Battle Creek’s Percy Jones General Hospital

Postcard of Percy Jones General Hospital, 1944. / THF184122

Postcard of Percy Jones General Hospital, 1944. / THF184122

When most people think of Battle Creek, Michigan, breakfast cereal comes to mind--the industry created there by “cereal” entrepreneurs W.K. Kellogg and C.W. Post at the turn of the 20th century.

Yet, Battle Creek was also home to an important World War II military medical facility, the Percy Jones General Hospital. By the end of the war, Percy Jones would become the largest medical installation operated by the United States Army. The hospital and its story are, perhaps, hidden in plain sight in a building now known as the Hart-Dole-Inouye Federal Center—unless one notices the historical marker located there.

Before a Hospital, a Sanitarium

Even before its genesis as Percy Jones, the site and its buildings had rich layers of use and history. In 1866, the Seventh Day Adventists established the Western Health Reform Institute in a cottage on the site to promote their principles of preventative medicine and healthful nutrition. In 1876, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (older brother of cereal entrepreneur W.K. Kellogg) became its director, renaming the facility the Battle Creek Sanitarium and expanding it to include a central building, a hospital, and other cottages. In 1902, a fire destroyed the sanitarium. An elegant, six-story Italian Renaissance style building soon rose in its place, completed in 1903. In 1928, the sanitarium was enlarged with a fifteen-story tower addition containing more than 265 hotel-like guest rooms and suites, most of which had private bathrooms. This expansive health and wellness complex on 30 acres could accommodate almost 1,300 guests. After the economy crashed in 1929, business declined. By 1933, the sanitarium went into receivership, and the Great Depression that followed forced the institution to sell assets to help pay its debt.

The 1903 sanitarium building. / THF620117

The sanitarium with its 1928 fifteen-story tower addition. / THF620119

Percy Jones Hospital Springs to Life

With the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939, the United States military began to build up its armed forces and medical treatment capabilities. In late 1940—in order to mobilize for what would become a growing need if the United States entered the war—the Medical Department began to develop a plan for providing a comprehensive system of progressive medical care from battlefield to stateside. A year later, with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States did enter the war. The military not only constructed new hospital facilities, but also acquired civilian buildings, making alterations and expanding as needed.

In August 1942, the United States Army purchased the near-vacant main Battle Creek Sanitarium building and converted it into a 1,500-bed military hospital, with crews working around the clock for six months to complete it. Dedicated on February 22, 1943, the hospital was named after Col. Percy L. Jones, a pioneering army surgeon who had developed modern battlefield ambulance evacuation during World War I. By the time the hospital opened—a little over a year after the United States entered the war—American troops had fought in the North Atlantic, North Africa, Italy, and the Pacific. Two and one-half more years of fierce fighting in Europe and the Pacific lay ahead. World War II—a global war which would directly involve 100 million people in more than 30 countries—would become the most costly and far-reaching conflict in history.

Percy Jones Hospital was one of the army’s 65 stateside General Hospitals, providing more complex medical or surgical care—those more difficult and specialized procedures requiring special training and equipment. Percy Jones Hospital specialized in neurosurgery, amputations and the fitting of artificial limbs, plastic surgery, physical rehabilitation, and artificial eyes. The Army’s rehabilitation program included physical conditioning and the constructive use of leisure time in educational pursuits to achieve the best possible physical and mental health for each convalescing soldier.

Percy Jones would become one of the army’s nine Hospital Centers, medical facilities that included both a General and Convalescent Hospital. Nearby (three miles from Battle Creek) Fort Custer, a military training base and activation point for Army inductees from Michigan and the Midwest, also served as the site of Percy Jones Convalescent Hospital for patients further along in the recovery process. In 1944, W.K. Kellogg’s summer mansion on nearby Gull Lake became a rehabilitation center for Percy Jones General Hospital and the Convalescent Center.

As the number of casualties increased, the facility grew—its authorized capacity would reach 3,414 beds. In one month alone, over 700 operations were performed. At the end of the war in August 1945, the number of patients at the hospital’s three area sites peaked at 11,427.

The massive Battle Creek hospital complex was self-contained and fully integrated. It had its own water supply and power generation, as well as a bank, post office, public library, and radio station. An indoor swimming pool and a bowling alley helped wounded vets regain their health. Rails and ramps were constructed throughout the facility. The Percy Jones Institute, an accredited high school, offered educational and training programs for patients, ranging from photography to agriculture to business.

Convalescing soldiers at Percy Jones Hospital in April 1944. The soldiers are wearing the Army-issued convalescent suits and bathrobes provided to patients at stateside hospitals. / THF270685

In August 1944, private Dean Stauffacher—training at nearby Fort Custer—sent the postcard at the top of this post (THF184122) of Percy Jones General Hospital to his wife, noting that “This is now an Army Hospital & is full of war casualties, etc.” This postcard was first published during the sanitarium era—the caption on the back dates from that period. Only the title on the front was updated to reflect the building’s use as a military hospital. / THF184123_redacted

Supporting the Troops at Percy Jones

People on the home front found ways to support the troops at Percy Jones. Hundreds of people visited soldiers daily. Celebrities Bob Hope, Jimmy Stewart, Ed Sullivan, Gene Autry, and Roy Rogers visited as well. Organizations provided snack food, reading material, and other gifts for the soldiers. Other groups organized social and recreational activities for convalescing soldiers.

A Ford Motor Company employee purchased two wheelchairs for Percy Jones Hospital with his muster out pay from the military, March 1944. / THF270681

In April 1944, Ford Motor Company employees gathered gifts of food (including candy and potato chips) and reading material for Percy Jones’ convalescing soldiers. / Four images above: THF270683, THF270699, THF270705, THF620569

Musical performances also provided entertainment for the convalescing soldiers. / THF620567

Detroit’s AFL/USO Committee organized a series of weekend social activities for servicemen from Percy Jones Hospital. Volunteer hostesses provided companionship for these soldiers during dinner, dancing, or a visit to local points of interest, as seen in the four images above: Program of social activities, April 1945; soldiers and hostesses gather for the day’s activities; visiting the Willow Run Bomber Plant near Ypsilanti, Michigan; enjoying dinner at the Federal Building in Detroit. / THF290072, THF211406, THF211408, THF289759

After a short deactivation period after World War II, the hospital reopened soon after the Korean War broke out in June 1950. Once again, wounded soldiers found medical treatment and emotional support at Percy Jones Hospital until the war’s end three years later.

A Lasting Legacy

With the end of the Korean War, the hospital closed permanently in 1953. But its legacy lived on in the lives of the nearly 95,000 military patients who received care at Percy Jones during World War II and the Korean War. And in the fact that Battle Creek became the first American city to install wheelchair ramps in its sidewalks, created to accommodate Percy Jones patients who visited downtown.

The hospital’s story would begin its fade from recent memory in 1954, as federal agencies moved into the building (now renamed the Battle Creek Federal Center)—only to reemerge (albeit subtly) in 2003. That year, the complex was renamed to honor three United States senators who had been patients at Percy Jones Hospital during World War II: Philip Hart of Michigan, Robert Dole of Kansas, and Daniel Inouye of Hawaii. The building’s new name honored the public service careers of these men—and also quietly reflected what Percy Jones Hospital and its staff had offered not only these World War II veterans, but tens of thousands of their fellow soldiers.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

1940s, 20th century, World War II, veterans, philanthropy, Michigan, healthcare, by Jeanine Head Miller

1956 Continental Mark II Sedan: “The Excitement of Being Conservative”

THF90723

In an era of extreme automotive styling, the Mark II was elegantly understated. Its advertising slogan, “the excitement of being conservative,” confirmed that Mark II’s appeal depended not on chrome, but rather on flawless quality control, extensive road testing, shocks that adjusted to speed, and power steering, brakes, windows, and seats. Not understated was the $10,000 price. Owned by VIPs like Frank Sinatra and Nelson Rockefeller, it was the most expensive American car you could--or couldn’t--buy.

William Clay Ford (left) reviews a clay model of the Mark II in 1953. He inherited a passion for styling from his father, Edsel Ford, and directed the Mark II’s design and development. / THF112905

The dashboard--luxurious in 1956--featured an instrument panel inspired by airplanes, with a pushbutton radio, watch-dial gauges, and throttle-style climate control levers. / THF113250

Like the car, advertising was understated. This Vogue magazine ad links the car with classic design in architecture and fashion. / THF83341

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

- The Henry Ford’s Tollbooths and the Cost of Good Roads

- 1981 Checker Marathon Taxicab

20th century, 1950s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, cars

1931 Bugatti Type 41 Royale Convertible: Unmatched Style and Luxury

THF90825

Longer than a Duesenberg. Twice the horsepower of a Rolls-Royce. More costly than both put together. The Bugatti Royale was the ultimate automobile, making its owners feel like kings. It is recognized as the epitome of style and elegance in automotive design. Not only did it do everything on a grander scale than the world’s other great luxury cars, it was also rare. Bugatti built only six Royales, whereas there were 481 Model J Duesenbergs and 1,767 Phantom II Rolls-Royces.

Ettore Bugatti formed Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. in 1909. His cars were renowned for their exquisite design and exceptional performance—especially in motor racing. According to lore, Bugatti was at a dinner party when a woman compared his cars unfavorably with those of Rolls-Royce. In response, he designed the incomparable Royale.

The Royale's elephant mascot was based on a sculpture by Rembrandt Bugatti, Ettore Bugatti's brother, who died in 1916. / THF90827

Because Bugatti Royales are so rare, each has a known history. This is the third Royale ever produced. Built in France and purchased by a German physician, it traveled more than halfway around the world to get to The Henry Ford. Here is our Bugatti’s story.

Joseph Fuchs took this 1932 photograph of his new Bugatti, painted its original black with yellow trim. His daughter, Lola, and his mechanic, Horst Latke, sit on the running board. /THF136899

1931: German Physician Joseph Fuchs orders a custom Royale. Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. builds the chassis in France. Its body is crafted by Ludwig Weinberger in Munich, Germany.

1933: Fuchs leaves Germany for China after Hitler becomes chancellor, taking his prized car with him.

1937: Japan invades China. Fuchs leaves for Canada—again, with his car. Having evaded the furies of World War II, Fuchs and his Bugatti cross Canada and find a home in New York City.

1938: A cold winter cracks the car’s engine block. It sits, unable to move under its own power, for several years.

1943: Charles Chayne, chief engineer of Buick, buys the Bugatti. He has it restored, changing the paint scheme from black and yellow to white and green.

1958: Now a General Motors vice-president, Chayne donates the Bugatti to Henry Ford Museum.

1985: For the first time, all six Bugatti Royales are gathered together in Pebble Beach, California.

The first-ever gathering of all six Bugatti Royales thrilled the crowds at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in 1985. They are the ultimate automotive expression of style and luxury. / THF84547

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- 1903 Oldsmobile Curved Dash Runabout

- Fozzie Bear’s 1951 Studebaker Commander

- 1956 Chevrolet Bel Air Convertible

- Mimi Vandermolen and the 1986 Ford Taurus

20th century, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, convertibles, cars

The Growth and Rebirth of the American Auto Show

The annual North American International Auto Show, a longtime January fixture in Detroit, made headlines this year by announcing a move to late September/early October. The shift promises warmer weather and less overlap with other events. It also offers an opportunity to reinvigorate a tradition that now competes against new marketing methods and sales opportunities driven by new technologies. With this big news in mind, we take a brief look at the history of auto shows through the collections of The Henry Ford.

“Kansas & Colorado State Building Interior,” Centennial Exhibition, 1876. Auto shows have roots in industrial expositions and world’s fairs held in the 19th century. Few were as impressive as Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exposition celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. / THF99942

Official Program, “Fifth National Exhibition of Cycles, Automobiles and Accessories,” 1900. Bicycle manufacturers staged trade shows in the late 19th century to showcase their latest models and attract new customers. Auto shows evolved naturally out of these events. This January 1900 New York show featured bikes and cars. / THF124095

Second Annual Show of Automobiles, Madison Square Garden, New York, November 1901. The November 1900 New York Auto Show was America’s first all-automobile show. Manufacturers displayed more than 30 different models in Madison Square Garden. This program is from the next year’s event. / THF288260_detail

Program, “6th Annual Boston Automobile Show,” March 7-14, 1908. Soon, every major American city staged its own annual show. For would-be car buyers, these events provided a chance to research new models, and compare features and prices across different manufacturers. / THF108049

Program, “Duquesne Garden 5th Annual Automobile Show,” Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, March 25-April 8, 1911. This program from Pittsburgh’s auto show reveals that, in 1911, cars were still thought of largely as playthings. Non-commercial automobiles were classed as “Pleasure Vehicles” at the event. / THF108051

Detroit Auto Dealers Association Eighteenth Annual Automotive Show Program, March 1919. Detroit’s auto show is among America’s oldest. World War I impacted the 1919 event. The show was delayed from January to March—giving time for automakers to shift back from war work to civilian production. / THF288268

Chrysler Thunderbolt, “It’s the ‘hit’ of the New York Show,” 1940-1941. Starting in the late 1930s, “concept cars” became star attractions at auto shows. These futuristic vehicles, like the Chrysler Thunderbolt, featured cutting-edge technologies and advanced designs. They remain mainstays today. / THF223319

Program, “The Automobile Salon,” New York City, 1920. After cars went mainstream, some shows continued to cater exclusively to wealthy buyers. New York’s 1920 Auto Salon featured posh marques like Cadillac, Lincoln, Packard, Benz, Hispano Suiza, and Rolls-Royce. / THF207760

General Motors Motorama of 1955. GM took auto shows to new heights with its traveling Motorama expos of 1949–61. The events spotlighted futuristic concept cars and aspirational production cars. Crowds lined up to see the dream cars on display. / THF288302

Electric Corvair at Detroit Automobile Show, 1967. New technologies are featured prominently. In 1967, Chevrolet showcased this fuel cell–powered electric Corvair. Some 50 years later, fuel cell cars still appear at shows—a futuristic technology whose time has yet to arrive. / THF103714

Program, “70th Annual Chicago Auto Show,” February 25 through March 5, 1978. Big auto shows benefit more than carmakers. Successful shows attract thousands of visitors, who spend money in restaurants, shops, and hotels. No wonder Chicago boasted its show as the “world’s greatest” in this 1978 program. / THF108058

Advertising Poster, “1990 North American International Auto Show.” For manufacturers, auto shows provide a chance celebrate both heritage and innovation. This 1990 Oldsmobile poster features past models as well as the then-new convertible Cutlass Supreme. / THF111496

Muppet Traffic Safety Show Sponsored by Plymouth, North American International Auto Show, 1990. Auto shows became family affairs with kids joining the fun. In 1990, Plymouth partnered with puppeteer Jim Henson on a traffic safety ride, featuring animatronic Muppet characters, at the North American International Auto Show. / THF256326

Automobiles and the Environment Conference at the 1998 Greater Los Angeles Auto Show. In the late 20th century, environmental concerns grew increasingly prominent at auto shows. This program is for a special environment-focused conference held in conjunction with the 1998 Los Angeles Auto Show. / THF288272

Auto Show Poster, “Detroit 2006: North American International Auto Show.” In the 21st century, traditional auto shows compete with flashy online presentations and press events. But NAIAS’s shift to fall promises new excitement for one of the automotive industry’s signature in-person events. / THF111553

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

1915 Brewster Town Landaulet: 20th-Century Technology, 19th-Century Comfort

THF91073

Wealthy Americans were familiar with the Brewster name because the company had been building elegant horse-drawn carriages for over 100 years. When Brewster finally began building automobiles in 1915, they looked like carriages. Chauffeurs dealt with the 20th-century auto technology—a quiet 55-horsepower engine, an electric starter, and electric lights—while owners rode in 19th-century carriage comfort. Tradition eventually lost out to the rush of modernity, and Brewsters began to look like cars.

Look closely at this 1890 Brewster landau carriage in The Henry Ford’s collection, and you’ll notice some similarities to the Brewster automobile. / THF80571

“Landaulet” is a car body style with separate compartments for passengers and driver. The passenger compartment is usually convertible. The driver’s compartment can be either enclosed or open. / THF206171

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

20th century, 1910s, luxury cars, horse drawn transport, cars

Dr. Howard, A Country Doctor in Southwest Michigan

Dr. Alonson B. Howard, Jr. in his early 40s, 1865–66 / THF109611

Since 1963, Greenfield Village has been home to the office of a country doctor named Alonson Bingley Howard, Jr. This modest, red-painted building was originally located near the village of Tekonsha, about 15 miles south of Marshall in south central Michigan. Back in 1855, Dr. Howard set up his medical practice inside this building, which had begun life as a one-room schoolhouse. After Dr. Howard’s death in 1883, his wife, Cynthia, padlocked the building with all its contents inside.

Interior of Dr. Howard’s office on its original site before its move to Greenfield Village, ca. 1956 / THF109609

There it remained, undisturbed, until the 1930s, when Dr. Howard’s great-grandson, Howard Washburn, began to take a deep interest in the building’s history. He not only sifted through his great-grandfather’s papers and medical books, but also collected reminiscences from those who still remembered him. Washburn was ultimately instrumental in the move of the building to Greenfield Village, which occurred between 1959 and 1961.

Dr. Howard’s office in its location in Greenfield Village since 2003. / THF1696

During a major renovation of Greenfield Village in 2003, Dr. Howard’s office was moved to its current location on the Village Green. The building’s history received new scrutiny and the interior was refurbished to the era of his medical practice in the early 1860s.

To prepare for a September 2020 filming of an episode of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, I had the opportunity to revisit and expand upon our knowledge of Dr. Howard’s background, medical practice, and the community within which he lived and worked. By looking at new sources and asking new questions, a more nuanced picture than ever before emerges.

Meet Dr. Howard

During the 1830s and 1840s, white settlement grew by leaps and bounds in southern Michigan. Those particularly prone to “emigration fever” at the time came from New England and upstate New York (following the path of the Erie Canal, completed in 1825). The emigration of the Howard family to Michigan followed a typical pattern of white settlement to the area.

Dr. Howard’s father, Alonson Howard Sr., ca. 1860 / THF237220

Alonson Howard Jr. was 20 years old when his family (parents and six siblings) emigrated from Sweden, New York (about 19 miles west of Rochester) to Michigan in 1843. The Howard family settled in Tekonsha Township, Calhoun County, Michigan. Alonson Sr., 45 years old at the time of his family’s emigration to Michigan, purchased farmland for all seven of his children. This farmland was located on a flat, heavily wooded plain of the St. Joseph River called the Windfall section (so named because of the “chaos” of fallen timber that had not been cleared). The family farm was appropriately named Windfall Farm.

The office can be seen at left, along the road in front of Windfall Farm, 1956 / THF237140

In 1844, Alonson Jr. married Letitia Cone (1823–57), whose family had emigrated to Michigan from upstate New York during the 1830s. They had three children: Ella (1846–48), Herbert (1849–63), and Truman (1852–1923). In the 1850 census, Alonson Jr. referred to himself as a farmer.

Dr. Howard’s wife, Cynthia, holding daughter Letitia (named after his first wife), 1865-66 / THF237222

Sadly, Alonson Jr.’s wife, Letitia, passed away in 1857. In August 1858, he married Cynthia Coryell Edmunds (1832 or 1833–99). Her family, originally from New England, had emigrated to Calhoun County in the 1830s by way of New York, Canada, and Ohio. According to family reminiscences, Cynthia was greatly loved by both family members and neighbors. She was “an easy housekeeper,” an excellent cook, a gentle, loving person, and an indulgent stepmother to Truman and Herbert. Family lore recounts she feared the Howard relatives might think she had been neglectful of Herbert when he tragically died of measles (a deadly infectious disease at the time) in 1863.

Alonson Jr. and Cynthia’s four children, ca. 1870. Front, left to right: Mattie, Camer, and Letitia; rear: Manchie / THF109605

Four children were born to Alonson Jr. and Cynthia: Manchie (1861–1921), Letitia (1864–1936), Mattie (1865–1940), and Camer (1868–1936). According to family history, both Manchie and Camer were named for Native American friends of their father.

Dr. Howard, ca. 1880 / THF228450

As the decades passed, Alonson Jr. seems to have increasingly chosen medical practice as a full-time occupation over farming. In the 1860 census, he was still listed as a farmer, but by 1870, he was listed as a physician and, in 1880, a physician and surgeon. He passed away on October 12, 1883, of arteriosclerosis (then called softening of the brain, now known as hardening of the arteries). There were no effective remedies for this at the time.

According to reminiscences, Dr. Howard was remembered fondly by many as an intelligent, dedicated, forceful, and vigorous man who could be blunt and abrupt with adults when he detected affectation or pretense. He had a keen sense of humor and a lifelong love of learning.

Dr. Howard’s Medical Practice

Physician’s folding stethoscope, ca. 1880 / THF152868

The unhealthiness of daily life in the mid-19th century may well be the most striking division between people’s lives in the past and how we live today. People did not yet realize the connection between unsanitary conditions and sickness. Nor did they understand the nature of germs and contagion and that diseases were transmitted this way.

As a result, infectious diseases were the leading causes of death at the time. These often reached epidemic proportions. Newborns might get infections of the lungs or the intestinal tract. Children were vulnerable to diphtheria, whooping cough, and scarlet fever, while the ordinary viral diseases of childhood—measles, mumps, and chicken pox—might turn deadly when followed by secondary bacterial infections. Adults might contract the life-threatening infectious diseases of cholera, typhoid fever, yellow fever, bacterial dysentery, pneumonia, malaria (or “intermittent fever”), and “the ague” (pulmonary tuberculosis, also called “consumption”). Women faced serious risks with repeated childbirths. Accidents were frequent killers; tetanus was a deadly threat.

Patent medicines, like these ca. 1880 Anti-Bilious Purgative Pills, were easily available, but they could contain dangerous, toxic, or habit-forming ingredients. / THF155683

American medicine was changing tremendously during the period in which Dr. Howard practiced, and approaches varied widely. Three types of medical practice vied for popularity: conventional (based upon the ancient Greek philosophy that the body’s system was made up of four circulating fluids or “humors”—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile); homeopathic (a rather controversial approach which asserted that whatever created a disease would also cure it); and botanic (which utilized natural materials such as herbs, plants, bark, roots, and seeds to cure the patient). Those who could not find or afford a local doctor might try an off-the-shelf patent medicine, a family remedy, or a recipe found in a book or periodical.

Invoice from 1881 to Dr. Howard, showing the variety of equipment and ingredients that he purchased from this Detroit company. / THF620460

Dr. Howard did not stick to one type of medical practice. Instead, he chose from all three prevailing approaches based upon what seemed to work best for each illness and patient. This type of approach, referred to as “eclectic,” was quite popular at the time. Like other country doctors, Dr. Howard not only treated patients with the usual illnesses, cuts, burns, and animal bites, but he also performed surgery, obstetrics, and dentistry. In addition, he made his own pills and remedies—decades before the pharmaceutical industry produced commercial drugs and the Food and Drug Administration was established to approve them.

A physician’s saddle bags, 1850-1870, used while visiting patients on horseback / THF166959

Although there were several physicians listed in local records, Dr. Howard’s account books list scores of patients who lived in Tekonsha Township and the surrounding countryside; larger towns like Marshall, Battle Creek, and Coldwater; and smaller communities like Jonesville, Burlington, and Union City. According to reminiscences, he was "out docktering" as much as he was in the office, “riding the circuit” from place to place around the region. He apparently visited patients during the week, sometimes staying overnight to tend the ill. He traveled by horse, and after 1870, by railroad. His office was open on weekends and story has it that, on those days, horses and buggies were lined up and down the road as patients awaited his services.

Native American Connections

No stories are more beloved in family lore than those that recount the friendship between Dr. Howard and the Native Americans who lived in the local area. According to reminiscences collected by Howard Washburn, Dr. Howard “cultivated a wide friendship with Indians at the Athens Reservation and learned how to use herbs and roots in treating illness.” Reference has already been made to the naming of two of his children after Native American acquaintances.

A page from Dr. Howard’s handwritten recipe book, 1864–68, reveals that his remedies included natural materials gathered from the local area. / THF620470

Washburn’s collection of reminiscences includes the following:

[Dr. Howard] used many roots and herbs, these were gathered for him from the woods on his farm and from around Nottaway Lake. He was friendly with the Pottawatomie [sic] Indians who had land there and over near Athens. He liked to have Indians gather herbs for him as they were more skilled and careful. Some of his recipes were Indian recipes and he had many friends in the tribe.

Charlie Hyatt of Tekonsha, who claimed to be part Indian, was living in 1950 and once called on us purposely to tell us that the Doctor had taught him the skill of herb gathering and had given him a book on herbs. He said that his mother was a Pottawatomie [sic] and that she and many others in the Tekonsha area supplemented their incomes by gathering herbs for Dr. Howard.

The photograph of these casks, taken in 1956 when the building was still in its original location, reveals the names of several extracts that Dr. Howard concocted for various remedies—many from plants and roots gathered in the local area. / THF109607

I became curious about these reminiscences because of the generally accepted—though, admittedly, white settler-based—perspective that the Potawatomi had virtually disappeared from the area by that time as a result of President Andrew Jackson’s notorious Indian Removal Act of 1830. These questions drove further research, ultimately leading to a richer, more substantive view of Potawatomi history in the area, Potawatomi-white settler connections, and conjecture about the friendship between Dr. Howard and local Potawatomi.

To make way for the ceaseless push of white settlement during the 1820s and 1830s, the U.S. government attempted to forcibly expel the Potawatomi from the area by means of a relentless series of treaties—totaling some 30 to 40 in all! A particularly significant one was the 1833 Second Treaty of Chicago, in which the U.S. government promised the Potawatomi new lands and annuity supplies in exchange for their removal over the next several years from southern Michigan (and portions of adjacent states) to reserved lands farther west (these lands and supplies were, for the most part, later reduced, delayed, or completely eliminated). At the time, the Potawatomi were told they could remain on their land until it was needed by white settlers, though much of the land had already been sold by then, as farmers and developers were eager to acquire land. Continued and renewed pressure for forcible removal of the Potawatomi persisted through the decade.

Not surprisingly, many Potawatomi were unwilling to relocate to unfamiliar territory farther west. Some fled to Canada, while others avoided relocation by taking refuge in remote places and becoming skilled at evading capture. Still others escaped north to join their “cousins”—the Odawa and Ojibway—in northern Michigan and Wisconsin.

When U.S. government agents finally left during the 1840s—assured that they had accomplished their task of successfully removing the Native Americans from the area—many Potawatomi quietly returned, unannounced and uncounted, to their old homes. The so-called Athens Reservation that is referred to in the Dr. Howard reminiscences is one such place. In 1845, with treaty annuity money, the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi purchased 80 (some sources say 120) acres on Pine Creek, near Athens, in Calhoun County. Influential chief John Moguago (1790–1863) led this effort. The band used the term “reservation” to denote land they had reserved for themselves, not land reserved for them by the U.S. government.

For the 2003 installation in Greenfield Village, many of the contents of Dr. Howard’s original jars and bottles were recreated from ingredients listed in his recipe book—including dried plants, herbs, roots, bark, and seeds that would have been collected in the local area. / THF11280

Potawatomi who stayed on or returned began settling in—working out means of remaining permanently in the area, finding places to live, and searching for ways to earn a livelihood. They found support among local white citizens, who were by this time secure in their ownership of the ceded Potawatomi lands. The Potawatomi worked aggressively to demonstrate their ability to live among Anglo-Americans—seeking alliances with white merchants and actively pursuing white settlers’ help in purchasing land with their annuity monies. Meanwhile, contact with white settlers did not fundamentally alter their subsistence economy of horticulture (corn, beans, and squash), hunting, fishing, and collecting wild plants for food and healing. This was likely the scenario around the time that Dr. Howard was practicing medicine and might explain his friendship with them.

The Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi is still going strong today. On December 9, 1995, after a long, emotional road, the band was finally recognized by the U.S. government as an independent nation with its own self-government. This recognition opened many avenues for them to take care of their people and continue to work toward a prosperous government. Today, their homeland headquarters are at the Pine Creek Indian Reservation (previously referred to as the Athens Reservation), but the band also maintains 300 additional acres of land adjacent to the Reservation, and satellite offices in Grand Rapids, where members live, as well as in Kalamazoo, Calhoun, Ottawa, Kent, and Allegan Counties.

Conclusion

These are just a few of the stories we have uncovered about this building in Greenfield Village and the country doctor who practiced medicine here back when the building was located in southwestern Michigan. We continue to engage in new research and uncover new stories about Dr. Howard, his practice, and his community.

- In 2013, several descendants of Dr. Alonson B. Howard Jr. made a pilgrimage to Greenfield Village to visit this building--read the story of their visit here.

- The web site of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi can be found here.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

19th century, Indigenous peoples, Michigan, healthcare, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Dr. Howard's Office, by Donna R. Braden

THF90312

The secret to this car’s striking look is a blend of English elegance and Italian aggressiveness. Late-1950s Rolls-Royces inspired the Riviera’s creased fenders and crisp roofline. But the Riviera leans forward, like a cat poised to pounce—or a Ferrari poised to win races. The tension between these approaches makes the Riviera one of the most memorable designs of the 1960s.

General Motors styling chief Bill Mitchell looked at Rolls-Royces, like this 1960 Silver Cloud II, for inspiration. They were modern without being trendy. THF84938

Many elements of this Ferrari 250 GT Pininfarina coupe slant forward to create an aggressive look. Can you see similarities between it and the Riviera? THF84932

Buick compared the car’s interior styling to that of an airplane, claiming the driver “probably feels more like a pilot” in the Riviera’s bucket seats. THF84935

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

“Pulp Fashion”: Paper Dresses of the 1960s

Another group of garments from The Henry Ford’s rich collection of clothing and accessories makes its debut in “What We Wore” in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Who knew that a company that made toilet tissue and paper towels would start a fashion sensation?

In April 1966, the Scott Paper Company launched a promotion for its new line of colorful paper products. Along with two proofs of purchase and $1.25 for shipping, customers could redeem a coupon for a paper dress, choosing from a red paisley bandana pattern or a black-and-white op art print.

The media took immediate notice. So did the public. Scott’s “Paper Caper” dresses became a surprise hit. Soon fashion enthusiasts were wearing not only Scott’s dresses, but paper apparel created by other manufacturers and designers who quickly joined in the trend.

The 1960s was an era of exploration and pushing boundaries. It was the space age--people envisioned an exciting future where everything was conveniently automated. New materials and disposability were in.

Paper apparel promised convenience--you could simply discard it after one wearing. Altering the hemline was a snap--all it took was a pair of scissors and a steady hand. A tear? You could do a quick repair with sticky tape.

The A-line shape and trendy prints of the paper dress fit perfectly with the youthful “Mod” look and aesthetic sensibilities of the 1960s. You could be up-to-the-minute at little cost--clothing could be quickly and cheaply replaced as trends shifted. There was a paper dress for every budget--from those on the shelves of mass-market retailer J.C. Penney to the chic creations carried by Manhattan boutiques.

People bought over a million paper garments between 1966 and 1968. Some envisioned throwaway clothing as the wave of the future. Yet, by early 1968, the craze was beginning to cool. Paper clothing was not really practical or comfortable for everyday use. And the hippie movement--with its back-to-nature values and strong anti-pollution message--was changing public opinion. What had seemed hip and modern now seemed frivolous and wasteful.

A bit of novelty in an era of experimentation, the paper dress fad was fun while it lasted.

The Dress That Launched a Fashion Craze

Scott Company’s “Paper Caper” Dress and label, 1966. / THF185279, THF146282

When the Scott Paper Company created the first paper dress in 1966, they intended it as a promotional gimmick to help sell their products. But their “Paper Caper” dresses--a paisley bandana design or an Op art print--swiftly and unexpectedly caught on with the public. The publicity the dresses brought Scott far exceeded the company’s expectations. By the end of the year they received nearly a half million orders for dresses they sold at near cost.

The company made little money from sales of the dresses--but that wasn’t the point. Inadvertent fashion innovators, company executives had no intention of continuing the paper dress venture in 1967, leaving the market to eager entrepreneurs.

Scott’s “Paper Caper” black and white Op art dress (geometric abstract art that uses optical illusion) appeared in Life Magazine in April 1966. / THF610489

“Waste Basket Boutique”

Paper Jumpsuit by Waste Basket Boutique by Mars of Asheville, 1966-1968. / THF185294 (Gift of the American Textile History Museum. Given to ATHM by Cathy Weller.)

The Scott company’s success started a trend for disposable fashion--so other companies quickly jumped in. Mars of Asheville, a hosiery company, launched a paper fashion line in June 1966 under the label, Waste Basket Boutique. They sold colorful printed-paper dresses and other garments for adults and children in a variety of strap, neckline and sleeve styles, as well as “space age” foil paper clothing. In September, Mars debuted plain white dresses that came with watercolor paint sets for “doing your own thing.” Pop artist Andy Warhol painted one to promote the new line.

Mars of Asheville became the leading manufacturer of disposable fashion, producing over 80,000 garments each week at its height.

Designers embraced the trend, creating unique disposable couture for a wealthier crowd. Tzaims Luksus designed these hand-painted $1000 balls gowns for an October 1966 fundraiser at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. Life Magazine, November 1966. / THF610492

Walking Ads/Walking Art

Campbell’s “Souper” Dress, 1967. / THF185289 (Given in Memory of Thelma D. Nykanen)

The advertising potential of these wearable “billboards” was huge. With coupons clipped from magazines, women could buy dresses from a variety of companies, including Green Giant vegetables, Butterfinger candy bars, and Breck hair care products. While some companies offered motifs that reflected their products, others followed fashion with flower power, paisley, or geometric designs.

In Spring 1967, the Campbell Soup Company produced what became the most famous paper garment of the era--this dress with its repeating soup can image. The dress not only advertised Campbell’s products--it also cleverly referenced Pop artist Andy Warhol’s iconic early 1960s depictions of the Campbell’s soup can that elevated this ordinary object to the status of art.

In 1968, the Mennen Company, makers of Baby Magic infant care products, offered women stylish paper maternity and party dresses “fashion-approved” by designer Oleg Cassini. / THF146023

Disposable Dresses Go Political

George Romney presidential primary campaign dress, 1968 / THF185284

Bumper stickers, buttons, and brochures--those were the standard things that political campaigns were made of in the 1960s. Beyond “standards,” campaigns also latch onto things that are hot at the time—and during the 1968 presidential campaign, that meant paper dresses. Democratic candidate Robert Kennedy and Republicans Richard Nixon, Nelson Rockefeller, and George Romney all had versions.

This George Romney campaign dress may have been “hip,” but it didn’t do the trick for him--Romney’s bid for the nomination was unsuccessful. Nelson Rockefeller’s too.

George Romney bumper sticker and campaign buttons, 1968. / THF146376, THF8545 (Buttons gift of Mr. & Mrs. Charles W. Kurth II)

When You Care Enough to WEAR the Very Best

Hallmark Cards, Inc. paper party dresses, “Flower Fantasy” and “Holly,” 1967. / THF185309 (Gift of the American Textile History Museum. Given to ATHM by Diane K. Sanborn), THF185307 (Gift of the American Textile History Museum. Given to ATHM by Jane Crutchfield)

In the spring of 1967, the Hallmark company embraced the disposable clothing trend, marketing a complete party kit that included a printed A-line shift and matching cups, plates, placemats, napkins, and invitations. While matched sets of disposable tableware had been around for decades, a matching paper dress was a new idea.

In this era of informal entertaining, festive paper tableware (and paper fashion) made hosting parties more convenient and cleanup easier. After guests left, the hostess could simply toss everything into the trash--rather than into the dishwasher and washing machine.

With Hallmark products, a hostess could have every element of her party perfectly matched--including her “swinging new paper party dress,” 1967. / THF146021

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1960s, What We Wore, popular culture, home life, Henry Ford Museum, fashion, by Jeanine Head Miller, advertising

1908 Stevens-Duryea Model U Limousine: What Should a Car Look Like?

THF90991

Early car buyers knew what motor vehicles should look like--carriages, of course! But automobiles needed things carriages didn’t: radiators, windshields, controls, horns, and hoods. Early automakers developed simple solutions. Brass, often used for carriage trim, was adopted for radiators, levers, and horns. Windshields were glass plates in wood frames. Rectangular sheet metal covers hid engines. The result? A surprisingly attractive mix of materials, colors, and shapes.

Although the Stevens-Duryea Company claimed its cars had stylish design, most early automakers worried more about how the car worked than how it looked. / THF84913

To build a car body, early automakers had to shape sheet metal over a wooden form. Cars made that way, like this 1907 Locomobile, often looked boxy. / Detail, THF84914

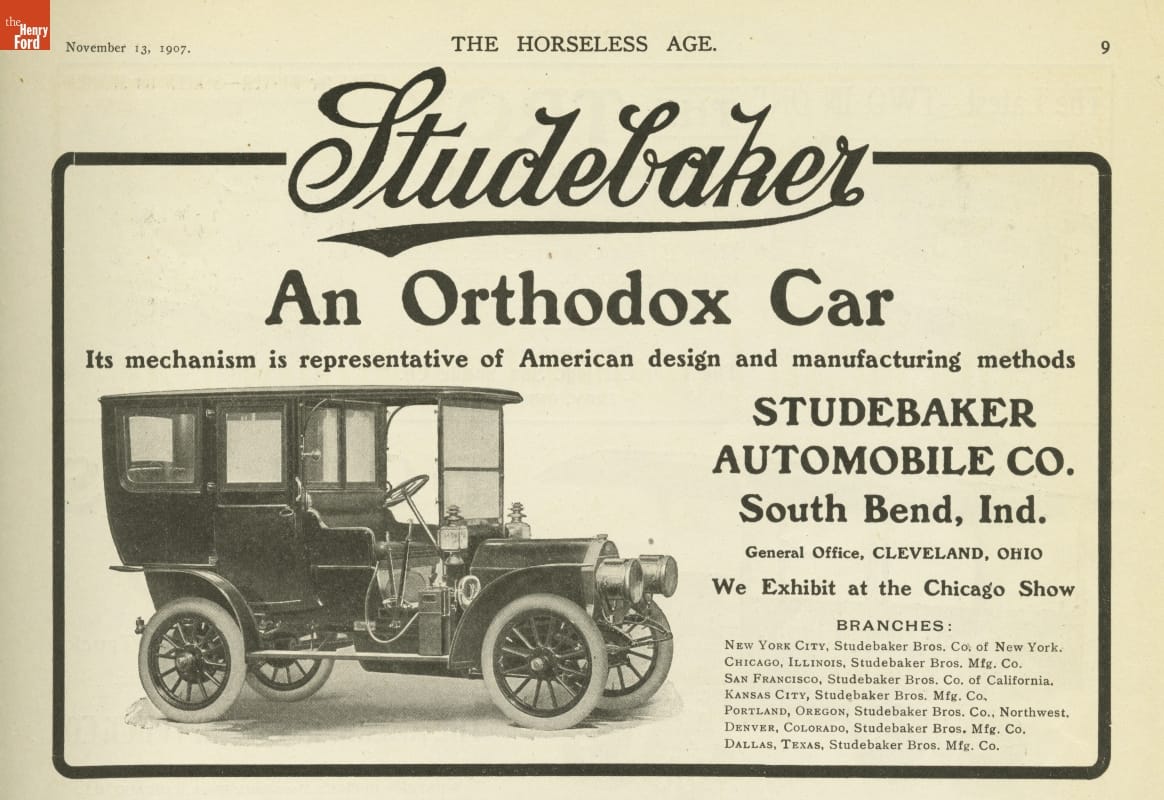

Some early automobiles looked good. But even the attractive ones looked like an assembly of parts, like the Studebaker shown in this 1907 ad. / THF84915

This post was adapted from an exhibit label in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Additional Readings:

- Women in the War Effort Workforce During WWII

- 2002 Toyota Prius Sedan: An Old Idea Is New Again

- 1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

- The First McDonald's Location Turns 80

20th century, 1900s, limousines, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, design, cars

Stories from the Initiative for Entrepreneurship

In 2019, The Henry Ford launched the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, an institution-wide initiative focused on providing resources and encouragement for the entrepreneurs of today and tomorrow. As Project Curator for the initiative, I have been working with other curators to identify entrepreneurial stories within our collections, select artifacts to be digitized, and research and write digital content to share these stories with the public. As this project comes to an end this month, I wanted to provide a wrap-up of all the entrepreneurial stories we’ve worked on.

The first six months of the initiative focused on entrepreneurial stories from our collecting themes of Agriculture and the Environment, and Social Transformation, but my first task was to determine what exactly we mean by “entrepreneurship.” Check out the blog post "Exploring Entrepreneurship," where I discuss what it means to be an entrepreneur.

The first collection I worked with was the H.J. Heinz Company Collection. Most people associate the Heinz name with ketchup, or even pickles, but the company’s first product was actually horseradish. Young Henry Heinz learned to prepare horseradish with his mother in their family home in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania, eventually selling the product to local housewives. In 1869, Heinz started his first official business selling horseradish out of his family home.

Product Label for Bottled Horseradish, Heinz & Noble, “Strictly Pure,” 1872 / THF117119

After initial success selling horseradish, Heinz’s company began selling other products like celery sauce and pickled cucumbers (pickles). Unfortunately, by 1875, the company went out of business, but Heinz learned from this failure and tried again. In 1876, Heinz persuaded family members to open a new company, F. &. J. Heinz, where Heinz could run the business behind the scenes while rebuilding his reputation. By 1888, Heinz had saved enough money to buy the company, renaming it the H.J. Heinz Company. To learn more about the rise of the H.J. Heinz Company, check out this Innovation Journeys Live! program where I discuss H.J. Heinz’s journey through the lens of our Model i habit “Learn from Failure.”

One characteristic of an entrepreneur is being a creative thinker. H.J. Heinz was a master of marketing, finding creative ways to advertise his products. With elaborate store displays and other strategies, the Heinz brand became a household name. In viewing advertisements and salesman catalogs, I learned about the many varieties of products that the H.J. Heinz Company produced. Did you know that Heinz sold heat-to-serve spaghetti and macaroni products? I sure didn’t!

Streetcar Advertising Poster for Heinz Spaghetti, circa 1930 / THF292241

H.J. Heinz recognized that the success of his business relied on his employees. Heinz was at the forefront of the employee welfare movement, offering amenities and conveniences for his workers, such as a swimming pool, gymnasium, and self-improvement classes.

Advertising Layout Photograph of Heinz Company Employee Swimming Pool and Baseball Team, circa 1912 / THF292794

One of my favorite parts of this job is that I have gotten to research individual artifacts and discover interesting facts about them. Ever wonder how we do this work? Check out the blog post "The Secret Life of a Heinz Recipe Book," where I discuss how we researched an employee recipe book found in the Heinz Collection. You can also check out the expert set "H.J. Heinz: His Recipe for Success," to learn more about H.J. Heinz’s entrepreneurial journey.

The next collection I examined was the Label Collection, and specifically, fruit and vegetable labels from the early produce industry. Labels distinguished one brand’s products from another and the artwork on them was meant to stand out and entice potential customers. Early product labels were made by a process called lithography, where skilled artists drew their images on flattened, smooth pieces of stone—traditionally limestone—to be inked and then transferred to paper via a printing press. The artists who worked in this medium are called lithographers. To learn more about lithography and the history of labels, click through to the post "Unpacking the History of Labels."

Crate Label, “Atlas Brand Fruit,” 1920-1930 / THF293961

Lithography companies created label designs for growers, packers, and distribution companies, often including a “signature” so others knew who created the design—like “Schmidt Litho. Co.” in the example below. Schmidt Lithograph Company was a recurring company name among the labels in the collection. I researched this company further and uncovered how Max Schmidt became one of the most well-known lithographers in the industry by 1900. Explore his entrepreneurial journey with the blog post "Max Schmidt: A Leader in Lithography."

Can Label, “Lynx Brand Puget Sound Salmon,” 1880-1890 / THF294341, THF294348

The Label Collection also tells the story of entrepreneurial companies that packaged and distributed produce. This led me to the story of Joseph Di Giorgio, founder of the Di Giorgio Fruit Corporation. Through research and reading oral history transcripts from Di Giorgio’s relatives and former employees, I discovered how hard work and determination led Di Giorgio to be known as “The Fruit King.” Learn more about his story by reading the blog post “'The Fruit King': Joseph Di Giorgio."

Crate Label, “Oh Yes! We Grow the Best California Fruits,” 1930-1940 / THF293029

This collection also gave me the opportunity to examine the entrepreneurial farmers who grew and harvested produce. For this, the Detroit Publishing Company Collection was extremely useful. From 1895 to 1924, the Detroit Publishing Company produced, published, and distributed photographic views from all over the world. Photographers captured special events and everyday activities, as well as views of cities and countryside. Photographs showing the harvesting and crating process, like this one of grapefruit being picked and crated for shipping, provided a unique look into the entrepreneurial farming industry.

Picking and Crating Grapefruit for Riverside Fruit Exchange, Riverside, California, circa 1905 / THF295680

To learn how these products and crops were marketed to and used by the general public, I delved into the Recipe Booklet Collection. Recipe booklets were a great source of marketing for companies, offering creative uses for products. With so many different companies represented in this collection, I was able to research the history of some of America’s well-known brands and compiled the expert set "Recipe Booklets from the Early 20th Century" so you can discover these histories. Within the booklets, you’ll also find recipes to try!

Recipe Booklet, “Kraft-Phenix Cheese Corp., Cheese and Ways to Serve It,” 1931 / THF294910

I found myself particularly drawn to the colorful and vibrant recipe booklets from the Jell-O Company. I was both delighted and surprised to find recipes ranging from beautiful and delicious-sounding creations to quirky and unusual flavor combinations (corned beef loaf, anyone?). Jell-O was first invented by Pearle Wait in 1897 when he combined fruit flavoring and sugar with gelatin powder. Unfortunately, Wait was unable to market the product, selling it to Orator F. Woodward two years later. By 1902, the Jell-O business was a quarter-million-dollar success. To learn more about this entrepreneurial enterprise, check out the blog post, “America’s Most Famous Dessert.”

Page from the recipe booklet, “Jell-O, America’s Most Famous Dessert,” 1916 / THF294400

The final step in the agricultural chain is public consumption, particularly in restaurants. In 2019, The Henry Ford acquired the largest collection of materials related to American diners, donated by leading diner expert Richard J.S. Gutman. Within the Gutman Diner Collection, photographs, trade catalogs, menus, and other items tell stories of innovation and entrepreneurship—from the craftspeople and designers who built the dining cars to the owners and operators who served customers every day. Learn more about the history of diners and how the industry embodies innovation and entrepreneurship in "Diners: An American Original," written by Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life Donna Braden.

Leviathan Grill, Newark, New Jersey, circa 1930 / THF296786

As part of the Initiative for Entrepreneurship, The Henry Ford launched an Entrepreneur in Residence (EIR) program. Melvin Parson, founder of We The People Grower’s Association and We the People Opportunity Farm, was our first EIR, participating in programs to encourage entrepreneurs in urban farming. Driven by his mission for equality and social justice, Farmer Parson uses vegetable farming as a vehicle to address social ills. He works to educate those in his community about farming and provides employment and training for individuals returning home from incarceration. You can view clips from the interview we did with Melvin Parson about his entrepreneurial journey at his urban farm in Ann Arbor in this expert set: "Melvin Parson: Market Gardener and Social Entrepreneur."

Melvin Parson during the Entrepreneurship Interview, 2019 / THF295361

This year, The Henry Ford and Saganworks, a technology start-up from Ann Arbor, Michigan, have partnered together to create a new virtual experience where people from around the world can interact with our digitized collections in a curated virtual space. What we created was a Sagan: a virtual room experienced like a gallery. The Henry Ford’s Entrepreneurship Sagan highlights the artifacts we digitized from the collections previously mentioned related to Agriculture and the Environment, and Social Transformation. To learn more about our Sagan you can watch this narrated walkthrough or read "Exploring Entrepreneurship, Virtually: The Henry Ford’s Sagan." You can also interact with an embedded version of the Sagan in this post: "Tour Our Entrepreneurship Sagan."

A view of the barn section of The Henry Ford’s Entrepreneurship Sagan, featuring items from the Detroit Publishing Company Collection, the Label Collection, and Melvin Parson’s EIR program. (Photo courtesy of Samantha Johnson)

The second six months of the Initiative for Entrepreneurship focused on our collecting themes of Design & Making, and Communications & Information Technology. The first entrepreneurial story I delved into here was the Everlast Metal Products Corporation. Experienced metalworkers and brothers-in-law Louis Schnitzer and Nathan Gelfman immigrated to the U.S. and entered the silver housewares business in the early 1920s. Soon, the Great Depression caused them to turn to a more affordable metal: aluminum.

Everlast Aluminum Advertisement, “Yours from Everlast, the Finest—Bar None!” 1947 / THF125124

In 1932, the pair formed Everlast Metal Products Corporation and began producing high-quality, hand-forged aluminum giftware. In an era of growing uniformity via factory production, the “made by hand” products (like this bowl) held an aesthetic appeal for consumers. Even with its initial success, by the 1950s, aluminum housewares were seen as old-fashioned compared to consumer interests in materials like ceramics and plastics. As an attempt to reinvent its products, Everlast produced a line of “modern” giftware, like coasters. If I could choose any Everlast piece to use at my house, it would definitely be this three-tier tidbit tray from the “modern” line.

Everlast “Modern” Three-Tier Tidbit Tray, 1953 / THF125116

Despite attempts to modernize, advances in technology and rapidly changing consumer interests led to the downfall of the aluminum industry. Schnitzer and Gelfman’s entrepreneurial journey ended in 1961 but they experienced undeniable success in Everlast’s 30-year history. Interested in learning more about this company? Check out "Forging an Enterprise: Everlast Aluminum Giftware," or click here to view over 100 items from our collection of Everlast products.

Everlast “Bali Bamboo” Condiment Set, 1948-1959 / THF144270

The next collection I worked with was the Trade Card Collection, filled with all kinds of entrepreneurial stories. As color printing became popular in the late 19th century, trade cards became a major means of advertising goods and services to potential customers. Cheap and effective, trade cards promoted products like medicine, seeds, food, stoves, sewing machines, and notions. Americans often saved these little advertisements found in product packages and distributed by local merchants

Trade Card for John Kelly’s Fine Shoes, 1879-1890 / THF296402

Companies employed a variety of methods to make their trade cards stand out, like using vibrant colors or endearing images. One of the most popular image themes throughout our collection, and Victorian trade cards in general, is the depiction of children (for example, in this trade card for Ayer’s Sarsaparilla). Another common theme is cute – and sometimes silly – animals. Something about the expressions on these dogs reading the newspaper always makes me laugh.

Trade Card for the Standard Rotary Shuttle Sewing Machine, Standard Sewing Machine Co., 1891-1900 / THF296692

I found trade cards that offered an optical illusion especially intriguing. When you hold this card up to a light, the woman’s eyes appear open and the logo for the company’s Garland Stoves and Ranges appears in the open window. But my absolute favorite trade card is the one below, for Nick Pettine’s tuxedo rental and tailoring service. These two figures came in an envelope. They are the same size when placed side-by-side (see first image), but when you put one figure’s nose on the collar of the other, one appears smaller!

Mr. Smyley and Mr. Happy’s Optical Illusion Trade Card for Nick Pettine Tuxedo Rentals, 1924 / THF298632, THF298633

I was born and raised in Grand Rapids, Michigan, so I was excited to have the opportunity to research early Grand Rapids companies found within the Trade Card Collection, which you can check out in the expert set "Trade Cards from Early Grand Rapids Businesses." To learn about other entrepreneurial companies represented in the Trade Card Collection, check out "Trade Cards Catch the Eye."

While researching the trade cards, I became fascinated with the story behind one particular entrepreneurial company: the Larkin Company. In 1875, John D. Larkin established a soap manufacturing company. Its first salesman, Elbert Hubbard, adopted a marketing strategy to offer a premium (a free giveaway) with the purchase of a product such as Boraxine.

Trade Card for “Boraxine” Soap, J.D. Larkin & Co., 1882 / THF296328

By 1883, as the company’s product line expanded, finer premiums were offered, such as silver-plated eating utensils. Larkin & Hubbard saw this promotion’s potential. They eliminated middlemen (including the salesforce) and entered the mail-order industry. In 1885, Hubbard developed “The Larkin Idea,” incorporating his promotion of offering giveaways with purchases into mail-order catalogs. The money saved by eliminating middlemen went towards creating desirable premiums available to customers with purchases. By 1910, product offerings expanded to include foodstuffs, clothing, and housewares, with over 1,700 premiums to choose from, ranging from children’s toys to clothing to furniture. This cover from a 1908 catalog advertises “stylish wearing apparel given as premiums.”

Cover for Larkin Company Catalog, “Stylish Wearing Apparel Given as Premiums with the Larkin Products,” Spring/Summer 1908 / THF297766

While looking through Larkin catalogs, I was amazed at all of the product and premium offerings and the fact that you could literally furnish your entire house with Larkin premiums. I was most shocked to find this premium: a singing canary! However, despite tremendous success, by the mid-1920s, the company was faltering, making the decision to stop manufacturing products and premiums in 1941. However, due to an abundance of inventory, the company was still able to fill orders until 1962. To learn more about this incredible story, check out “The Larkin Idea.”

Page from Larkin Company Trade Catalog, “The World’s Greatest Premium Values, Larkin Co. Inc.,” Fall and Winter 1930 / THF298067

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, we were digitizing some of the materials The Henry Ford acquired in 2017 from the now closed American Textile History Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts. (Read more about this acquisition in the blog, "Collecting in the 2010s", under the “Throstle Spinning Frame” entry.) In the collection are many sample books from various companies—records of fabrics produced by that manufacturing company within a given year or season. They are strikingly beautiful, offering a glimpse of the evolution of fabrics and patterns over time. This book from the Cocheco Manufacturing Company in New Hampshire, for example, notes the date (1880), fabric, and pattern information, and the page below is from the Fall 1927 sample book for Lancaster Mills’ “Klinton Fancies.”

Page from Sample Book for Lancaster Mills, “36 Inch Klinton Fancies,” Fall 1927 / THF299920

I wasn’t sure what patterns or colors I was going to find in these sample books, but I was completely surprised when I saw this one from Hamilton Manufacturing Company from 1900. These colors are so vibrant and the patterns seem so modern. Beyond the zigzag pattern below, it contains what look like modern-day animal prints, and printed patchwork that resembles a pieced quilt pattern, similar to a crazy quilt. Crazy quilts consist of fabric of irregular shapes and sizes sewn onto a backing, with decorative embroidery patterns covering the seams. These fabrics gave you the look of a crazy quilt—without all the effort.

Page from Sample Book for Hamilton Manufacturing Company, April 9, 1900 to May 27, 1901 / THF600027

In addition to sample books, we also had the opportunity to digitize product literature from the American Textile History Collection. To see more of the sample books and product literature we digitized, check out "'Sampling' the Past: Fabrics from America's Textile Mills."

The next collection I researched, the Burroughs Corporation Collection, is related to the Communications & Information Technology theme. This company might sound familiar to those in the Detroit area, as Burroughs had its main plant in Plymouth, Michigan. William S. Burroughs was a banker who wanted to ease the work of figuring mathematical calculations by hand. His solution led to his patented adding machine and the creation of his company in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1886, first known as the American Arithmometer Company.

Advertisement for the Burroughs Adding Machine Class 1, 1901-1907 / THF299361

By 1904, the company had outgrown its St. Louis facility, moving operations to Detroit. In 1905, it became the Burroughs Adding Machine Company, and by the 1930s had over 450 models of manual and electric calculation devices, bookkeeping machines, and typewriters.

Burroughs Complete Product Line, 1949 / THF199108

The company’s focus shifted in the 1950s to include defense and space research, banking and business technology, and advanced computer and electronics research. To reflect this diversification, the company was renamed Burroughs Corporation in 1953. Having contracted with the National Defense Program during WWII, Burroughs was awarded additional government and defense contracts throughout the 1960s. A Burroughs transistorized guidance computer was deployed to launch the Mercury and Gemini space flights.

Project Mercury Guidance Computer, 1959-1963 / THF299110

One of my favorite artifacts from the Burroughs Collection is this copy of a custom “baby calculator” presented to Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. They made two calculators for the Queen’s children, Ann and Charles. This blue one was made for Charles (note the “C” on the front). On the inside of the case, you can see the Royal Stewart tartan, the personal tartan plaid of the Queen.

Copy of a Custom “Baby Calculator” Presented to Queen Elizabeth II for Prince Charles, 1953 / THF170191

From the adding machine to office equipment to computers that helped to send people into space, the Burroughs Corporation adhered to its founding principles – to respond to human problems with relevant technologies. Learn more about the company (now Unisys) by reading “Wherever There’s Business There’s Burroughs.”

The Fall 2019 Entrepreneur in Residence was Rich Sheridan, CEO and co-founder of Menlo Innovations, a software development company. Sheridan is known for his unique approach to the office environment, emphasizing teamwork and encouraging joy in the workplace. During an interview, Sheridan shared how visits to Greenfield Village—specifically Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park lab—sparked an idea to re-imagine the software industry’s work environment in a similar way to how Edison ran his lab. Listen to Sheridan talk about this in the clip, “Creating Menlo Innovations.” You can also check out Sheridan’s entire interview in the expert set "Rich Sheridan: Re-imagining Workplace Culture."

Video screenshot of Rich Sheridan, 2019 / THF600469

The third phase of the Initiative for Entrepreneurship was dedicated to the collecting themes of Power & Energy, and Mobility. Unfortunately, the pandemic curtailed our ability to digitize new materials, but we were grateful to have completed the digitization project for one mobility-related entrepreneur story before we were quarantined: the story of McKinley Thompson, Jr.

Photograph of McKinley Thompson, Jr., undated (Photograph Courtesy of McKinley Thompson, Jr.)

Thompson broke barriers by being the first African American to attend the prestigious Art Center School of Design in Los Angeles for automotive design (having won a scholarship to the school as the grand prize in a design contest). After graduating, Thompson was hired by Ford Motor Company to work in its Advanced Styling Studio, breaking another barrier to become the first African American automobile designer. There he contributed to concept cars like the Allegro and Gyron, and he collaborated on production vehicles like the Mustang and Bronco. While at Ford, Thompson recognized the important role mobility played in the growth of developing nations. Specifically, Thompson believed an affordable, reliable vehicle would stimulate the economies of third-world countries in Africa, much in the same way that the Model T revolutionized American transportation and contributed to the economy via Ford’s Five Dollar Day. Thompson’s vision gave way to an all-terrain vehicle he dubbed the Warrior.

1974 Warrior Concept Car / THF92192

The Warrior was made in part from a plastic-composite material known as Royalex. In fact, the Warrior was only one part of Thompson’s larger “Project Vanguard,” where he envisioned a facility to fabricate Royalex, a building to assemble Warrior cars, a facility to build marine transportation, and eventually a place to build plastic habitat modules for housing. Ford Motor Company was initially supportive, but ultimately passed on the project in 1967.

Despite this setback, Thompson believed his vehicle had potential. Hoping to garner interest for investment in the program, he gathered some friends and produced a prototype to demonstrate the possibilities of his unique application of Royalex. Unfortunately, while every potential investor he approached told him it was a good idea, Thompson was unable to secure the funding, eventually shutting down the project in 1979.

McKinley Thompson and Crew Testing the Warrior Concept Car, 1969 / THF113754

The Warrior project was ahead of its time in design and philosophy—the extensive use of plastic was revolutionary at the time. Thompson regretted not being able to get the project going, but he felt pride knowing that his prototype proved its feasibility. To learn more about his incredible story, check out the blog post "McKinley Thompson, Jr.,: Designer, Maker, Aspiring Entrepreneur," or watch this Innovation Journeys Live! program where I discuss Thompson’s story through the lens of the Model i habit “Stay Curious."

Our third and final Entrepreneur in Residence for the Initiative for Entrepreneurship was Jessica Robinson, co-founder of the Detroit Mobility Lab, Michigan Mobility Institute, and Assembly Ventures, a venture capital firm. With dramatic new transportation technologies on the horizon, Robinson encourages technological education and understanding for the benefit of our increasingly mobile society. Throughout her time with The Henry Ford, Robinson had the opportunity to delve into the history of electric vehicles and share her expertise through several programs, including this Innovation Journeys Live! program. As quarantine restrictions relaxed a bit, Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson and I had the opportunity to interview Jessica. The entire interview is coming soon to our website, so stay tuned!

Jessica Robinson during an Interview for the Initiative for Entrepreneurship, 2020 (Photograph courtesy Brian James Egen)

During the final months of the Initiative for Entrepreneurship, I had the opportunity to delve into the fascinating world of patent medicine. A popular option for treatment throughout the 1800s, patent medicines were readily available and relatively inexpensive. They were often advertised as "cure-alls," with packaging and advertisements listing all of the illnesses and complaints that the product was believed to "cure." This trade card for Brown's Iron Bitters claims that it cures such ailments as indigestion, fatigue, and even malaria, among other things.

Trade Card for Brown’s Iron Bitters, Brown Chemical Co., 1890-1900 / THF277429

The popularity of patent medicines encouraged entrepreneurs to manufacture their own remedies and enter the industry. Some of the entrepreneurs were practitioners-turned-businessmen. Others were savvy businessmen with a flair for marketing. Dr. John Samuel Carter, maker of Carter's Little Liver Pills, was actually a pharmacist before establishing his patent medicine business. Unfortunately, other entrepreneurs were con artists, concocting their own remedies that either did absolutely nothing or were harmful to those who consumed them. As time would tell, many popular patent medicines were found to contain harmful ingredients such as morphine, cocaine, or dangerous levels of alcohol. This trade card advertises Burdock Blood Bitters, which was found to contain 25.2% alcohol by volume.

Trade Card for Burdock Blood Bitters, Foster, Milburn & Co., circa 1885 / THF215182

While there were hundreds of patent medicines created during this time, the most popular were the ones that were heavily advertised. Trade cards of the era inform us of the major players in the industry and allow us to examine the advertising tactics used by manufacturers to entice potential customers. To learn more about patent medicines and the entrepreneurs behind some of the most popular companies, check out the post “Patent Medicine Entrepreneurs: Friend or ‘Faux’?”

The Initiative for Entrepreneurship, funded by the William Davidson Foundation, has given The Henry Ford an amazing opportunity to analyze our collections through an entrepreneurial lens and highlight the stories of entrepreneurs from the past so that they might inspire the entrepreneurs of today and tomorrow. To learn more about what The Henry Ford is doing to support and encourage entrepreneurship, please visit the initiative’s landing page.

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford. Special thanks to all of the curators who have worked with me to share these stories over the last two years, and to the Initiative for Entrepreneurship digitization staff for making the collections accessible to the public.

21st century, 2020s, 2010s, entrepreneurship, by Samantha Johnson