s first-ever win by a rear-engine car. A few years earlier, legendary road racer Dan Gurney had concluded that a car/engine combination designed using European Formula One technology could revolutionize the 500 and Indy Car racing. He brought Ford Motor Company together with Colin Chapman, the English builder of Lotus Formula One cars. That collaboration resulted in a lightweight Lotus chassis powered by a specially designed Ford V-8 engine. With its monocoque chassis, four-wheel independent suspension, and rear-mounted engine, the Lotus-Ford brought an abrupt end to the traditional Indy front-engine roadster’s long domination and established a new paradigm for American race cars.

1967 Ford Mark IV Sports Car

1967 Ford Mark IV Race Car / THF90744

In the 1960s, Ford Motor Company made the most massive sports car racing effort ever seen in America. The objective was to beat the dominant Ferrari team in the world’s most important sports car endurance race—the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The weapon was a family of cars best known as the Ford GT40. Ford’s first of four straight victories, in 1966, was won by the GT40’s Mark II variant, fielded by the Shelby American team and driven by New Zealanders Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme. The next year, Shelby returned with this car—the more powerful Mark IV. Its chassis was built of an aluminum honeycomb material used in aircraft construction, and the body shape resulted from hours of wind tunnel testing. The big 427-cubic-inch V-8 engine was based on Ford’s stock car racing engine and proved highly reliable. Drivers Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt beat the second-place Ferrari by 32 miles at a record-breaking average speed of 135.48 mph. That win was another first at Le Mans because, unlike the year before, the winning car was built in the United States. This was the first Le Mans win by an American car, built in the United States and driven by Americans.

1988 Chevy-Penske PC-17 Indy Car

1988 Rick Mears Winning Indy Car Replica, on loan courtesy General Motors Heritage Center. / THF185963

In 1988, Rick Mears qualified the original version of this car on the pole and won Penske Racing's seventh Indianapolis 500. The win marked Mears’ third victory at one of motorsports’ most renowned events, and contributed to him becoming one of the most respected drivers in Indy car racing history. That year, all three Penske team drivers—Mears, Danny Sullivan, and Al Unser, Sr.—piloted the new PC-17 chassis powered by redesigned Chevrolet engines. The Penske team swept the top three qualifying positions on pole day. Mears’ four-lap qualifying speed of 219.198 mph became the new Speedway standard, and the Penske team, led by Mears’ win, took two of the top three podium positions (Unser placed third).

Additional Artifacts

THF151454

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts in the Winner’s Circle in Driven to Win.

- Coveralls Worn by Team Lotus Mechanic Graham Clode, 1965

- NASCAR Grand National Racing Trophy Won by Buck Baker, 1956

- Pit Board for NASCAR Team Kiekhaefer's Chrysler 300-B, circa 1956

- "Indy 500" Lanyard, 2020

- "Indy 500" Patch, 2020

- "Indianapolis 500" Pin, 2020

- Program, "Official Program: 97th Running Indianapolis 500," 2013

- Set of "Pracision" Drafting Tools, Used by Leo Goossen, 1925-1941

- Stetson Cowboy Hat Signed by Carroll Shelby, 2009

- 24 Hours of Le Mans Trophy, 1967

- 24 Hours of Le Mans Trophy, 1967

Dig Deeper

Jim Clark after Winning the 1965 Indianapolis 500 Race / THF110641

Learn more about these winning stories with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Read about the Chrysler 300-B’s spin around Motor Muster in Greenfield Village in 2018.

- Learn the story of Vicki Wood, who drove at least one Kiekhafer Chrysler.

- Watch A.J. Foyt share his thoughts on Indy, Le Mans, and the many drivers and cars he raced in his long career.

- What if a single car could change the greatest spectacle in racing? Find out in our What If story about the Lotus-Ford.

- Learn about Jim Clark’s 1965 Indy 500 win in the Lotus-Ford Type 38.

- Explore photos and other artifacts related to Jim Clark’s 1965 Indy win.

- Go even deeper into the story of the Lotus-Ford and Jim Clark’s historic win.

- Watch this video outlining the Lotus-Ford’s story.

- Read Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson’s account of the Lotus-Ford’s return to Indianapolis in 2015.

- Watch clips from practice, qualifying, and the race at the Indianapolis 500 in 1965.

- See the Lotus-Ford on its international trip to Goodwood Revival in 2013.

- See Dan Gurney bring the romance of his racing career to life in this video interview with The Henry Ford.

- Join us in paying tribute to Edison-Ford Medal winner Dan Gurney in this video and blog post.

- Join Mo Rocca and The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation to explore the story of Ford vs. Ferrari at the 1967 Le Mans.

- Watch our own volunteer Mose Nowland share his first-hand memories of the Ford-Ferrari battles of the 1960s.

- Watch the legend of Le Mans—the 1967 Ford Mark IV.

- Learn how we’ve cared for and preserved the Mark IV.

- See curator-selected historic photographs documenting Ford’s run at Le Mans in 1967.

Indy 500, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars

Auto Racing Virtual Meeting Backgrounds: Featuring Driven to Win

Looking to add some adrenaline to your next virtual meeting? Try the new backgrounds below, taken from Driven to Win: Racing in America, presented by General Motors. These images feature some of the exhibition’s iconic race cars, including the 1965 Goldenrod and the 1967 Ford Mark IV.

If you want even more background options, you can download any of the images of our artifacts from our Digital Collections. Our racing-related Digital Collections include more than 37,000 racing photographs, 400 three-dimensional artifacts (including race cars!), and nearly 300 programs, sketches, clippings, and other documents. Beyond racing, this collection of backgrounds showcases some views from Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, Greenfield Village, and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour.

These links will give you instructions to set any of these images as your background on Zoom or Microsoft Teams.

Continue Reading

race car drivers, African American history, Mark IV, photographs, Driven to Win, Henry Ford Museum, cars, by Bruce Wilson, by Ellice Engdahl, by Matt Anderson, race cars, racing, technology, COVID 19 impact

Driven to Win: Dawn of Racing

Lorraine-Detrich Automobile Driven by Arthur Duray at the Vanderbilt Cup Race, Long Island, New York, 1906 / THF203486

Early American Racing: A Compulsion to Prove Superiority

The quest for automotive superiority began on the track. Innovation proved to be king—it is the fuel that built reputations, generated interest and investment, and paved the way to newfound glory.

Near the end of the 19th century, the infant auto industry was bursting at the seams with ideas, experiments, and innovations. The automobile was new and primarily a novelty—as soon as there were two cars on the road, their builders and drivers were compelled to race each other. Being competitive: It’s just human nature. Which was the best car, the best driver?

Automobile races soon became a proving ground, where carmakers could showcase their design and engineering prowess. Winning built reputations, generated interest and attracted investment.

The “Dawn of Racing” section of our new exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America, immerses you in an exploration of the early days of racing, using period settings, images, and authentic artifacts. It features two of America’s most significant early race cars.

1901 Ford "Sweepstakes" Race Car

THF90167

Henry Ford only ever drove one race, on October 10, 1901, and that was in the car they called “Sweepstakes.” He certainly was the underdog, but against all odds he won. In Driven to Win, you will discover the innovations that Ford developed for “Sweepstakes” that helped him achieve that remarkable victory. It gave a powerful boost to his reputation, brought in financial backing that helped launch Ford Motor Company, and a few years later, Ford Motor Company put America—and much of the world—on wheels with the Model T.

1906 Locomobile "Old 16" Race Car

THF90188

Driving “Old 16” in the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup race, George Robertson scored the first victory by an American car in a major international auto race in the United States. At that time, the Vanderbilt Cup race was world-famous and highly prestigious, and “Old 16” became known as “the greatest American racing car.” In Driven to Win, you will learn about and see firsthand the expertise, craftsmanship and attention to detail that made this car a winner.

Additional Artifacts

THF154549

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts related to early racing in Driven to Win.

- Drop Box Used during the 1904 Vanderbilt Cup Race

- Automobile Racing Goggles, Used by Joe Tracy, circa 1905

- Early Automobile Racing Gloves, circa 1905, Owned by Joe Tracy

- Automobile Racing Face Mask, circa 1905, Owned by Joe Tracy

- Helmet Used by George Robertson in 1908 Vanderbilt Cup Race

- Paperweight Commemorating the 1908 Victory of the Locomobile Company at the Vanderbilt Cup Races

Dig Deeper

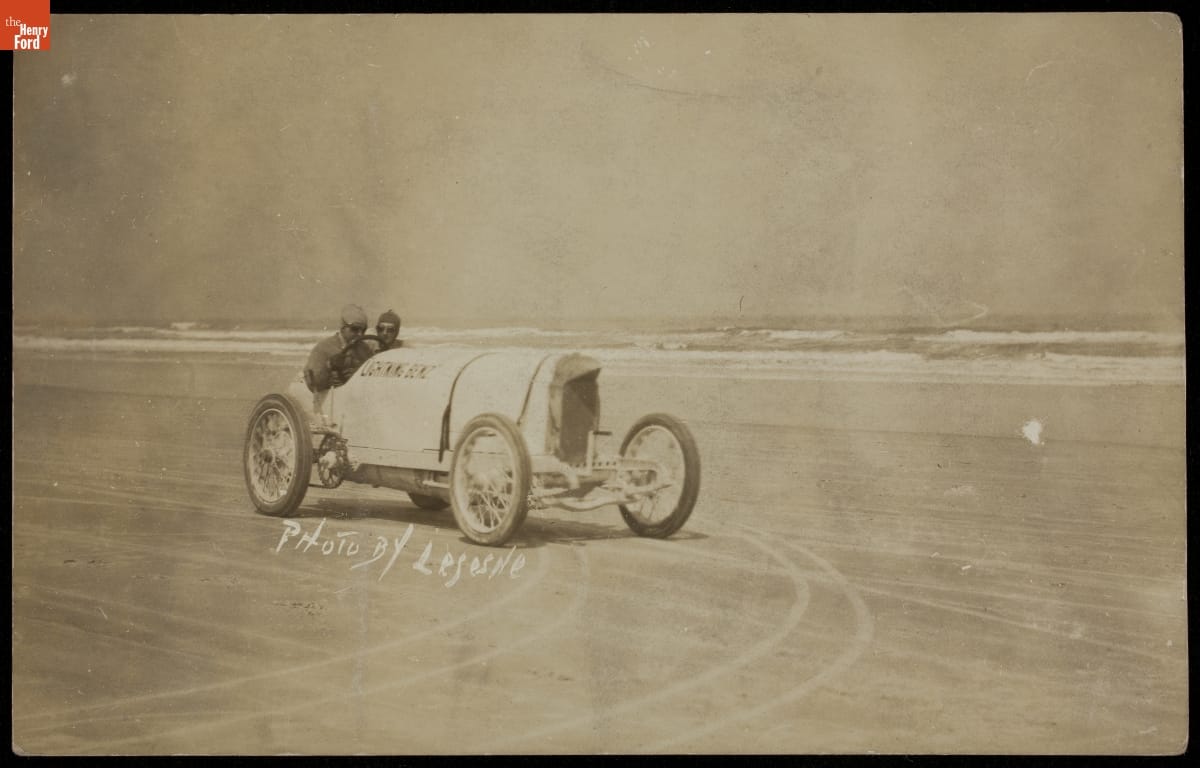

Barney Oldfield in "Lightning Benz," Daytona Beach, Florida, March 16, 1910 / THF228867

Learn more about early racing with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Discover the story of racer Barney Oldfield, one of America’s earliest celebrity sports figures.

- Watch our Sweepstakes replica run in Greenfield Village.

- Explore the world of board track racing.

- Learn how Ford Motor Company recognized Henry Ford’s 150th birthday with a custom-painted race car honoring Henry’s win in the Sweepstakes.

20th century, 1900s, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars