Posts Tagged design

Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Rail Car and the Engineering Laboratory Offices

In my last blog post, I discussed how Sidney Houghton (1872–1950), a British interior designer and interior architect, met and befriended Henry Ford during World War I and, following the war, became part of the Fords’ inner circle.

The Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford holds significant correspondence, designs, and records relating to commissions between Houghton and Henry and Clara Ford. Probably the single document that details the variety of Ford commissions associated with Houghton is a brochure, more of a portfolio of projects, published by Houghton in the early 1930s, to promote his design firm.

Cover of Houghton brochure. / THF121214

From Houghton’s reference images, we can document many commissions that no longer survive, as well as provide background for some that are still do. This post centers on two projects, the Fair Lane rail car and Henry and Edsel Ford’s offices in the Ford Engineering Laboratory, which still exist. Fortunately, aspects of both still exist in The Henry Ford’s collection!

The Fair Lane Rail Car

The Fair Lane rail car. / THF80274

Edsel and Eleanor Ford, Henry and Clara Ford, and Mina and Thomas Edison pose on the car’s rear platform about 1923. / THF97966

Images of the Fair Lane rail car from Houghton brochure. / THF121225a

The Fair Lane rail car was built by the Pullman Rail Car Company in Pullman, Illinois, and delivered to Henry and Clara Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, in summer 1921. A detailed history and background on the rail car by Matt Anderson, The Henry Ford’s Curator of Transportation, can be found here.

Sidney Houghton was responsible for creating the interiors and furnishings for the car. Many sources state that he worked with Clara Ford on the designs. What is likely is that Clara Ford approved or disapproved of Houghton’s design work. This is especially evident in the public rooms of the rail car—what Houghton called the “dining saloon” and the “observation parlour.”

Dining saloon in 1921. / THF148009

The same view in 2021. / THF186285

Glassware storage. / THF186283

The dining room walls are paneled in dark walnut, with veneered elements of mahogany. The effect suggests a richly appointed room from which to view the passing scenery. The styles that Houghton employed, and Clara Ford approved, derived from a combination of eighteenth-century English classical styles, including the caned and oval-backed side chairs and the elegantly carved three-quarter relief columns around the walls. China and glassware were stored in built-in units fitted with slots or pegs to keep the objects from shifting during travel.

The observation saloon in 1921. / THF148015

The observation saloon in 1921. / THF148012

The observation saloon in 2021. / THF186264

Detail of the observation saloon. / THF186263

What Houghton called the “observation saloon” was where passengers would spend their days while traveling. It was fitted out with sets of upholstered armchairs below the windows and a slant front desk and bookcase against the inner wall. This was an extremely useful piece of furniture; while at the desk, you could read or write correspondence, and when done, store your letters in one of the many drawers in the desk. The upper case allowed plenty of room to store books and other reading materials. Dials above the door to the observation platform displayed the miles per hour, the time, and the outdoor temperature.

As you can see in the recent photographs, over time the painted woodwork in this room was stripped and refinished. Also, the wonderful slant front desk and original light fixtures have not survived. Fortunately, after the Fords sold the rail car in 1942, a subsequent owner lovingly restored the interior, including reproducing much of the furniture, before donating it to The Henry Ford.

The Ford Engineering Laboratory Offices

In the early 1920s, Henry Ford commissioned his favorite architect, Albert Kahn, to design what Ford called his Engineering Laboratory in Dearborn. Completed in 1923, this building came to be the heart of the Ford Motor Company enterprise. Both Henry and his son, Edsel, had offices in the building, and Henry commissioned Sidney Houghton to design identical furniture and woodwork for each. Both offices survive, as does most of the furniture, which is now in the collections of The Henry Ford. Of all of Houghton’s projects for the Fords, it is the best preserved.

Henry Ford’s office in 1923. / THF237704

Henry Ford’s office in 1923. / THF237702

Edsel Ford’s office (top) and Henry Ford’s office (bottom) from Houghton brochure. / THF121221a

In looking at the offices, one thing comes to mind: they were designed to impress. Like the rail car, they are paneled in rich walnut, with matching walnut furniture. Both have large conference tables; Henry’s is round, while Edsel’s is rectangular.

Conference table used in Edsel Ford’s office. / THF158754

The chairs and tables all feature heavy, turned, and curved legs, known as cabriole legs. They are also inlaid with woods with their grains carefully arranged to their fullest and most luxurious effect.

Desk chair. / THF158365

Armchair. / THF158349

Easy chair. / THF158367

Sofa. / THF158750

The style of this furniture is English Jacobean, deriving from forms used in the seventeenth century. The intent with this furniture was to show off wealth and good taste—as befit a person of Henry Ford’s status.

Console table. / THF158371

This console table, seen in the photograph behind Henry Ford’s desk, is inlaid with matched veneers along the drawer front and handles in the shapes of shells. The elaborately turned legs, which look like upside down trumpets, are characteristic of the Jacobean style in England. Combined with the cabriole legs on the chairs, Houghton has mixed and matched English furniture styles here in what decorative arts historians call an eclectic fashion.

Tall Case Clock, works by Waltham Clock Company. / THF158743

If the rest of the office furniture was meant to impress, the tall case clock takes it over the top. Henry Ford was known for his love of clocks and watches. This piece was undoubtedly something that he was proud to possess and show off to guests in his office.

We know from documents that Henry Ford rarely used his office. He preferred to be out in the field visiting with employees or, in later years, in Greenfield Village. Consequently, the furniture shows little signs of wear. Further, there are few photographs of Henry Ford in his office, other than those taken in 1923 when it was newly installed.

Henry Ford’s office in 1949. / THF149868

Taken two years after Henry Ford’s death in 1947, this image shows how he used the office.

Henry Ford by Edward Pennoyer, 1931. / THF174088

On the wall behind the desk is a painting by artist Edward Pennoyer, used as an illustration for a 1931 advertisement. Henry Ford undoubtedly liked the image of himself with the Quadricycle, his first automobile, and hung it behind his desk.

Photograph of Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, to Henry Ford’s right, surrounded by unknown figures, November 1941. / THF240734

Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, November 1941. / THF241506

Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, November 1941. / THF241508

Only three photographs survive of Henry Ford in his office. All date to November 1941, when the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, visited Henry Ford and toured the Rouge Factory. Guests to the Engineering Laboratory were almost always photographed outside the building or in the adjacent Henry Ford Museum or Greenfield Village.

The third photograph above shows another work of art in the office. The landscape shows Henry Ford’s Wayside Inn, in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, purchased in 1923. This, of course, was a place near and dear to Henry Ford, and helped him to realize his goal of creating Greenfield Village.

As we can see, Sidney Houghton was close to Henry and Clara Ford, designing Henry’s office and the Fair Lane rail car intimate environment, used on a very regular basis. In the next blog post, I will look at the most intimate of the Fords’ interiors—their Fair Lane Estate, onto which Houghton put his own influence during the first half of the 1920s.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner

Fully Furnished - Designs for Aging: New Takes on Old Forms

- The Enigmatic Sidney Houghton, Designer to Henry and Clara Ford

decorative arts, Sidney Houghton, railroads, Michigan, Henry Ford, furnishings, Ford Motor Company, Fair Lane railcar, Edsel Ford, design, Dearborn, by Charles Sable

Henry Ford's “Sweepstakes” Celebrates its 120th Anniversary

The original “Sweepstakes,” on exhibit in Driven to Win: Racing in America in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Auto companies often justify their participation in auto racing by quoting the slogan, “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday.” When Henry Ford raced in “Sweepstakes,” it was a case of win on Sunday to start another company on Monday. On October 10, 2021, we commemorate the 120th anniversary of the race that changed Ford’s life—and ultimately changed the course of American automotive history.

In the summer of 1901, things were not going well for Henry. His first car company, the Detroit Automobile Company, had failed, and his financial backers had doubts about his talents as an engineer and as a businessman. Building a successful race car would reestablish his credibility.

Ford didn’t work alone. His principal designer was Oliver Barthel. Ed “Spider” Huff worked on the electrical system, Ed Verlinden and George Wettrick did the lathe work, and Charlie Mitchell shaped metal at the blacksmith forge. The car they produced was advanced for its day. The induction system was a rudimentary form of mechanical fuel injection, patented by Ford, while the spark plugs may have been the first anywhere to use porcelain insulators. Ford had the insulators made by a Detroit dentist.

1901 Ford "Sweepstakes" Race Car. / THF90168

The engine had only two cylinders, but they were huge: bore and stroke were seven inches each. That works out to a displacement of 538 cubic inches; horsepower was estimated at 26. Ford and Barthel claimed the car reached 72 miles per hour during its road tests. That doesn’t sound impressive today, but in 1901, the official world speed record for automobiles was 65.79 miles per hour.

Ford entered the car in a race that took place on October 10, 1901, at a horse racing track in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. The race was known as a sweepstakes, so “Sweepstakes” was the name that Ford and Barthel gave their car. Henry’s opponent in the race was Alexander Winton, who was already a successful auto manufacturer and the country’s best-known race driver. No one gave the inexperienced, unknown Ford a chance.

When the race began, Ford fell behind immediately, trailing by as much as 300 yards. But Henry improved his driving technique quickly, gradually cutting into Winton’s lead. Then Winton’s car developed mechanical trouble, and Ford swept past him on the main straightaway, as the crowd roared its approval.

Henry Ford behind the wheel of his first race car, the 1901 "Sweepstakes" racer, on West Grand Boulevard in Detroit, with Ed "Spider" Huff kneeling on the running board. / THF116246

Henry’s wife, Clara, described the scene in a letter to her brother: “The people went wild. One man threw his hat up and when it came down he stamped on it. Another man had to hit his wife on the head to keep her from going off the handle. She stood up in her seat ... screamed ‘I’d bet $50 on Ford if I had it.’”

Henry Ford’s victory had the desired effect. New investors backed Ford in his next venture, the Henry Ford Company. Yet he was not home free. He disagreed with his financiers, left the company in 1902, and finally formed his lasting enterprise, Ford Motor Company, in 1903.

Ford sold “Sweepstakes” in May of 1902, but eventually bought it back in the 1930s. He had a new body built to replace the original, which had been damaged in a fire, and he displayed the historic vehicle in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Unfortunately, Ford did not keep good records of his restoration, and over time, museum staff came to believe that the car was not an original, but a replica. It was not until the approach of the 1901 race’s 100th anniversary that the car was closely examined and its originality verified. Using “Sweepstakes” as a pattern, Ford Motor Company built two running replicas to commemorate the centennial of its racing program in 2001.

Ford gifted one of the replicas to us in 2008. That car is a regular feature at our annual Old Car Festival in September. Occasionally, it comes out for other special activities. We recently celebrated the 120th anniversary of the 1901 race by taking the replica to the inaugural American Speed Festival at the M1 Concourse in Pontiac, Michigan. The car put on a great show, and it even won another victory when it was awarded the M1 Concourse Prize as a festival favorite.

The “Sweepstakes” replica caught the attention of Speed Sport TV pit reporter Hannah Lopa at the 2021 American Speed Festival. / Photo courtesy Matt Anderson

The original car, one of the world’s oldest surviving race cars, is proudly on display at the entrance to our exhibit Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors. You can read more about how we developed that display in this blog post.

Specifications |

| Frame: Ash wood, reinforced with steel plates Wheelbase: 96 inches |

Bob Casey is Former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from our former online series “Pic of the Month,” with additional content by Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Driven to Win: Sports Car Performance Center

- Barney Oldfield: America’s Racer

- Fast Cars and Warm Quilts: Auto Racing’s "Quilt Lady"

- 2016 Ford GT Full-Size Clay Model, 2014

20th century, 1900s, 21st century, 2020s, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Michigan, making, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, Driven to Win, design, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson, by Bob Casey, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

An Industrial Design Classic: Isamu Noguchi and the Radio Nurse

Zenith Radio Nurse, 1937 / THF37210

In March of 1938, Zenith Radio Corporation introduced a remarkable product—an elegant listening device, priced at $19.95, designed to allow parents to monitor their children after bedtime. The equipment and its setup could not have been simpler: The transmitter, called a “Guardian Ear,” could be placed close to the child’s crib or bed; the receiver, called the “Radio Nurse,” would be set close to wherever the parents happened to be spending their time. Both components would be plugged into electrical outlets, with the house wiring acting as the carrier for the transmitted sound.

The idea for the Radio Nurse originated with Zenith’s charismatic president, Eugene F. McDonald, Jr. Like all parents, McDonald was concerned about his baby daughter’s safety—especially in the wake of the kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s young son. As a result, McDonald experimented with an ad hoc system of microphones and receivers that allowed him to keep an ear out for his daughter’s well-being. Satisfied with the system’s workability, he handed it off to his engineers to create something more reliable and marketable. The finished product, however, was much more than a marriage of concerned fatherhood, ingenuity, and engineering; the presence of another creative mind—that of Isamu Noguchi—resulted in an industrial design classic. (Discover more Noguchi-related artifacts in our Digital Collections here.)

Instructions for Zenith’s Radio Nurse baby monitor depicted how the transmitter and receiver might be used in the home. / THF128154

Noguchi was responsible for the styling of the system’s most visible, and audible, component—the Radio Nurse receiver. Minimally, he had to create a vessel to house and protect a loudspeaker and its associated vacuum tubes, but actually his task was much more challenging: He had to find a way to soften a potentially intrusive high tech component’s presence in a variety of domestic settings.

His solution, remarkably, was both literal and paradoxical: He created a faceless bust, molded in Bakelite, fronted by a grille, and backed by the suggestion of a cap—an impassive abstract form that managed to capture the essence of a benign yet no-nonsense nurse. Shimmering in a gray area where the abstract and figurative appear to meet, it strikes a vaguely surrealist note—it wouldn’t be out of place in an image by Giorgio de Chirico or Man Ray. A touch of whimsy is incorporated: Adjusting the concealed volume control wheel amounts to a kind of tickle under the unit’s chin, subtly undermining the effect of the stern Kendo mask–like visage. Still, with its human-yet-mechanical features, the Radio Nurse remains slightly sinister and finally inscrutable.

Zenith’s 1938 Radio Nurse was made from molded phenol-formaldehyde resin, more commonly known as Bakelite, the first totally synthetic plastic. / THF188679

But was it neutral enough to sit close at hand without, in silence, striking its own discordant note? Its poor sales might suggest otherwise, although apparently it was a technical problem, broadcasts transmitting beyond the confines of a house’s own wiring, that gave customers cause for complaint. Alarming as the Radio Nurse might be when finally provoked into uttering one of Junior’s broadcasts, the possibility that some unknown voice might start to speak through that blank grille would surely have made the unit’s presence somewhat suspenseful.

Marc Greuther is Vice President of Historical Resources and Chief Curator at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series and was published in the September-December 2007 issue of The Henry Ford Living History Magazine.

communication, 20th century, 1930s, technology, radio, home life, design, childhood, by Marc Greuther, art

The Carriage Era: Horse-Drawn Vehicles

In this country of “magnificent distances,” we are all, more or less, according to the requirements of either business or pleasure, concerned in the use of riding vehicles.

— The New York Coach-Maker’s Magazine, volume 2, number 4, 1860

This print, circa 1875, depicts a variety of horse-drawn vehicles available from Frank D. Fickinger, a manufacturer in Ashtabula, Ohio. / THF288907

The period from the late 17th century until the first decades of the 20th century has been called by many transportation historians the “Carriage Era.” In the 17th and 18th centuries, carriages were extremely expensive to own and maintain and consequently were scarce. Because roads were poor and vehicle suspension systems rather primitive, riding in a carriage or wagon was not very comfortable. As the 19th century advanced, industrialization profoundly affected the production, design, and use of horse-drawn vehicles. In the United States, the combination of industrialization and the ingenuity of individual vehicle designers and makers made possible the production of a wide range of vehicles—some based on European styles, but many developed in the United States.

The Horse as a Living Machine

The horse is looked on as a machine, for sentiment pays no dividend.

— From W.J. Gordon, The Horse World of London, 1893

Horses pulling a carriage filled with people start as a dog barks, in this circa 1893 trade card for Eureka Harness Oil and Boston Coach Axle Oil. / THF214647

For most of the Carriage Era, business owners regarded horses primarily as machines whose principal value was in the profits that could be derived from their labor. One pioneer of modern breeding, Robert Bakewell, said that his goal was to find the best animal for turning food into money.

The vehicles themselves really make up only half of the machine. The other half, the half that makes the carriage or wagon useful, is the horse itself. In engineering terms, the horse is the “prime mover.” Thinking of a vehicle and a horse as two parts of the same machine raises many questions, such as:

- What sort of physical connection is needed between the horse and the vehicle? How do we literally harness the power of the horse?

- How do we connect more than one horse to a vehicle?

- How is the horse controlled? How does the driver get him to start, stop, and change direction?

- How are vehicles designed to best take advantage of the horse’s capabilities?

- Assuming the same weight, are some vehicle styles or types harder to pull than others?

- Are horses bred for specific purposes or for pulling specific types of vehicles?

- How much work can a horse do?

But despite what horse owners of the Carriage Era thought, horses are not merely machines—they are living, sentient beings. They have minds of their own, they feel pain, they get sick, and they experience fear, excitement, hunger, and fatigue. Today we would blanch at regarding the horse as simply a means of turning food into money.

The Aesthetic Dimension and Uniquely American Traits of Horse-Drawn Vehicles

A carriage is a complex production. From one point of view it is a piece of mechanism, from another a work of art.

—Henry Julian, “Art Applied to Coachbuilding,” 1884

Kentucky governor J. C. W. Beckham is among the party aboard this horse-drawn coach at the 27th running of the Kentucky Derby in Louisville in 1901. / THF203336

Horse-drawn vehicles were created with aesthetic as well as practical objectives. Aesthetics were asserted with the broadest connotation, expressing social position, concepts of beauty, elevation of sensibility, and the more formal attributes of design and details of construction. Horse-drawn vehicles traveled at slow speeds—from 4 to 12 miles per hour. This allowed intense scrutiny, as evidenced by 19th-century sources ranging from etiquette books to newspaper articles. From elegant coaches to colorful commercial vehicles, pedestrians and the equestrian audience alike judged aesthetics, design, and detail. In many respects, carriages were an extension of a person, like their clothes.

During the 19th century, there were many arenas for owners to display their horse-drawn vehicles. New York’s Central Park included roads designed for carriages. Central Park was a work of landscape art, and architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux saw elegant horse-drawn vehicles as essential, mobile parts of that landscape. Other cities developed similar parks on a smaller scale. But a park was not necessary—any street or road was an opportunity to show off.

Horse-drawn vehicles carry passengers through New York’s Central Park around 1900. / THF203316

Central to horse-drawn vehicle aesthetics was the “turnout.” This meant not only the vehicle itself, but also the horses, the harness, the drivers, and often the passengers. Horses were chosen to harmonize with the size and color of the vehicle, and their harness, the drivers’ uniforms, and even the passengers’ clothes were expected to harmonize as well.

Elegant turnout was not limited to the carriages of the rich. Businesses knew that their vehicles sent a message about the business itself. A smartly turned-out delivery wagon or brewery wagon told everyone that the company that owned the vehicle and team was a quality operation. Even the owner of a simple buggy could make an impression by hitching up a good-looking horse and wearing his best clothes.

These purveyors of “table luxuries” in New York, circa 1890–1915, used a horse-drawn vehicle that showed off their products—both via artwork on their wagon and via the goods themselves. / THF38079

Many things influenced the styling of vehicles. In the United States, one of the unexpected influences was natural resources. The country had abundant supplies of strong, light wood, like hickory. After 1850, more and more hickory began to be used in vehicles. American vehicles gradually took on a lighter, more spidery look, characterized by thin wheels and slim running gear. European observers were astonished at how light American vehicles were. Many American vehicles also moved away from smooth curves to adopt a sharper, more angular look. This had nothing to with function. It was simply an expression of fashion.

Diversity of Vehicle Types

When Alfred Sloan used the words, “A Car for Every Purse and Purpose,” he was describing General Motors’ goal of making a range of automobiles that filled every need and fit every budget. But substitute “horse-drawn vehicle” for “car,” and the statement could apply to the Carriage Era.

The sheer variety of horse-drawn vehicles is astonishing. There were elegant private carriages, closed and open, designed to be driven by professional drivers. At the other end of the scale were simple, inexpensive buggies, traps, road wagons, pony carts, and buckboards, all driven by their owners. Most passenger vehicles had four wheels, but some, like chaises, gigs, sulkies, and hansom cabs, had only two wheels. Commercial passenger vehicles included omnibuses, stagecoaches, and passenger wagons that came in several sizes and weights. Horse railway cars hauled people for decades before giving way to electrically powered streetcars.

This horse-drawn streetcar, or “horsecar,” circa 1890, traveled over fixed rails on set schedules, delivering residents of Seattle to and from places of work, shops, and leisure destinations. / THF202625

Work vehicles included simple drays for hauling heavy cargo, as well as freight wagons like the Conestoga and its lighter cousin, the prairie schooner. Delivery vehicles came in many sizes and shapes, from heavy beer wagons to specialized dairy wagons. Horses drew steam-powered fire engines and long ladder trucks. Bandwagons and circus wagons were familiar adjuncts to popular entertainments, and hearses carried people to their final reward. Ambulances carried people to hospitals, and specially constructed horse ambulances carried injured horses to the vet—or perhaps to slaughter if the injury was grave enough.

In the Carriage Era, horse-drawn hearses like this one, photographed in 1897, delivered the coffins of the deceased to their final resting places. / THF210197

On the farm, wagons came in many different sizes and were part of a range of vehicles that included manure spreaders, reapers, binders, mowers, seed drills, cultivators, and plows. Huge combines required 25 to 30 horses each. Rural vehicles often featured removable seats so they could do double duty, hauling both people and goods. Special vehicles called breaks were used to train horses to pull carriages and wagons. In winter weather, a large variety of sleighs was available, and many vehicles could be adapted to the snow by the substitution of runners for wheels.

This farmer’s wagon, with an open body and no driver's seat, was simple, but handy—it could readily haul this load of bagged seed or grain. / THF200482

In a series of forthcoming blog posts, we’ll look more closely at some of these very specific uses of horse-drawn transport, along with examples from our collections.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Transportation: Past, Present, and Future—From the Curators.”

Sidney Houghton is one of the most interesting and yet-to-be-documented figures in the group surrounding Henry and Clara Ford. Many in the Fords’ entourage are colorful and well-researched, including Harry Bennett, Henry’s security chief, known as the notorious head of the Ford Motor Company “Service” Department; Henry’s business manager, Ernest Liebold, who handled all financial transactions; and even their son, Edsel Ford, whose life and important cultural contributions are thoroughly documented. The great Ford historian Ford R. Bryan tells the story of these figures in his book, Henry’s Lieutenants (1993). Bryan frequently mentions Sidney Houghton, most notably in his book Friends, Family, and Forays (2002).

Perhaps Houghton remains undocumented because he was British, and in the decades before Internet resources became widely available, American researchers like Bryan had limited access to British sources. Today, we are fortunate to not only have the profound resources of the Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford at our disposal, but also digital access to repositories around the world. As Curator of Decorative Arts, I have spent considerable time trying to fully grasp the enigmatic Mr. Houghton—his biography, his business, and, most importantly, his relationship with Henry and Clara Ford. This blog is the first in a series that will delve into this mostly hidden story.

Now, you may ask, why should we care about the Fords’ interior designer? Seeing and understanding the interior environments that the Fords created to live and work provides us with great insight into their characters, creating a well-rounded picture of their lives. We can understand their motivations and desires and see how these changed over time. We can peel back the larger-than-life personas of the Fords that come with such public lives and see them as individuals.

What Do We Know About Sidney Houghton’s Early Life?

Researching Houghton was not easy. The first place I looked was Ancestry.com, but Houghton is a very common name in Britain. After a lot of digging and working with colleagues at The Henry Ford, I located Sidney Charles Houghton, who was born in 1872 and died in 1950. He was the son of cabinetmaker Charles Houghton, which likely led to his interest in furniture-making and interior design.

One of the questions still in my mind is: Where was Houghton educated? To date, I have not been able to find out which art school he attended—these records do not appear to be available online. What I do know is that he married in 1895, and had a family consisting of two sons by 1898. By 1910, according to the British census, his business, Houghton Studio, was established in London.

Houghton in World War I

From Ford R. Bryan’s publications and resources in the Benson Ford Research Center, I knew that Houghton was in the British Navy during World War I. I searched the British National Archives and found his fascinating military service record. Houghton, I discovered, was an experienced yachtsman, and was commissioned as a commander. He helped to create patrol boats, called P-boats, that swiftly located enemy submarines. In 1917, he was sent to the United States to work with Reginald Fessenden (1866–1932), a Canadian-American inventor who worked in early radio. Together, they developed an early sonar system to locate enemy ships, submarines, and mines. For his contributions to the war effort, Houghton was awarded the Order of the British Empire, or O.B.E., in 1919.

Through the reminiscences of Ernest Liebold, held in the Benson Ford Research Center, I discovered that Houghton was brought into the Ford Motor Company’s war effort to create what Liebold called the Eagle boats. These were similar to the British P-boats. Unlike the relatively simple P-boats, though, the Eagle boats would be like a “young battleship,” according to Liebold. He went on to state that the boats would “have the eye of an eagle and would flit over the seas.”

Eagle Boat #1 on Launching Trestle at the Ford Rouge Plant, July 11, 1918. / THF270275

Eagle Boat #60 Lowered to Water, August 1919. / THF270277

Liebold continued:

Houghton came along, and he said, “We ought to have a listening device put on those ships to detect submarines.” That is where [Thomas] Edison came in to develop this listening device, and I think Houghton is the man who contacted him. I remember him coming out with a long rod and stuff, and it was so darned secret that nobody knew a thing about it.

They had a special room provided for it in the Eagle boats. It was to be this listening chamber in which the apparatus was placed. They could detect a submarine by the beat of its propellers. A magnetic signal could determine just exactly in what direction it was, [sic] and approximately, from the intensity of the sound of the beating of the propeller, they could tell just what distance and in what direction it was.

They would radio that information to the nearest battleship in a cordon of battleships, or destroyers or whatever they had. They would be able to attack the submarine, you see. That was the object of it.

As an integral member of the Eagle boat team, it is highly likely that Houghton travelled to Dearborn and met Henry Ford. We know from later correspondence that Henry and Clara developed an abiding personal friendship with Houghton which continued through the 1920s. They commissioned a series of projects, beginning with the Fords’ yacht, the Sialia—but I am getting ahead of myself. At this point, I would like to discuss Houghton’s work in interior design, specifically his role as an interior architect.

Sidney Houghton’s Studio

Cover of Houghton’s Studio Catalogue, circa 1928. / THF121214

Back Cover of Houghton’s Studio Catalogue, circa 1928. / THF121230

This brochure or trade catalogue gives us great insight into the Houghton Studio. We date it to the late 1920s, when the projects Houghton worked on for the Fords were complete. From the text, we can see just what the firm’s capabilities were. The back cover reads: “Designs and estimates for decoration and furnishing of every kind / from the simplest to the most exotic / always in good style / always at exceptional values.” What this tells us is that Houghton Studio was a rarity in the interior design world.

Houghton was an interior architect, meaning that he designed both interiors and furnishings—the woodwork, wall treatments, lighting, furniture, textiles, and accessories—to create a unified interior environment. In new construction, an interior architect would collaborate with the architect to create an interior in harmony with the architecture. This contrasts with our present-day conception of an interior designer as a person who simply selects existing furnishings that harmonize to create a unified interior aesthetic. Obviously, Houghton Studio’s clients were wealthy and able to afford the best.

Chateau Laurier National Hotel, Ottawa Canada. / THF121219a

Designs for Modern Furniture. / THF121226a

Like most of his contemporaries, Houghton worked in a variety of styles, as demonstrated in the images above—from period revivals as seen in the Chateau Laurier National Hotel, in Ottawa, Canada, to his renderings for “Modern” furniture, done in what we would describe as the Art Deco style, which was synonymous with high-end 1920s taste.

List of Commissions in the Houghton Catalogue. / THF121229b

One of the most interesting pages in the catalogue notes several commissions to design interiors for yachts, which was a specialty of the Houghton Studio. The most important of these was a commission for the Sialia, Henry Ford’s yacht. The Fords purchased the yacht just before World War I, and it was requisitioned for use by the U.S. Navy in 1917. The ship was returned to Henry Ford in 1920. At this point, Sidney Houghton was asked to redesign the interiors.

Henry Ford’s Sialia

Henry Ford’s Yacht, Sialia, Docked at Ford Rouge Plant, Dearborn, Michigan, 1927. /THF140396

According to Ford R. Bryan, the cost of the interiors was approximately $150,000. As seen here, the interiors are comfortable, but relatively simple. During the 1920s, the Fords occasionally used the Sialia, but Henry and Clara Ford preferred other means of travel, usually by large Ford corporate ore carriers, when they traveled to their summer home in Michigan’s upper peninsula. According to the ship’s captain, Perry Stakes, Henry Ford never really liked the Sialia, and he sold it in July of 1927.

Parlor on Sialia, Henry Ford’s Yacht, circa 1925. / THF92100

Bedroom on Sialia, Henry Ford’s Yacht, circa 1925. / THF92098

Following the Sialia commission, the Fords found a kindred spirit in Houghton. The archives contain ample correspondence from the early 1920s, with the Fords asking Houghton to return to Dearborn. Houghton subsequently received a commission to design the interior of the Fords’ Fair Lane railroad car in 1920. Between 1920 and 1926, Houghton was deluged with projects from the Fords, including the redesign of the Fair Lane Estate interiors, design of Henry and Edsel’s offices in the new Ford Engineering Laboratory, interiors for the Dearborn Country Club, as well as interiors for the Henry Ford Hospital addition.

In the next post in this series, we will look closer at several of these projects and present surviving renderings from the Fair Lane remodeling, as well as furniture from the Engineering Laboratory offices.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Estate

- Striker to the Line: An English Plate Depicting an American Sport

- Marshmallow Love Seat, 1956-1965

- Court Cupboard, Owned by Hannah Barnard, 1710-1720

Sidney Houghton, World War I, technology, research, home life, Henry Ford, furnishings, Ford Motor Company, design, decorative arts, by Charles Sable, archives

Lawns: The Deep Roots of an American Passion

With the rise of the suburban neighborhood at the end of the 19th century and its explosive growth in the years that followed World War II, maintaining a "perfect" lawn became the new standard. Manufacturers promoted a whole set of specialty equipment to support this American obsession. / THF620523

A quintessential icon of modern American suburbia, the “lawn” has roots as deep as America itself. In the early days of the nation, the importation of European taste highly influenced the architecture and interior decoration style of the wealthy—which included the adoption of the green spaces that began appearing in French and English landscape design during the 18th century.

During his time representing the young United States in Europe, Thomas Jefferson witnessed the “tapis vert,” or “green carpet,” at the Palace of Versailles, as well as the large green swaths of closely mown grass that were common to English country estates. Both impressed upon Jefferson a grandeur that he tried to emulate at Monticello, his plantation. This European influence also extended to George Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation, where Washington hired English landscape gardeners to help create his own versions of English lawns and gardens.

These plantation sites were heavily enmeshed in the American psyche as Washington and Jefferson became mythologized over time. During the 19th century, inexpensive and easily acquired prints made both of these plantation homes, including their grounds, some of the most famous buildings in America, and gave wealthy Americans images of what they could aspire to.

A toy picture puzzle, dating to 1858–1863, featuring a picture of George Washington’s Mount Vernon on the right. The dissemination of Mount Vernon images in the 19th century showed Americans an idyllic version of the grounds. / THF168885

In the mid-19th century, citizens of increasingly industrialized cities with growing populations sought respite from the urbanization of their landscape. A solution to their problems came in the form of advocacy by prominent landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing for the creation of suburbs outside cities, as well as public parks. When Downing died unexpectedly in 1852, Frederick Law Olmsted stepped up to deliver on Downing’s visions—and bring to life some of his own.

Often considered the father of American landscape architecture, Olmsted started his career in the 1850s when he co-designed New York City’s Central Park with architect Calvert Vaux. He’d go on to design parks in Boston, Chicago, Montreal, and many other places. Olmsted not only popularized the use of green spaces in public parks, but also co-designed suburbs with Vaux—like Riverside, Illinois, in which each residential home had its own lawn or “green space.”

An early watercolor drawing of New York City’s Central Park, featuring the design work of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. / THF221839

Riverside, Illinois, marked the beginning of the migration that lawns took from city parks and wealthy estates to individual yards. By the 1890s, they were becoming a fixture of the suburban landscape as improvements in transit allowed city suburbs to grow.

With this new hobby came new technology. Enhancements to mass-production procedures over the course of the 19th century meant new machinery, like mechanical mowers, could be manufactured at a relatively low cost to help homeowners keep their lawns trimmed (no more sheep or servants needed!). While sprinklers would require cities to invest in and build municipal water systems, the ability to own a home with a lawn was slowly becoming possible for more and more Americans as infrastructure advanced in the early 20th century. Over the next 50 years, what was once uncommon would become synonymous with suburban living.

Trade Card for the Clipper Mower, Made by Chadborn & Coldwell Mfg. Co., 1880-1890 / THF297561

The mid-20th century saw the maturation of modern American lawn culture—a culture that remains relatively unchanged today. The unprecedented economic growth of post–World War II America brought a need for inexpensive housing to accommodate returning GIs and their young families. An early solution to this problem was Levittown, New York, one of the first “cookie-cutter” affordable-housing suburbs, built between 1948 and 1952 by Abraham Levitt on Long Island. The easy-to-manufacture homes of Levittown came with a lawn—along with rules on how it should look—and represented the suburbanization that was taking place across American cities at the time.

A photo of a 1955 Ford Fairlane Town Sedan, possibly used in advertising, captures the idealized 1950s “American dream”—a house, a car, and a nice lawn. / THF116716

Today’s lawn standards arise from the scientific and technological developments of the post-war period, when rotary mowers were introduced along with a number of pesticides and fertilizers now needed to keep a lawn “healthy.” Since then, the lawn has become ubiquitous in suburban living and a symbol of the middle-class American dream, as well as a big business. While the pursuit of a perfect lawn remains a pillar of identity in America, shifting cultural perceptions around how environmentally sustainable lawn culture is continue to shift the conversation on this icon of American communities.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

“Whenever Henry Ford visited England, he always liked to spend a few days in the Cotswold Country, of which he was very fond … during these sojourns I had many happy times driving Mr. Ford around the lovely scenes which abound in this part of Britain.”

—Herbert Morton, Strange Commissions for Henry Ford

A winding road through a Cotswold village, October 1930. / THF148434, detail

The Cotswolds Catch Henry Ford’s Eye

Henry Ford loved the Cotswolds, a rural region in southwest England—nearly 800 square miles of rolling hills, pastures, and small villages.

During the Middle Ages, a vibrant wool trade brought the Cotswolds great prosperity—at its heart was a breed of sheep known as Cotswold Lions. For centuries, the Cotswold region was well-known throughout Europe for the quality of its wool. Raising sheep, trading in wool, and woolen cloth fueled England’s economic growth from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution. Cotswold’s prosperity and its rich belt of limestone that provided ready building material resulted in a distinctive style of architecture: limestone homes, churches, shops, and farm buildings of simplicity and grace.

During Henry Ford’s trips to the Cotswolds in the 1920s, he became intrigued with the area’s natural beauty and charming architecture—all those lovely stone buildings that “blossomed” among the verdant green countryside and clustered together in Cotswold’s picturesque villages. By early 1929, Ford had decided he wanted to acquire and move a Cotswold home to Greenfield Village.

A letter dated February 4, 1929, from Ford secretary Frank Campsall described that Ford was looking for “an old style that has not had too many changes made to it that could be restored to its true type.” Herbert Morton, Ford’s English agent, was assigned the task of locating and purchasing a modest building “possessing as many pretty local features as might be found.” Morton began to roam the countryside looking for just such a house. It wasn’t easy. Cotswold villages were far apart, so his search covered an extensive area. Owners of desirable properties were often unwilling to sell. Those buildings that were for sale might have only one nice feature—for example, a lovely doorway, but no attractive window elements.

Cotswold Cottage (buildings shown at left) nestled among the rolling hills in Chedworth, 1929–1930. / THF236012

Herbert Morton was driving through the tiny village of Lower Chedworth when he saw it. Constructed of native limestone, the cottage had “a nice doorway, mullions to the windows, and age mellowed drip-stones.” Morton knew he had found the house he had been looking for. It was late in the day, and not wanting to knock on the door and ask if the home was for sale, Morton returned to the town of Cheltenham, where he was staying.

The next morning Morton strolled along a street in Cheltenham, pondering how to approach the home’s owner. He stopped to look into a real estate agent’s window—and saw a photograph of the house, which was being offered for sale! Later that day, Morton arrived in Chedworth, and was greeted by the owner, Margaret Cannon Smith, and her father. The cottage, constructed out of native limestone in the early 1600s, had begun life as a single cottage, with the second cottage added a bit later.

Interior of Cotswold Cottage, 1929-1930. / THF236052

The home was just as quaint inside—large open fireplaces with the mantels supported on oak beams. Heavy oak beams graced the ceilings and the roof. Spiral stone staircases led to the second floor. Morton bought the house and the two acres on which it stood under his own name from Margaret Smith in April 1929 for approximately $5000. Ford’s name was kept quiet. Had the seller been aware that the actual purchaser was Henry Ford, the asking price might have been higher.

Cotswold Cottage (probably built about 1619) as it looked when Herbert Morton spotted it, 1929–1930. / THF236020

“Perfecting” the Cotswold Look

Over the next several months, Herbert Morton and Frank Campsall, Ford’s personal secretary, traded correspondence concerning repairs and (with the best of intentions on Ford’s part) some “improvements” Ford wanted done to the building: the addition of architectural features that best exemplified the Cotswold style. Morton sent sketches, provided by builder and contractor W. Cox-Howman from nearby Stow-on-the-Wold, showing typical Cotswold architectural features not already represented in the cottage from which to choose. Ford selected the sketch which offered the largest number of typical Cotswold features.

Ford’s added features on the left cottage included a porch (a copy of one in the Cotswold village of Rissington), a dormer window, a bay window, and a beehive oven.

Cotswold Cottage, 1929–1930, showing modifications requested by Henry Ford: the beehive oven, porch, and dormer window. / THF235980

Bay window added to the left cottage by Henry Ford (shown 1929–1930). Iron casement windows were added throughout. / THF236054

The cottage on the right got a doorway “makeover” and some dove-holes. These holes are commonly found in the walls of barns, but not in houses. It would have been rather unappealing to have bird droppings so near the house!

Ford’s modifications to the right cottage—a new doorway (top) and dove-holes (bottom) on the upper wall. / THF236004, THF235988

Cotswold Cottage, now sporting Henry Ford’s desired alterations. / THF235984

Ford wanted the modifications completed before the building was disassembled—perhaps so that he could establish the final “look” of the cottage, as well as be certain that there were sufficient building materials. The appearance of the house now reflected both the early 1600s and the 1920s—each of these time periods became part of the cottage’s history. Ford’s additions, though not original to the house, added visual appeal.

The modifications were completed by early October 1929. The land the cottage stood on was transferred to the Ford Motor Company and later sold.

Cotswold Cottage Comes to America

Cotswold Cottage being disassembled. / THF148471

By January 1930, the dismantling of the modified cottage was in process. To carry out the disassembly, Morton again hired local contractor W. Cox-Howman.

Building components being crated for shipment to the United States. / THF148475

Doors, windows, staircases, and other architectural features were removed and packed in 211 crates.

Cotswold building stones ready for shipment in burlap sacks. / THF148477

The building stones were placed in 506 burlap sacks.

Cotswold barn and stable on original site, 1929–1930. / THF235974

The adjacent barn and stable, as well as the fence, were also dismantled and shipped along with the cottage.

Hauled by a Great Western Railway tank engine, 67 train cars transported the materials from the Cotswolds to London to be shipped overseas. / THF132778

The disassembled cottage, fence, and stable—nearly 500 tons worth—were ready for shipment in late March 1930. The materials were loaded into 67 Great Western Railway cars and transported to Brentford, west London, where they were carefully transferred to the London docks. From there, the Cotswold stones crossed the Atlantic on the SS London Citizen.

As one might suspect, it wasn’t a simple or inexpensive move. The sacks used to pack many of the stones were in rough condition when they arrived in New Jersey—at 600 to 1200 pounds per package, the stones were too heavy for the sacks. So, the stones were placed into smaller sacks that were better able to withstand the last leg of their journey by train from New Jersey to Dearborn. Not all of the crates were numbered; some that were had since lost their markings. One package went missing and was never accounted for—a situation complicated, perhaps, by the stones having been repackaged into smaller sacks.

Despite the problems, all the stones arrived in Dearborn in decent shape—Ford’s project manager/architect, Edward Cutler, commented that there was no breakage. Too, Herbert Morton had anticipated that some roof tiles and timbers might need to be replaced, so he had sent some extra materials along—materials taken from old cottages in the Cotswolds that were being torn down.

Cotswold “Reborn”

In April 1930, the disassembled Cotswold Cottage and its associated structures arrived at Greenfield Village. English contractor Cox-Howman sent two men, mason C.T. Troughton and carpenter William H. Ratcliffe, to Dearborn to help re-erect the house. Workers from Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant also came to assist. Reassembling the Cotswold buildings began in early July, with most of the work completed by late September. Henry Ford was frequently on site as Cotswold Cottage took its place stone-by-stone in Greenfield Village.

Before the English craftsmen returned home, Clara Ford arranged a special lunch at the cottage, with food prepared in the cottage’s beehive oven. The men also enjoyed a sight-seeing trip to Niagara Falls before they left for England in late November.

By the end of July 1930, the cottage walls were nearly completed. / THF148485

On August 20, 1930, the buildings were ready for their shingles to be put in place. The stone shingles were put up with copper nails, a more modern method than the wooden pegs originally used. / THF148497

Cotswold barn, stable, and dovecote, photographed by Michele Andonian. / THF53508

Free-standing dovecotes, designed to house pigeons or doves which provided a source of fertilizer, eggs, and meat, were not associated with buildings such as Cotswold Cottage. They were found at the homes of the elite. Still, for good measure, Ford added a dovecote to the grouping about 1935. Cutler made several plans and Ford chose a design modeled on a dovecote in Chesham, England.

Henry and Clara Ford Return to the Cotswolds

The Lygon Arms in Broadway, where the Fords stayed when visiting the Cotswolds. / THF148435, detail

As reconstruction of Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village was wrapping up in the fall of 1930, Henry and Clara Ford set off for a trip to England. While visiting the Cotswolds, the Fords stayed at their usual hotel, the Lygon Arms in Broadway, one of the most frequently visited of all Cotswold villages.

Henry (center) and Clara Ford (second from left) visit the original site of Cotswold Cottage, October 1930. / THF148446, detail

While in the Cotswolds, Henry Ford unsurprisingly asked Morton to take him and Clara to the site where the cottage had been.

Cotswold village of Stow-on-the-Wold, 1930. / THF148440, detail

At Stow-on-the-Wold, the Fords called on the families of the English mason and carpenter sent to Dearborn to help reassemble the Cotswold buildings.

Village of Snowshill in the Cotswolds. / THF148437, detail

During this visit to the Cotswolds, the Fords also stopped by the village of Snowshill, not far from Broadway, where the Fords were staying. Here, Henry Ford examined a 1600s forge and its contents—a place where generations of blacksmiths had produced wrought iron farm equipment and household objects, as well as iron repair work, for people in the community.

The forge on its original site at Snowshill, 1930. / THF146942

A few weeks later, Ford purchased the dilapidated building. He would have it dismantled, and then shipped to Dearborn in February 1931. The reconstructed Cotswold Forge would take its place near the Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village.

To see more photos taken during Henry and Clara Ford’s 1930 tour of the Cotswolds, check out this photograph album in our Digital Collections.

Cotswold Cottage Complete in Greenfield Village—Including Wooly “Residents”

Completed the previous fall, Cotswold Cottage is dusted with snow in this January 1931 photograph. Cotswold sheep gather in the barnyard, watched over by Rover, Cotswold’s faithful sheepdog. (Learn Rover's story here.) / THF623050

A Cotswold sheep (and feline friend) in the barnyard, 1932. / THF134679

Beyond the building itself, Henry Ford brought over Cotswold sheep to inhabit the Cotswold barnyard. Sheep of this breed are known as Cotswold Lions because of their long, shaggy coats and faintly golden hue.

Cotswold Cottage stood ready to welcome—and charm—visitors when Greenfield Village opened to the public in June 1933. / THF129639

By the Way: Who Once Lived in Cotswold Cottage?

Cotswold Cottage, as it looked in the early 1900s. From Old Cottages Farm-Houses, and Other Stone Buildings in the Cotswold District, 1905, by W. Galsworthy Davie and E. Guy Dawber. / THF284946

Before Henry Ford acquired Cotswold Cottage for Greenfield Village, the house had been lived in for over 300 years, from the early 1600s into the late 1920s. Many of the rapid changes created by the Industrial Revolution bypassed the Cotswold region and in the 1920s, many area residents still lived in similar stone cottages. In previous centuries, many of the region’s inhabitants had farmed, raised sheep, worked in the wool or clothing trades, cut limestone in the local quarries, or worked as masons constructing the region’s distinctive stone buildings. Later, silk- and glove-making industries came to the Cotswolds, though agriculture remained important. By the early 1900s, tourism became a growing part of the region’s economy.

A complete history of those who once occupied Greenfield Village’s Cotswold Cottage is not known, but we’ve identified some of the owners since the mid-1700s. The first residents who can be documented are Robert Sley and his wife Mary Robbins Sley in 1748. Sley was a yeoman, a farmer who owned the land he worked. From 1790 at least until 1872, Cotswold was owned by several generations of Robbins descendants named Smith, who were masons or limeburners (people who burned limestone in a kiln to obtain lime for mixing with sand to make mortar).

As the Cotswold region gradually evolved over time, so too did the nature of some of its residents. From 1920 to 1923, Austin Lane Poole and his young family owned the Cotswold Cottage. Medieval historian, fellow, and tutor at St. John’s College at Oxford University (about 35 miles away), Poole was a scholar who also enjoyed hands-on work improving the succession of Cotswold houses that he owned. Austin Poole had gathered documents relating to the Sley/Robbins/Smith families spanning 1748 through 1872. It was these deeds and wills that revealed the names of some of Cotswold Cottage’s former owners. In 1937, after learning that the cottage had been moved to Greenfield Village, Poole gave these documents to Henry Ford.

In 1926, Margaret Cannon Smith purchased the house, selling it in 1929 to Herbert Morton, on Henry Ford’s behalf.

“Olde English” Captures the American Imagination

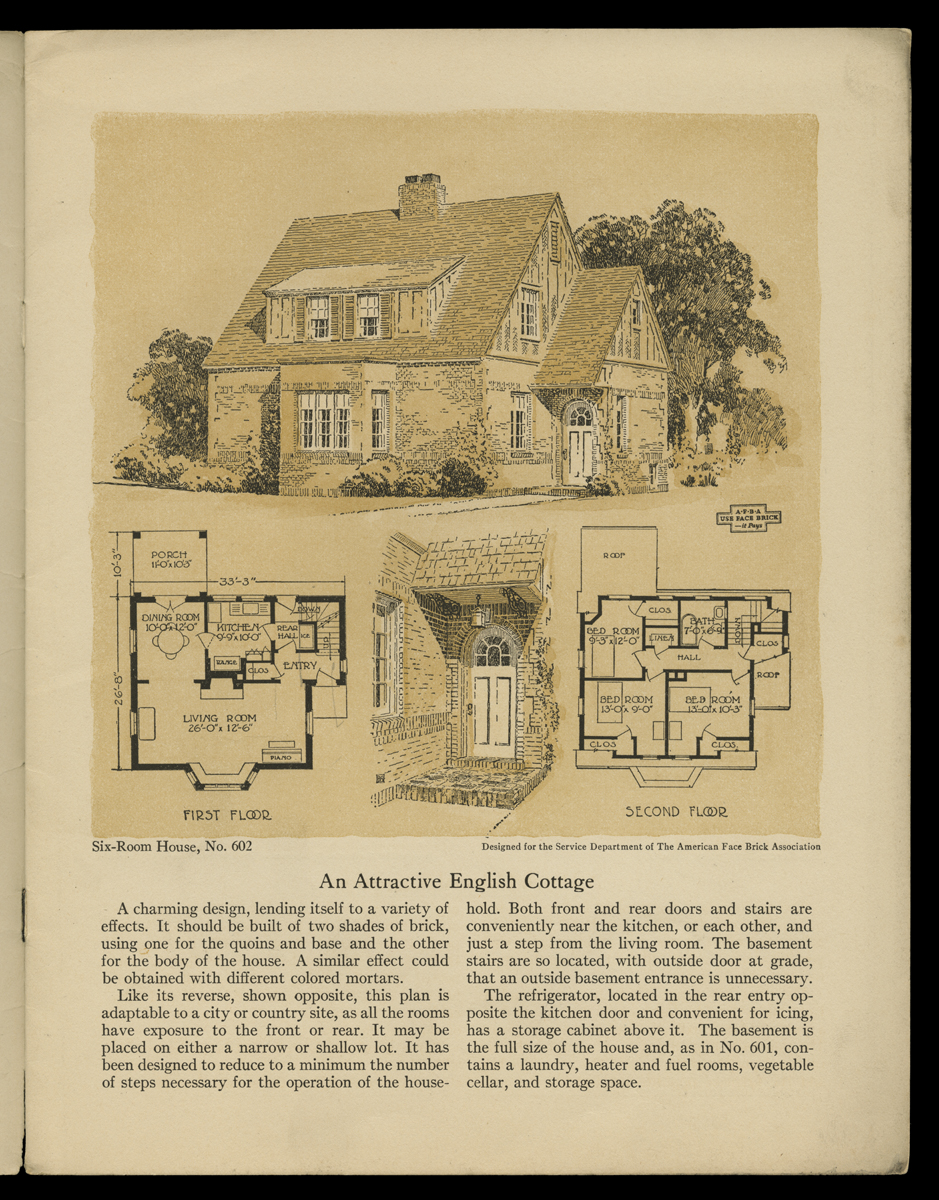

At the time that Henry Ford brought Cotswold Cottage to Greenfield Village, many Americans were drawn to historic English architectural design—what became known as Tudor Revival. The style is based on a variety of late Middle Ages and early Renaissance English architecture. Tudor Revival, with its range of details reminiscent of thatched-roof cottages, Cotswold-style homes, and grand half-timbered manor houses, became the inspiration for many middle-class and upper-class homes of the 1920s and 1930.

These picturesque houses filled suburban neighborhoods and graced the estates of the wealthy. Houses with half-timbering and elaborate detail were often the most obvious examples of these English revival houses, but unassuming cottage-style homes also took their place in American towns and cities. Mansion or cottage, imposing or whimsical, the Tudor Revival house was often made of brick or stone veneer, was usually asymmetrical, and had a steep, multi-gabled roof. Other characteristics included entries in front-facing gables, arched doorways, large stone or brick chimneys (often at the front of the house), and small-paned casement windows.

Edsel Ford’s home at Gaukler Pointe, about 1930. / THF112530

Henry Ford’s son Edsel and his wife Eleanor built their impressive but unpretentious home, Gaukler Pointe, in the Cotswold Revival style in the late 1920s.

Postcard, Postum Cereal Company office building in Battle Creek, Michigan, about 1915. / THF148469

Tudor Revival design found its way into non-residential buildings as well. The Postum Cereal Company (now Post Cereals) of Battle Creek, Michigan, chose to build an office building in this centuries-old English style.

Plan for “An Attractive English Cottage” from the American Face Brick Association plan book, 1921. / THF148542

Plans for English-inspired homes offered by Curtis Companies Inc., 1933. / THF148549, THF148550, THF148553

Tudor Revival homes for the middle-class, generally more common and often smaller in size, appeared in house pattern books of the 1920s and 1930s.

Sideboard, part of a dining room suite made in the English Revival style, 1925–1930. / THF99617

The Tudor Revival called for period-style furnishings as well. “Old English” was one of the most common designs found in fashionable dining rooms during the 1920s and 1930s.

Christmas card, 1929. / THF4485

Even English-themed Christmas cards were popular.

Cotswold Cottage—A Perennial Favorite

Cotswold Cottage in Greenfield Village, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF53489

Henry Ford was not alone in his attraction to the distinctive architecture of the Cotswold region and the English cottage he transported to America. Cotswold Cottage remains a favorite with many visitors to Greenfield Village, providing a unique and memorable experience.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Cotswold Cottage Tea

- Interior of Cotswold Cottage at its Original Site, Chedworth, Gloucestershire, England, 1929-1930

- Cotswold Cottage

home life, design, farm animals, travel, Henry Ford, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village, by Jeanine Head Miller

Driven to Win: Sports Car Performance Center

Jim Hall and Engineers at Chaparral Cars, Midland Texas, Summer, 1968. Hall pioneered some of the modern aerodynamic devices used on race cars. / THF111335

Anatomy of a Winner: Design. Optimize. Implement.

The Sports Car Performance Center section of our new racing exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America Presented by General Motors, is racing research and development on steroids. Passion and fortitude come standard.

The modern race shop encompasses a combination of scientific research, computer-aided design and engineering, prototyping, product development and testing, fabrication, and manufacturing. Here you can go behind the scenes to see how experts create winning race cars, using their knowledge in planning and problem-solving.

You can learn about key elements for achieving maximum performance through an open-ended exploration of components of the cars on display, as well as through other activities. STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) principles are a key focus here.

2016 Ford GT Race Car

(On loan from Ford Motor Company)

THF176682

This is the actual car that won the LMGTE Pro class at the 2016 24 Hours of Le Mans. The win was historic because it happened on the 50th anniversary of Ford’s first Le Mans victory in 1966, but over that half-century, racing technology advanced enormously, and the engine is half the size (a 3.5-liter, all-aluminum V-6 compared with a 7-liter, cast-iron V-8). But twin turbochargers (vs. naturally aspirated intake), direct fuel injection (vs. carburation), and electronic engine controls (vs. all mechanical) gave the GT engine almost 650 horsepower, versus slightly over 500 horsepower for the Mark IV.

Computer-aided design and engineering, aerodynamic innovations to maximize downforce and minimize drag, and electronic controls for the engine and transmission all combine to make the 2016 Ford GT a much more advanced race car, as you would expect 50 years on. The technology and materials advances in the GT’s brakes, suspension and tires, combined with today’s aerodynamics, make its handling far superior to its famous ancestor.

2001 C5-R Corvette

(On loan from General Motors Heritage Center)

THF185965

You can’t talk about American sports car racing without America’s sports car. The Chevrolet Corvette was in its fifth styling generation when the race version C5-R debuted in 1999. The Corvette Racing team earned 35 victories with the C5-R through 2004, including an overall victory at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 2001. This is the car driven by Ron Fellows, Johnny O'Connell, Franck Freon, and Chris Kneifel in that Daytona win.

Additional Artifacts

THF185968

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts related to sports car performance in Driven to Win.

Dig Deeper

Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon earned Ford its first win at Le Mans with the #2 GT40 on June 19, 1966. Ford celebrated that victory with another one on June 19, 2016—exactly 50 years later. / lemans06-66_083

Learn more about sports car performance with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Listen as Raj Nair, President and COO of Multimatic, and Henry Ford III, former Global Marketing Manager for Ford Performance, describe their experiences building, testing and racing the 2016 Ford GT—or watch a longer conversation with Raj Nair, Ford Performance’s Mark Rushbrook, and the driver who took the 2016 Ford GT on its final lap across the 24 Hours of Le Mans finish line, Joey Hand.

- Watch Jim Hall explain how he became one of the first to realize the advantages of utilizing aerodynamic downforce to help keep race cars on the road.

- Hear from Carroll Shelby on his approach to designing and building high-performance automobiles.

- Listen as Mario Andretti describes the mystique of the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

- Hear the story of Ford’s 1960s Le Mans campaign as told by Carroll Shelby, Dan Gurney, A.J. Foyt, and others.

- View the trophy given to Ford at Le Mans in 1966.

- See photos from Ford’s successful 1967 run at Le Mans.

- Learn how Bobby Unser developed a quick, inexpensive method of measuring airflow under race cars.

- 2012 Ford Fiesta Rally Car, Driven by Ken Block in "Gymkhana Five"

- National Hot Rod Association Top Fuel Competition Drag Racing Car, Driven by Gary Ormsby in the 1989 and 1990 NHRA Seasons, 1989

- 2018 Chevrolet Camaro ZL1 1LE. On Loan from General Motors Heritage Center.

- Barney Korn: Tether Car Craftsman

making, technology, cars, engineering, race cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, design, racing

Operating the Marionettes in Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little Marionette Show at the A.B. Dick Company Exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623950

The A.B. Dick Company, a major copy machine and office supply manufacturer, wanted to draw a crowd to its 1939 New York World’s Fair exhibition. The company decided that a musical marionette show, Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little, was just the ticket. A.B. Dick selected Tatterman Marionettes, a high-quality touring company managed by Edward H. Mabley (1906–1986) and William Duncan (1902–1978). Mabley wrote the musical comedy and Duncan produced the show, staged at the entrance to the A.B. Dick display in the Business Systems and Insurance Building.

A.B. Dick Company Mimeograph Exhibit and Writer’s Cramp Marionette Show at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623944

Writer’s Cramp featured changes in communication technology from “the days of the cave man” to the efficient modern office mimeograph machine. Marionettes represented Miss Jones, the secretary, and Mr. Whalen, the executive, trying to rush distribution of important correspondence. Father Time helped inform Mr. Whalen of his good fortune at present (1939) by escorting him through millennia of changes, starting with Stone Age stenographers, and including tombstone cutting, monks with their quill pens, and typists with their typewriters. The play culminated with the unveiling of A.B. Dick Company’s Model 100 Mimeograph, “the World’s Fairest writing machine!”

Writer’s Cramp: A Review in Little Marionette Show at the A.B. Dick Company Exhibit at the New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623948

Mabley and Duncan organized Tatterman Marionettes in Detroit, Michigan, in 1922, and had relocated to Cleveland, Ohio, by 1930. They established a reputation through high-quality performances to a range of audiences.

Panel 4 of promotional material, “A Modern Adult Program and a New Children’s Program for the Tatterman Marionettes,” 1931-1932 / THF623902

Edsel B. Ford contracted with the company to perform for children in his home during March 1931. At that time, the always entrepreneurial Mabley recommended his and Duncan’s product, Master Marionettes, as “unusual gift favors” for the children attending that show.

Master Marionettes: Professional Puppets for Amateur Puppeteers, 1930-1940 / THF623904

Tatterman Marionettes’ reputation grew through work with the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago in 1934, where the company presented 1,300 plays. More World’s Fair performances followed. A.B. Dick Company and General Electric both contracted with Tatterman to produce marionette performances during the 1939 World’s Fair. General Electric’s Mrs. Cinderella promoted electrification as part of the modernization of Cinderella’s drafty old castle. (Libby, McNeill & Libby also featured marionette performances, and other corporations staged puppet shows.)

The A.B. Dick Company spared no expense to ensure a first-class production. Tatterman provided the marionettes and experienced operators, while industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague (1883–1960) prepared blueprints for a detailed stage set. Teague’s exhibit work for A.B. Dick and several corporations during the 1939 World’s Fair helped solidify his reputation as “Dean of Industrial Design.” The company invested in a conductor’s score by Tom Bennett (1906–1970), who would go on to join NBC Radio as staff arranger and musical director after the World’s Fair.

With the script finalized (February 27, 1939), experienced operators put the marionettes to work. After the World’s Fair opened on April 30, 1939, they delivered programs on a set schedule published in official daily programs. On Sunday, October 22, 1939, for example, Tatterman Marionettes performed 15 shows—at 10:20, 11:00, and 11:40 in the morning; at 12:20, 1:00, 1:40, 2:20, 3:00, 3:40 in the afternoon; and at 5:40, 6:20, 7:00, 7:20, 8:00, and 8:20 in the evening.

“Brighten Up Your Days,” Song for the Writer’s Cramp Marionette Show, New York World’s Fair, 1939 / THF623906

At the end of each Writer’s Cramp performance, A.B. Dick mass-produced the feature tune using a mimeograph machine and photochemical stencil. Attendants distributed this sheet music, calling attention to the modern conveniences: “Just a moment, PLEASE! The young lady right behind you is running off some of the words and music from our show—they’re for you to take home with our compliments. Don’t go away without your copy!”

The Tatterman marionettes from Writer’s Cramp featured prominently in World’s Fair promotional material intended to draw the attention of office outfitters to the Business Systems and Insurance Building. Their little stage set conveyed big lessons to the hundreds of thousands of professionals who flowed through the A.B. Dick exhibit at the New York World’s Fair.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Thanks to Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, for editorial guidance.

New York, 20th century, 1930s, world's fairs, popular culture, music, design, communication, by Debra A. Reid, advertising

On July 3, 1981, the New York Times published an article that would send shockwaves through the LGBTQ+ community across the country. Headlined “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” the article, which appeared not on the first page, but on page A20, reported the death of eight individuals, and that the cause of the outbreak was unknown. For LGBTQ+ individuals living in the affected areas, the article was more a confirmation of their fears than new information. And for many heterosexual people, it sparked trepidation and deepened discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community. Other smaller publications had published articles in the months preceding July 1981, and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, from the U.S. Center for Disease Control (now known as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), documented early cases of the epidemic in June. In the gay community, friends and loved ones were getting sick and many were dying. The alarm bell had been rung.

The Silence = Death Collective designed this poster prior to the formation of the ACT UP organization, but transferred ownership to ACT UP in 1987. / THF179775

Silence = Death

The Silence = Death poster has come to symbolize the early fight against the AIDS epidemic. It was borne of deep grief and an unrelenting desire for action. One evening in late 1985, after the loss of his partner from AIDS in November 1984, Avram Finkelstein met with Jorge Socarras and Oliver Johnston in a New York City diner to catch up. Although the AIDS epidemic was a constant, tumultuous undercurrent in the gay community in the mid-1980s, the topic was often coded or avoided. That night, Finkelstein recalls, AIDS was all the men discussed, which he found “exhilarating after so many years of secrecy.” They decided to form a collective, each agreeing to bring one additional person to their next meeting. Chris Lione, Charles Kreloff, and Brian Howard joined. These six men met regularly to discuss the epidemic’s impact on their lives—and to process, rage, mourn, and, eventually, strategize. Finkelstein illustrates these meetings in his book After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images: “There were animated conversations, always, and there was often hilarity. We were almost never mean, but we frequently fought. There was shouting, there was fist pounding, and occasionally tears…. Fear may have been the canvas for our conversations. But anger was definitely the paint.”

These conversations turned to action. Each of the men had an artistic background—the group was comprised of art directors, graphic designers, and a musician. They decided to create a political poster, hoping to inspire action from the community’s fear. According to Finkelstein, “the poster needed to simultaneously address two distinctly different audiences, with a bifurcated goal: to stimulate political organizing in the lesbian and gay community, and to simultaneously imply to anyone outside the community that we were already fully mobilized.” The group spent six months designing the poster—debating everything from the background color to the text before deploying the poster all over Manhattan by March of 1987.

The poster’s central graphic element is a pink triangle. It references and reclaims the pink triangle patches on concentration camp uniforms that homosexual men were forced to wear by the Nazi regime during World War II (lesbian women were given a black triangle). The pink triangles subjected the men to added brutality. The poster’s triangle is inverted, however, from the one used during the Holocaust. This was initially a mistake. Chris Lione had recently been to the Dachau concentration camp and recalled that the pink triangle he saw on exhibit pointed upward. However, the collective embraced the accident once it was discovered, reasoning that the inverted triangle was “superimposing an activist stance by borrowing the ‘power’ intonations of the upwards triangle in New Age spirituality.” The expansive black background created a meditative negative space that further emphasized the bright pink triangle and the white text below.

The tagline for the poster—“SILENCE = DEATH”—was quickly developed. It also soon became the name of the men’s group: the Silence = Death Collective. The equation references the deafening silence of the public and government-at-large—the New York Times didn’t give the AIDS crisis front-page coverage until 1983; President Ronald Reagan’s administration made light of the epidemic in its early years (the administration’s press secretary jokingly referred to the epidemic as the “gay plague” in 1982); and President Reagan didn’t address the AIDS epidemic publicly until September of 1985. The tagline also targeted the LGBTQ+ community, whose uncomfortable silence came at ultimate risk. Without discussion, education, and action about the AIDS crisis, many more people would die. By the end of 1987, over 47,000 people had already died of AIDS. Silence—quite literally—equaled death.

Artist and activist Keith Haring designed this poster, titled “IGNORANCE = FEAR, SILENCE = DEATH Fight AIDS ACT UP,” in 1989 for the ACT UP organization. It utilizes the “Silence = Death” tagline and the inverted pink triangle symbol initially created by the Silence=Death Collective. / THF179776

The Formation of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power)

At almost the same time that the Silence = Death Collective’s poster began appearing around Manhattan, playwright and activist Larry Kramer gave a legendary lecture at New York’s Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center on March 10, 1987. Kramer famously began this speech by telling the crowd that half of them would be dead within the year (due to the AIDS epidemic). He repeatedly asked the crowd “What are you going to do about it!?!” Kramer’s rage and urgency pushed the crowd towards actionable steps to combat the AIDS crisis. Within days, a group met that would become the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—or ACT UP. Around 300 people attended that first meeting, including some of the members of the Silence = Death Collective.

ACT UP quickly mobilized and became the political action group that many in the LGBTQ+ community—including the Silence = Death Collective—had envisioned. ACT UP was (and still is) “committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” On March 24, 1987, just two weeks after Larry Kramer’s lecture, the group held its first “action” when it protested pharmaceutical price-gouging of AIDS medication on Wall Street. Kramer had published an op-ed in the New York Times the day before, titled “The FDA’s Callous Response to AIDS,” which helped contextualize ACT UP’s protest in the media. ACT UP and its many chapters, subcommittees, and affinity groups kept pressure on the government for its inaction in the AIDS epidemic by frequently staging creative acts of civil disobedience and nonviolent protest.