The History of Historic Base Ball in Greenfield Village

In 1993, inspired by a handful of century-old newspaper references, nine employees volunteered to form The Henry Ford’s first historic base ball club. What started small has become a grand and beloved Greenfield Village tradition, guided—as it was from the beginning—by a passion for authenticity.

The Greenfield Village Lah-De-Dahs and the general store that spurred the club’s formation, 1994. / THF136301

Beginnings

It all began with Greenfield Village’s general store. New research in the 1990s initiated a more accurate historical interpretation of the J.R. Jones General Store as it existed in Waterford, Michigan, during the 1880s. It also turned up references to a local amateur base ball club—the Lah-De-Dahs—in period newspapers. Employees eagerly set about reviving the Lah-De-Dahs as a historic base ball club. A clue about the original uniform came from a colorful report on the Lah-De-Dahs’ poor showing in a summer 1887 game:

As the contest went on, slowly but surely dawned upon the minds of all the truth that a fine uniform does not constitute a fine pitcher, nor La-de-dahs in their mammas’ red stockings make swift, unerring fielders. —Pontiac Bill Poster, September 14, 1887

The revived Lah-De-Dahs of Greenfield Village wore white base ball shirts with a red script “L” and, at first, nondescript white painter’s pants. (The Henry Ford’s period clothing studio soon produced matching, knickers-style bottoms.) That first season, the Lah-De-Dahs played a handful of matches with rules pieced together from various historical interpretations. At Firestone Farm, the club challenged farmhands in the harvested wheat field before whatever crowd gathered along the lane. The Lah-De-Dahs also hosted a few outside historic base ball clubs at their future home field, Walnut Grove.

Structure

Historic base ball in Greenfield Village quickly assumed a more structured form that incorporated thoughtful details rooted in history—beginning with the name of the sport itself. Virtually all of the earliest references to this style of bat-and-ball game in England and the United States used the hyphenated name, “base-ball.” By the late 1830s and into the 1840s, likely due to simple changes in typesetting practices, the two-word spelling, "base ball," had begun to replace "base-ball." Conventions continued to shift, with the hyphenated version reemerging in the mid-late 19th century and receiving formal backing from the U.S. Government Printing Office in 1896. But years earlier, in 1884, the New York Times had explicitly changed its style guide away from "base-ball" to "baseball"—an early move toward the one-word convention that would stick. To highlight overlapping customs in the sport’s formative decades, The Henry Ford emphasizes the two-word spelling in its historic base ball program.

Henry Chadwick’s 1867 Base Ball Player's Book of Reference, the first reference book designed to teach the game of base ball, from which the current rules of play in Greenfield Village were drawn. / THF214794

For demonstration in Greenfield Village outside of Lah-De-Dahs matches, a set of rules, known as “Town Ball” or “Massachusetts Rules,” was selected from the 1860 Beadle’s Dime Base Ball Player. Written by Henry Chadwick, a sports journalist and leading promoter of base ball, this book included early rules of the game we know today, as well as the alternative “Massachusetts Rules” version of the game. This early version of baseball requires minimal equipment, calls for a soft ball, and features chaotic rules, making it a perfect choice for guests of Greenfield Village to try.

Elements added for the comfort and enjoyment of spectators on Walnut Grove appropriately reflect the 1860s setting. On select dates, the Dodworth Saxhorn Band provides musical accompaniment representing that of a period brass band. (Much of the music commonly associated with the professional game of baseball in America—including its unofficial anthem, “Take Me Out to the Ball Game”—was published two generations later.) Refreshments are served from contextual, temporary structures fitting the rural environments where 1860s base ball was played. And a uniquely designed sound system—disguised by several strategically placed waste receptacles—allows the umpire and scorekeeper to present a real-time account of the game via concealed cordless microphones. The live music and play-by-play, combined with the unpredictability of the game, make for an entertaining afternoon.

The Dodworth Saxhorn Band during the World Tournament of Historic Base Ball, 2007, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF52297

Expansion

The Lah-De-Dahs’ roster grew to 25 players over the club’s second and third seasons. They wore handmade uniforms for matches, which were held whenever visiting clubs could make the trip to Greenfield Village. By 2002, the season consisted of a dozen games played on select Saturdays throughout the summer. After nearly a decade of play, the Lah-De-Dahs had attracted a dedicated fan base, and spectators increasingly requested a regular schedule with more games.

The reopening of Greenfield Village in 2003 after a massive restoration project heightened expectations for the historic base ball program. With financial support from Edsel and Cynthia Ford, The Henry Ford delivered an entire summer of base ball with expanded offerings: daily period base ball demonstrations, formal games on Saturdays and Sundays—now played by the “New York rules” specified in Henry Chadwick’s 1867 Base Ball Player's Book of Reference (which were more familiar to spectators than the Massachusetts Rules game)—and the development of the World Tournament of Historic Base Ball.

The Henry Ford’s World Tournament of Historic Base Ball pays homage to the original “World's Tournament of Base Ball” hosted in August 1867 by the Detroit Base Ball Club. Though organizers ultimately failed to attract the world-famous clubs of the day, they managed to stage a remarkable, one-of-a-kind event. The trophy bat awarded to the Unknown Base Ball Club of Jackson, Michigan—winners of the first-class division of the 1867 tournament—is now in The Henry Ford’s collections. It is displayed each year in Greenfield Village during the World Tournament of Historic Base Ball.

Trophy bat awarded at the 1867 World's Tournament of Base Ball. / THF8654

For 2004, the Lah-De-Dahs’ season expanded from 12 to 30 games, and its roster swelled to 42 players. To make sure they always had an opponent, The Henry Ford created a second club. The National Base Ball Club takes its name from a competitor in the 1867 World's Tournament of Base Ball. New uniforms purchased for both clubs added to the already vibrant atmosphere during matches, with the Lah-De-Dahs in their now-familiar red and white and the Nationals in striking dark blue and gold. At first, many considered the Lah-De-Dahs to be Greenfield Village’s “home” club, but displays of sportsmanship and close games going to either side have endeared fans to both.

One of the close plays that have helped endear fans to both Greenfield Village clubs.

Over time, baseball became “America’s pastime,” an enduring cultural touchstone—and a multibillion-dollar business. Historic Base Ball in Greenfield Village (and also played in many other venues around the country) showcases an early form of the sport, from a time when amateurs played for recreation and innocent amusement—for the love of the game!

Brian James Egen is Executive Producer and Head of Studio Productions at The Henry Ford and Marcus W. Dickson is Professor of Industrial/Organizational Psychology at Wayne State University. This post was prepared for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

research, Historic Base Ball, by Saige Jedele, by Marcus Dickson, by Brian James Egen, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Greenfield Village, events, sports, baseball

Quiet & Loud Protest

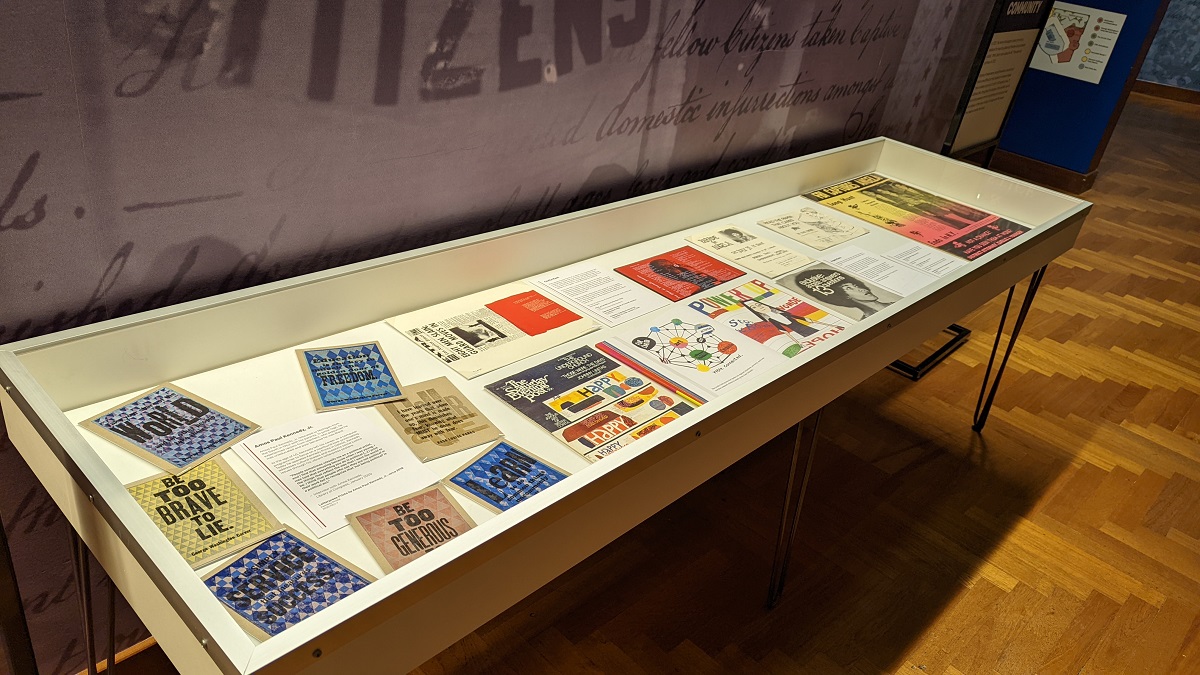

Photo by Curatorial Staff of The Henry Ford

When you think of the word “protest,” what does it mean to you?

- Marching at a rally with a sign?

- Participating in a “walk out” at school?

- Boycotting companies?

- Wearing a shirt or hat with a message?

- Correcting people on their biases?

- Donating money to organizations?

- Civil disobedience?

A new temporary exhibit now on view in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, Quiet & Loud Protest, explores this question by demonstrating the ways that protest can be both loud and quiet. Throughout history, people have found different ways to advocate for change, whether marching in the streets or finding quieter ways to be an ally. Both are valuable in drawing attention to injustices. The exhibit draws together a small selection of recent acquisitions that showcase how artist-activists have used graphics to demand change and organize communities. The content of the exhibition is replicated in this post (with slightly expanded descriptions) for those unable to see it in person.

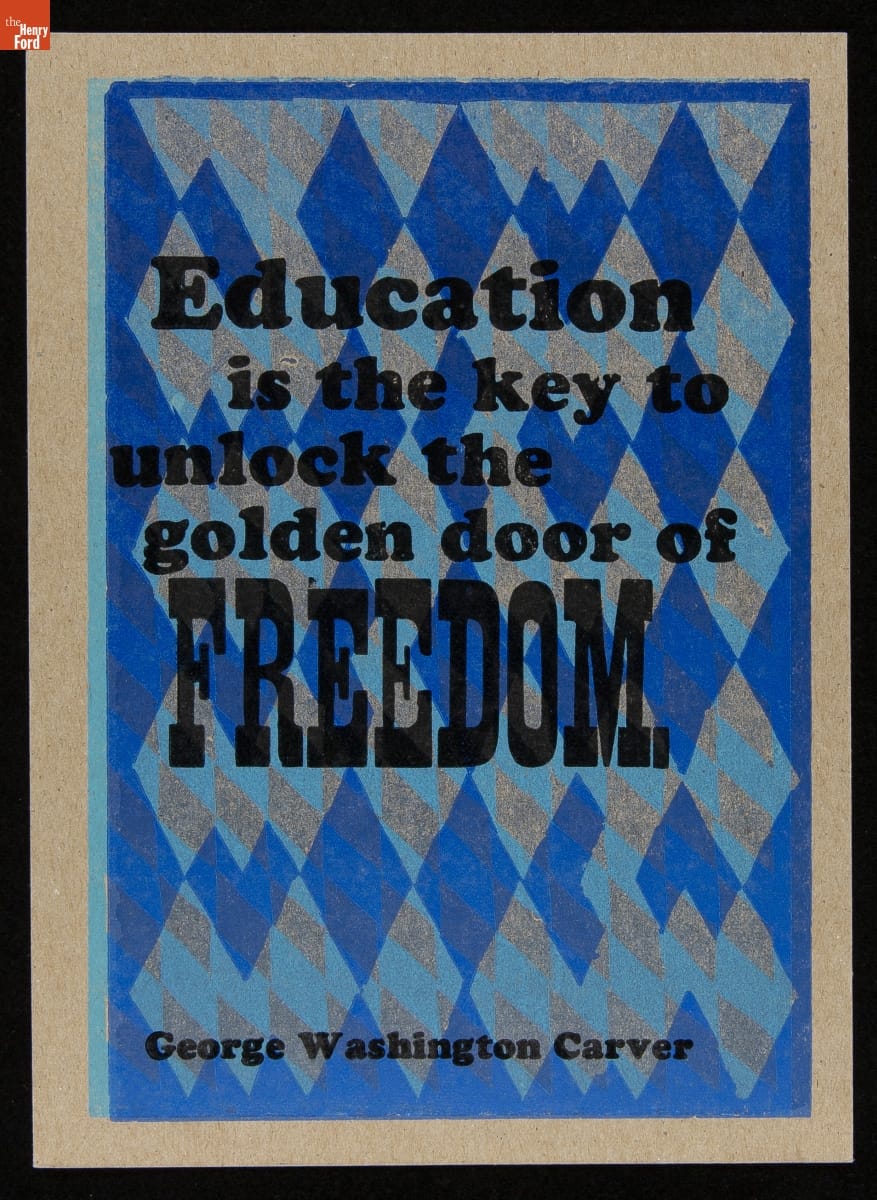

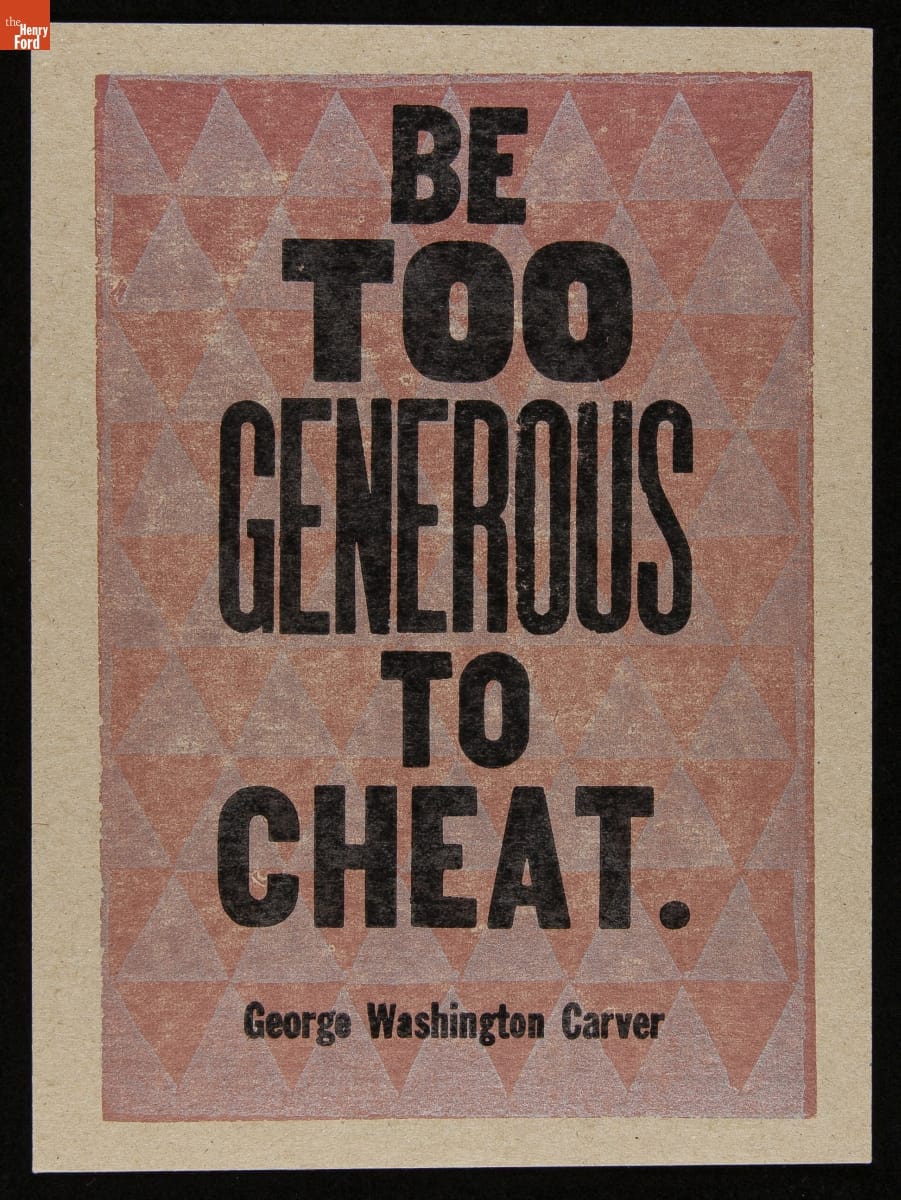

Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr.

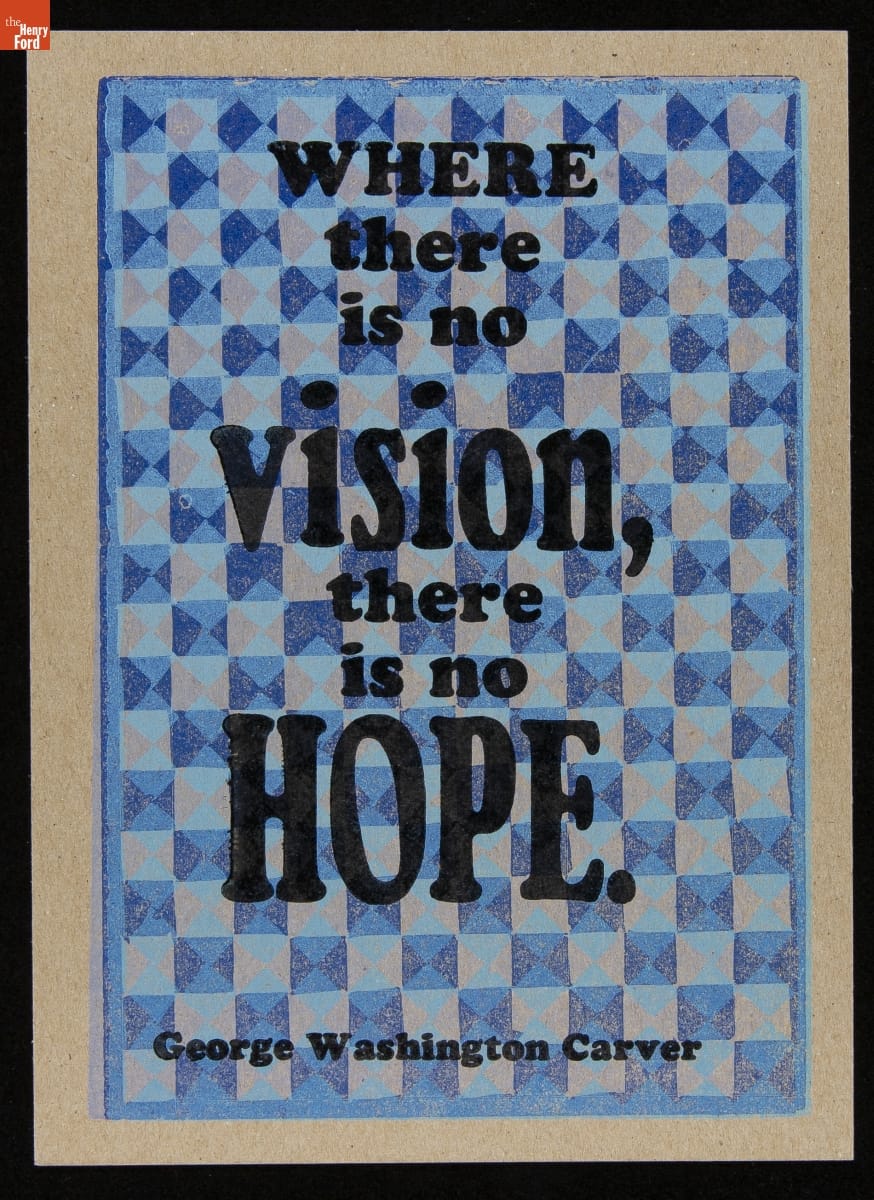

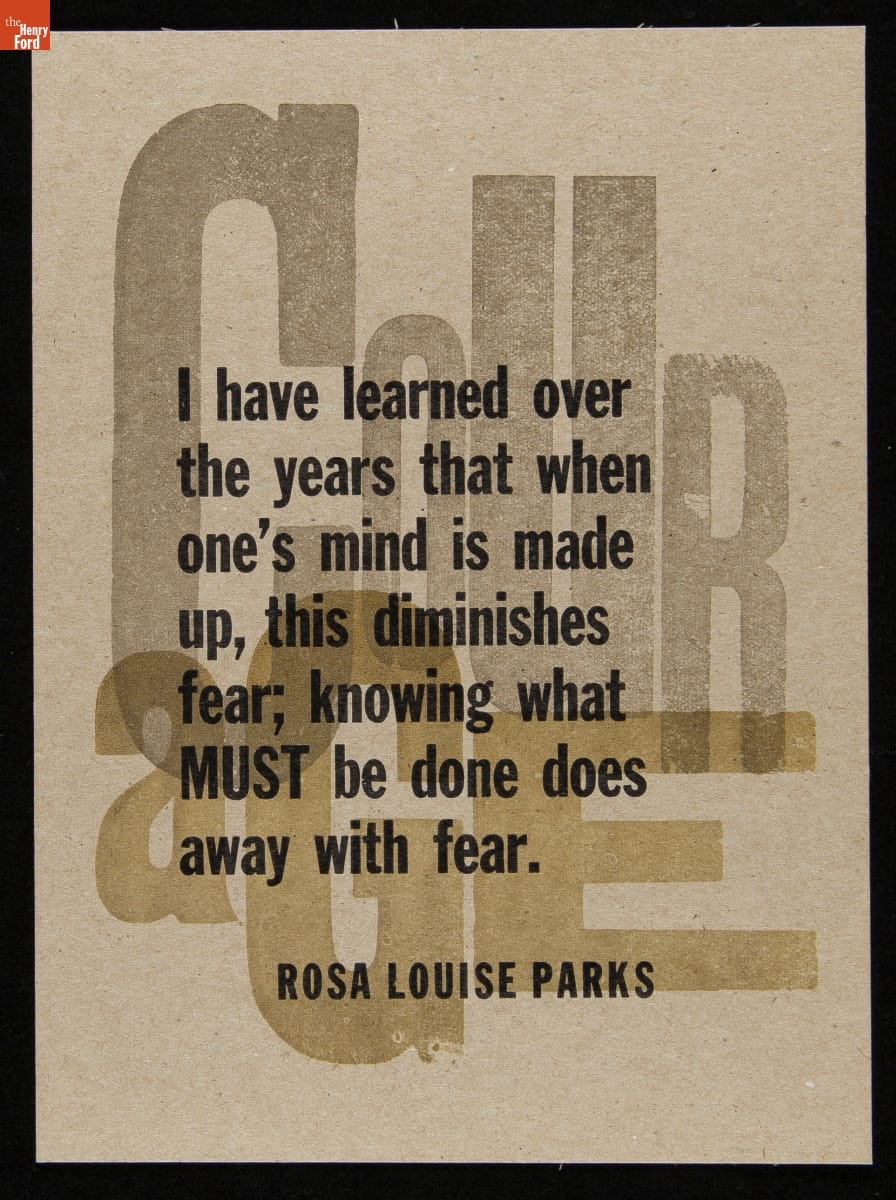

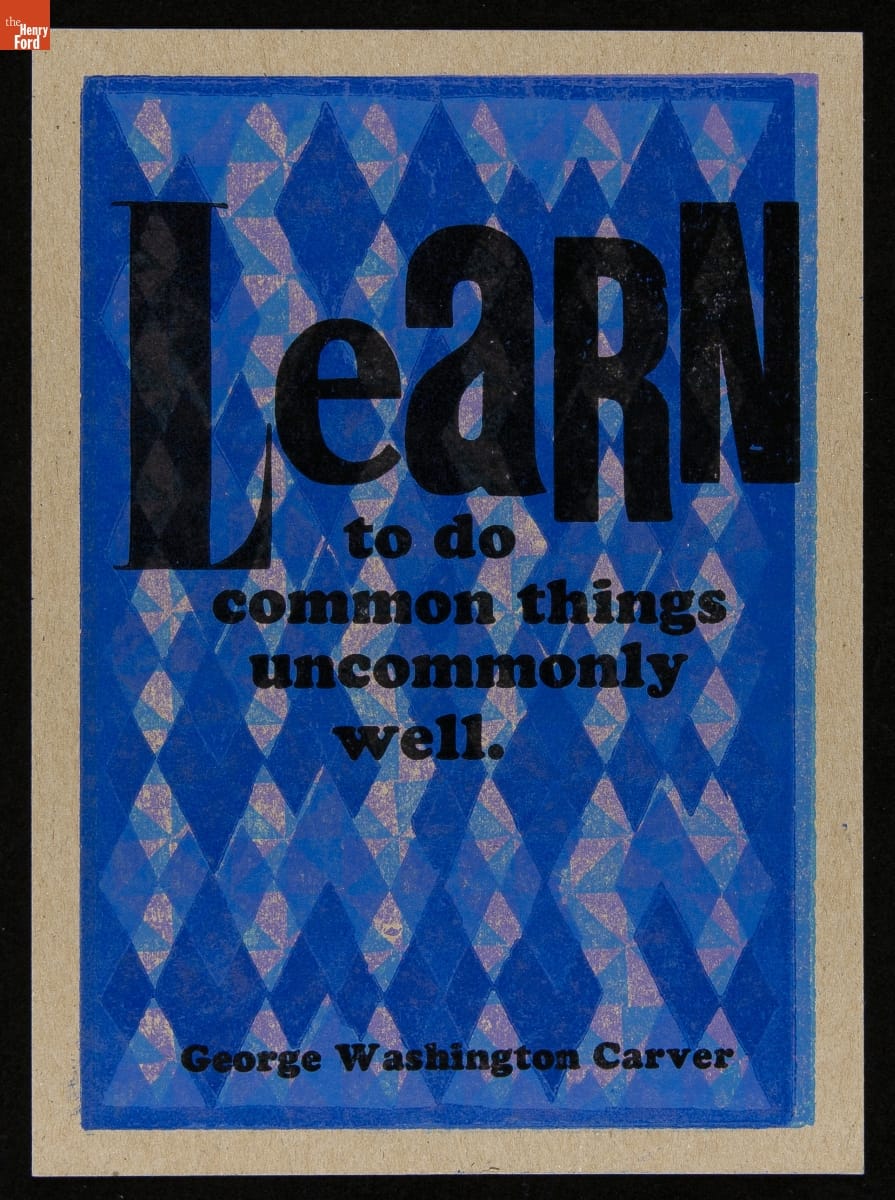

Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. has generously donated several prints to the collections of The Henry Ford. These examples feature quotes attributed to George Washington Carver and Rosa Parks—two advocates for change who are prominent in our collections. / THF626953 (top), THF626939 (bottom)

These letterpress prints are by Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr., who relocated to Michigan from the South in 1963 with his parents. In junior high, he experienced racism from teachers who presumed he was uneducated and poor because he was Black.

At the age of 40, Kennedy visited Colonial Williamsburg while on vacation with his family and was so enamored with the letterpress and bookbinding demonstrations being given by historical reenactors that he went home and began to take classes at a community print shop. His love for the medium grew to the point where he made the decision to leave his career as a corporate computer programmer at AT&T so that he could focus on printmaking full time.

Letterpress prints by Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr./ THF626947 (top), THF626949 (bottom)

He went on to earn an MFA in Fine Arts and taught in university art programs. When Kennedy left academia, he adopted the historical role of an iterant printer, travelling through the American South to different print shops, learning about print media and developing his style over the course of many years. Kennedy sometimes describes himself as a “humble Negro printer” and wears bib overalls with a pink dress shirt. By doing this, Kennedy confronts people with their biases, causing them to question race, language use, and class. In 2013, Kennedy moved to Detroit, where he operates Kennedy Prints today.

Letterpress prints by Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr. / THF626943 (top), THF626941 (bottom)

Kennedy is known for his prolific output of vibrant letterpress prints that address cultural biases and social justice issues. Many of his prints feature quotes by Black civil rights activists and abolitionists, scientists and innovators, and literary figures, as well as traditional African proverbs. In an interview with the Library of Congress in January 2020, Kennedy said:

“People sometimes classify me as a political artist, and I find that amusing because when I was young, I was told that everything you do is political […] I print the things that reflect the way that I want the world to be. I think that people who say they are not political in their work fail to recognize that ‘not being political’ is a political act.”

Kennedy refuses to call himself an artist and sells his work at affordable prices to make it more accessible. Thanks to the power of the multiple, Kennedy can use printmaking to spread messages of hope widely—to reflect exactly the type of world that he wants to live in.

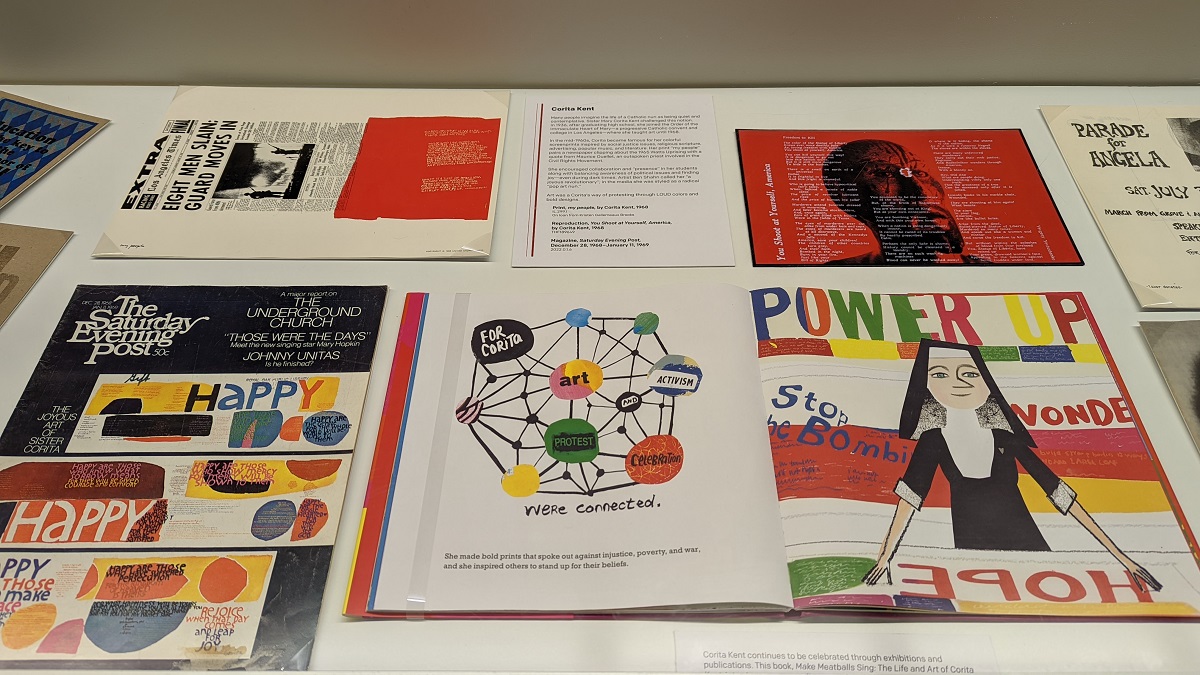

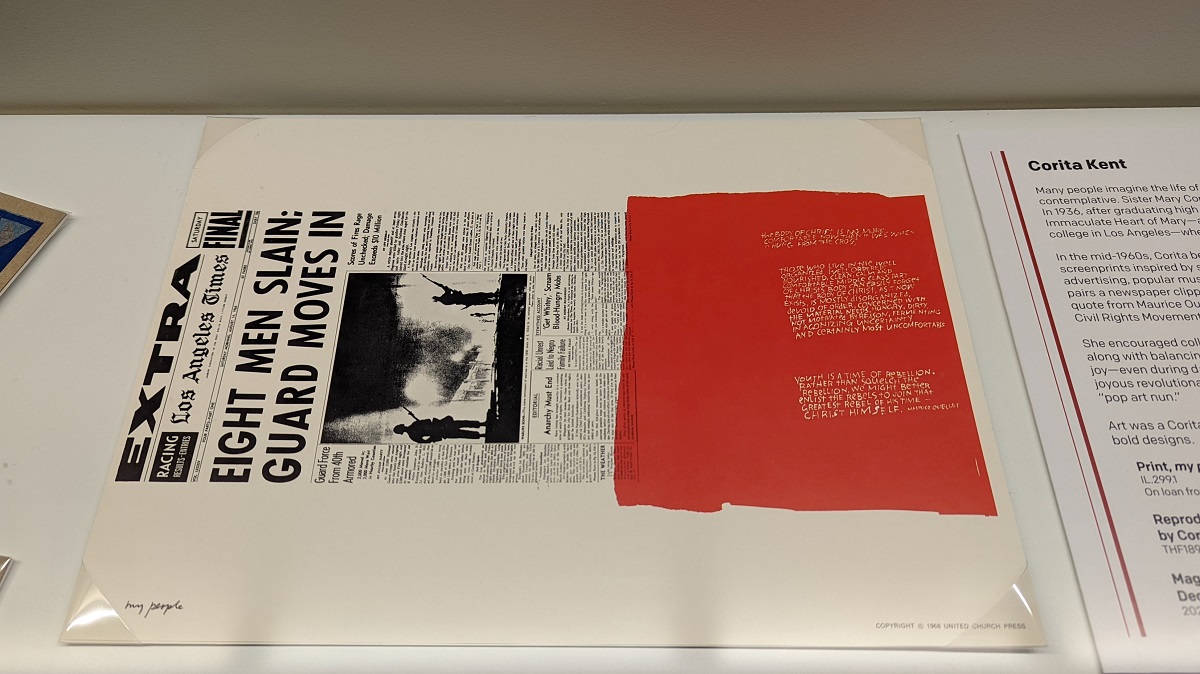

Corita Kent

Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux

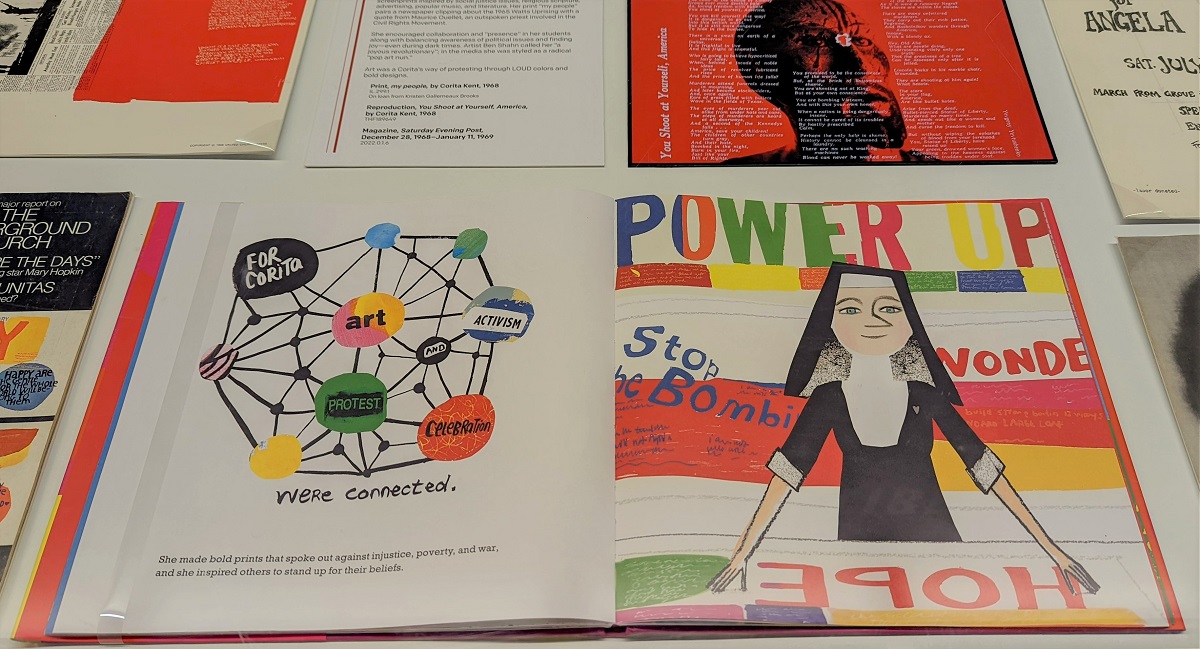

Many people imagine the life of a Catholic nun as quiet and contemplative. Sister Mary Corita Kent challenged this notion. In 1936, after graduating high school, she joined the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary—a progressive Catholic convent and college in Los Angeles—where she taught art until 1968.

In the mid-1960s, Corita became famous for her colorful screenprints inspired by social justice issues, religious scripture, advertising, popular music, and literature. Her most celebrated prints are text-heavy and vibrant, layering blocks of bright color and DayGlo ink with high-key photographic imagery and words that twist around the page.

Detail of Quiet & Loud Protest exhibit with Corita Kent’s “my people” print. / Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux

Her print “my people” pairs a newspaper clipping about the 1965 Watts Uprising with a quote from Maurice Ouellet, an outspoken priest involved in the Civil Rights Movement in Selma, Alabama. Part of the quote Corita included reads: “Youth is a time of rebellion. Rather than squelch the rebellion, we might better enlist the rebels to join that greatest rebel of his time—Christ himself.” And in an oral history, Corita herself said: “I feel that the time for physically tearing things down is over. It’s over because as we stand and listen, we can hear it crumbling from within.”

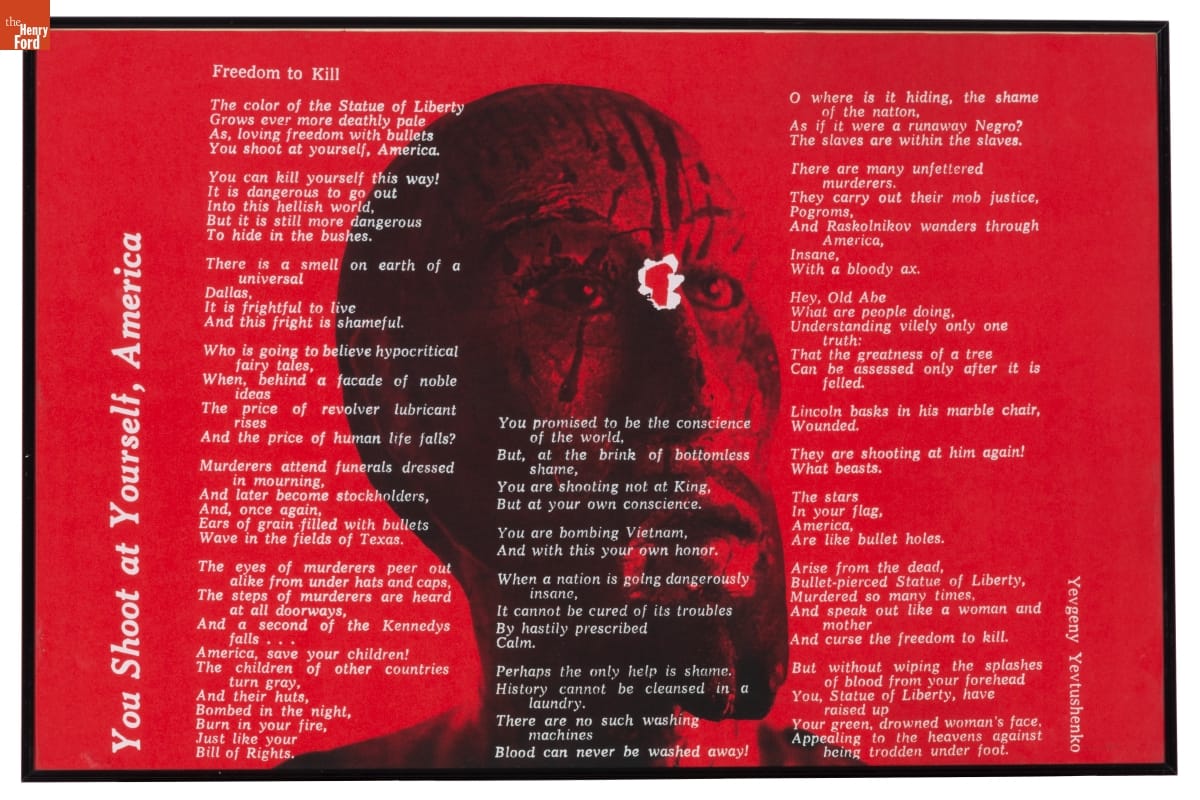

Corita Kent’s print “You Shoot at Yourself, America” was created in response to the 1968 assassination of Robert F. Kennedy. It features a poem by Yevgeny Aleksandrovich. / THF189649

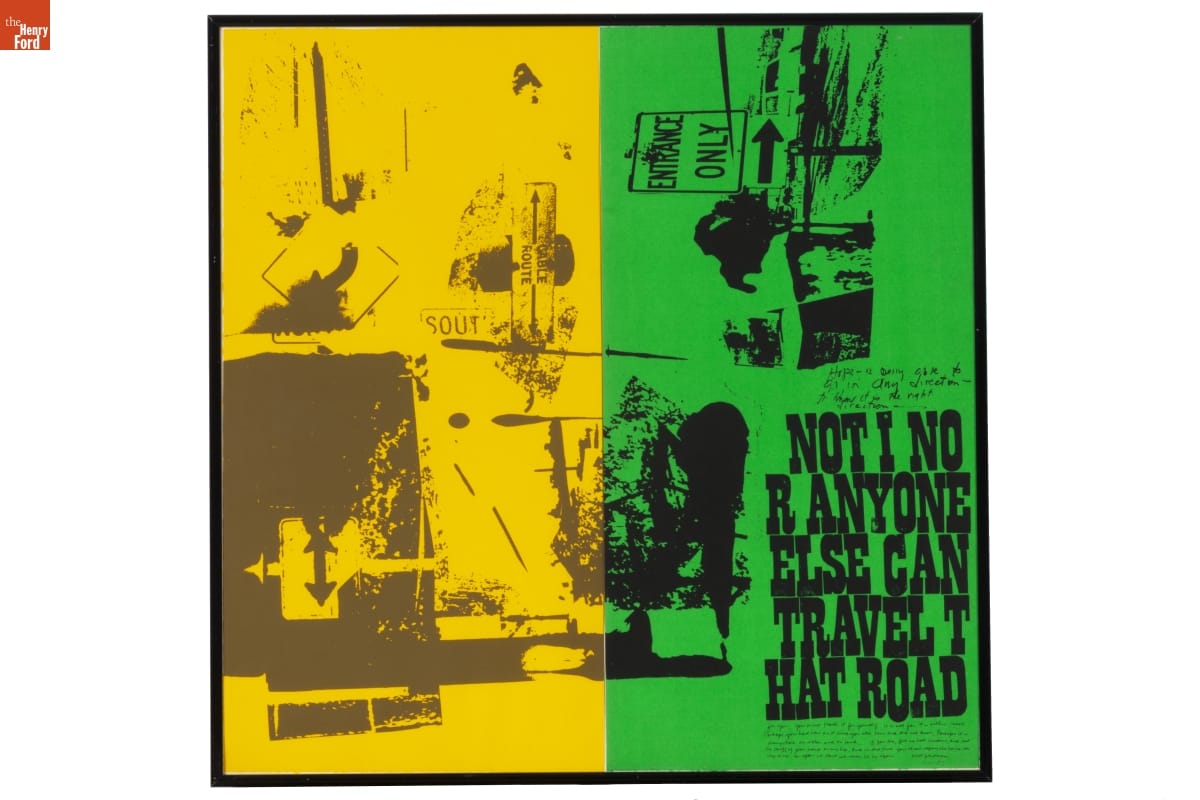

Corita Kent’s print “Road Signs (Part 1 & 2)” features text excerpted from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. / THF189650

Corita encouraged collaboration and “presence” among her students and encouraged them to balance awareness of political issues with finding joyful moments—even during dark times. Many important designers and creative thinkers visited her classroom, including Buckminster Fuller and Charles and Ray Eames. Artist Ben Shahn once called her “a joyous revolutionary” and in the media she was styled as a radical “pop art nun.”

Art was a Corita’s way of protesting through LOUD colors and bold designs.

During the height of Corita’s fame, the Catholic Church was reassessing many of its traditions, striving for unity and modernization under Vatican II. And yet not everyone agreed. In 1967, the Los Angeles archdiocese and Archbishop James McIntyre claimed the Immaculate Heart Community’s (IHC’s) approach to education was “communist” and referred to Corita’s work as being “blasphemous.” When the IHC sisters were ordered to end the liberating “renewal innovations” they had come to enjoy—or be asked to leave their teaching posts—many asked to be released from their vows and left in protest.

Corita’s decision to leave the order came a little sooner. In 1968, exhausted from an intense schedule and censorship from the church, Corita took a sabbatical. At the end of her time away, she left the Order and moved to Boston. There, she continued to receive commissions and to create art such as painting the Boston Gas Company’s tanks and designing the iconic “Love” postage stamp.

Corita Kent continues to be celebrated through exhibitions and publications. This book, Make Meatballs Sing: The Life and Art of Corita Kent, introduces young audiences to her story. / Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux

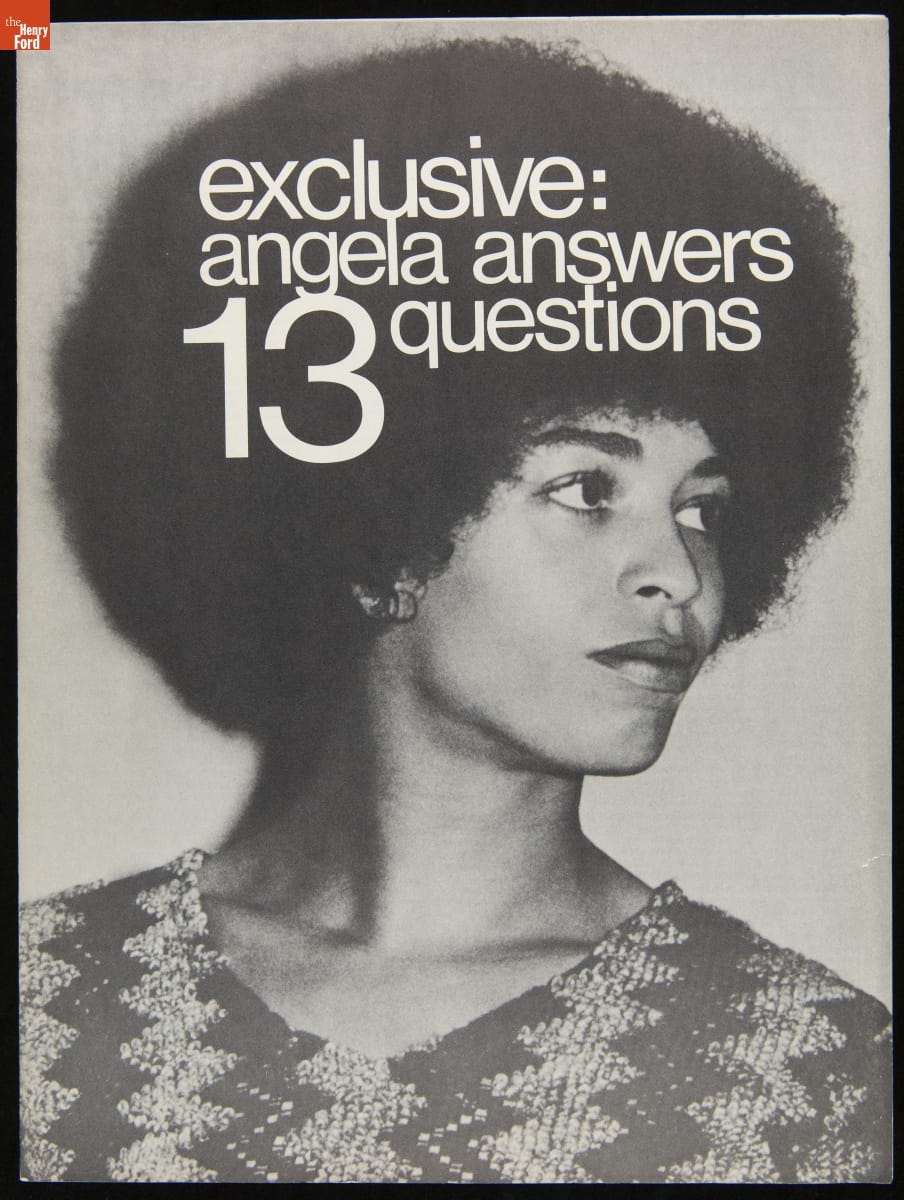

Angela Davis

Angela Davis is an activist, educator, and scholar who was a member of the Communist Party USA and the Black Panther Party. In 1970, Davis was placed on the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list. Guns registered to her name were used in a fatal attempt to free the Soledad Brothers during a courtroom trial. Davis was not present at the event. She fled police, fearing unfair treatment. After her capture, she spent 18 months in prison until being cleared of charges.

For some people, Davis is a controversial figure who believed in non-peaceful protest. To others, she is an inspiration as an outspoken supporter of women’s and civil rights, prison reform, and socialism. In recent years, she came out as lesbian and advocates for LGBTQ+ rights as well as those of Palestinian people.

The following artifacts relate to the impact of Angela Davis’s activism, past and present..jpg?sfvrsn=cc0a3601_2)

Vermont S. Galloway—a WWII veteran—made this “FBI Captures Angela” screenprint at Westside Press to advocate for Davis’s freedom. Galloway was fatally shot by the Los Angeles Police Department in 1972. / THF277084

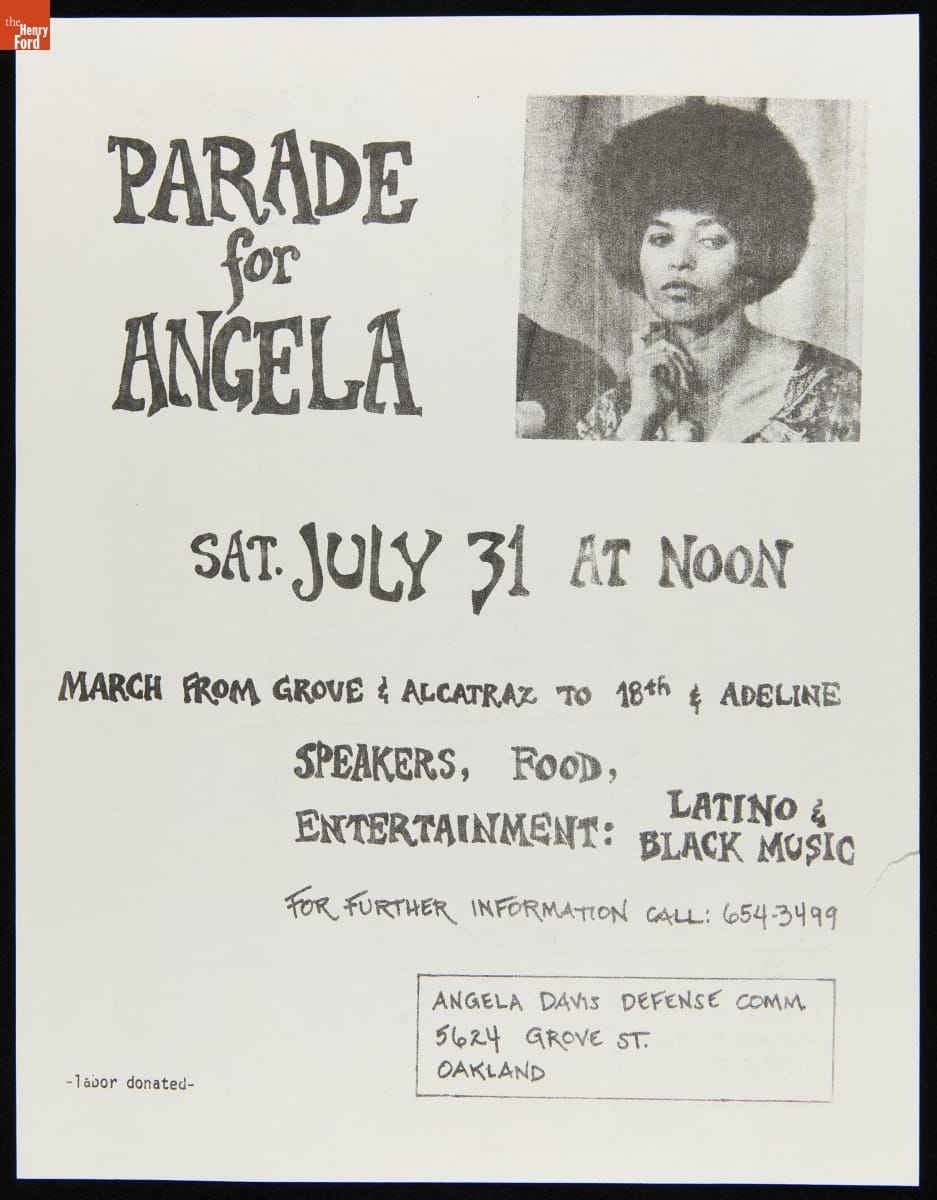

A parade flier documents the international “Free Angela” movement. The reverse side shows the planned route through Oakland, California. / THF627614

“13 Questions…” was the first interview with Davis while she was incarcerated. Her discussion with Joe Walker covers topics such as the surveillance of Black people, legal corruption, solidarity, and dismal prison conditions. / THF627594

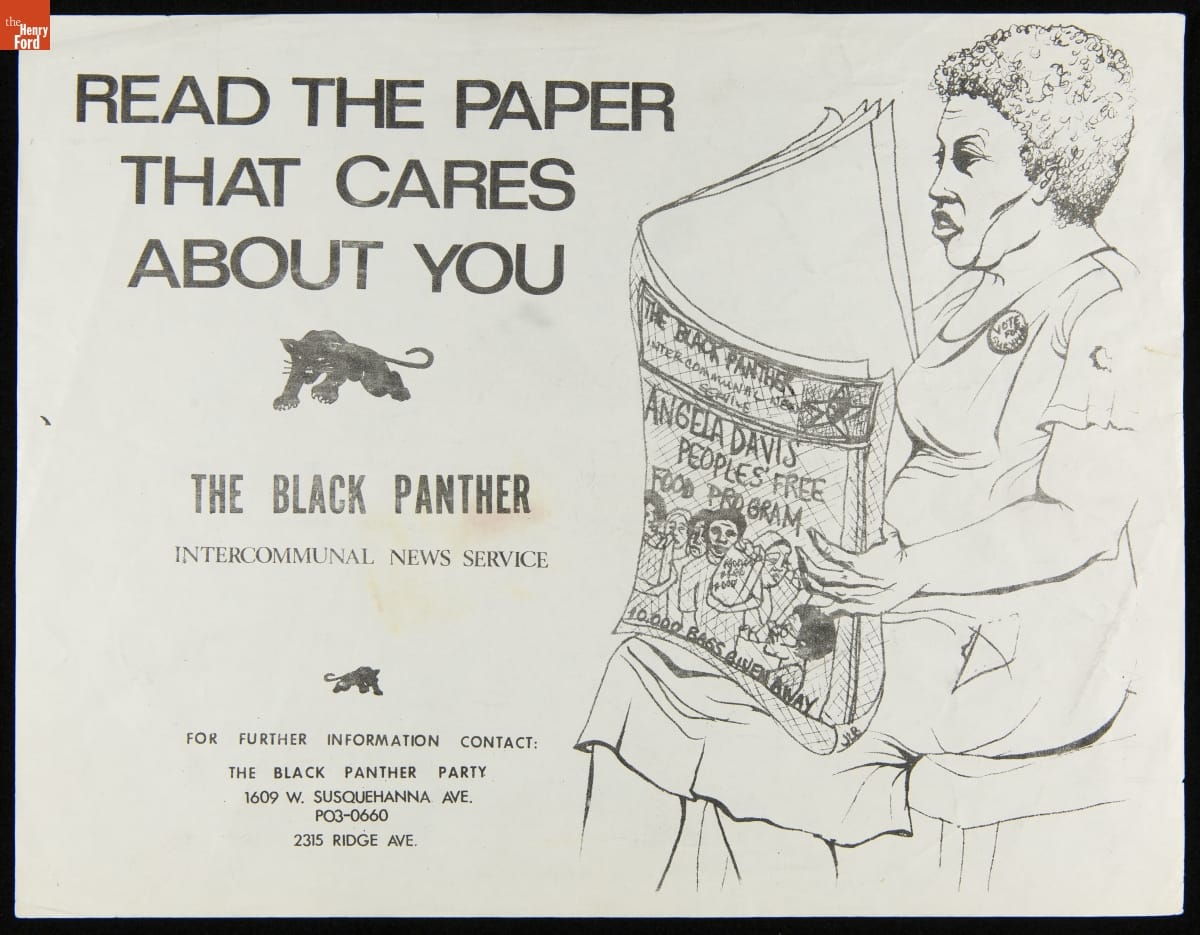

An illustration by Akinsanya Cambon advertises the Black Panther Party’s newspaper and the “Free Breakfast for Children Program,” using Davis’s name. / THF627598.jpg?sfvrsn=c40a3601_2)

Davis appears in a poster by Tongva artist Mer Young for the Amplifier Foundation. This poster shows the continued impact of Davis’s legacy and was created to encourage Black and Indigenous voting in the 2020 election. / THF626361

Listening to Our Community

In 2021, The Henry Ford began to seek community feedback for ways to update and improve our permanent exhibit With Liberty and Justice for All. This work is continuing in 2022.

Stories of movements, social innovators, and political history are difficult to fully capture in museum labels. There is always too much to tell in 100 words or less. To address this, throughout the display of this exhibit, we will be inviting several community partners to contribute their own labels, in their own voices, to foreground the issues they believe matter the most.

By the Curatorial Staff of The Henry Ford. Quiet & Loud Protest is on view in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation until March 31, 2022.

Civil Rights, art, making, women's history, African American history, Henry Ford Museum, printing

1927 Plymouth Gasoline-Mechanical Locomotive

An unsung hero on our railroad: the 1927 Plymouth Gasoline-Mechanical Locomotive. / THF15920

When you think of the railroad locomotives in Greenfield Village, you probably picture one of our operating steam locomotives, or maybe the diesel-electric that occasionally steps in to pull passenger trains. You might even picture the Atlantic type steam locomotive inside the Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse that you can walk underneath. But there’s another important member of our fleet that’s easy to overlook: our 1927 Plymouth Gasoline-Mechanical Locomotive.

Even as trucks and highways spread in the first half of the 20th century, industrial America largely still ran on rails. Manufacturers relied on railroads to bring in raw materials and ship out finished goods. The largest factories had extensive railyards filled with cars that needed to be shuttled around. Raw materials used by those factories were supplied by extractive enterprises like mines, quarries, and logging operations that operated internal railroads of their own. Clearly, there was a market for reliable, easy-to-operate locomotives that could be used on these private industrial railroads.

The J.D. Fate Company got into that market in 1914, building diesel and gasoline locomotives under the “Plymouth” brand (named for the company’s hometown of Plymouth, Ohio). Five years later, the firm combined with Root Brothers Company to form the Fate-Root-Heath Company. The newly-merged business manufactured brick and tile-making machinery, hardware and grinders, farm tractors, and—of course—light industrial locomotives.

What made Plymouth locomotives so simple and reliable? Our 1927 example is a gasoline-powered, mechanically driven machine. Its powertrain has more in common with the family car than with a steam locomotive. Steam locomotives burn coal in order to heat water and produce steam. That steam is fed into cylinders, where it pushes pistons that move rods that, in turn, move the driving wheels. Steam locomotives require specialized knowledge and skill to operate.

“Plymouth Gasoline Locomotives”—both the brand and the fuel are clear in this photo. / THF15919

Our Plymouth locomotive is powered by an inline six-cylinder gasoline engine. While it’s larger than what you’d find in a typical car (the Plymouth engine’s displacement is around 1,000 cubic inches), it operates under the same principle. Gasoline is fed into the cylinder and ignited by a spark. The resulting explosion pushes a piston that turns a crankshaft that, via a transmission, turns the driving wheels. And, like an automobile, the Plymouth’s transmission includes a clutch and a four-speed gearbox. If you can drive a car, then you can quickly learn to operate a Plymouth locomotive.

No two industrial railroads were the same, so Plymouth manufactured locomotives in multiple configurations. Track gauge—the width between the rails—was the most important consideration for a Plymouth customer. Standard gauge on American mainline railroads is 4 feet, 8 ½ inches—or 56 ½ total inches. But many industrial operations used less expensive narrow-gauge track. Plymouth built to suit anything from standard gauge down to 18 inches. Furthermore, Plymouth’s spring suspensions and short wheelbases were well suited to rough track with sharp curves.

Over the years, Plymouth also offered different engines and drivetrains. While our locomotive burned gasoline, other Plymouth engines used diesel fuel. (Note that these diesel Plymouths were still mechanically driven. They should not be confused with diesel-electric locomotives, which drive their wheels with electric motors.) In the mid-1940s, Plymouth introduced smooth-running torque converter fluid couplings as an improvement over its earlier mechanical clutches.

Industrial railroads may have been Plymouth’s main customers, but they weren’t the only ones. The company also sold locomotives to temporary railways—those built and used for construction projects like dams, bridges, and highways. Plymouth locomotives were practical, flexible machines that served an important niche market.

Our 1927 Plymouth locomotive earlier in its life, moving coal cars around Detroit’s Mistersky Power Plant, circa 1930. / THF113043

Our Plymouth locomotive was ordered by the Detroit Public Lighting Department—predecessor of today’s DTE Energy—in 1927 at a price of $6,800. It was delivered to the Mistersky Power Plant, a coal-fueled generating station located four miles southwest of downtown Detroit. The 14-ton locomotive spent the next four decades shuttling coal-filled hopper cars around the plant. The Plymouth was retired around 1970 and spent its last years at the plant sitting unused. It came to The Henry Ford in 1980. Today it’s used to move locomotives and cars around the roundhouse and yard in Greenfield Village—just the sort of job a Plymouth was designed to do.

As for the Fate-Root-Heath Company, it was acquired by Banner Industries in the 1960s and renamed Plymouth Locomotive Works. In 1997, Ohio Locomotive Crane bought the firm and, two years later, relocated it to Bucyrus, Ohio, not far from Plymouth. The company no longer builds new locomotives, but spare parts are made under license by other manufacturers. As for the work once done by Plymouth locomotives, while many shippers transitioned to trucks and highways, there are still industries that rely on rail transportation. Many of them now use motorized railcar movers—rubber-tired tractors with auxiliary flanged wheels and railroad couplers. These modern movers offer all the advantages of a Plymouth, but with greater flexibility.

There’s an interesting coda to our Plymouth’s story. Throughout its life at the Mistersky Plant, the locomotive was operated by engineer Charles Vaughn. Born and raised in Indiana, Vaughn moved to Detroit to work on the construction of the Mistersky facility. When that was done, he stayed on to operate the locomotive. Vaughn had no prior experience in railroading but, with an easy-to-run Plymouth, that wasn’t as issue. Mr. Vaughn remained at Mistersky for 45 years before retiring in 1972. In recognition of his long service, Vaughn’s co-workers presented him with the Plymouth’s bell and whistle as parting gifts. (The locomotive’s retirement came before Vaughn’s, so those safety appliances were no longer needed.)

The Plymouth’s original bell, once a retirement gift and now reunited with the locomotive. / THF188367

Charles Vaughn passed away in 1982, but his family held on to the bell and whistle. In 2013, Mr. Vaughn’s family decided to reunite the items with the locomotive. They gifted the bell and whistle to The Henry Ford, and we put them right back onto the Plymouth. We’d like to think Mr. Vaughn would’ve appreciated that thoughtful gesture by his descendants—and the fact that Greenfield Village visitors can still see (and hear) the little locomotive with which he spent so much of his career.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Edison Dynamo Used on SS Columbia, 1880

- Electrical Connection

- Pioneers of Electricity

- Electricity? I’ll Take a Pound…

Michigan, Detroit, power, by Matt Anderson, railroads, Greenfield Village

The Deleted Slavery Passage from the Declaration of Independence

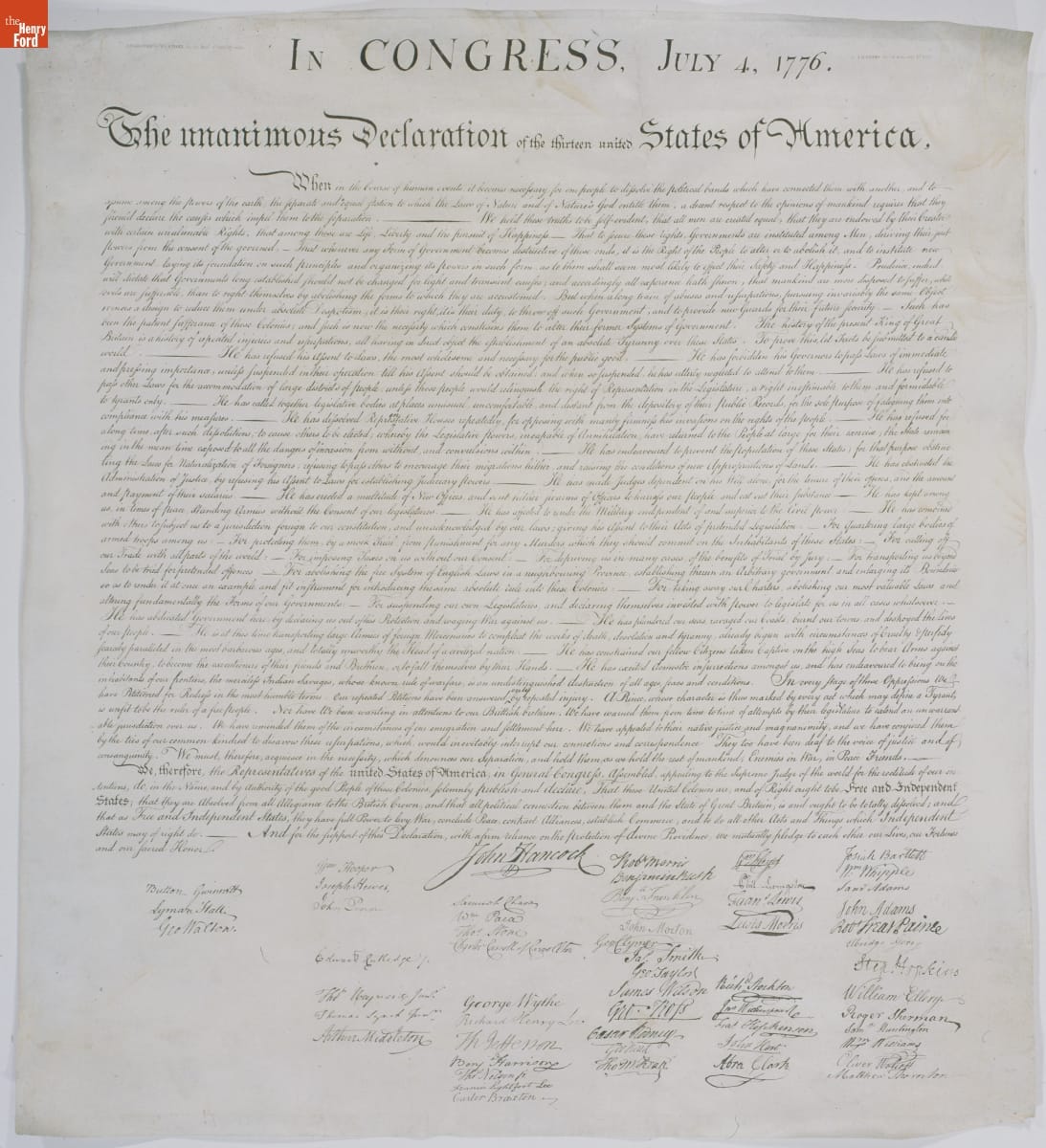

Engraved copy of the Declaration of Independence, one of only 200 copies commissioned by then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, printed 1823. / THF149572

Engraved copy of the Declaration of Independence, one of only 200 copies commissioned by then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, printed 1823. / THF149572

The Declaration of Independence, formally adopted on July 4, 1776, by members of the Second Continental Congress, was America’s manifesto against British tyranny. Thomas Jefferson, a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress (and eventually a U.S. president), had been charged with composing the draft of this document.

Most people are familiar with these iconic lines from the Declaration of Independence:

…We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness…

This is the statement that is most memorable. It is the passage that has been invoked repeatedly throughout our history as a call to action, the passage that is still referenced today as the rationale for upholding people’s individual rights.

But there is much more to the Declaration of Independence than these lines. Further down, within a lengthier portion of the document, Jefferson’s initial draft included a scathing denouncement of slavery. If this passage had been retained, our country’s history might have been very different. But it was deleted.

Why did Jefferson—a slaveholder himself—write this passage denouncing slavery, why was it deleted, and what was the long-term impact of that decision?

The Slavery Passage

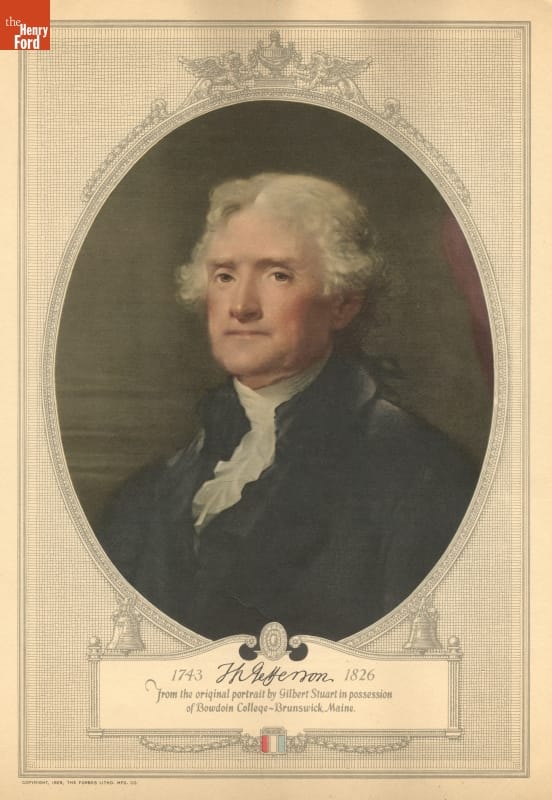

Print of Thomas Jefferson, 1929, based upon original 1805 portrait by Gilbert Stuart. / THF2295

The memorable first portion of the Declaration of Independence is full of soaring rhetoric derived from the Enlightenment ideals that Jefferson favored. The Enlightenment, an 18th-century European intellectual movement, stressed liberty and equality as natural human rights. The words in this first portion of the document were more philosophical and aspirational than the reality—and, indeed, they have lent themselves to reinterpretation and redefinition throughout our country’s history.

The later portion pertained to specific issues of the time. It contained a list of perceived wrongdoings against the colonists for which Jefferson blamed Great Britain’s King George III. These included the king’s repeatedly interfering with the colonists’ laws and ability to govern themselves; his placement of hostile troops in their midst; and his generally acting like a “tyrant” while violating Americans’ rights (for more on colonists’ mounting frustrations, see our post about the Boston Massacre). Nearly 30 charges were railed at King George III in Jefferson’s first draft, all intended to justify the colonists rebelling against him.

Included in this list was a 168-word passage condemning slavery as one of the many evils foisted upon the colonists by the British crown. Jefferson’s inclusion of this “evil” within this context was a tactically shrewd decision. It was easy to blame King George III for the institution of chattel slavery (that is, the buying and selling of people as property) with the rest of the “long train of abuses.” This was a key point of contention between Great Britain and the colonies.

The first part of the so-called “slavery passage” was aimed directly at the King:

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither…

The second part of this passage alluded to a 1775 proclamation by British Lord Dunmore, which offered freedom to any enslaved person in the American colonies who volunteered to serve in the British army to fight against the American patriots:

…he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed again the Liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

Lord Dunmore’s 1775 proclamation indeed inspired thousands of enslaved African Americans to seek liberty behind British lines. It also incensed American patriots. Including a direct reference to this, Jefferson knew, would further rally colonists behind the cause for independence and their commitment to rebellion.

Deleting the Passage

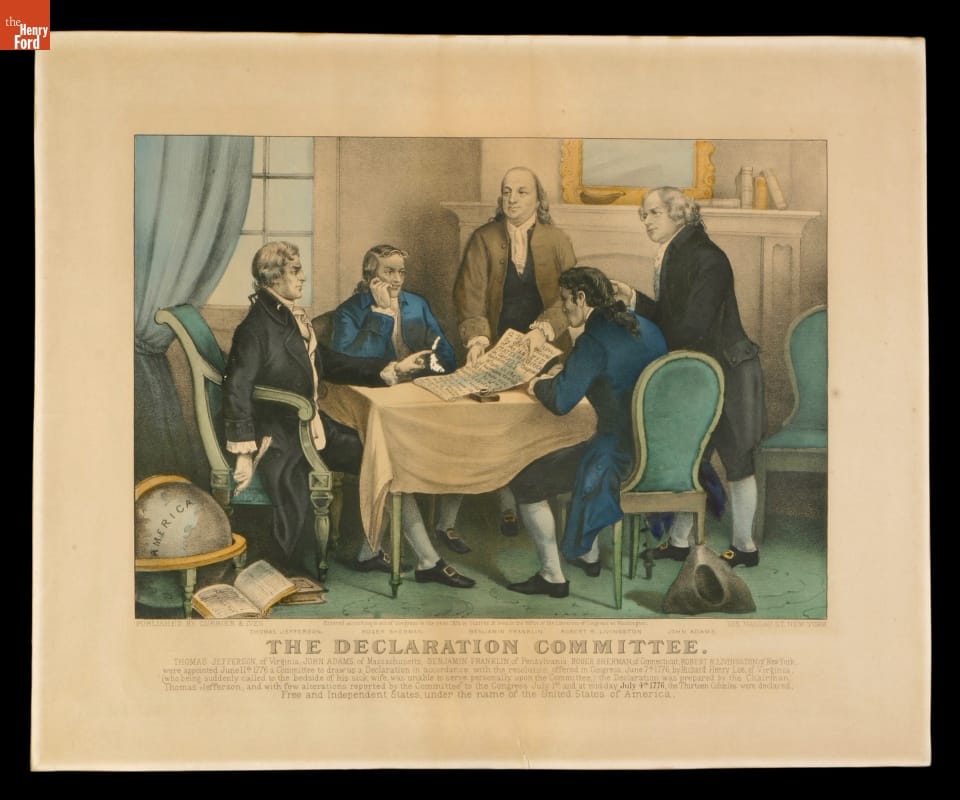

Engraving of members of the “Declaration Committee” reviewing Jefferson’s draft, Currier & Ives, 1876. In addition to Jefferson, this committee consisted of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. / THF97316

After four members of a small sub-committee reviewed Jefferson’s draft, the entire 56-member Second Continental Congress then debated its merits. The exact circumstances of this debate may never be known, as there is no written record of it. We do know, however, that during this debate, the slavery passage was removed.

Why did this occur?

The short answer is that too many delegates, and the colonies they represented, had a vested interest in perpetuating the institution of chattel slavery. Southern plantation owners insisted that they needed free labor to produce tobacco, cotton, and other cash crops for export. Northern shipping merchants depended upon the trans-Atlantic triangular trade of rum, sugar (generally in the form of molasses), and enslaved Africans. At the time, slavery existed in all 13 colonies, and at least one-third of the delegates to the Second Continental Congress (who would go on to become the signers of the Declaration of Independence) owned slaves themselves.

In addition to their own self-interest, the delegates had a larger intent in mind when they deleted the references to slavery in the document. They realized that this manifesto would inevitably lead to war. This document had to convince thousands of colonists to voluntarily risk their lives in a rebellion against the British. The grievances against King George III needed to be ironclad and compelling. They had to unify Americans from 13 very different colonies and from all walks of life. They needed to clearly distinguish friends from enemies. Removing the slavery passage, the delegates felt, helped clarify their arguments and achieve these goals.

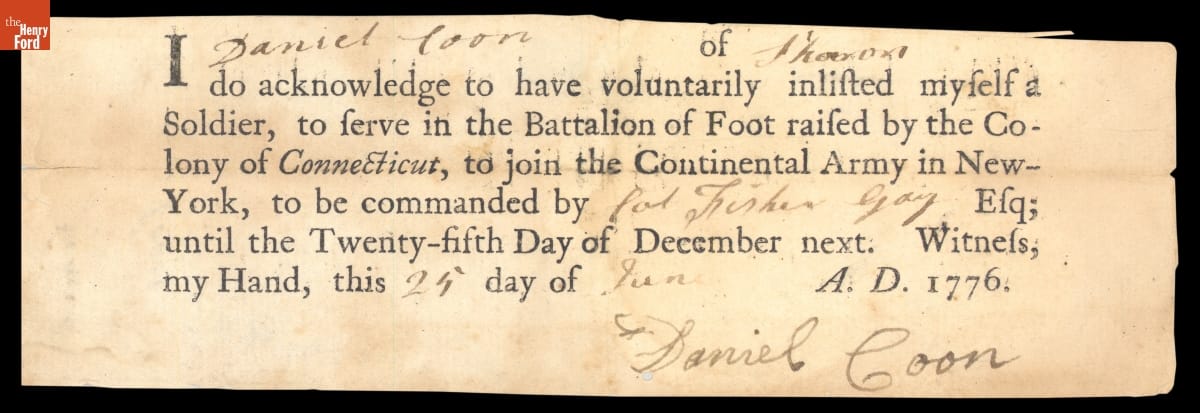

This Connecticut patriot enlisted in the Continental Army just before the Declaration of Independence was formally approved. / THF126080

Finally, there was also a prevailing belief at the time that slavery in America was on the wane—that the general emancipation of slaves was imminent and inevitable. Taking the path of least resistance, the delegates chose not to face this divisive issue head-on. Their delay tactic would not last for long, however, as the issue immediately emerged again during the drafting of the U.S. Constitution in 1787.

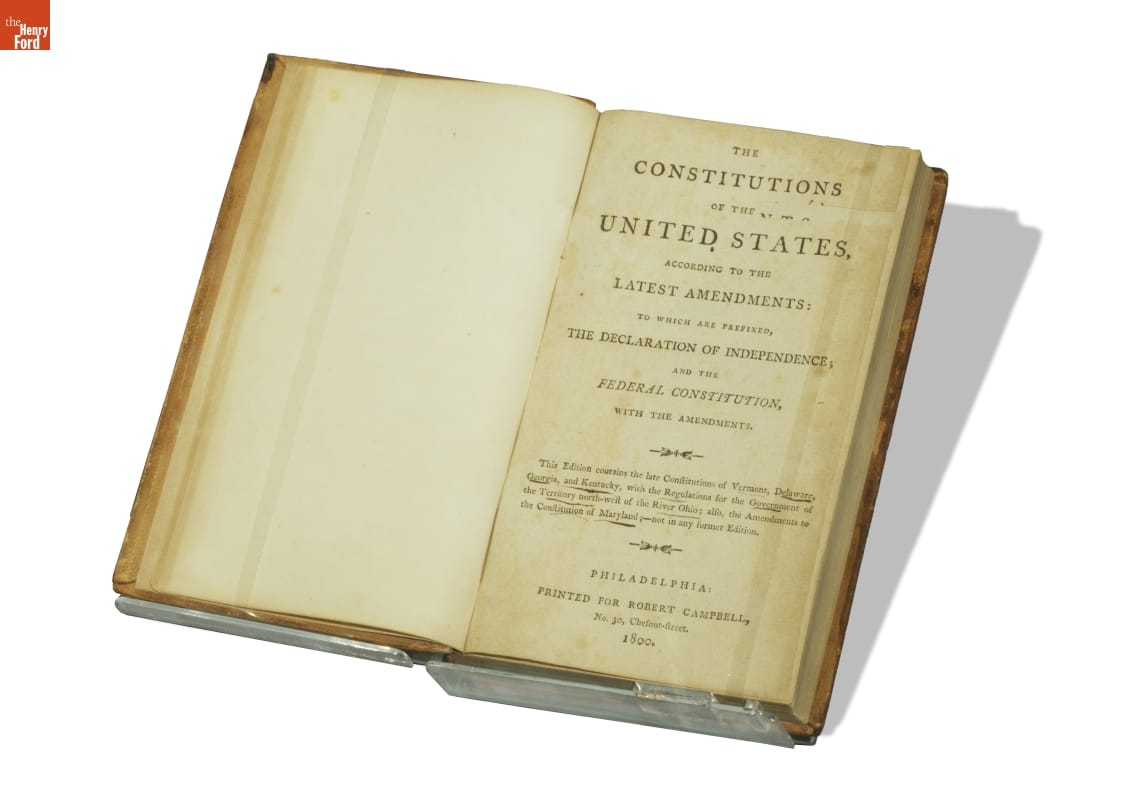

Copy of the U.S. Constitution, a rare survivor from 1800, including the text of the founding documents as well as the constitutions of the 15 then-existing states and the Northwest Ordinance, which regulated the Northwest Territory. / THF155864

In the end, the delegates replaced the deleted slavery clause with a passage that instead highlighted King George III’s incitement of “domestic insurrectionists among us”—a direct reference to the British stirring up, encouraging, and supporting warfare between colonists and Indigenous tribes:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

This was a statement, the delegates believed, that the colonists could truly rally behind. They made no more changes after that.

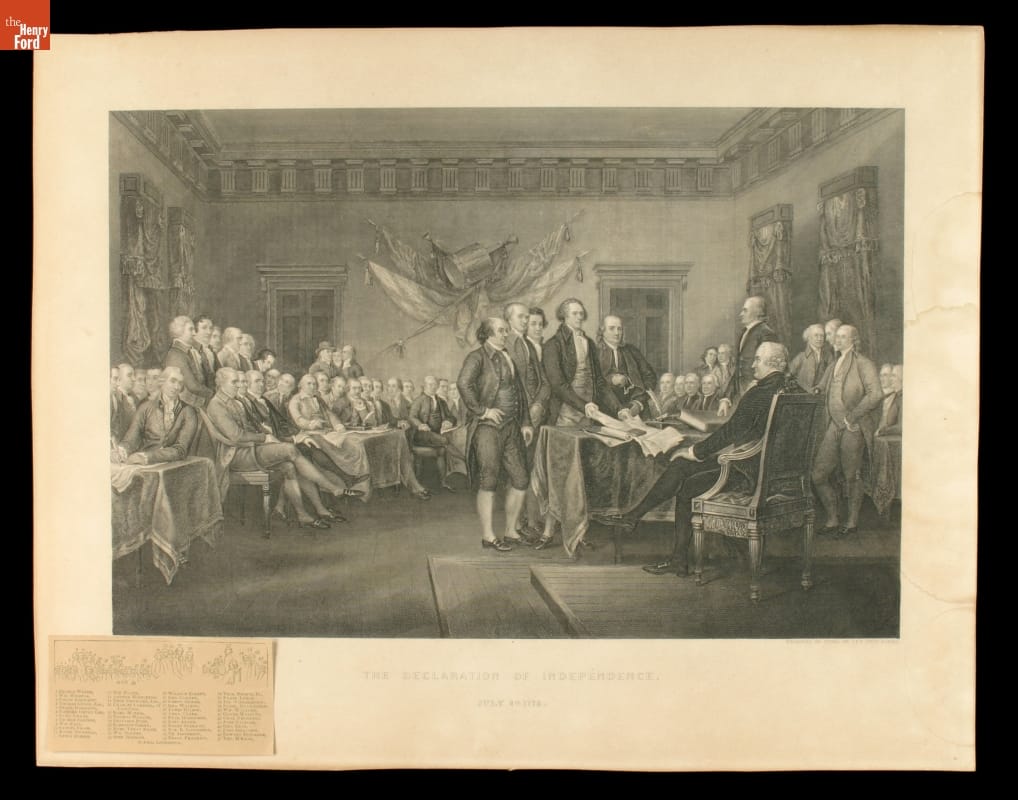

This engraving depicts the June 28, 1776, presentation of the draft of the Declaration of Independence from the five-member Declaration Committee to the entire Second Continental Congress. Engraving made about 1850 by J.F.E. Prud’homme, based upon an 1817 John Trumbull painting. / THF97322

And so, on the fourth day of July, 1776, with the adopted Declaration of Independence in hand, the thirteen American colonies formally declared their independence from Great Britain.

Thomas Jefferson quietly seethed about the changes to his draft of the document, especially the deletion of the slavery passage. He was, in fact, deeply conflicted about the institution of chattel slavery. He understood that his own livelihood depended upon its perpetuation and, over his lifetime, enslaved over 600 people (including his own children by enslaved woman Sally Hemings). At the same time, he bemoaned the existence of slavery and was continually frustrated that he could not extricate himself from its “deplorable entanglement.” As U.S. president in 1807, he passed significant legislation prohibiting the “importation of slaves to any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States.” But he also suspected that Black people were inferior and supported the popular notion that newly emancipated slaves should leave the U.S. and resettle in Africa or the West Indies.

Impact of the Revised Passage

What the signers of the Declaration of Independence did not realize at the time was that instead of weakening or dying out completely, slavery would become more widespread, profitable, and entrenched in American society. They did not know that slavery would become the central defining problem that would lead to the bloody U.S. Civil War.

The decision to remove the slavery passage and replace it with a passage about “domestic insurrectionists” (i.e., Indigenous tribes) also left a long shadow over the definition of who was considered part of the new republic and who was not—in essence, defining who was an American and who was an outsider (African Americans, both enslaved and free, as well as Native Americans). It consequently ensured that systemic racism against these groups would become as foundational as the American ideal of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

The deletion of Thomas Jefferson’s slavery passage in the Declaration of Independence had powerful and far-reaching consequences. Little did the Founding Fathers know that that we would still be feeling those reverberations today.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This blog post is part of a series that sheds new light on stories told within the With Liberty & Justice for All exhibition in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Henry Ford Museum, presidents, African American history, by Donna R. Braden

Biomimicry: Making Mother Nature Our Muse

In the face of a challenge, a walk is one of the best ways to jump-start imagination and pave a creative path forward. Take that walk in nature, or, better yet, spend a few days in nature without technology, and research shows our problem-solving abilities soar by as much as 50%.

Inventors and problem solvers need a constant supply of potent inspiration. Books and journal articles, as well as brainstorms with mentors, colleagues, and friends, help. However, in many instances our greatest teacher lives right outside our doors. There, we can find knowledge, wisdom, experience, and a solid track record of success. Nature has the answers we need to solve every problem—if only we know where to look and how to ask the right questions.

Illustration by James Round

What Is Biomimicry?

Biomimicry is innovation inspired by nature. Whether we’re working on a challenge related to product development, process generation, policy creation, or organizational design, one of the smartest questions we can ask is: “What would nature do?” Asking this question, and then studying nature to find the answers, is a way to discover new sustainable solutions that solve our design challenges without negatively impacting the planet.

Undoubtedly, biomimicry is best learned by doing. It’s a field that requires us to open our eyes, ears, and hearts as we roll up our sleeves to dig deep (sometimes literally into the dirt) to understand, interpret, and then utilize nature’s design principles to solve the challenges we face in our lives.

“Biomimicry applies strategies from the natural world to solve human design challenges,” said Alexandra Ralevski, Ph.D., director of AskNature at the Biomimicry Institute based in Missoula, Montana. “This is a field that has the power to radically transform any industry.”

Being a Bridge: Janine Benyus and the Biomimicry Institute

With varied fields of expertise, including scientific knowledge, business planning, design thinking, and operations, to name just a few, practitioners of biomimicry serve as the bridge between professional groups like scientists, business managers, policymakers, engineers, and designers, who are often siloed from one another.

If all the world is an orchestra of voices, those who study biomimicry are the conductors making room for each of them, ensuring that they rise, shine, and harmonize together for the benefit of all.

It’s impossible to utter a single word about the theory and practice of biomimicry without paying homage to Janine Benyus, a biologist, author, innovation consultant, and self-proclaimed “nature nerd.” Benyus’ groundbreaking book, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature, has made its way onto bookshelves and into the hearts, hands, and minds of problem solvers.

Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature by Janine M. Benyus. / Photo courtesy of Biomimicry Institute

“We’re awake now,” she said. “And the question is, how do we stay awake to the living world? How do we make the act of asking nature’s advice a normal part of everyday inventing?”

To explore this question and bring passionate and multitalented collaborators into community with one another, Benyus co-founded the nonprofit that would become the Biomimicry Institute in Missoula, Montana.

Over a decade later, the organization continues to provide education, support, and innovation inspiration for anyone and everyone who wants to bring the study and application of nature’s design genius into their work and into their lives.

One of the best ways to illustrate biomimicry’s power is to look at some examples.

Whales and Wind

A trio composed of a marine biologist, a mechanical engineer, and an entrepreneur created the most efficient fans and turbines in the world through inspiration found in humpback whales. On the surface, this may seem like an odd connection. How could humpback whales possibly teach a highly skilled group to build a turbine? It turns out that these whales were experts at the exact function these humans wanted to achieve.

The bumps on a humpback whale’s flipper are nature’s answer to what makes a wind turbine extra efficient. / Illustration by James Round

Humpback whales are among the world’s most agile animals. Though they can reach 16 meters (52 feet) in length and 40 tons in weight, they can lift a large portion of their bodies up out of the ocean and into the air in an acrobatic feat that leaves whale watchers breathless. A single jump or leap (called a breach) requires humpback whales to expend only 0.075% of their daily energy intake. Not only is the breach a stunning display of athleticism, it’s also a remarkably efficient action.

Marine biologist Frank Fish suspected the bumps (called tubercles) on the leading edges of the whale’s flippers held the secret to bending the ocean waters to their will. Working with Fish to study this mystery was engineer Phillip Watts. “I had been working in biomechanics and understood the importance of biomimicry, drawing engineering ideas from evolution,” shared Watts.

Together, Fish and Watts found that humpback whales achieved a rare point of design greatness: The tubercles on their flippers could increase lift while simultaneously reducing drag—a genius combination that gives these magnificent creatures such remarkable agility.

Along with a third collaborator, entrepreneur Stephen Dewar, Fish and Watts decided to model their turbine design on the humpback’s flippers. Not surprisingly, their newly fabricated turbines not only produced supreme performance like the whale’s but were highly efficient. Soon after, the trio’s newly formed corporation, WhalePower, became a leading manufacturer of energy-efficient rotating devices for various applications.

“Because nature had done so much work on this [for us],” said Dewar, “we were able to understand what was possible.”

For the Birds

Transportation aficionados know that Japan’s Shinkansen, known as the bullet train, is one of the world’s finest examples of efficient and elegant design. What many people don’t know is that the Shinkansen has a bird to thank for its performance. Known for its silent diving abilities, the kingfisher can break the water while barely making a sound or a splash to claim its favorite meal—minnows and stickleback fish.

The sleek shape of a certain bird’s beak is nature’s answer to conquering a bullet train’s unwelcome sonic boom. / Illustration by James Round

Shinkansen engineers faced a serious structural challenge while designing the bullet train: It created a sonic boom as it emerged from tunnels at high speeds. One of the team’s engineers, who had observed the kingfisher’s precise diving technique, suggested they mimic the bird’s beak shape in the train’s design. Voila! The sonic boom disappeared.

The bullet train’s unique design also had other unforeseen benefits. Its new nose safely increased travel speeds, lowered fuel consumption, and reduced operating costs.

Nature-Inspired Agriculture Infrastructure

A beehive’s structure, a spider web’s power of attraction, and an ice plant’s water storage system are nature’s answers to creating more sustainable food systems. / Illustration by James Round

To promote local agriculture, NexLoop focuses on creating renewable water infrastructure for sustainable food systems. Its main product, AquaWeb, captures, stores and distributes just the right amount of water at just the right time for local food production.

How does it strike this balance? AquaWeb takes its cues from the efficiency of nature, incorporating learnings from multiple organisms: beehives to create structural strength, spider webs to capture water, ice plants to store water and mycelium to distribute water.

Restoring Nature Using Nature’s Models

Biomimicry also guided the strategy of Nucleário, winner of the Ray of Hope Prize, an initiative of the Biomimicry Institute and the Ray C. Anderson Foundation. Company founders wanted to repopulate the forests of their home country, Brazil, where young tree seedlings face overwhelmingly adverse survival odds. Their roots are choked by grasses while their leaves are devoured by leaf-cutter ants.

Of the small handful of trees that reach their first birthday, 95% don’t live to see their second. It’s these long-shot odds that Nucleário sought to combat.

Like NexLoop, Nucleário combined the designs of several natural models to create its tree seedling pods—from the protective abilities of leaf litter and water accumulation talents of bromeliads (think of a pineapple) to the graceful air dispersal skills of anemocoric seeds.

“Our connection to nature and deep-rooted gratitude for all life inspires and sustains us,” said Bruno Rutman Pagnoncelli, CEO and founder of Nucleário. “We look to nature to guide our decisions, from design to raw material selection and everything in between.”

Combining the natural models that inspired them, Nucleário’s founders have built a planting system that provides protection as well as nutrient and moisture maintenance with less human intervention and tending. Their design is both lightweight and strong, with water chambers that collect and distribute water the same way nature does.

Hooked by Nature

Burdock burrs inspired the creation of Velcro during the mid-20th century.

In 1941, Swiss engineer George de Mestral was hunting and noticed his pants were covered with burdock burrs. He wondered how the seedpods could hold on and took to his microscope, examining the burrs’ “hooks” and the way they clung to fabric. After years of research, de Mestral was granted a U.S. patent in 1955 for what became Velcro, his famous hook-and-loop fastener.

What’s Next in Biomimicry?

“Using nature as a model for sustainability means that we always have a benchmark for our designs,” said AskNature’s Ralevski. “This benchmarking is critical to determine success and improve our iterations.”

A hallmark of nature, and by extension biomimicry, is that there is a progression of continuous improvement over time within the context of a specific situation—which could include the geography, environmental circumstances, and economic situation in which a design solution must exist and operate.

Biomimicry successes in energy management, transportation, and architectural design are spurring design experiments in fields as varied as medicine, materials science, textiles, and urban planning. We’re also beginning to see social science applications of biomimicry in community organizations, economic development, and communication systems.

“Biomimicry’s greatest legacy will be more than a stronger fiber or a new drug,” said Janine Benyus. “It will be gratitude and an ardent desire to protect the genius that surrounds us."

To explore some examples of biomimicry in artifacts from the collections of The Henry Ford, check out this expert set.

This post was adapted from an article by Christa Avampato in the June–December 2020 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Additional Readings:

- Women in Agricultural Work and Research

- Horse-Drawn Vehicles in the Country

- Contradictory Impacts: Mechanizing California’s Tomato Harvest

- Microscope Used by George Washington Carver, circa 1900

aviators, racing, Heroes of the Sky, Henry Ford Museum, flying, engineering, design, by Matt Anderson, airplanes

Piecing Together Black History: A Case Study

For centuries in America, Black history has been relegated to the margins, with stories of Black lives only recorded by those who had the means or the motivation—or perhaps the hope that future generations would value them. The second-class treatment of Black history, the result of entrenched sociocultural discrimination, is painfully obvious to historical professionals looking to the written record for answers about the past lives of Black Americans.

While a major discrepancy still exists between the quality and quantity of Black historical records when compared to white counterparts, scholarship and re-examination, aided by new technologies, have helped in making new and old information alike more accessible. With barriers to information accessibility lessened to some degree, assembling these pieces of information into individual stories remains the biggest and most puzzling challenge. A prime example of this challenge can be found in the analysis of a document from The Henry Ford’s Digital Collections—an 18th-century apprenticeship contract.

This apprenticeship document was gifted to Henry Ford in 1928 by William Van Rensselaer Abdill of Titusville, New Jersey. Abdill was a well-known collector whom Ford and others called upon to locate certain objects from history. This item was most likely part of a larger document collection that Abdill had amassed. / THF129623

On the surface, this apprenticeship document shows no indications of being related to Black history, but a careful examination proves otherwise. To start, there’s a name, “John Thompson” (or “John Thomson,” as signed at the bottom); there’s an age, “fourteen years, eight months, twenty-seven days”; and there’s a date, September 11, 1794. Other information from the document tells us that John Thomson was from Salem, Massachusetts, and was apprenticing to be a “mariner.” A careful sifting of this information through genealogical resources reveals that in May of 1809, this same John Thomson applied for a Seamen’s Protection Certificate. The application confirmed Thomson’s birth in 1780 in Salem, Massachusetts, and described him as a “negro, born-free.”

John Thomson’s application for a Seamen’s Protection Certificate included identifying information. The document states he was about five feet, three inches, in height and had several scars above his left eyebrow, as well as a scar from a smallpox inoculation on his left elbow and marks from a dog bite on his left arm. / Citation: The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; Proofs of Citizenship Used to Apply for Seamen's Certificates for the Port of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1792-1871

Further historical context helps illuminate John Thomson’s life and experiences. During the “Age of Sail,” when global commerce was facilitated by sailing ships, the city of Salem, Massachusetts, was a bustling international port. In the centuries before Thomson’s apprenticeship, slavery played a major role in Salem’s maritime economy, not only in the city’s involvement in the slave trade, but in the lives of those who worked its ships and docks. Even after Massachusetts became the first state to abolish slavery in 1783, slavery’s discriminatory legacy continued. As one of the few occupations open to them, free Blacks found life on the sea as a sailor to be a more integrated and less racially tense working environment. In port cities like Salem, these kinds of employment opportunities helped lay the foundation for Black communities in the early years of America.

John Thomson’s 1794 contract also reveals clues about how the then-14-year-old spent the next six years of his work life apprenticed to Captain Robert Emery on the ship Diana. Information on the ship and its captain (in contrast to Thomson) is plentiful. We know that the Diana was built in 1790 up the coast in Amesbury, Massachusetts, and was used to carry trade with Europe. Sometime in 1793, a change of ship masters occurred in New York City and the Diana was transferred to Emery, who was merely 20 years of age at the time.

Information from the first part of the document tells us that Robert Emery was the master of the ship Diana (whose owners were based in Boston), and that John Thomson’s apprenticeship would last just over six years. / THF129623, detail

In 1794, Emery was hiring a crew for an upcoming trip to Bristol, England, and needed an apprentice. Apprenticeships were standard in a variety of trades during this period of American history. Usually, a boy of about 13 or 14 would be indentured to a master until he reached the age of 20 or 21. In return, the master would provide food, clothing, shelter, and, most importantly, training. For Black adolescents like John Thomson, whose opportunities were limited, a stable source of food, clothing, and training could be life changing. Racially integrated crews were common for ships sailing out of Northern port cities. In 1805, five years after Thomson’s apprenticeship ended, Emery hired another racially integrated crew to sail out of Salem for India aboard the vessel Golden Age. Among the group were two local Black men: a “first mate” (next rank under captain) and a “boy” (another name for an apprentice).

As part of the agreement, John Thomson would be provided “meat, drink, apparel, washing and lodging” during his apprenticeship. / THF129623, detail

Threats abounded for Black sailors when John Thomson agreed to his apprenticeship contract in 1794. A year earlier, the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act was passed, giving slaveholders the right to recover an escaped slave. Abuse of the law began immediately, as it offered no procedural protections for free Blacks to avoid being seized as slaves—no right to a lawyer or a trial by jury, or even to speak on their own behalf. Furthermore, the British were struggling to staff a massive navy and actively forced thousands of unwilling American sailors into service. In an effort to stop illegal impressment by the British, Congress began issuing Seamen’s Protection Certificates in 1796, which worked as identification papers and proof of a sailor’s American citizenship. These kinds of papers would have been doubly important to Black sailors who were also under constant threat of being enslaved.

“J.W. Keese” of the “City of New York” notarized the agreement at some point in time. / THF129623, detail

In the years preceding Seaman’s Protection Certificates, around the mid-1780s sailors began carrying papers that helped prove their identity. These could have been copies of parish or town records or a notarized statement by a reputable person who could attest to the bearer’s American citizenship. Notarizing this apprenticeship document, most likely Thomson’s only proof of identification, would have been vitally important. The writings along the side of the document speak to this, as they show that this document was notarized by John Keese of New York City—a notary public, attorney, and founding member of the New York Manumission Society. As New York was a major port city, it’s likely Thomson would have been there at some point, and while the Manumission Society played a paternalistic guardian role in lives of New York’s slaves and free Blacks, it would have been one of the only groups advocating for Black rights in general. For free Blacks like John Thomson, having Keese’s name on the document carried weight if anyone questioned his identity.

The reverse side of the agreement confirms Thomson finished his apprenticeship in Salem on October 8, 1800. / THF129624

We know little about Thomson’s time on the Diana, except for the fact that at some point in the late 1790s, Emery armed the ship for protection against the French. According to the reverse of the contract, Thomson’s apprenticeship ended in Salem in 1800. Details about the remainder of Thomson’s life and career remain lost (or at least very well hidden) to history—whether or not he had a family (some sources suggest he married Violet Wilkins in 1817), if he joined fellow Black sailors in defending the nation during the War of 1812, or even when he died. What has endured though, are the pieces of information that provide enough clues to tell a meaningful part of Thomson’s story—and offer an important lens into the lives of early Black Americans.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. He would like to point out that numerous digital resources were used in the researching of this blog—from genealogical resources like Ancestry.com and academic resources like JSTOR, to the digitized collections of many other institutions.

Women in Agricultural Work and Research

Woman with Machine Spinning Soybean Fiber into Soylon Thread, March 1943 / THF272609

One of The Henry Ford’s main collecting areas is agriculture and the environment. Last fall, Processing Archivist Hilary Severyn shared highlights from our archives around women in agricultural work and research as part of our History Outside the Box program on Instagram. If you missed it, you can check out her selections, which range from women working on soybean research to the Women’s Land Army to Rachel Carson’s fight against pesticides, in the video below.

archives, History Outside the Box, Rachel Carson, soybeans, environmentalism, women's history, agriculture, by Ellice Engdahl, by Hilary Severyn

“The Night Before Christmas” program at Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village. / Photograph by Amy Nasir.

Guests of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village have been captivated by our various dramatic programs for decades at The Henry Ford. And Anthony Lucas’ performances as an historical actor have been essential in bringing our stories to life throughout many time periods and historical contexts. I had the honor of sitting down with Anthony, 2010 winner of The Henry Ford’s Steven Hamp Award, to chat about his 20 years of theatrical work at The Henry Ford.

You’ve been performing at The Henry Ford since the fall of 2000. What was your first project here?

I started as a replacement actor when another actor was out sick, and I performed in a program called “Gullah Tales” near the Hermitage Slave Quarters. After this, they called me back to do more performances.

How did you get into acting and what inspired you to act?

My interest to become an actor goes back to when I was five years old, believe it or not. I used to watch a gentleman named Bill Kennedy, a local TV host in Detroit who would show a lot of black-and-white Hollywood movies on Sunday afternoons. I would watch actors like James Cagney, and I said in my mind: “Wow, I want to do that!” I have a lot of favorite actors, but James Cagney was the first one because of his energy and his versatility. He could play a lot of different roles other than playing the bad guy. All the movies I watched on Bill Kennedy at the Movies were very entertaining, and they made a big impression upon me, including all the musicals and the films that starred Shirley Temple, Humphrey Bogart, Edward G. Robinson, and Bette Davis—the Golden Age of Hollywood.

What were your first theatrical roles and when did you perform them?

I really didn't get the opportunity to act until at the end of the 11th grade in high school. The following year, I did two plays. One was kind of a historical play dealing with Black history. It was called “In White America,” and it was a series of vignettes and monologues about civil rights and the Black struggle for freedom in the United States. And the other play was a kind of comedy farce called “Day of Absence.” The story took place in the South, and it dealt with what would happen if one day all the Black folks had suddenly disappeared. My performances took place in the early 1970s. We were coming right out of the sixties with the civil rights movement and the Black power movement. And so that was my start. I went on to study theater at Western Michigan University and performed in various shows with Detroit Repertory Theatre and Plowshares Theatre Company.

“Elijah: The Real McCoy” program in the museum. / Photograph by Kristina Sikora (KMS Photography)

You’ve performed in several programs at The Henry Ford, which we’ll get into in a moment. But first, which one stands out as your favorite?

I love all the shows that I do, but one of my most favorite programs is “Elijah: The Real McCoy,” which I performed in both the village and museum. Elaine Kaiser, who has since retired [as Manager of Dramatic Programs at The Henry Ford], wrote it brilliantly. She wrote it for me to perform at Discovery Camp. Every show was very rewarding, and I just loved working with the kids during camp and seeing them at shows. The story starts with Elijah McCoy as a young kid, and the scenes travel through his achievements and struggles until he reaches his success as an inventor, and then into his old age. I loved to perform each stage of his life and see the kids’ reactions.

Photograph by Kristina Sikora (KMS Photography)

Have there been any challenges you’ve encountered while performing?

Well, here’s a story that’s kind of funny. One summer in the village, I was very busy. While I was at Town Hall doing a couple of Elijah McCoy shows, I would need to change into a different period costume and get to Susquehanna Plantation to do “North Star Tales” as fast as I could. And then I would hurry up and go back to Town Hall, change, and do another Elijah McCoy. Thankfully, Elaine Kaiser loaned me her bike, so I could ride it between shows. So, it was quite exciting!

“How I Got Over” program at Susquehanna Plantation. / Photograph by Roy Ritchie

I’ve attended your performances at Susquehanna Plantation many times and have always been inspired when participating with other guests as we jumped from the porch steps yelling, “Freedom!” How long have you been performing at Susquehanna, and are there any other similar programs you perform in?

There were a few different shows we did at Susquehanna, and they go back to 2003, right after the renovation of the village. There is “How I Got Over,” “Tally’s Tales,” and a newer version called “North Star Tales,” which were all themed around the stories of slavery and endurance on the plantation. Last year in 2021, I narrated the North Star Gospel Chorale’s performance on the porch of Susquehanna as part of Salute to America: Summer Stroll. That was the first year, and it was really a great experience. We really enjoyed that. It's really a powerful show and I was happy to be a part of that. The Chorale also performed in the museum in February 2020, right before the pandemic, which was livestreamed on Facebook.

“I’ve Seen the Mountain Top” speech at National Day of Courage in the museum. / Screenshot from YouTube

You are also a big part of the “Minds on Freedom” program in the museum. When did that start and how did it develop?

Yes, this program started in 2004, and it was a combination of two shows—a musical act, and then a dialogue part about the Civil Rights Movement. It was merged into one show called “Minds on Freedom,” which was performed in the museum around our Celebrate Black History program in February. There was also our special celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation in June 2011, which I enjoyed being a part of. And during the National Day of Courage, celebrating Rosa Parks’ 100th birthday on February 4, 2013, I performed Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I’ve Seen the Mountain Top” speech. That's always an honor any time I get a chance to express the words of Dr. King. He was a great man, a great orator, a great minister, and a great leader. And he gave his life for us to believe them. So any time you try to deliver his speeches, you’re never going to be like Dr. King. But I use my own approach and try my best to get the spirit across.

“Elijah: The Real McCoy” program in the museum. / Photographs by Kristina Sikora (KMS Photography)

Many guests are familiar with your performances at our Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village and Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village events. How and when did these roles begin?

Oh, yeah, performing “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allen Poe goes way back with me, because it was one of the first dramatic readings I recited in high school. My mother coached me. I think if my mother had pursued acting, she may have been a pretty good actress. She helped me bring the story to life. Around 2003, Elaine Kaiser asked me to dramatize this short story for Hallowe’en from the point of view of a murderer descending into paranoia, haunted by the thumping sound of the murdered man’s heart. The program is different from Holiday Nights, because I have set times for shows. So I usually don't have a chance to interact with the audience in-between shows as much as I would like. Interacting with the audience afterwards whenever possible is a special part of being there. I'm not there just because I'm an actor to do shows. I'm there to be a part of The Henry Ford and to interact with the guests and help create that experience for them. It’s very special, unique, and moving to interact with the guests. So that's how I approach it.

I started performing at Holiday Nights just before I performed at the Hallowe’en event. Initially around 2003, I was working with a few other actors, and we were moving around the village doing a variety of poems and Christmas carols. And it was around 2004, I performed Clement Clarke Moore’s “A Visit from Saint Nick,” which we generally call “The Night Before Christmas.” I performed it as a solo act and was relocated outside of Town Hall and later to a warming fire. It’s developed into a very special event because of how guests react. There was one guy who proposed to his girlfriend at my warming fire. There are so many people with stories of their own, making Holiday Nights and the village a big part of their lives. Holiday Nights is a whole story in itself. I started adding an introduction to the performance rather than just solely dramatizing the poem. I started talking about Christmas in early America. And then I would ask guests about all the different holiday foods and dishes they like, and finally I would ask: Do you like Christmas cookies? I would then ask the big question: Do you have any with you tonight?

After this, guests started bringing me Christmas cookies every year. I come home with all sorts of cookies, sugar cookies, and chocolate chip cookies and all. Oh, yeah, it's funny. But it's great, though, because people come year after year and sometimes they tell me they used to bring their children and now they're all grown up. I'm like, wow, this is a reminder of how long I've been doing it. And it's so rewarding; sometimes I look out and see people that are moved. They get emotional and so it's wonderful. And the children are the best, they can just make you feel like a million bucks. In December 2020, I recited “The Night Before Christmas” for a video during the pandemic. That was a real different take on it because they had me come in and sit down and have a storybook in my hand. So I had to rework it so it could fit that format. And I like that too. It was very comfortable and warm. That was a real nice change of pace.

“The Tell-Tale Heart” program at Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village. / Photograph by Kristina Sikora (KMS Photography)

Do you have any other stories about interacting with guests you’d like to share?

Sure. I was performing Elijah McCoy at the Town Hall one day, and there is a point where I would walk up the steps of the stage. I was playing the elderly Elijah, and I asked for volunteers from the audience to help me up the steps. So, this one little girl came up to me and she said: your tie is crooked. And she starts straightening my tie. Sometimes you just have to roll with it. That was a beautiful moment.

Another time, there was this couple that followed my shows. They took pictures of me performing Elijah McCoy in the village and “Minds on Freedom” in the museum, and other performances. The wife put together a scrapbook of their photos, and it had all these pictures and a beautiful cover. They gave it to me as a gift. I was just so speechless, you know, that they took time to create it over several months, putting this book together. I was very moved by it.

Amy Nasir is Digital Marketing Specialist and former Historical Presenter in Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2020s, 2010s, 2000s, The Henry Ford staff, Holiday Nights, Henry Ford Museum, Hallowe'en in Greenfield Village, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, events, Civil Rights, by Amy Nasir, African American history, actors and acting, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford