Posts Tagged engineering

Driven to Win: Sports Car Performance Center

Jim Hall and Engineers at Chaparral Cars, Midland Texas, Summer, 1968. Hall pioneered some of the modern aerodynamic devices used on race cars. / THF111335

Anatomy of a Winner: Design. Optimize. Implement.

The Sports Car Performance Center section of our new racing exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America Presented by General Motors, is racing research and development on steroids. Passion and fortitude come standard.

The modern race shop encompasses a combination of scientific research, computer-aided design and engineering, prototyping, product development and testing, fabrication, and manufacturing. Here you can go behind the scenes to see how experts create winning race cars, using their knowledge in planning and problem-solving.

You can learn about key elements for achieving maximum performance through an open-ended exploration of components of the cars on display, as well as through other activities. STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) principles are a key focus here.

2016 Ford GT Race Car

(On loan from Ford Motor Company)

THF176682

This is the actual car that won the LMGTE Pro class at the 2016 24 Hours of Le Mans. The win was historic because it happened on the 50th anniversary of Ford’s first Le Mans victory in 1966, but over that half-century, racing technology advanced enormously, and the engine is half the size (a 3.5-liter, all-aluminum V-6 compared with a 7-liter, cast-iron V-8). But twin turbochargers (vs. naturally aspirated intake), direct fuel injection (vs. carburation), and electronic engine controls (vs. all mechanical) gave the GT engine almost 650 horsepower, versus slightly over 500 horsepower for the Mark IV.

Computer-aided design and engineering, aerodynamic innovations to maximize downforce and minimize drag, and electronic controls for the engine and transmission all combine to make the 2016 Ford GT a much more advanced race car, as you would expect 50 years on. The technology and materials advances in the GT’s brakes, suspension and tires, combined with today’s aerodynamics, make its handling far superior to its famous ancestor.

2001 C5-R Corvette

(On loan from General Motors Heritage Center)

THF185965

You can’t talk about American sports car racing without America’s sports car. The Chevrolet Corvette was in its fifth styling generation when the race version C5-R debuted in 1999. The Corvette Racing team earned 35 victories with the C5-R through 2004, including an overall victory at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 2001. This is the car driven by Ron Fellows, Johnny O'Connell, Franck Freon, and Chris Kneifel in that Daytona win.

Additional Artifacts

THF185968

Beyond the cars, you can see these artifacts related to sports car performance in Driven to Win.

Dig Deeper

Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon earned Ford its first win at Le Mans with the #2 GT40 on June 19, 1966. Ford celebrated that victory with another one on June 19, 2016—exactly 50 years later. / lemans06-66_083

Learn more about sports car performance with these additional resources from The Henry Ford.

- Listen as Raj Nair, President and COO of Multimatic, and Henry Ford III, former Global Marketing Manager for Ford Performance, describe their experiences building, testing and racing the 2016 Ford GT—or watch a longer conversation with Raj Nair, Ford Performance’s Mark Rushbrook, and the driver who took the 2016 Ford GT on its final lap across the 24 Hours of Le Mans finish line, Joey Hand.

- Watch Jim Hall explain how he became one of the first to realize the advantages of utilizing aerodynamic downforce to help keep race cars on the road.

- Hear from Carroll Shelby on his approach to designing and building high-performance automobiles.

- Listen as Mario Andretti describes the mystique of the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

- Hear the story of Ford’s 1960s Le Mans campaign as told by Carroll Shelby, Dan Gurney, A.J. Foyt, and others.

- View the trophy given to Ford at Le Mans in 1966.

- See photos from Ford’s successful 1967 run at Le Mans.

- Learn how Bobby Unser developed a quick, inexpensive method of measuring airflow under race cars.

- 2012 Ford Fiesta Rally Car, Driven by Ken Block in "Gymkhana Five"

- National Hot Rod Association Top Fuel Competition Drag Racing Car, Driven by Gary Ormsby in the 1989 and 1990 NHRA Seasons, 1989

- 2018 Chevrolet Camaro ZL1 1LE. On Loan from General Motors Heritage Center.

- Barney Korn: Tether Car Craftsman

making, technology, cars, engineering, race cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, design, racing

New Racing Acquisitions at The Henry Ford

Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors.

The Henry Ford’s newest exhibition, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, opened to the public on March 27. It’s been a thrill to see visitors experiencing and enjoying the show after so many years of planning.

Along with all of that planning, we did some serious collecting as well. Visitors to Driven to Win will see more than 250 artifacts from all eras of American racing. Several of those pieces are newly acquired, specifically for the show.

Shoes worn by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five. Block co-founded DC Shoes in 1994. / THF179739

The most obvious new addition is the 2012 Ford Fiesta driven by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five: Ultimate Urban Playground; San Francisco. The car checked some important boxes for us. It represented one of America’s hottest current motorsport stars, of course, but it also gave us our first rally car. The Fiesta wasn’t just for show—Block drove it in multiple competitions, including the 2012 X Games in Los Angeles, where he took second place (one of five podium finishes Block took in the X Games series). At the same time, we collected several accessories worn by Block, including a helmet, a racing suit, gloves, sunglasses, and a pair of shoes. The footwear is by DC Shoes, the apparel company that Block co-founded with Damon Way in 1994.

Racing toys and games are prominently represented in Driven to Win. We have several vintage slot cars and die cast models, but I was excited to add a 1:64 scale model of Brittany Force’s 2019 Top Fuel car. Force is one of NHRA’s biggest current stars, and an inspiration to a new generation of fans.

Charmingly dated today, Pole Position’s graphics and gameplay were strikingly realistic in 1983. / THF176903

Many of those newer fans have lived their racing dreams through video games. We had a copy of Atari’s pioneering Indy 500 cartridge already, but I was determined to add newer, more influential titles to our holdings. While Indy 500 didn’t share much with its namesake race apart from the general premise of cars competing on an oval track, Atari’s Pole Position brought a new degree of realism to racing video games. Pole Position was a top arcade hit in 1982, and the home version, released the following year, retained the full-color landscapes that made the game so lifelike at the time. I was excited to acquire a copy that not only included the original box, but also a hype sticker reading “Arcade Hit of the Year!”

Another game that made the jump from arcade to living room was Daytona USA, released in 1995 for the short-lived Sega Saturn. Rather than open-wheel racing, Daytona USA based its gameplay on stock car competition. The arcade version was notable for permitting up to eight machines to be linked together, allowing multiple players to compete with one another.

More recently, the Forza series set a new standard for racing video games. The initial title, Forza Motorsport, featured more than 200 cars and encouraged people to customize their vehicles to improve performance or appearance. Online connectivity allowed Forza Motorsport players to compete with others not just in the same room, but around the world.

One of my favorite new acquisitions is a photograph showing a young racer, Basil “Jug” Menard, posing with his race car. There’s something charming in the way young Menard poses with his Ford, a big smile on his face and hands at his hips like a superhero. His car looks worse for the wear, with plenty of dents and an “85” rather hastily stenciled on the door, but this young driver is clearly proud of it. Menard represents the “weekend warrior” who works a regular job during the week, but takes on the world at the local dirt track each weekend.

When we talk about a racer’s tools, we don’t just mean cars and helmets. / THF167207

Drivers may get most of the glory, but they’re only the most visible part of the large team behind any race car. There are folks working for each win everywhere from pit lane to the business office. Engineers are a crucial part of that group, whether they work for the racing team itself, the car manufacturer, or a supplier. In the early 20th century, Leo Goossen was among the most successful racing engineers in the United States. Alongside designer Harry Miller, Goossen developed cars and engines that won the Indianapolis 500 a total of 14 times from 1922 to 1938. We had the great fortune to acquire a set of drafting tools used by Goossen in his work. The donor of those tools grew up with Goossen as his neighbor. As a boy, the donor often talked about cars and racing with Goossen. The engineer passed the tools on to the boy as a gift.

We could not mount a serious exhibit on motorsport without talking about safety. Into the 1970s, auto racing was a frightfully dangerous enterprise. Legendary driver Mario Andretti commented on the risk in the early years of his career during our 2017 interview with him. Andretti recalled that during the drivers’ meeting at the beginning of each season, he’d look around the room and wonder who wouldn’t survive to the end of the year.

Improved helmets went a long way in reducing deaths and injuries. Open-face, hard-shell helmets were common on race tracks by the late 1950s, but it wasn’t until 1968 that driver Dan Gurney introduced the motocross-style full-face helmet to auto racing. Some drivers initially chided Gurney for being overly cautious—but they soon came to appreciate the protection from flying debris. Mr. Gurney kindly donated to us one of the full-face helmets he used in occasional races after his formal retirement from competitive driving in 1970.

And speaking of Dan Gurney, he famously co-drove the Ford Mark IV to victory with A.J. Foyt at Le Mans in 1967. We have a treasure trove of photographs from that race, and of course we have the Mark IV itself, but we recently added something particularly special: the trophy Ford Motor Company received for the victory. To our knowledge, Driven to Win marks the first time this trophy has been on public view in decades. Personally, I think the prize’s long absence is a key part of the story. Ford went to Le Mans to beat Ferrari. After doing so for a second time in 1967, Ford shut down its Le Mans program, having met its goal and made its point. All the racing world had marveled at those back-to-back wins—Ford didn’t need to show off a trophy to prove what it had done!

Janet Guthrie wore this glove at the 1977 Indy 500—when she became the first woman to compete in the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. / THF166385

For most of its history, professional auto racing has been dominated by white men. Women and people of color have fought discrimination and intimidation in the sport for decades. It is important to include those stories in Driven to Win—and in The Henry Ford’s collections. We documented Janet Guthrie’s groundbreaking run at the 1977 Indianapolis 500, when she became the first woman to compete in America’s most celebrated race, with a glove she wore during the event. I quite like the fact that the glove had been framed with a plaque, a gesture that underlined the significance of Guthrie’s achievement. We’ve displayed the glove in the exhibit still inside that frame. More recently, Danica Patrick followed Guthrie’s footsteps at Indy. Patrick also competed for several years in NASCAR, and in 2013 she became the first woman to earn the pole position at the Daytona 500. She kindly donated a pair of gloves that she wore in 2012, her inaugural Cup Series season.

Wendell Scott, the first Black driver to compete full-time in NASCAR’s Cup Series, as photographed at Charlotte Motor Speedway in 1974. / THF147632

Wendell Scott broke NASCAR’s color barrier when he battled discrimination from officials and fans to become the first Black driver to win a Cup Series race. Scott earned the victory at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida, in December 1963. We acquired a photo of Scott taken later in his career, at the 1972 World 600. Scott retired in 1973 after sustaining serious injuries in a crash at Talladega Superspeedway. In addition to acquiring the photo, we were fortunate to be able to borrow a 1966 Ford Galaxie driven by Scott during the 1967 and 1968 NASCAR seasons.

Wendell Scott’s impact on the sport is still felt. Current star Darrell “Bubba” Wallace is the first Black driver since Scott to race in the Cup Series full-time. Following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, Wallace joined other athletes from all sports in supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. He and his teammates at Richard Petty Motorsports created a special Black Lives Matter paint scheme for Wallace’s #43 Chevrolet Camaro, driven at Virginia’s Martinsville Speedway on June 10, 2020. We acquired a model of that car for the exhibit. The interlocked Black and white hands on the hood are a hopeful symbol at a difficult time.

Our collecting efforts did not end when Driven to Win opened. We continue to add important pieces to our holdings—most recently, items used by rising star Armani Williams in his stock car racing career. There will be more to come: more artifacts to collect, more stories to share, and more insights on the people and places that make American racing special.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 20th century, women's history, video games, toys and games, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, engineering, Driven to Win, by Matt Anderson, African American history, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

"An Honest Effort": Claude Harvard and Ford Motor Company

“Speaking from my own experience, brief as it is, I feel certain that the man or woman who has put his very best into honest effort to gain an education will not find the doors to success barred.”

One of the few, if not the only, Black engineers employed by Henry Ford at the time, Claude had been personally sent to Tuskegee by Ford to showcase an invention of his own creation. Even in the face of societal discrimination, the message of empowerment and perseverance that Claude imparted on that day was one that he carried with him over the course of his own career. For him, there was always a path forward.

Claude Harvard practicing radio communication with other students at Henry Ford Trade School in 1930. / THF272856

Born in 1911, Claude spent the first ten years of his life in Dublin, Georgia, until his family, like other Black families of the time period, made the decision to move north to Detroit in order to escape the poor economic opportunities and harsh Jim Crow laws of the South. From a young age, Claude was intrigued by science and developed a keen interest in a radical new technology—wireless radio. To further this interest, he sold products door-to-door just so he could acquire his own crystal radio set to play around with. It would be Claude’s passion for radio that led him to grander opportunities.

At school in Detroit, Harvard demonstrated an aptitude for the STEM fields and was eventually referred to the Henry Ford Trade School, a place usually reserved for orphaned teen-aged boys to be trained in a variety of skilled, industrial trade work. His enrollment at Henry Ford Trade School depended on his ability to resist the racial taunting of classmates and stay out of fights. Once there, his hands-on classes consisted of machining, metallurgy, drafting, and engine design, among others. In addition to the manual training received, academic classes were also required, and students could participate in clubs.

Claude Harvard with other Radio Club members and their teacher at Henry Ford Trade School in 1930. / THF272854

As president of the Radio Club, Claude Harvard became acquainted with Henry Ford, who shared an interest in radio—as early as 1919, radio was playing a pivotal role in Ford Motor Company’s communications. Although he graduated at the top of his class in 1932, Claude was not given a journeyman’s card like the rest of his classmates. A journeyman’s card would have allowed Claude to be actively employed as a tradesperson. Despite this obstacle, Henry Ford recognized Claude’s talent and he was hired at the trade school. By the 1920s, Ford Motor Company had become the largest employer of African American workers in the country. Although Ford employed large numbers of African Americans, there were limits to how far most could advance. Many African American workers spent their time in lower paying, dirty, dangerous, and unhealthy jobs.

The year 1932 also saw Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company once again revolutionize the auto industry with the introduction of a low-priced V-8 engine. By casting the crankcase and cylinder banks as a single unit, Ford cut manufacturing costs and could offer its V-8 in a car starting under $500, a steal at the time. The affordability of the V-8 meant many customers for Ford, and with that came inevitable complaints—like a noisy rattling that emanated from the engine. To remedy this problem, which was caused by irregular-shaped piston pins, Henry Ford turned to Claude Harvard.

1932 Ford V-8 Engine, No. 1 / THF101039

To solve the issue, Harvard invented a machine that checked the shape of piston pins and sorted them by size with the use of radio waves. More specifically, the machine checked the depth of the cut on each pin, its length, and its surface smoothness. It then sorted the V-8 pins by size at a rate of three per second. Ford implemented the machine on the factory floor and touted it as an example of the company’s commitment to scientific accuracy and uniform quality. Along with featuring Claude’s invention in print and audio-visual ads, Ford also sent Harvard to the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago and to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to showcase the machine.

Piston Pin Inspection Machine at the 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago, Illinois. / THF212795

During his time at Tuskegee, Harvard befriended famed agricultural scientist George Washington Carver, who he eventually introduced to Henry Ford. In 1937, when George Washington Carver visited Henry Ford in Dearborn, he insisted that Claude be there. While Carver and Ford would remain friends the rest of their lives, Claude Harvard left Ford Motor Company in 1938 over a disagreement about divorcing his wife and his pay. Despite Ford patenting over 20 of Harvard’s ideas, Claude’s career would be forced in a new direction and over time, the invention of the piston pin sorting machine would simply be attributed to the Henry Ford Trade School.

Despite these many obstacles, Claude’s work lived on in the students that he taught later in his life, the contributions he made to manufacturing, and a 1990 oral history, where he stood by his sentiments that if one put in a honest effort into learning, there would always be a way forward.

Ryan Jelso is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Detroit, 1930s, 20th century, technology, radio, manufacturing, making, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, engines, engineering, education, by Ryan Jelso, African American history, #THFCuratorChat

The “F” Stands for “Fun”: Jerry Lawson & the Fairchild Channel F Video Entertainment System

Jerry Lawson, circa 1980. Image from Black Enterprise magazine, December 1982 issue, provided courtesy The Strong National Museum of Play.

In 1975, two Alpex Computer Corporation employees named Wallace Kirschner and Lawrence Haskel approached Fairchild Semiconductor to sell an idea—a prototype for a video game console code-named Project “RAVEN.” Fairchild saw promise in RAVEN’s groundbreaking concept for interchangeable software, but the system was too delicate for everyday consumers.

Jerry Lawson, head of engineering and hardware at Fairchild, was assigned to bring the system up to market standards. Just one year prior, Lawson had irked Fairchild after learning that he had built a coin-op arcade version of the Demolition Derby game in his garage. His managers worried about conflict of interest and potential competition. Rather than reprimand him, they asked Lawson to research applying Fairchild technology to the budding home video game market. The timing of Kirschner and Haskel’s arrival couldn’t have been more fortuitous.

A portrait of George Washington Carver in the Greenfield Village Soybean Laboratory. Carver’s inquisitiveness and scientific interests served as childhood inspiration for Lawson. / THF214109

Jerry Lawson was born in 1940 and grew up in a Queens, New York, federal housing project. In an interview with Vintage Computing magazine, he described how his first-grade teacher put a photo of George Washington Carver next to his desk, telling Lawson “This could be you!” He was interested in electronics from a young age, earning his ham radio operator’s license, repairing neighborhood televisions, and building walkie talkies to sell.

When Lawson took classes at Queens and City College in New York, it became apparent that his self-taught knowledge was much more advanced than what he was being taught. He entered the field without completing a degree, working for several electronics companies before moving to Fairchild in 1970. In the mid-1970s, Lawson joined the Homebrew Computer Club, which allowed him to establish important Silicon Valley contacts. He was the only Black man present at those meetings and was one of the first Black engineers to work in Silicon Valley and in the video game industry.

Refining an Idea

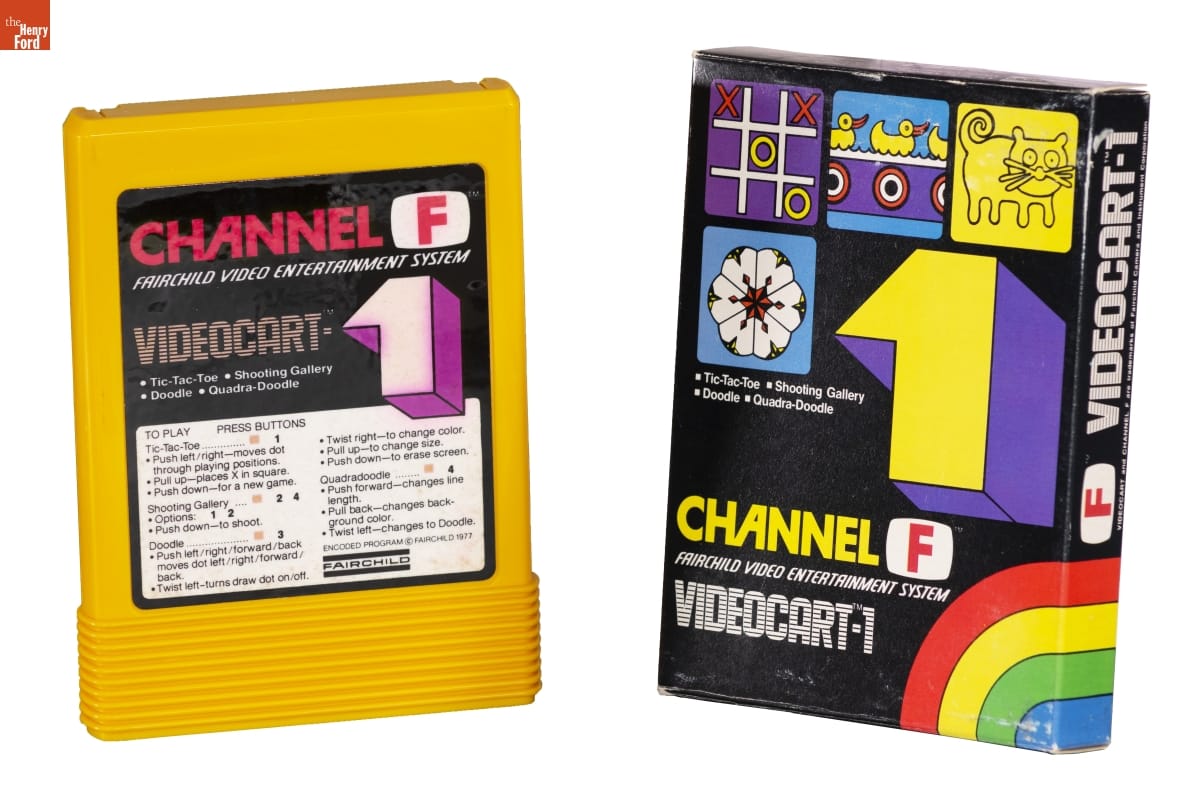

Packaging for the Fairchild Channel F Video Entertainment System. / THF185320

With Kirschner and Haskel’s input, the team at Fairchild—which grew to include Lawson, Ron Smith, and Nick Talesfore—transformed RAVEN’s basic premise into what was eventually released as the Fairchild “Channel F” Video Entertainment System. For his contributions, Lawson has earned credit for the co-invention of the programmable and interchangeable video game cartridge, which continues to be adapted into modern gaming systems. Industrial designer Nick Talesfore designed the look of cartridges, taking inspiration from 8-track tapes. A spring-loaded door kept the software safe.

A Fairchild “Video-Cart” compared to a typical 8-track tape. / THF185336 & THF323548

A Fairchild “Video-Cart” compared to a typical 8-track tape. / THF185336 & THF323548

Until the invention of the video game cartridge, home video games were built directly onto the ROM storage and soldered permanently onto the main circuit board. This meant, for example, if you purchased one of the first versions of Pong for the home, Pong was the only game playable on that system. In 1974, the Magnavox Odyssey used jumper cards that rewired the machine’s function and asked players to tape acetate overlays onto their television screen to change the game field. These were creative workarounds, but they weren’t as user-friendly as the Channel F’s “switchable software” cart system.

THF151659

Jerry Lawson also sketched the unique stick controller, which was then rendered for production by Talesfore, along with the main console, which was inspired by faux woodgrain alarm clocks. The bold graphics on the labels and boxes were illustrated by Tom Kamifuji, who created rainbow-infused graphics for a 7Up campaign in the early 1970s. Kamifuji’s graphic design, interestingly, is also credited with inspiring the rainbow version of the Apple Computers logo.

The Fairchild Video Entertainment System with unique stick controllers designed by Lawson. / THF185322

The Video Game Industry vs. Itself

The Channel F was released in 1976, but one short year later, it was in an unfortunate position. The home video game market was becoming saturated, and Fairchild found itself in competition with one of the most successful video game systems of all time—the Atari 2600. Compared to the types of action-packed games that might be found in a coin-operated arcade or the Atari 2600, many found the Channel F’s gaming content to be tame, with titles like Math Quiz and Magic Numbers. To be fair, the Channel F also included Space War, Torpedo Alley, and Drag Race, but Atari’s graphics quality outpaced Fairchild’s. Approximately 300,000 units of Channel Fun were sold by 1977, compared to several million units of the Atari 2600.

Channel F Games (see them all in our Digital Collections)

Around 1980, Lawson left Fairchild to form Videosoft (ironically, a company dedicated to producing games and software for Atari) but only one cartridge found official release: a technical tool for television repair called “Color Bar Generator.” Realizing they would never be able to compete with Atari, Fairchild stopped producing the Channel F in 1983, just in time for the “Great Video Game Crash.” While the Channel F may not be as well-known as many other gaming systems of the 1970s and 80s, what is undeniable is that Fairchild was at the forefront of a new technology—and that Jerry Lawson’s contributions are still with us today.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

1980s, 1970s, 20th century, New York, video games, toys and games, technology, making, home life, engineering, design, by Kristen Gallerneaux, African American history

Elijah McCoy’s Steam Engine Lubricator

Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882 / THF152419

You may have heard the saying, “The Real McCoy.” Popular belief often links the phrase to the high quality of a device patented by Black engineer Elijah McCoy.

Elijah McCoy was born on a farm in Canada to formerly enslaved parents. His father, George McCoy, had rolled cigars to earn the $1,000 required to buy his freedom. But money could not buy freedom for George’s love, Mildred “Millie” Goins, so George and Millie escaped her Kentucky master and became fugitives, settling in Colchester, Canada. They became farmers and had twelve children, including Elijah, born around 1844.

Elijah McCoy’s interest in machines led him to pursue formal study and an apprenticeship in engineering in Scotland. When he returned, he joined his family in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

Portrait of Elijah McCoy, circa 1895 / THF108432

But employers, blinded by racism, could not see his talent. Instead, in 1865, the Michigan Central Railroad offered McCoy the dangerous job of oilman and fireman. The need to constantly oil the moving parts of a locomotive AND shovel coal into the engine’s firebox soon sent him to the drawing board. In 1872, McCoy patented his own “improvement in lubricators for steam-engines,” the first of at least 52 patents and design registrations he secured during his lifetime.

For the next 40 years, McCoy patented many improvements for his automated oil-drip mechanism, updating his device as steam-engine design and operation changed. The steam engine lubricator cup pictured above (and on exhibit in Made in America in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation) resulted from improvements patented in 1882. Today, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office branch in Detroit bears his name, a fitting tribute to an innovator who moved locomotives—if not mountains.

This post was adapted from a stop on our forthcoming “Stories of Black Empowerment” tour of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in the THF Connect app, written by Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. To learn more about or download the THF Connect app, click here.

Made in America, Henry Ford Museum, THF Connect app, railroads, Michigan, making, engineering, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345, Used by Henry Ford. THF140104

In 1882, 19-year-old Henry Ford had an encounter with this little steam engine that changed his life. Though initially unsure of his abilities, he served as engineer, overseeing the maintenance and safe operation of the engine for a threshing crew organized by Wayne County, Michigan farmer John Gleason. He went on to run the engine for the rest of the season, developing the skills and knowledge of an experienced engineer. This assured Henry Ford that machines--not farming--were his future.

Pictured here with the steam engine are (left-to-right) Hugh McAlpine, James Gleason, and Henry Ford. This photograph was taken in 1920 on the Ford Farm in Dearborn. THF199289

Henry Ford never forgot this engine. Three decades later, as head of the world’s largest automobile company, he set out to find it again, sending representatives out scouring the countryside looking for the Westinghouse steam engine, serial number 345. Finally, one of his men found it in a farmer’s field in Pennsylvania. In 1912, Henry Ford purchased it from Carrolton R. Hayes, and had it completely rebuilt. Thereafter, Henry ran it regularly, often in the company of James Gleason, the brother of the man who originally bought it.

Read more content related to The Henry Ford's 90th anniversary here.

Additional Readings:

- Power by the Quarter

- Looking Back to Move Forward

- 1927 Plymouth Gasoline-Mechanical Locomotive

- Electrical Connection

Henry Ford Museum, farms and farming, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, engineering, engines, power, Henry Ford

Engineering a Bigger Dragon

Last year, Heavy Meta brought Canada's 30-foot long fire-breathing dragon across the U.S./Canada border to bring the heat to Maker Faire Detroit. Over the year that has passed, one thing that always irked us was the size of the dragon's wings. In the original sketch, the wings are supposed to be as tall as the head of the dragon! However, we had never been able to solve the engineering challenge this posed until now.

We are pleased to say that Detroit will be the first Maker Faire where attendees can check out our new wings! Here's how we did it.

Designing the Wings

We had two design goals:

1. Safely engineer a system that would allow the wings to be raised and lowered using some kind of mechanical winch.

2. Prevent the wings from rusting.

The first and second parts are related in a way, and the choice was made early on to work with aluminum to keep the wings light, as well as prevent corrosion.

To accomplish the first goal, we looked for other places where this problem has already been solved in an elegant fashion, and we found two "homologous structures" in the engineering world. One is in hydraulic excavating equipment, and the other, much simpler example is a straight razor.

A straight razor has a little handle for the thumb called a tang. It is the perfect length and shape to apply just the right amount of leverage to the spine to open the razor. We asked ourselves, what if instead of the handle, we had a wing stem, and what if instead of one spine, there were three spines, each supporting wing mesh?

With this in mind, we got our friend Ryan Longo at the Apocalypse Metal Shop to CNC plasma cut four large pieces of steel that mimicked the look of a straight razor and tang combo.

Matt decided inside each spine would need to be a strong piece of steel, we would create an aluminum façade to go over each "dragon finger."

Continue Readingevents, engineering, making, Maker Faire Detroit, by Kevin Bracken

Remembering Dan Gurney (1931-2018)

Dan Gurney at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, 1963. THF114611

The Henry Ford is deeply saddened by the loss of a man who was both an inspiration and a friend to our organization for many years, Dan Gurney.

Mr. Gurney’s story began on Long Island, New York, where he was born on April 13, 1931. His father, John Gurney, was a singer with the Metropolitan Opera, while his grandfather, Frederic Gurney, designed and manufactured a series of innovative ball bearings.

The Gurneys moved west to Riverside, California, shortly after Dan graduated high school. For the car-obsessed teenager, Southern California was a paradise on Earth. He was soon building hot rods and racing on the amateur circuit before spending two years with the Army during the Korean War.

Following his service, Gurney started racing professionally. He finished second in the Riverside Grand Prix and made his first appearance at Le Mans in 1958, and earned a spot on Ferrari’s Formula One team the following year. Through the 1960s, Gurney developed a reputation as America’s most versatile driver, earning victories in Grand Prix, Indy Car, NASCAR and Sports Car events.

His efforts with Ford Motor Company became the stuff of legend. It was Dan Gurney who, in 1962, brought British race car builder Colin Chapman to Ford’s racing program. Gurney saw first-hand the success enjoyed by Chapman’s lithe, rear-engine cars in Formula One, and he was certain they could revolutionize the Indianapolis 500 – still dominated by heavy, front-engine roadsters. Jim Clark proved Gurney’s vision in 1965, winning Indy with a Lotus chassis powered by a rear-mounted Ford V-8. Clark’s victory reshaped the face of America’s most celebrated motor race.

Simultaneous with Ford’s efforts at Indianapolis, the Blue Oval was locked in its epic battle with Ferrari at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Again, Dan Gurney was on the front lines. While his 1966 race, with Jerry Grant in a Ford GT40 Mark II, ended early with a failed radiator, the next year brought one of Gurney’s greatest victories. He and A.J. Foyt, co-piloting a Ford Mark IV, finished more than 30 miles ahead of the second-place Ferrari. It was the first (and, to date, only) all-American victory at the French endurance race – American drivers in an American car fielded by an American team. Gurney was so caught up in the excitement that he shook his celebratory champagne and sprayed it all over the crowd – the start of a victory tradition.

Just days after the 1967 Le Mans, Gurney earned yet another of his greatest victories when he won the Belgian Grand Prix in an Eagle car built by his own All American Racers. It was another singular achievement. To date, Gurney remains the only American driver to win a Formula One Grand Prix in a car of his own construction.

Dan Gurney retired from competitive driving in 1970, but remained active as a constructor and a team owner. His signature engineering achievement, the Gurney Flap, came in 1971. The small tab, added to the trailing edge of a spoiler or wing, increases downforce – and traction – on a car. Gurney flaps are found today not only on racing cars, but on helicopters and airplanes, too. In 1980, Gurney’s All American Racers built the first rolling-road wind tunnel in the United States. He introduced his low-slung Alligator motorcycle in 2002 and, ten years after that, the radical DeltaWing car, which boasted half the weight and half the drag of a conventional race car. Never one to settle down, Gurney and his team most recently were at work on a moment-canceling two-cylinder engine that promised smoother, more reliable operation than conventional power plants. Dan Gurney, 2008. THF56228

Dan Gurney, 2008. THF56228

Our admiration for Mr. Gurney at The Henry Ford is deep and longstanding. In 2014, he became only the second winner of our Edison-Ford Medal for Innovation. It was a fitting honor for a man who brought so much to motorsport, and who remains so indelibly tied to The Henry Ford’s automotive collection. Cars like the Ford Mark IV, the Mustang I, the Lotus-Ford, and even the 1968 Mercury Cougar XR7-G (which he endorsed for Ford, hence the “G” in the model name), all have direct links to Mr. Gurney.

We are so very grateful for the rich and enduring legacy Dan Gurney leaves behind. His spirit, determination and accomplishments will continue to inspire for generations to come.

Hear Mr. Gurney describe his career and accomplishments in his own words at our “Visionaries on Innovation” page here.

View the film made to honor Mr. Gurney at his Edison-Ford Medal ceremony below.

engineering, Mark IV, Indy 500, Le Mans, Europe, Indiana, California, New York, 21st century, 20th century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, in memoriam, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars, by Matt Anderson

Searching for Structural Integrity

One of the key aspects of the Dymaxion House in Henry Ford Museum is its central mast, which supports the entire structure. Buckminster Fuller, who created Dymaxion, had a lifelong interest in creating maximal structural strength with minimal materials and weight, most famously seen in his work with geodesic domes. When Fuller won his first commission for a geodesic structure, the Ford Rotunda, he worked with the Aerospace Engineering Lab at the University of Michigan to create a truss for load testing. Saved twice from being discarded by university staff, this test module was donated to The Henry Ford in 1993.

It’s newly digitized and available for viewing in our Digital Collections, along with many other artifacts related to geodesic domes, Buckminster Fuller, and the Dymaxion House.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

design, Michigan, Dearborn, Ford Motor Company, engineering, Buckminster Fuller, by Ellice Engdahl, digital collections

Garage Art

Photo by Bill Bowen.

Model T mechanics are restoration artists in their own right.

The Henry Ford has a fleet of 14 Ford Model T’s, 12 of which ride thousands of visitors along the streets of Greenfield Village every year.

With each ride, a door slams, shoes skid across the floorboards, seats are bounced on, gears are shifted, tires meet road, pedals are pushed, handles are pulled and so on. Makes maintaining the cars and preserving the visitor experience a continuous challenge.

“These cars get very harsh use,” said Ken Kennedy, antique vehicle mechanic and T Shed specialist at The Henry Ford. “Between 150,000 and 180,000 people a year ride in them. Each car gives a ride every five to seven minutes, with the longest route just short of a mile. This happens for nine months a year.”

The T Shed is the 3,600-square-foot garage on the grounds of Greenfield Village where repairs, restoration and maintenance magic happen. Kennedy, who holds a degree in restoration from McPherson College in Kansas, leads the shed’s team of staff and volunteers — many car-restoration hobbyists just like him.

“I basically turned my hobby into a career,” quipped Kennedy, who began restoring cars long before college. His first project: a 1926 two-door Model T sedan. “I also have a 1916 Touring and a 1927 Willys-Knight. And I’m working on a Model TT truck,” he added.

April through December, the shed is humming, doing routine maintenance and repairs on the Model T’s as well as a few Model AA trucks that round out Greenfield Village’s working fleet. “What the public does to these cars would make any hobbyist pull their hair out. Doors opening and shutting with each ride. Kids sliding across the seats wearing on the upholstery,” said Kennedy. Vehicles often go through a set of tires every year. Most hobbyist-owned Model T’s have the same set for three-plus decades.

With the heavy toll taken on the vehicles, the T Shed’s staff often makes small, yet important, mechanical changes to the cars to ensure they can keep up. “We have some subtle things we can do to make them work better for our purpose,” said Kennedy. Gear ratios, for example, are adjusted since the cars run slow — the speed limit in Greenfield Village is 15 miles per hour, maximum. “The cars look right for the period, but these are the things we can do to make our lives easier.”

In the off-season, when Greenfield Village is closed, the T Shedders shift toward more heavy mechanical work, replacing upholstery tops and fenders, and tearing down and rebuilding engines. While Kennedy may downplay the restoration, even the conservation, underpinnings of the work happening in the shed, the mindset and philosophy are certainly ever present.

“Most of the time we’re not really restoring, but you still have to keep in mind authenticity and what should be,” he said. “It’s not just about what will work. You have to keep the correctness. We can do some things that aren’t seen, where you can adjust. But where it’s visible, we have to maintain what’s period correct. We want to keep the engines sounding right, looking right.”

Photo by Bill Bowen.

RESTORATION IN THE ROUND

Tom Fisher, Greenfield Village’s chief mechanical officer, has been restoring and maintaining The Henry Ford’s steam locomotives since 1988. “It was a temporary fill-in; I thought I’d try it,” Fisher said of joining The Henry Ford team 28 years ago while earning an engineering degree.

He now oversees a staff with similarly circuitous routes — some with degrees in history, some in engineering, some with no degree at all. Most can both engineer a steam-engine train and repair one on-site in Greenfield Village’s roundhouse.

“As a group, we’re very well rounded,” said Fisher. “One of the guys is a genius with gas engines — our switcher has a gas engine, so I was happy to get him. One guy is good with air brake systems. We feel them out, see where they’re good and then push them toward that.”

Fisher’s team’s most significant restoration effort: the Detroit & Lima Northern No. 7. Henry Ford’s personal favorite, this locomotive was formerly in Henry Ford Museum and took nearly 20 years to get back on the track.

“We had to put on our ‘way-back’ hats and say this is what we think they would have done,” said Fisher.

No. 7 is one of three steam locomotives running in Greenfield Village. As with the Model T’s, maintaining these machines is a balance between preserving historical integrity and modernizing out of necessity.

“A steam locomotive is constantly trying to destroy itself,” Fisher said. “It wears its parts all out in the open. The daily firing of the boiler induces stresses into the metal. There’s a constant renewal of parts.”

Parts that Fisher and his team painstakingly fabricate, cast and fit with their sturdy hands right at the roundhouse.

DID YOU KNOW?

The No. 7 locomotive began operation in Greenfield Village to help commemorate Henry Ford’s 150th birthday in 2013.

Additional Readings:

- Ingersoll-Rand Number 90 Diesel-Electric Locomotive, 1926

- Keeping the Roundhouse Running

- Model Train Layout: Demonstration

- Part Two: Number 7 is On Track

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, trains, The Henry Ford Magazine, railroads, Model Ts, Greenfield Village, Ford Motor Company, engineering, collections care, cars, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford