Posts Tagged women's history

The Changing Nature of Sewing

This 1881 Singer sewing machine is on exhibit in Made in America in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Isaac Singer developed the first practical sewing machine for home use in the 1850s. / THF173635

Innovation has intended, and often unintended, effects. Take the sewing machine, for example. Its invention in the mid-1840s would make clothing more available and affordable. Yet, ironically, the sewing machine also resulted in a decline of sewing skills—not immediately, but over time. Nowadays, few of us know how to make clothing.

Once, things were very different. For centuries, sewing a family’s clothing by hand was a time-consuming and constant task for women. A woman often made hundreds of garments in her lifetime; all young girls were taught to sew.

A trade card for Clark's O.N.T. Spool Cotton from the late nineteenth century depicts a young girl using her sewing skills to repair a rip in her brother’s jacket so that “It will be as good as new and Ma won’t know!” / THF298697

When the sewing machine came on the scene during the mid-1800s, this handy invention made a big difference. For example, it now took about an hour to sew a man’s shirt by machine—rather than 14 hours by hand. In the 1850s, clothing manufacturers quickly acquired sewing machines for their factories, and, as they became less expensive, people bought them for home use.

While machines made it easier to make clothing at home, buying clothing ready-made was even less work. By the early 1900s, the ready-to-wear industry offered a broad range of attractive clothing for men, women, and children. Increasingly, people bought their clothing in stores rather than making it themselves.

Patricia Jean Davis wears a prom dress she made herself in 1960. / THF123841

Sewing skills may have declined, but what have we gained? A lot. Mass-produced clothing has raised our standard of living: stylish, affordable clothing can be had off the rack. For many, sewing remains a creative outlet, rather than a required task. For them, making clothing is no longer something you have to do, but something you want to do.

This post was adapted from a stop on our forthcoming “Hidden Stories of Manufacturing” tour of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in the THF Connect app, written by Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. To learn more about or download the THF Connect app, click here.

Additional Readings:

- Collecting Mobility: Insights from Ford Motor Company

- The Hitchcock Chair: An American Innovation

- The Wool Carding Machine

- Making the Cut: The Tripp Sawmill

Henry Ford Museum, women's history, THF Connect app, manufacturing, making, home life, fashion, by Jeanine Head Miller

Rookwood and Women Makers

Vase, 1917 / THF176918

This Rookwood Pottery vase from our collection, on view in the Art Pottery of the 20th Century exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, can tell us an unexpected story about women’s work and craft in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

During the late 19th century, ladies of high social standing in America were encouraged to broaden their interests beyond their homes. One of the most acceptable ways to do this was by taking up decorative china painting. Over time, these privileged women created associations with classes in china painting for women of all economic backgrounds. Probably the most important of these women was socialite Maria Longworth Nichols of Cincinnati, Ohio, who went beyond the accepted norm and established her own pottery that she called Rookwood.

Rookwood Pottery, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1900-1906 / THF297612

Beginning in 1880, Nichols hired talented young women—who would not have opportunities elsewhere—as well as men to create innovative ceramic wares in this novel commercial venture. At Rookwood, pioneering glazes and imagery made the Cincinnati-based company famous from coast to coast. One of the most significant innovations at Rookwood was its introduction of the “vellum” glaze in 1904. This signature glaze, seen on the vase at the top of this post, features a light-colored background where pictorial landscapes and flowers could appear almost like a painting.

Even before the development of the “vellum” glaze, competitors noticed Rookwood’s innovations and lured away some of their best potters and decorators. Also, over time, artists left Rookwood and started their own companies. They adopted Rookwood’s distinctive techniques, spreading the look of what was called “Art Pottery” around the United States. So, by the early decades of the 20th century, the pastime of ladies’ china painting evolved into a multi-million-dollar industry. Although Art Pottery flourished in the early 20th century, the arrival of the Great Depression and World War II all but extinguished Americans’ interest in decorative ceramics for the home.

This post was adapted from a stop on our forthcoming “Hidden Stories of Manufacturing” tour of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in the THF Connect app, written by Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. To learn more about or download the THF Connect app, click here.

Ohio, 20th century, 19th century, women's history, THF Connect app, making, Henry Ford Museum, furnishings, decorative arts, by Charles Sable, art

Mary Judge’s Big Break: Central Market Through the Eyes of One Head-Turning Market Character

"History of Detroit and Michigan," Silas Farmer, 1884, page 794 / THF139107

Fresh food markets have always brought communities of all backgrounds together for nutritional and social sustenance. The markets of the 19th century were different than today’s in terms of sanitation, regulations, and petty crimes, but the desire for community that existed then remains true. Today, Detroit’s Eastern Market and dozens of other markets in southeast Michigan provide citizens with food security and support a burgeoning urban agricultural movement and the local economy.

Interior of a farmers’ market, 1875, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Originally published in Earl Shinn, A Century After: Picturesque Glimpses of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania (published in Philadelphia by Lane Allen & Scott and J.W. Lauderbach, 1875), pg. 156, on the title page of the chapter "Marketry.” This illustrates what we can imagine the inside of Central Market looked like on a busy market day. / THF610498

The Vegetable Building (now being reconstructed in Greenfield Village) opened in Detroit's public market, then known as City Hall Market, in 1861. It remained a hub of community cohesion and commercial competition for 30 years until the city closed it, later dismantling it and relocating it to Belle Isle in 1894. In the three decades that the Vegetable Building attracted vendors and customers, Detroit’s population grew from 45,619 to 205,876 (per Detroit Historical Society) and the market tried to keep pace.

Mounting calls for the demolition of Detroit’s rat-infested “eyesore” resulted in the obliteration of the three-story “Central Market” brick building that housed butchers and market administrators between 1880 and 1894. It also prompted removal of the Vegetable Building to Belle Isle, and its replacement with a retail park (Cadillac Square) and a new public market (Eastern Market). This process destroyed the public market in central Detroit, but ultimately preserved the market’s Vegetable Building.

The Henry Ford acquired the Vegetable Building in 2003. After its reconstruction, the Central Market’s Vegetable Building will allow us to tell the stories of the vendors and consumers that frequented the market. These stories will illustrate that Central Market was a place where Detroiters came to purchase food stuffs, where entrepreneurs (many of them immigrants) were able to make a living, and where vibrant community life (including competition and discrimination) played out.

This year, we’ve been working to establish authentic stories as the basis for living history programming at the Vegetable Building, featuring costumed presenters and dramatic performances. Additional research underscores decisions about modern-day vendors invited to sell their honey, bread, pickles, eggs, flowers, and fresh fruits and vegetables to visitors at weekly markets and specialty markets in Greenfield Village.

Group of women, one with a baby carriage, in front of the Central Market Building, Detroit, Michigan, circa 1890. / THF623829

A partnership between The Henry Ford and the University of Michigan Museum Studies Program resulted in a script for a dramatic presentation that will help guests grasp the numerous ways that the market building affected urban life. Four students from the Museum Studies Program—Kathleen Brown (American Culture), Laurel Fricker (Classical Art and Archeology), Antonello Mastronardi (Classics), and myself, Ayana Curran-Howes (Environment & Sustainability)—crafted a script for a noteworthy Central Market character. The market was filled with characters, but one that captured the attention of newspaper reporters, the police, and a fair number of male suitors was Mary Judge. She became the focus of our investigation.

Our research into Mary Judge unveiled a fascinating and difficult, yet vibrant, individual. Newspaper reports documented her wit, sharp tongue, charm, and self-awareness as a woman staking her claim to independence. Newspaper reports from the Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press gave us a foundation on which to build a script for an entertaining and educational performance.

Vegetable Shed at Detroit’s City Hall Market, known as Central Market after 1880. It is identified as “Cadillac Square Market (Detroit, Mich.)” in the George Washington Merrill photographs collection, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library (BL003974). The original was one of two photographic images likely taken by James A. Jenney for A. J. Brow, Detroit, Michigan, and published as a stereograph. The original stereograph is in the Burton Collection, Detroit Public Library. We believe the woman circled in orange may be Mary Judge, vending flowers.

The script, featuring Mary Judge, is set during a Saturday night market in the 1880s. We chose a Saturday night market to introduce guests to the hustle and bustle of market life that everyday Detroit residents experienced. Farmers saved their best produce for busy Saturday nights when throngs of factory workers and working-class citizens came to purchase fresh produce and meat, as well as to socialize.

Mary Judge enters as a whirlwind. Her livelihood depended on capturing the public’s attention, and the dramatic presentation conveys that urgency. Mary also conveys the tumultuous yet essential relationship that hucksters like herself had with the farmers who grew the products that hucksters resold. Mary’s success at reselling depended on the relationships she cultivated with other vendors and the larger market community. The eight-minute solo act features Mary’s opinions about the role of the market in Detroit life, before the politics around the closing of the market disrupted Mary’s status quo starting in 1891.

What did Mary resell? The Michigan climate lent itself to a wide array of produce. Consumers could choose between market crops such as strawberries and cherries, often eaten to the point of bellyache (Detroit Free Press, June 25, 1874), or other seasonal crops such as rhubarb, cucumbers, and celery worthy of larceny (Detroit Free Press, August 12, 1879). Mary herself sold many different things, including coffee, flowers, fruit, poultry, and “fried cakes, gingerbread, pig's feet” (November 22, 1875). The Free Press reported her doughnuts “were very fillin’ for the price” (February 28, 1876).

Cherries. Nurseryman's Specimen Book, 1871-1888, page 48. / THF620211

Additional carnival-like attractions included strong-man machines, magic tricks, and exotic pets for sale. The variety of attractions created a bustling crowd that made it “often a feat to swallow a cup of coffee, without having it spilled” (Detroit Free Press, December 19, 1869).

The research plan we devised included numerous stages.

We reviewed other dramatic performances at The Henry Ford, including “The Disagreeable Customer” at J.R. Jones General Store and “How I Got Over” at Susquehanna Plantation. We also reviewed expert advice about living history programming collected in the Living History Anthology (Katz-Hyman et al., 2018). These informed the structure and style of our script.

Then, we asked ourselves “What was the social and economic function of the market? Who was allowed to keep a stall in the market and in what ways were they restricted, supported, and able to survive in this market economy?” Answers to these questions were revealed through secondary sources including Gloria Main, “Women on the Edge: Life at Street Level in the Early Republic” (2012); Jen Manion, “Dangerous Publics,” in Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America (2015); and Melanie Archer, “Self-Employment and Occupational Structure in an Industrializing City: Detroit, 1880” (1991).

We also looked at Detroit’s demographic data to understand the composition of the consumers in the market space. Then we conducted primary research, reviewing news reports published in the Detroit Free Press and the Detroit News that featured Mary Judge over 30 years. These conveyed the verbiage of the time, the historic perspective on events, the politics of the past, and the atmosphere of the market. The newspaper coverage of the market generated a body of evidence that continues to inform us.

From left to right: Ayana Curran-Howes, The Henry Ford’s Curator of Agriculture and the Environment Debra Reid, and Antonello Mastronardi, looking at the site where the Vegetable Building is being reconstructed in Greenfield Village, March 6, 2021. Photo taken by Laurel Fricker.

The low capital investment required to become a huckster allowed some immigrants to Detroit, including Mary Judge, to carve out a space in the public market. Other immigrants, including English and Irish individuals as well as Germans, Poles, and Italians, gained a toehold on economic independence. German butchers dominated the fresh- and processed-meat markets. They had more capital and political influence and, therefore, access to better stalls. In contrast, the Italians, newcomers during the 1880s, tried their hand at selling fruit.

Long before these European ethnic groups arrived, Black Detroiters faced racism in the marketplace and endured discrimination and violence. Nonetheless, they used the marketplace, as did other entrepreneurs, to sell their labor as chimney sweeps and whitewashers (those who painted cellars and building interiors, even the Vegetable Building interior, to intensify natural light).

The portrayal of Mary Judge will show guests how women used huckstering to gain financial independence. This was one of few alternatives for single women at the time, other than domestic service. Secondary readings and primary evidence indicated that women rarely held public-facing positions comparable to that of Mary Judge, the Central Market huckster. When they did, they were harassed by men and police alike. The consequences compounded for poor unmarried women, identified as “unladylike” in demeanor, and disruptive in action.

Hierarchies based on privilege kept many vendors marginalized. Female and immigrant vendors had to overcome language barriers, and had to navigate racism, sexism, and xenophobia when they tried to obtain permits, rent a stall, and obtain goods to sell. As an example, anti-immigrant sentiment followed Italian fruit vendors wherever they went. Mary Judge perpetrated this herself, verbally engaging with Italians and decrying their business decisions: “Go an’ absolve yerself of your business, sir; an’ not be hawkin’ ye’r truck on the streets this blessid day [Sunday]” (Detroit Free Press, July 25, 1887).

From left to right: Debra Reid, Kathleen Brown, Ayana Curran-Howes, Laurel Fricker, Antonello Mastronardi, and The Henry Ford’s Director of Greenfield Village Jim Johnson, standing outside the fenced off area where the Vegetable Building was being erected, March 6, 2021. Photo taken by Jeanine Head Miller.

All vendors faced other societal pressures. One of the most pernicious threats, petty theft perpetrated by those “sampling” products, undermined market vendors. Mary turned to market administrators to mediate her grievances, as did other vendors. She also reported abuses to the police, who intervened in some situations.

Despite these barriers, hucksters made this their way of life and stayed in the market for decades. Mary Judge, a twice-married devout Catholic, was as durable a huckster as one could be. She kept a stall from 1863 until city officials dismantled the market in 1894.

Starting in Spring 2022, you will be able to visit the Vegetable Building in Greenfield Village, and soon you'll be able to meet the “queen of the market,” Mary Judge, selling coffee and decades of wisdom as a huckster from her stall. This coming-soon one-woman show (as Mary would have preferred it) will illustrate huckstering as an occupation and as a way of life.

Thanks to the following people for research support and guidance during the Winter 2021 term:

- Gil Gallagher, curatorial research assistant volunteer, The Henry Ford

- Jim Johnson, Director of Greenfield Village and Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes, The Henry Ford

- Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life, The Henry Ford

- Patricia Montmurri, author/journalist, Detroit Free Press

- Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment, The Henry Ford

- Susan Whitall, author/journalist, Detroit News

Ayana Curran-Howes is 2021 Simmons Intern at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Detroit Central Market Vegetable Building: Curator Q&A

- The Market, Envisioned

- Reading an Artifact: The Reconstructed Detroit Central Market Vegetable Shed

- This GivingTuesday Help The Henry Ford Bring a Historic Piece of Detroit to Greenfield Village

food, shopping, women's history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Detroit, Detroit Central Market, research, by Ayana Curran Howes

Amazing Moments: An Interview with Puppeteer Carmen Osbahr-Vertiz of Sesame Street

Carmen Osbahr-Vertiz and Rosita. / Photo courtesy of Sesame Workshop

Carmen Osbahr-Vertiz shares her journey to becoming a professional puppeteer, how she met Jim Henson, and what it’s like being a part of the Sesame Street family.

As a curator at The Henry Ford, I gained renewed appreciation for Jim Henson while researching the 50th anniversary of Sesame Street in 2019, then again while commemorating Henson’s legacy on the 30th anniversary of his passing in 2020. So it was with great anticipation that I looked forward to interviewing Carmen Osbahr-Vertiz, puppeteer for the Sesame Street character Rosita and someone who had worked for and personally known Jim Henson.

Carmen enchanted us with her stories: growing up in Mexico; her personal interests and love of family; her passion for puppetry and how this turned into her involvement with Jim Henson Productions; how she helped create her Sesame Street character, who was vibrant, outspoken, and passionate—much like Carmen herself.

Carmen struck us as fearless—a young, raw talent beating out more seasoned professionals for work, leaving Mexico behind to attend a puppetry workshop in New York City because she desperately wanted to learn more, and staying there because Jim Henson himself asked her to. She regrets that she never returned home, but recognizes that, through her work, she can proudly represent and keep close to her heart her love of her homeland, community, and family.

—Donna R. Braden

Did you know from an early age that you wanted to work with puppets, become a professional puppeteer?

No. Of all my friends growing up in Mexico City, I was the one who had no idea what she wanted to do. Nothing that gave me a sign. At one time, I thought I wanted to go to the Olympics—I was good in sports, very competitive. I even wanted to work with and talk to the dolphins until I found out about all the science I would need.

When I was 5 or 6 years old, I did love to watch Topo Gigio [a character on a children’s puppet show on Italian television in the early 1960s] every Monday on TV. He was so alive. And then when I was 8, I remember having a playdate at a friend’s house watching Plaza Sésamo [Mexico’s Sesame Street, one of the first international co-productions of the show, which started running in 1972] for the first time. We laughed and sang.

I think my curiosity was there—I wanted to know how they did it. I watched the Muppets, too, when that show came out. But I didn’t know much about Jim Henson until a friend of my brother brought me a book, Of Muppets and Men [Of Muppets and Men: The Making of the Muppet Show, written by Christopher Finch], when I was in high school. The book had pictures of the puppeteers and explanations on how they did it. It was the first time I saw how it worked, and it blew my mind that they had to work with their arms above their heads, that they did the voices themselves.

Was reading that book your light bulb moment?

The light bulb really went on for me when my brother, who was working for Televisa [a Mexican mass media company] at the time, invited me and my friends to attend a workshop with Americans for a children’s show that had puppets. I was the only one called back. I was with a bunch of professional actors from university—the youngest in the group at 18 with no idea of acting. On the third day of the workshop, they brought the puppets out, and we had to work with the cameras and monitors and learn how, when you move the puppet one way, it appears the other way on the monitor—it’s inverted. That is when it really clicked for me. I started remembering all I had watched on TV, how the puppets breathe and walk. They live. I was mesmerized by the challenge to make this thing with no expression have expression.

While working on the children’s television show Super Ondas for Mexican mass media company Televisa in the 1980s, Carmen Osbahr-Vertiz (at right) was one of a small group of professional female puppeteers in the industry. / Photo courtesy of Carmen Osbahr-Vertiz

I loved it. I was in heaven. While the professional actors were having problems because their expressions were happening below, not above, I was making this puppet come alive. It didn’t matter that I was shy or didn’t have the acting skills.

I think my brother knew when he invited me to that workshop. After that, it all came together for me—why I loved the puppets, the magic, the joy, the curiosity.

And I got a job working for Televisa.

How did you cross paths with Jim Henson?

I was working as a puppeteer at Televisa on The Treasure of Knowledge show when I met Kermit Love from the Henson group. He was in Mexico to train puppeteers from Plaza Sésamo. I asked him if he could help me. I felt that I was the only person in Mexico that was passionate about the puppets, that I had respect for them that no one else did. Most puppeteers were actors who were quick to move on to other things. I started asking questions about why we couldn’t do our own voices. I wanted to get better at my craft. I wanted our work to be better.

Kermit invited me to the U.S. to attend a workshop. So I went to Manhattan. One day, he came by and said, “We’re going to a party. Here’s your mask.” Suddenly, I was at a masquerade party thrown by Jim Henson at the Waldorf Astoria. That’s when I met Jim for the first time. It was so amazing. He was so amazing. He invited me to come observe production of his next season of Sesame Street. Just to see them working as a team. They were brilliant, geniuses, magicians. I thought to myself I would love to stay here. This is a dream.

| Carmen’s Calls to Action |

“Never be afraid of your dreams. And if things don’t work out quite the way you hoped now, you will find a way to make them work in the future.” |

When Jim did call me and said he decided he wanted me to be a part of the Muppet family, that he wanted a strong female puppeteer, I raised my hands and was like, “WAAAWWW!”

That was 1989, just a year before Jim died.

What role did you play in bringing your Sesame Street character Rosita to life?

When Jim was alive, he told me he always wanted a bilingual character for Sesame Street. I told him I didn’t really speak a lot of English. I was probably at 25%. He said no worries. We will work together. It will come out naturally. It’ll be fun.

Designer Ed Christie first asked me to help write a bio for my character because he wanted to create someone I would be comfortable with. So I told him I wanted her to be colorful and present. We Latinos like to hug and kiss. She needs to be cuddly with flowing hair. I wanted her to play the guitar and be musical like I was.

I wanted to name her Rosita, after my best friend in Mexico City, Rosa. I really liked the idea of how people could R the R’s—RRRRRosita.

| Meet Rosita, a Bilingual Turquoise Monster |

| Full name: Rosita la Monstrua de las Cuevas (the Monster of the Caves) |

Ed heard all that and made a puppet that wasn’t tiny but had a presence. She has a round belly, live hands and wings like a flying squirrel. He said he designed her like that thinking of a flamenco skirt. And she’s turquoise, which is an important color in Mexican culture, representing life and hope.

I just loved her from the start. Rosita is my immigrant girl, a happy, family-oriented monster that speaks better English than I do. She’s confident, doesn’t mind making mistakes and has explosive feelings.

Is it difficult to bring Rosita’s explosive personality to life?

When you’re a puppeteer, you quickly learn that it is not just about your character above. It’s also about the layer underneath.

We are in a very physical situation that is often very uncomfortable. You can’t be claustrophobic and you can’t be smelly. We all joke about eating no onions or garlic, brushing your teeth.

With Rosita, I have someone else doing her right hand as well, so he has to match what I am doing so carefully. If you move the puppet slightly the wrong way, for example, it won’t look like it is listening. It is very specific, and you’re sharing a small, cramped space with others, looking at monitors and trying to work in extremely coordinated ways.

Carmen bringing Rosita to life on the set of Sesame Street. / Photo courtesy of Richard Termine/Sesame Workshop

As puppeteers, we are solving physical problems all the time, learning new ways to trick the cameras into presenting our characters as living, breathing things. It’s about subtle movements, creating reactions that match with the other characters.

In your creative community, in the entertainment industry in general, do you feel as if Jim Henson’s legacy is still alive and well?

Jim was amazing. His mind was brilliant. He was curious and put together this world around all the things he liked. He was ahead of his time, and we keep trying to keep his legacy alive because he had it right.

For me, I can see that he still touches people. I have so many young people come up and say, “I want to be a puppeteer. Jim Henson changed my life.” And so many of them are very, very clever. They are bringing all of these new ideas and technologies to the conversation. I’m so proud of everyone that comes to us that were inspired by Jim. It’s so rewarding.

What about with audiences? Does Jim’s vision resonate with the next generation?

I know animation is where it’s at today, but it’s just so flat, and Jim’s characters are just so alive. When we did Sesame Street’s 50th anniversary concert live a few years ago, I was so worried about the audience’s reaction to seeing us rolling around, sweating on the stage. What I felt instead was absolutely incredible. I saw grandparents with their grandkids, parents with their children singing and crying, connecting with each other. Because of Jim. It was so touching, so inspiring.

In terms of your impact, how has your career influenced others? Can you speak to the appreciation you have for how your role as Rosita is helping children learn and grow?

What this job has brought to me has been amazing, and impact really goes both ways. The impact Rosita has had on others and the impact people have had on my life because of her.

Rosita. / Photo courtesy of Sesame Workshop

Rosita is part of lots of outreach within communities where so many see her and the other characters as friends. Today, we are working on racial justice messages, and Rosita and I have also been working with military families for 10 years. We’ve created videos for young parents so they can help explain deployment to their children. We’ve also had a script where Rosita’s dad comes back home from a tour of duty and is injured and in a wheelchair. The words in that video—how military families have to deal with both invisible and physical injuries, the suffering they face and sacrifices they make—I took it very personally. I even asked myself if I thought I was ready to become an American citizen. It was something I had researched before, but I was never sure if I was ready—I’m so proud of my Mexican heritage. After working with military families, though, I said to myself that I was definitely ready, and I became an American citizen.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. Jennifer LaForce is Editorial Director at Octane and Editor of The Henry Ford Magazine. This article was first published in the June–December 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

New York, 21st century, 20th century, women's history, TV, The Henry Ford Magazine, popular culture, Jim Henson, immigrants, Hispanic and Latino history, by Jennifer LaForce, by Donna R. Braden

Interior of Henry Ford’s Private Railroad Car, “Fair Lane,” June 22, 1921 / THF148015

Beginning in 1921, Henry and Clara Ford used their own railroad car, the Fair Lane, to travel in privacy. Clara Ford designed the interior in consultation with Sidney Houghton, an interior designer based in London. The interior guaranteed a comfortable trip for the Fords, their family, and others who accompanied them on more than 400 trips between 1921 and 1942.

The view out the railcar windows often featured the landscape between Dearborn, Michigan, and Richmond Hill, Georgia, located near Savannah. The Fords purchased more than 85,000 acres in the area, starting in 1925, remaking it into their southern retreat.

On at least three occasions, Henry Ford might have looked out that Fair Lane window, observing changes in the landscape between Richmond Hill and a siding (or short track near the main railroad tracks, where engines and cars can be parked when not in use) near Tuskegee, Alabama. Henry Ford took the railcar to the Tuskegee Institute in 1938, 1941, and 1942, and Clara accompanied Henry at least twice.

Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Tuskegee, Alabama, March 1938 / THF213839

Henry first met with George Washington Carver and Austin W. Curtis at Tuskegee on March 11, 1938. A small entourage accompanied him, including Ford’s personal secretary, Frank Campsall, and Wilbur M. Donaldson, a recent graduate of Ford’s school in Greenfield Village and student of engineering at Ford Motor Company.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford on the Tuskegee Institute Campus, 1938. / THF213773

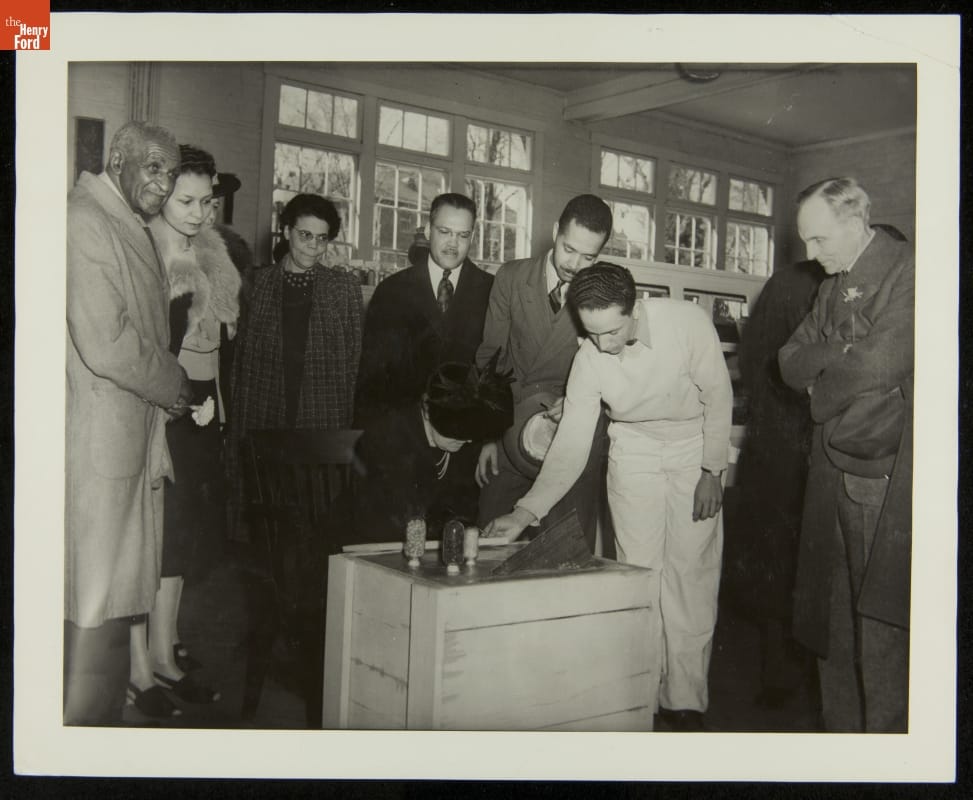

Photographs show these men viewing exhibits in the Carver Museum, installed at the time on the third floor of the library building on the Tuskegee campus (though it would soon move).

Austin Curtis, George Washington Carver, Henry Ford, Wilbur Donaldson, and Frank Campsall Inspect Peanut Oil, Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF 213794

Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, Henry Ford, and George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF214101

Clara accompanied Henry on her first trip to Tuskegee Institute, in the comfort of the Fair Lane, in March 1941. Tuskegee president F.D. Patterson met them at the railway siding in Chehaw, Alabama, and drove them to Tuskegee. While Henry visited with Carver, Clara received a tour of the girls’ industrial building and the home economics department.

During this visit, the Fords helped dedicate the George W. Carver Museum, which had moved to a new space on campus. The relocated museum and the Carver laboratory both occupied the rehabilitated Laundry Building, next to Dorothy Hall, where Carver lived. A bust of Carver—sculpted by Steffen Thomas, installed on a pink marble slab, and dedicated in June 1937—stood outside this building.

The dedication included a ceremony that featured Clara and Henry Ford inscribing their names into a block of concrete seeded with plastic car parts. The Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s most influential Black newspapers, reported on the visit in its March 22, 1941, issue. That story itemized the car parts, all made from soybeans and soy fiber, that were incorporated—including a glove compartment door, distributor cap, gearshift knob, and horn button. These items symbolized an interest shared between Carver and Ford: seeking new uses for agricultural commodities.

Clara Ford, face obscured by her hat, inscribes her name in a block of concrete during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, March 1941, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama. Others in the photograph, left to right: George Washington Carver; Carrie J. Gleed, director of the Home Economics Department; Catherine Elizabeth Moton Patterson, daughter of Robert R. Moton (the second Tuskegee president) and wife of Frederick Douglass Patterson (the third Tuskegee president); Dr. Frederick Douglass Patterson; Austin W. Curtis, Jr.; an unidentified Tuskegee student who assisted with the ceremony; and Henry Ford. / THF213788

Henry Ford inscribing his name in a block of cement during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, Tuskegee Institute, March 1941 / THF213790

After the dedication, the Fords ate lunch in the dining room at Dorothy Hall, the building where Carver had his apartment, and toured the veterans’ hospital. They then returned to the Fair Lane railcar and headed for the main rail line in Atlanta for the rest of their journey north.

President Patterson directed a thank you letter to Henry Ford, dated March 14, 1941. In this letter, he commended Clara Ford for her “graciousness” and “her genuine interest in arts and crafts for women, particularly the weaving, [which] was a source of great encouragement to the members of that department.”

The last visit the Fords made to Tuskegee occurred in March 1942. The Fair Lane switched off at Chehaw, where Austin W. Curtis, Jr., met the Fords and drove them to Tuskegee via the grounds of the U.S. Veterans’ Hospital. Catherine Patterson and Clara Ford toured the Home Economics building and the work rooms where faculty taught women’s industries. Clara rode in the elevator that Henry had funded and had installed in Dorothy Hall in 1941, at a cost of $1,542.73, to ease Carver’s climb up the stairs to his apartment.

The Fords dined on a special luncheon menu featuring sandwiches with wild vegetable filling, prepared from one of Carver’s recipes. They topped the meal off with a layer cake made from powdered sweet potato, pecans, and peanuts that Carver prepared.

Tuskegee shared the Fords’ itinerary with Black newspapers, and the April 20, 1942, issue of Atlanta Daily World carried the news, “Carver Serves Ford New Food Products.” They concluded, in the tradition of social columns at the time, by describing what Henry and Clara Ford wore during the visit. “Mrs. Ford wore a black dress, black hat and gloves and a red cape with self-embroidery. Mr. Ford wore as usual an inconspicuously tailored business suit.”

Dr. Patterson wrote to Henry Ford on March 23, 1942, extending his regrets for not being at Tuskegee to greet the Fords. Patterson also reiterated thanks for “Mrs. Ford’s interest in Tuskegee Institute”—“The people in the School of Home Economics are always delighted and greatly encouraged with the interest she takes in the weaving and self-help project in the department.”

The Fords sold the Fair Lane in 1942. After many more miles on the rails with new owners over the next few decades, the Fair Lane came home to The Henry Ford. Extensive restoration returned its appearance to that envisioned by Clara Ford and implemented to ensure comfort for Henry and Clara and their traveling companions. Now the view from those windows features other artifacts on the floor of the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, in place of the varied landscapes, including those around the Tuskegee Institute, traveled by the Fords.

A view of the interior of Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car, the “Fair Lane,” constructed by the Pullman Company in 1921, restored by The Henry Ford to that era of elegance, and displayed in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF186264

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

1940s, 1930s, 20th century, Alabama, women's history, travel, railroads, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, George Washington Carver, Ford family, Fair Lane railcar, education, Clara Ford, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

The Office of George Nelson & Co.

In 1947, George Nelson opened his eponymous design office on Lexington Avenue in New York City. George Nelson & Co., as the first iteration of the office was named, was located on the second floor of a narrow building; the ground floor was a health food restaurant. In the introduction to Nelson’s collection of 26 essays called Problems of Design, Museum of Modern Art curator Arthur Drexler recalled that the restaurant had a loyal customer base, even though it “smelled funny.” Drexler observed an “unnerving contrast between the solemnity on the ground floor and that haphazard urbanity on the floor above.” George Nelson’s tendency to do many things simultaneously would have created a sometimes chaotic but always exhilarating environment that perhaps occasionally featured a pungent reminder of its downstairs neighbor.

Over the next four decades, the office would change names, move around New York City, employ many of the best and brightest designers, and complete a dizzying number of projects for a variety of clients. Constant through these changes was George Nelson’s emphasis on the importance of the design process. Even late nights at the office, sometimes saturated with drink, could be productive. Concepts imagined the night before might find their way to the drawing board in the bright light of the morning to be refined, altered, and honed further.

Sometimes, Nelson was more involved with the ideation and later refinement of an idea than with its realization—the office’s staff designers tended to that. A one-time employee of the office, architect and designer Michael Graves, reminisced that Nelson “would come in and touch down his magic dust on somebody and then leave.” While Nelson’s “magic dust”—and the powerful brand that his name symbolized—was vital to the office’s success, Nelson’s own hand in the development of a product or design was sometimes exaggerated. It has taken many years for certain designs to be accurately attributed—and surely there are many more that have not been and may never be. This problem is not unique to Nelson’s office, however, and was often the price designers paid to gain experience and contacts in the field. Hilda Longinotti, the office’s long-time receptionist, reflected on this: “As the years went by, George with all of his intelligence, did not do one thing he should have done and that is make the most talented designers partners in the firm. He gave them titles, but he didn’t give them a piece of the business. As the years went by, they left to form their own offices…”

The hundred-plus people employed by George Nelson over the course of his career—some for a short time and others much longer—include Lance Wyman, Ernest Farmer, Tomoko Miho, Irving Harper, Michael Graves, Don Ervin, Lucia DeRespinis, George Tscherny, and many others. The Henry Ford’s collections feature graphics and products designed by Nelson himself as well as some confirmed to be designed by the office’s staff. Below, we will focus on three of these designers: Irving Harper, George Tscherny, and Tomoko Miho.

Irving Harper

For many of the years that George Nelson was Herman Miller’s design director, Irving Harper was the director of design at George Nelson’s office. George Nelson hired Harper in 1947, and Harper did a little bit of everything in his tenure there—industrial design, furniture, and, eventually, graphics. Although he didn’t have much experience in graphic design, Harper quickly excelled. Herman Miller’s sweeping red “M” logo was one of Harper’s first forays into graphic design, and, 75 years later, the logo is still beloved and used by the company. Harper also designed many of the Nelson Office’s notable products, including many of the clocks for Howard Miller and the iconic Marshmallow sofa.

Born in New York City in 1916, Harper trained as an architect at New York’s Cooper Union and Brooklyn College. He soon began designing interiors. At the age of 19, Harper was hired by Gilbert Rohde, Nelson’s predecessor at Herman Miller, to work on projects for the 1939 World’s Fair, including renderings and production drawings. Harper worked for George Nelson from 1947 until 1963, when he left to start his own firm, Harper+George, which primarily designed interiors for commercial clients. Harper began to create incredibly intricate paper sculptures in the early 1960s as a stress relief measure, turning him into a proper sculptor as well as designer. The paper sculptures bridged his active design years into his retirement in 1983, when his sculpting output greatly increased. Harper died in 2015 at his long-time home in Rye, New York.

This 1947 advertisement features Herman Miller’s sweeping new “M” logo, which was designed by Irving Harper in one of his first forays into graphic design. / THF623975

Irving Harper designed this 1961 Herman Miller advertisement for the “Eames Chair Collection.” / THF266918

George Tscherny

George Tscherny began working at George Nelson & Co. in 1953. Nelson hired Tscherny specifically to design print advertisements for the office’s largest client, Herman Miller, under the direction of Irving Harper. Nelson reportedly had a hands-off approach. Tscherny recalled, “He had no pressing need to involve himself in my area. That meant I could do almost anything within reason.” Tscherny was able to expand and hone his graphic style, which stresses the inherent nature of objects and is always human-centered—even when a human isn’t visible.

Tscherny, born into a Jewish family in 1924 in Budapest, Hungary, grew up in Berlin, Germany. The rise of the Nazi Party and, specifically, the evening of Kristallnacht (“The Night of the Broken Glass”) on November 10, 1938, led Tscherny to believe “there was no future for us in Germany.” The following month, George and his younger brother Alexander escaped to the Netherlands, where they spent the following years moving between refugee camps and Jewish orphanages. Their parents, Mandel and Bella (Heimann) Tscherny, obtained visas and emigrated to the United States in 1939. It wasn’t until June of 1941 that George and Alexander finally joined their parents in New Jersey, after numerous close calls with the Nazi Party. In 1943, George Tscherny enlisted as a soldier in the U.S. Army to fight in World War II and went back to Europe, using his language skills as an interpreter. After the war, Tscherny used the G.I. Bill to fund his study of graphic design, attending the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York; he would leave just weeks before graduation to work for designer Donald Deskey. In 1953, he was hired by George Nelson.

Although Tscherny only worked for Nelson until 1955, numerous advertisements he designed for Herman Miller during his short tenure became iconic of the era. Tscherny left the office to start his independent design studio, which designed graphics for major corporations. He also taught at the School of the Visual Arts in New York City for over half a century. Tscherny says he attempted to teach his students, as Nelson taught him, “not to have preconceptions, but rather to be receptive to new ideas.” Tscherny, currently 96 years old, lives in New York City with Sonia, his wife of over 70 years.

The famous "Traveling Men" advertisement for Herman Miller was designed by George Tscherny in 1954. / THF624755

George Tscherny’s 1955 “Herman Miller Comes to Dallas” advertisement implies a human presence through the inclusion of a cowboy hat. / THF148287

Tomoko Miho

Tomoko Miho was one of a few women that George Nelson hired to design for his office. Miho is not very well-known today, both due to a societal tendency to ignore contributions of women working in the mid-century period and to her private and reserved nature. Although her name may be unfamiliar, this is not due to a lack of talent—Miho’s skill in graphic design and art direction were extraordinary. Once you identify her clean, minimalist, architectural style, it becomes distinct from the others working in the Nelson office.

Born Tomoko Kawakami in 1931 in Los Angeles, she and her family were held at the Gila River Japanese internment camp in Arizona during World War II. Afterwards, the family moved to Minneapolis, where Tomoko began coursework in art and design. She received a full scholarship to the Art Center School in Los Angeles, where she graduated with a degree in Industrial Design in 1958. She worked as a packaging designer for Harley Earl Associates before moving to New York City and, on the recommendation of George Tscherny, she contacted Irving Harper and was then hired by George Nelson in 1960. As the prominent graphic designer (and later colleague of Miho) John Massey stated, Miho was “a master of the dramatic understatement.” Her work is graceful, clean, and highly structured, while also seeming unrestricted. Her designs are masterfully well-balanced and lend themselves well to their primary purpose—conveying information.

Miho worked for the Nelson office until 1965, when family commitments took her to California, back to New York City, and then to Chicago, where she worked for the Center for Advanced Research and Design (CARD). She designed possibly her best known work while working for CARD—the 1967 "Great Architecture in Chicago" poster. It reflects her sense that Chicago’s architecture is “both solid and ethereal,” as Miho explained. Miho continued to collaborate with designers she met at George Nelson & Co. for years. She also had an incredibly long-lasting relationship with Herman Miller: she began designing for the company during her tenure at George Nelson & Co., continued while she was employed by CARD, and even after starting her own firm, Tomoko Miho Co., Herman Miller remained a client. Miho passed away in 2012 in New York City.

Tomoko Miho featured the Herman Miller logo in this price list, camouflaging it in bold contrasting stripes. This is one document in a suite, all featuring the same design, but in different colorways. / THF64160

The “Library Group” trade literature was designed by Tomoko Miho, circa 1970. / THF147737

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

Europe, New York, 20th century, women's history, immigrants, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White, advertising

New Racing Acquisitions at The Henry Ford

Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors.

The Henry Ford’s newest exhibition, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors, opened to the public on March 27. It’s been a thrill to see visitors experiencing and enjoying the show after so many years of planning.

Along with all of that planning, we did some serious collecting as well. Visitors to Driven to Win will see more than 250 artifacts from all eras of American racing. Several of those pieces are newly acquired, specifically for the show.

Shoes worn by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five. Block co-founded DC Shoes in 1994. / THF179739

The most obvious new addition is the 2012 Ford Fiesta driven by Ken Block in Gymkhana Five: Ultimate Urban Playground; San Francisco. The car checked some important boxes for us. It represented one of America’s hottest current motorsport stars, of course, but it also gave us our first rally car. The Fiesta wasn’t just for show—Block drove it in multiple competitions, including the 2012 X Games in Los Angeles, where he took second place (one of five podium finishes Block took in the X Games series). At the same time, we collected several accessories worn by Block, including a helmet, a racing suit, gloves, sunglasses, and a pair of shoes. The footwear is by DC Shoes, the apparel company that Block co-founded with Damon Way in 1994.

Racing toys and games are prominently represented in Driven to Win. We have several vintage slot cars and die cast models, but I was excited to add a 1:64 scale model of Brittany Force’s 2019 Top Fuel car. Force is one of NHRA’s biggest current stars, and an inspiration to a new generation of fans.

Charmingly dated today, Pole Position’s graphics and gameplay were strikingly realistic in 1983. / THF176903

Many of those newer fans have lived their racing dreams through video games. We had a copy of Atari’s pioneering Indy 500 cartridge already, but I was determined to add newer, more influential titles to our holdings. While Indy 500 didn’t share much with its namesake race apart from the general premise of cars competing on an oval track, Atari’s Pole Position brought a new degree of realism to racing video games. Pole Position was a top arcade hit in 1982, and the home version, released the following year, retained the full-color landscapes that made the game so lifelike at the time. I was excited to acquire a copy that not only included the original box, but also a hype sticker reading “Arcade Hit of the Year!”

Another game that made the jump from arcade to living room was Daytona USA, released in 1995 for the short-lived Sega Saturn. Rather than open-wheel racing, Daytona USA based its gameplay on stock car competition. The arcade version was notable for permitting up to eight machines to be linked together, allowing multiple players to compete with one another.

More recently, the Forza series set a new standard for racing video games. The initial title, Forza Motorsport, featured more than 200 cars and encouraged people to customize their vehicles to improve performance or appearance. Online connectivity allowed Forza Motorsport players to compete with others not just in the same room, but around the world.

One of my favorite new acquisitions is a photograph showing a young racer, Basil “Jug” Menard, posing with his race car. There’s something charming in the way young Menard poses with his Ford, a big smile on his face and hands at his hips like a superhero. His car looks worse for the wear, with plenty of dents and an “85” rather hastily stenciled on the door, but this young driver is clearly proud of it. Menard represents the “weekend warrior” who works a regular job during the week, but takes on the world at the local dirt track each weekend.

When we talk about a racer’s tools, we don’t just mean cars and helmets. / THF167207

Drivers may get most of the glory, but they’re only the most visible part of the large team behind any race car. There are folks working for each win everywhere from pit lane to the business office. Engineers are a crucial part of that group, whether they work for the racing team itself, the car manufacturer, or a supplier. In the early 20th century, Leo Goossen was among the most successful racing engineers in the United States. Alongside designer Harry Miller, Goossen developed cars and engines that won the Indianapolis 500 a total of 14 times from 1922 to 1938. We had the great fortune to acquire a set of drafting tools used by Goossen in his work. The donor of those tools grew up with Goossen as his neighbor. As a boy, the donor often talked about cars and racing with Goossen. The engineer passed the tools on to the boy as a gift.

We could not mount a serious exhibit on motorsport without talking about safety. Into the 1970s, auto racing was a frightfully dangerous enterprise. Legendary driver Mario Andretti commented on the risk in the early years of his career during our 2017 interview with him. Andretti recalled that during the drivers’ meeting at the beginning of each season, he’d look around the room and wonder who wouldn’t survive to the end of the year.

Improved helmets went a long way in reducing deaths and injuries. Open-face, hard-shell helmets were common on race tracks by the late 1950s, but it wasn’t until 1968 that driver Dan Gurney introduced the motocross-style full-face helmet to auto racing. Some drivers initially chided Gurney for being overly cautious—but they soon came to appreciate the protection from flying debris. Mr. Gurney kindly donated to us one of the full-face helmets he used in occasional races after his formal retirement from competitive driving in 1970.

And speaking of Dan Gurney, he famously co-drove the Ford Mark IV to victory with A.J. Foyt at Le Mans in 1967. We have a treasure trove of photographs from that race, and of course we have the Mark IV itself, but we recently added something particularly special: the trophy Ford Motor Company received for the victory. To our knowledge, Driven to Win marks the first time this trophy has been on public view in decades. Personally, I think the prize’s long absence is a key part of the story. Ford went to Le Mans to beat Ferrari. After doing so for a second time in 1967, Ford shut down its Le Mans program, having met its goal and made its point. All the racing world had marveled at those back-to-back wins—Ford didn’t need to show off a trophy to prove what it had done!

Janet Guthrie wore this glove at the 1977 Indy 500—when she became the first woman to compete in the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. / THF166385

For most of its history, professional auto racing has been dominated by white men. Women and people of color have fought discrimination and intimidation in the sport for decades. It is important to include those stories in Driven to Win—and in The Henry Ford’s collections. We documented Janet Guthrie’s groundbreaking run at the 1977 Indianapolis 500, when she became the first woman to compete in America’s most celebrated race, with a glove she wore during the event. I quite like the fact that the glove had been framed with a plaque, a gesture that underlined the significance of Guthrie’s achievement. We’ve displayed the glove in the exhibit still inside that frame. More recently, Danica Patrick followed Guthrie’s footsteps at Indy. Patrick also competed for several years in NASCAR, and in 2013 she became the first woman to earn the pole position at the Daytona 500. She kindly donated a pair of gloves that she wore in 2012, her inaugural Cup Series season.

Wendell Scott, the first Black driver to compete full-time in NASCAR’s Cup Series, as photographed at Charlotte Motor Speedway in 1974. / THF147632

Wendell Scott broke NASCAR’s color barrier when he battled discrimination from officials and fans to become the first Black driver to win a Cup Series race. Scott earned the victory at Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Florida, in December 1963. We acquired a photo of Scott taken later in his career, at the 1972 World 600. Scott retired in 1973 after sustaining serious injuries in a crash at Talladega Superspeedway. In addition to acquiring the photo, we were fortunate to be able to borrow a 1966 Ford Galaxie driven by Scott during the 1967 and 1968 NASCAR seasons.

Wendell Scott’s impact on the sport is still felt. Current star Darrell “Bubba” Wallace is the first Black driver since Scott to race in the Cup Series full-time. Following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, Wallace joined other athletes from all sports in supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. He and his teammates at Richard Petty Motorsports created a special Black Lives Matter paint scheme for Wallace’s #43 Chevrolet Camaro, driven at Virginia’s Martinsville Speedway on June 10, 2020. We acquired a model of that car for the exhibit. The interlocked Black and white hands on the hood are a hopeful symbol at a difficult time.

Our collecting efforts did not end when Driven to Win opened. We continue to add important pieces to our holdings—most recently, items used by rising star Armani Williams in his stock car racing career. There will be more to come: more artifacts to collect, more stories to share, and more insights on the people and places that make American racing special.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 20th century, women's history, video games, toys and games, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, engineering, Driven to Win, by Matt Anderson, African American history, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Memorial Paintings for Memorial Day

Americans always treasured the memory of the dearly departed, but during the era just after American independence, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, elaborate and artistic memorials were the norm. Scholars debate the reasons. Many believe that with the death of America’s most revered founding father, George Washington, in 1799, a fashion developed for creating and displaying memorial pictures in the home. Other scholars argue that the death of Washington coincided with the height of the Neoclassical, or Federal style in America. During the period after the Revolution, Americans saw themselves as latter-day Greeks and Romans. After all, they argued, the United States was the first democracy since ancient times. So, they used depictions of leaders like George Washington, along with imagery derived from antiquity.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for George Washington, by Mehetabel Wingate, 1800-1810 / THF6971

This wonderful memorial painting of George Washington was drawn in pencil and ink and painted in watercolors by a woman in Haverhill, Massachusetts, named Mehetabel Wingate. Born in 1772, Mehetabel was likely trained in painting as part of her education at an academy for genteel young ladies, much like a “finishing school” for young ladies in the 20th century. She also would have been tutored in the needle arts. The concept was to teach proper young ladies the arts as part of an appreciation for the “finer things” in life. This would prepare them for a suitable marriage and help them take their place in refined society.

In the academies, young women were taught to copy from artistic models for their work. In this case, Mehetabel Wingate copied a print engraved by Enoch G. Grindley titled in Latin “Pater Patrae” (“Father of the Country”) and printed in 1800, just after Washington’s death in 1799. Undoubtedly, she saw the print and was skilled enough to copy it in color. The image of the soldier weeping in front of the massive monument to Washington is impressive. Also impressive are the angels or cherubs holding garlands, and women dressed up as classical goddesses, grieving. One of the goddesses holds a portrait of Washington. Of course, the inscriptions tout many of Washington’s accomplishments. Mehetabel Wingate was a talented artist and ambitious in undertaking a composition as complicated as this one.

Watercolor Painting, Memorial for Mehetabel Bradley Wingate, by her daughter Mehetabel Wingate, 1796 / THF237513

Fortunately, The Henry Ford owns two additional works made by Mehetabel Wingate (1772–1846). From these, we can learn a bit about her life and her family. This remarkably preserved watercolor painting memorializes her mother, also named Mehetabel, who died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1796. Young Mehetabel, who would have been 24 in 1796, is shown mourning in front of a grave marker, which is inscribed. Although it is simplified, she wears a fashionable dress in the most current style. Around her is an idealized landscape, which includes a willow tree, or “weeping” willow, on the left, which symbolized sadness. On the right is a pine tree, which symbolized everlasting life. In the background is a group of buildings, perhaps symbolizing the town, including the church, which represented faith and hope. These are standard images seen in many, if not most, American memorial pictures. Mehetabel Wingate undoubtedly learned these conventions in the young girls’ academy in her hometown of Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Women in Classical Dress, 1790-1810, by Mehetabel Wingate / THF152522

The painting, above, while not a memorial painting, shows us how young ladies in the academies learned how to paint. Mehetabel seems to be practicing poses and angles, as the young ladies dressed as classical goddesses reach out to each other. It likely pre-dates both works previously shown and may have been done as a classroom exercise. As such, it is a remarkable survival.

In memory of Freeman Bartlett Jr. who died in Calcutta November the 1st 1817, aged 19 years, by Eliza T. Reed, about 1818 / THF14816

This example, painted later than Mehetabel Wingate’s work, shows the same conventions: a grieving female in front of a tomb with an inscription about the dearly departed—in this case, a young man who died at the tender age of 19 in far-off Calcutta. We also see the idealized landscape with the “weeping” willow tree and the church in the background.

Memorial Painting for Elijah and Lucy White, unknown artist, circa 1826 / THF120259

The painting above, done a few years later, shows some of the variations possible in memorial pictures. Unlike the previous examples, painted on paper, this was painted on expensive, white silk. It commemorates two people, Elijah and Lucy White, presumably husband and wife, who both died in their sixties. We see the same imagery here as before, although the trees, other than the “weeping” willows, are so abstract as to be difficult to identify.

Memorial Painting for Sarah Burgat, J. Preble, 1826 / THF305542

The example above represents a regional approach to memorial paintings. German immigrants to Pennsylvania in the late 1700s and early 1800s brought an interesting, stylized approach to their memorial paintings that have come to be known as “Fraktur.” The urn that would be seen on top of the monument in the previous examples now takes center stage, and is surrounded by symmetrically arranged birds. What we are seeing here is a combination of New England imagery, such as the urn, with Pennsylvania German imagery, such as the stylized birds. We know that this work was made in a town called Paris, as the artist, J. Preble, signed it in front of her name. There are two possible locations for Paris—one in Stark County, Ohio, and the other in Kentucky. Both had sizeable German immigrant populations in the 1820s. As America was settled and people moved west in the early 19th century, cultural practices melded and merged.

By the 1840s and 1850s, the concept of the memorial painting came to be viewed as old-fashioned. The invention of photography revolutionized the way folks could save representations of loved ones and friends. By the middle of the 19th century, these paintings were viewed as relics from the past. But in the early 20th century, collectors like Henry Ford recognized the historic and artistic value of these works and began to collect them. As a uniquely American art, they provide insight into the values of Americans in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, 19th century, 18th century, women's history, presidents, paintings, making, home life, holidays, education, by Charles Sable, art

Welcome New Board of Trustees Members

What is your personal connection to The Henry Ford? For many, it’s the memories that have been made during visits to the museum and village. Others, it’s the stories told, artifacts observed, or the people who paved the way for future generations. For Linda Apsey, it was Thomas Alva Edison—his commitment to the utility industry, collaboration with Henry Ford, and future electrification of our society. For Carla Walker-Miller, it is the outreach that The Henry Ford is doing with Detroit Public Schools, the Rosa Parks Bus, and the story that sheds light on the importance of equality, diversity, and inclusion.

While each connection is different, they both share a common theme—access to education, history, and innovation for all, regardless of background or barrier. At this time in our institution’s history, we believe that both leaders will bring invaluable knowledge and perspective based on their experiences. These women are truly remarkable individuals who value our mission and will inspire others for generations to come.

Linda Apsey is currently the President and CEO of ITC Holdings Corp. and is responsible for the company’s strategic vision, business operations, and all subsidiaries. She has held many roles throughout her career that have shaped her into the successful businesswoman she is today. Before she was President and CEO, she served as Executive Vice President and Chief Unit Officer at ITC Holdings Corp.

Linda Apsey is inspired by the stories The Henry Ford can tell with its collections related to Thomas Edison, including his patent model for the electrical distribution system. / THF154126

Apsey is most looking forward to Invention Convention Worldwide. “Invention Convention provides kids across the country with a space and place for imagination to come to life. And that is amazing to observe and be part of!” This program at The Henry Ford allows young minds to tap into their can-do spirit and engage with other students and professionals throughout the world. Invention Convention is one of the unique, educational programs and initiatives that The Henry Ford is using to emphasize the importance of learning and access to education. “THF has developed many exciting programs to tap into the energy, passion, and creative minds of our future generations through teaching, experimentation, and competitions, all of which provides opportunity, access, and collaboration for growing minds.”

Carla Walker-Miller is the founder and CEO of Walker-Miller Energy Services. She is a changemaker in the energy industry and strives to inspire those she encounters. Walker-Miller Energy Services is one of the largest energy waste reduction companies in the country founded and owned by an African American woman.

Walker-Miller is greatly inspired by the community outreach The Henry Ford (THF) is doing in metro Detroit, particularly Detroit Public Schools. “Like most people, I had no idea before I joined the board the amount of work this institution is doing and the commitment The Henry Ford has made in educating our children. The work THF is doing with Detroit Public Schools is so thoughtful and intentional and I’m amazed at the impact The Henry Ford is having.”

Carla Walker-Miller feels welcomed by the presence of the Rosa Parks Bus in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF167250

Being able to inform and educate others about the many different stories and lessons we have learned throughout American history is very important. The Henry Ford is committed to telling the stories of the brave men and women who were the catalysts for change in racial equity. Carla Walker-Miller agrees that the acquisition of the Rosa Parks Bus in the early 2000s was a monumental step for The Henry Ford. “In my heart, that acquisition felt like an acknowledgement that Black history is American history. It may as well have been a bridge, because it felt like a welcome, like a personal invitation to visit. I will never forget the photo of President Barack Obama on that bus. It spoke to me and so many other people of many races.”

Linda Apsey and Carla Walker-Miller both agree that The Henry Ford is a place that is meant to be treasured. To our current donors who believe in the mission and value of The Henry Ford, thank you! For those who may be new to The Henry Ford and are still learning about the institution, we invite you to dive deeper into our mission. For Apsey, “Investing in THF is not only an investment in our rich industrial history of innovation and automation, but more importantly an opportunity to invest in the hearts, souls, and minds of future generations. THF is a world-class institution whose history has just begun!” To Carla Walker-Miller, “The Henry Ford offers a warm introduction to this country’s history. They are committed to making the institution inclusive and accessible to all and to say, ‘Everyone is welcome here.’” We are very lucky to have these two passionate executives help take The Henry Ford to new levels and reach the hearts and minds of future generations.

Caroline Heise is Annual Fund Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Detroit, education, entrepreneurship, Invention Convention Worldwide, The Henry Ford Effect, by Caroline Heise, African American history, women's history, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Women Design: Ray Eames’ Choral Robes

Imagine attending a choral concert in a century-old church. Instead of monochromatic robes, the choristers emerge in bright, radiant color with bold geometric design. The colors of the robes are a musical key, made visual—yellow for the soprano, orange for the contralto, red for the tenor, and purple for the bass. As the choristers sing and sway, the robes come alive, a modern counterpoint to the traditional church interior.

Imagination aside, this is a scene familiar to those who have watched the Hope College Chapel Choir perform. Originally a creation of Charles and Ray Eames from the 1950s, faithful replicas of the robes continue to be used.

The Hope College Chapel Choir at Dimnent Chapel, circa 2001. Photo Courtesy of the Joint Archives of Holland.

Although husband-and-wife design team Charles and Ray Eames collaborated in nearly everything, it was Ray who showed an early and enduring interest in textiles and fashion design. The daughter of a theatre aficionado and manager, she attended the Bennett School for Girls, a two-year college in Millbrook, New York, earning a degree in Fashion Design in 1933. She completed fashion sketches throughout her life—even creating original paper dolls with custom clothing, complete with the tabs used to affix the clothing onto the doll! She designed a few textiles (one of which—“Crosspatch”—won an honorable mention in a 1946 Museum of Modern Art competition) and dedicated significant energy into the design and creation of her own clothing. The clothes she designed for herself and for Charles are quintessential Eames—functional yet beautiful, with playful delights to be found in the details.

D.J. De Pree, the founder and president of the Herman Miller Furniture Company (which produced Charles and Ray Eames’ furniture), was known for his religious fervor. Further, the company is headquartered in Zeeland, Michigan, a Dutch-American enclave with deep Protestant Christian roots. So, when an employee suggested the creation of a company-sponsored chorus in 1952 (something that might otherwise have been an unusual corporate activity), the De Prees granted it legitimacy, naming it the Herman Miller Mixed Chorus and inviting the chorus to perform at company and company-sponsored events. They soon required choral robes to outfit the company chorus and asked Charles and Ray Eames to design them.

Herman Miller Mixed Chorus Soprano and Contralto Vocalist Choir Robes, 1953-1960 / THF75585, THF75580

With Ray’s background, it is likely that she was primarily responsible for the design, although as always in collaboration with her husband. The robes are bold and colorful and make a statement, but they are also functional. Their symbolism is evidence of the Eames’ signature research-heavy process and attention to detail. The colors of the robes identify the vocal type (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) and each color’s hue (from light to dark) corresponds with the vocal range (from high to low). The horizontal black lines at the center of each robe reference the musical staff. Charles and Ray may have scoured the extensive Eames Office reference library to ensure symbolic depth and accuracy. Or, perhaps, this came from an ingrained knowledge of music. They enjoyed a variety of musical types, like jazz, folk, and classical, and music was a major component of the films they produced throughout their life, often collaborating with talented composers like Elmer Bernstein. The theatrical backdrop of Ray’s childhood, her interest in textiles and fashion, and the Eames’ interest in music coalesce in these robes.

Herman Miller Mixed Chorus Tenor and Bass Vocalist Choir Robes, 1953-1960 / THF75574, THF75569

The robes were designed at the Eames Office in Los Angeles, but it is unknown whether the robes were created there and shipped, finished, to Zeeland, or if the patterns and fabric were shipped and the robes were then sewn locally.

By 1960, the Herman Miller Mixed Chorus was disbanded, and Hugh De Pree, son of D.J. De Pree, donated the robes to the Hope College Chapel Choir in the neighboring city of Holland, Michigan, where the family had deep connections. The Hope College Chapel Choir was larger than the Herman Miller Mixed Chorus, so more robes had to be made. Doris Schrotenboer and Millie Grinwis, a mother and daughter team from Zeeland, made the extra. Millie Grinwis recalls that the fabric and patterns were shipped from the Eames Office to her mother’s home, where they were painstakingly put together.

After over 44 years in use, the original robes were retired in 2004. Unwilling, however, to part with the signature design, Hope College commissioned replicas, albeit in a slightly lighter fabric. The original robes were donated to several institutions. At The Henry Ford, these robes add an extra dimension to our design collections, as well as another way to better understand the many talents of Charles and Ray Eames.

The Hope College Chapel Choir recording at Milwaukee’s WTMJ-TV, circa 1965. / Photo Courtesy of the Joint Archives of Holland.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. She is also an alumnus of Hope College, where she was first delighted by these robes! Thank you to Geoffrey Reynolds at the Joint Archives of Holland for graciously sharing pictures of the Hope College Chapel Choir through the years.

20th century, 1950s, women's history, music, Michigan, Herman Miller, fashion, Eames, design, by Katherine White